Abstract

Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 exhibits trichloroethene (TCE) oxidation activity with isopropylbenzene (IPB) as the inducer substrate. We previously reported the genes encoding the first three enzymes of the IPB-degradative pathway (ipbA1, ipbA2, ipbA3, ipbA4, ipbB, and ipbC) and identified the initial IPB dioxygenase (IpbA1A2A3A4) as responsible for TCE cooxidation (U. Pflugmacher, B. Averhoff, and G. Gottschalk, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3967–3977, 1996). Primer extension analyses revealed multiple transcriptional start points located upstream of the translational initiation codon of ipbA1. The transcription from these start sites was found to be IPB dependent. Thirty-one base pairs upstream of the first transcriptional start point tandemly repeated DNA sequences overlapping the −35 region of a putative ς70 promoter were found. These repeats exhibit significant sequence similarity to the operator-promoter region of the xyl meta operon in Pseudomonas putida, which is required for the binding of XylS, a regulatory protein of the XylS (also called AraC) family. These similarities suggest that the transcription of the IPB dioxygenase genes is modulated by a regulatory protein of the XylS/AraC family. The construction of an ipb DNA module devoid of this ipb operator-promoter region and the stable insertion of this DNA module into the genomes of different Pseudomonas strains resulted in pseudomonads with constitutive IPB and TCE oxidation activities. Constitutive TCE oxidation of two such Pseudomonas hybrid strains, JR1A::ipb and CBS-3::ipb, was found to be stable for more than 120 generations in antibiotic-free medium. Evaluation of constitutive TCE degradation rates revealed that continuous cultivation of strain JR1A::ipb resulted in a significant increase in rates of TCE degradation.

Trichloroethene (TCE) is an extensively used organic solvent and degreasing agent. As a consequence of its widespread applications, TCE is a frequently detected groundwater and soil pollutant which may persist for long periods in natural environments. Since TCE is a suspected carcinogen (38), there is great interest in bioremediation of TCE-polluted sites and the protection of drinking water supplies from TCE contamination.

Under aerobic conditions TCE can be degraded by means of cooxidation reactions which have been shown to be catalyzed by monooxygenases (2, 12, 13, 15, 18, 26, 30, 40, 46, 52, 54) or dioxygenases (8, 50). With the exception of Nitrosomonas europaea (2) and a spontaneous revertant of a Tn5 mutant of Pseudomonas cepacia G4 (45), TCE-degrading bacteria require the addition of exogenous aromatic or aliphatic inducer substrates. Furthermore, strong competition between TCE and the inducer substrates, such as toluene, phenol, isopropylbenzene, and methane, limits the use of TCE-cooxidizing strains. The application of such strains in the bioremediation of TCE-contaminated sites requires, therefore, a subtle control of substrate addition. To overcome these difficulties, strains oxidizing TCE during growth in the absence of inducer substrates would be very useful.

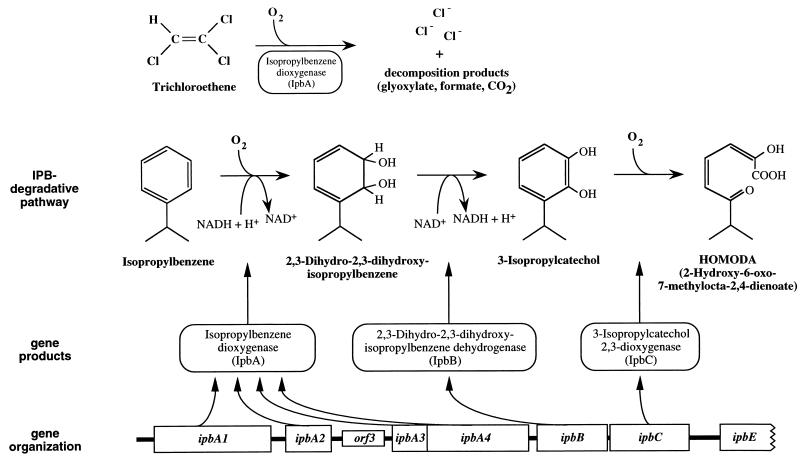

We have studied TCE oxidation by the isopropylbenzene (IPB)-using strains Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 and Rhodococcus erythropolis BD2 (8). The genes for IPB degradation were cloned, sequenced, and expressed in Escherichia coli (27, 41). Inhibitor studies and heterologous gene expression experiments of the ipb genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 clearly showed that the multicomponent IPB dioxygenase, a member of the class IIB ring-activating dioxygenases, mediates TCE cooxidation (Fig. 1). The inducer-independent expression of the IPB dioxygenase (ipbA1A2A3A4) and the 3-isopropylcatechol (3-IPC) 2,3-dioxygenase (ipbC) genes of strain JR1, as observed in recombinant E. coli cells (41), can be assigned to a gene dosage effect due to the high copy number of the cloning vector pBIISK. Despite the advantage of an inducer-independent TCE cooxidation activity, recombinant E. coli cells are not suitable candidates for a TCE bioremediation process since they are not environmentally stable. The identification of the ipb operator-promoter region located upstream of the ipb gene cluster in strain JR1, the generation of an operator-deficient ipbA1A2A3A4BC DNA module, and the stable insertion of this DNA module into the genomes of environmentally relevant pseudomonads resulted in stable Pseudomonas strains with constitutive IPB and TCE oxidation activities. These strains could then be tested for in situ TCE biodegradation efficacy.

FIG. 1.

IPB-degradative pathway in Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 and organization of ipb genes encoding IPB dioxygenase (ipbA1A2A3A4), 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxy-IPB dehydrogenase (ipbB), and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase (ipbC). The IPB dioxygenase has been shown to mediate cometabolic TCE oxidation (41).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and plasmids.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (42) at 30 to 37°C. M5 minimal medium (MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.9 g; KNO3, 3.5 g; KH2PO4, 2.0 g; Na2HPO4 · 2H2O, 8.0 g; vitamin solution [6], 1.0 ml; trace element solution SL9 [49], 1.0 ml; H2O, to 1,000 ml [pH 7.0]) was used for cultivation of the Pseudomonas strains at 30°C. Carbon sources such as glucose, fructose, sucrose, sodium succinate, and sodium gluconate were added to the medium at final concentrations from 20 to 75 mM. M5 medium supplemented with 0.5 g of 0.05% (wt/vol) yeast extract · liter−1 was designated M5′ medium. The following antibiotics were used: ampicillin (100 μg · ml−1); streptomycin (200 μg · ml−1), and kanamycin (100 μg · ml−1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | F−lacZΔM15 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 Δ(lacZYA argF) | 17 |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 [F′ proA+B+ lacIqZΔM15 Tn10], lac mutant | 5 |

| S17.1 (λpir) | tpr SmrrecA thi pro hsdM+ RP4-2-Tc::Mu::Km Tn7 λpir, hsdR mutant | 37 |

| Pseudomonas sp. strains | ||

| JR1 | Wild type | 8 |

| JR1A | Spontaneous IPB− mutant of JR1 | 34 |

| JR1::ipb | JR1::miniTn5Km2::ipbA1A2A3A4BC, Kmr | This study |

| JR1A::ipb | JR1A::miniTn5Km2::ipbA1A2A3A4BC, Kmr | This study |

| CBS-3 | Wild type, DSM 6613 | 48 |

| CBS-3::ipb | CBS-3::miniTn5Km2::ipbA1A2A3A4BC, Kmr | This study |

| Pseudomonas putida | ||

| 548 | Wild type, DSM 548 | 4 |

| 548::ipb | 548::miniTn5Km2::ipbA1A2A3A4BC, Kmr | This study |

| Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 | 25 |

Km, kanamycin; Sm, streptomycin. For relevant genotypes, see reference 3.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Size (kb) | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| pUC18Not | 2.7 | Apr, like pUC18 but MCS flanked with NotI sites | 9 |

| pUT/miniTn5Km2 | 7.0 | Apr Kmr, miniTn5 | 9, 21 |

| pC8 | 14.6 | miniTn5Km2::7.6-kb ipbABC NotI insert from pUN8 | This study |

| pUN8 | 10.4 | Apr, pUC18Not::7.6-kb ipbABC EcoRI insert from pUP3 | This study |

| pUP3 | 10.6 | Apr, pSK+::7.6-kb ipbABC EcoRI-XbaI insert from pUP2 | 41 |

Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin; pSK+, pBlueskriptII SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.); MCS, multiple cloning site.

Recombinant DNA techniques and sequencing.

Plasmid and genomic DNA isolation, restriction endonuclease cleavage, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and other standard recombinant DNA techniques were carried out as described in published protocols (42). Plasmids were transformed into E. coli cells by the calcium chloride method (32). A Midi kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Southern blot analysis of digested genomic DNAs from recombinant Pseudomonas strains was performed on nylon membranes (NEF 976, Gen Screen Plus; Du Pont de Nemours GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany). Probes were labeled with a digoxigenin-dUTP DNA-labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and detected with a digoxigenin luminescence detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolation of DNA fragments from agarose gels was performed with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from GIBCO/BRL GmbH (Eggenstein, Germany). DNA sequencing was carried out by the chain termination method (43) with a Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemicals, Braunschweig, Germany). The α-35S-dATP-labeled DNA fragments were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gradient gels with a Macrophor sequencing unit (Pharmacia LKB, Freiburg, Germany). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by GIBCO/BRL GmbH. The sequences were analyzed by using a software package from the Genetics Computer Group of the University of Wisconsin (10).

Isolation of total RNA and mapping of 5′ ends of mRNA.

Cells of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 were grown in 20 ml of minimal medium with IPB or succinate (50 mM) as the carbon source. In the early exponential growth phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.4 to 0.7), 1 volume of 96% (wt/vol) ethanol was added to stop growth and inhibit RNases. RNA isolation was performed according to the protocol of Oelmüller et al. (39). The primer extension analysis was done as described by Marques et al. (33) except that 200 U of Superscript reverse transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL) was used in the extension reaction mixtures (45°C for 1 h). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 99 μl of TEN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) and digestion with 1 μl of RNase (10 mg/ml) at 37°C for 15 min. cDNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The oligonucleotide primer 5′-GGCTTCCTGCACTTCTT-3′ (PE2) was complementary to bases 20 to 36 of the ipbA1 coding sequence, the primer 5′-ATATAACTTCTTCTTTTAGTTTCAC-3′ (PE4) was complementary to the first 25 bp of the ipbB coding sequence, the primer 5′-CCAAGCTTTTAATGCCC-3′ (PE5) was complementary to bases 3 to 19 of the ipbC coding sequence, the primer 5′-CCACGAACCGTTCCACAA-3′ (PE6) was complementary to bases 62 to 79 of the ipbB coding sequence, and the primer 5′-AACACAGGGCAGCATAGA-3′ (PE7) was complementary to bases 38 and 55 of the ipbE coding sequence. The same labeled oligonucleotides were used in parallel dideoxy chain termination sequencing reactions with pUP2 template DNA to generate a size standard sequence ladder. The recombinant plasmid pUP2 was generated via insertion of a 13.9-kb EcoRI fragment from cosmid pUP1 (41) into pBIISK. This DNA fragment included the ipbA1A2A3A4BC gene cluster and 6.3 kb of DNA located upstream of ipbA1. The products of the reverse transcriptase reactions and the sequencing products were analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide urea gels.

Conjugative transfer of plasmids.

To generate TCE-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains, the pC8 vector was conjugatively transferred into the recipients, with E. coli S17.1 (λpir) as the donor strain. Filter matings were performed on nitrocellulose filters (pore size, 0.2 μm; Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany), which were placed on the surfaces of LB agar plates. Cultures of donor and recipient strains were grown overnight, centrifuged (10 min, 5,000 U per min, 4°C), washed in 0.9% NaCl, and mixed in a ratio of 1:10. Aliquots (200 μl) of the mixture were incubated on the filters at 30°C overnight. Mating pairs were resuspended in 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl and subjected to serial dilutions. pC8 transconjugants were selected and quantified on M5 medium containing kanamycin. The numbers of donor and recipient cells were determined on appropriate growth media. Controls of the recipient strains were incubated under the same conditions to determine the frequencies of spontaneous mutations.

Screening of recombinant strains expressing ipbABC.

Recombinant strains exhibiting IPB dioxygenase activity were detected by the oxidation of indole to indigo. Alternatively, the expression of the complete gene cluster ipbA1A2A3A4BC was detected by the formation of the yellow-colored intermediate 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-7-methylocta-2,4-dienoic acid (HOMODA) in the presence of IPB. 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase expression was monitored by the oxidation of catechol to HOMODA.

Testing the stability of the recombinant strains.

To analyze the stability of the miniTn5::ipbA1A2A3A4BC insertions, individual transconjugants were cultured at 30°C in 5 ml of antibiotic-free M5 medium supplemented with 50 mM gluconate as the carbon and energy source. After the cultures reached the stationary growth phase (OD600 = 10), 5-μl aliquots were transferred into fresh tubes (dilution, 1:1,000). This procedure was repeated 12 times. The numbers of cell divisions proceeding the transfer steps were calculated by counting the numbers of cells at the beginning (defined by the dilution) and at the end of growth in each tube. Cell numbers were quantified by serial dilution of cultures in 0.9% NaCl and by plating of 100-μl aliquots from appropriate dilution steps on solid M5 medium. The expression of the ipb genes was detected by the IPB and 3-IPC oxidation activities of the CFU as described above.

TCE degradation assays.

TCE degradation experiments in batch culture were performed in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks equipped with solvent-tight screw caps and Teflon-lined Mininert valves as sample ports. Alternatively, 125-ml serum bottles with Teflon-lined Mininert valves were used. The flasks were maximally filled up to 10% of their volume with medium, and after sterilization for 20 min at 121°C they were gassed for 15 min with filter-sterilized pure oxygen. The cultures were incubated on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm and 30°C in substrate-limited M5 minimal medium. Growth was monitored by determination of the OD600. Cell protein content was determined with bovine serum albumin as the protein standard in a concentration from 0 to 2.5 mg of protein per assay (44). If TCE degradation was performed with resting cells, as was done in assays in which the release of choride ions was determined, the cultures were previously grown on M5 medium, harvested in the exponential growth phase, washed once, and resuspended in 20 mM sodium–potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) supplemented with 5 mM MgSO4. Cell suspensions were transferred into 125-ml serum bottles and adjusted to the appropriate protein concentrations.

TCE was detected by gas chromatographic head space analysis. Samples (150-μl) of the gas phase were injected into a Chrompack (Frankfurt, Germany) CP9000 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector and a Carbopack B/1% SP-1000 column (Supelco, Bad Homburg, Germany). Operating conditions of the gas chromatograph were as follows: the column temperature was 200°C, the injector and detector temperature was 250°C, and the carrier gas (nitrogen) flow rate was 10 ml/min. For determination of low concentrations of TCE, 5-μl aliquots from a culture’s head space were analyzed with a 438A gas chromatograph equipped with an electron capture detector and a fused silica capillary column (model CP-Sil 8 CB; 50 m by 0.25 mm) from Chrompack. The following operation conditions were used: the column temperature was 80°C, the injector temperature was 200°C, and the detector temperature was 250°C. Nitrogen served as the carrier gas (flow rate, 0.54 ml/min) and makeup gas (flow rate, 30 ml/min). The TCE concentrations were calculated as if TCE had been completely dissolved in the aqueous phase.

Determination of chloride.

The concentrations of chloride ions were analyzed in the supernatants of the resting cell suspensions with an ion-sensitive combination electrode (model 96/17; Orion Research, Cambridge, Mass.). One hundred microliters of ionic-strength adjustor (1 M KNO3) was added to 10-ml calibration standards and supernatants before measuring. Calibration curves were prepared for concentrations from 100 to 800 μM sodium chloride.

Continuous-culture experiments.

A 1.4-liter culture vessel was filled with 400 ml of M5′ medium. The culture was magnetically stirred at 450 rpm. Medium and culture fluid pumping was done with Tygon tubing and pumps (model SP-GS) from Meredos GmbH (Nörten-Hardenberg, Germany). The system was gas and solvent tight. Pure oxygen was used for aeration. During TCE degradation experiments, culture outflow was interrupted and the gas atmosphere was circulated through the system with a solvent-tight air pump. To prevent contamination, the airstream was sterilized by filtration. Addition and sampling of TCE was performed in a 100-ml vessel.

RESULTS

Localization of transcriptional start sites.

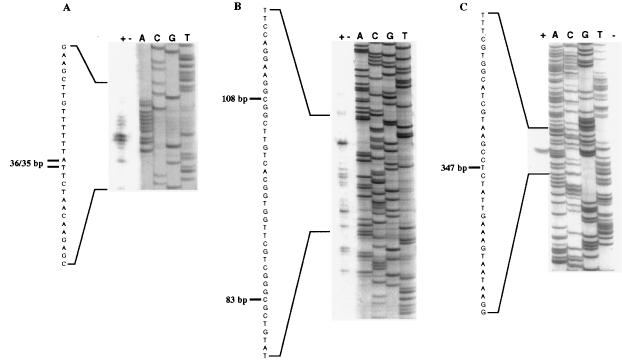

The identification of the ipbA1A2A3A4 promoter should give insight into the regulation of inducible IPB dioxygenase expression and allow the construction of an ipb DNA module useful for the generation of Pseudomonas strains exhibiting constitutive IPB dioxygenase-mediated TCE oxidation activity. Thus, we localized the transcriptional start points of the ipbA genes by primer extension analyses: total RNA was prepared either from Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 cells induced for IPB dioxygenase synthesis by growth in minimal medium with IPB or from uninduced cells grown in minimal medium with succinate. RNA samples annealed with 32P-labeled specific primers, designed to bind downstream of the translational start sites of ipbA1, ipbB, ipbC, and ipbE, respectively, served as templates for reverse transcriptase-mediated extension reactions. cDNAs were detected only in the presence of RNA isolated from induced cultures (Fig. 2). These results indicate that the regulation of ipb gene expression in response to IPB or its metabolic descendants occurs at the transcriptional level. Multiple transcriptional start points were detected upstream of ipbA1. The first transcript started 347 nucleotides upstream of the ATG-methionine translational initiation codon of ipbA1 (Fig. 2C). In addition, four major transcriptional start points were found 108, 83, 36, and 35 nucleotides upstream of the translational initiation codon of ipbA1 (Fig. 2A and B). No transcriptional start points were found upstream of ipbB, ipbC, or ipbE. From these results we conclude that the ipb genes are cotranscribed from transcriptional start points located 35 to 347 bp upstream of the ipbA1 coding sequence.

FIG. 2.

Mapping of the transcriptional start points located upstream of ipbA1. (A to C) Different parts of a single primer extension autoradiogram. The primer extension reactions shown were carried out with a 32P-labeled-ipbA1-specific oligonucleotide (primer PE2) and RNA from wild-type JR1 grown in minimal medium with either IPB (+, induced) or succinate (−, noninduced). The same oligonucleotide was used to generate the sequencing ladder (lanes A, C, G, and T). Lines show the marker cDNA products and indicate transcriptional initiation sites upstream of the ipbA1 translation initiation codon on the coding strand.

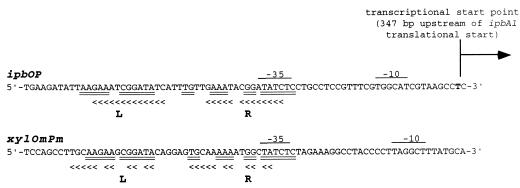

Sequence analysis of a 630-bp DNA region located upstream of the translational start codon of ipbA1 led to the identification of a conserved tandemly repeated DNA sequence of 13 identical base pairs. The tandemly repeated sequences were separated by 7 bp and overlapped the −35 region of a putative ς70 promoter located 378 bp upstream of the ipbA1 translational start codon (Fig. 3). The left and the right tandem repeats were found to show significant similarities to the corresponding repeats of operator regions of the promoter of the xyl meta operon in Pseudomonas putida (Fig. 3). The sequence similarities and the locations of these conserved tandem repeats upstream of the transcriptional start point upstream from the ipbA1 coding sequence support the hypothesis that these tandem repeats make up the operator region of the ipbA promoter. Thus, this region is suggested to be essential for the binding of a regulatory protein modulating inducible expression of the ipb genes. Analysis of the entire 5′ upstream region from −630 to −1 did not reveal any conserved promoter sequences in suitable positions with respect to the additional transcriptional start points −108, −36, and −35 upstream of ipbA1. This finding, together with the fact that the primary −347 start site of the transcript shows maximum intensity, suggests that nucleotide −347 represents the transcriptional start site of the ipb transcript.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of ipbOP with xylOmPm. The < symbols indicate bases conserved in left (L) and right (R) tandem repeats. Double underlines indicate homology between putative ipb and xyl operators. Possible −35 and −10 sequences are overlined. The 104-bp sequence shown starts 346 bp upstream of the translational start codon of ipbA1 and extends to base 440 upstream of the ipbA1 start codon. The arrow indicates the first transcriptional start site detected 347 bp upstream of the ipbA1 translational start codon.

Construction and characterization of Pseudomonas hybrid strains with constitutive IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities.

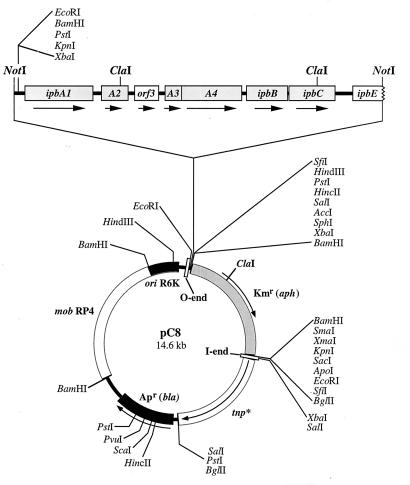

In order to construct an ipb module devoid of the ipbA operator-promoter region, we used a 7.6-kb XbaI-EcoRI DNA fragment (pUP3) (41) bearing the ipbA1A2A3A4BC gene cluster. This DNA fragment was devoid of the conserved operator-promoter region outlined above, since the 7.6-kb DNA fragment starts 181 bases upstream of the ipbA1 translational start site. After extension of pUP3 by an XbaI-EcoRI linker, the resulting EcoRI DNA fragment was flanked with NotI recognition sequences by inserting it into the multiple cloning site of pUC18Not (21). After excision with NotI, the isolated pUP3 fragment was cloned into the single NotI site of pUT/miniTn5Km2, and the resulting 14.6-kb-sized pC8 vector (Fig. 4) was transformed into E. coli S17.1 (λpir). The conjugative transfer of pC8 from E. coli S17.1 (λpir) into spontaneous IPB-negative mutants of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 (strain JR1A), P. putida 548, and Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3 resulted in kanamycin-resistant transconjugants. The transfer frequencies ranged from 1.1 · 10−6 to 4.0 · 10−2 transconjugants/donor and 6.8 · 10−9 to 2.9 · 10−4 transconjugants/recipient (Table 3). No genomic insertions of miniTn5::ipbABC were achieved with Acinetobacter sp. as the recipient. Activity staining of LB medium-grown transconjugants revealed that 1 to 3% of the recombinant Pseudomonas colonies exhibited IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities (Table 3).

FIG. 4.

Restriction map of the transposon vector pC8 (pUT/miniTn5Km2::ipbABC).

TABLE 3.

Transfer proficiency of the ipbABC module

| Recipient strain | Transfer frequencya

|

% of CFU expressing IpbA and IpbC activitiesb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD | TR | spMR | ||

| Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 | 4.0 · 10−2 | 2.9 · 10−4 | <5.1 · 10−9 | 100 |

| Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A | 8.3 · 10−6 | 1.8 · 10−7 | <4.0 · 10−9 | 1 |

| P. putida 548 | 1.1 · 10−6 | 6.8 · 10−9 | <1.3 · 10−9 | 1 |

| Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3 | 3.2 · 10−6 | 8.0 · 10−7 | <1.4 · 10−8 | 3 |

| Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 | NT | NT | NT | |

Transconjugants were selected on succinate minimal medium in the presence of 100 μg of kanamycin per ml. The numbers of transconjugant cells per donor cell (TD), transconjugant cells per recipient cell (TR), and spontaneous mutations per recipient (spMR) are shown.

Percentage of ipbABC-expressing CFU detected by staining for IPB or 3-IPC activity.

To analyze the stability of the mini-Tn5 element and the IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase phenotype, batch cultures of the Pseudomonas strains were transferred with sequential dilutions 12 times into antibiotic-free minimal medium (M5) with gluconate as the carbon source, which yielded >120 generations. After each transfer, 200 to 300 individual colonies of the resulting cell populations were tested for IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities. After eight transfers (80 generations), the first P. putida 548::ipb colonies devoid of the constitutive IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase phenotype were detected. After 120 generations, 20% of the P. putida 548::ipb cells tested did not exhibit any IPB dioxygenase or 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activity, whereas all Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3::ipb and Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb colonies retained their ability to oxidize IPB and 3-IPC in the absence of aromatic inducer substrates.

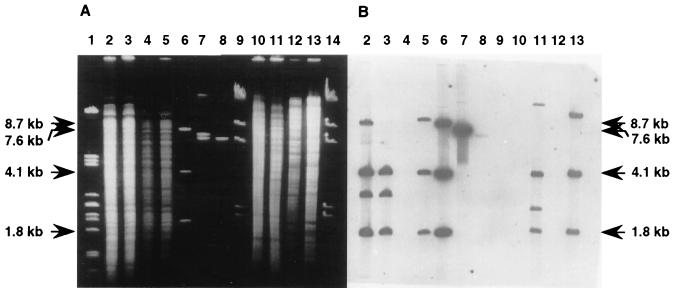

Southern blot analysis of the genomic miniTn5::ipbABC insertions.

For Southern hybridization experiments, total DNA from individual colonies of the Pseudomonas strains outlined above was isolated and restricted with ClaI. The digoxigenin-labeled pUP3 fragment was used as the probe to identify the miniTn5::ipbABC insertions. In the case of a single copy of ipbABC, two distinct chromosomal DNA fragments of 1.8 and 4.1 kb and a third DNA fragment of different sizes were expected to hybridize with the probe due to the locations of the ClaI sites in pC8 and the next adjacent ClaI site in the host genome (Fig. 4). Multiple insertions would result in additional fragments of various sizes.

As shown in Fig. 5B, three bands, one of 9 kb representing the variously sized fragment and the two defined fragments of 4.1 and 1.8 kb, were detected with the genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb (Fig. 5B, lane 5). This confirmed that strain JR1A::ipb contained single copies of the native IPB pathway genes. A fourth band of 8.5 kb (Fig. 5B, lane 2) confirmed the presence of a second copy of the ipbABC gene cluster in the genome of the wild-type transconjugant JR1::ipb. Single insertions of miniTn5::ipbABC were detected in the genome of the transconjugant strain P. putida 548::ipb (Fig. 5, lane 13). Various bands of 2.5 and 12 kb (Fig. 5B, lane 11) were detected in the genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3::ipb, indicating that miniTn5::ipbABC had inserted twice. Southern blot analysis of selected colonies which did not exhibit constitutive IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities revealed that the ipbABC gene cluster was inserted into the host genomes but was apparently not expressed (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Southern blot analysis of the miniTn5::ipbABC insertions. Genomic DNAs were digested with ClaI and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and after transfer to nylon membranes, hybridization with the digoxigenin-labeled pUP3 fragment (ipbABC) was performed. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis; (B) autoradiography. Lanes: 1, λ DNA digested with PstI; 2, genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1::ipbABC; 3, genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1; 4, genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A; 5, genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipbABC; 6, pC8 DNA digested with ClaI; 7, pC8 DNA digested with NotI; 8, pUT/miniTn5Km2 digested with NotI; 9, λ DNA digested with HindIII; 10, genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3; 11, genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3::ipbABC; 12, genomic DNA of P. putida 548; 13, genomic DNA of P. putida 548::ipbABC; 14, λ DNA digested with HindIII.

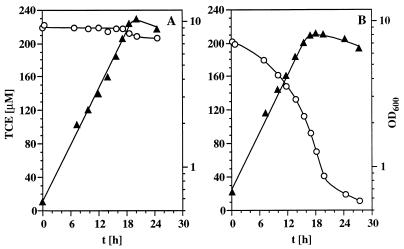

Constitutive TCE degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb.

Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb was chosen to study constitutive TCE degradation more closely. Growth of the JR1 wild type and the JR1A::ipb recombinant strain on gluconate and the ability of these strains to degrade TCE are depicted in Fig. 6. The difference is obvious. Wild-type strain JR1 shows no TCE degradation capability during growth with gluconate; only a very small, but reproducible, decrease of the concentration of TCE in the stationary phase was observed. This may indicate that TCE functions as a weak inducer of IPB dioxygenase or that the enzyme is expressed under starvation conditions after consumption of the carbon source. No TCE degradation was detected in a control experiment with the IPB-negative mutant strain JR1A (data not shown). Immediately after inoculation of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb into fresh gluconate medium containing 200 μM TCE, the growing cultures started TCE oxidation and a TCE degradation rate of 0.15 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 was determined during the onset of the stationary growth phase. Two hundred micromolar TCE was reduced to 10 μM TCE within 28 h of growth. In further experiments, the TCE concentration varied between 100 and 2,000 μM. With 50 mM gluconate as the carbon and energy source and 100 μM TCE, a TCE degradation rate of 0.11 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 was found and TCE degradation was complete after 17 h of incubation (data not shown). The TCE degradation rate increased with increasing concentrations of TCE. Maximal rates of TCE degradation of 0.35 to 0.44 nmol · mg of protein−1 · min−1 were achieved during growth in the presence of 1 to 2 mM TCE. Per mole of TCE degraded, stoichiometric amounts of chloride (3 mol of chloride per mol of TCE) were released (data not shown). Data on the extent of TCE degradation during growth on different substrates are summarized in Table 4. Fructose, gluconate, and glucose were beneficial, whereas succinate and LB medium produced no efficient TCE degradation.

FIG. 6.

Constitutive TCE degradation of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb (B) and the control strain, Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 (A). The strains were grown in gastight 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of M5 medium (50 mM gluconate) in the presence of 200 μM TCE. Growth (▴) was assessed by determining the OD600, and TCE concentration (○) was monitored gas chromatographically. t, time.

TABLE 4.

Effects of growth substrates on constitutive TCE degradation of strain JR1A::ipb

| Substratea | TCE concentrationb (μM) | Final OD600 |

|---|---|---|

| Gluconate | 8 | 9.5–10.0 |

| Succinate | 76 | 8.0–8.5 |

| Glucose | 18 | 9.0–9.5 |

| Fructose | <4 | 10.5–11.0 |

| LB medium | 106 | 15.0–16.0 |

Carbon sources were used at the following concentrations: 50 mM for gluconate, glucose, or fructose and 75 mM for succinate.

TCE was added to a final concentration of 200 μM.

Constitutive TCE degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb in a chemostat.

Strain JR1A::ipb was continuously cultivated in a chemostat under substrate limitation (40 mM gluconate). In order to evaluate the effect of the growth rate on the TCE degradation rate, we analyzed the initial TCE degradation rates in relation to increasing dilution rates from 0.073 to 0.145 h−1. An increase in the rate of dilution had little effect on the OD600, which was found to increase from 8.4 to 8.8. Irrespective of the dilution rate, TCE was rapidly degraded, with high initial rates of degradation between 2.65 and 2.76 nmol · mg of cell protein−1 · min−1. A decrease of the incubation temperature was found to have a significant effect on IPB dioxygenase-mediated TCE cooxidation, such that maximal rates of TCE degradation of 6.0 nmol · mg of protein−1 · min−1 were found when the incubation temperature was lowered to 22°C (data not shown). A further decrease in temperature (20°C) led to a drastic decrease in rates of TCE degradation.

DISCUSSION

Here we have reported on the construction and use of recombinant Pseudomonas strains able to oxidize TCE by the expression of IPB dioxygenase during growth in the absence of aromatic inducer substrates. The maximal rate of TCE oxidation of recombinant Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1A::ipb during growth in batch culture was 0.44 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1. Growth in a chemostat led to initial TCE degradation rates up to 6 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 dependent on the incubation temperature. These rates were within the range of TCE degradation rates of wild-type strains expressing inducer-dependent TCE-oxidizing mono- or dioxygenases; examples of such enzymes are the toluene monooxygenases of Pseudomonas mendocina KR-1 (1 to 2 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 [54]) and P. cepacia G4 (8 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 [15]), the alkene monooxygenase of Xanthobacter strain Py2 (8.2 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 [12]), the ammonia monooxygenase of N. europaea (1.1 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 [2]), the toluene dioxygenase of P. putida F1 (1.8 nmol · min−1 · mg protein−1 [50]), and the IPB dioxygenase of Rhodococcus erythropolis BD1 (1.14 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1 [8]).

Comparable rates of TCE oxidation have also been reported for hybrid dioxygenases, such as the protein products of gene fusions of tod and bph genes from P. putida F1 and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 (16) in E. coli or in pseudomonads, and for the IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-in- duced expression of the soluble methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (mmoXYBZC) in P. putida F1 (24). A significant increase in the rate of TCE degradation was reported with hybrid Pseudomonas strains where the bphA1 gene of the TCE-cooxidizing biphenyl dioxygenase was replaced by the todC1 gene of the toluene dioxygenase of P. putida F1 (47). The maximal rates of TCE degradation obtained with this hybrid dioxygenase in P. putida F1 were about 35-fold higher than those of the toluene-induced P. putida F1 cells. A moderate level of toluene dioxygenase without induction has been observed when the todC1C2BADE gene cluster (plasmid pDTG351) was expressed in P. putida G786 (53). A higher level of enzyme and a subsequent increased rate of TCE oxidation was achieved when the transcription of the tod genes was controlled by an inducible hybrid tac promoter.

Efficient TCE degradation rates have been achieved with the bph tod hybrid dioxygenase of P. putida F1, which like other recombinant or wild-type Pseudomonas strains mentioned above requires induction of the TCE-oxidizing oxygenase. A distinctive advantage of the TCE-degrading strain JR1A::ipb for in situ TCE bioremediation over inducer-dependent strains is the fact that constitutive production of the TCE-cooxidizing dioxygenase avoids competition created by the need of cooxidant and growth substrate binding to the dioxygenase. Also, recombinant E. coli strains exhibiting TCE oxidation activity cannot be considered for in situ bioremediation since they are not stable in soil or groundwater environments. The central purpose of our study, the construction of Pseudomonas strains exhibiting constitutive expression of the TCE-cooxidizing IPB dioxygenase, has led to stable Pseudomonas strains degrading TCE in the absence of aromatic inducer substrates and antibiotic selection. This result and the fact that Pseudomonas species are well adapted to soil and water environments makes this strain a promising candidate applicable to in situ bioremediation.

On the basis of the data obtained, we suggest that the ipbA genes in JR1 are transcribed from multiple transcriptional start points located 347, 108, 83, 36, and 35 nucleotides upstream of the translational initiation codon of ipbA1. Upstream of the first transcriptional start site two tandemly repeated DNA sequences of 13 bp which overlap the putative −35 region of ipbOP have been found. These tandem repeats have significant similarities to the corresponding repeats of the operator sequence of the ipb operon promoter of the IPB pathway genes in Pseudomonas putida RE204 (11a) and the operator sequence of the xyl meta operon promoter (xylOM) of the m- and p-toluate pathway genes in P. putida, which is regulated at the transcriptional level by the regulator protein XylS. The regulator protein XylS, which recognizes the tandemly repeated DNA sequences of xylOM, is a member of the XylS (also called AraC) family (23, 28, 29). Based on these sequence similarities, we suggest that the tandem repeats upstream of ipbA1 are involved in binding of an ipb regulatory protein of the XylS/AraC family.

Although the genetic nature of constitutive TCE degradation activity in strain JR1A::ipb has not yet been elucidated, the fact that the putative operator region upstream of the ipb DNA module was removed and the finding of inducer-independent TCE cooxidation suggest that the chromosomally inserted ipb genes are not transcribed from the native ipb promoter but are transcribed from a host promoter. Especially relevant for this conclusion is the finding that only 1 to 3% of the kanamycin-resistant recombinant strains exhibited constitutive IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities, although the ipb DNA module has also been detected in strains which did not exhibit IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities. Although the genetic natures of the constitutive phenotypes of strain JR1A::ipb, CBS-3::ipb, and 548::ipb described in this paper remain undetermined, these findings suggest that inducer-independent transcription of the ipb genes is initiated from a constitutive host promoter located upstream of the genomic insertion locus of the ipb module. The finding that 100% of the JR1 wild-type transconjugants expressed constitutive IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities might result from an insertion of the ipb module via recombination events into the native ipb genes. In contrast to a transposition event, an insertion of the ipb module within the ipb gene cluster might affect the regulation of the ipb structural genes in strain JR1, thus leading to constitutive ipb gene expression. Furthermore, the constitutive IPB dioxygenase and 3-IPC 2,3-dioxygenase activities of the JR1 transconjugants may also be due to an incorporation of the entire vector plus miniTn5::ipb into the ipb locus, resulting in vector sequences that promote expression of the dioxygenases of the IPB pathway.

The differences in rates of TCE degradation of strain JR1A::ipb relative to the growth substrates (Table 4) indicate a substrate-dependent level of ipb gene expression. This finding suggests that the constitutive expression of the inserted ipb genes is dependent on certain growth conditions and is apparently prevented in the presence of succinate or complex components.

The TCE degradation rates determined for strain JR1A::ipb during growth with gluconate in batch culture were significantly lower than those determined for strain JR1A::ipb during growth in gluconate-limited continuous culture. This finding might result from catabolic repression of the transcription of the ipb operon mediated by elevated concentrations of gluconate. There are at present no hints of a certain physiological reaction which may be involved in signal transduction of putative catabolic repression of the ipb operon in Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1, but analogous repressing effects of easily metabolizable substrates on TCE cooxidation activities have already been reported (7, 11, 14, 22).

It is known that TCE oxidation by oxygenases generates radical intermediates with oxygenase proteins and other cell components, resulting in an inhibition of TCE oxidation and bacterial growth (1, 12, 19, 31, 40, 51). Such highly reactive intermediates are also responsible for the mutagenic and carcinogenic features of TCE when it is oxidized by liver P-450 monooxygenases of mammals (20, 35, 36). Interestingly, strain JR1A::ipb was found to degrade TCE in the presence of up to 2 mM TCE. This significant resistance might be due to the quite low rates of TCE degradation of strain JR1A::ipb in batch culture that result in low intracellular concentrations of toxic intermediates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to V. de Lorenzo for the kind provision of pUT/miniTn5Km2. Many thanks are also due to Ulrich Pflugmacher for providing pUP3 and to Jan Michel for providing strain JR1A.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez-Cohen L, McCarty P L. Effects of toxicity, aeration, and reductant supply on trichloroethylene transformation by a mixed methanotrophic culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:228–235. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.228-235.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arciero D, Vannelli T, Logan M, Hooper A B. Degradation of trichloroethylene by the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:640–643. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann B J. Linkage map of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 807–876. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayly R C, Dagley S, Gibson D T. The metabolism of cresols by species of Pseudomonas. Biochem J. 1966;101:293–301. doi: 10.1042/bj1010293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Short J M. XL1-blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376–378. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claus D, Lack P, Neu B. Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen. Catalogue of strains. 3rd ed. Braunschweig, Germany: Gesellschaft für Biotechnologische Forschung mbH; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyle C G, Parkin G F, Gibson D T. Aerobic, phenol-induced TCE degradation in completely mixed, continuous-culture reactors. Biodegradation. 1993;4:59–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00701455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dabrock B, Riedel J, Bertram J, Gottschalk G. Isopropylbenzene—a new substrate for the isolation of trichloroethene-degrading bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1992;158:9–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00249058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duetz W, Marqués S, de Jong C, Ramos J L, van Andel J G. Inducibility of the TOL catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas putida (pWW0) growing on succinate in continuous culture: evidence of carbon catabolite repression control. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2354–2361. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2354-2361.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Eaton, R. W. Personal communication.

- 12.Ensign S A, Hyman M R, Arp D J. Cometabolic degradation of chlorinated alkenes by alkene monooxygenase in a propylene-grown Xanthobacter strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3038–3046. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.3038-3046.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewers J, Freier-Schröder D, Knackmus H-J. Selection of trichloroethene (TCE) degrading bacteria that resist inactivation by TCE. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:410–413. doi: 10.1007/BF00276540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folsom B R, Chapman P J. Performance characterization of a model bioreactor for the biodegradation of trichloroethylene by Pseudomonas cepacia G4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1602–1608. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1602-1608.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folsom B R, Chapman P J, Pritchard P H. Phenol and trichloroethylene degradation by Pseudomonas cepacia G4: kinetics and interactions between substrates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1279–1285. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1279-1285.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa K, Hirose J, Hayashida S, Nakamura K. Efficient degradation of trichloroethylene by a hybrid aromatic ring dioxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2121–2123. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2121-2123.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harker A R, Kim Y. Trichloroethylene degradation by two independent aromatic-degrading pathways in Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1179–1181. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1179-1181.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry S M, Grbic-Galic D. Influence of endogenous and exogenous electron donors and trichloroethylene oxidation toxicity on trichloroethylene oxidation by methanotrophic cultures from a groundwater aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:236–244. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.236-244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henschler D. Toxizität chlororganischer Verbindungen: Einfluß der Einführung von Chlor in organische Moleküle. Angew Chem. 1994;106:1997–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holtel A, Marqués S, Möhler I, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Carbon source-dependent inhibition of xyl operon expression of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1773–1776. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1773-1776.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Nucleotide sequence of the regulatory gene xylS on the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid and identification of the protein product. Gene. 1986;44:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jahng D, Wood T K. Trichloroethylene and chloroform degradation by a recombinant pseudomonad expressing soluble methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2473–2482. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2473-2482.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juni E. Interspecies transformation of Acinetobacter: genetic evidence for a ubiquitous genus. J Bacteriol. 1972;112:917–931. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.2.917-931.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaphammer B, Kukor J J, Olsen R H. Abstracts of the 90th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1990. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. Cloning and characterization of a novel toluene degradative pathway from Pseudomonas pickettii PKO1, abstr. K-145; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keßeler M, Dabbs E R, Averhoff B, Gottschalk G. Studies of the isopropylbenzene 2,3-dioxygenase and the 3-isopropylcatechol 2,3-dioxygenase genes encoded by the linear plasmid of Rhodococcus erythropolis BD2. Microbiology. 1996;142:3241–3251. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler B, Timmis K N, de Lorenzo V. The organization of the Pm promoter of the TOL plasmid reflects the structure of its cognate activator protein XylS. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:596–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00282749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler B V, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Identification of a cis-acting sequence within the Pm promoter of the TOL plasmid which confers XylS-mediated responsiveness to substituted benzenes. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:699–703. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koh S-C, Bowman J P, Sayler G S. Soluble methane monooxygenase production and trichloroethylene degradation by a type I methanotroph, Methylomonas methanica 68-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:960–967. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.960-967.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S, Wackett L P. Trichloroethylene oxidation by toluene dioxygenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;158:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandel M, Higa A. Calcium-dependent bacteriophage DNA infection. J Mol Biol. 1979;53:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marques S, Ramos J L, Timmis K N. Analysis of the mRNA structure of the Pseudomonas putida TOL meta fission pathway operon around the transcription initiation point, the xylTE and the xylFJ regions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1216:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michel J. Untersuchungen zur Regulation des Isopropylbenzolabbauweges in Pseudomonas sp. JR1. Diploma thesis. Göttingen, Germany: University of Göttingen; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller R E, Guengerich F P. Oxidation of trichloroethylene by liver microsomal cytochrome P-450: evidence of chlorine migration in a transition state not involving trichloroethylene oxide. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1090–1097. doi: 10.1021/bi00534a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller R E, Guengerich F P. Metabolism of trichloroethylene in isolated hepatocytes, microsomes, and reconstituted enzyme systems containing cytochrome P-450. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1145–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Cancer Institute. Carcinogenesis bioassay of trichloroethylene. Chemical Abstracts no. 79-01-6. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (NIH) 76-802. U.S. Washington, D.C: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oelmüller U, Krüger N, Steinbüchel A, Friedrich C G. Isolation of procaryotic RNA and detection of specific mRNA with biotinylated probes. J Microbiol Methods. 1990;11:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oldenhuis R, Oedzes J Y, van der Waarde J J, Janssen D B. Kinetics of chlorinated hydrocarbon degradation by Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b and toxicity of trichloroethylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:7–14. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.7-14.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pflugmacher U, Averhoff B, Gottschalk G. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of isopropylbenzene degradation genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1: identification of isopropylbenzene dioxygenase that mediates trichloroethene oxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3967–3977. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3967-3977.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;85:8934–8938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt K, Liaanen-Jensen S, Schlegel H G. Die Carotinoide der Thiorhodaceae. Arch Microbiol. 1963;46:117–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shields M S, Reagin M J. Selection of a Pseudomonas cepacia strain constitutive for the degradation of trichloroethylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3977–3983. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3977-3983.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shields M S, Montgomery S O, Cuskey S M, Chapman P J, Pritchard P H. Mutants of Pseudomonas cepacia G4 defective in catabolism of aromatic compounds and trichloroethylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1935–1941. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.1935-1941.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suyama A, Iwakiri R, Kimura N, Nishi A, Nakamura K, Furukawa K. Engineering hybrid pseudomonads capable of utilizing a wide range of aromatic hydrocarbons and of efficient degradation of trichloroethene. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4039–4046. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4039-4046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiele J, Müller R, Lingens F. Initial characterization of 4-chlorbenzoate dehalogenase from Pseudomonas sp. CBS-3. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;41:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tschech A, Pfennig N. Growth yield increase linked to caffeate reduction in Acetobacterium woodii. Arch Microbiol. 1984;137:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wackett L P, Gibson D T. Degradation of trichloroethylene by toluene dioxygenase in whole-cell studies with Pseudomonas putida F1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;54:1703–1708. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.7.1703-1708.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wackett L P, Householder S R. Toxicity of trichloroethylene to Pseudomonas putida F1 is mediated by toluene dioxygenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2723–2725. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.10.2723-2725.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wackett L P, Brusseau G A, Householder S R, Hanson R S. Survey of microbial oxygenases: trichloroethylene degradation by propane-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2960–2964. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2960-2964.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wackett L P, Sadowsky M J, Newman L M, Hur H-G, Li S. Metabolism of polyhalogenated compounds by a genetically engineered bacterium. Nature. 1994;368:627–629. doi: 10.1038/368627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winter R B, Yen K-M, Ensley B D. Efficient degradation of trichloroethylene by a recombinant Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology. 1989;7:282–285. [Google Scholar]