Abstract

Cell extracts of the proteolytic, hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus contain high specific activity (11 U/mg) of lysine aminopeptidase (KAP), as measured by the hydrolysis of l-lysyl-p-nitroanilide (Lys-pNA). The enzyme was purified by multistep chromatography. KAP is a homotetramer (38.2 kDa per subunit) and, as purified, contains 2.0 ± 0.48 zinc atoms per subunit. Surprisingly, its activity was stimulated fourfold by the addition of Co2+ ions (0.2 mM). Optimal KAP activity with Lys-pNA as the substrate occurred at pH 8.0 and a temperature of 100°C. The enzyme had a narrow substrate specificity with di-, tri-, and tetrapeptides, and it hydrolyzed only basic N-terminal residues at high rates. Mass spectroscopy analysis of the purified enzyme was used to identify, in the P. furiosus genome database, a gene (PF1861) that encodes a product corresponding to 346 amino acids. The recombinant protein containing a polyhistidine tag at the N terminus was produced in Escherichia coli and purified using affinity chromatography. Its properties, including molecular mass, metal ion dependence, and pH and temperature optima for catalysis, were indistinguishable from those of the native form, although the thermostability of the recombinant form was dramatically lower than that of the native enzyme (half-life of approximately 6 h at 100°C). Based on its amino acid sequence, KAP is part of the M18 family of peptidases and represents the first prokaryotic member of this family. KAP is also the first lysine-specific aminopeptidase to be purified from an archaeon.

Aminopeptidases are exopeptidases that catalyze the removal of amino acid residues at the N termini of peptides and proteins. Intracellular proteolytic degradation by aminopeptidases is necessary for modulation of protein concentrations, maintenance of amino acid pools, and removal of damaged proteins (17). In addition, aminopeptidases have more specific functions, including activation (10) and inactivation (21) of biologically active peptides and the removal of N-terminal methionyl residues of newly synthesized proteins. The breakdown of proteinaceous substrates, whether imported into the cell or generated from damaged proteins, are further degraded by di-, tri-, and carboxypeptidases, as well as by aminopeptidases (17). Classification of aminopeptidases has been generally based upon their substrate specificities, such as preference for a neutral, acidic, or basic amino acid in the P1 position of the amino terminus of peptides (44). In recent years, more focus has been placed on classifying peptidases based on structural analyses (35). Aminopeptidases are widely distributed among eukaryotes and prokaryotes, although only a few have been isolated from archaea (37). About two-thirds of all aminopeptidases are represented by the metal-dependent peptidases in which zinc is the most frequently associated metal (34).

Hyperthermophilic archaea are potentially rich sources of peptidase-type enzymes, because most of them are capable of using protein-based substrates as their sole carbon source (1). For example, Pyrococcus furiosus grows optimally at 100°C, utilizing proteins and peptides as substrates, and it produces organic acids, CO2, and H2. Several enzymes involved in the catabolism of peptides have been purified from P. furiosus, including aminotransferases (4), 2-keto acid oxidoreductases (2, 19), glutamate dehydrogenase (1), prolidase (16), acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetases (29), aminoacylase (39), a cobalt-activated carboxypeptidase (11), and pyrollidone carboxypeptidase (42). This list also includes a methionine aminopeptidase (41) and a deblocking aminopeptidase (DAP) (40) as well as another type of aminopeptidase from the related archaeon P. horikoshii (3). The P. furiosus genome contains a gene (PF0369) encoding a homolog of the latter P. horikoshii enzyme, with which it has 85% identity. There are no reports on its biochemical and kinetic properties, so a comparison between it and P. furiosus DAP, with which it has 42% sequence identity, cannot be made.

In this paper we focus on aminopeptidases that catalyze the release of lysyl residues from the N terminus of peptides. Surprisingly, such an enzyme has not been characterized previously from an archaeon. Moreover, several so-called lysyl aminopeptidases have been characterized from bacteria, and these are represented by the aminopeptidase N family of enzymes. However, these typically hydrolyze a broad range of peptides and are not specific for basic amino acids (25, 32). On the other hand, three lysyl-specific aminopeptidases have been characterized from eukaryotic sources: the native form of a cobalt-dependent enzyme, yscCo-II, from the unicellular eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae (20), the native enzyme from the yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus (33), and a recombinant form of a zinc-dependent enzyme from the filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger (6). The majority of aminopeptidases characterized so far, including the S. cerevisiae and A. niger enzymes, belong to the large M1 family of metallopeptidases. These typically require zinc for activity, and their sequences contain the zinc-binding motif HEXXH (6). Sequence analyses of the M1 metalloaminopeptidases show that they consist of three main groups (34). These include the aminopeptidase N and the leukotriene A4 hydrolase groups, members of which have been extensively characterized. The third group consists of a variety of aminopeptidases that share high sequence similarity but differ considerably in their catalytic properties and other characteristics (34).

The object of the present study was to characterize the lysine aminopeptidase (KAP) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, P. furiosus. It is shown that the P. furiosus enzyme, while having the same narrow substrate specificity as the KAPs from S. cerevisiae and A. niger, contains conserved sequences that are homologous to those of members of the M18 rather than M1 family of peptidases. In contrast to the large M1 family, only two members of the M18 family have been characterized. These are a leucyl aminopeptidase from yeast (30) and an aspartyl aminopeptidase from rabbit (44). Herein we therefore report the isolation of the first KAP from an archaeon, in the form of the P. furiosus enzyme, which is also the first prokaryotic member of the M18 family. The native and recombinant forms of P. furiosus KAP were purified, and their biochemical properties were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of microorganisms.

P. furiosus (DSM 3638) was grown at 95°C in a 600-liter fermentor with maltose as the carbon source as previously described (8). Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (LB). Kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (35 μg/ml) were added as needed for plasmid maintenance.

Enzyme assays.

Lysine aminopeptidase activity was determined with the chromogenic substrate l-lysyl-p-nitroanilide (Lys-pNA). The assay mixture (350 μl) containing the enzyme sample in 50 mM MOPS [3-(N-morpholine) propane sulfonic acid] buffer (pH 8.0) and 15 mM Lys-pNA (Bachem Co., King of Prussia, Pa.) was incubated at 100°C for 5 min, and 70 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (10%, wt/vol) was added to stop the reaction. The final volume was made up to 820 μl using deionized H2O, and the absorption was measured at 405 nm (27). The amount of p-nitroaniline produced was calculated from a standard curve. One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1 μmol of p-nitroaniline per min under these assay conditions.

Peptidase activity was determined by the release of amino acids from peptides using a modified ninhydrin assay. The ninhydrin reagent contained 0.8 g of ninhydrin in 80 ml of 99.5% ethanol and 10 ml of acetic acid, to which 1 g of CdCl2 dissolved in 1 ml of water was added (13). The assay mixture (200 μl) containing the enzyme sample in 50 mM MOPS (pH 8.0) and the indicated di-, tri-, or tetrapeptide (Bachem Co.) was incubated at 100°C for 5 min in vials sealed with serum stoppers, and then 1.5 ml of the Cd-ninhydrin reagent was added. The solution was heated for 5 min at 84°C, and after cooling the absorbance was measured at 507 nm. One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that hydrolyzes 1 μmol of lysine per min under these assay conditions.

Purification of P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase.

Lysine aminopeptidase was purified from P. furiosus under anaerobic conditions at 23°C. Frozen cells (100 g [wet weight]) were thawed in 300 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing DNase I at 37°C for 2 h. A cell extract was obtained by ultracentrifugation at 18,000 × g for 2 h. The supernatant (300 ml) was applied to a column (10 by 14 cm) of DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.), equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 2 mM sodium dithionate (Tris-DT buffer). The column was eluted at a flow rate of 10 ml/min with a 2.5-liter linear gradient from 0 to 1.0 M NaCl in the same Tris-DT buffer. Lysine aminopeptidase activity was eluted from 0.29 to 0.39 M NaCl. The active fractions were combined (300 ml), and sodium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1.0 M. This solution was applied to a column (3.5 by 10 cm) of phenyl sepharose (Pharmacia) equilibrated with Tris-DT buffer containing 1 M sodium sulfate. The column was eluted with a gradient (1 liter) from 1.0 to 0 M sodium sulfate in the Tris-DT buffer at a flow rate of 7 ml/min. Lysine aminopeptidase activity eluted as 0.50 to 0.57 M sodium sulfate. The lysine aminopeptidase-containing fractions (120 ml) were applied to a column (1 by 10 cm) of hydroxyapatite (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The column was eluted at a flow rate of 5 ml/min with a 100-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M potassium phosphate buffer. The active fractions from the hydroxyapatite were applied to a column (1.6 by 60 cm) of Superdex-200 (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-DT buffer (pH 8.0) containing 0.5 M NaCl at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. Fractions containing lysine aminopeptidase activity were concentrated by ultrafiltration and stored as frozen pellets in liquid nitrogen until required.

Cloning and expression of the lysine aminopeptidase-encoding gene.

The gene encoding P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase was obtained by PCR amplification using genomic DNA and was subsequently cloned into the modified T7 polymerase expression vector pET-24d (Novagen, Milwaukee, Wis.). For amplification, the forward primer (CACCGGATCCGTAGATTGGGAACTAATGAAA; MWG, High Point, N.C.) contained an engineered BamHI site, while the reverse primer (AAGCTCGAGCGGCCGCTCACGGTGTAAAGTCCATTGGCTTTA)had an engineered NotI site. PCR amplification was performed with cloned P. furiosus DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and a Robocycler 40 (Stratagene) programmed with an initial denaturation of 4 min, followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 3 min. The PCR fragment (1.06 kb) was cleaned from the reaction mixture using a PCR cleanup kit (TeleChem, Sunnyvale, Calif.), digested with BamHI and NotI, and cloned into the modified pET-24d vector. Plasmid pET-24d was modified such that a polyhistidine fusion tag of MAHHHHHHXX was placed at the N terminus. Alanine in the second position results in complete removal of the N-terminal methionine by the endogenous E. coli methionine aminopeptidase (5). The ligation mixture (3 μl) was used to transform E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). After screening for the presence of the gene by restriction digestion, the plasmid was transformed into the expression host BL21(DE3)Star (Invitrogen) containing the pRIL vector (Stratagene). The expression of the gene encoding lysine aminopeptidase was induced with isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (0.4 mM) when the culture reached an optical density of 0.6. The induced culture was incubated for 3 h prior to harvesting of the cells.

Purification of recombinant lysine aminopeptidase.

Recombinant lysine aminopeptidase was purified in two steps. IPTG-induced BL21(λDE3)Star/pRIL cells that had been harvested from a 1-liter culture were suspended in 30 ml of 10 mM imidazole buffer (pH 8.0), containing 10 mM sodium phosphate and 0.5 mM NaCl. The cells were lysed by sonication for 5 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was applied to a column (1.6 by 3 cm) of Co2+-Talon affinity (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) that was equilibrated with 10 mM imidazole buffer (pH 8.0). The lysine aminopeptidase was eluted with 300 mM imidazole buffer (pH 8.0) and was then heated for 5 min at 70°C in the presence of 0.2 mM CoCl2. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 10 min), and the supernatant was concentrated by ultrafiltration. The purified enzyme was stored in liquid nitrogen until required.

Other methods.

Molecular weights were estimated by gel filtration with a column (1 by 27 cm) of Superdex 200 (Pharmacia) with amylase (200,000), alcohol dehydrogenase (150,000), and bovine serum albumin (66,000) as standard proteins. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-gel electrophoresis was performed using 12.5% polyacrylamide by the method of Laemmli (28). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (7) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. To determine metal content, exogenous metal ions were removed from the lysine aminopeptidase by gel filtration using a G-25 column equilibrated with 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 8.0). A metal analysis (20 elements) was obtained by plasma emission spectroscopy with a Thermo Jarrell-Ash Enviro 36 Inductively Coupled Argon Plasma instrument at the Chemical Analysis Laboratory of the University of Georgia. Subunit molecular weight analyses of the native and recombinant lysine aminopeptidase were determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) using an Applied Biosystems syringe pump high-performance liquid chromatography system and the Perkin Elmer Sciex API I Plus Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer at the Chemical and Biological Sciences Mass Spectrometry Facility of the University of Georgia.

RESULTS

Purification of the native P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase. Cell extracts contained a significant amount of lysine aminopeptidase activity (approximately 11 U/mg at 100°C) using Lys-pNA as the substrate. Lysine aminopeptidase was purified to apparent homogeneity by four chromatography steps. All cells used for purification were obtained from cell cultures grown on a 500-liter scale. The procedure was carried out under anaerobic conditions, not because the lysine aminopeptidase was oxygen sensitive but to allow the purification of other enzymes that are oxygen sensitive from the same batch of P. furiosus cells.

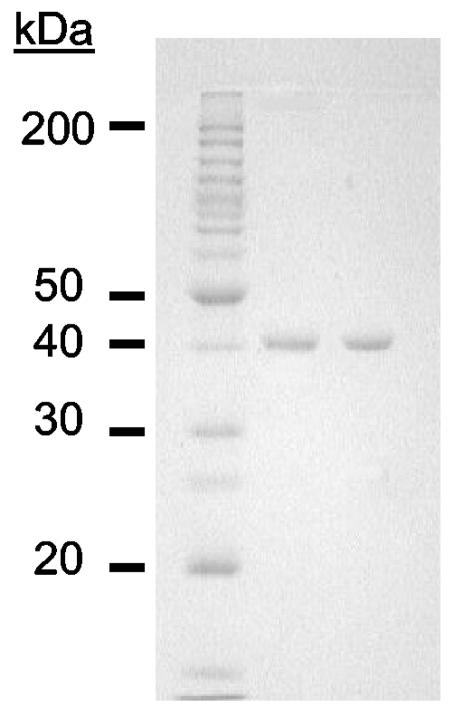

Lysine aminopeptidase activity was only found in the soluble fraction, indicating that it is a cytoplasmic protein. The enzyme was purified 170-fold with a yield of 28% and a specific activity of approximately 1,900 U/mg (Table 1). On a denaturing electrophoresis gel, the purified enzyme migrated as a single major band corresponding to a molecular mass of approximately 40 kDa (Fig. 1). Tryptic digestion of the purified protein was used to identify a gene (PF1861) in the P. furiosus genome (http://comb5-156.umbi.umd.edu/genemate) that is, in fact, annotated as an endoglucanase. Analyses of a sample of the purified enzyme by LC-MS indicated a molecular mass of 38,210 Da. This value is in good agreement with that (38,214 Da) calculated from the amino acid sequence (390 residues) deduced from PF1861. Lysine aminopeptidase was eluted from a gel filtration column with at molecular mass corresponding to 160 ± 10 kDa. This result, together with the electrophoretic and LC-MS data, suggests that the enzyme is a homotetramer. A mass of 38.21 kDa for the lysine aminopeptidase subunit was used in all calculations.

TABLE 1.

Purification of lysine aminopeptidase from P. furiosus

| Step | Activitya (U) | Protein (mg) | Sp. act. (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 28,700 | 2,600 | 11 | 1 | 100 |

| DEAE | 14,500 | 495 | 29 | 2.7 | 51 |

| Phenyl sepharose | 11,500 | 27 | 419 | 38 | 40 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 7,051 | 8.7 | 810 | 74 | 25 |

| Superdex 200 | 8,045 | 4.3 | 1,900 | 170 | 28 |

Activity was measured at 100°C by using Lys-pNA (10 mM) as the substrate.

FIG. 1.

SDS—12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the lysine aminopeptidase purified from P. furiosus. Lane 1, standard molecular size markers; lane 2, native lysine aminopeptidase (4 μg); lane 3, recombinant lysine aminopeptidase (4 μg).

Purification of recombinant P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase.

The gene encoding lysine aminopeptidase protein was successfully expressed in E. coli cells by the addition of IPTG after a 4-h period of induction at 37°C. The presence of recombinant enzyme in cell extracts of E. coli was evident by both by high-temperature (100°C) enzyme assays as well as by the appearance of a protein band corresponding to a mass of 38 kDa after SDS-gel analysis of cell extracts (data not shown). The specific activity of the lysine aminopeptidase in the recombinant E. coli cells was approximately 207 U/mg, which is approximately 20-fold greater than the activity in cell extracts of P. furiosus measured under the same conditions at 100°C. The results of a typical purification of the recombinant enzyme are summarized in Table 2. It was purified in two steps using affinity chromatography and a heat treatment step. The recombinant form of lysine aminopeptidase (r-KAP) was indistinguishable from the native protein (n-KAP) purified from P. furiosus when analyzed by SDS-gel electrophoresis, even though the recombinant enzyme contains a His6 tag. LC-MS analysis indicated a subunit molecular mass of 39,128 Da for r-KAP. This value is in good agreement with the calculated molecular size of 39,121 (which includes the His6 tag).

TABLE 2.

Purification of recombinant lysine aminopeptidase

| Step | Activitya (U) | Protein (mg) | Sp. act. (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 43,800 | 202 | 217 | 1 | 100 |

| Co2+-talon affinity | 30,700 | 28 | 1,100 | 5 | 70 |

| Heat treatment | 53,100 | 24 | 2,200 | 10 | 120 |

Activity was measured at 100°C by using Lys-pNA (10 mM) as the substrate.

Catalytic properties of native and recombinant lysine aminopeptidases.

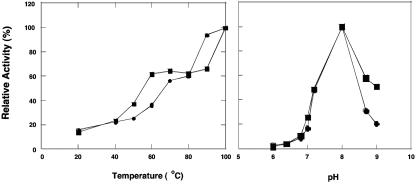

Both the native (n-KAP) and recombinant (r-KAP) forms had comparable specific activities in the standard assay (470 and 525 U/mg, respectively) in their purified states. However, the activities of both were stimulated by approximately fourfold (to 1,900 and 2,100 U/mg, respectively) by the presence of 0.2 mM Co2+ ions in the assay medium, and these were included in all assays unless otherwise noted. The apparent association constant for Co2+ was 0.01 mM for n-KAP and 0.0025 mM for r-KAP. When n-KAP was preincubated with 0.2 mM Co2+ ions and then assayed in the absence of the metal, there was no difference in specific activity (compared to standard conditions where Co2+ ions are included in the assay mixture). However, when the sample was preincubated with 0.2 mM Co2+ ions and subjected to gel filtration, only 10% of the activity remained, while addition of Co2+ ions (0.2 mM) to the reaction mixture completely restored enzyme activity. Co2+ ions could not be replaced with other divalent (Ca2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, or Zn2+) or monovalent cations (Na+ or K+) when used at concentrations of up to 0.2 mM. The activities of n-KAP and r-KAP also showed the same responses to temperature and pH (Fig. 2). Each had a pH optimum at 8.0 and a temperature optimum of ≥100°C. Surprisingly, both forms exhibited at 25°C approximately 15% of their activity at 100°C. Lys-pNA was used as the substrate in all routine assays, and the activities of the native and recombinant forms were investigated. As shown in Table 3, both forms of the enzyme were active only with basic and, to a lesser extent, nonpolar residues at the N terminus using the nitroanilide substrates. In addition, as shown in Table 4, KAP hydrolyzes a variety of di-, tri-, and tetrapeptides with Lys at the N terminus, and various amino acids can occupy the second position (Gly, Lys, Ala, Phe, Glu). As expected, the native and recombinant enzymes have comparable activities with the various substrates (Table 4). Kinetic analyses were carried out for both enzyme forms, using Lys-pNA and Lys-Gly-Gly as substrates. All combinations of enzymes and substrates showed normal Michaelis-Menten-type kinetics, and the kinetic constants shown in Table 5 were calculated from the linear double-reciprocal plots. The results are comparable for both enzymes and both substrates, with Km values in the range of 2 to 4 mM and Vmax values approaching 3,000 U/mg. r-KAP had a slightly higher affinity for Arg-pNA but exhibited slightly lower levels of activity (Table 5).

FIG. 2.

Effects of temperature and pH on P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase activity. The assay mixture contained lysine aminopeptidase (0.047 mg/ml) and lysine-pNA (10 mM) in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0. For the effects of pH, the following buffers (each at 50 mM) were used at the indicated pH: Bis-Tris, pH 6.0, 6.5, and 6.8; MOPS, pH 7.0, 7.2, and 8.0; 2-(N-cyclohexlamino)ethanesulfonic acid (CHES), pH 8.6 and 9.0. For effects of temperature, the buffer used was 50 mM MOPS (pH 8.0). Activity of 100% corresponds to 1,900 and 2,200 U/mg for native (squares) and recombinant (circles) KAP, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Substrate specificity of native and recombinant P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase

| Substratea (with p-nitroanilide amino acids) | % Relative activityb for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| n-KAP | r-KAP | |

| Lys-pNA | 100 | 100 |

| Arg-pNA | 34 | 47 |

| Leu-pNA | 0 | 7 |

| Pro-pNA | 0 | 6 |

| Ala-pNA | 0 | 3 |

| Gly-pNA | 4 | 0.7 |

| His-pNA | 5 | 0 |

| Phe-pNA | 14 | 0 |

| Ac-Phe-pNA | 4 | 0 |

All substrates were used at a final concentration of 10 mM.

The rate of hydrolysis is expressed as a percentage of the activity compared to that obtained by using Lys-pNA as the substrate at 100°C, where 100% activity corresponds to 1,900 and 2,200 U/mg for native and recombinant KAP, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Substrate specificity of native and recombinant P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase for peptides

| Substratea | % Relative activityb for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| n-KAP | r-KAP | |

| Lys-Gly-Gly | 100 | 100 |

| Lys-Lys-Lys | 89 | 63 |

| Lys-Ala-Pro | 85 | 70 |

| Lys-Lys-Lys-Lys | 57 | 27 |

| Lys-Phe | 53 | 52 |

| Lys-Glu-Glys | 48 | 50 |

| Lys-Leu | 42 | 77 |

| Lys-Ala | 35 | 47 |

| Lys-Gly-Gly-Lys | 22 | 50 |

All substrates were used at a final concentration of 1mM.

The rate of hydrolysis is expressed as a percentage of the activity compared to that obtained by using Lys-Gly-Gly as the substrate at 100°C, where 100% activity corresponds to 677 and 906 U/mg for native and recombinant KAP, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Kinetic parameters for substrates of P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase

| KAP | Substratea | Km (mM) | Vmax (μmol/min/mg) | kcatb (s−1) | kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-KAP | Lys-pNA | 4.6 | 2,900 | 1,260 | 274 |

| Lys-Gly-Gly | 1.8 | 677 | 305 | 169 | |

| r-KAP | Lys-pNA | 4.0 | 2,870 | 1,840 | 460 |

| Lys-Gly-Gly | 2.7 | 2,300 | 1,460 | 540 | |

| Arg-pNA | 1.4 | 1,200 | 769 | 550 |

All assays were carried out at 100°C in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0.

Based on a molecular mass of 38.2 kDa.

Physical properties of native and recombinant lysine aminopeptidases.

The metal contents of both n-KAP and r-KAP were determined by plasma emission spectroscopy. Surprisingly, of the 20 elements that were analyzed, zinc was the only one present in significant amounts. n-KAP contained 1.8 ± 0.48 g-atom/subunit, whereas the r-KAP contained 2.3 ± 0.48 g-atom/subunit. When n-KAP and r-KAP (0.31 and 0.53 mg/ml, respectively, in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0) were treated with EDTA (20 mM) for 1 h at 23°C and then subjected to gel filtration, there was no significant loss in the activity with either form of the enzyme. When either form (0. 047 μg/ml in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0) was heated at 100°C for 5 min with EDTA (20 mM), there was an approximate 40% decrease in activity. None of the divalent (Ca2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, or Zn2+) or monovalent (Na+ or K+) cations that were tested had any effect on the residual activity. When either enzyme form (0.047 μg/ml in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0) was incubated with o-phenanthroline (20 mM) at 100°C for 5 min, no activity was detected. When the same sample was then incubated with 0.4 mM CoCl2 in the standard assay, only 40% of the total activity was restored, but no activity was recovered if CoCl2 was replaced by ZnCl2. The native lysine aminopeptidase was very thermostable. When a sample (0.047 μg/ml in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0) was incubated at 100°C, the time required for a 50% loss of activity was 6 h. However, r-KAP (0.047 μg/ml in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0) lost 50% of its activity after a 10-min incubation under the same conditions. Interestingly, the presence of 0.2 mM CoCl2 dramatically increased the thermostability of r-KAP (0.047 μg/ml in 50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0) such that its half-life value (6 h) was comparable to that of the native enzyme.

DISCUSSION

P. furiosus contains significant lysine aminopeptidase activity in its cytoplasm, and this appears to be catalyzed by a single enzyme. It has a strong preference for peptides containing a lysyl or arginyl residue at the N terminus of di- and tripeptides, with dramatically lower activity with nonpolar residues (Ala, Leu, Phe). The relatively high Km values (2.0 mM) for such basic substrates indicate that such peptides may be present at significant intracellular levels in vivo. The gene (PF1861) encoding the enzyme was expressed in E. coli, and the properties of the recombinant form, including temperature and pH dependence of activity as well as substrate specificity, were indistinguishable from that of the native enzyme. In fact, the only significant difference is that the recombinant form was considerably less thermostable than the native enzyme, suggesting that it may not be completely folded (even though its catalytic properties were virtually identical). There is another example of a recombinant form of peptidase from P. furiosus (prolidase, in this case, lacking a poly-His tag) that is not as thermally stable as the native enzyme (16). The recombinant form of KAP was stabilized at high temperature by Co2+ ions, but these destabilized the native form at 100°C, the reasons for which are unclear at this point. The native and recombinant forms of KAP each contain two zinc ions per subunit. These are essential for activity, as they were lost upon incubation with chelators such as EDTA and o-phenanthroline. Activity could only be restored upon addition of Co2+ ions, whereas Zn2+ ions had no effect. Addition of Co2+ ions to the purified native and recombinant enzymes resulted in a significant stimulation (fourfold) of activity, but the role of cobalt has yet to be determined.

Lysine aminopeptidases with substrate specificities similar to that of the P. furiosus enzyme have not been reported from any prokaryote; they have only been found in the fungi A. niger (6), S. cerevisiae (20), and K. marxianus (33). The S. cerevisiae enzyme, like that of P. furiosus, is also stimulated by Co2+ ions (0.5 mM); however, the A. niger and K. marxianus enzymes do not require added metal ions. S. cerevisiae and A. niger have 68% sequence similarity with each other and belong to the M1 family of metalloaminopeptidases (the sequence of the K. marxianus enzyme has not been reported). This family also includes two other yeast enzymes, leucine aminopeptidase I and alanyl aminopeptidase I. However, the sequence of the P. furiosus enzyme shows very little sequence similarity to any of these proteins. Rather, it shows low similarity (27 and 22%) to two members of the M18 family of proteases, rabbit aspartyl aminopeptidase (44) and yeast aminopeptidase I (30). These two eukaryotic enzymes are both metalloenzymes and show approximately 43% sequence similarity with each other. So far they are the only two members of this family that have been characterized. The nature of the metal site in these M18 aminopeptidases is not known, because these enzymes lack the classical signature sequence (HEXXH) for zinc metallopeptidases. Their catalytic sites are thought to contain four conserved histidine residues (43), and, interestingly, sequence alignments show that three of them are also found in the P. furiosus enzyme (Fig. 3). There are other residues conserved in all three enzymes, including (using the P. furiosus notation) Glu/Asp88, Asp135, Asp305, Glu342, Glu343, and Asp388, and these may also be involved in catalysis. Clearly, structural analyses of the P. furiosus enzyme are required to determine the role of these residues. To this end, samples of the P. furiosus enzyme have been crystallized, and the crystals diffract at 2.2 angstroms (B. C. Wang, unpublished data). It will be interesting to see if the structure of this lysine aminopeptidase proves to be novel, as there are no analogs of this enzyme in the protein database at present.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the amino acid sequence of P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase with other aminopeptidases of the M18 family, yeast aminopeptidase I (AAA34738), and mouse aspartyl aminopeptidase (NP_058574). Conserved histidine, aspartate, and glutamate residues are boxed. Residues that are believed to play a role in metal binding are denoted by asterisks.

Metal analyses indicated that neither the native nor recombinant forms of P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase contain Co2+ as purified. However, the ability of the enzyme to be activated by Co2+ ions suggests that an active form containing a Co-Zn binuclear center may be possible. It will be interesting to see what the structural analyses reveal about this site. Such an exchange of divalent cations has been observed in certain leucine aminopeptidases (LAPs) (18, 23, 31). These particular enzymes are hexameric and contain two zinc-binding sites per subunit in which the first site, site 1, readily exchanges Zn2+ for other divalent cations, including Mn2+, Mg2+, and Co2+. On the other hand, site 2 binds the second Zn2+ more strongly, thereby allowing the exchange of Zn2+ for other cations in site 1 but not site 2 (31). Hence, such an exchange of metals may be occurring in the P. furiosus KAP. This also contains two zinc atoms per subunit, and perhaps the enzyme becomes much more active when treated with Co2+, because this replaces one of the Zn atoms. Further metal binding studies, in combination with structural analyses, will be needed to address this issue.

The lysine aminopeptidase from P. furiosus is the first such enzyme of the M18 family to be purified from a prokaryote, a hyperthermophile, or an archaeon. As expected, the P. furiosus enzyme is very thermostable, with a temperature optimum above 100°C and no loss of activity after 6 h. The thermostability of the other members of the M18 family, yeast aminopeptidase I and rabbit aspartyl aminopeptidase, were not reported. Although the sizes of their subunits are similar to that of the P. furiosus enzyme, they form much larger complexes. These are 640 and 440 kDa, respectively (44), compared to 160 kDa for P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase. Yeast aminopeptidase I has been characterized as a dodecameric protein, whereas the rabbit aspartyl aminopeptidase appears to be octameric (30, 44).

The sequence of P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase shows similarity to genes encoding two putative proteins in the genome sequences of P. horikoshii and P. abysii. Although these proteins have not yet been characterized, they are likely to also be members of the M18 family of metallopeptidases. Homologs of P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase are also present in the genome sequences of other archaea, including those of Methanococcus jannaschii (9), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicus (38), Methanosarcina mazei (12), Methanosarcina acetivorans (15), Pyrobaculum aerophilum (14), Methanococcus maripaludis (24), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (26), Methanopyrus kandeleri (37), and Aeropyrum pernix (22), all of which have 50 to 60% overall sequence similarity to the P. furiosus KAP. Aminopeptidases are known to be involved in degradation of cellular proteins for controlling protein concentrations, maintaining amino acid pools, and removing damaged proteins (1). In addition, they may also be involved in the breakdown of proteinaceous growth substrates. Interestingly, homologs of the P. furiosus lysine aminopeptidase are found in all heterotrophic archaea capable of utilizing peptides as a carbon source (P. furiosus, P. horikoshii, P. abysii, P. aerophilum [also autotrophic], and A. pernix) as well as autotrophic archaea (M. jannaschii, M. thermoautotrophicus, M. mazei, M. acetivorans, M. maripaludis, and M. kandleri). These findings indicate that the enzyme may function intracellularly to break down proteinaceous growth substrates in addition to carrying out proteolytic degradation of the organisms' own cellular proteins. A dual role is consistent with the results of recent whole-genome DNA microarray analyses, in which P. furiosus was grown using maltose or peptides as the primary carbon source (36). There was no significant change in gene expression or in the specific activity of lysine aminopeptidase under either condition. Therefore, the enzyme is expressed at a significant level when a carbohydrate is the carbon source, indicating a role in the degradation of cellular proteins, and presumably also plays a role in the degradation of peptides when they are used as the primary source of carbon, although a further increase in expression appears not to be required.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (BES-0317911) and the National Institutes of Health (GM 62407).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. W. 1999. The biochemical diversity of life near and above 100°C in marine environments. J. Appl. Microbiol. Symp. Suppl. 85:108S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, M. W., and A. Kletzin. 1996. Oxidoreductase-type enzymes and redox proteins involved in fermentative metabolisms of hyperthermophilic Archaea. Adv. Protein Chem. 48:101-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando, S., K. Ishikawa, H. Ishida, Y. Kawarabayasi, H. Kikuchi, and Y. Kosugi. 1999. Thermostable aminopeptidase from Pyrococcus horikoshii. FEBS Lett. 447:25-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreotti, G., M. V. Cubellis, G. Nitti, G. Sannia, X. Mai, M. W. Adams, and G. Marino. 1995. An extremely thermostable aromatic aminotransferase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1247:90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arfin, S. M., and R. A. Bradshaw. 1988. Cotranslational processing and protein turnover in eukaryotic cells. Biochemistry 27:7979-7984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basten, D. E. J. W., J. Visser, and P. J. Schaap. 2001. Lysine aminopeptidase of Aspergillus niger. Microbiology. 147:2045-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant, F. O., and M. W. Adams. 1989. Characterization of hydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 264:5070-5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bult, C. J., O. White, G. J. Olsen, L. Zhou, R. D. Fleischmann, G. G. Sutton, J. A. Blake, L. M. FitzGerald, R. A. Clayton, J. D. Gocayne, A. R. Kerlavage, B. A. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, M. D. Adams, C. I. Reich, R. Overbeek, E. F. Kirkness, K. G. Weinstock, J. M. Merrick, A. Glodek, J. L. Scott, N. S. Geoghagen, and J. C. Venter. 1996. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. Science 273:1058-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadel, S., A. R. Pierotti, T. Foulon, C. Creminon, N. Barre, D. Segretain, and P. Cohen. 1995. Aminopeptidase-B in the rat testes: isolation, functional properties and cellular localization in the seminiferous tubules. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 110:149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng, T. C., V. Ramakrishnan, and S. I. Chan. 1999. Purification and characterization of a cobalt-activated carboxypeptidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Protein Sci. 8:2474-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deppenmeier, U., A. Johann, T. Hartsch, R. Merkl, R. A. Schmitz, R. Martinez-Arias, A. Henne, A. Wiezer, S. Baumer, C. Jacobi, H. Bruggemann, T. Lienard, A. Christmann, M. Bomeke, S. Steckel, A. Bhattacharyya, A. Lykidis, R. Overbeek, H. P. Klenk, R. P. Gunsalus, H. J. Fritz, and G. Gottschalk. 2002. The genome of Methanosarcina mazei: evidence for lateral gene transfer between bacteria and archaea. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:453-461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doi, E., S. Daisuke, and T. Matoba. 1981. Modified colorimetric ninhydrin methods for peptidase assay. Anal. Biochem. 118:173-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitz-Gibbon, S. T., H. Ladner, U. J. Kim, K. O. Stetter, M. I. Simon, and J. H. Miller. 2002. Genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:984-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galagan, J. E., C. Nusbaum, A. Roy, M. G. Endrizzi, P. Macdonald, W. FitzHugh, S. Calvo, R. Engels, S. Smirnov, D. Atnoor, A. Brown, N. Allen, J. Naylor, N. Stange-Thomann, K. DeArellano, R. Johnson, L. Linton, P. McEwan, K. McKernan, J. Talamas, A. Tirrell, W. Ye, A. Zimmer, R. D. Barber, I. Cann, D. E. Graham, D. A. Grahame, A. M. Guss, R. Hedderich, C. Ingram-Smith, H. C. Kuettner, J. A. Krzycki, J. A. Leigh, W. Li, J. Liu, B. Mukhopadhyay, J. N. Reeve, K. Smith, T. A. Springer, L. A. Umayam, O. White, R. H. White, E. Conway de Macario, J. G. Ferry, K. F. Jarrell, H. Jing, A. J. Macario, I. Paulsen, M. Pritchett, K. R. Sowers, R. V. Swanson, S. H. Zinder, E. Lander, W. W. Metcalf, and B. Birren. 2002. The genome of M. acetivorans reveals extensive metabolic and physiological diversity. Genome Res. 12:532-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh, M., A. M. Grunden, D. M. Dunn, R. Weiss, and M. W. Adams. 1998. Characterization of native and recombinant forms of an unusual cobalt-dependent proline dipeptidase (prolidase) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 180:4781-4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzales, T., and J. Robert-Baudouy. 1996. Bacterial aminopeptidases: properties and functions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 18:319-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu, Y. Q., F. M. Holzer, and L. L. Walling. 1999. Overexpression, purification and biochemical characterization of the wound-induced leucine aminopeptidase of tomato. Eur. J. Biochem. 263:726-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heider, J., X. Mai, and M. W. Adams. 1996. Characterization of 2-ketoisovalerate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, a new and reversible coenzyme A-dependent enzyme involved in peptide fermentation by hyperthermophilic archaea. J. Bacteriol. 178:780-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrera-Camacho, I., R. Morales-Monterrosas, and R. Quiroz-Alvarez. 2000. Aminopeptidase yscCo-II: a new cobalt-dependent aminopeptidase from yeast-purification and biochemical characterization. Yeast 16:219-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersh, L. B., N. Aboukhair, and S. Watson. 1987. Immunohistochemical localization of aminopeptidase M in rat brain and periphery: relationship of enzyme localization and enkephalin metabolism. Peptides 8:523-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawarabayasi, Y., Y. Hino, H. Horikawa, S. Yamazaki, Y. Haikawa, K. Jin-no, M. Takahashi, M. Sekine, S. Baba, A. Ankai, H. Kosugi, A. Hosoyama, S. Fukui, Y. Nagai, K. Nishijima, H. Nakazawa, M. Takamiya, S. Masuda, T. Funahashi, T. Tanaka, Y. Kudoh, J. Yamazaki, N. Kushida, A. Oguchi, H. Kikuchi, et al. 1999. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper-thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernix K1. DNA Res. 6:83-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, H., and W. N. Lipscomb. 1993. Differentiation and identification of the two catalytic metal binding sites in bovine lens leucine aminopeptidase by x-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5006-5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, W., and W. B. Whitman. 1999. Isolation of acetate auxotrophs of the methane-producing archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis by random insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 152:1429-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein, J. R., and B. Henrich. 1998. Lysyl aminopeptidase (bacterial), p. 1018-1020. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 26.Klenk, H. P., R. A. Clayton, J. F. Tomb, O. White, K. E. Nelson, K. A. Ketchum, R. J. Dodson, M. Gwinn, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, D. L. Richardson, A. R. Kerlavage, D. E. Graham, N. C. Kyrpides, R. D. Fleischmann, J. Quackenbush, N. H. Lee, G. G. Sutton, S. Gill, E. F. Kirkness, B. A. Dougherty, K. McKenney, M. D. Adams, B. Loftus, J. C. Venter, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature 390:364-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi, K., and J. A. Smith. 1987. Acyl-peptide hydrolase from rat liver. Characterization of enzyme reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 262:11435-11445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mai, X., and M. W. Adams. 1996. Purification and characterization of two reversible and ADP-dependent acetyl coenzyme A synthetases from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 178:5897-5903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metz, G., and K. H. Rohm. 1976. Yeast aminopeptidase I. Chemical composition and catalytic properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 429:933-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morty, R. E., and J. Morehead. 2002. Cloning and characterization of a leucyl aminopeptidase from three pathogenic Leishmania species. J. Biol. Chem. 277:26057-26065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motoshima, H., S. Takayasu, F. Tsukasaki, and S. Kaminogawa. 2003. Purification, characterization, and gene cloning of lysyl aminopeptidase from Streptococcus thermophilus YRC001. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67:772-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez-Zavala, B., Y. Mercado-Flores, C. Hernandez-Rodriguez, and L. Villa-Tanaca. 2004. Purification and characterization of a lysine aminopeptidase from Kluyveromyces marxianus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 235:369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rawlings, N. D., and A. J. Barrett. 1995. Evolutionary families of metallopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 248:183-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rawlings, N. D., D. P. Tolle, and A. J. Barrett. 2004. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D160—D164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schut, G. J., S. D. Brehm, S. Datta, and M. W. W. Adams. 2003. Whole-genome DNA microarray analysis of a hyperthermophile and an archaeon: Pyrococcus furiosus grown on carbohydrates or peptides. J. Bacteriol. 185:3935-3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slesarev, A. I., K. V. Mezhevaya, K. S. Makarova, N. N. Polushin, O. V. Shcherbinina, V. V. Shakhova, G. I. Belova, L. Aravind, D. A. Natale, I. B. Rogozin, R. L. Tatusov, Y. I. Wolf, K. O. Stetter, A. G. Malykh, E. V. Koonin, and S. A. Kozyavkin. 2002. The complete genome of hyperthermophile Methanopyrus kandleri AV19 and monophyly of archaeal methanogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4644-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, D. R., L. A. Doucette-Stamm, C. Deloughery, H. Lee, J. Dubois, T. Aldredge, R. Bashirzadeh, D. Blakely, R. Cook, K. Gilbert, D. Harrison, L. Hoang, P. Keagle, W. Lumm, B. Pothier, D. Qiu, R. Spadafora, R. Vicaire, Y. Wang, J. Wierzbowski, R. Gibson, N. Jiwani, A. Caruso, D. Bush, J. N. Reeve, et al. 1997. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J. Bacteriol. 179:7135-7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Story, S. V., A. M. Grunden, and M. W. Adams. 2001. Characterization of an aminoacylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 183:4259-4268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsunasawa, S. 1998. Purification and application of a novel N-terminal deblocking aminopeptidase (DAP) from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Protein Chem. 17:521-522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsunasawa, S., Y. Izu, M. Miyagi, and I. Kato. 1997. Methionine aminopeptidase from the hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: molecular cloning and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the gene, and characteristics of the enzyme. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 122:843-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsunasawa, S., S. Nakura, T. Tanigawa, and I. Kato. 1998. Pyrrolidone carboxyl peptidase from the hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: cloning and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the gene, and its application to protein sequence analysis. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 124:778-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilk, S., E. Wilk, and R. P. Magnusson. 2002. Identification of histidine residues important in the catalysis and structure of aspartyl aminopeptidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 407:176-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilk, S., E. Wilk, and R. P. Magnusson. 1998. Purification, characterization, and cloning of a cytosolic aspartyl aminopeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15961-15970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]