Abstract

The expression of ribosome modulation factor (RMF) is induced during stationary phase in Escherichia coli. RMF participates in the dimerization of 70S ribosomes to form the 100S ribosome, which is the translationally inactive form of the ribosome. To elucidate the involvement of the control of mRNA stability in growth-phase-specific rmf expression, we investigated rmf mRNA stability in stationary-phase cells and cells inoculated into fresh medium. The rmf mRNA was found to have an extremely long half-life during stationary phase, whereas destabilization of this mRNA took place after the culture was inoculated into fresh medium. RMF and 100S ribosomes disappeared from cells 1 min after inoculation. In addition to control by ppGpp-dependent transcription, these results indicate that the modulation of rmf mRNA stability is also involved in the regulation of growth-phase-specific rmf expression. Unexpectedly, the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA was suppressed by the addition of rifampin, suggesting that de novo RNA synthesis is necessary for degradation. This degradation was also suppressed in both a poly(A) polymerase-deficient and an rne-131 mutant strain. We cloned and sequenced the 3′-proximal regions of rmf mRNAs and found that most of these 3′ ends terminated at the ρ-independent terminator with the addition of a one- to five-A oligo(A) tail in either stationary-phase or inoculated cells. No difference was observed in the length of the poly(A) tail between stationary-phase and inoculated cells. These results suggest that a certain postinoculation-specific regulatory factor participates in the destabilization of rmf mRNA and is dependent on polyadenylation.

Bacteria have evolved various mechanisms by which they alter gene expression to adapt to changes in environmental and intracellular conditions. The mechanisms through which different genes modulate their expression depend on their respective functions. In some cases, several different mechanisms, such as the control of transcription and translation and the modulation of the stability of the mRNA and protein, are used to regulate the expression of a single gene.

Expression of the ribosome modulation factor (RMF) is induced during stationary phase in the presence of ppGpp, which is known to be a mediator of stringent control (17, 36, 37). RMF binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit to mediate the dimerization of 70S ribosomes to form the 100S ribosome, which is a translationally inactive form (37). In a recent study, it was demonstrated that RMF covers the peptidyl transferase center and the entrance of the peptide exit tunnel (42). The dimerization reaction is reversible, as the 100S ribosomes dissociate back into 70S ribosomes within 2 min after cells are transferred into fresh medium (36, 41) and as protein synthesis and cell proliferation resume within 6 min (38).

Recently, we found that the rmf mRNA is extremely stable in stationary-phase cells. In light of the RMF function described above, it is reasonable to assume that the modulation of rmf mRNA stability plays a role in the growth-phase-dependent regulation of rmf expression. In this study, we report that rmf mRNA is destabilized after the inoculation of stationary-phase cells into fresh medium. This degradation was suppressed in both rne-131 and pcnB deletion mutants. The rmf mRNA was shown to be polyadenylated in either stationary-phase or inoculated cells. Furthermore, de novo synthesis of a particular RNA (or its translation product) was necessary for the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The Escherichia coli strains used for this study are described in Table 1. Cells were grown at 37°C in EP medium (Vogel-Bonner minimal medium containing 2% polypeptone and 0.5% glucose) (33). Vogel-Bonner minimal medium contains the following reagents (per liter): 0.2 g of magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, 2 g of citric acid monohydrate, 10 g of dipotassium hydrogenphosphate, and 3.5 g of ammonium sodium hydrogenphosphate tetrahydrate. Thymine and rifampin were added to the culture medium at final concentrations of 25 and 500 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used for this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MG1693 | thyA715 | Arraiano et al. | 4 |

| SK7988 | MG1693 ΔpcnB Kmr | O'Hara et al. | 28 |

| SK7622 | MG1693 Δrnc-38 Kmr | Babitzke et al. | 5 |

| IBPC856 | MG1693 rne131 | P. E. Marujo and P. Regnier | |

| CSH26 | ara Δ(lac-pro) thi | Miller | 24 |

| HAT10 | CSH26 hfq::cat | Wachi et al. | 35 |

| MG1655 rpoB2 | rpoB2 btuB::Tn10 | Jin and Gross | 19 |

Oligonucleotides.

The following primers were used for PCR: rmf(−135) (5′-GCTCACAAATATGACAGTGGCG), rmf115 (5′-GTGACCTTTGATTCAGCGTCTG), 5S rRNA-L (5′-TGATGTCTGGCAGTTCCCTACTCT), 5S rRNA-U (5′-AACTCAGAAGTGAAACGCCGTAGC), rpoS27 (5′-GAGCCACCTTATGAGTCAGAAT), rpoS471 (5′-GTATGTTGAGAAGCGGAAACCA), dps31 (5′-GCGACCAATCTGCTTTATACCC), dps369 (5′-GTCAGCCAGTTCTTTCAGGTGA), ompA64 (5′-GCTCCGAAAGATAACACCTGGT), and ompA517 (5′-TGTGTGCGTCACCGATGTTGTT). The following primers were used for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR): rmf92 (5′-TAGGGACACATTTCTTTTGAGC), rmf125 (5′-CCCAGCCATTGTGACCTTTGAT), rmf142 (5′-ATGGCGGACAGGGTAGTAAT), and rmf181 (5′-AAAAAGAAACCTCCGCATTGC). An X-rhodamine isothiocyanate (XRITC)-labeled primer (5′ XRITC-rmf125 [5′ XRITC-CCCAGCCATTGTGACCTTTGAT]) was used for primer extension. The numbers in the primer names indicate the 5′ positions of the primers relative to the translational start site (+1) of each gene.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA samples, extracted with hot phenol as described previously (1), were fractionated by electrophoresis at 80 V for 2 to 3 h in a 1.5% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde. RNAs were then blotted onto a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). Alternatively, total RNA samples were fractionated in a 7 M urea-6% polyacrylamide gel and then electroblotted onto a Clear Blot N Plus membrane (Atto) (2). Hybridization was performed as described previously (3). For Northern analysis of 5S rRNA, hybridization was performed in the presence of a solution containing 5× SSC, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5% dextran sulfate, and 5% Liquid Block (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at 60°C. The levels of radioactivity in specific bands in Northern hybridizations were quantified by use of a FLA3000G imaging analyzer (Fuji). A 20-bp molecular ruler (Bio-Rad) was used as a size marker for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Sucrose density gradient centrifugation.

MG1693 stationary-phase cells were transferred into fresh medium, and a portion of the culture was removed 1 and 4 min after inoculation. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −80°C. Crude ribosomes were prepared essentially according to the procedure of Noll et al., with slight modifications as described by Horie et al. (16, 27). The ribosomes were subjected to centrifugation on 5 to 20% linear sucrose density gradients in association buffer containing 6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. After centrifugation in an SW40Ti rotor (Beckman) at 40,000 rpm for 90 min at 4°C, ribosome profiles were observed at 260 nm with a UV-160A spectrometer (Shimadzu) using a flow cell.

Western blotting of RMF protein.

MG1693 stationary-phase cells were transferred into fresh medium, and a portion of the culture was removed 1 and 4 min after inoculation. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −80°C. Total cell extracts were subjected to Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. RMF was detected by use of an anti-RMF antibody.

Primer extension.

Primer extension experiments were performed essentially according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer (GIBCO BRL). Two picomoles of 5′ XRITC-rmf125 (TaKaRa) was annealed with 10 μg of total RNA at 50°C, and cDNAs were synthesized with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL). The cDNAs were subjected to 8 M urea-6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by use of an FMBIO-100 Fluor Bio image analyzer (Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Ltd.).

Circularization RT-PCR.

Total RNAs extracted from MG1693 stationary-phase cells or from cells harvested 3 min after inoculation were used for circularization RT-PCR, which was performed as described previously (11). We used a modified procedure based on a previously reported method to analyze bacterial mRNAs (40). Total RNAs were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). The DNA-free total RNAs (6.3 μg) were dephosphorylated by the use of calf intestinal or E. coli A19 alkaline phosphatase (TaKaRa) and then phosphorylated by the use of T4 polynucleotide kinase (TaKaRa) to convert the 5′ termini of all mRNAs to a monophosphorylated state. The RNAs were ligated at 12°C overnight by the use of T4 RNA ligase to achieve either self-circularization or intermolecular ligation. The RNase inhibitor RNasin (Promega) was added to all reaction mixtures, and cDNAs were synthesized at 43°C (rmf92) or 50°C (rmf125) by the use of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL) according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer. PCRs were performed with 2 μl of cDNA in 25-μl reaction mixtures and consisted of 25 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The primer sets rmf92-rmf142 and rmf125-rmf181 were used. The PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced by use of the Rapid Gene system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RESULTS

rmf mRNA has a long half-life in stationary-phase cells.

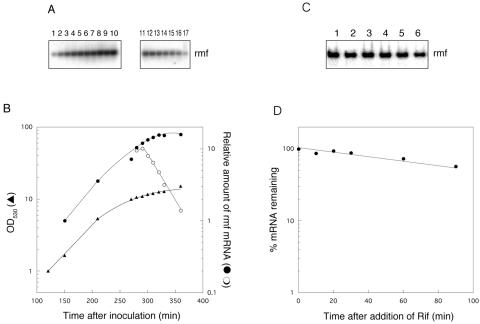

Initially, we observed growth-phase-dependent rmf transcription in EP medium by Northern analysis. The rmf transcript was not detected during log phase (data not shown), but a hybridized band appeared at the transition from log to stationary phase, consistent with previous observations (37). The mRNA level observed for early stationary phase (280 min) was approximately 10-fold higher than that seen for late log phase (150 min) (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 4, and B, closed circles). Rifampin was added to an aliquot of the culture at 280 min to inhibit transcription initiation. The half-life of rmf mRNA during early stationary phase, calculated from the data shown in Fig. 1B (open circles), was approximately 24 min. The half-life was prolonged to approximately 120 min in cells cultured for an additional 17 h when the cells had reached stationary phase (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG. 1.

Growth-phase-dependent induction of rmf transcription and half-life of rmf mRNA at stationary phase. (A) Cells of MG1693 were grown in EP medium containing 25 μg of thymine/ml until late log phase, and portions of the culture were removed 150 (lane 1), 210 (lane 2), 270 (lane 3), 280 (lane 4), 290 (lane 5), 300 (lane 6), 310 (lane 7), 320 (lane 8), 330 (lane 9), and 360 (lane 10) min after inoculation. Rifampin (500 μg/ml) was added to an aliquot of the culture at 280 min, and samples were removed at 280 (lane 11), 290 (lane 12), 300 (lane 13), 310 (lane 14), 320 (lane 15), 330 (lane 16), and 360 (lane 17) min. Total RNAs (10 μg) were analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with a 1.5% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde. (B) Relative amounts of rmf mRNA were calculated from the intensities of the hybridized bands in panel A and then plotted against the time after inoculation. •, lanes 1 to 10 from panel A; ○, lanes 11 to 17 from panel A; ▴, optical density at 530 nm. (C) Cells that were cultured for an additional 17 h when the cells had reached stationary phase were removed 0, 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 min after the addition of rifampin. Total RNAs (8 μg) were analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. (D) Amounts of rmf mRNA were calculated from the intensities of the bands in panel C and then plotted against the time after the addition of rifampin.

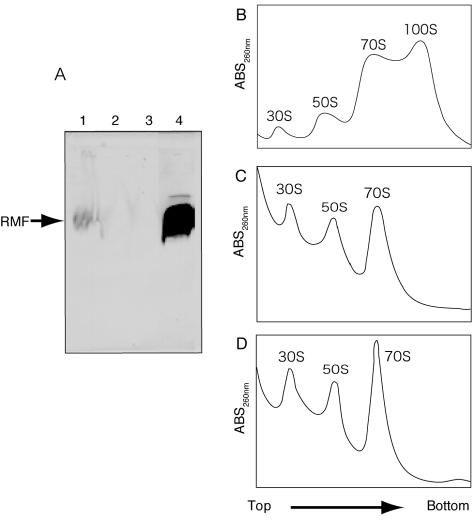

The RMF protein rapidly disappears from cells inoculated into fresh medium.

Previous reports have shown that when stationary-phase cells are transferred into fresh medium, RMF is immediately released from the 100S ribosomes, which subsequently dissociate into 70S ribosomes, allowing cell proliferation to begin within 6 min (38, 39). The amounts of RMF protein in both stationary-phase cells and inoculated cells were determined by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A). RMF was detected in preparations from stationary-phase cells (lane 1) but could no longer be detected 1 min after inoculation (lane 2). The 100S ribosomes observed in stationary-phase cells (Fig. 2B) were also not detected at that time (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Western blotting of RMF and sucrose density gradient centrifugation profiles of ribosomes. (A) Total cell extracts were obtained from MG1693 stationary-phase cells (lane 1) or cells collected 1 (lane 2) or 4 (lane 3) min after inoculation. Lane 4, His-tagged RMF. (B, C, and D) Crude ribosome fractions were obtained from MG1693 stationary-phase cells (B) or cells collected 1 (C) or 4 (D) min after inoculation.

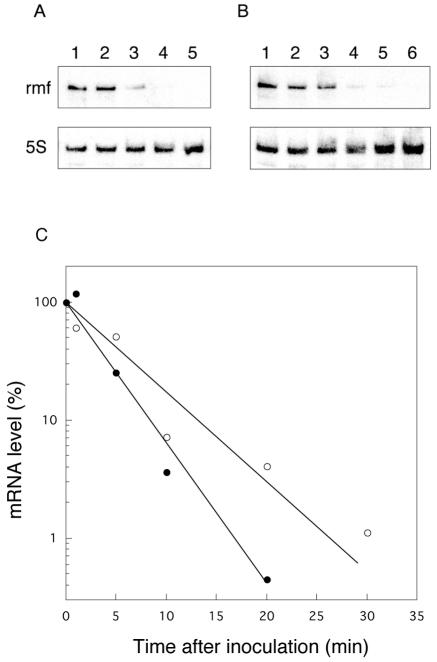

Destabilization of rmf mRNA after stationary-phase cells are transferred into fresh EP medium.

Next, we analyzed the rmf mRNA levels in cells that had been transferred into fresh medium (Fig. 3). Ten minutes after inoculation, the mRNA level declined to <5% that at time zero (Fig. 3A and C, closed circles). For the results shown in Fig. 3A, equal amounts (8 μg) of total RNAs were loaded into each lane. The amount of cellular rRNA was expected to increase after inoculation, since rifampin was not added to the culture medium to inhibit transcription. Consequently, the decline of rmf mRNA observed in Fig. 3A reflects the sum of the dilution of rmf mRNA in the total RNA pool and the net degradation. To exclude the dilution effect, we determined the amount of rmf mRNA in the total RNA extracted from 5 ml of inoculated cell culture (Fig. 3B). The total RNA extracted from 5 ml of culture at time zero (15.5 μg) increased with time, with an approximately 3.4-fold (52 μg) increase 30 min after inoculation (data not shown). These results indicate that when equal amounts of total RNA are used for calculation of the amount of rmf mRNA remaining after inoculation, the value will be one-third of that obtained when a constant volume of culture is used. Previous studies have shown that the transcription of rmf is strictly dependent on the cellular level of guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) (17). The transcription of rmf is expected to be markedly reduced after inoculation, since the level of ppGpp falls immediately after cells are transferred into fresh medium (9). Assuming that some residual transcription of rmf mRNA occurs after inoculation, the decay rate of rmf mRNA obtained in the experiment shown in Fig. 3B should represent the minimum value. The half-life of rmf mRNA obtained from the data shown in Fig. 3B is approximately 5 min. These results indicate that rmf mRNA, which is extremely stable in stationary-phase cells, is dramatically destabilized after inoculation.

FIG. 3.

Measurement of rmf mRNA levels after stationary-phase cells were transferred into fresh medium. The stationary-phase cells were transferred (at an optical density at 530 nm [OD530]of 0.3) to fresh EP medium containing thymine, and portions of the culture were removed at different time points. (A) Total RNAs (8 μg) of MG1693 were analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. Lanes: 1, 0 min; 2, 1 min; 3, 5 min; 4, 10 min; 5, 20 min (times after inoculation). (B) Total RNAs extracted from 5 ml of the culture were analyzed. Lanes: 1, 0 min; 2, 1 min; 3, 5 min; 4, 10 min; 5, 20 min; 6, 30 min (times after inoculation). (C) Relative amounts of rmf mRNA were calculated from the intensities of the hybridized bands in panel A (•) and panel B (○) and then expressed as percentages of the value at the time of inoculation.

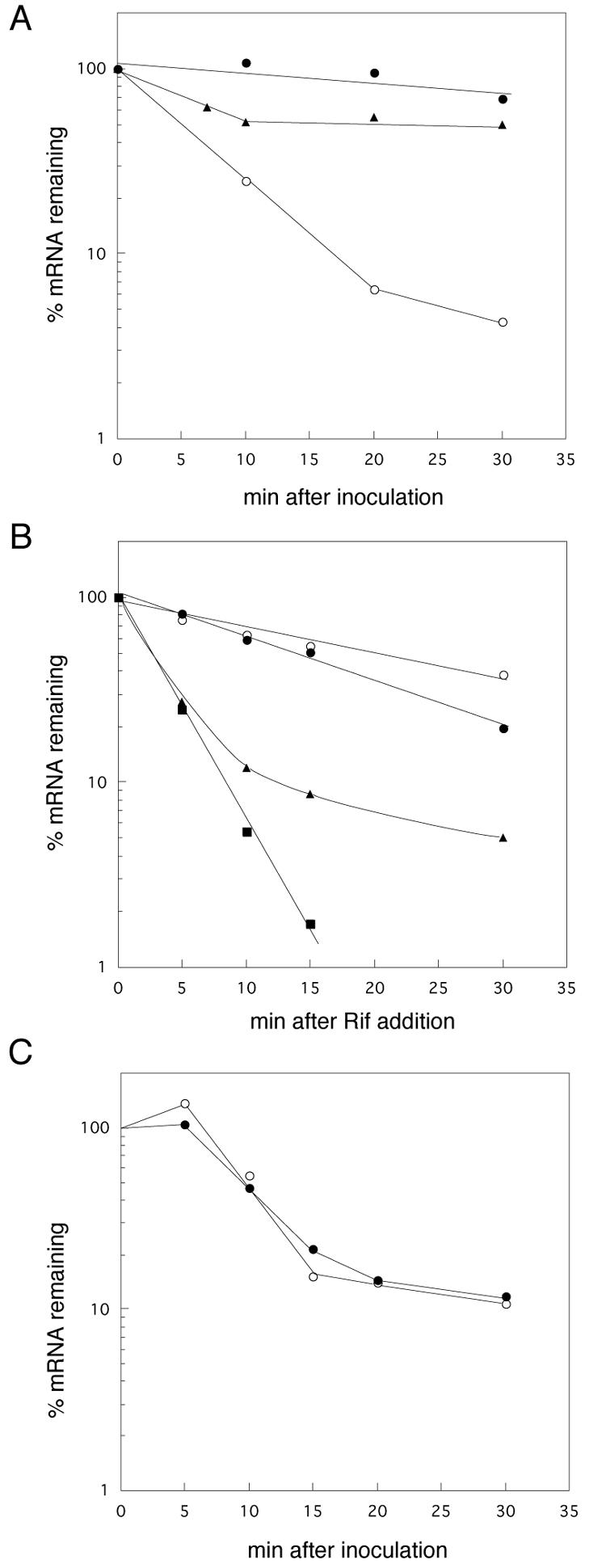

Postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA is inhibited by addition of rifampin.

Unexpectedly, we found that the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA was suppressed by the addition of rifampin at the time of inoculation (Fig. 4A, open and filled circles). When rifampin was added 7 min after inoculation, the degradation occurred during the first 10 min and was then severely inhibited (Fig. 4A, filled triangles).

FIG. 4.

Effect of addition of rifampin on postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA. (A) MG1693 stationary-phase cells were transferred (OD530 = 0.3) into fresh EP medium with (•) or without (○) rifampin. Cells were also transferred into fresh EP medium without rifampin and cultured for 7 min, and then rifampin was added (▴). Total RNAs extracted from 2.5 ml of the culture were analyzed. (B) MG1693 stationary-phase cells were transferred into fresh medium (OD530 = 0.1), and rifampin was added 5 min after inoculation. At set time intervals after the addition of rifampin, portions of the culture were removed and total RNAs were extracted. Total RNAs (10 μg) were electrophoresed and hybridized with a radioactively labeled probe for rmf (○), ompA (•), rpoS (▴), or dps (▪). (C) Stationary-phase cells of the rpoB2 mutant were transferred (OD530 = 0.3) into fresh EP medium with (○) or without (•) rifampin. Total RNAs extracted from 2.5 ml of culture were analyzed with a radioactively labeled probe for rmf.

To examine whether or not the effect of rifampin on the postinoculation degradation was specific for the rmf mRNA, we measured the amounts of rpoS, dps, and ompA mRNAs in inoculated cells after the addition of rifampin (Fig. 4B). The transcription of rpoS, which encodes the σs subunit of RNA polymerase, is induced during the transition from log to stationary phase (20). The expression of rpoS is also positively regulated by ppGpp (13). The dps gene encodes a major nucleoid protein in stationary-phase cells (30). The ompA transcript is known to be stable in E. coli. The half-life of the ompA transcript is 12 to 18 min in exponentially growing cells, and its stability is dependent on the growth rate (26). As shown in Fig. 4B, the levels of rpoS and dps mRNAs declined to <20% within 5 min after the addition of rifampin (closed triangles and closed squares). The levels of rpoS and dps mRNAs declined more slowly in inoculated cells that were cultured without rifampin (data not shown). The level of ompA mRNA diminished to 50% in 13 min, which agrees with the reported half-life of ompA mRNA in exponentially growing cells (26). These results indicate that the inhibitory effect of rifampin on the postinoculation degradation of mRNA is specific to rmf mRNA.

The RNA polymerase β subunit is known to be a target of rifampin (29). Transcription in the rpoB2 mutant is resistant to rifampin because rifampin cannot bind to its target site on the mutant β subunit (19). Assuming that rifampin suppresses postinoculation degradation through the inhibition of RNA polymerase activity, rifampin should have no effect on postinoculation degradation in the rpoB2 mutant. As shown in Fig. 4C, the addition of rifampin had no effect on the degradation of rmf mRNA in the rpoB2 mutant, suggesting that rifampin suppresses postinoculation degradation by inhibiting RNA polymerase activity. The results also showed that the decay curve for rmf mRNA in the rpoB mutant was sigmoid rather than exponential. At present, we have no explanation for this observation.

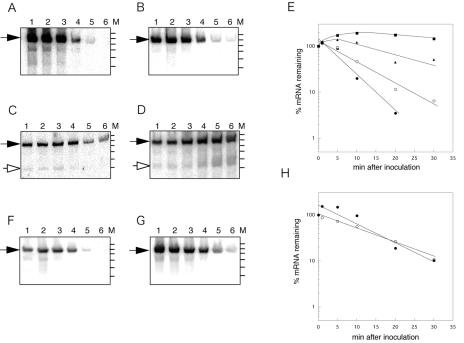

Factors that participate in postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA.

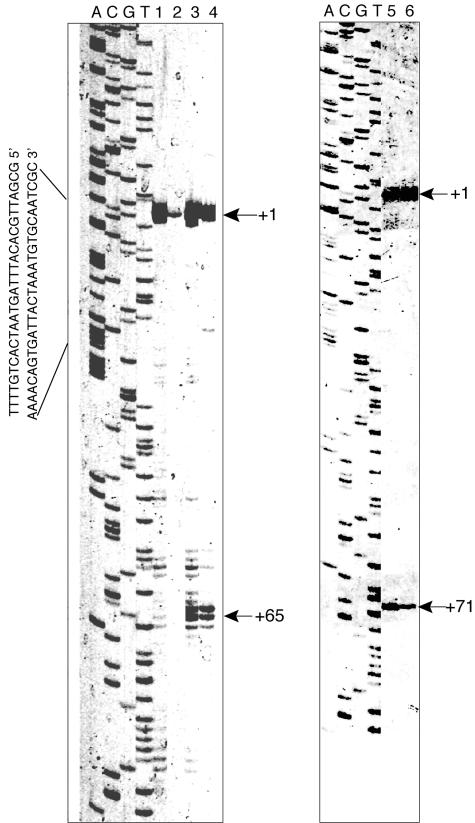

Next, we attempted to characterize factors that participate in the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA (Fig. 5). RNase III and RNase E are key endoribonucleases that are involved in the degradation of mRNAs in E. coli. It is known that the polyadenylation of mRNA plays a role in the control of mRNA stability (14, 25). Hfq is a trans-acting factor that stabilizes or destabilizes some mRNAs and is also a poly(A) binding protein that protects rpsO mRNA from exonucleolytic degradation (15, 23, 31, 34). We analyzed the levels of rmf mRNA in a strain containing the rne-131 mutation or in strains deficient in RNase III, poly(A) polymerase, or Hfq. As shown in Fig. 5, the degree of postinoculation degradation without the addition of rifampin in the RNase III-deficient strain was approximately 50% of that observed for the wild-type strain (panel B and open circles in panel E). In contrast, degradation was greatly suppressed in the rne-131 mutant (panel C and filled triangles in panel E) and totally suppressed in the ΔpcnB mutant (panel D and filled squares in panel E). Smaller fragments, of approximately 200 nucleotides (nt) (open arrow in panel C) and 210 nt (open arrow in panel D), other than an ∼270-nt full-length rmf transcript (filled arrows) were observed in the rne-131 and ΔpcnB mutants, respectively, both before and after inoculation. We further analyzed the 5′ termini of these rmf mRNAs by primer extension (Fig. 6); additional 5′ ends at +65 and +71 were detected both before and after inoculation. The 5′ ends at +65 and +71 may have been derived from the 210- and 200-nt fragments, respectively, seen in the Northern analysis. Consistent with the results of the Northern analysis, a decrease in the 5′ end signal of the full-length rmf mRNA after inoculation was suppressed efficiently in both poly(A) polymerase (lanes 3 and 4) and RNase E (lanes 5 and 6) mutant cells. The Hfq deficiency had a minor effect on the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA (Fig. 5F, G, and H).

FIG. 5.

Postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA in mutant cells. Stationary-phase cells were transferred (OD530 = 0.3) into fresh EP medium. At set time intervals after inoculation, 5 ml of the culture was removed and total RNAs were extracted. Northern analysis was performed with an rmf probe. (A) MG1693 (wt); (B) SK7622 (Δrnc3); (C) IBPC856 (rne-131); (D) SK7988 (ΔpcnB1); (F) CSH26 (wt); (G) HAT10 (hfq10::Cmr). Lanes: 1, 0 min; 2, 1 min; 3, 5 min; 4, 10 min; 5, 20 min; 6, 30 min (times after inoculation). Filled arrows, full-length rmf mRNA; open arrows, predicted processed rmf mRNA; M, molecular size standard, showing 300, 280, 260, 240, 220, and 200 bp. (E and H) Radioactivities in specific bands from panels A to D and from panels F and G, respectively, were quantified and expressed as percentages of the value at time zero. (E) •, MG1693; ○, SK7622; ▴, IBPC856; ▪, SK7988. (H) •, CSH26; ○, HAT10.

FIG. 6.

Primer extension of rmf mRNA. Stationary-phase cells were inoculated into fresh EP medium, and aliquots of culture were removed at different time points. Lanes 1 and 2, MG1693 (wt); lanes 3 and 4, SK7988 (ΔpcnB1); lanes 5 and 6, IBPC856 (rne131). Lanes 1, 3, and 5, stationary-phase cells; lanes 2, 4, and 6, cells collected 9 min after inoculation. Arrowheads with “+1” indicate the transcriptional start points.

rmf mRNA is polyadenylated both during stationary phase and after inoculation.

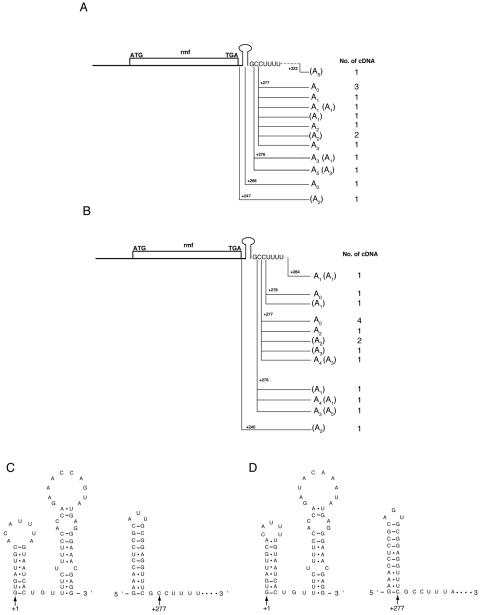

The results obtained with the pcnB mutant suggested that polyadenylation participates in the regulation of rmf mRNA stability. We analyzed mRNA 3′-terminal sequences by using a self-circularization method described by Couttet et al. (11). In this method, RNA is either self-circularized or ligated intermolecularly by the use of T4 RNA ligase, and then a region containing the 5′-3′ junction is amplified by RT-PCR, cloned, and sequenced. We used DNA-free total RNAs extracted from either stationary-phase cells or cells harvested 3 min after inoculation. The nucleotide sequences around the 3′-terminal regions are shown in Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Sites and composition of poly(A) tails and predicted secondary structures at 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of rmf mRNAs. Total RNAs extracted from MG1693 stationary-phase cells (A) or cells harvested 3 min after inoculation (B) were used for circularization RT-PCR. The numbers of cDNA clones obtained are shown on the right. Polyadenylation sites are shown relative to the transcriptional start point (+1). It was not possible to determine from which terminus the A's in parentheses were derived by the circularization RT-PCR method. Secondary structures at 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of rmf mRNAs from E. coli (C) and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (D) were predicted by the mfold program.

For some clones, we did not determine from which terminus the adenine residues (A's in parentheses in Fig. 7) in the 5′-3′ junction region were derived. At least 6 of 15 clones and 5 of 16 clones prepared from stationary-phase cells and inoculated cells, respectively, contained uncoded adenines at their 3-′ termini. In addition, most 3′ termini (26 of 31) were located at positions +276 to +278, at a predicted ρ-independent terminator. Although primer extension analysis showed that most of the rmf mRNA in total RNA preparations contained a 5′ terminus at +1, all of the cloned molecules were found to have processed 5′ ends (data not shown). Ligation efficiency is thought to depend on the RNA sequence (40). An intact 5′ end of rmf mRNA is predicted to form a terminal hairpin structure that contains no unpaired residues at its end (Fig. 7). It is probable that ligation between an intact 5′ terminus and the 3′ terminus of rmf mRNA is obstructed at 12°C and that 5′ termini from which the terminal hairpin has been removed are ligated selectively. We adapted the same experimental procedure for use with acnA mRNA, which has no terminal hairpin at the 5′ end, and found that intact 5′ termini were cloned into the 5′-3′ junction regions and that these mRNAs were not polyadenylated (data not shown). These results indicate that the self-circularization method is not applicable for determining the 5′ ends of mRNAs that possess a stem-loop structure at the 5′ end, since this method yields several potential biases.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the half-life of rmf mRNA in early-stationary-phase cells was observed to be approximately 24 min, which is much longer than its typical half-life (2 to 4 min) in E. coli (7), although most mRNA half-lives have been measured during exponential growth phase. It is well known that the secondary structure of mRNA is one of the important determinants of its stability. Predicted secondary structures of the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of rmf mRNA are shown in Fig. 7C and D. The nucleotide sequences of rmf are highly conserved in gram-negative bacteria. The sequence in Shigella flexneri has only one base difference (A169→G169) from that of E. coli, and the sequence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is 93% identical to the E. coli sequence. The rmf mRNAs of E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium are remarkably similar at their 5′- and 3′-terminal regions; both contain not only the ρ-independent transcriptional terminator in the 3′ end, but also a 5′-terminal hairpin that lacks any unpaired residues in the 5′ end. These conserved terminal hairpin structures may ensure the high stability of rmf mRNA in a similar manner to the 5′-terminal hairpin of ompA mRNA, which is responsible for its longevity (10). It would be interesting to examine whether the 5′-terminal stem-loop of rmf mRNA functions as a stabilizer in stationary-phase cells when it is fused to the 5′ end of a heterologous mRNA.

Once stationary-phase cells were transferred into fresh medium, the RMF protein and 100S ribosome disappeared within 1 min and rmf mRNA was destabilized. However, about 90% of the rmf mRNA still remained 1 min after inoculation (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that an accelerated degradation of the RMF protein is primarily responsible for the rapid disappearance of the RMF that was present in the cells before inoculation. Izutsu et al. reported that the RMF protein is not detected even if the transcription of rmf is induced by ppGpp accumulation during log phase (17). This observation also suggests that proteolysis of RMF is involved in the depletion of RMF from growing cells. The remaining rmf mRNA after inoculation may be translated continuously, but the rapid degradation of RMF exceeds the rate of synthesis. Alternatively, the translation of rmf mRNA may be suppressed by an unknown mechanism after inoculation. rmf mRNA degradation following the rapid disappearance of RMF shuts off the synthesis of nascent RMF and will promote the recycling of ribosomes and nucleotides and be advantageous in the reinitiation of cell growth.

We suggest that RNase E catalyzes the rate-limiting cleavage of rmf mRNA after inoculation and is dependent on binding to the degradosome, since postinoculation degradation was suppressed in an rne-131 mutant that contains the catalytic domain of RNase E but lacks the degradosome scaffolding region (Fig. 5) (21, 22, 32) as well as in a temperature-sensitive rne-1 mutant at a nonpermissive temperature (data not shown). Baker and Mackie introduced an ectopic RNase E site into the 5′ untranslated region of rpsT mRNA, which contains a synthetic 5′-terminal hairpin, and showed that RNase E can bypass the interaction with the 5′ terminus and exploit an alternative internal entry pathway (6). The transcript of rmf has a similar 5′-terminal hairpin, but it does not possess an AU-rich sequence immediately downstream of the 5′-terminal hairpin. To ascertain whether or not the suppression of postinoculation degradation is caused directly by the rne-131 mutation, we needed to determine the position of the RNase E cleavage site in the rmf mRNA. The postinoculation degradation was partially suppressed in the RNase III-deficient strain, suggesting that RNase III may be involved in cleaving the 5′ hairpin structure of rmf mRNA. Whether another endoribonuclease, e.g., RNase G, participates in the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA is unknown.

In a pcnB deletion mutant, the postinoculation destabilization of rmf mRNA was largely suppressed. We assumed that the rmf mRNA was specifically polyadenylated after inoculation, since poly(A) tails have been demonstrated to play a role as a “toehold” for exoribonucleases when mRNAs contain a 3′ hairpin like that of rmf mRNA (Fig. 7) (12, 14), leading to exoribonucleolytic degradation. However, our results showed that the rmf mRNA was polyadenylated in stationary phase as well as soon after inoculation. The length of the poly(A) tails were rather short for both phases, like those of rpsO mRNA in wild-type cells (23). It is possible that after inoculation, rmf mRNAs with longer tails have been made but degraded immediately, preventing detection by our method. Alternatively, polyadenylation alone might not promote postinoculation degradation. At present, we cannot exclude the possibility that the suppression of postinoculation degradation by the pcnB deletion is indirect, i.e., that the polyadenylation of another RNA is necessary for the destabilization of rmf mRNA.

Cao and Sarkar demonstrated that three stationary-phase-specific mRNAs, rpoS, bolA, and dps, were polyadenylated and that, in contrast to the poly(A) tracts that are characteristic of exponentially growing cells, the poly(A) tracts associated with stationary-phase mRNAs were interspersed with other nucleotide residues (8). Jasiecki and Wegrzyn reported that the polyadenylation efficiency was higher in slowly growing cells in which expression of the pcnB gene was up-regulated (18).

The results showing that rifampin specifically inhibits the postinoculation degradation of rmf mRNA and that the rpoB2 mutation suppresses this inhibition are interesting. These results suggest that de novo synthesis of a particular RNA is necessary for this process. This RNA or its translation product may be involved in the growth-phase-specific destabilization of rmf mRNA. The identification of such a factor is the focus of the next stage of our investigation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to C. A. Gross for the bacterial strain MG1655 rpoB2, S. R. Kushner for strains SK7988 and SK7622, P. Regnier for strain IBPC856, and M. Wachi for strains CSH26 and HAT10. We also thank A. Ishihama for helpful discussions.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Science Research Promotion Fund, Japan Private School Promotion Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., S. Adhya, and B. de Crombrugghe. 1981. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 25:11905-11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiso, T., and R. Ohki. 1998. An rne-1 pnp-7 double mutation suppresses the temperature-sensitive defect of lacZ gene expression in a divE mutant. J. Bacteriol. 180:1389-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiso, T., and R. Ohki. 2003. Instability of sensory histidine kinase mRNAs in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 8:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arraiano, C. M., S. D. Yancey, and S. R. Kushner. 1988. Stabilization of discrete mRNA breakdown products in ams pnp rnb multiple mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 170:4625-4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babitzke, P., L. Granger, J. Olszewski, and S. R. Kushner. 1993. Analysis of mRNA decay and rRNA processing in Escherichia coli multiple mutants carrying a deletion in RNase III. J. Bacteriol. 175:229-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker, K. E., and G. A. Mackie. 2003. Ectopic RNase E sites promote bypass of 5′-end-dependent mRNA decay in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 47:75-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belasco, J. G. 1993. mRNA degradation in prokaryotic cells: an overview, p. 3-12. In J. Belasco and G. Brawerman (ed.), Control of messenger RNA stability. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 8.Cao, G. J., and N. Sarkar. 1997. Stationary phase-specific mRNAs in Escherichia coli are polyadenylated. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 239:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cashel, M., D. R. Gentry, V. J. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p. 1458-1496. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Chen, L. H., S. A. Emory, A. L. Bricker, P. Bouvet, and J. G. Belasco. 1991. Structure and function of a bacterial mRNA stabilizer: analysis of the 5′ untranslated region of ompA mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 173:4578-4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couttet, P., M. Fromont-Racine, D. Steel, R. Pictet, and T. Grange. 1997. Messenger RNA deadenylylation precedes decapping in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5628-5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreyfus, M., and P. Regnier. 2002. The poly (A) tail of mRNAs: bodyguard in eukaryotes, scavenger in bacteria. Cell 111:611-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentry, D. R., V. J. Hernandez, L. H. Nguyen, D. B. Jensen, and M. Cashel. 1993. Synthesis of the stationary-phase sigma factor sigma S is positively regulated by ppGpp. J. Bacteriol. 175:7982-7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunberg-Manago, M. 1999. Messenger RNA stability and its role in control of gene expression in bacteria and phages. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:193-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajnsdorf, E., and P. Regnier. 2000. Host factor Hfq of Escherichia coli stimulates elongation of poly (A) tails by poly (A) polymerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1501-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horie, K., A. Wada, and H. Fukutome. 1981. Conformational studies of Escherichia coli ribosomes with the use of acridine orange as a probe. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 90:449-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izutsu, K., A. Wada, and C. Wada. 2001. Expression of ribosome modulation factor (RMF) in Escherichia coli requires ppGpp. Genes Cells 6:665-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasiecki, J., and G. Wegrzyn. 2003. Growth-rate dependent RNA polyadenylation in Escherichia coli. EMBO Rep. 4:172-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin, D. J., and C. A. Gross. 1988. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 202:45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jishage, M., and A. Ishihama. 1995. Regulation of RNA polymerase sigma subunit synthesis in Escherichia coli: intracellular levels of sigma 70 and sigma 38. J. Bacteriol. 177:6832-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaberdin, V. R., A. Miczak, J. S. Jakobsen, S. Lin-Chao, K. J. McDowall, and A. von Gabain. 1998. The endoribonucleolytic N-terminal half of Escherichia coli RNase E is evolutionarily conserved in Synechocystis sp. and other bacteria but not the C-terminal half, which is sufficient for degradosome assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11637-11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kido, M., K. Yamanaka, T. Mitani, H. Niki, T. Ogura, and S. Hiraga. 1996. RNase E polypeptides lacking a carboxyl-terminal half suppress a mukB mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:3917-3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Derout, J., M. Folichon, F. Briani, G. Deho, P. Regnier, and E. Hajnsdorf. 2003. Hfq affects the length and the frequency of short oligo (A) tails at the 3′ end of Escherichia coli rpsO mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:4017-4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. H. 1972. Strain list, p. 13-23. In J. H. Miller (ed.), Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Nierlich, D. P., and G. J. Murakawa. 1996. The decay of bacterial messenger RNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 52:153-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsson, G., J. G. Belasco, S. N. Cohen, and A. von Gabain. 1984. Growth-rate dependent regulation of mRNA stability in Escherichia coli. Nature 312:75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noll, M., B. Hapke, M. H. Schreier, and H. Noll. 1973. Structural dynamics of bacterial ribosomes. I. Characterization of vacant couples and their relation to complexed ribosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 75:281-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Hara, E. B., J. A. Chekanova, C. A. Ingle, Z. R. Kushner, E. Peters, and S. R. Kushner. 1995. Polyadenylylation helps regulate mRNA decay in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1807-1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabussay, D., and W. Zillig. 1969. A rifampicin resistant RNA-polymerase from E. coli altered in the beta-subunit. FEBS Lett. 5:104-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talukder, A. A., and A. Ishihama. 1999. Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33105-33113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsui, H. C., G. Feng, and M. E. Winkler. 1997. Negative regulation of mutS and mutH repair gene expression by the Hfq and RpoS global regulators of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 179:7476-7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanzo, N. F., Y. S. Li, B. Py, E. Blum, C. F. Higgins, L. C. Raynal, H. M. Krisch, and A. J. Carpousis. 1998. Ribonuclease E organizes the protein interactions in the Escherichia coli RNA degradosome. Genes Dev. 12:2770-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogel, H. J., and D. M. Bonner. 1956. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vytvytska, O., J. S. Jakobsen, G. Balcunaite, J. S. Andersen, M. Baccarini, and A. von Gabain. 1998. Host factor I, Hfq, binds to Escherichia coli ompA mRNA in a growth rate-dependent fashion and regulates its stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14118-14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachi, M., A. Takada, and K. Nagai. 1999. Overproduction of the outer-membrane proteins FepA and FhuE responsible for iron transport in Escherichia coli hfq::cat mutant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 264:525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada, A., Y. Yamazaki, N. Fujita, and A. Ishihama. 1990. Structure and probable genetic location of a “ribosome modulation factor” associated with 100S ribosomes in stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2657-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wada, A., K. Igarashi, S. Yoshimura, S. Aimoto, and A. Ishihama. 1995. Ribosome modulation factor: stationary growth phase-specific inhibitor of ribosome functions from Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 214:410-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wada, A. 1998. Growth phase coupled modulation of Escherichia coli ribosomes. Genes Cells 3:203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamagishi, M., H. Matsushima, A. Wada, M. Sakagami, N. Fujita, and A. Ishihama. 1993. Regulation of the Escherichia coli rmf gene encoding the ribosome modulation factor: growth phase- and growth rate-dependent control. EMBO J. 12:625-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yonesaki, T. 2002. Scarce adenylation in bacteriophage T4 mRNAs. Genes Genet. Syst. 77:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida, H., Y. Maki, H. Kato, H. Fujisawa, K. Izutsu, C. Wada, and A. Wada. 2002. The ribosome modulation factor (RMF) binding site on the 100S ribosome of Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 132:983-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida, H., H. Yamamoto, T. Uchiumi, and A. Wada. 2004. RMF inactivates ribosomes by covering the peptidyl transferase centre and entrance of peptide exit tunnel. Genes Cells 9:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]