Abstract

The upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is strongly associated with the development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). Currently, the standard treatment for nAMD involves frequent intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents, which inhibit the growth of new blood vessels and prevent leakage. However, this treatment regimen places a significant burden on patients, their families, and healthcare providers due to the need for repeated visits to the clinic for injections. Gene therapy, which enables the sustained expression of anti-VEGF proteins after a single injection, can dramatically reduce the treatment burden. KH631 is a recombinant adeno-associated virus 8 vector that encodes a human VEGF receptor fusion protein, and it is being developed as a long-term treatment for nAMD. In preclinical studies using non-human primates, subretinal administration of KH631 at a low dose of 3 × 108 vg/eye resulted in remarkable retention of the transgene product in the retina and prevented the formation and progression of grade IV CNV lesions. Furthermore, sustained transgene expression was observed for more than 96 weeks. These findings suggest that a single subretinal injection of KH631 has the potential to offer a one-time, low-dose treatment for nAMD patients.

Keywords: nAMD, AAV, subretinal injection, CNV, NHP, preclinical study, KH631

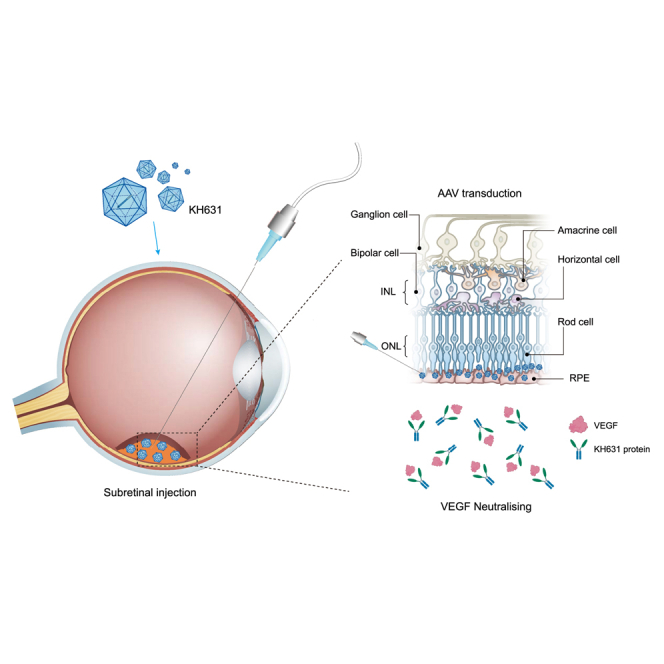

Graphical abstract

Qiang and colleagues report that KH631, an rAAV-based gene therapy product for the treatment of nAMD, shows high expression of the transgenic product (anti-VEGF therapeutic) and robust therapeutic efficacy in NHPs, suggesting that KH631 has the potential to provide a one-time, low-dose treatment for nAMD patients.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of severe vision loss in people over the age of 55 in developed countries, accounting for 6%–9% of cases of legal blindness worldwide. It is estimated that by the year 2040, approximately 288 million people around the world will be affected by AMD.1,2 AMD comes in two forms, dry AMD and advanced neovascular AMD (nAMD, commonly known as wet AMD), the latter of which is severe and causes rapid vision loss. There is a consensus that a key factor in the pathogenesis of AMD is choroidal neovascularization (CNV), which is modulated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a potent inducer of angiogenesis.3,4,5 Currently, anti-VEGF treatments are the standard of care for nAMD, with an increasing amount of data suggesting that long-term anti-VEGF therapy helps maintain and improve vision in AMD patients.6 Although it is generally successful, the need for retreatment can be an additional risk for patients, as well as an inconvenience for both patients and clinicians.7,8 Therefore, there is an urgent need for a long-lasting therapeutic.

Gene therapy is a promising approach for treating many diseases, including nAMD. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors are particularly attractive as in vivo gene delivery tools, as they are mostly non-integrative and have high efficiency, long-term stability, and low toxicity.9 It is a replication-deficient vector that is unable to replicate autonomously, leaving the target gene unintegrated into the chromosome and presenting as an independent extrachromosomal DNA episome in the nucleus.10,11 Recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors have shown promise in preclinical studies as a gene therapy delivery system for the sustained, long-term expression of therapeutic proteins in the eye, including in anti-VEGF treatment.12,13 Gene therapy could have a profound impact on the treatment of nAMD, allowing patients to receive a single injection and achieve sustained relief from the disease. rAAV-delivered aflibercept and anti-VEGF fab (fragment antigen-binding) have shown encouraging results in reducing the injection frequency in clinical trials for the treatment of nAMD (ADVM-022: rAAV2.7m8-aflibercept, NCT03748784; RGX-314: rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab, NCT03066258 and NCT05210803; 4D-150: rAAV.R100-afilibercept-VEGF-C RNAi, NCT05197270). In these clinical trials, patients who received higher doses had fewer rescue injections, demonstrating a clear dose-dependent effect.14,15,16

However, high rAAV doses are a double-edged sword, as a higher rAAV dose leads to a higher incidence of intraocular inflammation. In the Phase 2 INFINITY trial evaluating ADVM-022 in diabetic macular edema, one subject who received a high dose of ADVM-022 (6 × 1011 GC/eye) experienced an unexpected serious adverse reaction of hypotony with panuveitis and loss of vision following a single intravitreal injection.17

nAMD is characterized by the growth of irregular new blood vessels from the choroid under and into the macula. These blood vessels can leak fluid or blood and affect retinal function. By increasing the concentration of anti-VEGF therapeutics in the retinal region, it is hoped that the dose of AAV administered can be reduced, thereby reducing side effects such as intraocular inflammation.

Herein, we developed KH631, a clinical stage rAAV8 gene therapy product for the treatment of nAMD. The transgene product of KH631 is a human VEGF receptor fusion protein consisting of domain 2 of VEGFR1, domain 3 and domain 4 of VEGFR2, and the Fc domain of human immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 (abbreviated as anti-VEGF protein), which can effectively bind to VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PlGF.18,19 KH631 is efficiently transduced into photoreceptor cells and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells by subretinal injection. Surprisingly, through pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies in non-human primates (NHPs), we found that the majority of KH631 protein was retained in the retina, with only a small amount spreading outward. The expression of KH631 protein in the retina was 10.9- to 141.1-fold higher than in the vitreous. As a result of this remarkable retinal retention, KH631 at a low dose of 3 × 108 vg/eye exhibited significant inhibition of the grade IV lesions in the laser-induced CNV NHP model. Furthermore, in a long-term transgene expression assay in NHP, KH631 protein was observed to be persistently expressed in the aqueous humor for 96 weeks. Based on the above results, a single subretinal injection of KH631 offers the possibility of a one-time, low-dose treatment for nAMD.

Results

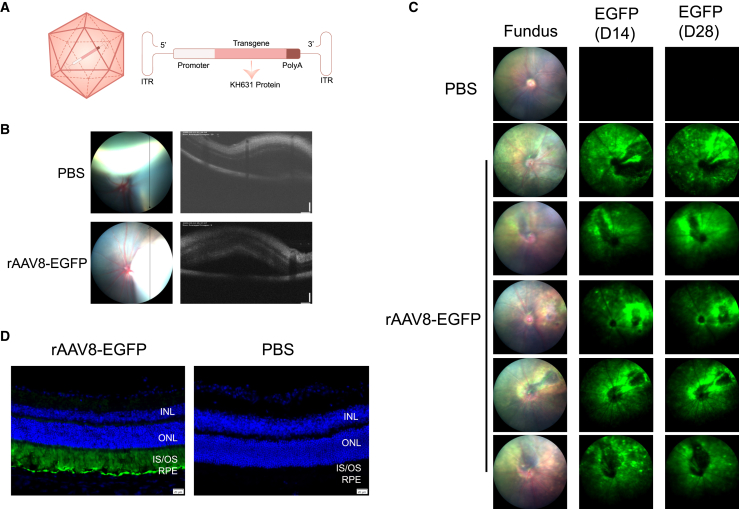

Subretinal injection of rAAV8-eGFP in mice resulted in strong eGFP expression in photoreceptor and RPE cells

AAV8 is a good gene delivery vehicle for nAMD therapy due to its effective transduction into photoreceptor cells and RPE cells when administered via subretinal injection.20 The subretinal space is the area between the neurosensory retina and the RPE. Subretinal injection allows direct contact of the drug with the photoreceptor and RPE layers, optimizing the concentration of the drug in these cells.21 To investigate whether the expression cassette we designed (Figure 1A) can deliver the transgene to photoreceptor cells and RPE cells for successful expression, we first prepared rAAV8-eGFP. A total of five mice were injected with PBS in the left eye and with rAAV8-eGFP (5 × 108 vg/eye) in the right eye. The blebs formed after injections were observed by optical coherence tomography (OCT), indicating the success of the subretinal injections (Figure 1B). The bright green fluorescence signal was detected at day 14 and day 28 post-injection, indicating that the expression cassette was working (Figure 1C). The expression of native eGFP signals was predominantly seen in photoreceptor cells and RPE cells based on the location of the cells,20 indicating successful transduction of both cell types (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

rAAV8 was efficiently transduced into mouse RPE and photoreceptor cells after subretinal injection

(A) Schematic diagram of the KH631 vector (left) and the KH631 transgene cassette (right). (B) Representative optical coherence tomography (OCT) images of treated mouse eyes. The immediate formation of blebs after injection indicates successful subretinal injection. (C) Fluorescence fundus images showed the native eGFP expression at 14 and 28 days after rAAV8-eGFP injection, which indicated the expression cassette was working. INL, inner nuclear layer; IS/OS, photoreceptor inner segment/outer segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer. (D) Representative cross-sections of mouse eyes treated with rAAV8-eGFP or PBS 28 days post-injection. The native eGFP expression indicated rAAV8 was mainly transduced into RPE and photoreceptor cells. Green, eGFP; blue, DAPI. Scale bars, 200 μm.

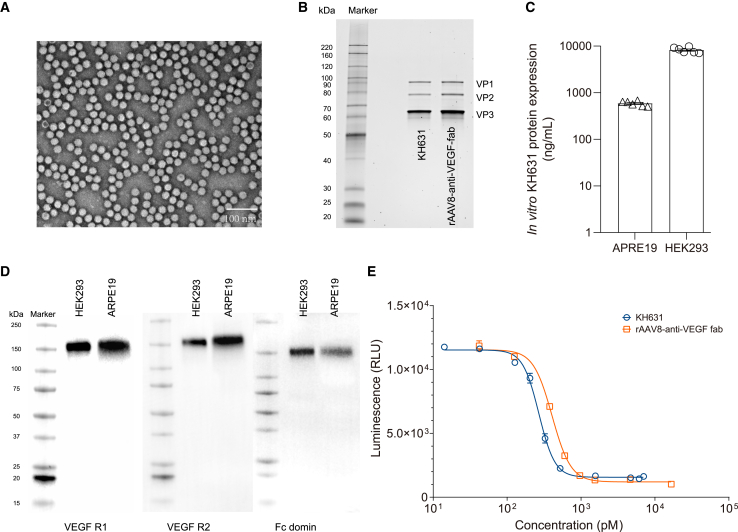

KH631 protein showed higher binding affinity to VEGF165 than anti-VEGF fab

KH631 was produced using a triple plasmid transient co-transfection system, followed by purification through affinity chromatography and anion-exchange chromatography. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results showed a high full/empty ratio of capsids of KH631 (Figure 2A). The molecular weight of the three capsid proteins of KH631 was confirmed by SDS-PAGE; the results showed that the capsid proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 have the expected molecular weights of approximately 87, 73, and 60 kDa, respectively (Figure 2B).22 The potency of KH631 was confirmed by measuring transgene expression in ARPE-19 and HEK293 cells (Figure 2C). As shown in Figure 2D, the proteins produced from KH631 showed exactly the same pattern as anti-VEGF protein in the western blot assay, indicating KH631 expressed full-length anti-VEGF protein in both HEK293 and ARPE-19 cells. These results demonstrated the structural integrity and in vitro activity of KH631.

Figure 2.

The biochemical and physiological properties of KH631

(A) A representative TEM image of KH631 exhibiting a high full/empty ratio of capsids. The targets of interest are light on a dark background. Empty capsids are dark in the center and light at the edge, and full capsids are light evenly. Scale bars, 100 nm. (B) The purities of the VP1, VP2, and VP3 proteins expressed by KH631 and rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab were found to be similar by using reduced SDS-PAGE. (C) KH631 was successfully transduced into ARPE-19 and HEK293 cells in vitro and the transgene product was expressed. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6). (D) The KH631 proteins including human VEGF R1, VEGF R2, and IgG Fc domains were identified by western blot. (E) The VEGF inhibition activities of the transgene products of KH631 (circle) and rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab (square) were evaluated. KH631 demonstrated a lower IC50 value in VEGF inhibition than rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

We also generated rAAV8 constructs expressing a humanized monoclonal antigen-binding fragment that binds and inhibits human VEGF (anti-VEGF fab). The rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab construct encoded comparable VP proteins to KH631 (Figure 2B). The VEGF inhibition activities of the transgene products of KH631 and rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab were evaluated in a KDR (VEGFR2)-overexpressing cell line. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of KH631 protein was 269.2 pM, which is 1.51-fold lower than that of anti-VEGF fab (406.2 pM). These results suggested that KH631 has superior VEGF inhibition activity and therefore greater potential for nAMD gene therapy than rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab.

Pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies of KH631 after a single subretinal injection in rhesus monkeys

Pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies of KH631 were performed in rhesus monkeys subretinally injected with a single dose at 1 × 1011 vg/eye in bilateral eyes. As shown in Table 1, the transgene concentrations in tissues and organs suggested that KH631 entered the eyes via subretinal injection and was mainly distributed in the retina. After that, the drug first spread to the choroid, followed by the sclera and iris/ciliary body, and slowly penetrated into the vitreous body, conjunctiva, and cornea, with little or nearly no drug diffused into the conjunctiva and lacrima. These results suggested that the drug was distributed mainly in posterior segment tissues and then diffused into the anterior segments. The transgene concentrations were relatively high in organs including the spleen and preauricular lymph nodes, but below the lower limit of quantification (BLQ) in most other organs, suggesting KH631 was mainly distributed in ocular tissues, with less and concentrated distribution in organs. The transgene was detected in the serum of only one monkey at 72 h post-injection, and its concentration was near the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) (data not shown); the transgene was detected in the liver of only one monkey at 4 weeks post-injection, suggesting a small amount of drug entered the circulatory system after the retinal injection; the transgene concentration in the brain was BLQ, suggesting the drug could not easily pass the blood-brain barrier; the concentrations in ovary, uterus, prostate gland/seminal vesicle, testis, and epididymis were BLQ, suggesting the drug was not easily distributed in reproductive organs or had a low level in the corresponding tissues; the concentrations in kidney, feces, and urine were BLQ, suggesting the drug could not be easily excreted via the urinary system and feces or its level was low.

Table 1.

Transgene concentrations in different tissues of monkeys after a single subretinal injection of KH631 in bilateral eyes (vg/g for solid tissues or vg/mL for liquid tissues)

| Name | 4 wk postdose |

8 wk postdose |

13 wk postdose |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1F001 | 1M001 | 1F002 | 1M002 | 1F003 | 1M003 | |

| Aqueous humor∗ | 7.77 × 105 | BLQ | NR | NR | BLQ | BLQ |

| RPE/Choroid | 1.10 × 1010 | 5.60 × 109 | 6.27 × 109 | 2.18 × 109 | 7.97 × 109 | 5.33 × 109 |

| Cornea | 1.51 × 107 | 1.84 × 105 | 7.02 × 106 | 1.14 × 106 | BLQ | BLQ |

| Lens | 1.06 × 106 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 5.92 × 105 | BLQ |

| Sclera | 6.56 × 108 | 1.97 × 106 | 1.02 × 107 | 5.14E+08 | 9.92 × 106 | 1.81 × 106 |

| Optic nerve | 7.84 × 105 | BLQ | BLQ | 6.59E+05 | BLQ | BLQ |

| Retina# | 3.24 × 1010 | 8.64 × 109 | 8.64 × 109 | 7.31 × 109 | 8.32 × 109 | 4.94 × 109 |

| Vitreous body∗ | 2.72 × 107 | 9.64 × 106 | 1.13 × 106 | 1.53 × 106 | 2.14 × 107 | 2.60 × 105 |

| Iris/Ciliary body | 2.18 × 108 | 7.71 × 107 | 6.56 × 107 | 3.88 × 106 | 3.83 × 107 | 2.85 × 106 |

| Conjunctiva | 6.60 × 107 | 1.64 × 107 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Preauricular lymph nodes | 6.99 × 106 | 1.54 × 107 | NR | NR | 3.03 × 105 | 1.66 × 106 |

| Spleen | 6.40 × 107 | 3.39 × 107 | 1.77 × 107 | 3.16 × 107 | 4.84 × 107 | 1.64 × 106 |

| Liver | 1.34 × 106 | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Lacrima | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Bone marrow∗ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Cerebrum | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Forebrain | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Thalamus | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Jejunum | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Kidney | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Nasal mucous | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Oral mucosa | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Skeletal muscle | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Stomach | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Pancreas | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Heart | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Ovary | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – |

| Ulterus | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – |

| Epididymis | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ |

| Prostate gland/Seminal vesicle | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ |

| Testis | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ |

| Lung | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Urine∗ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

“∗” means liquid tissues, with the unit of vg/mL; “–” means no tissue; NR means no data were reported since no sample was re-assayed; BLQ means below the lower limit of quantification. “#” retina refers to the neuroretina (photoreceptor layer to the ganglion/nerve fiber layer).

The transgene product of KH631 (KH631 protein) was expressed primarily in the retina and choroid and secondarily in the sclera, vitreous, and iris/ciliary body, according to the transgene expression assay results shown in Table 2. The expression of KH631 protein in the vitreous was 5.5- to 9.7-fold higher than in the aqueous humor, and in the retinal segments it was 10.9- to 141.1-fold higher than in the vitreous and 69.1- to 301.4-fold higher than in the aqueous humor. After subretinal injection of RGX-314 (rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab; 1 × 1011 vg/eye, same dose as KH631), a clinical stage gene therapy product for the treatment of nAMD, transgene product expression in the vitreous was 3- to 9-fold higher than in the aqueous humor and in the retina it was 1.2- to 3.6-fold higher than in the vitreous.23 Compared with RGX-314, KH631 showed a significantly higher accumulation of transgene product in the retina. nAMD is characterized by abnormal blood vessel formation in the choroid and subsequent invasion of the retina. There is potential for improved efficacy in the treatment of nAMD through the accumulation of anti-VEGF protein in the retina.

Table 2.

Concentrations of the transgene product (KH631 protein) in different tissues of rhesus monkeys after a single subretinal injection of KH631 in bilateral eyes (ng/g for solid tissues or ng/mL for liquid tissues)

| Name | 4 wk postdose |

8 wk postdose |

13 wk postdose |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1F001 | 1M001 | 1F002 | 1M002 | 1F003 | 1M003 | |

| Cornea | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 28.6 | 45.8 | 60.6 |

| Aqueous humor∗ | 118 | BLQ | 198 | 34.5 | 87.7 | 188 |

| Iris/Ciliary body | 415 | BLQ | 369 | 96.1 | 314 | 144 |

| Lens | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 82.8 | 50.7 |

| Vitreous body∗ | 651 | 190 | 1930 | 253 | 580 | 1190 |

| Retina | 15400 | 26800 | 22400 | 10400 | 17000 | 13000 |

| Choroid | 9370 | 4330 | 7330 | 16400 | 9910 | 3850 |

| Sclera | 642 | 255 | BLQ | 103 | 769 | 178 |

| Optic nerve | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 104 | 65.4 | 34.5 |

| Conjunctiva | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Liver | 25.9 | 23.7 | 34.2 | 60.6 | 280 | 224 |

| Spleen | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 42.4 | 32.8 |

| Feces | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 34.2 | 55.7 |

| Preauricular Lymph nodes | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Lacrima | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Bone marrow∗ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Cerebrum | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Forebrain | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Thalamus | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Jejunum | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 36.1 | 49.9 |

| Kidney | BLQ | 71.4 | 64.8 | 106 | 349 | 318 |

| Nasal mucous | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Oral mucosa | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Skeletal muscle | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 25.8 | 45.0 |

| Stomach | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Pancreas | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 175 | 189 |

| Heart | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 83.4 | 62.4 |

| Ovary | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – |

| Uterus | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – |

| Epididymis | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ |

| Prostate gland/Seminal vesicle | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ |

| Testis | – | BLQ | – | BLQ | – | BLQ |

| Lung | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

| Urine∗ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | BLQ |

“∗” means liquid tissues, with the unit of ng/mL; “–” means no tissue; BLQ means below the lower limit of quantification.

The KH631 protein was mainly detected in the liver and kidney, but the concentrations in the serum, brain, ovary, uterus, prostate gland/seminal vesicle, testis, and epididymis were BLQ, suggesting the drug had low expression in the brain, reproductive organs, and serum or could not easily distribute to the corresponding organs or tissues after expression; the concentrations of KH631 protein in feces and urine were low or BLQ, suggesting little KH631 protein was excreted via feces and urine.

After bilateral eyes of rhesus monkeys were subretinally administered with KH631 at 1 × 1011 vg/eye, the concentration of transgene was only detectable in 1F003 at 72 h post dose, and was all BLQ for other animals at all time points. The serum concentrations of KH631 protein in all animals at different time points were BLQ.

The concentrations of VEGF in the serum at different time points were determined (Table 3). The VEGF concentrations of 1F001 and 1M001 were 8.660 and 14.082 pg/mL before injection; the concentrations were 3.337 and 5.072 pg/mL at 4 weeks post-injection. The VEGF concentrations of 1F002 and 1M002 were 9.706 and 28.419 pg/mL before injection; the concentrations were 7.309 and 13.937 pg/mL at 8 weeks post-injection. The VEGF concentrations of 1F003 and 1M003 were 5.245 and 16.674 pg/mL before injection; the concentrations within 13 consecutive weeks post-injection generally decreased slightly when compared with the pre-injection concentration and fluctuated within the ranges from 0.839 to 5.415 pg/mL and from 2.279 to 13.138 pg/mL, respectively. The decrease in serum VEGF concentrations in these NHPs is limited compared with that in patients who received vitreous injections of anti-VEGF agents (i.e., aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab), as the patients’ plasma VEGF levels decreased considerably or even fell below LLOQ.24 This is consistent with the low plasma levels of the KH631 protein (BLQ at all the time points).

Table 3.

VEGF concentrations in serum at different time points after a single subretinal injection of KH631 in bilateral eyes (pg/mL)

| Time point (h) | 1F001 | 1M001 | 1F002 | 1M002 | 1F003 | 1M003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predose | 8.660 | 14.082 | 9.706 | 28.419 | 5.245 | 16.674 |

| 6 | / | / | / | / | 1.786 | 7.853 |

| 24 | / | / | / | / | 1.792 | 7.942 |

| 72 | / | / | / | / | 5.415 | 2.279 |

| 168 | / | / | / | / | 1.731 | 8.009 |

| 336 | / | / | / | / | 0.839 | 3.999 |

| 672 | 3.337 | 5.072 | / | / | 0.955 | 4.915 |

| 840 | / | / | / | / | 1.706 | 3.554 |

| 1008 | / | / | / | / | 3.530 | 4.806 |

| 1344 | / | / | 7.309 | 13.937 | 1.859 | 11.776 |

| 1848 | / | / | / | / | 2.592 | 6.548 |

| 2184 | / | / | / | / | 3.235 | 13.138 |

“/” means no collected sample and no data.

The serum anti-drug (KH631 protein) antibody (ADA) and anti-AAV8 neutralizing antibody (NAb) levels were analyzed. All animals in the study were confirmed to be negative for serum ADA before dosing. Animals for necropsy were confirmed to be negative for serum ADA at 4, 8, and 13 weeks post-injection (data not shown). Notably, 1F003 and 1M001 were confirmed to be positive for serum anti-AAV8 NAb before dosing, but the pre-existing anti-AAV8 NAb did not block the expression of AAV after subretinal injection. This result was consistent with a previously published paper that suggested that anti-AAV8 NAb may not be able to penetrate the blood-eye barrier.25 1M001 was confirmed to be positive at 4 weeks post-injection, with NAb levels that were comparable to the pre-injection levels; 1F001 was confirmed to be negative; 1M002 and 1F002 were confirmed to be positive at 8 weeks post-injection; 1M003 and 1F003 were confirmed to be positive at 13 weeks post-injection and the NAb levels of 1F003 were increased compared with the pre-injection levels (Table 4).

Table 4.

Anti-AAV8 neutralizing antibody levels in serum at different time points after a single subretinal injection of KH631 in bilateral eyes

| Animal ID | Predose |

4 wk postdose |

8 wk postdose |

13 wk postdose |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAb blockade (%) | Result | NAb blockade (%) | Result | NAb blockade (%) | Result | NAb blockade (%) | Result | |

| 1F001 | 16.59 | N | 16.51 | N | / | / | / | / |

| 1F002 | 4.62 | N | / | / | 91.55 | P | / | / |

| 1F003 | 51.27 | P | / | / | / | / | 63.06 | P |

| 1M001 | 91.59 | P | 88.91 | P | / | / | / | / |

| 1M002 | 36.47 | N | / | / | 57.53 | P | / | / |

| 1M003 | −3.16 | N | / | / | / | / | 100.1 | P |

N, negative; P, positive.

In all eyes of rhesus monkeys treated with KH631, no abnormality was noted in intraocular pressure and no drug-related abnormalities were noted in the cornea, iris, lens, fundus retina, retinal vessels, macula lutea, and optic disk. Mild aqueous cell or vitreous cell infiltration was seen in a few monkeys (data not shown). Limited change in retinal thickness was noted at the center of the macula lutea for all surviving animals at 32 days, 8 weeks, and 13 weeks when compared with the pre-injection thickness; the difference was generally within ±10 μm (data not shown), suggesting little effect was produced on the retina at the macula lutea center after injection and animal eyesight was hardly affected.

Retinal functional integrity was assessed using electroretinography (ERG) in two monkeys (1M003 and 1F003). Dark-adapted (DA) 3.0, DA 3.0 oscillatory potential, and light-adapted (LA) 30 Hz flicker were performed. All eyes showed a different degree of decrease in the DA 3.0 a-wave amplitude at 4 and/or 8 weeks, but a clear trend toward recovery was observed at 13 weeks (Table S3). This phenomenon may be related to the mechanical stimulation that occurs during the subretinal injection. The recovery of retinal function from the edema and pressure caused by subretinal injection may take time and happen gradually. The implementation of a sham control group is essential to validate this hypothesis. In the following good laboratory practice toxicity study, we will establish a sham control group and perform a more comprehensive assessment of the functional integrity of the retina.

Together, these results suggested that KH631 did not alter retinal morphology or induce significant inflammatory responses.

KH631 effectively inhibited neovascularization in a laser-induced CNV model in rhesus monkey

CNV, the invasion of newly formed blood vessels from the choroid through a break in Bruch’s membrane, is a feature of AMD. Intense laser photocoagulation has been used to break Bruch’s membrane to produce CNV in rat, rabbit, cat, and NHP models. NHP eyes are close in size to human eyes and have similar anatomical constituents and proportions, including the existence of a nearly identical macular region; therefore, monkey models have been the most commonly used in eye research. The therapeutic potential of KH631 was evaluated in a laser-induced CNV rhesus monkey model. Rhesus monkeys were divided into eight groups, including seven KH631 groups (3 × 108, 1 × 109, 3 × 109, 1 × 1010, 3 × 1010, 1 × 1011, and 5 × 1011 vg/eye) and a vehicle control group. A single subretinal injection of KH631/vehicle was given 28 days before laser modeling. The number of grade IV lesions and the fluorescein leakage areas of the retina, which reflect the severity of neovascular dysfunction, were determined by fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA). For the vehicle group, the percentage of grade IV lesions was 77.78% and 66.67% at 2 and 4 weeks after laser treatment, respectively, indicating the formation of new vessels. A significant decrease of grade IV lesions was found in all KH631 groups; no or rare grade IV lesions were found in the 3 × 109, 1 × 1010, 3 × 1010, 1 × 1011, and 5 × 1011 vg/eye groups at 2 and 4 weeks after laser treatment (p < 0.001 compared with vehicle group). A remarkable neovascularization inhibition effect was also observed in the 3 × 108 and 1 × 109 groups, with grade IV lesion percentages of 26.67% and 8.33% at week 2 and 10% and 5.56% at week 4, respectively (Figures 3B and 3C). These results suggested that KH631 effectively suppresses the formation of grade IV lesions at doses as low as 3 × 108 vg/eye.

Figure 3.

The therapeutic potency of KH631 in a laser-induced CNV model

(A) Overview of efficacy testing in a laser-induced CNV model. (B) Representative fluorescein angiograms of rhesus monkey eyes on day 14 and day 28. (C) Percentage of grade IV lesions after subretinal injection of KH631 at different doses or vehicle (formulation buffer). KH631 exhibits good grade IV lesion suppression at doses as low as 3 × 108 vg/eye. The percentage of grade IV CNV lesions in each evaluable eye was calculated (Table S4) (n = 4–6 eyes). (D) Variation of the retinal thickness compared with the pre-laser thickness (n = 4–6 eyes). The results shown in (B)–(D) suggest that KH631 effectively inhibits neovascularization in a dose-dependent manner. (E) KH631 protein was continuously expressed in the aqueous humor for 96 weeks, which suggested the potential for sustained treatment of nAMD (n = 6 eyes). These rhesus monkeys are currently being monitored to observe transgene expression over a longer period. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Each KH631 group in (C) and (D) was compared with the vehicle group using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Dunnett post hoc test. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

After modeling, OCT examination showed continuous destruction of RPE at the photocoagulation site. The thickness at the lesion top was measured from the nerve fiber layer to Bruch’s membrane. In some eyes in the vehicle group we observed retinal neurepithelium layer edema and local bulge, which are pathological changes of the retina after the growth of new vessels. Animals in the 1 × 109, 3 × 109, 1 × 1010, 3 × 1010, 1 × 1011, and 5 × 1011 vg/eye KH631 groups showed no obvious retinal edema and the reduction of retinal thickness was obviously decreased as compared with the vehicle group at 2 and 4 weeks after laser treatment (p < 0.001, Figure 3D).

In the present study, animals were monitored at a daily base after laser injury, and slit lamp microscopy, OCT, and fundus color photography were performed every 2 weeks. Except for the laser-induced injury site, a mild inflammatory reaction was observed in the anterior area of all animals’ laser-damaged eyes through the whole observation period (4 weeks after laser treatment). In general, all animals stayed in normal conditions with no movement or mental abnormalities, and the ocular area was not affected by the subretinal injection or AAVs. Notably, the bleb created by the injection subsided within hours, and there was no detectable damage in the injection area after operation. The above results suggested that KH631 effectively inhibits neovascularization with only mild inflammatory effects.

Another experiment to study the long-term expression of KH631 was conducted on rhesus monkeys. Animals were subretinally injected with KH631 at doses of 5 × 1011, 1 × 1012, and 2 × 1012 vg/eye in bilateral eyes. Aqueous humor was collected and the concentration of KH631 protein was determined. As shown in Figure 3E, KH631 protein was continuously expressed in the aqueous humor for 96 weeks, which demonstrated the potential of KH631 for the long-lasting treatment of nAMD. Longer expression of KH631 protein is currently under investigation.

Discussion

AAVs are attractive in vivo gene delivery tools characterized by their being non-integrative and having high efficiency, long-term stability, and low toxicity.26 It is a replication-deficient vector that cannot replicate autonomously, leaving the target gene as an independent extrachromosomal DNA episome in the nucleus.27,28 rAAV is the only gene therapy vector classified by the NIH rated as RG1 (the highest level of safety) and free of potential pathogenicity.29

The route of administration is an important consideration in ophthalmic gene therapy. Subretinal injection is a very efficient means of delivering AAV directly to the retina without the influence of barriers such as the inner nuclear layer and outer nuclear layer. This route of administration has been used in a Food and Drug Administration-approved rAAV gene therapy product, luxturna. In recent years, intravitreal and suprachoroidal injections have also received a lot of attention for the delivery of rAAVs due to their simplicity. However, the retinal delivery efficiency of these routes is much lower than that of subretinal injections, resulting in the need to use higher doses of rAAV, which in turn induces significant inflammatory and immune responses. Subretinal injection using much lower doses can achieve the same transgene expression levels as intravitreal and suprachoroidal injections. However, subretinal injections require delicate manipulation by the ophthalmologist and can cause mechanical damage to the retina at the injection site, raising safety concerns. To date, subretinal injections have been shown to be safe and well tolerated in several clinical trials; for example, the clinical trials of luxturna and RGX-314 show that the most common adverse reaction is mild retinal pigmentary changes.30,31

nAMD is characterized by growth of irregular new blood vessels from the choroid under and into the macula and leakage of fluid or blood from the vessels, which affects retinal function. Anti-VEGF therapy is effective to inhibit neovascularization. Expression of anti-VEGF therapeutics in the focal area promises to be an effective way to treat nAMD with low doses of rAAV. rAAV8 has been shown to be more effective than rAAV2 in transducing RPE and photoreceptor cells.20 We designed a gene expression cassette using eGFP as a reporter gene and observed that rAAV8 efficiently transduced RPE and photoreceptor cells after subretinal injection in mice (Figure 1), consistent with the literature.

To generate the KH631 vector, we cloned the gene encoding the VEGF receptor fusion protein (conbercept), which is approved for commercial use in China,19 into our expression cassette, and the KH631 vector was delivered by subretinal injection using rAAV8 to investigate its potential for the treatment of nAMD. Previous clinical trials and practices suggest that conbercept is well tolerated and effective.32,33,34 In addition, several studies have demonstrated the safety and long-term expression of rAAV8-based gene therapy products after subretinal injection.35,36

AAV-mediated gene delivery is known to be toxic at high doses.37,38 Previous studies have shown that the toxicity is directly related to the injected dose and can be entirely avoided at low doses.38 One subject’s loss of vision after receiving 6 × 1011 GC/eye of ADVM-022 by intravitreal injection has rung alarm bells for high-dose rAAV.17 One vector-related concern is the extraocular distribution of the vector and transgene. Another safety issue is the immunological response to the rAAV capsid and the transgene product.39 Intraocular administration of rAAV2 and rAAV8 resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the levels of neutralizing antibodies against the vector capsid.20,40 A biodistribution study was conducted in rhesus monkeys to investigate the ocular and systemic pharmacokinetic characteristics of KH631. The results showed that the transgene was mainly distributed to ocular tissues, with very low levels in non-ocular tissues (e.g., spleen and preauricular lymph nodes). No transgene was detected in reproductive organs, except for a trace of transgene in the prostate in a few animals (Table 1). In the KH631 groups, anti-transgene product antibodies were detected in some monkeys and anti-AAV8 neutralizing antibodies were detected in most monkeys throughout the study (Table 4). Interestingly, two monkeys were confirmed to be positive for serum anti-AAV8 NAb before dosing, but the pre-existing anti-AAV8 NAb did not block rAAV expression after subretinal injection. This is consistent with a previous report of a Phase I/II clinical trial of RGX-314 showing that serum anti-AAV8 NAbs do not affect the sustained expression of the transgene product.41

The primary safety finding of KH631 was ocular adverse reactions, such as hierarchy disorder, thinning, and inflammation in the retinal injection site. As the control group also had retinal hierarchy disorder, this reaction was at least partially caused by the mechanical stimulation of the injection. Retinal functional integrity was assessed in two monkeys (1F003 and 1M003) by ERG. Although the DA 3.0 a-wave amplitude decreased in all eyes at 4 and/or 8 weeks, it also showed continuous improvement over time (Table S3). We conjectured that this phenomenon may also be related to the mechanical stimulation of the subretinal injection.

Increasing the concentration of therapeutics at the target tissue may be a potential strategy to reduce the dose of rAAV. Several VEGF inhibitors have been approved for marketing, including monoclonal antibodies (bevacizumab and ramucirumab), fusion proteins (aflibercept and conbercept), fab antibody fragments (ranibizumab), and single-chain variable fragments (brolucizumab). Although all of these compounds are effective in VEGF inhibition, they exhibit distinct pharmacokinetic profiles in vivo.42,43 Therefore, delivering these compounds by rAAVs may result in varied concentrations of therapeutics in the target tissues. The level of the KH631 transgene product (conbercept) was 10.9- to 141.1-fold higher in the retinal segments than in the vitreous (Table 2). It was reported that the level of the transgene product of RGX-314 (anti-VEGF fab, similar to ranibizumab) in the retina was only 1.2- to 3.6-fold higher than in the vitreous.23 This indicates a more prominent retinal accumulation of KH631 compared with the same dose of RGX-314.

The ocular half-life of aflibercept in patients is 9.1 days,44 which is longer than the 7.2 days of ranibizumab.45 It can be inferred that aflibercept has a longer duration in the eye compared with ranibizumab. The ocular half-life of conbercept in patients has not been reported. Nonetheless, according to their package inserts, conbercept is administered every 3 months after monthly dosing for the initial 3 months, in contrast to aflibercept, which is administered every 2 months. The longer dosing interval of conbercept can be attributed to its higher molecular weight (143 kDa)46 than aflibercept (115 kDa),43 because of an additional extracellular domain 4 of VEGFR2.32 According to a previous report,47 protein drugs show a strong positive correlation between molecular weight and ocular half-life after intravitreal injection in humans. It is hypothesized that the half-life of conbercept in the eyes of patients could be longer than that of aflibercept and ranibizumab. Perhaps this explains why the KH631 transgene product has a longer retention time in the retina compared with the transgene product of RGX-314, leading to a higher retina/vitreous ratio. Due to this remarkable retinal retention of the transgene product, KH631 at a dose as low as 3 × 108 vg/eye significantly prevented the formation and development of grade IV lesions in a laser-induced CNV model (Figures 3B–3D).

In conclusion, subretinal injection of KH631 in NHPs showed good efficacy with no serious adverse events, visual impairment, or extraocular vector spread. In addition, it did not induce any harmful immunological responses. The results of this preclinical study indicate that gene therapy using subretinal injection of KH631 is safe, well tolerated, and promising for the long-term treatment of nAMD.

Materials and methods

Animal care and handling

Six- to 8-week old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Dashuo Laboratory Animal Technology. After a week of adapting, the mice were injected by subretinal injection of test vectors. Rhesus monkeys were purchased from Sichuan Greenhouse BioTech Co., Ltd. The contents and procedures related to animal experiments in the study complied with the relevant laws and regulations of the use and management of experimental animals and the relevant guidelines issued by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at West China-Frontier PharmaTech.

Rhesus monkeys were anesthetized with 2.5% pentobarbital sodium (25 mg/kg) and/or 5% ketamine (10 mg/kg) via intravenous injection (dosage was adjusted according to the monkeys’ anesthesia status) for all procedures and ophthalmic evaluations. For ophthalmic evaluations, eyes were dilated, if needed, using Mydrin-p (Compound Tropicamide Eye Drops). The amount of food biscuits consumed daily was monitored. Body weight was measured at the time of ophthalmic examinations.

rAAV production

The expression of all transgenes used was controlled by the CMV early enhancer/chicken β-actin (CBA) ubiquitous promoter, a chicken β-actin intron, and a rabbit β-globin poly(A) signal.48 The KH631 vector (encoding rAAV8-anti-VEGF protein) contains a gene cassette that encodes a human VEGF receptor fusion protein (143 kDa). The fusion protein is composed of domain 2 of VEGFR1, domain 3 and domain 4 of VEGFR2, and the Fc domain of human IgG1. The KH631 vector was produced by a three-plasmid transfection system. Briefly, HEK293 cells grown in 293Pro chemically defined 293M medium (BasalMedia) in suspension were triple transfected with pHelper, pAAV transgene (encoding pAAV-CBA-anti-VEGF protein49), and pAAV Rep-Cap plasmids using FectoVIR-AAV (Polyplus) in a BIOSTAT STR200 bioreactor (Sartorius). At 68 ± 4 h post-transfection, cells were harvested by tangential flow filtration through a hollow fiber filter and lysed with Triton X-100. Lysates were centrifuged and filtered for clarification. Capture purification was performed on a POROS CaptureSelect AAVX (Thermo) affinity chromatograph. Then, benzonase (Merck) was added to a final concentration of 200 units/mL along with magnesium chloride to a final concentration of 2 mM. After benzonase treatment, the AAV vector was further purified using POROS 50 HQ (Thermo) anion-exchange chromatography for empty-capsid reduction. The purified rAAV was added to formulation buffer (containing 0.001% poloxamer 188) via UF/DF. Finally, sterilization was performed by filtration through a 0.22-μm filter. All drug products contained less than 5 EU/mL of endotoxin.

rAAV8-anti-VEGF fab, which contains a gene cassette encoding a humanized monoclonal antigen-binding fragment (48 kDa43) that binds and inhibits human VEGF, was prepared in the same manner except that the transgene plasmid was pAAV-CBA-anti-VEGF fab.23 The same method as described above was used to produce rAAV8-eGFP, the only difference being the smaller scale.

Vector genome titer

rAAV vectors were titered by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). Primers and fluorescent probes were designed based on the KH631 transgene sequence (data on the KH631 structure are available from the patent WO2022/051537 A1). In summary, rAAV was digested by DNase at 37°C for 1 h. EDTA was added and the sample was heated in an 85°C water bath for 20 min to terminate the reaction. Proteinase K was added to the sample, and then the sample was incubated at 55°C for 2 h, followed by incubation at 100°C in a boiling water bath for 15 min to terminate the reaction to release the genomic DNA. The genomic DNA was diluted to 100–10,000 vg/μL and used as a template. The PCR reaction was performed using a ddPCR instrument.

Subretinal injection

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (0.1 mg/g, Sigma, #K1884)–xylazine (0.02 mg/g, MedChemExpress, #HY-B0443A)–sterile water at a ratio of 0.6:1:8.4. Mice were placed on the operating table after anesthesia and given local anesthesia with 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride (TCI, #P2156) in the eyes. Holding the head with the left hand and the microinjector with the right hand, the microinjector was inserted into the vitreous at 1 mm from the posterior edge of the cornea, with the tip of the 34-gauge beveled needle entering vertically at first and then tilted up to the contralateral retina, stopping the needle when there was resistance and slowly pushing 1 μL rAAV vector solution (5 × 1011 vg/mL) with a UMP3T-1 Microinjection Syringe Pump using a Nanofil Sub-Microliter Injection System (World Precision Instruments) under an Opmi 1 FR pro surgical microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Mydriasis was conducted in monkeys using Mydrin-p (eye instillation, one to two drops/eye) and then monkeys were anesthetized with 2.5% pentobarbital sodium (25 mg/kg) via intravenous injection. The eyes to be dosed were disinfected with povidone iodine solution. The monkey’s eyelids were opened with the eyelid opener so as to expose the operation site. The scleral puncture needle was injected at 2 mm from the corneoscleral limbus toward the center of the eyeball and then the scleral tunnel nail was left. After that, the drug was subretinally injected after slightly puncturing at a proper site of the retina with a microinjection device under a surgical microscope combined with a retinoscope. Oxybuprocaine hydrochloride eye drops (one to two drops) were used for ocular surface anesthesia before administration. After the injection, one to two drops of ofloxacin eye ointment were given to each eye to keep the cornea wet and prevent infection.

Native eGFP expression analysis

Mice were euthanized and eyes were harvested and fixed in FAS eye fixative (Servicebio, #G1109) overnight at 4°C. Then eyes were embedded in a 1:1 mixture of optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek, #4583) and 30% sucrose and cryo-sectioned at 5 μm on a Leica EM UC7. Cross-sections were washed three times and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Thermo, #D3571). The slides were examined using Olympus Digital scanning and viewing software (Japan, OlyVIA).

Determination of capsid protein molecular weight and purity by SDS-PAGE

The molecular weight and purity of capsid protein were determined by reduced SDS-PAGE. The samples were reduced with 2-hydroxy-1-ethanethiol (Merck, #H45353) and then heated in a 90°C water bath for 10 min. The rAAV samples of 1.5 × 109 to 4.5 × 1010 vg could be loaded on a 10% precast gel for electrophoresis. Then the gel was stained with SYPRO Ruby (Bio-Rad, #170–3125) and scanned by a gel-imaging system. The molecular weight and purity were determined by comparison with a marker (Unstained Protein Ladder, Thermo, #10747–012, 10–220 kDa) using Image Lab 6.0.0.

Potency assay: In vitro transgene product expression in cells

The in vitro expression of the KH631 transgene product was measured by ELISA. ARPE-19 and HEK293 cells were seeded into a 12-well plate and incubated with KH631 at 37°C for 87–90 h. The infected cells were lysed by freezing and thawing, and the supernatants were collected after centrifugation. Plates were coated with recombinant human VEGF165 protein (R&D, #293-VE). The standard curve in the range of 0.78 ng/mL to 100 ng/mL was established based on the reference standard of anti-VEGF protein. After blocking, the supernatants were added to the coated wells and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Then biotin-labeled anti-VEGFR1 (R&D, #MAB321) was added to the wells, followed by incubation for 0.5 h at 37°C. Next, streptavidin-HRP (Cell Signaling, #3999) was added to the wells, followed by incubation for another 0.5 h at 37°C. TMB solution (R&D, #DY999) was added for color development. The reaction was stopped with 2 N H2SO4 and the absorbance at 450 nm was recorded (TECAN, Switzerland).

Potency assay: In vitro VEGF inhibition of transgene products

In vitro VEGF inhibition was performed by a VEGF bioassay, which is a bioluminescent assay that uses KDR/NFAT-RE HEK293 cells (Promega, #GA1082). The KDR/NFAT-RE HEK293 cells have been engineered to express the NFAT response element upstream of Luc2P as well as exogenous KDR (VEGFR2). When VEGF binds to KDR/NFAT-RE HEK293 cells, the KDR transduces intracellular signals resulting in NFAT-RE-mediated luminescence. The experiment was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, transgene products were diluted and incubated with 50 ng/mL VEGF (R&D, #293-VE) at a 1:1 volume ratio for 10–40 min. Next, 20 μL of the mixture was transferred and incubated with 2 × 104 KDR/NFAT-RE HEK293 cells at 37°C for 5–6 h. The bioluminescent signal was quantified using a Bio-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, #G7941). The concentration of transgene products and corresponding relative light unit (RLU) values were fitted to the four-parameter curve to calculate IC50.

Transmission electron microscopy

rAAVs (about 5 × 1012 vg/mL) were adsorbed onto 400-mesh carbon-coated copper TEM grids for 2 min. After washing twice with ddH2O, the grids were stained with phosphomolybdic acid for 30 s. After drying, grids were imaged using a Tecnai G2F20 transmission electron microscope.

In vitro transgene product identification by western blotting

The domains of the transgene product expressed by HEK293 and ARPE-19 cells (ATCC, #CRL2302) infected with rAAV (KH631 product) were identified by western blotting. The total protein fraction was obtained, 4× loading buffer was added, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, 0.22 μm, #ISEQ00010), which were washed with 1× PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, blocked with blot blocking buffer, and incubated with anti-VEGFR1 antibody, anti-VEGFR2 antibody, and anti-IgG Fc antibody. Membranes were washed, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and washed again. Protein bands were visualized with a pro-light HRP chemiluminescent kit.

Quantification of transgene and transgene product

Monkeys were euthanized and tissues including entire conjunctiva (including palpebral conjunctiva and bulbar conjunctiva), eyeballs, and optic nerve of bilateral eyes were separated, washed at least twice in normal saline, and then dried with filter paper or absorbent paper. Tissues including cornea, aqueous humor, iris/ciliary body, lens, vitreous body, retina, choroid, sclera at the injection site, optic nerve, periocular nasal mucous, saliva and oral mucosa, and nasolacrimal duct were separated.

For transgene product detection, the solid tissues were supplemented with PBS containing protease inhibitor at a ratio of 5 mL PBS per 1 mg tissue; vitreous body was homogenized directly. All homogenates were centrifuged at 5000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. The obtained supernatant was aliquoted at approximately 100 μL/tube, and the remaining supernatant was stored in another tube. The liquid tissues, such as aqueous humor and urine, were directly aliquoted (approximately 50 μL in one tube and the rest in another one). The above homogenates were stored below −65°C. A validated ELISA method (validation results shown in Table S1) was used to detect the transgene product in homogenates. Briefly, 100 μL of human VEGF165 protein (1 μg/mL in 0.05 M carbonate buffer solution, ACROBiosystems) was added to a 96-well microplate. The microplate was sealed and incubated overnight at 2°C–8°C. The coating solution was decanted and the plate was washed three times with 300 μL wash buffer. The microplate was blocked for 2 h at 15°C–25°C. Next, 100 μL of sample (including reference standards, quality control samples, and study samples) was added to the microplate. The microplate was covered and incubated for 1 h at 15°C–25°C. After three washes, 100 μL of biotin-labeled anti-VEGFR1 (R&D, #MAB321) was added and the plates were incubated at 15°C–25°C for 1 h. Next, streptavidin-HRP (Cell Signaling, #3999) was added and plates were incubated for a further 0.5 h. After three washes, 100 μL of TMB chromogenic solution was added for color development. The reaction was stopped with 2 N H2SO4 and the absorbance at 450 nm was recorded (Thermo, Varioskan LUX).

For transgene detection, DNA was extracted from the tissues of interest. Solid tissue samples were thawed on ice. All ocular tissues were homogenized. For organ tissues, approximately 100 mg of tissue samples (at least five sites from different parts) were transferred to a 2.0-mL grinding tube and mixed with three to five ceramic beads (3-mm diameter) and an appropriate volume of lysis buffer based on the tissue weight (25 mg: 200 μL; for less than 25 mg of tissue, 200 μL of lysis buffer was added). Samples were homogenized at 6,800 rpm for 20 s using a homogenizer for three repeated cycles with a 20-s interval between each homogenization step (repeated once or twice in case of incomplete homogenization) and then immediately centrifuged. The harvested samples were collected at the bottom of the tubes. Liquid tissue samples did not require homogenization. Homogenate or liquid tissue samples (200 μL) were added to the bottom of the wells of a MagNA Pure 96 Nucleic Acid Purification System (Roche). The actual volume added was accurately recorded and 1× PBS was added to reach a total volume of 200 μL if the sample volume was insufficient. DNA was extracted using a kit (MagNA Pure 96 DNA and Viral NA Large Volume Kit, Roche, #06374891001) and stored below −65°C.

The transgene was detected by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using TaqMan probes (forward primer: 5′-AAGGAGAAGCAGAGCCATGT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CAGTGGGCATGTGTGAGTTT-3′; probe: 5′-FAM-TATGTCCCACCGGGCCCGGG-BHQ1-3′). The qPCR method was validated; the validation results are shown in Table S2.

OCT examination and fundus color photography

Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% pentobarbital sodium via intraperitoneal injection, and their pupils were dilated using Mydrin-p (Compound Tropicamide Eye Drops, one to two drops/eye). OCT was performed using a Micron IV retinal imaging system (Phoenix Micron IV). A rapid linear scan centered on the injection site was conducted to obtain images so as to prove the completion of dose administration. OCT and fundus photography were performed at the same time during examination. After the operation, one to two drops of ofloxacin eye ointment were given to animals to prevent infection.

For monkey OCT examination, monkeys were anesthetized with 2.5% pentobarbital sodium (approximately 25 mg/kg) or 5% ketamine (10–15 mg/kg) via intravenous injection (dosage was adjusted according to the anesthesia condition of animals), and their pupils were dilated using Mydrin-p (Compound Tropicamide Eye Drops, eye instillation, one to two drops/eye). A rapid linear scan centered on the injection site was conducted to obtain images so as to prove the completion of dose administration. After the operation, one to two drops of loxacin eye ointment were given to animals to prevent infection.

Slit lamp and fundus examinations

Monkeys were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (intramuscular injection, 10–15 mg/kg), Zoletil 50 (intramuscular injection, 4–6 mg/kg), or pentobarbital sodium (intravenous injection, approximately 25 mg/kg, which can be adjusted according to the anesthesia condition of animals). The mydriasis was conducted using Mydrin-p (eye instillation, 1–2 drops/eye). The slit lamp microscope was used for the examinations of monkey anterior segments for the structure of conjunctiva, cornea, anterior chamber, iris, and lens. The slit lamp microscope and slit lamp indirect ophthalmoscopy or binocular indirect ophthalmoscope were used to evaluate vitreous body, optic disk, macula lutea, retina, and retinal vessels.

Anti-AAV8 neutralizing antibody assay

The samples (serum) were heated at 56°C for 30 min, cooled to room temperature, and then diluted 10-fold with DMEM/F12 complete medium. Next, 60 μL of diluted sample and 60 μL of 2 × 1011 vg/mL KH631-AAV-Luc were mixed in a 96-well plate. The same volume of complete medium was added. Then, the plate was placed in a CO2 incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 1 h. Next, 50 μL of co-incubated solution was added to ARPE-19 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) in a 96-well cell culture plate, which was placed in a CO2 incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 24 h. Each sample was tested in duplicate. Luciferase assay reagent (Beyotime, #06102121092) was brought to room temperature. The 96-well plate was taken out of the incubator and also brought to room temperature. Next, 100 μL of cell lysis buffer from the kit was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for approximately 5 min to stabilize the chemiluminescence signal. RLU values were determined using the chemiluminescence detection mode of a multimode microplate reader.

NAb blockade (blockade, %) is the signal inhibition ratio, a value to determine whether the ADA-positive serum samples are NAb-positive. NAb blockade of ≥50% indicates samples are NAb-positive; otherwise, samples are considered NAb-negative.

Laser-induced CNV and FFA

At 28 days post-injection, CNV was induced in the area surrounding the macular area by laser photocoagulation. Monkeys were anesthetized and a small volume of ofloxacin eye ointment was given to animals at irregular intervals so as to keep the cornea wet during anesthesia. Bilateral eyes were dilated using Mydrin-p (Compound Tropicamide Eye Drops). The monkey’s head was secured in front of the ophthalmic laser photocoagulation instrument, and panretinal photocoagulation was conducted for the perimacular region. The photocoagulation avoided the macula central fovea. Six laser spots were applied around the macula of each eye in the manner of a grid with a spot diameter of 50 μm, a power of 0.5–0.7 W, and an exposure time of 0.05 s.

Changes in retinal thickness after laser photocoagulation were examined. Retinal thickness was defined as the thickness from the internal limiting membrane to Bruch’s membrane. After establishing laser-induced choroidal neovascularization, retinal thickness would increase due to the abnormal permeability of pathologic neovascularization. Retinal thickness was mapped using Heidelberg Eye Explorer (HEYEX) software adapted to the Heidelberg Spectralis OCT.

For FFA, monkeys were anesthetized with 2.5% pentobarbital sodium (25 mg/kg) and/or 5% ketamine (10 mg/kg) via intravenous injection, and their pupils were dilated using Mydrin-p (Compound Tropicamide Eye Drops, one to two drops/eye). After fundus photographing, monkeys were quickly injected with fluorescein sodium (20 mg/kg) via saphenous veins of the lower limb (or other suitable sites). Both early-phase (within approximately 1 min) and late-phase (after approximately 5 min) fundus angiograms were acquired. After the operation, one to two drops of ofloxacin eye ointment were given to animals to prevent infection.

Graded scoring of angiograms was performed on fluorescein angiogram series collected at 2 and 4 weeks after laser treatment by a masked investigator. Fluorescein leakage was graded by a masked investigator using the following grading scale: grade I, spots not noted with hyperfluorescence; grade II, spots noted with hyperfluorescence, but without fluorescein leakage; grade III, spots noted with hyperfluorescence and slight fluorescein leakage within the spot edge; grade IV, spots noted with hyperfluorescence and significant fluorescein leakage beyond the spot edge. Each group was composed of four to six evaluable eyes. There were four eyes in the 1 × 1010 vg/eye group and the 3 × 1010 vg/eye group, five eyes in the 3 × 108 vg/eye group, and six eyes in all other groups.

The percentage of grade IV CNV lesions in each assessable eye was calculated as follows: percentage of grade IV CNV lesions = the absolute number of grade IV lesions ÷ the total number of assessable lesions.

Statistical evaluation

Experiments were assessed for significance using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test, unless noted otherwise.50 All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to all comparisons.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Chengdu Origen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The authors thank Yafei Zhang and Yangyi Du for technical support; Fan Yang for test vector production; and Yinying Yang for the help in manuscript revision.

Author contributions

X.K., H.J., Q.L., and Q.Z. designed and executed experiments related to NHPs. S.L. and Y.Q. designed and executed mouse experiments. J.L. performed measurements of transgene expression and the biochemical and physiological properties of rAAV. H.J. analyzed data, performed statistical analyses, created figures, and wrote the first draft. S.L., Q.L., and Q.X. edited the manuscript. X.K., H.J., and Q.Z. supervised all the animal experiments and measurements. H.J. and S.L. revised the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

X.K., H.J., Q.L., S.L., Y.Q., J.L., Q.X., and Q.Z. are employees of Chengdu Origen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. X.K., H.J., and Q.Z. are inventors on a patent covering this work, which has been licensed to Chengdu Origen Biotechnology.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.09.019.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data on the structure of KH631 are available from the patent WO2022/051537 A1.

References

- 1.Fleckenstein M., Keenan T.D.L., Guymer R.H., Chakravarthy U., Schmitz-Valckenberg S., Klaver C.C., Wong W.T., Chew E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021;7:31. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong W.L., Su X., Li X., Cheung C.M.G., Klein R., Cheng C.-Y., Wong T.Y. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2014;2:e106–e116. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mettu P.S., Allingham M.J., Cousins S.W. Incomplete response to Anti-VEGF therapy in neovascular AMD: Exploring disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021;82 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regula J.T., Lundh von Leithner P., Foxton R., Barathi V.A., Cheung C.M.G., Bo Tun S.B., Wey Y.S., Iwata D., Dostalek M., Moelleken J., et al. Targeting key angiogenic pathways with a bispecific CrossMAb optimized for neovascular eye diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:1265–1288. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang S., Li T., Jia H., Gao M., Li Y., Wan X., Huang Z., Li M., Zhai Y., Li X., et al. Targeting C3b/C4b and VEGF with a bispecific fusion protein optimized for neovascular age-related macular degeneration therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon S.D., Lindsley K., Vedula S.S., Krzystolik M.G., Hawkins B.S. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;3:CD005139. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005139.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heier J.S., Brown D.M., Chong V., Korobelnik J.-F., Kaiser P.K., Nguyen Q.D., Kirchhof B., Ho A., Ogura Y., Yancopoulos G.D., et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2537–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plyukhova A.A., Budzinskaya M.V., Starostin K.M., Rejdak R., Bucolo C., Reibaldi M., Toro M.D. Comparative Safety of Bevacizumab, Ranibizumab, and Aflibercept for Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Direct Comparative Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1522. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D., Tai P.W.L., Gao G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:358–378. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C., Samulski R.J. Engineering adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020;21:255–272. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naso M.F., Tomkowicz B., Perry W.L., Strohl W.R. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31:317–334. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grishanin R., Vuillemenot B., Sharma P., Keravala A., Greengard J., Gelfman C., Blumenkrantz M., Lawrence M., Hu W., Kiss S., Gasmi M. Preclinical Evaluation of ADVM-022, a Novel Gene Therapy Approach to Treating Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Fortmann S.D., Shen J., Wielechowski E., Tretiakova A., Yoo S., Kozarsky K., Wang J., Wilson J.M., Campochiaro P.A. AAV8-antiVEGFfab Ocular Gene Transfer for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.4DMT Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial of Intravitreal 4D-150 in Patients with Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2023. https://4dmt.gcs-web.com/static-files/3210740f-2ae4-40e5-9909-494e4f45b9dd

- 15.Campochiaro P.A. Gene Therapy for Neovascular AMD:Subretinal RGX-314: Phase I/IIa Long-Term Follow-Up Results up to 4 Years. 2022. https://www.regenxbio.com/getmedia/1ddb1b73-e398-4366-999d-4ce04562c7dd/RGX-314-AAO2022-SR-LTFU_Peter-C_FINAL_.pdf?ext=.pdf

- 16.Regillo C. ADVM-022 (Ixoberogene Soroparvovec) Intravitreal Gene Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: End of Study Results from the 2-Year OPTIC Trial. 2022. https://adverum.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ADVM-Retina-Society-OPTIC-2022.pdf

- 17.ADVERUM Adverum Provides Update on ADVM-022 and the INFINITY Trial in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. 2021. https://investors.adverum.com/news/news-details/2021/Adverum-Provides-Update-on-ADVM-022-and-the-INFINITY-Trial-in-Patients-with-Diabetic-Macular-Edema/default.aspx

- 18.Ferro Desideri L., Traverso C.E., Nicolò M. An update on conbercept to treat wet age-related macular degeneration. Drugs Today. 2020;56:311–320. doi: 10.1358/dot.2020.56.5.3137164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J., Liang Y., Xie J., Li D., Hu Q., Li X., Zheng W., He R. Conbercept for patients with age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:142. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0807-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandenberghe L.H., Bell P., Maguire A.M., Cearley C.N., Xiao R., Calcedo R., Wang L., Castle M.J., Maguire A.C., Grant R., et al. Dosage thresholds for AAV2 and AAV8 photoreceptor gene therapy in monkey. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:88ra54. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002103. 88ra54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irigoyen C., Amenabar Alonso A., Sanchez-Molina J., Rodríguez-Hidalgo M., Lara-López A., Ruiz-Ederra J. Subretinal Injection Techniques for Retinal Disease: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:4717. doi: 10.3390/jcm11164717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rayaprolu V., Kruse S., Kant R., Venkatakrishnan B., Movahed N., Brooke D., Lins B., Bennett A., Potter T., Mckenna R., et al. Comparative analysis of adeno-associated virus capsid stability and dynamics. J. Virol. 2013;87:13150–13160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01415-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James M.W., Stephen Y., Sherri V.E. 2019. Compositions for treatment of wet age-Related macular degeneratoin. Patent WO2019164854A1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avery R.L., Castellarin A.A., Steinle N.C., Dhoot D.S., Pieramici D.J., See R., Couvillion S., Nasir M.A., Rabena M.D., Maia M., et al. Systemic pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravitreal aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab. Retina. 2017;37:1847–1858. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett J., Ashtari M., Wellman J., Marshall K.A., Cyckowski L.L., Chung D.C., Mccague S., Pierce E.A., Chen Y., Bennicelli J.L., et al. AAV2 gene therapy readministration in three adults with congenital blindness. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:120ra15. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes C., Scheideler O., Schaffer D. Engineering the AAV capsid to evade immune responses. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019;60:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalwadi D.A., Calabria A., Tiyaboonchai A., Posey J., Naugler W.E., Montini E., Grompe M. AAV integration in human hepatocytes. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2898–2909. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnepp B.C., Jensen R.L., Chen C.-L., Johnson P.R., Clark K.R. Characterization of adeno-associated virus genomes isolated from human tissues. J. Virol. 2005;79:14793–14803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14793-14803.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dismuke D.J., Tenenbaum L., Samulski R.J. Biosafety of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2013;13:434–452. doi: 10.2174/15665232113136660007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell P., Liew G., Gopinath B., Wong T.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2018;392:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31550-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samanta A., Aziz A.A., Jhingan M., Singh S.R., Khanani A.M., Chhablani J. Emerging Therapies in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration in 2020. Asia. Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2020;9:250–259. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu K., Song Y., Xu G., Ye J., Wu Z., Liu X., Dong X., Zhang M., Xing Y., Zhu S., et al. Conbercept for Treatment of Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration: Results of the Randomized Phase 3 PHOENIX Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019;197:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu X., Sun X. Profile of conbercept in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015;9:2311–2320. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S67536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X., Xu G., Wang Y., Xu X., Liu X., Tang S., Zhang F., Zhang J., Tang L., Wu Q., et al. Safety and efficacy of conbercept in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results from a 12-month randomized phase 2 study: AURORA study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1740–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding K., Shen J., Hafiz Z., Hackett S.F., Silva R.L.E., Khan M., Lorenc V.E., Chen D., Chadha R., Zhang M., et al. AAV8-vectored suprachoroidal gene transfer produces widespread ocular transgene expression. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:4901–4911. doi: 10.1172/JCI129085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khanani A.M., Thomas M.J., Aziz A.A., Weng C.Y., Danzig C.J., Yiu G., Kiss S., Waheed N.K., Kaiser P.K. Review of gene therapies for age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 2022;36:303–311. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01842-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.High-dose AAV gene therapy deaths. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:910. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khabou H., Cordeau C., Pacot L., Fisson S., Dalkara D. Dosage Thresholds and Influence of Transgene Cassette in Adeno-Associated Virus-Related Toxicity. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018;29:1235–1241. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bucher K., Rodríguez-Bocanegra E., Dauletbekov D., Fischer M.D. Immune responses to retinal gene therapy using adeno-associated viral vectors - Implications for treatment success and safety. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021;83 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Q., Huang W., Zhang H., Wang Y., Zhao J., Song A., Xie H., Zhao C., Gao D., Wang Y. Neutralizing antibodies against AAV2, AAV5 and AAV8 in healthy and HIV-1-infected subjects in China: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Gene Ther. 2014;21:732–738. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krader C.G. Novel Gene Therapy for Neovascular AMD Showing Efficacy, Safety. 2021. https://www.ophthalmologytimes.com/view/novel-gene-therapy-for-neovascular-amd-showing-efficacy-safety

- 42.Kaiser S.M., Arepalli S., Ehlers J.P. Current and Future Anti-VEGF Agents for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2021;13:905–912. doi: 10.2147/JEP.S259298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veritti D., Sarao V., Gorni G., Lanzetta P. Anti-VEGF Drugs Dynamics: Relevance for Clinical Practice. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:265. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14020265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Do D.V., Rhoades W., Nguyen Q.D. Pharmacokinetic study of intravitreal aflibercept in humans with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2020;40:643–647. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krohne T.U., Liu Z., Holz F.G., Meyer C.H. Intraocular pharmacokinetics of ranibizumab following a single intravitreal injection in humans. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012;154:682–686.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H., Lei N., Zhang M., Li Y., Xiao H., Hao X. Pharmacokinetics of a long-lasting anti-VEGF fusion protein in rabbit. Exp. Eye Res. 2012;97:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crowell S.R., Wang K., Famili A., Shatz W., Loyet K.M., Chang V., Liu Y., Prabhu S., Kamath A.V., Kelley R.F. Influence of Charge, Hydrophobicity, and Size on Vitreous Pharmacokinetics of Large Molecules. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019;8:1. doi: 10.1167/tvst.8.6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rashnonejad A., Chermahini G.A., Li S., Ozkinay F., Gao G. Large-Scale Production of Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Serotype-9 Carrying the Human Survival Motor. Mol. Biotechnol. 2016;58:30–36. doi: 10.1007/s12033-015-9899-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao G., Tai P., Punzo C. 2021. Adeno-associated virus for delivery of KH902 (conbercept) and uses thereof. Patent PCT/US2021/048917. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang H., Wang Q., Li L., Zeng Q., Li H., Gong T., Zhang Z., Sun X. Turning the old adjuvant from gel to nanoparticles to amplify CD8+ T cell responses. Adv. Sci. 2018;5 doi: 10.1002/advs.201700426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data on the structure of KH631 are available from the patent WO2022/051537 A1.