Abstract

Traditionally, patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) seen in EDs have been medically cleared, discharged, and left to navigate a complex treatment system after discharge. Replacing this system of care requires reimagining the ED visit to promote best practices, including starting treatment with lifesaving medications for OUD in the ED. In this article, the authors present stakeholder-informed design of strategies for implementation of evidence-based ED OUD care at Penn Medicine. They used a participatory design approach to incorporate insights from diverse clinician groups in an iterative fashion to develop new processes of care that identified patients early to initiate OUD care pathways. Their design process led to the development of a nurse-driven protocol with OUD screening in ED triage coupled with automated prompts to both nurses and physicians or advanced practice providers to perform assessment and treatment of OUD and to deliver evidence-based treatment interventions.

The Challenge

The United States faces a crisis of opioid use disorder (OUD) and overdose, and drivers have only accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic.1–3 Medications for OUD (MOUDs) like buprenorphine and methadone reduce overdose and all-cause mortality and improve a host of other patient outcomes, from treatment retention to quality of life.4,5 Acute care settings are critical touchpoints for OUD treatment initiation.6 Many patients with OUD — particularly those disconnected from other medical care — present to EDs and hospitals with overdose, seeking OUD treatment, or other medical needs. Importantly, there is strong evidence that initiating buprenorphine treatment in the ED more than doubles engagement in treatment at 30 days compared with referral alone.7 Despite the strength of the evidence, uptake has been mixed at Penn Medicine and across the country.8 Traditional approaches — in which patients with OUD are treated for other acute issues, medically cleared, discharged, and left to navigate a complex treatment system on their own — must be replaced with strategies to initiate treatment in the ED.

Penn Medicine EDs are located in Philadelphia, where annual overdose deaths have tripled in the past 10 years to exceed 1,200.9 Before we started our ED triage redesign, Penn Medicine had already implemented initiatives to increase ED clinician readiness and ability to treat OUD, including incentives for DATA waiver training (Drug Addiction Training Act 2020) to prescribe buprenorphine,10 clinical pathways consistent with ED OUD treatment recommendations and national guidelines,11,12 order sets in the electronic health record (EHR), and peer recovery specialists to facilitate patient engagement and linkage to care. Even with these supports, there was substantial variability in MOUD use among ED clinicians, suggesting opportunities for further improvement. EHR strategies have been successful in prior initiatives in our ED,13 and we hoped to leverage the EHR to prompt treatment and reduce variability. However, in a busy ED with many competing priorities, we needed to ensure that any strategy would be feasible, acceptable, and appropriate from the perspective stakeholders. We had research grant funding to jumpstart the process but wanted to develop and implement an intervention that would be sustainable beyond the grant period.

The Goal

Our goal was to engage interprofessional stakeholders to understand barriers to and facilitators of OUD treatment initiation and to use a participatory design approach to reimagine processes of care to make evidence-based treatment the default.

The Execution

The execution of this effort involved several components: planning, formative work, stakeholder feedback, and refined design.

Planning

Prior work suggested that ED clinicians felt uncomfortable with OUD management and desired EHR supports to facilitate treatment.14 We also wanted to leverage behavioral economics principles to use choice architecture — the deliberate organization of information to influence decision-making — to nudge clinicians toward performing the desired behaviors and to reduce friction in doing so.15,16 By making the evidence-based choice the easy choice, we hoped to increase the use of lifesaving treatment.

“Knowing a patient had OUD aided in triage decisions and timely use of MOUDs, especially for patients in opioid withdrawal. Overall, clinicians favored universal screening in triage if it were streamlined, actionable, and nondisruptive.”

ED care for OUD involves multiple steps, which vary on the basis of patients’ clinical presentation and readiness for treatment. Steps include: (1) identification of OUD; (2) assessment for opioid withdrawal; (3) treatment initiation in the ED for patient in withdrawal and/or providing treatment at discharge; and (4) linking to follow-up care. Our strategy was to start with identification and then tailor subsequent care pathways to promote evidence-based treatment.

Formative Work

In September 2019, we considered several potential strategies for identifying patients and prompting treatment, each of which has tradeoffs and may be applied at different points during an encounter. There is a nascent literature on EHR-based clinical decision support for ED initiation of buprenorphine, including an ongoing pragmatic trial of one clinical decision support tool, but this work has largely focused on management of OUD once identified rather than on identifying appropriate patients early in their ED stay.17,18 EHR-based clinical decision support tools are generally underused for identification and treatment of OUD,19 and experts have called for improvements in these modalities, as highlighted in a recent working group from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.20

On the basis of initial contextual inquiry and existing literature,14,21 we generated a series of prototypes to show stakeholders during focus groups. Prototypes for identification included universal screening at registration or triage, use of existing EHR data to trigger prompts, or methods to indirectly encourage patient self-identification, such as an electronic or paper questionnaire. Prototypes to prompt treatment included a pop-up best practice alert (BPA) in the EHR that would deploy at one or more points during a patient visit, a noninterruptive banner that would remain at the top of the patient chart, or a secure text message alert to notify clinicians of appropriate patients outside of the EHR.

Stakeholder Feedback

We conducted a series of five focus groups with 29 clinicians in two EDs, including attending physicians (n 5 9), resident physicians (n 5 10), and nurses (n 5 10). Focus groups lasted approximately 1 hour and were conducted from January to April 2020 by experienced clinician researchers unknown to participants. We queried stakeholders about: (1) general preferences for identification and treatment of patients with OUD; (2) preferences about when and where identification and treatment should occur in the ED visit; and (3) feedback on the above prototypes. Two research assistants coded focus group transcripts using qualitative analysis software (Dedoose).22 We then analyzed focus group transcripts using thematic content analysis guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)23 adapted to evaluate care delivery transformation in a learning health system context.24 CFIR provides a structure to explore the determinants of successful implementation at different levels: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals involved in implementation, and implementation process. Other authors have expanded on the CFIR framework in the context of a learning health system to include patient needs and resources as a key additional domain for delivery transformation.24 After applying the original CFIR domains as well as patient needs and resources to inform our content analysis, the research team reviewed the major themes, yielding the following insights to guide strategy design, including early identification and treatment, leveraging team members, and tailored prompts.

Early Identification and Treatment

Clinicians perceived that early identification and treatment of patients with OUD improved care quality and patient experience (Table 1). Knowing a patient had OUD aided in triage decisions and timely use of MOUDs, especially for patients experiencing opioid withdrawal. Overall, clinicians favored universal screening in triage if it were streamlined, actionable, and nondisruptive. Some participants cautioned about the possibility that patients could face biased or negative reactions if they disclosed a stigmatized condition.

Table 1.

Focus Group Insights Chart: Early Identification and Treatment

| Representative quote | Insight |

|---|---|

| If you were going to ask a question, it would just be like, ‘Do you use any opioids?’… And that would actually be relevant in a lot of clinical situations, more so than whether or not they have homicidal ideation. (Physician) | Knowledge of opioid use impacts subsequent clinical decision-making |

| I think trying to do a COWS score in triage, it can help you set your ESI for a patient. (Nurse) | Identification in triage allows for early assessment and appropriate triage |

| The only thing I would say is if you could make it one click, just like we do for everything else. (Nurse) | Processes need to be simple and mirror existing triage practices |

| It may in fact engender bias on the front end; [that] is the other piece Id be concerned about, because the reality is that we’re still working down the slope of bias from where we’ve been historically with opioid addiction. (Physician) | Need for sensitivity to patients with stigmatized conditions |

COWS = clinical opiate withdrawal scale, ESI 5 = emergency severity index. Source: The authors

Leveraging Team Members

Another key insight from focus groups was the importance of leveraging interdisciplinary team members (Table 2). All clinician groups supported empowering nurses to take an active role in identifying patients and initiating treatment pathways, as well as involving peer recovery specialists early to promote engagement and discharge planning. Physicians and nurses also agreed that once patients were identified, EHR tools could be used to help standardize the processes of care and promote treatment and harm-reduction interventions.

Table 2.

Focus Group Insights Chart: Leveraging Team Members

| Representative quote | Insight |

|---|---|

| I was doing COWS on my own when I first started and was basically told that … I needed to wait to see if the provider was going to address it. So now I kind of say, ‘Hey, you want to do a COWS score? ’ … they typically say yes, but I just make sure that they ‘re on board with it. (Nurse) | Nurses are willing and able to initiate treatment pathways |

| I think [we should be] empowering the nurse even to go further and actually call the peer recovery specialist … I cannot imagine a scenario where I would be upset as a provider to learn that that step had been taken. (Physician) | Physicians want to empower nurses to play a more active role in initiating treatment pathways |

| A challenge I’ve seen is that the [OUD treatment] protocol is not used a lot and there’s a lot of steps, and knowledge gaps can affect whether or not those steps are done. (Nurse) | Need to standardize treatment pathways and reduce variability |

| [Screening in triage] would be most effective for me ifit included a page to the peer specialist team … bypassing me would be helpful, because then they could potentially even talk to the patient before me even having to really be involved. (Physician) | Importance of engaging nonclinician team members early in the process |

COWS = clinical opiate withdrawal scale, OUD = opioid use disorder. Source: The authors

Tailored Prompts

Finally, we learned that physicians and nurses differed in their preferences for prompting treatment (Table 3). In addition to desiring greater autonomy in initiating care, nurses favored guidance from BPAs in the EHR to drive specific interventions. The presence of alerts that populated nursing task lists was felt to be actionable and most consistent with other nursing workflows. In contrast, physicians preferred care to be driven by nonphysician team members and wanted any reminders or decision support to be noninterruptive, such as a banner providing clinical guidance rather than a BPA, which they felt contributes to alert fatigue.

Table 3.

Focus Group Insights Chart: Tailored Prompts

| Representative quote | Insight |

|---|---|

| A best practice alert [BPA] would have to “come with confetti” in order to be noticed among the numerous alerts that physicians already receive. (Physician) | Physicians disliked pop-ups because of alert fatigue |

| I like the banner because it puts the phone number in front of me versus me having to look it up elsewhere … as long as I don’t have to click something to get it out of the way, I think that’s great. (Physician) | Physicians favored noninterruptive design for prompts |

| This banner is helpful, but it’s not as actionable as a BPA or as a task on the list if it was orderdd. | Nursing workflow more reliant on tasks and alerts |

| I know a lot of people, I think, rely on this task list on the left. And so, if it’ s there, people remember to do it. They don ’ t click it off until it’s done. | EHR task list organizes numerous clinical activities for nursing |

EHR = electronic health record. Source: The authors

Refined Design

On the basis of stakeholder input, from July 2020–February 2021, we created a refined workflow to accomplish our goals of engaging multidisciplinary clinicians in identifying and treating OUD. At the outset, we conceptualized a process using data from the EHR to trigger an automated alert to identify patients and trigger BPAs for physicians, but we found that EHR data were neither sensitive nor specific and frequently missed patients without previous OUD-related visits or with presentations that were not obviously OUD related (e.g., nausea and vomiting from opioid withdrawal).

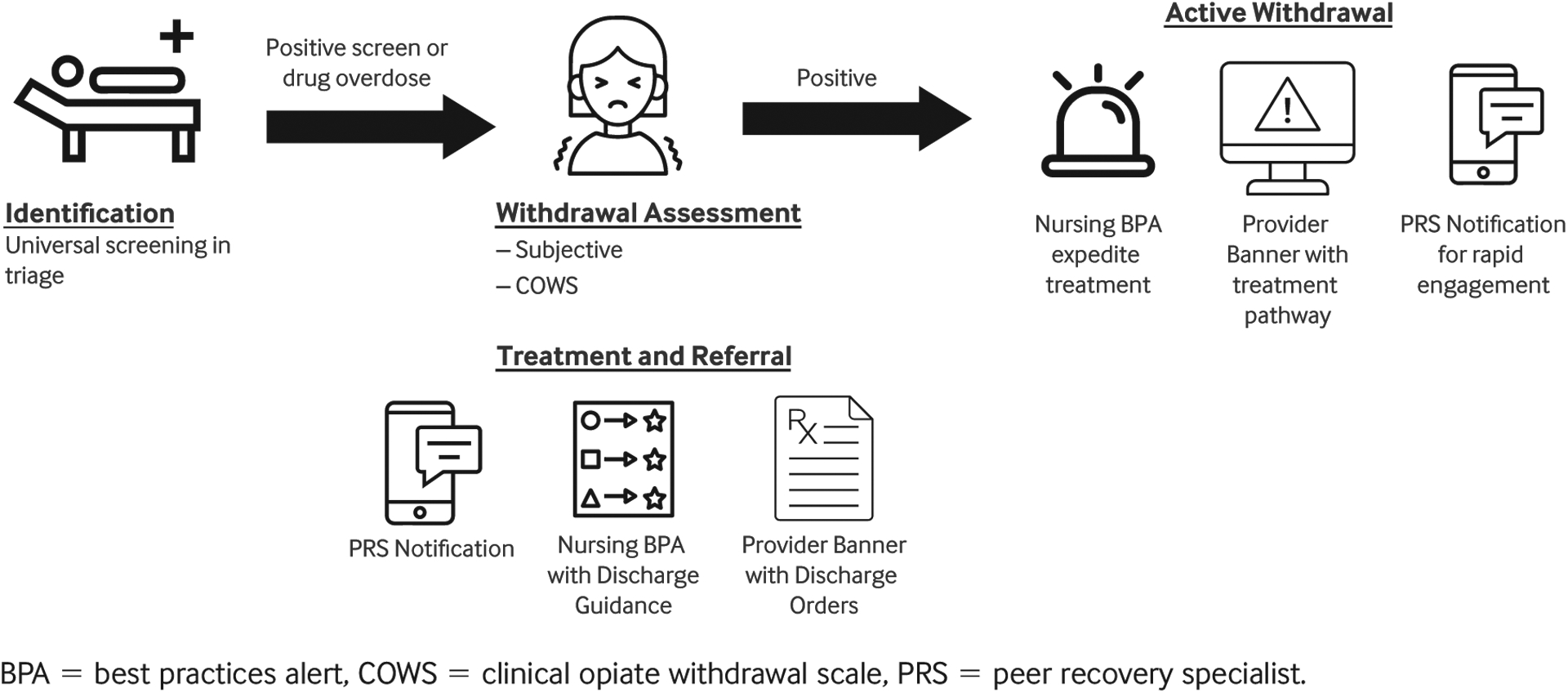

We pivoted instead to a strategy of universal screening by triage nursing with tailored prompts for treatment and referral (Figure 1). Screening for other high-risk conditions is commonplace in EDs, even for conditions in which there is less evidence for effective ED intervention,25 and this approach was preferred by focus group participants.

FIGURE 1.

ED Screening Workflow

“All clinician groups supported empowering nurses to take an active role in identifying patients and initiating treatment pathways, as well as involving peer recovery specialists early to promote engagement and discharge planning.”

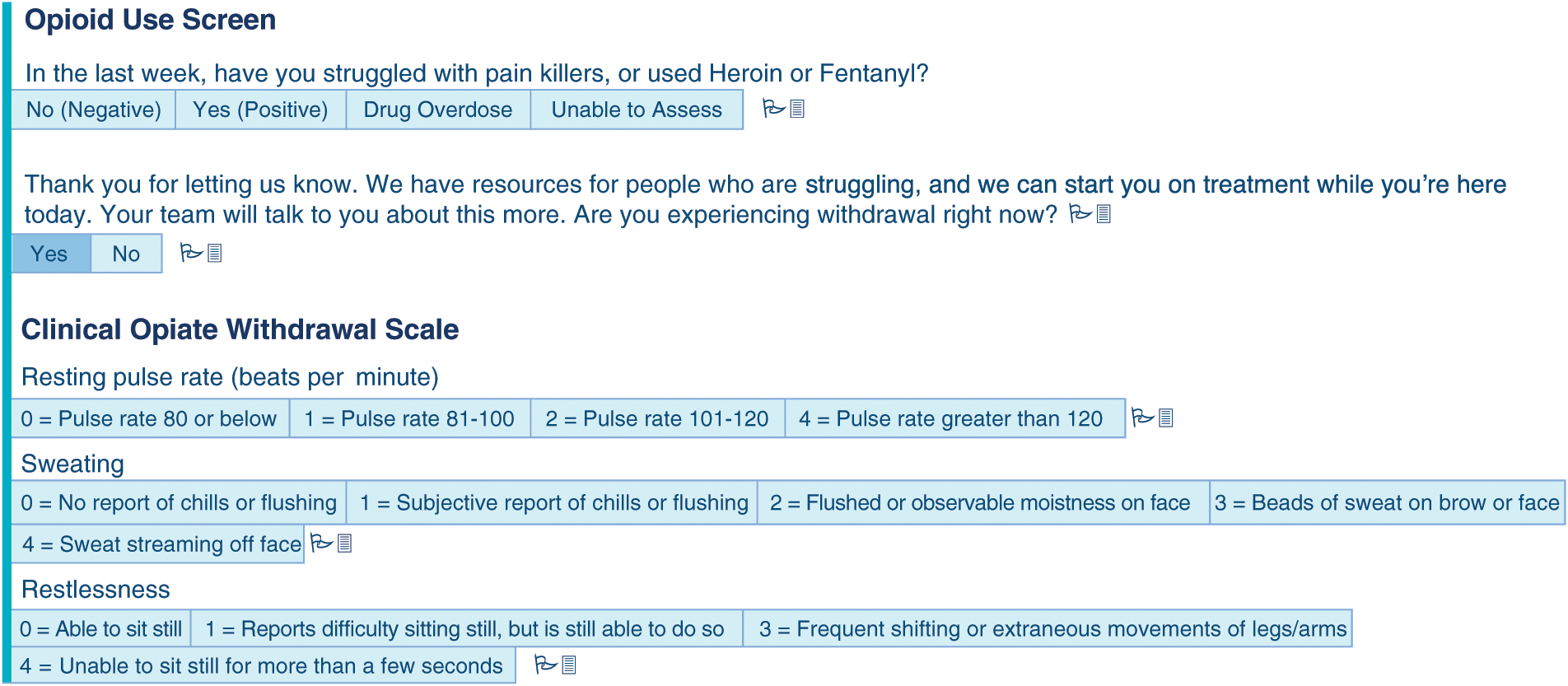

As of March 2021, the universal screening protocol was integrated with other screenings performed at Penn Medicine ED triage in a pilot at two hospitals within the health system. A positive screen or overdose triggers the nurse to assess the patient for withdrawal, including a subjective measure (asking patient whether they are experiencing withdrawal) and an objective measure (COWS), allowing nursing to adjust triage assessment appropriately.

The next steps are tailored to each provider group. Peer recovery specialists receive a real-time, secure mobile application alert for positive screens with an additional alert for a patient with active opioid withdrawal (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Opioid Use Triage Screen

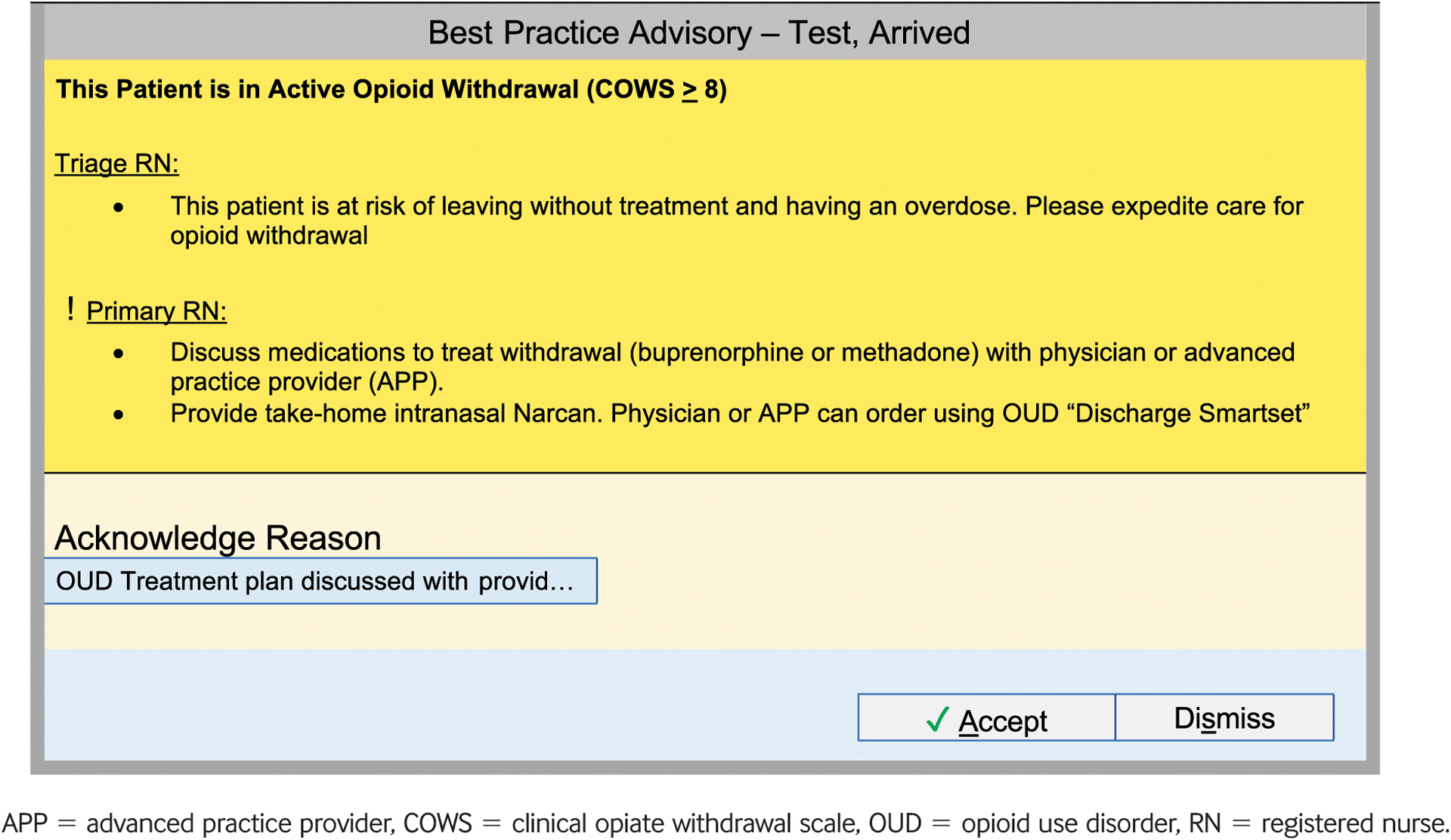

Nurses receive a BPA prompting them to discuss withdrawal treatment with the provider and to dispense naloxone for overdose prevention (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Best Practice Alert

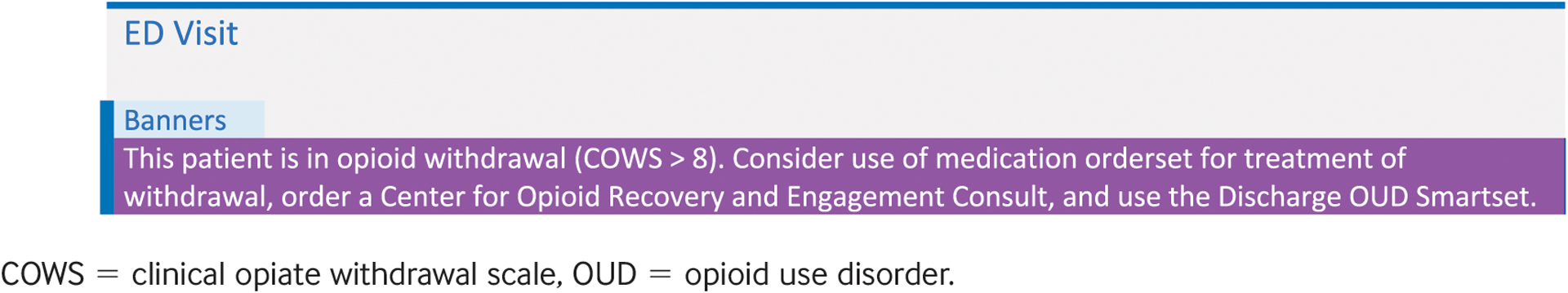

Finally, physicians and advanced practice clinicians see a noninterruptive banner in the EHR containing reminders to assess withdrawal and consult the peer recovery specialist team, as well as links to order sets for ED OUD management and discharge orders (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Banner

Hurdles

Over the course of the project, which spanned approximately 20 months, from September 2019 to May 2021, we have worked through multiple hurdles related to screening protocols, patient needs, and care coordination.

Concerns About Universal Screening in Triage

Some clinicians expressed concerns that screening would be time consuming or alienate patients. In implementing the screening in triage, we weighed these concerns against the known high burden of OUD in Philadelphia and our patient population, the potential for severe outcomes if OUD is undetected or untreated,26 and the fact that there is clear, evidence-based treatment to offer when a patient endorses active OUD and withdrawal. Prior evidence suggests that ED directors nationally are open to screening and other preventive services if they do not increase costs or length of stay.25 To address these concerns with our stakeholders, we ran multiple small pilots and identified sensitive question and response scripting. We also found the screening process to be feasible and valued among triage nurses while not significantly adding to overall triage time. While stakeholders in our study saw a benefit to early identification in triage and ED governance groups approved of the proposal, this model may not be appropriate for all EDs.27 However, the process described could be applied in different ED contexts to develop appropriate strategies tailored to local context.

“Effective care redesign hinges on incorporating stakeholder input throughout the process and being open to unexpected suggestions.”

Diverse Patient Needs

We observed that patients with OUD varied in clinical needs and treatment readiness. Patients in withdrawal need care most urgently, so we included withdrawal assessment as soon as a patient reported active OUD. We also developed harm reduction brochures for all patients who endorsed substance use regardless of treatment interest, which included education on safe use and community harm reduction resources.

Care Coordination

To maximize the effectiveness of all ED-initiated treatment interventions for OUD, patients often need support to overcome barriers after leaving the ED, as well as help with follow-up. The EHR automatically connected peer recovery specialists through real-time notifications. Peer recovery specialists work with health system care coordination to schedule follow-up in primary care or specialty substance use treatment settings that offer MOUDs, including within our own health system. Peers may also provide support, motivation, and navigation support to assist with initial appointment attendance. However, challenges remain in engaging with patients seen after hours or not started on treatment in the ED.

The Team

- Clinician-Research Team:

- ED physicians (3)

- ED nurse (1)

- Addiction medicine physicians (2)

- Research coordinators (2)

- Behavioral science expert (1)

- Implementation Science Expert (1)

Penn Medicine Integrated Clinical Decision Support Committee (oversight)

ED Operational Leadership

Peer Recovery Specialist Team

Clinicians at four Outpatient Primary Care practices and one Behavioral Health-Based OUD Treatment Practice where patients are referred for OUD treatment after their ED visit

Metrics

The first phase of our work was to implement screening, beginning in March 2021. In the first 10 weeks of screening, 92% (23,608 of 25,798 patients) completed the OUD triage screening. Of those screened, 1.61% (415) had a positive screen, including 1.46% (377) endorsing active OUD in the past week and 0.15% (38) with an overdose (Table 4).

Table 4.

Screening Outcomes

| Screening outcomes, No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 377 (1.46) |

| Overdose | 38 (0.15) |

| No | 22,613 (87.65) |

| Unable to assess | 580 (2.25) |

| Missing | 2,190 (8.49) |

| Proportion positive screen | 415 (1.61) |

| Triage time in minutes, mean (SD) | |

| Overall | 3.8 (15.0) |

| Any completed screen | 3.8 (15.3) |

| Yes | 5.2 (5.4) |

| Overdose | 6.3 (5.8) |

| No | 3.7 (15.6) |

| Missing/Unable to assess | 4.9 (8.1) |

These represent data from the first 10 weeks of screening (March 2021–May 2021). SD 5 standard deviation.

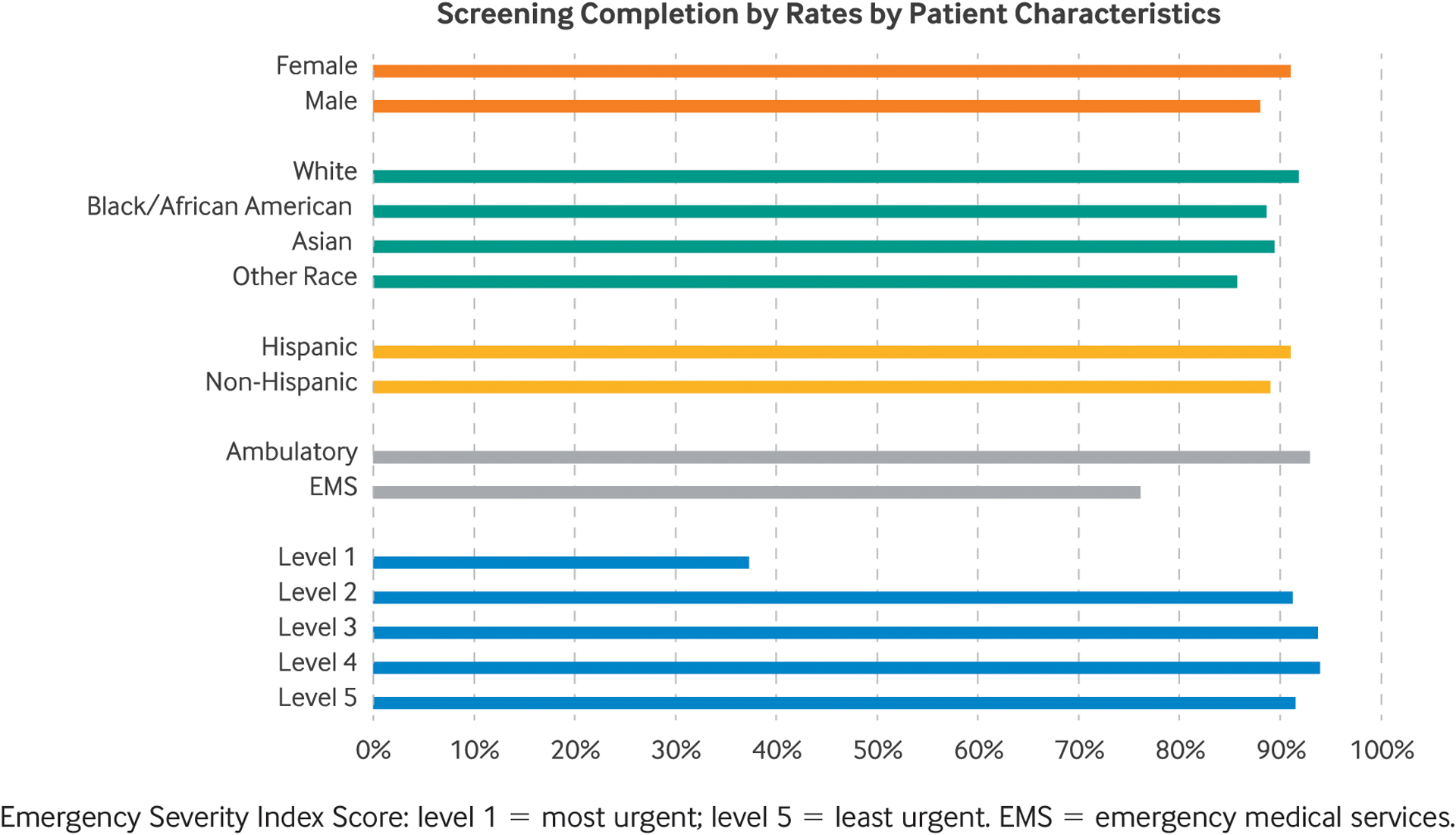

The mean total time spent in triage was 3.8 minutes overall, with 5.2 minutes for patients with a positive screen, even with the prompts to assess and measure withdrawal. The average triage time at the two hospitals in the 2 months prior to screening rollout was 3.6 minutes, meaning that the addition of the triage question added roughly 12 seconds to the triage process. Compared with those in whom screening was completed, patients who did not complete screening were more likely to arrive by ambulance transport and have greater severity on the basis of Emergency Severity Index Score (level 1 being highest score). Screening completion was also slightly higher for women and white patients compared with men and racial minorities (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Characteristics of Patients Completing Screening

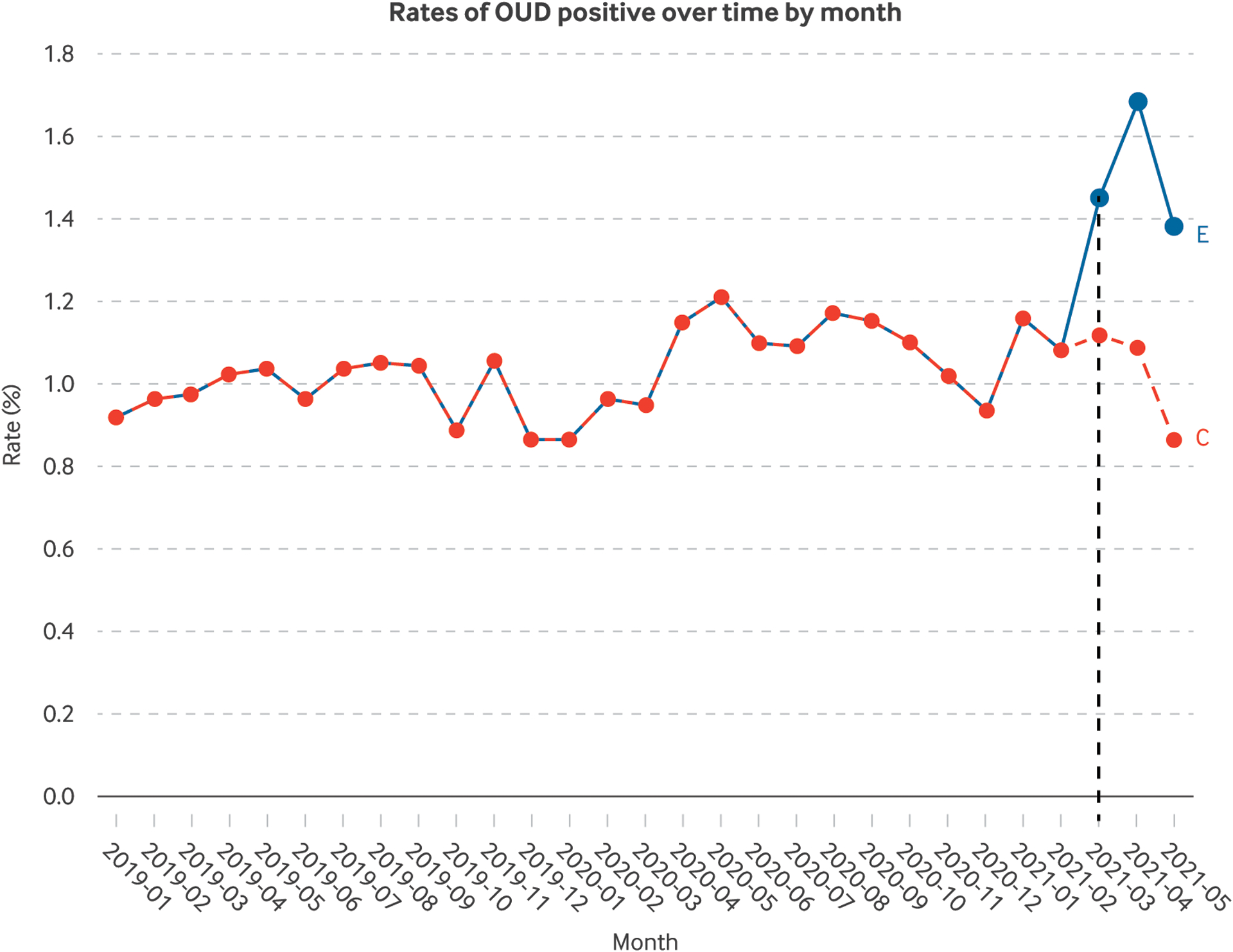

Screening increased the identification of patients with symptoms suggestive of OUD compared with other identification methods such as the use of administrative data diagnosis codes ( Figure 6). In the first 10 weeks of implementation, the triage screening yielded 860 patients, including 273 patients not identified by diagnosis code data. This represented an absolute increase of 0.48% of all patients presenting to the ED and a 47% relative increase in the overall identification of at-risk patients.

FIGURE 6. Patients Identified Through Screening.

The vertical dashed line represents the first month of screening, March 2021. The blue line demonstrates the increased number of patients identified by screening compared with diagnosis codes alone (the red line). Screening led to a net increase of 0.5% in patients identified relative to using diagnosis codes alone. While there was an initial large increase in the rate of positive screening and then a flattening, we saw a similar trend in those identified with diagnosis codes alone, consistent with the variability in ED presentation rate over time. OUD 5 opioid use disorder.

Next Steps

The screening protocol is ongoing, with plans to evaluate and expand it to other EDs in the health system. The next phase of this study will be to measure outcomes from the new protocol.

Outcomes include process measures (e.g., withdrawal assessment) and treatment measures (e.g., use of buprenorphine). We also plan to elicit patient feedback about the screening process to ensure it is acceptable and appropriate. If effective, we will use a similar process of stakeholder engagement and implementation science principles to expand to additional EDs and tailor to existing local resources.

Where to Start

Effective care redesign hinges on incorporating stakeholder input throughout the process and being open to unexpected suggestions. The initial impetus for the work came from clinical champions looking to improve care; we received Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant funding to support the focus groups and research staff, but much of the work was done using existing resources for quality improvement in our health system. The goal to was create sustainable tools in the EHR that could continue past the funding period. Once implemented, the screening requires minimal funding — just for monitoring and making minor updates. For us, the process led to the development of a nursing-driven triage protocol supported by EHR tools tailored to needs and preferences of different stakeholders. For others looking to undertake such an initiative, we recommend the engagement of ED leadership, IT services, ED clinicians, and peer recovery support services early and often in the redesign process and the use of focus groups and pilot testing to refine and adapt the model.

KEY TAKEAWAYS.

Use an inclusive process. Replacing traditional strategies of ED opioid use disorder (OUD) care requires reimagining the visit from start to finish. We incorporated insights from diverse clinician groups, in an iterative fashion, to create a screening protocol that identified patients early in their ED stay and prompted assessment and treatment.

Empower all team members. We learned that physicians wanted nurses to drive more aspects of OUD care, and nurses were eager to do this. This insight led to a nurse-driven triage protocol that initiated OUD care well before a patient encountered their treating clinician.

Integrate peer recovery support. Recognize that in addition to medical care for OUD, peer recovery support can promote engagement and should be prompted early in the ED visit to maximize opportunities for discharge planning.

Account for preferences. We were surprised at differences in preferences for decision support among clinician groups, although this allowed us to design electronic health record (EHR) decision support tailored to physician versus nursing preferences and existing workflows.

Combine high tech and low tech. Our initial plan was to automate identification of patients with OUD, but we learned that a manual screening process identified patients with OUD who were missed using this algorithm. Positive screens then triggered the automated process in the EHR downstream.

Make the right thing the easy thing. Identifying patients early in their ED stay means that we can prompt care pathways for effective treatment.

Substance use remains stigmatized. We needed to ensure substance use screening and treatment were performed sensitively and that we responded to patient needs wherever they were in their recovery process.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Margaret Lowenstein, Rachel McFadden, Dina Abdel-Rahman, Jeanmarie Perrone, Zachary Meisel, Nicole O’Donnell, Christian Wood, Gabrielle Solomon, Rinad Beidas, and M. Kit Delgado have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Margaret Lowenstein, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Rachel McFadden, Emergency Nurse, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Center F Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Dina Abdel-Rahman, Project Manager, Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Jeanmarie Perrone, Professor of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Director, Division of Medical Toxicology and Addiction Medicine Initiatives, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Founding Director, Penn Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Zachary F. Meisel, Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Nicole O’Donnell, Certified Recovery Specialist, Penn Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Christian Wood, Medical Student, Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Gabrielle Solomon, Student, Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Rinad Beidas, Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Director, Penn Medicine Nudge Unit and the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Director, Penn Implementation Science Center, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

M. Kit Delgado, Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Assistant Professor, Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Associate Director, Penn Medicine Nudge Unit and the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Director, University of Pennsylvania Behavioral Science and Analytics for Injury Reduction, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increase in Fatal Drug Overdoses Across the United States Driven by Synthetic Opioids Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. December 17, 2020. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00438.asp.

- 2.Rosenbaum J, Lucas N, Zandrow G, et al. Impact of a shelter-in-place order during the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of opioid overdoses. Am J Emerg Med 2021;41:51–4 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735675720311645?via%3Dihub https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appa A, Rodda LN, Cawley C, et al. Drug overdose deaths before and after shelter-in-place orders during the COVID-19 pandemic in San Francisco. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2110452 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2779782 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (2):CD002207 https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4/full https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancher M, Leshner AI, eds. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538936/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Onofrio G, Venkatesh A, Hawk K. The adverse impact of Covid-19 on individuals with OUD highlights the urgent need for reform to leverage emergency department–based treatment. NEJM Catalyst. June 12, 2020. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0190. [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;313:1636–44 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2279713 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin A, Mitchell A, Wakeman S, White B, Raja A. Emergency department treatment of opioid addiction: an opportunity to lead. Acad Emerg Med 2018;25:601–4 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.13367 https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Use Philadelphia. Unintentional Overdose Deaths. Philadelphia Department of Public Health. 2020. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.substanceusephilly.com/unintentional-overdose-deaths. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster SD, Lee K, Edwards C, et al. Providing incentive for emergency physician X-waiver training: an evaluation of program success and postintervention buprenorphine prescribing. Ann Emerg Med 2020;76:206–14 https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(20)30140-2/fulltext https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families. Updated 2021. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP21-02-01-002.pdf. [PubMed]

- 12.Hawk K, Hoppe J, Ketcham E, et al. Consensus recommendations on the treatment of opioid use disorder in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2021;78:434–42 https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(21)00306-1/fulltext https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delgado MK, Shofer FS, Patel MS, et al. Association between electronic medical record implementation of default opioid prescription quantities and prescribing behavior in two emergency departments. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:409–11 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11606-017-4286-5 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4286-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: a physician survey. Am J Emerg Med 2019;37:1787–90 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7556325/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1340–4 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb071595. 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Nudge units to improve the delivery of health care. N Engl J Med 2018;378:214–6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6143141/ https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1712984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland WC, Nath B, Li F, et al. Interrupted time series of user-centered clinical decision support implementation for emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:753–63 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7496559/#__ffn_sectitle https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melnick ER, Nath B, Ahmed OM, et al. Progress report on EMBED: a pragmatic trial of user-centered clinical decision support to implement EMergency Department-Initiated BuprenorphinE for Opioid Use Disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci 2020;5:e200003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7164817/ https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20200003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatesh A, Malicki C, Hawk K, D’Onofrio G, Kinsman J, Taylor A. Assessing the readiness of digital data infrastructure for opioid use disorder research. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2020;15:24 https://ascpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13722-020-00198-3. 10.1186/s13722-020-00198-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bart GB, Saxon A, Fiellin DA, et al. Developing a clinical decision support for opioid use disorders: a NIDA center for the clinical trials network working group report. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2020;15:4 https://ascpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13722-020-0180-2. 10.1186/s13722-020-0180-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta M, Veith J, Szymanski S, Madden V, Hart JL, Kerlin MP. Clinicians’ perceptions of behavioral economic strategies to increase the use of lung-protective ventilation. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019;16: 1543–9 https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201905-410OC https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201905-410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Dedoose. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.dedoose.com/.

- 23.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci 2009;4:50 https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.pdf. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safaeinili N, Brown-Johnson C, Shaw JG, Mahoney M, Winget M. CFIR simplified: pragmatic application of and adaptations to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for evaluation of a patient-centered care transformation within a learning health system. Learn Health Syst 2019;4:e10201 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/lrh2.10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delgado MK, Acosta CD, Ginde AA, et al. National survey of preventive health services in US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:104–108.e2 https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(10)01245-X/fulltext https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, Schuur JD. One-year mortality of patients after emergency department treatment for nonfatal opioid overdose. Ann Emerg Med 2020;75:13–7 https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(19)30343-9/fulltext https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Policy statement: screening questions at triage. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:P115 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]