Abstract

Current asthma therapies focus on reducing symptoms but fail to restore existing structural damage. Mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) administration can ameliorate airway inflammation and reverse airway remodeling. However, differences in patient disease microenvironments seem to influence MSC therapeutic effects. A polymorphic CATT tetranucleotide repeat at position 794 of the human macrophage migration inhibitory factor (hMIF) gene has been associated with increased susceptibility to and severity of asthma. We investigated the efficacy of human MSCs in high- vs. low-hMIF environments and the impact of MIF pre-licensing of MSCs using humanized MIF mice in a clinically relevant house dust mite (HDM) model of allergic asthma. MSCs significantly attenuated airway inflammation and airway remodeling in high-MIF-expressing CATT7 mice but not in CATT5 or wild-type littermates. Differences in efficacy were correlated with increased MSC retention in the lungs of CATT7 mice. MIF licensing potentiated MSC anti-inflammatory effects at a previously ineffective dose. Mechanistically, MIF binding to CD74 expressed on MSCs leads to upregulation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression. Blockade of CD74 or COX-2 function in MSCs prior to administration attenuated the efficacy of MIF-licensed MSCs in vivo. These findings suggest that MSC administration may be more efficacious in severe asthma patients with high MIF genotypes (CATT6/7/8).

Keywords: mesenchymal stromal cells, house dust mite, allergic asthma, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, cyclooxygenase

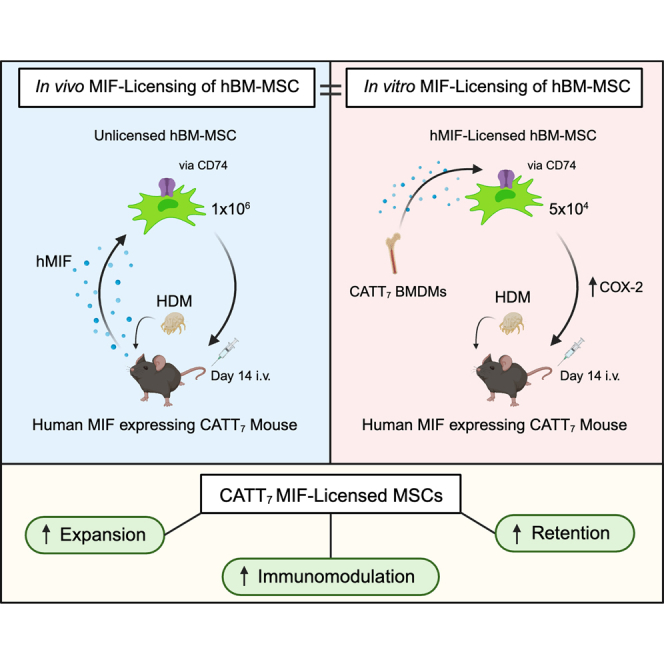

Graphical abstract

English and colleagues discuss how mesenchymal stromal cells significantly attenuated house dust mite-induced airway inflammation and airway remodeling in high-MIF-expressing CATT7 mice. Blockade of CD74 or COX-2 function in MSCs prior to administration attenuated the efficacy of MIF-licensed MSCs in vivo.

Introduction

Allergic asthma is characterized by chronic airway inflammation and airway remodeling, which refers to the structural changes in the airways. Currently, there is a heavy reliance on inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists in the treatment of allergic asthma. The recent introduction of novel biologics, such as benralizumab and dupilumab targeting Th2 cytokine receptors and tezepelumab targeting the alarmin thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), have been shown to significantly reduce allergic airway inflammation, leading to reduced exacerbation and improved forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1) values.1,2,3,4 However, not all patients are responders, and evidence for biologics to reverse existing airway remodeling in patients is limited so far.5 Thus, there is scope for novel therapeutics with the capacity to attenuate inflammation and reverse remodeling to address the pitfalls in the current treatment and management of allergic asthma.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have immunomodulatory and anti-fibrotic properties and proven therapeutic effects in a range of allergic airway inflammation models and are currently under investigation in two clinical trials for asthma (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05147688 and NCT05035862). Administration of MSCs intratracheally or intravenously has been shown to be effective in reducing airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in ovalbumin (OVA),6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 house dust mite (HDM),18,19,20,21,22,23,24 and Aspergillus hyphal extract25,26 models. However, other studies have failed to demonstrate efficacy in experimental asthma models.7,14,23,24,27,28 To understand the mechanisms involved and to make MSCs a viable therapeutic in the clinic, more focused translational work is needed.

Under basal conditions (for example, in healthy animals or individuals), MSC administration does not seem to alter immunological status or function (homeostasis is preserved). MSCs only become licensed to an anti-inflammatory phenotype in the presence of extrinsic factors.29 When licensed, MSCs modulate their surrounding microenvironment.30 Importantly, their therapeutic effect is blunted in the presence of interferon γ (IFNγ), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) receptor blockade/inhibition.31,32,33 Moreover, in the absence of appropriate signals to license anti-inflammatory functions, MSCs may even exacerbate disease.34,35,36 Licensing has been shown to improve MSC therapeutic efficacy by activating MSC anti-inflammatory characteristics prior to administration. Licensing through exposure to hypoxia,37,38 inflammatory cytokines,39,40 and pharmacological factors41 has been shown to improve MSC efficacy in a range of inflammatory diseases. Moreover, licensing of MSCs with serum from HDM-challenged mice18 or with serum from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients42 enhanced MSC therapeutic efficacy in vivo in pre-clinical lung disease models. However, there are also in vitro studies reporting differential and, in some cases, negative effects of patient samples (ARDS versus cystic fibrosis (CF)) on MSC survival and function.42,43,44

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is an important regulator of host inflammatory responses, demonstrated by its ability to promote the production of other inflammatory mediators. For example, MIF has been shown to amplify the expression of TNF, IFNγ, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8 from immune cells.45,46,47,48 This augmentation of immune signals contributes to MIF-mediated pathogenesis by acting to sustain inflammatory responses. This has been shown in a range of inflammatory diseases where the absence of MIF is associated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in reduced pathology. For example, MIF knockout (MIF−/−) mice display a less severe phenotype when exposed to OVA compared with control mice,49,50,51,52 and the use of anti-MIF antibodies or a small-molecule inhibitor (ISO-1) results in reduced Th2 cytokines in models of allergic airway inflammation.51,53,54,55,56 High levels of MIF as a result of longer CATT repeats, such as CATT7, have been shown to increase severity in a range of diseases, including severe anemia,57 pneumococcal meningitis,58 multiple sclerosis,59 tuberculosis,60 and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).61 Importantly, associations between the CATT polymorphism and asthma incidence and severity have been observed.52 Not only do these studies show the pivotal role that MIF plays in pro-inflammatory diseases, they also affirm the importance of differences in the MIF CATT polymorphism.

Our previous work established a dominant role of MIF allelic variants in the severity of HDM-induced allergic asthma.62 Using humanized high-expressing and low-expressing MIF mice in an HDM model of allergic airway inflammation, we demonstrated the pivotal role MIF plays in exacerbating asthma pathogenesis. High levels of human MIF resulted in a significant increase in airway inflammation as a result of elevated levels of Th2 cytokines promoting infiltration of eosinophils into the airways. Furthermore, high levels of MIF were associated with airway remodeling with significant mucus hyperplasia, subepithelial collagen deposition, and airway hyperresponsiveness generating a more severe asthma phenotype. MIF has been shown to promote MSC migration in vitro;63 however, the effect of MIF on MSC immunosuppressive function or therapeutic efficacy in vivo is unknown. Here, we sought to investigate the relationship between MIF and MSCs in vivo and to define conditions for optimal MSC therapeutic efficacy. High-MIF-expressing CATT7, low-MIF-expressing CATT5, and wild-type (WT) mice were used as a platform to investigate the role of MIF on MSC efficacy in a clinically relevant HDM-induced mouse model of allergic airway inflammation.

Results

Human bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) significantly reduce airway remodeling in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM

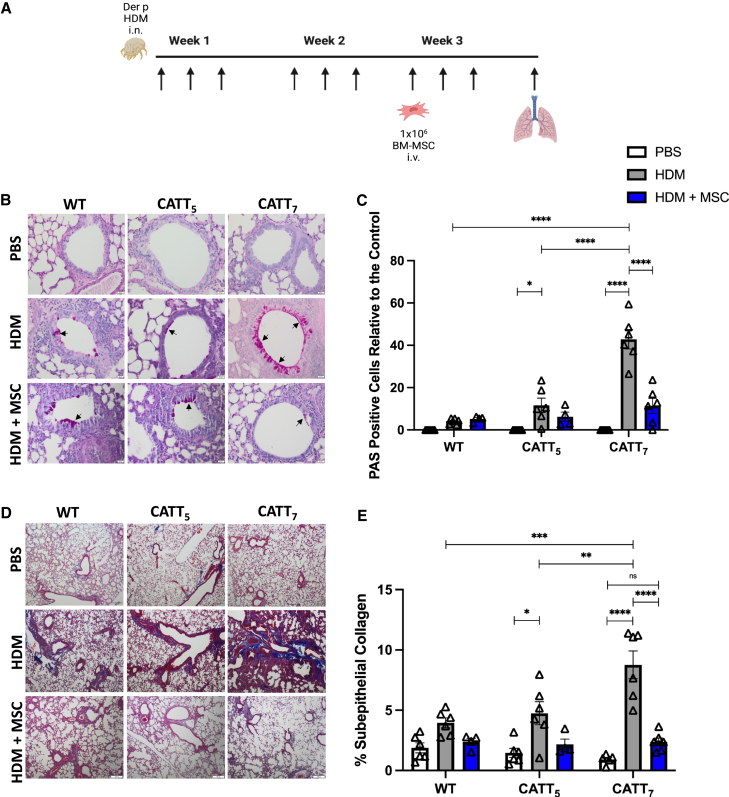

First, to investigate the impact of high- and low-expressing MIF alleles on MSC treatment of allergic airway inflammation, we examined the lung histology. CATT7, CATT5, and the WT were randomized to HDM or mock (saline) intranasally 3 times a week for 3 weeks. Mice were then further randomized to 1 × 106 human BM-MSCs or equal-volume saline administered via tail vein injection on day 14. On day 21, lung tissue was removed, formalin fixed, and sectioned onto slides (Figure 1A). Slides were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) to highlight mucin production to assess the level of goblet cell hyperplasia. CATT7 mice exhibit significantly higher levels of goblet cell hyperplasia compared with WT and CATT5 mice. Administration of BM-MSCs reduced the level of goblet cell hyperplasia in all groups to almost background levels, with a significant reduction in the number of mucin-secreting cells in the airways of HDM-challenged CATT7 mice (Figures 1B and 1C).

Figure 1.

Human BM-MSCs significantly reduce goblet cell metaplasia and collagen deposition in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM

(A) PBS and HDM groups received PBS or HDM i.n. 3 times a week for 3 consecutive weeks. 1 × 106 human BM-MSCs were administered i.v. to the HDM+MSC groups on day 14. Mice were sacrificed on day 21 (schematic created with BioRender). (B) Representative images of lung tissue from WT, CATT5, and CATT7 mice stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) at 20× magnification; scale bar, 20 μm. Arrows show examples of mucin-containing goblet cells. (C) Goblet cell hyperplasia was investigated through the quantitation of PAS-positive cells. (D) Representative images of lung tissue stained with Masson’s trichome at 4× magnification; scale bar, 200 μm.

(E) Quantitation of the percentage of subepithelial collagen. Data are presented as mean SEM; n = 6 per group. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177 and 003-310 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, non-significant.

Subepithelial fibrosis was significantly increased in HDM-challenged CATT7 mice compared with the lower-MIF-expressing CATT5 and WT groups. BM-MSC administration reduced the level of subepithelial fibrosis to almost background levels in all groups, with significantly reduced subepithelial collagen deposition in HDM-challenged CATT7 mice (Figures 1D and 1E). In CATT5 and WT mice challenged with HDM, BM-MSC administration had a small but not significant therapeutic effect. BM-MSC administration significantly mitigated increased inflammatory infiltrate and H&E pathological score in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM (Figure S1).

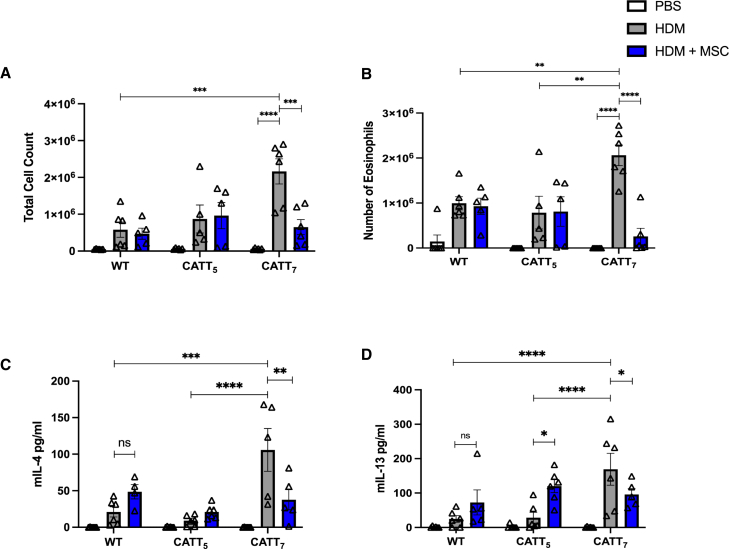

Human BM-MSCs significantly reduce airway inflammation in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM

Total cell counts were significantly elevated in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of CATT7 mice following HDM challenge (Figure 2A). MSCs significantly reduced the number of total infiltrating cells in the BALF of CATT7 mice (Figure 2A). Differential cell counts identified eosinophils as the main cells infiltrating the lung tissue following HDM challenge, and MSCs significantly decreased infiltrating eosinophils in CATT7 mice but had no effect in the CATT5 and WT groups (Figure 2B). IL-4 and IL-13 were significantly elevated in the BALF of CATT7 mice following HDM challenge (Figures 2C and 2D). These Th2 cytokines are not significantly upregulated in CATT5 or WT mice. While MSCs significantly decreased IL-4 and IL-13 in CATT7 mice, MSC treatment did not reduce and, in some cases, increased Th2 cytokines in the BALF of CATT5 and WT mice (Figures 2C and 2D). These data show that BM-MSCs are effective at alleviating eosinophil infiltration and reducing Th2 cytokines in a high-MIF-expressing model of allergic asthma and that MSCs require a threshold level of inflammation to mediate their therapeutic effects.

Figure 2.

Human BM-MSCs significantly reduce levels of Th2 cytokines in the BALF of CATT7 mice challenged with HDM

PBS and HDM groups received PBS or HDM i.n. 3 times a week for 3 consecutive weeks. 1 × 106 human BM-MSCs were administered i.v. to the HDM+MSC groups on day 14. BAL was performed 4 h post final HDM challenge on day 18. (A) Total cell count recovered from the BALF.

(B) BALF eosinophil count, determined by differential staining of cytospins. (C and D) Cytokine levels of (C) IL-4 and (D) IL-13 in the BALF, determined by ELISA. White bars, PBS; gray bars, HDM blue bars, HDM+MSC. Data are presented as mean SEM; n = 5–6 per group. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177 and 003-310 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

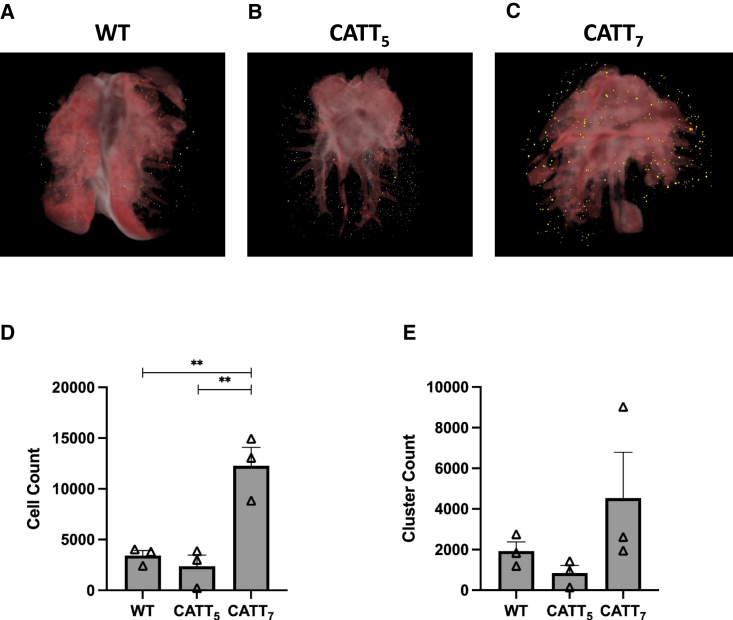

High levels of human MIF (hMIF) significantly enhance BM-MSC retention in an HDM model of allergic asthma

Next, we analyzed the biodistribution of MSCs following administration into HDM-challenged WT, CATT5, and CATT7 mice. 1 × 106 fluorescently labeled BM-MSCs were administered intravenously (i.v.) via tail vein injection on day 14. On day 15, mice were sacrificed, and the lungs were prepared for CryoViz imaging (Figures 3A–3C). Significantly higher numbers of labeled MSCs were detected in the lungs of high-MIF-expressing CATT7 mice compared with the low-expressing CATT5 or WT littermate control (Figures 3C and 3D). However, the number of clusters of labeled BM-MSCs within the lungs remained unchanged among the groups (Figure 3E). Taken together, these data suggest that prolonged MSC pulmonary retention time increases the number of MSCs retained at the site of inflammation 24 h post administration. These data suggest that high levels of MIF may provide a longer window for MSCs to carry out their therapeutic effects.

Figure 3.

High levels of hMIF significantly enhance BM-MSC retention in an HDM model of allergic asthma

HDM were administered i.n. 3 times a week for 2 weeks. On day 14, 1 × 106 Qtracker 625-labeled hMSCs were administered i.v. to WT, CATT5, or CATT7 mice. 24 h later the lungs were harvested, embedded in OCT compound and frozen at −80. Tissue blocks were sectioned and imaged using the CryoViz (BioInvision) imaging system. (A–C) 3D images show representative lung images from (A) WT, (B) CATT5, and (C) CATT7 mice, with detected MSCs shown in yellow. (D and E) Total number of MSCs detected in the lungs (D) and number of clusters (E) were quantified using CryoViz quantification software. Data are presented as mean SEM; n = 3 per group. Human BM-MSC donor 001-177 was used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test: ∗∗p < 0.01.

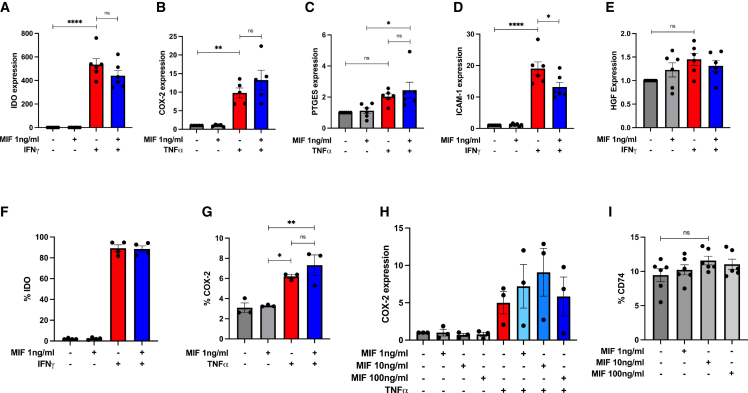

The influence of MIF on MSC expression of immunomodulatory factors and MSC cytokine licensing in vitro

MSCs mediate their therapeutic effects via expression or production of secreted factors in vitro and in vivo,64 and licensing with proinflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ οr TNF-α65,66,67,68,69 can enhance expression of immunomodulatory mediators. Here, we characterized the effect of recombinant hMIF on the expression of indolamine 2-3-dioxygenase (IDO), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), prostaglandin E synthase (PTGES), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in untreated MSCs or MSCs licensed with IFNγ or TNF-α. Recombinant hMIF (rhMIF; 1 ng/mL) stimulation alone did not increase expression of IDO, COX-2, PTGES, ICAM-1, or HGF (Figures 4A–4E) in human BM-MSCs. Following licensing with TNF-α, MIF stimulation enhanced MSC expression of COX-2 and PTGES (Figures 4B and 4C). In IFNγ-licensed MSCs, rhMIF stimulation did not enhance MSC expression of IDO or HGF and significantly reduced ICAM-1 expression (Figures 4A, 4D, and 4E). We confirmed these findings at the protein level for IDO and COX-2 using intracellular flow cytometry (Figures 4F and 4G). Using increasing doses of rhMIF (1, 10, or 100 ng/mL), we showed that COX-2 expression is increased in a dose-dependent manner by rhMIF stimulation in TNF-α-licensed MSCs, with COX-2 expression plateauing at 10 ng/mL of rhMIF (Figure 4H). The MIF receptor CD74 is expressed by MSCs; however, rhMIF stimulation (dose range 1, 10, or 100 ng/mL) does not enhance CD74 expression (Figure 4I).

Figure 4.

Influence of rhMIF licensing on MSC expression of immunomodulatory factors in vitro

(A–E) Gene expression of IDO, COX-2, PTGES, ICAM-1, and HGF by hBM-MSCs after stimulation with rhMIF (1 ng/mL), human TNF-α or human IFNγ for 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177, 003-310, and 003-307 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

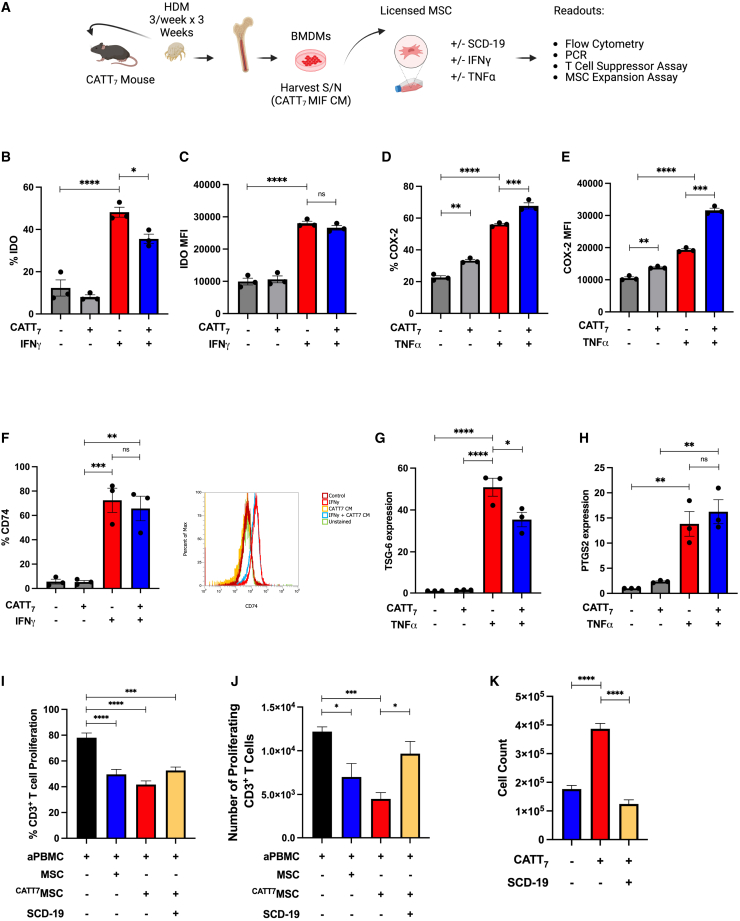

CATT7 MIF licensing enhances MSC expansion and immunosuppressive function in vitro

To investigate the effect of endogenous MIF from CATT7 mice on MSC expression of immunomodulatory factors, we generated BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from CATT7 mice and used the conditioned medium (CM) as a source of endogenous hMIF (Figure 5A) to license MSCs. The concentration of hMIF in CATT7 BMDM CM ranged from ∼3,000–4,000 pg/mL (Figure S2).

Figure 5.

CATT7 MIF licensing enhances MSC expansion and immunosuppressive function in vitro

(A) Schematic (created using BioRender) depicting the generation of CATT7 MIF CM and experimental design. (B–E) Percentage or mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IDO or COX-2 expression in human BM-MSCs, measured by flow cytometry after cells were stimulated with CATT7 MIF CM, human TNF-α, or human IFNγ for 24 h. (F) Percentage expression and representative histogram plots of CD74 surface expression on human MSCs, measured by flow cytometry after cells were stimulated with CATT7 MIF CM and human IFNγ for 24 h. (G and H) Relative gene expression of TSG-6 and PTGS2 by hBM-MSCs after cells were stimulated with endogenous hMIF (CATT7 CM) and human TNF-α for 6 h. (I and J) Licensing of MSCs with supernatants generated from BMDMs from CATT7 HDM-challenged mice enhances MSC suppression of (I) frequency (percent) and (J) absolute number of CD3+ T cells proliferating. Blockade of MIF using SCD-19 (100 μM) in the BMDM supernatants 1 h before addition to MSCs abrogates the enhanced effect of MIF on MSC suppression of T cell proliferation.

(K) Licensing of MSCs with CATT7 MIF CM enhances MSC expansion in vitro. Addition of the MIF inhibitor SCD-19 (100 μM) to CATT7 MIF CM 1 h before MSC licensing prevents MIF-enhanced MSC expansion. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177, 003-310, and 003-307 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using a one-way ANOVA or unpaired t test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

MIF may have a negative role in the regulation of IDO expression as MIF−/− mice produce more IDO;70 however, MIF has an established role as an upstream positive regulator of COX-2 through activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway.71,72 IDO, COX-2, and PGE2 are widely reported mediators of MSC immunosuppression.39,73 MSCs constitutively express COX-2 but not IDO. IFNγ licensing of MSCs leads to expression of IDO, while TNF-α enhances MSC COX-2 expression.68 Here we show that CATT7 MIF stimulation reduces MSC IDO production (Figures 5B and 5C); however, the percentage of COX-2 expressing MSCs was significantly increased following CATT7 MIF stimulation (Figures 5D and 5E). Human MSCs express the MIF receptor CD74, and this expression is maintained and not increased following exposure to CATT7 MIF CM (Figure 5F). In line with another study,74 we show that IFNγ stimulation leads to significantly increased MSC CD74 expression and that CATT7 MIF CM does not significantly alter that (Figure 5F). This aligns with our data showing that MIF does not enhance IFNγ-regulated IDO expression. Given the potentiating effect of MIF on the TNF-α-regulated gene COX-2 in MSCs, we examined the influence of CATT7 MIF on MSC expression of the TNF-α-regulated genes tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 (TSG-6) and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2). The presence of CATT7 MIF CM significantly reduced TSG-6 in TNF-α-stimulated MSCs (Figure 5G) but did not significantly alter the expression of PTGS2 (Figure 5H). MSCs licensed with high levels of hMIF from CATT7 CM displayed enhanced suppression of T cell proliferation compared with the untreated MSCs; however, this was not statistically significant in the frequency of proliferating CD3+ T cells (Figure 5I) or the number of proliferating CD3+ T cells (Figure 5J). The presence of SCD-19 abrogated the enhanced suppression mediated by hMIF-licensed MSCs because the number of proliferating CD3+ T cells was significantly increased compared with the CATT7MSC group (Figure 5J).

Previous studies have shown that MIF has the ability to support cell proliferation in vitro.75,76,77 Increasing the number of MSCs within the inflammatory niche could prove to be important in enhancing MSC immunoregulatory effects. High levels of MIF significantly enhanced MSC expansion in vitro compared with the complete medium control group (Figure 5K). Blockade of MIF using SCD-19 confirmed the role of MIF in driving MSC expansion (Figure 5K). These data might help to explain the enhanced retention of MSCs in CATT7 HDM-challenged mice (Figure 3), but further experiments would be required to confirm that.

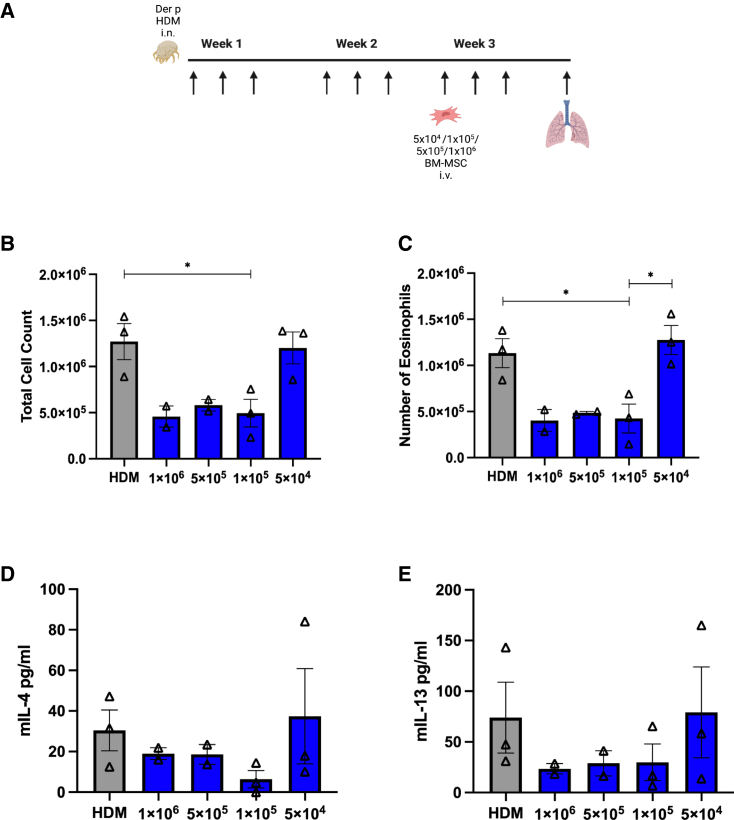

Titration of BM-MSC doses in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM

Next, we investigated whether MIF licensing could improve MSC efficacy in the high-MIF-expressing CATT7 mice challenged with HDM. To do this, we first investigated the dose at which MSCs lose efficacy. MSCs at doses of 1 × 106, 5 × 105, 1 × 105, and 5 × 104 were administered i.v. into HDM-challenged CATT7 on day 14 (Figure 6A). MSCs maintained efficacy as low as 1 × 105 cells with reduced immune cell infiltration (Figures 6B and 6C) and reduced Th2 cytokines IL-4 (Figure 6D) and IL-13 (Figure 6E). We observed that BM-MSCs were no longer able to carry out their immunosuppressive effects at a dose of 5 × 104. At 5 × 104, BM-MSCs were unable to reduce the number of eosinophils infiltrating the lungs (Figures 6B and 6C) or regulate Th2 cytokine production (Figures 6D and 6E).

Figure 6.

Titration of BM-MSC doses in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM

(A) To determine the point where MSCs lose efficacy in CATT7 mice, a range of doses were administered on day 14. BAL was performed 4 h post final HDM challenge on day 18 (schematic created with BioRender). (B) Total cell count recovered from the BALF.

(C) Number of eosinophils obtained from the BALF. (D and E) Cytokine levels of (D) IL-4 and (E) IL-13 in the BALF, determined by ELISA. Data are presented as mean SEM; n = 2–3 per group. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177 and 003-310 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test: ∗p < 0.05.

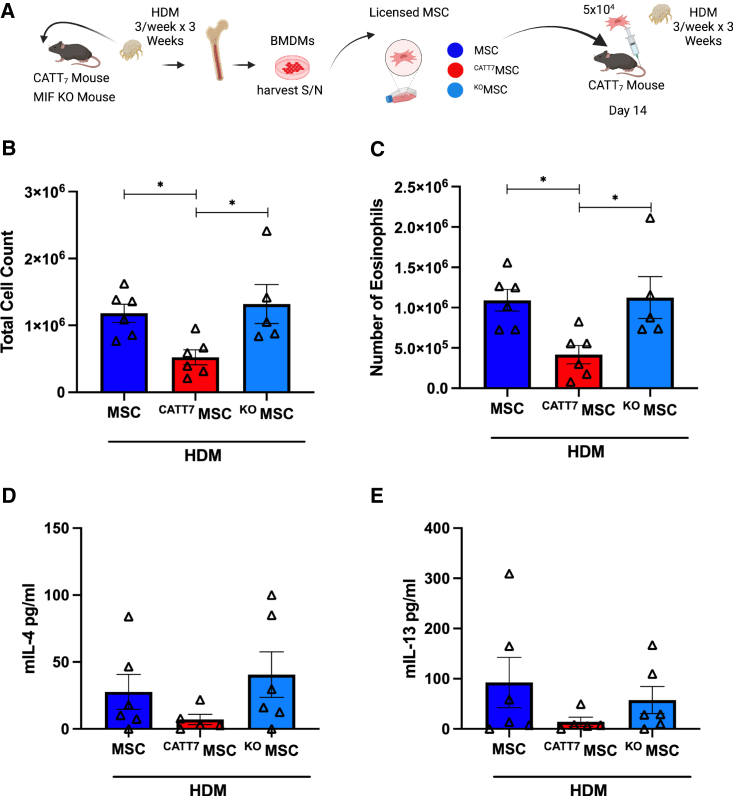

MIF licensing restores MSC efficacy at low doses in CATT7 mice

To investigate the effect of MIF licensing on MSC therapeutic efficacy, MSCs were first licensed in vitro by stimulation with BMDM CM from CATT7 or knockout (KO) mice for 24 h 5 × 104 MSCs, MIF-licensed MSCs (CATT7MSC), or MIF KO-licensed MSCs (KOMSC) were administered i.v. into CATT7 mice via tail vein injection on day 14 in HDM-challenged mice. On day 18, BALF was collected, cell counts were performed, and Th2 cytokines were measured (Figure 7A). Only CATT7MSC administration significantly reduced total cell counts and the number of eosinophils in CATT7 mice challenged with HDM (Figures 7B and 7C). CATT7MSCs markedly reduced IL-4 and IL-13 levels compared with the control group although not significantly (Figures 7D and 7E). The control MSC group and the KOMSC group displayed similar levels of immune cell infiltration and Th2 cytokine production, suggesting that the effects observed in the CATT7MSC group are specific to MIF-licensed MSCs. These data show that MIF licensing can restore MSC immunosuppressive function at doses that would normally be ineffective.

Figure 7.

MIF licensing restores MSC efficacy at low doses in CATT7 mice

(A) 5 × 104 MSCs were administered to HDM-challenged CATT7 mice on day 14. CATT7MSCs were licensed with CATT7 BMDM supernatant for 24 h prior to i.v. administration. The control group KOMSCs were generated by licensing MSCs with BMDM supernatant from MIF KO mice 24 h prior to i.v. administration. BAL was performed 4 h post final HDM challenge on day 18 (schematic created with BioRender). (B and C) Total number of cells in the BALF were determined (B), and differential cell counts were performed on the collected cells to determine the numbers of eosinophils (C). (D and E) Cytokine levels of (D) IL-4 and (E) IL-13 in the BALF determined by ELISA. Data are presented as mean SEM; n = 5–6 per group. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177 and 003-310 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test: ∗p < 0.05.

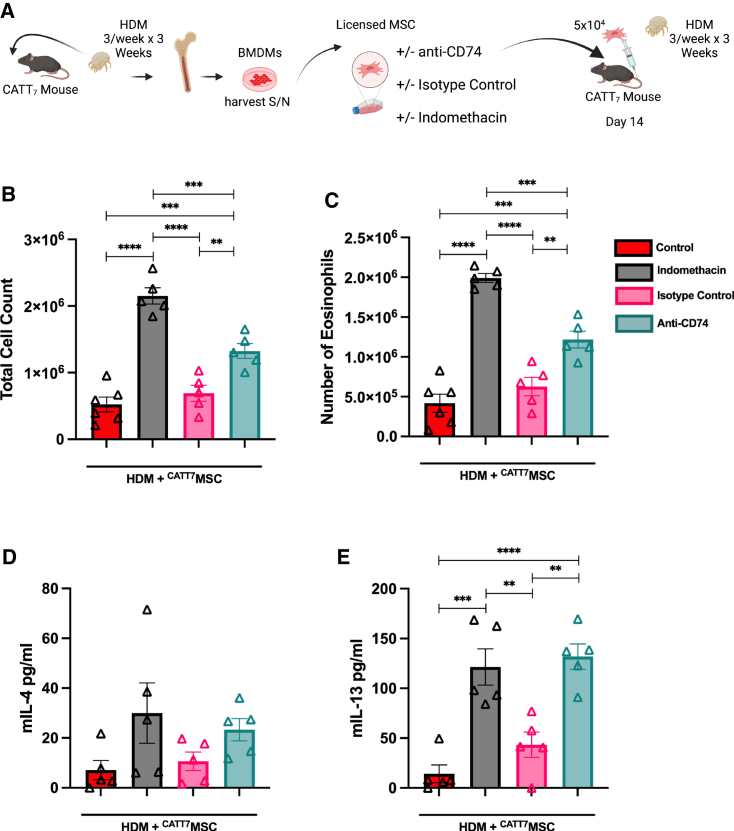

Blocking COX-2 abrogates therapeutic efficacy of MIF licensed BM-MSCs

COX-2 is the rate-limiting enzyme involved in the synthesis of arachidonic acid to PGE2, a key mediator in the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs.78 To assess the role of COX-2 on MIF-licensed MSCs, we inhibited COX-2 with indomethacin. MSCs were treated with indomethacin (10 μM) for 30 min. Following the 30-min pre-treatment, cells were incubated with CATT7 CM for 24 h. To further validate the involvement of MIF in the improvement of MSC efficacy, MSCs were exposed to an anti-CD74 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL) or immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) isotype control (10 μg/mL) for 30 min. MSCs were then incubated with CATT7 CM for 24 h (Figure 8A). Analysis of the BALF cell counts showed that pre-treating MSCs with indomethacin before administration significantly reduces CATT7MSCs’ ability to suppress immune cell infiltration in the BALF of CATT7 mice challenged with HDM (Figures 8B and 8C). Additionally, the analysis of the Th2 cytokines in the BALF showed a marked increase in IL-4 (Figure 8D) and a significant increase in the level of IL-13 (Figure 8E) in the indomethacin group compared with the control MIF-licensed MSC group. Taken together, these results show that COX-2 is an important mediator in the enhancement of therapeutic efficacy associated with MIF licensing. Furthermore, blocking of CD74 abrogates MIF licensed BM-MSC suppression of eosinophil infiltration and type 2 cytokines in the BALF (Figure 8). These data indicate that MIF enhances MSCs’ immunomodulatory capacity mainly through CD74 signaling to upregulate COX-2 production.

Figure 8.

MIF-Licensed MSCs mediate their protective effects in HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation in a CD74- and COX-2-dependent manner in CATT7 mice

(A) 5 × 104 MSCs were exposed to the COX-2 inhibitor indomethacin, an anti-CD74 neutralizing antibody, or an isotype control antibody for 24 h in vitro. All MSCs were licensed with CATT7 BMDM supernatant for 24 h prior to i.v. administration. BAL was performed 4 h post final HDM challenge on day 18 (schematic created with BioRender). (B and C) Total number of cells in the BALF were determined (B), and differential cell counts were performed on the collected cells to determine the numbers of eosinophils (C). (D and E) Cytokine levels of (D) IL-4 and (E) IL-13 in the BALF, determined by ELISA. Data are presented as mean SEM; n = 5–6 per group. Human BM-MSC donors 001-177 and 003-310 were used (RoosterBio). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test: ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Our main results advance the field of MSC-based therapeutics for asthma by demonstrating that (1) MSC treatment is highly effective in ameliorating airway inflammation; (2) their therapeutic potential can be enhanced by MSC-MIF licensing, as demonstrated in high-MIF-expressing CATT7 mice; and finally (3) the mechanism of MIF licensing is dependent on MSC-CD74 expression levels that drive COX-2 expression in MSCs. Our data align with the literature demonstrating the ability of human MSCs to ameliorate eosinophil infiltration by reducing the levels of Th2 cytokines.8,10,11,12,25,79 In addition to reducing inflammation, MSCs also alleviate features of airway remodeling in the CATT7 mice. Interestingly, while MSCs were effective at reducing the severity of goblet cell hyperplasia and subepithelial fibrosis in all groups, we did not observe the same changes in type 2 inflammatory markers in the BALF of WT and low-MIF-expressing CATT5 mice, suggesting that high levels of MIF may be responsible for improving MSC efficacy. The reduced efficacy of MSCs in the WT and CATT5 mice can likely be attributed to a lack of inflammation present, associated with a bias toward Th1 immunity in C57BL/6 mice compared with more Th2 bias in BALB/c mice, influencing the level of Th2 response in our HDM challenge model.80 There have been several instances where researchers also observed poor responses to MSC treatment of allergic airway inflammation in C57BL/6 mice.7,23 More recently, Castro et al.21 report the requirement of at least 2 doses of human adipose derived (AD)-MSCs to reverse airway remodeling and alleviate inflammation in HDM-challenged C57BL/6 mice.

We show that a single human MSC dose is capable of significantly decreasing airway remodeling in CATT7 mice. This suggests that high levels of MIF may facilitate activation of MSCs, improving their therapeutic efficacy and leading to reversal of airway remodeling. The literature surrounding MSCs’ effect on airway remodeling is conflicting; however, the majority of the current literature demonstrates that MSCs can attenuate airway remodeling.8,10,14,15,17,18,28 Others report a deficit in MSCs capacity to ameliorate goblet cell hyperplasia14,19,23 or subepithelial collagen deposition.9,28 Reasons for these discrepancies include the source of MSCs,8,23,81 genotypic mouse model differences, severity of the mouse models, time of infusion, MSC fitness, dosing, and route of administration.27

Our previous studies have demonstrated that pro-inflammatory cytokine licensing of MSCs or MSC-like cells; multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPCs) enhance their retention under inflammatory conditions and correlate with enhanced therapeutic efficacy.39,82 We detected significantly higher numbers of MSCs in the lungs of HDM-challenged CATT7 mice compared with CATT5 or littermate controls 24 h following administration. It has been suggested that short-term effects of MSCs are mediated by their diverse secretome and that the longer-term effects of MSC therapy are a result of direct interaction with other cell types.83 Increased longevity at the site of injury allows MSCs a longer period to secrete soluble factors and interact with cells in the inflammatory microenvironment. MSC retention in the CATT7 HDM-challenged mice is an important observation, and future work will determine whether enhanced retention is also involved in the enhanced MSC efficacy observed.

Taken together, these data suggest that MSCs are more efficacious in the high-MIF environment of CATT7 mice. By investigating the effects of different concentrations of a human cytokine on the efficacy of human MSCs in a model of allergic asthma using a clinically relevant allergen, we identified a specific disease microenvironment that supports and enhances MSC efficacy. The use of our humanized model aims to provide a more accurate depiction of how human MSCs would interact in subsets of patients compared with conventional murine models. Of course, despite exploring the effect of a human cytokine on human MSCs, there are still limitations because we are unable to fully mimic clinical severe allergic asthma, and the use of transgenic MIF mice on a C57BL/6 background meant that control WT mice do not develop a high level of type 2 inflammation. However, these results may have implications for tailoring MSC treatment in cases of severe asthma. Our results have demonstrated that MSCs are less efficacious in low-MIF environments. Patients with 5/5 haplotypes tend to have lower levels of circulating MIF84 and therefore may not respond as well to MSC treatment. Patients with 6/6, 7/7, or 8/8 haplotypes are more likely to have high levels of circulating MIF,52,85,86 which may lead to greater MSC activation and enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

Following the discovery that MSC administration into CATT7 mice led to improved MSC efficacy, we investigated strategies to use high-MIF microenvironments to potentiate the effects of MSCs. Past work in our lab has focused on different licensing strategies of MSCs to enhance MSC efficacy. Previously, we have demonstrated how IFNγ licensing can improve MSC efficacy in a humanized model of acute graft versus host disease (GvHD) and how endogenous factors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) δ ligands or treatments like cyclosporine A can influence this.39,40 Other studies have shown how licensing with pharmacological agents or endogenous factors can further enhance the effects of MSC therapy in preclinical models of asthma.18,19,87

One of the main criticisms of preclinical research is the use of doses that far exceed what would be reasonable in the clinic. Analysis of clinical trials using i.v. injection of MSCs reveals that the minimal effective dose used ranges from 1–2 million cells/kg.88 Studies that have investigated i.v. administration of MSCs in preclinical models of allergic asthma, administering doses that equate to 4–40 million cells/kg, with the majority at the higher end of the scale.8,10,12,16,20,21,22,25,26,28,79,89,90,91,92 The efficacy observed with MIF-licensed MSCs using 5 × 104 cells per mouse results in an effective dose of 2 million cells/kg. This shows that, through MIF licensing, we are able to restore MSC efficacy at a dose akin to what is used in clinical trials.

We then sought to elucidate the mechanisms involved. Given our use of human MSCs in a mouse host, the interspecies ligand/receptor non-functionality can raise questions about how human MSCs might mediate their effects in a mouse host. We and others have shown that human MSCs can indeed mediate protective effects in mouse hosts.8,10,11,12,14,15,16,17,21,24,25,33,93 Four studies have tracked human MSC biodistribution following i.v. administration in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),94 liver cirrhosis,95 hemophilia A,96 or breast cancer.97 No MSCs were detected in the blood 1 h post infusion. MSCs were distributed mainly in the lungs95 or lungs and liver96 48 h post i.v. infusion, with the signal decreasing thereafter. Therefore, these studies suggest that biodistribution of human MSCs following i.v. administration in humans aligns with the studies investigating MSC biodistribution in mouse models.98

In terms of mechanism, MIF-mediated signal transduction is primarily initiated by binding to MIF’s classical receptor, CD74.99 We showed that blocking CD74 on the surface of MSCs ultimately abolished their immunosuppressive abilities. These findings not only reaffirmed that the licensing with CATT7 CM was MIF mediated, but it also showed that these effects were dependent on binding to CD74. MIF signal transduction through CD74 binding has been shown to initiate a range of signaling pathways that induce cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and the promotion of repair.100,101,102,103,104 Furthermore, MIF binding to CD74 has been shown to activate cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). Moreover, cPLA2 activation results in the mobilization of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, which is a precursor to the synthesis of prostaglandins.105 Interestingly, MIF can upregulate COX-2 expression, a rate-limiting step in the synthesis of prostaglandins such as PGE2;71,72,106 however, MIF has been shown to have no effect on the expression of COX-1.71

The COX-2/PGE2 pathway has been extensively documented as being one of the key mediators driving MSC immunomodulation.39,68,107,108 Our data show that MIF stimulation enhances the expression of COX-2, but not TSG-6 or PTGS2, in untreated and TNF-α-licensed MSCs. We hypothesized that the COX-2/PGE2 pathway could be involved in the restoration of MSCs’ immunomodulatory capacity following CATT7 licensing. To investigate, we pre-treated MSCs with indomethacin prior to licensing. Indomethacin is a potent non-selective inhibitor of COX-1 and COX-2.109 We showed that blocking COX-2 abrogated the therapeutic efficacy of CATT7 licensed MSCs. Interestingly we observed that blocking of COX-2 via indomethacin had a more pronounced effect than blocking CD74. COX-2 is constitutively expressed in human MSCs; therefore, inhibition with indomethacin also blocks basal COX-2 expression, which will contribute to the effects observed.

These data show that MIF licensing can improve MSC therapeutic efficacy through the upregulation of COX-2, which likely drives PGE2 production. Our data agree with several studies in the literature that also reveal the ability of MIF to improve MSC efficacy in vivo.110,111,112 Zhu et al.,110 Liu et al.,111 and Zhang et al.112 demonstrated the ability of MIF to improve MSC therapeutic efficacy by transducing MSCs with a lentiviral vector containing Mif cDNA, thus promoting MIF overexpression.110,111,112 Furthermore, Zhang et al.113 demonstrated the ability of MIF to upregulate COX-2 expression and promote PGE2 production in astrocytes. Here, we further demonstrate the effects of ex vivo MIF licensing on MSC therapeutic efficacy by showing that binding to CD74 and increased COX-2 expression enhances MSCs’ immunomodulatory abilities.

The knowledge gained from this study can be used to further optimize MSCs as a therapy and provide a basis for future studies regarding the effects of MSCs on the immune response in high-MIF environments, such as in asthma patients exhibiting the CATT7 polymorphism.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

All procedures involving the use of animals or human materials were carried out by licensed personnel. Ethics approval for all work was granted by the biological research ethics committee of Maynooth University (BRESC-2018-013). Project authorization was received from the Scientific Animal Protection Unit of the Health Products Regulatory Agency (HPRA) under AE19124/P022, where the terms of the animal experiments within this project were outlined and adhered to in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) criteria.

Human BM-MSC culture

BM-MSCs from three different human donors were obtained from RoosterBio (Frederick, MD, USA). MSCs were first expanded in RoosterBio proprietary expansion medium (RoosterBasal and RoosterBooster) for the first two passages according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following this, MSCs were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) low glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, Arklow, Wicklow, Ireland) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; BioSera, Cholet, France) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Human MSCs were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per T175 flask and cultured at 37 °c in 5% CO2. Medium was replenished every 2–3 days, and cells were passaged when they achieved 80% confluency. All experiments were carried out between passages 2–5.

MSC characterization

BM-MSCs from three different human donors (identified as 001-177, 003-307, and 003-310) from RoosterBio were characterized by analyzing the expression of cell surface markers. All MSCs donors were found to be negative for CD34 (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), CD45 (Allophycocyanin (APC)), and human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR) (phycoerythrin (PE)) and positive for CD73 (APC), CD90 (FITC), and CD105 (PE) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) by the Attune Nxt flow cytometer (Figure S3).

Animal strains

Two C57BL/6 mouse strains expressing the human high- or low-expression MIF alleles (MIFCATT7 [(C57BL/6NTac-Miftm3884.1(MIF)Tac-Tg(CAG-Flpe)2Arte] and MIFCATT5 [C57BL/6NTac-Miftm3883.1(MIF)Tac-Tg(CAG-Flpe)2Arte] mice) were created using vector-based recombinant replacement of murine Mif by Taconic Biosciences (Rensselaer, NY, USA) (Figure 1). Validation of the expression of human and not murine MIF mRNA was verified by qPCR, and −794 CATT-length-dependent stimulated MIF production was confirmed in vivo.61 Littermate WT and MIF−/− (MIF KO)114 (a kind donation from R. Bucala, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) mice were used as controls.

HDM-induced airway inflammation model and therapeutic protocol

Both male and female MIFCATT7, MIFCATT5, or WT mice aged 6–12 weeks were challenged with 25 μg HDM extract (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus; Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, NC, USA) in 25 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) intranasally (i.n.) 3 days weekly for 3 weeks under light isoflurane anesthesia. Control mice were challenged with 25 μL PBS under the same conditions. On day 14, after HDM challenge, mice received an i.v. injection of 1 × 106 MSCs in 300 μL into the tail vein.115 For the dose curve, 1 × 106, 5 × 105, 1 × 105, and 5 × 104 were administered i.v. into HDM-challenged CATT7 mice on day 14. 5 × 104 was selected as the dose at which MSCs lose efficacy.

Licensing of MSCs with endogenous hMIF

Supernatants containing endogenous hMIF were generated from BMDMs of C57BL/6 mouse strains expressing the high-expressing MIF allele (CATT7). CATT7 mice were challenged with HDM in 25 μL PBS i.n. 3 days weekly for 3 weeks under light isoflurane anesthesia. 4 h post final challenge, femora and tibiae were flushed with warm Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium GlutaMAX (Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS (BioSera) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were collected and seeded into T175 flasks in cRPMI supplemented with 10% L929 CM. The L929 cell line produces high amounts of macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and other proteins stimulating macrophage differentiation. After 96 h, supernatants were collected, sterile filtered (0.22 μM pore size), and stored at −20°C. The CM generated in this manner will be referred to as CATT7 CM. Additionally, KO CM was generated from MIF KO mice as a control. Licensing MSCs was performed by removing existing medium, washing with PBS, and incubating cells with CATT7 CM (CATT7MSC) or MIF KO CM (KOMSC) for 24 h. To account for variability of hMIF levels between CATT7 mice and to ensure that WT mice did not produce hMIF, CATT7, CATT5, and WT supernatants were measured by hMIF ELISA (R&D Systems, MN, USA) as described previously (Figure S2).62 5 × 104 licensed MSCs were administered i.v. into HDM-challenged CATT7 mice on day 14. Where indicated, MSCs were treated with the COX-2 inhibitor indomethacin (10 μM) for 30 min. Following pre-treatment, MSCs were licensed with CATT7 CM for 24 h as described above. Moreover, mouse anti-CD74 neutralizing antibody and isotype control were added to the assay. MSCs were pre-treated with anti-CD74 neutralizing antibody (clone LN2; 10 μg/mL) or IgG1 κ isotype control (clone T8E5; 10 μg/mL) for 30 min. MSCs were then licensed with CATT7 CM for 24 h before administration.

Collection of BALF

On day 18, 4 h post final challenge, mice were sacrificed for cell and cytokine analysis of the BALF. BALF was obtained through 3 gentle aspirations of PBS. After centrifugation, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was added to the supernatants before Th2 cytokine analysis. Total numbers of viable BALF cells were counted using ethidium bromide/acridine orange staining on a hemocytometer and then pelleted onto microscope slides by cytocentrifugation. Slides were stained with Kwik Diff kit stain (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), and coverslips were mounted using dibutylphthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX) mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Differential cells counts were derived by counting a minimum of 300 leukocytes on randomly selected fields under a light microscope at 20× magnification.

ELISA

Levels of mouse interleukin-4 (mIL-4) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and mIL-13 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) were determined using commercial ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lung histology

On day 21, mice were sacrificed for histological analysis. Lungs were removed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin embedded, and 5-μm slices were mounted onto slides for histological analysis. Lung tissue was stained with H&E, PAS, or Masson’s trichrome to analyze immune cell infiltration, goblet cell hyperplasia, or subepithelial collagen deposition, respectively. H&E analysis was carried out as described previously.116 Goblet cell hyperplasia was determined by the percentage of PAS-positive cells in airways relative to airway diameter. Subepithelial collagen deposition was calculated by analyzing the percentage of positive staining using the trainable Weka segmentation plugin on Fiji open-source software.

Cryo-imaging

1 × 106 MSCs were labeled with the Qtracker 625 labeling kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions before being administered i.v. on day 14. On day 15, mice were humanely euthanized, and the lungs were embedded in mounting medium for cryotomy (O.C.T. compound, VWR Chemicals, Leuven, Switzerland), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Lungs were sectioned into 40-μm slices and imaged with the automated CryoViz imaging system (BioInvision, Cleveland, OH, USA). Images were then processed to generate 3D images using CryoViz processing, and the number of detected cells was quantified using cell detection software (BioInvision).39

Analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Ambion Life Sciences, Cambridgeshire, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were measured using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and equalized to 100 ng/μL before cDNA synthesis. cDNA synthesis was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quantabio, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was carried out using PerfeCta SYBR Green FastMix (Quantabio). Expression of human COX-2, PTGES, IDO, ICAM-1, HGF, TSG-6, and PTGS2 (primer sequence information is available in Table S1) was quantified in relation to the housekeeper gene HPRT using the ΔCT method. The fold change in the relative gene expression was determined by calculating the 2−ΔΔCT values.

MSC expansion assay

1.4 × 105 MSCs were seeded out into T25 flasks in complete Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (cDMEM) or 50:50 cDMEM and WT CM or CATT7 CM for 72 h. Cells were trypsinized and stained with ethidium bromide/acridine orange and counted on a hemocytometer. The MIF inhibitor SCD-19 (100 μM) was used to determine MIF specificity. In such cases, CM was pre-incubated with SCD-19 1 h before the expansion assay.

Intracellular staining of COX-2 and IDO

MSCs were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. MSCs were stimulated with recombinant human IFNγ at low (5 ng/mL) or high (40 ng/mL) concentration, TNF-α (5–10 ng/mL; PeproTech, London, UK), rhMIF (1 ng/mL; provided by Rick Bucala, Yale), or endogenous MIF (CATT7 CM) for 24 h. Cells were prepared for intracellular staining using the Intracellular FoxP3 kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were stained with COX-2 (PE) or IDO (APC) (BD Pharmingen) for 45 min. Cells were then washed in flow cytometry staining buffer and acquired using the Attune Nxt flow cytometer.

Surface staining of CD74

MSCs were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. MSCs were stimulated with recombinant human IFNγ (5 ng/mL, PeproTech), rhMIF (1, 10, or 100 ng/mL), or endogenous MIF (CATT7 CM) for 24 h. Cells were stained with CD74 (PE, BD Pharmingen) for 45 min. Cells were then washed in flow cytometry staining buffer and acquired using the Attune Nxt flow cytometer.

T cell suppression assay

Human PBMCs were isolated from buffy packs (Irish Blood Transfusion Service) by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. 5 × 104 carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled PBMC were co-cultured (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR, USA) with BM-MSCs at a 1:20 ratio (2.5 × 103 cells/well). 24 h prior to co-culture, BM-MSCs were incubated with CATT7 CM or CATT7 CM + SCD-19 (100 μM). After 24 h, BM-MSCs were washed with PBS before adding the PBMCs. Activation and expansion of human T cells was carried out using ImmunoCult human CD3/CD28 T cell activator antibody mix (STEMCELL Technologies, Cambridge, UK). After 4 days, PBMCs were harvested, and the frequency (percent) and number of proliferating CD3+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Attune Nxt flow cytometer).

Statistical analysis

Mice were randomized. Observers assessing endpoints were blinded to group assignment. Data for individual animals and independent experiments are presented as individual symbols. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Results of two or more groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an Irish Research Council Laureate Award to K.E. (IRCLA/2017/288). This publication has emanated from research supported in part by a research grant from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under grant 12/RI/2346 (2), an infrastructure award supporting the CryoViz and SFI grant 16/RI/3399, and an infrastructure award supporting the Attune Nxt. We would like to thank Deirdre Daly, Gillian O’Meara, and Shannon Grellan for exceptional care of our animals used in this study.

Author contributions

I.J.H. performed research, data analysis, and study design and wrote the manuscript. H.D. performed research, data analysis, and study design and wrote the manuscript. C.T. and T.S. performed research and data analysis. D.J.W., S.R.E., and C.C.d.S. contributed to study design and data analysis. S.C.D. and M.E.A. provided reagents and contributed to study design and data analysis. K.E. designed and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.09.013.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Sverrild A., Hansen S., Hvidtfeldt M., Clausson C.M., Cozzolino O., Cerps S., Uller L., Backer V., Erjefält J., Porsbjerg C. The effect of tezepelumab on airway hyperresponsiveness to mannitol in asthma (UPSTREAM) Eur. Respir. J. 2022;59 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01296-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleecker E.R., FitzGerald J.M., Chanez P., Papi A., Weinstein S.F., Barker P., Sproule S., Gilmartin G., Aurivillius M., Werkström V., et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2016;388:2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corren J., Castro M., O’Riordan T., Hanania N.A., Pavord I.D., Quirce S., Chipps B.E., Wenzel S.E., Thangavelu K., Rice M.S., et al. Dupilumab efficacy in patients with uncontrolled, moderate-to-severe allergic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020;8:516–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortega H.G., Yancey S.W., Mayer B., Gunsoy N.B., Keene O.N., Bleecker E.R., Brightling C.E., Pavord I.D. Severe eosinophilic asthma treated with mepolizumab stratified by baseline eosinophil thresholds: a secondary analysis of the DREAM and MENSA studies. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016;4:549–556. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan R., Lipworth B. Efficacy of biologic therapy on airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Off Publ. Am. Coll. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023:00121–00127. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2023.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin M., Sueblinvong V., Eisenhauer P., Ziats N.P., LeClair L., Poynter M.E., Steele C., Rincon M., Weiss D.J. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit Th2-mediated allergic airways inflammation in mice. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/stem.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abreu S.C., Antunes M.A., de Castro J.C., de Oliveira M.V., Bandeira E., Ornellas D.S., Diaz B.L., Morales M.M., Xisto D.G., Rocco P.R.M. Bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells vs. mesenchymal stromal cells in experimental allergic asthma. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013;187:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi J.Y., Hur J., Jeon S., Jung C.K., Rhee C.K. Effects of human adipose tissue- and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on airway inflammation and remodeling in a murine model of chronic asthma. Sci. Rep. 2022;12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai R., Yu Y., Yan G., Hou X., Ni Y., Shi G. Intratracheal administration of adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviates chronic asthma in a mouse model. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018;18:131. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0701-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Castro L.L., Xisto D.G., Kitoko J.Z., Cruz F.F., Olsen P.C., Redondo P.A.G., Ferreira T.P.T., Weiss D.J., Martins M.A., Morales M.M., Rocco P.R.M. Human adipose tissue mesenchymal stromal cells and their extracellular vesicles act differentially on lung mechanics and inflammation in experimental allergic asthma. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017;8:151. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hur J., Kang J.Y., Kim Y.K., Lee S.Y., Jeon S., Kim Y., Jung C.K., Rhee C.K. Evaluation of human MSCs treatment frequency on airway inflammation in a mouse model of acute asthma. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020;35:e188. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathias L.J., Khong S.M.L., Spyroglou L., Payne N.L., Siatskas C., Thorburn A.N., Boyd R.L., Heng T.S.P. Alveolar macrophages are critical for the inhibition of allergic asthma by mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Immunol. 1950. 2013;191:5914–5924. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou-Yang H.F., Huang Y., Hu X.B., Wu C.G. Suppression of allergic airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma by exogenous mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2011;236:1461–1467. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royce S.G., Mao W., Lim R., Kelly K., Samuel C.S. iPSC- and mesenchymoangioblast-derived mesenchymal stem cells provide greater protection against experimental chronic allergic airways disease compared with a clinically used corticosteroid. FASEB J. Off Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2019;33:6402–6411. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802307R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royce S.G., Rele S., Broughton B.R.S., Kelly K., Samuel C.S. Intranasal administration of mesenchymoangioblast-derived mesenchymal stem cells abrogates airway fibrosis and airway hyperresponsiveness associated with chronic allergic airways disease. FASEB J. 2017;31:4168–4178. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700178R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song X., Xie S., Lu K., Wang C. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental asthma by inducing polarization of alveolar macrophages. Inflammation. 2015;38:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9954-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong H., Fan X.L., Fang S.B., Lin Y.D., Wen W., Fu Q.L. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent chronic allergic airway inflammation via TGF-β1-Smad2/Smad3 signaling pathway in mice. Mol. Immunol. 2019;109:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abreu S.C., Xisto D.G., de Oliveira T.B., Blanco N.G., de Castro L.L., Kitoko J.Z., Olsen P.C., Lopes-Pacheco M., Morales M.M., Weiss D.J., Rocco P.R.M. Serum from asthmatic mice potentiates the therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stromal cells in experimental allergic asthma. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019;8:301–312. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abreu S.C., Lopes-Pacheco M., da Silva A.L., Xisto D.G., de Oliveira T.B., Kitoko J.Z., de Castro L.L., Amorim N.R., Martins V., Silva L.H.A., et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid enhances the effects of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in experimental allergic asthma. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1147. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braza F., Dirou S., Forest V., Sauzeau V., Hassoun D., Chesné J., Cheminant-Muller M.A., Sagan C., Magnan A., Lemarchand P. Mesenchymal stem cells induce suppressive macrophages through phagocytosis in a mouse model of asthma. STEM CELLS. 2016;34:1836–1845. doi: 10.1002/stem.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro L.L., Kitoko J.Z., Xisto D.G., Olsen P.C., Guedes H.L.M., Morales M.M., Lopes-Pacheco M., Cruz F.F., Rocco P.R.M. Multiple doses of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells induce immunosuppression in experimental asthma. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2020;9:250–260. doi: 10.1002/sctm.19-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duong K.M., Arikkatt J., Ullah M.A., Lynch J.P., Zhang V., Atkinson K., Sly P.D., Phipps S. Immunomodulation of airway epithelium cell activation by mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorates house dust mite-induced airway inflammation in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015;53:615–624. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0431OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitoko J.Z., de Castro L.L., Nascimento A.P., Abreu S.C., Cruz F.F., Arantes A.C., Xisto D.G., Martins M.A., Morales M.M., Rocco P.R.M., Olsen P.C. Therapeutic administration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells reduces airway inflammation without up-regulating Tregs in experimental asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2018;48:205–216. doi: 10.1111/cea.13048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin J.W., Ryu S., Ham J., Jung K., Lee S., Chung D.H., Kang H.R., Kim H.Y. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress severe asthma by directly regulating Th2 cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Mol. Cells. 2021;44:580–590. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2021.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruz F.F., Borg Z.D., Goodwin M., Sokocevic D., Wagner D.E., Coffey A., Antunes M., Robinson K.L., Mitsialis S.A., Kourembanas S., et al. Systemic administration of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell extracellular vesicles ameliorates aspergillus hyphal extract-induced allergic airway inflammation in immunocompetent mice. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015;4:1302–1316. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lathrop M.J., Brooks E.M., Bonenfant N.R., Sokocevic D., Borg Z.D., Goodwin M., Loi R., Cruz F., Dunaway C.W., Steele C., Weiss D.J. Mesenchymal stromal cells mediate Aspergillus hyphal extract-induced allergic airway inflammation by inhibition of the Th17 signaling pathway. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014;3:194–205. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abreu S.C., Antunes M.A., Xisto D.G., Cruz F.F., Branco V.C., Bandeira E., Zola Kitoko J., de Araújo A.F., Dellatorre-Texeira L., Olsen P.C., et al. Bone marrow, adipose, and lung tissue-derived murine mesenchymal stromal cells release different mediators and differentially affect airway and lung parenchyma in experimental asthma. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017;6:1557–1567. doi: 10.1002/sctm.16-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mariñas-Pardo L., Mirones I., Amor-Carro Ó., Fraga-Iriso R., Lema-Costa B., Cubillo I., Rodríguez Milla M.Á., García-Castro J., Ramos-Barbón D. Mesenchymal stem cells regulate airway contractile tissue remodeling in murine experimental asthma. Allergy. 2014;69:730–740. doi: 10.1111/all.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunbar H., Weiss D.J., Rolandsson Enes S., Laffey J.G., English K. The inflammatory lung microenvironment; a key mediator in MSC licensing. Cells. 2021;10:2982. doi: 10.3390/cells10112982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J., Gao J., Liang Z., Gao C., Niu Q., Wu F., Zhang L. Mesenchymal stem cells and their microenvironment. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022;13:429. doi: 10.1186/s13287-022-02985-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudres M., Norol F., Trenado A., Grégoire S., Charlotte F., Levacher B., Lataillade J.J., Bourin P., Holy X., Vernant J.P., et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro but fail to prevent graft-versus-host disease in mice. J. Immunol. 1950. 2006;176:7761–7767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorronsoro A., Ferrin I., Salcedo J.M., Jakobsson E., Fernández-Rueda J., Lang V., Sepulveda P., Fechter K., Pennington D., Trigueros C. Human mesenchymal stromal cells modulate T-cell responses through TNF-α-mediated activation of NF-κB. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:480–488. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobin L.M., Healy M.E., English K., Mahon B.P. Human mesenchymal stem cells suppress donor CD4(+) T cell proliferation and reduce pathology in a humanized mouse model of acute graft-versus-host disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013;172:333–348. doi: 10.1111/cei.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss D.J., English K., Krasnodembskaya A., Isaza-Correa J.M., Hawthorne I.J., Mahon B.P. The necrobiology of mesenchymal stromal cells affects therapeutic efficacy. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1228. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Islam D., Huang Y., Fanelli V., Delsedime L., Wu S., Khang J., Han B., Grassi A., Li M., Xu Y., et al. Identification and modulation of microenvironment is crucial for effective mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;199:1214–1224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0356OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ankrum J.A., Ong J.F., Karp J.M. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:252–260. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathew S.A., Chandravanshi B., Bhonde R. Hypoxia primed placental mesenchymal stem cells for wound healing. Life Sci. 2017;182:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roemeling-van Rhijn M., Mensah F.K.F., Korevaar S.S., Leijs M.J., van Osch G.J.V.M., Ijzermans J.N.M., Betjes M.G.H., Baan C.C., Weimar W., Hoogduijn M.J. Effects of hypoxia on the immunomodulatory properties of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:203. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carty F., Dunbar H., Hawthorne I.J., Ting A.E., Stubblefield S.R., Van’t Hof W., English K. IFN-γ and PPARδ influence the efficacy and retention of multipotent adult progenitor cells in graft vs host disease. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021;10:1561–1574. doi: 10.1002/sctm.21-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbett J.M., Hawthorne I., Dunbar H., Coulter I., Chonghaile M.N., Flynn C.M., English K. Cyclosporine A and IFNγ licencing enhances human mesenchymal stromal cell potency in a humanised mouse model of acute graft versus host disease. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12:238. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva J.D., Lopes-Pacheco M., de Castro L.L., Kitoko J.Z., Trivelin S.A., Amorim N.R., Capelozzi V.L., Morales M.M., Gutfilen B., de Souza S.A.L., et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid potentiates the therapeutic effects of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells on lung and distal organ injury in experimental sepsis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019;10:264. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1365-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bustos M.L., Huleihel L., Meyer E.M., Donnenberg A.D., Donnenberg V.S., Sciurba J.D., Mroz L., McVerry B.J., Ellis B.M., Kaminski N., Rojas M. Activation of human mesenchymal stem cells impacts their therapeutic abilities in lung injury by increasing interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-1RN levels. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2013;2:884–895. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rolandsson Enes S., Hampton T.H., Barua J., McKenna D.H., Dos Santos C.C., Amiel E., Ashare A., Liu K.D., Krasnodembskaya A.D., English K., et al. Healthy versus inflamed lung environments differentially affect mesenchymal stromal cells. Eur. Respir. J. 2021;58 doi: 10.1183/13993003.04149-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abreu S.C., Hampton T.H., Hoffman E., Dearborn J., Ashare A., Singh Sidhu K., Matthews D.E., McKenna D.H., Amiel E., Barua J., et al. Differential effects of the cystic fibrosis lung inflammatory environment on mesenchymal stromal cells. Am. J. Physiol-lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00218.2020. ajplung.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bacher M., Metz C.N., Calandra T., Mayer K., Chesney J., Lohoff M., Gemsa D., Donnelly T., Bucala R. An essential regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in T-cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7849–7854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calandra T., Bernhagen J., Metz C.N., Spiegel L.A., Bacher M., Donnelly T., Cerami A., Bucala R. MIF as a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature. 1995;377:68–71. doi: 10.1038/377068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calandra T., Bernhagen J., Mitchell R.A., Bucala R. The macrophage is an important and previously unrecognized source of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1895–1902. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donnelly S.C., Haslett C., Reid P.T., Grant I.S., Wallace W.A., Metz C.N., Bruce L.J., Bucala R. Regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat. Med. 1997;3:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Das R., Moss J.E., Robinson E., Roberts S., Levy R., Mizue Y., Leng L., McDonald C., Tigelaar R.E., Herrick C.A., Bucala R. Role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the Th2 immune response to epicutaneous sensitization. J. Clin. Immunol. 2011;31:666–680. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9541-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li R., Wang F., Wei J., Lin Y., Tang G., Rao L., Ma L., Xu Q., Wu J., Lv Q., et al. The role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in asthmatic airway remodeling. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2021;13:88–105. doi: 10.4168/aair.2021.13.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magalhães E.S., Mourao-Sa D.S., Vieira-de-Abreu A., Figueiredo R.T., Pires A.L., Farias-Filho F.A., Fonseca B.P.F., Viola J.P.B., Metz C., Martins M.A., et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is essential for allergic asthma but not for Th2 differentiation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:1097–1106. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizue Y., Ghani S., Leng L., McDonald C., Kong P., Baugh J., Lane S.J., Craft J., Nishihira J., Donnelly S.C., et al. Role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:14410–14415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507189102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allam V.S.R.R., Pavlidis S., Liu G., Kermani N.Z., Simpson J., To J., Donnelly S., Guo Y.K., Hansbro P.M., Phipps S., et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes glucocorticoid resistance of neutrophilic inflammation in a murine model of severe asthma. Thorax. 2022;78:661–673. doi: 10.1136/thorax-2021-218555. thoraxjnl-2021-218555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amano T., Nishihira J., Miki I. Blockade of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) prevents the antigen-induced response in a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2007;56:24–31. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-5184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobayashi M., Nasuhara Y., Kamachi A., Tanino Y., Betsuyaku T., Yamaguchi E., Nishihira J., Nishimura M. Role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in rats. Eur. Respir. J. 2006;27:726–734. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00107004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen P.F., Luo Y.l., Wang W., Wang J.x., Lai W.y., Hu S.m., Cheng K.F., Al-Abed Y. ISO-1, a macrophage migration inhibitory factor antagonist, inhibits airway remodeling in a murine model of chronic asthma. Mol. Med. 2010;16:400–408. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Awandare G.A., Martinson J.J., Were T., Ouma C., Davenport G.C., Ong’echa J.M., Wang W., Leng L., Ferrell R.E., Bucala R., Perkins D.J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) promoter polymorphisms and susceptibility to severe malarial anemia. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200:629–637. doi: 10.1086/600894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Savva A., Brouwer M.C., Roger T., Valls Serón M., Le Roy D., Ferwerda B., van der Ende A., Bochud P.Y., van de Beek D., Calandra T. Functional polymorphisms of macrophage migration inhibitory factor as predictors of morbidity and mortality of pneumococcal meningitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016;113:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520727113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benedek G., Meza-Romero R., Jordan K., Zhang Y., Nguyen H., Kent G., Li J., Siu E., Frazer J., Piecychna M., et al. MIF and D-DT are potential disease severity modifiers in male MS subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E8421–E8429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712288114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu A., Bao F., Voravuthikunchai S.P. CATT polymorphism in MIF gene promoter is closely related to human pulmonary tuberculosis in a southwestern China population. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2018;32 doi: 10.1177/2058738418777108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shin J.J., Fan W., Par-Young J., Piecychna M., Leng L., Israni-Winger K., Qing H., Gu J., Zhao H., Schulz W.L., et al. MIF is a common genetic determinant of COVID-19 symptomatic infection and severity. QJM Mon J. Assoc. Physicians. 2022:hcac234. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcac234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dunbar H., Hawthorne I.J., Tunstead C., Armstrong M.E., Donnelly S.C., English K. Blockade of MIF biological activity ameliorates house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation in humanised MIF mice. FASEB J. 2023;37:e23072. doi: 10.1096/fj.202300787R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lourenco S., Teixeira V.H., Kalber T., Jose R.J., Floto R.A., Janes S.M. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor - CXCR4 is the dominant chemotactic axis in human mesenchymal stem cell recruitment to tumors. J. Immunol. 1950. 2015;194:3463–3474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.English K. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2013;91:19–26. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chinnadurai R., Rajan D., Ng S., McCullough K., Arafat D., Waller E.K., Anderson L.J., Gibson G., Galipeau J. Immune dysfunctionality of replicative senescent mesenchymal stromal cells is corrected by IFNγ priming. Blood Adv. 2017;1:628–643. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017006205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chinnadurai R., Copland I.B., Garcia M.A., Petersen C.T., Lewis C.N., Waller E.K., Kirk A.D., Galipeau J. Cryopreserved mesenchymal stromal cells are susceptible to T-cell mediated apoptosis which is partly rescued by IFNγ licensing. Stem Cells. 2016;34:2429–2442. doi: 10.1002/stem.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chinnadurai R., Bates P.D., Kunugi K.A., Nickel K.P., DeWerd L.A., Capitini C.M., Galipeau J., Kimple R.J. Dichotomic potency of IFNγ licensed allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in animal models of acute radiation syndrome and graft versus host disease. Front. Immunol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.708950. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.708950 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.English K., Barry F.P., Field-Corbett C.P., Mahon B.P. IFN-γ and TNF-α differentially regulate immunomodulation by murine mesenchymal stem cells. Immunol. Lett. 2007;110:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murphy N., Treacy O., Lynch K., Morcos M., Lohan P., Howard L., Fahy G., Griffin M.D., Ryan A.E., Ritter T. TNF-α/IL-1β-licensed mesenchymal stromal cells promote corneal allograft survival via myeloid cell-mediated induction of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the lung. FASEB J. Off Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2019;33:9404–9421. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900047R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gomes A.O., Barbosa B.F., Franco P.S., Ribeiro M., Silva R.J., Gois P.S.G., Almeida K.C., Angeloni M.B., Castro A.S., Guirelli P.M., et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) prevents maternal death, but contributes to poor fetal outcome during congenital toxoplasmosis. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:906. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carli C., Metz C.N., Al-Abed Y., Naccache P.H., Akoum A. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 production in human endometriotic cells by macrophage migration inhibitory factor: involvement of novel kinase signaling pathways. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3128–3137. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitchell R.A., Liao H., Chesney J., Fingerle-Rowson G., Baugh J., David J., Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) sustains macrophage proinflammatory function by inhibiting p53: regulatory role in the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:345–350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012511599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li D., Han Y., Zhuang Y., Fu J., Liu H., Shi Q., Ju X. Overexpression of COX-2 but not indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 enhances the immunosuppressive ability of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015;35:1309–1316. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guan Q., Ezzati P., Spicer V., Krokhin O., Wall D., Wilkins J.A. Interferon γ induced compositional changes in human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Clin. Proteomics. 2017;14:26. doi: 10.1186/s12014-017-9161-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lan H., Wang N., Chen Y., Wang X., Gong Y., Qi X., Luo Y., Yao F. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) promotes rat airway muscle cell proliferation and migration mediated by ERK1/2 and FAK signaling. Cell Biol. Int. 2018;42:75–83. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ohta S., Misawa A., Fukaya R., Inoue S., Kanemura Y., Okano H., Kawakami Y., Toda M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) promotes cell survival and proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 13):3210–3220. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Utispan K., Koontongkaew S. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor modulates proliferation, cell cycle, and apoptotic activity in head and neck cancer cell lines. J. Dent. Sci. 2021;16:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kulesza A., Paczek L., Burdzinska A. The Role of COX-2 and PGE2 in the Regulation of Immunomodulation and Other Functions of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomedicines. 2023;11:445. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11020445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin Y.D., Fan X.L., Zhang H., Fang S.B., Li C.L., Deng M.X., Qin Z.L., Peng Y.Q., Zhang H.Y., Fu Q.L. The genes involved in asthma with the treatment of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol. Immunol. 2018;95:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fallon P.G., Schwartz C. The high and lows of type 2 asthma and mouse models. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;145:496–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hass R., Kasper C., Böhm S., Jacobs R. Different populations and sources of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): A comparison of adult and neonatal tissue-derived MSC. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carty F., Corbett J.M., Cunha J.P.M.C.M., Reading J.L., Tree T.I.M., Ting A.E., Stubblefield S.R., English K. Multipotent adult progenitor cells suppress T Cell activation in in vivo models of homeostatic proliferation in a prostaglandin E2-dependent manner. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:645. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Witte S.F.H., Merino A.M., Franquesa M., Strini T., van Zoggel J.A.A., Korevaar S.S., Luk F., Gargesha M., O’Flynn L., Roy D., et al. Cytokine treatment optimises the immunotherapeutic effects of umbilical cord-derived MSC for treatment of inflammatory liver disease. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017;8:140. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0590-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baugh J.A., Chitnis S., Donnelly S.C., Monteiro J., Lin X., Plant B.J., Wolfe F., Gregersen P.K., Bucala R. A functional promoter polymorphism in the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene associated with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Genes Immun. 2002;3:170–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]