Abstract

Actively growing cells maintain a dynamic, far from equilibrium order through metabolism. Under starvation stress or under stress of exposure to the analog of the anabiosis autoinducer (4-hexylresorcinol), cells go into a dormant state (almost complete lack of metabolism) or even into a mummified state. In a dormant state, cells are forced to use the physical mechanisms of DNA protection. The architecture of DNA in the dormant and mummified state of cells was studied by x-ray diffraction of synchrotron radiation and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Diffraction experiments indicate the appearance of an ordered organization of DNA. TEM made it possible to visualize the type of DNA ordering. Intracellular nanocrystalline, liquid-crystalline, and folded nucleosome-like structures of DNA have been found. The structure of DNA within a cell in an anabiotic dormant state and dormant state (starvation stress) coincides (forms nanocrystalline structures). Data suggest the universality of DNA condensation by a protein Dps for a dormant state, regardless of the type of stress. The mummified state is very different in structure from the dormant state (has no ordering within a cell). It turned out that it is possible to visualize DNA conformation in toroidal and liquid crystal structures in which there is either no or a very small amount of the Dps protein. Observation of the DNA conformation in nanocrystals and folded nucleosome-like structures so far has been inconclusive. The methodological advances described will facilitate high-resolution visualization of the DNA conformation in the near future.

Keywords: Escherichia coli; Starvation stress; 4-Hexylresorcinol; Intracellular nanocrystalline, liquid-crystalline, folded nucleosome-like DNA structures

Introduction

In a dilute solution at thermodynamic equilibrium, DNA forms a coil with a volume of about 500 μm3. The volume of Escherichia coli nucleoid does not exceed 1 μm3. Such a dramatic decrease in the volume occupied by DNA in a cell is a consequence of its condensation. Bacterial genomic DNA, interacting with DNA-associated proteins (NAP, NAP – nucleoid-associated proteins), is in a condensed and functionally organized form in the cell nucleoid. Decades of intense research have shown (Stonington and Pettijohn 1971; Verma et al. 2019) that DNA is organized hierarchically in the nucleoid of an actively growing Escherichia coli cell with three levels of compaction (Verma et al. 2019; Trun and Marko 1998). The lowest level is provided by the interaction of DNA with DNA-binding proteins. At the intermediate level, DNA forms supercoiled loops. On the mega scale, DNA forms six spatially organized macrodomains with a clear territorial organization into which the bacterial nucleoid is divided.

Changes in environmental parameters are perceived by microorganisms as stress. In response to stressful effects, Escherichia coli cells (Bukharin et al. 2005; Tkachenko 2012) include hereditary adaptation strategies based on structural, biochemical, and genetic rearrangements, which make it possible to preserve part of the population and survive under unfavorable conditions. All strategies are aimed at protecting the cell’s genetic material (DNA) (Tkachenko 2012).

In actively growing cells, as in other living systems, a dynamic far from equilibrium order is maintained due to metabolism (Minsky et al. 2002). As cells enter a dormant state (almost complete absence of metabolism), the usual biochemical methods of DNA protection cease to work, and cells, adapting to new conditions, are forced to use physical mechanisms of DNA protection (dense DNA packing, crystallization of DNA with proteins, etc.).

This paper presents the results of experimental studies of the structural organization of DNA in dormant cells of Escherichia coli using synchrotron radiation diffraction and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The results of molecular dynamics modeling of the interaction of DNA with NAP are presented.

The “DNA condensation in an actively growing cell” section discusses the structure of condensed DNA and models of its packaging in an actively growing cell.

The “Experimental methods” section is devoted to the description of the experimental methods used.

The “Structure of condensed DNA under stress of starvation” section presents the results of experimental studies of the structural organization of DNA in dormant cells under the action of starvation stress on a bacterial culture. Changes in the model of the ordering of condensed DNA during the transition from actively growing to dormant cells are discussed.

When the cell culture is exposed to the chemical analog of the autoinducer of anabiosis 4-hexylresorcinol (4-HR), the cells pass into an anabiotic dormant state (almost complete absence of metabolism), and with a further increase in the concentration of 4-HR into a mummified state (complete absence of metabolism while maintaining the shape). The “Structure of condensed DNA under the influence of the chemical analog of the autoinductor of anabiosis 4-hexylresorcinol” section discusses the results of experimental studies of the structural organization of DNA for anabiotic and mummified cells.

In the “Summary and problems” section, a brief summary of the observed results is given. The problems that have arisen from the analysis of the original experimental results obtained are discussed.

The “Research outlook and possible solution” section provides research perspectives. The latest literary methodological advances in nano-imaging and nanotomography of cells using synchrotron radiation and electron microscopy are discussed, which will make it possible in the foreseeable future to determine the architecture of the nucleoid with high resolution in both actively growing and dormant bacteria and thus solve the problems that have arisen at the present time.

DNA condensation in an actively growing cell

DNA condensation

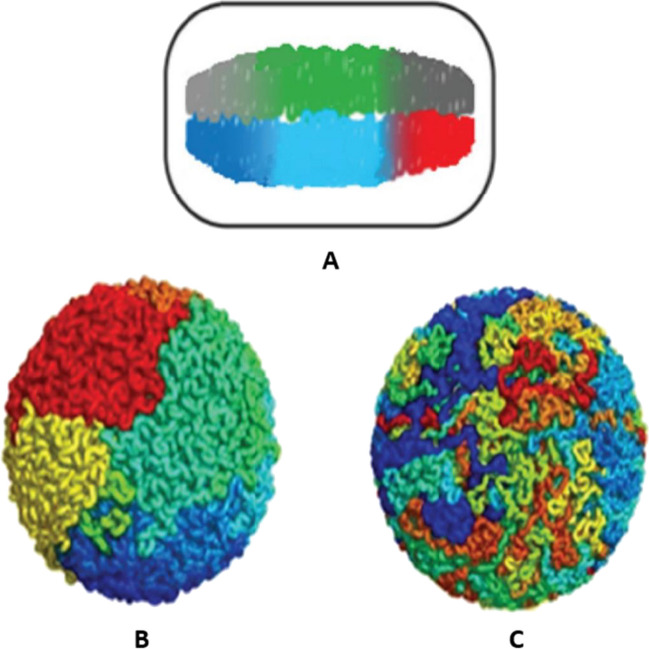

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a widespread gram-negative bacterium, which is one of the most important tools of biological science (Zimmer 2008). E. coli, in this sense, is an analog of the hydrogen atom for microbiology. DNA is a long, highly charged heteropolymer. In a dilute solution, the bacterial DNA of E. coli forms a stochastic coil with a volume of about 500 μm3 (Verma et al. 2019; Grosberg and Khokhlov 1994; Bloomfield 1996). Bacterial genomic DNA and its associated proteins are in the cell in a highly condensed and functionally organized form in the nucleoid (Verma et al. 2019). Nucleoid of Escherichia coli, where the DNA is in the cell, does not exceed 1 μm3. To be in the nucleoid, the DNA must be highly compacted (Bloomfield 1996). In addition, the DNA condensed in the nucleoid must be functional. The condensed DNA must be able to carry out such processes as replication, recombination, segregation, and transcription. The high-resolution structure of the bacterial nucleoid has not yet been determined. Studies using modern molecular biology methods have shown that condensed DNA in a nucleoid has a hierarchical structure and that DNA condensation has some similarities with protein folding (self-organization) (Bloomfield 1996; Krupyanskii and Goldanskii 2002; Krupyanskii 2021; Shaitan 2023). Molecular biology methods, abbreviated as 3C (chromosome conformation capture, 3C) and Hi-C (a high-throughput technique to capture chromatin conformation) (Dekker et al. 2002; Simonis et al. 2006; Dostie et al. 2006), used to study the structural organization of DNA in a cell, made it possible to identify three levels of structural organization of a compact bacterial DNA (Verma et al. 2019). The lowest level (small scale ~ 103 base pairs (bp)) is provided by the interaction of DNA with DNA-binding proteins. At the intermediate level (average scale ~ 104 bp), DNA forms supercoiled loops. At the highest level of structural organization (mega scale ~ 106 bp), DNA forms six spatially organized macrodomains with a clear territorial organization into which the bacterial nucleoid is divided (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A Structural organization of the nucleoid of the bacterium E. coli. (B) Conformation of fractal globule. (C) Conformation of the equilibrium globule

Fractal (crumpled, folded) globule

According to Gennes (1979), the collapse of a long polymer due to topological limitations occurs with the formation of folds of ever-increasing sizes. First, small wrinkles appear. This leads to the formation of a thicker folded polymer, which then itself forms larger folds, etc. (Grosberg et al. 1988). Grosberg et al. (1988) demonstrated that this process should lead to the formation of a long-lived state, which they called a folded (sometimes called as a crumpled) globule (subsequently, it became known as a fractal). It was assumed that such a globule is characterized by a hierarchy of folds, forming a self-similar structure (Grosberg et al. 1988).

An experimental study of the properties of the spatial organization of chromatin in the human cell nucleus using 3C and Hi-C drew attention to the fractal globule as a structural model of chromatin on a large scale of ~10 Mb (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009).

Figure 1B,C shows the conformations of the fractal (B) and equilibrium (C) globules. The fractal globule has several important properties that make it an attractive model for organized chromatin. We list two such properties. 1. A fractal globule has no nodes (Fig. 1B). Fluctuating opening of chromatin in a non-knotted conformation of a fractal globule is very different from DNA opening in an extremely tangled conformation of an equilibrium globule (Mirny 2011). Since it is practically not knotted, any area of the fractal globule can easily and quickly unfold, becoming accessible to transcriptional and other protein mechanisms of the cell. 2. The fractal globule has a striking territorial chain organization that contrasts strongly with the jumbled chain organization seen in the equilibrium globule (Fig. 1C). Chromosomal contacts in human cells have been characterized by Hi-C. Comparison with the experiment shows that the fractal globule qualitatively describes well the properties of the human chromosome on mega scales (3rd level of DNA compaction). The above two properties of the fractal globule made it possible to propose it as a model for DNA folding inside the growing cell on a large scale.

After the success of the fractal globule model as a large-scale packaging of DNA in chromatin in 2011–2014, experimental data began to appear that cast doubt on this statement. It turned out that experiments on small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) can confirm or disprove the validity of one or another model constructed to describe the large-scale structure of chromatin (Iashina and Grigoriev 2019). The intensity of neutron scattering on erythrocyte nuclei is described by a power low. SANS experiments on chromatin determine the exponent as D = 3 or close to it (Iashina and Grigoriev 2019), which contradicts the fractal globule model and actually denies it as the best model for describing the large-scale structure of chromatin in the cell nucleus. For the folded globule, the exponent should have been equal to D = 4.

We should note one more very important property of a fractal globule. In this model, the structure of condensed DNA does not correspond to the global energy minimum of the DNA folding energy landscape. The structure of condensed DNA corresponds to a long-lived intermediate, partially equilibrium state; therefore, it can be expected that DNA in different cells of a bacterial colony can condense differently. The structure of DNA in each cell may differ from the structure of DNA in neighboring cells. The ensemble of cells is heterogeneous. This fact is consistent with the statement known in microbiology that a bacterial multicellular system is characterized by the physiological and morphological heterogeneity of its constituent cells (Bukharin et al. 2005). The heterogeneity of DNA packaging will be discussed at the end of the “Structure of condenced DNA under stress of starvation” section.

The striking territorial organization and the ability of any region of the globule to quickly and easily unfold make models arranged like the fractal globule model one of the most attractive models of large-scale DNA packaging in a cell; moreover, it qualitatively coincides with many (but not all) experimental studies.

Experimental methods

X-ray studies with the use of synchrotron radiation

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) is the most expensive and time-consuming experimental method used in the physics of biological systems. Synchrotron radiation is often used as a radiation source in the X-ray range, especially for studying small crystals (with sizes from μM to nm) and disordered objects such as viruses and cells. The latest advances in biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics are used to visualize the structure of disordered biological objects.

In the experiments performed at the ID23-1 station of the ESRF synchrotron (Grenoble, France), the X-ray beam had a wavelength of λ = 1.6799 Å, and an aperture width of 10 μm, an exposure time for each diffraction pattern was 5 s, and a PILATUS 6M flat detector was located at 95 cm behind the sample along the beam. The measurements were carried out at a temperature of 100 K.

The scheme of the experiment is like two-dimensional powder diffraction with a flat detector. The sample is an ensemble of bacterial cells. The angle (in degrees in this review) between the axis formed by the incident beam and the diffraction ring is called the scattering angle and is denoted as 2θ. Resolution corresponding to a scattering angle is denoted as d. A detailed description of the scattering experiment may be found in the literature (Sinitsyn et al. 2017; Krupyanskii et al. 2018).

Ordering structures with the spacing d are responsible for the increased scattering intensity I corresponding to this lattice spacing. Therefore, an analysis of X-ray diffraction patterns of bacterial cells containing ordering structures can be used to determine the characteristic spacings in these ordering structures and draw conclusions about their architecture.

Methods of electron microscopy

Experimental details of transmission electron microscopy, electron tomography, and analytical methods (EDS) that clearly reflect protein-DNA packing in dormant cells are contained in the original paper (Moiseenko et al. 2022). Here, we briefly describe the main instruments used. Ultrathin sections were examined using JEM1011 and JEM-2100 transmission electron microscopes (Jeol, Japan) at accelerating voltages of 80 kV and 200 kV, respectively, and an increase of 13,000–21,000×. Images were recorded with Ultrascan 1000XP and ES500W CCD cameras (Gatan, USA). Tomograms were obtained from semi-thick (300–400 nm) sections using the Jeol Tomography software (Jeol, Japan).

Energy dispersive X-ray (EDS) spectra were collected, and elemental analysis was performed using the INCA program (Oxford Instruments, UK).

Computer modeling

Molecular dynamics (MD) modeling has also been undertaken for the study of DNA conformation within three-dimensional (3D) crystals of Dps protein. Calculations were carried out using the classical MD method in the Gromacs 2018 software package, using the all-atom force field AMBER99-PARMBSC1 (details one can find in Tereshkin et al. 2019a, b, 2021).

Structure of condensed DNA under stress of starvation

Phases of bacterial growth, Dps protein, and formation of dormant cells

Bacterial growth is the division of a bacterial cell into two daughter cells. Daughter cells are genetically identical to the parent cell. The growth dynamics of the bacterial population are divided into four phases (Zwietering et al. 1990). The first phase of growth is called the lag phase, followed by the exponential phase, during which there is a rapid exponential growth of the population. During the exponential phase, nutrients are consumed at a maximum rate until one of the required compounds is depleted and begins to inhibit growth. The third phase of growth is called stationary; it begins with a lack of nutrients for rapid growth. The metabolic rate drops and cells begin to break down proteins that are not strictly necessary. In this phase, cells begin to experience starvation stress. In response to starvation stress, microorganism cells switch on hereditary adaptation strategies that allow them to preserve part of the population and survive in any unfavorable conditions. These strategies are aimed at protecting the cell’s genetic material (DNA) (Tkachenko 2012). If starvation stress persists, then either the formation of dormant forms, characterized by an almost complete absence of metabolism (exchange with the external environment), or cell death (autolysis) occurs.

In the exponential phase of growth, the relative content of DNA-associated histone-like proteins (NAP) changes. For example, if in the growth phase, the content of the Dps protein (DNA-binding protein from starved cells) is about 6000 protein molecules per cell, then in the stationary and late stationary phase, the content of Dps becomes overwhelming compared to other proteins and amounts to 180,000–200,000 molecules of protein per cell. In the late stationary phase, the interaction of DNA with Dps becomes decisive for DNA conformation. Dps plays a regulatory and protective role in E. coli cells (Chiancone and Ceci 2010; De Martino et al. 2016; Almirón et al. 1992; Calhoun and Kwon 2011). During starvation, Dps is very active and can greatly alter the structure of bacterial DNA. Its structure (Grant et al. 1998) and interaction with DNA have recently been studied in vitro (Grant et al. 1998; Frenkiel-Krispin et al. 2004) and in silico (Tereshkin et al. 2019a, b). DPS is a dodecamer and consists of 12 identical chains (Grant et al. 1998). The structure is deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) – 1dps.pdb.

Most cells (up to 99.98%) in populations starving for a long time undergo autolysis. The remaining cells (0.02%) develop into dormant forms (Bukharin et al. 2005; Loiko et al. 2020b).

Under starvation stress, maintaining order in a dynamic way becomes impossible (cellular processes become inefficient, and metabolism is almost absent); bacteria activate another, energy-independent mechanism for maintaining ordering and protecting vital structures (DNA) – the creation of stable molecular structures, as in inanimate nature (Minsky et al. 2002). Survivors, with the help of the physical mechanisms of DNA protection, the cells become dormant.

Quite new structures (new DNA architecture) can be expected for dormant cells compared to growing cells. The following sections are devoted to the experimental results of studying the structural organization of condensed DNA in dormant cells (starvation stress).

Structural response to stress and X-ray diffraction

One of the mechanisms of the structural response to starvation stress is the intracellular crystallization of DNA with the Dps protein. DNA crystallization provides physical protection of DNA (due to the dense packing of DNA with protein in a nanocrystal) from damage and the potential ability to resume the metabolic activity of bacterial cells in a fresh environment. Other types of structural response to starvation stress are described in the “Alternative types of DNA condensation in dormant cells” section. Diffraction of synchrotron radiation in E. coli BL21-Gold (DE3) bacterial cells transformed with the pET-Dps plasmid and subjected to induction of increased expression of the Dps protein (Krupyanskii et al. 2018; Reich et al. 1994) shows the presence of interference patterns of the type shown in Fig. 2 (inset).

Fig. 2.

Scattering intensity vs. angle 2Θ for E. coli gold strain. Intracellular crystallization of DNA with Dps (Krupyanskii et al. 2018)

For the purpose of a detailed analysis of these data, the dependences of the scattering intensity on the scattering angle 2θ were plotted by averaging 2D (two-dimensional) diffraction patterns over the azimuthal angle. Zones of increased intensity were found with periods of the crystal structure of approximately 90 Å and 45 Å, in contrast to control cell samples, where no areas of increased intensity were observed. See Krupyanskii et al. (2018) and Reich et al. (1994) for details. The first broad peak lies in the region of 90–93 Å. The diameter Dps of the dodecamer is about 90 A; therefore, this peak can correspond to the distance between Dps layers. The second peak at 45 A may correspond to the second-order Dps-Dps diffraction or DNA-DNA distances in a densely packed DNA ensemble (Reich et al. 1994).

Shown in Fig. 2, the results of diffraction experiments indicate the presence of a periodic ordered organization (most likely crystalline) in the bacterial nucleoid with the periods indicated above.

Structural response to stress and transmission electron microscopy

Electron microscopy and electron microscopic tomography have made significant progress in the visualization of ordered DNA-Dps formations in vivo. In the stationary phase under 24-h starvation stress, DNA forms toroidal structures (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

TEM. Sequential intracellular DNA-Dps crystallization in E. coli cells under starvation stress. (A) 24 h of starvation (formation of toroids). (B) 36 h of starvation – DNA structures (red arrows) near the growing DNA-Dps crystal (blue arrow). (C) Semi-thick section of a tomogram of an E. coli cell with a nanocrystalline structure. Inset – Fourier transform of the region with a white frame. (D) Filtered DNA-Dps crystal. Insert – intensity profile along the white line on the main image. The densities corresponding to the interlayer strands of DNA are highlighted in black

For toroids originating in E. coli cells, these methods made it possible to determine the shape and size of toroidal structures (outer diameter about 150 nm and inner diameter about 50 nm (Fig. 3A) (Frenkiel-Krispin et al. 2004). Furthermore (at 36-h starvation stress), crystalline structures appear on toroidal structures (Fig. 3B). This allowed the authors to suggest that toroids play the role of a substrate for the subsequent formation of DNA-Dps crystals. Frenkiel-Krispin et al. (2004) put forward a hypothesis that DNA is localized between hexagonally packed layers of Dps in crystal, which means that the characteristic distance between DNA-DNA chains will be about 90 Å, not 45 Å, as was assumed in the “Structural response to stress and X-ray diffraction” section.

Figure 3C shows a tomogram slice of a cell with a nanocrystalline structure. The inset in Fig. 3C shows the result of a Fourier analysis of a nanocrystalline region of a cell outlined by a white border. The result of the Fourier analysis indicates the presence of a nanocrystal in this region of the cell (Loiko et al. 2020b; Moiseenko et al. 2022). The filtered DNA-Dps crystal is shown in Fig. 3D. The white inset to the figure shows the electron density intensity profile along the white line of the main image. Black indicates densities, apparently corresponding to interlayer strands of DNA (Loiko et al. 2020a, b; Moiseenko et al. 2022). The question of the exact localization and shape of DNA folding in nanocrystals in complex with Dps remains open.

DNA condensation in vitro and model systems

The experimental data obtained using synchrotron radiation diffraction and TEM do not fully agree with each other and do not provide an answer to the question of DNA conformation in the nanocrystalline regions of the cell. To find an answer to this question, it was decided to proceed as follows. It was supposed that DNA-Dps easily form crystals in vitro and that the conformation of DNA in these crystals is identical to that of DNA in intracellular crystals. To study the conformation of DNA in crystals in vitro, two methods were chosen: X-ray crystallography using synchrotron radiation as a source (Kovalenko et al. 2020) and electron microscopy (Moiseenko et al. 2019).

Let us briefly describe the results obtained by macromolecular crystallography. Despite the small size of single crystals, low symmetry (P1), relatively large lattice parameters, and weak reflections, the Mesh&Collect and ccCluster software packages made it possible to determine the structure of the Dps protein (Kovalenko et al. 2020) (in the process of determining the structure, it turned out that DNA was not visible). The structure was deposited with Protein Data Bank as 6QVX (Kovalenko et al. 2020).

For electron microscopic studies in vitro, thin single-crystal complexes were grown from small DNA (−165 bp long) with the Dps protein. The projection structures of Dps-Dps and Dps-DNA crystals were studied (Moiseenko et al. 2019). Electron microscopic studies allow us to see traces of DNA in thin (2D) DNA-Dps crystals. To explain the contradiction with X-ray diffraction data on bulk crystals, we assumed that thin 2D DNA-Dps crystals have an increased lattice constant compared to a bulk crystal, so there is space for DNA in thin crystals.

Molecular dynamics simulations have also been undertaken to study multilayer crystals of the Dps protein (Moiseenko et al. 2019; Tereshkin et al. 2019a, b, 2021) and DNA condensation in three-dimensional (3D) crystals. In multilayer (three-dimensional, 3D) crystals of the Dps protein, numerous channels are formed due to the spherical shape of the protein molecules. Presumably, DNA can fold in these channels. Most likely, the DNA-Dps crystal is formed gradually, so the DNA inside the crystal is located non-linearly, bending and passing through channels of different directions. To test this hypothesis, a model of the E. coli genomic DNA region (513 base pairs, dps gene) was constructed. Based on the performed molecular dynamics calculations, it was shown that Dps protein crystals remain stable in the presence of DNA (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

3D crystals of the E. coli Dps protein. Section of a 3D Dps crystal with a bent strand of DNA inside the channels (left) and DNA conformation inside the crystal (right)

The formation of bends inside during the transition between the channels of the crystal does not violate the structure of DNA. This means that DNA in Dps crystals can be arranged randomly, and not only as suggested by Frenkiel-Krispin et al. (2004).

Thus, the study of crystals in vitro did not live up to expectations. A clear answer about the conformation of DNA in DNA-Dps single crystals has not been obtained. Only hypothetical, moreover, not self-consistent models remain. The X-ray diffraction and TEM data so far give contradictory, at first glance, results. It is possible that DNA in Dps crystals is arranged randomly.

Alternative types of DNA condensation in dormant cells

Let us consider other condensed states of DNA in the cell in addition to intracellular DNA crystallization with Dps. In addition to nanocrystalline structures of DNA (“Structural response to stress and X-ray diffraction” and “Structural response to stress and transmission electron microscopy”), liquid-crystalline structure of DNA and folded nucleosome-like structures of DNA were also discovered (see Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Liquid crystal DNA-Dps ensembles in dormant E. coli cells. (A) E. coli Top10/pBAD-DPS, (M9 medium induced with Dps production in linear growth phase); (B) E. coli strain BL21-Gold (DE3)/pET-DPS, same conditions as in (A); (C) starving E. coli cells (Dps-null mutant, i.e., no Dps proteins), cholesteric liquid-crystalline phase of DNA is visible. DNA (in the form of nested arcs characteristic of the cholesteric phase) and ribosomes, which look like dark particles on the cell periphery, are clearly separated in phases; (D) EDS spectrum from the area in B, bounded by the orange rectangle. It is clearly seen that the content of phosphorus P is much higher than the sulfur content of S (Krupyanskii 2021)

Fig. 6.

Morphology of the DNA-Dps folded nucleosome-like structure in dormant E. coli cells. (A) TEM image of the cell. (B) Tomogram slice revealing the DPS spherical associates. (C) 3D model of the spherical associates. Bar size: 55 nm (Moiseenko et al. 2022)

Liquid crystal structures were found in all populations of E. coli cells: both with the dps gene and without the dps gene (Dps-null), i.e., in the absence of the Dps protein in the cell. In some cells, DNA appears as a cholesteric liquid crystal (Fig. 5A,C). Packaging of DNA in the liquid crystal phase reduces the accessibility of DNA molecules to various damaging factors, including irradiation, oxidizing agents, and nucleases (Minsky et al. 2002). The cage in Fig. 5B has an isotropic liquid crystal type of DNA condensation (Ilca et al. 2019; Speir and Johnson 2012). DNA in the cell in Fig. 5C has a distinct cholesteric order (Minsky et al. 2002) (a cell without the dps gene (Dps-null)). DNA is arranged in the form of nested arcs characteristic of the cholesteric phase; ribosomes look like dark particles and are located on the cell periphery. A small amount of sulfur (S) compared to phosphorus (P) (Fig. 5D) reflects a small amount of Dps in the liquid crystal phase in Fig. 5B. Note that the liquid crystal type of DNA condensation is the only case (except for DNA toroids) for which it is easy to visualize DNA in a dormant cell (especially for the Dps-null strain) since Dps is either low (Fig. 5A,B) or Dps is completely absent (Fig. 5C). Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was used to detect and position the elements we need in our chosen areas of the cell (Fig. 5D). Most peaks of EDS spectrum are X-rays given off as electrons return to the K electron shell (K-alpha (or Kα) lines. For example, the Kα (2.307 keV) S (sulfur) peak reflects the existence of the DNA-binding protein Dps (each Dps protein contains 48 methionines), and the Kα (2.013 keV) P peak corresponds to phosphorus in DNA. The simultaneous presence of both peaks in the spectra of the structure indicates the formation of a DNA-Dps complex. Representative EDS spectra are shown in Fig. 5D. The relative atomic composition of different regions of the samples is proportional to the intensity of the EDS peaks.

Of particular interest is the third type of ordered structure, which was first discovered in dormant E. coli cells (Loiko et al. 2020a): a folded nucleosome-like structure (see Fig. 6). In all studied populations (except for the Dps-null mutant), both with and without excessive Dps production, the cytoplasm from 5 to 25% of cells is filled with many spherical structures (Fig. 6A) with an average diameter of 30 nm. Tomographic studies (Fig. 6B) demonstrated that these structures are not toroids (Fig. 3A), as described in the literature (Minsky et al. 2002; Blinov et al. 2015; Vasilevskaya et al. 1997), but they are almost spherical formations. By analogy with DNA folding in eukaryotes, we called this type of DNA condensation a “folded nucleosome-like” structure (Loiko et al. 2020a). Elemental analysis shows that spherical aggregates do contain S and P (phosphorus) peaks, indicating the presence of DNA-Dps associates (Loiko et al. 2020a).

In bacterial cells, the spherical formations of Dps molecules (see Fig. 7) can apparently act similarly to histones on which DNA wraps (histone-like behavior).

Fig. 7.

The comparison of pro- and eukaryotic DNA compactization. Top: schematic–eukaryotic nucleosomes (histone proteins wrapped with DNA) fold up into 30 nm fibrils that, in turn, are compressed to produce fiber and chromosomes, which protect the DNA from external factors. Bottom schematic–prokaryotes do not have defined chromosomes, but the DNA is folded around the Dps molecules to form “beads on the string” first; these could fold into spherical aggregates 30 nm in diameter and, further, into a globule-like structure, which effectively protects the nucleoid DNA from stresses (Loiko et al. 2020a)

DNA can also pass through the spherical formations of Dps beads, forming “beads on a string” (Fig. 7). To counteract external stress factors, these formations must be densely located on bacterial DNA. In addition, as in the case of eukaryotic cells, where nucleosomes fold to form fibrils, which, when folded further, form the chromatin of the chromosome, the beads on the thread can, by multiple folding, form a compact structure like a folded globule (Fig. 7). A schematic representation of the formation of a folded nucleosome-like structure can be seen in Fig. 7. External Dps molecules can adhere to the globule and additionally protect DNA (Loiko et al. 2020a).

On the heterogeneity of DNA condensation in dormant E. coli cells

There is a long-standing contradiction between the concepts of a bacterial multicellular system, as a collection of identical unicellular bacteria, identical to each other and not interacting with each other, and a bacterial culture, which considers a microbial population as a multicellular organism. In the latter case, all cells are not identical to each other; they are characterized by physiological and morphological heterogeneity. Cells interact with each other within the body. (See Shapiro (1988) and Bukharin et al. (2005) for details.) Different types of DNA condensed states that we found (see “Structural response to stress and transmission electron microscopy” and “Alternative types of DNA condensation in dormant cells” sections and table 1 by Loiko et al. (2020b)) in the studied dormant E. coli cells (or the heterogeneity of DNA condensation) provide additional arguments in favor of the concept that considers the microbial population as a multicellular organism. In addition, this observation supports the conclusion that the structure of condensed DNA corresponds to a long-lived intermediate, partially equilibrium state. This observation also testifies in favor of the fact that DNA condensation occurs in the cell according to a mechanism close to the mechanism of formation of a folded (fractal) globule.

Structure of condensed DNA under the influence of the chemical analog of the autoinductor of anabiosis 4-hexylresorcinol

The action of 4-hexylresorcinol (4-HR) on a state of a cell

Several studies (Bukharin et al. 2005; Suzina et al. 2001) have shown that the addition of the chemical analog of the autoinducer of anabiosis 4-HR at low concentrations (up to 10–4 M) to a population of stationary cell E. coli led to the formation of forms with increased stress resistance (the ability to maintain viability for a longer time than in control bacteria obtained under the same conditions, but not exposed to 4-HR).

A dormant anabiotic (practically complete absence of metabolism) state, resembling the dormant state of cells under starvation stress, appears when 4-HR is further added to a level of 10−4 M into the cell culture (Bukharin et al. 2005; Suzina et al. 2001).

With the further addition of 4-HR introduced into the cell suspension, the number of viable cells drops sharply. Bacteria lose their viability (complete absence of metabolism) at 10−3 M of 4-HR (Suzina et al. 2001). However, these non-viable cells retain their external shape during an observation period of about three years under conditions favorable to autolysis. These cells were named mummified cells or micromummies (Bukharin et al. 2005; Suzina et al. 2001). The cell walls of such bacteria thickened (Suzina et al. 2001).

Structural response to the action of 4-hexylresorcinol and X-ray diffraction

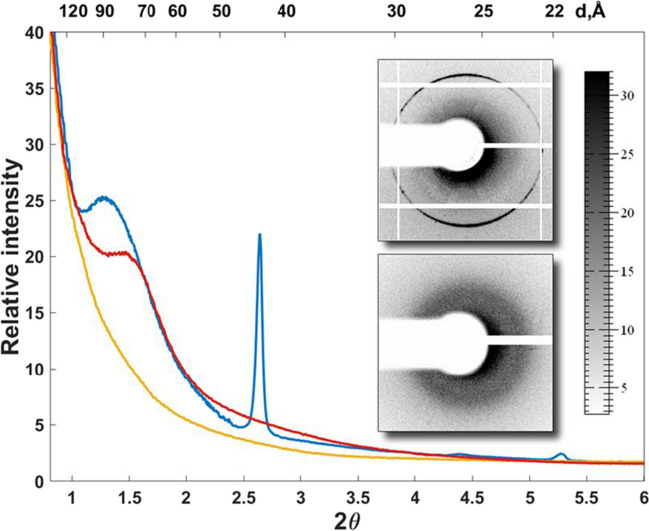

Figure 8 shows the scattering curves of synchrotron radiation for cells exposed to 4-HR at concentrations of 2× 10–4 M (blue curve) and 10–3 M (red curve). The scattering curve from a growing population of cells, which in our case was taken as a reference (control) curve, relative to which all observed diffraction effects were considered, is shown in this and subsequent figures in yellow.

Fig. 8.

Scattering intensity vs. 2Θ for E. coli strain gold, stationary growth phase, 4-HR was added at a concentration of 2 × 10–4 M, the anabiotic state of the cell (blue curve), and 4-HR at a concentration of 10–3 M, the mummified state (red curve). The yellow curve is the scattering intensity for the phase of active growth. The insets show diffraction patterns for the anabiotic and mummified states of cells (Krupyanskii et al. 2023)

The intensity of scattering from E. coli cells in the stationary growth phase exposed to 4-HR at a concentration of 2 × 10–4 M (blue curve in Fig. 8) is identical in shape to the curve obtained from cells under starvation stress (see Fig. 2). The curve shows peaks corresponding to a resolution of 44 Å and 22 Å and a broad peak with an intensity maximum at a resolution of 90 Å. Such a coincidence of the curves allows us to suggest that the structure of the condensed DNA inside the anabiotic and dormant (starvation stress) cells is identical, and that the same proteins (that is, the Dps protein) are involved in the formation of protective crystal structures.

With an increase in the concentration of 4-HR to 10–3 M, the effect on cells is significantly different from that previously observed.

Such a concentration of 4-HR leads to the formation of micromummial cells (Suzina et al. 2001). The scattering curve from such cells (red curve in Fig. 8) has a small broad peak with an intensity maximum corresponding to a resolution of 77 Å. There are no diffraction peaks corresponding to nanocrystalline structures like the curves for the anabiotic dormant state on the scattering curves from cells exposed to 4-HR at a concentration of 10–3 M.

Study of the dynamics of activation and germination of anabiotic forms of E. coli

Figure 9 shows the results of studying the dynamics of activation and germination of anabiotic forms of E. coli. Scattering from anabiotic cells contains sharp Bragg peaks at 44 Å and 22 Å and a broad peak at 88 Å (Fig. 9A). When anabiotic E. coli cells are placed in a nutrient medium for 1.5 h, there is almost an exact coincidence of the scattering curves from the control population (growing cells) and from anabiotic cells in the nutrient medium. The germinated cells were then allowed to stand for 14 h (Fig. 9C). The scattering curve does not change the monotonicity of the character, but the scattering intensity increases noticeably. For cells kept for 96 h, starvation stress begins to show (Fig. 9D). Nanocrystalline formations reappear (Fig. 9D), and the scattering intensity peaks are almost identical in shape and position to the peaks obtained from anabiotic cells (Fig. 9A).

Fig. 9.

Dynamics of activation and germination of anabiotic forms of E. coli obtained under the action of 4-HR (A). Yellow curves, growing cells; blue curves, cells exposed to 4-HR at a concentration of 10–4 M (at stationary growth phase); (B) 1.5 h in a nutrient medium; (C) 14 h in a nutrient medium; (D) 96 h in a nutrient medium (starvation stress) (Krupyanskii et al. 2023)

The coincidence of the scattering curves once again indicates the identity of the architecture of DNA within anabiotic and dormant (starvation stress) cells, and that the same Dps protein is involved in the formation of protective nanocrystalline structures.

Structural response to the action of 4-hexylresorcinol and transmission electron microscopy

Figure 10A shows transmission electron microscopy data for an Escherichia coli cell after the introduction of 4-HR into the culture at a concentration of −2 10–4 M.

Fig. 10.

A Morphology of DNA-Dps nanocrystals in E. coli cells exposed to 4-HR at a concentration of 10–4 M in the stationary growth phase. E. coli Top10/pBAD-DPS strain growing on LB medium. Insert – Fourier transform from the area with a crystal. (B) E. coli Top10/pBAD-DPS growing on LB medium under the influence of 4-HR at a concentration of 10−3 M in the stationary growth phase (Krupyanskii et al. 2023)

The inset on the left shows the Fourier transform data for the region with the supposed nanocrystal. Fourier transform data indeed show the presence of a nanocrystalline formation in the selected region.

Figure 10B shows transmission electron microscopy data for an Escherichia coli cell after inoculation with 4-HR at a concentration of 10−3 M, corresponding to the formation of a micromummy state.

TEM data do not allow to visualize any ordered state in micromummy cells. This result agrees with the data on the diffraction of synchrotron radiation (see Fig. 8).

Summary and problems

The review presents the results of literary and original experimental studies on the structural organization of DNA in actively growing, dormant (starvation stress), anabiotic dormant, and mummified Escherichia coli cells, obtained in 2016–2023, using X-ray diffraction of synchrotron radiation, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and data from molecular dynamics modeling on the interaction of DNA with the Dps protein.

Three hierarchical tiers of structural organization of compact bacterial DNA in an actively growing cell have been identified using 3C and Hi-C molecular biology methods (Verma et al. 2019). At the highest tier (mega scale ~106 bp), DNA forms six spatially organized macrodomains with a clear territorial organization into which the bacterial nucleoid is divided. These studies of the spatial organization of condensed DNA in an actively growing cell drew attention to the fractal globule as a structural model of chromatin at the mega scale (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009). The fractal globule model does not fully agree with all currently available experimental data (Iashina and Grigoriev 2019). However, the striking territorial organization and the ability of any region of the DNA globule to quickly and easily unfold, becoming accessible to the transcriptional and other protein mechanisms of the cell, makes the fractal globule one of the most attractive models of large-scale DNA packaging in the cell. This model has an important property: The structure of condensed DNA corresponds to a long-lived intermediate, partially, rather than globally, equilibrium energy state (Mirny 2011). Therefore, DNA in different cells of a bacterial colony can be condensed differently; that is, DNA packaging is heterogeneous.

In the stationary phase of growth, cells begin to experience starvation stress. If the stress of starvation persists, the formation of dormant forms occurs. As cells transition into a dormant state (almost complete absence of metabolism), the usual biochemical methods of protecting DNA cease to work. Cells, adapting to new conditions, are forced to use the physical mechanisms of DNA protection. Completely new DNA structures could be expected in dormant cells compared to growing cells. New condensed DNA structures in dormant cells under starvation stress were found. These are nanocrystalline, liquid crystal, and folded nucleosome-like structures of condensed DNA.

The detection of different structures in the ensemble of cells confirms the heterogeneity of DNA packaging in different cells. From these observations, as well as from the analysis of the data presented in publications (Krupyanskii and Goldanskii 2002; Krupyanskii 2021; Shaitan 2023), we can draw an important conclusion that nature often uses partially, rather than globally, equilibrium energy states. For proteins, upon careful consideration of the self-organized spatial structure (3D-fold), one can detect local energy minima or conformational substates (Krupyanskii and Goldanskii 2002). For DNA, as a result of self-organization, the packaging in different cells of the population turns out to be unequal and heterogeneous.

Under the action of another stress factor on the cell culture, a chemical analog of the anabiosis autoinducer 4-hexylresorcinol (4-HR), it turns out that 4-HR is the initiator of the cell transition to the anabiotic and mummified states.

Anabiotic dormant cells have the same diffraction peaks at the same resolutions which was observed earlier for dormant cells (starvation stress) and associated with the nanocrystalline state of condensed DNA. The coincidence of the scattering curves leads to the idea of the identity of the structure of condensed DNA inside an anabiotic and dormant (starvation stress) cell, and that the same Dps protein is involved in the formation of protective nanocrystalline structures.

The mummified state (the complete absence of metabolism, but with the preservation of the shape of the cell) is very different in structure from the anabiotic state. In the mummified state, intracellular nanocrystalline structures characteristic of the anabiotic dormant state are not observed. Apparently, this is the result of the fact that the mummified state is much closer to the state of thermodynamic equilibrium with maximum entropy (or disorder; see Schrodinger (2013)) than the anabiotic dormant state.

Let us move on to the problems. X-ray study (Figs. 2, 8, and 9) allows to assert only the presence or absence of ordering in the sample under study. These data, however, contain information about the bulk 3D structure of DNA in the cell. Transmission electron microscopy and tomography have made significant progress in the visualization of ordered DNA. The TEM method, however, studies the structure of DNA in thin 2D sections. Therefore, the TEM method can only visualize the structures belonging to the lower (first) hierarchical level of DNA compaction. This, of course, is not enough to describe the bulk 3D structure of the nucleoid. Nevertheless, it turned out that it is possible to visualize toroidal structures and liquid crystal structures (see Figs. 3A and 5), that is, structures in which there is either no or a very small amount of the DPS protein.

Observation of the conformation of DNA in nanocrystals (see Fig. 3C,D) so far has been inconclusive. A similar challenge occurs in the rarer case when DNA condenses with Dps (under the stress conditions) into a folded nucleosome-like structure (see Fig. 6). The reason is the following: In nanocrystalline and folded nucleosome-like structures, DNA is poorly visualized by the usual transmission electron microscopy and tomography; the Dps protein hinders not only the availability of DNA molecules to various damaging factors but also DNA visualization. It was possible to observe only traces of DNA rather than DNA itself. Additional attempts to define the conformation of DNA in DNA-Dps crystals growing in vitro were performed. Only the traces of DNA can be detected in thin 2D crystals of DNA-Dps (Moiseenko et al. 2019; Kovalenko et al. 2020). Crystals in the cell are large (≥400 nm) and much closer to bulk crystals than to 2D crystals. Thus, it is not completely correct to directly transfer the results obtained for 2D crystals grown in vitro to large intracellular crystals.

The simplest hypothesis (Frenkiel-Krispin et al. 2004) that DNA is localized between hexagonally packed layers of Dps in crystal seems to be very close to the truth if you look at Fig. 3D. It means that the characteristic distance between DNA-DNA chains will be about 90 Å, but not 45 Å, as was assumed from X-ray data (“Structural response to stress and X-ray diffraction”).

Molecular dynamics simulations (Tereshkin et al. 2019b, 2021) show that the formation of bends inside during the transition between the channels of the crystal does not violate the structure of DNA. This means that DNA in Dps crystals can be arranged randomly, and not only as suggested by Frenkiel-Krispin et al. (2004).

Thus, at present, no convincing observation of DNA conformation exists even in intracellular DNA-Dps crystals, to say nothing about nucleosome-like structure.

Research outlook and possible solution

The 20th century was the century of X-ray diffraction analysis. The structure of many molecules, including protein and DNA macromolecules, has been determined using X-ray diffraction analysis. All molecules that could be crystallized into relatively large crystals have been investigated and their structure determined. However, for macromolecules that form small crystals of a few microns in size, the determination of the structure is already a difficult task. Now, studies of the structures of non-crystalline objects, such as viruses and cells, are coming to the fore. Recent advances in imaging techniques give hope that the path to high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) imaging of condensed DNA in vivo will be found and completed in the foreseeable future. Nanovisualization and nanotomography methods used at the ESRF-EBS synchrotron (Grenoble, France) make it possible to quantify the 3D structure and elemental composition of samples in their natural state (Procopio et al. 2019). Using nanofluorescence spectroscopy and nanotomography, it is possible to study the 3D distribution of phosphorus and, consequently, DNA throughout the cell (Santos et al. 2019). Unfortunately, the spatial resolution of this method currently does not exceed 20 nm. The development of the nano-imaging method leads to the creation of the X-ray microscope. So far, this is a picture of the future, but researchers in this field are already using the term “X-ray microscopy.” The methods of electron microscopy are developing rapidly. In Ou et al. (2017), an improved DNA detection method using a fluorescent dye was used to visualize chromatin in situ. The method is called ChromEM or ChromEMT tomography. ChromEMT made it possible to determine the structure and three-dimensional organization of chromatin strands.

It can be assumed that the solution to the problem posed in the review to determine the spatial conformation of DNA in actively growing and dormant cells may be approached using modern methods of X-ray nanotomography and ChromEMT. The methodological advances described above will facilitate high-resolution visualization of the DNA architecture in the near future. This will be done first for an actively growing cell. Then, one of the most interesting questions about how the external environment (e.g., starvation stress and 4-HR) affects the 3D architecture of the nucleoid will be answered.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my colleagues, N.G. Loiko, V.V. Kovalenko, O.S. Sokolova, A.V. Moiseenko, A.A. Generalova, K.B. Tereshkina, E.V. Tereshkin, G.I. El Registan, and V.N. Popov, for great contribution to the research and I.V. Gordeeva for valuable help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author contribution

The concept and design of this review belong to the author. Preparation of the material and collection and analysis of data were carried out by Krupyanskii Yu. F. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Krupyanskii Yu. F. The author read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author is grateful for financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation. The work was carried out within the framework of the state task of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russia for Semenov Federal Research Center for Chemical Physics (Subject FFZE-2022-0011, No. 122040400089-6)

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Almirón M, Link AJ, Furlong D, Kolter R. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. Genes. 1992;6:2646–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinov VN, Golo VL, Krupyanskii Y. Toroidal conformations of DNA molecules. Nanostruct Math Phys Model. 2015;12:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield VA. DNA condensation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:334–341. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(96)80052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukharin OV, Gintsburg AL, Romanova YuM, El’-Registan GI (2005) Bacterial survival mechanisms. Meditsina, Moscow [in Russian]

- Calhoun LN, Kwon YM. Structure, function and regulation of the DNA-binding protein Dps and its role in acid and oxidative stress resistance in Escherichia coli: a review. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:375–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiancone E, Ceci P. Role of Dps (DNA-binding proteins from starved cells) aggregation on DNA. Front Biosci. 2010;15:122–131. doi: 10.2741/3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Martino M, Ershov D, van den Berg PJ, Tans SJ, Meyer AS. Single-cell analysis of the Dps response to oxidative stress. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:1662–1674. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostie J, Richmond TA, Arnaout RA, Selzer RR, Lee WL, Honan TA, Rubio ED, Krumm A, Lamb J, Nusbaum C, Green RD, Dekker J. Chromosome conformation capture carbon copy (5C): a massively parallel solution for mapping interactions between genomic elements. Genome Res. 2006;16:1299–1309. doi: 10.1101/gr.5571506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkiel-Krispin D, Ben-Avraham I, Englander J, Shimoni E, Wolf SG, Minsky A. Nucleoid restructuring in stationary-state bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:395–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennes PGD. Scaling concepts in polymer physics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Grant RA, Filman DJ, Finkel SE, Kolter R, Hogle JM. The crystal structure of Dps, a ferritin homolog that binds and protects DNA. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:294–303. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosberg AY, Khokhlov AR. Statistical physics of macromolecules. New York: AIP; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grosberg AY, Nechaev SK, Shakhnovich EI. The role of topological constraints in the kinetics of collapse of macromolecules. J Phys. 1988;49:2095–2100. doi: 10.1051/jphys:0198800490120209500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iashina EG, Grigoriev SV. Large-scale structure of chromatin: a fractal globule or a logarithmic fractal? J of Exp and Theor Phys. 2019;129(3):455–458. doi: 10.1134/S106377611908017x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilca SL, Sun X, El Omari K, Kotecha A, de Haas F, DiMaio F, et al. Multiple liquid crystalline geometries of highly compacted nucleic acid in a dsRNA virus. Nature. 2019;570:252–256. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko V, Popov A, Santoni G, Loiko N, Tereshkina K, Tereshkin E, Krupyanskii Y. Multi-crystal data collection using synchrotron radiation as exemplified with low-symmetry crystals of Dps. Acta Cryst. 2020;76:568–576. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X20012571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupyanskii YF. Architecture of nucleoid in the dormant cells of Escherichia coli. Rus J of Phys Chem. 2021;15(2):326–343. doi: 10.1134/S199079312102007X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krupyanskii YF, Generalova AA, Kovalenko VV, et al. DNA condensation in bacteria. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2023;17(3):517–532. doi: 10.1134/S199079312303021122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krupyanskii YF, Goldanskii VI. Dynamical properties and energy landscape of simple globular proteins. Physics-Uspekhi. 2002;45(11):1131–1151. doi: 10.1070/PU2002v045n11ABEH001145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krupyanskii YF, Loiko NG, Sinitsyn DO, Tereshkina KB, Tereshkin EV, Frolov IA, et al. Biocrystallization in bacterial and fungal cells and spores. Crystallogr Rep. 2018;63:594–599. doi: 10.1134/S1063774518040144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E, Van Berkum NL, Williams L, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiko N, Danilova Y, Moiseenko A, et al. Morphological peculiarities of the DNA-protein complexes in starved Escherichia coli cells. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0231562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiko N, Danilova Y, Moiseenko A, Kovalenko V, Tereshkina K, El-Registan GI, Sokolova OS, Krupyanskii YF (2020b) Morphological peculiarities of DNA-protein complexes in dormant Escherichia coli cells, subjected to prolonged starvation condensation of DNA in dormant cells of Escherichia coli. bioRxiv Cell Biol https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.27.011494v1. Accessed June 2023

- Minsky A, Shimoni E, Frenkiel-Krispin D. Stress, order and survival. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:50–60. doi: 10.1038/nrm700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirny LA. The fractal globule as a model of chromatin architecture in the cell. Chromosome Res. 2011;19:37–51. doi: 10.1007/s10577-010-9177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseenko A, Loiko N, Sokolova OS, Krupyanskii YF. Application of Special electron microscopy techniques to the study of DNA – protein complexes in E. coli cells. In: Peeters E, Bervoets I, editors. Prokaryotic Gene Regulation. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York: Humana; 2022. pp. 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseenko A, Loiko N, Tereshkina K, Danilova Y, Kovalenko V, Chertkov O, Feofanov AV, Krupyanskii YF, Sokolova OS. Projection structures reveal the position of the DNA within DNA-Dps co-crystals. Biochem. Biophys Res Commun. 2019;517(3):463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou HD, Phan S, Deerinck TJ, Thor A, Ellisman MH, O’Shea CC (2017) ChromEMT: visualizing 3D chromatin structure and compaction in interphase and mitotic cells. Science 357(6349, eaag0025). 10.1126/science.aag0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Procopio A, Malucelli E, Pacureanu A, et al. Chemical fingerprint of Zn–hydroxyapatite in the early stages of osteogenic differentiation. ACS Cent Sci. 2019;5:1449–1460. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich Z, Wachtel E, Minsky A. Liquid-crystalline mesophases of plasmid DNA in bacteria. Science. 1994;264(5164):1460–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.8197460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S, Yang Y, Rosa M, et al. The interplay between Mn and Fe in Deinococcus radiodurans triggers cellular protection during paraquat-induced oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17217. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53140-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodinger E. What is life? The physical aspect of the living cell with mind and matter: Cambridge University Press, New York; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shaitan KV. Why does a protein fold into a unique 3-d structure? And not only this. Rus J of Phys Chem. 2023;42(6):40–62. doi: 10.31857/S0207401X23060109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JA. Bacteria as multicellular organisms. Sci Am. 1988;258(6):82–89. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0688-82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonis M, Klous P, Splinter E, Moshkin Y, Willemsen R, de Wit E, van Steensel B, de Laat W. Nuclear organization of active and inactive chromatin domains uncovered by chromosome conformation capture-on-chip (4C) Nat Genet. 2006;38:1348–1354. doi: 10.1038/ng1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinitsyn DO, Loiko NG, Gularyan SK, Stepanov AS, Tereshkina KB, Chulichkov AL, et al. Biocrystallization of bacterial nucleoid under stress. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2017;11:833–838. doi: 10.1134/S1990793117050128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speir JA, Johnson JE. Nucleic acid packaging in viruses. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonington OG, Pettijohn DE. The folded genome of Escherichia coli isolated in a protein-DNA-RNA complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68(1):6–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzina NE, Mulyukin AL, Loiko NG, Kozlova AN, Dmitriev VV, Shorokhova AP, Gorlenko VM, Duda VI, El’-Registan GI (2001) Fine structure of mummified cells of microorganisms formed under the influence of a chemical analogue of the anabiosis autoinducer. Microbiology 70(6):667–677. 10.1023/A:1013183614830 [PubMed]

- Tereshkin EV, Tereshkina KB, Kovalenko VV, Loiko NG, Krupyanskii YF. Structure of DPS protein complexes with DNA. Russ J Phys Chem B. 2019;13:769–777. doi: 10.1134/S199079311905021X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tereshkin E, Tereshkina K, Loiko N, et al. Interaction of deoxyribonucleic acid with deoxyribonucleic acid-binding protein from starved cells: cluster formation and crystal growing as a model of initial stages of nucleoid biocrystallization. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37(10):2600–2607. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1492458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tereshkin EV, Tereshkina KB, Krupyanskii YF. Molecular dynamics of DNA-binding protein and its 2D-crystals. J Physics: Conf Ser. 2021;2056(1):012016. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/2056/1/012016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko AG. Molecular mechanisms of stress responses in microorganisms. Yekaterinburg: UrO RAN; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Trun N, Marko J. Architecture of a bacterial chromosome. Am Soc Microbiol News. 1998;64(5):276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilevskaya VV, Khokhlov AR, Kidoaki S, Yoshikawa K. Structure of collapsed persistent macromolecule: toroid vs. spherical globule. Biopolymers. 1997;41:51–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199701)41:1<51::AID-BIP5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma SC, Qian Z, Adhya SL. Architecture of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(12):e1008456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer C. Microcosm: E. coli and the new science of life. New York: Pantheon Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zwietering MH, Jongenburger I, Rombouts FM, Van 'T Riet K (1990) Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Appl Environ Microbiol 56(6):1875-1881. 10.1128/aem.56.6.1875-1881.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]