Abstract

Background:

Loneliness is common in older adults. Cancer and its treatments can heighten loneliness and result in poor outcomes. However, little is known about loneliness in older adults with cancer.

Objectives:

To provide an overview of the prevalence of loneliness, factors, evolution during the cancer trajectory, impact on treatment, and interventions to reduce loneliness.

Method:

We conducted a scoping review including studies on loneliness in adults with cancer aged 65+. Original, published studies of any designs (excluding case reports) were included. A 2-step screening process was performed.

Results:

Out of 8,720 references, 19 studies (11 quantitative, 6 qualitative, 2 mixed-methods), mostly from the United States, Netherlands, and/or Belgium, and most published from 2010, were included. Loneliness was assessed by the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, and the UCLA loneliness scale. Up to 50% of older adults felt lonely. Depression and anxiety were often correlated with loneliness. Loneliness may increase over the first 6-12 months during treatment. One study assessed the feasibility of an intervention aiming at reducing primarily depression and anxiety and secondarily, loneliness in patients with cancer aged 70+ after five 45-minute sessions with a mental health professional. No studies investigated the impact of loneliness on cancer care and health outcomes.

Conclusion:

This review documents the scarcity of literature on loneliness in older adults with cancer. The negative impacts of loneliness on health in the general population are well known; a better understanding of the magnitude and impact of loneliness in older adults with cancer is urgently warranted.

Keywords: loneliness, scoping review, older adults, cancer

Introduction

The number of older adults (aged 65+) and in particular the oldest old adults (those aged 80+) with cancer is rising worldwide, 1,2 mainly due to improved life expectancy.

There is no consensus on how to define loneliness 3. Recently, international researchers published a consensus statement where they define loneliness as: “a subjective negative experience that results from inadequate meaningful connections” 3. Loneliness has been distinguished from social isolation and social exclusion, where definitions lack consensus, as people may enjoy being on their own 3. While there is increasing interest in interventions to alleviate loneliness in older adults, the evidence base is scarce 9.

Loneliness is common in older adults, with an estimated pooled prevalence of 28.5% 4. As people grow older, social networks can change with the loss of a spouse, family members, or friends. Age-related difficulties in hearing and/or seeing, and the decline in cognitive function or mobility can impede participation in social activities. Loneliness has been associated with poorer cognitive function 5, lower quality of life, and poorer mental health, notably depression 6 and increased mortality risk 7. Informed by past research, reducing loneliness has become a focus of governments and healthcare organizations, such as the United Kingdom’s government’s Loneliness Strategy 8.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis and treatment including, treatment-related symptoms and time required for medical care, may be a lonely experience and may lead to adverse outcomes including reduced survival 10. A literature review on the severity and risk factors associated with loneliness in adults (18+) with cancer showed loneliness increased with time following a cancer diagnosis. It was also associated with a lack of psychological or social support and marital status 11. This review, published in 2014, did not specifically examine older adults, and did not include interventional studies. The ability to identify and provide interventions to reduce loneliness may improve the quality of life of older adults with cancer.

The present scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the literature and research on loneliness in older adults with cancer. Specifically, we aimed to (i) describe the prevalence of loneliness in older adults with cancer; (ii) describe the evolution of loneliness during the cancer trajectory; (iii) identify factors associated with loneliness in older adults with cancer; (iv) describe the impact of loneliness on cancer and treatment outcomes in older adults with cancer; (v) describe tools/strategies to assess loneliness in older adults with cancer; (vi) review and describe interventions to reduce loneliness in older adults with cancer; and (vii) identify gaps in research on this topic.

Methods

The protocol was posted on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/tzkfy/) before performing the review. The scoping review was conducted based on the Arksey and O’Malley approach 12 with inclusion of subsequent extensions by Peters and colleagues 13. The PRISMA-Scr extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines was used for the reporting 14 (supplemental material).

Data sources and search

The search strategy was built by a health sciences research librarian (APA). Comprehensive search strategies were conducted in the following electronic databases: Medline (via OVID), CINAHL (via EBSCOHost), and PsycINFO (via OVID). The Cochrane CENTRAL was also used to identify literature on interventions to alleviate loneliness or perceived social isolation. The librarian performed all searches, with inputs from three authors (SP, VS, and MP). The search was built in OVID Medline (supplemental material), and peer reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) tool 15, before being translated into other databases using their command language if applicable. The search used a multi-string approach combining the concepts of loneliness, cancer, and older adults. The search was built using both the database’s command language and text words. All searches were reported using the PRISMA-S guideline 16.

Eligibility criteria

All original articles published until Dec 21, 2021 were retained without restriction on language, country, or date of publication. Eligible studies were required to report data on loneliness in older adults with cancer aged 65 years or older, regardless of the cancer site or stage. There was no restriction on the study outcomes, and all study designs except for case reports were included. Studies describing loneliness due to or during the COVID-19 pandemic were included. Conference abstracts, editorial letters, commentaries, protocols, dissertations, theses, opinions, editorials, and book chapters were excluded. Literature reviews identified through the search were reviewed to retrieve potential eligible studies, but they were not retained for data abstraction.

In cases where an eligible study contained incomplete information, the corresponding author for the given paper was emailed with a request for further data. Authors were contacted at least two times; when no replies were received, the study was excluded.

Study selection

Articles’ inclusion followed a 3-step process. First, after removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened by independent reviewer pairs of which one was either SP, VS or MP. Any disagreements about inclusion were resolved by an independent third reviewer (SP, VS, or MP). Second, using the same review process for titles and abstracts, the full-text of all retained papers was obtained and assessed to identify those which met the inclusion criteria. Third, the reference list of all included studies was screened by SP, VS, and MP to find additional potential eligible studies.

Method of handling abstract-only.

In cases where a potentially relevant study was only available in abstract form were encountered, the authors of the given study were contacted and asked whether the complete manuscript has been published elsewhere; if not, the study was excluded.

Data collection process and data items.

For each included study, teams of two or three reviewers independently extracted pre-defined data that covered the study characteristics (authors, year), objective, method (study design, country, sample size and method, inclusion and exclusion criteria, analysis method), definition of loneliness, the tool used to assess/measure loneliness, and a summary of the main findings using a Google form. The data abstraction form was designed by SP, reviewed by VS and MP, and then tested by the whole group with one qualitative study 17 and one quantitative study 18. The final data abstraction form is available on https://osf.io/tzkfy/. Once extraction was independently completed, the same two or three reviewers met to discuss potential disagreements.

Assessment of studies quality and risk of bias.

No quality appraisal was conducted per recommendations from Arksey and O’Malley, and the Joanna Briggs Institute 12,13.

Synthesis of results

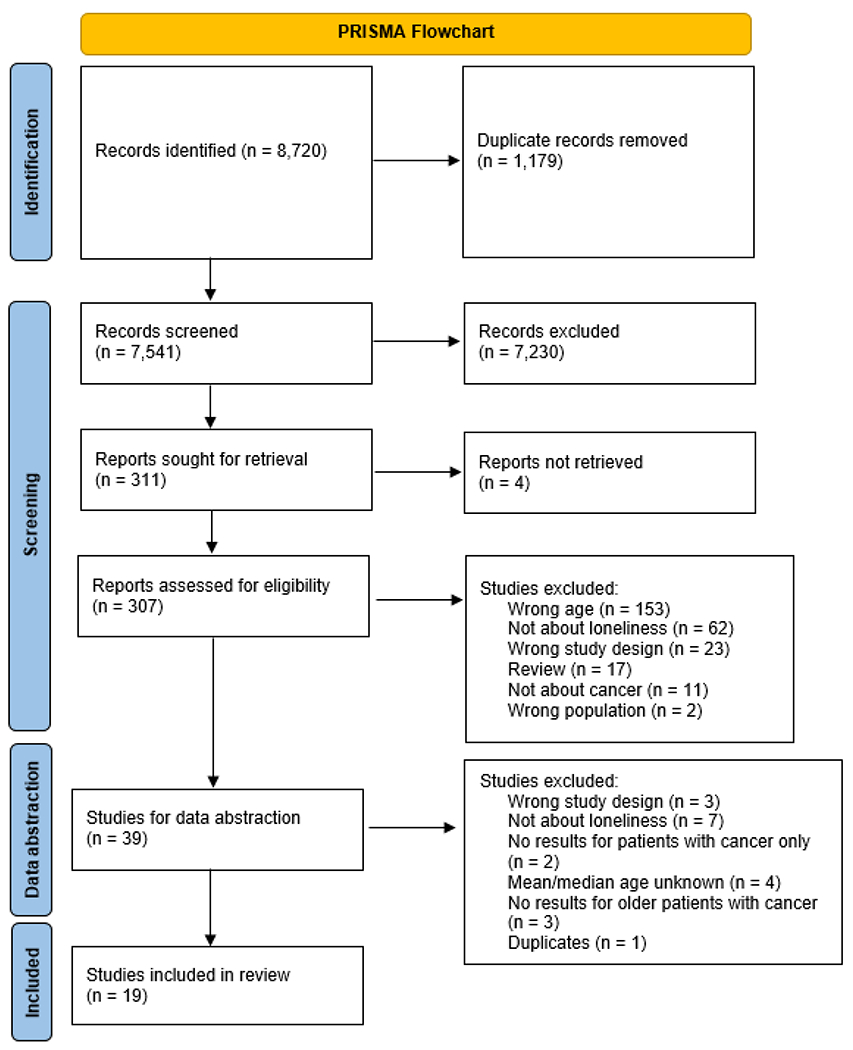

The study selection process was represented using the PRISMA flowchart. Characteristics and main findings of each included study were presented in Tables along with a narrative summary by study design (quantitative or qualitative methods) and specific objective.

Consultation phase

The protocol was presented to members of the International Society for Geriatric Oncology Nursing and Allied Health (SIOG NAH) interest group to gather their feedback on June 16th, 2021; relevant feedback was incorporated. Results were presented to and discussed with 12 SIOG NAH members on December 13th, 2022.

References software used

Covidence, a web-based screening and data abstraction tool, was used for the title and abstract screening and to keep track of the number of references through all the phases of the review.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required for this scoping review.

Results

Out of 8,720 de-duplicated references, we retained 19 studies (Figure 1). References and reasons for the 292 studies excluded are available as Zotero and Mendeley files on osf.io.

Figure 1 - .

PRISMA Flowchart

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 19 studies included 17–35, all but two 19,26 were published since 2010 including five from 2020 18,20,21,27,34. Eleven studies were quantitative studies (including one related to COVID - Table 1) 18,20–22,24,25,27,29,33–35, six were qualitative studies (Table 2) 17,23,26,28,30,31, and two mixed-method studies (Table 3) 19,32. Out of the twelve quantitative studies, seven were cohort studies 20,21,25,27,33–35 two cross-sectional 18,29, one was a retrospective analysis of randomized clinical trials 22 and another one was a feasibility study 24. Analyzed sample sizes ranged from 35 27 to 500 36 for quantitative studies and from 8 23 to 88 26 for qualitative studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Eligible Studies - Quantitative

| First Author | Year and Country | Objectives | Phase | Study Design, Sample Size | Cancer Type | Loneliness Defined? | Loneliness Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pivodic et al. 21 | 2021 Belgium | Examine changes in physical, psychological and social well-being in the last 5 years of life of older people with cancer. | End of life | Prospective cohort N=107 | Breast, prostate, lung, GI | No | Loneliness Scale of De Jong-Gierveld | Despite declines in physical function and increases in death and depressive symptoms over time, loneliness levels did not change close to death. |

| Rentscher et al. 20 | 2021 United States | Examine changes in loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic from the Thinking and Living With Cancer (TLC) study. | Treatment | Prospective cohort N=427 | Breast | Yes | Single item “I felt lonely during the past week” from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) Scale. | Across survivors and matched controls without cancer, loneliness did not change from study enrollment to the last pre–COVID-19 assessment, but significantly increased from the last pre–COVID-19 assessment to the COVID-19 survey, controlling for living circumstances and social support. Across survivors and controls, changes in loneliness were associated with changes in depression and anxiety symptoms. Increases in loneliness were also associated with higher perceived stress. |

| Ashi et al. 18 | 2020 Japan | Explore factors affecting social isolation and loneliness at the time of diagnosis among patients with lung cancer in Japan. | Diagnosis, Treatment | Cross-sectional N=264 | Lung | No | Japanese version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale | Loneliness ranged from 16% to 41%. Univariate analysis: more patients with a history of smoking, receiving welfare (beta coefficient=0.48, 95% CI=0.13-0.83), and presenting with symptoms of dementia (beta coefficient=0.29, 95% CI=0.04-0.53). Patients who were receiving welfare (beta coefficient=0.52, 95% CI=0.13-0.90) and had dementia symptoms (beta coefficient=0.28, 95% CI=0.03-0.54) were more likely to report loneliness. |

| de Boer et al. 34 | 2020 The Netherlands | Assess prevalence of psychosocial problems and longitudinal changes in functional status, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life. | All phases | Prospective cohort N=80 | Breast | No | Loneliness Scale of De Jong-Gierveld | 36% of patients experienced loneliness, with 28% moderate and 8% severe. A non-clinically relevant increase in loneliness was observed between baseline (mean : 2.6 (SD3.1)) and six months (32.1 (3)) in multivariate analysis (adjusted model; b 0.7, 95% CI 0.1–1.2, p = .018). |

| Mathew et al. 27 | 2020 New Zealand | Study barriers and enablers to starting a relationship for patients with prostate cancer and characteristics of patients who were and were not in a relationship. | Not reported | Prospective cohort N=35 | Prostate | No | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Patients with prostate cancer in a relationship had lower levels of loneliness and better perception of emotional support. |

| Hyland et al. 29 | 2019 United States | Investigate the relationship between loneliness, depressive symptoms, quality of life, and social cognitive variables (stigma, social constraint, and cancer-related negative social expectations); Explore loneliness as a mediator between social cognitive variables and depressive symptoms/quality of life in lung cancer. | Treatment | Cross-sectional N=105 | Lung | Yes | 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale-Version 3 (UCLA-V3) | Participants reported a low to moderate level of loneliness. Greater loneliness was associated with greater depressive symptoms and worse QOL. Greater stigma, social constraint, and cancer-related negative social expectations were significantly correlated with loneliness. Loneliness partially mediated the relationship of social cognitive variables with depressive symptoms and QOL. |

| Baitar et al. 35 | 2018 Belgium and the Netherlands | Determine if baseline coping strategies predict changes in psychological and physical well-being, comparing older versus middle aged patients with cancer versus older patients without cancer; Compare baseline coping strategies and well-being in each patient group. | Treatment | Prospective cohort N=263 | Breast, prostate, lung, GI | No | Loneliness Scale of De Jong-Gierveld | 30% impaired loneliness in older adults with cancer at baseline. At one year: Active tackling OR= 1.19 (0.56–2.51); Social support OR= 0.55 (0.25–1.19); Avoidance OR= 1.00 (0.43–2.32); Palliative reacting OR= 1.31 (0.70–2.48) |

| Nelson et al. 24 | 2018 United States | To test the feasibility, tolerability, and acceptability of CARE by examining the rates of eligibility, acceptance, and adherence | After Treatment | Feasibility study N=59 | Breast, Prostate, Lung, Hematological cancer | No | UCLA Loneliness Scale-Short Form | Non-significant reduction in loneliness following use of the intervention. CARE had small effects for reduced loneliness (d=0.19 [CI: −0.34 to 0.72]) at 2 months of assessment. |

| Deckx et al. 33 | 2015 Belgium and the Netherlands | Describe social and emotional loneliness in older patients with cancer compared to younger patients and older patients without cancer; Evaluate relationship of loneliness to changes in common cancer- and ageing-related problems. | Treatment | Prospective cohort N=96 | Breast, colorectal | Yes | Loneliness Scale of De Jong-Gierveld | 22% of older adults felt lonely, and 35% one year later. There were no differences in perceived loneliness (younger versus older patients with cancer). Increase in loneliness was attributed to increase in emotional loneliness. |

| Olson Scott et al. 22 | 2014 United States | Explore issues of relationship with God, symptom distress and feelings of anger and loneliness in people with advanced cancer near the end of life. | End of life | Retrospective secondary analysis of RCT trial data N=354 | Not reported | No | Revised Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale | Loneliness (8.2) mean scores were relatively high, meaning that these patients reported relatively little loneliness. Weak but significant relationship between loneliness and good relationship with God. Loneliness and symptom distress was negatively correlated. |

| Nausheen et al. 25 | 2010 United Kingdom | Investigate association of serum levels of proangiogenic cytokines with different indices of social support and loneliness. | Treatment | Prospective cohort N=51 | Colorectum or colon or rectum | Yes | UCLA Loneliness Scale, Implicit Association Test-Loneliness | Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an angiogenic mechanism through which loneliness may lead to worse cancer-related outcomes. High levels of implicit loneliness was an independent predictor of VEGF immune-expression. |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Eligible Studies - Qualitative

| First Author | Year and Country | Objectives | Phase | Sampling Method and Sample Size | Cancer Type | Analytic approach and Data collection method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunn et al. 31 | 2017 Australia | Explore the motivations of prostate cancer survivors to start a self-help group. | After Treatment | Purposive sampling N=26 | Prostate | Thematic analysis Individual interviews and focus groups | Illness experience included three sub-themes: isolation and neglect; anger and betrayal; and stigma, unable to discuss the cancer experience with social network. Sense of isolation was increased with no provision of psychosocial support. Stigma led to further social isolation. |

| Aoun et al. 17 | 2016 Australia | Explore challenges and biographical life changes in connection with the disease progression. of older people living alone with terminal cancer. | End of life | Purposive and convenience sampling N=51 | Multiple | Thematic content analysis Individual interviews | Biographical disruption theme: adjusting to changing social relationships and networks. Loss of independence and increased loneliness. |

| O’Connor et al. 23 | 2014 Australia | Describe experiences of patients who live alone with community-based palliative care. | End of life | Convenience sampling n=8 | Not reported | Social constructionist approach Individual interviews | Loss of social networks due to disability that led to missing social activities resulting in feelings of isolation and loneliness. |

| Lee et al. 28 | 2013 United States | Explore risk factors contributing to depression in older Korean cancer survivors residing in the metropolitan areas of Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minnesota, and New York City. | After Treatment | Purposive and convenience sampling n=48 | Multiple | Grounded theory Individual interview | Depression was related to loneliness because of lacking relationships with family members or being disconnected from the community, “informant’s personality”, physical changes like physical deterioration or pain and fear of death. |

| Ervik et al. 30 | 2010 Norway | Explore experiences in patients with prostate cancer living with active surveillance or endocrine therapy. | Active surveillance or maintenance therapy | Not reported N=10 | Prostate | Phenomenological hermeneutic approach Individual interviews | Active surveillance is described as “feeling left alone.” |

| Morita et al. 26 | 2004 Japan | Explore existential stress in terminally ill patients with cancer. | End of life | Convenience N=88 | Multiple | Content analysis Individual interviews | A quarter of the participants experienced existential concerns such as isolation that included feeling lonely. |

Table 3.

Characteristics of Eligible Studies – Mixed Methods

| First Author | Year and Country | Objectives | Phase | Study Design, Sampling Method, Sample Size | Cancer Type | Loneliness Defined? | Loneliness Measure, Analytic Approach, Data Collection Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drageset et al. 32 | 2015 Norway | Explore how nursing home patients with cancer experience and cope with loneliness and social isolation. | Not reported | Cross-sectional, Convenience sampling N=60 (quantitative) N=9 (qualitative) | Breast, Prostate, Colorectal, and others undefined | No | Social Provision Scale Content analysis Individual interviews | Loneliness was reported by 57% of the residents, 60% among widows and widowers. In the multivariable analysis, marital status was associated with loneliness and the social provision scale. Participants described loneliness as painful. Some described loneliness as loss of health, home, or important people. Loneliness affected their self-image and self-esteem negatively. |

| Sand et al. 19 | 2007 Sweden | Describe the experiences and triggers of feelings of helplessness and powerlessness in palliative care patients. | End of life | Cross-sectional N=103 | Multiple | No | Authors-developed questionnaire Content analysis Individual interviews | Social loneliness was a triggering factor contributing to feelings of powerlessness/helplessness. |

Most studies were conducted in the United States (n=5) 20,22,24,28,29, followed by the Netherlands and/or Belgium (n=4) 21,33–35, Australia (n=3) 17,23,31, Norway (n=2) 30,32, Japan (n=2) 18,26, New Zealand (n=1) 27, Sweden (n=1) 19, and United Kingdom (n=1) 25.

Half of the included studies included mixed cancer types 17,19,21,24,26,32,33,35, while three included patients with prostate cancer only 27,30,31, two included patients with breast cancer 20,34, two focused on lung cancer 18,29 and one was restricted to colorectal cancer 25. In two studies, the types of cancer were not described 22,23.

Six studies included participants at the end of life 17,19,21–23,26, five studies during the treatment period 20,25,29,33,35, three after treatment 24,28,30, one between diagnosis and treatment 18 and two studies did not restrict inclusion on the stage of the cancer trajectory 31,34. For two studies, the period on the cancer pathway was not mentioned 27,32.

For most studies (n=13 including all six qualitative studies), loneliness was not the main topic of the study 17,19,21–24,26–28,30,31,34,35.

Definition and tools/strategies to assess loneliness in older adults with cancer (Tables 1 and 3)

Authors of four quantitative studies (including the COVID-related study) clearly stated the definition of loneliness they used in their study 20,25,29,33. Hyland et al. and Rentscher et al. defined it as “the discrepancy between perceived and desired level of social connectedness” 20,29. Deckx et al. made the distinction between emotional loneliness, defined as the absence of an intimate figure such a partner or a best friend, and social loneliness, defined as a deficit in a broader group of contacts of social network such as friends and colleagues 33. Finally, Nausheen et al. defined loneliness as “a subjective feeling resulting from unpleasant or inadmissible lack of social relationships” 25.

With respect to tools, the De Jong-Gierveld loneliness scale and the UCLA loneliness scale or adaptations were used to assess loneliness in four 21,33–35 and five studies 18,24,25,27,29, respectively. The two other quantitative studies used a revised version of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale 22 and the COVID-related study used the item, “I felt lonely during the past week” from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) Scale 20. The mixed-method studies used either a single question, “Do you feel lonely?” 32 or created their own questionnaire 19.

The prevalence of loneliness in older adults with cancer (Tables 1 and 3)

Four quantitative studies provided information about the prevalence of loneliness in older adults with cancer 18,33–35. Deckx et al. in Belgium and the Netherlands reported that 22% of adults aged 70+ with breast or colorectal cancer (total sample = 96 - mean age = 77) undergoing treatment felt lonely 33. A follow-up study by Baitar et al. including adults aged 70+ with breast, gastro-intestinal and lung cancer (total sample = 263 - mean age = 76) reported 30% experienced loneliness 35. A study in the Netherlands by de Boer et al. conducted in 80 women aged 70+ (mean age = 77) with breast cancer reported that 36% experienced loneliness 34. Finally, Drageset et al. showed that 57% of nursing home residents with cancer (mean age = 85) reported loneliness 32.

The evolution of loneliness during the cancer trajectory (Table 1)

Three quantitative studies gave information on the trends in loneliness over time.

During the treatment phase, Deckx et al. showed an increase in emotional loneliness over one year in patients aged 70+ first interviewed during their treatment in Belgium and the Netherlands 33. A study conducted in the Netherlands by de Boer et al. also showed an increase in loneliness in patients with breast cancer over a period of six months, but the increase was not considered as clinically relevant 34.

A Belgian study by Pivodic et al. examining loneliness in the last five years of life of 107 older adults with cancer did not show a change in loneliness over time 21.

Factors associated with loneliness in older adults with cancer

Six quantitative studies and six qualitative studies looked at factors associated with loneliness 18,22,25,27,29,32.

Quantitative studies (Table 1)

In a Japanese study by Ashi et al., loneliness was associated with receiving welfare, endorsing symptoms of dementia, and a history of smoking 18.

In a study conducted in New Zealand by Mathew et al., being in a romantic relationship was associated with lower levels of loneliness and better perception of emotional support in older adults with prostate cancer (median age = 68) 27. The protective role of marital status was also reported by Drageset et al. in older adults with cancer living in nursing homes in Norway 32.

In the United Kingdom, Nausheen et al. showed that vascular endothelial growth factor may be a mediator in the relation of loneliness and worse cancer-related outcomes in older adults with colorectal cancer undergoing surgery (mean age = 68) 25.

In a US study of older adults with lung cancer within three months of beginning systemic treatment or radiotherapy, Hyland et al. reported that greater loneliness was correlated with being unmarried, worse performance status, and current smoking 29. Loneliness was also positively associated with depressive symptoms and negatively associated with quality of life. In addition, they found that lung cancer stigma, social constraints (ie. “perceived barriers to disclosure of cancer-related thoughts of feelings”), and cancer-related negative social expectations were correlated with loneliness 29. Finally, loneliness would mediate the relationship between social cognitive variables (eg. stigma, social constraints, and negative social expectations) and depressive symptoms and quality of life.

The relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms was observed in another US study by Olson Scott et al. of older adults with cancer at their end of life 22. The authors also reported that loneliness was positively correlated with a good relationship with God.

Qualitative studies (Table 2)

In older adults with cancer living alone and receiving community-based palliative care services (n=6), O’Connor et al. showed that disability-related loss of social networks and restrictions to social activities/contacts resulted in feelings of social isolation and loneliness 23. Social relationships and networks were important to older adults, but were difficult to maintain due to physical disabilities. The loss of these relationships and activities were missed, resulting in a sense of loneliness 23.

Two studies focused on post-treatment survivorship and loneliness. In a study by Ervik et al. exploring the lived experiences of older men with prostate cancer receiving active surveillance, they described “feeling left alone” without anyone to share problems with outside of their spouse 30. This feeling of being alone was related to a lack of contact with the healthcare team during active surveillance. Despite having spouse/family members around, participants described feeling existentially alone. In a separate study by Dunn et al. with older prostate cancer survivors, isolation was a common theme throughout the illness experience; this was primarily a result of an inability to discuss the cancer experience with their social networks. Further, isolation was experienced as a result of the stigma of having cancer and lack of access to psychosocial support. Thus, survivors created their own network of support groups as a method to combat isolation 31.

Two studies focused on loneliness at the end of life. Aoun et al. assessed the lived experience of older adults with terminal cancer 17. The majority of participants (84%) were living alone by choice. Living with terminal cancer resulted in adjustments in social relationships and social networks and loss of independence, leading to an increase in loneliness. In a study by Morita et al. conducted in Japan, relationship-related concerns were described as existential concerns of terminally ill older adults with cancer 26. Existential concerns resulting from reduced social activity and relationships were described as isolation during the terminal phase which resulted in feelings of loneliness.

In the study by Lee and Jin among older Korean American cancer survivors, loneliness was viewed as related to feeling depressed due to a lack of relationships with families and being disconnected from the community 28.

Interventions to reduce loneliness in older adults with cancer (Table 1)

We identified one study that assessed the feasibility, tolerability, and acceptability of the CARE (Cancer and Aging: Reflections for Elders) intervention aiming at reducing primarily depression and anxiety and secondarily, among others, loneliness in patients with cancer aged 70+ 24. The CARE intervention integrated theories from Folkman and Erikson (expanded by Vallian) and was developed to “encompass several therapeutic approaches to help patients reappraise their situation in the context of achieving ego integrity” [23]. The CARE intervention consisted of five 45-minute structured sessions, including one session on “loneliness and the stigma of cancer and aging”, facilitated by a mental health professional over a period of about seven weeks. Authors hypothesized that the CARE intervention would reduce depressive symptoms, anxiety, and perception of loneliness and isolation, as well as increase coping. At the end of the feasibility study, depression scores were lower but the intervention did not significantly reduce the perception of loneliness.

Covid-related study (Table 1)

One study assessed loneliness and mental health in older breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic; survivors were compared with matched non-cancer controls 20. Overall, results suggest that there was a significant increase in self-reported loneliness (as measured by one item from the CES-D and adapted 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale) from the last pre-COVID survey to May-September 2020 (mean time around 10 months between the 2 surveys) despite controlling for living circumstances and availability of social support. However, there were no differences between survivors and controls. Importantly, across survivors and controls, increases in loneliness were associated with significant increases in depression, anxiety (as measured by the CES-D and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), and higher perceived stress.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to understand the current landscape of evidence on loneliness in older adults with cancer. The review revealed the paucity of quantitative or qualitative studies on loneliness in older adults with cancer. Further, studies were conducted in high-income countries, limiting generalizability. However, interest in loneliness among older adults with cancer seems to be increasing as shown by the number of studies published since 2020. The De Jong-Gierveld loneliness scale 37 and UCLA loneliness scale 38, or their adaptations, were the most used questionnaires to assess loneliness. Loneliness may be experienced by 20-50% of older adults with cancer, depending on the stage of their cancer journey or the individual study.

There was no unifying definition of loneliness across the four studies that provided one definition 20,25,29,33. While recent consensus statements included a definition for loneliness 8, the uptake of this definition in loneliness research in older adults with cancer has not been consistent. Additionally, loneliness may be interrelated with other important domains for older adults with cancer, including social isolation and social support 39. The lack of a clear definition of loneliness and multiple interrelated domains may impact the ability to accurately measure the construct and design relevant interventions.

Loneliness may increase over the first 6-12 months during treatment as shown by Deckx et al. 33 and de Boer et al. 34, suggesting a potential cumulative effect of perceived loneliness as older adults progress through treatment and their cancer continuum. Our findings also suggest that loneliness is potentially associated with many psychosocial and physical problems, including depressive symptoms, physical disabilities, loss of independence, stigma, negative social expectations, and social constraints 17,18,22,23,26–31.

This scoping review also revealed the need for the estimation of the prevalence of loneliness in older adults with cancer, and investigating how loneliness evolves throughout the cancer journey in older adults. General consensus on its definition is needed to compare studies across the care trajectory or through longitudinal work. Several studies identified factors associated with loneliness, mainly psychological. Finer characterization of these factors and an understanding of how loneliness can impact the cancer experience throughout the cancer journey in older adults with cancer is crucial to design relevant interventions to alleviate loneliness and reduce its potential consequences in this unique population.

This scoping review has several limitations that warrant further discussion. First, the search terms and eligibility criteria included several constructs that are interrelated with the construct of loneliness (e.g., social isolation, social relations, social network). While the rigorous screening and data extraction approach strengthened the final selection of retained articles, there is a possibility that some articles were still missed due to inconsistent definitions and lack of alignment with the loneliness construct. Second, studies that did not explicitly provide age of the sample as well as articles that did not have a complete manuscript were not included. Thus, it is unclear whether these studies are truly ineligible. This review also had many strengths, including the adherence to the PRISMA guidelines for reporting, the involvement of an experienced librarian, the use of a thoughtful and systematic search, screening, and data extraction process guided by published scoping review methods.

Conclusion

This scoping review of published literature on loneliness in older adults with cancer suggests that up to half of older adults with cancer felt lonely and loneliness is often correlated with depression and anxiety. This review also revealed a scarcity of literature on this topic. However, the increasing number of studies published over recent years is encouraging. Cancer cases in the older population are predicted to significantly increase over the next decade, highlighting an urgency to address loneliness in older adults with cancer as a priority.

Our findings call for the need for future research to further quantify loneliness in older adults with cancer and to characterize its factors, but also to evaluate interventions to reduce loneliness feeling. From a clinical perspective, the clinical team should assess loneliness and its correlates, ie depressive symptoms and anxiety, during cancer management and understand how to help the patient to overcome these feelings.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study did not benefit from any funding. Dr. Martine Puts is supported by a Canada Research Chair in the care for frail older adults. Dr. Kristen R Haase is supported by a Michael Smith Health Research BC Scholar Award.

List of abbreviations:

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- PRESS

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- UCLA

University of California, Los Angeles

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, et al. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(1):49–58. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilleron S, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Bray F, et al. Estimated global cancer incidence in the oldest adults in 2018 and projections to 2050. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(3):601–608. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prohaska T, Burholt V, Burns A, Golden J, Hawkley L, Lawlor B, et al. Consensus statement: loneliness in older adults, the 21st century social determinant of health? BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e034967. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chawla K, Kunonga TP, Stow D, Barker R, Craig D, Hanratty B. Prevalence of loneliness amongst older people in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0255088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boss L, Kang DH, Branson S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the older adult: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(4):541–553. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barg FK, Huss-Ashmore R, Wittink MN, Murray GF, Bogner HR, Gallo JJ. A Mixed-Methods Approach to Understanding Loneliness and Depression in Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2006;61(6):S329–S339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.S329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(6):907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government’s work on tackling loneliness. GOV.UK. Accessed January 23, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/governments-work-on-tackling-loneliness [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoang P, King JA, Moore S, Moore K, Reich K, Sidhu H, et al. Interventions Associated With Reduced Loneliness and Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(10):e2236676. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konski AA, Pajak TF, Movsas B, Coyne J, Harris J, Gwede C, et al. Disadvantage of men living alone participating in Radiation Therapy Oncology Group head and neck trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4177–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deckx L, van den Akker M, Buntinx F. Risk factors for loneliness in patients with cancer: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European journal of oncology nursing: the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2014;18(5):466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, Mclnerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2021;10(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoun S, Deas K, Skett K. Older people living alone at home with terminal cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2016;25(3):356–364. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashi N, Kataoka Y, Takemura T, Shirakawa C, Okazaki K, Sakurai A, et al. Factors Influencing Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Lung Cancer Patients: A Cross-sectional Study. Anticancer research. 2020;40(12):7141–7145. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sand L, Strang P, Milberg A. Dying cancer patients’ experiences of powerlessness and helplessness. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16(7):853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rentscher KE, Zhou X, Small BJ, Cohen HJ, Dilawari AA, Patel SK, et al. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in older breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Cancer. 2021. ;127(19):3671–3679. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pivodic L, Burghgraeve TD, Twisk J, van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Block LV den. Changes in social, psychological and physical well-being in the last 5 years of life of older people with cancer: a longitudinal study. Age & Ageing. 2021;50(5): 1829–1833. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson Scott L, Law JM, Brodeur DP, Salerno CA, Thomas A, McMillan SC. Relationship With God, Loneliness, Anger, and Symptom Distress in Patients With Cancer Who Are Near the End of Life. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2014;16(8):482–488. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor M A Qualitative Exploration of the Experiences of People Living Alone and Receiving Community-Based Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014;17(2):200–203. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson C, Saracino R, Roth A, Harvey E, Martin A, Moore M, et al. Cancer and Aging: reflections for Elders (CARE): a pilot randomized controlled trial of a psychotherapy intervention for older adults with cancer. 2018;(no pagination), doi: 10.1002/pon.4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nausheen B, Carr NJ, Peveler RC, Moss-Morris R, Verrill C, Robbins E, et al. Relationship between loneliness and proangiogenic cytokines in newly diagnosed tumors of colon and rectum. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72(9):912–916. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f0bc1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita T, Kawa M, Honke Y, Kohara H, Maeyama E, Kizawa Y, et al. Existential concerns of terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialized palliative care in Japan. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2004;12(2): 137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathew S, Rapsey CM, Wibowo E. Psychosocial Barriers and Enablers for Prostate Cancer Patients in Starting a Relationship. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2020;46(8):736–746. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1808549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HY, Jin SW. Older Korean Cancer Survivors’ Depression and Coping: Directions Toward Culturally Competent Interventions. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2013;31(4):357–376. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2013.798756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyland KA, Small BJ, Gray J, Chiappori A, Creelan B, Tanvetyanon T, et al. Loneliness as a mediator of the relationship of social cognitive variables with depressive symptoms and quality of life in lung cancer patients beginning treatment. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28(4):N.PAG-N.PAG. doi: 10.1002/pon.5072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ervik B, Nordøy T, Asplund K. Hit by waves---living with local advanced or localized prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy or under active surveillance. Cancer Nursing. 2010;33(5):382–389. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181d1c8ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn J, Casey C, Sandoe D, Hyde MK, Cheron-Sauer MC, Lowe A, et al. Advocacy, support and survivorship in prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2018;27(2):e12644. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drageset J, Eide GE, Dysvik E, Furnes B, Hauge S. Loneliness, loss, and social support among cognitively intact older people with cancer, living in nursing homes--a mixed-methods study. Clinical interventions in aging. 2015;10:1529–1536. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S88404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deckx L, Akker M, Driel M, Bulens P, Abbema D, Tjan-Heijnen V, et al. Loneliness in patients with cancer: the first year after cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(11):1521–1528. doi: 10.1002/pon.3818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Boer AZ, Derks MGM, de Glas NA, Bastiaannet E, Liefers GJ, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Metastatic breast cancer in older patients: A longitudinal assessment of geriatric outcomes. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2020; 11(6):969–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baitar A, Buntinx F, De Burghgraeve T, Deckx L, Schrijvers D, Wildiers H, et al. The influence of coping strategies on subsequent well-being in older patients with cancer: A comparison with 2 control groups. Psycho-Oncology. 2018;27(3):864–870. doi: 10.1002/pon.4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmucker A, Flannery M, Cho J, Goldfeld K, Grudzen C. Data from emergency medicine palliative care access (EMPallA): a randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of specialty outpatient versus telephonic palliative care of older adults with advanced illness presenting to the emergency departmen. 2021;21(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12873-021-00478-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gierveld JDJ, Tilburg TV. A 6-Item Scale for Overall, Emotional, and Social Loneliness: Confirmatory Tests on Survey Data. Res Aging. 2006;28(5):582–598. doi: 10.1177/0164027506289723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell D, Peplau L, Cutrona C. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(3):472–480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clifton K, Gao F, Jabbari J, Van Aman M, Dulle P, Hanson J, et al. Loneliness, social isolation, and social support in older adults with active cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13(8):1122–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.