Summary

Background

Mental disorders are associated with premature mortality. There is increasing research examining life expectancy and years-of-potential-life-lost (YPLL) to quantify the disease impact on survival in people with mental disorders. We aimed to systematically synthesize studies to estimate life expectancy and YPLL in people with any and specific mental disorders across a broad spectrum of diagnoses.

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, WOS from inception to July 31, 2023, for published studies reporting life expectancy and/or YPLL for mental disorders. Criteria for study inclusion were: patients of all ages with any mental disorders; reported data on life expectancy and/or YPLL of a mental-disorder cohort relative to the general population or a comparison group without mental disorders; and cohort studies. We excluded non-cohort studies, publications containing non-peer-reviewed data or those restricted to population subgroups. Survival estimates, i.e., life expectancy and YPLL, were pooled (based on summary data extracted from the included studies) using random-effects models. Subgroup analyses and random-effects meta-regression analyses were performed to explore sources of heterogeneity. Risk-of-bias assessment was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022321190).

Findings

Of 35,865 studies identified in our research, 109 studies from 24 countries or regions including 12,171,909 patients with mental disorders were eligible for analysis (54 for life expectancy and 109 for YPLL). Pooled life expectancy for mental disorders was 63.85 years (95% CI 62.63–65.06; I2 = 100.0%), and pooled YPLL was 14.66 years (95% CI 13.88–15.98; I2 = 100.0%). Disorder-stratified analyses revealed that substance-use disorders had the shortest life expectancy (57.07 years [95% CI 54.47–59.67]), while neurotic disorders had the longest lifespan (69.51 years [95% CI 67.26–71.76]). Substance-use disorders exhibited the greatest YPLL (20.38 years [95% CI 18.65–22.11]), followed by eating disorders (16.64 years [95% CI 7.45–25.82]), schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (15.37 years [95% CI 14.18–16.55]), and personality disorders (15.35 years [95% CI 12.80–17.89]). YPLLs attributable to natural and unnatural deaths in mental disorders were 4.38 years (95% CI 3.15–5.61) and 8.11 years (95% CI 6.10–10.13; suicide: 8.31 years [95% CI 6.43–10.19]), respectively. Stratified analyses by study period suggested that the longevity gap persisted over time. Significant cross-study heterogeneity was observed.

Interpretation

Mental disorders are associated with substantially reduced life expectancy, which is transdiagnostic in nature, encompassing a wide range of diagnoses. Implementation of comprehensive and multilevel intervention approaches is urgently needed to rectify lifespan inequalities for people with mental disorders.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Life expectancy, Years of potential life lost, YPLL, Premature mortality, Mental illness, Meta-analysis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We performed a systematic search in Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, WOS and Cochran databases from inception to July-31-2023, for studies investigating life expectancy and/or years of potential life lost (YPLL) in people with mental disorders, without language restriction. Key search terms included those relating to life expectancy/YPLL (e.g., “life expectancy”, “years of life lost”), and those relating to any and specific mental disorders (e.g., “mental illness”, “schizophrenia”, “mood disorder”). We identified one systematic review assessing life expectancy and YPLL for people with mental disorders in 24 studies, and two pooled analyses on life expectancy and YPLL for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Thus, no meta-analysis is currently available in the literature that synthesized findings and generated pooled estimates of life expectancy and YPLL for people with any and specific mental disorders across a wide spectrum of mental-disorder diagnoses.

Added value of this study

This study is the first meta-analysis to provide synthesized estimates of life expectancy and YPLL in people with any and specific mental disorders across a wide range of diagnoses. We demonstrated that people with mental disorders exhibited substantially reduced life expectancy relative to the general population (pooled YPLL of 14.66 years), which was transdiagnostic in nature, with substance use disorders having the greatest YPLL, followed by eating disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and personality disorders. More years of life were lost to unnatural causes, especially suicide, than to natural causes. Such longevity gap was observed across countries and persisted over time.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings indicate that health disparities experienced by people with mental disorders have not benefitted equally from enhanced healthcare and improved life expectancy compared with the general population, representing a serious public health concern globally. To rectify the observed lifespan inequalities associated with mental disorders, health outcomes of both less common but more severe disorders as well as of more prevalent but apparently milder conditions should be adequately addressed. Comprehensive and multilevel preventive and interventional approaches are urgently needed to effectively promote physical health and lower suicide risk in people with mental disorders, with consequent reduction in avoidable premature mortality.

Introduction

Mental disorders are highly prevalent and associated with substantial disability. Data from the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that 970 million people (1 in 8 people) worldwide suffered from a mental disorder in 2019,1 and indicated mental disorders as one of the leading causes of disease burden globally.2 Critically, evidence has consistently demonstrated excess mortality in people with a variety of mental disorders, with overall 2–3 times higher risk of premature death than the general population.3, 4, 5, 6 Although suicide is an important cause of premature mortality in people with mental disorders, their excess deaths are mainly attributed to physical diseases.4, 5, 6 The differential mortality has persisted or even widened in recent decades.4,7,8 Health inequalities in people with mental disorders thus constitute a serious public health concern, and reducing such mortality gap is considered an international health priority.9,10

Differential mortality between people with mental disorders and the general population is frequently reported in relative measures, such as standardised-mortality-ratio (SMR) and mortality-rate-ratios. Life expectancy and years of potential life lost (YPLL) are widely-used alterative measures for excess mortality. Life expectancy refers to the number of years a person is expected to live based on the estimate of the average age at death of the standard population, while YPLL is a life expectancy-related metric denoting the difference between the average lifespan of people with the disease of interest and the general population. Life expectancy represents an intuitive and readily understandable health-metric of premature mortality by measuring the impact of diseases on survival, taking into account the relative age at which excess mortality occurs. Specifically, the more pronounced impact on survival by diseases resulting in excess mortality in younger age groups (relative to older age groups) can be captured and quantified by life expectancy and YPLL. A growing body of studies has adopted life expectancy and YPLL to assess excess mortality and revealed an appreciable reduction in lifespan across various mental disorders.7,11, 12, 13 Two recent meta-analyses reported shortened lifespan (YPLL) of 12.8 and 14.5 years in bipolar disorder13 and schizophrenia,11 respectively. Of note, to the best of our knowledge, no study has systematically reviewed and synthesized findings of life expectancy and YPLL in people with any and specific mental disorders across a wide spectrum of diagnoses. Comprehensive and detailed evaluation of longevity gaps associated with mental disorders is crucial for developing effective strategies as well as optimising resource allocation and healthcare service delivery to reduce preventable deaths in people with mental disorders.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, to provide summary estimates of life expectancy and YPLL in people with mental disorders, encompassing a wide range of diagnostic categories. Importantly, stratified analyses on various mental disorders were performed to quantify the disorder-specific life expectancy and the associated magnitudes of lifespan reduction. Meta-regression and subgroup analyses stratified by study characteristics comprising sex, source of study samples, study period, length of follow-up, geographic region, method and diagnostic system to ascertain mental disorders, reference population to derive YPLL, approach for YPLL calculation, and given set-age for lifespan estimation were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity and association of these factors with the pooled estimates of these two health-metrics. Additionally, we investigated YPLL estimates attributable to natural, unnatural and more specific causes of death among people with mental disorders.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses14 (PRISMA). The study protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022321190). As this study was based on published data, no ethical approval or patient consent was obtained.

We systematically searched Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Cochran database for articles published from inception to July 31 2023 without language restriction. The search was performed using the following keywords: (“life expectancy” OR “lifespan” OR “years of potential life lost” OR “years of life lost” OR “life years” OR “life years lost” OR “YPLL” OR “LYL” OR “YLL”) AND (“mental disorder” OR “mental illness” OR “schizophrenia” OR “psychotic” OR “mood disorder” OR “affective disorder” OR “bipolar” OR “manic” OR “depressive” OR “dysthymia” OR “anxiety” OR “phobia” OR “panic” OR “post-traumatic stress disorder” OR “obsessive compulsive” OR “OCD” OR “eating disorder” OR “anorexia nervosa” OR “bulimia nervosa” OR “binge eating” OR “personality disorder” OR “attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders” OR “ADHD” OR “tic disorder” OR “autism” OR “Asperger” OR “dementia” OR “Alzheimer’s disease” OR “substance” OR “drug” OR “alcohol”). The full search strategy for each database is provided in the Supplementary Table S1. We also hand-checked references of all eligible articles and relevant review articles to identify additional eligible studies. Two authors (GHSW and JHCL) performed the searches independently and then compared the results. Studies were included if they fulfilled all of the following criteria: (1) included patients of all ages with any mental disorders; (2) reported data on life expectancy and/or YPLL of a mental-disorder cohort relative to the general population or a comparison group without mental disorders; and (3) cohort studies. We excluded non-cohort studies like case-control studies, reviews, and meta-analyses. Publications containing non-peer-reviewed data (e.g., conference abstracts) or those restricted to population subgroups (e.g., homeless, incarcerated, or military people) were also excluded. Two authors (GHSW and JHCL) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevant studies. Full text of the publications identified at screening was evaluated independently by two authors (VSCF and RSTC) for inclusion, with disagreements resolved through discussion with two other authors (JKNC and WCC).

Data analysis

Data were extracted independently by two authors (JKNC and VSCF), with discrepancies resolved by discussion. Data extraction included information: first author’s name, year of publication, study country/region, study period, data sources, methods to ascertain mental disorders, diagnostic system, sample size of a mental-disorder cohort, set-age for life expectancy estimation, reference population to derive YPLL (i.e., general population or individuals without any/specified mental disorders), sample size of a reference population (for studies using the general population as a comparison group, its sample size was calculated using nationwide data of the census-based population for the median year of the study period), approaches to estimate YPLL (life expectancy/mean age at death), death causes, and estimates of life expectancy and YPLL. For studies where data were only presented graphically, we extracted the data from the respective figures. When authors of the included studies presented data for narrow and broad mental disorder categories (for example, schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and schizophrenia), estimates of the broad category (i.e., schizophrenia-spectrum disorder instead of schizophrenia in this example) were selected for analyses regarding any mental disorders. For studies that derived YPLL estimates of people with mental disorders based on life expectancy of both the general population and people without any/a specified mental disorder, we picked the estimates derived using data of the general population. When studies calculated YPLL estimates based on life expectancy as well as the mean age at death of patients with mental disorders, both estimates were used in subsequent analyses due to their methodological differences. In studies that reported remaining life expectancy at a given set-age (e.g., 15 years), we added this age to the estimate of remaining life expectancy to obtain an expected age at death. In case of missing given set-age, the mean age at baseline assessment was used. In studies that reported multiple estimates of life expectancy using different set-ages (e.g., at birth, 15 years, 25 years, 35 years, etc.), life expectancy estimate derived from the youngest set-age was selected for analysis. For studies that reported estimates of people with mental disorders with and without other comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes) relative to the general population, we calculated the average life expectancy and YPLL weighted by the sample size of each study group. Due to comorbidities, patients can theoretically contribute data to multiple estimates of life expectancy and YPLL. We chose to meta-analyse data on a study-defined basis, whether or not analyses included the patients only once with their primary diagnosis or whether they could have contributed to more than one estimate.

YPLL estimates were calculated in two complementary ways in included studies, based on i) the mean-age-at-death approach, and ii) life-expectancy-gap approach. In the mean-age-at-death approach, YPLL is calculated by subtracting the mean age at the observed death of people with mental disorders from the life expectancy of the general population. The mean age at death is computed by averaging the age at death of people with mental disorders who died during the study period. In the life-expectancy approach, YPLL is quantified by subtracting the estimated life expectancy of people with mental disorders from that of the general population. To calculate the life expectancy of people with mental disorders, age-specific mortality rates are used to generate the total number of person-years contributed by people with mental disorders during the study period, which is then weighted by the total number of people with mental disorders in the study cohort. The two metrics are complementary, as in the mean-age-at-death, only patients who dies during the study period are included, contributing precise age at death estimates, while in the life-expectancy-gap approach, the entire patient cohort is used and contributes to the YPLL estimates. When studies calculated YPLL estimates based on life expectancy as well as the mean age at death of patients with mental disorders, both estimates were used in subsequent analyses due to their methodological differences. We contacted authors to request data if estimates of life expectancy or YPLL stratified by sex and the corresponding SEs were not reported in the publication.

Risk-of-bias assessment was independently performed by two authors (JKNC and RSTC), using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)15 to address the criteria for selection (representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of non-exposed cohort, ascertainment of study outcome, study outcome was not present at baseline), comparability (study controlled for covariates), and outcome (assessment of study outcome, follow-up duration), with disagreements settled through discussion with two other authors (WCC and CSMW). Following the methodology of previous meta-analyses,16 studies with NOS scores ≥7 were regarded as being of high quality.

Random-effects models were applied to generate pooled estimates of life expectancy and YPLL. Heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 statistic.17 Additionally, Cochran’s Q-test was performed to assess the statistical significance for the heterogeneity across studies. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test,18 with p-values <0.1 considered significant. Sensitivity analysis of Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill procedure19 was performed when publication bias was present. To examine potential sources of heterogeneity in meta-analyses for any mental disorders, subgroup analyses stratified by specific mental disorders and pre-specified study characteristics including sex, geographic regions (continents and countries), study period (categorized into “before year 2001”, “year 2001–2010” and “after year 2010”, according to the middle year of the cohort data collection), data source of mental-disorder cohorts, length of study follow-up, method ascertaining mental disorders, diagnostic system, reference population for YPLL estimation, and approach to derive YPLL. Random-effects meta-regression models were then applied to further explore heterogeneity for pre-specified study characteristics (i.e., moderators). A series of univariate meta-regression analyses was conducted to determine whether individual study characteristics could explain heterogeneity for life expectancy and YPLL estimates. Two multivariable meta-regression models incorporating all potential moderators were then performed (one model for life expectancy, another for YPLL) to quantify the proportion of true heterogeneity explained by the moderators (R2) and the residual heterogeneity (I2), and to determine whether the heterogeneity could be significantly accounted for by the model (Qm). To evaluate influence of pre-specified study characteristics (i.e., sex, geographic region, study period, set-age for remaining life expectancy, approach to derive YPLL) on life expectancy and/or YPLL for specific mental disorders, subgroup analyses stratified by these variables were conducted separately for each disorder. For studies that did not report SEs of life expectancy/YPLL estimates, we extrapolated the pooled SE from those studies with reported SEs using a fixed-effect model.11,13,20 For studies that reported CIs, we converted these to SEs before inclusion into fixed-effect models.11,13 Meta-analysis models were performed in R studio (version 4.0.2) with metafor package. For all analyses, except Egger’s test, p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. WCC, JKNC, CUC, and CSMW had full access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study characteristics

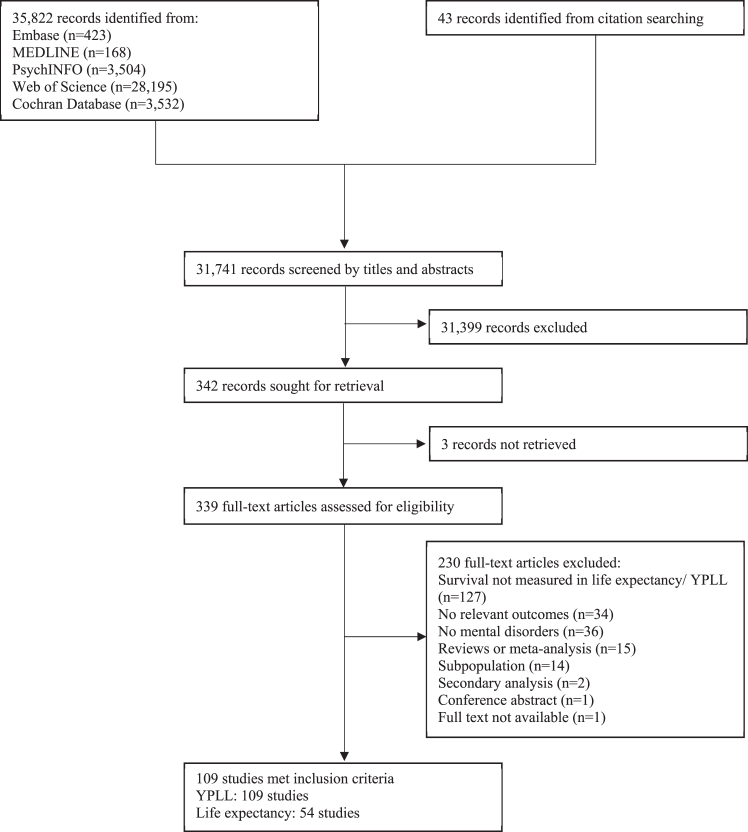

Of 35,865 records identified, 31,741 were screened and 342 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility. Overall, 109 studies5,7,8,12,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35,36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70,71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100,101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125 were included in the meta-analysis (54 for life expectancy and 109 for YPLL) (Fig. 1), comprising 12,171,909 individuals with mental disorders and 34,724,535,980 individuals as the reference population size (including general population and individuals without any/specified mental disorders). Individuals with specific mental disorders were diagnosed with mood disorders (including depressive disorders and bipolar disorder; n = 3,912,695), severe mental illness (primarily including schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder; n = 3,407,306), depressive disorders (n = 2,863,936), schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (n = 2,873,114), neurotic disorders (n = 1,202,764), substance use disorders (n = 1,097,789), personality disorders (n = 667,263), behavioural disorders (n = 208,088), bipolar disorder (n = 203,548), developmental disorders (n = 106,928), eating disorders (n = 89,841), and dementia (n = 17,308). Reasons of study exclusion and references of excluded studies are provided in the Supplementary Table S2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart for study selection. Abbreviation: YPLL: years of potential life lost.

Studies were conducted in the United States (n = 21), Denmark (n = 20), Sweden (n = 11), United Kingdom (n = 11), Finland (n = 8), Taiwan (n = 7), Australia (n = 6), Canada (n = 6), China (n = 4), Italy (n = 4), Germany (n = 3), Norway (n = 3), Spain (n = 3), France (n = 2), Hong Kong (n = 2), Japan (n = 2), Brazil (n = 1), Czech Republic (n = 1), Ethiopia (n = 1), Hungary (n = 1), India (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), and Turkey (n = 1), which belonged to six continents including Europe (n = 56), North America (n = 28), Asia (n = 18), Australia (n = 6), Africa (n = 1), and South America (n = 1). Study periods ranged from 1875 to 2019, which were categorised into “before 2000” (n = 34), “2001–2010” (n = 62), and “after 2010” (n = 18). As shown in Supplementary Table S3, data of study samples were mainly derived from health system case registers (n = 75). Other data sources included health center records (n = 18), insurance health database (n = 7), community survey (n = 7) and combination of different data sources (n = 2). Lengths of study follow-up ranged 1–36 years, which were categorised into “1–5 years” (n = 24), “>5–10 years” (n = 31), and “>10 years” (n = 62). The included studies mainly utilised case register, administrative database or medical records (n = 76) to identify cases with mental disorders. Other methods of case ascertainment included diagnostic interview (n = 19), receipt of relevant healthcare service (n = 7) and prescription of relevant medications (n = 5), self-report (n = 4) and proxy assessment for diagnosis (n = 3; including use of screening instrument for cognitive impairment and inspection of injection site for illicit substance use). Of the 109 studies included in the meta-analysis of YPLL for any/specific mental disorders, the majority of studies used the general population (n = 83) as the reference population for longevity gap estimation. Twenty studies used individuals without any/specific mental disorder as a comparison group, while 11 studies used a specified fixed age (i.e., assumed average life expectancy of the general population, e.g., 75 years of age) for comparison to generate YPLL for individuals with any/specific mental disorder. Concerning approaches to derive YPLL, 42 studies used the mean age at death of individuals with any/specific mental disorder, 62 based their calculations on life expectancy at a given set-age (e.g., at birth, 15 years), and 5 adopted both approaches. Detailed characteristics and references of individual studies included in the meta-analysis are summarised in the Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

Assessment of study quality

Of these 109 studies, all but one had an NOS score ≥7 (104 scored: 8–9; four scored: 7; and one scored: 6), indicating that almost all included studies were of high quality and with low risk of bias. NOS scoring (total and individual NOS item scores) of each of the included studies is summarized in Supplementary Table S6.

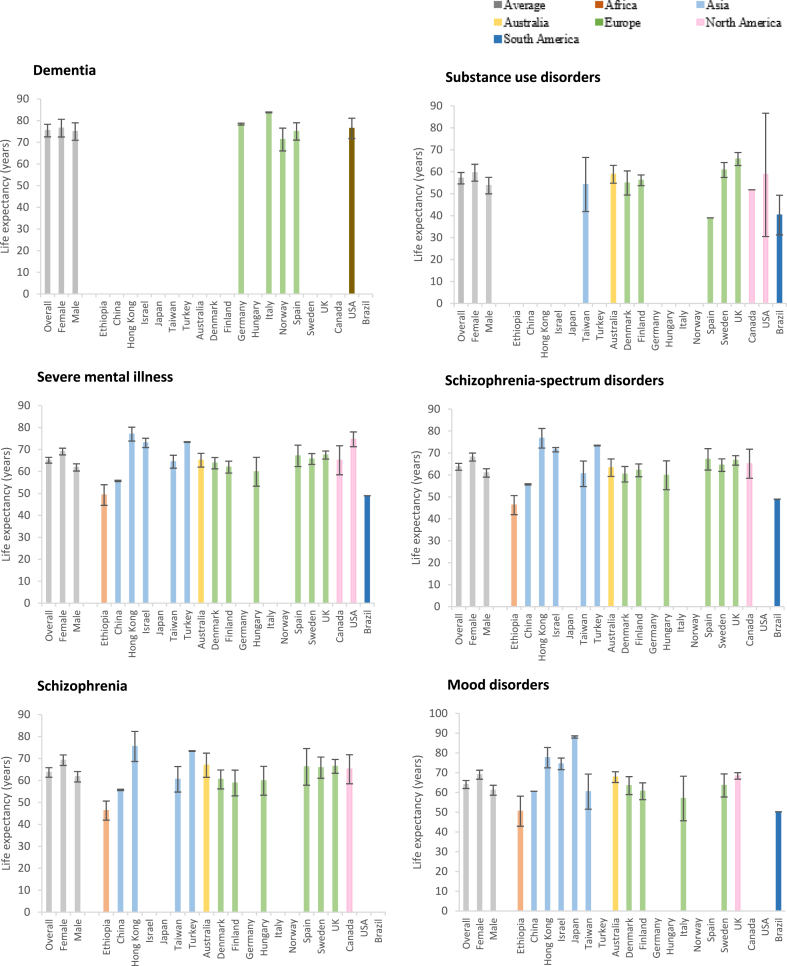

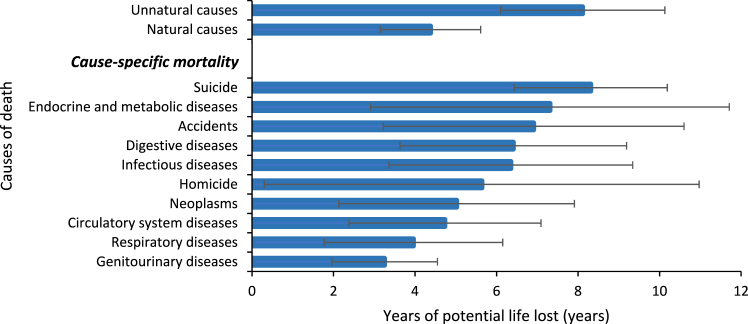

Meta-analysis and subgroup analyses of life expectancy

The pooled life expectancy of individuals with any mental disorders was 63.85 years (95% CI 62.63–65.06, I2 = 100.0%; Table 1, Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S7). A longer life expectancy was observed in females with mental disorders (68.24 years [66.83–69.65], I2 = 100.0%) than their male counterparts (60.98 years [59.34–62.62], I2 = 100.0%). The synthesized estimates in subgroup analyses stratified by source of study samples, length of follow-up, method to ascertain cases of mental disorders, and diagnostic system (Supplementary Table S8) remained largely consistent with those in the original analysis. Concerning specific types of mental disorders (Table 1, Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S7), apart from patients with dementia (75.40 years [72.49–78.31], I2 = 100.0%) whose illness starts later in life, those with neurotic disorders had the longest life expectancy (69.51 years [67.26–71.76], I2 = 100.0%), followed by bipolar disorder (67.30 years [65.29–69.31], I2 = 100.0%) and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (63.70 years [62.13–65.27], I2 = 100.0%). Patients with substance use disorders had the shortest life expectancy (57.07 years [54.47–59.67], I2 = 100.0%). Subgroup analyses for each specific mental disorder according to different set-age for life expectancy estimation are presented in the Supplementary Table S7. For geographic regions (Supplementary Table S9; for countries/regions, see the Supplementary Table S10), the shortest life expectancy was observed in South America (47.27 years [47.25–47.29]), followed by Africa (49.25 years [44.55–53.95]), while the other four continents (i.e., Asia, Australia, Europe and North America) showed comparable life expectancies (62–69 years) in individuals with any mental disorders. For study period, life expectancy of individuals with any mental disorders was lowest “before 2001” (59.86 years [57.70–62.03]), followed by that in “2001–2010” (64.71 years [63.37–66.05]) and “after 2010” (72.46 years [68.88–76.04]) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S9). In addition, patients with severe mental illness and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders showed a significant increase in life expectancy from “2001–2010” to “after 2010”. Pooled estimates of life expectancy for each specific mental disorder across study periods are reported in the Supplementary Table S9.

Table 1.

Life expectancy and YPLL of mental disorders.

| Mental disorders | Life expectancy |

YPLL |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Estimate (95% CI) | No. of studies | Estimate (95% CI) | |

| Any mental disorders | ||||

| Overall | 54 | 63.85 (62.63–65.06) | 109 | 14.66 (13.88–15.45) |

| Female | 45 | 68.24 (66.83–69.65) | 64 | 13.14 (12.17–14.12) |

| Male | 46 | 60.98 (59.34–62.62) | 68 | 14.94 (13.89–15.98) |

| Dementia | ||||

| Overall | 7 | 75.40 (72.49–78.31) | 12 | 8.58 (6.32–10.84) |

| Female | 7 | 76.53 (72.46–80.61) | 9 | 9.88 (6.10–13.67) |

| Male | 7 | 74.96 (70.92–78.99) | 9 | 8.86 (5.50–12.23) |

| Substance use disorder | ||||

| Overall | 14 | 57.07 (54.47–59.67) | 33 | 20.38 (18.65–22.11) |

| Female | 8 | 59.56 (55.72–63.40) | 13 | 18.37 (16.20–20.54) |

| Male | 9 | 53.70 (49.93–57.46) | 16 | 18.62 (16.54–20.69) |

| Severe mental illness | ||||

| Overall | 30 | 65.10 (63.79–66.42) | 56 | 14.22 (13.23–15.21) |

| Female | 28 | 69.07 (67.54–70.59) | 38 | 12.83 (11.54–14.12) |

| Male | 28 | 61.84 (60.19–63.49) | 39 | 14.43 (12.92–15.95) |

| Schizophrenia-spectrum disorders | ||||

| Overall | 25 | 63.70 (62.13–65.27) | 46 | 15.37 (14.18–16.55) |

| Female | 22 | 68.15 (66.31–69.99) | 31 | 13.87 (12.38–15.36) |

| Male | 22 | 60.92 (59.02–62.82) | 32 | 15.84 (14.01–17.67) |

| Schizophrenia | ||||

| Overall | 19 | 63.66 (61.48–65.84) | 31 | 15.22 (13.8–16.65) |

| Female | 15 | 69.22 (66.81–71.64) | 22 | 13.11 (11.29–14.93) |

| Male | 15 | 61.69 (59.32–64.06) | 22 | 14.96 (13.33–16.59) |

| Mood disorders | ||||

| Overall | 22 | 64.03 (61.99–66.07) | 39 | 12.79 (11.58–14.00) |

| Female | 20 | 68.99 (66.71–71.27) | 24 | 10.63 (9.52–11.74) |

| Male | 20 | 61.12 (58.59–63.65) | 25 | 12.77 (11.52–14.03) |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Overall | 11 | 67.30 (65.29–69.31) | 21 | 12.47 (10.93–14.01) |

| Female | 10 | 70.57 (68.75–72.39) | 12 | 11.29 (10.10–12.48) |

| Male | 10 | 64.80 (62.17–67.44) | 13 | 11.63 (9.66–13.60) |

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Overall | 10 | 61.94 (57.88–66.00) | 17 | 12.80 (11.12–14.48) |

| Female | 9 | 67.34 (61.98–72.72) | 11 | 10.68 (8.49–12.88) |

| Male | 9 | 58.95 (53.24–64.65) | 12 | 13.45 (11.33–15.57) |

| Neurotic disorders | ||||

| Overall | 4 | 69.51 (67.26–71.76) | 11 | 8.83 (7.55–10.11) |

| Female | 4 | 73.56 (70.80–76.31) | 7 | 7.88 (5.22–10.54) |

| Male | 4 | 64.70 (63.29–66.11) | 7 | 10.26 (8.51–12.02) |

| Eating disorders | ||||

| Overall | NA | NA | 6 | 16.64 (7.45–25.82) |

| Personality disorders | ||||

| Overall | 4 | 63.51 (60.47–66.55) | 11 | 15.35 (12.80–17.89) |

| Female | 4 | 66.90 (63.20–70.60) | 7 | 13.30 (10.47–16.13) |

| Male | 4 | 60.12 (57.05–63.19) | 7 | 15.52 (12.79–18.25) |

| Developmental disorders | ||||

| Overall | NA | NA | 5 | 12.72 (4.50–20.94) |

| Behavioural disorders | ||||

| Overall | NA | NA | 4 | 8.54 (7.73–9.34) |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence intervals; NA: not available; YPLL: years of potential life lost.

Fig. 2.

Overall life expectancy of people with specific mental disorder types. Life expectancy of people with mental disorders in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America and South America is labelled by colour.

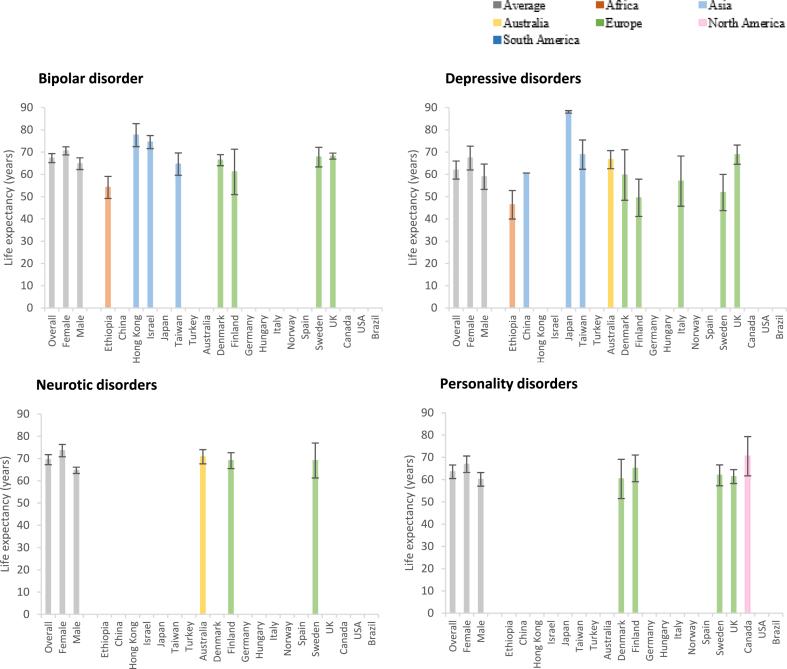

Fig. 3.

Life expectancy and years of potential life lost (YPLL) of people with mental disorders before 2001, in 2001–2010, and after 2010. Any: any mental disorders; BD: bipolar disorder; ED: eating disorders; PD: personality disorders; SCZ: schizophrenia; SMI: severe mental illness; SSD: schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (Study period is labelled by colour).

Meta-regression of life expectancy

Univariate meta-regression analyses revealed that the life expectancy estimate for any mental disorders was significantly associated with sex (Qm = 54.0, p < 0.0001), source of study samples (Qm = 14.5, p = 0.0018), geographic region in continents (Qm = 22.4, p < 0.0001) and study period (Qm = 38.2, p < 0.0001), but not follow-up duration (Qm = 1.5, p = 0.47), method of case ascertainment (Qm = 0.5, p = 0.79), or diagnostic system (Qm = 0.1, p = 0.74). A multivariable meta-regression model accounting for all potential moderators explained 49.3% of the variance (Qm = 203.8, p < 0.0001), indicating that there was residual variance due to unaccounted heterogeneity in life expectancy estimates.

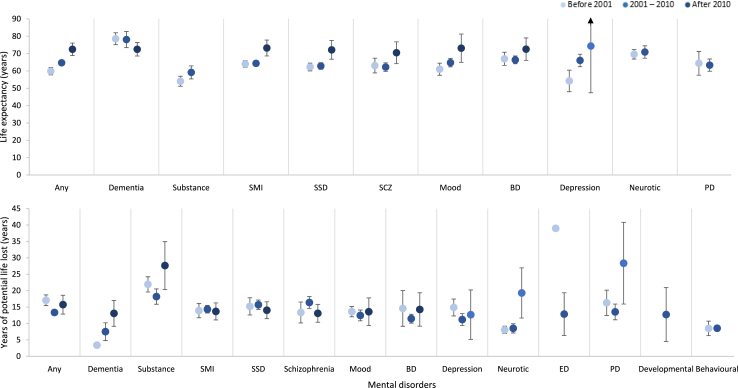

Meta-analysis and subgroup analyses of years of potential life lost (YPLL)

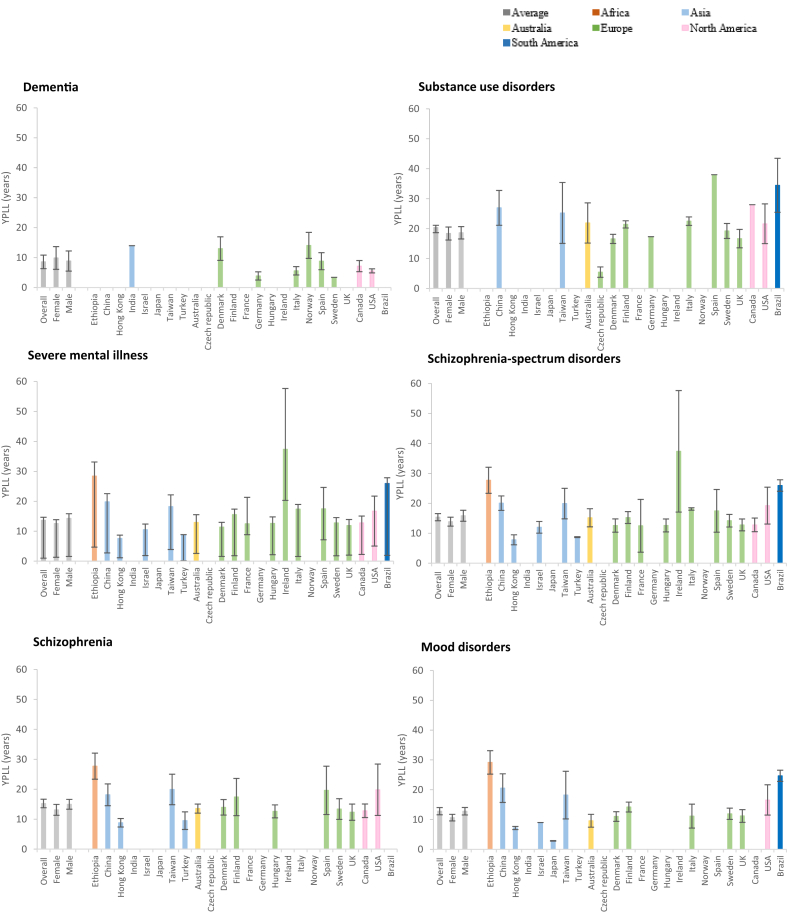

The pooled YPLL estimate of individuals with any mental disorders was 14.66 years (95% CI 13.88–15.45, I2 = 100.0%; Table 1, Supplementary Table S11). A greater YPLL was observed in males with mental disorders (14.73 years [13.64–15.82], I2 = 100.0%) than their female counterparts (12.83 years [11.85–13.82], I2 = 100.0%). The pooled YPLL based on mean-age-at-death approach was 19.09 years (17.05–21.14), which was greater than the synthesized estimate of studies utilising a life-expectancy approach (13.27 years [12.58–13.96]; Supplementary Table S8). Comparable YPLL estimates were demonstrated in subgroup analyses stratified by source of study samples, length of follow-up, method of case ascertainment, diagnostic system, and type of reference population to derive YPLL (Supplementary Table S8). Concerning specific types of mental disorders (Table 1, Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S11), YPLL was greatest in substance use disorders (20.38 years [18.65–22.11], I2 = 100.0%), followed by eating disorders (16.64 years [7.45–25.82], I2 = 100.0%), schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (15.37 years [14.18–16.55], I2 = 100.0%), and personality disorders (15.35 years [12.80–17.89], I2 = 100.0%). This was followed by YPLLs for depressive disorders (12.80 years [11.12–14.48], I2 = 100.0%), developmental disorders (12.72 years [4.50–20.94], I2 = 99.5%) and bipolar disorder (12.47 years [10.93–14.01], I2 = 100.0%). Patients with neurotic disorders (8.83 years [7.55–10.11], I2 = 100.0%), dementia (8.58 years [6.32–10.84], I2 = 100.0%), and behavioural disorders (8.54 years [7.73–9.34], I2 = 83.6%) reported comparatively fewer YPLL. Subgroup analyses for each specific mental disorder stratified by approach for YPLL estimation are presented in the Supplementary Table S11.

Fig. 4.

Years of potential life lost (YPLL) of people with specific mental disorder types. YPLL of people with mental disorders in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America and South America is labelled by colour.

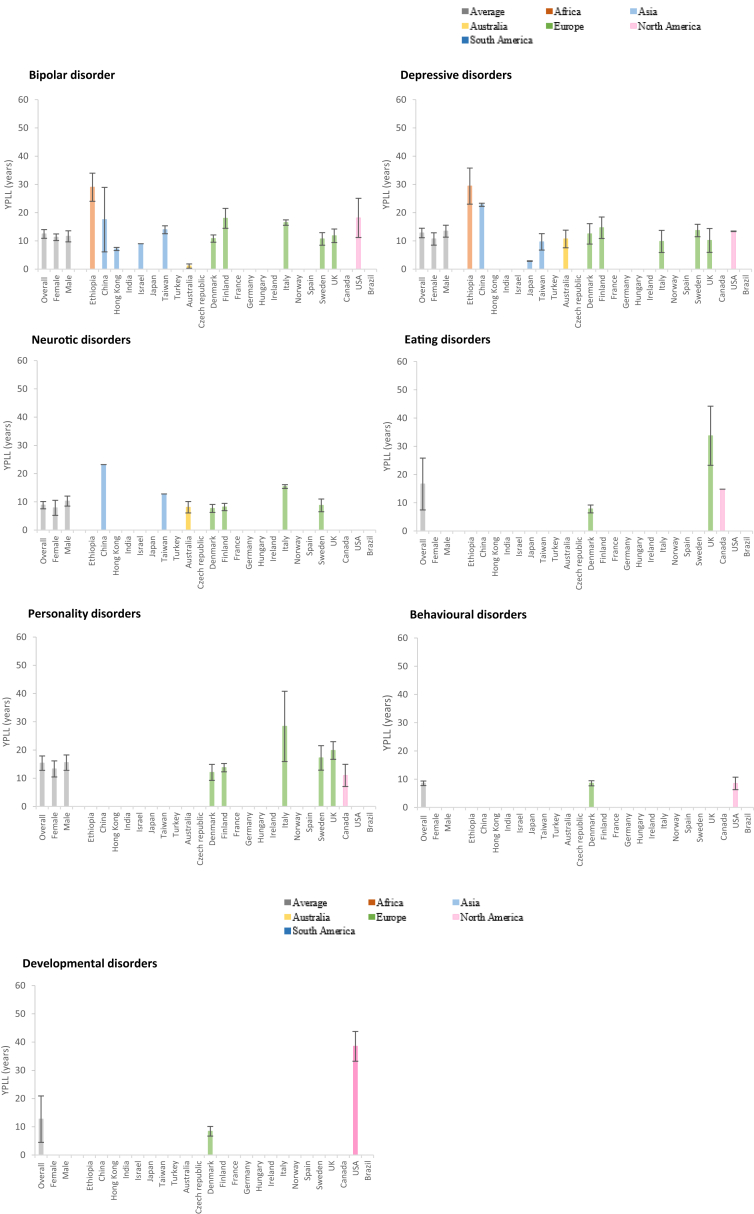

Subgroup analyses stratified by geographic region (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S12; for countries/regions, see the Supplementary Table S13) showed that YPLL was greatest in individuals with any mental disorders from Africa (28.40 years [23.70–33.10]) to South America (27.64 years [26.76–28.52]), whereas the other four continents showed comparable YPLL estimates (12–16 years). Regarding study period, the pooled YPLL for any mental disorders “before 2001”, within “2001–2010” and “after 2010” was 17.08 years (15.45–18.71), 13.36 years (12.51–14.21) and 15.74 years (12.87–18.60), respectively. YPLL estimates for each specific mental disorder across study periods are summarised in Fig. 3 and the Supplementary Table S12. Concerning YPLL due to specific death cause (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S14), individuals with any mental disorders displayed the greatest YPLL for unnatural causes (8.11 years [6.10–10.13]), especially suicide (8.31 years [6.43–10.19]), compared to the general population with the same death cause. The pooled natural-cause YPLL for individuals with any mental disorders relative to the general population was 4.38 years (3.15–5.61), with endocrine/metabolic diseases, digestive diseases and infectious diseases showing relatively greater YPLL estimates compared with other natural causes.

Fig. 5.

Years of potential life lost (YPLL) of people with any mental disorders relative to the general population with same deathcause.

Meta-regression of years of potential life lost (YPLL)

Univariate meta-regression analyses revealed that the YPLL estimate for any mental disorders was significantly associated with sex (Qm = 6.3, p = 0.012), source of study samples (Qm = 7.8, p = 0.049), geographic region (Qm = 17.0, p = 0.0051), study period (Qm = 18.7, p < 0.0001), follow-up duration (Qm = 8.4, p = 0.015), reference population (Qm = 14.4, p < 0.0001) and approach to derive YPLL (Qm = 46.1, p < 0.0001), but not method of case ascertainment (Qm = 0.5, p = 0.76), or diagnostic system (Qm = 1.7, p = 0.20). A multivariable meta-regression model accounting for all potential moderators explained 55.5% of the variance (Qm = 480.4, p < 0.0001), indicating the presence of residual variance due to unaccounted heterogeneity in YPLL estimates.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis examining life expectancy and YPLL in people with mental disorders across a broad spectrum of diagnoses. Results included 109 studies that were conducted in 24 countries/regions. Our main analyses showed that people with any mental disorders experienced reduced life expectancy relative to the general population, with 14.7 years of potential life lost. Our findings concur with two previous meta-analyses on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,11,13 demonstrating 12–15 years shorter lifespan in patients with these two disorders, and further indicate that the longevity gap applies to a wide variety of mental disorders rather than only to severe mental illness. In keeping with an earlier meta-analysis showing that substance use disorders had the highest mortality-ratio across various mental disorders,3 our disorder-stratified analyses revealed that substance use disorders were associated with the largest life expectancy gap relative to the general population, with a YPLL of approximately 20 years. We also observed that other rarer or less-researched conditions, including eating disorders, personality disorders and developmental disorders, are related to approximately 16–12 years of reduced lifespan, similar to severe mental illness. This finding echoes accumulating data suggesting markedly elevated risk of excess mortality in these disorders,126, 127, 128 especially people with eating disorders and personality disorders who were found to have 5–6 times higher in mortality-ratio than the general population.126,127 Conversely, dementia was associated with the longest lifespan and fewest YPLL. This is an expected finding and is not directly comparable to the results of other mental disorders since dementia, primarily develops in old age. Depressive disorders, neurotic disorders and behavioural disorders showed relatively shorter YPLL, but are among the most common mental disorders. Clearly, it is of equal importance to adequately address less common but more severe disorders as well as more prevalent but apparently milder conditions in order to successfully reduce the premature mortality burden for mental disorders.

Our sex-stratified analyses showed that life expectancy was significantly lower in men with mental disorders than in women with mental disorders, with also significantly greater YPLL for men than for women. Regional differences are also noted in life expectancy and YPLL. Patients with mental disorders from Africa and South America exhibited the shortest lifespan and greatest longevity gap relative to those from other continents (Asia, Australia, Europe and North America), which had largely comparable life expectancy and YPLL estimates. Our findings on life expectancy might partly reflect cross-regional differences in the distribution of life expectancy in the general population,129 particularly in Africa. Differences in access to and quality of healthcare services and lifestyle factors might also contribute to the variations in life expectancy across regions.130 In this regard, regional variations in YPLL, which denotes lifespan differences between patients and the general population, would yield more informative cross-regional comparisons. Notably, as data from continents other than Europe and North America were represented by fewer studies, our results on regional differences should therefore be interpreted with caution.

People with mental disorders displayed an increased lifespan from the period of “before 2001 to “after 2010” (from 58.86 years to 73.75 years). In particular, patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders demonstrated a significant increase in life expectancy from the period of “2001–2010” to “after 2010”. This finding suggests that an improvement in mental healthcare in general as well as the development of new treatment strategies over the recent decades, such as early psychosis intervention services,131,132 may help reduce the excess mortality associated with mental disorders. However, the substantially overlapping 95% CIs around YPLL estimates in the analyses stratified by study period (i.e., between “before 2001” and “after 2010, and between “2001–2010” and “after 2010”) suggest that the longevity gap between people with mental disorders and the general population did not narrow over time. Similarly, the life expectancy gap generally persisted across study periods for most specific mental disorders, except eating disorders which demonstrated a markedly deceased YPLL over time (but only one study was included in the period “before 2001”). A pooled analysis evaluating differential mortality using mortality-risk-ratios even reported a widening mortality gap between mental disorders and the general population in recent decades. Overall, patients with mental disorders still experience substantial physical health disparities and have not benefited equally from enhanced healthcare and life expectancy improvement compared to the general population.

Subgroup analyses on YPLL stratified by death cause showed that more years of life were lost to unnatural causes, in particular suicide, than to natural causes in people with mental disorders. As life expectancy and YPLL are mortality metrics that take into account the age at death, disorders or conditions resulting in mortality at younger age (e.g., suicide) would exert a greater impact on life expectancy/YPLL estimates. Additionally, cause of death is of competing risk in nature. Unnatural-cause mortality that happens earlier in life thus precludes occurrence of chronic physical diseases (and natural-cause deaths) which are primarily associated with older age of onset. On the other hand, the literature has indicated that overall excess mortality in mental disorders is mainly attributable to natural causes.4, 5, 6 It is noteworthy that individual causes of natural death examined in this study contributed comparable YPLL for people with mental disorders, thereby suggesting that such longevity gap might be due to a wider range of physical diseases rather than a few predominant conditions. Our findings highlight the need for effective strategies to address both natural and unnatural causes for prevention of avoidable premature mortality associated with mental disorders.

Although life expectancy and YPLL are regarded as easier-to-interpret measures of premature mortality compared to a relative risk and are increasingly applied in psychiatric research, they are associated with important methodological constraints that merit attention. Life expectancy of a cohort (i.e., people with mental disorders in our context) is calculated based on mortality during a study period, rather than by following a cohort from birth to death for every participant, by applying age-specific mortality rates for all age groups to accumulate the person-years contributed within the study period, which is then weighted by the total number of participants in the cohort.133,134 This methodological approach assumes that these age-specific mortality rates will remain unchanged throughout the lifetime of future people with mental disorders. As such, the estimation of life expectancy and YPLL would be particularly misleading in the context of small cohort size or short follow-up period.133,134 Of note, the majority of the included studies in our meta-analysis estimated life expectancy at birth. However, as most mental disorders cannot manifest and be diagnosed before a certain age, the mortality rates of people with a mental disorder below the specified earliest possible age at onset (pre-defined by the studies) for that particular mental disorder were substituted by those mortality rates of the general population for the calculation of life expectancy. It is also important to note that YPLL quantified the impact of premature mortality on survival based on estimating life expectancy at a single fixed-age. Our subgroup analyses revealed that the magnitude of YPLL for mental disorders was influenced by the set-age for lifespan calculation, with YPLL estimates decreasing with increasing set-age. However, recent research has indicated that life-years lost (LYL), a novel metric taking into account age-of-onset distribution of disorders,98,135 would yield a more precise estimate of life expectancy reduction.98 Future studies should therefore consider adopting the LYL method for more accurate estimations of shortened lifespan in people with mental disorders.

Factors contributing to excess mortality in people with mental disorders are multifold and intertwined,9,10 and hence adoption of multilevel prevention and intervention framework managing risk factors at the individual, health-system and socio-environmental levels is warranted to achieve health outcomes improvement.136 Individual-level strategies targeting people with mental disorders include optimising management of mental disorders, early detection and equitable treatment of physical morbidity,16,137 lifestyle interventions addressing modifiable risk factors, such as regular exercise, smoking cessation and weight reduction.138 Health system-focused interventions implemented within healthcare services comprise regular, guideline-concordant monitoring of medication-induced metabolic side-effects,139 and facilitation of coordinated psychiatric and physical healthcare delivery. Strategies targeting socio-environmental determinants represent the broadest level of intervention through addressing community-related contributors to differential mortality in people with mental disorders, for instance, reduction of mental health stigma and discrimination,140 which is associated with delayed help-seeking and poor illness outcome. In addition, development of risk prediction algorithms specific to certain mental-disorder populations (e.g., severe mental illness) for cardiometabolic diseases141 and suicidal behaviours142 would facilitate identification of patients at high-risk for adverse health outcomes and provision of personalised interventions to minimise excess mortality.

Several limitations warrant consideration in interpreting the study results. First, there was significant heterogeneity across studies for life expectancy and YPLL (as often is the case in meta-analyses of large-scale observational studies),143 and meta-regression analyses indicated that such heterogeneity could not be fully accounted for by the pre-specified study characteristics, indicating the presence of other unidentified factors. However, as data for other potentially relevant variables, such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle risk factors and prescribed psychotropic medications, were not reported in most included studies, sources of heterogeneity could not be further explored. These factors should be reported regularly and as comprehensively as possible in future studies to be able to account for them in future meta-analyses. Second, similar to previous meta-analyses,11,13 as many included studies on life expectancy and YPLL did not report measures of uncertainty, we extrapolated the pooled SE from the fixed-effect models from these studies to derive 95% CIs of our summary estimates. This procedure might have affected the accuracy of the true variance, which may in turn have accentuated the level of heterogeneity. Third, findings of some subgroup analyses (e.g., several specific mental disorders and geographic groups) were based on few studies, and should be re-evaluated when more studies are conducted in this respect. Fourth, only few studies have examined YPLL for specific death causes in individual mental disorders, thus we were not able to generate pooled estimates of cause-specific YPLL for specific mental disorders. Fifth, although the majority of the meta-analysed studies based their calculations on one principal psychiatric diagnosis per patient, some allowed patients to contribute to more than one disorder in their analyses. While this approach could have affected the results, it is also reflective of the fact that psychiatric comorbidities are highly prevalent among people with mental disorders.144 Nevertheless, since available studies examining life expectancy and YPLL for mental disorders rarely took into consideration co-existing conditions, the effect of physical and psychiatric multimorbidity, which is common and important,96,145 could not be assessed. Notwithstanding these limitations, this first comprehensive meta-analysis of life expectancy and YPLL across a wide range of mental disorders provides relevant and actionable targets for clinicians and allied-health professionals, researchers, healthcare system administrators, and policy makers that can be leveraged to help close the serious mortality gap in people with mental disorders.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis indicates that people with mental disorders exhibit substantially reduced life expectancy, with 14.7 years of life lost relative to the general population. Such life expectancy gap in mental disorders is transdiagnostic in nature, and substance use disorders have the greatest reduction in lifespan, followed by eating disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and personality disorders. Unnatural-cause deaths, particularly suicide, are related to a significantly greater YPLL than natural-cause mortality, whereas various specific natural causes contribute comparably to the longevity gap associated with mental disorders. Comprehensive and multipronged preventive and interventional approaches are urgently needed to effectively promote physical health and lower suicide risk in people with mental disorders, with consequent reduction of premature mortality and normalisation of the observed lifespan inequality.

Contributors

WCC and JKNC conceptualized and proposed the topic. JKNC, WCC, CUC, and CSMW developed the protocol, designed the search strategy, and defined the inclusion criteria. RSTC, VSCF, GHSW, and JHCL screened the literature search. JKNC and VSCF extracted data from included studies. JKNC and RSTC did the quality assessment of included studies. JKNC did the statistical analyses. JKNC, WCC, CUC, and CSMW analysed and interpreted the data. JKNC, WCC, and CSMW had access to and verified the data. JKNC wrote the first draft. WCC made critical revisions with input from CUC. WCC and CUC finalised the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the report for important intellectual content and approved the final submitted version. WCC, JKNC, CUC, and CSMW had full access to the study data and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All other co-authors were not precluded from accessing data in the study and they approved submission for publication.

Data sharing statement

This meta-analysis used extracted data from published studies. The dataset and the analytic codes used in this study can be made available from the corresponding author with publication upon reasonable request by researchers who provide a justified hypothesis.

Declaration of interests

CUC has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Aristo, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cardio Diagnostics, Cerevel, CNX Therapeutics, Compass Pathways, Darnitsa, Denovo, Gedeon Richter, Hikma, Holmusk, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, MedInCell, Merck, Mindpax, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Neurocrine, Neurelis, Newron, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Pharmabrain, PPD Biotech, Recordati, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Seqirus, SK Life Science, Sunovion, Sun Pharma, Supernus, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris. He provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Compass Pathways, Denovo, Lundbeck, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Sage, Supernus, Tolmar, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He received royalties from UpToDate and is also a stock option holder of Cardio Diagnostics, Mindpax, LB Pharma, PsiloSterics, and Quantic. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jacky On Hei Cheung, Antonius Tam Siu Kwan, Charlotte Nok Yee Ma, Justina Hiu Wai Chay, and Flora Sha Zhao for their assistance in literature review. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this Article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102294.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vigo D., Thornicroft G., Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesney E., Goodwin G.M., Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):153–160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker E.R., McGee R.E., Druss B.G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plana-Ripoll O., Pedersen C.B., Agerbo E., et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827–1835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correll C.U., Solmi M., Croatto G., et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):248–271. doi: 10.1002/wps.20994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence D., Hancock K.J., Kisely S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population-based registers. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erlangsen A., Andersen P.K., Toender A., Laursen T.M., Nordentoft M., Canudas-Romo V. Cause-specific life-years lost in people with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(12):937–945. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firth J., Siddiqi N., Koyanagi A., et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(8):675–712. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connor R.C., Worthman C.M., Abanga M., et al. Gone to soon: priorities for action to prevent premature mortality associated with mental illness and mental distress. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10(6):452–464. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjorthøj C., Stürup A.E., McGrath J.J., Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):295–301. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Y.J., Yeh L.L., Chan H.Y., Chang C.K. Excess mortality and shortened life expectancy in people with major mental illnesses in Taiwan. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29 doi: 10.1017/S2045796020000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan J.K.N., Tong C.H.Y., Wong C.S.M., Chen E.Y.H., Chang W.C. Life expectancy and years of potential life lost in bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;221(3):567–576. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2022.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells G.A., Shea B., O’Connell D., et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2009. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solmi M., Firth J., Miola A., et al. Disparities in cancer screening in people with mental illness across the world versus the general population: prevalence and comparative meta-analysis including 4 717 839 people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(1):52–63. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furukawa T.A., Barbui C., Cipriani A., Brambilla P., Watanabe N. Imputing missing standard deviations in meta-analyses can provide accurate results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinozaki H. An epidemiologic study of deaths of psychiatric inpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 1976;17(3):425–436. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(76)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman S.C., Bland R.C. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36(4):239–245. doi: 10.1177/070674379103600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poser W., Poser S., Eva-Condemarin P. Mortality in patients with dependence on prescription drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1992;30(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(92)90035-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall E.J., Edwards G., Taylor C. Mortality in men with drinking problems: a 20-year follow-up. Addiction. 1994;89(10):1293–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dembling B.P., Chen D.T., Vachon L. Life expectancy and causes of death in a population treated for serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1036–1042. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.8.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannerz H., Borgå P. Mortality among persons with a history as psychiatric inpatients with functional psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35(8):380–387. doi: 10.1007/s001270050254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannerz H., Borgå P., Borritz M. Life expectancies for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. Public Health. 2001;115(5):328–337. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodge H.H., Shen C., Pandav R., DeKosky S.T., Ganguli M. Functional transitions and active life expectancy associated with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(2):253–259. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickey B., Dembling B., Azeni H., Normand S.L. Externally caused deaths for adults with substance use and mental disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31(1):75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02287340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brugal M.T., Domingo-Salvany A., Puig R., Barrio G., García de Olalla P., de la Fuente L. Evaluating the impact of methadone maintenance programmes on mortality due to overdose and aids in a cohort of heroin users in Spain. Addiction. 2005;100(7):981–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colton C.W., Manderscheid R.W. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller B.J., Paschall C.B., 3rd, Svendsen D.P. Mortality and medical comorbidity among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1482–1487. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smyth B., Fan J., Hser Y.I. Life expectancy and productivity loss among narcotics addicts thirty-three years after index treatment. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(4):37–47. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller C.L., Kerr T., Strathdee S.A., Li K., Wood E. Factors associated with premature mortality among young injection drug users in Vancouver. Harm Reduct J. 2007;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smyth B., Hoffman V., Fan J., Hser Y.I. Years of potential life lost among heroin addicts 33 years after treatment. Prev Med. 2007;44(4):369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haver B., Gjestad R., Lindberg S., Franck J. Mortality risk up to 25 years after initiation of treatment among 420 Swedish women with alcohol addiction. Addiction. 2009;104(3):413–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiroeh U., Kapur N., Webb R., Dunn G., Mortensen P.B., Appleby L. Deaths from natural causes in people with mental illness: a cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(3):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tiihonen J., Lönnqvist J., Wahlbeck K., et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study) Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620–627. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiviniemi M., Suvisaari J., Pirkola S., Häkkinen U., Isohanni M., Hakko H. Regional differences in five-year mortality after a first episode of schizophrenia in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(3):272–279. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piatt E.E., Munetz M.R., Ritter C. An examination of premature mortality among decedents with serious mental illness and those in the general population. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(7):663–668. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang C.K., Hayes R.D., Perera G., et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS One. 2011;6(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Druss B.G., Zhao L., Von Esenwein S., Morrato E.H., Marcus S.C. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayes R.D., Chang C.K., Fernandes A., et al. Associations between substance use disorder sub-groups, life expectancy and all-cause mortality in a large British specialist mental healthcare service. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118(1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laursen T.M. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1–3):101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahlbeck K., Westman J., Nordentoft M., Gissler M., Laursen T.M. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):453–458. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fok M.L., Hayes R.D., Chang C.K., Stewart R., Callard F.J., Moran P. Life expectancy at birth and all-cause mortality among people with personality disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(2):104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Healy D., Le Noury J., Harris M., et al. Mortality in schizophrenia and related psychoses: data from two cohorts, 1875-1924 and 1994-2010. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kodesh A., Goldshtein I., Gelkopf M., Goren I., Chodick G., Shalev V. Epidemiology and comorbidity of severe mental illnesses in the community: findings from a computerized mental health registry in a large Israeli health organization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(11):1775–1782. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morden N.E., Lai Z., Goodrich D.E., et al. Eight-year trends of cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality in patients with schizophrenia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(4):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nome S., Holsten F. Changes in mortality after first psychiatric admission: a 20-year prospective longitudinal clinical study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66(2):97–106. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.605170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rizzuto D., Bellocco R., Kivipelto M., Clerici F., Wimo A., Fratiglioni L. Dementia after age 75: survival in different severity stages and years of life lost. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(7):795–800. doi: 10.2174/156720512802455421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westman J., Gissler M., Wahlbeck K. Successful deinstitutionalization of mental health care: increased life expectancy among people with mental disorders in Finland. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(4):604–606. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zivin K., Ilgen M.A., Pfeiffer P.N., et al. Early mortality and years of potential life lost among Veterans Affairs patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(8):823–826. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ajetunmobi O., Taylor M., Stockton D., Wood R. Early death in those previously hospitalised for mental healthcare in Scotland: a nationwide cohort study, 1986-2010. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crump C., Winkleby M.A., Sundquist K., Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):324–333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crump C., Sundquist K., Winkleby M.A., Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: a Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):931–939. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Degenhardt L., Larney S., Randall D., Burns L., Hall W. Causes of death in a cohort treated for opioid dependence between 1985 and 2005. Addiction. 2014;109(1):90–99. doi: 10.1111/add.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ientile L., De Pasquale R., Monacelli F., et al. Survival rate in patients affected by dementia followed by memory clinics (UVA) in Italy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36(2):303–309. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laursen T.M., Wahlbeck K., Hällgren J., et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nordentoft M., Wahlbeck K., Hällgren J., et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Almeida O.P., Hankey G.J., Yeap B.B., Golledge J., Norman P.E., Flicker L. Mortality among people with severe mental disorders who reach old age: a longitudinal study of a community-representative sample of 37,892 men. PLoS One. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veldhuizen S., Callaghan R.C. Cause-specific mortality among people previously hospitalized with opioid-related conditions: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(8):620–624. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang K.C., Lu T.H., Lee K.Y., Hwang J.S., Cheng C.M., Wang J.D. Estimation of life expectancy and the expected years of life lost among heroin users in the era of opioid substitution treatment (OST) in Taiwan. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Charrel C.L., Plancke L., Genin M., et al. Mortality of people suffering from mental illness: a study of a cohort of patients hospitalised in psychiatry in the north of France. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(2):269–277. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fekadu A., Medhin G., Kebede D., et al. Excess mortality in severe mental illness: 10-year population-based cohort study in rural Ethiopia. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(4):289–296. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kessing L.V., Vradi E., McIntyre R.S., Andersen P.K. Causes of decreased life expectancy over the life span in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kessing L.V., Vradi E., Andersen P.K. Life expectancy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(5):543–548. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lesage A., Rochette L., Émond V., et al. A surveillance system to monitor excess mortality of people with mental illness in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(12):571–579. doi: 10.1177/070674371506001208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olfson M., Gerhard T., Huang C., Crystal S., Stroup T.S. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172–1181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roehr S., Luck T., Bickel H., et al. Mortality in incident dementia - results from the German study on aging, cognition, and dementia in primary care patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(4):257–269. doi: 10.1111/acps.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tom S.E., Hubbard R.A., Crane P.K., et al. Characterization of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in an older population: updated incidence and life expectancy with and without dementia. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):408–413. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Banerjee T.K., Dutta S., Das S., et al. Epidemiology of dementia and its burden in the city of Kolkata, India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(6):605–614. doi: 10.1002/gps.4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dickerson F., Origoni A., Schroeder J., et al. Mortality in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: clinical and serological predictors. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(1):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laursen T.M., Musliner K.L., Benros M.E., Vestergaard M., Munk-Olsen T. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193(3):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lêng C.H., Chou M.H., Lin S.H., Yang Y.K., Wang J.D. Estimation of life expectancy, loss-of-life expectancy, and lifetime healthcare expenditures for schizophrenia in Taiwan. Schizophr Res. 2016;171(1–3):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tam J., Warner K.E., Meza R. Smoking and the reduced life expectancy of individuals with serious mental illness. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(6):958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou Y., Putter H., Doblhammer G. Years of life lost due to lower extremity injury in association with dementia, and care need: a 6-year follow-up population-based study using a multi-state approach among German elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0184-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bitter I., Czobor P., Borsi A., et al. Mortality and the relationship of somatic comorbidities to mortality in schizophrenia. A nationwide matched-cohort study. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;45:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cailhol L., Pelletier É., Rochette L., et al. Prevalence, mortality, and health care use among patients with cluster B personality disorders clinically diagnosed in Quebec: a provincial cohort study, 2001-2012. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(5):336–342. doi: 10.1177/0706743717700818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang K.C., Wang J.D., Saxon A., Matthews A.G., Woody G., Hser Y.I. Causes of death and expected years of life lost among treated opioid-dependent individuals in the United States and Taiwan. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;43:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jayatilleke N., Hayes R.D., Dutta R., et al. Contributions of specific causes of death to lost life expectancy in severe mental illness. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;43:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.02.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Castle D.J., Chung E. Cardiometabolic comorbidities and life expectancy in people on medication for schizophrenia in Australia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(4):613–618. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1419946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dickerson F., Origoni A., Schroeder J., et al. Natural cause mortality in persons with serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(5):371–379. doi: 10.1111/acps.12880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ko Y.S., Tsai H.C., Chi M.H., et al. Higher mortality and years of potential life lost of suicide in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270(12):531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Laursen T.M., Plana-Ripoll O., Andersen P.K., et al. Cause-specific life years lost among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia: is it getting better or worse? Schizophr Res. 2019;206:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lichtenstein M.L., Fallah N., Mudge B., et al. 16-year survival of the Canadian collaborative cohort of related dementias. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45(4):367–374. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2018.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strand B.H., Knapskog A.B., Persson K., et al. Survival and years of life lost in various aetiologies of dementia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and subjective cognitive decline (SCD) in Norway. PLoS One. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barkley R.A., Fischer M. Hyperactive child syndrome and estimated life expectancy at young adult follow-up: the role of ADHD persistence and other potential predictors. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(9):907–923. doi: 10.1177/1087054718816164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith DaWalt L., Hong J., Greenberg J.S., Mailick M.R. Mortality in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: predictors over a 20-year period. Autism. 2019;23(7):1732–1739. doi: 10.1177/1362361319827412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Doyle R., O'Keeffe D., Hannigan A., et al. The iHOPE-20 study: mortality in first episode psychosis-a 20-year follow-up of the Dublin first episode cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(11):1337–1342. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01721-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Garre-Olmo J., Ponjoan A., Inoriza J.M., et al. Survival, effect measures, and impact numbers after dementia diagnosis: a matched cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:525–542. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S213228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gerritsen A.A.J., Bakker C., Verhey F.R.J., et al. Survival and life-expectancy in a young-onset dementia cohort with six years of follow-up: the NeedYD-study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(12):1781–1789. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Strand B.H., Knapskog A.B., Persson K., et al. The loss in expectation of life due to early-onset mild cognitive impairment and early-onset dementia in Norway. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;47(4–6):355–365. doi: 10.1159/000501269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Iwajomo T., Bondy S.J., de Oliveira C., Colton P., Trottier K., Kurdyak P. Excess mortality associated with eating disorders: population-based cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;219(3):487–493. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lewer D., Jones N.R., Hickman M., Nielsen S., Degenhardt L. Life expectancy of people who are dependent on opioids: a cohort study in New South Wales, Australia. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Plana-Ripoll O., Musliner K.L., Dalsgaard S., et al. Nature and prevalence of combinations of mental disorders and their association with excess mortality in a population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):339–349. doi: 10.1002/wps.20802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang J.Y., Chang C.C., Lee M.C., Li Y.J. Identification of psychiatric patients with high mortality and low medical utilization: a population-based propensity score-matched analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05089-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weye N., Momen N.C., Christensen M.K., et al. Association of specific mental disorders with premature mortality in the Danish population using alterative measurement methods. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chan J.K.N., Wong C.S.M., Yung N.C.L., Chen E.Y.H., Chang W.C. Excess mortality and life-years lost in people with bipolar disorder: an 11-year population-based cohort study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30 doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Das-Munshi J., Chang C.K., Dregan A., et al. How do ethnicity and deprivation impact on life expectancy at birth in people with serious mental illness? Observational study in the UK. Psychol Med. 2021;51(15):2581–2589. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]