Abstract

BACKGROUND

Postpolypectomy syndrome (PPS) is a rare postoperative complication of colonic polypectomy. It presents with abdominal pain and fever accompanied by coagulopathy and elevated inflammatory markers. Its prognosis is usually good, and it only requires outpatient treatment or observation in a general ward. However, it can be life-threatening.

CASE SUMMARY

The patient was a 58-year-old man who underwent two colonic polypectomies, each resulting in life-threatening sepsis, septic shock, and coagulopathy. Each of the notable manifestations was a rapid drop in blood pressure, an increase in heart rate, loss of consciousness, and heavy sweating, accompanied by shortness of breath and decreased oxygen in the finger pulse. Based on the criteria of organ dysfunction due to infection, we diagnosed him with sepsis. The patient also experienced severe gastrointestinal bleeding after the second operation. Curiously, he did not complain of any abdominal pain throughout the course of the illness. He had significantly elevated concentrations of inflammatory markers and coagulopathy. Except for the absence of abdominal pain, his fever, significant coagulopathy, and elevated inflammatory marker concentrations were all consistent with PPS. Abdominal computed tomography and superior mesenteric artery computed tomography angiography showed no free air or vascular damage. Thus, the diagnosis of colon perforation was not considered. The final blood culture results indicated Moraxella osloensis. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and quickly improved after fluid resuscitation, antibiotic treatment, oxygen therapy, and blood transfusion.

CONCLUSION

PPS may induce dysregulation of the systemic inflammatory response, which can lead to sepsis or septic shock, even in the absence of abdominal pain.

Keywords: Postpolypectomy syndrome, Abdominal pain, Sepsis, Gastrointestinal bleeding, Case report

Core Tip: Postpolypectomy syndrome (PPS) is a rare postoperative complication of colonic polypectomy. The prognosis is usually good, and it is characterized by abdominal pain, fever, inflammatory markers, and abnormal coagulation. We report a 58-year-old man who developed life-threatening sepsis or septic shock and gastrointestinal bleeding after colonic polypectomy. Except for the absence of abdominal pain, the patient presented with characteristic PPS symptoms of fever, significant coagulation abnormalities, and elevated inflammatory markers. Final blood culture indicated Moraxella osloensis. This case implies that abdominal pain is not a necessary symptom of PPS, and PPS without abdominal pain may progress to life-threatening sepsis and bleeding.

INTRODUCTION

Postpolypectomy syndrome (PPS) is a rare postoperative complication that occurs several days after colonic polypectomy[1,2]. Patients with PPS may pathologically develop serosal inflammation and coagulopathy because of a transmural burn and focal peritonitis following electrocoagulation of a portion of the bowel wall during polypectomy[3]. Patients with PPS may present with a sudden increase in heart rate (HR), fever, abdominal or lumbosacral pain, and abdominal distention, which makes it similar to bowel perforation, but no perforation occurs. Patients also have significantly elevated concentrations of inflammatory markers and coagulopathy[4]. Despite the good prognosis of most patients, a few patients require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) because of severe hemodynamic instability. Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction syndrome because of a disordered immune response after host infection. Septic shock is classified as a subtype of sepsis, defined as the need for a vasopressor to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥ 65 mmHg despite adequate volume resuscitation, with serum lactate levels > 2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL) (Sepsis-3 definitions)[5]. We present a unique case of PPS that had no abdominal pain but presented with typical manifestations of sepsis and septic shock with gastrointestinal bleeding. This report was written following the CARE reporting checklist.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 58-year-old man was admitted to the department of gastrointestinal surgery of our hospital on November 15, 2021 (day 1) for fecal occult blood that had lasted for > 2 mo.

History of present illness

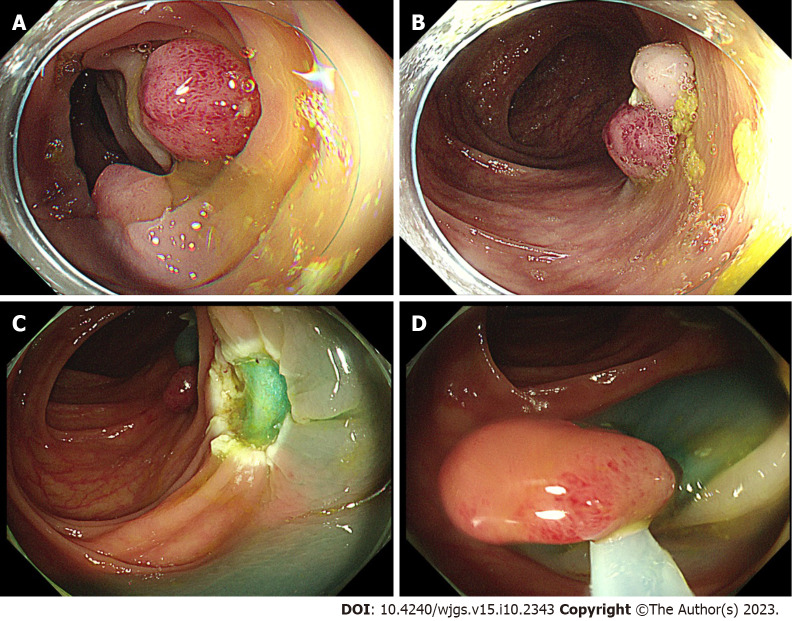

The patient underwent partial endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and electrocoagulation electro resection and cold resection for polyps in the cecum and colon under intravenous anesthesia at 16:30 h on November 17, 2021 (day 3). Several broad-based or pedicled polyps with diameters of 0.5-2.0 cm were observed in the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon during the surgery. We removed these polyps by EMR, cold resection, and electrocoagulation and electro resection (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Clinical findings during colonoscopy. A and B: The first colonoscopy (day 3) showed multiple broad-based or pedicled polyps with diameters ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 cm in the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon; C: The second colonoscopy (day 9) showed multiple ulcerations in the transverse colon and descending colon, which were wounds from the first surgery; D: On the second colonoscopy (day 9), three polyps (0.8-1.2 cm) scattered in the descending and sigmoid colons were removed by endoscopic mucosal resection.

While performing electrocoagulation of the sigmoid polyps, the patient suddenly developed shock, dyspnea, and sweating, and his BP decreased to 79/44 mmHg (MAP 55.67 mmHg), oxygen saturation (SpO2) decreased to 77%, and HR increased to 133 beats/min at 17:10 h. After aggressive treatment in the ICU, the patient was first referred back to the Department of gastrointestinal surgery on November 18, 2021 (day 4) with stable vital signs and normal coagulation function.

The patient underwent colonoscopy-guided polypectomy under intravenous anesthesia at 16:40 h on November 23, 2021 (day 9). During the colonoscopy, several ulcerative foci scattered in the transverse colon and descending colon, as well as the wound of the first surgery, were observed (Figure 1C). Three 0.8-1.2 cm polyps scattered in the descending colon and sigmoid colon were removed by EMR (Figure 1D), and the wound surface was closed with titanium clips. On awakening from anesthesia after surgery at 17:20 h, his BP suddenly decreased to 76/42 mmHg (MAP 53.33 mmHg), HR increased to 133 beats/min, SpO2 dropped to 90%, and he had mental irritability.

History of past illness

He underwent a gastrectomy in 2002 due to gastric ulcers. In September 2021, he received surgical treatment for oral cancer. In September 2020, he was hospitalized in another hospital for oral cancer, and his fecal occult tests were positive. On September 3, 2020, he underwent painless colonoscopy, and several polyps were found in the colon. No adverse events occurred.

Personal and family history

The patient denied any family genetic history.

Physical examination

Vital signs and physical examination changed rapidly with the disease; refer to the “History of present illness” and “TREATMENT” sections for details.

Laboratory examinations

November 17, 2021 (day 3): Blood gas analysis showed pH 7.33 (normal range: 7.35-7.45), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) 37 mmHg (normal range: 35-45mmHg), partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) 211 mmHg (normal range: 60-100mmHg), lactate levels 4.8 mmol/L (normal range: 0.5-1.6 mmol/L), bicarbonate radical concentration 19.5 mmol/L (normal range: 22-26 mmol/L), base excess (BE) 5.8 mmol/L (normal range: -3-3 mmol/L), and potassium ion concentration 2.9 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5-5.0 mmol/L). The PaO2/FiO2 was 221 mmHg (normal range: > 300 mmHg). Blood routine results showed a white blood cell (WBC) count 3.29 × 109/L (normal range: 3.50 × 109-9.50 × 109/L), neutrophil percentage 87.8% (normal range: 40%-75%), and platelet count 142 × 1012/L (normal range: 125 × 1012-350 × 1012/L). The concentrations of the infection-related markers were elevated: procalcitonin (PCT) concentration was 1.66 ng/mL (normal range: 0-0.05 ng/mL) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration was > 5000 pg/mL (normal range: 0-7.0 pg/mL). The severe coagulopathy was characterized by a prothrombin time (PT) 36.2 s (normal range: 11.5-14.5 s), international normalized ratio (INR) 3.6 (normal range: 0.8-1.2), prothrombin activity (PTA) 21% (normal range: 80-120% ), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 69.1 s (normal range: 28-45 s), fibrinogen concentration < 0.6 g/L (normal range: 2.0-4.0 g/L), fibrin degradation product (FDP) concentration > 360 μg/mL (normal range: 0-5.0 μg/mL), D-dimer concentration > 40 μg/mL (normal range: 0-0.55 μg/mL), and antithrombin (AT) III level 69% normal range: 75%-125% ). Blood culture was negative. We found no significant differences in the other laboratory results.

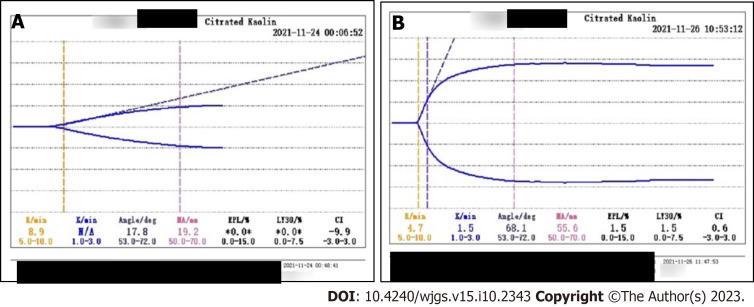

November 23, 2021 (day 9): Blood gas analysis showed pH 7.23, PaCO2 33 mmHg, PaO2 149 mmHg, lactate level 7.1 mmol/L, bicarbonate radical concentration 13.8 mmol/L, BE -12.7 mmol/L, and potassium ion concentration 6.5 mmol/L. PaO2/FiO2 was 186 mmHg. He also had leukocytosis, elevated concentrations of infection markers, and coagulopathy. His WBC count was 12.38 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage was 86.4%, hemoglobin concentration was 84 g/L, platelet count was 192 × 1012/L, PCT concentration was 1.26 ng/mL, and IL-6 concentration was > 5000 pg/mL. The patient progressed to a depletion hypo-coagulable state. His PT was 36.5 s, INR 3.64, PTA 20%, APTT 62 s, fibrinogen concentration < 0.6 g/L, FDP concentrations > 360 μg/ mL, D-dimer concentration > 40 μg/mL, and AT III 65%. Thromboelastography showed a comprehensive coagulation index of -9.9, fibrinogen function α-angle (deg) of 17.8 and K-time exceeding the upper limit, and maximum amplitude (MA) representing the platelet function of 19.2 mm (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Thrombelastogram. A: On day 9, the comprehensive coagulation index was -9.9, fibrinogen function α-angle (deg) was 17.8, K-time exceeded the upper limit, and maximum amplitude representing platelet function was 19.2 mm, showing severe coagulation dysfunction; B: On day 9, the indicators returned to normal.

November 25, 2021 (day 11): WBC count was 20.46 × 109/L, hemoglobin concentration 62 g/L, PCT concentration 5.72 ng/mL, and platelet count and coagulation function were normal (Figure 2B).

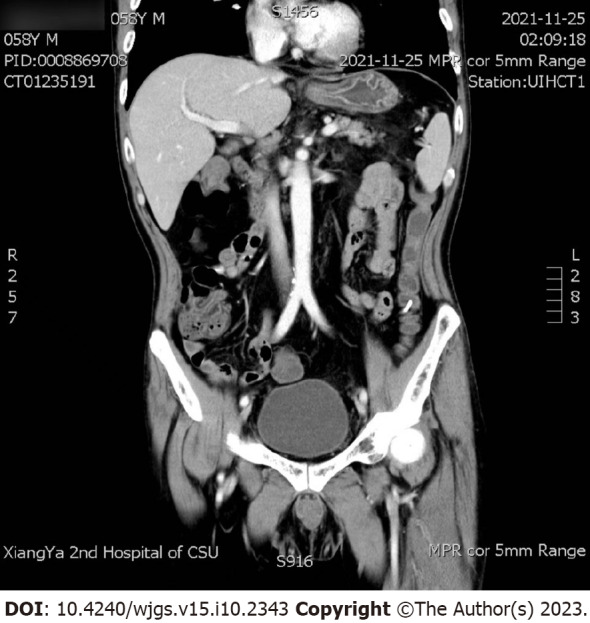

Imaging examinations

November 25, 2021 (day 11): Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and superior mesenteric artery CT angiography showed no intestinal perforation or lumbar lesion (Figure 3), and no vascular damage was observed.

Figure 3.

Abdominal computed tomography and superior mesenteric artery computed tomography angiography. It showed no obvious intestinal perforation or lumbar lesion.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

November 17, 2021 (day 3)

According to the Sepsis-3 definition, organ dysfunction can be identified as an acute change in total sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score 2 points consequent to the infection. The baseline SOFA score can be assumed to be 0 in patients not known to have preexisting organ dysfunction. The patient had a SOFA score of 4 (Respiration 2, Coagulation 1, Cardiovascular 1), combined with an elevated PCT indicating infection, and was therefore diagnosed with sepsis. Based on previous similar cases, we concluded that this patient was consistent with the diagnosis of PPS with sepsis and septic shock.

November 23, 2021 (day 9)

The SOFA score was 5 (Respiration 3, Cardiovascular 2), and elevated PCT and IL-6 indicated infection. It is considered that infection may be associated with endoscopic colonic surgery. Vasoactive drugs are still required to maintain blood pressure after adequate fluid resuscitation. This patient met the diagnostic criteria for septic shock with Sepsis-3.

Blood culture results released on 29 November (samples sent on 23 November) indicated Moraxella osloensis (M. osloensis). Based on previous similar cases, we concluded that this patient was consistent with the diagnosis of PSS and had sepsis and septic shock.

TREATMENT

November 17, 2021 (day 3)

We discontinued the surgery immediately and gave high-flow oxygen for respiratory support (FiO2 100%, flow 50 L/min). After fluid resuscitation and oxygen treatment, SpO2 recovered to 98%. However, the patient was still in shock with no return of consciousness with a BP of 70/45 mmHg (MAP 53.33 mmHg) and HR of 122 beats/min and was transferred to the ICU at 17:44 h. Fluid resuscitation and volume assessments were performed. At 18:00 h, the patient regained consciousness with no complaints of abdominal pain or abdominal distension. His BP recovered to 115/66 mmHg without administration of vasoactive drugs, and his HR was 115 beats/min, respiratory rate (RR) was 25 breaths/min, SpO2 was 95% (nasal catheter, 3L/min), and temperature was 38.9 °C. Cefoxitin (2.0 g Q12H for 1 d) was administered intravenously and plasma transfusion and fluid resuscitation were performed immediately.

November 23, 2021 (day 9)

We gave high-flow oxygen for respiratory support (FiO2 80%, flow 50 L/min). We initially suspected anaphylactic shock and immediately administered antiallergic therapy and fluid resuscitation. At 17:42 h, the patient regained consciousness, but the shock, fever (39 °C), and chills persisted. We transferred him to the ICU at 18:00 h. Even with adequate fluid resuscitation, vasoactive drugs are still required to maintain MAP > 65 mmHg. As before, the patient had no abdominal pain. In addition to these tests, we also performed blood culture.

Antiallergic treatment did not improve the condition of the patient. At 22:00 h, the patient released 200 mL of dark red bloody stools. We administered cefoxitin (2.0 g Q12H for 3 d) intravenously and infused plasma, cryoprecipitate, and red blood cells during fluid resuscitation. His vital signs were stable and gastrointestinal bleeding ceased on November 25, 2021 (day 11).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

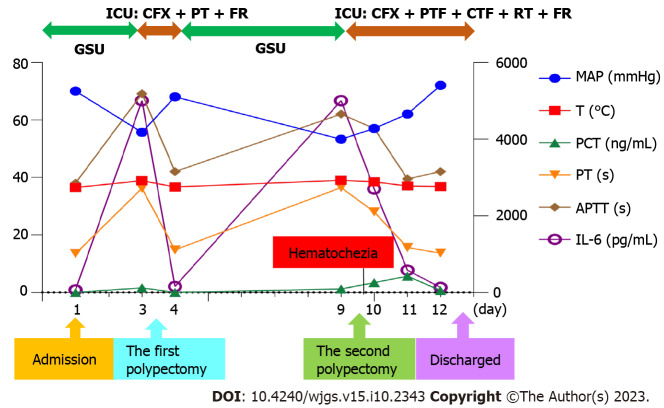

The patient was discharged on November 26, 2021 (day 12). He said that he would not have polypectomy in the future and thanked us for our timely rescue. The clinical course is summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Clinical course with laboratory results and treatment. GSU: Gastrointestinal surgery unit; ICU: Intensive care unit; CFX: Cefoxitin; PTF: Plasma transfusion; FR: Fluid resuscitation; CTF: Coprecipitation transfusion; RT: Red cells transfusion; MAP: Mean arterial pressure; T: Daily maximum body temperature; PCT: Procalcitonin; PT: Prothrombin time; APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time; IL-6: Interleukin 6.

DISCUSSION

This is a report of a unique case of a patient diagnosed with PPS without abdominal pain. He developed life-threatening sepsis and septic shock and gastrointestinal bleeding. He experienced the above conditions twice and improved rapidly after active antibiotic treatment, fluid resuscitation, and blood transfusion in the ICU.

PPS is a rare complication after colonic polypectomy, with an incidence of approximately 0.14%-2.9%[6,7]. It has also been reported after small bowel polypectomy[8]. PPS can present with local abdominal pain, abdominal muscle tension, rebound pain, and local peritonitis. Some patients also develop fever and leukocytosis within 6 h to 5 d after surgery[9,10]. Organ failure and sepsis are rarely reported[2,3]. The etiology is transmural inflammation, localized peritonitis, and coagulopathy caused by electrical coagulation that burns the local intestinal wall. For colonic polypectomy, PPS occurs when the current passes through the mucosa into the muscularis propria and serosa layer without perforation[11].

Hypertension, large lesions (> 2 cm), and in the ascending colon or cecum, and non-polypoid lesions are independent risk factors for PPS. Hypertension can increase the risk of PPS by three times[7,9,12]. Larger polyps require high amounts of energy and longer duration of electrocoagulation, as well as ligation of more normal mucosa[13]. A meta-analysis showed that the prophylactic use of antibiotics reduces the risk of PPS[14].

PPS shows several features on CT, including severe wall thickening and heterogeneous enhancement patterns, wall defects filled with fluid, surrounding fat infiltration, and the absence of extraluminal air. In addition, colonic segments are usually longer and thicker for PPS than for colon perforations on CT[6]. Patients with perforated colons can have different presentations depending on the location of the lesion. The perforation of a colon segment in the abdominal cavity, such as the mesentery, sigmoid colon, and cecum, is more likely to lead to free air and fluid in the abdominal cavity, while perforations of the ascending colon, descending colon, and rectum are more likely to lead to extraperitoneal air and fluid[9].

The prognosis of PPS is good[7]. Patients usually have pain, fever, and other mild abdominal inflammation symptoms, which disappear within 2-5 d, and they only require outpatient or ordinary infusion and symptomatic treatment. Antibiotic use for Gram-negative and anaerobic pathogens depends on the overall status of the patient[1,7,9,10]. There are few reports that full-thickness burns in patients may progress to delayed perforation and require emergency surgical exploration[12].

There were three noteworthy features of this case. First, shock occurred quickly during or after polypectomy. There were significant leukocytosis, elevated concentrations of inflammatory markers, and coagulopathy. In previous reports, PPS occurred at least 6 h after polypectomy[10]. Secondly, there was no abdominal pain during the course of the disease, which is different from previous reports[1,9,10,12]. Third, systemic inflammation was more severe than local inflammation. CT on the day 3 after the second polypectomy did not show extraluminal air or intestinal wall edema. However, the significantly higher concentrations of inflammatory markers, leukocytosis, shock, and SOFA score indicated a systemic inflammatory response. This case report, however, has one limitation. We did not perform abdominal CT immediately on the day of shock. The condition of the patient was critical, and he needed immediate rescue and could not leave the ICU for a CT scan.

We analyzed the causes of sepsis and septic shock in this patient with PPS as follows. The patient had multiple broad-based polyps, with the largest diameter of 2 cm. Multiple polyps were removed during each polypectomy, resulting in large intestinal mucosal wounds and severe electrocoagulation injuries. Multiple ulcers after polypectomy may facilitate bacterial entry to the circulation and sepsis. Blood culture results released on November 29 (samples sent on November 23) indicated M. osloensis. At the time of submitting the blood culture sample, the patient was suffering from a second bout of sepsis and developed septic shock. The Gram-negative aerobic bacterium M. osloensis is an opportunistic pathogen, and may cause infection in immunosuppressed adults and non-immunodeficient children[15]. It has previously been reported to cause brain tissue infection in patients with glioma[16]. M. osloensis can cause bacteremia in immunodeficient patients[17]. There was also a young patient on long-term peritoneal dialysis who developed diffuse peritonitis. M. osloensis was isolated from the peritoneal fluid, and eventually recovered after anti-infective treatment with cefazolin[18]. The patient had a history of oral cancer and was likely to have sepsis due to an opportunistic infection caused by M. osloensis. In summary, the patient’s symptoms and laboratory results were in line with the diagnosis of local injury and infection of the intestinal wall after colonoscopic polypectomy, leading to bacterial entry into the blood and sepsis, followed by inflammatory storm, coagulation damage and shock. This was a particularly serious and life-threatening case of PPS.

Physicians should be aware of the risk of severe PPS with sepsis and gastrointestinal bleeding after polypectomy. The absence of abdominal pain does not rule out a diagnosis of PPS. At the same time, removing too many polyps at one time should be avoided, and caution should be exercised, given the risk of PPS, when removing polyps at dangerous sites, such as the ascending colon and cecum.

CONCLUSION

Abdominal pain is not a necessary symptom of PPS. PPS without abdominal pain may also lead to life-threatening sepsis and bleeding. When there is severe coagulopathy, it is necessary to stay alert for gastrointestinal bleeding. Physicians should take precautions against sepsis and septic shock caused by PPS. We recommend that patients with severe PPS should be transferred to the ICU for prompt treatment.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: We obtained the patient's written informed consent to disclose his case. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that his name will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no competing financial interests for this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: July 20, 2023

First decision: August 5, 2023

Article in press: September 5, 2023

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kenzaka T, Japan; Nasa P, United Arab Emirates S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

Contributor Information

Fang-Zhi Chen, Department of Gastroenterology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China, Hengyang 421001, Hunan Province, China.

Lin Ouyang, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410011, Hunan Province, China.

Xiao-Li Zhong, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410011, Hunan Province, China.

Jin-Xiu Li, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410011, Hunan Province, China.

Yan-Yan Zhou, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410011, Hunan Province, China. iamzhouyanyan@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Kus J, Haque S, Kazan-Tannus J, Jawahar A. Postpolypectomy coagulation syndrome - an uncommon complication of colonoscopy. Clin Imaging. 2021;79:133–135. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhuang ZF, Ye ZH, Zhong ZS, He GH, Wang J, Huang SP. A case report of a post-polypectomy syndrome with severe sepsis and organ dysfunction. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:488–492. doi: 10.21037/apm.2020.01.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirasawa K, Sato C, Makazu M, Kaneko H, Kobayashi R, Kokawa A, Maeda S. Coagulation syndrome: Delayed perforation after colorectal endoscopic treatments. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i12.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy I, Gralnek IM. Complications of diagnostic colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, and enteroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30:705–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin YJ, Kim YH, Lee KH, Lee YJ, Park JH. CT findings of post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome and colonic perforation in patients who underwent colonoscopic polypectomy. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha JM, Lim KS, Lee SH, Joo YE, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim HG, Park DI, Kim SE, Yang DH, Shin JE. Clinical outcomes and risk factors of post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective, case-control study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:202–207. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhandari A, Kalmaz D. Jejunal post-polypectomy syndrome. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E133–E134. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson BC, Myers JJ, Laczek JT. Postpolypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome: a mimicker of colonic perforation. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:687931. doi: 10.1155/2013/687931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SY, Chang CF, Chiang ML, Tseng WC. Postpolypectomy Electrocoagulation Syndrome: A Rare Complication of Colonoscopic Polypectomy Mimicking Colonic Perforation. J Emerg Med. 2021;60:e127–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Johnston TK. Procedural success and complications of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:307–314. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levenson RB, Troy KM, Lee KS. Acute Abdominal Pain Following Optical Colonoscopy: CT Findings and Clinical Considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:W33–W40. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jehangir A, Bennett KM, Rettew AC, Fadahunsi O, Shaikh B, Donato A. Post-polypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome: a rare cause of acute abdominal pain. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2015;5:29147. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v5.29147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Regina D, Mongelli F, Fasoli A, Lollo G, Ceppi M, Saporito A, Garofalo F, Di Giuseppe M, Ferrario di Tor Vajana A. Clinical Adverse Events after Endoscopic Resection for Colorectal Lesions: A Meta-Analysis on the Antibiotic Prophylaxis. Dig Dis. 2020;38:15–22. doi: 10.1159/000502055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabbuso T, Defourny L, Lali SE, Pasdermadjian S, Gilliaux O. Moraxella osloensis infection among adults and children: A pediatric case and literature review. Arch Pediatr. 2021;28:348–351. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strojnik T, Kavalar R, Gornik-Kramberger K, Rupnik M, Robnik SL, Popovic M, Velnar T. Latent brain infection with Moraxella osloensis as a possible cause of cerebral gliomatosis type 2: A case report. World J Clin Oncol. 2020;11:1064–1069. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i12.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MY, Kim MH, Lee WI, Kang SY. Bacteremia Caused by Moraxella Osloensis: a Fatal Case of an Immunocompromised Patient and Literature Review. Clin Lab. 2021;67 doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2020.200459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada A, Kasahara K, Ogawa Y, Samejima K, Eriguchi M, Yano H, Mikasa K, Tsuruya K. Peritonitis due to Moraxella osloensis: A case report and literature review. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25:1050–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]