Abstract

Superintegrons (SIs) and multiresistant integrons (MRIs) have two main structural differences: (i) the SI platform is sedentary, while the MRI platform is commonly associated with mobile DNA elements and (ii) the recombination sites (attC) of SI gene cassette clusters are highly homogeneous, while those of MRI cassette arrays are highly variable in length and sequence. In order to determine if the latter difference was correlated with a dissimilarity in the recombination activities, we conducted a comparative study of the integron integrases of the class 1 MRI (IntI1) and the Vibrio cholerae SI (VchIntIA). We developed two assays that allowed us to independently measure the frequencies of cassette deletion and integration at the cognate attI sites. We demonstrated that the range of attC sites efficiently recombined by VchIntIA is narrower than the range of attC sites efficiently recombined by IntI1. Introduction of mutations into the V. cholerae repeats (VCRs), the attC sites of the V. cholerae SI cassettes, allowed us to map positions that affected the VchIntIA and IntI1 activities to different extents. Using a cointegration assay, we established that in E. coli, attI1-×-VCR recombination catalyzed by IntI1 was 2,600-fold more efficient than attIVch-×-VCR recombination catalyzed by VchIntIA. We performed the same experiments in V. cholerae and established that the attIVch-×-VCR recombination catalyzed by VchIntIA was 2,000-fold greater than the recombination measured in E. coli. Taken together, our results indicate that in the V. cholerae SI, the substrate recognition and recombination reactions mediated by VchIntIA might differ from the class 1 MRI paradigm.

Integrons are natural cloning and expression systems that incorporate open reading frames by using site-specific recombination and convert them to functional genes (for reviews see references 14 and 36). Multiresistant integrons (MRIs) were first discovered through characterization of the rapid dissemination of multiple-antibiotic resistance among gram-negative clinical isolates. More recently, the discovery of another type of integron, the superintegron (SI), has expanded the function beyond antibiotic resistance to a broader role in the adaptive capacity of the host and has shown that integron distribution is not limited to clinical strains. The first SI was discovered in the Vibrio cholerae genome (26). Since then, SIs have been found in the genomes of diverse proteobacterial species and characterized (19, 33, 34, 41), and integron-like structures have been amplified from soil DNA samples (18, 29, 30, 38). In contrast to the MRI functional platforms, which are carried by mobile elements (plasmids, transposons), the SI platforms seem to be sedentary, as attested to by their coevolution with their host genomes (33).

The integron platform consists of an integrase gene (intI) belonging to the tyrosine recombinase family (31) and a primary recombination site, attI. The integrase mediates recombination between the attI site and a target recombination sequence called an attC site (or 59-base element). The attC site is usually found associated with a single open reading frame in a circularized structure termed a gene cassette (15, 32, 39, 40). Insertion of the gene cassette at the attI site, which is located downstream of a resident promoter, Pc, internal to the intI gene, drives expression of the encoded proteins (22).

The development of multiple-antibiotic resistance can often be traced to the stockpiling of resistance loci within integrons to create MRIs, and for this reason integrons have long been recognized as the elements responsible for the evolution of multidrug resistance in gram-negative pathogens during the antibiotic era. Currently, more than 70 different antibiotic resistance genes have been characterized in integrons (11).

Five classes of MRIs have been reported based on the divergence of their integrase genes (37). The class 1 integron platform is the most ubiquitous among multidrug-resistant bacterial populations and is often found associated with the Tn21 transposon family (13). Cassette recombination activity has been demonstrated for the class 1 and class 3 integrases (14, 23). All natural isolates with class 2 integrons identified to date harbor an integrase with a premature stop codon at position 179, which yields a truncated, nonfunctional protein. However, mutation of the stop codon into a glutamate codon (intI2*179E) was shown to restore the IntI recombination activity (17).

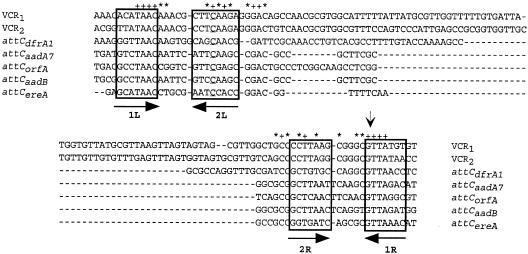

Most of the MRI attC sites identified to date exhibit little homology. Their lengths (57 to 141 bp) and sequences vary considerably, and their sequence similarities are primarily restricted to the boundaries, which correspond to the inverse core site or 1L sequence (RYYYAAC) and the core site or 1R sequence (G↓TTRRRY, where R is a purine, Y is a pyrimidine, and the arrow indicates a recombination point) (Fig. 1) (8, 39). The integrase seems to catalyze only a single-strand exchange, which occurs either between the G and TT in the right core site or between the AA and C on the complementary strand (16, 39).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of VCR1, VCR2, attCdfrA1, attCaadA7, attCorfA, attCaadB, and attCereA site sequences. The 1L, 2L, 2R, and 1R sequences are enclosed in boxes. Plus signs and asterisks indicate conserved nucleotides found at all sites and at at least four of the sites examined, respectively. The vertical arrow indicates the recombination point in the 1R sequence.

Two putative integrase binding sites, called LH and RH simple sites, were defined based on the known structural features of other tyrosine recombinase recombination sites and were found to correspond to conserved sequences in several resistance cassette attC sites (39). The LH simple site is composed of the 1L sequence and a second sequence called 2L, which is related to the 1R consensus sequence (8, 39). The 1L and 2L sequences are separated by a 5-bp spacer, and it has been proposed that the integrase binds to the LH simple site either as two monomers or as a dimer (8). The RH simple site is similarly defined, and it includes the 1R sequence and a second sequence called 2R, which is related to the 1L consensus sequence. As observed for the LH simple site, the 1R and 2R sequences have a 5- to 6-bp spacer between them (Fig. 1).

In contrast, the cassette attC sites are extremely homogeneous within each SI cassette array. For example, in the V. cholerae N16961 SI, 149 of the 179 cassettes carry attC sites that are 123 bp long and differ from each other by less than 5% (34). The sites are so conserved that they were originally identified as repeated sequences termed V. cholerae repeats (VCRs) (2). The structural differences, together with the phylogenetic relationships, led to the proposal that MRIs evolved from SIs through the entrapment of intI genes and the cognate attI sites by mobile DNA elements and that resistance cassettes were later integrated from diverse SI cassette pools (33).

We recently analyzed and compared 219 attC sites from different Vibrio SI cassettes (called Vibrio species repeats [VXRs]). As observed for the resistance cassette attC sites, we found that they all had the potential to form a stem-loop structure. This putative structure starts four nucleotides upstream of 1L sequence and hybridizes with a sequence ending four nucleotides downstream of the 1R sequence. Comparison of the VXR sequences to the 2L and 2R consensus sequences described for the attC sites (39) showed that, outside the conservation of TCAA in the 2L consensus sequence and the conservation of TTA in the 2R consensus sequence, symmetry rather than the primary sequence was important (34).

In contrast to the integrases of the same family that have been studied (λ, Cre, FLP, XerC/XerD, FimB/FimE), the integrases from integrons are able to recombine distantly related DNA sequences. This finding is reflected in the great structural disparity that is observed between the attC sites of different cassettes. The recombination activities of several SI integrases have been studied to different extents. The cassette deletion and integration activities of IntISon from Shewanella oneidensis and IntINeu from Nitrosomonas europaea, which are associated with a small number of cassettes or no cassettes at all, have been demonstrated but not quantified (10, 21). In addition, integrative recombination (attI-×-attC sites) catalyzed by the Pseudomonas stutzeri SI integrase (IntIPstQ) has been demonstrated (19), while the deletion activity through attCaadB-×-VCR recombination was previously established for the V. cholerae SI integrase, VchIntIA (formerly IntI4) (33). Except for VchIntIA, all of these integrases were shown to be able to catalyze cointegrate formation through recombination of the cognate attI sites and at least one resistance cassette attC site.

As mentioned above, it has been observed that within each SI the cassette attC sites are extremely homogeneous and species specific, whereas the MRI cassette attC sites are highly variable in length and sequence (Fig. 1). One hypothesis to explain these structural differences is that the recombination activities of the MRI and SI integrases differ. Indeed, one can imagine that the narrow range of structural heterogeneity shown by the SI cassette attC sites directly reflects the recognition spectrum of VchIntIA. We addressed this question in this work through a comparative study of the recombination activities of IntI1, the class 1 MRI integrase, and VchIntIA, the V. cholerae SI integrase. For technical reasons we could not use available assays (23) and therefore developed novel assays to measure the frequencies of cassette deletion through attC-×-attC site recombination and cassette integration at the cognate attI sites. Using our cassette deletion assay, we showed that the structural range of the attC sites recombined was narrower for VchIntIA than for IntI1. We were able to map several determinants of attC recognition by VchIntIA by introducing mutations at conserved positions within the VCR structure, the natural VchIntIA substrate. Using our cointegration assay, we established that in E. coli, attI1-×-VCR recombination catalyzed by IntI1 is far more efficient than attIVch-×-VCR recombination catalyzed by VchIntIA. We also tested cointegrate formation using the same substrates and both integrases in V. cholerae. We observed that attIVch-×-VCR recombination by VchIntIA was 2,000-fold greater than the recombination measured in E. coli, while the attI1-×-VCR recombination by IntI1 was identical to that measured in E. coli. Taken together, our results indicate that the substrate recognition and recombination reactions of VchIntIA might differ from the class 1 MRI paradigm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Bacteria were routinely cultured in Luria broth (LB) or on LB agar supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). When trimethoprim (87 μg/ml) was used, selection was performed by growth on Mueller-Hinton media. Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d thiogalactopyranoside) were used at final concentrations of 0.3 and 0.5 mM, respectively. All the strains used in this work are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strains | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Basic strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80lacZ′ΔM15) ΔargF hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Laboratory collection |

| β2163 | MG1655::Δdap::(erm, pir) RP4-2-Tc::Mu (Kmr) | Demarre et al., in press |

| Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hdsRMS-mcrBC) φ80 lacZΔM15 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| N 16961Sm | Smr derivative of V. cholerae El Tor N16961 | J. J. Mekalanos |

| Strains constructed for integration assays | ||

| E. coli strains | ||

| ω216 | β2163/p1881(VCR2/1) | This study |

| ω219 | DH5α/p929(attI1) | This study |

| ω220 | DH5α/p929(attI1)/p112(intI1) | This study |

| ω221 | DH5α/p755(attIVch) | This study |

| ω222 | DH5α/p755(attIVch)/p222(VchintIA) | This study |

| ω3550 | DH5α/p755(attIVch)/p112(intI1) | This study |

| ω3551 | DH5α/p929(attI1)/p222(VchintIA) | This study |

| ω3554 | DH5α/p3552(attI1pir116)/p112(intI1) | This study |

| ω3557 | DH5α/p3553(attIVchpir116)/p222(VchintIA) | This study |

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| ω212 | V. cholerae/p929(attI1) | This study |

| ω213 | V. cholerae/p755(attIVch) | This study |

| ω214 | V. cholerae/p929(attI1)/p112(intI1) | This study |

| ω215 | V. cholerae/p755(attIVch)/p222(VchintIA) | This study |

| ω3530 | V. cholerae/p929(attI1)/p222(VchintIA) | This study |

| ω3531 | V. cholerae/p755(attIVch)/p112(intI1) | This study |

| ω3585 | V. cholerae/p3552(attI1pir116)/p112(intI1) | This study |

| ω3586 | V. cholerae/p3553(attIVchpir116)/p222(VchintIA) | This study |

PCR procedures.

PCR were performed in 50-μl mixtures by using PCR Reddy mix (Abgene, Epsom, United Kingdom) and by following the manufacturer's instructions. The primers were obtained from Genset (Evry, France) and are listed in Table 2. The conditions used for amplification were as follows: 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 to 360 s (depending on the expected product size). The sequence of each cloned PCR product used in the different constructions described in this work was verified. Sequencing was performed by MWG-Biotech AG (Ebersberg, Germany) or with a Pharmacia 4×4 sequencing system.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for the different constructs

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 2A | GCCGAATTCAGATCTGGTTATAACAAACGCCTCAAGAGGG |

| 2B | GCGGATCCGCTCTCATGATATCTCCAAATACC |

| 2A2 | GCCGAATTCAGATCTATCGCTAACAAACGCCTCAAGAGGG |

| 2A4 | GCCGAATTCAGATCTGGTTACAACAAACGCCTCAAGAGGG |

| 38/1 | CAGGATATCGTAATCTCTTGCTCTGAAAACG |

| 38/2 | CAGGATATCAGCTTCACGCTGCCGCAAGCA |

| AADA7.1 | GATCTGGTTATAACAATTCATTCAAGCCGACGCCGCTTCGCGGCGCGGCTTAATTCAAGCGTTAGATGGGATCCT |

| AADA7.2 | CTAGAGGATCCCATCTAACGCTTGAATTAAGCCGCGCCGCGAAGCGGCGTCGGCTTGAATGAATTGTTATAACCA |

| aadB-1 | CGGAATTCAGATCTTGCGGCCTAACAATTCGTCCAAGCCGACGCCGCTTCGCGGCGCGGCTT |

| aadB-2 | CGCGGATCCATCTAACACCTGAGTTAAGCCGCGCCGCGAAGCGGCGTCGGCTT |

| aadB-3 | CGCGGATCCAATTGTGCGGCCTAACGCCCGCCTAAGGGGCTGACAACGCA |

| aadB-4 | CGGAATTCTGCGGCCTAACAATTCGTCCAAGCCGACGCCGCTTCGCGGCGCGGC |

| aadB-5 | CGCGGATCCAATTGGGTTATAACACCTGAGTTAAGCCGCGCCGCGAAGCGGCGTCGGCTT |

| ATT4A | GAATTCGTCAAGAGGCTATACAGAC |

| ATT4B | GGATCCTTCAGAACCTTGTGCGTG |

| ATTI1.1 | GCGAATTCGGCTTGTTATGACTGTTTTTTTGTAC |

| ATTI1.2 | GGATCCTGTTGGTCACGATGCTGTAC |

| C1B | GCGGATCCAATTGGGTTATAACGCCCGCTTAAGG |

| C1B2 | GCGGATCCAATTGATCGCTAACGCCCGCTTAAGG |

| C1B3 | GCGGATCCAATTGGGTTACAACGCCCGCTTAAGGGG |

| C-ACL | AAACTGCAGTACCTAACGTTCGCCTAAGGGGCTGACAAC |

| C-BSI | AAACTGCAGTACCGTACGCCCGCCTAAGGGGCTG |

| C-BSS | AAACTGCAGTACCGCGCGCCCGCCTAAGGGGCTG |

| dfrA1I | CGGAATTCAGATCTAAAAGGGTTAACAAGTGGCAGCAACGGATTCGCAAACCTGTCACGCCTTTTGTACCAAAAGCCGCGC |

| dfrA1II | GCGGATCCTGACGCCTAACGCCTGGCACAGCGGATCGCAAACCTGGCGCGGCTTTTGGTACAAAAGGCGTGACAGG |

| dfrA1III | GGCGGATCCAATTGAGGTTAACGCCCGCCTAAGGGGCT |

| ereA1a | CGCGGATCCAATTGAGCATAACGCCCGCCTAAGGGGCTGAC |

| ereA1b | GCGAATTCAGATCTGAGCATAACCTGCGAATCCACCGGACGGTTTTCAACCGCC |

| ereA1c | GCGGGATCCATGTTTAACGCGCTGATCACCGGCGGTTGAAAACCGTCCGGTGGATTC |

| FD-40 | CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC |

| I-ACL | TTCGAAAGATCTGGTTATAACGTTCGCCTCAAGAGGGACTGTCA |

| ICVR2A-G | GGAATTCAGATCTGTTATAACGCCTCAAG |

| I-SNA | TTCGAAAGATCTGGTTACGTAAAACGCCTCAAGAGGGACTGT |

| I-STU | TTCGAAAGATCTAGGCCTAACAAACGCCTCAAGAGGGA |

| IOA | GCCGAATTCGGCAAGCGGCATGCATTTACG |

| IOB | GCGGATCCAGATCTGCTGTCAAACCAGATCAATTCGCG |

| orfA4 | GAATTCAGATCTATGACGCCTAACCGGTCGTTCGAGCGGACTGCCCTCGGCAAGCCTCGGTCAGCCGCTCAACTTCAACGTTACGTGGATCC |

| orfA5 | CGCGGATCCACGTAACGTTGAAGTTGAGCGGCTGACCGAGGCTTGCCGAGGGCAGTCCGCTCGAA |

| orfA6 | CGGAATTCAGATCTATGACGCCTAACCGGTCGTTCGAGCGGACTGCCCTCGGCAAGCCTCGGTCAGCC |

| orfA7 | GCGGATCCATGACGCCTAACGTTGAAGTTGAGCGGCTGACCGAGGCTTGCCGAGGGCAG |

| orfA8 | CTCGAATTCATGACGCCTAACCGGTCGTT |

| orfA9 | CCCGGATCCCAATTGGGTTATAACGTTGAAGTTGAGCGGCT |

| MRV-D21 | TTCTGCTGACGCACCGGTG |

| pirBHI | CGCGGATCCGTTGCTAAAACATGAGATAAAAATTG |

| pirXbII | CCGAGCTCTAGATTACCCCTTAGCTTTTTTGGGAG |

| PLAC1 | CGCGAATTCAATGTGAGTTGACTCACTCATTAG |

| PLAC2 | CGCGGATCCCAATTGAGATCTGATATCGAGCTCTGAAATTGTTATCCGCTCACAATT |

| PNOTΔ | GATAGAATTCTGGGGTGCCTAATGAGTGAG |

| PTRC1 | CGCGAATTCCTGAAATGAGCTGTTGACAATTA |

| REV-48 | AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGA |

| VCHINT1 | CGAATTCTGTACAAATAACCAGTTAAATAT |

| VCHINT2 | CGCGGATCCGTGTTATTAAGAAAGGG |

| VCR2C-T | CCCAAGCTTAAATACCTAACACCCGC |

| VCR2RI | CGGAATTCCTTACGGTTATAACAAACGCCTCAAGA |

| WT-CS | AAACTGCAGTACCTAACGCCCGCCTAAG |

| WT-ICS | TTCGAAAGATCTGGTTATAACAAACGCCTCAAG |

Deletion assay. (i) Construction of the lacIq cassette substrates.

The lacIq synthetic cassette used as a deletion reporter was composed of a lacIq gene inserted between two wild-type VCRs, VCR1 and VCR2 from the V. cholerae 569B SI (2), and was constructed as described below.

Each independent element (VCR1, lacIq, or VCR2) was assembled by PCR. VCR1 was amplified with the REV-48 and C1B primers from pSU38::ORF1-cat (26), digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and cloned into pSU18Δ with the same restriction enzymes to obtain plasmid p452 (Table 3). pSU18Δ is pSU18 with the EcoRI/NheI (233-bp) fragment that carries the 3′ end of lacI and the lacZ promoter deleted. The deleted region is replaced by the cohesive complementary linkers L1 (pCTAGTGATATCG) and L2 (pAATTCGATATCA), which carries an EcoRV restriction site. The lacIq gene was amplified with primers IQA and IQB by using pTRC99A as the template. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into pSU18Δ digested by the same enzymes, which gave rise to pSU18Δ::lacIq (Table 3). VCR2 was amplified with primers 2A and 2B by using pSU38::ORF1-cat as the template, digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and cloned into pSU18Δ, resulting in plasmid p453 (Table 3). The final lacIq synthetic cassette was assembled as follows. The EcoRI-HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq was cloned into p452 digested by MfeI and HindIII, yielding p457 (pSU18Δ::VCR1-lacIq). Finally, the BglII-HindIII VCR2 fragment from p453 was ligated to p457 digested by BglII and HindIII to generate p674 (pSU18Δ::VCR1-lacIq-VCR2) (Table 3). The same strategy was adapted for construction of the other synthetic cassettes tested. The corresponding construction intermediates and final constructs are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Plasmids used in the deletion assay

| Plasmid | Descriptiona |

|---|---|

| pSU18 | oriP15A Cmr (3) |

| pSU18Δ | Deletion of the EcoRI/NheI (233-bp) fragment of pSU18 carrying the 3′ end of lacI and the lacZ promoter and replacement by an EcoRV restriction site (see text) |

| pMBG18R | oriColE1 Apr, mp18 MCS containing additional in-frame BglII and MfeI sites (Demarre et al., in press). |

| pNOT218 | oriColE1 Apr (33) |

| pBAD18 | oriColE1 Apr, expression vector (12) |

| pSU38::ORF1-cat | pSU38::VCR1-ΔORF1::cat-VCR2 (26) |

| pTRC99A | oriColE1 Apr, expression vector (Pharmacia) |

| pTZ18R::dfrB1 | oriColE1dfrB1 Tpr Apr (25) |

| p734 | intI1 carrying EcoRI/HindIII fragment from p112 (33) cloned in pBAD18 |

| p995 | VchintIA EcoRI/SphI fragment from pVC3 (33) cloned in pBAD18 |

| Synthetic cassette assembly | |

| pSU18Δ::lacIq | 1,254-bp EcoRI/BamHI lacIq PCR fragment (IQA and IQB) amplified from pTRC99A in pSU18Δ |

| p452 | 200-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR1 PCR fragment (REV-48 and C1B) amplified from pSU38::ORF1-cat cloned in EcoRI/BamHI-digested pSU18Δ |

| p453 | 200-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (2A and 2B) amplified from pSU38::ORF1-cat in EcoRI/BamHI-digested pSU18Δ |

| p457 | 1,275-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p452 digested by MfeI/HindIII; pSU18Δ::VCR1-lacIq |

| p470 | 200-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 fragment from p453 in pSU18Δ::lacIq |

| p674b | 188-bp BglII/HindIII VCR2 fragment from p453 in p457; pSU18Δ::VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 |

| p1011 | 79-bp BglII/XbaI attCaadA7 fragment obtained by annealing between the AADA7.1 and AADA7.2 primers, filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pMBG18R |

| p1182b | 99-bp BglII/HindIII attCaadA7 fragment from p1011 in p674; pSU18Δ::VCR1-lacIq-attCaadA7 |

| p2899 | 86-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCorfA fragment obtained by annealing between the orfA4 and orfA5 primers, filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pSU18Δ |

| p2969 | 153-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (VCR2RI and orfA3) amplified from p453 in pSU18Δ |

| p2978 | 148-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (VCR2RI and dfrA1III) amplified from p453 in pSU18Δ |

| p2981 | 116-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCdfrA1 fragment obtained by annealing between the dfrA1I and dfrA1II primers, filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pSU18Δ |

| p2984 | 91-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCorfA fragment obtained by annealing between the orfA6 and orfA7 primers, filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pSU18Δ |

| p3012 | 148-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (VCR2RI and ereA1a) amplified from p453 in pSU18Δ |

| p3015 | 73-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCereA fragment obtained by annealing between the ereA1b and ereA1c primers, filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pSU18Δ |

| p3019 | 88-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCorfA PCR fragment (orfA8 and orfA9) amplified from p2899 in pSU18Δ |

| p3028 | 166-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 fragment from p453 in pSU18Δ |

| p3074 | 1,275-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p3012 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p3075 | 1,275-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p3019 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p3076 | 1,275-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p2969 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p3077 | 1,275-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p2978 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p3078b | 97-bp BglII/HindIII attCereA fragment from p3015 in p3074; pSU18Δ::VCR2-lacIq-attCereA |

| p3079b | 190-bp BglII/HindIII VCR2 fragment from p3028 in p3075; pSU18Δ::attCorfA-lacIq-VCR2 |

| p3080b | 115-bp BglII/HindIII attCorfA fragment from p2984 in p3076; pSU18Δ::VCR2-lacIq-attCorfA |

| p3113b | 140-bp BglII/HindIII attCdfrA1 fragment from p2981 in p3077; pSU18Δ::VCR2-lacIq-attCdfrA1 |

| p3212 | 76-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCaadB fragment obtained by annealing between the aadB-1 and aadB-2 primers filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pSU18Δ |

| p3214 | 151-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (VCR2RI and aadB-3) amplified from p453 in pSU18Δ |

| p3230 | 1,275-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p3214 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p3233 | 77-bp EcoRI/BamHI attCaadB fragment obtained by annealing between the aadB-4 and aadB-5 primers, filling with the Pfu DNA polymerase, digestion, and cloning in pSU18Δ |

| p3235b | 100-bp BglII/HindIII attCaadB fragment from p3212 in p3230; pSU18Δ::VCR2-lacIq-attCaadB |

| p3245 | 1275-bp EcoRI/HindIII laclq fragment from pSU18Δ::lacIq in p3233 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p3249b | 99-bp BglII/HindIII attCaadA7 fragment from p1182 in p3245; pSU18Δ::attCaadB-lacIq-attCaadA7 |

| VCR mutant construction | |

| p440 | 214-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR1 PCR fragment (REV-48 and C1B3) from pSU38::ORF1-cat in pSU18Δ |

| p441 | 214-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR1 PCR fragment (REV-48/C1B2) amplified from pSU38::ORF1-cat in pSU18Δ |

| p454 | 168-bp BglII/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (2A2 and 2B) amplified from p453 in pSU18Δ |

| p471 | 168-bp BglII/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (2A2 and 2B) from p454 in pSU18Δ::lacIq |

| p675b | 162-bp BglII/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (2A4 and 2B) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p735b | 168-bp BglII/BamHI VCR2 PCR fragment (2A2 and 2B) from p454 in p457 |

| p745b | 1,425-bp EcoRI/BamHI lacIq-VCR2 PCR fragment (2A2 and 2B) from p471 in p441 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p746b | 1,425-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq-VCR2 PCR fragment from p470 in p440 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| p1046b | 141-bp BglII/PstI VCR2 PCR fragment (I-STU and WT-CS) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1047b | 141-bp BglII/PstI VCR2 PCR fragment (I-SNA and WT-CS) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1048b | 141-bp BglII/PstI VCR2 PCR fragment (I-ACL and WT-CS) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1049b | 141-bp BglII/PstI VCR2 PCR fragment (WT-ICS and C-BSS) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1050b | 141-bp BglII/PstI VCR2 PCR fragment (WT-ICS and C-BSI) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1051b | 141-bp BglII/PstI VCR2 PCR fragment (WT-ICS and C-ACL) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1653b | 148-bp BglII/HindIII VCR2 PCR fragment (REV-48 and VCR2C-T) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p1676b | 187-bp BglII/HindIII VCR2 PCR fragment (IVCR2A-G and FD-40) amplified from p453 in p457 |

| p2331b | 1,425-bp EcoRI/HindIII lacIq-VCR2 from p470 in p441 digested by MfeI/HindIII |

| Deletion reporter construction | |

| pNOT::Ptac | 109-bp Ptac promoter PCR fragment (PLAC1 and PLAC2) in pNOT218 |

| pNOTΔ::Ptac | Deletion of the lacZ promoter by inverse PCR (PNOTΔ and PTRC1), EcoRI digestion, and religation |

| pNOTΔ::Ptac-dfrB1 | 318-bp SacI and BamHI fragment from pTZ18R::dfrB1 in pNOTΔ::Ptac |

The numbers in parentheses are reference numbers.

Plasmid corresponding to a final construct, synthetic cassette, and mutant, which have been tested in the deletion assay.

Mutated VCR1 and VCR2 derivatives were assembled by PCR by using the different primers listed in Table 2, and the corresponding lacIq synthetic cassettes were constructed by using the steps described above for the assembly of the VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 cassette. The corresponding construction intermediates and final constructs are listed in Table 3.

(ii) Construction of plasmids expressing the integrases.

Both integrases were cloned in pBAD18 in order to trigger their expression in the presence of arabinose. The VchintIA-carrying fragment was amplified by using the VCHINT1 and VCHINT2 primers, digested with EcoRI and SphI, and cloned into pBAD18, creating p995. The EcoRI-HindIII fragment from p112, carrying intI1, was cloned into pBAD18, yielding p734. The p995 and p734 inserts were sequenced to verify the absence of mutations in the intI genes.

(iii) Deletion assay procedure.

Strains which contained plasmids p734 (intI1) (Table 3) and p995 (VchintIA) (Table 3) were transformed with the p674 plasmid that carried the synthetic VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 reporter cassette and with plasmids carrying the different synthetic cassettes or carrying mutants of the VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 reporter cassette (Table 3). Induction of integrase expression was achieved by addition of l-arabinose at a final concentration of 0.02% to bacterial cultures at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8. After overnight growth under these conditions, plasmids were extracted from these strains and transformed into strain ω42. ω42 was the reporter strain used to detect lacIq cassette deletion. This strain harbored pNOTΔ::Ptac-dfrB1, a plasmid which carried the dfrB1 gene, conferring trimethoprim resistance, under the control of the Ptac promoter. LacI repressed the Ptac promoter and thus abolished dfrB1 expression. Consequently, ω42 transformants carrying a plasmid that had lost the lacIq gene cassette were able to grow on Mueller-Hinton medium containing trimethoprim, and the deletion frequency was measured by determining the ratio of trimethoprim- and chloramphenicol-resistant (Tpr Cmr) clones to Cmr clones. The same protocol was used to test the deletion aptitude of all the synthetic cassettes and VCR mutants. lacI deletion was checked by PCR (with primers MRVD21 and FD-40) in 10 Tpr clones for each of the three independent trials performed for each construction, and one PCR product was sequenced in order to map the recombination point. The background frequency was established by using an empty pBAD18 plasmid in place of p734 and p995 under the same conditions, and the maximum value was found to be 5 × 10−5 (data not shown).

Integration assay with E. coli.

VCR2/1, which corresponded to the attC site carried by the putative circularized lacIq synthetic cassette produced by the deletion reaction, was constructed by PCR amplification with primers C1B and 2A. After EcoRI-BamHI digestion VCR2/1 was cloned into pSW23T (Cmr), an R6K plasmid derivative with a conditional origin of replication that was controlled by the π protein (G. Demarre et al., Res. Microbiol., in press), resulting in p1881 (Table 4). pSW23T did not encode the π protein, and replication of this plasmid was possible only in a strain carrying the pir gene. β2163, an E. coli pir+ strain, was transformed with p1881, creating strain ω216 (Table 1). ω220, a DH5α derivative carrying p929 (attI1, kanamycin resistant [Kmr]) and p112 (intI1, ampicillin resistant [Apr]), and ω222, a DH5α derivative carrying p755 (attIVch, Kmr) and p222 (VchintIA, Apr), were constructed by successive transformations. Two other DH5α derivatives, ω3550 carrying p929 (attI1, Kmr) and p222 (VchintIA, Apr) and ω3551 carrying p755 (attIVch, Kmr) and p112 (intI1, Apr), were also constructed by successive transformations.

TABLE 4.

Plasmids used in the integration assay

| Plasmid | Descriptiona |

|---|---|

| pSW23T | oriT-RP4 oriV-R6K cat Cmr (Demarre et al., in press). |

| pTRC99A | AproriColE1, expression vector (Pharmacia) |

| pSU38Δ | 2,622 bp of pSU38 (3) amplified by PCR (38/1 and 38/2), digested by EcoRV, and religated |

| p112 | pTRC99A::intI1 (33) |

| p222 | 1,093-bp EcoRI/BamHI VchintIA PCR fragment (VCHINT1 and VCHINT2) amplified from V. cholerae 569B in pTRC99A |

| p755 | 222-bp EcoRI/BamHI attIVch PCR fragment (ATT4A and ATT4B) amplified from V. cholerae 569B in pSU38Δ |

| p929 | 182-bp EcoRI/BamHI attI1 PCR fragment (ATTI1.1 and ATTI1.2) amplified from R388 (24) in pSU38Δ |

| p1177 | 1,008-bp BamHI/XbaI PCR fragment (pirBHI and pirXbII) amplified from BW19610 (28) in pSB118 (4) digested by BamHI/XbaI. |

| p1881 | 159-bp EcoRI/BamHI VCR2/1 PCR fragment (C1B and 2A) from p452 (Table 3) in pSW23T |

| p3552 | 1,049-bp EcoRI pir116 fragment from p1177 in p929 digested by EcoRI |

| p3553 | 1,049-bp EcoRI pir116 fragment from p1177 in p755 digested by EcoRI |

The numbers in parentheses are reference numbers.

Integration was assayed by cointegrate formation after conjugative delivery of the attC site-carrying vector. Briefly, strain ω216 was grown overnight at 37°C in LB containing chloramphenicol and DAP. ω220 and ω222 were grown in the same conditions in LB containing ampicillin and kanamycin. Overnight cultures were diluted 1,000-fold in fresh LB (containing DAP for ω216), and integrase expression was induced by addition of IPTG. Cultures were grown until the optical density at 600 nm was 0.4 and mixed, and conjugation was performed overnight. Conjugation between donor strain ω216 (Δdap) and the pir mutant recipient, either ω220 or ω222, allowed delivery of p1881 into recombination-proficient recipient strains. p1881 could be maintained in the recipient only through recombination with an autonomous replicon, either the chromosome, p929, or p755, via integrase-mediated recombination between the attI (attI1 or attIVch) site and VCR2/1. Transconjugants were selected on agar containing chloramphenicol and kanamycin. The cointegration frequency was calculated by determining the ratio of Cmr Kmr clones to Kmr clones. Ten clones from each experiment were analyzed by PCR in order to establish the frequency of cointegrate formation by attI-×-VCR2/1 recombination. Background values were established by using control strains constructed by successive transformation of DH5α by pTRC99A and either p929 or p755. In both cases, Cmr Kmr transconjugants were found at a frequency of 1 × 10−7, but further analysis of 30 such clones by PCR showed that none of them corresponded to cointegrate formation through attI-×-VCR recombination, which gave a cointegrate detection limit of 3 × 10−9.

The frequencies of E. coli-E. coli conjugative transfer were established by using strains ω3554 and ω3557, which carried a pir gene, which allowed replication of the pSW derivative p1881, as the recipients.

Integration assay with V. cholerae.

The design of the integration assay with V. cholerae was identical to the design of the integration assay with E. coli. Plasmids p929 and p755 were independently introduced into V. cholerae El Tor N16961Sm by electroporation (5) to create strains ω212 and ω213, respectively. Plasmid p112 was then introduced by electroporation into strains ω212 and ω213 to create strains ω214 and ω3531, respectively (Table 1). Plasmid p222 was transformed into the ω213 and ω212 strains to create strains ω215 and ω3530, respectively (Table 1). Conjugation between the donor strain ω216 (Δdap) and the different V. cholerae recipients, which were all pir mutants, and cointegration frequencies were determined as described above for E. coli. Background values were established by using control strains constructed by successive transformation of V. cholerae ω212 and ω213 by pTRC99A. In both cases, Cmr Kmr transconjugants were found at a frequency of 1 × 10−7.

The frequencies of E. coli-V. cholerae conjugative transfer were established by using strains ω3585 and ω3586, which carried a pir gene, which allowed replication of the pSW derivative p1881, as the recipients.

RESULTS

Comparative activities of IntI1 and VchIntIA on different synthetic cassettes.

The deletion assay developed for this study was based on the loss of a reporter gene (lacIq) that was assembled as a synthetic integron gene cassette carried on a plasmid. In this way, each of the two surrounding attC sites could be independently engineered. Deletion of the engineered cassettes was assayed in strains expressing either the integrase IntI1 (p734) or VchIntIA (p995) from a compatible plasmid. Integrase-mediated recombination led to deletion of the lacIq gene through recombination between the two attC sites tested. Loss of the lacIq gene was measured by transformation of reporter strain ω42 (lacI mutant) with the plasmid population in the first strain. Reporter strain ω42 harbored a plasmid carrying the dfrB1 gene, encoding a dihydrofolate reductase that was resistant to trimethoprim, under the control of the LacI-repressible Ptac promoter. After transformation under the appropriate conditions (which allowed transformation by at most a single plasmid), frequencies of deletion were established by determining the ratio of Tpr transformants to ω42 transformants (see Materials and Methods).

Using this test, we established the deletion frequencies for the different synthetic cassettes listed in Table 5. The data showed that the frequency of recombination catalyzed by IntI1 varied from 10−5 to 10−2, while the frequency of recombination catalyzed by VchIntIA varied from <10−5 to 4.3 × 10−3. The results obtained with the two reciprocal constructs, VCR2-lacIq-attCorfA and attCorfA-lacIq-VCR2, suggest that in our synthetic cassette deletion assay, there was no notable differential use of the left and right recombination sites by the integrases. The threefold difference observed with IntI1 might have been a consequence of the sequence difference in the variable parts of the 1R1 and 2L2 sequences in the two reciprocal constructions, since the corresponding sequences may have been less recombination proficient in one of the alternate constructs. Interestingly, the recombination rates of the different constructs varied in the same range for the two integrases, and the average rate for VchIntIA was 3- to 10-fold less than that established for IntI1. However, we found two notable exceptions, VCR2-lacIq-attCorfA and VCR2-lacIq-attCereA substrate recombination. Indeed, in these cases, the deletion frequencies obtained with IntI1 were 300- and 100-fold greater, respectively, than those obtained with VchIntIA.

TABLE 5.

Deletion frequencies

| Synthetic cassette | Synthetic cassette deletion frequencya

|

|

|---|---|---|

| IntI1 | VchIntIA | |

| VCRi-lacIq-VCR2 (p674) | (1 ± 0.4) × 10−2 | (1 ± 0.5) × 10−3 |

| VCR1-lacIq-attCaadA7 (p1182) | (1 ± 0.3) × 10−3 | (3 ± 1.1) × 10−4 |

| VCR2-lacIq-attCaadB (p3235) | (5 ± 3) × 10−3 | (6.5 ± 1) × 10−4 |

| attCaadB-lacIq-attCaadA7 (p3249) | (2.3 ± 0.6) × 10−2 | (4.3 ± 4) × 10−3 |

| VCR2-lacIq-attCorfA (p3080) | (6.3 ± 2) × 10−3 | (2.1 ± 1) × 10−5 |

| attCorfA-lacIq-VCR2 (p3079) | (1.9 ± 0.5) × 10−3 | (2.1 ± 0.1) × 10−5 |

| VCR2-lacIq-attCereA (p3078) | (2.7 ± 1.3) × 10−3 | <1.8 × 10−6 |

| VCR2-lacIq-attCdfrA1 (p3113) | (6 ± 1) × 10−6 | <7 × 10−7 |

Average ± standard deviation for three independent trials.

Effects of mutations introduced into the regions of the VCR overlapping the 1R and 1L sequences.

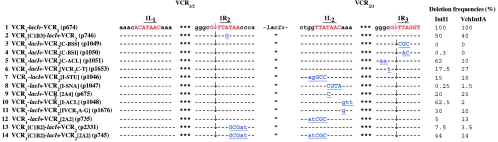

Comparison of the different attC sites tested in the assay showed that all sites shared the 1L and 1R consensus sequence defined previously (6, 39) and that conservation extended to the two nucleotides (AA) immediately downstream of the 1L sequence and to the GC immediately upstream of the 1R sequence, with only a few exceptions (Fig. 1). In order to determine whether this sequence conservation was responsible for the difference in recombination activities between IntI1 and VchIntIA, we introduced mutations at different conserved positions and tested their effects on IntI1 and VchIntIA deletion activities as described above, by transformation of the dfrB1 reporter strain. These mutations were introduced into the synthetic VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 cassette (Fig. 2). We also tested the effect of the abolition and restoration of 1R2/1L2 complementarity (Fig. 2). The relative effects of the different mutations on the deletion frequencies catalyzed by both integrases are shown in Fig. 2. We found that, as previously seen for IntI1 activity (16, 39), mutation at the second to fourth positions in the 1R3 sequence, from GTTAGGT to GCGCGGT, completely abolished cassette deletion catalyzed by either integrase (Fig. 2, lane 3). Interestingly, mutation at the third and fourth positions of the 1R3 sequence, from GTTAGGT to GTACGGT, was sufficient to totally abolish VchIntIA activity and to reduce IntI1 activity over 300-fold (Fig. 2, lane 4). A change from A to G at the fourth position in the 1R2 sequence of VCR1, from GTTATAAC to GTTGTAAC, had only minor and identical effects on the deletion frequencies of both integrases (Fig. 2, lane 2).

FIG. 2.

Mutations introduced into the VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 cassettes and recombination properties. 1R and 1L sequences are indicated by red type, and the nucleotides outside the 1R and 1L sequences are indicated by black type. Each individual mutation tested is on a single line and is identified by the designation of the cassette mutant, followed by the designation of the corresponding plasmid in parentheses; mutated bases are indicated by blue type and are underlined. The vertical arrows indicate the recombination points in the 1R sequences. Three asterisks indicate the VCR1 and VCR2 internal sequences of the original cassette. The deletion frequencies are expressed as percentages of the frequency established with the nonmutated VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 synthetic cassette

On the 1L sequence side, the strongest effect was observed with mutations in the most conserved part of the 1L sequence, the TAAC of RYYTAAC. Indeed, a change in the 1L2 sequence of VCR2 from TTATAAC to TTACGTA drastically reduced the cassette deletion frequencies for IntI1 and VchIntIA by 400- and 66-fold, respectively (Fig. 2, lane 8). Replacement of the T in the fourth position by a C, from TTATAAC to TTACAAC, reduced the recombination frequency for both integrases by about fivefold (Fig. 2, lane 9). Mutations introduced into the 1L2 sequence outside the TAAC tetrad (Fig. 2, lanes 7 and 12) lowered the level of recombination 10-fold for both integrases.

To determine the significance of the cassette 1L and 1R complementarity for the deletion activity of IntI1 and VchIntIA, we disrupted the complementarity between the 1R2 cassette tested and the cognate 1L2 sequence by changing the GTTATAACCC sequence to GTTAGCGATC. This change severely reduced the deletion frequencies for both integrases (Fig. 2, lane 13). Moreover, mirror mutations in the 1L2 region (change from TGGTTATAAC to TATCGCTAAC) had a similar effect (Fig. 2, lane 12). A third construct was tested, in which the 1R/1L complementarity was restored by combining the two mutated 1L2 and 1R2 sequences described above in the same synthetic cassette (Fig. 2, lane 14). Interestingly, in the case of IntI1 catalysis, the recombination frequency of this substrate was about one-half the frequency obtained with the nonmutated substrate and between six- and ninefold greater than the frequency obtained with each of the corresponding 1L2 or 1R2 sequence mutants. For VchIntIA catalysis, combining the two complementary mutated 1L2 and 1R2 sequences did not improve the deletion frequency compared to the frequency established with the mutant carrying only the 1L2 sequence mutations.

Mutations at the positions abutting the 1L and 1R sequences which were found to be conserved in all VXRs (34) and in most attC sites but were not fully conserved in the attCorfA, attCereA, and attCaadB sites which were tested in this study (Fig. 1) were also constructed, and their effects on the deletion frequencies catalyzed by both integrases were determined. Two mutants with mutations in the sequence located upstream of the 1R3 sequence were constructed; one involved replacement of GGGCGTTAGGT by GGGTGTTAGGT, and the other involved replacement of GGGCGTTAGGT by GAACGTTAGGT. Both mutations reduced the cassette deletion frequencies catalyzed by the two integrases, but they reduced the frequencies by different degrees (Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 5). Indeed, mimicking the attCorfA sequence through introduction of AA dinucleotides had only a minor effect on IntI1 (1.6-fold reduction), while it reduced the VchIntIA activity 10-fold. On the other hand, replacement of the C abutting the 1R3 sequence led to similar reductions in the IntI1 and VchIntIA activities (five- and fourfold, respectively). In the same way, mutation of the sequence located immediately downstream of the 1L2 sequence from TTATAACAAA to TTATAACGAA or TTATAACGTT hampered deletion of the corresponding cassettes, but to a different extent for each integrase (Fig. 2, lanes 11 and 10). For each cassette tested, analysis of the LacI− clones showed that deletions occurred through VCR-×-VCR recombination, and sequence analysis restricted the location of the recombination point to the 1R sequence GTT or to GT in the VCR1-lacIq-VCR2[C-BSI] cassette assay (Fig. 2, lane 4).

These results show that VchIntIA is generally more sensitive to sequence changes than IntI1 is.

Comparative study of cassette integration at attI1 and attIVch.

The integration assay that we developed was designed in such a way that we could use it with different bacterial species and easily substitute any of the recombination partners, the attI and attC sites, as well as the integrase. The principle is the following: in a host expressing an integron integrase carried on a plasmid and harboring an attI site on a compatible replicon, we delivered the second recombination substrate, an attC site (VCR2/1), by conjugation using a mobilizable suicide vector. The frequency of cointegrate formation through recombination between the suicide vector and the attI-carrying plasmid was determined and taken as the integrase integration activity. We used a suicide vector, pSW23T (Cmr), which carried an RP4 origin of transfer and an R6K oriV origin of replication that absolutely required the π protein. The donor strain carried a chromosomal pir gene and an immobilized RP4. The recipient strain, either E. coli DH5α or V. cholerae N16961Sm, harbored a plasmid carrying the attI site, p929 (attI1) or p755 (attIVch), and a pTRC99A derivative that supplied in trans one of the two integrases (p112 [IntI1] or p222 [VchIntIA]). Each integrase was tested for its ability to catalyze cointegrate formation through recombination between its cognate attI site and VCR2/1 (see Materials and Methods).

To normalize our integration assay for mobilization of p1881, the conjugation frequency of the mobilizable suicide vector was determined in pir+ derivative strains (see Materials and Methods).

Integration assay with E. coli.

The conjugation frequency of p1881 under the conditions used was found to be 2 × 10−2 transconjugant/recipient cell.

In E. coli, the IntI1-catalyzed conjugation-integration frequency between VCR2/1 and the attI1 site measured by the integration assay described above was 2.6 × 10−4. Using an isogenic recipient strain rendered pir+, we determined that the conjugative frequency of p1881 in these conditions was 2 × 10−2 transconjugant/recipient cell. This value allowed us to establish that the recombination frequency was about 1.3 × 10−2 (Table 6). However, the conjugation-recombination frequency obtained by using the attIVch site and VCR2/1 was 1 × 10−7, while the conjugation frequency was also found to be 2 × 10−2 transconjugant/recipient cell. Thus, the corrected recombination frequency was 5 × 10−6, which was 2,600-fold lower than the recombination frequency obtained for attI1-×-VCR2/1 recombination controlled by IntI1. Such a low frequency of recombination might reflect either the nonfunctionality of the attIVch fragment used in the assay or the lack of an accessory element required for full recombination activity. Cross recombination at noncognate attI sites was tested with both integrases in these conditions but was unsuccessful.

TABLE 6.

Integration frequencies obtained with IntI1 and VchIntIA in E. coli and V. cholerae strains

| Participating sites | Integration recombination frequencya

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli

|

V. cholerae

|

|||

| IntI1 | VchIntIA | IntI1 | VchIntIA | |

| attI1 × VCR2/1 | (1.3 ± 0.5) × 10−2 | <3 × 10−9 | (3.7 ± 1.6) × 10−2 | <1 × 10−7 |

| attIVch × VCR2/1 | <3 × 10−9 | (5 ± 2.8) × 10−6 | < 1 × 10−7 | (1 ± 0.3) × 10−2 |

Average±standarddeviationforthreeindependenttrials.

Integration assay with V. cholerae.

We tested the same recombination reactions in V. cholerae. In these conditions, a conjugation-recombination frequency of 1.5 × 10−4 was obtained for attI1-×-VCR2/1 recombination controlled by IntI1, while the E. coli-V. cholerae pir+ conjugation frequency was found to be 4 × 10−3. Thus, the corrected recombination frequency was 3.7 × 10−2 (Table 6). On the other hand, the conjugation-recombination frequency obtained by using the attIVch site and VCR2/1 catalyzed by VchIntIA was 4 × 10−5, which, once corrected by using the conjugation frequency, provided a recombination frequency of 1 × 10−2, about 2,000-fold higher that the recombination frequency measured in E. coli. PCR analysis of selected transconjugants showed that in both cases cointegrate formation occurred through recombination between VCR2/1 and attI1 or between VCR2/1 and attIVch. Also, cross recombination at noncognate attI sites was tested with both integrases under these conditions, but as in E. coli, no integration events were observed.

DISCUSSION

The structural differences between MRIs and SIs led us to compare the dynamic parameters of IntI1 and VchIntIA recombination. We developed two assays in order to be able to independently measure cassette deletion through attC-×-attC recombination on the one hand and cassette integration at the attI site on the other hand. The deletion assay was based on the loss of a lacIq site surrounded by two attC sites in a cassette array configuration (attC-lacIq-attC). Using this assay, we were able to confirm the previously established property of IntI1: catalysis of recombination of a large structural variety of attC sites with reasonable efficiency (9). We noticed, however, that the attCdfrA1 site was recombined by IntI1 at an extremely low frequency (6 × 10−6). We show here that VchIntIA is able to recombine several structurally diverse attC sites with an activity similar to that of IntI1 on identical substrates. However, of the five attC sites tested, which are not related to the VCRs, three were found to be either only poorly recombined (the attCorfA site) or not recombined at all (the attCdfrA1 and attCereA sites) by the V. cholerae integrase. Indeed, the deletion frequency for the VCR2-lacIq-attCorfA substrate with VchIntIA was only 1/500 of the deletion frequency obtained with IntI1, while the deletion frequencies of VCR2-lacIq-attCdfrA1 and VCR2-lacIq-attCereA were either zero or below the background threshold. On the other hand, we established that VchIntIA recombines the attCaadB-lacIq-attCaadA7 synthetic cassette at slightly higher rates than the VCR1-lacIq-VCR2 cassette (Table 5). Thus, even if the range of structural heterogeneity of the attC sites efficiently recombined by VchIntIA is narrower than that of IntI1, it is not sufficiently narrow to explain the presence of almost a unique type of attC site, the VCR, inside the V. cholerae SI.

The alignment of the different attC sites tested in this study shows that their nucleotide sequences are extremely different, except for attCaadB and attCaadA7, which differ at only five positions (Fig. 1). However, it is possible to identify positions that are conserved in at least five of the seven sites (Fig. 1). These conserved positions colocalize with the 1L and 1R consensus sequences and extend to portions of the sequence previously defined as 2L and 2R sequences (39), with the exception of the attCdfrA1 site. The discrepancy in the 2L sequence and the 1L-2L spacer length in this last site, five nucleotides instead of four (Fig. 1), is certainly at the origin of its low recombination frequency with IntI1. Using the deletion assay platform, we introduced a series of mutations into the VCR1 and VCR2 sites. We mutated different segments of the 1L and 1R sequences, disrupted the complementarity of the specific 1L and 1R sequences from the same cassette, and tested the effect of restoration of the complementarity by using a different sequence. The consensus sequences for the 1L and 1R sequences of resistance cassette attC sites were determined previously to be RYYYAAC and GTTRRRY, respectively (8, 16, 39). We previously determined that the 1L and 1R sequences in the VCRs are RCMTAAC and GTTAKGY (where K is G or T, M is A or C, Y is C or T, and R is A or G), respectively (34). In all cases, these sequences have two parts: an absolutely conserved sequence (AAC and GTT) and a less conserved region, which is always perfectly complementary in the 1L and 1R sequences of a defined cassette. Our results show that mutations that altered the 1L TAAC sequence, even if they drastically reduced the levels of VchIntIA and IntI1 recombination activities, did not result in complete abolition of a cassette deletion, as observed with changes introduced into the 1R GTTA sequence. This suggested that the identity of the invariant bases of the 1L sequence is less critical than conservation of the 1R GTT sequence. Similar results were obtained by Stokes et al. when they tested IntI1 activity on attCaadB with a mutation in its 1L sequence (39). We also replaced the conserved A in the VCR 1R sequence (GTTAKGY) with a G. Although this nucleotide is rarely found in the V. cholerae SI cassettes, many resistance cassette 1R sequences carry such a nucleotide. This mutation had only a slight effect (twofold reduction) on the cassette deletion frequencies catalyzed by the two integrases, which might have been due to the disruption of the 1L/1R complementarity. Indeed, disruption of the complementarity between the 1L and 1R sequences, outside the conserved TAAC and GTTA in either the 1L or the 1R sequence of the synthetic cassette, reduced the deletion frequencies by 10- to 25-fold for both integrases, depending on the sequence (Fig. 2). When the complementary 1L and 1R sequence mutations were combined to restore complementarity, the deletion frequency for IntI1 was increased to up to one-half of the frequency measured for the original synthetic cassette. Remarkably, this restoration did not significantly increase the deletion frequency catalyzed by VchIntIA compared to the frequency measured for each complementarity-disrupted mutant. As the restored complementary sequence differs from the VCR 1R/1L consensus sequence only by the presence of C in place of the conserved G at position 6 (GTTAKGY), it is possible that this difference between IntI1 and VchIntIA reflects a lower tolerance for a nucleotide other than G at this position for the V. cholerae SI integrase compared to IntI1. The cause of the functional requirement for 1L/1R complementarity is still unclear, but the overall symmetry visible in the different attC sites suggests that they might adopt, at least transiently, a stem-loop structure, which could require an extended complementary region to increase its stability. However, the role of such a secondary structure in recombination is still unknown.

We also extended our mutation experiments to the AA nucleotides located immediately 3′ of the 1L sequence and to the GC just 5′ of the 1R sequence, as these positions were found to be conserved in all the attC sites of the Vibrio SIs characterized so far (VXRs). Interestingly, we noticed that for the different attC sites that we tested, VchIntIA activity could in general be correlated with the level of conservation at these four positions (with the notable exception of attCdfrA1, but this site has other specific features that may explain its poor recombination, as discussed above). Indeed, the two resistance cassette attC sites recombined by VchIntIA at high rates, attCaadA7 and attCaadB, also showed conservation of all four or three of four of these nucleotides, while the attCereA and attCorfA sites, which had been found to be poor substrates for VchIntIA among the sites tested, showed substitution at two and three of these four conserved positions, respectively (Fig. 1). We established that replacement of the conserved C abutting the 1R sequence by a T (position −1 from the first G of the 1R3 sequence, GTTAGGT) reduced the cassette deletion frequency by about four- to fivefold for both integrases, while replacement of the GG at positions −3 and −2 from the 1R3 sequence (Fig. 2) decreased the VchIntIA recombination rates by 10-fold but not the IntI1 activity (0.6-fold reduction). Interestingly, mutations at corresponding positions in the 1L2 region (Fig. 2) also showed that replacement of the nucleotide (A) at position 1 from the 1L2 sequence last C (TTATAAC) reduced both integrase activities by 3- to 10-fold, while extension of the substitution to the AA at position 2 and 3 from the 1L2 sequence had only a minor effect on cassette deletion by IntI1 but reduced the VchIntIA activity by 50-fold (Fig. 2). We established previously that these positions are extremely conserved among the VXRs (34). The present results, either those obtained with the different resistance cassette attC sites or those obtained through mutation, demonstrate that these positions are key elements for attC site recognition or recombination by the SI integron integrase, while IntI1 activity clearly tolerates more variations at these positions. The fact that class 1 MRIs are found in a diverse range of gram-negative bacterial species could explain the great attC site structural tolerance of IntI1.

The integration assay that we developed led us to confirm the results obtained previously with the R388 assay (35), that cassette integration in a class 1 MRI catalyzed by IntI1 was effective in multiple bacterial species. The integration frequencies that we determined for IntI1 at its attI1 site were almost identical for E. coli and V. cholerae. This was not the case for the VchIntIA-catalyzed integration through attIVch-×-VCR recombination. Indeed, we barely detected such reactions using the assay when tests were performed with E. coli (5 × 10−6), while reactions were found to occur in V. cholerae at a 2,000-fold-higher rate (Table 6). These results were unexpected, as the VCR and attIVch recombination sites are the natural substrates of VchIntIA. Until now, all integron integrases tested were able to catalyze recombination between various attC sites and their own attI site in E. coli (7, 10, 14, 17, 19, 21, 23); however, in several cases, the efficiency of the recombination was not determined. It is assumed that recombination by these IntI integrases did not require any accessory protein for site-specific recombination. Furthermore, no known recognition site for the DNA-binding protein required in other tyrosine recombinase recombination systems, such as the IHF (integration host factor) or FIS (factor for inversion stimulation) systems (1, 20), has been identified adjacent to any IntI recombination site. However, as no in vitro recombination assay has been successfully developed, this presumption is still questionable. Therefore, the simplest explanation for the observed low level of integration in a reconstituted system in E. coli is that VchIntIA requires, at least for the integration process, an accessory protein which is either absent or too divergent in E. coli to sustain the VchIntIA-mediated integration process. In the case of IntI1, if such an accessory protein is required for IntI1 integration at its attI1 site, the evolutionary constraints exerted on the MRI systems, which are carried on mobile elements and then selected to be operational in multiple hosts, may explain why it is able to recombine at the same rates in E. coli and V. cholerae.

Another explanation is a lower intracellular concentration of VchIntIA, due to either a lower level of synthesis or lower stability in E. coli. It is possible that in the intramolecular deletion the level would not be restrictive but would become limiting for intermolecular recombination reactions. However, we unsuccessfully tested VchIntIA-catalyzed deletion of a cassette in the first position (attIVch-lacIq-VCR) (data not shown), which is also an intramolecular deletion, suggesting that the attIVch recombination complex is somehow nonfunctional in E. coli.

The nature of such a hypothetical accessory protein is difficult to predict, as the proteins associated with known site-specific recombination systems are extremely variable (27), and further work is necessary to clarify the factors responsible for the difference between IntI1 and VchIntIA activities.

Taken together, our results suggest that the recombination process in the integron system might be more complex than previously proposed. We have established that even if the range of attC sites efficiently recombined by VchIntIA is narrower than the range for IntI1, the range of sites efficiently recombined by VchIntIA clearly extends beyond the structural diversity of the VCRs found in the V. cholerae SIs. These observations suggest either that the cassettes found in the V. cholerae SIs have a common origin or that V. cholerae is somehow able to assemble new cassettes from its existing pool by adding a VCR to an incoming exogenous DNA molecule.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dean Rowe-Magnus and David Musgrave for helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript.

L.B. is a CROUS (Programme de Cooperation Algéro-Française), Société de Secours des Amis des Sciences, and Pasteur-Weizmann doctoral fellow. M.B. is a MENESR doctoral fellow. This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS, the Programme de Recherche en Microbiologie of MENESR, and the DGA (contract 0134020).

REFERENCES

- 1.Azam, T. A., and A. Ishihama. 1999. Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33105-33113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker, A., C. A. Clark, and P. A. Manning. 1994. Identification of VCR, a repeated sequence associated with a locus encoding a hemagglutinin in Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Bacteriol. 176:5450-5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartolome, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvier, J., A. P. Pugsley, and P. Stragier. 1991. A gene for a new lipoprotein in the dapA-purC interval of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 173:5523-5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang, S. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2000. Construction of a Vibrio cholerae vaccine candidate using transposon delivery and FLP recombinase-mediated excision. Infect. Immun. 68:6391-6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collis, C. M., and R. M. Hall. 1992. Site-specific deletion and rearrangement of integron insert genes catalyzed by the integron DNA integrase. J. Bacteriol. 174:1574-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collis, C. M., M. J. Kim, S. R. Partridge, H. W. Stokes, and R. M. Hall. 2002. Characterization of the class 3 integron and the site-specific recombination system it determines. J. Bacteriol. 184:3017-3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collis, C. M., M. J. Kim, H. W. Stokes, and R. M. Hall. 1998. Binding of the purified integron DNA integrase Intl1 to integron- and cassette-associated recombination sites. Mol. Microbiol. 29:477-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collis, C. M., G. D. Recchia, M. J. Kim, H. W. Stokes, and R. M. Hall. 2001. Efficiency of recombination reactions catalyzed by class 1 integron integrase IntI1. J. Bacteriol. 183:2535-2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drouin, F., J. Melancon, and P. H. Roy. 2002. The IntI-like tyrosine recombinase of Shewanella oneidensis is active as an integron integrase. J. Bacteriol. 184:1811-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fluit, A. C., and F. J. Schmitz. 2004. Resistance integrons and super-integrons. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:272-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, R. M. 1997. Mobile gene cassettes and integrons: moving antibiotic resistance genes in gram-negative bacteria. Ciba Found. Symp. 207:192-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall, R. M., C. M. Collis, M. J. Kim, S. R. Partridge, G. D. Recchia, and H. W. Stokes. 1999. Mobile gene cassettes and integrons in evolution. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 870:68-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall, R. M., and H. W. Stokes. 1993. Integrons: novel DNA elements which capture genes by site-specific recombination. Genetica 90:115-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansson, K., O. Skold, and L. Sundstrom. 1997. Non-palindromic attl sites of integrons are capable of site-specific recombination with one another and with secondary targets. Mol. Microbiol. 26:441-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansson, K., L. Sundstrom, A. Pelletier, and P. H. Roy. 2002. IntI2 integron integrase in Tn7. J. Bacteriol. 184:1712-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes, A. J., M. R. Gillings, B. S. Nield, B. C. Mabbutt, K. M. Nevalainen, and H. W. Stokes. 2003. The gene cassette metagenome is a basic resource for bacterial genome evolution. Environ. Microbiol. 5:383-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes, A. J., M. P. Holley, A. Mahon, B. Nield, M. Gillings, and H. W. Stokes. 2003. Recombination activity of a distinctive integron-gene cassette system associated with Pseudomonas stutzeri populations in soil. J. Bacteriol. 185:918-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landy, A. 1989. Dynamic, structural, and regulatory aspects of lambda site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58:913-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leon, G., and P. H. Roy. 2003. Excision and integration of cassettes by an integron integrase of Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 185:2036-2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levesque, C., S. Brassard, J. Lapointe, and P. H. Roy. 1994. Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for the antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene 142:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez, E., and F. de la Cruz. 1990. Genetic elements involved in Tn21 site-specific integration, a novel mechanism for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. EMBO J. 9:1275-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez, E., and F. de la Cruz. 1988. Transposon Tn21 encodes a RecA-independent site-specific integration system. Mol. Gen. Genet. 211:320-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez, M. A., V. Pezo, P. Marliere, and S. Wain-Hobson. 1996. Exploring the functional robustness of an enzyme by in vitro evolution. EMBO J. 15:1203-1210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazel, D., B. Dychinco, V. A. Webb, and J. Davies. 1998. A distinctive class of integron in the Vibrio cholerae genome. Science 280:605-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCulloch, R., M. E. Burke, and D. J. Sherratt. 1994. Peptidase activity of Escherichia coli aminopeptidase A is not required for its role in Xer site-specific recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 12:241-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metcalf, W. W., W. Jiang, and B. L. Wanner. 1994. Use of the rep technique for allele replacement to construct new Escherichia coli hosts for maintenance of R6K gamma origin plasmids at different copy numbers. Gene 138:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nemergut, D. R., A. P. Martin, and S. K. Schmidt. 2004. Integron diversity in heavy-metal-contaminated mine tailings and inferences about integron evolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1160-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nield, B. S., A. J. Holmes, M. R. Gillings, G. D. Recchia, B. C. Mabbutt, K. M. Nevalainen, and H. W. Stokes. 2001. Recovery of new integron classes from environmental DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 195:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunes-Duby, S. E., H. J. Kwon, R. S. Tirumalai, T. Ellenberger, and A. Landy. 1998. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:391-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recchia, G. D., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology 141:3015-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., A.-M. Guerout, P. Ploncard, B. Dychinco, J. Davies, and D. Mazel. 2001. The evolutionary history of chromosomal super-integrons provides an ancestry for multi-resistant integrons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:652-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., A. M. Guerout, L. Biskri, P. Bouige, and D. Mazel. 2003. Comparative analysis of superintegrons: engineering extensive genetic diversity in the Vibrionaceae. Genome Res. 13:428-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., A. M. Guerout, and D. Mazel. 2002. Bacterial resistance evolution by recruitment of super-integron gene cassettes. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1657-1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., and D. Mazel. 2001. Integrons: natural tools for bacterial genome evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:565-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., and D. Mazel. 2002. The role of integrons in antibiotic resistance gene capture. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stokes, H. W., A. J. Holmes, B. S. Nield, M. P. Holley, K. M. Nevalainen, B. C. Mabbutt, and M. R. Gillings. 2001. Gene cassette PCR: sequence-independent recovery of entire genes from environmental DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5240-5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stokes, H. W., D. B. O'Gorman, G. D. Recchia, M. Parsekhian, and R. M. Hall. 1997. Structure and function of 59-base element recombination sites associated with mobile gene cassettes. Mol. Microbiol. 26:731-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundstrom, L. 1998. The potential of integrons and connected programmed rearrangements for mediating horizontal gene transfer. APMIS Suppl. 84:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaisvila, R., R. D. Morgan, J. Posfai, and E. A. Raleigh. 2001. Discovery and distribution of super-integrons among pseudomonads. Mol. Microbiol. 42:587-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]