Abstract

In this study, we executed single-cell RNA sequencing of intestinal crypts. We analyzed the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at different time points (the first, third, and fifth days) after 13 Gy and 15 Gy abdominal body radiation (ABR) exposure and then executed gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, RNA velocity analysis, cell communication analysis, and ligand‒receptor interaction analysis to explore the vital events in damage repair and the multiple effects of the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway on irradiated mice. Results from bioinformatics analysis were confirmed by a series of biological experiments. Results showed that the antibacterial response is a vital event during the damage response process after 13 Gy ABR exposure; ionizing radiation (IR) induced high heterogeneity in the transient amplification (TA) cluster, which may differentiate into mature cells and stem cells in irradiated small intestine (SI) crypts. Conducting an enrichment analysis of the DEGs between mice exposed to 13 Gy and 15 Gy ABR, we concluded that the Wnt3/β-catenin and MIF-CD74/CD44 signaling pathways may contribute to 15 Gy ABR-induced mouse death. Wnt3/β-catenin promotes the recovery of irradiated SI stem/progenitor cells, which may trigger macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) release to further repair IR-induced SI injury; however, with the increase in radiation dose, activation of CD44 on macrophages provides the receptor for MIF signal transduction, initiating the inflammatory cascade response and ultimately causing a cytokine release syndrome. In contrast to previous research, we confirmed that inhibition of the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway or blockade of CD44 on the second day after 15 Gy ABR may significantly protect against ABR-induced death. This study indicates that the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway plays multiple roles in damage repair after IR exposure; we also propose a novel point that the interaction between intestinal crypt stem cells (ISCs) and macrophages through the MIF-CD74/CD44 axis may exacerbate SI damage in irradiated mice.

Keywords: Abdominal body radiation (ABR), Antibacterial response, Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)

Highlights

-

•

Anti-Bacterial response is a vital event during the damage repair after 13Gy abdominal body radiation (ABR) exposure.

-

•

IR induced a high heterogeneity in the transient amplification (TA) cluster.

-

•

There are multiple effects of the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway after ABR exposure.

-

•

MIF-CD74/CD44 may exacerbate high-dose radiation-induced small intestine damage.

1. Introduction

Radiotherapy is an important cancer treatment, but it is generally accompanied by unavoidable damage to normal tissues. The gastrointestinal tract is susceptible to IR. Abdominal and pelvic radiation exposure usually leads to intestinal injury, which limits the application of radiotherapy for abdominal and pelvic tumors. This limitation is an urgent clinical problem. IR leads to DNA damage and apoptosis in the intestinal epithelium, which reduces epithelial integrity and eventually leads to dysfunction in nutrient absorption [1]. It is well established that the death of differentiated cells and the loss of ISCs primarily contribute to radiation-induced intestinal damage [2,3]. The pluripotent Lgr5+ crypt base columnar (CBC) cells in the crypt are the primary cells responsible for the continual renewal of the intestinal epithelium [4]. However, although the proportion of Lgr5+CBC cells dramatically decrease after radiation exposure, the intestinal epithelium repair was still observed, indicating that many other factors are involved in the repair process after radiation exposure.

Ciara Metcalfe and colleagues found that Lgr5- reserve ISCs can replenish the damaged intestinal epithelium independently of Lgr5+CBC cells after radiation exposure [5]. The work of Kelley S, Yan and colleagues suggests that the resting reserve Bmi1+ ISCs located at site +4 primarily contribute to intestinal regeneration after high-dose radiation exposure [6]. Based on single-cell sequencing, Arshad Ayyaz and colleagues found that Clu + revSC cells transiently expand in a YAP1-dependent manner after radiation exposure, and they can produce all types of intestinal epithelial cells to regenerate the damaged small intestine [7]. Xiaole Sheng and colleagues identified a kind of Msi1+ cell called Cycling ISC, which can resist DNA damage and restore the radiation-induced intestinal epithelium [8]. Kazutaka Murata and colleagues verified that ASCL2-dependent dedifferentiation from absorptive progenitor cells and secretory progenitor cells near ISCs contributes to the rapid recovery of intestinal injury and the regeneration of the intestinal epithelium [9]. Above all, regeneration after intestinal epithelial damage is a complicated process, the dynamic changes in intestinal epithelial cells after radiation exposure still need to be clarified, and the critical signaling pathways involved in this process still needs to be further elucidated.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays multiple roles in biological processes. It retains intestinal homeostasis by regulating the self-renewal of intestinal stem cells and promoting the repair process of damaged intestinal stem cells [10]. Yong-Soo and colleagues have shown that lactate can stimulate the proliferation of ISCs after radiotherapy and chemotherapy through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [11]. Santosh and colleagues have shown that after 56Fe radiation exposure, the expression of markers of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which plays a vital role in the proliferation and localization of intestinal epithelial migration, is upregulated [12]. Moreover, in the gastrointestinal system, inflammatory cytokines play an essential role in the repair and regeneration of mammalian tissue by interacting with Wnt ligands [13,14]. However, whether the Wnt signaling pathway affects the damage repair process at different time points after IR and its role in regeneration and the inflammatory response have yet to be clarified.

To address the above issues, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was used in our experiment. We analyzed the DEGs at different time points (the first, third, and fifth days) in mice after 13 Gy and 15 Gy ABR exposure and then executed GO enrichment analysis, RNA velocity analysis, cell communication analysis, and ligand‒receptor interaction analysis to explore the vital events in damage repair and the multiple effects of the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway on irradiated mice. We further confirmed the results from the bioinformatics analysis through a series of biological experiments, including immunohistochemical (IHC) staining experiments and 3D organoid culture experiments testing Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway inhibition, CD44 blockade, and amifostine-mediated protection against 15 Gy ABR. We also propose a novel point that the interaction between ISCs and macrophages through the MIF-CD74/CD44 axis may exacerbate SI damage in irradiated mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental mice

Specific pathogen-free male C57BL/6 mice weighing 19–21 g were purchased from Beijing Huafukang Bioscience Co. Inc. (Beijing, China). The mice were housed at the Experimental Animal Centre of the Institute of Radiological Medicine of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences to acclimatize for one week.

2.2. IR

All mice were irradiated with a 137Cs γ-ray irradiator (Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, Chalk River, ON, Canada) at a dose rate of 0.89 Gy/min. The abdomen of the mice was exposed to the irradiator, and the rest of the body was shielded by lead. Radiation doses of 13 Gy and 15 Gy were used in the animal experiments, and 5 Gy was used in the 3D organoid culture experiment.

2.3. Experimental group

-

(1)

Mice in the scRNA-seq experiment were divided into five groups, including control, first-day post 13 Gy IR (13 Gy-1dpIR), third-day post 13 Gy IR (13 Gy-3dpIR), fifth-day post 13 Gy IR (13 Gy-5dpIR) and third-day post 15 Gy IR (15 Gy-3dpIR). There were three mice in each group.

-

(2)

In the survival study, mice in the LGK974 (Selleck, Cat. no S7143) experiment were divided into four groups: the ABR group, ABR + LGK974-1dpIR (3 mg/kg, oral gavage treatment immediately post ABR), ABR + LGK974-3dpIR (3 mg/kg, oral gavage treatment from the second day after ABR), ABR + LGK974-5dpIR (3 mg/kg, oral gavage treatment from the fourth day after ABR), with 11 mice in each group; the irradiation doses were 13 Gy and 15 Gy, and mice were administered LGK974 once daily.

-

(3)

Mice in the LF3 (Selleck, Cat. no S8474) experiment were divided into four groups: the ABR group, ABR + LF3-1dpIR (5 mg/kg, i.p. injection immediately after ABR), ABR + LF3-3dpIR (5 mg/kg, i.p. injection from the second day after ABR), ABR + LF3-5dpIR (5 mg/kg, i.p. injection from the fourth day after ABR), with 11–17 mice in each group. The irradiation doses were 13 Gy and 15 Gy, and mice were administered LF3 every other day.

-

(4)

Mice in the CD44 monoclonal antibody (MCE, Cat. no HY-P99126) experiment were divided into seven groups: the 15 Gy ABR group, 15 Gy ABR + isotype IgG2b-1dpIR (100 μg/mouse, i.p. injection immediately after ABR), 15 Gy ABR + CD44-1dpIR (100 μg/mouse, i.p. injection immediately after ABR), 15 Gy ABR + isotype IgG2b-3dpIR (100 μg/mouse, i.p. injection on the second day after ABR), 15 Gy ABR + CD44-3dpIR (100 μg/mouse, i.p. injection on the second day after ABR), 15 Gy ABR + isotype IgG2b-5dpIR (100 μg/mouse, i.p. injection on the fourth day after ABR), 15 Gy ABR + CD44-5dpIR (100 μg/mouse, i.p. injection on the fourth day after ABR); there were 12 mice in each group. Mice were administered CD44 or isotype IgG2b antibody (Selleck, Cat. no A2116) once.

-

(5)

Mice in the amifostine experiment were divided into four groups: control, control + amifostine (300 mg/kg, i.p. injection), 15 Gy ABR, and 15 Gy ABR + amifostine (300 mg/kg, i.p. injection 15 min before ABR), with three mice in each group. Mice were administered amifostine once.

2.4. Isolation of mouse intestinal crypt

After the mice were euthanized, an approximately 20 cm SI segment proximal to the pylorus was harvested; the SI was gently flushed with 1 mL cold (2–8 °C) PBS, and then all the payer's patches were removed. The SI segment was opened longitudinally and cut into 2 mm pieces, which was transferred into a 50 mL tube containing 20 mL cold PBS; The SI tissue in PBS was mixed by pipetting up and down three times, and this procedure was repeated until the supernatant was clear. The tissue pieces were resuspended in 25 mL of Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (GCDR, Stem Cell Technology, Cat. no 100–0485) and incubated on a shaker at 20 rpm for 15 min at room temperature. After discarding the GCDR, the tissue fragments were added to 10 mL 0.5 % BSA-PBS, pipetted up and down three times, and filtered through a 70 μm filter, and this procedure was repeated four times. Crypts obtained from fractions 3 and 4 were collected for further digestion with 5 mL 0.25 % trypsin for 30 min to harvest single cells.

2.5. Differentially expressed gene identification and functional pathway enrichment

The Find Markers function in Seurat was used to identify DEGs between two groups of cells with default parameters (logic. threshold = 0.25, test. use = ‘‘Wilcox,’’ min. pct = 0.1), and the enrich Pathway function in the cluster Profiler package (v.3.15.2)17 was used to perform functional analysis with differential gene sets annotated with the GO database (http://geneontology.org/) or Reactome pathway database (https://reactome.org/). Enrichment pathways were obtained with P.adjust <0.05. The false discovery rate (FDR) was estimated using the Benjamini‒Hochberg method.

2.6. Defining cell scores

We used the Add Module Score function in Seurat with default parameters to evaluate each cell score with a specific defined gene set. The module score of each sample was calculated with an average of all cells.

2.7. RNA velocity

The scvelo19 was used to execute the RNA velocity analysis. We first extracted the intron and exon expression matrix from the loom file, which was generated from a single R package, then we used a python package Anndata to generate Anndata, which combined the information (cell clusters, cell type, sample name, group name) from rds metadata and matrix from loom file. After Anndata was generated, we first used scv.pp.filter_and_normalize to perform the pretreatment of our data (adata, min_shared_counts = 30, n_top_genes = 2000). We calculated moments (scv.pp.moments (n_pcs = 30, n_neighbors = 30)) and velocity (scv.tl.velocity) with default parameters. RNA velocity visualization was performed using scv.pl.velocity_embedding_stream. The time scale was computed by using scv.tl.recover_latent_time, scv.tl.terminal_states, and scv.tl.latent_time with default parameters.

2.8. Regulon activity and CellChat analysis

We computed the gene regulatory network and analyzed the regulon activity of each cluster in each group from our scRNA-seq data by using SCENIC20 with default parameters. CellChat [15] was applied for our cell communication analysis. Ligand‒receptor interactions between each cell type were calculated from the scRNA-seq data using CellChat with default parameters.

2.9. Organoid culture

The mouse crypt was obtained as described above. Two hundred crypts were suspended in a 50 μL mixture of 1:1 IntestiCult™ Organoid Growth Medium (Stem cell technology, Cat. no 06005) and Matrigel (phenol red-free, BD Bioscience, Cat. no 356237). The crypts were transferred to prewarmed 24-well plates and covered with 750 μL complete medium. The organoids were exposed to 5 Gy IR 24 h after culture, 4 ng/mL WNT3A protein (R&D System, Cat.no 1324-WN-002/CF), 2 ng/mL WNT4 (R&D System, Cat.no 645-WN-010/CF), 2 ng/mL WNT5 protein (Abnova, Cat.no H00054361–P01), 200 ng/mL MIF protein (MCE, Cat.no HY-P7388), 1 nM LGK974, and 1.5 μM LF3 were supplemented immediately after radiation. The medium was replaced every three days, accompanied by supplementation with proteins and inhibitors. The images in Fig. 3J were collected on the fourth day after radiation, and those in Fig. 6D were collected on the seventh day after radiation. The area of organoids was evaluated by using ImageJ software.

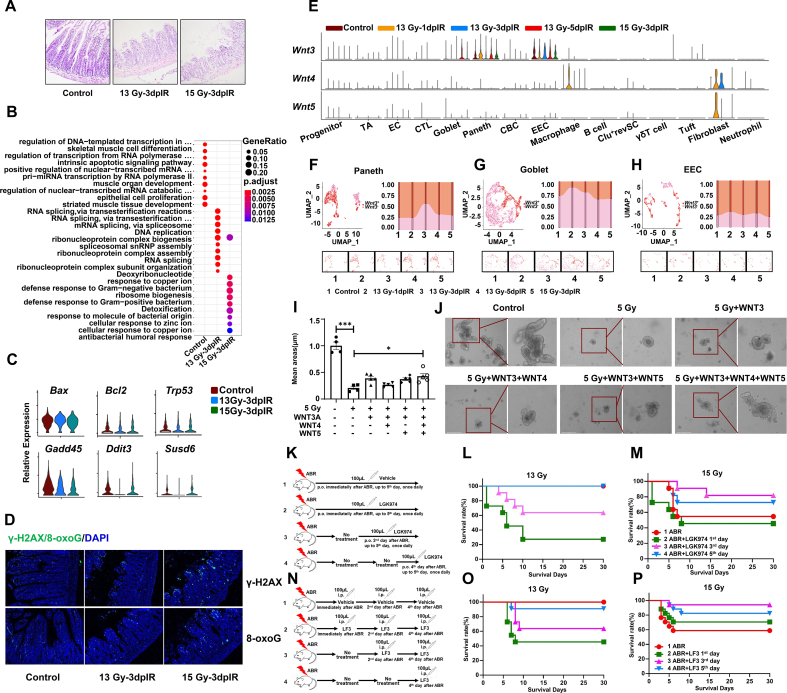

Fig. 3.

Exploration of the underlying mechanisms of 15 Gy ABR-induced death in mice and the contribution of Wnt ligands to radiation-induced SI injury.

N = 3 in Panel A; n = 11 in Panels L, M, O, and n = 17 in Panel P; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

(A) Representative images of HE staining in the mouse SI on the third day after 13 Gy and 15 Gy ABR.

(B) Dot plots showing the differentially enriched GO terms in the CBC cluster.

(C) Violin plots showing the expression of genes involved in cell apoptosis and the DNA damage response in the CBC cluster.

(D) Representative images of γ-H2AX and 8-oxoG staining in the mouse SI on the third day after ABR.

(E) Violin plots showing the expression of Wnt ligands in all clusters.

(F) UMAP visualization showing dynamic changes in the proportion of Wnt3+ cells in Paneth cells, (G) goblet cells, and (H) EECs.

(I) Bar graph showing the average area of organoids.

(J) Representative images of organoids.

(K) Schematic of LGK974 treatment experiment.

(L) The survival rate of mice administered LGK974 after 13 Gy ABR and (M) 15 Gy ABR exposure. (N) Schematic of LF3 treatment experiment.

(O) The survival rate of mice administered LF3 after 13 Gy ABR and (P) 15 Gy ABR exposure.

Fig. 6.

Amifostine inhibits the upregulation of CD44 and blocks its binding with MIF in macrophages.

N = 6 in Panel E, ***p < 0.001.

(A) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of 8-oxoG.

(B) Representative images of NRF2 immunofluorescence staining in macrophages.

(C) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of F4/80, CD44, and MIF in SI slides.

(D) Representative images of organoids.

(E) Bar graph showing the average area of organoids.

2.10. IHC staining

The SI segment was harvested and fixed with 4 % formalin, embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, MKI67 (Abcam, Cat. no ab16667), γ-H2AX (CST, Cat. no 9718), 8-oxoG (Millipore, Cat. no MAB3560), NRF2 (CST, Cat. no 12721), F4/80 (eBioscience, Cat. no 14-4801-82), CD44 (Abcam, Cat. no ab119348), MIF (Abcam, Cat. no ab187064), and the corresponding secondary antibodies. MKI67-stained tissue images were obtained using an Olympus BX53 system and immunofluorescence images were obtained using a Leica SP8 confocal system.

2.11. Flow cytometry analysis

For the detection of CD44 expression, 1*106 single cells from the SI crypt were incubated with CD45-BV510(Biolegend, Cat.no 103137), CD11b-FITC(Biolegend, Cat.no 101205), CD64-Percp (Biolegend, Cat.no 139307), F4/80-APC (Biolegend, Cat.no123116) and CD44-PE (eBioscience, Cat.no12-0441-82) for 30 min at 4 °C; for CD74 staining, SI crypt cells were incubated with CD45-BV510(Biolegend, Cat.no 103137), CD11b-APC-Cy7 (Biolegend, Cat.no 101225), CD64-Percp (Biolegend, Cat.no 101225), F4/80-APC (Biolegend, Cat.no123116), and CD74-AF488 (Biolegend, Cat.no151005) for 30 min at 4 °C. For CXCR4 staining, SI crypt cells were first incubated with CD45-BV510 (Biolegend, Cat.no 103137), CD11b-APC-Cy7 (Biolegend, Cat.no 101225), CD64-Percp (Biolegend, Cat.no 101225), and F4/80-APC (Biolegend, Cat.no123116) for 30 min at 4 °C. Then, the SI crypt cells were fixed, and permeabilized using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer according to the manufacturer's protocol, following staining with CXCR4 (Abcam, Cat.no ab124824) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L-AF488 (Abcam, Cat.no ab150077). All data acquisition was performed using a BD FACS Celesta and analyzed by FlowJo software.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons was used in the experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Dynamic changes in cell proportions and gene expression in SI crypts after exposure to 13 Gy ABR

The experimental scheme, cluster annotation and definition are illustrated in Fig. S1. CBC and TA cell proportions were significantly reduced on the first day after 13 Gy ABR and then returned to almost the control level in the next five days. Within the immune cells, γ δ T cells significantly increased on the first day and then decreased on the third and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR (Fig. 1A–B). We next evaluated the S phase score in cell cycle gene expression, as shown in Fig. 1C–D. The S phase score in the TA cluster gradually increased within three days and decreased to the control level on the fifth day after 13 Gy ABR exposure, while in the CBC cluster, there was an evident increase on the third day after 13 Gy ABR exposure. The DNA damage response (DDR) process could also be verified by HE staining, as shown in Fig. 1E. ABR caused structural damage to the SI, manifested by the shortening of the intestinal villi and disruption of the SI crypt integrity and barrier structure. The most severe damage was observed on the third day after 13 Gy ABR exposure. MKI67 staining showed the proliferative status of cells in the SI after radiation exposure. There was downregulated expression of MKI67 within three days after 13 Gy ABR exposure (Fig. 1E). Correspondingly, there was upregulated expression of S-phase genes, which means that the damage response mechanism can promote the regeneration of SI crypt stem cells after radiation exposure.

Fig. 1.

Cell composition and gene expression dynamics in mouse SI crypt after 13 Gy ABR.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(A) Proportions of all cell clusters.

(B) UMAP plots showing the dynamic changes in all clusters on the first, third, and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR.

(C) Box plots showing analysis of the S phase score in TA and (D) CBC cells on the first, third, and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR.

(E) Representative images of HE staining and MKI67 expression in the mouse SI on the first, third, and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR.

(F) Heatmap showing the top 10 differentially expressed genes in TA and (G) CBC cells.

(H) Dot plots showing the differentially enriched GO terms in TA and (I) CBC cells.

(J) Violin plots showing the expression of stem cell markers and genes involved in bacterial defense, the cell cycle, and apoptosis on the first, third, and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR in TA and CBC cells. N = 3 in Panel A.

It has been well established that the regeneration of CBC cells after radiation exposure is crucial for the reconstitution of the whole intestinal epithelium. Based on the significant changes in the proportion of CBC and TA cells after 13 Gy ABR exposure, we analyzed their transcriptome to explore the changes in gene expression. The top 10 DEGs between TA and CBC cells are shown in Fig. 1F–G, and many enriched genes were shared between the two clusters. NF-kappa-B-inhibitor alpha (Nfkbia) and transcription factor AP-1 complex genes (Atf3, Fosb, Fos, and Jun) were highly expressed in the control group and downregulated after 13 Gy ABR exposure. Genes related to the cell cycle (Ccng1, Cdkn1a), apoptosis (Areg, Phlda3, Bax), and defense response to bacteria (Defa24, Defa30, Zg16, Lyz1) were enriched on the first day after 13 Gy ABR exposure; redox-related genes (Selenoh, Mt1, Mt2, Gpx2), cell proliferation-related genes (Tubb5, mt−Rnr1, Plcaf), and an inhibitor of apoptosis gene (Birc5) were enriched on the third day after 13 Gy ABR exposure. Moreover, genes related to the defense response to bacteria and antimicrobial humoral response (Reg1, Reg3b, Reg3g, Defa21, Defa22, Defa24, Defa30) were enriched on the fifth day after 13 Gy ABR exposure. Violin gene expression statistics showed the same changes in the stem cell markers and genes associated with the cell cycle, apoptosis, and bacterial defense (Fig. 1J).

Consistent with the DEG results, the GO analysis of DEGs also illustrated a similar DDR process; the changes in TA cells on the first day after radiation exposure were mainly associated with p53-mediated apoptosis and defense response to bacteria. On the third day, the changes appeared to be associated with DNA replication. On the fifth day, the top 10 pathways could be classified as bacterial defense and antibacterial immune response pathways. The top 10 pathways in CBC cells were different from those in TA cells on the first day after radiation exposure; the changes in CBC cells were involved in bacterial defense, mucosal immune response, and regulation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity. Moreover, the changes in CBC cells on the third and fifth days were similar to those in TA cells (Fig. 1H–I). The above dynamic gene expression changes in CBC and TA cells illustrate a classic DDR process, which includes response to IR-induced DNA damage and apoptosis on the first day, stem cell regeneration on the third day, and response to challenges from the damaged microenvironment on the fifth day.

Notably, in this study, many upregulated genes expressed in CBC and TA cells were involved in the defense response of bacteria and antibacterial immune response. We further performed GO analysis on other cell types and found multiple antibacterial signaling pathways enriched in enteroendocrine (EEC), fibroblasts, and Clu + revSCs (Fig. S2). It is well known that Paneth cells secrete antimicrobial peptides to protect against bacterial infection in the gut [16]. Since several types of cells work together to resist bacterial invasion, it is suggested that bacterial infection may be a severe threat to the SI after radiation exposure, further revealing that host defenses against bacteria may be the most important event during DDR after exposure to 13 Gy ABR.

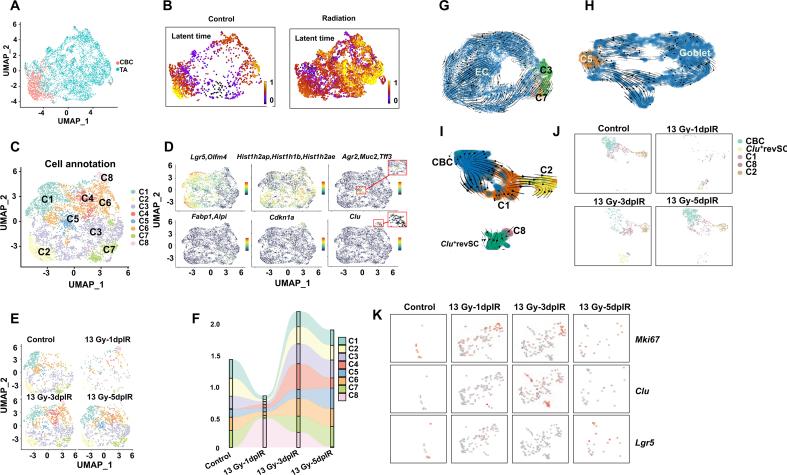

3.2. Radiation exposure-induced heterogeneity in the TA cluster

It is well established that mammalian intestinal epithelial cells are renewed every 3–5 days. CBC cells can sequentially differentiate into various absorptive and secreted progenitor cells to supplement intestinal epithelial cells [[16], [17], [18]]. Compared with that in the CBC cluster, the S phase score in the TA cluster was elevated on the first day after 13 Gy ABR, which means that TA cells proliferate earlier than CBC cells (Fig. 1C–D). To explore whether radiation affects the differentiation of CBC and TA cells, we elucidated the RNA velocity profiles of CBC and TA cells in both the control and radiation groups. The latent time describes the cell's position in an underlying biological process [19], and as shown in Fig. 2A–B, the nonirradiated CBC cells were toward the end of the latent time, indicating physical homeostasis of CBC cells in normal mice. After radiation exposure, TA cells became a highly heterogeneous cluster and included almost all the positions in latent time, suggesting that TA could be the critical cluster in the DDR process. We further subclustered the TA cells and explored the markers of CBC cells, progenitor cells, goblet cells, and ECCs as well as the cell cycle and Clu + revSCs in the TA subclusters, as shown in Fig. 2C–D. The CBC marker genes Lgr5 and Olfm4 were highly expressed in C1 and C2; the progenitor-enriched genes Hist1h2ap, Hist1h1b, and Hist1h2ae were highly expressed in C3; the goblet-specific genes Agr2, Muc2, and Tff3 were highly expressed in C5; the EC-enriched genes Fabp1 and Alpi were highly expressed in C7; and the Clu + revSC-enriched gene Clu and the cell cycle gene Cdkn1a were highly expressed in C8. The above data further confirm the heterogeneity in irradiated TA cells.

Fig. 2.

Trajectory analysis of SI crypt cell differentiation after radiation exposure.

(A) UMAP plots showing the cluster of CBC and TA cells.

(B) A continuous latent time of CBC and TA clusters in both control and irradiated mice based on RNA velocity modeling.

(C) UMAP plots showing the subclusters of TA cells; C1–C8 refer to Cluster 1-Cluster 8.

(D) UMAP plots showing the differentially expressed marker genes of CBC, progenitor, goblet, and EC cells as well as the cell cycle, and Clu + revSCs in all the subclusters.

(E) UMAP visualization showing dynamic changes in TA subclusters after 13 Gy ABR exposure.

(F) Dynamic changes in the proportion of TA subclusters after 13 Gy ABR exposure.

RNA velocity embedding stream showing the developmental trajectory from TA subcluster to (G) EC, (H) Goblet, (I) CBC, and Clu+revSCs after radiation exposure.

(J)UMAP plots showing dynamic changes in clusters in Panel (I).

(K)UMAP plots show the differential gene expression of Mki67, Clu, and Lgr5 after 13 Gy ABR in TA Cluster 8 and the Clu + revSC assembly.

We also subclustered the CBC and progenitor cells and explored the expression of the above cell type marker genes. Lgr5 and Olfm4 were highly expressed in all the CBC subclusters (Fig. S3A-B). In the progenitor cluster, Fabp1 and Alpi were highly expressed in C2; Agr2, Muc2, and Tff3 were highly expressed in C14; and Olfm4, Hist1h1b, and Hist1h2ae were enriched in most of the progenitor subclusters (Fig. S3C-D). The above results revealed that CBC and progenitor cells were less heterogeneous than TA cells.

We hypothesized that C1 and C2 in TA cells could differentiate into CBC cells; C3 could differentiate into progenitor cells; C5 could differentiate into goblet cells; C7 could differentiate into EC; and C8 could differentiate into Clu + revSC cells. The dynamic changes in the cell fraction were consistent with those in the corresponding crypt cells after radiation exposure (Fig. 2E–F). For example, CBC and TA cell proportions were significantly reduced on the first day after 13 Gy ABR and then returned to almost the control level in the next five days; the changes in the C1 and C2 fractions were completely consistent with those in the CBC cluster. RNA velocity is widely used to identify the “initial” and “terminal” transcriptomic states and assigns each cell a fate probability. Initial states indicate the lowest incoming transition probabilities, meaning cell states could be predicted as the precursor; conversely, terminal states refer to states with the highest self-transition probabilities [20]. We next computed RNA velocity profiles with scVelo dynamic modeling in each TA subcluster and its corresponding crypt cluster assembly. As shown in Fig. 2G–I, the results showed apparent transitions of C3 and C7 toward the EC cluster, C5 toward the goblet cluster, C1 and C2 toward the CBC cluster, and C8 toward the Clu + revSC cluster, suggesting there is high probability that the TA subcluster can differentiate into mature crypt cells and stem cells in irradiated SI crypts.

To further validate our hypothesis, we identified DEGs in the C8 and Clu + revSC assemblies, as shown in Fig. 2K. Mki67 and Clu were highly expressed in the C8 cluster after 13 Gy ABR exposure, while the CBC marker gene Lgr5 was expressed at low levels in the Clu + revSC cluster on the fifth day after 13 Gy ABR exposure. These results indicated that radiation exposure induced high heterogeneity in the TA cluster, and these cells could differentiate into mature cells or dedifferentiate into stem cells in irradiated SI crypts.

3.3. The Wnt signaling pathway may be involved in radiation-induced mortality in mice

As the radiation dose increased, the radiation-induced injury in mice SI became more severe (Fig. 3A). 15 Gy caused approximately 50 % of the mice in our experiment to die. We then executed GO enrichment analysis with the differentially expressed genes to explore the potential mechanism of radiation-induced mouse death. As shown in Fig. 3B, there was a noticeable difference only in the GO terms of CBC cells among all the intestinal cells. On the third day after 13 Gy ABR exposure, the GO terms mainly involved processes associated with DNA replication, including RNA splicing, ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis, and so on. After 15Gy ABR exposure, the GO terms specifically referred to the defense response to bacteria and metal ion response (cellular response to zinc ion and copper ion). The above results suggested that even on the third day after 15 Gy radiation exposure, instead of damage repair, CBC cells are still negatively affected by the radiation and are vulnerable to bacterial infection.

It is well known that radiation induces direct and indirect injury to cells and tissues, and the biological effects include cell apoptosis, DNA damage, and oxidative DNA damage. We then detected gene expression differences in cell apoptosis and DNA damage, as shown in Fig. 3C. Ddit3 and Susd6 were significantly upregulated after 15 Gy ABR, indicating the DNA damage response in 15 Gy-irradiated CBC cells. γ-H2AX and 8-oxoG staining confirmed the DNA damage status; there were more positively stained cells in the 15 Gy-irradiated SI crypt than in the 13 Gy-irradiated SI crypt (Fig. 3D), indicating more severe intestinal injury.

IR not only damages stem cells but also the microenvironment in the gut. We then illustrated the underlying mechanisms of both factors. It has been reported that Paneth cells maintain the ISC niche by releasing WNT3, EGF, TGF-α, and DLL4 [35]. The Wnt signaling pathway plays a critical role in maintaining the homeostasis of intestinal stem cells [36], and activating Wnt signaling could regenerate radiation-induced intestinal damage. Based on the above works, we analyzed the mRNA expression of Wnt ligands, including Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt3, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, and Wnt11, in all clusters. As shown in Figs. 3E and 13 Gy ABR induced the upregulation of Wnt4 and Wnt5 in macrophage and fibroblast clusters. As the primary Wnt ligand, Wnt3a was enriched in Paneth cells, EECs, and goblet cells, and Wnt3a was upregulated on the third day after 15 Gy ABR exposure compared with the 13 Gy group. We further investigated the changes in Wnt3+ cells in Paneth cells, EECs, and goblet cells, as shown in Fig. 3F–H. The fraction of Wnt3+ cells was higher in the 15 Gy ABR group than in the 13 Gy group. These results reveal that Wnt3a, Wnt4, and Wnt5 may contribute to the repair of radiation-induced intestinal crypt injury.

Wnt signaling pathways are divided into canonical and noncanonical Wnt pathways. Wnt3 function through the canonical pathway, and the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway is initiated by Wnt4 and Wnt5, which are recognized by Frz/retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (ROR)/receptor tyrosine kinase (RYK) receptor complexes [21]. We then determined the expression of Ror1, Ror2, and Ryk. As shown in Fig. S4, there was no enriched expression in any cluster, indicating that the canonical Wnt pathway could be involved in radiation-induced damage.

We first illustrated the possible role of Wnt4 and Wnt5 in radiation-induced SI damage by using a 3D organoid model. As shown in Fig. 3I–J, compared with the control group, there was a significant decrease in the area of organoids after 5 Gy radiation exposure, and supplementation with 4 ng/mL WNT3A, 2 ng/mL WNT4, and 2 ng/mL WNT5 proteins immediately after radiation exposure significantly alleviated organoid damage. The above data suggest that WNT4 and WNT5 could interact with WNT3A proteins to rescue radiation-induced intestinal stem cell injury.

LGK-974 is a specific and potent PORCN inhibitor that can inhibit the secretion of WNT1, 2, 3, 6, 7A, and 9A [22,23]. In our experiment, irradiated mice were administered 3 mg/kg LGK-974 at different time points (immediately, second day, and fourth day after ABR) to ensure that the secretion of WNT3 was inhibited on the first, third and fifth days after ABR exposure. As shown in Fig. 3K-M, no mice died in the irradiation group, and the mortality rate of mice treated with LGK-974 immediately, on the second day and on the fourth day after 13 Gy ABR was 72.7 %, 36.4 %, and 0 %, respectively, suggesting that WNT3 plays a vital role in the repair of radiation-induced SI injury. Interestingly, when the radiation dose increased to 15 Gy, the mortality rate was 45.4 % in the irradiation group and 54.5 %, 18.2 %, and 27.2 % in the groups treated with LGK-974 immediately, on the second day and on the fourth day after ABR, respectively, indicating that inhibition of WNT3 on the second day after 15 Gy exposure could significantly prevent radiation-induced mouse death.

LF3 is a compound interfering with the interaction between TCF4 and β-CATENIN. Next, the irradiated mice were administered 5 mg/kg LF3 at different times (immediately, on the second and fourth day) to ensure that the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway was blocked on the first, third and fifth days after ABR exposure. As shown in Fig. 3N-P, the mortality rate of mice treated with LF3 immediately, on the second day, and on the fourth day was 54.5 %, 36.4 %, and 9 %, respectively, confirming the vital role of the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway in the repair of radiation-induced injury at an early phase after radiation exposure. Consistent with LGK974 administration, when the radiation dose was increased to 15 Gy, the mortality rate was 41.1 % in the irradiation group and 29.4 %, 5.8 %, and 17.6 % mice treated in mice treated with LF3 immediately, on the second day, and on the fourth day after exposure to 15 Gy ABR.

The above data suggest that the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway exerts dual effects on radiation-induced SI injury. It is essential for damage repair immediately after ABR exposure and it may mediate mouse death after exposure to high radiation doses.

3.4. 15 Gy ABR may induce mouse death through the MIF-CD74/CD44 interaction between intestinal stem/progenitor cells and macrophages

To illustrate the underlying mechanisms by which the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway induced mouse death after 15 Gy ABR exposure, we executed a cell communication analysis using CellChat, and the ligand‒receptor interactions among all the clusters were determined. As shown in Fig. 4A, the Wnt ligands, enriched in Paneth cells, EECs, and goblet cells, mainly interact with receptor signals on CBC cells, TA cells, progenitor cells, and Clu + revSCs, with fewer incoming signaling patterns in the remaining clusters, confirming the critical role of Wnt signaling in the repair of intestinal stem/progenitor cell injury after radiation exposure. The pattern in WNT3 ligand‒receptor interaction was different among these clusters, as shown in Fig. S5. WNT3 interacted with CBC cells and Clu + revSCs through FZD2/FZD7/LRP5 and FZD5/LRP6 and interacted with progenitor and TA cells through FZD2/FZD7/LRP5/LRP6. The above results indicated that the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway plays a role in the damage repair of intestinal stem/progenitor cells, which may affect some other cells and induce more severe damage.

Fig. 4.

CellChat analysis of communications among all the clusters.

(A) Heatmap showing the predicted interaction signaling pattern among all the clusters.

(B) Dot plots showing the differentially enriched GO terms in macrophages.

(C) Heatmap showing regulon analysis to evaluate the differential expression of transcription factors in macrophages.

(D) Representative images of NRF2 immunofluorescence staining in macrophages.

(E) The underlying signaling network of MIF with CD74−CD44/CXCR2/CXCR4.

(F) Violin plots show the expression of MIF and its receptors.

(G) Ligand‒receptor interaction between macrophages and neutrophils.

(H) Violin plots showing gene expression in macrophages and neutrophils.

We analyzed the outgoing signaling patterns in CBC cells, TA cells, progenitor cells, and Clu + revSCs, focusing on the enriched ligands expressed in each cluster above and the receptors enriched in other clusters. Macrophage migration factor (MIF) matched our hypothesis and became a strong candidate for crosslinking among intestinal stem/progenitor cells and different kinds of cells. As expected, MIF signaling was highly expressed in macrophages (Fig. 4A), suggesting that intestinal stem/progenitor cells may affect macrophages via MIF signaling-mediated radiation-induced SI injury.

As shown in Fig. 3B, there was a noticeable difference only in the GO terms of CBC cells among all the intestinal epithelium cells. We then executed a GO enrichment analysis on the fibroblast and immune cells clusters. As shown in Fig. 4B, the apparent difference between 13 Gy and 15 Gy ABR was exhibited only in macrophages. On the third day after 13 Gy ABR exposure, the GO terms are mainly involved in the DNA replication and negative regulation of inflammatory response, while after 15 Gy ABR exposure, the GO terms specifically referred to the positive regulation of cell adhesion, external stimulus, cytokine production, and so on. We further executed a regulon analysis to evaluate the differential expression in transcription factors (TF), as shown in Fig. 4C, among all the clusters (including intestinal epithelium, immune cells, and fibroblasts), the macrophage cluster exhibited significantly differential expression of TFs. TFs associated with the inflammatory response (Cebpb (+), Egr1 (+), and so on) and the oxidative stress response (nfe2I2 (+), Maff (+), and so on) were significantly upregulated in macrophages in the 15 Gy ABR group compared to the control group and 13 Gy ABR group on the third day. We then performed immunofluorescence staining of F4/80 and NRF2 to confirm oxidative stress in macrophages. Compared with the control and 13 Gy ABR groups, the 15 Gy ABR group exhibited significant upregulation of NRF2 expression on the third day (Fig. 4D), indicating an overactivated oxidative stress state in macrophages after mice were exposed to higher doses of irradiation. The above data suggested that macrophages were under severe oxidative stress after 15 Gy ABR exposure, which may induce an inflammatory cascade reaction.

Next, we analyzed the interaction between MIF and its receptor complex, CD74/CXCR4, CD74-CXCR2, and CD74/CD44, among all the clusters. The interaction pattern for MIF-CD74/CXCR4 was observed in MIF-derived cells (almost all the cell types) such as macrophages and neutrophils. MIF-CD74/CXCR2 was present in neutrophils only. As a result of the enriched expression of CD44 in many clusters, the MIF-CD74/CD44 interaction pattern was widespread, not only in macrophages and neutrophils but also in stem/progenitor cells. Notably, CD44 was explicitly upregulated in macrophages on the third day after 15 Gy but not 13 Gy ABR (Fig. 4E–F). It has been reported that CD44 is an integral member of the CD74 receptor complex leading to MIF signal transduction, and CD74/CD44 is necessary for MIF-induced protection from apoptosis and the inflammatory response [24]. Based on the above results, we conclude that the MIF-CD74/CD44 interaction plays a vital role in the death of mice exposed to high doses of radiation.

Neutrophils are constantly generated in the bone marrow; they are recruited to the injury site and release inflammatory factors to mediate the inflammatory response [25]. In this experiment, the interaction of MIF and its receptors mainly occurs between macrophages and neutrophils; we further analyzed the ligand‒receptor interactions between them. As shown in Fig. 4G, after 15 Gy ABR exposure, there was a more robust interaction pattern in CCL3-CCR1, CXCL2-CXCR2, ANXA1-FPR/12, and TNF-TNFRSF1A/1B between macrophages and neutrophils than in the 13 Gy group; the mRNA expression of Ccl3, Cxcl2, Anxa1, Tnf, Fpr1, and Fpr2 was upregulated significantly in the 15 Gy group but not in the 13 Gy group (Fig. 4H).

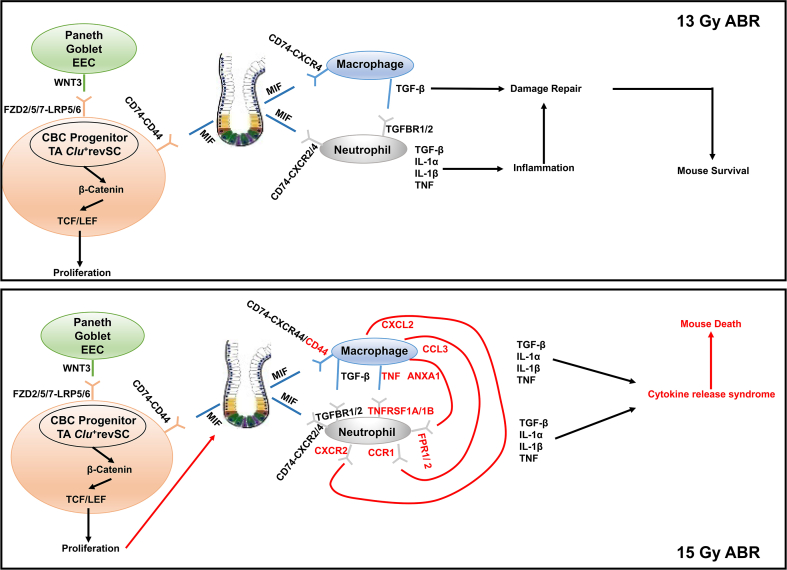

The results of the bioinformatics analysis suggest an underlying mechanism for ABR-induced mouse death; that is, Wnt3/β-catenin promotes the recovery of irradiated SI stem/progenitor cells, which may trigger MIF release to further repair IR-induced SI injury. However, with the increase in radiation dose, activation of CD44 on macrophages provides the receptor for MIF signal transduction, initiating the inflammatory cascade response and ultimately causing cytokine release syndrome.

3.5. Blocking CD44 using a neutralizing antibody on the second day after radiation could rescue 15 Gy ABR-induced mouse death

To illustrate the interaction between MIF and its receptors, we detected the expression of CD74, CD44, and CXCR4 in macrophages from the SI crypt. The payer's lymph nodes were removed, and then the SI crypts were harvested and further digested into single cells. CD74, CD44, and CXCR4 expression was evaluated using a flow cytometer, as shown in Fig. 5A–D. There was a significant upregulation of CD44 in macrophages on the third day after 15 Gy ABR exposure, but not CD74 and CXCR4. Next, we executed an IHC experiment to confirm the upregulated expression of CD44 on the 15 Gy irradiated macrophages. The SI tissue slides from the control mice and the irradiated mice (on the first, third, and fifth day after ABR exposure) were stained with F4/80, CD44, and MIF, and macrophages with both CD44 and MIF staining were considered positive. As shown in Fig. 5E, positive macrophages were extremely rare on the first day after 13 Gy ABR; on the third and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR, there were few macrophages positive for both CD44 and MIF binding. In contrast, after 15 Gy ABR exposure, there were more positively stained macrophages among all the time points than in the 13 Gy ABR group, suggesting a high dose radiation-induced upregulation of CD44 in macrophages. In addition, we observed an interesting CD44 expression pattern, and it seems that MIF prefers to bind CD44 in SI epithelial cells after mice were exposed to 13 Gy ABR. Moreover, MIF binding to CD44 occurs more frequently in macrophages after 15 Gy irradiation than in the 13 Gy ABR group.

Fig. 5.

Activation of CD44 in macrophages is a vital factor in 15 Gy ABR-induced mouse death.

N = 6 in Panels B–D; n = 12 in Panels G–I, ***p < 0.001.

(A) Representative FACS images showing the gating for SI macrophages and the expression of CD74, CD44, and CXCR4.

(B) Bar graph showing the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD74; (C) CD44; and (D) CXCR4.

(E) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of F4/80, CD44, and MIF in SI slides.

(F) Experimental scheme of isotype/CD44 antibody treatment.

(G) The survival rate of mice administered isotype/CD44 antibody immediately, (H) on the second day, and (I) on the fourth day after 15 Gy ABR exposure.

Next, we treated the irradiated mice with a CD44 monoclonal antibody to block the signal transduction of MIF-CD74/CD44. As shown in Fig. 5F, mice were administered 100 μg of IgG2b isotope or CD44 monoclonal antibody at three time points (immediately, the second day, and the fourth day after ABR). CD44 blockade immediately after 15 Gy accelerated mouse death. Unexpectedly, treatment with isotype IgG2b immediately after 15 Gy ABR prevented IR-induced death (Fig. 5G–I), which should be further explored. The mortality rate was 66.7 % in the 15 Gy ABR group. When the irradiated mice were treated with CD44 monoclonal antibody on the second and fourth day after being exposed to 15 Gy ABR, the mortality rate was 33.3 % and 66.7 %, respectively. Treatment with IgG2b on the second and fourth day after 15 Gy ABR exposure could not prevent radiation-induced mice death.

Above all, 15 Gy ABR may induce the upregulation of CD44 and increase the binding of MIF to CD44 in macrophages. Blockade of CD44 with a monoclonal antibody on the second day after 15 Gy ABR exposure could effectively reduce mouse death.

3.6. Amifostine, as a radioprotector, effectively inhibits the upregulation of CD44 and blocks its binding with MIF in macrophages

It has been well established that amifostine alleviates radiation-induced tissue injury by scavenging free radicals [26], and it is often used as a positive control to evaluate a potential radioprotector [27]. To further confirm the relationship between CD44 activation in macrophages and high-dose radiation-induced mouse death, amifostine was administered by gavage to mice 15 min before IR. The SI was harvested, and tissue slides were prepared for IHC staining. In our experiment, 15 Gy ABR induced oxidative DNA damage in the SI epithelium and NRF2 activation in macrophages (Figs. 3D and 4D); amifostine reduced the number of 8-oxoG-positive cells (Fig. 6A) and downregulated NRF2 expression in macrophages (Fig. 6B), indicating that there was a strong correlation between 15 Gy ABR-induced SI injury and oxidative stress. We further evaluated the effect of amifostine on CD44 activation. As shown in Fig. 6C, there were more positively stained macrophages (F4/80+CD44+MIF+) in the 15 Gy ABR group (the left enlarged image), and amifostine could effectively inhibit CD44 expression and block its binding with MIF. Furthermore, amifostine promoted MIF binding with CD44 in the SI epithelium (right enlarged image), especially in the SI crypts, indicating a radioprotective effect of MIF on SI stem/progenitor cells.

As mentioned in the bioinformatics analysis, Wnt3/β-catenin promotes the recovery of irradiated SI stem/progenitor cells, which may trigger MIF release to repair IR-induced SI injury. Therefore, this positive feedback loop promotes damage repair. We executed organoid culture to verify the radioprotective effect of MIF on SI stem/progenitor cells. As shown in Fig. 6D–E, in the nonirradiated organoids, compared with the control, MIF did not affect organoid growth; LGK974 and LF3 significantly inhibited organoid growth, and MIF could not rescue the effect of the Wnt3/β-catenin inhibitor. In the irradiated organoids, MIF effectively elevated the average area of the irradiated SI organoids, and inhibiting Wnt3/β-catenin exacerbated radiation-induced organoid injury. Furthermore, when the organoids were cocultured with LGK974 or LF3, MIF no longer functioned as a radioprotector, suggesting that MIF protects against IR-induced organoid injury through the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway.

The above results indicate that the therapeutic strategy to rescue radiation-induced damage by scavenging oxygen radicals could inhibit CD44 expression in macrophages and promote the binding of MIF with CD44 in the intestinal epithelium, which repairs radiation damage.

4. Discussion

Radiation doses of 13 Gy and 15 Gy were used in this study. According to previous reports [8,10] and our experiments, 13 Gy ABR-induced SI damage could be repaired and did not cause death in mice, and 15 Gy ABR is a half-lethal dose for C57BL/6 mice. In general, the first five days after radiation exposure is a critical period for damage repair. As a result of ABR exposure, the mature and stem/progenitor cells undergo rapid DNA damage, apoptosis, and necrosis in the SI epithelium within one day after 13 Gy ABR. Then, the surviving cells respond to the damage and regenerate the damaged SI within the following days. After ABR exposure, the body weight of mice significantly decreases, but this change can be rescued within 3–4 days if the irradiated mice survived. Therefore, our experiment harvested SI crypt cells on the first, third, and fifth days after 13 Gy ABR exposure to explore the radiation-induced intestinal injury repair process. At the same time, SI crypt cells were obtained on the third day after 15 Gy ABR to illustrate the underlying mechanisms of high-dose IR-induced mouse death. Our research analyzed SI epithelial cells and immune cells adjacent to the SI crypt.

There were dynamic changes in cell proportions at different time points after 13 Gy ABR exposure. Among them, the proportions of CBC and TA cells significantly decreased in the 13Gy-1dpIR group. They gradually increased to almost the control level on the fifth day, consistent with the SI structure repair in HE staining. Paneth cells can secrete antimicrobial peptides (such as Defa family genes) and participate in the anti-infection immunity of SI [28]. In our study, we found that genes in the Defa family and Reg family were highly enriched in CBC cells, TA cells, Paneth cells, EECs, Clu + revSC, and fibroblasts in the 13Gy-1dpIR group, suggesting that most of the cells functioned as bacterial defenders during severe SI injury, further indicating that bacterial defense is vital in the damage repair process after ABR exposure. The above results are consistent with previous reports; there are dramatic changes in intestinal bacterial communities after ABR exposure, and fecal microbiota transplantation or supplementation with microbial metabolites protects against radiation-induced toxicity [[29], [30], [31]].

After being exposed to IR, TA cells switch to be a highly heterogeneous cluster; they have the potential not only to differentiate into progenitor cells and mature cells but also to dedifferentiate into CBC cells and Clu + revSCs. This analysis could explain the rapid SI epithelium reconstitution post-ABR exposure even when Lgr5+CBC numbers are significantly decreased. It has been reported that Clu + revSC cells robustly expand in a YAP1-dependent manner after radiation exposure [7]; in this study, the C8 cluster of TA cells were predicted to dedifferentiate Clu + revSCs. The cluster rapidly proliferated on the first day, then its ratio decreased on the third day and returned to almost the control level on the fifth day after 13 Gy ABR exposure, corresponding to the highest percentage of Clu + revSCs on the third day after 13 Gy ABR. Therefore, the dedifferentiation from the irradiated TA cluster to Clu + revSCs may complement the YAP-dependent expansion of Clu + revSCs. Kazutaka and colleagues reported that SI stem cell regeneration could be explained entirely by ASCL2-mediated dedifferentiation after IR exposure, with contributions from absorptive and secretory progenitors [9], indicating an underlying dedifferentiation mechanism contributing to SI reconstitution that deserves to be further explored.

The Wnt signaling pathway is necessary to maintain the homeostasis of intestinal stem cells, and activation of the Wnt pathway could repair radiation-induced intestinal damage [32,33]. This study reveals a novel role of the Wnt pathway; it may be an essential factor in high-dose radiation-induced mouse injury. Inhibition of the Wnt3/β-catenin signaling pathway on the second day after 15 Gy ABR exposure could effectively prevent IR-induced mouse death. Previous research has focused on radiation-protective or therapeutic drugs, which must be administered immediately before or after radiation exposure to achieve excellent therapeutic effects. Few compounds are potent when applied on the second day after IR exposure. These results suggest a personalized treatment strategy for high-dose radiation-induced SI injury.

By computing the GO enrichment analysis of DEGs between 13 Gy and 15 Gy ABR groups, we found that the GO terms in CBC cells and macrophages exhibit a significant difference. The specific interaction between macrophage MIF from CBC cells and CD74/CD44 in macrophages could be vital because there was an upregulation of CD44 expression in 15 Gy-irradiated but not in 13 Gy-irradiated macrophages. We explored the role of Wnt3/β-catenin in 15 Gy ABR-induced mouse death by focusing on the MIF-CD74/CD44 axis.

It has been well established that MIF-CD74/CD44 mediates multiple biological processes, including cell proliferation and the inflammatory response. Laura and colleagues reported that during the intestinal inflammation period, epithelial cells constitutively express MIF, which interacts with CD74 to activate proliferative pathways in intestinal epithelial cells [34]. Shi and colleagues reported that CD74 and CD44 transformants are necessary for MIF protection from cell apoptosis [24]. Djudjaj and colleagues illustrated that the proliferative effects of MIF may involve CD74 together with the activation marker CD44 [35]. Regarding the inflammatory response, it has been demonstrated that the upregulated expression of CD44 is a marker for inflammatory macrophages [36]. Tessaro and colleagues confirmed that MIF secreted from sarcoma cells interacts with macrophages through the CD74 receptor and could switch macrophage activation [37]. Above, MIF-CD74/CD44 is an excellent candidate to explore the mechanism for Wnt3/β-catenin-mediated 15 Gy ABR-induced mouse death.

Our biological experiments support this hypothesis. 15Gy ABR induces the upregulated expression of CD44 and binding of MIF in macrophages; blockade of CD44 immediately after IR exposure induced rapid mortality in mice as a result of inhibiting proliferation. However, CD44 blockade on the second day after IR exposure could elevate the survival rate of 15 Gy ABR-irradiated mice, indicating that CD44 blockade could prevent the activation of inflammatory macrophages and inhibit the possible inflammatory cascade response. As a result of the excessive oxidative stress in macrophages, amifostine treatment could also effectively inhibit CD44 expression and block its binding with MIF. Furthermore, amifostine promoted MIF binding with CD44 in the SI epithelium, especially in the SI crypts, illustrating a radioprotective effect of MIF on SI stem/progenitor cells.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates an underlying mechanism for high-dose ABR-induced mouse death, that is, inhibition of the Wnt3/β-catenin pathway promotes the recovery of irradiated SI stem/progenitor cells, which may trigger MIF release to further repair IR-induced SI injury. While, with the increase in radiation dose, activation of CD44 on macrophages provide the receptor for MIF signal transduction, initiating the inflammatory cascade response and ultimately causing a cytokine release syndrome (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Overview of the underlying mechanisms of damage repair after ABR in mice.

Ethics statement

The Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Radiation Medicine, Peking Union Medical College, and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences approved all use of animals in this study. All experimental procedures in this study complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Funding

This study was supported by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, No. 2021-I2M-1–042) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730086).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tong Yuan: executed the biological experiments and wrote the manuscript. Junling Zhang: designed the project, executed the biological experiments and wrote the manuscript. Yue Zhao: performed computational analyses. Yuying Guo: executed the biological experiments. Saijun Fan: designed the project and funded the project.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102942.

Contributor Information

Junling Zhang, Email: zhangjunling@irm-cams.ac.cn.

Saijun Fan, Email: fansaijun@irm-cams.ac.cn.

Abbreviation

- Crypt base columnar

CBC

- Transient amplification

TA

- Enterocyte

EC

- Enteroendocrine

EEC

- Cytotoxic T-cell

CTL

- Intestinal crypt stem cells

ISC

- Small intestine

SI

- Ionizing radiation

IR

- Abdominal body radiation

ABR

- Single-cell RNA-sequencing

scRNA-seq

- Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

MIF

- Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent

GCDR

- Differential expressed genes

DEGs

- DNA damage response

DDR

- Immunohistochemical

IHC

- Gene ontology

GO

- Transcription factors

TF

- Frz/retinoic acid-related orphan receptor

ROR

- Receptor tyrosine kinase

RYK

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Hu B., Jin C., Li H.B., et al. The DNA-sensing AIM2 inflammasome controls radiation-induced cell death and tissue injury. Science. 2016;354(6313):765–768. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregorieff A., Liu Y., Inanlou M.R., Khomchuk Y., Wrana J.L. Yap-dependent reprogramming of Lgr5(+) stem cells drives intestinal regeneration and cancer. Nature. 2015;526(7575):715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature15382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindemans C.A., Calafiore M., Mertelsmann A.M., et al. Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature. 2015;528(7583):560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature16460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker N., van Es J.H., Kuipers J., et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449(7165):1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metcalfe C., Kljavin N.M., Ybarra R., de Sauvage F.J. Lgr5+ stem cells are indispensable for radiation-induced intestinal regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(2):149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan K.S., Chia L.A., Li X., et al. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109(2):466–471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118857109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayyaz A., Kumar S., Sangiorgi B., et al. Single-cell transcriptomes of the regenerating intestine reveal a revival stem cell. Nature. 2019;569(7754):121–125. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1154-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheng X., Lin Z., Lv C., et al. Cycling stem cells are radioresistant and regenerate the intestine. Cell Rep. 2020;32(4) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murata K., Jadhav U., Madha S., et al. Ascl2-Dependent cell dedifferentiation drives regeneration of ablated intestinal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26(3):377–390.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clevers H., Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149(6):1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y.S., Kim T.Y., Kim Y., et al. Microbiota-derived lactate accelerates intestinal stem-cell-mediated epithelial development. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24(6):833–846.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S., Suman S., Fornace A.J., Jr., Datta K. Space radiation triggers persistent stress response, increases senescent signaling, and decreases cell migration in mouse intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115(42):E9832–E9841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807522115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karin M., Clevers H. Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature. 2016;529(7586):307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature17039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moparthi L., Koch S. Wnt signaling in intestinal inflammation. Differentiation. 2019;108:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin S., Guerrero-Juarez C.F., Zhang L., et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1088. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanman L.E., Chen I.W., Bieber J.M., et al. Transit-amplifying cells coordinate changes in intestinal epithelial cell-type composition. Dev. Cell. 2021;56(3):356–365.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoll P., Härle F., Schilli W. [Transplantation of a 3d molar into an autologous iliac crest graft in the mandible. A case report] Dtsch Z Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1987;11(1):5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yousefi M., Li L., Lengner C.J. Hierarchy and plasticity in the intestinal stem cell compartment. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(10):753–764. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergen V., Lange M., Peidli S., Wolf F.A., Theis F.J. Generalizing RNA velocity to transient cell states through dynamical modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38(12):1408–1414. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guetta-Terrier C., Karambizi D., Akosman B., et al. Chi3l1 is a modulator of glioma stem cell states and a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2023;83(12):1984–1999. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chae W.J., Bothwell A. Canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling in immune cells. Trends Immunol. 2018;39(10):830–847. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah K., Panchal S., Patel B. Porcupine inhibitors: novel and emerging anti-cancer therapeutics targeting the Wnt signaling pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 2021;167 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J., Pan S., Hsieh M.H., et al. Targeting wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of porcupine by LGK974. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110(50):20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi X., Leng L., Wang T., et al. CD44 is the signaling component of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor-CD74 receptor complex. Immunity. 2006;25(4):595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liew P.X., Kubes P. The neutrophil's role during Health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019;99(2):1223–1248. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culy C.R., Spencer C.M. Amifostine: an update on its clinical status as a cytoprotectant in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy and its potential therapeutic application in myelodysplastic syndrome. Drugs. 2001;61(5):641–684. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J., Li K., Zhang Q., Zhu Z., Huang G., Tian H. Polycysteine as a new type of radio-protector ameliorated tissue injury through inhibiting ferroptosis in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(2):195. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03479-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai Y.H., VanDussen K.L., Sawey E.T., et al. ADAM10 regulates Notch function in intestinal stem cells of mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):822–834.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao H.W., Cui M., Li Y., et al. Gut microbiota-derived indole 3-propionic acid protects against radiation toxicity via retaining acyl-CoA-binding protein. Microbiome. 2020;8(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00845-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Dong J., Xiao H., et al. Gut commensal derived-valeric acid protects against radiation injuries. Gut Microb. 2020;11(4):789–806. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2019.1709387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui M., Xiao H., Li Y., et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation protects against radiation-induced toxicity. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017;9(4):448–461. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Q., Lin Y., Sheng X., et al. Arachidonic acid promotes intestinal regeneration by activating WNT signaling. Stem Cell Rep. 2020;15(2):374–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong W., Guo M., Han Z., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells stimulate intestinal stem cells to repair radiation-induced intestinal injury. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(9):e2387. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farr L., Ghosh S., Jiang N., et al. CD74 signaling links inflammation to intestinal epithelial cell regeneration and promotes mucosal healing. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;10(1):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djudjaj S., Lue H., Rong S., et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor mediates proliferative GN via CD74. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016;27(6):1650–1664. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solier S., Müller S., Cañeque T., et al. A druggable copper-signalling pathway that drives inflammation. Nature. 2023;617(7960):386–394. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tessaro F., Ko E.Y., De Simone M., et al. Single-cell RNA-seq of a soft-tissue sarcoma model reveals the critical role of tumor-expressed MIF in shaping macrophage heterogeneity. Cell Rep. 2022;39(12) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.