Abstract

We report the identification of a novel chromosome cluster of genes in Vibrio anguillarum 775 that includes redundant functional homologues of the pJM1 plasmid-harbored genes angE and angC that are involved in anguibactin biosynthesis. We also identified in this cluster a chromosomal angA gene that is essential in anguibactin biosynthesis.

The fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum causes a fatal hemorrhagic septicemic disease in salmonids (1). Some of the virulent serotype O1 strains of this bacterium harbor the pJM1 plasmid essential for pathogenicity, encoding an iron-sequestering system that includes almost all the biosynthetic genes for the siderophore anguibactin (Fig. 1A) (12, 13, 14, 15, 29, 31) as well as those for the cognate transport proteins (2, 3, 4, 5, 18, 19).

FIG. 1.

Scheme of the anguibactin biosynthesis pathway and arrangement of biosynthetic genes in the plasmid and chromosome clusters. (A) Anguibactin biosynthesis pathway. The AngE, AngA, and AngC enzymes are described in the text. The asterisk beside AngD means that this is a putative enzyme whose activity has yet to be proven. For a more detailed pathway, see Crosa and Walsh (13). (B) Genetic arrangement of the angC, angE, and angA genes in the pJM1 plasmid and chromosomal DNA. The intergenic region located between angAch and angCch and the angCp promoter are also shown. In this work we identified a chromosomal dahp gene, a homologue to that encoded on the pJM1 plasmid (15), that encodes a predicted translated protein similar to 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthases. The first codon and the −10 and −35 regions of each gene are underlined; +1 indicates the transcription start sites of each gene determined using primer extension analysis (26). The direction of transcription is denoted by horizontal arrows. For the primer extension analysis, the RNAWiz (Ambion) was used to extract total RNA from V. anguillarum strain 775 grown in CM9 supplemented with 2.5 μM EDDA. The primers used in these experiments were as follows: C2 (5′ TAGCTGATTAGCCATTTTTGAAAACCC 3′) located 45 bp downstream from the start codon of the angCch gene, CPB (5′ GGATCCAAAAAAGAACGGTGATTTTAA 3′) located 118 bp downstream from the start codon of the angCp gene, and A3 (5′ ATTTTTATCCGTCGCTACAACTCG 3′) and CCK (5′ GGTACCATTTTCCTAACTTTACTCCGTT 3′) located 114 and 8 bp downstream from the start codon of the angAch gene, respectively. The symbols shown with the angAp gene and downstream of the angEch gene indicate a frame shift and a transcriptional terminator, respectively. The double diagonal lines between the isv-A2 and dahp genes in the plasmid cluster indicate approximately 12 kbp. The putative Fur boxes are shaded, and nucleotides identical to the E. coli Fur consensus (16) are shown in bold characters.

The existence of additional chromosome- and plasmidborne genes for synthesis and activation of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA), a precursor of anguibactin, and 2,3-dihydro-2,3-DHBA, a precursor of DHBA, has also been suggested (17, 21, 31). We report here the identification and analysis of these novel chromosome- and plasmidborne gene clusters.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. V. anguillarum was grown at 25°C, while Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium were grown at 37°C (31). For iron-restricted conditions, V. anguillarum was grown in chemically defined minimal medium CM9 (12) supplemented with different concentrations of the iron chelator ethylenediamine-di-(o-hydroxyphenylacetic) acid (EDDA), while for iron-rich growth, ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) at 4 μg/ml was used.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| V. anguillarum strains | ||

| 775 (pJM1) | Wild-type Pacific Ocean prototype | Laboratory stock |

| H775-3 | Plasmidless derivative of 775 | Laboratory stock |

| 775::Tn1-5 (pJHC-91) | Anguibactin production deficient | 29 |

| 775::Tn1-6 (pJHC9-8) | Anguibactin production and transport deficient | 29 |

| 775 MET11 | fur | 30 |

| AC1 | 775 ΔangEp | This work |

| AC2 | 775 ΔangEch | This work |

| AC3 | 775 ΔangEp ΔangEch | This work |

| AC4 | AC3 complemented with the angEp gene | This work |

| AC5 | AC3 complemented with the angEch gene | This work |

| AC6 | AC3 harboring the vector pMMB208 | This work |

| AC7 | 775 ΔangAch | This work |

| AC8 | AC7 complemented with the angAch gene | This work |

| AC9 | AC7 complemented with the angAp gene | This work |

| AC10 | AC7 harboring the vector pMMB208 | This work |

| AC11 | 775ΔangCp | This work |

| AC12 | 775 ΔangCch | This work |

| AC13 | 775 ΔangCp ΔangCch | This work |

| AC14 | AC13 complemented with the angCp gene | This work |

| AC15 | AC13 complemented with the angCch gene | This work |

| AC16 | AC13 harboring the vector pMMB208 | This work |

| AC17 | 775 ΔangCp ΔangCch ΔmenF | This work |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 gyrA96 thi-1 ΔlacU169 relA1 (φ80lacZΔM15) | Laboratory stock |

| MM294 | F−endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 λ− harboring plasmid pRK201 | Laboratory stock |

| S17-1 λpir | thi pro hsdR hsdM+recA RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 λpir | 28 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains | ||

| enb1 | Enterobactin production deficient (uses enterobactin as iron source) | 25 |

| enb7 | Enterobactin production deficient (uses enterobactin and DHBA as iron sources) | 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Kmr Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pMMB208 | incQ lac1q Ωcat ΩPtac Cmr | 24 |

| pDM4 | Suicide plasmid R6K origin; Cmr | 22 |

| pALE1 | pDM4 harboring ΔangEp | This work |

| pALE2 | pDM4 harboring ΔangEch | This work |

| pALE3 | pDM4 harboring ΔangAch | This work |

| pALE4 | pMMB208 harboring angEp | This work |

| pALE5 | pMMB208 harboring angEch | This work |

| pALE6 | pMMB208 harboring angAp | This work |

| pALE7 | pMMB208 harboring angAch | This work |

| pALE8 | pDM4 harboring ΔangCp | This work |

| pALE9 | pDM4 harboring ΔangCch | This work |

| pALE10 | pMMB208 harboring angCp | This work |

| pALE11 | pMMB208 harboring angCch | This work |

| pALE12 | pDM4 harboring ΔmenF | This work |

| p32 | 199-bp fragment of the angEch gene cloned into pCR2.1 Topo | This work |

| pQSH6 | 420-bp SaI-ClaI fragment of the aroC gene cloned in pBluescript-II SK+ | 14 |

Identification of a chromosomeborne gene cluster with homology to anguibactin biosynthetic genes.

The sequence of the pJM1 plasmid revealed an open reading frame 42 (ORF42), named angE, that could be involved in the activation of DHBA (15). To determine the functionality of this gene, we constructed the angE mutant AC1 by generating an unmarked, in-frame deletion as described previously (22). Bioassays listed in Table 2 and the halo observed on chrome azurol S (CAS) plates (27) (Fig. 2A) demonstrated that the siderophore anguibactin was synthesized in this mutant. Therefore, either the angE gene is not involved in anguibactin biosynthesis, or there is an additional gene harbored in the chromosome, complementing this function. Using partial angE sequence information obtained from the analysis of the V. anguillarum 775 genome (unpublished data), we amplified by inverse PCR an ORF with a predicted translated protein, a 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-AMP ligase, comparable to VibE from V. cholerae (EMBL accession no. AAC45927; 80% similarity and 60% identity) (6). Sequencing the upstream region of this gene revealed two other complete ORFs (Fig. 1B). One of them, named angA, showed similarity to proteins with a 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxybenzoate dehydrogenase activity, such as the VibA protein from V. cholerae (EMBL accession no. AAC4924; 73% similarity and 54% identity). The other ORF, named angC, would encode a predicted protein with similarity to the isochorismate synthase VibC from V. cholerae (EMBL accession no. AAC45925; 83% similarity and 62% identity).

TABLE 2.

Bioassay experiments with various indicator strainsa

| Strain tested and relevant genotype | Growth of V. anguillarum indicator strainb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| H775-3 | 775::Tn1-5 (pJHC-91) | 775::Tn1-6 (pJHC9-8) | |

| AC1 ΔangEp | − | + | − |

| AC2 ΔangEch | − | + | − |

| AC3 ΔangEp ΔangEch | − | − | − |

| AC4 ΔangEp ΔangEch pALE4 (angEp) | − | + | − |

| AC5 ΔangEp ΔangEch pALE5 (angEch) | − | + | − |

| AC6 ΔangEp ΔangEch pMMB208 | − | − | − |

| AC7 ΔangAch | − | − | − |

| AC8 ΔangAch pALE7 (angAch) | − | + | − |

| AC9 ΔangAch pALE6 (angAp) | − | − | − |

| AC10 ΔangAch pMMB208 | − | − | − |

| AC11 ΔangCp | − | + | − |

| AC12 ΔangCch | − | + | − |

| AC13 ΔangCp ΔangCch | − | +/− | − |

| AC14 ΔangCp ΔangCch pALE10 (angCp) | − | + | − |

| AC15 ΔangCp ΔangCch pALE11 (angCch) | − | + | − |

| AC16 ΔangCp ΔangCch pMMB208 | − | +/− | − |

| AC17 ΔangCp ΔangCch ΔmenF | − | − | − |

Supernatants were obtained from cultures of the various strains to be tested and grown under iron-limiting conditions for 16 to 20 h. Five microliters of each supernatant was spotted onto CM9 agar minimal media plates supplemented with 2.5 μM EDDA that had previously been seeded with the indicator strains of V. anguillarum. The plates were examined for halos of growth after 24 to 72 h.

V. anguillarum mutants deficient in the iron uptake system included 775::Tn1-6 (pJHC9-8), deficient in the production of the anguibactin siderophore and its receptor; and 775::Tn1-5(pJHC-91), receptor proficient and siderophore deficient. Symbols: +, presence of growth halo; +/−, presence of a small growth halo after 48 h; −, no growth.

FIG. 2.

Detection of siderophore production on CAS agar plates in V. anguillarum strains. (A) From left to right: wild-type V. anguillarum strain 775, AC1 (ΔangEp), AC2 (ΔangEch), and AC3 (ΔangEp ΔangEch). (B) Genetic complementation of the double ΔangEp ΔangEch (AC3) mutant strain with each wild-type angE gene. From left to right: the AC3 strain complemented with the angEp gene (AC4), complemented with the angEch gene (AC5), and harboring the empty vector pMMB208 (AC6). (C) From left to right: AC11 (ΔangCp), AC12 (ΔangCch), AC13 (ΔangCp ΔangCch), and AC17 (ΔangCp ΔangCch ΔmenF). (D) Genetic complementation of the double ΔangCp ΔangCch (AC13) mutant strain with each wild-type angC gene. From left to right: the AC13 strain complemented with the angCp gene (AC14), complemented with the angCch gene (AC15), and harboring the empty vector pMMB208 (AC16). (E) From left to right: AC7 (ΔangAch mutant strain) and the ΔangAch (AC7) mutant strain complemented with the angAch gene (AC8), complemented with the angAp gene (AC9), and harboring the empty vector pMMB208 (AC10). For the complementation experiments the plates were supplemented with 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and 1 mM IPTG to induce the genes cloned under the control of the inducible Ptac promoter.

The proteins encoded by this chromosomal cluster show similarities to the homologues encoded on the pJM1 plasmid; however, they are not identical. The chromosome-encoded AngC protein shows 86% similarity and 70% identity to the plasmid-encoded AngC protein, while the chromosome-encoded AngE presents 78% similarity and 60% identity to the plasmid-encoded AngE protein that is 6 amino acids shorter. Although the chromosomal angA gene is complete, there is a frameshift mutation in the plasmid homologue caused by a single nucleotide insertion (15). If this mutation is theoretically reversed, the identity of the putative encoded protein with the chromosomal AngA is 32%.

The angE, angC, and angA genes borne on the chromosome and the pJM1 plasmid will be identified by the subscripts ch and p, respectively.

Comparison of the genetic arrangements of the chromosome and pJM1 plasmid clusters.

The genetic organization of the novel chromosomal cluster resembles that described for V. cholerae (32). However, it shows differences with respect to the version encoded on the pJM1-like plasmids (15, 31) (Fig. 1B). For example, there is divergence in the upstream regions of both angC genes: while in the angCp upstream region there is a transposase gene, in the corresponding region of angCch the angAch gene is found (Fig. 1B). In contrast, downstream of angEch we identified an ORF that encodes a predicted protein with similarity to the isochorismate lyase AngB, located in the same region as that in the pJM1-like plasmids (Fig. 1B) (15, 31). It is thus possible that transposition events might have occurred on the plasmid, resulting in genetic rearrangements. Since the chromosomal and plasmid homologues differ at both the nucleotide and amino acid levels, it is possible that they evolved independently and that the latter were acquired by horizontal transfer. One other alternative is that they are paralogue genes whose original duplication event was not recently accomplished.

Involvement of angE and angC chromosome and plasmid genes in the biosynthesis of anguibactin.

Since the angEp null mutant AC1 is able to synthesize anguibactin, the following new strains were constructed: the single angEch (AC2) and double angEp angEch (AC3) mutants. The CAS assays and bioassays showed that the double mutant cannot synthesize anguibactin, while the single angEch mutant is as proficient in siderophore production as the angEp mutant (Fig. 2A and Table 2). It is thus clear that both the chromosome and plasmid angE genes encode functional AngE proteins. This result was confirmed by complementing the double angE mutant with each one of the angE genes (Fig. 2B and Table 2).

The same functional redundancy was also found with the chromosome and plasmid homologues of angC by using the single angCp and angCch mutants (Fig. 2C and Table 2) and confirmed by complementation of the double angC mutant AC13 (Fig. 2D and Table 2). However, this double mutant could produce small amounts of anguibactin (Fig. 2C and Table 2). Two plausible hypotheses can explain these results: (i) existence of a second chromosome angC homologue and (ii) presence of an isoenzyme capable of complementing the isochorismate synthase activity. It was previously demonstrated that MenF, which is involved in the biosynthesis of menaquinones, synthesizes isochorismate that results in the production of low amounts of enterobactin in an E. coli entC mutant (8). By performing protein sequence alignment of the MenF homologues from E. coli (P38051) and several Vibrio species, we designed degenerated primers that allowed us to clone the putative V. anguillarum menF gene. The predicted translated sequence of this gene shows similarity with MenF from E. coli (52% similarity and 38% identity). We then generated a deletion in this putative menF gene in the double angC mutant AC13, resulting in the complete suppression of anguibactin production (Fig. 2C). The fact that the AC13 strain can produce small amounts of anguibactin indicates that there is cross talk between the two pathways at the level of the isochorismic acid produced by the V. anguillarum MenF protein as previously described for E. coli (8).

The chromosomal angA gene is essential for anguibactin production.

To determine whether both angAp and angAch can intervene in anguibactin biosynthesis, we constructed an angAch mutant (AC7). This mutation resulted in the abolishment of the siderophore synthesis (Fig. 2E and Table 2), underscoring that the frame shift present in the angAp gene has impaired its functionality. The complementation experiments confirm that only the wild-type angAch gene, not angAp, could restore anguibactin biosynthesis in the AC7 strain (Fig. 2E and Table 2). Bioassays using S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains (26) and chemical determinations (7) indicated that DHBA synthesis was abolished in this mutant. The ability of DHBA to restore the growth of this mutant under iron-limiting conditions corroborated that AngAch is indeed involved in the biosynthesis of this anguibactin precursor (data not shown).

Transcriptional analysis of the plasmid and chromosomal angC, angE, and angA genes.

We determined, using reverse transcription-PCR, that in each of the chromosomal and plasmid gene clusters the angCE genes are transcribed as an operon (data not shown). Figure 1B shows the transcriptional start points of these two operons as well as the two different transcription start points for the angAch gene. This figure also shows a schematic diagram depicting the overlap between the divergent transcripts of angAch and angCEch as determined in the primer extension analysis (26). The in silico analysis of the angCEch, angCEp and angAch promoters showed sequences with high identity to those described for the canonic Fur box (16) (Fig. 1B). In the case of angCEch and angAch, this analysis suggests that Fur could control the expression of these genes by binding at a unique site.

We also determined that the transcription of both angCE operons was regulated in an iron- and Fur protein-dependent manner using RNase protection assay (RPA) (Fig. 3). We found that cultures grown in CM9 and CM9 plus EDDA expressed the chromosomal and plasmid angCE operons, while the presence of iron in CM9 leads to a complete repression of these genes (Fig. 3). It is important to note that the iron concentration in CM9 is sufficiently low to induce the expression of the anguibactin iron uptake system (3). In contrast with our results, Liu et al. (21) have recently shown that the angE gene harbored in a pJM1-like plasmid was not repressed in iron-rich conditions. The differences between our results and those observed by Liu et al. could be due to the different strains used or their specific experimental conditions. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that in V. anguillarum 775 other environmental signals or growth conditions could preferentially induce the plasmid or chromosome angE genes.

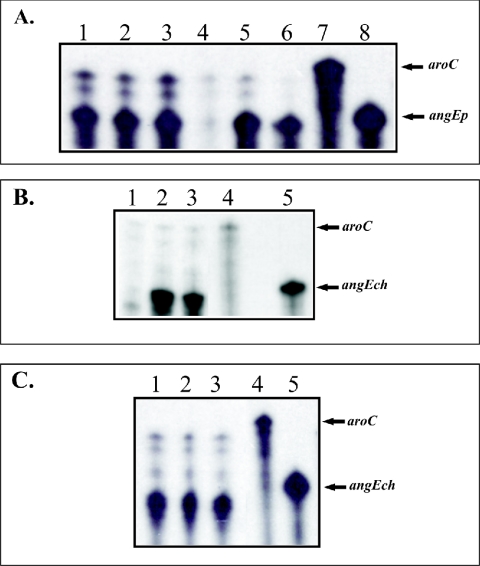

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional regulation analysis by RPA of the angEp and angEch genes. Total RNA was harvested from each strain grown under the conditions indicated for each lane. The riboprobes were synthesized using the Maxiscript T7/T3 kit from Ambion. In these experiments we used the aroC gene as an internal control because it was previously established that this gene is not regulated by iron (9). For aroC we used the plasmid pQSH6 (linearized with RsaI) (10, 15) and p32 for angEch gene. For the angEp homologue we designed the primers EPPU (5′ CCGATAGATATCATCACGAAA 3′) and EPPRT7 (5′ TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGCGTAAAATCCGTTTTTATC 3′). The RPA assay was performed using the RPA III kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's specifications. Specific transcripts for aroC, angEch, and angEp were detected using the riboprobes synthesized as described above. (A) Analysis of the angEp gene. Lanes: 1, 2, and 3, RNA extracted from the V. anguillarum 775 MET 11 fur strain grown in CM9 supplemented with 4 μg of FAC, CM9, and CM9 supplemented with 2.5 μM EDDA/ml, respectively; 4, 5, and 6, RNA extracted from V. anguillarum strain 775 grown under the same conditions as described previously; 7, aroC riboprobe; 8, angEp riboprobe. (B) Analysis of the angEch gene. Lanes 1, 2, and 3: RNA extracted from V. anguillarum strain 775 grown in CM9 supplemented with 4 μg of FAC, CM9, and CM9 supplemented with 2.5 μM EDDA/ml, respectively. (C) Lanes 1, 2, and 3: same as described for panel B but using RNA from the V. anguillarum fur mutant strain. Lanes 4 and 5 of both panels show the aroC and angEch riboprobes.

The transcriptional analysis of angAch indicated that this gene is also regulated by the iron concentration in a Fur-dependent manner (data not shown).

Conclusion.

From our results it is reasonable to group the anguibactin biosynthesis genes in V. anguillarum 775 into those that are harbored only by the pJM1 plasmid (e.g., angM, angR, angT, angU, angN, and angH), those harbored by both the plasmid and the chromosome (e.g., angE and angC), and those harbored only by the chromosome (e.g., angA). The chromosomal gene cluster described here could have been the remains of an earlier cluster involved in the biosynthesis of an ancestral DHBA-based siderophore. In this regard, it has been previously demonstrated that several plasmidless serotype O1 strains and all the plasmidless serotype O2 strains of V. anguillarum synthesize a chromosomally encoded catechol-type siderophore unrelated to anguibactin (11, 20). Since this chromosomally encoded siderophore can be utilized by the 775 strain as an iron source (20), it is possible that at some point in the evolution of this pathogen, an ancestor of this strain had the capability to synthesize this siderophore and that one or more chromosomal genes involved in its biosynthesis were silenced. Chance and necessity (23) may have selected those organisms that by horizontal transfer acquired the new plasmid-mediated anguibactin biosynthesis and uptake genes. The lack of a functional angAp gene resulted in dependence of this incomplete plasmid system on the host angAch gene. The important role of the anguibactin system in virulence strongly suggests that the newly acquired plasmid-mediated system, although partially duplicated in the chromosome, provided an evolutionary advantage to V. anguillarum 775 in its natural environment. Thus, our study generates new questions on the intersection of plasmid biology and the evolution of bacterial virulence.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The nucleotide sequences described above were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers AY738106 and AY738107.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants AI19018 and GM64600 from the National Institutes of Health to J.H.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Actis, L. A., M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1999. Vibriosis, vol. 3. Cab International Publishing, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 2.Actis, L. A., W. Fish, J. H. Crosa, K. Kellerman, S. R. Ellenberger, F. M. Hauser, and J. Sanders-Loehr. 1986. Characterization of anguibactin, a novel siderophore from Vibrio anguillarum 775(pJM1). J. Bacteriol. 167:57-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Actis, L. A., S. A. Potter, and J. H. Crosa. 1985. Iron-regulated outer membrane protein OM2 of Vibrio anguillarum is encoded by virulence plasmid pJM1. J. Bacteriol. 161:736-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Actis, L. A., M. E. Tolmasky, L. M. Crosa, and J. H. Crosa. 1995. Characterization and regulation of the expression of FatB, an iron transport protein encoded by the pJM1 virulence plasmid. Mol. Microbiol. 17:197-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Actis, L. A., M. E. Tolmasky, D. H. Farrell, and J. H. Crosa. 1988. Genetic and molecular characterization of essential components of the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid-mediated iron-transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 263:2853-2860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnow, E. L. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 2,3-dihydroxy-phenylalanine tyrosine mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 118:531-537. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buss, K., R. Muller, C. Dahm, N. Gaitatzis, E. Skrzypczak-Pietraszek, S. Lohmann, M. Gassen, and E. Leistner. 2001. Clustering of isochorismate synthase genes menF and entC and channeling of isochorismate in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1522:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Q., L. A. Actis, M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1994. Chromosome-mediated 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid is a precursor in the biosynthesis of the plasmid-mediated siderophore anguibactin in Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 176:4226-4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, Q., A. M. Wertheimer, M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1996. The AngR protein and the siderophore anguibactin positively regulate the expression of iron-transport genes in Vibrio anguillarum. Mol. Microbiol. 22:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conchas, R. F., M. L. Lemos, J. L. Barja, and A. E. Toranzo. 1991. Distribution of plasmid- and chromosome-mediated iron uptake systems in Vibrio anguillarum strains of different origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2956-2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosa, J. H. 1980. A plasmid associated with virulence in the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum specifies an iron-sequestering system. Nature 284:566-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosa, J. H., and C. T. Walsh. 2002. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:223-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Lorenzo, M., S. Poppelaars, M. Stork, M. Nagasawa, M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 2004. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase with a novel domain organization is essential for siderophore biosynthesis in Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 186:7327-7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Lorenzo, M., M. Stork, M. E. Tolmasky, L. A. Actis, D. Farrell, T. J. Welch, L. M. Crosa, A. M. Wertheimer, Q. Chen, P. Salinas, L. Waldbeser, and J. H. Crosa. 2003. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pJM1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain 775. J. Bacteriol. 185:5822-5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escolar, L., J. Perez-Martin, and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. Opening the iron box: transcriptional metalloregulation by the Fur protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:6223-6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmstrom, K., and L. Gram. 2003. Elucidation of the Vibrio anguillarum genetic response to the potential fish probiont Pseudomonas fluorescens AH2, using RNA-arbitrarily primed PCR. J. Bacteriol. 185:831-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jalal, M. A. F., M. B. Hossain, D. van der Helm, J. Sanders-Loehr, L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1989. Structure of anguibactin, a unique plasmid-related bacterial siderophore from the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111:292-296. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koster, W. L., L. A. Actis, L. S. Waldbeser, M. E. Tolmasky, and J. H. Crosa. 1991. Molecular characterization of the iron transport system mediated by the pJM1 plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum 775. J. Biol. Chem. 266:23829-23833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemos, M. L., P. Salinas, A. E. Toranzo, J. L. Barja, and J. H. Crosa. 1988. Chromosome-mediated iron uptake system in pathogenic strains of Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 170:1920-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, Q., Y. Ma, H. Wu, M. Shao, H. Liu, and Y. Zhang. 2004. Cloning, identification and expression of an entE homologue angE from Vibrio anguillarum serotype O1. Arch Microbiol. 181:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milton, D. L., R. O'Toole, P. Horstedt, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. Flagellin A is essential for the virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 178:1310-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monod, J. 1971. Chance and necessity. Knopf, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Morales, V. M., A. Backman, and M. Bagdasarian. 1991. A series of wide-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollack, J. R., and J. B. Neilands. 1970. Enterobactin, an iron transport compound from Salmonella typhimurium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 38:989-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, B., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Schwyn, B., and J. B. Neilands. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:787-796. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolmasky, M. E., L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1988. Genetic analysis of the iron uptake region of the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1: molecular cloning of genetic determinants encoding a novel trans activator of siderophore biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 170:1913-1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolmasky, M. E., A. M. Wertheimer, L. A. Actis, and J. H. Crosa. 1994. Characterization of the Vibrio anguillarum fur gene: role in regulation of expression of the FatA outer membrane protein and catechols. J. Bacteriol. 176:213-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welch, T. J., S. Chai, and J. H. Crosa. 2000. The overlapping angB and angG genes are encoded within the trans-acting factor region of the virulence plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum: essential role in siderophore biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:6762-6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyckoff, E. E., J. A. Stoebner, K. E. Reed, and S. M. Payne. 1997. Cloning of a Vibrio cholerae vibriobactin gene cluster: identification of genes required for early steps in siderophore biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 179:7055-7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]