Abstract

Colombia aims to eliminate malaria by 2030 but remains one of the highest burden countries in the Americas. Plasmodium vivax contributes half of all malaria cases, with its control challenged by relapsing parasitaemia, drug resistance and cross-border spread. Using 64 Colombian P. vivax genomes collected between 2013 and 2017, we explored diversity and selection in two major foci of transmission: Chocó and Córdoba. Open-access data from other countries were used for comparative assessment of drug resistance candidates and to assess cross-border spread. Across Colombia, polyclonal infections were infrequent (12%), and infection connectivity was relatively high (median IBD = 5%), consistent with low endemicity. Chocó exhibited a higher frequency of polyclonal infections (23%) than Córdoba (7%), although the difference was not significant (P = 0.300). Most Colombian infections carried double pvdhfr (95%) and single pvdhps (71%) mutants, but other drug resistance mutations were less prevalent (< 10%). There was no evidence of selection at the pvaat1 gene, whose P. falciparum orthologue has recently been implicated in chloroquine resistance. Global population comparisons identified other putative adaptations. Within the Americas, low-level connectivity was observed between Colombia and Peru, highlighting potential for cross-border spread. Our findings demonstrate the potential of molecular data to inform on infection spread and adaptation.

Subject terms: Malaria, Population genetics, Genomics

Introduction

Colombia aims to eliminate malaria within its borders by 2030 but faces significant challenges. Although the country experienced a 25–50% reduction in malaria cases in the early 2000s, it remains one of the most malaria-endemic nations in South America1. In 2020, the combined burden of malaria in Venezuela, Brazil and Colombia accounted for more than 77% of cases in the World Health Organisation (WHO) Americas region1. Over seventy thousand malaria cases were reported in Colombia in 2022, ~ 60% of which were caused by Plasmodium vivax infection2. The parasite forms dormant liver stages (hypnozoites) that reactivate weeks to months after an initial infection to cause relapsing episodes of malaria, and these, in conjunction with persistent low-density blood-stage infections, confer high potential for P. vivax spread within and across borders. The threat of P. vivax is further compounded by the recent political crisis in neighbouring Venezuela, which has led to a major resurgence of this species in the region1. As Colombia progresses toward malaria elimination, vigilant surveillance of the residual P. vivax transmission is critical.

Plasmodium vivax epidemiology including transmission patterns, relapse dynamics and treatment efficacy remain poorly characterised in Colombia. Clinical trials suggest low rates of P. vivax chloroquine resistance, but these studies are not conducted routinely and can be difficult to interpret owing to potential confounding by relapsing infections3,4. The impact of antimalarials used to treat the co-endemic P. falciparum population on the molecular epidemiology of P. vivax in Colombia also remains unclear. To reach the ambitious malaria elimination milestones proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization and the Amazon Network for the Surveillance of Antimalarial Drug Resistance (PAHO/RAVREDA), it is paramount to generate detailed information on how the P. vivax populations are evolving and spreading within and across borders.

The inability to maintain P. vivax parasites in continuous ex vivo culture has significantly constrained our understanding of the biology and epidemiology of this species; genomic studies offer an alternative approach to generate new insights5,6. Although several genomic studies have been conducted on Colombian P. vivax isolates, all but one small study, have evaluated the pooled isolates collected across Central and South America7–9. Whilst genomic epidemiology investigations of P. falciparum in Colombia using identity-by-descent (IBD) based measures have informed on local and cross-border infection connectivity, similar approaches have yet to be applied to the in-depth analysis of in P. vivax10,11.

Using 64 Colombian P. vivax genomes (doubling the sample size of previous studies), we provide a detailed description of within-host infection relatedness in the two major foci of vivax transmission: Chocó and Córdoba. We explore IBD-based infection connectivity within Colombia and across borders in the Americas, and search for novel adaptations in drug resistance and other functions.

Methods

Study sites

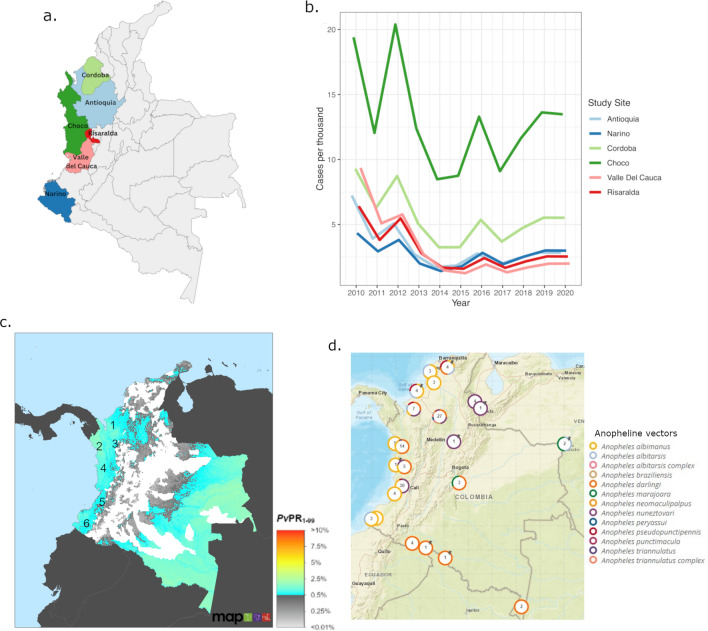

The Colombian P. vivax genomic data were derived from new and previously described patient isolates collected within the framework of clinical studies and cross-sectional surveys conducted between 2013 and 2017. Briefly, published P. vivax genomes were obtained from studies undertaken in the departments of Antioquia, Chocó, Córdoba, Nariño, Risaralda, and Valle del Cauca between 2013 and 2017 (Fig. 1a)8,12,13. Patients presenting with uncomplicated symptomatic malaria attending health care centres were invited to participate in the studies. P. vivax accounts for ~ 50% of malaria infections in the study areas, with an annual parasite incidence (API) during the study period of between 0.14 and 32.6 cases per 1000 population across the sites14. Between 2013 and 2017, Chocó presented the highest P. vivax API, followed by Cordoba (Fig. 1b). Additional information on the malaria epidemiology of the study sites is presented in Fig. 1c, which illustrates the underlying P. vivax prevalence, and Fig. 1d, which illustrates the distribution of Anopheline vectors. Colombia has four major transmission areas: a north-western region (encompassing Uraba, Sinu and Bajo Cauca, where Cordoba is located), the western Pacific coast region (including Chocó), the eastern Orinoquia region and the southernmost Amazonian Region15. Chocó and Cordoba present similar socio-economic and infrastructure conditions16,17. Malaria transmission is mostly peri-urban and high-risk areas are located near to vegetation or mining areas16,17. In the Pacific coast region, the main vectors are An. albimanus, An. nuneztovari and An. darlingi18,19. The first line policy for treating P. vivax infection in Colombia is chloroquine (CQ) at 10 mg/kg on days 1 and 2 and 5 mg/kg on day 3, and primaquine (PQ) at 0.25 mg/kg for 14 days1. Artemether-lumefantrine (AL) is used to treat P. falciparum and mixed-species P. falciparum and P. vivax infections1.

Figure 1.

Location and malaria incidence of the study sites. Panel (a) presents a map illustrating the locations of the study sites prepared using Canva (https://www.canva.com). Panel (b) presents P. vivax clinical case numbers between 2010 and 2020 in each of the study sites, using data derived from the Malaria Atlas Project (https://malariaatlas.org/trends/country/COL, accessed September 1st, 2023)77. A sharp decline in case numbers was observed between 2010 and 2015, followed by a modest increase in cases and stabilised frequency from 2019. Panel (c) presents a map of all-age P. vivax prevalence rate (PvPR1-99) in Colombia derived from the Malaria Atlas Project (https://malariaatlas.org/trends/country/COL, accessed September 1st, 2023)77. The approximate locations of the study sites are indicated with numbers; 1 Córdoba, 2 Chocó, 3 Antioquia, 4 Risaralda, 5 Valle del Cauca and 6 Nariño, illustrating localisation in vivax-endemic regions across the pacific coast. Panel (d) provides a map derived from VectorBase illustrating Anopheles species presence in Colombia (vectorbase.org/popbio-map/web, accessed September 1st, 2023)77. A range of species were reported in Chocó and Córdoba (major foci of the current study), with geographic heterogeneity observed within the departments, but An. albimanus, An. darlingi and An. nuneztovari were prevalent in both departments.

To determine cross-border infection across the Americas, and identify signals of selection in Colombia, previously published genomic data from a global collection of P. vivax isolates were derived from the Malaria Genomic Epidemiology Network (MalariaGEN) P. vivax community project Pv4 data release13. Other major populations from the Americas included Brazil, Peru and Mexico. For context in interpreting trends at drug resistance candidates, CQ + PQ is first-line treatment for P. vivax in all three countries, whereas P. falciparum and mixed-species infections are treated with AL + PQ or artesunate-mefloquine (AS-MQ) + PQ in Brazil, AS-MQ + PQ in Peru, and AL in Mexico1.

In addition to the Americas, comparative explorations of candidate drug resistance allele frequencies and signals of selection were undertaken against MalariaGEN Pv4 samples from Thailand and Papua Indonesia. The Thai population was included as a representative of a region with low-grade CQ resistance, while the Papua Indonesian population represented a region with high-grade CQ resistance20–22. The samples were collected from symptomatic patients attending outpatient clinics in Tak Province, Thailand (2006–2013) and Mimika district, Papua Indonesia (2011–2014). The frontline treatment for P. vivax infection at the time of the enrolments was CQ plus PQ in Thailand and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHP) plus PQ in Indonesia1.

Sample processing and whole genome sequencing

Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and copy number variants (CNV) data were derived from the MalariaGEN Pv4 release13. All Pv4 data originate from P. vivax-infected patient blood samples that were subject to paired-end Illumina sequencing, with the latest release reflecting a combination of new and previously described P. vivax genomes13. All sequence data were subject to the same alignment, variant calling, and genotyping processes. Briefly, human reads were removed by mapping to the human reference genome using bwa software, and the remaining reads were mapped to the P. vivax P01 v1 reference genome23,24. SNPs and small insertions and deletions (indels) were called following GATK Best Practices Workflows25,26. The resultant Variant Calling Format (VCF) file describing ~ 4.5 million variants in 1,895 worldwide P. vivax genomes is openly accessible on the MalariaGEN website (https://www.malariagen.net/data/open-dataset-plasmodium-vivax-v4.0). The Pv4 dataset also provides information on large CNVs (> 3Kbp) detected using custom Python scripts.

Prior to conducting population genetic analyses, several sample and SNP filtering steps were undertaken on the original Pv4 VCF. Samples were filtered to remove genomes with low sequence coverage, mixed-species, and apparent outliers, leaving 1,031 analysis-ready samples. The analysis-ready samples were classified by geographic region, with listings for Colombia (n = 67), Americas (n = 159), and Americas combined with Thailand and Indonesia (Asia-Americas, n = 479). The Americas dataset comprised samples from Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru. SNP filtering was performed on a VCF comprising the Asia-Americas sample set (n = 479), with country subsetting performed after. Firstly, all genotypes that were supported by less than five reads were re-coded as missing to exclude low confidence genotype calls. Two separate VCF files were then created: i) a VCF comprising candidate drug resistance determinants for analysis of resistance prevalence, and ii) a VCF comprising all (n = 911,901) high-quality bi-allelic SNPs for all other analyses. The 911,901 SNPs were further filtered to exclude monomorphic positions, leaving 430,520 SNPs (~ 47.21% retained). Next, the genotype failure distribution of samples was investigated and SNPs with excess sample failure (> 10% sample fails) were removed. This filtering step was repeated using the SNP failure distribution, removing samples with excess SNP failure, defined as > 15% SNP fails. The final (Asia-Americas) dataset comprised 427,199 SNPs across 457 samples.

Data analysis

Within-host infection diversity was initially measured using the Fws score, applying a threshold Fws ≥ 0.95 to classify infections as monoclonal27,28. Fws scores were derived from the measures provided in the Pv4 open dataset and plotted using ggplot213,29. Within each polyclonal infection, DEploid was used to derive the genetic phase of all high frequency clones (clones making up ≥ 10% of the infection)30,31 (https://github.com/DEploid-dev/DEploid). Firstly, population level allele frequencies (PLAF) were calculated from monoclonal (n = 56) and polyclonal (n = 8) Colombian samples. Monomorphic SNPs or those with missing data were removed, leaving 26,758 SNPs for analysis. A reference panel was created by first running DEploid on the monoclonal samples after marking outlier SNPs using DEploid dataExplore.r. Only clones with 99% proportion from each monoclonal sample were included in the reference panel. Haplotypes from these clones were collected and SNPs with missing data were removed, resulting in a reference panel with 56 haplotypes and 23,147 SNPs. The DEploid-BEST algorithm was then run on the polyclonal samples with the PLAF and reference panel after marking outlier SNPs, with non-default parameters of sigma = 2.0 and VQSLOD = 0 to generate haplotype estimates of high frequency clones. Using the phased haplotype reconstructions, the pairwise identity by descent (IBD) between the high frequency clones inferred by DEploid was measured using hmmIBD software, with default parameters32. Illustrative representations of the within-host diversity in the polyclonal infections were also prepared by plotting the genome-wide non-reference allele frequency (NRAF). The NRAF plots were created using custom scripts generated with R software (www.R-project.org). All other analyses were restricted to monoclonal infections to avoid potential inaccuracies from incorrect phase re-construction.

Population structure and infection relatedness were explored using ADMIXTURE, neighbour-joining, and IBD analysis32–34. The R-based ape package was used to generate distance matrices and build neighbour joining trees to illustrate infection diversity and relatedness34. hmmIBD was used to calculate IBD between infections32. The output from hmmIBD (hmm_fract) was used to estimate IBD sharing between samples with plots of infection connectivity at different IBD thresholds prepared using the R-based igraph package (https://igraph.org).

The prediction toolbox snpEff was run on the drug resistance candidate dataset to annotate the mutations35. The results were then enhanced by adding InterPro domain predictions from PlasmoDB36,37. A set of known mutations that correlate with drug resistance in P. vivax were derived from the literature38,39.

Haplotype-based tests to identify genomic regions with evidence of extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH) indicative of recent positive selection were undertaken using rehh software40. Both the integrated haplotype score (iHS) and Rsb-based cross-population EHH score were measured. Recommendations for unpolarised data were followed in accordance with the unpolarised nature of the data. A maximum of 10% missing genotypes were allowed, in line with our sample processing methods. The iHS was measured in Colombia, and Rsb was measured in comparisons between Colombia against each of the populations in the Asia-Americas data set. Prior to running rehh, in populations with evidence of large clonal expansions, a single representative sample was used for each clonal cluster to reduce the impact of structure. Clonal clusters were defined as samples sharing ≥ 95% IBD, and the sample with the lowest genotype failure was selected as the representative. In accordance with previous studies, SNP-based p-values corresponding with thresholds of iHS ≥ 4 and Rsb ≥ 5 were considered significant, and candidate signals of selection were defined as regions with a minimum of 3 significant SNPs within a 10 kb window7,41.

Ethics

All patient samples from the MalariaGEN Pv4 dataset were collected with written, informed consent from the patient or a parent or guardian for individuals less than 18 years old13. Ethical approval for patient sampling from the newly described study sites in Colombia was provided by the Comité Institucional de Ética de Investigación con Humanos del CIDEIM, Cali, Colombia (reference 08–2015) and the Comité de Bioética Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas Facultad de Medicina Universidad de Antioquia, Antioquia, Colombia (reference BE-IIM): all methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of these committees.

Results

Genomic data summary

A set of 457 (95%, 457/479) P. vivax genomes and 427,199 SNPs were selected based on sample genotyping success rate ≥ 85% and SNP genotyping success rates ≥ 90%. A subset of 142 samples, including 64 Colombian isolates, was selected for analyses within the Americas. The 64 Colombian samples included 36 new isolates from Colombia (detailed in Supplementary Data 1), and 28 previously analysed samples from Colombia8. The Colombian samples came from 6 departments (see Fig. 1), but population-level statistics were only detailed on the samples from Chocó (n = 13) and Córdoba (n = 40). Owing to small sample size (n < 10), the samples from Antioquia, Nariño, Risaralda and Valle del Cauca were only included in country-wide population statistics and spatial analyses to identify potential geographic trends.

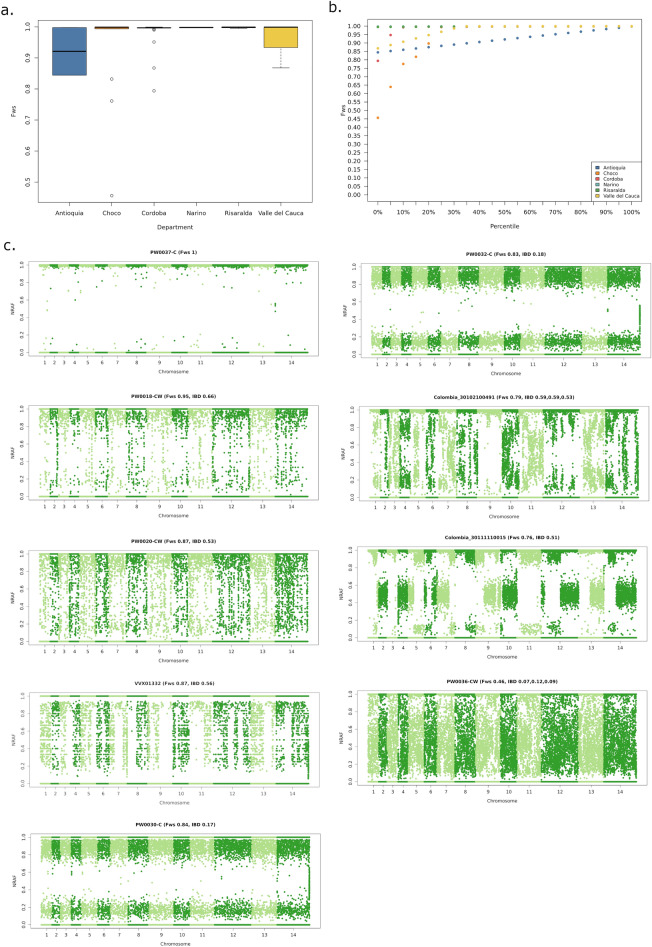

Within-host diversity in Colombia

Within-sample infection complexity was assessed using the FWS score. Initially, the commonly applied threshold of FWS ≥ 0.95 was used to define monoclonal infection, but closer inspection of the non-reference allele frequency (NRAF) distribution within infections revealed that an infection with Fws = 0.95 (PW0018-C) had evidence of multiple clones (Fig. 2c). A more stringent threshold of FWS ≥ 0.97 was therefore used to define monoclonal infection across samples in the Asia-America dataset. Across Colombia, 88% (56/64) infections had FWS scores ≥ 0.97. A lower proportion of monoclonal infections was observed in Chocó (77%, 10/13) than Córdoba (93%, 37/40), but the difference was not significant (χ2 = 1.074, p = 0.300) (Fig. 2a,b, Table 1). As illustrated in the non-reference allele frequency (NRAF) plots presented in Fig. 2c, a range of within-host diversity patterns were observed across the 8 polyclonal infections.

Figure 2.

Within-sample infection diversity. Panels (a) and (b) present box plots and percentile plots, respectively, illustrating the distribution of within-sample F statistic (FWS) scores in Colombia. Data are presented on all 64 high-quality samples. Panel (c) presents Manhattan plots of the non-reference allele frequency (NRAF) in the 8 Colombian infections identified as polyclonal based on FWS < 0.97, and 1 monoclonal infection as a baseline reference (PW0037-C). Pairwise measures of identity by descent (IBD) are indicated for pairings of the clones making up 10% or more of the given infection.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of within-host infection diversity.

| Site | Median FWS (range) | % FWS ≥ 0.97 (no./No.) | % Polyclonal infections with inter-clone IBD ≥ 0.25* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chocó | 0.999 (0.456–0.999) | 77 (10/13) | 33 (1/3) |

| Córdoba | 0.997 (0.794–0.999) | 93 (37/40) | 100 (3/3) |

| Across Colombia | 0.997 (0.456–0.999) | 88 (56/64) | 63 (5/8) |

*Requirement for a minimum of 2 clones with IBD ≥ 0.25 where infections comprise 3 or more clones at ≥ 10% frequency.

In addition to the polyclonal infections from Chocó (n = 3) and Cordoba (n = 3), one polyclonal infection was detected in Antioquia (PW0030-C, two clones with IBD = 0.17) and one in Valle del Cauca (VVX01332, two clones with IBD = 0.56).

DEploid-BEST analysis of the 8 polyclonal samples identified two infections (Colombia_30102100491 from Córdoba and PW0036-CW from Chocó) comprising 3 clones at ≥ 10% frequency. Whilst the 3 Colombia_30102100491 clones appeared to be siblings, with IBD ranging from 0.53 to 0.59, the PW0036-CW clones were more distantly related (IBD range 0.07–0.12) (Fig. 2c). The remaining infections comprised 2 clones at ≥ 10% frequency. In total, 5 (63%) polyclonal infections displayed IBD ≥ 0.25 in pairwise comparisons of at least two clones, suggesting relatedness at the half-sibling level or greater, and likely reflecting co-transmission (single mosquito inoculation) rather than superinfection (multiple inoculations). The remaining 3 infections exhibited IBD ranging from 0.07 to 0.18 (Fig. 2c). Two samples (PW0030-C and PW0032-C) displayed highly uniform NRAFs across all SNPs, consistent with highly divergent major and minor clones. In these two infections, the uniform NRAF profiles enabled accurate approximation of phase in the major (highest frequency) clones by selecting the predominant alleles at each SNP. The inclusion of the phased major clones in each of PW0030-C and PW0032-C yielded 2 additional monoclonal samples for analysis in Colombia, bringing the sample size to 58.

Infection connectivity within Colombia

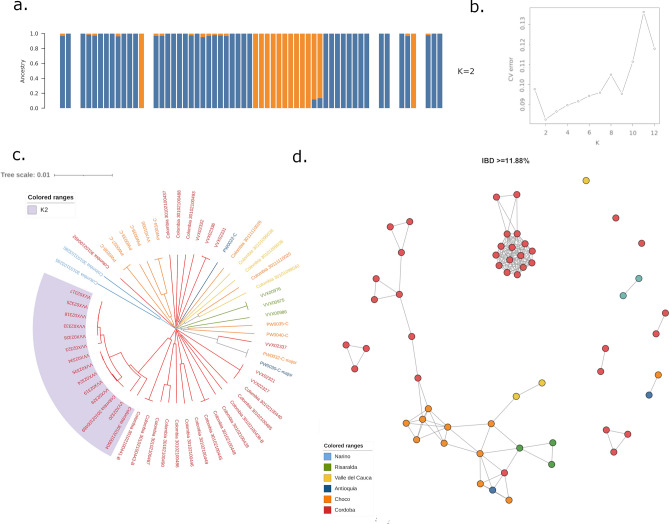

Several methods were used to investigate the structure and relatedness between infections in Colombia. Using ADMIXTURE analysis, the lowest CV error (0.082) was observed at K = 2, but minimal differences were observed between K = 1 and 7 (range 0.082–0.098) (Fig. 3b). At K = 2, 76% (44/58) samples demonstrated predominant ancestry (> 75% ancestry) to the major subpopulation (K1), and 24% (14/58) to subpopulation K2 (Fig. 3a). Majority of K2 infections derived from Córdoba, making up 32% (12/37) isolates in this department, but one K2 infection was observed in Chocó (9%, 1/11) and one in Risaralda (33%, 1/3). To investigate potential temporal determinants of the observed structure, we added information on year of collection to the samples from Chocó and Córdoba (Supplementary Fig. 1). Although the K2 subpopulation was observed in Córdoba in 2013 and 2016, it was more common in the later time point in both Chocó (100% K2 in 2016) and Córdoba (59% K2 in 2016).

Figure 3.

Infection relatedness within Colombia. Panels (a) and (b) present ADMIXTURE plots, illustrating the CV error at different values of K (panel b) and the proportionate ancestry of samples (vertical bars) to each of the two subpopulations at K = 2 (panel a). The lowest CV error was observed at K = 2; at this K, the majority of infections across Colombia had predominant ancestry to K1 (in blue), but a sizable proportion of samples from Córdoba had predominant ancestry to K2 (orange). Panels (c) and (d) illustrate a rooted neighbour-joining (NJ) tree and identity by descent (IBD)-based cluster network, respectively. Both NJ and IBD analyses demonstrate the high relatedness amongst the K2 infections, indicative of clonal expansion dynamics. The cluster network illustrates connections between infections sharing a minimum ~ 12% genomic IBD. All plots present monoclonal Colombian infections only.

Neighbour-joining (NJ) trees were prepared to visually inspect patterns of relatedness amongst the infections and further explore the substructure identified with ADMIXTURE (Fig. 3c). NJ analysis revealed multiple occurrences of infections with identical or near-identical genomes, which we refer to hereafter as clonal clusters. In total, 29 (50%) Colombian infections shared identical or near-identical genomes with at least one other infection. The largest clonal cluster comprised 6 infections, all deriving from Córdoba, but clonal clusters were also observed in other sites. There was only one observation of clone pairs across different sites, namely PW0030-C and PW0032-C from Antioquia and Chocó, respectively. Inspection of the infections by the ADMIXTURE classifications revealed that the K2 subpopulation comprised highly related infections, including the two largest clonal clusters, reflecting relatively more unstable transmission than in the more diverse K1 subpopulation. Investigation of temporal trends revealed that 3 clonal clusters comprised infections presenting in the same site but > 1 year apart (up to 3 years apart), reflecting highly persistent strains (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Since malaria parasites are recombining organisms, NJ analysis can potentially miss recent connectivity between infections where outcrossing has taken place. We therefore further investigated the connectivity between infections using measures of IBD that account for recombination. At IBD thresholds of ~ 0.12 (12%) and greater, reflecting relatively recent common ancestry (quarter-siblings and closer relatives), two large infection networks were observed (Fig. 3d). One cluster was spatially diverse, comprising 42 samples deriving from all sites except Nariño, indicative of shared reservoirs between different regions of Colombia. The second, tighter, cluster comprised 16 samples, all deriving from Córdoba and reflecting the highly related K2 infections. At increasing IBD thresholds, the spatially diverse cluster rapidly broke down, but most K2 infections exhibited connectivity > 0.5 (siblings) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Inspection of temporal trends in IBD revealed multiple closely connected (≥ 12% IBD) infection pairs that were separated by > 1 year (n = 28 samples amongst these connections), confirming the potential for high temporal stability of infection lineages (Supplementary Fig. 2).

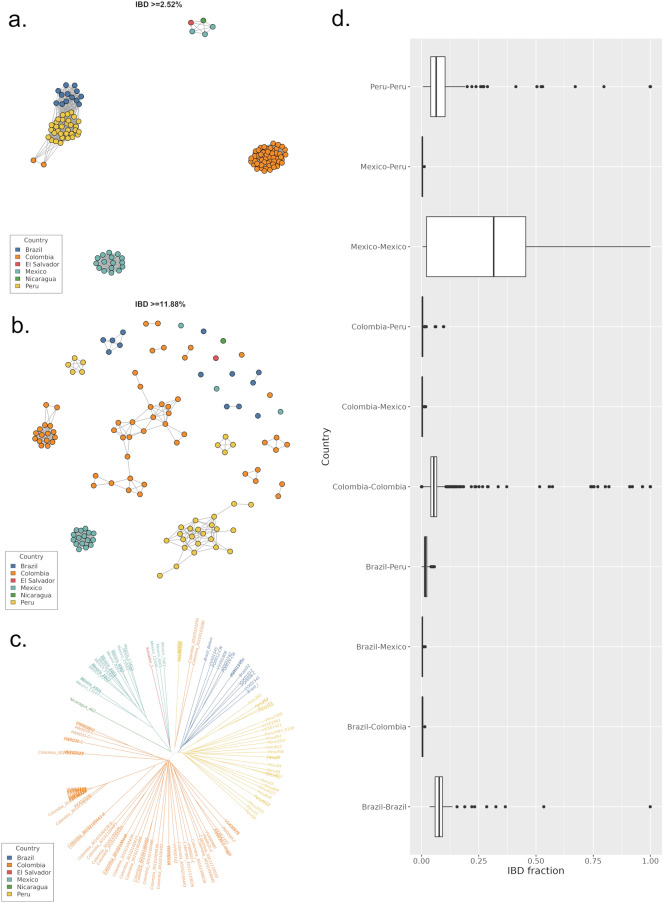

Infection connectivity between Colombia and neighbouring countries

To further investigate connectivity, we measured IBD between monoclonal P. vivax infections from Colombia and other American countries in the Pv4 dataset; Brazil (n = 13), El Salvador (n = 1), Mexico (n = 19), Nicaragua (n = 1) and Peru (n = 32). The IBD between all populations was low, with no inter-country connectivity observed at thresholds > 10% (Fig. 4a,b). At the relatively low IBD threshold of 2.5%, two infections from Nariño (2013), in the south of Colombia, (Colombia_30103103295 and Colombia_30103103280) demonstrated connectivity with four isolates from Sullana, northern Peru collected in 2011. For context, summary statistics on the IBD within and between countries were prepared, demonstrating that the ~ 2.5% IBD between the 2 Colombian and 4 Peruvian isolates was lower than the median and mean IBDs within Colombia (4% and 5% respectively) and Peru (4% and 7% respectively) (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 4.

Infection connectivity between Colombia and other populations in Central and South America. Panels (a) and (b) present IBD plots at minimum thresholds of ~ 2.5 and 12%, respectively, illustrating distant connectivity between several countries but no evidence of cousins or closer relatives across borders. Panel (c) presents an unrooted neighbour-joining (NJ) tree confirming the patterns observed with the IBD analysis, including the clustering of two Colombian infections (Colombia_30103103295 and Colombia_30103103280) with several Peruvian infections via a distant shared lineage. Panel (d) presents box plots illustrating the distribution of pairwise IBD within and between countries. As observed with the IBD and NJ analyses, IBD is generally greater within than between countries, with the greatest relatedness (lowest outcrossing) observed within Mexico. All plots present monoclonal samples from the Americas dataset only.

The accuracy of IBD estimation is dependent in part on the available data on allele frequency, and thus confounded by limited sample size in several countries, as well as the potential constraints in pooling infections across multiple countries. To account for this, NJ analysis was conducted on all infections from Central and South America and confirmed the closer relatedness between isolates Colombia_30103103295 and Colombia_30103103280 with Peruvian infections than with other Colombian infections, potentially reflecting distant cross-border infection spread (Fig. 4c).

NJ analysis was also performed on the Asia-Americas dataset, confirming previously described divergence between infections from the Americas and the Asia–Pacific region (Thailand and Indonesia), as well as the relatively higher diversity in the latter populations (Supplementary Fig. 3)13. IBD-based connectivity is also presented on the global dataset, although caution is advised in interpretation owing to biases in global allele frequency derivations (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Prevalence of drug resistance candidates in Colombia

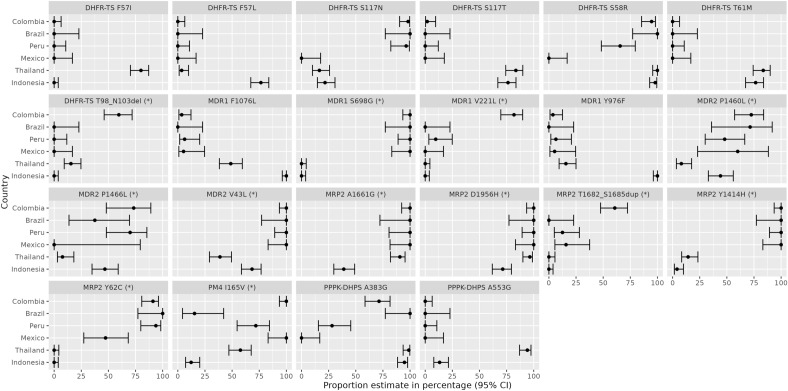

The prevalence of several candidate drug-resistance variants that have previously been associated with clinical or ex vivo antimalarial drug resistance in P. vivax was determined in Chocó, Córdoba and Colombia-wide (Table 2) 39. Country-level trends between Colombia relative to Peru, Brazil, Mexico, Thailand, and Indonesia are also illustrated in Fig. 5. The multidrug resistance 1 (pvmdr1) Y976F variant, which is a minor modulator of CQ resistance42, exhibited low prevalence in Chocó (20% (2/10)) and was absent in Córdoba (0/37), with only 4% prevalence across Colombia (2/55). At the country level, the Y976F variant was most prevalent in Indonesia. The F1076L variant, which has also been proposed as a modulator of CQ resistance42, exhibited equally low prevalence in Chocó (20% (2/10)), Córdoba (0% (0/38)) and across Colombia (4% (2/57)). Similar trends of low F1076L prevalence were observed in other American populations, but the variant was prevalent in Thailand and Indonesia. A range of mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase (pvdhfr) and dihydropteroate synthase (pvdhps) genes have been associated with antifolate resistance43. The most common pvdhfr variants observed in Colombia were the S58R and S117N mutations, giving rise to double mutants at frequencies of 80% (8/10) in Chocó, 100% (36/36) in Córdoba and 95% (52/55) across Colombia. No triple or quadruple pvdhfr mutants were observed in Colombia (0% (0/55)). At the country level, a range of patterns were observed at the pvdhfr locus, including higher prevalence of the F57I, F57L, S117T and T61M mutations in Asian relative to Central or South American populations. At the pvdhps locus, the A383G mutation was prevalent in Chocó (100% (10/10)), Córdoba (66% (25/38)) and across Colombia (72% (41/57)). No pvdhps A553G mutations were observed in Colombia (0% (0/57)). In other populations, the pvdhps A383G mutation was also prevalent in Brazil, Thailand and Indonesia, and the pvdhps A553G mutation was also infrequent in all populations except Thailand. None of the isolates had the pvmdr1 copy number amplification associated with mefloquine resistance, but this variant analysis was restricted to only 22 Colombian samples that exhibited sufficient coverage44,45.

Table 2.

Prevalence of drug resistance markers in Colombia.

| Gene | Chr | Position | Mutation | Drug | Freq, % (no./No.) | Freq, % (no./No.) | Freq, % (no./No.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | Chocó | Córdoba | |||||

| pvmdr1 | 10 | 479908 | F1076L | CQ | 4 (2/56) | 20 (2/10) | 0 (0/37) |

| pvmdr1 | 10 | 480207 | Y976F | CQ, AQ + SP | 4 (2/54) | 20 (2/10) | 0 (0/36) |

| pvmdr1 | 10 | CNV | ≥ 2 copies | MQ | 0 (0/22) | 0 (0/7) | 0 (0/15) |

| pvdhfr | 5 | 1077530; 1077532 | F57L/I | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 0 (0/56) | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/37) |

| pvdhfr | 5 | 1077533; 1077534; 1077535 | S58R | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 95 (53/56) | 80 (8/10) | 100 (37/37) |

| pvdhfr | 5 | 1077543 | T61M | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 0 (0/56) | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/37) |

| pvdhfr | 5 | 1077711 | S117N/T | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 100 (55/55) | 100 (10/10) | 100 (36/36) |

| pvdhfr | … | … | Single mutant | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 5 (3/55) | 20 (2/10) | 0 (0/36) |

| pvdhfr | … | … | Double mutant | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 95 (52/55) | 80 (8/10) | 100 (36/36) |

| pvdhfr | … | … | Triple mutant | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 0 (0/55) | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/36) |

| pvdhfr | … | … | Quadruple mutant | Antifolate, AQ + SP | 0 (0/55) | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/36) |

| pvdhps | 14 | 1270401 | A553G | Antifolate | 0 (0/56) | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/37) |

| pvdhps | 14 | 1270911 | A383G | Antifolate | 71 (40/56) | 100 (10/10) | 65 (24/37) |

Prevalence of drug resistance markers that have been associated with clinical or ex vivo drug resistance in P. vivax. Mutation prevalence was calculated with homozygous calls only. Abbreviations: CNV, copy number variation; AQ, amodiaquine; CQ, chloroquine; MQ, mefloquine; SP, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. Gene identifiers; pvmdr1 (PVP01_1010900), pvdhfr (PVP01_0526600), pvdhps (PVP01_1429500).

Figure 5.

Amino acid frequencies at selected P. vivax drug resistance candidates. Each panel presents proportions and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the given amino acid changes. Data is provided on variants that have i) previously been associated with drug resistance or ii) are non-synonymous variants located in orthologues of P. falciparum drug resistance-associated genes and exhibit substantial differences (non-overlapping CIs) in proportion between Colombia and at least one other population; the latter class of variants are denoted with (*). For variants that have previously been associated with clinical or ex vivo resistance, frequencies reflect the drug-resistant amino acid.

For reference purposes, the prevalence of other nonsynonymous variants in pvmdr1, pvdhps, pvdhfr and orthologues of several genes implicated in drug resistance in P. falciparum is provided for Colombia and the comparator populations in Supplementary Data 2. The orthologues include pvaat1 (amino acid transporter 1), pvcrt-o (chloroquine resistance transporter), plasmepsin IV, pvmrp1 and pvmrp2 (multidrug resistance–associated proteins 1 and 2), and pvmdr2 (multidrug resistance protein 2). Notable mutations that exhibited substantial differences in proportion between Colombia and at least one other population are illustrated in Fig. 5 alongside the above-described (known) drug resistance candidates. Substantial differences were observed between Colombia and all other populations in the proportion of pvdhfr T98/N103del and pvmrp2 T1682/S168dup variants. Other variants exhibited regional trends, with differences in proportion between Central and South American relative to the Asian populations observed at pvmdr1 S698G, pvmdr1 V221L, pvmdr2 V43L and pvmrp2 Y144H. A spectrum of other population trends was observed in the proportions of the pvaat1 A526dup, pvaat1 G41S, pvaat1 R19L, pvmdr2 P1460L, pvmdr2 1466L, pvmrp2 A1661G, pvmrp2 D1956H, pvmrp2 Y62C and plasmepsin IV I165V variants.

Genome-wide scans to identify new adaptations in Colombia

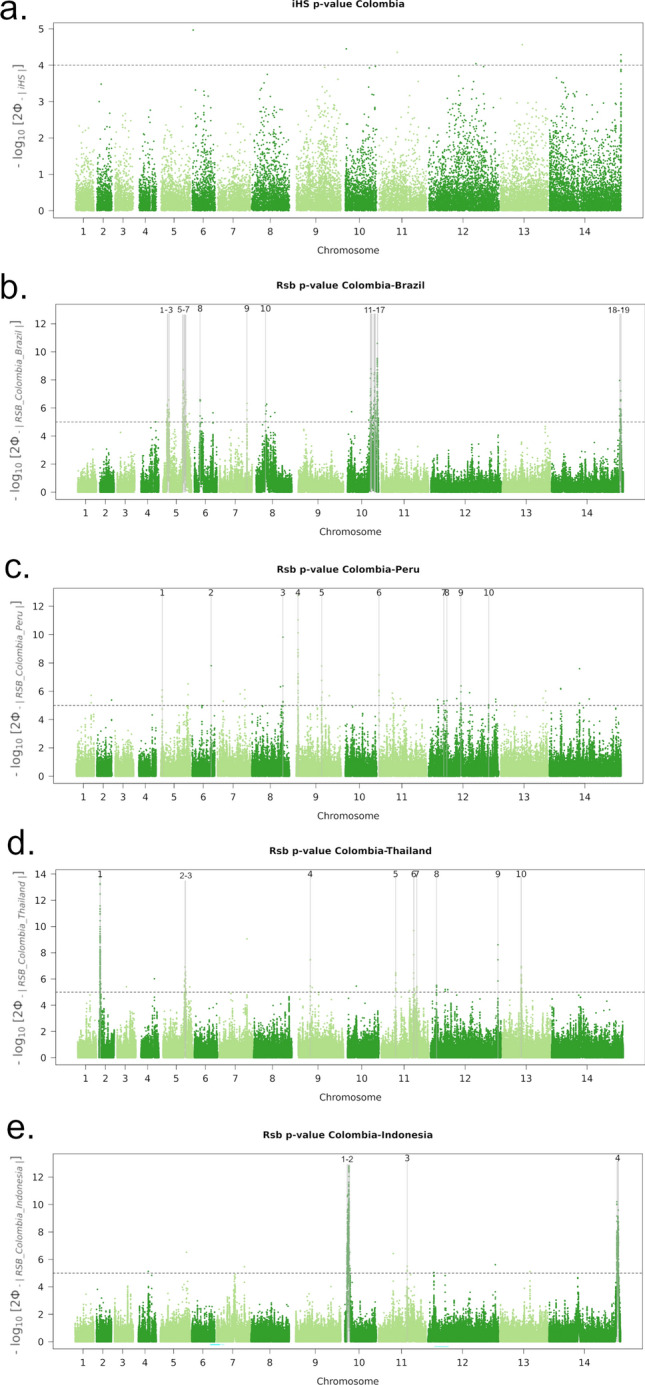

Evidence of new candidates of drug resistance and other adaptive mechanisms were explored by identifying genomic regions with evidence of relatively extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH) in Colombia. The integrated haplotype score (iHS) was applied to the Colombian dataset, and Rsb-based cross-population EHH was assessed in Colombia relative to each of the populations that have a minimum of 10 samples. Clonal clusters were represented by a single infection to reduce potential confounding by population structure, producing the following analysis sets; Colombia (n = 39), Brazil (n = 12), Peru (n = 26), Mexico (n = 17), Thailand (n = 85) and Indonesia (n = 98). A false discovery rate (FDR) significance threshold of 0.05 and fixed thresholds of -log10(p) = 4 for the iHS and 5 for Rsb were explored, revealing a high overlap in signal detection with the iHS (100%, 0/0) and Rsb (64%, 28/44). The fixed thresholds were therefore selected for defining signals to facilitate more direct comparisons with previous studies that have used the same thresholds7,41. No significant signals of selection were observed with the iHS analysis in Colombia, potentially reflecting constrained statistical power of this method to detect signals when sample size is modest (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 6.

Genome-wide scans of iHS and Rsb-based extended haplotype homozygosity in Colombia. Panel (a) presents a Manhattan plot of the iHS −log10(p) in Colombia. The dashed black line demarks a fixed significance threshold of −log10(p) = 4. There were no signals supported by a minimum of 3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) above the threshold. Panels (b)–(e) present Manhattan plots of the Rsb −log10(p) for the given populations. The dashed black lines demark a fixed significance threshold of −log10(p) = 5: signals supported by a minimum of 3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) above the threshold within 10 kb of one another are demarked with vertical dashed grey lines and numbered. Signals associated with extended haplotypes in Colombia and their putative genetic drivers include: pvmsp1 (PVP01_0728900) in region 9 in the Brazilian comparison (panel b); 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (PVP01_1262700) in region 10 in the Peruvian comparison (panel c); pyridoxine biosynthesis protein PDX2 (PVP01_0916800) in region 4 in the Thai comparison (panel d); a conserved Plasmodium protein with unknown function (PVP01_1115800) in region 5 (panel d); an oligomeric Golgi complex subunit 4 protein (PVP01_1133300) in region 6 (panel d); 6-cysteine proteins P12 (PVP01_1136400) and P47 (PVP01_1208000) in regions 7 and 8 (panel d); a metacaspase-2 (PVP01_1268600) in region 9 (panel d); and a PIMMS43 protein (PVP01_1129500) in region 3 in the Indonesian comparison (panel e). Further details are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Cross-population analyses revealed 19 regions with evidence of differential selection between Colombia and Brazil (Fig. 6b). One previously described signal appeared to be under positive selection in Colombia and encompassed pvmsp1, encoding a merozoite surface protein, a promising vaccine candidate that is involved in merozoite formation, and red blood cell invasion and egress46,47. Comparisons of Colombia relative to Peru identified 10 signals, one of which was under positive selection in Colombia and contains a 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase gene, putatively involved in cell membrane formation (Fig. 6c) 48,49. Even after excluding clonal clusters, there was extensive population structure in Mexican isolates, and thus signals of cross-population EHH against this population were not explored. Outside of the Americas, comparisons against Thailand revealed 10 signals of differential selection, including 5 regions under positive selection in Colombia (Fig. 6d). The Colombian signals reflect a variety of putative drivers including a pyridoxine biosynthesis protein PDX2, a conserved oligomeric Golgi complex subunit 4 protein, 6-cysteine proteins P12 and P47, whose P. falciparum orthologs are involved in host immune evasion, a metacaspase-2, whose ortholog has a role in malaria transmission, and a conserved Plasmodium protein with unknown function50,51. Four signals were observed against Indonesia, with one region representing selection within Colombia (Fig. 6e). This signal comprises a PIMMS43 protein, implicated in immune evasion in P. falciparum and P. berghei52.

In addition to SNPs, we sought evidence of adaptations mediated by large (> 3 kb) tandem duplications provided in the MalariaGEN Pv4 data release but found no evidence of duplications in Colombia (Supplementary Table 3)13. However, sample size may have constrained evaluation; for example, there were only 23 samples with suitable read depth at the commonly observed pvdbp1 duplication.

Discussion

Our large genomic epidemiology investigation of P. vivax in Colombia, demonstrates patterns of within-host and population diversity consistent with low endemicity between 2013 and 2017. Although this level of endemicity is conducive to timely P. vivax elimination, there is evidence of low-level shared reservoirs of infection with neighbouring countries, and presence of known drug resistance-associated variants as well as several potential new adaptations. Further details on the observed genetic patterns and their implications for P. vivax surveillance and treatment efficacy are discussed.

A major concern for the Colombian National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) is whether local interventions are effective in reducing parasite transmission. Whilst traditional entomological and parasitological measures of infection prevalence and incidence are critical, asymptomatic and subpatent reservoirs are impossible to capture with these approaches. The dormant liver stages of P. vivax further complicate measures of the burden of P. vivax53. Parasite population genetic features provide useful insights on local transmission to complement more traditional measures. For instance, high within-host infection diversity is one such feature, generally reflecting high endemicity6,53. Our finding that polyclonal infections occurred in only 12% (8/64) of Colombian isolates aligns with low rates of P. vivax transmission, comparable to Malaysia (16% polyclonal infections) during its malaria pre-elimination phase54. To put these figures in context, high transmission regions of Papua Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Greater-Mekong subregion, and Ethiopia report between 30 and 60% polyclonal infections7,8,41,55–57. Other regions of the Americas, including areas of neighbouring Brazil and Peru also exhibit lower polyclonality (13–16%) than the Asia–Pacific region47. We also observed that over 60% of the polyclonal infections in Colombia comprised closely related clones such as siblings or half-siblings (> 25% genomic IBD), suggesting recent shared parentage. Parasites with recent shared parentage are more likely to arise from a single mosquito inoculum (i.e., co-transmission of the different clones) than multiple inoculums (i.e., superinfection)30,58: under this assumption, our results infer a higher frequency of co-transmission than superinfection events in Colombia, as might be expected as transmission declines. However, using similar methods, a study in a moderately high transmission region of Ethiopia reported a similar frequency (57%) of co-transmission events41. With limited information from other endemic regions, it’s unclear the degree to which reactivated hypnozoites, as opposed to reinfections, determine within-infection relatedness patterns in P. vivax. Further research in this area using genome phasing approaches or single cell sequencing, will enable a more contextualised view of the relationship between within-host relatedness and P. vivax endemicity59. Our study provides baseline data for future comparisons to evaluate the ongoing efficacy of interventions in Colombia.

A wide variety of ecological patterns and associated malaria epidemiology have been described in Colombia, highlighting the importance of subnational interventions adapted to local needs1,14. Our investigations of within-host diversity at the departmental scale found modest evidence of heterogeneity between sites. Chocó has historically harboured high levels of malaria and is one of the priority areas for malaria elimination in Colombia. Over 60% (2/3 with within-host IBD < 0.25) of the polyclonal infections in Chocó appeared to reflect superinfections in contrast to 0% (0/3) in Córdoba. Chocó also presented a higher frequency of polyclonal infections (23%) than Córdoba (7%), but the sample size in Chocó was constrained (n = 13) and the difference was not statistically significant. Nonetheless, these trends call for ongoing monitoring of transmission reduction efficacy in Chocó. Several factors may explain the observed transmission patterns in Chocó, including the local Anopheline vectors. Typically, An. albimanus, An. nuneztovari and An. darlingi are prevalent, but their frequencies may change with seasonal variation18,19. Whilst our study was moderately granular in spatial scale, our findings highlight the potential for genetic epidemiology approaches using more high-throughput methods such as barcode genotyping to capture important infection dynamics.

Population structure and relatedness provide an additional genetic measure yielding insights into local malaria transmission dynamics53,60. A notable genetic feature in Colombia was the high frequency of closely related infections, including the large K2 cluster (n = 14 infections with IBD ≥ 50%) observed in Córdoba. This pattern indicates a high degree of inbreeding and has been observed in other low endemic P. vivax populations, including Malaysia and Panama as infection prevalence declined and opportunities for outcrossing diminished54,61. Similar patterns have also been described in the P. falciparum population in Colombia during a period when cases were declining10,62. The high degree of inbreeding, particularly in Córdoba, is therefore promising regarding Colombia’s goals of achieving malaria elimination certification. However, our data is from 2013–15 and ongoing surveillance will be critical to avoid resurgence from highly resilient or adaptive strains. Parasite populations with low levels of outcrossing may be more amenable to the emergence of drug-resistant malaria strains63. Infrequent outcrossing is favourable when supporting variants are required to overcome fitness costs of drug resistance-conferring mutations. Our study and similar P. falciparum studies in Colombia demonstrate a high potential for infection lineages to persist over multiple years in line with infrequent superinfection and hence infrequent outcrossing62. P. vivax studies in Malaysia and Panama have reported similar trends, with infections persisting up to a decade54,61.

Surveillance of P. vivax drug resistance is challenged by limited information on the molecular markers38. Amongst the few described markers of resistance, we found no evidence of the pvmdr1 copy number duplication (0% across Colombia) that has been associated with mefloquine resistance, suggesting that it may be a suitable alternative to chloroquine (as a partner drug in artemisinin combination therapies, ACTs)44,45. However, the number of samples in our study that were suitable for copy number evaluation was constrained (n = 22, 39%) and hence further surveillance is warranted. Co-endemic P. falciparum populations can potentially give insights into the extent of local drug pressure on P. vivax. Investigations of P. falciparum infections collected at a similar time and location (enrolments in the Pacific coast and Cauca River regions in 2015) identified ~ 7% prevalence of pfmdr1 copy number amplifications64. The selective pressure on pfmdr1 justifies continued close surveillance of pvmdr1 amplification in the P. vivax population, which may receive inadvertent drug pressure.

Although sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine (SP) are not currently recommended as first-line policy for any malaria species in Colombia, SP has been used to treat P. falciparum in the past, in combination with CQ (from 1981 to 1998) and AQ (from 1998 to 2008). In 2008, policy was changed to ACTs owing to widespread therapeutic failures65,66. As SP has been shown to have a positive impact on infant birth weight when used in intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp), even to some degree when P. falciparum SP resistance variants are present, there is a potential public health application for SP67. Our results show evidence of reduced SP efficacy in P. vivax in Colombia. Frequencies of the pvdhfr S58R + S117N double mutant ranged from 80 to 100%, and the pvdhps A383G mutant ranged from 66 to 100% across Colombia. However, there were no triple or quadruple pvdhfr mutants and no double pvdhps mutants, suggesting that full-grade SP resistance is not common. Previous studies from earlier years have also documented moderate to high prevalence of the pvdhfr S58R + S117N double mutants in Colombia43,68. Similar patterns have been reported in P. falciparum in Colombia, with a 2018 study in Chocó reporting 100% double pfdhfr mutants, and 43% single pfdhps mutants69. Our genomic data also showed evidence of similar trends in P. vivax in neighbouring Brazil and Peru, and no SP resistance variants in Mexico. Other studies have also documented the lack of pvdhfr mutations in Mexico or Nicaragua70. In a separate study from French Guyana, several pvdhfr and pvdhps mutations were present at very high prevalence, but appear not to have spread to other parts of the Americas71. In contrast to the Americas (aside from French Guyana), Thailand and Indonesia exhibited high mutation rates, potentially reflecting differences in drug use between these regions. In addition to the known SP resistance candidates, we identified a pvdhfr T98_N108del that was prevalent (~ 60%) in Colombia but absent in the other populations. The functional impact of the pvdhfr T98_N108del remains unclear but its high prevalence in Colombia justifies further investigation. Further investigation is also required to understand the utility of the antifolates in IPTp for P. vivax amidst different pvdhfr and pvdhps backgrounds.

Chloroquine (CQ) remains the frontline treatment for blood-stage P. vivax infections in Colombia, but no validated markers of clinical efficacy have been identified for this species38. Following evidence of clinical failures, CQ was removed from P. falciparum treatment policy in Colombia in 2008, but the resistance-conferring pfcrt K76T mutation remains prevalent69. In addition to pfcrt, hard selective sweeps postulated to reflect CQ pressure have also been reported at pfaat1 in the Pacific Coast of Colombia10. In contrast to P. falciparum, clinical surveys of CQ efficacy against P. vivax have shown failure rates below 3% in Colombia72. There was no evidence of selection in either of pvcrt-o or pvaat1 in our study. For reference purposes, we documented the frequencies of the pvmdr1 Y976F and F1076L mutations that have been reported to be minor determinants of CQ resistance in P. vivax, finding 0–20% frequency across Colombia. In other studies, in the Americas, the prevalence of pvmdr1 Y976F and F1076L alleles ranged from 0% prevalence in Mexico, 4–13% in Peru, and 62–100% in Nicaragua73,74. For context, the frequencies in Colombia are comparable to Thailand, where ~ 10% infections carried the Y976F mutation, and < 10% CQ failure rate was reported20. In contrast, 100% of the Papua Indonesian infections carried the Y976F mutation; a population where > 60% chloroquine failure was reported by day 28 in the early 2000s22. However, the interpretation of these findings in the context of CQ’s efficacy in Colombia is constrained and will require validated markers.

Using information on orthologous genes involved in drug resistance in P. falciparum, and hypothesis-free methods to detect signals of selection, we identified several candidate markers of resistance and other adaptations. The candidates include non-synonymous variants in orthology-based drug resistance candidates pvmdr2, pvmrp2, and plasmepsin IV noted for substantial inter-population differences in frequency. Using haplotype-based signals of selection, putative adaptations were identified in genes involved in a range of other functions including vitamin B6 synthesis (pyridoxine biosynthesis protein PDX2), intracellular transport (oligomeric Golgi complex subunit 4), immune evasion (6-cysteine proteases P12 and P47, and PIMMS43), and malaria transmission (metacaspase-2)50–52. However, signals of extended haplotype homozygosity can be complex to decipher, and these candidates will require further exploration in functional studies.

As Colombia invests efforts towards malaria elimination, detection of imported cases and other key reservoirs will be critical to avoid resurgence. Imported malaria is a particular challenge for P. vivax, where the dormant liver stages and highly persistent subpatent and asymptomatic infections can promote infection spread and confound the accuracy of travel histories. Our study identified two infections from Nariño, Colombia, that exhibited higher genetic relatedness to infections from Sullana, Peru, than to the local Colombian population, suggestive of cross-border spread. Nariño and Sullana are both located along the Pacific coast but also have borders with the Amazon region, which might provide an infection reservoir to both sites. Our data also shows comparable prevalence between Colombia and Peru at most of the putative resistance-conferring mutations in pvdhfr, pvdhps and pvmdr. However, the evidence for other P. vivax adaptations that differ between Colombia and Peru, highlight the risk of introducing new variants into either population that may undermine local interventions.

Our data demonstrate the potential of molecular approaches to capture new insights on local P. vivax transmission and adaptations within Colombia, as well as cross-border spread. However, obtaining high-quality whole genome sequencing data from P. vivax clinical isolates remains challenging, constraining sample size and the opportunity to investigate high-resolution spatial trends. High-throughput genotyping using approaches such as amplicon-based sequencing of SNP or microhaplotype barcodes offers a more cost-effective approach for P. vivax surveillance at high spatial resolution75,76. At high spatio-temporal density, the data generated from molecular surveillance has great potential to support the NMCP in their surveillance and response strategies to fast-track P. vivax elimination.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who contributed their samples to the study, the health workers and field teams who assisted with the sample collections, and the staff of the Wellcome Sanger Institute Sample Logistics, Sequencing, and Informatics facilities for their contributions. We also thank Alberto Tobon Castaño for helpful guidance on the study. The patient sampling and metadata collection from Colombia were supported by Colciencias Colombia (FP44842-503-445 awarded to DFE). The study was also supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-043618 awarded to SA), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP2001083 awarded to SA), and the Wellcome Trust (200909 and ICRG GR071614MA Senior Fellowships in Clinical Science to RNP). The whole genome sequencing component of the study was supported by the Medical Research Council and UK Department for International Development (award number M006212 to DPK) and the Wellcome Trust (award numbers 206194 and 204911 to DPK).

Author contributions

Z.P., D.F.E., T.M.L., R.N.P. and S.A. conceived and designed the study. E.S., Z.P., E.D.B., R.D.P., H.T. and S.A. conducted data analyses. Z.P., D.F.E., T.M.L., L.M., M.F.Y., A.R., R.N. and D.P.K. provided critical patient, laboratory and informatic resources for the study. S.H. and M.A. contributed previously published, open-access P. vivax genomes. E.S., Z.P. and S.A. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data underlying the genomes of the 64 high-quality Colombian P. vivax samples used in the study have all been deposited into the European Nucleotide Archive, with accession codes detailed in Supplementary Data 1. The P. vivax genotyping data used for the Colombian and global analyses derives from the MalariaGEN Pv4.0 dataset and is accessible as a Variant Calling Format (VCF) file (describing ~ 4.5 million variants in 1,895 worldwide P. vivax genomes) on the MalariaGEN website at https://www.malariagen.net/data/open-dataset-plasmodium-vivax-v4.0.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Edwin Sutanto and Zuleima Pava.

Dominic P. Kwiatkowski is Deceased.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-46076-1.

References

- 1.WHO. World Malaria Report 2022. World Health Organization; Geneva 2022. (2022).

- 2.Colombia Instituto National de Salud Boletín Epidemiológico website. https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Paginas/Vista-Boletin-Epidemilogico.aspx. Accessed 30 June 2023.

- 3.Mesa-Echeverry E, Niebles-Bolivar M, Tobon-Castano A. Chloroquine-primaquine therapeutic efficacy, safety, and plasma levels in patients with uncomplicated plasmodium vivax malaria in a Colombian Pacific Region. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019;100:72–77. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro-Cavadia CJ, Carmona-Fonseca J. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of chloroquine monotherapy for the treatment of acute uncomplicated gestational malaria caused by P. Vivax, Cordoba, Colombia, 2015–2017. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2020;71:21–33. doi: 10.1897/rcog.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Z, Sullivan SA, Carlton JM. The biology of Plasmodium vivax explored through genomics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1342:53–61. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brashear AM, Cui L. Population genomics in neglected malaria parasites. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13:984394. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.984394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benavente ED, et al. Distinctive genetic structure and selection patterns in Plasmodium vivax from South Asia and East Africa. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3160. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hupalo DN, et al. Population genomics studies identify signatures of global dispersal and drug resistance in Plasmodium vivax. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:953–958. doi: 10.1038/ng.3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter DJ, et al. Whole genome sequencing of field isolates reveals extensive genetic diversity in plasmodium vivax from Colombia. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Diseases. 2015;9:e0004252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrasquilla M, et al. Resolving drug selection and migration in an inbred South American Plasmodium falciparum population with identity-by-descent analysis. PLoS Pathogens. 2022;18:e1010993. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor AR, Echeverry DF, Anderson TJC, Neafsey DE, Buckee CO. Identity-by-descent with uncertainty characterises connectivity of Plasmodium falciparum populations on the Colombian-Pacific coast. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1009101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacerda MVG, et al. Single-dose tafenoquine to prevent relapse of plasmodium vivax malaria. New Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:215–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MalariaGen, et al. An open dataset of Plasmodium vivax genome variation in 1,895 worldwide samples. Wellcome open research. 2022;7:136. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17795.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SIVIGILA. El Sistema de Salud Pública (SIVIGILA) (2022).

- 15.Rodriguez JC, Uribe GA, Araujo RM, Narvaez PC, Valencia SH. Epidemiology and control of malaria in Colombia. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(Suppl 1):114–122. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000900015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Padilla JC, Chaparro PE, Molina K, Arevalo-Herrera M, Herrera S. Is there malaria transmission in urban settings in Colombia? Malaria J. 2015;14:453. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0956-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochoa J, Osorio L. Epidemiology of urban malaria in Quibdo, Choco. Biomedica. 2006;26:278–285. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v26i2.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montoya-Lerma J, et al. Malaria vector species in Colombia: A review. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(Suppl 1):223–238. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000900028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez C, et al. Entomological characterization of malaria in northern Colombia through vector and parasite species identification, and analyses of spatial distribution and infection rates. Malaria J. 2017;16:431. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phyo AP, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus chloroquine in the treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria in Thailand: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;53:977–984. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price RN, et al. Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2014;14:982–991. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70855-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ratcliff A, et al. Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;101:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auburn S, et al. A new Plasmodium vivax reference sequence with improved assembly of the subtelomeres reveals an abundance of pir genes. Wellcome Open Res. 2016;1:4. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.9876.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auburn S, et al. Characterization of within-host Plasmodium falciparum diversity using next-generation sequence data. PloS One. 2012;7:e32891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manske M, et al. Analysis of Plasmodium falciparum diversity in natural infections by deep sequencing. Nature. 2012;487:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature11174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villanueva RAM, Chen ZJ. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd edition. Meas.-Interdiscip. Res. 2019;17:160–167. doi: 10.1080/15366367.2019.1565254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu SJ, et al. The origins and relatedness structure of mixed infections vary with local prevalence of P. falciparum malaria. eLife. 2019;8:1. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu SJ, Almagro-Garcia J, McVean G. Deconvolution of multiple infections in Plasmodium falciparum from high throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:9–15. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaffner SF, Taylor AR, Wong W, Wirth DF, Neafsey DE. hmmIBD: Software to infer pairwise identity by descent between haploid genotypes. Malaria J. 2018;17:196. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: Analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cingolani P, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w(1118); iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amos B, et al. VEuPathDB: The eukaryotic pathogen, vector and host bioinformatics resource center. Nucl. Acids Res. 2022;50:D898–D911. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blum M, et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucl. Acids Res. 2021;49:D344–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buyon LE, Elsworth B, Duraisingh MT. The molecular basis of antimalarial drug resistance in Plasmodium vivax. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2021;16:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price RN, Auburn S, Marfurt J, Cheng Q. Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of drug-resistant Plasmodium vivax. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gautier M, Klassmann A, Vitalis R. REHH 2.0: A reimplementation of the R package REHH to detect positive selection from haplotype structure. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017;17:78–90. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auburn S, et al. Genomic analysis of plasmodium vivax in Southern Ethiopia reveals selective pressures in multiple parasite mechanisms. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;220:1738–1749. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suwanarusk R, et al. Chloroquine resistant Plasmodium vivax: in vitro characterisation and association with molecular polymorphisms. PloS one. 2007;2:e1089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawkins VN, et al. Multiple origins of resistance-conferring mutations in Plasmodium vivax dihydrofolate reductase. Malaria J. 2008;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Auburn S, et al. Genomic analysis reveals a common breakpoint in amplifications of the Plasmodium vivax multidrug resistance 1 locus in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Imwong M, et al. Gene amplification of the multidrug resistance 1 gene of Plasmodium vivax isolates from Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2657–2659. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01459-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dijkman PM, et al. Structure of the merozoite surface protein 1 from Plasmodium falciparum. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:1. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibrahim A, et al. Population-based genomic study of Plasmodium vivax malaria in seven Brazilian states and across South America. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023;18:100420. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu B, et al. Expression and regulation of 1-acyl-sn-glycerol- 3-phosphate acyltransferases in the epidermis. J. Lipid. Res. 2005;46:2448–2457. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500258-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nurlinawati VK, Aertsen A, Michiels CW. Role of 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase in psychrotrophy and stress tolerance of Serratia plymuthica RVH1. Res. Microbiol. 2015;166:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumari V, et al. Dissecting The role of Plasmodium metacaspase-2 in malaria gametogenesis and sporogony. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022;11:938–955. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2052357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyons FMT, Gabriela M, Tham WH, Dietrich MH. Plasmodium 6-cysteine proteins: Functional diversity, transmission-blocking antibodies and structural scaffolds. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022;12:945924. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.945924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ukegbu CV, et al. PIMMS43 is required for malaria parasite immune evasion and sporogonic development in the mosquito vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:7363–7373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919709117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Auburn S, Cheng Q, Marfurt J, Price RN. The changing epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax: Insights from conventional and novel surveillance tools. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Auburn S, et al. Genomic analysis of a pre-elimination Malaysian Plasmodium vivax population reveals selective pressures and changing transmission dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2585. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04965-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ford A, et al. Whole genome sequencing of Plasmodium vivax isolates reveals frequent sequence and structural polymorphisms in erythrocyte binding genes. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2020;14:e0008234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pearson RD, et al. Genomic analysis of local variation and recent evolution in Plasmodium vivax. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:959–964. doi: 10.1038/ng.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parobek CM, et al. Selective sweep suggests transcriptional regulation may underlie Plasmodium vivax resilience to malaria control measures in Cambodia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E8096–E8105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608828113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaffner SF, et al. Malaria surveillance reveals parasite relatedness, signatures of selection, and correlates of transmission across Senegal. Medrxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.04.11.23288401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nair S, et al. Single-cell genomics for dissection of complex malaria infections. Genome Res. 2014;24:1028–1038. doi: 10.1101/gr.168286.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Auburn S, Barry AE. Dissecting malaria biology and epidemiology using population genetics and genomics. Int. J. Parasitol. 2017;47:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buyon LE, et al. Population genomics of Plasmodium vivax in Panama to assess the risk of case importation on malaria elimination. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2020;14:e0008962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Echeverry DF, et al. Long term persistence of clonal malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum lineages in the Colombian Pacific region. BMC Genet. 2013;14:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miotto O, et al. Multiple populations of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Cambodia. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:648–655. doi: 10.1038/ng.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Montenegro LM, et al. State of artemisinin and partner drug susceptibility in plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from Colombia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:263–270. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blair S, et al. Therapeutic efficacy test in malaria falciparum in Antioquia, Colombia. Malaria J. 2006;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osorio L, Perez LDP, Gonzalez IJ. Assessment of the efficacy of antimalarial drugs in Tarapaca, in the Colombian Amazon basin. Biomedica. 2007;27:133–140. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v27i1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kayentao K, et al. Intermittent preventive therapy for malaria during pregnancy using 2 vs 3 or more doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and risk of low birth weight in Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309:594–604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saralamba N, et al. Geographic distribution of amino acid mutations in DHFR and DHPS in Plasmodium vivax isolates from Lao PDR, India and Colombia. Malaria J. 2016;15:484. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1543-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guerra AP, et al. Molecular surveillance for anti-malarial drug resistance and genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum after chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine withdrawal in Quibdo, Colombia, 2018. Malaria J. 2022;21:306. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04328-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gonzalez-Ceron L, Rodriguez MH, Montoya A, Santillan-Valenzuela F, Corzo-Gomez JC. Molecular variation of Plasmodium vivax dehydrofolate reductase in Mexico and Nicaragua contrasts with that occurring in South America. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;62:364–371. doi: 10.21149/10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barnadas C, et al. High prevalence and fixation of Plasmodium vivax dhfr/dhps mutations related to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine resistance in French Guiana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;81:19–22. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.81.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Castillo CM, Osorio LE, Palma GI. Assessment of therapeutic response of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine in a Malaria transmission free area in Colombia. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:559–562. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000400020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gonzalez-Ceron L, et al. Genetic diversity and natural selection of Plasmodium vivax multi-drug resistant gene (pvmdr1) in Mesoamerica. Malaria J. 2017;16:261. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1905-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Villena FE, et al. Molecular surveillance of the Plasmodium vivax multidrug resistance 1 gene in Peru between 2006 and 2015. Malaria J. 2020;19:450. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03519-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baniecki ML, et al. Development of a single nucleotide polymorphism barcode to genotype Plasmodium vivax infections. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Siegel, S. V. et al. Lineage-informative microhaplotypes for spatio-temporal surveillance of Plasmodium vivax malaria parasites medRxiv. 10.1101/2023.03.13.23287179 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Battle KE, et al. Mapping the global endemicity and clinical burden of Plasmodium vivax, 2000–17: A spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2019;394:332–343. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31096-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giraldo-Calderon GI, et al. VectorBase.org updates: Bioinformatic resources for invertebrate vectors of human pathogens and related organisms. Curr. Opin. Insect. Sci. 2022;50:1060. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2021.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data underlying the genomes of the 64 high-quality Colombian P. vivax samples used in the study have all been deposited into the European Nucleotide Archive, with accession codes detailed in Supplementary Data 1. The P. vivax genotyping data used for the Colombian and global analyses derives from the MalariaGEN Pv4.0 dataset and is accessible as a Variant Calling Format (VCF) file (describing ~ 4.5 million variants in 1,895 worldwide P. vivax genomes) on the MalariaGEN website at https://www.malariagen.net/data/open-dataset-plasmodium-vivax-v4.0.