Abstract

Bacterial nitrous oxide (N2O) respiration depends on the polytopic membrane protein NosR for the expression of N2O reductase from the nosZ gene. We constructed His-tagged NosR and purified it from detergent-solubilized membranes of Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 14405. NosR is an iron-sulfur flavoprotein with redox centers positioned at opposite sides of the cytoplasmic membrane. The flavin cofactor is presumably bound covalently to an invariant threonine residue of the periplasmic domain. NosR also features conserved CX3CP motifs, located C-terminally of the transmembrane helices TM4 and TM6. We genetically manipulated nosR with respect to these different domains and putative functional centers and expressed recombinant derivatives in a nosR null mutant, MK418nosR::Tn5. NosR's function was studied by its effects on N2O respiration, NosZ synthesis, and the properties of purified NosZ proteins. Although all recombinant NosR proteins allowed the synthesis of NosZ, a loss of N2O respiration was observed upon deletion of most of the periplasmic domain or of the C-terminal parts beyond TM2 or upon modification of the cysteine residues in a highly conserved motif, CGWLCP, following TM4. Nonetheless, NosZ purified from the recombinant NosR background exhibited in vitro catalytic activity. Certain NosR derivatives caused an increase in NosZ of the spectral contribution from a modified catalytic Cu site. In addition to its role in nosZ expression, NosR supports in vivo N2O respiration. We also discuss its putative functions in electron donation and redox activation.

Bacteria that use nitrous oxide as an electron sink for respiration synthesize a copper enzyme nitrous oxide (N2O) reductase (EC 1.7.99.6, encoded by the nosZ gene) and several ancillary proteins that participate in the biosynthesis of the copper centers CuA and CuZ (47, 53). N2O utilization usually plays a part in nitrate or nitrite denitrification, but it also exists in nature as an autonomous respiratory mode, as exemplified in the genus Wolinella (50). An important role for N2O respiration is attributed to the NosR protein, which is consistently encoded in the nos gene cluster of N2O-respiring bacteria. nosR mutants are unable to utilize N2O (13, 20, 43). In most cases, the nosR gene is located adjacent to and upstream of nosZ. Ever since the identification of the nos locus and evidence of several ancillary genes (44, 54), NosR has remained an enigmatic component. Yet its polytopic structure, and as we show here, its membrane-bound nature, cofactor content, and diverse functions make it a fascinating accessory factor for N2O respiration. The NosR protein has a periplasmic domain of about 390 amino acids (of a total of 689 residues) and a hydrophobic domain of five transmembrane helices. The C-terminal region features distinct cysteine patterns, the most conspicuous of which make up a polyferredoxin-like structure (12, 13, 20, 26, 43). In parallel with our study, it was noted recently by use of a comparative bioinformatics approach that part of NosR has structural similarity to a bacterial flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-binding protein domain (49).

NosR and its homologues exhibit an activating function for gene expression. The nos genes of Pseudomonas stutzeri are arranged in three transcriptional units, comprising the monocistronic nosR and nosZ genes and the nosD operon (13, 21, 45). Tn5 insertions in the 5′ region of nosR caused a loss of the nosZ transcript, which led to the consideration of NosR as a regulatory component. We have shown recently that NosR is also a factor in the expression of the nosD operon for Cu cluster biosynthesis (21). nosR expression, in turn, depends on the transcription factor DnrD of the Crp-Fnr regulator family. DnrD provides a denitrification-specific signal in response to NO (45). A paralogue of nosR, the nirI gene, has been studied for Paracoccus denitrificans. This gene is not a general feature of nitrite-denitrifying bacteria, but its product is required in this organism for the expression of nirS, which encodes the cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase (38). nirI shows a distinct positional effect with respect to nirS transcription and cannot be complemented in trans. It is under the control of the DnrD homologue Nnr. Unlike the case for P. stutzeri, the nosR gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is transcribed as part of a pentacistronic nosRZDFY operon. The operon is under the control of Dnr, which is also a DnrD homologue. Although NosR is not necessary in this organism for nosZ transcription, a disruption of nosR halves the promoter activity of the operon (1). Sequence and topological similarities to NosR were also found in CprC, although this protein has a smaller periplasmic domain and lacks the polyferredoxin signature (40). CprC is necessary for the formation of enzymes for o-chlorophenol respiration.

Based on a homologous expression system for the nosR gene of P. stutzeri, we have purified NosR and provide evidence that it is a membrane-bound iron-sulfur flavoprotein. Recombinant NosR forms were constructed to address the effects of various protein domains on NosZ function and properties. Our results indicate that NosR is not only required for nosZ transcription but is also indispensable for sustaining cellular NosZ activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli DH10B (Gibco BRL) was used as a host for the cloning and propagation of plasmids. P. stutzeri MK21 is a spontaneous Smr mutant of the strain ATCC 14405. The generation of MK418(nosR::Tn5) by insertional mutagenesis was described previously (44). The plasmids pUC18 (Apr) (48) and pUCP22 (Apr Gmr) (46) were used as general cloning vectors. The plasmid pUCP22RZ was derived from pUCP22 and carries nosRZ within a 5.3-kb Eco47III-SmaI fragment (47); the plasmid pUCP22RE is another pUCP22 derivative which carries the entire nosRZDFYLtatE sequence within an 8.8-kb Eco47III-XbaI fragment (18). E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. For use in recombinant DNA work, Pseudomonas strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 30°C and 240 rpm on a gyratory shaker. For other purposes, the asparagine- and citrate-containing AC medium supplemented with 5 μM Cu was used (10). The shift to denitrifying conditions of an aerobically growing culture was generated by reducing the shaking speed from 240 to 120 rpm and adding sodium nitrate to a final concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol). When necessary for strain maintenance, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (μg/ml of medium): streptomycin, 200; kanamycin, 50; ampicillin, 100; and gentamicin, 30.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard protocols were used for plasmid preparation and purification, agarose gel electrophoresis, dephosphorylation, and ligation of DNA (18). Restriction enzymes were used as recommended by the manufacturer (Fermentas). Transformation was done by electroporation (14, 15). DNA was sequenced by use of a dye terminator kit (Amersham Biosciences) and an ALFexpress sequencer according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA analysis.

Cells were grown first under aerobic conditions. When the optical density at 660 nm was approximately 0.3, the culture was shifted to denitrifying conditions. Total RNA was extracted by the hot phenol method from cells that were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and Northern blotting was performed as described previously (45). Hybridization and detection were done with a digoxigenin-labeled nosZ probe (47) according to the instructions for the EasyHyb system (Roche Diagnostics).

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmid pPRE-3 was constructed by subcloning the complete nos gene cluster of pUCP22RE as an 8.8-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment into pUCP22 that had been digested with SmaI (18). The orientation of the nos genes was inverted with respect to the lacZ promoter. Plasmid pPRdC was constructed from pPRE-3 by deleting a 765-bp XhoI-XhoI nosR fragment in frame, leading to the expression of NosR with a shortened periplasmic domain (deletion of amino acids 112 to 366). Plasmids pPRdDE1+ and pPRdDE2+ were constructed by replacing the 742-bp KpnI-Kpn2I nosR fragment of pPRE-3 with a 142-bp (pPRdDE1+) or 331-bp (pPRdDE2+) KpnI-HindIII PCR fragment. The fragments were designed to add the codons for a His6 tag, a stop codon, and a HindIII site to nosR, thereby deleting the coding regions for amino acids 461 to 724 and 524 to 724 in pPRdDE1+ and pPRdDE2+, respectively. Plasmids with a His tag were constructed first to detect the synthesis of truncated proteins and were used later to construct the recombinant plain NosR derivatives. In the case of pPRdDE1+, three consecutive PCRs using the product of the former cycle as a template (the first cycle used pUCP22RZ as a template) were performed with the following primers: 5′-CAGTTCGGCGACACCATCAG-3′ (sense, used for all three PCR cycles), 5′-attgctgtgatgatgGCCATGGCGCAGCCGCTTGAGGAAG-3′ (antisense, used for first PCR), 5′-attgctatggtggtgGTGATGATGGCCATGGCGCAGCC-3′ (antisense, used for second PCR), and 5′-gccggcaagcttttaATGGTGGTGGTGATGAT-3′ (antisense, used for third PCR). In the case of pPRdDE2+, the PCR fragment was amplified in a single PCR (template pUCP22RZ) with the sense primer described above and the antisenseprimer 5′-accggcaagcttttaatggtggtggtgatgatgGAACACGCCACGCCCCA-3′.Lowercase letters in the antisense primers denote nucleotides of 5′ extensions; bold letters indicate the codons of the His6 tag and the stop codon, whereas the nucleotides for the added HindIII sites are shown in italics.

Variants of pPRdDE1+ and pPRdDE2+ without His6 tags were constructed as follows. A nosR fragment lacking the tag but not the subsequent Kpn2I restriction site was amplified by PCR with pPRdDE1+ and pPRdDE2+ as templates by use of the following primers: 5′-CTGGAACCTCGAGCTTCT-3′ (sense), 5′-atatgcccgtccggagcttttaGCCATGGCGCAGCCGCTTGA-3′ (antisense for pPRdDE1+), and 5′-atatgcccgtccggagcttttaGAACACGCCACGCCCCCACA-3′ (antisense for pPRdDE2+). Lowercase letters indicate nucleotides of 5′ extensions, bold letters indicate the stop codon, and italics indicate the Kpn2I site. The PCR products were sequenced, restricted with KpnI and Kpn2I, and subcloned into the likewise digested plasmids pPRdDE1+ and pPRdDE2+, yielding pPRdDE1 and pPRdDE2, respectively.

Plasmid pMR was constructed by subcloning a 1.2-kb PvuII-PvuII nosR fragment of pUCP22RZ (47) into EcoRI- and NdeI-digested pUC18. Unless stated otherwise, pMR was used as a template for the following PCR-based modifications of nosR. Plasmids pPRdM1 and pPRdM2 expressed NosR derivatives with the cysteine residues of the CX3CP(TM4) and CX3CP(TM6) motifs, respectively, replaced with valine. The point mutations were introduced by the one-step QuickChange strategy (Stratagene). In the case of pPRdM1, pMR was amplified in two consecutive PCR cycles by use of the product of the first PCR as the template of the second reaction. The primers used for the first PCR and the C524→V substitution were 5′-GGCGTGGCGTGTTCgtCGGCTGGCTGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACAGCCAGCCGacGAACACGCCACGCC-3′ (antisense); those for the second PCR and the C528→V substitution were 5′-TGGCTGgtCCCCTTCGGCGCCCTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCAGGGCGCCGAAGGGGacCAGCCA-3′ (antisense). The mutations, indicated in lowercase in the primer sequences, were verified by sequencing and then subcloned as 908-bp XhoI-Kpn2I fragments into likewise digested pPRE-3. In the case of pPRdM2 (C623→V and C627→V changes), the primers 5′-GGTCTATgtCCGCTACGTCgtCCCGCTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCAGCGGGacGACGTAGCGGacATAGACC-3′ (antisense) were used.

Plasmid pPRdM12 was constructed from the PCR products described above and carried sequences for the C524→V/C528→V and C623→V/C627→V substitutions. A 220-bp Eco130I-EheI fragment of the product coding for the C524→V and C528→V mutations was subcloned into the likewise digested pMR derivative that coded for the C623→V and C627→V changes. This resulted in a plasmid with four cysteine-to-valine substitutions. Subcloning into pPRE-3 was done as described above.

pPRdE was constructed as described for plasmid pPRdM2. The PCR primers 5′-CTGGCGATCACCtGatGaTTCCGGCTGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACAGCCGGAAtCatCaGGTGATCGCCAG-3′ (antisense) were designed to replace G637 and R638 with stop codons. The PCR product was sequenced and then subcloned into pPRE-3 as described above.

Plasmids pPRdCdDE1 and pPRdCdDE2 encoded combinations of the NosRa and -b and NosRa and -c proteins, respectively, on the same vector. Their construction was based on pUCP22RZ. First, the His6 tag-encoding KpnI-HindIII PCR fragments of nosR from pPRdDE1+ and pPRdDE2+ were cloned into likewise digested pUCP22RZ to give 1+ and 2+ derivatives of pUCP22RZ. The 4.6-kb EcoRI-SmaI fragment of pPRdC, carrying the modified nosR(Δ765-bp XhoI), nosZ, and part of nosD, was then cloned in the opposite orientation into the EcoRV site of the gentamicin resistance gene of both pUCP22RZ derivatives.

Expression vector for NosR-His6.

Plasmid pPR6hE was constructed from plasmid pUCP22RE (47) by the insertion of a 189-bp Kpn2I-Kpn2I PCR fragment into the Kpn2I site of pUCP22RE. The fragment was designed to add the codons for a His6 tag, a stop codon, and a Kpn2I site at the 3′ end of nosR. The PCR fragment was amplified in a single PCR step, using pUCP22RE as the template for the sense primer 5′-GAAGTGCAGGCGATTCA-3′ and the antisense primer 5′-ggcttccggatcagtgatgatgatgatgatgGGGTTCCACCACTTG-3′. Lowercase letters denote nucleotides of 5′ extensions, bold letters indicate the codons of the His tag and the stop codon, and the new Kpn2I site is shown in italics.

Purification of NosR-His6.

The NosR-His6 protein was obtained from strain MK418(pPR6hE) grown under denitrifying conditions. The isolation procedure was performed under a protective argon atmosphere as described for the purification of NosZ (10). The NosZ protocol was used for cell disruption and the isolation of membranes by ultracentrifugation. The membrane fraction was collected from approximately 75 g of cell mass obtained from a 50-liter denitrifying batch culture. Membranes were suspended in 100 ml of 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0) (buffer A), and Triton X-100 was added from a 10% (wt/vol) stock solution made with buffer A. The detergent-to-protein ratio was 10:1 (wt/wt). After stirring the solution for 1 h at 4°C, we removed unsolubilized membranes by centrifugation for 90 min at 136,000 × g. NosR-His6 was purified from the supernatant.

(i) Ion-exchange chromatography.

A column (5 by 8 cm) of DEAE-cellulose (DE-52; Whatman) was equilibrated with buffer A containing 0.02% (wt/vol) Triton X-100. The solubilized membrane fraction was brought to 1 liter with buffer A and applied to the column at a flow rate of 500 ml h−1. The column was washed with 1 liter of equilibration buffer, and the proteins were eluted with 1 M buffered NaCl. The eluate was concentrated by ultrafiltration with an XM-50 membrane (Amicon) to approximately 35 ml. Imidazole was added from a 1 M stock solution in buffer A to a final concentration of 20 mM.

(ii) Metal affinity chromatography.

The protein solution was mixed with 1 ml of a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose resin (QIAGEN) and incubated on a roller table in a gas-tight centrifuge bottle at 4°C overnight. The matrix was collected at 500 × g for 5 min and washed for 1 h in 10 ml of 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0) containing 0.02% Triton X-100, 1 M NaCl, and 35 mM imidazole. The washing steps were repeated twice with 10 ml of buffer A containing 0.01% (wt/vol) n-dodecyl maltoside and 35 mM imidazole. Afterwards, the proteins were eluted in 2 ml of this buffer, but with 250 mM imidazole.

(iii) Ion-exchange chromatography.

The yellowish eluate was further purified by use of an ÄKTA purifier system (Amersham Biosciences) equipped with a 1-ml HiTrap Q Sepharose HP column (Amersham Biosciences) and equilibrated with 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0)-0.01% n-dodecyl maltoside at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. After loading of the protein solution, the column was washed with 2 ml of the same buffer and developed with 20 ml of a buffered linear NaCl gradient (0.15 to 0.5 M). Fractions of 1 ml were collected. NosR-His6 typically eluted around 0.35 to 0.4 M NaCl. NosR-containing fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration with a PM 10 membrane (Amicon) and then stored on ice for further use.

Purification of NosRb-His6.

The NosRb-His6 protein was obtained from strain MK418(pPRdDE1+) grown under denitrifying conditions. NosRb-His6 was isolated by the same procedure as that used for NosR-His6. As an additional purification step, affinity chromatography was repeated after the Q Sepharose treatment. The Ni-NTA column was washed with 50 mM increments of imidazole in a buffer containing 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0), 0.01% n-dodecyl maltoside, 0.2 M NaCl, and 20% (wt/vol) glycerol. The protein fraction eluting at 150 mM was collected and used for experiments.

For N-terminal sequencing, the protein was dialyzed against 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0) and then lyophilized. An N-terminal sequence of KEYAAEQ was obtained with an Applied Biosystems Procise sequencer by Edman degradation (SeqLab, Göttingen, Germany). The peptide was identical to the deduced amino acid sequence.

Purification of NosZ from nosR′ strains.

Purification required approximately 10 g of cell mass obtained from four 2-liter flasks with 1 liter of AC medium in each. The flasks were inoculated from an aerobically grown 100-ml culture to an initial optical density of 0.03 and then grown aerobically. Once the optical density had reached approximately 0.3, the cultures were switched to denitrifying conditions and incubated overnight. Cells were harvested in the cold. NosZ was isolated under a protective argon atmosphere according to a modification of a standard protocol (10), as follows.

First, the periplasmic proteins were isolated via a lysozyme digestion method (31). Freshly harvested cells were washed once with 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and then suspended on ice at a 1:4.5 (wt/vol) ratio in 200 mM Tris-1 M sucrose. For each gram of biomass, 450 μl of 0.1 M EDTA (pH 7.6) and 9 ml of a lysozyme solution (0.5 mg/ml) were added. Spheroplast formation was stopped by the addition of 450 μl of 1 M magnesium chloride per g of cell mass after 5 min of incubation. The periplasmic extract was separated from spheroplasts by centrifugation at 5,000 × g, and membranes were removed by ultracentrifugation at 136,000 × g.

The periplasmic proteins were fractionated by ammonium sulfate as described previously and then suspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Samples of 6 ml were loaded on a Sephacryl S300-HR column (2.5 by 90 cm) operating at a flow rate of 25 ml h−1 with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Fractions of 2.5 ml were collected and analyzed for Cu by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Cu-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated, and desalted by ultrafiltration. The final purification steps consisted of preparative isoelectric focusing and Sephacryl S-200 gel permeation chromatography as described previously (10).

Cell extract, gel electrophoresis, and enzyme detection.

Preparations of cell extract, the conditions of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the immunochemical detection of NosZ were described previously (47). His-tagged NosR proteins were detected immunochemically by use of an anti-His5 antibody according to the procedures of the supplier (QIAGEN). The primary antibody was reacted with an anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugate and visualized by luminol (Pierce) chemiluminescence.

Protein characterization and activity measurements.

The N2O-reducing activity of whole cells was measured by gas chromatography, with 50 mM lactate as the electron donor (8). The activity of purified N2O reductase was measured spectrophotometrically with photoreduced benzyl viologen (10). The protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method. The Cu contents of purified NosZ and of chromatographic fractions, as well as the Fe content of NosR-His6, were measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Acid-labile sulfur was detected by the method of Beinert (2).

NosR numbering.

Numbering of the amino acids of NosR follows the original translation of the nosR nucleotide sequence (accession no. Z13988) (13).

RESULTS

Homologous expression system for nosR.

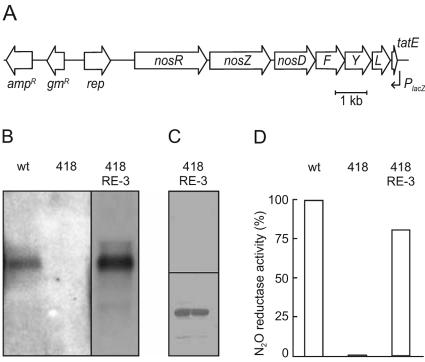

We have investigated NosR based on an expression system that complements the P. stutzeri nosR::Tn5 mutant MK418 (44). The generation of recombinant NosR derivatives took advantage of the replication function of the broad-host-range plasmid pUCP22 in Pseudomonas sp. (46). Since NosZ biosynthesis depends on auxiliary gene products that affect its expression level and protein translocation efficiency (8, 13, 18, 47), we cloned the entire nos cluster, including the tatE gene for protein transport, into pUCP22, which resulted in the nosR expression vector pPRE-3 (Fig. 1A). The nos cluster was oriented opposite to the lacZ promoter to ensure that gene expression was under the control of the native nos promoters. Northern blot analysis revealed a nosZ transcript in strain MK21, representing wild-type traits, and in the host strain MK418 transformed with pPRE-3, whereas MK418 itself lacked nosZ mRNA (Fig. 1B). The increased transcript level in MK418(pPRE-3) due to the copy number of the episomal nos gene cluster resulted in an overproduction of N2O reductase.

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of nosR expression system. (A) Physical map of pPRE-3 expression vector. (B) Northern blot analysis of the nosR transcript in P. stutzeri strain MK21, representing wild-type traits (wt); the nosR null mutant MK418 (418); and MK418 transformed with plasmid pPRE-3 (418RE-3). (C) Expression of nosZ in complemented strain MK418(pPRE-3) depends on denitrifying conditions. Upper panel, Western blot analysis of a crude extract of cells grown aerobically; lower panel, analysis of cells grown under denitrifying conditions. (D) N2O-reducing activity of intact cells of strains shown in the previous panels. N2O uptake was monitored by gas chromatography.

NosZ synthesis in the expression strain was regulated as in the wild type. Aerobically grown cells did not produce the reductase protein; its appearance required anaerobic or oxygen-limited growth conditions, in each case in the presence of nitrate (Fig. 1C). An assay for N2O reduction in whole cells showed that functional NosZ was produced (Fig. 1D). However, the NosZ activity did not increase proportionally with enzyme overproduction, indicating that there was some limiting factor or down-regulation of enzyme activity. Purified NosZ from MK418(pPRE-3) exhibited the spectral properties of a wild-type enzyme in which metal insertion into CuA and Cu-S cluster synthesis for the catalytic center, CuZ, had taken place (data not shown).

Recombinant NosR derivatives.

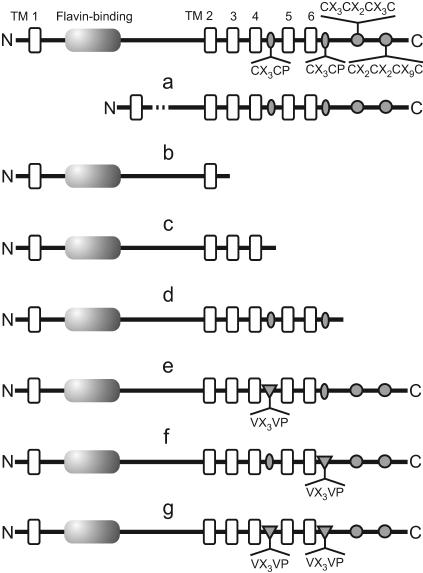

The functional importance of the conserved signature for FMN binding and of the C-terminal metal-binding centers was studied by the construction of recombinant NosR proteins. Each construct was verified to have the correct modification by sequencing. Complementation by nosR′-carrying plasmids resulted in the synthesis of NosZ, indicating the formation of a modified NosR protein that was functional for nosZ expression. The following information gives a synopsis of the generated derivatives, and their modifications are depicted graphically in Fig. 2. NosRa has an internal deletion in the periplasmic domain comprising amino acids 112 to 366, which includes most of the flavin-binding region (positions 80 to 180) but conserves all transmembrane parts and metal-binding domains. The conservation of the N terminus and at least one transmembrane helix following the large hydrophilic part of the protein is expected to maintain the topology of the protein. This was also considered for the following constructs. NosRb, being truncated at amino acid 460, carries with TM2 just one membrane anchor. NosRc resembles construct NosRb but carries two additional membrane helices, TM3 and TM4, which extend the protein to amino acid 523. We also constructed NosRb and NosRc with His6 tags for immunochemical detection of the truncated proteins (data not shown). NosRd lacks the C-terminal Fe-S domain. The deletion was introduced by changing the codons for G637 and R638 into stop codons, thereby terminating translation at T636. NosRe carries a 524VX3VP529 motif following TM4, in which the original cysteine residues were both replaced with valine. In NosRf, the 623CX3CP628 motif following TM6 was subjected to the same substitutions. The NosRg protein is a combination of the derivatives NosRe and NosRf, with either CX3CP motif being modified (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Structural elements of unprocessed NosR (top row) and pictograms of affected features of recombinant NosR proteins. (a) NosRa, which lacks the periplasmic domain and flavin-binding motif, expressed from plasmid pPRdC; (b) NosRb, which has a deletion of transmembrane helices TM3 to TM6, expressed from plasmid pPRdDE1; (c) NosRc, which has a deletion of transmembrane helices TM5 and TM6, expressed from plasmid pPRdDE2; (d) NosRd, which lacks the Fe-S domain, expressed from plasmid pPRdE; (e) NosRe, which has a site-directed modification of the 524CX3CP529(TM4) motif to VX3VP, expressed from plasmid pPRdM1; (f) NosRf, which has a site-directed modification of the 623CX3CP628(TM6) motif to VX3VP, expressed from plasmid pPRdM2; (g) NosRg, which has a joint modification of both CX3CP motifs, expressed from plasmid pPRdM12.

Functionality of NosR resides in both the N-terminal and C-terminal parts.

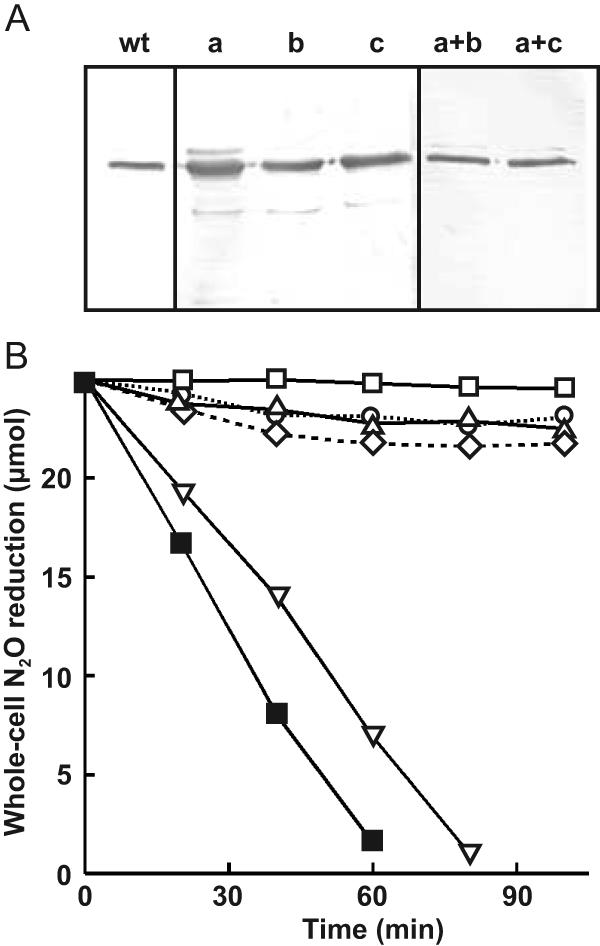

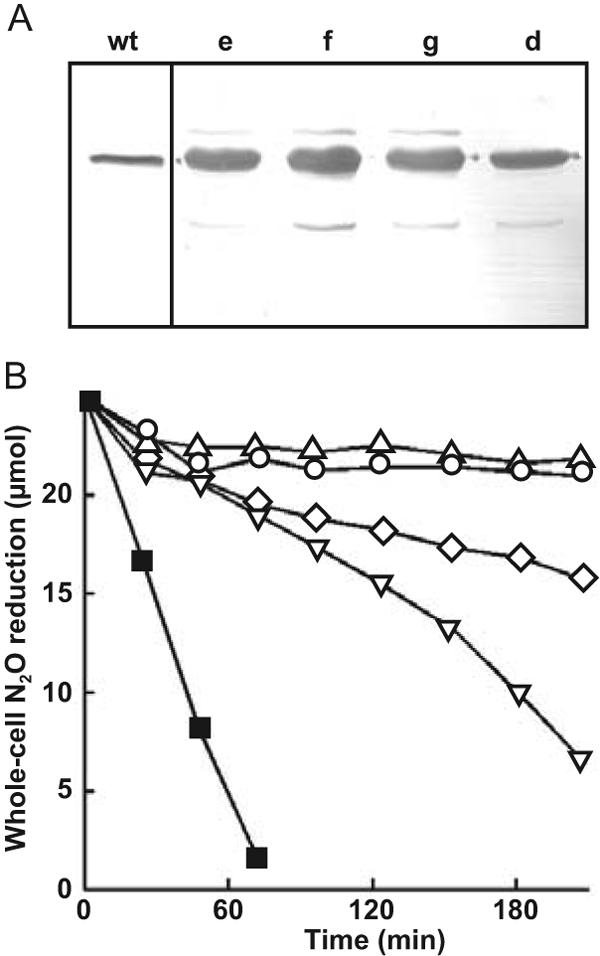

The recombinant constructs for NosRa, -b, and -c resulted in the overexpression of NosZ. The highest level of NosZ was found with NosRa, including a small amount of pre-NosZ that was indicative of saturation of the Tat translocase (Fig. 3A) (18). The complemented systems with the truncated proteins NosRb and NosRc also overexpressed NosZ compared to the wild type but had less enzyme than the NosRa strain. In contrast to NosZ synthesis, NosZ activity was lost in vivo by the effected changes in NosR (Fig. 3B). There was a small initial activity phase with NosRa, -b, or -c of about 10% of the control activity followed by a rapid inhibition of N2O reduction. The results showed that sustaining whole-cell NosZ activity requires a functional periplasmic domain as well as some part of the C-terminal region of NosR.

FIG. 3.

NosR activity is reconstituted by coexpressing the N-terminal and C-terminal protein domains. (A) Western blot evidence for NosZ synthesis in MK418 cells expressing recombinant proteins NosRa, -b, and -c (see Fig. 2). a+b and a+c, coexpression of the respective NosR derivatives. (B) N2O reduction by whole cells, expressing the constructs listed in panel A, was monitored by gas chromatography. ▪, wt (MK21); ◊, NosRa; ▵, NosRb; ○, NosRc; ▿, coexpression of NosRa and NosRb; □, coexpression of NosRa and NosRc.

The observation of an in vivo inactive N2O reductase system led us to ask whether NosR can be functionally reconstituted in a NosRa background by providing the periplasmic part separately, thus complementing construct NosRa, which lacks precisely this domain. For this purpose, the genes encoding NosRa, -b, and -c were subcloned with their native promoters and a copy of nosZ in the combinations NosRa-NosRb and NosRa-NosRc into pUCP22, resulting in the expression vectors pPRdCdDE1 and pPRdCdDE2, respectively. We found that the coexpression of NosRa and NosRb provided full NosR functionality, as seen by both nosZ expression (comparable to the wild type) and whole-cell N2O reduction (Fig. 3). When NosRa was provided in combination with NosRc, which has the transmembrane helices TM3 and TM4 added to NosRb, it led to nosZ expression like the former case, but no activity was observed (Fig. 3B). An initial activity followed by inhibition of the reaction, as found for separately expressed NosRa or NosRc, was not seen. We observed no nosZ overexpression upon the coexpression of NosR′ proteins, which we attributed in these cases to the single chromosomal copy of the assembly genes.

Truncated proteins exhibiting their individual roles can thus reconstitute the overall function(s) of NosR. The N-terminal and C-terminal parts seem to be required to interact properly, since adding two helices with construct NosRc in the presence of the NosRa protein allowed only the synthesis of an in vivo inactive N2O-reducing system.

NosR is an iron-sulfur flavoprotein.

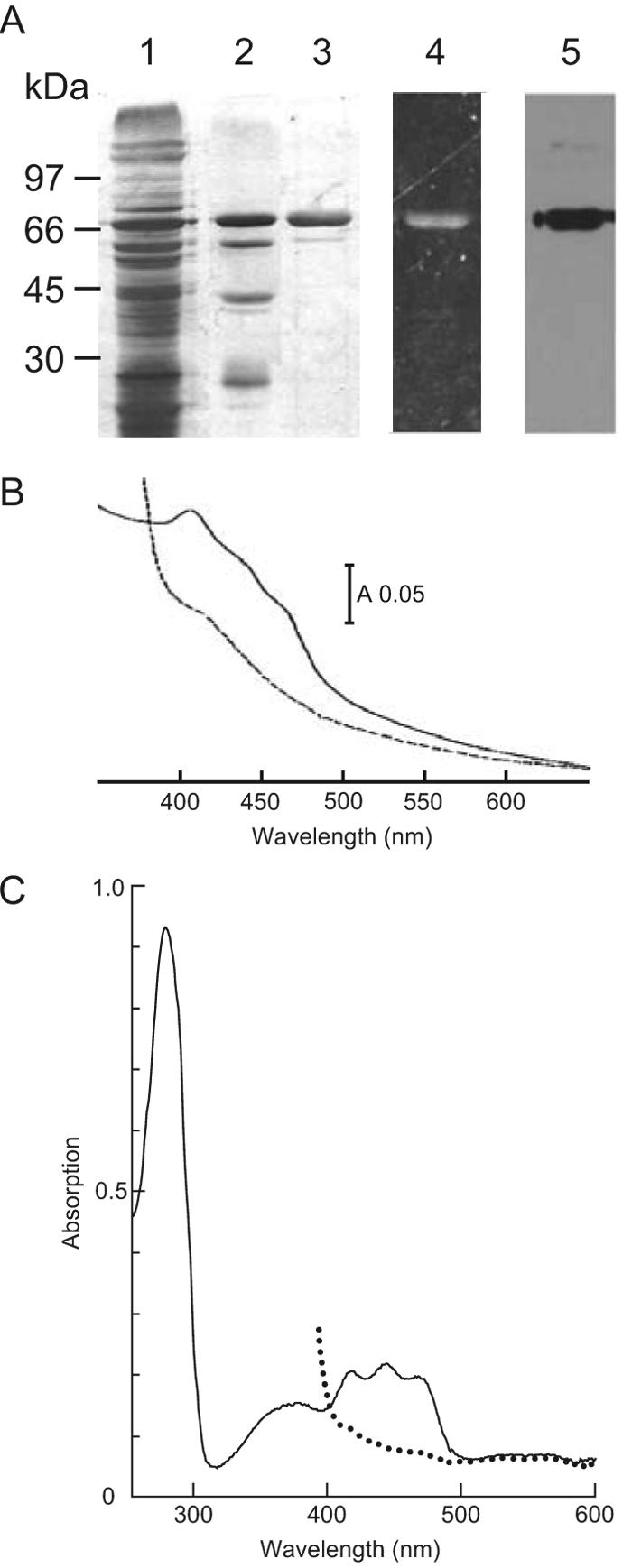

Because sequence signatures suggested that there are several cofactors for NosR, we isolated the protein to investigate its biochemical nature. NosR was purified based on its overexpression from plasmid pPR6hE, in which nosR was fused to codons for a C-terminal His6 tag. Cells were grown in batch culture under denitrifying conditions. NosR-His6 was solubilized from membranes by the use of Triton X-100 and was purified under anaerobic conditions by ion-exchange and affinity chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. The protein fraction obtained from the Ni-NTA matrix showed several minor bands upon SDS electrophoresis (Fig. 4A, lane 2), among which was a band for a c-type cytochrome. These contaminating proteins were removed by a second ion-exchange chromatography step. NosR-His6 behaved in SDS electrophoresis as a protein of approximately 75 kDa. It reacted in a Western blot analysis with an anti-His5 antibody and showed fluorescence under UV light (Fig. 4A). The protein precipitated upon freezing and thawing but could be dissolved in 8 M urea without losing its fluorescing cofactor.

FIG. 4.

The periplasmic domain of NosR carries a covalently attached flavin. NosR-His6 was expressed from plasmid pPR6hE and then purified. (A) SDS-PAGE patterns viewed by silver staining or the detection method specified below. Lane 1, solubilized membranes; lane 2, eluate from the Ni-NTA matrix with 250 mM buffered imidazole; lane 3, purified NosR-His6 after chromatography on HiTrap gel; lane 4, fluorescent band of NosR-His6 viewed under UV light; lane 5, Western blot analysis of purified NosR-His6 and detection with anti-His5 antibody. (B) Visible absorption spectrum of purified NosR-His6 protein in buffer containing 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0), 250 mM imidazole, 0.01% n-dodecyl maltoside, and 0.3 M NaCl. (C) UV-visible absorption spectrum of purified NosRb-His6 protein expressed from plasmid pPRdDE1+ in buffer containing 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.0), 150 mM imidazole, 0.01% n-dodecyl maltoside, 0.2 M NaCl, and 20% glycerol. Solid lines, proteins as isolated; dotted lines, proteins after the addition of dithionite. Spectra were recorded with an HP-8453 diode array instrument (Hewlett Packard).

Solutions of NosR were yellow and exhibited an electronic absorption spectrum of overlapping components in the region of 350 to 500 nm (Fig. 4B). There was a prominent peak at 407 nm followed by two shoulders at 435 and 465 nm. The absorption decreased upon reduction of the protein with dithionite and gave no indication of the presence of a heme protein. Broad maxima around 375 and 450 nm are typical for flavoproteins. More evidence for a flavin in NosR came from our isolation of the derivative NosRb-His6, which is a NosR′ protein truncated after transmembrane helix TM2 and modified by the addition of an N-terminal His tag (Fig. 2). This protein was purified according to the procedure used for NosR-His6, with a second metal affinity chromatography step added as a final step. The protein was homogeneous and behaved in SDS-PAGE as a 50-kDa species. NosRb-His6 exhibited the spectrum shown in Fig. 4C. The short-wavelength absorption maximum was positioned at 370 nm; the long-wavelength absorption was resolved into three peaks, at 411, 437, and 460 nm, which were lost upon the addition of dithionite. The latter absorption bands were also recognizable in the holoprotein.

NosR carries C-terminal cysteine signatures for two clusters of the [4Fe-4S] type. A determination of the Fe content of NosR-His6 by atomic absorption spectroscopy indicated that there were up to 7.9 atoms per molecule, a value that satisfies the presence of two [4Fe-4S] clusters. A qualitative assay indicated the presence of acid-labile sulfur. The electronic absorption of holo-NosR is thus a composite of flavin cofactor and Fe-S absorption.

The N terminus of NosRb-His6 was sequenced and revealed the cleavage of a signal peptide at LQA|K, leaving a lysine residue at the N terminus. Mature NosR therefore comprises 689 amino acids and has a mass without cofactors of 78,057 Da. The translation start of NosR is uncertain (12), but the initially favored start codon (13) and our present data indicate a signal peptide of 35 amino acids with features for Sec translocation. Although a covalently bound flavin cofactor would predestine NosR for the Tat pathway of protein translocation, typical Tat recognition sequences are present in neither pre-NosR of P. stutzeri nor the predicted NosR signal sequences of NosR proteins from other bacteria (data not shown).

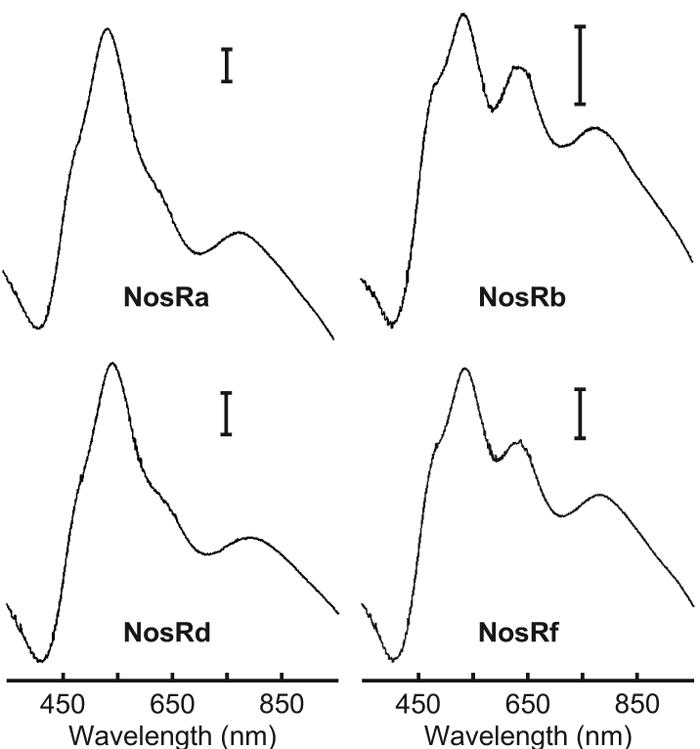

Mutations in metal centers of NosR affect cellular activity of NosZ.

Next, we studied the effect of the Fe-S domain on N2O respiration with the deletion derivative NosRd. NosZ was overexpressed at a slightly lower level than that in the above-described cases (Fig. 5A). The fact that NosZ was found in MK418 cells complemented with pPRdE again allowed the conclusion that there must be a NosR′ protein and activity in these cells. An alteration of the C terminus may affect the stability of the NosR′ protein and lower its level, which in turn might affect the level of nosZ expression. Alternatively, the Fe-S domain may be involved in the regulatory control of nosZ transcription. The N2O-reducing activity of cells expressing NosRd was about 15% that of the wild type (Fig. 5B), that is, NosR′ without the Fe-S cluster provided the nontranscriptional NosR function only at a strongly diminished level.

FIG. 5.

Whole-cell N2O respiration activities of MK418 cells synthesizing NosR derivatives without C-terminal cysteine clusters or with modifications of the CX3CP motifs. (A) Western blot analysis of NosZ in extracts of P. stutzeri MK21 (wt) and MK418 expressing the recombinant proteins NosRd, -e, -f, and -g (see Fig. 2 for details of proteins). (B) N2O reduction by whole cells of MK418 expressing the constructs listed in panel A was monitored by gas chromatography. ▪, MK21; ◊, NosRd; ○, NosRe; ▿, NosRf; ▵, NosRg.

In a further step, we addressed the effect of modifications of the CX3CP motifs of the membrane domain. We had observed activity loss with the constructs NosRb and NosRc, which lacked all metal-binding motifs. Since NosRd without the Fe-S domain still exhibited some N2O-reducing activity, we modified the CX3CP motifs of NosR. Both cysteine residues were replaced with valine in each motif either separately (NosRe and NosRf) or simultaneously (NosRg) (Fig. 2). The expression of each NosR′ protein resulted in the overexpression of NosZ, which reached a level comparable to that of NosRa (Fig. 5A).

NosRe caused a complete loss of N2O reduction, whereas NosRf allowed for about 35% of the control activity (Fig. 5B). The simultaneous modification of both motifs resulted in the activity phenotype of NosRe. NosZ seemed again to be subject to turnover inactivation, since we observed a low initial activity followed by inhibition of the reaction. Both CX3CP motifs are functionally important, although not equivalent, for N2O respiration. The motif Y(F)CGWLCPFGA(S), following TM4, is remarkably invariant, with an identical spacer peptide between the two cysteine residues in 22 NosR sequences, including NirI. Only NosR of Thiobacillus denitrificans has a conservative L→M substitution. The motif Y(F)CR(K)Y(V)L(M,V,I)CPLGA, following TM6, allows several amino acid substitutions, and although it is still highly conserved, showed the least effect on N2O reduction of all the NosR derivatives. It has been suggested that the two conserved CX3CP peptides interact by binding a metal or by thiol redox chemistry (3). This idea is attractive for helix positioning, as, for instance, TM4 and TM6 could thus be brought into contact, but the functional lack of equivalence of both elements seems to favor independent roles.

NosZ isolated from a recombinant nosR background may be modified but is catalytically active.

As a step further important, we determined the properties of NosZ proteins isolated from a recombinant nosR background. We purified NosZ anaerobically from transformed MK418 strains and assayed its Cu content, spectral properties, and activity in vitro. Four different phenotypes or NosR modifications were represented (Table 1). The in vitro activities of the NosZ proteins obtained from the expression strains were 1.3 to 3.0 μmol of N2O reduced · min−1 · mg of protein−1, a range typically found with enzyme preparations from P. stutzeri (10, 34) or Paracoccus pantotrophus (33). The bleaching of benzyl viologen in an in vitro assay was proportional to the amount of enzyme. NosZ contains a total of 12 Cu atoms per dimer (5, 8). The numbers of Cu atoms in the NosZ proteins isolated for this study were close to this value (Table 1). If we allow for some heterogeneity in the preparations, the metal content indicates occupancy of the Cu sites and shows that NosR does not take part directly in Cu center biogenesis. The effect of NosR in supporting N2O reduction must take place at the level of mature NosZ.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of NosZ proteins from MK418 complemented with recombinant NosR derivatives

| Synthesized NosR′ protein | Properties of resulting NosZ species | Electronic absorption (nm)a | Cu/NosZ ratio | Sp actb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NosRa | Type I (CuA and CuZ) | 485sh, 541, 640sh, 778 | 9.9 | 2.4 |

| NosRb | Type I and CuZ* | 485sh, 537, 637, 768 | 11.1 | 2.6 |

| NosRd | Type I (CuA and CuZ) | 485sh, 541, 640sh, 792 | 10.7 | 1.3 |

| NosRf | Type I and CuZ* | 485sh, 537, 636, 778 | 11.9 | 3.0 |

sh, shoulder. Data for protein as isolated.

Specific activities are given as micromoles of N2O reduced per minute per milligram of protein.

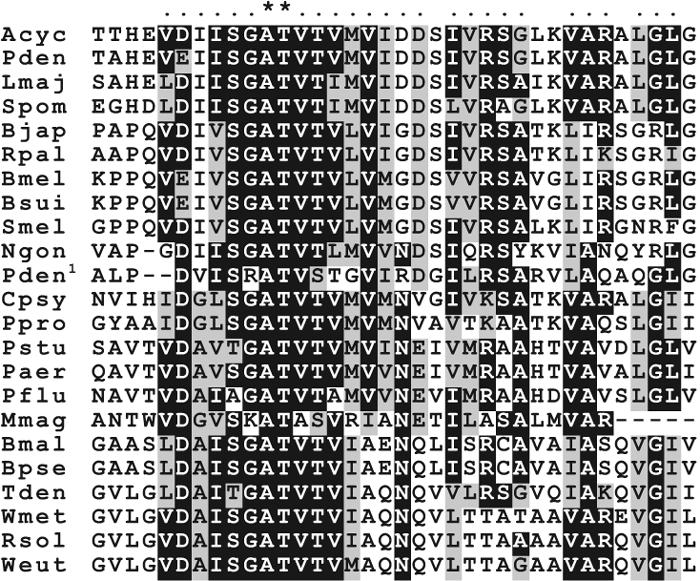

UV-visible spectra of the purified enzymes revealed two kinds of spectra (Fig. 6 and Table 1). One species, obtained from MK418 expressing NosRa or NosRd, showed features characteristic of the purple form (type I) of NosZ (35) isolated under anaerobic conditions. The spectrum from either strain showed only a small shoulder around 640 nm, indicative of a minor spectral contribution from the pink form (type II) of NosZ (10, 35). These overall spectral features representing wild-type characteristics were unexpected, as they provided no explanation for the loss of N2O-reducing activity of strain MK418(NosRa) or the reduced activity of strain MK418(NosRd).

FIG. 6.

Visible absorption spectra of NosZ proteins purified from strain MK418 transformed with plasmids encoding the indicated NosR′ derivatives. Spectra were recorded in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Each calibration bar shows an absorbance of 0.02. Spectra are shown for NosZ proteins isolated by an anaerobic purification procedure.

A new form of UV-visible spectrum of NosZ was found for MK418 cells expressing NosRb or NosRf. With these cells, in addition to the features described above, we observed a well-developed peak around 637 nm (Fig. 6). This peak was too pronounced to be the result of generation of the type II species by inadvertent oxygen exposure during enzyme isolation. Spectral features were not observed previously in this form with a P. stutzeri NosZ preparation. Whereas the CuA absorption disappeared upon reduction of the protein, the intensity of the 637-nm band was unchanged in the presence of dithionite or ferricyanide. The 637-nm species is reminiscent of the electronic spectrum of structural NosZ variants carrying the CuA ligand exchange H583G or C622D (8). It is attributed now to a modified catalytic center, CuZ, which has undergone a structural transformation to CuZ* (33).

DISCUSSION

We have confirmed here our previous observation that NosR is required in P. stutzeri for nosZ expression. Since in the absence of NosR, no nosZ mRNA is found, the immunochemical detection of NosZ in the complemented MK418 strains indicates that transcriptional activation involving NosR was also provided by truncated or site-specifically modified NosR proteins. The shortest protein that still exhibited this activity was NosRb-His6. Since it could be isolated from cells, this clearly demonstrated the existence of a stable protein fragment. Topologically, NosRb-His6 is limited to the periplasmic domain and TM2. The function of NosR in nosZ expression is arcane since NosR has no features of a transcription factor, which is particularly evident with NosRb having no noteworthy cytoplasmic domain. The C-terminal metal centers may possibly have DNA-binding properties, but mutating or removing these features did not affect the amount of NosZ in a way that would be expected for a transcription factor. A sequence-predicted helix-turn-helix motif was shown to be irrelevant, as it is periplasmic (12, 13). NosR exhibits no winged helix-turn-helix domain like that of the membrane-bound transcription factor ToxR (11) and is not recognized as part of a two-component regulatory system, either of the classical type or of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factors (19), since the cognate components for interaction with the putative sensor, NosR, are missing. The only currently known factor which can be hypothesized to interact with NosR is the denitrification regulator DnrD. Unfortunately, the mechanism of DnrD activation is still obscure. We can sum up the current situation only thus far: nosR transcription acts positively on its own promoter and activates downstream genes without an operon structure (1, 13, 21, 38, 45).

In this study, we have provided direct evidence for the membrane-bound nature of NosR by solubilization and isolation of the protein. NosR is processed for domain translocation and membrane insertion and thereby loses a signal peptide, which includes the transmembrane helix TM1. Hence, our data indicate that NosR has a transmembrane core of five helices flanked on both sides by hydrophilic domains, which are fewer topological elements than suggested previously (3, 53). The N-terminal hydrophilic domain is periplasmic, as shown by the use of phoA reporter gene fusions with the codons for D242 and E392 (12). This topology results in an outside-inside orientation for TM2 and also suggests a regular array of the following transmembrane helices. It predicts a cytoplasmic location for the C-terminal Fe-S domain (3, 13, 53). The same topology was obtained from neural network modeling based on multiple sequence alignment (37). The hydrophobic region TM6 is problematic since it is variably predicted as one or two helices (the latter variant would result in the periplasmic location of the Fe-S domain). The C-terminal part of NosR has a structural analogue in NapH of E. coli (with the same CX3CP and Fe-S modules). Reporter gene fusions have indicated a cytoplasmic location of the Fe-S domain for NapH (4). A recent study of NosR from Paracoccus denitrificans shows agreement with the described topology (R. J. M. van Spanning, personal communication). NosR proteins of the genera Wautersia, Ralstonia, and Thiobacillus form a tight structural cluster with a C-terminal extension of about 150 amino acids which is not found in other orthologues. The topology of this NosR group may comprise a further transmembrane domain.

The flavin-binding domain of NosR is found in, among other proteins, the NqrC subunit of the Na+-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase of the genus Vibrio. NqrC was shown to carry FMN covalently bound as a phosphodiester to a threonine residue (17, 27, 52). Given the spectral evidence and the supporting flavin-binding consensus sequence, we suggest that NosR of P. stutzeri carries a flavin cofactor covalently bound to T163. The threonine residue is followed by a short α-helix as a structural element in the FMN-binding domain (49). This helix is also seen in hydropathy plots of NosR, and some algorithms predict that it is a transmembrane domain. Because of this element, the size of the periplasmic part had formerly been given different extensions. Figure 7 shows a comparison of sequences flanking the invariant threonine for the currently identified NosR proteins. Several sequences are newly deduced members from genome projects. The most remarkable new entry is from Lyngbya majuscula (7), which may be the first representative N2O-reducing cyanobacterium. Its nosR gene, together with a fragment of nosZ, is located next to a gene cluster for curacin A biosynthesis. The cyanobacterial NosR clusters phylogenetically with homologues from Silicibacter pomeroyi, Paracoccus denitrificans, and “Achromobacter cycloclastes” (proposed name).

FIG. 7.

Multiple sequence alignment of flavin-binding peptides of NosR proteins. The alignment was done with CLUSTAL X 1.83 and displayed with BOXSHADE software. The invariant threonine residue and a neighboring alanine are marked by asterisks; dots show groups of similar amino acids. Abbreviations (the GenBank identifier or URL of an internet source is given in parentheses after each species name): Acyc, A. cycloclastes ATCC 21921 (gi 2935350); Bjap, Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110 (gi 27348562); Bmal, Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344 (http://www.tigr.org); Bpse, Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk); Bmel, Brucella melitensis 16 M (gi 17985187); Bsui, Brucella suis 1330 (gi 23463617); Cpsy, Colwellia psychroerythraea 34H (http://www.tigr.org); Lmaj, L. majuscula 19L (gi 50082948); Mmag, Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum MS-1 (gi 23015286); Ngon, Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090 (http://www.genome.ou.edu/gono.html); Paer, P. aeruginosa PAO1 (gi 15598587); Pden, Paracoccus denitrificans PD1222 (gi 2370351); Pden1, NirI of Paracoccus denitrificans PD1222 (gi 5764059); Pflu, Pseudomonas fluorescens C7R12 (gi 11344616); Ppro, Photobacterium profundum SS9 (gi 46915947); Pstu, P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 (gi 462737); Weut, Wautersia (formerly Ralstonia) eutropha H16 (gi 32527250); Wmet, Wautersia metallidurans CH34 (gi 22978466); Rpal, Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 (gi 39935129); Rsol, Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 (gi 17549588); Smel, Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 (gi 14523755); Spom, S. pomeroyi DSS-3 (http://www.tigr.org); Tden, T. denitrificans ATCC 25259 (gi 52008101, http://www.jgi.doe.gov).

Deletion of the flavin-binding domain of NosR results in the phenotype of an electron donor mutant. We found a catalytically active enzyme but no whole-cell N2O-reducing activity. We suggest here a new function for NosR in the form of a redox role, with mature NosZ as the target, in addition to its role in nosZ transcription. Electron donation to NosZ can be direct or via an intermediate factor, for which copper proteins or c-type cytochromes have been suggested (reviewed in references 3, 53). If NosR receives electrons from the respiratory chain, it would have to be via a quinol or other group but not a heme group, since we found no evidence for heme in NosR. The requirement of an intermediate carrier can explain the observation made with Pseudomonas putida, a nondenitrifying bacterium. When nosR was coexpressed with nosZ and the nosD operon, an active holoenzyme was synthesized, but no whole-cell N2O-reducing activity was observed (47).

As an exception among the denitrifying bacteria, the N2O-respiring bacterium Wolinella succinogenes has no nosR gene. In this organims, NosZ has a c-type cytochrome fused to the C terminus as the putative electron entry site to CuA, apparently obviating a flavoprotein donor (39, 51). However, W. succinogenes retains in the form of the membrane protein NosH, with its CX3CP and Fe-S modules, a structural analogue to the C-terminal part of NosR (39), suggesting that these elements are functionally important for N2O reduction.

The Fe content, absence of heme, and preliminary evidence of acid-labile sulfur support the iron-sulfur protein nature of NosR. N2O respiration is coupled to energy conservation, as evident from the growth yield (24) and the observation that certain bacteria grow with N2O as an electron acceptor (25, 50). Electron transfer must be coupled to proton translocation for this function, which takes place at coupling sites provided by components of the aerobic, constitutive respiratory chain. Electron flow in NosR from the cytoplasmic Fe-S cluster to the flavin domain across the membrane would short-circuit energy conservation and therefore is unlikely to take place, but if it occurs at all, it may have a role in redox balancing.

We also consider activation of the enzyme or maintenance of the catalytically competent state as an alternative or concomitant redox function exerted by NosR on NosZ. Turnover inactivation of the enzyme, demonstrated in vitro for several N2O reductases (10, 41, 42), or as found in this study, of whole cells expressing mutated NosR, needs a compensating process, which is putatively provided by NosR. Reductive activation has been shown for the Pseudomonas nautica (16) and A. cycloclastes (6) reductases. Although we have isolated catalytically active NosZ species from NosR′ strains, their in vitro activities were low compared to those of the reductively activated species of both organisms mentioned above or of the base-activated enzyme of P. stutzeri (10). N2O respiration is immediately suppressed in favor of aerobic respiration when oxygen is present (55), which suggests an activity control mechanism for NosZ or oxygen-promoted inactivation.

NosZ proteins obtained from the background of a defective NosR protein show UV-visible spectral signatures for the presence of both copper centers, CuA and CuZ (Fig. 6). Hence, NosR does not provide functions for the assembly or biosynthesis of the metal center, as do the components encoded by the nosD operon (21, 47). However, the modification of CX3CP (TM6) or the deletion of the C-terminal half of the protein (truncation of NosR after TM2) led to an altered CuZ center (Table 1). This was similar to a NosZ form found after oxygen exposure of a frozen cell extract of Paracoccus pantotrophus, which resulted in the formation of the CuZ* variant (29, 33). The spectroscopic parameters of CuZ* are rather similar to those of CuZ, but the star form is redox locked versus ferricyanide and dithionite, even though it is catalytically active for N2O reduction. The spectra of NosZ induced by NosRb and NosRf represented mixed spectral signatures of CuA and CuZ, in which part of CuZ was converted to CuZ*. As described for Paracoccus pantotrophus (33), the 637-nm band of NosZ isolated from the NosRb and NosRf backgrounds was redox inert. Since CuZ* becomes manifest upon NosR mutation, it attains a physiological status and will have to be considered in the catalytic cycle.

Deletion of the flavin or Fe-S domain, on the other hand, did not change the NosZ properties. We interpreted the observation of distinct NosZ species depending upon the nature of the nosR mutation as indirect evidence for various functions being innate to the NosR protein. Since we now have the purified components on hand, it will be possible to study the interaction of NosR with NosZ and to address electron donor and activity aspects of this interaction in vitro.

Finally, the combination of CX3CP motifs and a polyferredoxin module is found in other redox proteins with putative regulatory or sensory functions (3, 4, 9, 22, 23, 28, 30, 32, 36, 38, 39). A mechanistic understanding of this structure will therefore have an impact on many metabolic systems, including N2O respiration. Our work has dissected functional elements of NosR and opened a way to study this faceted protein biochemically, suggesting starting points for its further functional exploration by the use of physiological genetics.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to H. Körner for assistance with sequence analyses. We thank M. Kurtić for purifying NosRb and R. J. M. van Spanning for communicating unpublished data. Preliminary sequence information incorporated in this article was made freely available by The Institute for Genomic Research, The Joint Genome Institute, The University of Oklahoma, and The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arai, H., M. Mizutani, and Y. Igarashi. 2003. Transcriptional regulation of the nos genes for nitrous oxide reductase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 149:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beinert, H. 1983. Semi-micro methods for analysis of labile sulfide and of labile sulfide plus sulfane sulfur in unusually stable iron-sulfur proteins. Anal. Biochem. 131:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berks, B. C., S. J. Ferguson, J. W. B. Moir, and D. J. Richardson. 1995. Enzymes and associated electron transport systems that catalyse the respiratory reduction of nitrogen oxides and oxyanions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1232:97-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brondijk, T. H. C., A. Nilavongse, N. Filenko, D. J. Richardson, and J. A. Cole. 2004. NapGH components of the periplasmic nitrate reductase of Escherichia coli K-12: location, topology and physiological roles in quinol oxidation and redox balancing. Biochem. J. 379:47-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, K., M. Tegoni, M. Prudêncio, A. S. Pereira, S. Besson, J. J. Moura, I. Moura, and C. Cambillau. 2000. A novel type of catalytic copper cluster in nitrous oxide reductase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:191-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, J. M., J. A. Bollinger, C. L. Grewell, and D. M. Dooley. 2004. Reductively activated nitrous oxide reductase reacts directly with substrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:3030-3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, Z., N. Sitachitta, J. V. Rossi, M. A. Roberts, P. M. Flatt, J. Jia, D. H. Sherman, and W. H. Gerwick. 2004. Biosynthetic pathway and gene cluster analysis of curacin A, an antitubulin natural product from the tropical marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. J. Nat. Prod. 67:1356-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charnock, J. M., A. Dreusch, H. Körner, F. Neese, J. Nelson, A. Kannt, H. Michel, C. D. Garner, P. M. H. Kroneck, and W. G. Zumft. 2000. Structural investigations of the CuA centre of nitrous oxide reductase from Pseudomonas stutzeri by site-directed mutagenesis and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1368-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chistoserdov, A. Y., L. V. Chistoserdova, W. S. McIntire, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1994. Genetic organization of the mau gene cluster in Methylobacterium extorquens AMI: complete nucleotide sequence and generation and characteristics of mau mutants. J. Bacteriol. 176:4052-4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyle, C. L., W. G. Zumft, P. M. H. Kroneck, H. Körner, and W. Jakob. 1985. Nitrous oxide reductase from denitrifying Pseudomonas perfectomarina, purification and properties of a novel multicopper enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 153:459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford, J. A., E. S. Krukonis, and V. J. DiRita. 2003. Membrane localization of the ToxR winged-helix domain is required for TcpP-mediated virulence gene activation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1459-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuypers, H., J. Berghöfer, and W. G. Zumft. 1995. Multiple nosZ promoters and anaerobic expression of nos genes necessary for Pseudomonas stutzeri nitrous oxide reductase and assembly of its copper centers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1264:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuypers, H., A. Viebrock-Sambale, and W. G. Zumft. 1992. NosR, a membrane-bound regulatory component necessary for expression of nitrous oxide reductase in denitrifying Pseudomonas stutzeri. J. Bacteriol. 174:5332-5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dower, W. J., J. F. Miller, and C. W. Ragsdale. 1988. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:6127-6145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farinha, M. A., and A. M. Kropinski. 1990. High efficiency electroporation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using frozen cell suspensions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 70:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh, S., S. I. Gorelsky, P. Chen, I. Cabrito, J. J. G. Moura, I. Moura, and E. Solomon. 2003. Activation of N2O reduction by the fully reduced μ4-sulfide bridged tetranuclear CuZ cluster in nitrous oxide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:15708-15709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi, M., Y. Nakayama, M. Yasui, M. Maeda, K. Furuishi, and T. Unemoto. 2001. FMN is covalently attached to a threonine residue in the NqrB and NqrC subunits of Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase from Vibrio alginolyticus. FEBS Lett. 488:5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heikkilä, M. P., U. Honisch, P. Wunsch, and W. G. Zumft. 2001. Role of the Tat transport system in nitrous oxide reductase translocation and cytochrome cd1 biosynthesis in Pseudomonas stutzeri. J. Bacteriol. 183:1663-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmann, J. D. 2002. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 46:47-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holloway, P., W. McCormick, R. J. Watson, and Y.-K. Chan. 1996. Identification and analysis of the dissimilatory nitrous oxide reduction genes, nosRZDFY, of Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 178:1505-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honisch, U., and W. G. Zumft. 2003. Operon structure and regulation of the nos gene region of Pseudomonas stutzeri, encoding an ABC-type ATPase for maturation of nitrous oxide reductase. J. Bacteriol. 185:1895-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn, D., M. David, O. Domergue, M.-L. Daveran, J. Ghai, P. R. Hirsch, and J. Batut. 1989. Rhizobium meliloti fixGHI sequence predicts involvement of a specific cation pump in symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J. Bacteriol. 171:929-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch, H.-G., C. Winterstein, A. S. Saribas, J. O. Alben, and F. Daldal. 2000. Roles of the ccoGHIS gene products in the biogenesis of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase. J. Mol. Biol. 297:49-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koike, I., and A. Hattori. 1975. Energy yield of denitrification: an estimate from growth yield in continuous cultures of Pseudomonas denitrificans under nitrate-, nitrite- and nitrous oxide-limited conditions. J. Gen. Microbiol. 88:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsubara, T. 1971. Studies on denitrification. XIII. Some properties of the N2O-anaerobically grown cell. J. Biochem. 69:991-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuirl, M. A., L. K. Nelson, J. A. Bollinger, Y.-K. Chan, and D. M. Dooley. 1998. The nos (nitrous oxide reductase) gene cluster from the soil bacterium Achromobacter cycloclastes: cloning, sequence analysis, and expression. J. Inorg. Biochem. 70:155-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakayama, Y., M. Yasui, K. Sugahara, M. Hayashi, and T. Unemoto. 2000. Covalently bound flavin in the NqrB and NqrC subunits of Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase from Vibrio alginolyticus. FEBS Lett. 474:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neidle, E. L., and S. Kaplan. 1992. Rhodobacter sphaeroides rdxA, a homolog of Rhizobium meliloti fixG, encodes a membrane protein which may bind cytoplasmic [4Fe-4S] clusters. J. Bacteriol. 174:6444-6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oganesyan, V. S., T. Rasmussen, S. Fairhurst, and A. J. Thomson. 2004. Characterisation of [Cu4S], the catalytic site in nitrous oxide reductase, by EPR spectroscopy. Dalton Trans. 2004:996-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Gara, J. P., J. M. Eraso, and S. Kaplan. 1998. A redox-responsive pathway for aerobic regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 180:4044-4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pages, J.-M., J. Anba, A. Bernadac, H. Shinagawa, A. Nakata, and C. Lazdunski. 1984. Normal precursors of periplasmic proteins accumulated in the cytoplasm are not exported post-translationally in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 143:499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preisig, O., R. Zufferey, and H. Hennecke. 1996. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixGHIS genes are required for the formation of the high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase. Arch. Microbiol. 165:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rasmussen, T., B. C. Berks, J. N. Butt, and A. J. Thomson. 2002. Multiple forms of the catalytic centre, CuZ, in the enzyme nitrous oxide reductase from Paracoccus pantotrophus. Biochem. J. 364:807-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen, T., B. C. Berks, J. Sanders-Loehr, D. M. Dooley, W. G. Zumft, and A. J. Thomson. 2000. The catalytic center in nitrous oxide reductase, CuZ, is a copper sulfide cluster. Biochemistry 39:12753-12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riester, J., W. G. Zumft, and P. M. H. Kroneck. 1989. Nitrous oxide reductase from Pseudomonas stutzeri, redox properties and spectroscopic characterization of different forms of the multicopper enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 178:751-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roh, J. H., and S. Kaplan. 2002. Interdependent expression of the ccoNOQP-rdxBHIS loci in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 184:5330-5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rost, B., P. Fariselli, and R. Casadio. 1996. Topology prediction for helical transmembrane proteins at 86% accuracy. Protein Sci. 5:1704-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders, N. F. W., E. N. G. Houben, S. Koefoed, S. de Weert, W. N. M. Reijnders, H. V. Westerhoff, A. P. N. de Boer, and R. J. M. van Spanning. 1999. Transcription regulation of the nir gene cluster encoding nitrite reductase of Paracoccus denitrificans involves NNR and NirI, a novel type of membrane protein. Mol. Microbiol. 34:24-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, J., O. Einsle, P. M. H. Kroneck, and W. G. Zumft. 2004. The unprecedented nos gene cluster of Wolinella succinogenes encodes a novel respiratory electron transfer pathway to cytochrome c nitrous oxide reductase. FEBS Lett. 569:7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smidt, H., M. van Leest, J. van der Oost, and W. M. de Vos. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of the cpr gene cluster in ortho-chlorophenol-respiring Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans. J. Bacteriol. 182:5683-5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snyder, S. W., and T. C. Hollocher. 1987. Purification and some characteristics of nitrous oxide reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6515-6525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.SooHoo, C. K., and T. C. Hollocher. 1991. Purification and characterization of nitrous oxide reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain P2. J. Biol. Chem. 266:2203-2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velasco, L., S. Mesa, C.-A. Xu, M. J. Delgado, and E. J. Bedmar. 2004. Molecular characterization of nosRZDFYLX genes coding for denitrifying nitrous oxide reductase of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 85:229-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viebrock, A., and W. G. Zumft. 1987. Physical mapping of transposon Tn5 insertions defines a gene cluster functional in nitrous oxide respiration by Pseudomonas stutzeri. J. Bacteriol. 169:4577-4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vollack, K.-U., and W. G. Zumft. 2001. Nitric oxide signaling and transcriptional control of denitrification genes in Pseudomonas stutzeri. J. Bacteriol. 183:2516-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West, S. E. H., H. P. Schweizer, C. Dall, A. K. Sample, and L. J. Runyen-Janecky. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 128:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wunsch, P., M. Herb, H. Wieland, U. M. Schiek, and W. G. Zumft. 2003. Requirements for CuA and Cu-S center assembly of nitrous oxide reductase deduced from complete periplasmic enzyme maturation in the nondenitrifier Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 185:887-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeats, C., S. Bentley, and A. Bateman. 2003. New knowledge from old: in silico discovery of novel protein domains in Streptomyces coelicolor. BMC Microbiol. 3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshinari, T. 1980. N2O reduction by Vibrio succinogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 39:81-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, C.-S., T. C. Hollocher, A. F. Kolodziej, and W. H. Orme-Johnson. 1991. Electron paramagnetic resonance observations on the cytochrome c-containing nitrous oxide reductase from Wolinella succinogenes. J. Biol. Chem. 266:2199-2202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, W., Y. V. Bertsova, B. Feng, P. Tsatsos, M. L. Verkhovskaya, R. B. Gennis, A. V. Bogachev, and B. Barquera. 1999. Sequencing and preliminary characterization of the Na+-translocating NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase from Vibrio harveyi. Biochemistry 38:16246-16252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zumft, W. G. 1997. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:533-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zumft, W. G., K. Döhler, and H. Körner. 1985. Isolation and characterization of transposon Tn5-induced mutants of Pseudomonas perfectomarina defective in nitrous oxide respiration. J. Bacteriol. 163:918-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zumft, W. G., and P. M. H. Kroneck. 1990. Metabolism of nitrous oxide. FEMS Symp. Ser. 56:37-55. [Google Scholar]