Abstract

Phenol is a man-made as well as a naturally occurring aromatic compound and an important intermediate in the biodegradation of natural and industrial aromatic compounds. Whereas many microorganisms that are capable of aerobic phenol degradation have been isolated, only a few phenol-degrading anaerobic organisms have been described to date. In this study, three novel nitrate-reducing microorganisms that are capable of using phenol as a sole source of carbon were isolated and characterized. Phenol-degrading denitrifying pure cultures were obtained by enrichment culture from anaerobic sediments obtained from three different geographic locations, the East River in New York, N.Y., a Florida orange grove, and a rain forest in Costa Rica. The three strains were shown to be different from each other based on physiologic and metabolic properties. Even though analysis of membrane fatty acids did not result in identification of the organisms, the fatty acid profiles were found to be similar to those of Azoarcus species. Sequence analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA also indicated that the phenol-degrading isolates were closely related to members of the genus Azoarcus. The results of this study add three new members to the genus Azoarcus, which previously comprised only nitrogen-fixing species associated with plant roots and denitrifying toluene degraders.

Phenol is a natural as well as a man-made aromatic compound. Natural phenolic compounds and their derivatives are present everywhere in the environment. Plant roots exude a variety of phenolic compounds, including 4-hydroxybenzoate and ferulic, p-coumaric, vanillic, cinnamic, and syringic acids (32). Phenolic compounds also enter the environment as intermediates during the biodegradation of natural polymers containing aromatic rings, such as lignins and tannins, and from aromatic amino acid precursors. In addition, they may also enter the environment as intermediates during the biodegradation of xenobiotic compounds. Phenol pollution is associated with pulp mills, coal mines, refineries, wood preservation plants, and various chemical industries, as well as their wastewaters. Studies on the toxicity of phenol to sediment bacteria in phenol-contaminated sites have shown that bacteria can adapt to ambient phenol concentrations, but increasing phenol concentrations appear to decrease overall phenol biodegradation (7, 8).

Despite the fact that phenols are present in most soils and sediments, only a few anaerobic phenol-degrading microorganisms have been isolated and characterized. Whereas microorganisms capable of aerobic phenol degradation were described as early as 1908 (33), the first report of an obligately anaerobic phenol-degrading bacterium dates from 1986 and pertained to Desulfobacterium phenolicum (3). Recently, two other sulfate-reducing phenol-degrading organisms have been described (5, 16). Phenol degradation under methanogenic conditions has also been described, and several investigators have been able to isolate or identify organisms from methanogenic cocultures which are able to perform the first step(s) in the degradation of phenol under methanogenic conditions (15, 21, 38). Denitrifying phenol-degrading isolates that were first described in 1977 could grow in phenol-containing nutrient broth, but the growth was minimal when phenol was the only carbon source (4). Only two pure cultures of denitrifying bacteria that are able to use phenol as a sole source of carbon and energy, strains K172 and S100, have been described previously (36). Strain K172 has been used in studies of the biochemical pathways of both anaerobic phenol degradation and anaerobic toluene degradation (17, 18, 30). This organism was named Thauera aromatica and was classified as a new species of the genus Thauera (2), which previously comprised only one species, the selenate-reducing organism Thauera selenatis (23). This paper describes the isolation and characterization of three new phenol-degrading denitrifying microorganisms that were isolated from sediments from different geographic locations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources of bacteria.

The phenol-degrading denitrifying organisms used in this study were isolated from anaerobic sediments from various geographic locations; strain PH002 was isolated from the East River in New York, N.Y. (23rd Street) (26), strain FL05 was isolated from a drainage ditch in a Florida orange grove (along Route 64 in Manatee County), and strain CR23 was isolated from a small stream in the rain forest of Carara National Park in Costa Rica (less than 1 mile from the ranger station). The sediments were stored in closed containers at 4°C before use. The following strains were used for comparison: T. selenatis ATCC 55363, T. aromatica K172 (= DSM 6984), Azoarcus evansii DSM 6898, Azoarcus indigens LMG 9092, and Azoarcus tolulyticus Tol4 (= ATCC 51758).

Growth medium and isolation and cultivation conditions.

A defined mineral salts medium was used for isolation and cultivation of the phenol-degrading strains (34). Strain PH002 had been previously isolated and maintained in our laboratory culture collection. Isolations from the other two sites were carried out in this study. Enrichment cultures were prepared from an argon-sparged sediment slurry prepared in the defined mineral salts medium (2:1, wt/vol). Ten-milliliter portions of this slurry were added to 90-ml portions of argon-sparged medium in 160-ml serum bottles. The bottles were closed with neoprene rubber stoppers. Phenol was added at a starting concentration of 0.5 mM. Cultures were incubated without shaking at 30°C and were monitored for phenol loss and turbidity due to bacterial growth. The phenol was lost rapidly, within 2 or 3 days, even in the initial enrichment cultures. Periodically, when phenol was depleted, 0.5 mM was added, and nitrate (10 mM) was added when phenol loss halted. The cultures were diluted 10-fold twice, and after each dilution 0.5 mM phenol was added three times. After the last addition of phenol 10 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared. Colonies of phenol-degrading organisms were obtained from the highest dilutions by using agar shake tubes containing 0.4 mM phenol and 1 mM nitrate and were transferred to tubes containing 5 ml of mineral medium, 0.5 mM phenol, and 5 mM nitrate under an argon headspace. The cultures were checked for purity by plating on tryptic soy agar (TSA), as well as by microscopic observation. Pure cultures were maintained in serum bottles on medium containing 0.5 to 1 mM phenol and 5 to 10 mM nitrate under an argon headspace. Initially, 10 strains were isolated from the Costa Rican sediment, and three strains were isolated from the Florida sediment. The physiologic properties, metabolic versatilities, fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) profiles, and 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences (only the first 450 bp) of all of these isolates were determined. The characteristics were found to be identical for the isolates from each sediment, and therefore only one representative isolate from each source (strains CR23 and FL05 from Costa Rica and Florida, respectively) is discussed below.

Analytical methods.

Phenol concentrations were measured by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.). The solvent used was a 60:38:2 (vol/vol/vol) mixture of methanol (HPLC grade; J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, N.J.), deionized water, and glacial acetic acid (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, N.J.). Nitrate and nitrite concentrations were monitored by ion chromatography (Dionex, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and dinitrogen were analyzed with a gas chromatograph (model 1200; Fisher Scientific). Bacterial growth was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm with a Shimadzu model UV240 spectrophotometer. Degradation or transformation of the aromatic carbon sources other than phenol was determined by UV spectrophotometry with the Shimadzu model UV 240 spectrophotometer by scanning a range of wavelengths between 200 and 360 nm. Some of the transformation products produced during aerobic growth were identified by HPLC analysis by using pure compounds as references.

Characterization of the isolates.

Cell morphology was determined by phase-contrast microscopy and electron microscopy. Motility was assessed by direct microscopic observation during growth and by testing the ability of the strains to migrate from the point of inoculation through semisolid (0.3%) agar plates containing 20 mM succinate (1). The pH range and optimum pH for growth for each strain were determined by monitoring the residual phenol concentrations in cultures inoculated into medium having different initial pH values (pH 6.5 to 8.5); a 5% (vol/vol) inoculum and a starting phenol concentration of 0.5 mM were used in these experiments. The final pH was measured as well. The highest concentration of phenol at which each isolate initiated growth (i.e., the phenol tolerance) was determined by monitoring the optical densities of cultures growing on phenol at initial concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 4 mM. The presence of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) was determined microscopically by the appearance of sudanophilic inclusion bodies (6), as well as by extraction of the polymer followed by spectrophotometric analysis of the dehydrated hydrolyzed monomer crotonate (20). The metabolic versatilities of the isolates under denitrifying conditions were determined in glass screw-cap tubes (Bellco Glass, Vineland, N.J.) containing 5 ml of mineral medium under an argon atmosphere. A 10% inoculum obtained from a stock culture grown on phenol was used for each tube. Aromatic compounds were added at a concentration of 0.5 or 1 mM from anaerobic stock solutions or, in the case of benzene and toluene, from neat solvents. Anaerobic growth on toluene vapor was assessed by incubating plates containing nitrate (20 mM) but no carbon source in the presence of the vapor from a 2% (vol/vol) solution of toluene in hexadecane under a hydrogen atmosphere. The plates were incubated for 1 to 2 weeks. The toluene-degrading denitrifying strain T1 (9) was used as a positive control. Anaerobic growth on toluene (of strain PH002 only) was also assessed by using the organic carriers mineral oil and 2,2,4,4,6,8,8-heptamethylnonane (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) (28). Aerobic growth on different substrates was determined in 50-ml flasks containing 10 ml of mineral medium and a 10% (vol/vol) inoculum. Cultures were incubated in a 30°C shaker incubator at 200 rpm for 1 to 3 days. Bacterial growth was monitored by visual inspection.

Nitrogen fixation.

Nitrogen fixation was determined by the acetylene reduction method (12). Serum bottles containing 60 ml of medium lacking NH4Cl or NO3−, solidified with 0.175% agar to establish microaerophilic conditions, and containing 5 mM succinate were inoculated, closed with sterile foam plugs, and incubated at 30°C for 2 to 5 days. Before acetylene was added, the headspace was flushed with argon, and the bottles were closed with rubber stoppers. Conversion of acetylene to ethylene was determined by gas chromatography after 24 h of incubation. Azospirillum brasilense was used as a positive control.

Phenol degradation. (i) Stoichiometry.

The optical densities, phenol concentrations, nitrate and nitrite concentrations, and headspace volumes and compositions of eight cultures growing on 1 mM phenol were measured over time. Gas production (in millimoles) was calculated by using Henry’s law. The concentration of dissolved CO2 ([H2CO3]) was then calculated by using the following equation: [H2CO3] = KH · PCO2, where the Henry’s law constant for the solubility of CO2 in water (KH) was 3.02 × 10−2 mol · liter−1 · atm−1 at 30°C (10). Background values for all parameters were measured by using sterile controls (autoclaved on 3 consecutive days), as well as by using substrate-free cultures, and were subtracted from the data obtained for the active cultures. At the end of the experiment, the dissolved CO2 was released by acidification of the culture medium to pH 2 by adding 1 ml of 50% H2SO4 and was measured with a gas chromatograph (model 1200; Fisher Scientific) to check the accuracy of the calculated dissolved CO2 concentrations. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and dried overnight at 80°C in tared aluminum dishes to determine the dry weight of the biomass produced. Dry weights were determined for separate, nonacidified cultures as well in order to prevent loss of biomass caused by cell lysis at pH 2.

(ii) Phenol metabolism.

Cultures were grown to the exponential phase in 3-liter volumes under an argon atmosphere with phenol or 4-hydroxybenzoate as the sole carbon source. Log-phase cultures were transferred into argon-flushed 250-ml centrifuge bottles on ice by pressurization with argon gas. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each culture was determined, and the culture was sparged with argon for a few minutes. Each bottle was closed with a lid containing an inner lid with a rubber O-ring (Nalgene, Rochester, N.Y.). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and were resuspended in 20 ml of mineral medium with or without 10 mM bicarbonate in an anaerobic chamber (Coy, Grass Lake, Mich.). Bicarbonate-free medium was sparged with nitrogen gas for 20 min to remove the dissolved CO2. Each suspension was washed three times in a 30-ml centrifuge tube containing an inner lid with a rubber O-ring (Nalgene). The tubes were opened only in the anaerobic chamber and were kept on ice at all times. Washed cells were resuspended to an OD600 of at least 3. The suspensions were transferred to glass screw-cap tubes, and substrates were added from sterile, anaerobic stock solutions to a final concentration of approximately 1 mM. The first sample (time zero) was taken immediately after substrate addition. The tubes were placed in a 30°C water bath, and samples (0.2 ml) were taken periodically with argon-flushed syringes. The samples were quickly pelleted in a microcentrifuge, after which the supernatant was diluted with 0.05 N HCl (1:4) and stored at 4°C before HPLC analysis. The factor for conversion of OD600 values to total protein values (in milligrams per milliliter) was determined to be 0.09. For this determination, cells were lysed by boiling them in 0.1 N NaOH for 10 min. The concentrations of total protein in the lysates were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) by using bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co.) as the standard.

Taxonomic identification of strains. (i) Standard microbial identification tests.

The microbial identification tests API Rapid NFT (BioMerieux S. A., Marcy l’Etoile, France) and BIOLOG (Biolog Inc., Hayward, Calif.) were used for preliminary identification of the isolates after they were grown for 96 h on TSA (Difco). Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1c was used as the control organism.

(ii) FAME analysis.

The isolates did not grow under the conditions suggested for FAME analysis (MIDI Inc., Newark, Del.). They grew more readily in liquid medium than on plates. Therefore, a defined mineral medium which also supports growth of Azoarcus and Thauera species (36) was used to compare the fatty acid profiles of the phenol-degrading isolates to the fatty acid profiles of T. aromatica K172 and A. tolulyticus Tol4 (11, 39). The cultures (100 ml) were grown for exactly 24 h at 30°C on 20 mM succinate and 50 mM nitrate and centrifuged (15 min, 10,000 × g), and the cellular fatty acids were saponified, methylated, and extracted by using the protocol of the Sherlock microbial identification system (MIDI Inc.). FAME were analyzed by gas chromatography. Phylogenetic relationships based on FAME profiles were determined by using the MIDI-SHERLOCK software. This software uses the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages to construct dendrograms (25).

(iii)16S rRNA gene isolation, sequencing, and analysis.

Total genomic DNAs were prepared from the phenol-degrading strains by the method of Olsen et al. (27) by using log-phase cells grown aerobically on 20 mM succinate. A portion of each DNA (ca. 100 ng) was used in the PCR to amplify the 16S rRNA gene with primers that span the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene from position 8 to position 27 in the forward direction (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′) and from position 1541 to position 1522 in the reverse direction (5′-AAG GAG GTG ATC CAI CCG CA-3′) (14). The resulting PCR products were purified with QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The nucleotide sequences of the products were determined by automated fluorescent dye terminator sequencing with a model ABI 373A sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The forward sequencing primers spanned positions 8 to 27, 339 to 357, 685 to 704, 907 to 926, and 1226 to 1242. The reverse primers spanned positions 321 to 340, 685 to 706, 907 to 926, and 1522 to 1541. Related sequences were obtained from the GenBank database (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine) by using the BLAST search program. The sequences were aligned, and phylogenetic trees were constructed with the PILEUP program (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) by using the neighbor-joining method and the Jukes-Cantor distance correction method. Only the 1,343 bases that were available for all related sequences were used.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rDNA sequences of the three phenol-degrading strains have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF011328 (CR23), AF011329 (PH002), and AF011330 (FL05). The accession numbers of other sequences used to determine levels of 16S rDNA similarity are as follows: T. aromatica K172, X77118; T. selenatis, X68491; A. indigens VB32, L15531; Azoarcus sp. strain S5b2, L15532; A. evansii KB740, X77679; A. tolulyticus Tol4, L33694; A. tolulyticus Td2, L33691; A. tolulyticus Td3, L33693; A. tolulyticus Td19, L33690; strain EbN1, X83531; strain PbN1, X83532; strain mXyN1, X83533; strain ToN1, X83534; Rhodocyclus purpureus, M34132; Zooglea ramigera, X74913; Neisseria denitrificans, X06173; and Pseudomonas pickettii, L37367.

RESULTS

Characterization of phenol-degrading denitrifying isolates.

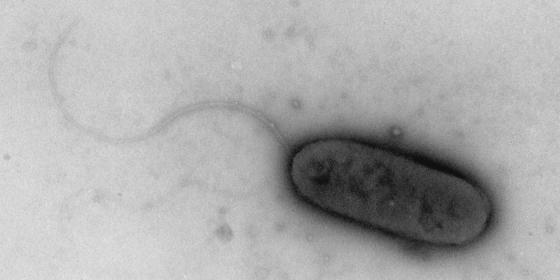

Phenol-degrading denitrifying enrichment cultures were readily established with all three sediments. These sediments originated from a polluted environment, the East River in New York, N.Y., from a commercial orange grove in Florida, and from a pristine environment in the Costa Rican rain forest. Initially, 10 strains were isolated from the Costa Rican sediment, and three strains were isolated from the Florida sediment. Because all of the characteristics studied were found to be identical for the isolates from each sediment, only one representative isolate from each source (strains CR23 and FL05 from Costa Rica and Florida, respectively) is discussed below. The three bacterial strains are all able to use phenol as a sole source of carbon and energy under denitrifying conditions. As the characteristics listed in Table 1 show, strain PH002 is quite similar to strain CR23, while strain FL05 can be distinguished from the other isolates by a number of characteristics. For example, strain FL05 does not flocculate upon depletion of its carbon source, does not produce PHB inclusion bodies, and is more sensitive to phenol than the other isolates, initiating growth only at phenol concentrations below 1.5 mM. Nitrogen fixation by the acetylene reduction method could be detected in PH002 and FL05 but not in CR23. Strain CR23 did, however, develop a thin subsurface pellicle in semisolid nitrogen-free medium, which suggests that it may indeed be able to fix nitrogen. All of the isolates are short to very short gram-negative rods, approximately 1 by 2 μm. During the exponential phase only, the cells are motile by means of one polar flagellum, as shown in Fig. 1; motility is lost in older cultures. None of the phenol-degrading isolates grows well on rich media. Growth on TSA is slow, resulting in pinpoint colonies after 48 h or more. Under such conditions the isolates may form short chains consisting of four to six cells. The strains are respiratory denitrifiers, and the products of nitrate reduction, nitrite, nitrous oxide, and dinitrogen, are all detected during growth under denitrifying conditions.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of phenol-degrading denitrifying isolates

| Strain | Origin | Morphology | Gram stain | PHB accumulation | Motility | Flocculationa | Optimum pH | Phenol tolerance (mM) | Generation time (h)b | N2 fixationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH002 | East River, New York, N.Y. | Rod | − | + | + | + | 6.7–6.9 | 3.5 | 9 | + |

| CR23 | Rain forest, Costa Rica | Rod | − | + | + | + | 6.9–7.7 | 3.5 | 9 | − |

| FL05 | Orange grove, Florida | Rod (curved) | − | − | + | − | 7.1–7.3 | 1.5 | 8.2 | + |

Flocculation when the carbon source is depleted in stationary, denitrifying cultures.

As determined during growth on 1 mM phenol at the optimum pH.

Ability to reduce acetylene to ethene.

FIG. 1.

Phenol-degrading denitrifying strain PH002. Electron micrograph of a polarly flagellated cell of strain PH002 in the exponential growth phase.

Metabolic versatility.

The phenol-degrading isolates were tested for their ability to mineralize or transform a large variety of simple aromatic compounds under aerobic and denitrifying conditions, and the results are summarized in Table 2. Consistent with our other observations, strains PH002 and CR23 differ only in the ability to use a few selected substrates (e.g., the aromatic acids hydrocinnamate and 2-aminobenzoate). Strain FL05, however, differs from the other two organisms with respect to the use of a number of aromatic compounds. It can, for instance, mineralize p-cresol in the presence of oxygen, whereas PH002 and CR23 only transform p-cresol to 4-hydroxybenzoate under aerobic conditions. Also, FL05 is able to anaerobically degrade protocatechuate. It is interesting that all three isolates could degrade phenol only under denitrifying conditions.

TABLE 2.

Metabolic versatility of the isolates under aerobic and denitrifying conditions

| Substratea | Utilization byb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain PH002

|

Strain CR23

|

Strain FL05

|

||||

| O2 | NO3− | O2 | NO3− | O2 | NO3− | |

| Phenol | −c | + | − | + | − | + |

| p-Cresol | −d | + | −d | + | + | + |

| 4-OH benzylalcohol | −d | + | −d | + | + | + |

| 4-OH benzylaldehyde | −d | + | −d | + | + | + |

| 4-OH benzoate | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| Protocatechuate | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Benzoate | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Benzylalcohol | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Benzylaldehyde | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Phenylacetate | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4-OH phenylacetate | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Cinnamic acid | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Hydrocinnamic acid | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Phenylalanine | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Tyrosine | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| 2-Aminobenzoate | + | ND | − | ND | − | ND |

All compounds were tested at a concentration of 1 mM.

O2 and NO3− were used as the electron acceptors in this study.

−, no visible growth; +, visible growth and disappearance of characteristic UV absorbance at wavelengths between 200 and 300 nm; ND, not determined.

Transformed to 4-OH benzoate.

The compounds not used or transformed by any of the strains include toluene, benzene, o-cresol, m-cresol, guaiacol, resorcinol, hydroquinone, catechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, syringic acid, mandelic acid, ferulic acid, phthalate, tryptophan, 2-aminophenol, 4-aminophenol, 4-aminobenzoate, and 4-nitrophenol. In addition, strain PH002 could not metabolize the intermediates of a hypothetical ring reduction mechanism (cyclohexanol, 2-cyclohexen-1-one, and 2-cyclohexen-1-ol) or any isomer of monochlorophenol and monochlorobenzoate. The other strains were not tested with these substrates. The nonaromatic substrates used by all three strains for anaerobic growth include glucose, succinate, ethanol, and pyruvate.

Stoichiometry.

The phenol-degrading strains convert a considerable portion of substrate carbon to biomass. For example, using the formula C5H7O2N (24) to describe the elemental composition of bacterial cells, we typically obtained a yield of 0.5 mol of cells per mol of phenol based on dry cell weights of strain PH002. Based on this level of conversion of phenol to biomass, the following stoichiometric equation is proposed: C6H6O + 0.5 NH3 + 3.6 NO3− + 3.6 H+ → 3.5 CO2 + 0.5 C5H7O2N + 1.8 N2 + 3.8 H2O. Based on the above equation, 75% of the expected amount of N2 was detected. Of the available carbon, 44% was assimilated into biomass (data not shown). However, only 30% of the expected amount of CO2 was detected due to analytical difficulties connected with the detection of CO2. Based on the above equation, the oxidation of 1 mol of phenol yields 18 mol of electrons. In our experiments, the reduction of NO3− to N2 accounted for 73% of the electrons generated from phenol oxidation, thus confirming that denitrification occurred. Reduction of NO3− to NO2− (25%) and reduction of NO2− to N2O (2%) accounted for the remaining electrons. Hence, the electron recovery was balanced (difference, 2.3%).

Phenol metabolism.

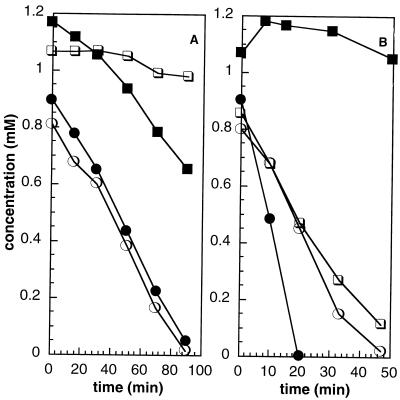

The anaerobic metabolism of phenol by all three strains was found to depend on the presence of (dissolved) CO2 in the medium. Cultures inoculated into bicarbonate-free medium with phenol as the only carbon source had considerably longer lag times than cultures inoculated into medium containing 10 mM HCO3− (data not shown). In addition, studies performed with dense cell suspensions of phenol-grown cells showed that phenol was degraded only if bicarbonate (10 mM) was present in the medium (Fig. 2A). The data in Fig. 2 were obtained with dense cell suspensions of strain PH002 (at a concentration of 0.324 mg of total protein per ml), and similar results were obtained with strains CR23 and FL05. Degradation of 4-hydroxybenzoate, the product of carboxylation (17, 18, 22, 36), was not affected by the presence of dissolved CO2. Furthermore, as Fig. 2B shows, dense cell suspensions of strain PH002 (at a concentration of 1.17 mg of total protein per ml) grown on 4-hydroxybenzoate did not metabolize phenol, whereas phenol-grown cells were simultaneously adapted to metabolize 4-hydroxybenzoate.

FIG. 2.

Anaerobic degradation of phenol by strain PH002. (A) Degradation of phenol (squares) and 4-hydroxybenzoate (circles) in the presence (solid symbols) or absence (open symbols) of 10 mM bicarbonate by dense suspensions of cells of strain PH002 grown on phenol. (B) Degradation of phenol (squares) and 4-hydroxybenzoate (circles) in medium containing 10 mM bicarbonate by dense suspensions of cells of strain PH002 grown on phenol (open symbols) or on 4-hydroxybenzoate (solid symbols).

Identification tests.

The phenol-degrading isolates could not be identified by the BIOLOG bacterial identification system. None of the carbon sources in the system was oxidized by the isolates even when the incubation period lasted more than 72 h. We also attempted to identify the isolates by using the API Rapid NFT microbial identification test; the apparent matches were anomalous.

FAME patterns.

Because the phenol-degrading isolates did not grow within 24 h on TSA, they could not be identified by using the MIDI database. Since these strains were more easily cultured in a defined liquid medium than on agar plates, 24-h-old liquid cultures grown anaerobically on 20 mM succinate were used for FAME analysis (Table 3). T. aromatica K172 (2) and A. tolulyticus Tol4 (31) were also included in the analysis. All of the organisms appeared to have similar membrane fatty acid compositions. Palmitoleic acid (abbreviated 16:1cis-7) and hexadecanoate (palmitic acid; 16:0) were the major components, comprising around 50 and 30% of the membrane, respectively. Fatty acids with a cyclopropane residue are thought to be produced when the stationary phase of growth is reached (37).

TABLE 3.

FAME profiles of phenol-degrading denitrifying isolates and Azoarcus and Thauera strains

| Strain | % of total fatty acids

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10:0a | 3-OH 10:0 | 12:0 | 14:0 | cis-7 16:1b | cis-5 16:1 | 16:0 | cyclo 17:0c | 18:1d | 18:0 | |

| PH002 | 0.4 | 3.8 | 6.3 | 0.8 | 52.7 | 0.5 | 28.6 | 0.27 | 6.2 | NDe |

| CR23 | 0.5 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 0.6 | 55.5 | 0.5 | 26.2 | 0.3 | 4.5 | ND |

| FL05 | 0.7 | 7.0 | 9.3 | 0.3 | 52.2 | 0.7 | 22.1 | ND | 7.5 | ND |

| Tol4f | 0.6 | 9.0 | 8.3 | 1.0 | 53.8 | 0.8 | 20.2 | 0.8 | 5.5 | ND |

| K172g | 0.4 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 45.4 | 0.9 | 24.7 | 1.5 | 15.8 | 0.2 |

Number of carbon atoms:number of unsaturated bonds.

Mixture of 16:1 cis-7/15:0 iso 2-OH and 15:0 iso 2-OH/16:1 cis-7; cis refers to the configuration of the double bond, and the position is relative to the aliphatic end of the carbon chain, and iso refers to a methyl group at the second-to-last carbon.

Cyclo indicates a cyclopropane structure at carbon atoms 7 and 8.

Mixture of 18:1 cis-7/trans-9/trans-12, 18:1 cis-9/trans-12/cis-7, and 18:1 trans-12/trans-9/cis-7.

ND, not detected.

A. tolulyticus Tol4 (= ATCC 51758). Data from B. K. Song.

T. aromatica K172 (= DSM 6984). Data from B. K. Song.

The FAME results in Table 3 were analyzed by using the MIDI-SHERLOCK software, and the results indicated that our phenol-degrading isolates are closely related to each other, as well as to A. tolulyticus Tol4. Our isolates and A. tolulyticus Tol4 were linked at Euclidian distances of less than 10 and might therefore be considered members of the same species (25). T. aromatica K172, however, is indeed part of a separate group, which is linked to the Azoarcus group at a Euclidian distance of 12 (data not shown).

16S rRNA sequence data.

The nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA genes of strains PH002, CR23, and FL05 were determined by automated fluorescence sequencing. Even though the isolates originated from diverse geographic locations and were found to differ in some physiological and metabolic characteristics (Tables 1 and 2), they appear to be very similar at the 16S rDNA level. In fact, the entire sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of strain CR23 was found to be identical to that of strain PH002. Strain FL05 differed from CR23 and PH002 at only 38 of 1,532 bases.

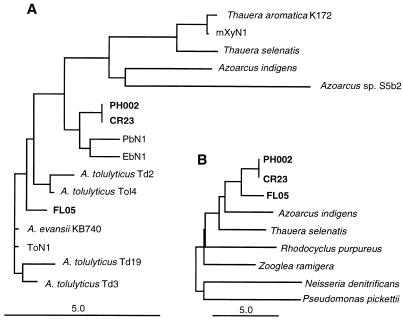

Phylogenetic analyses.

The GenBank database was used to search for 16S rRNA sequences homologous to the 16S rRNA sequences of the new isolates. The results of these searches showed that strains PH002, CR23, and FL05 cluster on the phylogenetic branch of the β subclass of the class Proteobacteria that comprises the genera Azoarcus and Thauera. Figure 3A illustrates the phylogenetic relationships of many of the organisms in the Azoarcus-Thauera group described so far. Included are the plant root-associated nitrogen-fixing organisms A. indigens and Azoarcus sp. strain S5b2 (29) and several strains of A. tolulyticus (39). Among all of the close relatives of our phenol-degrading strains included in Fig. 3A, phenol degradation has been reported only for PbN1, ToN1, and T. aromatica K172 (2, 28). The general position of the Azoarcus-Thauera group among the β subclass of the class Proteobacteria is illustrated in Fig. 3B. Additional characteristics of the new phenol-degrading isolates are compared to characteristics of other members of the Azoarcus-Thauera group in Table 4.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic trees based on 16S rDNA sequence analysis data. (A) Phenol-degrading denitrifiers PH002, CR23, and FL05 are affiliated with the genera Azoarcus and Thauera. (B) Positions of strains PH002, CR23, and FL05 within the β subclass of the class Proteobacteria. The bars represent 5 nucleotide substitutions per 100 nucleotides.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of phenol-degrading isolates to Azoarcus and Thauera speciesa

| Organism(s) | Denitrification | N2 fixation | PHB accumulation | Motility | Polar flagellum | Flocculation | Selenate reduction | Optimum pH | Growth on:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | Toluene | Benzoate | Glucose | Complex media | |||||||||

| Strain PH002 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 6.8 | + | − | + | + | − |

| Strain CR23 | + | −b | + | + | + | + | − | 6.9–7.7 | + | − | + | + | − |

| Strain FL05 | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | 7.2 | + | − | + | + | − |

| T. selenatis | + | − | + | + | + | + | 8 | +/−c | − | ||||

| T. aromatica K172 | + | + | +/−d | − | 7–7.4 | + | + | + | − | − | |||

| A. indigens and A. communis | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7 | − | − | − | − | +e | |

| A. tolulyticus | + | + | + | 6–9 | + | + | + | +f | |||||

| A. evansii | + | + | + | +g | − | 7.8 | − | − | + | ||||

DISCUSSION

Denitrifying microorganisms capable of using phenol as a sole source of carbon and energy were readily isolated from sediments from different geographic locations, including a pristine environment and environments exposed to xenobiotic compounds. This is not surprising given that phenolic compounds are present in most environments. It is interesting that the isolates from the three sources not only are closely related to each other but also are related to the only other denitrifying phenol-degrading bacterium that has been described in detail, T. aromatica K172 (2, 17, 18, 30, 36). The three strains, PH002, CR23, and FL05, are members of the genus Azoarcus, which was originally described because of the ability of its members to fix nitrogen (29). The diversity of geographic locations and environments in which Azoarcus species can be found was reflected in the first description of the genus. Azoarcus strains were isolated from the surfaces and interiors of roots of Kallar grass in Pakistan, from oily refinery sludge from France, and from human sources (wounds and blood) from Sweden (19, 29). Although initially it was reported that Azoarcus strains do not carry out nitrate reduction, denitrification by Azoarcus strains was reported later (13). The ability of bacteria to both fix atmospheric nitrogen and release it to the atmosphere as a result of respiratory nitrate reduction is not uncommon. Species known to be capable of both reactions include Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Azospirillum, Agrobacterium, Rhodopseudomonas, and Pseudomonas species. Respiratory denitrification provides ATP that can drive the energy-intensive process of nitrogen fixation (35). The species A. tolulyticus was proposed shortly after the description of the genus Azoarcus (39). Characteristics in which this new species differed from the original species, Azoarcus communis and A. indigens, included its ability to degrade toluene, its nonrhizosphere niche, several physiological, nutritional, and biochemical characteristics (Table 4), and some sequence dissimilarity in its 16S rDNA. A. tolulyticus strains are also able to fix nitrogen. As was the case for our phenol isolates, all A. tolulyticus strains could grow as a subsurface pellicle in nitrogen-free medium, although not all strains could be shown to reduce acetylene (11).

The FAME analysis technique for identification of microorganisms (including yeasts, actinomycetes, and fungi) (25) did not allow identification of our isolates since the database did not include data for Azoarcus strains, which is what they were subsequently determined to be. A modification of the method, however, yielded results that confirmed the affiliation of these organisms with the genus Azoarcus. By using a liquid growth medium which supports the growth of our phenol-degrading strains, as well as the Azoarcus and Thauera species, and by standardizing the growth conditions, we were able to directly compare the FAME profiles of these organisms to one another. The resolving power of FAME analysis proved to be sufficient to distinguish Azoarcus species from members of the closely related genus Thauera. It is not yet clear whether the resolving power is also sufficient to divide the Azoarcus groups into distinct and reproducible subgroups, although preliminary data indicates that A. tolulyticus Tol4 and strain FL05 may belong to a subgroup separate from some of the other A. tolulyticus strains and strains PH002 and CR23 (31).

It is interesting that despite the fact that the nucleotide sequences of the 16S rDNA of strains PH002 and CR23 were found to be identical, these organisms exhibited a few subtle differences. Because of its highly conserved nature, sequence comparison of the 16S rDNA of highly related species may not reflect the diversity that may exist among such species. The subtle, although significant, differences detected in this study emphasize the importance of polyphasic characterization of newly isolated bacteria.

There is now ample evidence that the first step in the anaerobic phenol degradation pathway is carboxylation in the para position to 4-hydroxybenzoate. Production of 4-hydroxybenzoate has been detected, by either direct or indirect methods, in methanogenic consortia (15, 21, 38), as well as in pure cultures of an iron-reducing organism (22) and the denitrifier T. aromatica K172 (17, 18, 36). Evidence suggests that our strains also carry out these reactions. Dense suspensions of phenol-grown cells were shown to utilize phenol only in the presence of bicarbonate. In addition, phenol-adapted cells also rapidly degraded 4-hydroxybenzoate, whereas 4-hydroxybenzoate-grown cells were not adapted to degrade phenol. Although 4-hydroxybenzoate was not detected in culture supernatants of our phenol-degrading cultures, this may be because phenol metabolism is thought to occur intracellularly, as indicated by results obtained in studies performed with cell extracts of T. aromatica (17, 18).

In summary, three new denitrifying microorganisms that belong to the genus Azoarcus and are capable of using phenol as a sole source of carbon and energy were isolated, identified, and characterized. In addition, other researchers have recently isolated Azoarcus species that are capable of growth on other monoaromatic compounds under denitrifying conditions (2, 28, 39). Hence, the genus Azoarcus, which originally contained only root-associated diazotrophs, may prove to be an important taxon containing denitrifying aromatic-degrading bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Defense Office of Naval Research and Advanced Research Projects Agency University Research Initiative Program (grant N00014-92-J-1888).

We thank G. Zylstra and A. Goyal for assistance with the 16S rRNA work, M. Häggblom and B. K. Song for advice and assistance with the FAME analysis, C. Neyra and A. Atkinson for help with the nitrogenase assays, and I. Dushenkov for assistance with the laboratory experiments. The original isolation of strain PH002 was done by O. O’Connor. Electron microscopy was performed by K. S. Kim at New York University Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler J. Chemotaxis in bacteria. Science. 1966;153:708–716. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3737.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders H-J, Kaetzke A, Kämpfer P, Ludwig W, Fuchs G. Taxonomic position of aromatic-degrading denitrifying pseudomonad strains K 172 and KB 740 and their description as new members of the genera Thauera, as Thauera aromatica sp. nov., and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus evansii sp. nov., respectively, members of the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:327–333. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-2-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bak F, Widdel F. Anaerobic degradation of phenol and phenol derivatives by Desulfobacterium phenolicum sp. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1986;146:177–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker G. Anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds in the presence of nitrate. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1977;1:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boopathy R. Isolation and characterization of a phenol-degrading, sulfate-reducing bacterium from swine manure. Bioresource Biotechnol. 1995;54:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdon K L. Fatty material in bacteria and fungi revealed by staining dried, fixed slide preparations. J Bacteriol. 1946;52:665–678. doi: 10.1128/jb.52.6.665-678.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean-Ross D. Bacterial abundance and activity in hazardous waste-contaminated soil. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1989;43:511–517. doi: 10.1007/BF01701928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean-Ross D, Rahimi M. Toxicity of phenolic compounds to sediment bacteria. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1995;55:245–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00203016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans P J, Mang D T, Kim K S, Young L Y. Degradation of toluene by a denitrifying bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1139–1145. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1139-1145.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faust S D, Osman M A. Chemistry of natural waters. Ann Arbor, Mich: Ann Arbor Science Publishers; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fries M R, Zhou J, Chee-Sanford J, Tiedje J M. Isolation, characterization, and distribution of denitrifying toluene degraders from a variety of habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2802–2810. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2802-2810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy R W F, Holsten R D, Jackson E K, Burns R C. The acetylene-ethylene assay for nitrogen fixation: laboratory and field evaluations. Plant Physiol. 1986;43:1185–1207. doi: 10.1104/pp.43.8.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurek T, Reinhold-Hurek B. Identification of grass-associated toluene-degrading diazotrophs, Azoarcus spp., by analysis of partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2257–2261. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2257-2261.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson J L. Similarity analysis of rRNAs. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 683–700. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knoll G, Winter J. Degradation of phenol via carboxylation to benzoate by a defined, obligately syntrophic consortium of anaerobic bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;30:318–324. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuever J, Kulmer J, Janssen S, Fischer U, Blotevogel K-H. Isolation and characterization of a new spore-forming sulfate-reducing bacterium growing by complete oxidation of catechol. Arch Microbiol. 1993;159:282–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00248485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lack A, Fuchs G. Carboxylation of phenylphosphate by phenol carboxylase, an enzyme system of anaerobic phenol metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3629–3636. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3629-3636.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lack A, Fuchs G. Evidence that phenol phosphorylation to phenylphosphate is the first step in anaerobic phenol metabolism in a denitrifying Pseudomonas sp. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:132–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00276473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laguerre G, Bossand B, Bardin R. Free-living dinitrogen-fixing bacteria isolated from petroleum refinery oily sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1674–1678. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.7.1674-1678.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law J H, Slepecky R A. Assay of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid. J Bacteriol. 1961;82:33–36. doi: 10.1128/jb.82.1.33-36.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Bisaillon J-G, Villemur R, Létourneau L, Bernard K, Lépine F, Beaudet R. Isolation and characterization of a new bacterium carboxylating phenol to benzoic acid under anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2551–2558. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2551-2558.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovley D R, Lonergan D J. Anaerobic degradation of toluene, phenol, and p-cresol by the dissimilatory iron-reducing organism GS-15. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1858–1864. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1858-1864.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macy J M, Rech S, Auling G, Dorsch M, Stackebrandt E, Sly L I. Thauera selenatis gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the beta subclass of Proteobacteria with a novel type of anaerobic respiration. Int J Syt Bacteriol. 1993;43:135–142. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-1-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarty P L, Beck L, St. Amant P. Proceedings of the 24th Industrial Waste Conference. Lafayette, Ind: Purdue University; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MIDI, Inc. Microbial Identification System library generation manual, version 1. Newark, Del: MIDI, Inc.; 1994. p. 4.4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor O A. Bacterial metabolism of aromatic compounds under anaerobic conditions. Ph. D. dissertation. New York, N.Y: New York University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen R H, DeBusscher G, McCombie W R. Development of broad-host-range vectors and gene banks: self-cloning of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:60–69. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.60-69.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabus R, Widdel F. Anaerobic degradation of ethylbenzene and other aromatic hydrocarbons by new denitrifying bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163:96–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00381782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinhold-Hurek B, Hurek T, Gillis M, Hoste B, Vancanneyt M, Kersters K, De Ley J. Azoarcus gen. nov., nitrogen-fixing proteobacteria associated with roots of Kallar grass (Leptochloa fusca (L.) Kunth), and description of two species, Azoarcus indigens and Azoarcus communis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:574–584. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schocher R J, Seyfried B, Vasquez F, Winter J. Anaerobic degradation of toluene by pure cultures of denitrifying bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1991;157:7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00245327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song, B. K., M. M. Häggblom, J. Zhou, J. M. Tiedje, and N. J. Palleroni. Unpublished data.

- 32.Sparling G P, Ord B G, Vaughan D. Changes in microbial biomass and activity in soils amended with phenolic acids. Soil Biol Biochem. 1981;13:455–460. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Störmer K. Ueber die Wirkung des Schwefelkohlenstoffs und ähnlicher Stoffe auf den Boden. Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg. 1908;20:282–286. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor B F, Campbell W F, Chinoy I. Anaerobic degradation of the benzene nucleus by facultatively anaerobic microorganisms. J Bacteriol. 1970;102:430–437. doi: 10.1128/jb.102.2.430-437.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiedje J M. Ecology of denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium. In: Zehnder A J B, editor. Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. New York, N.Y: Wiley & Sons, Inc., Publisher; 1988. pp. 179–244. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tschech A, Fuchs G. Anaerobic degradation of phenol by pure cultures of newly isolated denitrifying pseudomonads. Arch Microbiol. 1987;148:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00414814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang A-Y, Cronan J E., Jr The growth phase-dependent synthesis of cyclopropane fatty acids in Escherichia coli is the result of an RpoS (KatF)-dependent promoter plus enzyme instability. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1009–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Mandelco L, Wiegel J. Clostridium hydroxybenzoicum sp. nov., an amino acid-utilizing, hydroxybenzoate-decarboxylating bacterium isolated from methanogenic freshwater pond sediment. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:214–222. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-2-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou J, Fries M R, Chee-Sanford J C, Tiedje J M. Phylogenetic analyses of a new group of denitrifiers capable of anaerobic growth on toluene and description of Azoarcus tolulyticus sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:500–506. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-3-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]