Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are vital elements of the mammalian immune system that function by recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), bridging innate and adaptive immunity. They have become a prominent therapeutic target for the treatment of infectious diseases, cancer, and allergies, with many TLR agonists currently in clinical trials or approved as immunostimulants. Numerous studies have shown that conjugation of TLR agonists to other molecules can beneficially influence their potency, toxicity, pharmacokinetics, or function. The functional properties of TLR agonist conjugates, however, are highly dependent on the ligation strategy employed. Here, we review the chemical structural requirements for effective functional TLR agonist conjugation. In addition, we provide similar analysis for those that have yet to be conjugated. Moreover, we discuss applications of covalent TLR agonist conjugation and their implications for clinical use.

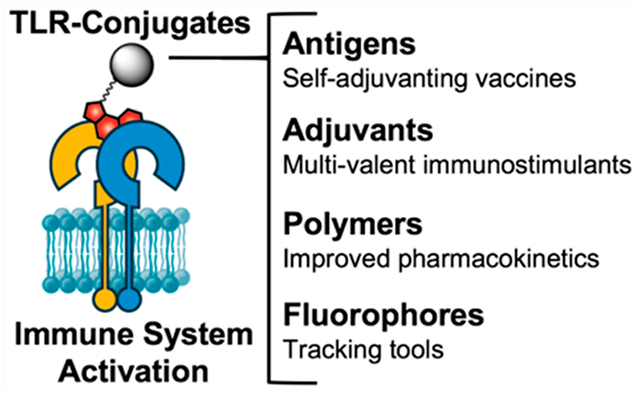

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The immune system is vital in protecting the body against infectious disease and cancers. Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation is the first step in stimulating the immune system to respond to disease.1 As a consequence, TLRs are the target of several therapeutics, including vaccines,2 cancer immunotherapies,3 and autoimmune disease treatments.4,5 Activators of TLR signaling, TLR agonists, are powerful immunostimulants due to their ability to drive innate and acquired immunity and are therefore sought after as adjuvants in vaccines.6 However, because they elicit strong immune reactions, administration of TLR agonists can have toxic side-effects in vivo.7–9

To mitigate these adverse effects, TLR agonists can be covalently conjugated to an antigen. This ensures simultaneous delivery of antigen and adjuvant to the same antigen presenting cell, which directs the response toward the antigen, thereby lowering the required dose for an effective immune response.10,11 These self-adjuvanting vaccines induce stronger humoral and cellular immune responses and are less toxic than vaccines comprising coadministered antigen and adjuvant.10 TLR agonists have also been conjugated to polymers,12–14 solid particles,15–17 or phospholipids18–20 to beneficially influence the compound’s drug properties.

The benefits of TLR agonist conjugation can only be achieved if the conjugation does not perturb the interaction between the agonist and the receptor. Therefore, effective strategies are required that facilitate TLR agonist conjugation with retention of, or improved, TLR agonist potency. Here, we provide a review of the chemical requirements for successful TLR agonist conjugation strategies that have been employed, and provide suggestions for alternative ligation strategies for existing TLR agonists and insight for agonists that have yet to be conjugated.

TLRs—NOMENCLATURE AND FUNCTION

Toll-like receptors are a class of transmembrane pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Their role is to recognize conserved molecular components of pathogens called “pathogen-associated molecular patterns” (PAMPs) as well as cellular damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).21 The receptors are predominantly expressed in immune cells and show distinct expression patterns across different cell types.22

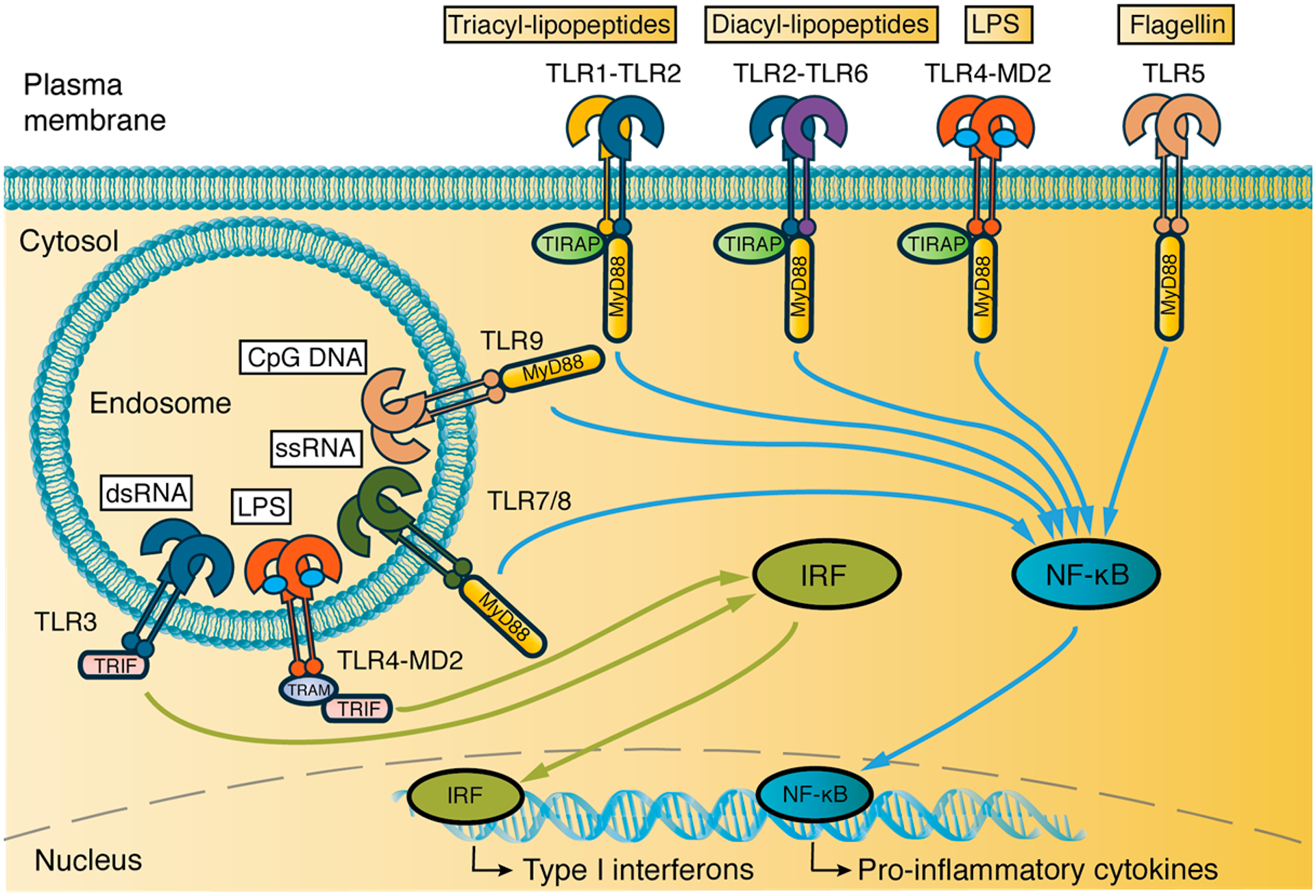

The human TLR family comprises 10 functional TLRs that are expressed both on the cell surface (TLR1, 2, 4, 5, and 6) and intracellularly in endosomal compartments (TLR 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9).23,24 The cellular localization of TLRs reflects the origin of the ligand it is responsible for detecting (Figure 1). TLRs found at the cell surface respond to extracellular components of pathogens, including lipoproteins (TLR1, 2, and 6), lipopolysaccharides (TLR4), and bacterial flagellin (TLR5). Endosomal TLRs recognize components from the intracellular compartments of pathogens, such as double-stranded RNA (dsRNA, TLR3), single-stranded RNA (ssRNA, TLR7 and 8), and unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) DNA (TLR9).25 Although the role and natural ligand for human TLR10 is not yet fully understood, it is thought to be a negative regulator of TLR signaling.26–28 Binding of ligands to TLRs induces homo- or heterodimerization of TLR receptors and subsequent downstream signaling through two distinct pathways, the MyD88-dependent (TLRs 1, 2, and 4–9) and TRIF-dependent pathway (TLR3 and 4), generally mediating inflammatory and antiviral responses, respectively.29,30

Figure 1.

Cellular location of TLRs, their ligands, and signal transduction pathways. TLRs 1, 2, 6, 4, and 5 are located on the plasma membrane and signal, together with endosomal TLRs 7, 8, and 9, in a MyD88-dependent manner. The MyD88 pathway leads to NF-κB translocation to the nucleus and, ultimately, production of inflammatory cytokines. Activated TLR4 is endocytosed and, together with endosomal TLR3, signals through the IRF pathway, leading to Type I interferon production. MD2, TRAM, and TIRAP are adaptor proteins.

TLRs are crucial for their role in the innate immune system in fighting infection. They are responsible for the initial response to pathogens and their activity drives the generation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Innate immunity begins with the recognition of PAMPs through TLRs by antigen presenting cells (APCs), mainly dendritic cells (DCs) in the peripheral tissues.23 Binding of TLR ligands on dendritic cells initiates a downstream signaling cascade that initiates DC maturation. This process is characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12), up-regulation of costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, and CD86), increased antigen-presenting capacity, and DC migration from the peripheral tissues to draining lymph nodes.23 There, antigen presenting DCs stimulate naïve T-cells which begins the adaptive immune response. B-cells also express TLRs and present antigen upon activation, resulting in antibody production specific for the encountered antigen. Since T- and B-cell maturation is influenced by TLR, costimulatory, and cytokine signaling, TLR agonists play an important role in establishing the type of cellular and humoral immune response that is generated.

TLR AGONIST CONJUGATES

Due to their pivotal role in both the innate and adaptive immune system, agonists for TLRs have emerged as therapeutic agents, including as adjuvants in vaccines. Adjuvants function by activating immune cells exposed to antigen. Thus, the characteristics of efficacious adjuvants follow different design principles than traditional drugs. As reviewed by Wu,31 an effective adjuvant should have a higher retention time at the site of administration to promote local immune system stimulation and prevent potentially harmful, off-target inflammation.

In their review, Xu and Moyle32 state that direct conjugation of TLR agonists to antigen fulfills these requirements by ensuring codelivery of antigen and adjuvant to immune cells. This enhances the generation of antigen-specific immune responses and prevents wasted inflammation.33 In addition, TLR agonists-conjugates have been used as chemical tools to study the role of TLR signaling in immune responses, which was recently reviewed by Oosenbrug and co-workers.34 However, conjugation of TLR to antigens or other molecules requires thoughtful consideration in the choice of TLR agonist, chemical linkage strategy, and site of conjugation. Here, we review conjugation of TLR agonists from a chemistry perspective to provide insight for future applications.

CONJUGATION STRATEGIES

TLR2.

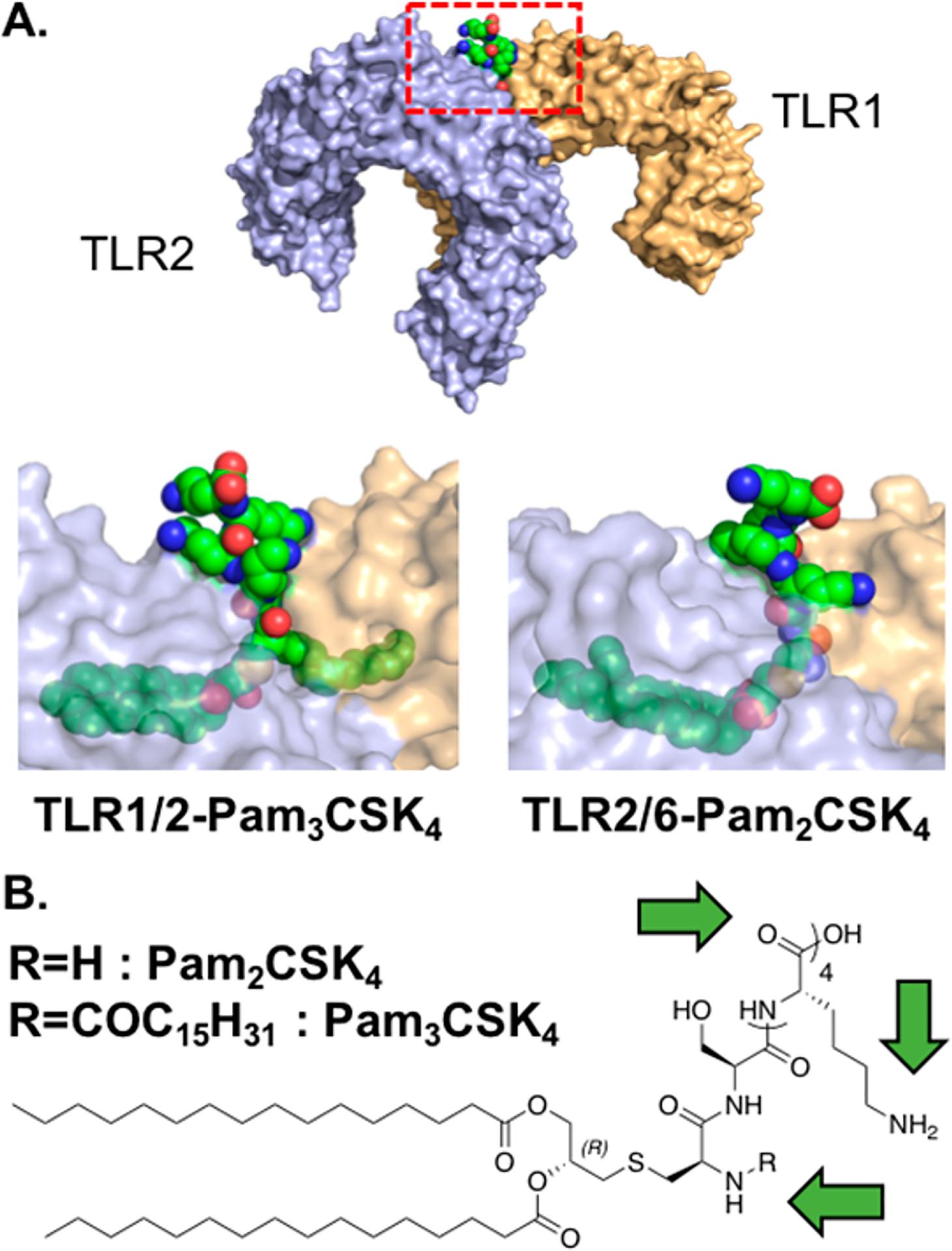

The TLR2 subfamily is unique among TLRs in that it forms heterodimers with either TLR1 or TLR6 instead of homodimers (Figure 2A). TLR2 is involved in the recognition PAMPs from a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi.35 The prototypical agonists to TLR2, however, are a class of bacterial di- or triacylated lipoproteins and lipopeptides and their synthetic analogues with N-terminal di- or tripalmitoylated cysteine residues (Pam2Cys, Pam3Cys, respectively) (Figure 2B). Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys bind TLR2 via two ester bound palmitoyl chains, whereas N-terminal acylation determines TLR1 or TLR6 specificity; an N-terminal fatty acid recruits TLR1 and a free N-terminal amine recruits TLR6 (Figure 2A).36 They often contain the peptide-motif SK4, which enhances the agonists’ adjuvanticity and water-solubility.37 Isomerically pure R-epimers of Pam2CSK4 (EC50: <1 nM) and Pam3CSK4 (EC50: 5 nM) are more potent TLR2 agonists than their racemic mixtures (EC50: 1 nM and 20 nM, respectively), due to lower activity of the S-epimers.38,39 Because of their ability to induce robust maturation of DCs and effective humoral and cellular responses,40 these lipopeptides have been employed as adjuvants in many vaccine studies, even predating the discovery of TLRs.41

Figure 2.

TLR2 agonists bind dimers of either TLR2-TLR1 or TLR2-TLR6. (A) Crystal structure of human TLR2-TLR1-Pam3CSK4 (PDB: 2Z7X). Red rectangle represents the area of the zoomed view of Pam3CSK4 binding to TLR2-TLR1. The analogous view from the TLR2-TLR6-Pam2CSK4 crystal structure is also shown (PDB: 5IJC). In both cases, the peptide C-terminus is solvent exposed. TLR2 is shown in blue, TLR1 and TLR6 are in orange, and lipopeptides are in green. TLRs in the zoomed view are shown at 40% transparency. (B) Chemical structure of Pam2CSK4 and Pam3CSK4. Green arrows highlight sites of conjugation.

Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys and their derivatives are the TLR2 agonists most often found in bioconjugates due to their well-defined chemical structure, ease of production, and the absence of natural endotoxins (Table 1). One exception is the TLR2-TLR6 ligand, lipoteichoic acid (LTA), a major component of the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall.42 LTA was conjugated to both CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) 1826,43,44 a TLR 9 agonist, and to the cell surface of Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells45 via a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) linker. In both instances, conjugation of LTA was achieved by amide bond formation of the primary amines of side-chain D-alanines with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters on heterobifunctional linkers. Despite its high potency, LTA has not been used in bioconjugation as extensively as Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys, as endotoxin free LTA is difficult to produce and is therefore expensive. Moreover, the aforementioned conjugation strategies for LTA yield a mixture of high molecular weight, structurally diverse LTA-conjugates. Conversely, Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys are synthetically accessible and their conjugates can be made structurally homogeneous.

Table 1.

Overview of TLR1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 Agonist Conjugates

| TLR | agonist | conjugation site | conjugation chemistry | conjugated to | refa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1-TLR2 | Pam3Cys | C-terminus cysteine | SPPS, NCL, CuAAC | Peptide, glycopeptide | 132,166,49,52,54 |

| Pam3CSK4 | C-terminus lysine | SPPS, thioether bond | Peptide, glycopeptide | 39,48,50,55 | |

| ℰ-NH2 group lysine SKKKK | CuAAC | Glycopeptide antigen | 167 | ||

| Amplivant | C-terminus lysine | SPPS | Peptide | 64 | |

| TLR2b | Lipoamino acids | N- and C-terminus | SPPS | Peptide and glycopeptide antigens | 69,132,168–170 |

| TLR3 | Poly(I:C) | NH2 of any cytosine | Bisulfite catalyzed transamination | Polysaccharide | 78 |

| 5’ termini | Phosphoramidate coupling | Nanoparticles | 82,83 | ||

| TLR4 | MPLA | Reducing end anomeric center | Amide, CuAAC | Oligosaccharide | 98–100,102,101,171,172 |

| Nonreducing end 6’ position | CuAAC | Oligosaccharide | 101 | ||

| Any free –OH group | Carbamate | Protein | 97 | ||

| Pyrimidoindole | Carboxamide group | Amide | Polymer, TLR7/8- and 9 agonists | 13,43,107 | |

| TLR5 | Flagellin | N- or C-terminus, or D3 domain | Fusion proteins | Various proteins | Review32 |

| TLR2-TLR6 | Pam2Cys | C-terminus | SPPS, amide, CuAAC | Polymers, peptide, glycopeptide, TLR7- and NOD2 agonists | 49,132,173–177 |

| N-terminus cysteine | Amide | Fluorophore, chelating agent | 60 | ||

| MALP-2 | C-terminus | Amide | Glycopeptide | 62 | |

| Pam2CSK4 | C-terminus lysine | Amide, SPPS | TLR7 and 9 agonists | 44,173,178 | |

| ℰ-NH2 of lysine SKKKK | Amide | TLR7 agonist | 173 | ||

| N-terminus cysteine | Thiourea, carbamate bond | Fluorophore, photocage | 178,108 | ||

| LTA | NH2 of any d-alanine | Amide | LLC cells, TLR9 agonist | 45,45 |

References are clustered and ordered by conjugation chemistry.

TLR2 ligands for which the coreceptor is unknown.

Triacylated TLR2-TLR1 agonists Pam3Cys and Pam3CSK4 have been used extensively as conjugates to create self-adjuvanting vaccines. For instance, Pam3Cys on the N-terminus of N. meningitidis lipoproteins greatly enhances the humoral response to Trumenba, an FDA approved, self-adjuvanting N. meningitidis vaccine.46,47 Pam3Cys and its derivatives are readily synthesized, structurally well-defined, and commercially available, and do not suffer from the drawbacks associated with LTA. Conjugation with these compounds mainly proceeds through the C-terminal carboxyl group to avoid perturbation of N-terminal lipid interactions with the receptors (Figure 2B). The incorporation of Pam3Cys and Pam3CSK4 into peptide-based vaccines can easily be achieved through standard solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), placing Pam3Cys at the N-terminus of the peptide. Jung and co-workers were the first to apply this strategy for the synthesis of a peptide-based antigen-adjuvant conjugate.41 Conjugation of Pam3Cys to peptide antigens greatly increases antigen uptake, processing, and presentation48 and leads to enhanced humoral41,49 and cellular50 immune responses. Zeng et al.51 explored how the positioning of Pam3Cys in a peptide-conjugate affects the conjugate’s pharmacodynamic and immunogenic properties. Placing Pam3Cys in the middle of the peptide sequence dramatically increased the conjugate’s solubility and its ability to induce epitope-specific antibodies compared to terminally conjugated Pam3Cys, Similar results were obtained for TLR2-TLR6 agonist Pam2Cys,51 providing a powerful alternative to linear conjugation of lipopeptide TLR2 agonists.

Preparation of glyco(lipo)peptide conjugates of Pam3Cys via SPPS has proven difficult. Issues with separation of the glyco(lipo)peptide conjugate after resin cleavage49 and lack of orthogonality between carbohydrate deprotection reagents and palmitoyl esters have lead to alternative, convergent synthesis strategies. Several methods to create multicomponent vaccines that contain the tumor-associated carbohydrate antigen (TACA) MUC1, a T-helper epitope, and Pam3Cys have been reported. The Boons lab has employed native chemical ligation (NCL)49,52 to sequentially conjugate TACA MUC1 to a T-helper peptide epitope and Pam3CSK4. Other approaches involve functionalization of the C-terminus of Pam3Cys with a functional handle, such as alkynes,53,54 a bromo- or iodoacetyl group,55 or a pentafluorphenyl-activated ester,56,57 followed by conjugation to peptides and glycopeptide. Together, these examples show that Pam3Cys retains its potency in conjugates and that its conjugation is relatively straightforward in peptide-based conjugates, but more demanding in glycopeptide conjugates.

Conjugates of Pam3Cys can suffer from poor solubility in aqueous solutions and can therefore be difficult to dose and formulate in vaccines.51 Pam2Cys, a synthetic analogue of the N-terminal lipopeptide motif of MALP-2, has a free amino group in place of the N-terminal palmitoyl chain in Pam3Cys resulting in improved solubility characteristics and increased potency toward splenocytes58 and macrophages.59 The free amino group of Pam2Cys has also been used as a conjugation handle. After introducing a PEG spacer at the N-terminus, Vagner and co-workers conjugated relatively bulky functionalities, such as a chelating agent and fluorescent dyes, the N-terminal amine of Pam2Cys while retaining relatively high TLR2-TLR6 potency.60 In contrast, conjugation of photocage 2-(2-nitrophenyl)propyl chloroformate to the N-terminal primary amine without a spacer dramatically decreases the activity of Pam2CSK4.61 These results suggest that the N-terminus of Pam2Cys can be used for conjugation, but that a chemical spacer may be necessary to retain potency toward TLR2-TLR6. Similar to Pam3Cys, conjugation of Pam2Cys can also be accomplished by C-terminal conjugation, as was done in a conjugate of MALP-2 and MUC-1.62

Many structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies into Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys have been performed in order to optimize their adjuvant properties. These studies have resulted in several TLR2 agonist analogues with interesting chemical and immunological properties, but some of these have not yet been used in bioconjugates. By replacing the N-terminal palmitoyl amide-linkage of Pam3Cys for a urea-linkage, Willems and co-workers synthesized a Pam3Cys analogue called Upam (trademarked by Isa pharmaceuticals as Amplivant) that was shown to be a stronger inducer of DC maturation than Pam3Cys.63 Analogous to Pam3Cys, Amplivant was C-terminally conjugated to a human papillomavirus (HPV) synthetic long peptide (SLP) vaccine and enhanced HPV antigen-specific cellular immune responses in ex vivo stimulated cervical tumor material.64 Similarly, Wu et al. have synthesized a Pam3Cys analogue with amide-linked palmitoyl chains (SUP3) and showed it was a superior adjuvant in an in vivo tumor challenge model.65 Both of these Pam3Cys analogues benefit from resistance to esterases, which is hypothesized to contribute to their adjuvanticity.65 Although SUP3 has not been used in antigen-conjugates so far, it could be an excellent adjuvant for use in self-adjuvanting vaccines and perhaps even superior to Pam3Cys. Alternatively, Salunke et al. have reported on potent monopalmitoylated lipopeptide analogues specific to human TLR2.66 These analogues are simpler in structure and synthetically more accessible than Pam3Cys, but have not been used in conjugates as of yet despite their attractive properties. We suggest that any conjugation should proceed through the C-terminus, analogous to conjugations of Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys.

An important consideration for the conjugation of lipopeptide TLR2 agonists are the biophysical effects accompanying the hydrophobic lipid chains. PamCSK4, Pam2CSK4, and Pam3CSK4 can self-assemble into micelles in aqueous solution.67 These self-assembly characteristics have been exploited in self-adjuvanting vaccines where lipopeptides are used as both adjuvant and delivery vehicle. Moyle et al. created multiple group A Streptococcus (GAS) vaccines that contained Pam2Cys, Pam3Cys, or lipoamino acids, lipidated α-amino acids that are believed to activate TLR2.68,69 These compounds self-assembled into nanoparticles of a suitable size (20–200 nm) for passive transport to the draining lymph nodes, which enhanced production of antigen-specific IgG antibodies in vivo.68,69 Moreover, micellar self-assembly of TLR2 activating lipoproteins in N. meningitidis vaccine Trumenba is thought to increase the stability of the lipoprotein antigens.46 However, the self-assembling nature of lipopeptide TLR2 agonists can differ between bioconjugates of different chemical composition. Thus, the biophysical characteristics of a specific lipopeptide-conjugate should be considered as these interactions may affect function.

An alternative to lipopeptide TLR2 agonists are a group of nonlipid TLR2-TLR1 agonists, which were discovered by Guan et al. using high-throughput screening of a chemical library.70 Structurally distinct from lipopeptide agonists, these synthetically accessible small molecules display selective potency toward TLR2-TLR1 at concentrations as low as 30 nM, with some of them being selective for either human or mouse TLR1-TLR2. The small molecules have not yet been used in bioconjugates, nor is there any information available on SAR or binding characteristics. Thus conjugation with these agonists would be more exploratory. However, due to their small molecule nature, these TLR2-TLR1 agonists could find use in conjugate applications in which lipopeptide bulk or hydrophobicity would be problematic.

Both large and small molecule agonists have been described for TLR2. In considering a conjugation strategy, the palmitoylated peptide family offers appealing aspects of processability with the C-terminus providing a viable target for most bioconjugation methods. However, biophysical aggregation must be considered. Future work might explore novel ligands containing more simple, hydrophilic chemical motifs to improve accessibility and enhance solubility while avoiding systemic immune activation.

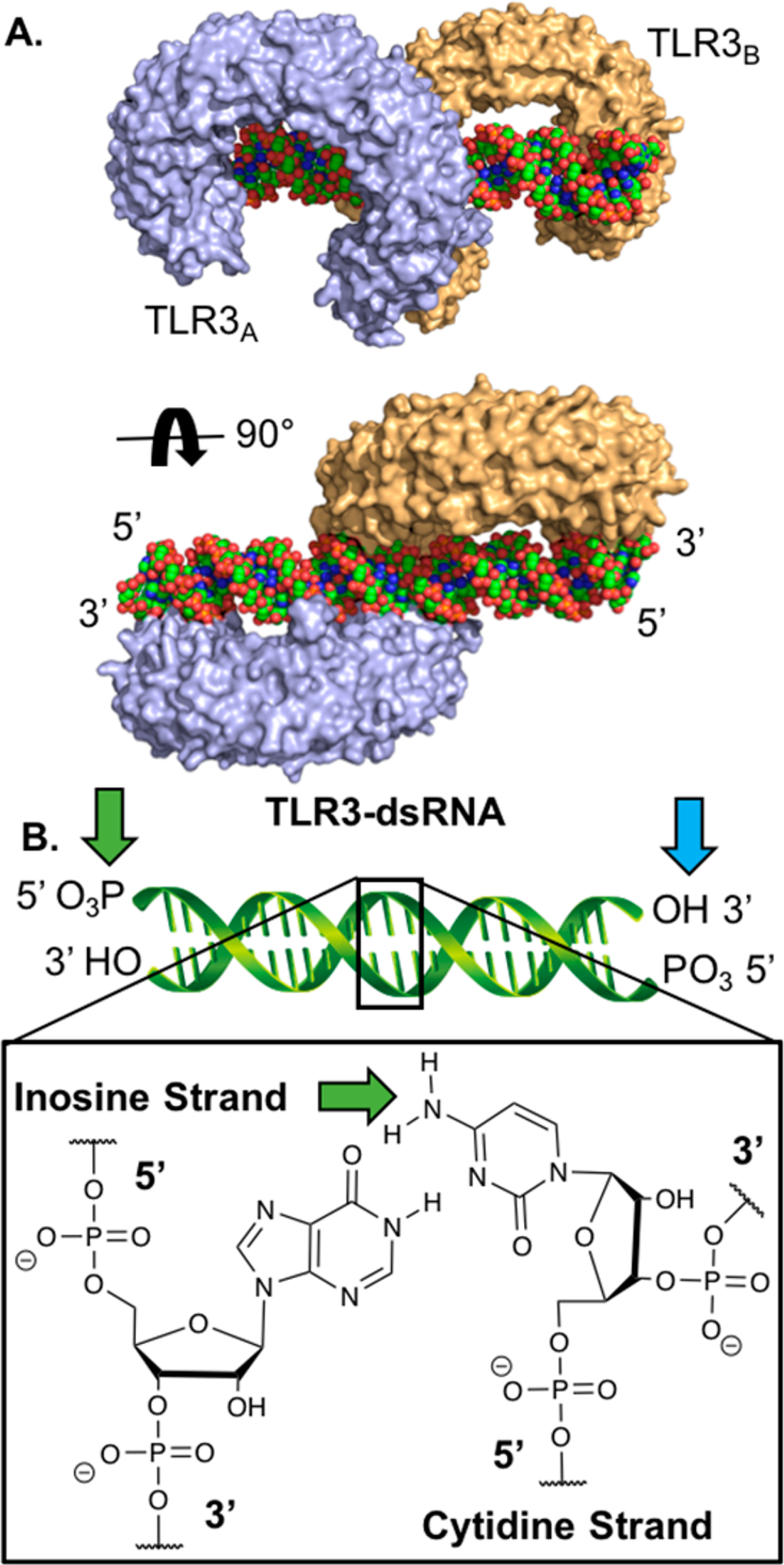

TLR3.

TLR3 is an endosomal TLR that senses the negatively charged backbone of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) that is an intermediate in the replication of ssRNA viruses and makes up the genome of some dsRNA viruses (Figure 3A).71 This receptor is unique among TLRs as it signals solely through the TRIF pathway. The most commonly used TLR3 agonist is a high molecular weight synthetic dsRNA analogue, polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)).72 Poly(I:C) is a potent stimulator of conventional DCs (cDCs) and effector T-cell responses.73 However, its development as a vaccine adjuvant has been hampered by its in vivo toxicity at high doses,9 which have been partially attributed to additional signaling through cytosolic PRRs MDA-5 and RIG-1 in addition to TLR3.74 These effects could potentially be mitigated by poly(I:C) conjugation with other compounds. Alternative dsRNA TLR3 agonists IPH-3102,75 Rintatolimod76 (poly-IC12U) and poly-ICLC77 show reduced toxicity but have not been used as TLR-conjugates as of yet.

Figure 3.

TLR3 agonists are dsRNAs that bind to TLR3 dimers. (A) Crystal structure of mouse TLR3-dsRNA (PDB: 3CIY). The receptors bind to the negatively charged backbone of the dsRNA molecule. TLR3 is shown in blue and orange, and dsRNA is shown in green. (B) Carton structure of dsRNA with sites that have been conjugated highlighted by green arrows and suggested sites of conjugation by blue arrows.

Despite the clinical potential for TLR3 agonist conjugates, few examples exist of poly(I:C)-conjugates (Table 1). Huang et al. conjugated commercially available poly(I:C) to a protein antigen by introducing linkers on the cytosine primary amines using sodium bisulfite catalyzed transamination reactions.78 This strategy invariably leads to a heterogeneous mixture of conjugates, however, as there are multiple cytosines within a poly(I:C) molecule. Although they have not been directly compared in a study, we speculate that conjugation on the nucleobases of poly(I:C) is more likely to disrupt binding to TLR3 than conjugation to the termini, due to the fact that dsRNA binding to TLR3 requires a stretch of at least 40–50 unobstructed base pairs (Figure 3A).79 To conjugate poly(I:C) with its termini, one can employ phosphoramidate chemistry on terminal 5′-phosphates (Figure 3B).80,81 This technique was used by Shukoor et al. to conjugate poly(I:C) to γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles with its 5′ terminal phosphates.82,83

Zhang et al. recently reported84 on the only known class of small molecule TLR3 agonists. Their lead compound, CU-CPT17e, is a weakly potent human TLR3 agonist (EC50: 4.8 μM) and can also signal through human TLRs 8 (EC50: 13.5 μM) and human TLR9 (EC50: 5.7 μM), while signaling through murine TLRs was not investigated in this study. CU-CPT17e and its analogues could be a useful alternative to poly(I:C) in conjugates that require small molecule TLR3 agonists. However, SAR studies show that alterations to the structure of CU-CPT17e consistently leads to abrogation of TLR3 potency,84 complicating the successful conjugation of this small molecule TLR3 agonist. Alternatively, studies have shown that nucleic acid based adjuvants can be associated with various molecules, including antigens, through electrostatic interactions with the backbone phosphates. Zhang et al. demonstrated this technique to form polyelectrolyte multilayer vaccines composed of poly(I:C) and cationic ovalbumin (OVA) peptide antigens which stimulated robust T cell responses.85 Follow-up studies further characterized these materials and their ability to generate powerful immune responses.86,87

In conclusion, TLR3 has a unique signaling pathway and immunological activity but has been limited in application due to a lack of agonists. Although highly potent, commercially available dsRNA TLR3 agonists are bulky, polydisperse, and difficult to characterize using conventional chemical analysis techniques, conjugation of prototypical TLR3 agonist poly(I:C) can proceed by introducing chemical handles to cytosines along its backbone. However, we suggest that the terminal ends of dsRNA analogues may be better sites for conjugation based on site availability as suggested by crystal structure analysis and the homogeneous nature of such a compound. The recently reported class of small molecule TLR3 agonists are attractive due to their small molecule nature, but they are considerably less potent toward TLR3 than poly(I:C). Thus, the field would benefit from the discovery of novel, potent small-molecule ligands that are exclusive agonists of TLR3 and can be modified to generate bioconjugates.

TLR4.

TLR4 was the first human TLR identified to bind a ligand, by Poltorak et al.88 and Hoshino et al.,89 and is the most studied among the TLR family. TLR4 binds ligands with the aid of myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2), forming a TLR4-MD2-agonist complex (Figure 4A).90 TLR4 is unique among TLRs in that, upon ligand binding, it can signal through both the MyD88 and TRIF pathways (Figure 1), resulting in a variety of accessible immune response profiles.91 Some TLR4 agonists bias particular signaling pathways, presumably through differing conformational changes and cellular location upon receptor binding, resulting in unique immune responses.92 Thus, tuning the chemical structure of these agonists impacts the immunological activity of the compound. Its main natural binding ligands are lipopolysaccharides (LPS), major components of the Gram-negative bacteria cell membrane responsible for bacterial sepsis (Figure 4A).90 Although many forms of LPS exist, the toxicity of these molecules has prevented their use in vaccines. However, several groups, notably Qureshi et al.,93 developed a detoxified analog of LPS, monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), which is now FDA approved as an adjuvant in multiple vaccines and is currently in several clinical trials.94 The diversity in chemical composition and immunological activity of TLR4 agonists presents an opportunity for chemical manipulation in a variety of TLR conjugate applications (Table 1).

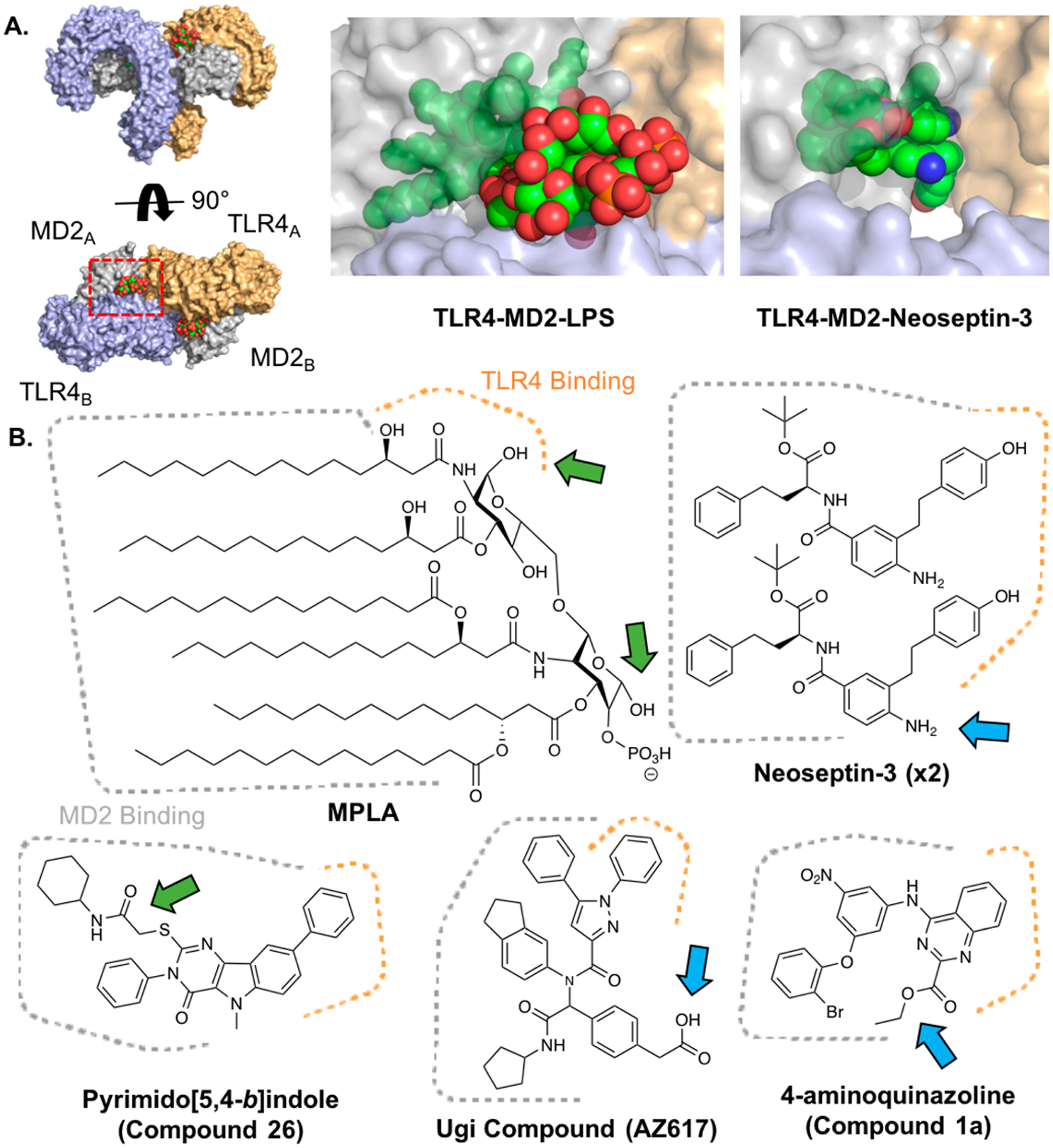

Figure 4.

TLR4 agonists bind MD2 and TLR4. (A) Crystal structure of human TLR4-MD2-LPS (PDB: 3FXI) from two viewpoints (left), red rectangle depicts zoom view of LPS binding (middle) in which proteins are shown with 40% transparency. The analogous view from the mouse TLR4-MD2-Neoseptin-3 crystal structure is also shown (PDB: 5IJC, right). TLR4 is shown in blue and orange, MD2 is shown in gray, and LPS and Neoseptin-3 are shown in green. (B) Chemical structures of various TLR4 agonists. Areas that bind MD2 (dotted gray) and TLR4 (dotted orange) shown. Green arrows highlight previous sites of conjugation; blue arrows highlight suggested sites of conjugation.

The glycolipid moiety in LPS-derived TLR4 agonists contains several sites for modification. MPLA was the first example of an intentionally modified LPS derivative and has since been used heavily as a vaccine adjuvant. MPLA is the lipid A component of LPS, but lacking the reducing end phosphate, which decreases the toxicity over 1000-fold (Figure 4B).95 The reduction in toxicity has been attributed to the bias of activation toward the TRIF pathway over MyD88 pathway, resulting in less pro-inflammatory cytokine production.96 Modifications that bias activity have been further exploited to tune the immunomodulatory properties of the agonist. For example, Carter and co-workers have described glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant (GLA) and second-generation lipid adjuvant (SLA), MPLA analogues with varying lipid chain lengths that elicit distinct immunological responses and activate both mouse and human TLR4.92 Although these modifications can be used to tune the immune response, they are not sites amenable to conjugation chemistry as this portion of the molecule directly binds to the MD2-TLR4 complex (Figure 4B).

Although the hydrophobic portions of glycolipid TLR4 agonists are not ideal sites of conjugation, the exposed functional groups of the sugars have been used as conjugation handles. In one example, Schülke et al. reacted MPLA with carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) followed by OVA to form a nonspecific MPLA-OVA conjugate.97 The conjugation resulted in boosted immune responses toward OVA compared to the mixture of unconjugated MPLA and OVA. In another example, Guo and co-workers developed a synthetic strategy to afford an MPLA derivative with an amino linker appended to the nonreducing hydroxyl group.98–100 Conjugates of this derivative with TACAs via amide bond formation afforded self-adjuvanting, glycoconjugate cancer vaccines. Recently, Wang et al. did a SAR study on MPLA conjugation to a lipoarabinomannam oligosaccharide and found that nonreducing 6′-hydroxyl conjugates had superior immunological activity to 1-O-conjugates.101 The Guo lab also used 6′-hydroxyl conjugation of MPLA to produce an MPLA-Group C Meningitis glyco-antigen-conjugate vaccine.102 Although the synthetic method developed in this study resulted in 10–100’s of milligrams of MPLA derivatives amenable to a variety of conjugation strategies, the approach requires expertise in synthetic organic carbohydrate chemistry, which may not be present in many vaccine development teams. If covalent conjugation is not an option, noncovalent codelivery strategies for MPLA and antigen could be considered. Several studies have reported enhanced adjuvant effects when incorporating glycolipid TLR4 agonists into emulsions, including some FDA approved vaccines, a straightforward strategy given the hydrophobicity of the compounds.103–105 Thus, small molecules may be more advantageous for applications involving direct chemical linkage for the greater ease in chemical manipulation and hydrophilicity.

Recently, a variety of small molecule TLR4 agonists bearing little structural resemblance to glycolipids have been developed. These include pyramido-[5,4-b]indoles, 4-aminoazoquinolines, α-aminoacyl amide “Ugi products”, and neoseptins. Given their synthetically accessible nature, these molecules are more amenable to functionalization for various applications. However, all of these molecules bind predominantly within the MD2 pocket, making it difficult to introduce chemical modifications without sacrificing agonist potency (Figure 4B). Therefore, it is critical to evaluate the site of modification before embarking on a synthetic route to obtain the desired conjugate.

The pyramido-[5,4-b]indoles were discovered by Chan and co-workers via high throughput screening in 2013.106 The hit compound in this study (Compound 28, EC50: 1–10 μM) was shown to stimulate high production of IP-10/CXCL10 and IL-6 in vitro. Variations of this molecule have been used in conjugation studies, including multivalent TLR conjugates, by introducing a linker on the carboxamide moiety.43,107 In another study, Lynn and co-workers synthesized a derivative of the lead pyramido-[5,4-b]indole compound by adding an amine functionality to a carboxamide cyclohexyl group, which was then conjugated to N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) polymers using a bivalent tetraethylene glycol linker.13 In addition, the indole nitrogen has been functionalized with nitroveratryloxycarbonyl (NVOC) to afford a light-activated TLR4 agonist, showing that this site is important for ligand binding despite docking studies, suggesting that it may be solvent accessible.108 More recently, a further optimized pyramido-[5,4-b]indole TLR4 agonist (Compound 26, EC50: 600 nM, Figure 4B) was shown to improve and bias human TLR4 activation over mouse TLR4 activation.109 Although this molecule has yet to be implemented in conjugation applications, we expect it to behave similarly to the original hit molecule, Compound 28, based on reported docking studies and SAR studies.

The same group discovered substituted 4-aminoquinazoline human TLR4 agonists by high throughput screening in 2014.110 The hit compound (Compound 1a, EC50: 2 μM) was predicted to bind in a similar manner as pyramido-[5,4-b]indole compounds in docking studies, despite the lack of structural similarity. SAR studies suggested that the ester moiety may be amenable to derivatization for conjugation applications as functionalization with bulky groups had favorable effects on potency (Figure 4B). However, docking studies suggested that this site may reside at the interface of TLR4 and MD-2, meaning that conjugation to this site may require a linker to prevent perturbation of TLR4-MD-2 dimerization.

Neoseptin-3 is a peptidomimetic molecule discovered by Wang et al. through screening compounds for activation of TLR4-MD2 in murine macrophages.111 Despite the simple design, the molecule has few sites amenable to chemical functionalization due to the unique binding mechanism of the compound. Two Neoseptin-3 molecules bind asymmetrically within the same binding pocket of the TLR4-MD2 complex, a property which is thought to be unique among all studied protein–ligand interactions (Figure 4A). The Neoseptin-3 aniline moiety appears to be a potential site of conjugation, based on the reported SAR study and crystal structure evaluation (Figure 4B). However, while one of the molecule’s anilines appears to be solvent exposed, the other interacts with TLR4 residues. Hypothetically, stimulation with a 1:1 mixture of conjugated and unconjugated Neoseptin-3 molecules may avoid this issue. However, this strategy may result in little Neoseptin-3-conjugate binding if the conjugate affinity for the receptor is lower than unconjugated Neoseptin-3. Thus, Neoseptin-3 conjugation strategies would likely require empirical design and testing to determine effective sites or linkers needed. In addition, Neoseptin-3 only activates mouse TLR4, limiting its practical use.

Marshall et al. developed the human TLR4 stimulating “Ugi compounds” using a combinatorial molecule screen with Ugi multicomponent reaction products.112 These molecules were highlighted for their high potency and hydrophilicity. One of the lead compounds in the study, AZ617 (Figure 4B, EC50: 6.3 nM), was within an order of magnitude of LPS potency (EC50: 2.4 nM) and exhibited ideal hydrophilicity characteristics. Docking studies suggest that the compound binds in a similar location to other small molecule TLR4 agonists, between MD-2 and TLR4. In this case, the free carboxyl group appears to be close to the solvent exposed area of the binding pocket. Thus, conjugation to other molecules, potentially through amide or ester bond formation, might be possible at this site. In fact, some derivatives in SAR studies contained an alkyne substituted for the carboxyl group, among other modifications, making it amenable to click chemistry. However, these compounds suffered a 10–100-fold drop in activity and reduced hydrophilicity compared to AZ617.

Neve and co-workers demonstrated that derivatives of Euodenine A, a natural product isolated from Papua New Guinea Tree, had low μM affinity for human TLR4.113 SAR studies suggest that substituting the methyl group appended to the cyclobutyl moiety in Euodenine A with functional handles for conjugation may be tolerated. However, no docking studies are reported for this molecule, making conjugation attempts to the molecule more empirical relative to other small molecule TLR4 agonists.

In summary, TLR4 agonists have great potential as immunological modulators as demonstrated by their clinical use. These applications could be expanded or improved with TLR4 agonist conjugates. Although most applications have used glycolipid based TLR4 agonists, like MPLA or GLA, these compounds are difficult to conjugate effectively. Alternatively, several small molecule TLR4 agonists exist with a range of chemical structure and potency. However, SAR studies have demonstrated that potency is sensitive to small changes in chemical structure. Thus, TLR4 agonist conjugation strategies could be advanced by developing simplified glycolipid synthesis protocols, reliable modification techniques, and by improved design of small molecules amenable to conjugation. Billod et al. recently reviewed computation based approaches for TLR4 ligand prediction and design, which could aid in the development of TLR4 agonists for conjugation.114

TLR5.

TLR5 resides on the cell membrane and responds to flagellin.115,116 Flagellin is a bacterial protein (~50 kDa) that self-assembles to form the flagellum organelle, providing motility for the organism. Recombinant flagellin and modified variants are also potent activators of TLR5.117–119 TLR5 agonist conjugates have largely been used as recombinant fusion proteins with disease related antigens to generate single molecule vaccines, several of which are in clinical trials (Table 1).120–122 Recombinant expression of antigens with fused flagellin may not work in every application. For example, the fused protein may have poor solubility characteristics, compromise antigen expression, block antibody epitopes, or generate immune responses that are not well suited for specific applications. To overcome some of the limitations of flagellin-antigen fusion proteins, several studies have shown that codelivery of flagellin-coated nanoparticles and antigen can also be used as effective vaccines.123–125 Flagellin has also been conjugated to other compounds through non-site-specific cross-linking chemistries with surface exposed lysines.118,126–128

In these studies, authors have noted that the conjugation approach could be improved by generating flagellin variants which are designed to facilitate conjugation in portions of the protein that are not involved with TLR5 binding.

The only synthetic small molecule agonists for TLR5 are flagellin derived peptides.129 These peptides share homology to flagellin’s highly conserved D1 binding domain and can be as small as 13 residues in size. To the best of our knowledge, conjugates of flagellin derived peptides have yet to be synthesized for vaccine applications. The flagellin peptide should be amenable to conjugation with other peptides or molecules via traditional SPPS approaches. However, we observed no in vitro activity of TLR5 peptides or TLR5 peptides conjugated with small molecules in initial studies (unpublished data).

TLR7 and TLR8.

TLR7 and TLR8 agonists are among the most studied of the TLR family. Similar to TLR3 and TLR9, the receptors are located in the endosome and bind nucleic acid-based agonists (Figure 5A).130 However, unlike TLR3 and 9, TLR7 and 8 are expressed across most human immune cell types. This feature has made TLR 7 and 8 targeting adjuvants sought after to generate efficacious T cell responses in human vaccines.131 In addition, most TLR7/8 agonists are effective across many species.

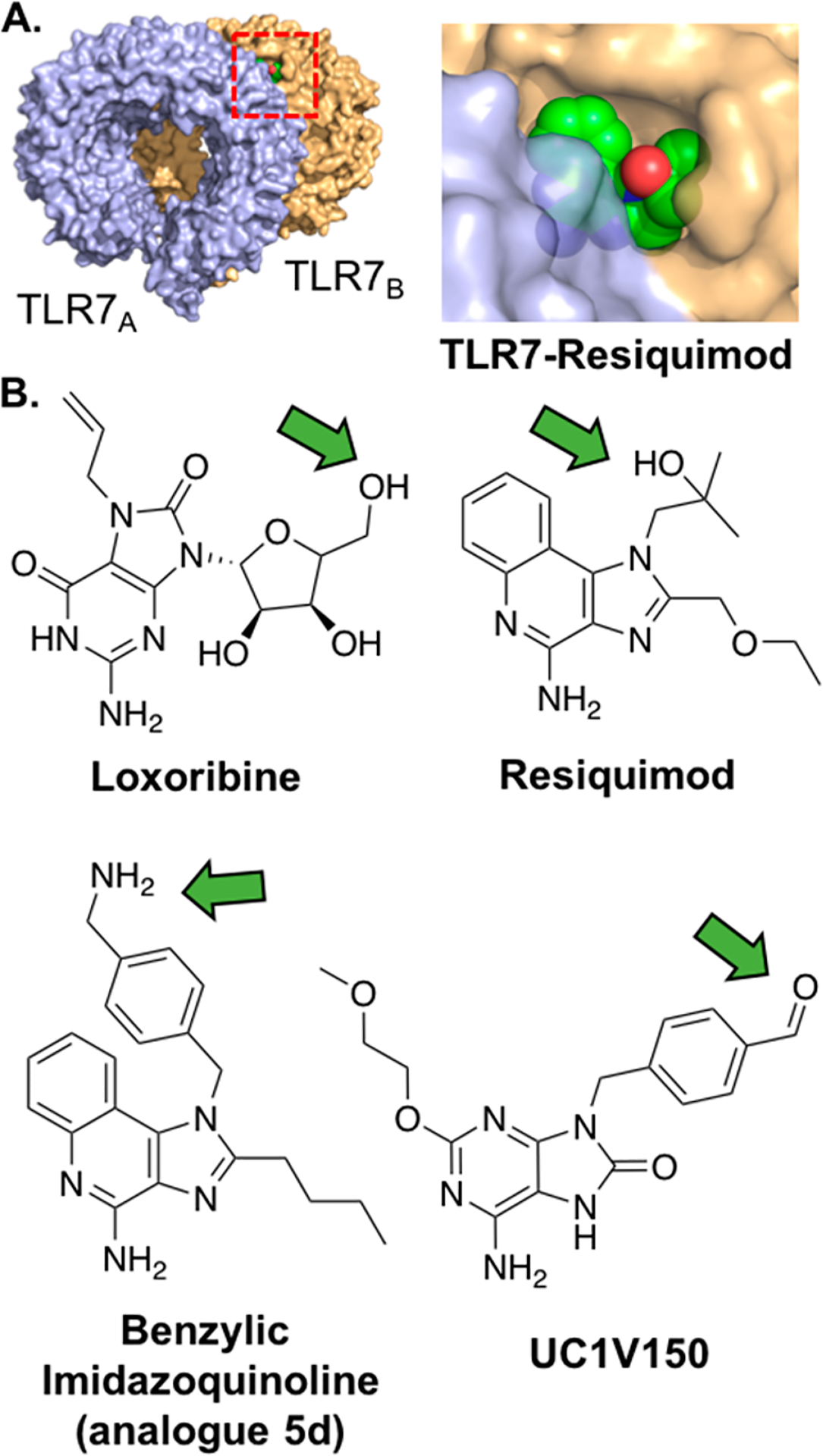

Figure 5.

TLR7/8 agonists bind TLR7 and/or TLR8 homodimers. (A) Crystal structure of monkey TLR7-Resiquimod (PDB: 3FXI), red rectangle depicts view of Resiquimod binding (right) in which proteins are shown at 20% transparency. The molecule bridges the receptors at the interface. TLR7 is shown in blue and orange, and Resiquimod is shown in green. (B) Chemical structures of various TLR7/8 agonists. Green arrows highlight recommended sites of conjugation.

The natural ligands for TLR7 and TLR8 are ssRNAs of viral origin.130 Due to the poor drug properties of RNA, several small molecule agonists have been developed, including imidazoquinolines, purine derivatives, and guanosine analogues.75 Many of these heteroaromatic molecules are agonists for both TLR7 and TLR8.132 However, empirical testing, crystal structure examination, and SAR studies have shed light on the structural requirements for TLR7 or TLR8 agonist specificity.133–135 These small molecule agonists have been effectively utilized as immunostimulants in a variety of applications. One synthetic small molecule imidazoquinoline TLR7 agonist, Imiquimod, is approved for clinical use in topical treatment of certain skin cancers, genital warts, and skin conditions.136 However, promising results in vitro are often difficult to recapitulate, and even potentially toxic, in vivo.8,137 This observation has been attributed to the molecules’ pharmacokinetic properties as they rapidly diffuse to the bloodstream, resulting in systemic cytokine production and inflammation.31 Due to the practical issues, yet clinical promise, of TLR7/8 agonists, they have received considerable attention as TLR conjugates (Table 2). The basic chemical structure of these heteroaromatics has multiple sites amenable for functionalization; both a primary and secondary amine are present for conjugation, as well as an aromatic ring system capable of bearing other functional groups. Several conjugation strategies have been successfully employed, but the potency and biological effects of the conjugates varies greatly.

Table 2.

Overview of TLR 7, 8, and 9 Agonist Conjugates

| TLR | agonist | Conjugation site | conjugation chemistry | conjugated to | refa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR7 | SM360320 | N1-benzyl linkage | Amide, hydrazone | Polymer, protein, phospholipid | 14,18,139 |

| N1-alkyl linkage | Amide | Protein | 179 | ||

| 2-alkoxy-8-hydroxyadenyl derivative | C-2 linkage | CuAAC | Peptide | 140 | |

| TLR7/8 | 3M-012 | N1 linkage | thiol-maleimide, UV light induced coupling | Peptide, protein | 150,149 |

| Resiquimod | C-4 linkage | Carbamate linkage | Photocage | 147 | |

| N1-benzyl imidazoquinoline | N1-benzyl linkage | Thiourea, reductive amination, amide | Fluorophore, protein, TLR7/8 agonist | 142,141,148 | |

| C-4, N1-benzyl, N1-alkyl linkage | Amide | Polymer | 13 | ||

| Imidazoquinoline amino acid | N- and C- terminus | SPPS | Peptide | 155 | |

| Loxoribine | C5’ OH of ribose | CuAAC | TLR4- and 9 agonist | ||

| TLR9 | Class A CpG | 5’ Phosphate | Phosphoramidite | Phospholipid | 20 |

| Class B CpG | 5’ Phosphate | Thioether, Thiol-maleimide, phophoramidite, CuAAC, bis-aryl hydrazone, reductive amination, disulfide | TLR4-, 7/8 and 9 agonists, polymers, biotin, fluorophore phospholipid, protein | 163,19,107,180,20,181,165,12,15 | |

| Class B CpG | 3’ Phosphate | Amide, thiol-maleimide, bis-aryl hydrazone | LLC cells, TLR2/6- and 4 agonists, peptide, protein | 45,44,48,165 | |

| Class C CpG | 5’ Phosphate | Disulfide coupling, phosphoramidite | Nanoparticles, phospholipid | 15,20 |

References are clustered and ordered by conjugation chemistry.

Most adenine analogues found in conjugate applications are tethered through a substituted N1-benzyl linker, based on the potent TLR7 agonist 9-benzyl-8-hydroxy-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) adenine (SM360320).138 Wu and co-workers were the first to synthesize a SM360320 derivative for conjugation by functionalizing the N1-benzyl with an aldehyde moiety.139 The resulting TLR7 agonist, UC-1 V150 (Figure 5B), was ligated to hydrazine functionalized mouse serum albumin (MSA), while retaining its TLR7 agonist activity. Another conjugation method, from the same lab, involved using an N1-benzylic carboxylic acid UC-1 V150 analogue, which was conjugated to phospholipids, with or without PEG spacers.18 Adenine derivatives have also been ligated through N1-alkyl linkages, although this resulted in less potent conjugates. Alternatively, Weterings and colleagues have described a method to covalently link a 2-alkoxy-8-hydroxyadenine derivative through an ethylene glycol linked azide on its C-2 position to OVA peptide epitopes.140 This adenine derivative was conjugated to a peptide epitope through click chemistry, creating a self-adjuvanting vaccine. Although conjugation of the TLR7 agonist increased presentation of the antigen, it also abolished the induction of DC activation. The authors suggest steric hindrance of the peptide moiety may influence binding of the conjugate to the TLR.

Similar to adenine analogues, conjugation of imidazoquinolines mainly proceeds through benzylic linkages. Shukla and co-workers conjugated an N1-(4-aminomethyl)benzyl substituted imidazoquinoline (analogue 5d, Figure 5B) to three fluorescent dyes, fluorescein, rhodamine B, and BODIPY-TR-cavarine, either directly or by first converting the free amine to an isothiocyanate.141 In doing so, they created potent, fluorescent probes for TLR7 activation. The same group also ligated N1-(4-aminomethyl)benzyl substituted imidazoquinolines under more mild conditions. By converting the free amine to an isothiocyanate- and maleimide-group, they conjugated the TLR agonist to both a model peptide and reduced glutathione, in aqueous buffer, without additional reagents.142 The amino group was also reacted directly with a model oligosaccharide under reductive amination conditions. All resulting conjugates were obtained in high yield and preserved their agonistic activity.

Lynn et al. demonstrated ligation of N1-alkyl and N1-(4-aminomethyl)benzyl substituted (analogue 5d reported previously) TLR 7 agonists.13,143 They showed that the benzylic linker (Figure 5B, EC50: 0.1 μM) increased potency of the conjugates 20-fold compared to the alkyl linker (EC50: 2 μM) inspired by previously reported SAR studies.144 The benzylic imidazoquinoline compound was conjugated to an N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) polymer which enhanced its immunological activity in vivo. This effect was achieved by causing accumulation in the draining lymph node instead of diffusion to the bloodstream.

Conjugation of imidazoquinolines through the C-4 amine resulted in a complete loss of agonist activity according to SAR studies145 and crystal structures146 of TLR8. In one example, a method to gain spatial and temporal control over immune cell activation was demonstrated by photocaging the C-4 amine of Imiquimod and Resiquimod.147 The free C-4 amine of the imidazoquinolines was functionalized with 2-(2-nitrophenyl)-propyl chloroformate (NPPOC-Cl), creating a light-responsive TLR agonist. TLR7/8 agonist dimers linked through their C-4 amine also display sharply decreased TLR7 agonist activity compared to N1-benzyl linked dimers.148

Willie-Reece and co-workers demonstrated the promise for TLR7/8 agonist-antigen conjugates as a subunit HIV vaccine.149 An amine functionalized resiquimod (3M-012) was photo-cross-linked with HIV Gag protein. The conjugate was shown to potently stimulate T and B cell responses, in mice and nonhuman primates, toward the antigen, whereas the unconjugated mixture did not. A thiol-functionalized 3M-012 was also cross-linked via thiol-maleimide chemistry to an HIV envelope protein.150 Despite high immunostimulatory activity, the conjugation blocked antibody responses toward certain antigen epitopes. Recently, the same lab demonstrated that protective T cell responses via TLR7/8-antigen conjugates required aggregation of the conjugate.151 In addition, Holbrook and co-workers conjugated an amine functionalized Resiquimod to influenza virus via a bifunctional NHS-maleimide PEG linker.152 This and follow-up studies demonstrated the Resiquimod-influenza conjugate vaccine generated efficacious influenza immunity in nonhuman primate neonates, a difficult vaccination model.153,154 These studies highlight both the clinical potential of TLR7/8 agonist conjugates and the need to development site-specific methods for agonist conjugation to improve antigen-specific immune responses while preserving antigen recognition.

Further broadening the scope of conjugation strategies for TLR7/8 agonists, Fujita and co-workers synthesized an imidazoquinoline-like amino acid, 6-(4-amino-2-butyl-imidazoquinolyl)-norleucine.155 Although weakly potent, the novel amino acid provides a way to easily introduce imidazoquinolines into peptides via SPPS. To create a more potent TLR7/8 agonistic amino acid we propose substituting norleucine for phenyl alanine to create 4-((4-amino-2-butyl-imidazoquinolyl)-methyl) phenylalanine, which contains the N1-benzyl substituent associated with high TLR7/8 agonist activity. Such a highly potent imidazoquinoline-like amino acid would enable facile synthesis of powerful self-adjuvanting vaccines targeting TLR7/8 through SPPS.

Wu and co-workers have developed a guide to effectively modify imidazoquinoline-like TLR7/8 agonists to create small molecule immunopotentiators (SMIPs).33 They showed that creating an antigen depot effect was key for in vivo adjuvant effectiveness by limiting “wasted inflammation” and directing immune responses toward intended targets. This effect was achieved by making the molecules more lipophilic through conjugation with hydrophobic moieties. However, they found these conjugates were impractical due to scale and formulation issues caused by poor conjugate solubility. Instead, the group found that by conjugating SMIPs to phosphate-functionalized PEG linkers followed by noncovalent absorption with alum, the depot effect was achieved, yielding effective adjuvants.

Loxoribine is the only guanosine analogue to yet be conjugated. In an effort to synthesize a trivalent TLR agonist conjugate, a Loxoribine derivative amenable to conjugation was synthesized by substituting the 5′ primary alcohol for an azide (Figure 5B).107 The Loxoribine-azide was conjugated to an alkyne-functionalized core molecule through copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne–azide cycloaddition (CuAAC). However, whether this conjugation strategy preserves TLR7/8 agonist potency remains uncertain. Conjugation of Loxoribine to a diagonist of CpG ODN (TLR9) and indole (TLR4) did not increase the conjugate’s potency, which we attribute to the relatively low potency of Loxoribine.

In summary, TLR7/8 agonists are synthetically accessible, relatively potent, and highly amenable to conjugation. Conjugation of TLR7/8 agonists to phospholipids and polymers has proven to be an effective strategy in improving their pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetic properties, and their conjugation to protein and peptide antigens creates highly immunogenic self-adjuvanting vaccines. In addition, the synthesis of TLR7/8 agonist conjugates is effective as the compounds are more amenable to synthetic methods than lipidated TLR4 agonists. Together, these qualities make TLR7/8 agonists appealing immunostimulants for bioconjugation in many applications.

TLR9.

TLR9 is located in the endosome and senses DNA rich in unmethylated CpG dinucleotides. TLR9 also binds synthetic CpG oligodeoxynuceotides (ODNs), which are short, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligomers with unmethylated CpG motifs (Figure 6A). CpG ODNs induce strong cellular and humoral responses against coadministered antigens, making them highly attractive vaccine adjuvants.156 The sequence of the CpG ODN dictates the species specificity of the agonist, with many commercially available varieties developed for human, murine, bovine, and other organisms.

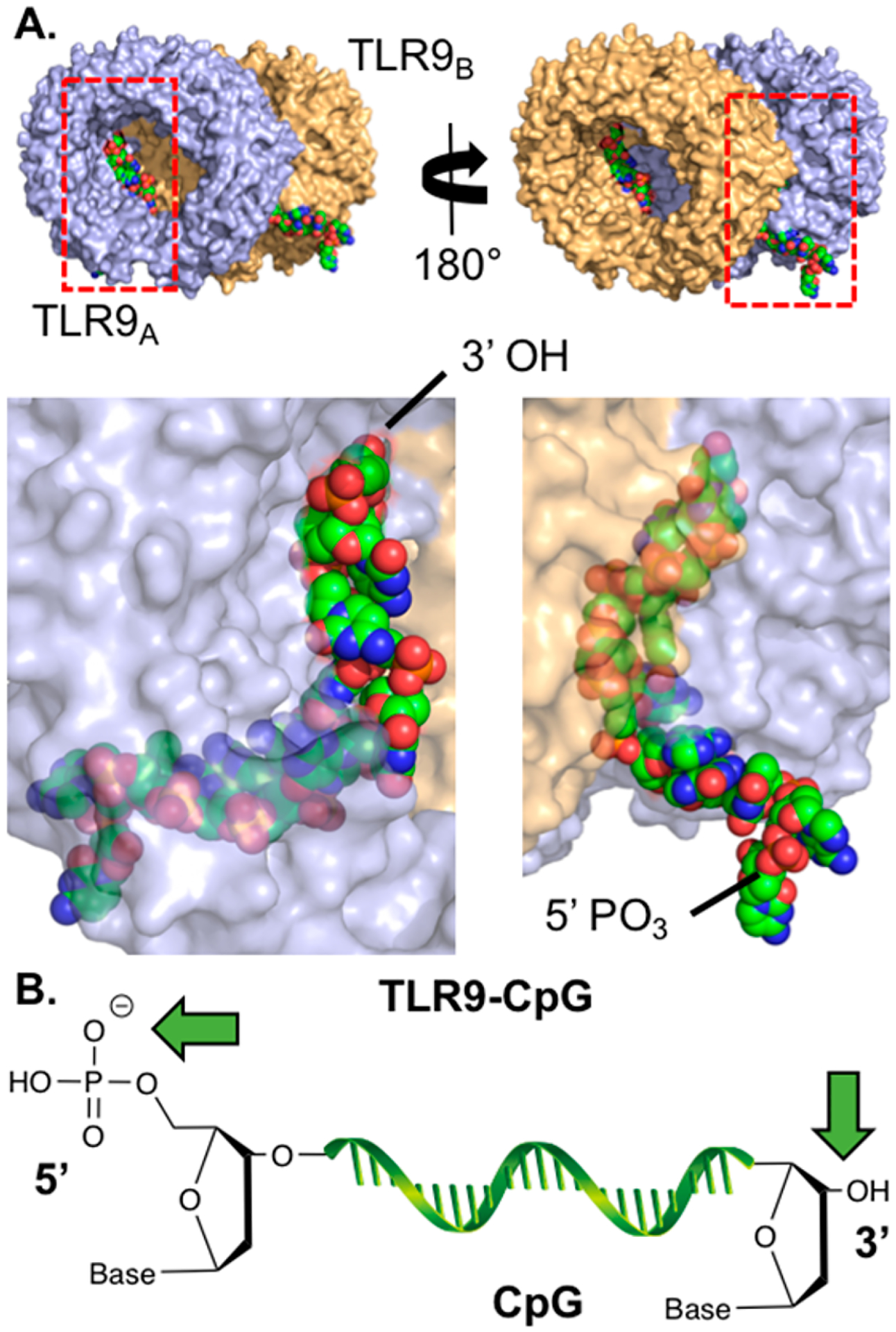

Figure 6.

TLR9 agonists are ssDNAs that bind TLR9 dimers. (A) Two views of the horse TLR9-ssDNA (CpG 1668) crystal structure (PDB: 3WPC). Shown below each view is the zoomed region depicted by the red rectangle where TLR9 is shown at 40% transparency. The receptors bind to the CpG backbone and several nucleobases of the molecule. TLR9 is shown in blue and orange, and ssDNA is shown in green. (B) Carton structure of CpG. Green arrows highlight sites of conjugation.

CpG ODNs have been used in bioconjugates for a variety of applications; CpG ODNs have been conjugated to peptide antigens,48 antibodies,157 other TLR agonists,43,44,107 nanoparticles,15,158 cancer cells,45 and lipids19,20 (Table 2). Conjugation of CpG ODNs to nanoparticles and lipids can improve pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and targeting of the adjuvant to draining lymph nodes.12,20 Conjugation of CpG ODNs to antigens can improve antigen uptake, antigen presentation,48 and cross-priming159 of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. However, some have noted that promising results in animal models may not translate to humans, as TLR9 expression across human immune cell types are more limited.160 Exciting for the field, the first vaccine with unconjugated CpG (Heplisav) was just approved for use in humans indicating the vast potential of this class of compounds.

Many studies report conjugates of CpG ODN linked through either the 3′ or 5′ end (Figure 6B). However, the optimal orientation for CpG ODN in conjugates remains controversial. The crystal structure of the extracellular domain of horse TLR9 ligated to CpG suggests that the 5′ end may be more accessible for conjugation (Figure 6B). It should be noted however that the 5′ end is positioned at the bottom of the TLR9 complex, toward the endosomal membrane, which could inflict steric constraints on 5′ end CpG conjugates. Crystal structure analysis has been insufficient to determine optimal binding sites as suggested by SAR studies. Initial reports by Agrawal and co-workers suggested that the 3′ end was ideal for conjugation and that a free 5′ end was essential for agonist potency.161 For example, CpG dimers that were conjugated 5′-to-5′ were significantly less immunogenic than 3′-to-3′ tethered CpG ODNs, measured by the in vitro induction of spleen lymphocyte proliferation and splenomegaly.161 In a follow-up study, this decrease in TLR9 potency for 5′ conjugation was shown to be dependent on the size of the attached moiety and independent of cellular uptake.162 In vivo, 5′ conjugation of CpG ODNs to a bulky amyloid-β peptide antigen sharply decreased IL-12 induction, while 3′ conjugates elicited strong IL-12 responses in C57BL/6 mice.163

However, some studies contradict the notion that 5′ conjugation of CpG ODNs leads to reduced TLR9 potency compared to 3′ conjugation. Zhang et al. showed that 5′ conjugation of class B CpG ODN 1826 to bulky dextran polymers did not alter NF-κB activity in TLR9-transfected HEK293 cells.12 It is, however, important to note that an acid labile imine bond164 was used to conjugate CpG to dextran in this study, which could facilitate release of CpG after endosomal uptake. Acid hydrolysis of the imine bond would free the 5′-end of CpG and allow unobstructed binding to TLR9, which would explain why CpG conjugated to dextran retained TLR9 potency. We have, however, also observed (2-fold) decreased TLR9 activity upon 3′ CpG conjugation via thiol-maleimide chemistry with a triazine linker, while activity was maintained when conjugated through the 5′ end (unpublished data). In an effort to end the controversy, Kramer et al. recently compared conjugation of CpG ODN 1668 to an ovalbumin (OVA) protein antigen through both 3′ and 5′ ends using an acid-stable bis-aryl hydrazone linker (Solulink Inc.).165 Interestingly, no statistically significant difference was found in the induction of proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T- cells and IFN-γ production in T-cells from OT-I and OT-II mice between the 3′ and 5′ CpG-OVA conjugates.165 This study suggests that both 3′ and 5′ conjugation of CpG ODNs yield conjugates with comparable potency for induction of cellular T-cell responses, and therefore, in some cases 5′ conjugation does not lead to reduced TLR9 potency of CpG.

Conjugation of CpG ODNs is easily achieved by synthesizing (or ordering) custom CpG ODNs containing reactive groups on the 3′ or 5′ termini via automated phosphoramidite DNA synthesis. In terms of structural requirements for CpG ODN conjugation, both 3′ and 5′ conjugation of CpG ODNs can yield functional conjugates, albeit with reduced potency for some reported 5′ conjugates. Recent studies show that 5′ conjugation of CpG does not necessarily lead to decreased potency, although other studies suggest that a free 5′ end of CpG is vital for immune stimulation. Thus, either 3′ or 5′ linkage strategies are appropriate for most conjugates. However, TLR9 activity of conjugates should be confirmed prior to application.

CONCLUSIONS

TLR agonists have demonstrated their therapeutic potential in a variety of applications, including approved vaccine adjuvants and cancer immunotherapies. However, off-target effects, like systemic inflammation, have limited their practicality in the clinic. Covalent conjugation of TLR agonists to other functional compounds can circumvent these issues by generating effective, directed immune responses. Although only one TLR agonist conjugate, Trumenba, has been FDA approved, these compounds have shown immense promise and additional studies will advance their implementation.

Production of TLR agonist requires careful design to ensure efficacy. Through case studies with SAR analysis, TLR-agonist crystal structure evaluation, and molecular modeling, we have learned important considerations when designing TLR agonist conjugates. These considerations include the choice of agonists, choice of linkage chemistry, selection of conjugation sites that maintain agonist activity, and scalability considerations. TLR agonist discovery and chemical insights in effective TLR agonist conjugation will accelerate the ongoing developments at the forefront of vaccine and immunotherapy development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants (7DP2Al112194-02), (5U01AI124286-02), and, in part, by the Alfred P. Sloan, the Pew Charitable Trust, and the Cottrell Scholars Program. M.V. is a recipient of ERC Starting Grant CHEMCHECK (679921) and a Gravity Program Institute for Chemical Immunology Tenure Track Grant by NWO.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- dsRNA

double-stranded RNA

- ssRNA

single-stranded RNA

- CpG

cytosine-phosphate-guanosine

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- LTA

lipoteichoic acid

- ODN

oligodeoxynucleotides

- LLC

Lewis lung carcinoma

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- SPPS

solid phase peptide synthesis

- TACA

tumor associated carbohydrate antigen

- NCL

native chemical ligation

- SAR

structure activity relationship

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- poly(I:C)

polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid

- OVA

ovalbumin

- cDC

conventional DC

- MD2

myeloid differentiation factor 2

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MPLA

monophosphoryl lipid A

- GLA

glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant

- SLA

second-generation lipid adjuvant

- CDI

carbonyldiimidazole

- NIPAM

N-isopropylacrylamide

- NVOC

nitroveratryloxycarbonyl

- NPPOC

2-(2-nitrophenyl)propyl chloroformate

- SMIP

small molecule immunopotentiators

- CuAAC

copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne–azide cycloaddition

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kawai T, and Akira S (2010) The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol 11, 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Baldridge JR, McGowan P, Evans JT, Cluff C, Mossman S, Johnson D, and Persing D (2004) Taking a Toll on human disease: Toll-like receptor 4 agonists as vaccine adjuvants and monotherapeutic agents. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 4, 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schön MP, and Schön M (2008) TLR7 and TLR8 as targets in cancer therapy. Oncogene 27, 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Marshak-Rothstein A (2006) Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6, 823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, and Coffman RL (2007) Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat. Med 13, 552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Steinhagen F, Kinjo T, Bode C, and Klinman DM (2011) TLR-based immune adjuvants. Vaccine 29, 3341–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lampkin BC, Levine AS, Levy H, Krivit W, and Hammond D (1985) Phase II Trial of a Complex Polyriboinosinic-Polyribocytidylic Acid with Poly-L-lysine and Carboxymethyl Cellulose in the Treatment of Children with Acute Leukemia and Neuroblastoma: A Report from the Children’s Cancer Study Group. Cancer Res. 45, 5904–5909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pockros PJ, Guyader D, Patton H, Tong MJ, Wright T, McHutchison JG, and Meng T-C (2007) Oral resiquimod in chronic HCV infection: Safety and efficacy in 2 placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIa studies. J. Hepatol 47, 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Robinson RA, DeVita VT, Levy HB, Baron S, Hubbard SP, and Levine AS (1976) A phase I-II trial of multiple-dose polyriboinosic-polyribocytidylic acid in patieonts with leukemia or solid tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 57, 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fujita Y, and Taguchi H (2012) Overview and outlook of Toll-like receptor ligand–antigen conjugate vaccines. Ther. Delivery 3, 749–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Blander JM, and Medzhitov R (2006) Toll-dependent selection of microbial antigens for presentation by dendritic cells. Nature 440, 808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhang W, An M, Xi J, and Liu H (2017) Targeting CpG Adjuvant to Lymph Node via Dextran Conjugate Enhances Antitumor Immunotherapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 28, 1993–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lynn GM, Laga R, Darrah PA, Ishizuka AS, Balaci AJ, Dulcey AE, Pechar M, Pola R, Gerner MY, and Yamamoto A (2015) In vivo characterization of the physicochemical properties of polymer-linked TLR agonists that enhance vaccine immunogenicity. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 1201–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chan M, Hayashi T, Mathewson RD, Yao S, Gray C, Tawatao RI, Kalenian K, Zhang Y, Hayashi Y, Lao FS, et al. (2011) Synthesis and Characterization of PEGylated Toll Like Receptor 7 Ligands. Bioconjugate Chem. 22, 445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).de Titta A, Ballester M, Julier Z, Nembrini C, Jeanbart L, van der Vlies AJ, Swartz MA, and Hubbell JA (2013) Nanoparticle conjugation of CpG enhances adjuvancy for cellular immunity and memory recall at low dose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 19902–19907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lin AY, Mattos Almeida JP, Bear A, Liu N, Luo L, Foster AE, and Drezek RA (2013) Gold Nanoparticle Delivery of Modified CpG Stimulates Macrophages and Inhibits Tumor Growth for Enhanced Immunotherapy. PLoS One 8, e63550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wei M, Chen N, Li J, Yin M, Liang L, He Y, Song H, Fan C, and Huang Q (2012) Polyvalent Immunostimulatory Nanoagents with Self-Assembled CpG Oligonucleotide-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 51, 1202–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chan M, Hayashi T, Kuy CS, Gray CS, Wu CCN, Corr M, Wrasidlo W, Cottam HB, and Carson DA (2009) Synthesis and immunological characterization of toll-like receptor 7 agonistic conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 20, 1194–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Andrews CD, Provoda CJ, Ott G, and Lee K-D (2011) Conjugation of lipid and CpG-containing oligonucleotide yields an efficient method for liposome incorporation. Bioconjugate Chem. 22, 1279–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Yu C, An M, Li M, and Liu H (2017) Immunostimulatory Properties of Lipid Modified CpG Oligonucleotides. Mol. Pharmaceutics 14, 2815–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).O’Neill LAJ, Golenbock D, and Bowie AG (2013) The history of Toll-like receptors -redefining innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 13, 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Iwasaki A, and Medzhitov R (2015) Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol 16, 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Iwasaki A, and Medzhitov R (2004) Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol 5, 987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Barton GM, and Kagan JC (2009) A cell biological view of Toll-like receptor function: regulation through compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Immunol 9, 535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Medzhitov R (2001) Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 1, 135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Oosting M, Cheng S-C, Bolscher JM, Vestering-Stenger R, Plantinga TS, Verschueren IC, Arts P, Garritsen A, van Eenennaam H, Sturm P, et al. (2014) Human TLR10 is an anti-inflammatory pattern-recognition receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E4478–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Jiang S, Li X, Hess NJ, Guan Y, and Tapping RI (2016) TLR10 is a Negative Regulator of Both MyD88-Dependent and Independent TLR. J. Immunol 196, 3834–3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hess NJ, Felicelli C, Grage J, and Tapping RI (2017) TLR10 suppresses the activation and differentiation of monocytes with effects on DC-mediated adaptive immune responses. J. Leukocyte Biol 101, 1245–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, and Akira S (2003) Role of Adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-Independent Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway. Science 301, 640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Akira S, and Takeda K (2004) Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wu TY-H (2016) Strategies for designing synthetic immune agonists. Immunology 148, 315–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Xu Z, and Moyle PM (2017) Bioconjugation Approaches to Producing Subunit Vaccines Composed of Protein or Peptide Antigens and Covalently Attached Toll-Like Receptor Ligands. Bioconjugate Chem, DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wu TY-H, Singh M, Miller AT, De Gregorio E, Doro F, D’Oro U, Skibinski DAG, Mbow ML, Bufali S, Herman AE, et al. (2014) Rational design of small molecules as vaccine adjuvants. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 263ra160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Oosenbrug T, van de Graaff MJ, Ressing ME, and van Kasteren SI (2017) Chemical Tools for Studying TLR Signaling Dynamics. Cell Chem. Biol 24, 801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Akira S, Uematsu S, and Takeuchi O (2006) Pathogen Recognition and Innate Immunity. Cell 124, 783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Jin MS, Kim SE, Heo JY, Lee ME, Kim HM, Paik S-G, Lee H, and Lee J-O (2007) Crystal Structure of the TLR1-TLR2 Heterodimer Induced by Binding of a Tri-Acylated Lipopeptide. Cell 130, 1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Spohn R, Buwitt-Beckmann U, Brock R, Jung G, Ulmer AJ, and Wiesmüller K-H (2004) Synthetic lipopeptide adjuvants and Toll-like receptor 2—structure–activity relationships. Vaccine 22, 2494–2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Omueti KO, Beyer JM, Johnson CM, Lyle EA, and Tapping RI (2005) Domain Exchange between Human Toll-like Receptors 1 and 6 Reveals a Region Required for Lipopeptide Discrimination. J. Biol. Chem 280, 36616–36625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Khan S, Weterings JJ, Britten CM, de Jong AR, Graafland D, Melief CJM, van der Burg SH, van der Marel G, Overkleeft HS, Filippov DV, and Ossendorp F (2009) Chirality of TLR-2 ligand Pam3CysSK4 in fully synthetic peptide conjugates critically influences the induction of specific CD8+ T-cells. Mol. Immunol 46, 1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zaman M, and Toth I (2013) Immunostimulation by Synthetic Lipopeptide-Based Vaccine Candidates: Structure-Activity Relationships. Front. Immunol 4, 318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Jung G, Wiesmüller K-H, Becker G, Bühring H-J, and Bessler WG (1985) Increased Production of Specific Antibodies by Presentation of the Antigen Determinants with Covalently Coupled Lipopetide Mitogens. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 24, 872–873. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, and Kirschning CJ (1999) Peptidoglycan- and Lipoteichoic Acid-induced Cell Activation Is Mediated by Toll-like Receptor 2. J. Biol. Chem 274, 17406–17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ryu KA, Slowinska K, Moore T, and Esser-Kahn A (2016) Immune Response Modulation of Conjugated Agonists with Changing Linker Length. ACS Chem. Biol 11, 3347–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Mancini RJ, Tom JK, and Esser-Kahn AP (2014) Covalently Coupled Immunostimulant Heterodimers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 53, 189–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Tom JK, Mancini RJ, and Esser-Kahn AP (2013) Covalent modification of cell surfaces with TLR agonists improves & directs immune stimulation. Chem. Commun 49, 9618–9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Luo Y, Friese OV, Runnels HA, Khandke L, Zlotnick G, Aulabaugh A, Gore T, Vidunas E, Raso SW, Novikova E, et al. (2016) The Dual Role of Lipids of the Lipoproteins in Trumenba, a Self-Adjuvanting Vaccine Against Meningococcal Meningitis B Disease. AAPS J. 18, 1562–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Fletcher LD, Bernfield L, Barniak V, Farley JE, Howell A, Knauf M, Ooi P, Smith RP, Weise P, Wetherell M, et al. (2004) Vaccine Potential of the Neisseria meningitidis 2086 Lipoprotein. Infect. Immun 72, 2088–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Khan S, Bijker MS, Weterings JJ, Tanke HJ, Adema GJ, van Hall T, Drijfhout JW, Melief CJM, Overkleeft HS, and van der Marel GA (2007) Distinct uptake mechanisms but similar intracellular processing of two different toll-like receptor ligand-peptide conjugates in dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem 282, 21145–21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Ingale S, Wolfert MA, Gaekwad J, Buskas T, and Boons G-J (2007) Robust immune responses elicited by a fully synthetic three-component vaccine. Nat. Chem. Biol 3, 663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zom GG, Khan S, Britten CM, Sommandas V, Camps MGM, Loof NM, Budden CF, Meeuwenoord NJ, Filippov DV, and van der Marel GA (2014) Efficient Induction of Antitumor Immunity by Synthetic Toll-like Receptor Ligand – Peptide Conjugates. Cancer Immunol. Res 2, 756–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Zeng W, Ghosh S, Lau YF, Brown LE, and Jackson DC (2002) Highly Immunogenic and Totally Synthetic Lipopeptides as Self-Adjuvanting Immunocontraceptive Vaccines. J. Immunol 169, 4905–4912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Ingale S, Buskas T, and Boons G-J (2006) Synthesis of Glyco(lipo)peptides by Liposome-Mediated Native Chemical Ligation. Org. Lett 8, 5785–5788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Nalla N, Pallavi P, Srinivasa B, Miryala S, Kumar VN, Mahboob M, and Sampath HM (2015) Design, synthesis and immunological evaluation of 1, 2, 3-triazole- tethered carbohydrate – Pam 3 Cys conjugates as TLR2 agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem 23, 5846–5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Cai H, Huang Z, Shi L, Zhao Y, Kunz H, and Li Y (2011) Towards a Fully Synthetic MUC1-Based Anticancer Vaccine: Efficient Conjugation of Glycopeptides with Mono-, Di-, and Tetravalent Lipopeptides Using Click Chemistry. Chem. - Eur. J 17, 6396–6406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Cai H, Sun Z, Huang Z, Shi L, Zhao Y, Kunz H, and Li Y (2013) Fully Synthetic Self-Adjuvanting Thioether-Conjugated Glycopeptide- Lipopeptide Antitumor Vaccines for the Induction of Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity against Tumor Cells. Chem. -Eur. J 19, 1962–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Wilkinson BL, Malins LR, Chun CKY, and Payne RJ (2010) Synthesis of MUC1-lipopeptide chimeras. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 46, 6249–6251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Wilkinson BL, Day S, Malins LR, Apostolopoulos V, and Payne RJ (2011) Self-Adjuvanting Multicomponent Cancer Vaccine Candidates Combining Per-Glycosylated MUC1 Glycopeptides and the Toll-like Receptor 2 Agonist Pam3CysSer. Angew. Angew. Chem 123, 1673–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Metzger JW, Beck-Sickinger AG, Loeit M, Eckert M, Bessler WG, and Jung G (1995) Synthetic S-(2, 3-dihydroxypropyl)-cysteinyl peptides derived from the N-terminus of the cytochrome subunit of the photoreaction centre of Rhodopseudomonas viridis enhance murine splenocyte proliferation. J. Pept. Sci 1, 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Muhlradt PF, Kiess M, Meyer H, Sussmuth R, and Jung G (1998) Structure and specific activity of macrophage-stimulating lipopeptides from Mycoplasma hyorhinis. Infect. Immun 66, 4804–4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Huynh AS, Chung WJ, Cho H-I, Moberg VE, Celis E, Morse DL, and Vagner J (2012) Novel toll-like receptor 2 ligands for targeted pancreatic cancer imaging and immunotherapy. J. Med. Chem 55, 9751–9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Mancini RJ, Stutts L, Moore T, and Esser-Kahn AP (2015) Controlling the origins of inflammation with a photoactive lipopeptide immunopotentiator. Angew. Chem 127, 6060–6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).McDonald DM, Wilkinson BL, Corcilius L, Thaysen-Andersen M, Byrne SN, and Payne RJ (2014) Synthesis and immunological evaluation of self-adjuvanting MUC1-macrophage activating lipopeptide 2 conjugate vaccine candidates. Chem. Commun 50, 10273–10276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Willems MMJHP, Zom GG, Khan S, Meeuwenoord N, Melief CJM, van der Stelt M, Overkleeft HS, Codée JDC, van der Marel GA, Ossendorp F, and Filippov DV (2014) N-Tetradecylcarbamyl Lipopeptides as Novel Agonists for Toll-like Receptor 2. J. Med. Chem 57, 6873–6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Zom GG, Welters MJP, Loof NM, Goedemans R, Lougheed S, Valentijn RRPM, Zandvliet ML, Meeuwenoord NJ, Melief CJM, de Gruijl TD, et al. (2016) TLR2 ligand-synthetic long peptide conjugates effectively stimulate tumor-draining lymph node T cells of cervical cancer patients. Oncotarget 7, 67087–67100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Guo X, Wu N, Shang Y, Liu X, Wu T, Zhou Y, Liu X, Huang J, Liao X, and Wu L (2017) The Novel Toll-Like Receptor 2 Agonist SUP3 Enhances Antigen Presentation and T Cell Activation by Dendritic Cells. Front. Immunol 8, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Salunke DB, Shukla NM, Yoo E, Crall BM, Balakrishna R, Malladi SS, and David SA (2012) Structure–Activity Relationships in Human Toll-like Receptor 2-Specific Monoacyl Lipopeptides. J. Med. Chem 55, 3353–3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Hamley IW, Kirkham S, Dehsorkhi A, Castelletto V, Reza M, and Ruokolainen J (2014) Toll-like receptor agonist lipopeptides self-assemble into distinct nanostructures. Chem. Commun 50, 15948–15951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Al-isae K, Zaman M, and Toth I (2011) Simple synthetic toll-like receptor 2 ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 21, 5863–5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Zaman M, Abdel-Aal A-BM, Phillipps KSM, Fujita Y, Good MF, and Toth I (2010) Structure–activity relationship of lipopeptide Group A streptococcus (GAS) vaccine candidates on toll-like receptor 2. Vaccine 28, 2243–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Guan Y, Omueti-Ayoade K, Mutha SK, Hergenrother PJ, and Tapping RI (2010) Identification of novel synthetic toll-like receptor 2 agonists by high throughput screening. J. Biol. Chem 285, 23755–23762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Jensen S, and Thomsen AR (2012) Sensing of RNA Viruses: a Review of Innate Immune Receptors Involved in Recognizing RNA Virus Invasion. J. Virol 86, 2900–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, and Flavell RA (2001) Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413, 732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Lauterbach H, Bathke B, Gilles S, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Luber CA, Fejer G, Freudenberg MA, Davey GM, Vremec D, Kallies, et al. (2010) Mouse CD8α+ DCs and human BDCA3+ DCs are major producers of IFN-λ in response to poly IC. J. Exp. Med 207, 2703–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Gitlin L, Barchet W, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Beutler B, Flavell RA, Diamond MS, and Colonna M (2006) Essential role of mda-5 in type I IFN responses to polyriboinosinic: polyribocytidylic acid and encephalomyocarditis picornavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 8459–8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Wang X, Smith C, and Yin H (2013) Targeting Toll-like receptors with small molecule agents. Chem. Soc. Rev 42, 4859–4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Brodsky I, Strayer DR, Krueger LJ, and Carter WA (1985) Clinical studies with ampligen (mismatched double-stranded RNA). J. Biol. Response Mod 4, 669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Andres MS, Hilton BL, Steven O, Meir K, Barbara S, Douglas B, Hernando M, Norman M, Karen S, Daniel D, et al. (1996) Long-term Treatment of Malignant Gliomas with Intramuscularly Administered Polyinosinic-Polycytidylic Acid Stabilized with Polylysine and Carboxymethylcellulose: An Open Pilot Study. Neurosurgery 38, 1096–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Huang Q, Yu W, and Hu T (2016) Potent Antigen-Adjuvant Delivery System by Conjugation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85B-HspX Fusion Protein with Arabinogalactan-Poly (I: C). Bioconjugate Chem. 27, 1165–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Liu L, Botos I, Wang Y, Leonard JN, Shiloach J, Segal DM, and Davies DR (2008) Structural Basis of Toll-Like Receptor 3 Signaling with Double-Stranded RNA. Science 320, 379–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Chu BCF, Wahl GM, and Orgel LE (1983) Derivatization of unprotected polynucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 6513–6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]