Highlights

-

•

Ultrasound-assisted extraction could be a good method for extracting larvae proteins.

-

•

Ultrasound-assisted extraction could improve properties of larvae proteins.

-

•

The findings could promote the wider application of larvae proteins in food industry.

Keywords: Ultrasound-assisted extraction, Insect protein, Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens), Nutritional value, Structure, Functional properties

Abstract

In this study, we developed an ultrasound-assisted alkaline method for extracting black soldier fly larvae protein (BSFLP). The effects of ultrasound-assisted extraction on the nutritional value, structural characteristics, and techno-functional properties of BSFLP were compared with those using the conventional hot alkali method. The results showed that ultrasound-assisted extraction significantly increased the extraction ratio of BSFLP from 55.40% to 80.37%, but reduced the purity from 84.19% to 80.75%. The BSFLP extracted by ultrasound-assisted extraction met the amino acid requirements for humans proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization in 2013, and ultrasound-assisted extraction did not alter the limiting amino acids of the BSFLP. The ultrasound-assisted extraction increased the in vitro protein digestibility from 82.97% to 99.79%. Moreover, ultrasound-assisted extraction obtained BSFLP with a more ordered secondary structure and more loosely porous surface morphology, without breaking the peptide bonds. By contrast, the conventional hot alkaline method hydrolyzed BSFLP into smaller fragments. The effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction on the structure of BSFLP improved the solubility and emulsion capacity of BSFLP, but reduced its foaming properties. In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction could be a suitable method for extracting BSFLP and improving its nutritional value, and structural and functional properties. The findings obtained in this study could promote the wider application of BSFLP in food industry.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that the world's population will increase to 8.8–9.1 billion by 2050 [1]. This population explosion will greatly increase the demand for food, especially protein-based food. However, the depletion of natural resources and increased greenhouse gas emissions are constraining current agricultural production systems [2]. Consequently, the human demand for protein food will not be met by the limited agricultural land that is available [3]. Thus, there is an urgent need to search for new food sources with high protein contents.

Edible insects are used as daily food sources by people in some parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas [4]. Insect proteins are sustainable alternatives to traditional edible proteins because of their high protein contents (35–65 %), low greenhouse gas emissions, high feed conversion ratio, low water consumption, and cheap feed sources [4], [5]. Among these edible insects, the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens, Diptera: Stratiomyidae) is one of the most promising for use in commercial protein production [6]. The black soldier fly is mainly distributed in tropical and warm temperate regions [7], and it has a wide range of dietary sources and can even utilize various agricultural processing by-products [8]. In addition, the essential amino acid composition of black soldier fly larvae (BSFL1) protein meets the World Health Organization (WHO) requirements, with a similar composition to egg white and soy protein [9], [10], [11], [12]. It has been reported that muscle protein is the most abundant protein in BSFL [13].

Cultural barriers to eating insects are still widespread throughout the world, and consumers do not want to see whole insects or insect fragments in their food, so converting insects into powder could increase their acceptance by consumers [14], [15], [16]. Moreover, processing insects into powder could address microbial safety issues by killing microorganisms during drying, extraction, and other operations [17], [18]. Thus, a future direction for the edible insect industry will be supplying the market with enormous quantities of insect-derived proteins and other products.

The methods used to extract protein from insects can affect the protein yield and its functional and structural properties [11], [19], [20], thereby influencing its application in food industries. According to previous studies, the methods used for extracting black soldier fly protein mainly comprise alkaline extraction, enzyme extraction, buffer solution extraction, and the Osborne fractionation protocol [9]. Among these methods, the alkaline extraction method is considered efficient, simple, and inexpensive, and it has high adaptability at the industrial scale [4], [9]. In addition, ultrasound-assisted extraction is an environmentally friendly method that is suitable for the large-scale production of protein [21], [22]. Ultrasound causes microbubble explosions (cavitation effect), which lead to tissue rupture, thereby enhancing mass transfer and improving the extraction efficiency [23]. The combination of ultrasonic assistance and alkaline extraction is expected to achieve extremely high extraction efficiency. Previous studies indicate that ultrasound-assisted extraction can improve the protein extraction rate and also affect the properties of the protein. For example, Li et al. [24] used ultrasound-assisted basic electrolyzed water to extract krill protein, where this method reduced the consumption of NaOH and improved the extraction rate, and also enhanced the solubility, foam capacity, foam stability and emulsifying capacity of krill protein. Zhang et al. [25] found that the solubility, water and oil holding capacity, emulsification activity, and emulsification stability were greater for Tenebrio molitor larvae protein extracted with an ultrasound-assisted alkali method than protein extracted using the conventional hot alkaline method. In addition, Zhang et al. [26] showed that Tenebrio molitor larvae protein obtained using an ultrasound-assisted extraction method (30 min) was characterized by higher in vitro digestibility than protein samples obtained without ultrasonication. To the best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted on the effects of ultrasound-assisted extraction techniques on the physio-chemical properties of BSFL protein.

In this study, ultrasound-assisted extraction was applied to the alkaline extraction of BSFL protein (BSFLP2). The effects of ultrasound-assisted extraction on the main nutrients, molecular weight distribution, in vitro digestibility, amino acid composition, technical function, and structure of BSFLP were investigated. The differences were compared between the black soldier fly protein extracted using the ultrasound-assisted extraction method and with the conventional hot alkaline method. The aim of this study was to develop a better method for extracting BSFLP and promoting its wider application in the food industry.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Black soldier fly eggs were kindly provided by Bioforte Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Shenzhen, China). Wheat bran, corn flour, and alfalfa grass flour were purchased from Guyuan Baofa Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Co. Ltd (Ningxia, China). P0010S BCA Protein Assay Kits were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Omni-EasyTM Protein Sample Loading Buffer, Super-PAGETM Bis-Tris Gels (12 %), Multicolor Prestained Protein Ladder (10–250 kDa) and Coomassie Blue Fast Stain were all purchased from EpiZyme (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals and solvents were analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, USA).

2.2. Preparation of defatted black soldier fly powder

BSFL were reared on feed with a water content of 70 % (wheat bran:corn meal:alfalfa grass meal = 5:2:3) until they were 21 days old. The larvae were separated and soaked in water for 5 h daily to empty their intestines for 3 days. Boiling water was used to kill the larvae and avoid browning [10]. Larvae were oven dried at 45 °C and powdered by using a pulverizer (FW100, Taisite Instruments Co. Ltd, Tianjin, China). Lipids were extracted from dried BSFL powder with petroleum ether (60–90 °C boiling point fraction) [9]. The defatted BSFL (DF-BSFL) powder was passed through a 20-mesh sieve and stored in a refrigerator at –80 °C until use.

2.3. Protein extraction

Three methods were used to extract protein from BSFL comprising ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction, non-ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction (as a control), and conventional hot alkaline extraction.

In preliminary experiments, we optimized the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method with the extraction rate as the response value by response surface methodology. The optimized operating procedure was conducted as follows. First, DF-BSFL powder was mixed with 2.5 g/100 mL NaOH solution at a ratio of 1 g: 56 mL, before placing in a ultrasonic cell crusher (JY92-IIN, Xinzhi Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Ningbo, China), where the instrument power was 4.57 W/cm3. After extraction for 1 h in pulse mode (with a cycle of 3 s on and 5 s off), the BSFLP extracted by using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method was denoted as P-UL.3

All of the experimental steps in the non-ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method were consistent with those in the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method but the ultrasound power was 0 W. The protein extracted using this method was denoted as P-U04 in this study.

The hot alkaline extraction method was conducted as described by Xu et al. [27]. The parameters of this method were also obtained after optimizing the extraction ratio by response surface methodology. Hot alkaline extraction was conducted with a NaOH concentration of 2.44 g/100 mL, material-liquid ratio of 1 g: 22 mL, and extraction temperature of 53 °C under stirring at 100 rpm for 2 h. The BSFLP extracted by using the hot alkaline extraction method was denoted as P-NA5 in this study.

2.4. Determination of extraction ratios

After completing the extraction processes, the extracts were centrifuged for 10 min at 5500 rpm and 4 °C using a bench-top freezing centrifuge (3-30KS, SIGMA, St Louis, USA). Next, 1 mL of the supernatant was made up to a volume of 50 mL with deionized water. The protein content in the solution was determined by using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. The absorbance at 562 nm was measured by using a multifunctional enzyme marker (Spark 10 M, TECAN, Mannedorf, Switzerland), and the protein concentration was converted based on the standard curve. The extraction ratio was calculated as follows:

where γ is the extraction rate, Ce is the protein concentration in the extract (mg/mL), V is the volume of the extract (mL), and mb is the amount of protein in the DF-BSFL powder (mg).

2.5. Preparation of BSFLP

The extracts were centrifuged for 10 min at 8000 rpm and 4 °C, before carefully aspirating the supernatant, centrifuging again for 5 min at 8000 rpm and 4 °C, and then collecting the supernatant. The protein was precipitated at pH 4.0 and centrifuged for 5 min at 4000 rpm to remove the supernatant and retain the precipitated protein. The precipitate was resuspended with an appropriate amount of deionized water and adjusted to neutral pH with 1 mol/L NaOH solution to obtain a salt solution containing BSFLP. The BSFLP salt solution was transferred to a pretreated dialysis bag with a cut-off molecular weight of 7000 Da and dialyzed in a refrigerator at 4 °C. The solution was changed every 12 h with a total of six times. After completing the dialysis process, the solution was frozen at –80 °C. The frozen BSFLP solution was dried by evaporation in a freeze dryer machine (SCIENTZ-10 N, Xinzhi Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Ningbo, China) at a vacuum degree of 30 Pa under continuous decompression for 48 h to finally obtain the dried BSFLP.

2.6. Approximate composition

The moisture, crude protein, crude fat, total sugar and ash contents were determined for crude protein samples DF-BSFL, P-UL, P-U0, and P-NA. The moisture content was determined using Chinese Standard method GB5009.3-2016, the ash content using GB5009.4-2016, the crude protein content using GB5009.5-2016, the crude fat content using GB5009.6-2016, and the total sugar content using GB/T 9695.31-2008.

2.7. Amino acid analysis

Hydrolyzed amino acids in the samples were measured using PITC pre-column derivatization and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography after hydrolysis of proteins with 6 mol/L HCl with reference to Zozo et al. [28]. Due to the destruction of tryptophan under acid hydrolysis conditions, the tryptophan content was determined after hydrolysis with 4 mol/L LiOH using Chinese standard method GB/T 15400-2018. The amino acid content of each sample was converted into the amino acid content of the crude protein before calculating the amino acid score (AAS) for the sample. AASs were calculated for the samples using the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) method from 2013 [29] and the recommended amino acid scoring patterns for adults with the following scoring formula.

2.8. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed to determine the molecular weight distribution of BSFLP. The concentration of each sample was 5 μg/μL and the quantity of the sample loaded was 20 μL. The protein samples were treated with loading buffer and added to the wells. Electrophoresis was then conducted at 100 V for 40 min. Gels were photographed using an imaging system (ChemiDocTM, Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) and the protein bands were analyzed with Image Lab 4.0.

2.9. Circular dichroism spectroscopy

A solution of each sample was prepared at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL with 10 mM phosphate buffer solution at pH = 7.0 and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min, before carefully loading the supernatant into a cuvette with a light path of 0.5 mm. The circular dichroism spectrum of the sample at 180–260 nm was measured by using a ChirascanTM V100 system (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK) with 10 mM phosphate buffer solution at pH = 7.0 as the background. The scan rate was 50 nm per min. The spectral data were analyzed by using CDNN 2.1.

2.10. Scanning electron microscopy

The surface morphology of each sample was observed using a bench-top scanning electron microscope (EM-30 Plus, Coxem, Daejeon, Korea) at magnifications of 200 × and 1000×. The protein powder was glued to the sample stage with conductive adhesive and the unfixed powder was blown off with an earwash ball. The samples were observed after sputter coating with gold for 1 min.

2.11. In vitro protein digestibility

The in vitro protein digestibility was determined by simulating multi-enzyme two-stage (gastric and intestinal) digestion using the method described by Zielińska Dawidziak et al. [30] and Brodkorb et al. [31]. First, 0.1 g of sample was added to 5 mL of deionized water containing pepsin (10000 U; Sigma, St Louis, USA) and the pH of the mixture was adjusted to 2.0 with 1 M HCl. Digestion was conducted at 37 °C for 2 h, before adding 5 mL of 0.1 M NaHCO3 solution containing pancreatic intestinal extract (0.005 g; Sigma, St Louis, USA) and bile salts (0.03 g; Sigma, St Louis, USA). After adjusting the pH to 7.0, digestion was continued at 37 °C for 2 h. The remaining protein present in the supernatant was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid. The digested sample was centrifuged and the protein nitrogen of the supernatant was determined using a KjeltecTM 8100 Kjeldahl apparatus (FOSS, Hilleroed, Denmark). The in vitro protein digestibility was calculated as follows:

where Cu is the nitrogen content of the supernatant (g) and Cp is the nitrogen content of 0.1 g of sample (g).

2.12. Techno-functional properties

The water and oil binding capacities, solubility (WBC, OBC), foaming capacity (FC), foam stability (FS), emulsification capacity (EC), and emulsification stability (ES) were determined according to the methods described by Mshayisa et al. [11].

The 0.5 g protein samples were vortexed with 2.5 mL of deionized water or sunflower oil for 1 min and centrifuged at 3330 × g for 2 min. Then, the samples were inverted for 1 h to drain unabsorbed fluid and then weighed to calculate WBC and OBC.

where Wi is the initial dry weight (g) of the sample and Wf is the final weight (g) of the sample.

The solvents for the following functional characterization experiments were all 0.01 mol/L phosphate buffer solutions at pH = 7.0.

The solubility test procedure is as follows. The protein sample (400 mg) was dispersed in 20 mL of the buffer. The samples were shaken for 30 min and centrifuged at 7500 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The total amount of protein in the sample supernatant was determined using the BCA method (Section 1.4).

Both foaming and emulsifying properties were determined by dissolving the protein samples in a buffer solution (5 % w/v), centrifuging at 9000 × g, and using the supernatant. Foaming properties were determined by foaming the protein solution in a homogenizer at 16,000 rpm. The volume was read with a measuring cylinder at 0 and 30 min after homogenization.

where V is the volume (mL) before homogenization, Vf is the volume (mL) after homogenization, and V30 is the volume (mL) after 30 min of settling.

The supernatant was mixed with sunflower oil (1:1 v/v) and homogenized at 18,000 rpm for 1 min. Emulsion samples were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min, and the volume of each layer was read using a measuring cylinder to measure EC. The emulsion was heated in a water bath (80 °C for 30 min) to determine ES.

where Vt is the total volume (mL) of the sample after homogenization, Ve is the volume (mL) of the emulsion layer, and V30 is the volume (mL) of the emulsion layer after heating.

2.13. Statistical analysis

All tests were conducted in triplicate and the results were expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Tukey's test was used to conduct multiple comparisons, where p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Extraction ratios and approximate compositions

Table 1 shows the extraction parameters and corresponding extraction ratios for the three extraction methods. The results showed that ultrasonic-assisted alkali extraction (4.57 W/cm3, 1 h) of BSFL obtained an extraction ratio of 80.37 %. Zhang et al. [25] extracted Tenebrio molitor larvae protein via ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction methods and showed that ultrasound-assisted treatment for 30 min (4 W/cm3) obtained the maximum protein yield of 60.04 %. In the present study, compared with the control group, ultrasound-assisted extraction significantly increased the BSFLP extraction ratio by 31.07 %. Similarly, a previous study showed that ultrasound-assisted extraction improved the insect protein extraction ratio [25]. Compared with the conventional hot alkaline method, the extraction ratio increased significantly by 23.24 % under ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction, and the latter method also shortened the extraction time by half without heating and stirring, and thus it could greatly reduce the energy consumed during the extraction process.

Table 1.

Effects of different extraction methods on protein extraction ratio of BSFL.

| Extraction method | Ultrasonic power (W/cm3) | NaOH concentration (g/100 mL) | Extraction time (h) | Solid-to-solvent ratio | Extraction temperature (℃) | Stir speed (rpm) | Extraction ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U0 | 0 | 2.45 | 1.0 | 1:56 | 25 | 0 | 55.40 ± 1.50c |

| UL | 4.56 | 2.45 | 1.0 | 1:56 | 25 | 0 | 80.37 ± 1.45a |

| NA | 0 | 2.44 | 2.0 | 1:22 | 53 | 100 | 61.69 ± 0.66b |

U0 indicates ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction without ultrasound, UL indicates ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction, and NA indicates hot alkaline extraction. Extraction ratios are given as means ± SD from triplicate determinations. Different letters (a–c) in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). And the extraction parameters of NA referred to the description by Xu et al. [27].

The approximate compositions of the DF-BSFL powder and proteins obtained from P-U0, P-UL, and P-NA are shown in Table 2. The crude protein concentrations were significantly higher in P-U0, P-UL, and P-NA than the DF-BSFL powder. Compared with P-U0 (84.19 %) and P-NA (84.55 %), ultrasound-assisted extraction reduced the purity of P-UL (80.75 %), but this treatment had no effects on the moisture, crude fat, total sugar, and ash contents of P-UL. Insects' exoskeletons contain large amounts of chitin. The decrease in protein purity may be due to the ultrasonic treatment which made the chitin more easily dispersed or dissolved in the extract. It is difficult to separate them in subsequent centrifugation steps. As stated by Ngasotter et al. [32], ultrasonic treatment could break the hydrogen bonds between chitin fibers, resulting in the formation of chitin nanoparticles and enhanced solubility.

Table 2.

Approximate compositions of different samples.

| Samples | Moisture (%) | Crude protein (% DM) |

Crude fat (% DM) | Total Sugars (% DM) |

Ash (% DM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF-BSFL | 9.67 ± 0.35a | 58.76 ± 0.35c | 2.82 ± 0.14a | 21.20 ± 0.44a | 14.89 ± 0.33a |

| P-U0 | 6.85 ± 0.08b | 84.19 ± 1.27a | 0.69 ± 0.10b | 3.72 ± 0.35c | 0.81 ± 0.10b |

| P-UL | 7.03 ± 0.18b | 80.75 ± 0.89b | 0.86 ± 0.08b | 3.41 ± 0.30c | 0.78 ± 0.12b |

| P-NA | 7.13 ± 0.17b | 84.55 ± 1.29a | 0.72 ± 0.10b | 6.21 ± 0.12b | 0.44 ± 0.14b |

DF-BSFL indicates black soldier fly defatted powder. P-U0, P-UL, and P-NA indicate the protein extracted by ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction without ultrasound, ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction and hot alkaline extraction, respectively. Values are given as means ± SD from triplicate determinations. Different letters (a–d) in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Values were expressed on dry matter basis.

3.2. Amino acid compositions

The amino acid compositions of the BSFLP samples obtained using the three extraction methods are shown in Table 3, and compared with those of soy protein and whey protein. The cystine content was not detected in the BSFLP samples obtained using the three extraction methods, probably because the destructive reaction of cystine occurred under alkaline conditions [33]. The summed amino acid content was lower in P-UL than P-U0, which was due to the lower purity of the protein (Table 2). The lower purity also resulted in a change in the amino acid content of the samples. The protein purity of P-NA was higher than that of P-UL, but the threonine, alanine, and serine contents of P-NA were lower than those of P-UL, which might have been caused by heating during the extraction process [28]. The BSFLP extracts obtained in this study contained detectable tryptophan, whereas previous studies did not detect tryptophan [11], [20].

Table 3.

Comparison of the amino acid composition of BSFLP obtained by three kinds of extraction methods with soy protein and whey protein.

| Amino acid (mg/g sample) | P-U0 | P-UL | P-NA | Soy Protein [34] | Whey Protein [34] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential amino acids (EAA) | |||||

| Histidine | 28.95 ± 0.07 a | 23.63 ± 0.34c | 26.09 ± 0.11b | 25 | 16 |

| Isoleucine | 49.03 ± 0.21b | 41.76 ± 0.13c | 49.71 ± 0.27 a | 49 | 74 |

| Leucine | 78.38 ± 0.21 a | 66.11 ± 0.13b | 78.87 ± 0.23 a | 56 | 121 |

| Lysine | 68.22 ± 1.26 a | 57.45 ± 0.31c | 61.28 ± 0.09b | 56 | 109 |

| Methionine | 24.6 ± 0.13b | 20.93 ± 0.20c | 27.42 ± 0.15 a | 14 | 25 |

| Phenylalanine | 58.56 ± 0.83 a | 46.71 ± 0.19b | 58.65 ± 0.20 a | 55 | 38 |

| Threonine | 35.85 ± 0.13 a | 29.54 ± 0.20b | 24.38 ± 0.15c | 39 | 88 |

| Tryptophan | 14.66 ± 0.02b | 13.29 ± 0.02c | 15.42 ± 0.14 a | 13 | 17 |

| Valine | 67.33 ± 0.20 a | 54.16 ± 0.08c | 58.34 ± 0.20b | 51 | 69 |

| Sum of EAA | 425.59 ± 2.24a | 353.58 ± 1.10c | 400.16 ± 1.18b | 358 | 557 |

| Non-essential amino acids | |||||

| Alanine | 56.33 ± 0.21 a | 46.26 ± 0.16b | 44.89 ± 0.19c | 45 | 55 |

| Arginine | 61.17 ± 0.22b | 54.01 ± 0.21c | 68.32 ± 0.18 a | 78 | 27 |

| Aspartic acid | 106.84 ± 0.38 a | 86.58 ± 0.64c | 101.77 ± 0.80b | 118 | 122 |

| Cystine | ND (<0.02) | ND (<0.02) | ND (<0.02) | 12 | 27 |

| Glutamic acid | 102.56 ± 0.30 a | 89.68 ± 0.48c | 100.50 ± 0.26b | 205 | 215 |

| Glycine | 45.32 ± 0.06 a | 36.94 ± 0.01c | 38.55 ± 0.05b | 44 | 23 |

| Proline | 59.83 ± 0.03 a | 47.18 ± 0.01c | 49.45 ± 0.03b | 49 | 61 |

| Serine | 41.81 ± 0.10 a | 34.50 ± 0.06b | 30.79 ± 0.08c | 52 | 67 |

| Tyrosine | 85.20 ± 0.46 a | 66.36 ± 0.15c | 75.22 ± 0.27b | 39 | 37 |

| Sum of AA | 984.65 ± 3.94 a | 815.10 ± 2.68c | 909.64 ± 1.67b | 988 | 1164 |

Values were given as means ± SD from triplicate determinations. Different letters (a–c) in the same row indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). ND: not detected. Values were calculated in dry mass.

The AAS or protein chemistry score is used widely to evaluate the nutritional value of protein [25]. Table 4 shows the AAS values for the proteins obtained from different samples. The essential AASs for all samples were greater than 100, and thus the BSFLP obtained using different extraction methods met the recommended protein intake requirements for adults defined by the FAO in 2013 [29]. The first limiting amino acid in samples P-U0 and P-UL was methionine, and the second limiting amino acid in P-U0 and P-UL was leucine. This suggests that the ultrasound-assisted extraction method did not alter the limiting amino acids of BSFLP, and that the small differences in the amino acid profiles were due to the purity of the sample proteins. Zhang et al. [25] applied ultrasonic power at 4 W/cm3 for 10 to 50 min for the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction of Tenebrio molitor larvae protein and found that ultrasound did not negatively affect the amino acid content and composition of the extracted protein. The amino acid compositions and first and second limiting amino acids in P-NA were different from those in P-U0 and P-UL, probably due to the higher heating temperature and longer extraction time with the former method. Since the limiting amino acids of P-U0 and P-UL are the same as those of soy protein, the amino acid composition of BSFLP is more similar to soy protein [34] than to whey protein [34]. Nutritionally, BSFLP can complement whey protein and increase amino acid utilization.

Table 4.

Amino acid scores of BSFP obtained by different extraction methods and the scoring pattern suggested by FAO (2013).

| Essential amino acids | FAO 2013 [29] (mg/g protein) | Amino acid Score (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-U0 | P-UL | P-NA | Soybean protein [34] | Whey protein [34] | ||

| Histidine | 16 | 214.90 | 182.87 | 192.88 | 156.25 | 100.00** |

| Isoleucine | 30 | 194.11 | 172.38 | 195.97 | 163.33 | 246.67 |

| Leucine | 61 | 152.62** | 134.21** | 152.92 | 91.80** | 198.36 |

| Lysine | 48 | 168.81 | 148.23 | 150.99 | 116.67 | 227.08 |

| Methionine | 23 | 127.16* | 112.69* | 141.01** | 60.87* | 108.70 |

| Phenylalanine | 41 | 169.64 | 141.09 | 169.20 | 134.15 | 92.68* |

| Threonine | 25 | 170.33 | 146.32 | 115.36* | 156.00 | 352.00 |

| Tryptophan | 6.6 | 263.75 | 249.35 | 276.33 | 196.97 | 257.58 |

| Valine | 40 | 199.93 | 167.69 | 172.49 | 127.50 | 172.50 |

| Sum of EAA | 290.6 | 173.95 | 150.68 | 162.86 | 123.19 | 191.67 |

*First limiting amino acid, **Second limiting amino acid. The amino acid content of the sample was converted to the amino acid content of the crude protein in the sample and then calculated.

3.3. Protein molecular weight distributions

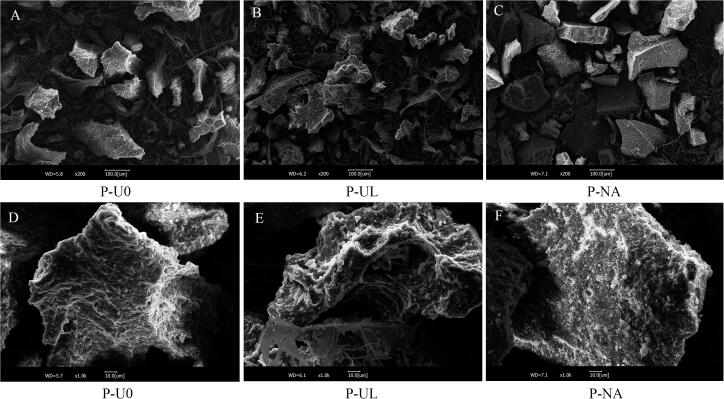

The effect of ultrasonic-assisted extraction on the molecular weight distribution in BSFLP was determined by SDS-PAGE. The bands obtained for DF-BSFL represented the molecular weight distribution of the unextracted protein in DF-BSFL. DF-BSFL has three major protein bands near 119, 88 and 75 kDa and three fainter bands near 230, 42 and 12 kDa. It is similar to the results obtained by Queiroz et al. [20]. Leni et al. [10] identified BSFL proteins by high resolution mass spectrometry and Myosin heavy chain (235 kDa), Hexamerin F1 (81 kDa, common in insects, used for storage of proteins), Actin-87E (42 kDa), Troponin C (18 kDa) were identified by database comparison. Rabani et al. [35] suggested the presence of structural and muscle proteins at 75 kDa. All three extraction methods affected the protein molecular weight distribution. Compared with DF-BSFL, the bands around 230 kDa were absent from P-U0, P-UL, and P-NA, but darker bands that appeared around 15 kDa indicated the hydrolysis of protein under strong alkaline conditions and its further breakdown into smaller proteins or peptides [36]. P-NA lacked distinct bands (molecular weights concentrated around 15 kDa), thereby indicating that greater protein hydrolysis occurred compared with P-U0 and P-UL, probably because the extraction of P-NA was conducted for a longer time at a higher temperature. Queiroz et al. [20] extracted black soldier fly larval protein with 0.25 mol/L NaOH for 1 h at 40 °C, which also had indistinct bands. Fig. 1 shows that the primary structure molecular weight profiles did not differ significantly between P-U0 and P-UL, and thus the ultrasonic-assisted extraction conditions did not have significant effects on the molecular weight distribution in BSFLP. These findings also suggest that the ultrasonic conditions (4.57 W/cm3, 1 h) did not break the protein bonds in BSFLP. Similar results were reported by Zou et al. [33] who demonstrated that ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction had no significant effects on chicken liver protein isolate. By contrast, Zhang et al. [26] found that cavitation effects due to ultrasound treatment at 4 W/cm3 and pH 10 resulted in the degradation of large molecular weight proteins into small molecules during Tenebrio molitor larvae protein extraction. These different results can be explained by differences in the protein structures among species.

Fig. 1.

Protein molecular weight distribution of defatted insect powder (DF-BSFL), PU-0, PU-L and P-NA.

3.4. Protein secondary structure

The circular dichroism spectra obtained for BSFLP extracted with different methods are shown in Fig. 2. Table 5 shows the percentages of protein secondary structures determined by analyzing the circular dichroism spectra with CDNN 2.1 software. Comparison of the spectra for P-U0 and P-UL showed that ultrasound-assisted extraction led to decreases in the amounts of random coil and β-turn, and increases in the amount of β-sheet, but no significant change in the amount of α-helix. The decrease in the amount of random coil and increase in the amount of β-sheet protein after ultrasonic treatment are consistent with the results obtained by Zou et al. [33] and Zhang et al. [25]. According to a previous study, ultrasound may partially unfold protein, break hydrogen bonds, and cause a decrease in rigid structure and an increase in flexible structure, thereby leading to changes in secondary structure [37]. However, the ultrasonic pulses applied during ultrasound-assisted extraction may lead to irregular protein reassembly [38], with the conversion of β-turn into random coil, where part of the random coil reassembles into β-sheet, thereby explaining the results obtained in the current study. Table 5 shows the more ordered and rigid protein secondary structure determined for P-NA.

Fig. 2.

Circular dichroism spectra of BSFLP obtained by different extraction methods.

Table 5.

Secondary structure of BSFLP obtained by different extraction methods.

| secondary structure | P-U0 | P-UL | P-NA |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-helix (%) | 11.33 ± 0.31a | 11.82 ± 0.08a | 11.74 ± 0.30a |

| β-sheet (%) | 40.03 ± 0.40c | 42.56 ± 0.09b | 43.55 ± 0.34a |

| β-turn (%) | 20.36 ± 0.08a | 19.32 ± 0.00b | 19.00 ± 0.06c |

| Random coil (%) | 28.29 ± 0.04a | 26.33 ± 0.04b | 25.64 ± 0.07c |

Values are given as means ± SD from triplicate determinations. Different letters (a–c) in the same row indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

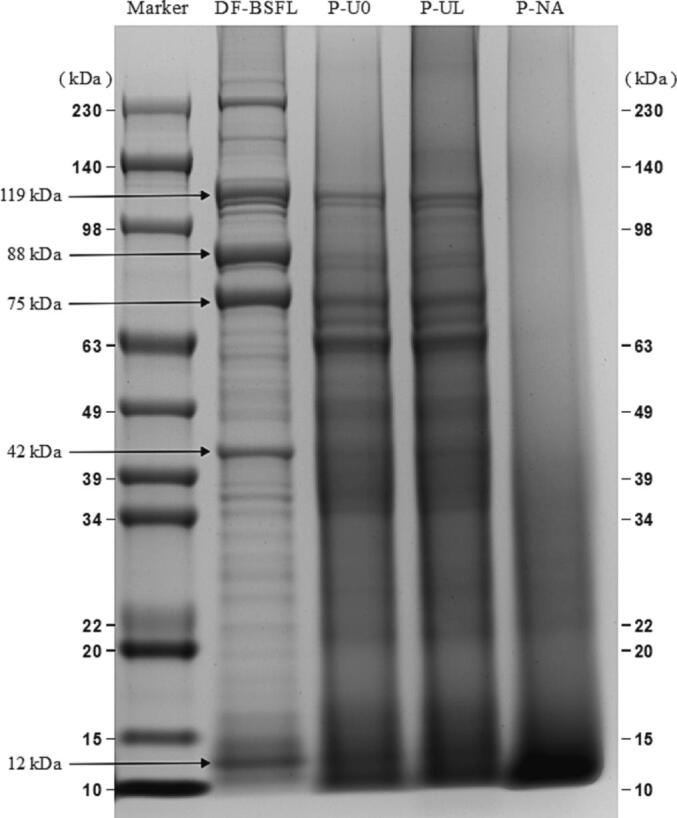

3.5. Microscopic surface morphology

The microstructure of food components greatly influences the techno-functional properties of food [39]. Therefore, determining the microscopic surface morphology of proteins can help to understand the differences in their physicochemical properties. Fig. 3 shows that the structures of the samples obtained under three treatments clearly differed, where P-U0 had a blocky structure with a rough surface, P-UL had a curly blocky structure with pits, and P-NA had a dense blocky structure. Compared with P-U0, P-UL had a more curled and concave structure, possibly due to the unfolding of protein aggregates caused by the cavitation effect generated by ultrasound. Li et al. [24] used scanning electron microscopy to show that ultrasound-assisted extraction produced more irregular and smaller fragments from krill protein, which they attributed to cavitation effects and turbulent flow. Stefanovic et al. [40] found that ultrasonic treatment disrupted the cross-linking in egg white protein, thereby resulting in fewer protein aggregates. The findings obtained in these studies are in agreement with our results. However, we found that P-NA had the densest and smoothest surface, possibly due to protein aggregation under long-term heat treatment.

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron micrographs of BSFLP obtained by different extraction methods.A, B, C magnified 200 x; D, E, F magnified 1000 x.

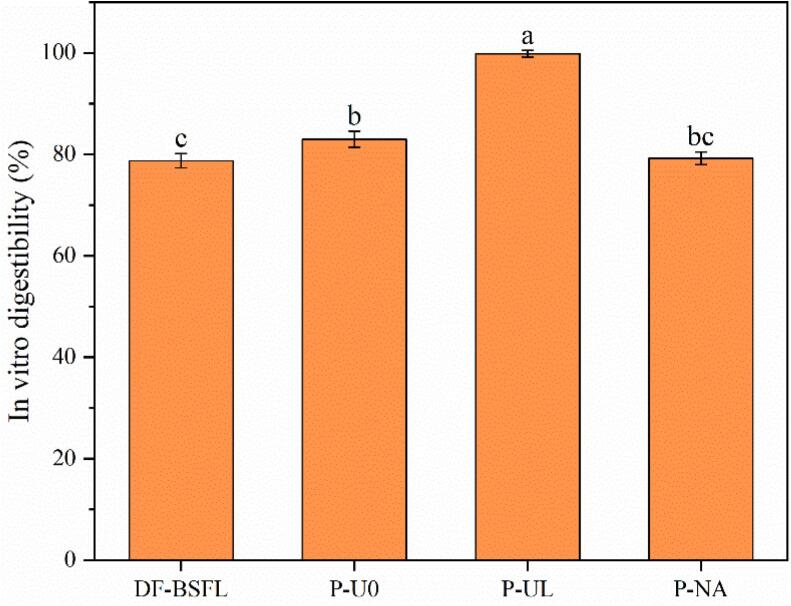

3.6. In vitro digestibility

In vitro simulated digestion can be used to effectively evaluate the bioavailability of protein [41]. Fig. 4 shows that the in vitro protein digestibility of DF-BSFL was 78.74 %, which is similar to the value of 75 % obtained experimentally by Traksele et al. [42]. After protein extraction, the in vitro protein digestibility values were 82.97 % for P-U0, 99.79 % for P-UL, and 79.24 % for P-NA. The in vitro protein digestibility was significantly higher for P-U0 and P-UL compared with DF-BSFL, but there was no significant difference between P-NA and DF-BSFL. The increase in the digestibility of P-U0 and P-UL can be explained by the removal of other substances, such as fat and chitin [42]. The lack of significant improvement in the digestibility of P-NA could be explained by protein aggregation due to the more rigid secondary structure (Table 5) of P-NA and its denser surface morphology (Fig. 3). Comparison of P-UL and P-U0 demonstrated that ultrasonic-assisted extraction significantly improved the in vitro protein digestibility of BSFLP. Similar results were obtained in previous studies for Tenebrio molitor larvae protein [26], shrimp protein [43], and rapeseed napin [44]. Ultrasound-assisted extraction can lead to proteins with a looser surface structure (Fig. 3) to increase the contact area and improve solubility, which in turn improves the in vitro digestibility of BSFLP. According to a previous study, the enhanced flexible structure of the protein could promote its binding to pepsin and improve its digestibility [45]. In vitro digestion studies by Melchior et al. [46] demonstrated that the digestibility values were 99.1 % for whey protein, 89.8 % for wheat, 84 % for pea protein, and 84 % for rice protein. In the present study, the in vitro protein digestibility of P-UL obtained by ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction was 99.79 %, which is comparable to that of whey protein.

Fig. 4.

In vitro protein digestibility of black soldier fly defatted powder and BSFLP.

3.7. Techno-functional properties

The water binding capacity of protein is a key property related to the water holding function, swelling, solubility, and gelation properties. The oil binding capacity indicates the capability of protein for absorbing and retaining fat [25]. Fig. 5A shows that the ultrasound-assisted extraction method used in this study had no significant effect on the water and oil binding capacities of BSFLP. The water and oil binding capacities of P-NA were significantly lower than those of P-U0 and P-UL, probably due to protein degradation (Fig. 1). The oil binding capacity of P-UL was 3.68 g/g, which is higher than the values of 1.35 g/g obtained previously for black soldier fly powder [47] and 1.82 g/g for Tenebrio molitor larvae protein [25]. The ability of protein to bind oil is crucial in formulations such as meat substitutes, sausages, and emulsions [48].

Fig. 5.

Techno-functional properties of BSFLP obtained by different extraction methods. A: water and oil binding capacity (WBC and OBC); B: solubility; C: foaming capacity and foam stability; D: emulsification capacity and emulsification stability.

The solubility is an important indicator of the functional properties of proteins because it is related to the ability to integrate into food systems. Fig. 5B shows that the solubility of P-UL was greater than that of P-U0, thereby indicating that ultrasound-assisted extraction could significantly improve the solubility of BSFLP. This difference in solubility can be explained by the large number of cavitation bubbles generated by ultrasound further increasing the partial pressure and temperature, and thus leading to unfolding of the protein. More hydrophilic amino acid residues were redirected toward water during this process to increase the protein’s solubility [49]. This greater solubility could also explain the higher in vitro digestibility of P-NA (Fig. 4) because the protein was more readily in contact with enzymes. The highest solubility of P-NA can be attributed to its lowest molecular weight (Fig. 1).

Proteins play important roles as foaming agents to increase the distribution of fine pores in the structure of processed foods [11]. Fig. 5b shows that the foaming capacity and foam stability of P-UL were lower than those of P-U0, and thus ultrasonic-assisted extraction reduced the foam performance of BSFLP. It is possible that the looser protein secondary structure P-U0 (Table 5) exposed more hydrophobic groups to form a more viscous air–water interface [20]. The higher solubility of P-UL reduced this ability. The foaming properties of P-UL were similar to those measured by Mshayisa et al. [11].

The amphiphilic nature of proteins allows them to form and stabilize food emulsions [11]. Fig. 5D show that the emulsification capacity was higher for P-UL than P-U0, with stronger protein–oil and protein–water interactions. The higher solubility and comparable oil binding capacity of P-UL compared to P-U0 could explain these findings. The emulsion capacity of P-UL was lower than that determined by Mshayisa et al. [11], which was about 100 %, and the emulsion stability was similar.

4. Conclusion

The BSFLP obtained by using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method developed in this study had higher nutritional value and better technical functional properties. In particular, ultrasound-assisted extraction significantly improved the extraction ratio, shortened the extraction time, and eliminated the need for heating and stirring. Ultrasound-assisted extraction slightly reduced the purity of BSFLP, but the protein still met the adult amino acid requirements proposed by the FAO in 2013. The ultrasound-assisted extraction method applied in this study did not break the peptide bonds in BSFLP, so its molecular weight distribution was not significantly affected. By contrast, the conventional hot alkaline method broke the protein bonds and reduced the average molecular weight. Ultrasound-assisted extraction reduced the amount of random coil in BSFLP and transformed it into more ordered β-sheet. Ultrasound-assisted extraction also obtained protein samples with a looser and more porous microscopic surface morphology. Ultrasound-assisted extraction obtained protein from BSFLP with greater solubility and a higher emulsion capacity, as well as lower foaming properties. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of BSFLP resulted in a very high in vitro digestibility value of 99.79 %, which was attributed to the higher solubility and looser surface morphology. This extremely high in vitro digestibility could make BSFLP easier to absorb and enhance its nutritional value. The BSFLP obtained by traditional hot alkali extraction had the lowest water and oil binding capacities and emulsification properties but the highest solubility.

Our findings may facilitate the application of ultrasound-assisted extraction techniques in the development of insect proteins and the application of BSFLP in food production. Future studies could explore the effects of ultrasonic-assisted extraction on the gelatinous properties of insect proteins. Ultrasound significantly improved the protein digestibility, and the mechanism involved also requires in-depth study.

Funding

This work was supported by Dongguan Institute of Science and Technology High Level Talent Research Start Project (GC300501-139), Project of Educational Commission of Guangdong Province of China (2021KTSCX132), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901682).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jia-hao Xu: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Shan Xiao: Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Ji-hui Wang: Funding acquisition, Visualization. Bo Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology. Yan-xue Cai: Conceptualization, Methodology. Wen-feng Hu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

BSFL: black soldier fly larvae.

BSFLP: black soldier fly larvae protein.

P-UL: BSFLP extracted by using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method.

P-U0: All of the experimental steps in the alkaline extraction method were consistent with those in the ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction method but the ultrasound power was 0 W.

P-NA: The BSFLP extracted by using the hot alkaline extraction method.

References

- 1.G.J. Abel, B. Barakat, S. KC, W. Lutz, Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals leads to lower world population growth, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113 (2016) 14294-14299. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611386113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Hopkins I., Newman L.P., Gill H., Danaher J. The Influence of Food Waste Rearing Substrates on Black Soldier Fly Larvae Protein Composition: A Systematic Review. Insects. 2021;12:608. doi: 10.3390/insects12070608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller A., Wolf D., Gutzeit H.O. The black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens – a promising source for sustainable production of proteins, lipids and bioactive substances. Zeitschrift Für Naturforschung C. 2017;72:351–363. doi: 10.1515/znc-2017-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.V.M. Villaseñor, J.N. Enriquez-Vara, J.E. Urías-Silva, L. Mojica, Edible Insects: Techno-functional Properties Food and Feed Applications and Biological Potential, Food Rev. Int., ahead-of-print (2021) 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2021.1890116.

- 5.van Huis A. Potential of insects as food and feed in assuring food security. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013;58:563–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mintah B.K., He R., Agyekum A.A., Dabbour M., Golly M.K., Ma H. Edible insect protein for food applications: Extraction, composition, and functional properties. J. Food Process Eng. 2020;43 doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomberlin J.K., Adler P.H., Myers H.M. Development of the black soldier fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) in relation to temperature. Environ. Entomol. 2009;38:930–934. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuso A., Barbi S., Macavei L.I., Luparelli A.V., Maistrello L., Montorsi M., Sforza S., Caligiani A. Effect of the Rearing Substrate on Total Protein and Amino Acid Composition in Black Soldier Fly. Foods. 2021;10:1773. doi: 10.3390/foods10081773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caligiani A., Marseglia A., Leni G., Baldassarre S., Maistrello L., Dossena A., Sforza S. Composition of black soldier fly prepupae and systematic approaches for extraction and fractionation of proteins, lipids and chitin. Food Res. Int. 2018;105:812–820. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leni G., Caligiani A., Sforza S. Killing method affects the browning and the quality of the protein fraction of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) prepupae: a metabolomics and proteomic insight. Food Res. Int. 2019;115:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mshayisa V.V., Van Wyk J., Zozo B. Nutritional, Techno-Functional and Structural Properties of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae Flours and Protein Concentrates. Foods. 2022;11:724. doi: 10.3390/foods11050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young V.R., Pellett P.L. Protein evaluation, amino acid scoring and the Food and Drug Administration's proposed food labeling regulations. J. Nutr. 1991;121 doi: 10.1093/jn/121.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leni G., Tedeschi T., Faccini A., Pratesi F., Folli C., Puxeddu I., Migliorini P., Gianotten N., Jacobs J., Depraetere S., Caligiani A., Sforza S. Shotgun proteomics, in-silico evaluation and immunoblotting assays for allergenicity assessment of lesser mealworm, black soldier fly and their protein hydrolysates. SCI REP-UK. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57863-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balzan S., Fasolato L., Maniero S., Novelli E. Edible insects and young adults in a north-east Italian city an exploratory study. Brit. Food J. 2016;118:318–326. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-04-2015-0156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro M., Chambers E. Consumer Avoidance of Insect Containing Foods: Primary Emotions, Perceptions and Sensory Characteristics Driving Consumers Considerations. Foods. 2019;8:351. doi: 10.3390/foods8080351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higa J.E., Ruby M.B., Rozin P. Americans’ acceptance of black soldier fly larvae as food for themselves, their dogs, and farmed animals. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bessa L.W., Pieterse E., Marais J., Dhanani K., Hoffman L.C. Food Safety of Consuming Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae: Microbial, Heavy Metal and Cross-Reactive Allergen Risks. Foods. 2021;10:1934. doi: 10.3390/foods10081934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lalander C., Diener S., Magri M.E., Zurbrügg C., Lindström A., Vinnerås B. Faecal sludge management with the larvae of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) — From a hygiene aspect. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;458–460:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S., Queiroz L.S., Marie R., Nascimento L.G.L., Mohammadifar M.A., de Carvalho A.F., Brouzes C.M.C., Fallquist H., Fraihi W., Casanova F. Gelling properties of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae protein after ultrasound treatment. Food Chem. 2022;386 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Queiroz L.S., Regnard M., Jessen F., Mohammadifar M.A., Sloth J.J., Petersen H.O., Ajalloueian F., Brouzes C.M.C., Fraihi W., Fallquist H., de Carvalho A.F., Casanova F. Physico-chemical and colloidal properties of protein extracted from black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;186:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Picó Y. Ultrasound-assisted extraction for food and environmental samples. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013;43:84–99. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2012.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun X., Zhang W., Zhang L., Tian S., Chen F. Effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction on the structure and emulsifying properties of peanut protein isolate. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2021;101:1150–1160. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingwascharapong P., Chaijan M., Karnjanapratum S. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of protein from Bombay locusts and its impact on functional and antioxidative properties. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96694-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y., Zeng Q., Liu G., Peng Z., Wang Y., Zhu Y., Liu H., Zhao Y., Jing Wang J. Effects of ultrasound-assisted basic electrolyzed water (BEW) extraction on structural and functional properties of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) proteins. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang F., Sun Z., Li X., Kong B., Sun F., Cao C., Chen Q., Zhang H., Liu Q. Ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction of protein from Tenebrio molitor larvae: Extraction kinetics, physiochemical, and functional traits. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang F., Yue Q., Li X., Kong B., Sun F., Cao C., Zhang H., Liu Q. Mechanisms underlying the effects of ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction on the structural properties and in vitro digestibility of Tenebrio molitor larvae protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;94 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Y., Zhang J., Song Z., Sun Y. Optimization of extraction of proteins from larvae of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), using response surface methodology. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2014;57:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zozo B., Wicht M.M., Mshayisa V.V., van Wyk J. Characterisation of black soldier fly larva protein before and after conjugation by the Maillard reaction. J. Insects Food Feed. 2022;8 doi: 10.3920/JIFF2021.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization (FAO/WHO), Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition. Report of an FAQ Expert Consultation, 2013. [PubMed]

- 30.Zielińska Dawidziak M., Tomczak A., Burzyńska M., Rokosik E., Dwiecki K., Piasecka Kwiatkowska D. Comparison ofLupinus angustifolius protein digestibility in dependence on protein, amino acids, trypsin inhibitors and polyphenolic compounds content. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;55:2029–2040. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodkorb A., Egger L., Alminger M., Alvito P., Assuncao R., Ballance S., Bohn T., Bourlieu-Lacanal C., Boutrou R., Carriere F., Clemente A., Corredig M., Dupont D., Dufour C., Edwards C., Golding M., Karakaya S., Kirkhus B., Le Feunteun S., Lesmes U., Macierzanka A., Mackie A.R., Martins C., Marze S., McClements D.J., Menard O., Minekus M., Portmann R., Santos C.N., Souchon I., Singh R.P., Vegarud G.E., Wickham M., Weitschies W., Recio I. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:991–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngasotter S., Sampath L., Xavier K.A.M. Nanochitin: An update review on advances in preparation methods and food applications. Carbohyd. Polym. 2022;291 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou Y., Li P.P., Zhang K., Wang L., Zhang M.H., Sun Z.L., Sun C., Geng Z.M., Xu W.M., Wang D.Y. Effects of ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction on the physiochemical and functional characteristics of chicken liver protein isolate. Poultry Sci. 2017;96 doi: 10.3382/ps/pex049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jue L., Marianne K., Monique V., Zandrie H. Amino Acid Availability of a Dairy and Vegetable Protein Blend Compared to Single Casein, Whey, Soy, and Pea Proteins: A Double-Blind, Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/nu11112613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabani V., Cheatsazan H., Davani S. Proteomics and Lipidomics of Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) and Blow Fly (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Larvae. J. Insect Sci. 2019;19 doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iez050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z., He S., Liu H., Sun X., Ye Y., Cao X., Wu Z., Sun H. Effect of pH regulation on the components and functional properties of proteins isolated from cold-pressed rapeseed meal through alkaline extraction and acid precipitation. Food Chem. 2020;327:126998. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng W., Yizhong Z., Ling X., Haile M. An efficient ultrasound-assisted extraction method of pea protein and its effect on protein functional properties and biological activities. LWT. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding Y., Ma H., Wang K., Azam S.M.R., Wang Y., Zhou J., Qu W. Ultrasound frequency effect on soybean protein: Acoustic field simulation, extraction rate and structure. LWT. 2021;145 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mshayisa V.V., Van Wyk J., Zozo B., Rodríguez S.D. Structural properties of native and conjugated black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae protein via Maillard reaction and classification by SIMCA. Heliyon. 2021;7:e07242. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefanovic A.B., Jovanovic J.R., Balanc B.D., Šekuljica N., Tanaskovic S.M.J., Dojcinovic M.B., Kneževic-Jugovic Z.D. Influence of ultrasound probe treatment time and protease type on functional and physicochemical characteristics of egg white protein hydrolysates. Poultry Sci. 2018;97 doi: 10.3382/ps/pey055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siwen X., Chong W., Yuan H.B.K., Guanglian B., Minyi H., Xinglian X., Guanghong Z. Application of high-pressure treatment improves the in vitro protein digestibility of gel-based meat product. Food Chem. 2020;306 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traksele L., Speiciene V., Smicius R., Alencikiene G., Salaseviciene A., Garmiene G., Zigmantaite V., Grigaleviciute R., Kucinskas A. Investigation of in vitro and in vivo digestibility of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae protein. J. Funct. Foods. 2021;79 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xin D., Jin W., Vijaya R. Effects of high-intensity ultrasound processing on the physiochemical and allergenic properties of shrimp. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020;65 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mengmeng P., Feiran X., Ying W., Meng Y., Xiang X., Na Z., Xingrong J., Lifeng W. Application of ultrasound-assisted physical mixing treatment improves in vitro protein digestibility of rapeseed napin. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang S., Zhao D., Nian Y., Wu J., Zhang M., Li Q., Li C. Ultrasonic treatment increased functional properties and in vitro digestion of actomyosin complex during meat storage. Food Chem. 2021;352 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melchior S., Moretton M., Alongi M., Calligaris S., Cristina N.M., Anese M. Comparison of protein in vitro digestibility under adult and elderly conditions: The case study of wheat, pea, rice, and whey proteins. Food Res. Int. 2023;163 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanqa N., Mshayisa V.V., Basitere M. Proximate, Physicochemical, Techno-Functional and Antioxidant Properties of Three Edible Insect (Gonimbrasia belina, Hermetia illucens and Macrotermes subhylanus) Flours. Foods. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/foods11070976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexia G., Alain D. The use of edible insect proteins in food: Challenges and issues related to their functional properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020;59 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2019.102272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Q., Wang Y., Huang M., Hayat K., Kurtz N.C., Wu X., Ahmad M., Zheng F. Ultrasound-assisted alkaline proteinase extraction enhances the yield of pecan protein and modifies its functional properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]