Abstract

Background

The burden of asthma on patients and healthcare systems is substantial. Interventions have been developed to overcome difficulties in asthma management. These include chronic disease management programmes, which are more than simple patient education, encompassing a set of coherent interventions that centre on the patients' needs, encouraging the co‐ordination and integration of health services provided by a variety of healthcare professionals, and emphasising patient self‐management as well as patient education.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of chronic disease management programmes for adults with asthma.

Search methods

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register, MEDLINE (MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations), EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were searched up to June 2014. We also handsearched selected journals from 2000 to 2012 and scanned reference lists of relevant reviews.

Selection criteria

We included individual or cluster‐randomised controlled trials, non‐randomised controlled trials, and controlled before‐after studies comparing chronic disease management programmes with usual care in adults over 16 years of age with a diagnosis of asthma. The chronic disease management programmes had to satisfy at least the following five criteria: an organisational component targeting patients; an organisational component targeting healthcare professionals or the healthcare system, or both; patient education or self‐management support, or both; active involvement of two or more healthcare professionals in patient care; a minimum duration of three months.

Data collection and analysis

After an initial screen of the titles, two review authors working independently assessed the studies for eligibility and study quality; they also extracted the data. We contacted authors to obtain missing information and additional data, where necessary. We pooled results using the random‐effects model and reported the pooled mean or standardised mean differences (SMDs).

Main results

A total of 20 studies including 81,746 patients (median 129.5) were included in this review, with a follow‐up ranging from 3 to more than 12 months. Patients' mean age was 42.5 years, 60% were female, and their asthma was mostly rated as moderate to severe. Overall the studies were of moderate to low methodological quality, because of limitations in their design and the wide confidence intervals for certain results.

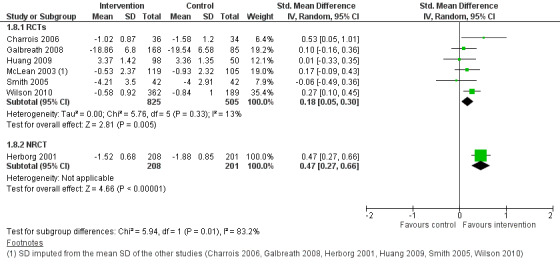

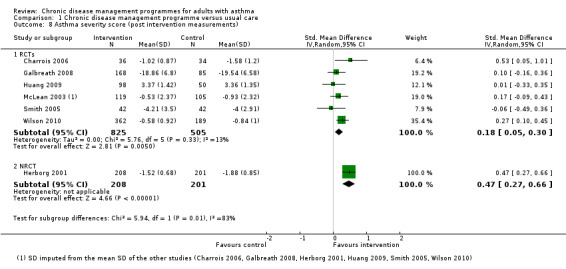

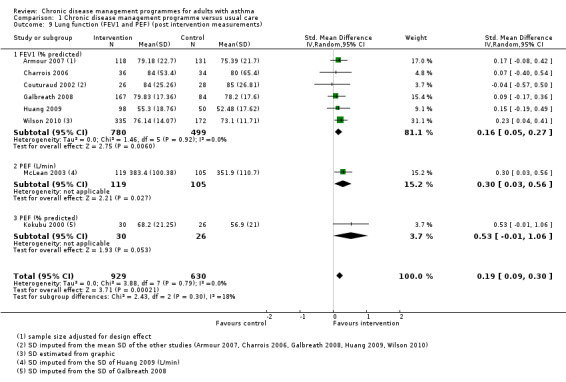

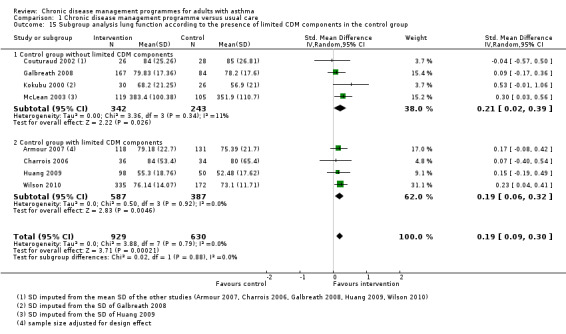

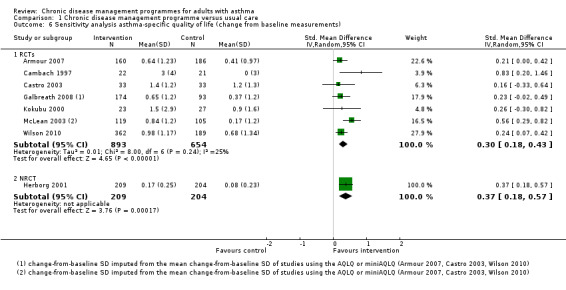

Compared with usual care, chronic disease management programmes resulted in improvements in asthma‐specific quality of life (SMD 0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.08 to 0.37), asthma severity scores (SMD 0.18, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.30), and lung function tests (SMD 0.19, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.30). The data for improvement in self‐efficacy scores were inconclusive (SMD 0.51, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 1.11). Results on hospitalisations and emergency department or unscheduled visits could not be combined in a meta‐analysis because the data were too heterogeneous; results from the individual studies were inconclusive overall. Only a few studies reported results on asthma exacerbations, days off work or school, use of an action plan, and patient satisfaction. Meta‐analyses could not be performed for these outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate to low quality evidence that chronic disease management programmes for adults with asthma can improve asthma‐specific quality of life, asthma severity, and lung function tests. Overall, these results provide encouraging evidence of the potential effectiveness of these programmes in adults with asthma when compared with usual care. However, the optimal composition of asthma chronic disease management programmes and their added value, compared with education or self‐management alone that is usually offered to patients with asthma, need further investigation.

Plain language summary

Chronic disease management for asthma

Asthma is a chronic (long‐term) airway (breathing) disease affecting about 300 million people worldwide. People with asthma have many symptoms, such as wheezing, coughing and shortness of breath. The aim of a chronic disease management programme for asthma is to improve the quality and effectiveness of asthma care by creating a programme that is centred on patient's needs, encourages the co‐ordination of the health services provided by healthcare professionals such as doctors and nurses, who should work together, and focuses on helping the patients to manage their illness themselves as well as providing them with information to help them understand their illness.

This review found 20 studies that compared the effects of chronic disease management programmes in adults with asthma with the effects of usual care. The average age of the patients was 42.5 years, 60% were women, and they had moderate to severe asthma. Overall the evidence that was found was of moderate to low quality.

Chronic disease management programmes for adults with asthma probably improve patients' quality of life, reduce the severity of the asthma, and improve breathing as demonstrated by improved performance in lung function tests after 12 months. It is unclear whether chronic disease management programmes improve the patients' abilities to manage their own asthma or decrease the number of hospitalisations or emergency visits.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Chronic disease management compared with usual care for adults with asthma.

| Chronic disease management compared with usual care for adults with asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with asthma Settings: 7 studies in primary care practices, 3 in outpatient hospital departments, 3 in pharmacies, 2 in health maintenance organisations (HMOs), 5 in mixed settings Intervention: chronic disease management Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Chronic disease management | |||||

| Asthma‐specific quality of life score Measured on different scales in different studies. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life. Follow‐up: 3 to 12 months | The mean asthma‐specific quality of life score ranged across control groups from 3.8 to 5.31 | The mean asthma‐specific quality of life score in the intervention groups was 0.22 standard deviations higher (0.08 to 0.37 higher) | 1627 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | A SMD of 0.22 represents a small improvement in quality of life. On the AQLQ scale, it represents a mean difference of 0.31 (0.11 to 0.53). MCID of AQLQ = 0.53,4 | |

| Number of hospitalisations per patient ‐ not reported | The mean number of hospitalisations per patient ranged across control groups from 0.06 to 1.23 | The mean number of hospitalisations per patient ranged across intervention groups from 0.02 to 0.4 | Not estimable | ‐ | Not assessed;see comment | Data too heterogeneous to perform meta‐analysis |

| Number of emergency room or unscheduled visits ‐ not reported | The mean number of emergency room or unscheduled visits per patient ranged across control groups from 0.02 to 1.4 | The mean number of emergency room or unscheduled visits per patient ranged across intervention groups from 0.02 to 1.9 | Not estimable | ‐ | Not assessed; see comment | Data too heterogeneous to perform meta‐analysis |

| Asthma exacerbations ‐ not measured | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not estimable | ‐ | Not assessed;see comment | No data available for meta‐analysis |

| Self‐efficacy score5 Measured on different scales in different studies. Higher scores indicate higher self‐efficacy Follow‐up: 3 to 12 months | 5 | The mean self‐efficacy score in the intervention groups was 0.51 standard deviations higher (0.08 lower to 1.11 higher) | 642 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6,7 | A SMD of 0.51 represents a moderate improvement in self‐efficacy3,8 | |

| Asthma severity score5 Measured on different scales in different studies. Higher scores indicate lower severity Follow‐up: 6‐12 months | The mean asthma severity score in the intervention groups was 0.18 standard deviations higher (0.05 to 0.3 higher) | 1330 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6,9 | A SMD of 0.18 represents a small improvement in asthma severity<BR/>3,8 | ||

| Days off work ‐ not measured | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not estimable | ‐ | Not assessed;see comment | No data available for meta‐analysis |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Values correspond to the AQLQ scores only 2 Downgraded because majority of studies were at high or unclear risk of bias 3 As a rule of thumb: SMD < 0.40 = small effect, SMD 0.40 to 0.70 = moderate effect, SMD > 0.70 = large effect 4 The score was estimated using a SD of 1.43 (control group of Gallbreath's study) 5 No assumed risk presented for usual groups because too much variation in the instruments or scales used 6 Downgraded because of clinical, statistical and measurement heterogeneity 7 Wide 95% CIs 8 Back‐transformation was not performed because all studies used another instrument or scale 9 Downgraded because three studies were at high risk of bias

Background

Description of the condition

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways, affecting an estimated 300 million people worldwide (GINA 2012). The prevalence of asthma in adults is up to 10% in developed countries, and is currently rising (Asher 2006; Braman 2006; Masoli 2004). Despite being a common chronic disease, it does not rank among the 15 first projected causes of mortality or disability‐adjusted life years (Mathers 2006). Nevertheless, asthma places a substantial burden on affected people and healthcare systems, with morbidity, mortality, and economic burdens that have been increasing during the last 40 years (Braman 2006).

In order to achieve effective asthma control, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has been providing, since 2002, an evidence‐based global strategy for asthma management and prevention (GINA 2012). However, despite the existence of effective therapies and the development of evidence‐based guidelines, there are still significant practice variations and gaps between recommended care and current practice (Klomp 2008; Vermeire 2002). Asthma could be controlled, but its management remains suboptimal (Leuppi 2006; Vermeire 2002).

The difficulties in asthma management are multiple, including poor implementation of treatment guidelines, suboptimal patient education and self‐management, poor patient adherence to treatment and lifestyle modifications, neglect of preventive care, and lack of co‐ordination between healthcare providers, among others (Latry 2008; Mäkinen 1999; Pacheco 1999; Vermeire 2002). A variety of individual interventions have been used to address these issues and systematically assessed. For instance, a Cochrane review showed that self‐management programmes in adult asthmatics reduced healthcare utilisation, the number of days off work or school, nocturnal asthma, and improved quality of life (Gibson 2003). In contrast, limited patient education (information only) did not (Gibson 2002). Similarly, two other systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of written asthma action plans did not find evidence of benefit (Powell 2003; Toelle 2004). Nevertheless, given that the included studies were small and of low power, experts still recommend the use of written action plans (GINA 2012; NAEPP 2007). Finally, provider level interventions such as continuing medical education, reminder systems, or audit with feedback yielded inconsistent results across chronic diseases (Davis 1995; Davis 1999; Weingarten 2002). The combination of all these types of interventions is proposed in chronic disease management programmes.

Description of the intervention

Chronic disease management (CDM) was developed during the 1990s as a means of reorganising healthcare systems and medical treatment for chronic diseases such as heart failure, diabetes, depression, and chronic lung diseases. Its purpose is to enhance the quality and cost‐effectiveness of care for chronic diseases. CDM is centred on patients' needs, fosters the co‐ordination and integration of health services provided by various professionals who should work together (multidisciplinary care), and emphasizes patients’ self‐management as well as education and empowerment. CDM is also based on formal evidence of effectiveness and promotes continuous improvement processes through quality control (DMAA Definitions 2009; Ellrodt 1997; Epstein 1996; Faxon 2004; Hunter 1997; Kesteloot 1999; Pilnick 2001; Weingarten 2002).

Several definitions of CDM, which differ by the number and variety of elements that they integrate, have been published (DMAA Definitions 2009; Ellrodt 1997; Epstein 1996; Faxon 2004; Hunter 1997; Kesteloot 1999; Pilnick 2001; Weingarten 2002). In addition, the American Heart Association’s Disease Management Taxonomy Writing Group developed a system of classification intended to help categorise and compare disease management programmes (Krumholz 2006). Recently, to facilitate the understanding and communication about the concept of CDM, Schrijvers 2009 proposed a tentative definition of chronic disease management based on the elements found in the literature: "[CDM] consists of a group of coherent interventions designed to prevent or manage one or more chronic conditions using a systematic multidisciplinary approach potentially employing multiple treatment modalities. The goal of chronic disease management is to identify persons at risk for one or more chronic conditions, to promote self‐management by patients and to address the illness or conditions with maximum clinical outcome, effectiveness and efficiency regardless of treatment setting(s) or typical reimbursement patterns” (Schrijvers 2009). Because CDM programmes are adapted to the regional healthcare, social, and political contexts, they vary in terms of treatment modalities, frequency, intensity, and duration. Nevertheless, several systematic reviews have shown that CDM programmes are effective, at least for some outcomes and some chronic diseases such as diabetes (Egginton 2012; Elissen 2013; Knight 2005; Norris 2002; Pimouguet 2011), depression (Badamgarav 2003; Neumeyer‐Gromen 2004), chronic heart failure (Gohler 2006; Gonseth 2004; McAlister 2001; Roccaforte 2005), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Adams 2007; Kruis 2013; Lemmens 2013; Niesink 2007; Peytremann‐Bridevaux 2008), or across chronic conditions (de Bruin 2011; Ofman 2004; Ouwens 2005; Tsai 2005). As such, they are supported by an increasing number of healthcare systems (Busse 2004; Gogovor 2008; Montague 2007; Steuten 2007; Stock 2006) and have been implemented throughout Northern American and European countries during the past decade (NCSL DMP descriptions).

Why it is important to do this review

Asthma presents all characteristics described as mandatory for CDM suitability (Mechanic 2002; Velasco‐Garrido 2003). Indeed, asthma CDM programmes have yielded positive results in some studies and are considered a promising way to improve asthma management and reduce costs (Blaiss 2005; Durbin 1997; Steuten 2007a). Still, the effectiveness of CDM for adults with asthma has yet to be systematically and comprehensively assessed. One systematic review evaluating CDM programmes for patients with asthma found that these programmes reduced resource utilisation and improved some aspects of self‐management and organisation of care, but had almost no impact on asthma symptoms and lung function (Steuten 2007a). However, it only included studies published between December 2005 and December 2006 and considered both adults and children with asthma. The authors also showed that while process and outcome measures were more appropriately chosen than before, structure indicators were lacking. Two other systematic reviews published in 2009 (Lemmens 2009; Maciejewski 2009) provided further information. The Lemmens 2009 review showed that CDM programmes targeting adults with asthma or COPD improved quality of life and decreased the risk of hospitalisation, especially when the interventions included three components, but did not have any effect on emergency visits. The authors of the other review on CDM programmes, targeting only adults with asthma, decided not to conduct meta‐analyses because of heterogeneity and missing information; they concluded that the quality of studies was not optimal and that it was not possible to decide whether CDM would or would not be beneficial to patients with asthma (Maciejewski 2009).

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess the effectiveness of chronic disease management programmes for adults with asthma.

Secondary objectives

To assess the effectiveness of chronic disease management programmes for adults with asthma according to the intensity of the intervention (e.g., more intensive versus minimal interventions, in terms of number of intervention components and types of components, such as mainly centred on the patient versus on healthcare professionals).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised controlled trials (NRCTs), controlled before‐after studies (CBAs), and interrupted time series studies (ITSs), allocating patients or clusters. According to the guidance from the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Review group (EPOC 2013), CBA studies were eligible only if the pre‐ and post‐intervention periods for the study and control sites were the same; if the study and control sites were comparable with respect to the dominant reimbursement system, level of care, setting of care, and academic status; and if there were a minimum of two interventions and two control sites. ITS studies were eligible only if there was a clear, time‐defined beginning of the intervention and if there was a minimum of three measurement points available before and after the intervention.

The rationale for including study types other than RCTs was that it can be difficult to implement RCTs assessing complex disease management programmes. Additionally, this is a relatively new research area with few RCTs.

Types of participants

We included adult participants (over 16 years of age) with a diagnosis of asthma. We excluded studies in which patients with other significant pulmonary chronic disease (like moderate or severe COPD or bronchiectasis) represented a significant proportion of participants, unless subgroup analysis was available. In the same way, trials including both adults and children were included only if the majority of participants were over 16 years or if the adult subgroup was analysed independently.

Types of interventions

Based on several definitions of disease management (DMAA Definitions 2009; Ellrodt 1997; Epstein 1996; Faxon 2004; Hunter 1997; Kesteloot 1999; Pilnick 2001; Weingarten 2002), we considered the following five criteria for our operational definition of CDM:

at least one organisational component (i.e., elements that interfere with the care process or that aim to improve continuity of care) targeting patients (Steuten 2007a; Weingarten 2002);

at least one organisational component targeting healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, etc.), the healthcare system, or both;

presence of a patient education or self‐management support component, or both;

active involvement of two or more healthcare professionals in patient care; and

minimum duration of three months (or 12 weeks) for at least one component.

Therefore, we only included CDM programmes that entirely met the above operational definition of chronic disease management (that is, all five criteria are compulsory). Below are listed the types of components that are usually proposed in CDM programmes, adapted to asthma patients. They directly relate to the above‐mentioned five criteria.

1. At least one organisational component targeting patients (each of the following was considered as an independent component):

case management (defined as explicit allocation of co‐ordination tasks to a case manager or a small team who takes responsibility for guiding the patient through the care process in the most efficient, effective, and acceptable way);

structured follow‐up (e.g., telephone calls, regular clinic visits, etc.) or encouragement for regular follow‐up;

home or outreach visits;

discharge planning in the case of hospitalisation;

advice or assistance, or both, if needed (e.g., a telephone hotline);

smoking cessation programmes recommended or proposed, or both; and

other (other components deemed compatible by all the review authors).

2. At least one organisational component targeting primarily healthcare professionals (for example physicians, nurses, etc.) or the healthcare system, or both, such as:

explicit teamwork and collaborative processes between healthcare providers;

physicians’ education and training (any format) or other healthcare professionals’ education and training, or both;

other quality improvement processes (e.g., reminder systems, clinical pathways, routine reporting, feedback loops, etc.);

integration of care (i.e., continuity of care between primary, secondary, and tertiary care);

financial incentives;

information technology (e.g., computerised medical records, reminders or prompts, etc.);

explicit use of evidence‐based medicine supports (e.g., use of evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines, etc.);

process and outcome measurements (at the patient level);

evaluation of CDM programmes (at the group level); and

other (other components deemed compatible by all the reviews authors).

3. Presence of a patient education or self‐management support component, or both. Patient education was defined as giving the patients information (materials, instructions, or both) regarding:

asthma;

management of the disease, its exacerbations, or both;

prevention of exacerbations (trigger recognition and reduction strategies);

smoking cessation;

exercise or physical activity.

The types of educational sessions included, for example:

distribution of published or printed material;

educational groups or meetings;

one‐on‐one educational sessions during visits (physician, nurses, etc.).

Self‐management support was defined as helping patients acquire the skills and knowledge to manage their own illnesses, providing self‐management tools, and routinely assessing their problems and accomplishments (Ouwens 2005). The types of self‐management support included, for example:

the availability of an action plan;

so‐called supervised reinforcement sessions;

regular checks of inhalation technique.

4. Two or more healthcare professionals actively involved in the patient care, such as:

general or family practitioners (GPs), primary care physicians, and general internists;

pulmonary care physicians;

respiratory care nurses (nurses with training in asthma management);

non‐specialised nurses;

physiotherapists;

pharmacists; and

other healthcare professionals (for example social workers).

5. Minimal duration of three months (12 weeks) for at least one component.

CDM programmes targeting chronic diseases require long lasting interventions, and should not be merely considered as another treatment modality but rather as a new way to organise care implemented from a long‐term perspective. Therefore, they needed to have at least one component from criteria one to three that lasted three months or more (arbitrary cut‐off point).

We compared CDM to standard care (varying from usual care to usual care including limited CDM components).

Types of outcome measures

Throughout the text, we use the term outcome in its broad sense to refer to the notion of dependent variable. Under that term, we considered clinically relevant effect measures (such as patient outcomes), process of care and intermediate measures, as well as structure indicators. These were based and adapted from a consensus of clinically relevant outcomes of an asthma patient management model (Clark 1994). Indicators relating to the implementation of CDM programmes, per se, were not considered. We divided our outcomes into two main groups: organisational and patient level outcomes. The list of possible outcomes, as well as the 10 outcomes selected as primary outcomes (specified in brackets) that were considered in the analyses, are shown below. We included 7 of these 10 primary outcomes in the Table 1, based on their clinical importance: quality of life, hospitalisation, emergency or unscheduled visits, asthma exacerbations, self‐efficacy, asthma severity, and days off school or work absences.

Organisational level outcomes

Organisation of care outcomes: participation rate for CDM programme; healthcare professionals’ satisfaction with programme.

Process outcomes: use of an action plan (primary); compliance with treatment schedule; prescription of inhaled corticosteroids; check of appropriate inhalation techniques; and smoking cessation advice or support, or both.

Healthcare utilisation outcomes: asthma‐related or all‐cause hospitalisation, or both, defined as any inpatient hospital stay (primary); asthma‐related or all‐cause unscheduled visits, or both, defined as urgent visits to hospital emergency departments (ED) or unscheduled physicians visits (primary); GP visits, defined as routine (scheduled) ambulatory care visits to a GP or family physician; and healthcare costs (direct and indirect, if available).

Patient level outcomes

Quality of life: an asthma‐specific quality of life instrument (primary) such as the St‐George Respiratory Questionnaire (Jones 1991), Living with Asthma Questionnaire (LWAQ) (Hyland 1991), Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) (Juniper 1992); a generic quality of life instrument such as the Short Form 36 (SF‐36) (Ware 1992), SF‐12 (Ware 1996), EQ‐5D (EuroQol Group 1990), or self reported subjective health.

Symptoms and activity level: asthma exacerbations (defined as prompting hospitalisation, ED visit, unscheduled medical visit, or rescue systemic glucocorticoids) (primary); asthma severity and symptoms (primary) (subjective measures that include asthma symptoms or severity scores, or both) (e.g., the Asthma Control Test (Nathan 2004), the Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) (Vollmer 1999)); days off school or work absences (due to asthma or other causes, or both) (primary); nights disturbed by asthma (sleep interruptions due to asthma or nights with asthma symptoms); days of restricted activity; use of rescue ß2‐agonists; and all‐cause mortality.

Self‐management: patients' asthma knowledge score; trigger recognition and reduction strategies; measures of self‐efficacy and self‐management (primary).

Pulmonary function tests: forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); peak expiratory flow rate (PEF); a combined measure of lung function, defined as either FEV1 or PEF (primary).

Patient satisfaction with care: measures of patient satisfaction (or experiences) with care (primary).

To define the timing of outcomes measurements, we grouped time points in three arbitrary intervals to represent short‐term, medium‐term, and long‐term outcomes (from 0 to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, and over 12 months).

Studies were excluded if none of the primary outcomes were reported.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

M Fiander, Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) for the EPOC review group, developed search strategies in consultation with the authors. The TSC searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for related systematic reviews and the databases listed below for primary studies. Searches were conducted to June 2014; exact search dates for each database are included in the search strategies in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), OvidSP.

Cochrane EPOC Group Specialised Register (to 2012).

MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations (1946 on), OvidSP.

EMBASE (1947 on), OvidSP.

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (1980 to 2012) , EBSCOhost.

PsycINFO (1806 on), OvidSP.

Search strategies were comprised of keywords, when available, and controlled vocabulary such as MeSH (Medical Subject Headings). Two methodological search filters were used to limit retrieval to appropriate study designs: the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy (sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version, 2008 revision) (Higgins 2011) to identify RCTs, and an EPOC methodology filter to identify non‐RCT designs. Language restrictions were not applied.

Searching other resources

We conducted handsearches of selected journals from 2000 to 2012. We also performed handsearching of reference lists of retrieved papers and relevant narrative or systematic reviews. To identify new and ongoing trials, we searched www.clinicaltrials.org and www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used a three‐step study screening procedure. First, based on titles only, one review author (CA, GG or IPB) excluded obviously non‐pertinent references. These excluded references were double‐checked by a second review author (CA, GG or IPB) to approve the exclusions. Then, based on abstracts, two review authors (CA, GG, POB or IPB) independently, and in duplicate, excluded previously retained articles if they represented a non‐original study, were obviously not focused on asthma, were obviously not on chronic disease management, or were clearly on another topic. Finally, articles deemed potentially relevant by any review author had their full texts assessed for eligibility by two review authors (CA, GG, POB or IPB). Reasons for excluding studies based on the full‐text assessment are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Any disagreement about eligibility was resolved by discussion between the review authors and with the involvement of an arbitrator as necessary. Multiple published articles from a single study were treated as a single intervention evaluation. Because chronic disease management programmes were developed and first described in the early 1990s, studies from 1990 onwards were selected. In addition, since we were interested in the effectiveness of chronic disease management in adult asthmatic patients (16 years and over), we selected studies involving adults. The latter limit did not, however, exclude studies including both adult and non‐adult patients (< 16 years of age).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CA, GG or IPB) independently, and in duplicate, extracted data from selected studies using a tailored extraction form based on the generic Cochrane EPOC Review Group data collection checklist (EPOC 2013a). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and if disagreement persisted an arbitrator was involved, as necessary. Where required, we sought additional information by contacting corresponding authors.

Asthma severity was determined by study self‐report, examination of FEV1 and PEF, or chronicity of asthma symptoms at baseline. Patients were categorised as having severe asthma if they had a mean FEV1 or PEF less than 0.6 of the predicted value, or if they reported daily asthma symptoms (Bateman 2008). Whenever possible, we categorised study populations as 'moderate to severe' if asthmatics with severe asthma were enrolled in the study population, and 'mild to moderate' otherwise.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CA, GG or IPB) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews (EPOC 2013b). Each individual component (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting, baseline characteristics, baseline outcomes measurements, protection against contamination, and other sources of bias) was explicitly rated and categorised as being at low, unclear, or high risk of bias. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or involvement of an arbitrator, or both. If necessary, we contacted study authors for additional information or clarification of the study methods. The same risk of bias table was used for all study designs considered in the review.

For sensitivity analyses, a summary assessment of the risk of bias of each study was done using one key domain of a study level entry (allocation concealment) and one key domain of an outcome level entry (incomplete outcome data) of the core Cochrane Collaboration tool. Studies were considered to be at: low risk of bias (high quality) if the two key domains were at low risk; at unclear risk of bias (moderate quality) if at least one of the key domains was at unclear risk and none at high risk; at high risk of bias (low quality) if at least one of the key domains was at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

In trials reporting score outcomes, we considered the results of the overall score if available. When not available, we selected one score or dimension of the scale as the representative outcome or calculated the average score if possible. If authors reported outcomes at more than one follow‐up period, we selected the period of follow‐up that matched the end of the intervention. The direction of the effect size was standardised so that a positive difference indicated improvement in the intervention group. Results of count data (that is, hospitalisations and ED or unscheduled visits) were treated as rate ratios.

For RCTs and NRCTs, we reported results of dichotomous outcomes as odd ratios (OR) and results of continuous outcomes as mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD) if outcomes related to scores, using post‐intervention (follow‐up) values. We used the latter because there were more studies reporting these values and corresponding standard deviations (SD) compared to change from baseline values. In addition, because the number of patients at baseline and follow‐up were often not the same, change scores for individual studies could not be calculated by hand. Sensitivity analyses, using change from baseline values and change from baseline SDs, were conducted to assess the robustness of results according to the choice of MD estimates if data permitted.

Standardised effect sizes, which were calculated for continuous measures by dividing the difference in mean scores between the intervention and comparison group in each study by an estimate of the (pooled) SD, result in a 'scale free' estimate of the effect for each study. This can then be interpreted and pooled across studies regardless of the original scale of measurement used in each study (Laird 1990). We re‐expressed SMDs using rules of thumb (SMD < 0.4 = small effect, 0.4 to 0.7 = moderate effect , > 0.7 = large effect) or using the most commonly used instrument (back‐transformation of the effect size) to have measures that are clinically useful in daily practice, following the method described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If available, we related the results to the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of the instrument considered.

For CBA studies, we planned to report results of dichotomous outcomes as risk ratio (RR) derived from statistical analyses adjusting for baseline measures (such as logistic regressions) and results of continuous outcomes as MD or SMD derived from statistical analyses adjusting for baseline measures (such as linear regression models, mixed models, or hierarchical models). If adjusted results were not available, study data were excluded from the analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Some cluster‐randomised trials might have a unit of analysis error, when the trial has not adjusted for data clustering. This error implies that confidence intervals and standard errors of effects are smaller (more precise) than they should be (Ukoumunne 1999). We noted the method of randomisation and unit of analysis for each included cluster trial and corrected the sample size by dividing it by the design effect, according to the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the intraclass correlation coefficient or the number of clusters was not reported and attempts to contact the authors were unsuccessful, study data were excluded from the analyses.

Cross‐over trials

In cross‐over trials, only data before cross‐over were considered to avoid any unit of analysis issues.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

In studies with one control group and two or more intervention groups that satisfied our CDM criteria, we combined the intervention groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison to avoid unit of analysis errors. For dichotomous outcomes, both the sample size and the number of patients with events were summed across groups. For continuous outcomes, means and SDs were combined using the formulae presented in table 7.7.a of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted corresponding authors to request missing information whenever the published information did not allow us to decide whether to include or exclude a study. We also contacted them to get missing data (for example, SDs) in order to appropriately describe the study results or perform a meta‐analysis, or both.

In cases where SDs and change from baseline SDs were not reported by the authors, we computed them from reported standard errors, P values, or confidence intervals. If none of these values were reported, we imputed the SD (or change from baseline SD) by calculating the mean SD (or change from baseline SD) of the other studies included in the meta‐analysis using the same scale (following the guidance of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011)). The method of imputation for each relevant study is described in the forest plot footnotes. The potential impact of missing data was addressed in the sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

As suggested in Pigott 2013, we considered heterogeneity in terms of substantive features of complex interventions, methodological and procedural features of studies, as well as research characteristics and reporting context. These sources are included in what others categorise as clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity (Gagnier 2012; Gagnier 2013). Statistical heterogeneity among trials was specifically examined with Cochran's Q test and by calculating the I2 statistic, which describe the proportion of variability in the summary estimate that is due to heterogeneity rather than by chance.

We conducted subgroup analyses to explore clinical heterogeneity in meta‐analyses including at least nine studies, according to the following planned study characteristics (unless specified as post hoc).

Comprehensiveness of the programme

We defined a comprehensive programme as including at least the median number of independent components of included studies (that is, eight components).

Dominant component of the programme

Two review authors (CA, IPB) independently, and in duplicate, selected a dominant component of the programme out of the following three main categories, which are linked to the first three criteria of the operational definition of CDM: organisational component targeting patients, organisational component targeting healthcare professionals or system, or educational component. It was done based on the number of various components present in each category, the main aim of the intervention, and the relative importance of the different components. If we could not determine one dominant component, we classified the CDM programme as mixed. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Presence of limited CDM components in the control group (which were considered as usual care in the specific context of single studies) (post hoc)

We did not perform meta‐regression because there were less than 10 studies in our meta‐analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed the presence of publication bias by means of funnel plots. This was done for exploratory purposes only, as the number of studies included in the meta‐analyses (less than 10) was insufficient to reach a conclusive result.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we conducted meta‐analyses using the Cochrane Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014) to calculate the overall effect size for all relevant primary outcomes. We pooled results of the RCTs and NRCTs separately using the random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986) to incorporate some level of expected heterogeneity among pooled studies. All results were expressed with 95% confidence intervals. Baseline‐adjusted results for CBA studies were also combined separately, if available. For primary outcomes that could not be incorporated in a meta‐analysis, we provided a brief description of the results in the main text.

We presented the most important outcomes of the review in the Table 1, which includes an overall grading of the evidence using the GRADE approach, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This approach specifies four levels of quality (high, moderate, low, very low) for each outcome separately. The highest quality rating is for RCT evidence, but it can be downgraded depending on the presence of the following five factors: study limitations in the design and implementation suggesting high likelihood of bias; indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes); unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (including problems with subgroup analyses); imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals); and high probability of publication bias. Sound observational studies are generally rated as low quality but the following factors can increase the quality of evidence: large magnitude of effect; all plausible confounding would reduce a demonstrated effect; and a dose‐response gradient.

Sensitivity analysis

We explored the influence of the following characteristics on effect size: excluding studies at high risk of bias; excluding studies with imputed SDs; excluding studies using instruments of unknown validity; using change from baseline measures; and using the fixed‐effect model instead of random‐effects model.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

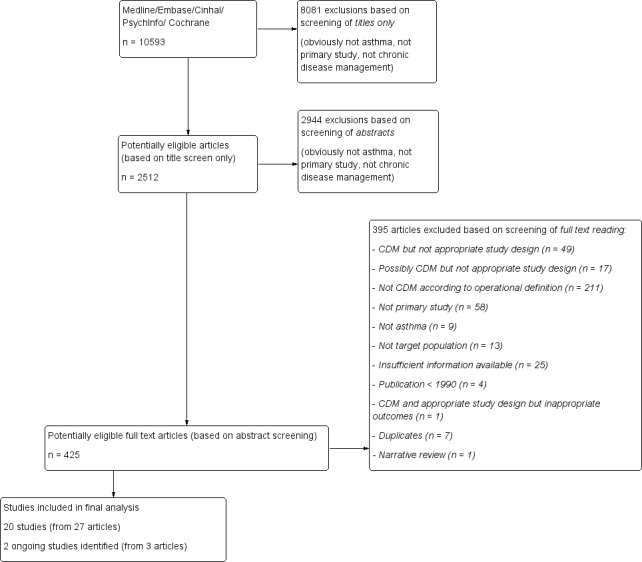

See: Figure 1.

1.

Flow diagram.

We identified a total of 10,593 records to June 2014. We screened the full texts of 425 potentially relevant articles. Of these, we excluded 395 articles, classified 3 articles (corresponding to 2 studies) under ongoing studies and retained 20 studies (from 27 articles) that met all our inclusion criteria.

Included studies

Design and setting

An overview of the characteristics of the included studies is provided in Table 2.

1. Overview of characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Design (allocation) | Country and setting | Intervention name, duration, number of components, dominant component | Patients in intervention group | Patients in control group | Number of reported outcomes |

| RCTs | ||||||

| Armour 2007 | C‐RCT (pharmacy) |

Australia rural and urban pharmacies |

Pharmacy Asthma Care Program 6 months components: 8 dominant component: EDU |

N = 160 women: 67.5% mean age: 47.5 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 186 women: 60.5% mean age: 50.4 moderate‐severe asthma |

Org: 1 Process: 6 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 2 Self‐care: 5 Lung function: 2 |

| Cambach 1997 | RCT | Netherlands local physiotherapy practices |

Rehabilitation programme 3 months components: 6 dominant component: ORG_PT |

N = 22 women: 81.8% mean age: 40 mild‐moderate asthma |

N = 21 women: 66.7% mean age: 53 mild‐moderate asthma |

QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 3 |

| Castro 2003 | RCT | USA inpatients and outpatients in a hospital |

Use of an asthma nurse specialist to provide a multifaceted approach to asthma care for “high‐risk” inpatients 6 months components: 10 dominant component: mixed |

N = 50 women: 80% mean age: 35 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 46 women: 85% mean age: 38 mod‐severe asthma |

HC use: 8 QOL: 1 |

| Charrois 2006 | RCT | Canada community rural pharmacies and PCPs |

Better Respiratory Education and Asthma Treatment in Hinton and Edson (BREATHE) 6 months components: 11 dominant component: mixed |

N = 36 women: 53% mean age: 35.7 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 34 women: 53% mean age: 38.7 moderate‐severe asthma |

Org: 1 Process: 3 HC use: 1 Symptoms/activity: 2 Lung function: 1 |

| Couturaud 2002 | RCT | France outpatient clinic of two university hospitals |

Educational programme in asthmatic patients following treatment readjustment 12 months components: 7 dominant component: EDU |

N = 26 women: 69.4% mean age: 37.8 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 28 women: 66.7% mean age: 38.1 moderate‐severe asthma |

HC use: 1 QOL:1 Symptoms/activity: 3 Self‐care: 3 Lung function: 1 |

| Galbreath 2008 | RCT | USA University Medical Center and PCP |

The South Texas Asthma Management Project (STAMP) 6 months components: 9 dominant component: mixed |

N = 262 women: 77.6% mean age: 42.3 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 124 women: 77.6% mean age: 43.7 moderate‐severe asthma |

Org: 1 Process: 2 HC use: 4 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 2 Lung function: 3 |

| Huang 2009 | RCT | Taiwan outpatient chest department of hospital |

Individualised self‐care education programme 6 months components: 6 dominant component: EDU |

N = 98 women: 29.5% mean age: na moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 50 women: 22% mean age: na moderate‐severe asthma |

Process: 1 HC use: 1 Symptoms/activity: 2 Self‐care: 3 Lung function: 4 |

| Kokubu 2000 | RCT | Japan hospital and patients' home |

Asthma telemedicine system 6 months components: 8 dominant component: ORG_HC |

N = 32 women: 62% mean age: 49.9 asthma severity na |

N = 34 women: 56% mean age: 47.3 asthma severity na |

HC use: 4 Pt satis: 1 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 3 Self‐care: 3 Lung function: 1 |

| Martin 2009 | RCT | USA PCPs |

A community‐based intervention to improve asthma self‐efficacy in African American adults designed by the Chicago Initiative to Raise Asthma Health Equity (CHIRAH) 3 months components: 7 dominant component: EDU |

N = 19 women: 60% mean age: 33 asthma severity na |

N = 18 women: 77% mean age: 37 asthma severity na |

Org: 1 Process: 2 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 3 Self‐care: 3 |

| Mayo 1990 | RCT | USA outpatient chest clinic of a hospital |

Outpatient programme designed to reduce readmissions for asthma exacerbations 8 months components: 6 dominant component: EDU |

N = 47 women: 70.2% mean age: 42 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 57 women: 57.9% mean age: 42 moderate‐severe asthma |

HC use: 1 Symptoms/activity: 1 |

| McLean 2003 | RCT | Canada community pharmacies |

The British Columbia pharmacy asthma study incorporating an asthma care protocol provided by specially trained community pharmacists 12 months components: 7 dominant component: EDU |

N = 119 women: 63% mean age: na asthma severity na |

N = 105 women: 62.9% mean age: na asthma severity na |

HC use: 4 Pt satis: 1 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 4 Self‐care: 1 Lung function: 1 |

| Petro 2005 | C‐RCT (provider) |

Germany PCPs | A disease management programme with a case manager 12 months components: 7 dominant component: ORG_HC |

N = 56 women: 54.2% mean age: 57.3 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 55 women: 44% mean age: 55 moderate‐severe asthma |

HC use: 2 QOL: 3 Symptoms/activity: 1 Lung function: 2 |

| Schatz 2006 | RCT | USA Kaiser Permanente Medical Care program |

Regular care manager and intensive individualised educational visit 12 months components: 11 dominant component: mixed |

N = 30 women: 32.3% mean age: 45 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 15 women: 54.8% mean age: 45.4 moderate‐severe asthma |

Process: 1 HC use: 1 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 2 Self‐care: 1 |

| Smith 2005 | RCT | UK outpatient asthma clinics of a hospital and PCPs |

The Coping with Asthma Study (a home based, nurse led psychoeducational intervention for adults at risk of adverse asthma outcomes) 6 months components: 15 dominant component: EDU |

N = 42 women: 62% mean age: 38.2 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 42 women: 84% mean age: 34.7 moderate‐severe asthma |

QOL: 6 Symptoms/activity: 1 Self‐care: 6 |

| Wilson 2010 | RCT | USA Kaiser Permanente clinics |

The Better Outcomes of Asthma Treatment (BOAT) study 9 months components: 9 dominant component: mixed |

N = 362 women: 56.2% mean age: 46.3 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 189 women: 57.4% mean age: 45.1 moderate‐severe asthma |

Process: 1 HC use: 2 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 5 Lung function: 2 |

| NRCT | ||||||

| Herborg 2001 | C‐NRCT (pharmacy) |

Denmark community pharmacies |

Therapeutic outcomes monitoring (TOM) programme 12 months components: 9 dominant component: ORG_PT |

N = 209 women: 57.6% mean age: 38.8 moderate‐severe asthma |

N = 204 women: 54.7% mean age: 42.4 moderate‐severe asthma |

Org : 3 HC use: 7 Pt satis: 1 QOL: 2 Symptoms/activity: 4 Self‐care: 1 Lung function: 1 |

| CBAs | ||||||

| Feifer 2004 | CBA | USA PCPs in a region covered by a health insurance company |

Population‐based asthma disease management programme using broad‐based educational interventions 12 months components: 7 dominant component: mixed |

N = 35,450 women: 56% mean age: na asthma severity na |

N = 35,450 women: 56% mean age: na asthma severity na |

Process: 3 HC use: 3 QOL: 1 Symptoms/activity: 4 Self‐care: 3 |

| Landon 2000 | CBA | USA community health centres |

Health Disparities Collaboratives disseminating quality improvement techniques 54 months components: ≥ 11 dominant component: ORG_HC |

N = 1696 (total/2) women: 63.5% mean age: 28.4 asthma severity na |

N = 1696 (total/2) women: 67.6% mean age: 34.4 asthma severity na |

Process: 7 HC use: 1 Symptoms/activity: 1 |

| Weng 2005 | CBA | Taiwan outpatient clinics of a hospital and PCPs |

A government‐sponsored outpatient‐based disease management programme 12 months components: 8 dominant component: EDU |

N = 854 women: 44.5% mean age: na asthma severity na |

N = 3188 women: 43% mean age: na asthma severity na |

Pro satis: 1 HC use: 4 |

| Windt 2010 | CBA | Germany PCPs |

Nationwide asthma disease management programme > 12 months components: ≥ 5 dominant component: ORG_HC |

N=317 women: 48.6% mean age: 36.5 asthma severity na |

N=317 women: 44.2% mean age: 36.5 asthma severity na |

Process: 8 HC use: 2 |

RCT: randomised controlled trial, NRCT: non‐randomised controlled trial, CBA: controlled before‐after study, C‐: cluster, PCP: primary care practice, EDU: educational and self‐management support component, ORG_PAT: organisational component targeting patients; ORG_HC organisational component targeting healthcare professionals or the healthcare system, na: not available, HC: healthcare, QOL: quality of life, Org: organisational, Pt satis: patient satisfaction, Pro satis: healthcare professionals' satisfaction

Fifteen studies were RCTs. Out of these 15 studies, one study was a cross‐over trial (Cambach 1997) and two studies were cluster‐RCTs with the unit of allocation being the provider in Petro 2005 and the pharmacy in Armour 2007. The other studies included were one NRCT (Herborg 2001) with a cluster design (unit of allocation: pharmacy) and four CBAs (Feifer 2004; Landon 2007; Weng 2005; Windt 2010) with at least two sites in both the control and intervention groups.

Nine studies recruited patients from primary care clinics or pharmacies (Armour 2007; Charrois 2006; Couturaud 2002; Herborg 2001; Landon 2007; Martin 2009; McLean 2003; Petro 2005; Schatz 2006). Two studies enrolled patients from respiratory care clinics (Cambach 1997; Huang 2009), three other studies recruited hospital inpatients (Castro 2003; Kokubu 2000; Mayo 1990), and four studies enrolled patients from the general population (Feifer 2004; Weng 2005; Wilson 2010; Windt 2010). The remaining two studies enrolled patients from more than one pool: Smith 2005 enrolled patients from both primary care and respiratory care clinics; and Galbreath 2008 recruited patients from the general population, primary care clinics and respiratory care clinics.

Three studies took place in pharmacies (Armour 2007; Herborg 2001; McLean 2003), seven in primary care practices (Cambach 1997; Feifer 2004; Galbreath 2008; Landon 2007; Martin 2009; Petro 2005; Windt 2010), three in outpatient hospital departments (Couturaud 2002; Huang 2009; Mayo 1990), and two in health management organisations (HMOs) (Schatz 2006; Wilson 2010). The remaining studies took place in mixed settings: inpatient and outpatient hospital departments (Castro 2003), inpatient hospital department and patients' home (Kokubu 2000), pharmacies and primary care practices (Charrois 2006), and outpatient hospital departments and primary care clinics (Smith 2005; Weng 2005).

Ten studies were carried out in North America, six in Europe, three in Asia, and one in Australia.

Study population

A total of 10,846 patients were included in 19 studies (between 37 and 4042 patients per study, median 111) when the CBA study reporting data from 70,900 patients from a health insurance company database was excluded (Feifer 2004). The mean age in the intervention and control groups varied between 28.0 and 57.3 years old (median 42.0) and the percentage of women between 22% and 85% (median 59%). Asthma severity in the 13 studies reporting it was rated as moderate‐severe in all except one study, where it was mild‐moderate (Cambach 1997). The baseline predicted FEV1 varied between 22.5% and 89% (median 69%) in eight studies where it was reported. The percentage of patients using inhaled corticosteroids was reported to be between 13.3% and 100% (median 78%) in six studies.

Interventions

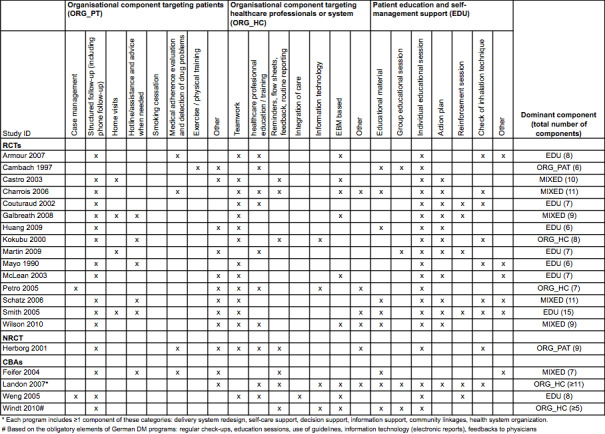

See: Figure 2.

2.

Description of intervention components by study.

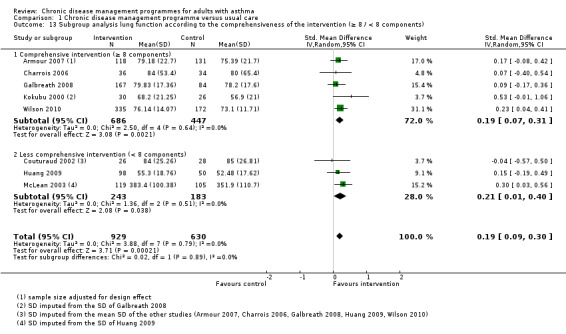

All the programmes met the predefined five CDM criteria: at least one organisational component targeting patients, at least one organisational component targeting healthcare professionals or the healthcare system, patient education or self‐management support or both, the active involvement of two or more healthcare professionals in patient care, and a minimum duration of three months for at least one component. The number of independent components per programme ranged from 6 to 15 (mean 8.4; median 8). Eleven programmes comprising eight or more components (that is, including at least the median number of components) were defined as comprehensive programmes (Armour 2007; Castro 2003; Charrois 2006; Galbreath 2008; Herborg 2001; Kokubu 2000; Landon 2007; Schatz 2006; Smith 2005; Weng 2005; Wilson 2010), and the remaining nine, comprising seven or fewer components, were defined as less comprehensive.

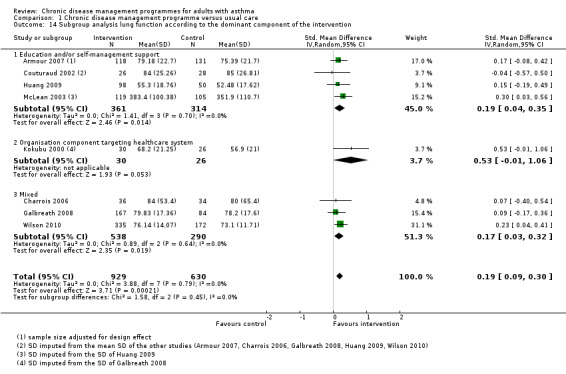

The dominant component was 'educational' in eight studies, 'organisational targeting healthcare professionals or the healthcare system' in four studies, and 'organisational targeting patients' in two studies. We could not determine the dominant component in the remaining six studies, which were classified as mixed.

The most frequently assessed educational component was individual educational sessions (n = 19), followed by providing an action plan for self‐management support (n = 12), and verification of inhalation technique (n = 9). The most frequently assessed organisational component targeting patients involved structured follow‐up (n = 16), followed by having assistance and advice on demand via, for example, a hotline (n = 6). The most frequently assessed organisational component targeting healthcare professionals or the healthcare system involved explicit teamwork and collaborative processes between the healthcare providers (n = 15), followed by education and training of providers (n = 10), and explicit use of evidence‐based medicine supports (n = 9).

The duration of the programmes ranged from 3 months to more than 12 months (median 8.5 months).

Three studies assessed two intervention groups that fulfilled our CDM inclusion criteria (Galbreath 2008; Huang 2009; Wilson 2010). In these studies, we combined the two intervention arms and analysed them as a single intervention group.

Outcome (dependent variable) measures

A wide variety of outcomes were reported in the included studies (see Characteristics of included studies for all available outcomes). Here we describe briefly the outcomes reported in at least three studies. The a priori primary outcomes we defined in the protocol are the only ones we analysed. They are described in more detail in the section presenting the effects of the interventions.

Five studies reported patient participation rates in the programme and four reported the percentage of patients who received the intervention or components, or both. Five studies reported the percentage of patients with an action plan. Six studies reported prescription rates of inhaled corticosteroids and nine reported rates for prescription of other types of medication.

Fifteen studies reported healthcare utilisation outcomes: four reported on any healthcare use (hospitalisation or unscheduled visit, or both), and seven reported asthma‐related or all‐cause hospitalisations and asthma‐related or all‐cause unscheduled visits separately. Five studies reported cost data.

Fourteen studies reported asthma‐specific quality of life scores. Asthma severity scores were reported in nine studies and the number of symptomatic days in four studies. Three studies reported the number of days off work or school due to asthma. Ten studies reported the patients' actual use of medication. The reported self‐management outcomes included patients' asthma knowledge scores in seven studies, self‐efficacy scores in six studies, and compliance with treatment in four studies.

Pulmonary function tests such as FEV1, FEV1/FVC and PEF rate were reported in seven, four, and six studies, respectively.

Missing data

We attempted to contact the authors of 15 of the included studies to request additional data or information. We sent e‐mails to 10 authors as we were unable to identify the correct e‐mail address for the authors of the other five studies. Nine authors responded and five provided additional data. We imputed missing SDs for seven studies (Couturaud 2002; Galbreath 2008; Herborg 2001; Huang 2009; Kokubu 2000; Mayo 1990; McLean 2003).

Excluded studies

We excluded 395 studies after having assessed the full article (see Figure 1). We excluded 211 studies because the intervention did not meet the inclusion criteria of our CDM operational definition. We also excluded studies that used a design not included in our predefined list, for example a before‐after study with only one site for the intervention and control groups, even if they met or possibly met the inclusion criteria for our operational definition of CDM (n = 66). We also excluded studies for the following reasons: inappropriate target population (for example, only children included; n = 13); insufficient information to determine eligibility (n = 25); publication date before 1990, as the first CDM programmes were implemented after that date (n = 4); not primary studies (for example, editorials, comments, reviews; n = 58); and patients without asthma or from a mix of chronic diseases (n = 9). One study fulfilled our eligibility criteria but did not report appropriate outcomes. The primary reason for excluding studies that seemed to meet the eligibility criteria and could be considered relevant by some readers, but were not eligible after further inspection, are listed under Characteristics of excluded studies.

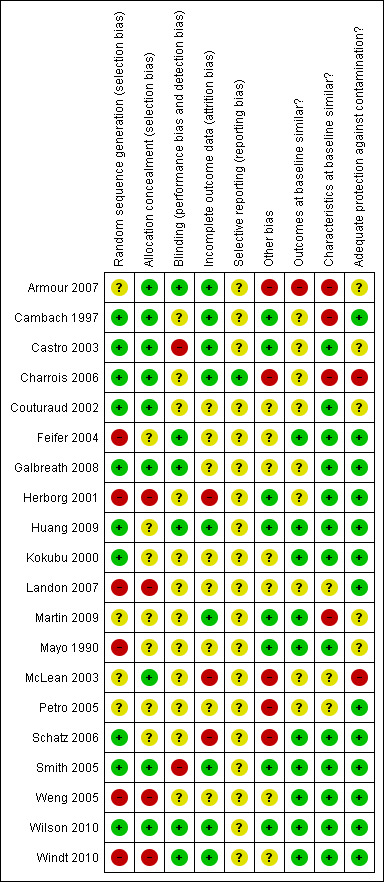

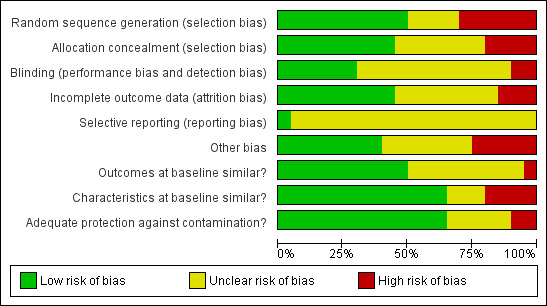

Risk of bias in included studies

The full details of risk of bias judgements by study are described in the Characteristics of included studies table. Figure 3 and Figure 4 summarise these. Using GRADE (see Table 1) the quality of the evidence was rated as moderate or low depending on the outcome.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Ten of the 15 RCTs reported the use of a computerised randomisation programme or a random number table to generate the allocation sequence and were thus considered to be at low risk of bias (Cambach 1997; Castro 2003; Charrois 2006; Couturaud 2002; Galbreath 2008; Huang 2009; Kokubu 2000; Schatz 2006; Smith 2005; Wilson 2010). The process of sequence generation was unclear for four studies, which stated that the study groups were randomly allocated (Armour 2007; Martin 2009; McLean 2003; Petro 2005). The remaining RCT was judged to have a high risk of bias because a quasi‐random method of allocation (last digit of hospital number) was used (Mayo 1990). In the NRCT and CBAs, allocation was judged to be at high risk of bias because of absence of randomisation (Herborg 2001; Landon 2007) and retrospective allocation (Feifer 2004; Weng 2005; Windt 2010).

Allocation concealment was reported in nine of the randomised studies but was unclear in the other six (Huang 2009; Kokubu 2000; Martin 2009; Mayo 1990; Petro 2005; Schatz 2006). Allocation was judged as not having been done in the other studies included (NRCT and CBAs).

Unit of allocation issues

Two of the three studies with a cluster design analysed the data taking into account the clustering effect (Armour 2007; Herborg 2001) and were included in our analyses. The third study (Petro 2005) analysed the data at the patient level, which artificially increases the precision of the statistical tests and can lead to inappropriate conclusions. The results of this study were excluded from all analyses because we were unable to determine the number of clusters in the study and therefore could not adjust the results.

Blinding

Six studies were at low risk of performance and detection bias because claims data were used or the assessors were blinded (Armour 2007; Feifer 2004; Galbreath 2008; Huang 2009; Wilson 2010; Windt 2010). Two studies were judged to be at high risk (Castro 2003; Smith 2005) and the risk for the remaining 12 studies was unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome data were considered complete when 80% or more of randomised patients were included in the analyses, when reasons for attrition were similar across groups, and when dropouts did not differ from the patients analysed. These were reported in nine studies (Armour 2007; Cambach 1997; Castro 2003; Charrois 2006; Huang 2009; Martin 2009; Smith 2005; Wilson 2010; Windt 2010). Outcome data were considered incomplete in three studies because less than 80% of randomised patients were analysed and no reasons were given for the missing data (Herborg 2001; McLean 2003; Schatz 2006). In the remaining eight studies, the number of patients or clusters lost to follow‐up was unclear or information was missing for us to fully assessed attrition bias (Couturaud 2002; Feifer 2004; Galbreath 2008; Kokubu 2000; Landon 2007; Mayo 1990; Petro 2005; Weng 2005).

Selective reporting

Only one study published an article on the design of the trial, reporting the outcomes to be measured in the trial (Charrois 2006), and was considered at low risk of reporting bias. All other studies were categorised as having an unclear risk of reporting bias because of missing information.

None of the exploratory funnel plots appeared asymmetrical.

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline measurement of the outcome of interest was reported in all studies except three (Castro 2003; Couturaud 2002; Galbreath 2008). In 10 of the studies reporting baseline measures, study groups were comparable at baseline for the outcomes (Feifer 2004; Huang 2009; Kokubu 2000; Martin 2009; Mayo 1990; Schatz 2006; Smith 2005; Weng 2005; Wilson 2010; Windt 2010); while in one study important differences were reported (Armour 2007), it was unclear if the differences in baseline measurements of the outcomes between groups were important in five studies. Finally, in one study (Petro 2005) there were important differences at baseline for the secondary outcomes but not the primary outcome (marked as unclear risk of bias).

All studies except two (McLean 2003; Petro 2005) reported patients' characteristics at baseline allowing an assessment of baseline heterogeneity between study groups. Four studies reported important differences between groups (Armour 2007; Cambach 1997; Charrois 2006; Martin 2009) (at high risk of bias), 13 studies reported no important differences (at low risk of bias), and one study (Landon 2007) reported important differences for some characteristics (at unclear risk).

Two studies (Charrois 2006; McLean 2003) were considered at high risk of contamination: trained pharmacists saw both the control and intervention patients. In five studies (Armour 2007; Castro 2003; Couturaud 2002; Martin 2009; Mayo 1990) it was unclear whether patients in the control groups had received more than usual care, which could have improved the care they had received and their outcomes. The other 13 studies were considered at low risk of contamination.

While no further bias was detected in 13 studies, five studies were considered at high risk and two at unclear risk for other bias. In four studies (Armour 2007; Couturaud 2002; McLean 2003; Schatz 2006) there was a risk of recruitment bias due to the design of the study (for example, selection of patients by pharmacist after allocation, low recruitment rate). In two other studies (Charrois 2006; Galbreath 2008) the intervention was poorly implemented with patients allocated to the intervention group completing only parts of the intervention, resulting in potential bias. Finally, in two studies (McLean 2003; Petro 2005) there was a high risk of bias due to analysis errors (unit of analysis error, cluster randomisation but analyses performed with patient level data).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We reported the results using the 10 primary outcomes as predefined in our protocol, followed by the results of subgroup and additional sensitivity analyses. Data from one RCT (Petro 2005) could not be included in the meta‐analyses because we were unable to calculate the design effect due to missing information on the number of clusters (unit of analysis error). Also, we were unable to include the four CBA studies in the meta‐analyses in this report because data provided by authors were either insufficient or unadjusted.

Asthma‐specific quality of life

Fourteen of the 20 studies selected for inclusion in this review measured asthma‐specific quality of life using three validated instruments: the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) or mini‐AQLQ in nine studies; the Living with Asthma Questionnaire (LWAQ) in four studies; and the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRDQ) in one study. However, only nine of these studies provided data at follow‐up and could be included in the main meta‐analysis. Of these, two had missing SDs, which were estimated from the study data using the same instrument.

One study using the mini‐AQLQ was excluded from the meta‐analysis because follow‐up values were not available, due to copyright issues according to the corresponding author (Martin 2009). In this study, the intervention group had improved asthma quality of life compared with the control group after six months of follow‐up. Another study using the LWAQ (Petro 2005) was excluded from the meta‐analysis as data could not be adjusted for unit of analysis error. The study using the CRDQ (Cambach 1997) and one study using the LWAQ (Kokubu 2000) only provided data on change from baseline. They were excluded from the main meta‐analysis but we included them in the sensitivity analysis using change from baseline data. Feifer 2004, using the mini‐AQLQ, was excluded from the meta‐analysis because it was a CBA study and data were available only for the intervention group.

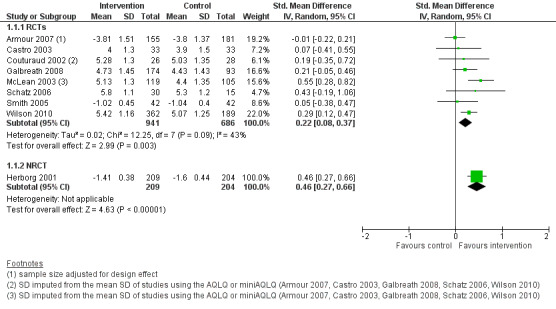

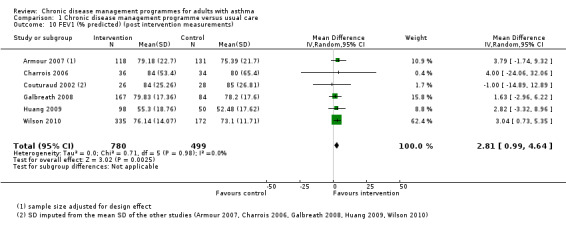

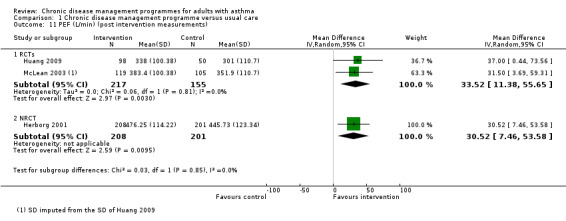

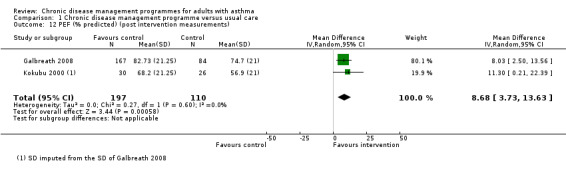

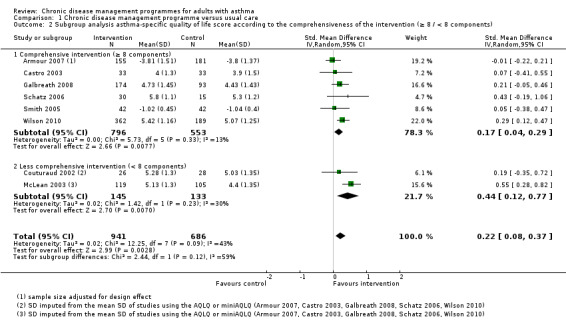

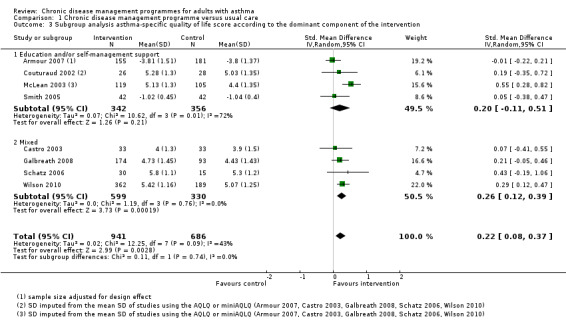

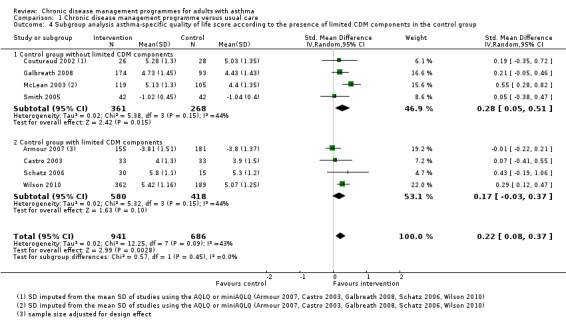

The main meta‐analysis included eight RCTs (Armour 2007; Castro 2003; Couturaud 2002; Galbreath 2008; McLean 2003; Schatz 2006; Smith 2005; Wilson 2010) with a total population of 1627 patients with a follow‐up of 3 to 12 months (see Figure 5; Analysis 1.1). The pooled SMD was 0.22 in favour of CDM (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.08 to 0.37), with a moderate degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 43%). The clinical significance of this SMD was low since, as a rule of thumb, a SMD lower than 0.4 indicates a small effect. In addition, the corresponding difference on the AQLQ scale after back‐transformation (0.30) was lower than the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of the AQLQ or mini‐AQLQ, which is 0.5 according to the developers of the instrument (http://www.qoltech.co.uk/miniaqlq.html). The SMD for the NRCT (Herborg 2001), including 413 patients, was larger than the pooled SMD of RCTs (SMD 0.46, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.66) (see Figure 5; Analysis 1.1).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Chronic disease management programme versus usual care, outcome: 1.1 Asthma‐specific quality of life score (post‐intervention measurements).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic disease management programme versus usual care, Outcome 1 Asthma‐specific quality of life score (post intervention measurements).

Excluding the two RCTs at high risk of bias (McLean 2003; Schatz 2006) from the meta‐analysis reduced the SMD (SMD 0.17, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.28) and the heterogeneity (I2 = 1%).

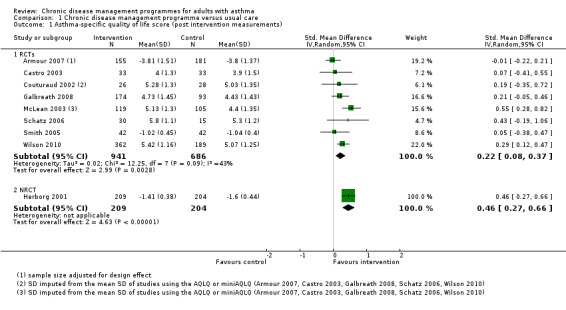

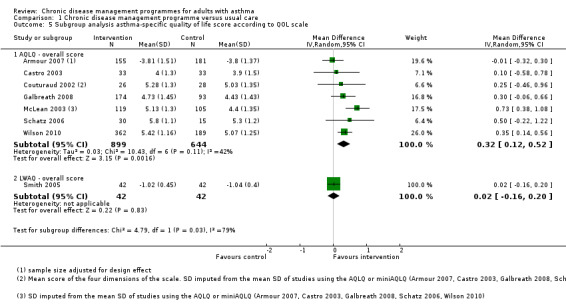

Subgroup analysis by quality of life instrument used

To determine if the heterogeneity of the results was due to the use of different instruments, we analysed the results from each instrument separately. This allowed us: i) to assess the effect of using a single instrument with its specific properties, and ii) to analyse the MD instead of the SMD. Seven studies including 1543 patients used the AQLQ, and one study including 84 patients used the LWAQ (Analysis 1.5). Subgroup analysis of the studies using the AQLQ scale showed a non‐clinically significant MD of 0.32 (clinical significance 0.5 or more) in favour of CDM (95% CI 0.12 to 0.52), while results of the study using the LWAQ scale were inconclusive (MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.20). Heterogeneity was not improved by restricting the analysis to studies using the same instrument (I2 = 42%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic disease management programme versus usual care, Outcome 5 Subgroup analysis asthma‐specific quality of life score according to QOL scale.

Hospitalisations

Nine studies reported hospitalisation data specifically. However, we could not perform a meta‐analysis because the data were skewed and heterogeneous, with wide variability in terms of length of measurement (hospitalisations within the last 1, 6, 8, or 12 months) and reasons for hospitalisation (due to asthma or any cause).

Three RCTs reported a reduction in hospitalisation for asthma in the intervention group compared with the control group. While Castro 2003 reported a 56% reduction in readmissions for asthma in the intervention group compared with the control group over 12 months (MD ‐0.5, 95% CI ‐1.0 to 0.0), Kokubu 2000 reported an 83% reduction in hospitalisations among patients at high risk for hospitalisations in the intervention group after 6 months compared with the control group (MD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.49 to ‐0.09), and Mayo 1990 reported a 67% reduction in hospital readmissions for acute exacerbation in the intervention group after 8 months compared with the control group (MD ‐0.83, 95% CI ‐1.10 to ‐0.56).

In contrast, two RCTs (Galbreath 2008; McLean 2003) and one NRCT (Herborg 2001) did not report any differences between groups. However, the number of hospitalisations per patient during follow‐up was lower in these studies than in the RCTs reporting a reduction: the mean number of hospitalisations per patient was 0.12 during the 12 months of follow‐up in Galbreath 2008, 0.12 during one month of follow‐up in McLean 2003, and 0.04 during the 12 months of follow‐up in Herborg 2001; compared with 0.64, 0.21, and 0.85 in Castro 2003, Kokubu 2000, and Mayo 1990. In Petro 2005 there were no hospitalisations in the intervention group during the 12 months of follow‐up compared with 10% in the control group.

In the CBA study that assessed the impact on hospitalisation in both the intervention and control groups, the number of hospitalisations per patient after 12 months did not differ between the groups (Weng 2005).

Two RCTs (Charrois 2006; Schatz 2006) and two CBA studies (Landon 2007; Windt 2010) that reported the number of hospitalisations and ED visits as one outcome did not report any important differences between groups in the number or percentage of hospitalisations or ED visits during the study follow‐up.

Emergency department (ED) or unscheduled visits

Nine studies reported the number of ED or unscheduled visits. We could not perform a meta‐analysis because the data were skewed and heterogeneous, with wide variability in means and rates at baseline; length of follow‐up from 1 to 12 months; data treated as continuous data, rate or count; and studies including ED or unscheduled visits for asthma only versus for any reason.

Only one RCT (Kokubu 2000) showed a reduction in daytime ED visits per patient in the intervention group compared with the control group during the six month follow‐up, but no difference in night ED visits was observed.

The results from four RCTs and one NRCT did not show any difference between groups for the number of ED or unscheduled visits for asthma per patient during 12 months of follow‐up (Castro 2003; Couturaud 2002; Galbreath 2008; Herborg 2001) and 1 month of follow‐up (McLean 2003). Another RCT showed no difference in the percentage of patients with at least one unscheduled visit after six months of follow‐up (Huang 2009).

In the CBA study that assessed the impact on ED or unscheduled visits in both the intervention and control groups, there was no important reduction between groups in the number of ED visits per patient after 12 months (Weng 2005).

Asthma exacerbations

Asthma exacerbations, which we defined as prompting hospitalisation, an ED or unscheduled medical visit, or systemic rescue glucocorticoids, were not often reported as such in the included studies. We were therefore unable to perform a meta‐analysis due to the lack of data.

Couturaud 2002 and Mayo 1990 reported the number of unscheduled visits for asthma exacerbation and the number of hospitalisations for asthma exacerbation, respectively. In Couturaud 2002 the number of unscheduled visits for asthma exacerbation were comparable between groups, and in Mayo 1990 the number of readmissions for asthma exacerbation per patient for the intervention group was less than for the control group. We could not consider the other studies reporting healthcare use as they did not specify whether the use was for asthma exacerbations.

Finally, five studies reported oral corticosteroids use (Charrois 2006; Couturaud 2002; Herborg 2001; Kokubu 2000; Schatz 2006) but did not specify whether the use was for asthma exacerbation and data were too diverse and heterogenous to be combined. In all studies except one (Couturaud 2002), no important differences between the intervention and control groups were observed. In Couturaud 2002 the percentage of days of oral steroid intake was higher in the intervention group at follow‐up (P = 0.01).

Asthma self‐efficacy

Six studies reported on asthma self‐efficacy, using five different instruments: the Perceived Control of Asthma Questionnaire (PCAQ) in Armour 2007 and Smith 2005, the Asthma Self‐efficacy Scale in Huang 2009, the Chicago Initiative to Raise Asthma Health Equity Asthma Self‐Efficacy Scale in Martin 2009, open‐ended questions measuring self‐management ability in Couturaud 2002, and specific questions measuring self‐management skills in Feifer 2004. The first three instruments have been formerly validated but the questions used in Couturaud 2002 and Feifer 2004 have not. Data from Feifer 2004 were excluded from this meta‐analysis because the study was a CBA and data were only available for the intervention group.

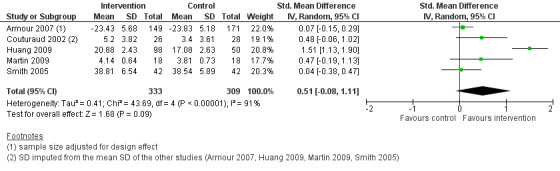

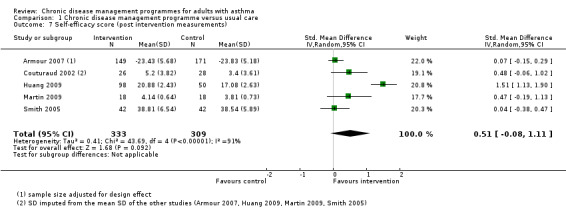

The five studies (Armour 2007; Couturaud 2002; Huang 2009; Martin 2009; Smith 2005) in the meta‐analysis shown in Figure 6 and Analysis 1.7 included a total population of 642 patients, with a follow‐up of 3 to 12 months. The pooled SMD was 0.51 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 1.11) but this difference could not be established, as a negative effect or no difference, could not be ruled out. Pooling indicated a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 91%).

6.