Atherosclerosis, the pathobiological basis for cardiovascular disease (CVD), is a lifelong process and is linked with cardiovascular risk factors, including dyslipidemia.1 Given its often clinically silent nature in childhood, paediatric dyslipidemia can be easily missed. For example, familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), the most common inherited lipid disorder, is present in its heterozygous form in approximately 1:250-300 people and remains profoundly underdiagnosed.2 This is particularly unfortunate for 2 key reasons: a clinical diagnosis is easily achieved via a screening lipid panel (demonstrating markedly elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol)3 and established treatments (namely statin therapy) exist that effectively lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, reduce atherosclerotic burden, and potentially normalize CVD risk.4 Thus, the effective detection and management of FH early in life is imperative and should be considered a public health priority.

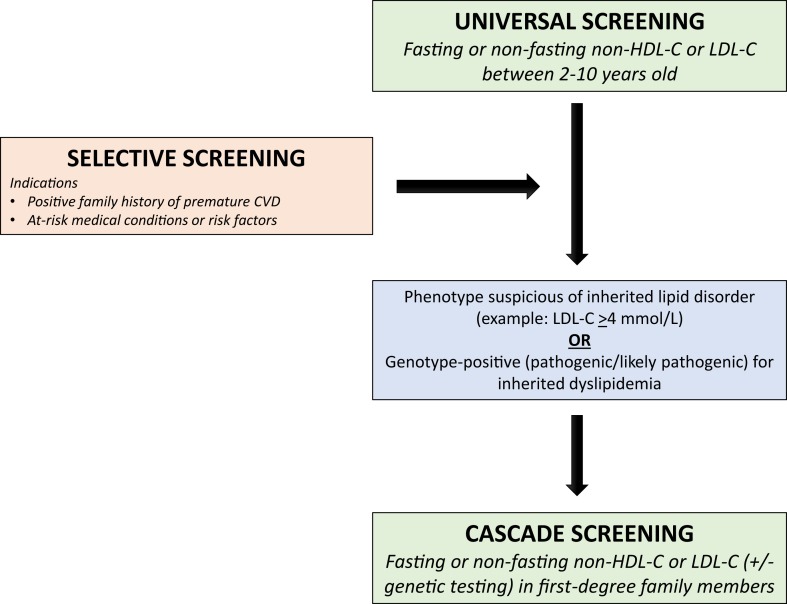

Numerous screening strategies have been proposed to detect FH (Fig. 1). Traditionally, selective screening on the basis of an identified family history of dyslipidemia or premature CVD was proposed. This approach, however, is insufficient, as screening on the basis of family history alone may miss 30%-60% of cases, in part due to incomplete or unknown family histories.5, 6, 7 Universal screening is a preferred method for detecting index cases6,8 and has been proven to be an effective and economical strategy for FH detection, particularly when combined with a cascade screening strategy.9,10 Cascade screening involves the testing of first-degree family members of an index case with FH. Within the paediatric context, cascade screening is particularly important, as the child is often the first member of a family to be diagnosed (through selective or universal screening). Given the autosomal dominant nature of the disease, diagnosing FH in the child often permits the detection of severe dyslipidemia in one of the parents (ie, reverse cascade screening), allowing for treatment before the development of premature CVD. For example, Wald et al.,10 through a primary care screening programme in the United Kingdom, identified 40 children and 40 corresponding parents who screened positive for FH. With each new case identified, cascade screening can be stretched further to identify additional cases. This has proven to be highly effective for FH detection in multiple parts of the world, including in the Netherlands, for example, where approximately 70% of FH cases are estimated to have been identified.11 However, many such successful programmes depend on direct contact from a health care practitioner to first-degree family members, termed direct cascade screening. This is not permissible in Canada due to privacy laws. Thus, indirect cascade screening must be employed, where the patient/family is responsible for reaching out to family members themselves to recommend screening.

Figure 1.

Screening strategies for the detection of familial hypercholesterolemia. CVD, cardiovascular disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; non-HDL-C, non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Reproduced with permission from Khoury et al.8

Having buy-in from families affected by FH is essential to properly realize the potential of cascade screening. Namely, the family of each index case must understand the rationale for screening, the genetic basis for FH, and the implications of missed vs identified cases. Moreover, important factors such as cultural considerations and feelings of guilt or shame must be considered. Thus, an understanding of the knowledge and barriers among families surrounding cascade screening is needed to promote its uptake. Currently, these factors remain poorly understood, particularly within the Canadian context.

In this issue of CJC Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease, Dickson et al.12 undertook a qualitative study design using a Theoretical Domains Framework to detect facilitators and barriers in families with FH that may influence cascade screening efforts. Parents of children with a clinical diagnosis of FH were recruited from the paediatric lipid subspecialty clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. Saturation was achieved after 10 interviews, and 9 of 10 parents interviewed had a self-reported diagnosis of FH. Through the Theoretical Domains Framework, 4 key facilitators were identified: surprise that children are susceptible to FH, knowledge gained through participation in the lipid clinic, the importance of access to trusted specialists, and a sense of responsibility to protect family members from CVD. In addition, 4 key barriers were identified: a lack of educational resources to facilitate giving information to family members and generating public awareness, a lack of primary care practitioner (PCP) awareness with respect to the diagnosis and treatment options in children, a desire to protect the children’s health status to avoid stigma, and the dismissal of the seriousness of FH by relatives.

It is important to note that the implementation of a direct cascade screening programme would address a key identified barrier, namely, the lack of resources available for patients/families to notify and inform their first-degree family members. Despite this, the authors emphasize that the subspeciality clinic educated and empowered families, which in turn helped them understand the importance of cascade screening. Although this is promising, it highlights the possibility for discrepancies in patient knowledge and empowerment as a result of access to care, including subspecialty paediatric lipid clinics, of which there are relatively few in Canada. Supporting this, parents in the present study also identified resistance from PCPs regarding FH screening and treatment with statins in children with FH. Prior work supports this perceived barrier. For example, in a survey administered through the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program, only 3% of primary care providing paediatricians indicated that they perform lipid screening in healthy children “most/all of the time.”13 Moreover, 24% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the notion that statins were appropriate for youth with severe dyslipidemia, despite increasingly robust evidence of their effectiveness and safety.14,15 These findings, coupled with the identified facilitators and barriers in the present study, emphasize the need for continued knowledge translation strategies to improve the uptake of paediatric FH screening and management among Canadian PCPs. In addition, improved access to paediatric subspecialty lipid clinics is needed. Novel strategies are needed to help accomplish this, including the leveraging of existing telemedicine technologies to expand geographic reach and facilitate improved access and convenience for families. Moreover, lipid clinics should position themselves as a centralized hub, whereby they are integrated with primary care practices and the local community, providing clinical support and educational resources to enable PCPs and families alike.

The theoretical framework of this study identified important insights and perceived facilitators and barriers for indirect cascade screening. However, certain limitations were inherent to the study design that must be considered. First, as the authors identify, this study consisted of 10 parents recruited from a dedicated paediatric lipid clinic in a large urban centre, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. Further limiting generalizability was the finding that 8 of 10 parents interviewed identified as White and 9 of 10 had received a college or university education despite an effort to purposely sample and achieve maximal variation in the study population. Finally, there was a lack of emphasis on genetic testing through the interviews and in the study results. The authors indicate that this is largely due to a lack of availability of routine genetic testing for FH in Ontario as part of standard care. Genetic testing is being increasingly recommended and used in FH diagnosis and cascade screening.8,16 The incorporation of genetic testing considerations may have uncovered unique perceived facilitators and barriers that are likely to become increasingly relevant across Canada in the years to come. For example, the parents identified perceived stigma as a significant barrier. This includes the stigma of having a chronic disease, but also the misperception that their child’s dyslipidemia is a result of an unhealthy lifestyle. Genetic testing may serve as a confirmation that the driving etiology at play is not improper dietary or lifestyle choices. Moreover, it may convey the seriousness of FH and the need for testing family members, while also improving the precision and sensitivity of cascade screening, as screening on the basis of a clinical diagnosis alone may be limited by incomplete penetrance in family members.16 It is thus crucial for genetic testing for FH to be made accessible across Canada to facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment. The impact of genetic testing on patient and parent attitudes towards FH cascade screening will require further study.

So where do we go from here? The systematic detection of FH from childhood is crucial to reduce atherosclerotic burden and prevent premature CVD. Our patients and their families are uniquely positioned, existing not only as individuals in need of treatment but also being tasked with the responsibility to disclose a diagnosis and explain and promote screening to their families. We must do all we can to facilitate this and support our patients. Dickson et al. have provided us with a useful framework by which to achieve this.

Acknowledgments

Ethics Statement

The authors confirm that the ethics statement is not applicable to this article.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this editorial.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Berenson G.S., Srinivasan S.R., Bao W., et al. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. The Bogalusa Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1650–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunham L.R., Ruel I., Aljenedil S., et al. Canadian cardiovascular society position statement on familial hypercholesterolemia: update 2018. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:1553–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruel I., Brisson D., Aljenedil S., et al. Simplified Canadian definition for familial hypercholesterolemia. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:1210–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luirink I.K., Wiegman A., Kusters D.M., et al. 20-year follow-up of statins in children with familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1547–1556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiegman A., Gidding S.S., Watts G.F., et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia in children and adolescents: gaining decades of life by optimizing detection and treatment. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2425–2437. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(suppl 5):S213–S256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wald D.S., Bestwick J.P. Reaching detection targets in familial hypercholesterolaemia: comparison of identification strategies. Atherosclerosis. 2020;293:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoury M., Bigras J.L., Cummings E.A., et al. The detection, evaluation, and management of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents: a Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Pediatric Cardiology Association clinical practice update. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:1168–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKay A.J., Hogan H., Humphries S.E., et al. Universal screening at age 1-2 years as an adjunct to cascade testing for familial hypercholesterolaemia in the UK: a cost-utility analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2018;275:434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wald D.S., Bestwick J.P., Morris J.K., et al. Child-parent familial hypercholesterolemia screening in primary care. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1628–1637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordestgaard B.G., Chapman M.J., Humphries S.E., et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3478–3490a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickson M.A., Zahavich L., Rush J., et al. Exploring barriers and facilitators to indirect cascade screening for familial hypercholesteraemia in a paediatric/parent population. CJC Pediat Congenit Heart Dis. 2023;2:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cjcpc.2023.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khoury M., Rodday A.M., Mackie A.S., et al. Pediatric lipid screening and treatment in Canada: practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1545–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoury M., McCrindle B.W. The rationale, indications, safety, and use of statins in the pediatric population. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1372–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vuorio A., Kuoppala J., Kovanen P.T., et al. Statins for children with familial hypercholesterolemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019:CD006401. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006401.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturm A.C., Knowles J.W., Gidding S.S., et al. Clinical genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia: JACC scientific expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:662–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]