Abstract

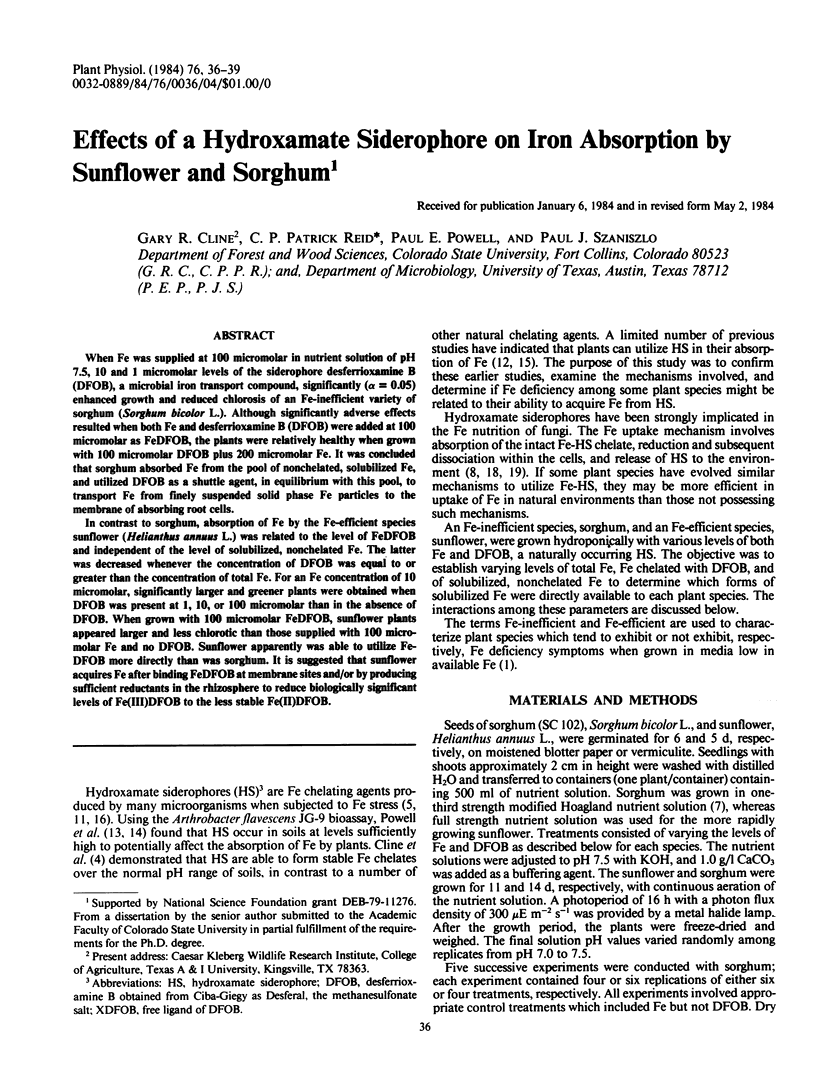

When Fe was supplied at 100 micromolar in nutrient solution of pH 7.5, 10 and 1 micromolar levels of the siderophore desferrioxamine B (DFOB), a microbial iron transport compound, significantly (α = 0.05) enhanced growth and reduced chlorosis of an Fe-inefficient variety of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.). Although significantly adverse effects resulted when both Fe and desferrioxamine B (DFOB) were added at 100 micromolar as FeDFOB, the plants were relatively healthy when grown with 100 micromolar DFOB plus 200 micromolar Fe. It was concluded that sorghum absorbed Fe from the pool of nonchelated, solubilized Fe, and utilized DFOB as a shuttle agent, in equilibrium with this pool, to transport Fe from finely suspended solid phase Fe particles to the membrane of absorbing root cells.

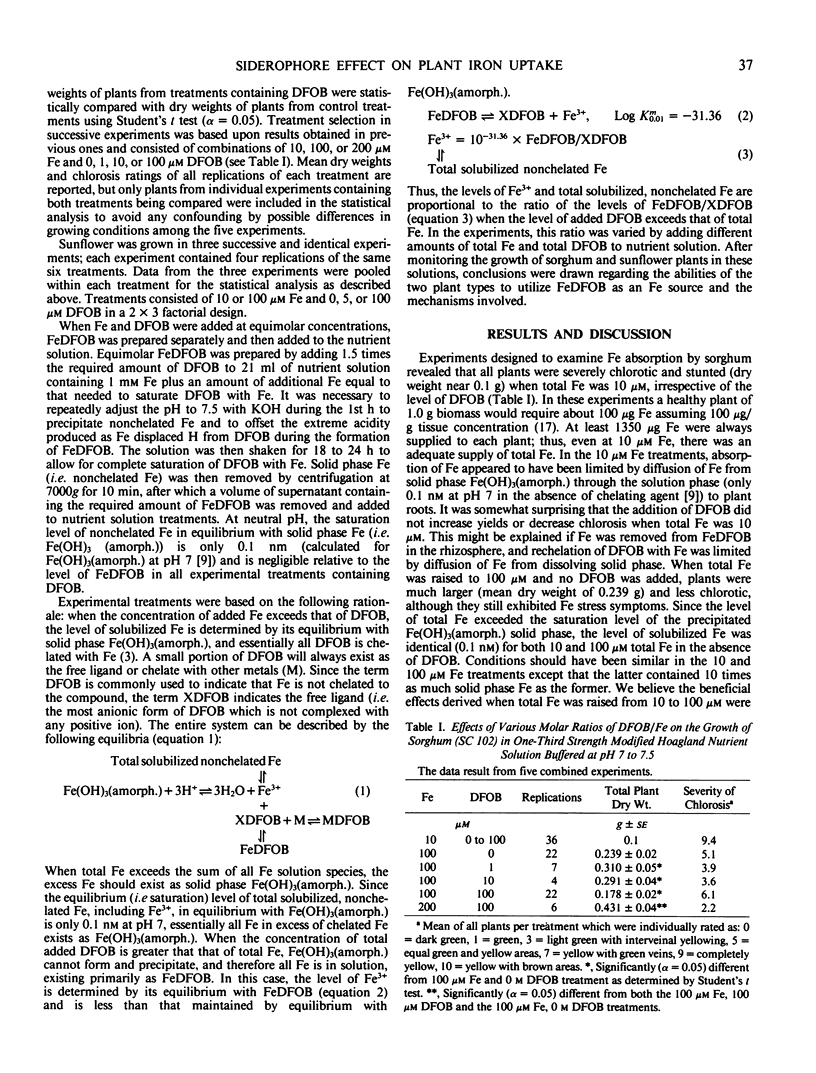

In contrast to sorghum, absorption of Fe by the Fe-efficient species sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) was related to the level of FeDFOB and independent of the level of solubilized, nonchelated Fe. The latter was decreased whenever the concentration of DFOB was equal to or greater than the concentration of total Fe. For an Fe concentration of 10 micromolar, significantly larger and greener plants were obtained when DFOB was present at 1, 10, or 100 micromolar than in the absence of DFOB. When grown with 100 micromolar FeDFOB, sunflower plants appeared larger and less chlorotic than those supplied with 100 micromolar Fe and no DFOB. Sunflower apparently was able to utilize FeDFOB more directly than was sorghum. It is suggested that sunflower acquires Fe after binding FeDFOB at membrane sites and/or by producing sufficient reductants in the rhizosphere to reduce biologically significant levels of Fe(III)DFOB to the less stable Fe(II)DFOB.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chaney R. L., Brown J. C., Tiffin L. O. Obligatory reduction of ferric chelates in iron uptake by soybeans. Plant Physiol. 1972 Aug;50(2):208–213. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong J., Neilands J. B., Raymond K. N. Coordination isomers of biological iron transport compounds. III. (1) Transport of lambda-cis-chromic desferriferrichrome by Ustilago sphaerogena. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974 Oct 8;60(3):1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell P. E., Szaniszlo P. J., Reid C. P. Confirmation of Occurrence of Hydroxamate Siderophores in Soil by a Novel Escherichia coli Bioassay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Nov;46(5):1080–1083. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.5.1080-1083.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe C., Winkelmann G. Kinetic studies on the specificity of chelate-iron uptake in Aspergillus. J Bacteriol. 1975 Sep;123(3):837–842. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.3.837-842.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann G. Metabolic products of microorganisms. 132. Uptake of iron by Neurospora crassa. 3. Iron transport studies with ferrichrome-type compounds. Arch Mikrobiol. 1974 Jun 7;98(1):39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]