Abstract

Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6 transforms 2,2′-dihydroxy-3,3′-dimethoxy-5,5′-dicarboxybiphenyl (DDVA), a lignin-related biphenyl compound, to 5-carboxyvanillic acid via 2,2′,3-trihydroxy-3′-methoxy-5,5′-dicarboxybiphenyl (OH-DDVA) as an intermediate (15). The ring fission of OH-DDVA is an essential step in the DDVA degradative pathway. A 15-kb EcoRI fragment isolated from the cosmid library complemented the growth deficiency of a mutant on OH-DDVA. Subcloning and deletion analysis showed that a 1.4-kb DNA fragment included the gene responsible for the ring fission of OH-DDVA. An open reading frame encoding 334 amino acids was identified and designated ligZ. The deduced amino acid sequence of LigZ had 18 to 21% identity with the class III extradiol dioxygenase family, including the β subunit (LigB) of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase of SYK-6 (Y. Noda, S. Nishikawa, K.-I. Shiozuka, H. Kadokura, H. Nakajima, K. Yano, Y. Katayama, N. Morohoshi, T. Haraguchi, and M. Yamasaki, J. Bacteriol. 172:2704–2709, 1990), catechol 2,3-dioxygenase I (MpcI) of Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP222 (M. Kabisch and P. Fortnagel, Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3405–3406, 1990), the catalytic subunit of the meta-cleavage enzyme (CarBb) for 2′-aminobiphenyl-2,3-diol from Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10 (S. I. Sato, N. Ouchiyama, T. Kimura, H. Nojiri, H. Yamane, and T. Omori, J. Bacteriol. 179:4841–4849, 1997), and 2,3-dihydroxyphenylpropionate 1,2-dioxygenase (MhpB) of Escherichia coli (E. L. Spence, M. Kawamukai, J. Sanvoisin, H. Braven, and T. D. H. Bugg, J. Bacteriol. 178:5249–5256, 1996). The ring fission product formed from OH-DDVA by LigZ developed a yellow color with an absorption maximum at 455 nm, suggesting meta cleavage. Thus, LigZ was concluded to be a ring cleavage extradiol dioxygenase. LigZ activity was detected only for OH-DDVA and 2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydroxy-5,5′-dicarboxybiphenyl and was dependent on the ferrous ion.

Lignin is the most common aromatic compound in the biosphere, and the degradation of lignin is a significant step in the global carbon cycle. Lignin is composed of various intermolecular linkages between phenylpropanes and guaiacyl, syringyl, p-hydroxyphenyl, and biphenyl nuclei (5, 34). Lignin breakdown therefore involves multiple biochemical reactions involving the cleavage of intermonomeric linkages, demethylations, hydroxylations, side-chain modifications, and aromatic ring fission (10, 11, 19, 40).

Soil bacteria are known to display ample metabolic versatility toward aromatic substrates. Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6 (formerly Pseudomonas paucimobilis SYK-6) has been isolated with 2,2′-dihydroxy-3,3′-dimethoxy-5,5′-dicarboxybiphenyl (DDVA) as a sole carbon and energy source. This strain can also grow on syringate, 3-O-methylgallic acid (3OMGA), vanillate, and other dimeric lignin compounds, including β-aryl ether, diarylpropane (β-1), and phenylcoumaran (15). Analysis of the metabolic pathway has indicated that the dimeric lignin compounds are degraded to protocatechuate or 3OMGA (15) and that these compounds are cleaved by protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase encoded by ligAB (30). Among the dimeric lignin compounds, the degradation of β-aryl ether and the biphenyl structure is the most important, because β-aryl ether is most abundant in lignin (50%) and the biphenyl structure is so stable that its decomposition should be rate limiting in lignin degradation. We have already characterized the β-etherase and Cα-dehydrogenase genes (23–26) (ligFE and ligD, respectively) involved in the degradation of β-aryl ether. In this study, we focused on the genes responsible for the degradation of DDVA in SYK-6.

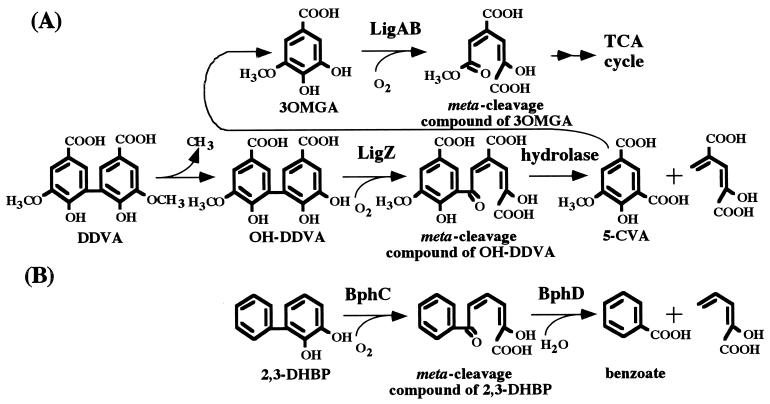

In the proposed DDVA metabolic pathway of S. paucimobilis SYK-6 illustrated in Fig. 1A, DDVA is first demethylated to produce the diol compound 2,2′,3-trihydroxy-3′-methoxy-5,5′-dicarboxybiphenyl (OH-DDVA). OH-DDVA is then degraded to 5-carboxyvanillic acid (5-CVA), and this compound is converted to 3OMGA (15). The resulting product is cleaved by protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase. A ring cleavage enzyme for OH-DDVA has been thought to be involved in this pathway because the production of 5-CVA from OH-DDVA resembles the formation of benzoic acid from biphenyl by 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl through the sequential action of a meta cleavage enzyme and a meta-cleavage compound hydrolase (Fig. 1B) (1, 9, 13, 18, 21, 28).

FIG. 1.

(A) Proposed metabolic pathway for DDVA by S. paucimobilis SYK-6. (B) Pathway for the conversion of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (2,3-DHBP) to benzoate by the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading bacteria. The proposed DDVA metabolic pathway follows the previous one (15). Enzymes: LigZ, OH-DDVA oxygenase; LigAB, protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase; BphC, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase; BphD, 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid hydrolase. TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

In this study, we isolated the ligZ gene encoding a ring cleavage enzyme for OH-DDVA. The nucleotide sequence of the gene was determined, and the ligZ gene product was characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. paucimobilis SYK-6 was isolated from a kraft pulp effluent (16) and reclassified from P. paucimobilis based on its fatty acid composition and 16S ribosomal DNA sequence (accession no. D16149). This strain could grow on a mineral salts medium (W-medium) containing 0.2% DDVA as a sole carbon source. The W-medium was composed of KH2PO4 (0.85 g/liter), Na2HPO4·12H2O (4.90 g/liter), (NH4)2SO4 (0.50 g/liter), MgSO4·7H2O (0.10 g/liter), FeSO4·7H2O (9.50 mg/liter), MgO (10.75 mg/liter), CaCO3 (2.00 mg/liter), ZnSO4·7H2O (1.44 mg/liter), MnSO4·4H2O (1.12 mg/liter), CuSO4·5H2O (0.25 mg/liter), CoSO4·7H2O (0.28 mg/liter), H3BO4 (0.06 mg/liter), and concentrated HCl (5.13 × 10−2 ml/liter) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. paucimobilis SYK-6 | Wild-type strain, able to grow on DDVA | 16 |

| S. paucimobilis NT21 | NTG mutant of S. paucimobilis SYK-6, able to grow on 3OMGA but not on DDVA, OH-DDVA, and DDPA | This study |

| E. coli MV1190 | Δlac-proAB Δstl-recA306::Tn10 supE thi− (F′ lacIqlacZΔM15 proAB traD36) | Takara Shuzo Co. |

| E. coli HB101 | F−hsdS20 (rB− mB−) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 (Smr) xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44 λ− | Takara Shuzo Co. |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKT230 | Pseudomonas-E. coli shuttle cosmid vector, Kmr | 17 |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector, Apr | 41 |

| pDDV21 | pKT230 with 15- and 12-kb EcoRI fragments of S. paucimobilis SYK-6 DNA | This study |

| pTE01 | pUC19 carrying 15-kb EcoRI fragment of pDDV21 | This study |

| pTE491 | pUC19 carrying 4.9-kb HindIII fragment of pTE01 | This study |

| pRZ01 | pUC19 carrying 2.8-kb HindIII-SalI fragment of pTE491 | This study |

| pHE02, pHE06, pHE08, pHE11 | Deletion clones of pTE491 (see Fig. 3) | This study |

| pFK09, pFK17, pFK27, pFK30 | Deletion clones of pTE491 (see Fig. 3) | This study |

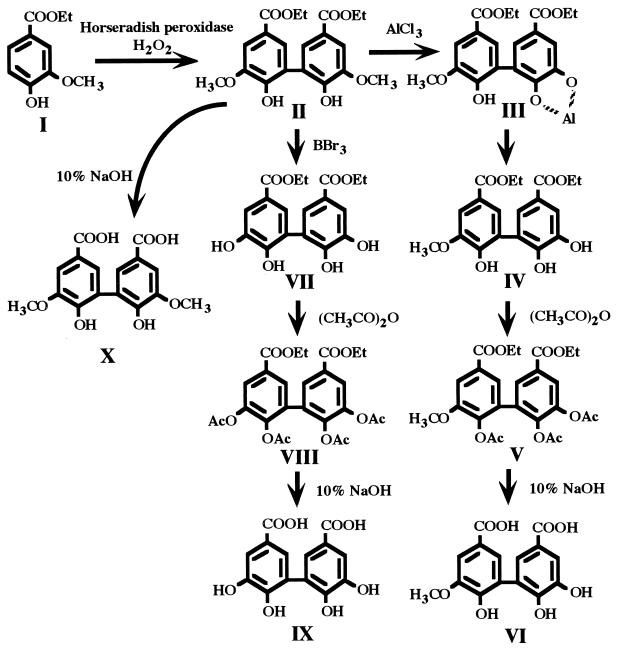

Synthesis of model lignin compounds.

The substrates for growth and the enzyme reaction, DDVA, OH-DDVA, and 2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydroxy-5,5′-dicarboxybiphenyl (DDPA), were synthesized as illustrated in Fig. 2 from vanillic acid ethyl ester (compound I), which was purchased from Tokyo Kasei Kogyo Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

FIG. 2.

Preparation of DDVA (X), OH-DDVA (VI), and DDPA (IX). Details of the synthesis from vanillic acid ethyl ester (I) are described in Materials and Methods. Et, ethyl; Ac, acetyl.

Compound I was dimerized with horseradish peroxidase (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and hydrogen peroxide to produce 2,2′-dihydroxy-3,3′-dimethoxy-5-5′-dicarboxybiphenyl diethyl ether (compound II). Partial demethylation of compound II with AlCl3 and pyridine in refluxing dichloromethane for 12 h by the method of Lange (20) yielded crude compound III, which converted to compound IV spontaneously. Complete demethylation of compound II with BBr3 and dichloromethane by the method of McOmie et al. (27) yielded crude compound VII. Crude compounds IV and VII were acetylated with acetic anhydride and pyridine, and the resultant compounds, compounds V and VIII, were purified by column chromatography on silica gel eluted with dichloromethane-methanol (1/10 [vol/vol]). OH-DDVA (compound VI), DDPA (compound IX), and DDVA (compound X) were prepared by hydrolysis of the protecting groups of compounds V, VIII, and II, respectively, with 10% sodium hydroxide under atmospheric nitrogen. 3OMGA was prepared by the method of Scheline (36). These compounds were confirmed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The mass spectrum of the trimethylsilyl derivative of OH-DDVA had a molecular ion (M) at m/z 680 and major fragment ions at m/z 665 and 503. That of DDPA had a molecular ion (M) at m/z 738 and a major fragment ion at m/z 723. That of DDVA had a molecular ion (M) at m/z 622 and major fragment ions at m/z 607 and 445. That of 3OMGA had a molecular ion (M) at m/z 400 and major fragment ions at m/z 385 and 223. These molecular masses were in agreement with those described in a previous report, in which the compound structures were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance analysis (15).

Protocatechuate and other chemicals were purchased from Tokyo Kasei Kogyo Co. or Wako Pure Chemical Industries.

Isolation and biochemical analysis of the mutant strain.

S. paucimobilis SYK-6 was grown to the stationary phase in 5 ml of L broth. Cells were washed twice with 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.5) and suspended in 10 ml of the same buffer containing 0.5 mg of N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG). After being kept at room temperature for 30 min, the cells were washed twice with 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), resuspended in mineral salts medium (W-medium), and incubated in the presence of OH-DDVA for 10 h at 28°C before the addition of ampicillin (600 mg/liter) and D-cycloserine (300 mg/liter) to select growth-defective mutants on OH-DDVA. After 12 h, the cells were washed with potassium phosphate buffer and plated on L-agar plates. After incubation at 28°C for 48 h, the colonies were replicaplated onto W-medium plates containing 0.2% OH-DDVA or 3OMGA. After 120 h, colonies which grew on 3OMGA but not on OH-DDVA were isolated.

A candidate for an OH-DDVA oxygenase-defective mutant, strain NT21, was subjected to biochemical analysis. S. paucimobilis SYK-6 and NT21 were grown in 100 ml of L broth for 18 h. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in 100 ml of W-medium containing 200 mg of DDVA. After incubation for 12 h at 28°C to induce OH-DDVA oxygenase production, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and homogenized by use of a mortar and pestle with aluminum oxide on ice. The homogenate was suspended in 2 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 27,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min to obtain a cell extract. Each cell extract was subjected to an assay for OH-DDVA oxygenase and protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase activities. These activities were determined with an oxygen electrode as described below.

Cloning and DNA sequencing of the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene.

The gene library constructed with pKT230 as a vector was introduced into NT21 by triparental mating (3). The 15-kb EcoRI fragment of plasmid pDDV21, which complemented the growth deficiency of NT21 on OH-DDVA, was subcloned into pUC19 and designated pTE01. The 4.9-kb HindIII fragment of pTE01 was subcloned to generate pTE491. Various deletion clones were constructed from pTE491 by use of restriction enzymes and Escherichia coli exonuclease III (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the dideoxy chain termination method (33) with an ALFred DNA sequencer (Pharmacia, Milwaukee, Wis.). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence was done with Gene Works software (Intelligenetics, Inc., Mountain View, Calif.). Homology comparison was done with a program based on FASTA and included in this software. Parameters of amino acid sequence alignment were as follows: the costs to open and lengthen gaps were 5 and 25, respectively; minimum diagonal length value was 4 and maximum diagonal offset value was 10. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the unweighted pair-group clustering method (29).

Detection of enzymatic activity.

The crude extract (6 mg of protein) was added to 2 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) (buffer A) containing 0.25 mM substrate. Then, the oxygen consumption rates were measured with an oxygen electrode (MD-1000; Iijima Electronics Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan) at 25°C.

Enzymatic activity toward OH-DDVA was also determined by measuring the absorbance at 455 nm with a spectrophotometer (DU-640; Beckman). After the addition of an enzyme preparation (200 μg of protein) to a reaction mixture composed of 0.25 mM OH-DDVA in 900 μl of buffer A, reactions were stopped at 5, 10, 15, and 60 s by the addition of 20 μl of 2 N NaOH, because specific absorption is detected only under alkaline conditions.

To examine metal ion dependency, 20 μl of 10 mM EDTA was added to 980 μl of a reaction mixture containing a crude extract (6 mg of protein) and incubated for 5 h on ice. Twenty microliters of each 10 mM metal salt solution (FeCl3, FeSO4·7H2O, CuSO4·5H2O, MnSO4·4H2O, MgCl2·6H2O, ZnCl2, or CoSO4·7H2O) was added to 1 ml of the EDTA-treated reaction mixture and incubated for 5 h on ice. The OH-DDVA oxygenase activity of each sample was assayed with an oxygen electrode.

Preparation of crude extracts.

A 2-ml overnight culture of E. coli MV1190 containing a recombinant plasmid was inoculated into 200 ml of L broth containing 100 mg of ampicillin per liter. When the optical density at 550 nm reached 0.5, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the mixture was shaken for 3 h. Cells were harvested and washed with 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were resuspended in 5 ml of buffer A, ruptured by passage through a French pressure cell, and centrifuged at 40,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min. The following operations were carried out at 4°C. A 10% solution of streptomycin sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1%, and then the lysate was kept on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The resulting supernatant was recovered and used as a crude extract.

Partial purification of OH-DDVA oxygenase.

Enzyme purification was performed with a fast protein liquid chromatography system (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The crude extract was applied to a Mono Q HR 10/10 column (Pharmacia Biotech). The column was washed with buffer A and eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.3 M NaCl in buffer A. Fractions containing OH-DDVA oxygenase activity were concentrated by ultrafiltration and applied to a Hi Load 16/60 Superdex 200 preparative-grade column (Pharmacia Biotech). OH-DDVA oxygenase was eluted with 0.15 M NaCl in buffer A.

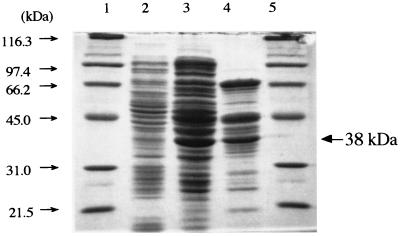

The subunit molecular weight of OH-DDVA oxygenase was estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with a 12.5% acrylamide gel. The partially purified protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon; Millipore Corp.) as described by the manufacturer. The area on the filter containing OH-DDVA oxygenase was cut out and subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequencing with a model 477A protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence in this report has been submitted to the GSDB, DDBJ, EMBL, and NCBI DNA databases under accession number AB007823.

RESULTS

Cloning of the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene.

To isolate the gene responsible for the ring cleavage step of OH-DDVA, growth-deficient mutant NT21 was generated by NTG mutagenesis. NT21 was not able to grow on DDVA and OH-DDVA but could grow on 3OMGA. The cell extract of NT21, which was grown in L broth and induced by DDVA, showed oxygen consumption activity with protocatechuate but not with OH-DDVA. These results suggested that this strain probably lacks ring cleavage ability on OH-DDVA.

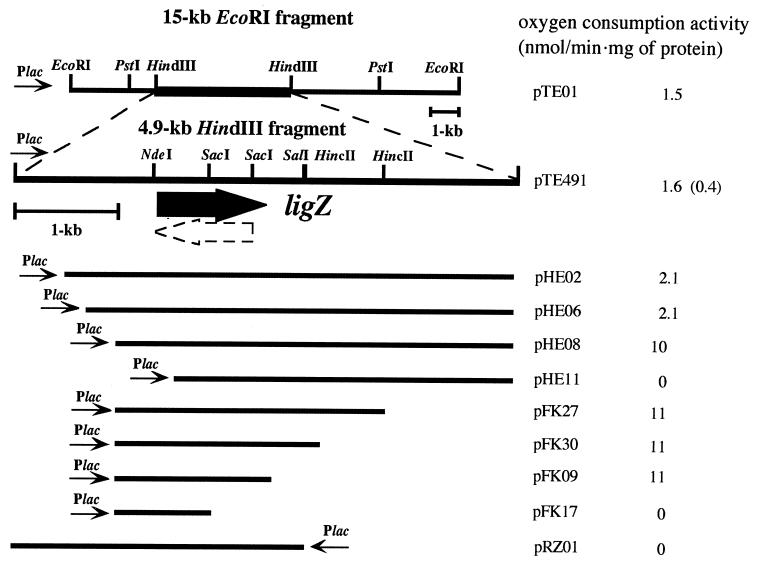

A gene library of SYK-6 (17) was constructed with the broad-host-range vector pKT230 and the partially digested EcoRI fragments of total SYK-6 DNA and was introduced into NT21 by triparental mating (3). The transconjugants that grew on DDVA as a sole carbon source were selected. Each plasmid isolated from the transconjugants had a 15-kb EcoRI fragment. Among these plasmids, plasmid pDDV21, containing two EcoRI inserts, of 15 and 12 kb, was chosen for further study. A subcloning experiment showed that only the 15-kb EcoRI fragment was required to grow on DDVA. A cell extract of E. coli MV1190 containing pUC19 carrying the 15-kb EcoRI fragment (pTE01) and grown with IPTG showed specific oxygen consumption when OH-DDVA was added to the reaction mixture (Fig. 3). This result suggested the existence of the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene in this fragment. After further subcloning experiments, the 4.9-kb HindIII fragment (pTE491) within the 15-kb EcoRI fragment was proven to confer OH-DDVA oxygenase activity (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Deletion analysis to locate the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene (ligZ). The direction of transcription from the vector-located promoter (Plac) is depicted by a thin arrow. The solid arrow represents the location of the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene (ligZ), and the broken arrow indicates another ORF, which overlaps ligZ. The OH-DDVA oxygenase activities of E. coli MV1190 containing pTE01, pTE491, and the deletion plasmids derived from pTE491 are presented on the right. Activity conferred by pTE491 in the absence of IPTG induction is shown in parentheses.

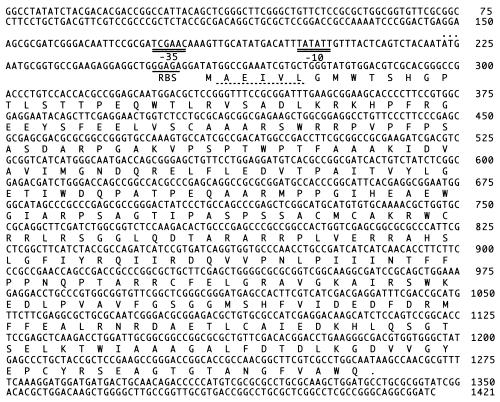

Nucleotide sequence of the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene (ligZ).

A series of deletion derivatives of the 4.9-kb HindIII fragment of pTE491 were constructed, and oxygen consumption activity was examined (Fig. 3). The 1.4-kb fragment of pFK09 conferred the activity and was subjected to nucleotide sequencing.

Two open reading frames (ORF) with opposite transcriptional directions were found in this 1.4-kb fragment, and they overlapped each other entirely. We concluded that the ORF shown as ligZ in Fig. 4 should be a determinant of OH-DDVA oxygenase. We drew this conclusion because recombinant pRZ01, containing this region in the opposite orientation relative to the lac promoter, conferred no OH-DDVA oxygenase activity, even in the presence of IPTG, and plasmid pTE491, containing ligZ in the proper direction relative to the lac promoter, conferred much higher activity in the presence of IPTG than in the absence of IPTG. A sequence (GGAGAG) corresponding to the consensus sequence for the ribosome binding site (RBS) was located 4 bp upstream from the initiation codon of ligZ. The G+C content of the ligZ gene was 67% and was almost identical to those of the other lignin degradation genes of SYK-6 (24, 30). The molecular mass of the ligZ product (LigZ) calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence was 36,961 Da.

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences for the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene (ligZ) from S. paucimobilis SYK-6. The deduced amino acid sequence is presented below the nucleotide sequence. The putative RBS and −10 and −35 promoter sequences are indicated by single underlining and double underlining, respectively. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the 38-kDa product purified partially from E. coli MV1190 containing pFK09 is indicated by broken underlining. Another in-frame ATG initiation codon at nucleotide position 223 is indicated by dots above the nucleotide sequence.

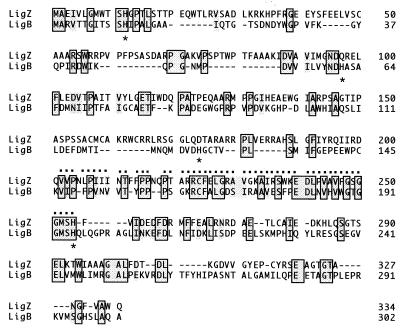

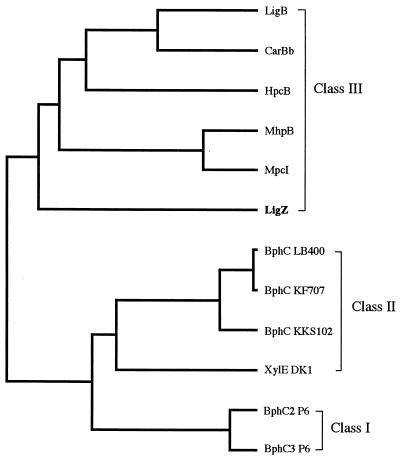

The deduced LigZ amino acid sequence had 21% identity with the β subunit (LigB) of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase (LigAB) of SYK-6 (30), 21% identity with the catalytic subunit of the meta-cleavage enzyme (CarBb) for 2′-aminobiphenyl-2,3-diol from Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10 (35), 20% identity with catechol 2,3-dioxygenase I (metapyrocatechase I; MpcI) of Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP222 (14), and 18% identity with 2,3-dihydroxyphenylpropionate 1,2-dioxygenase (MhpB) of E. coli (38). The similarity between LigZ and the extradiol dioxygenases suggested that LigZ is a member of the extradiol dioxygenase family. LigB, CarBb, MpcI, and MhpB showed little sequence similarity with the extradiol dioxygenases of the major family involving 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases (BphCs) of pseudomonads (4, 38). The former enzymes, as well as 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate 2,3-dioxygenase (HpcB) of E. coli C (32), should be classified as a new extradiol dioxygenase family, class III (38).

Identification of the ligZ gene product in E. coli.

The ligZ gene expression induced by IPTG in E. coli MV1190 was examined with plasmid pFK09. The gene product was not evident before purification, although its oxygenase activity toward OH-DDVA was detected. The cell extract of E. coli MV1190 containing pFK09 was subjected to the Mono Q HR 10/10 and Hi Load 16/60 Superdex 200 preparative-grade column chromatography, and the active fractions were collected. When the partially purified fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5), a 38-kDa protein was observed; this size was in good agreement with the value calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence of LigZ (36,961 Da). The 38-kDa protein was transferred to a PVDF membrane and subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence determination. The resulting sequence, AEIVLGM, corresponded to the deduced N-terminal amino acid sequence of LigZ, except for the first methionine, which appeared to be processed.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE of OH-DDVA oxygenase preparations. Lanes: 1 and 5, molecular mass standard proteins; 2, crude extract of E. coli MV1190(pFK09); 3, active fraction separated on a Mono Q HR 10/10 column; 4, active fraction separated on a Hi Load 16/60 Superdex 200 preparative-grade column after the Mono Q HR 10/10 column.

Substrate specificity of LigZ.

The substrate specificity of LigZ was examined with lignin-related diol compounds, including OH-DDVA, DDPA, gallic acid, and protocatechuate, and other diol compounds, such as 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl, 3-methylcatechol, and catechol. The oxygen consumption activities toward OH-DDVA and DDPA were 21 and 41 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively. No activity was observed toward other compounds, indicating that the substrate specificity of LigZ was very restricted. The LigZ reaction mixture including OH-DDVA developed a yellow color with an absorption maximum at 455 nm after the addition of NaOH. This absorption suggested that the reaction product of OH-DDVA has a semialdehyde structure like that of meta-cleavage products, which are generated from aromatic diol compounds by extradiol dioxygenases (8, 9).

Metal ion dependency of LigZ.

When 10 mM EDTA was added to the reaction mixture containing LigZ, a complete loss of activity was observed. This result indicates that LigZ is dependent on the metal ion (II). The metal ions Fe3+, Fe2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Co2+ were added to the EDTA-treated enzyme preparation. The activity was remarkably recovered by the addition of Fe2+ (142%) and was partially recovered by the addition of Mn2+ (35%) and Co2+ (35%). LigZ probably contains Fe2+ in the catalytic center, as has been suggested for other extradiol dioxygenases (6, 12, 31, 37).

DISCUSSION

In order to clone the gene for the ring cleavage enzyme of OH-DDVA, a mutant (NT21) which could not grow on DDVA and OH-DDVA but which could grow on 3OMGA was constructed. A 15-kb EcoRI fragment which complemented the growth deficiency of NT21 on DDVA was isolated. We determined the nucleotide sequence of the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene, ligZ, and characterized the gene product, LigZ. LigZ showed oxygen consumption activity toward OH-DDVA and DDPA. DDPA was a good substrate for LigZ, showing twice the activity of OH-DDVA. The NTG mutant NT21 grew on neither DDVA nor DDPA. If demethylation of both aromatic rings had occurred, DDVA would have been degraded via DDPA and 5-carboxyprotocatechuate. However, this process did not occur, because OH-DDVA and 5-CVA were detected as intermediate metabolites in the degradation of DDVA in our previous study (15).

An in-frame ATG initiation codon was located at nucleotide position 223, as indicated in Fig. 4. We concluded that this codon is not a functional initiation codon for ligZ because a putative RBS was not found in its upstream region and the N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified LigZ coincided with that deduced from the ATG codon at nucleotide position 259.

In conclusion, the following results would indicate that the 38-kDa protein LigZ encoded by the ligZ gene is responsible for OH-DDVA oxygenase activity. (i) ligZ is the only ORF in the insert of pFK09, in which ligZ has the proper orientation relative to the lac promoter. (ii) pFK09 containing the entire ligZ gene confers OH-DDVA oxygenase activity, but pFK17 lacking the C-terminal region of ligZ and pRZ01 containing the entire ligZ gene in the opposite orientation relative to the lac promoter do not. (iii) The 38-kDa protein has the N-terminal amino acid sequence which completely coincides with that deduced from the ligZ nucleotide sequence.

The deduced amino acid sequence of LigZ showed 18 to 21% identity with the β subunit (LigB) of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase of SYK-6, the catalytic subunit of the meta-cleavage enzyme (CarBb) for 2′-aminobiphenyl-2,3-diol from Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10 (35), catechol 2,3-dioxygenase I (MpcI) of A. eutrophus JMP222, and 2,3-dihydroxyphenylpropionate 1,2-dioxygenase (MhpB) of E. coli. These enzymes have been reported to be extradiol dioxygenases. A significantly high identity (51%) was found between the central portions of LigZ and LigB (Fig. 6). Most extradiol dioxygenases contain a nonheme ferous ion as a prosthetic group and produce a yellow meta-cleavage compound having a semialdehyde structure (8, 9). It was clearly demonstrated that the enzymatic activity of LigZ depended on the ferrous ion, and the reaction product from OH-DDVA had a maximum absorption at 455 nm and became yellow under alkaline conditions. These results strongly indicate that LigZ is a ring-cleavage extradiol dioxygenase. The amino acid sequence homology with LigB, CarBb, MpcI, and MhpB extradiol dioxygenases supports this notion. The identification of meta-cleavage compounds of OH-DDVA and DDPA failed. They were so unstable that we could not obtain any significant results by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of the ethyl acetate extracts of the reaction products. Based on the analogy to the reactions of LigAB (30) and BphC (9, 13, 18, 21, 22, 28, 39), molecular oxygen appeared to be incorporated into OH-DDVA at carbons 1 and 2. The accumulation of 5-CVA during the degradation of DDVA suggested that a hydrolase was involved in the side-chain cleavage of the resulting meta-cleavage compound (Fig. 1).

FIG. 6.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of OH-DDVA oxygenase (LigZ) and the β subunit (LigB) of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase from S. paucimobilis SYK-6. Identical amino acid residues are boxed and shaded. Functionally similar amino acid residues are shaded. A region that is highly conserved between LigZ and LigB is indicated by dots above the LigZ sequence. Asterisks below the LigB sequence represent histidine residues conserved among class III extradiol dioxygenases. Dashes indicate gaps.

A large number of extradiol dioxygenase genes have been characterized. Their products have been divided into three classes by Spence et al. (38). Class I comprises single-domain enzymes, including the BphC2 and BphC3 enzymes of Rhodococcus globerulus P6 (1). Enzymes of classes II and III are composed of duplicated domains. The duplication of a domain corresponding to a whole class I enzyme was suggested by the three-dimensional structural identity between N- and C-terminal half domains (12, 37). The duplication of the class I gene followed by the loss of function of either the N- or the C-terminal domain appeared to have occurred to yield class II or III, respectively. The amino acid sequence similarity indicated that LigZ is a member of class III, which includes LigB, CarBb, MpcI, MhpB, and HpcB. The members of class III have four conserved histidine residues that might function as ferrous ion ligands; however, only two histidine residues are conserved in LigZ (Fig. 6). LigZ might use amino acids other than histidine for a ferrous ion ligand. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 7) shows LigZ separated from other members because the overall homology between LigZ and other members is low.

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic tree of meta-cleavage enzymes. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the unweighted pair-group clustering method (29). The enzyme classification of Spence et al. (38) is indicated on the right. Enzymes: LigB, β subunit of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase of SYK-6 (30); CarBb, catalytic subunit of the meta-cleavage enzyme for 2′-aminobiphenyl-2,3-diol from Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10 (35); HpcB, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate 2,3-dioxygenase of E. coli C (32); MhpB, 2,3-dihydroxyphenylpropionate 1,2-dioxygenase of E. coli (38); MpcI, catechol 2,3-dioxygenase I (metapyrocatechase I) of A. eutrophus JMP222 (14); BphC LB400, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase of Pseudomonas cepacia LB400 (13); BphC KF707, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 (7); BphC KKS102, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102 (18)); XylE DK1, catechol 2,3-dioxygenase of Pseudomonas putida(pDK1) (2); BphC2 P6, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase II of R. globerulus P6 (1); BphC3 P6, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase III of R. globerulus P6 (1).

In this study, we isolated and characterized the OH-DDVA oxygenase gene from S. paucimobilis SYK-6; this gene is involved in the degradation of the lignin-related biphenyl compound DDVA. We also proposed the extradiol ring cleavage mechanism for OH-DDVA oxygenase. In order to elucidate the complete degradation pathway of DDVA, characterization of the genes for other steps in this pathway is now in progress. To date, at least six lig genes have been reported for SYK-6. It will be interesting to examine the distribution of these lig genes on the chromosome. We are trying to map lig genes that lie on different chromosome segments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asturias J A, Eltis L D, Prucha M, Timmis K N. Analysis of three 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases found in Rhodococcus globerulus P6. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7807–7815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin R C, Voss J A, Kunz D A. Nucleotide sequence of xylE from the Tol pDK1 plasmid and structural comparison with isofunctional catechol-2,3-dioxygenase genes from Tol pWW0 and NAH7. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2724–2728. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2724-2728.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski D R. Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eltis L D, Bolin J T. Evolutionary relationships among extradiol dioxygenases. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5930–5937. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5930-5937.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freudenberg K. The constitution and biosynthesis of lignin. In: Neish A C, Freudenberg K, editors. Constitution and biosynthesis of lignin. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1968. pp. 47–122. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furukawa K, Arimura N. Purification and properties of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase from polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes and Pseudomonas aeruginosa carrying the cloned bphC gene. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:924–927. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.924-927.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa K, Arimura N, Miyazaki T. Nucleotide sequence of the 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase gene of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:427–429. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.427-429.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furukawa K, Tomizuka N, Kamibayashi A. Effect of chlorine substitution on the bacterial metabolism of various polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38:301–310. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.2.301-310.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa K, Miyazaki T. Cloning of a gene cluster encoding biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:392–398. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.392-398.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futong C, Dolphin D. The biomimetic oxidation of β-1, β-O-4, β-5, and biphenyl lignin model compounds by synthetic iron porphyrins. Bioorg Med Chem. 1994;2:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(94)85025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold M H, Alic M. Molecular biology of the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:605–622. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.605-622.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han S, Eltis L D, Timmis K N, Muchmore S W, Bolin J T. Crystal structure of the biphenyl-cleaving extradiol dioxygenase from a PCB-degrading pseudomonad. Science. 1995;270:976–980. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofer B, Eltis L D, Dowling D N, Timmis K N. Genetic analysis of a Pseudomonas locus encoding a pathway for biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. Gene. 1993;130:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabisch M, Fortnagel P. Nucleotide sequence of metapyrocatechase I (catechol 2,3-oxygenase I) gene mpcI from Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP222. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3405–3406. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katayama Y, Nishikawa S, Murayama A, Yamasaki M, Morohoshi N, Haraguchi T. The metabolism of biphenyl structures in lignin by the soil bacterium (Pseudomonas paucimobilis SYK-6) FEBS Lett. 1988;233:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katayama Y, Nishikawa S, Nakamura M, Yano K, Yamasaki M, Morohoshi N, Haraguchi T. Cloning and expression of Pseudomonas paucimobilis SYK-6 genes involved in the degradation of vanillate and protocatechuate in P. putida. Mokuzai Gakkaishi. 1987;33:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama Y, Nishikawa S, Yamasaki M, Morohoshi N, Haraguchi T. Construction of the genomic libraries of lignin model compounds degradable Pseudomonas paucimobilis SYK-6 with Escherichia coli-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors. Mokuzai Gakkaishi. 1988;34:423–427. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimbara K, Hashimoto T, Fukuda M, Koana T, Takagi M, Oishi M, Yano K. Cloning and sequencing of two tandem genes involved in degradation of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl to benzoic acid in the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading soil bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2740–2747. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2740-2747.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krisnongkura K, Gold M H. Characterization of guaiacyl lignin degraded by the white rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Holzforschung. 1979;33:174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange R G. Cleavage of alkyl O-hydroxyphenyl ethers. J Org Chem. 1962;27:2037–2039. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masai E, Yamada A, Healy J M, Hatta T, Kimbara K, Fukuda M, Yano K. Characterization of biphenyl catabolic genes of gram-positive polychlorinated biphenyl degrader Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2079–2085. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2079-2085.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masai E, Sugiyama K, Iwasita N, Shimizu S, Hauschild J E, Hatta T, Kimbara K, Yano K, Fukuda M. The bphDEF meta-cleavage pathway genes involved in biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl degradation are located on a linear plasmid and separated from the initial bphACB genes in Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA 1. Gene. 1997;187:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00748-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masai E, Kubota S, Katayama Y, Kawai S, Yamasaki M, Horohoshi N. Characterization of the Cα-dehydrogenase gene involved in the cleavage of β-aryl ether by Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1655–1659. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masai E, Katayama Y, Kawai S, Nishikawa S, Yamasaki M, Morohoshi N. Cloning and sequencing of the gene for a Pseudomonas paucimobilis enzyme that cleaves β-aryl ether. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7950–7955. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7950-7955.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masai E, Katayama Y, Kubota S, Kawai S, Yamasaki M, Morohoshi N. A bacterial enzyme degrading the model lignin compound β-aryl etherase is a member of the glutathione-S-transferase superfamily. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81465-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masai E, Katayama Y, Nishikawa S, Yamasaki M, Morohoshi N, Haraguchi T. Detection and localization of a new enzyme catalyzing the β-aryl ether cleavage in the soil bacterium (Pseudomonas paucimobilis SYK-6) FEBS Lett. 1989;249:348–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McOmie J F W, Watts H L, West D E. Demethylation of aryl methyl ethers by boron tribromide. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:2289–2292. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mondello F J. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of Pseudomonas strain LB400 genes encoding polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1725–1732. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1725-1732.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nei M. Molecular evolutional genetics. New York, N.Y: Columbia University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noda Y, Nishikawa S, Shiozuka K-I, Kadokura H, Nakajima H, Yano K, Katayama Y, Morohoshi N, Haraguchi T, Yamasaki M. Molecular cloning of the protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase genes of Pseudomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2704–2709. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2704-2709.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel T R, Barnsley E A. Naphthalene metabolism by pseudomonas: purification and properties of 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene oxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:668–673. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.668-673.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roper D I, Cooper R A. Subcloning and nucleotide sequence of the 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate (homoprotocatechuate) 2,3-dioxygenase gene from Escherichia coli C. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81437-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkanen K V, Ludwig C H. Lignins. Occurrence, formation, structure and reactions. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Interscience; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato S I, Ouchiyama N, Kimura T, Nojiri H, Yamane H, Omori T. Cloning of genes involved in carbazole degradation of Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10: nucleotide sequences of genes and characterization of meta-cleavage enzymes and hydrolase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4841–4849. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4841-4849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheline R R. A rapid synthesis of 3-O-methylgallic acid. Acta Chem Scand. 1966;20:1182. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senda T, Sugiyama K, Narita H, Yamamoto T, Kimbara K, Fukuda M, Sato M, Yano K, Mitsui Y. Three-dimensional structures of free form and two substrate complexes of an extradiol ring-cleavage type dioxygenase, the BphC enzyme from Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:735–752. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spence E L, Kawamukai M, Sanvoisin J, Braven H, Bugg T D H. Catechol dioxygenase from Escherichia coli (MhpB) and Alcaligenes eutrophus (MpcI): sequence analysis and biochemical properties of a third family of extradiol dioxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5249–5256. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5249-5256.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taira K, Hayase N, Arimura N, Yamashita S, Miyazaki T, Furukawa K. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase gene from the PCB-degrading strain of Pseudomonas paucimobilis Q1. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3990–3996. doi: 10.1021/bi00411a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vicuna R. Bacterial degradation of lignin. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1988;10:646–655. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]