Abstract

Senescent cells may have a prominent role in driving inflammation and frailty. The impact of cellular senescence on frailty varies depending on the assessment tool used, as it is influenced by the criteria or items predominantly affected by senescent cells and the varying weights assigned to these items across different health domains. To address this challenge, we undertook a thorough review of all available studies involving gain- or loss-of-function experiments as well as interventions targeting senescent cells, focusing our attention on those studies that examined outcomes based on the individual frailty phenotype criteria or specific items used to calculate two humans (35 and 70 items) and one mouse (31 items) frailty indexes. Based on the calculation of a simple “evidence score,” we found that the burden of senescent cells related to musculoskeletal and cerebral health has the strongest causal link to frailty. We deem that insight into these mechanisms may not only contribute to clarifying the role of cellular senescence in frailty but could additionally provide multiple therapeutic opportunities to help the future development of a desirable personalized therapy in these extremely heterogeneous patients.

Keywords: Aging, Frailty, Cellular senescence, Brain function, Musculoskeletal health

Introduction

Frailty is a complex age-related condition characterized by an increased individual’s vulnerability and an elevated risk of severe health outcomes [1, 2]. Geriatricians are aware that frailty frequently coexists with age-related chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, cancer, stroke, and musculoskeletal disorders, and that frailty can influence the effects of treatments for these conditions, acting as an effect modifier [3–6]. In clinical practice, the management of frail patients is complex mainly because of the inadequate evidence base for interventions to manage the condition [7] and endless debates on frailty assessment instruments [8, 10]. Indeed, there is no global standard assessment instrument for frailty, and hundreds of tools are used and cited in the literature [8]. Moreover, frailty can originate from a specific disease or be the consequence of various and multiple impairments, and even frail individuals identified with the same instrument are highly heterogeneous [11–13]. These problems hinder progress in discovering the biological hallmarks of frailty, which in turn could be helpful in the prevention and diagnosis of frailty and in providing the necessary accuracy for developing appropriate interventions.

Assuming that frailty is a condition of accelerated aging, it is possible to speculate that the same hallmarks indicated for the aging process (e.g., inflammation and altered intercellular communication, stem cell exhaustion, mitochondrial dysfunction, deregulated nutrient sensing, cellular senescence, telomere and genomic instability, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, compromised autophagy, microbiome disturbance, splicing dysregulation, and altered mechanical properties) [14, 15] are key factors of the frailty syndrome. However, the respective weight of these hallmarks in the aging process is still unclear; importantly, since frailty is measured with specific tools, these hallmarks will have different weights in different frailty models.

Indeed, recent studies addressed the research on frailty biomarkers in body fluids focusing on the identification of genes and factors modulated in aging and age-related diseases [16–19]. This approach has provided several panels of frailty biomarkers for future experimental validation in human and animal models. Among these panels, the low-grade chronic inflammation associated with aging (inflammaging) is likely the most studied and convincing factor implicated in the pathophysiology of frailty [20, 21]. Interestingly, in a subset of the population, initiating systemic inflammation during midlife may independently promote future pathophysiological changes underlying frailty [22, 23]. However, the cause and source of inflammaging in these conditions remain elusive. Understanding the processes underlying midlife inflammation, its consequences, and the mechanisms leading to the amplification of these signals could be influential for early therapeutic targeting. The immune system is notoriously the primary modulator of pro- and anti-inflammatory factor levels; however, to date, it is not the only source of these factors. Senescent cells are emerging as an essential source of inflammatory mediators, leading to the recent hypothesis that these cells’ accumulation may drive the biological phenomenon underlining frailty [24]. This is particularly significant as developing a new class of senescent cells targeting drugs, known as senotherapeutics, has paved the way for potential therapies for age-related diseases and frailty [25]. However, since senescent cells arise in response to damage, a lack of information on the sources of this damage could result in poor therapeutic efficacy. The source of this damage may not yet be active or may be a consequence of lifelong metabolic damage. Still, in the opposite case, these therapies may be similar to treating cancer by removing a consequent effect, i.e., the inflammation, without eliminating the tumoral mass.

This manuscript aims to review the current knowledge on the causal connection between cellular senescence and frailty (considering the different assessment tools in humans and preclinical models) while addressing prominent age-related factors and potential therapeutic targets that may contribute to the excessive accumulation of senescent cells in frailty.

Frailty assessment tools in humans and murine models

Frailty assessment in humans

The most widely used frailty assessment tools in humans are based on the adaptation of the physical frailty phenotype (PP) [26] or of the deficit accumulation frailty index (FI) [27], which are well validated in many populations and settings [1]. These two instruments entail profound differences in the conceptualization of the phenotype (physical vs. multidimensional) and how frailty is assessed (categorical vs. quantitative).

The PP is based on five criteria (i.e., shrinkness, weakness, exhaustion, slowness, and inactivity). Individuals are deemed frail if they meet at least three criteria, pre-frail if they fulfill one or two criteria, and not frail if no criteria are met, thus allowing the categorization of subjects into three distinct risk subgroups. Hence, PP is related to physical function and muscular performance, which are considered summary indices of overall body capacity, but leave out several areas affected by frailty, such as the cognitive status and the psychosocial components.

Conversely, the FI can be considered the practical implementation of the idea of “damage accumulation,” and it is calculated as the ratio between the number of deficits detected and the total number of multiple health deficits considered within an extensive list. This way, the FI is typically scored on a scale of 0 to 1, where higher scores indicate greater levels of frailty. The checklist items may be variable, including diseases, physical and cognitive impairments, psychosocial risk factors, and geriatric syndromes [27–30], to construct a picture as complete as possible of the adverse event risk. However, this frailty measure is principally applied in research settings; in contrast, the Clinical Frailty Scale (which considers only a limited number of health-related variables) is commonly used in clinical settings [31].

Frailty assessment in preclinical models

With a view to understanding the biological mechanisms underlying the onset of frailty, the reverse translation of PP and FI from humans to murine models has recently been emphasized [32]. In this regard, Liu and colleagues [33] translated the PP method to mice by emulating the measurement of four of the five original criteria. More recently, the original murine PP was modified to include body weight and an enhanced endurance analysis with a more established test [34, 35]. As in humans, it allows the categorization of mice into robust (none of the criteria), pre-frail (one or two criteria), and frail (three or more criteria). However, this dichotomous classification suffers from high sample size requirements and misclassification problems. Based on the monthly longitudinal non-invasive assessment of frailty in a large cohort of mice, we recently published an alternative scoring method, which we called the physical function score (PFS), proposed as a continuous variable that resumes into a unique function, one of the five criteria included in the PP [36].

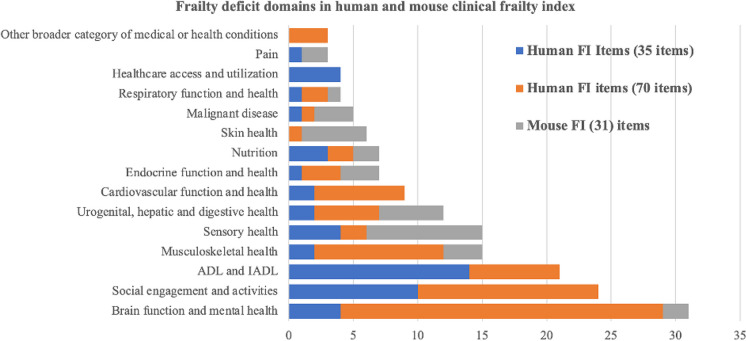

Similarly, Whitehead et al. [37] developed a non-invasive FI for mice based on a checklist of 31 easily observed deficits related to biological systems (integument, musculoskeletal system, auditory system, urogenital system, ocular/nasal system, respiratory system) and signs of discomfort. While the age-related pattern of the mouse FI closely resembles that observed in humans [38], its individual items give high emphasis to skin and sensory health but show inadequate representation of many other items of relevance in the human frailty index (Table 1). This is mainly due to the need to find the best compromise between wide-ranging coverage of frailty items and operational costs in mice [38]. The respective weight (based on the number of items) given to the clinical frailty domains in the human and mouse FI is reported in Fig. 1, considering two highly cited human frailty indexes based on 70 [29] and 35 items [30] as representative examples. Importantly, there are substantial differences in the weight given to different domains in the human and mouse FI, with a partial or complete lack of correspondence for most of them. For instance, while ADL and IADL, social engagement, and cardiovascular deficits are not included in the mouse FI items, they are important components of the human FI.

Table 1.

Items assigned to different frailty domains in the human and mouse clinical frailty index

| Frailty deficit domains | Human FI items (35 items) [30] | Human FI items (71 items) [29] | Mouse FI (31) items [37] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | n | Items | n | Items | n | |

| Cardiovascular function and health |

- Heart disease - Vascular disease |

2 |

- Cardiac problems - Myocardial infarction - Arrhythmia - Congestive heart failure - Cerebrovascular problems - Arterial hypertension - Peripheral pulses - Syncope or blackouts |

7 | - Not included | 0 |

| Endocrine function and health |

- Endocrine or metabolic disorder - Obesity |

1 |

- History of diabetes mellitus - History of thyroid disease - Thyroid problems |

3 |

- Body condition score - Weight - Temperature |

3 |

| Respiratory function and health | - Chronic lung disease | 1 |

- Lung problems - Respiratory problems |

2 | - Breathing problems | 1 |

| Brain function and mental health |

- Neurological disease - CDR -MMSE - Psychiatric disorder |

4 |

- Bradykinesia facial - Bradykinesia of the limbs - History of Parkinson’s disease - Seizures, partial complex - Seizures, generalized - Tremor at rest - Postural tremor - Intention tremor - Changes in general mental functioning - Clouding or delirium - Memory changes - Short-term memory impairment - Long-term memory impairment - Onset of cognitive symptoms - Paranoid features - History relevant to cognitive impairment or loss - Family history relevant to cognitive impairment or loss - Mood problems - Feeling sad, blue, and depressed - History of depressed mood - Depression - Sleep changes - Restlessness - Presence of snout reflex - Presence of palmomental reflex |

25 |

- Vestibular disturbance - Tremor |

2 |

| Urogenital, hepatic and digestive health |

- Renal, urological, or genital disorder - Gastrointestinal or liver disease |

2 |

- Urinary incontinence - Toileting problems - Rectal problems - Abdominal problems - Gastrointestinal problems |

5 |

- Diarrhea - Malocclusion - Rectal prolapse - Distended abdomen - Vaginal/penile prolapse |

5 |

| Musculoskeletal health |

- Osteoarticular disease - SPPB |

2 |

- Musculoskeletal problems - Falls - Poor limb coordination - Poor standing posture - Poor coordination, trunk - Irregular gait pattern - Impaired mobility - Bradykinesia of the limbs - Poor muscle tone in limbs - Poor muscle tone in the neck |

10 |

- Gait disorders - Kyphosis - Forelimb grip strength |

3 |

| Sensory health |

- Otorhinolaryngology or ophthalmology disorder - Visual impairment (near) - Visual impairment (distant) - HHIE (hearing impairment) |

4 |

- Impaired vibration - Head and neck problems |

2 |

- Hearing loss - Vestibular disturbance - Nasal discharge - Cataracts - Corneal opacity - Eye discharge/swelling - Microphthalmia - Vision loss - Menace reflex |

9 |

| Skin health | - Not included | 0 | - Skin problems | 1 |

- Alopecia - Loss of fur color - Dermatitis - Loss of whiskers - Coat condition - Tail stiffening |

5 |

| Malignant disease | - Cancer, malignant blood disease, or HIV | 1 | - Malignant disease | 1 |

- Tumor - Distended abdomen - Anal prolapse |

3 |

| ADL and IADL |

- Help bathing - Help dressing - Help using the toilet - Incontinence - Help eating - Help transferring from bed to chair - Help using telephone - Help shopping - Help with food preparation - Help with housekeeping - Help with laundry - Help with traveling - Help with medication use - Help with finances |

14 |

- Problems with bathing - Problems getting dressed - Impaired mobility - Falls - Toileting problems - Urinary incontinence - Sucking problems |

7 | - Not included | 0 |

| Healthcare access and utilization |

- Regular visit at home from a healthcare professional - Help with medication use - Help with traveling - Help with finances |

4 | - Not included | 0 | - Not included | 0 |

| Social engagement and activities |

- Psychiatric disorder - Help with bathing - Help with dressing - Help with using the toilet - Incontinence - Help with eating - Help with transferring from bed to chair - Help using the telephone - Help with shopping - Help with traveling |

10 |

- Changes in everyday activities - Problems going out alone - Mood problems - Feeling sad, blue, and depressed - Depression - Restlessness - History of depressed mood - Tiredness all the time - Problems getting dressed - Problems carrying out personal grooming - Bulk difficulties - Impaired mobility - Falls - Tiredness all the time |

14 | - Not included | 0 |

| Nutrition |

- MNA - Vitamin D - Obesity |

3 |

- Problems cooking - Sucking problems |

2 |

- Weight - Body condition score |

2 |

| Pain | - Headache | 1 | - Not included | 0 |

- Mouse grimace scale - Piloerection |

2 |

| Other broader category of medical or health conditions | - Not included | 0 |

- Other medical history - Family history of degenerative disease - Breast problems |

3 | - Not included | 0 |

Fig. 1.

Number of items attributed to different frailty domains in the human (70 and 35 items) and mouse (31 items) frailty index

Even if both PP and FI predicted adverse outcomes and death [36, 39, 40], when the two assessment tools were compared in the same population, they did not necessarily identify the same subject as frail [36, 41–43]. This discrepancy is related to the different rationale and design of the two instruments, which should be regarded as complementary rather than contradictory. In fact, in a recent study conducted in a large cohort of geriatric C57BL/6 J mice, we demonstrated that the use of a combined assessment tool, the so-called vitality score (VS), derived from the arithmetic mean of PFS and FI, displays a higher association with mortality compared to using individual assessment tools alone [36].

Cellular senescence in aging and frailty

Cellular senescence involves a complex series of processes that lead to a state of permanent cell cycle arrest, during which cells undergo distinct phenotypic changes. These alterations include profound changes in chromatin structure and cell morphology, an increase in lysosomal activity and levels of tumor suppressors, as well as significant modifications in the secretome [44]. The secretome produced by senescent cells, or senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [45], includes cytokines, chemokines, proteases, and growth factors, which functionally link cell senescence to physiological and pathological processes.

Albeit two major canonical pathways are known to mediate the cell cycle arrest during senescence, the p16/Rb and the p53/p21 pathways, senescent cells and their SASP are extremely heterogenous; they depend on the cellular origin (e.g., fibroblasts and endothelial cells), organism (mouse, humans, others), and temporal steps (early, full, and late senescence) [44, 46] as well as by the cause of the senescent state [47]. Due to this heterogeneity, there is no universal biomarker of cellular senescence. Its characterization is commonly performed through the combination of multiple biomarkers, such as the expression of the tumor suppressor genes p16 and p21, the presence of DNA damage response, and the activity of the senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) [48, 49].

Senescence has a natural physiological role as a protective response to damage. It represents one of the most important mechanisms for suppressing cancer [50] and repairing tissues [51] and may even be valuable for limiting viral infection [52]. Conversely, excessive accumulation of senescent cells has been demonstrated to play a deleterious role in aging and many age-related pathologies [44]. The senescent cells need to persist for a transient lapse of time necessary to drive the correct response by the tissues surrounding the origin of the damage and the immune system. Various cells of the immune system, mainly macrophages, NK cells, and helper T cells, are attracted by the SASP and orchestrate the removal of senescent cells [53].

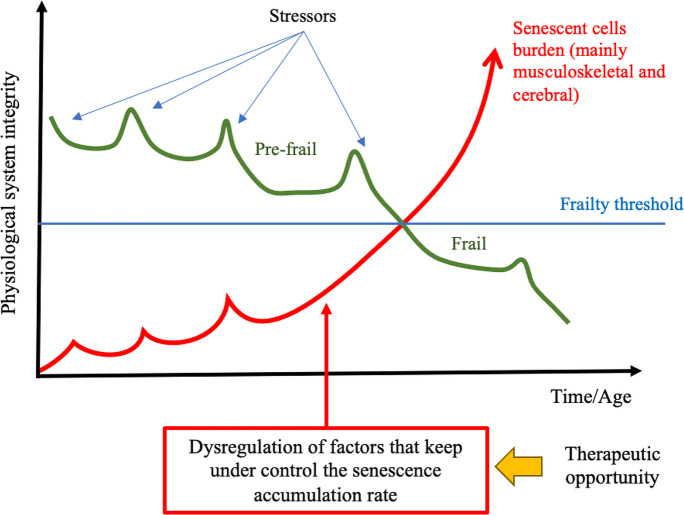

The mechanisms involved in the accumulation of senescent cells in aging are still not completely elucidated; however, it is likely that the increased rate of senescence-inducing damage with the functional decline of the immune system [54] as well as the resistance to apoptosis displayed by some senescent cells [55] play a role in this process. Considering that senescence can spread to neighboring cells through a process known as the “bystander effect” [53, 56, 57], it is likely that once the mechanisms that keep senescence under control are bypassed, the rate of accumulation of senescent cells will become exponential. Soluble bioactive molecules of the SASP as well as miRNAs and other molecules secreted in extracellular vesicles are likely to mediate this process [58–60].

Although cellular senescence is not a primary hallmark of aging [61] [15], senescent cells can represent a source of damage that is able to rapidly propagate resembling a contagious process [62]. Indeed, senescence cells, at least partly through the SASP, can induce secondary senescence even in distant non-senescent cells [63–65]. This consideration may form a strong rationale for supporting cellular senescence among the critical underlining factors behind the increased vulnerability of frail individuals.

Since frailty is measured using various assessment tools, each assigning different weights to items or criteria across different health domains, the impact of cellular senescence will differ depending on the specific assessment tool and the criteria or items primarily affected by the accumulation of senescent cells.

To address this challenge, we undertook a thorough review of all available studies involving gain- or loss-of-function experiments as well as interventions targeting senescent cells, focusing our attention on those studies that examined outcomes based on the individual PP criteria or specific items used to calculate the FI.

Cellular senescence and its causal inference on frailty

Models and intervention to establish causal inference of cellular senescence

A handful of mouse models and interventions are currently available to investigate the causal mechanisms related to cellular senescence in different diseases.

The most common and appropriate models express a reporter gene and a conditional pro-apoptotic factor under key senescent-associated gene promoters, such as the p16-3MR or the INK-ATTAC mice [51, 66], which enable the elimination of senescent cells by administration of ganciclovir (GCV) or AP20187 (AP), respectively. Senescence can also be enhanced through transplantation [63] or modulated through the “classic” depletion or overexpression of genes (i.e., p16 and p21) which induces the core properties of cellular senescence.

Furthermore, a new class of drugs, named senotherapeutics, is emerging as a new possible approach to attenuate the accumulation of senescent cells. Two major senotherapeutic categories can be identified [67]: one that selectively eliminates senescent cells (senolytics) and the other that suppresses markers of senescence or components of the SASP (SASP suppressors) [68, 69]. Although both SASP suppressors and senolytics exhibit off-target effects, senolytics are largely used as complementary tools to provide evidence of causation between the accumulation of senescent cells and age-related pathologies.

Senolytics include a multitude of compounds of different natures, including dasatinib plus quercetin cocktail (D + Q), navitoclax, ABT-737, fisetin, proxofim, geldanamycin, tanespimycin, Foxo4-DRI, panobinostat, azithromycin, roxithromycin, and UBX0101, as well as SA-β-gal-activated prodrugs and nanoparticles.

Hence, both the results obtained in suitable animal models (Tables 2 and 3) and interventions with senolytics (Tables 4 and 5) may contribute to understanding the influence of (specific) senescent cells on the different PP criteria and domains of clinical frailty.

Table 2.

Evidence of a causal relationship between cellular senescence and individual criteria established for PP in mouse models

| Frailty criteria | Model | Method | Results | Role of cellular senescence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrinkness | INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse | AP20187 treatment | Improved body weight, corrected kyphosis, and reduced fat loss | Detrimental | [66] |

| Mouse model of p21 overexpression (p21OE) | p21 induced senescence | Mice display reduced body weight and muscle atrophy | Detrimental | [70] | |

| Young and old (17 months) C57BL/6 mice | Senescent cells transplantation | No effect on body weight in transplanted young mice | No evidence | [63] | |

| Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | No effect on body weight | No evidence | [71] | |

| Weakness | Young and old (17 months) C57BL/6 mice | Senescent cells transplantation | Decreased grip strength in a dose-dependent manner | Detrimental | [63]) |

| Young (3–6 months) and old (> 28 months) p16-3MR mice | GCV or SASP suppressor (CD36 antibody) treatment | Enhanced muscle force generation | Detrimental | [76] | |

| Mouse model of p21 overexpression (p21OE) | p21 induced senescence | Mice exhibit reduced grip strength | Detrimental | [70] | |

| Aged (20 months) p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Moderate beneficial effects on skeletal muscle function only in male mice | Detrimental | [75] | |

| Exhaustion | INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse | AP20187 treatment | Treadmill distance travelled and work significantly increased | Detrimental | [66] |

| Young and old (17 months) C57BL/6 mice | Senescent cell transplantation | Hanging endurance decreased but no effect on treadmill performance | Detrimental | [63] | |

| Mouse model of p21 overexpression (p21OE) | p21 induced senescence | Significant reduction in treadmill performance | Detrimental | [70] | |

| Inactivity | INK-ATTAC aged (18 months) C57BL/6 mice and mixed background | AP20187 treatment | Prevented age-dependent reductions in both spontaneous activity and exploratory behavior | Detrimental | [84] |

| Young and old (17 months) C57BL/6 mice | Senescent cells transplantation | No effect on daily activity | No evidence | [63] | |

| Doxo-treated p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Alleviates impairment in running activity | Detrimental | [85] | |

| Diet obesity-induced p16‐3MR mice | GCV treatment | Did not affect activity | No evidence | [87] | |

| Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | No effect on locomotor activity | No evidence | [71] | |

| Slowness | Young and old (17 months) C57BL/6 mice | Senescent cells transplantation | Impairs walking speed | Detrimental | [63] |

| Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | No effect on the max speed at rotarod test | No evidence | [71] |

Table 3.

Evidence from mouse models of a causal relationship between cellular senescence and different frailty deficit domains*

| Frailty deficit domains | Model | Method | Results | Role of cellular senescence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular health | INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse | AP20187 treatment | Reduced cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area without affecting heart rate, ventricular mass, and many other functional parameters | Detrimental | [66] |

| INK-ATTAC aged (18 months) C57BL/6 mice and mixed background | AP20187 treatment | Improved the adaptive cardiac response to stress | Detrimental | [84] | |

| INK-ATTAC aged (28 months) C57BL/6 mice | AP20187 treatment | Reduces fibrosis and activates resident cardiac progenitors | Detrimental | [92] | |

| INK-ATTAC aged (27 months) C57BL/6 mice | AP20187 treatment | Alleviated myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis | Detrimental | [93] | |

| p16-CreERT2/R26-DTA mice (aged 18 months) | TAM treatment | Induces perivascular heart fibrosis, worsens blood vessel permeability, and increases plasma oxidized LDL | Beneficial | [99] | |

| LDL receptor-deficient p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Regression of atherosclerotic lesions | Detrimental | [95] | |

| Irradiated LDL receptor-deficient p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Reduced plaque necrosis and increased production of key intraplaque-resolving mediators | Detrimental | [96] | |

| Various vascular injury models in p16 overexpressing mice | p16 overexpression | Augmented venous thrombosis | Detrimental | [94] | |

| Myocardial infarction induced in male ICR mice | p16 overexpression and KO by adenovirus delivery | Overexpression of p16 protected, while knockdown of p16 worsened cardiac function | Beneficial | [91] | |

| p16-3MR ApoE − / − mice | GCV treatment | No effect on aortic root plaque size and induces inflammation | Beneficial | [97] | |

| Endocrine and metabolic health | INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse | AP20187 treatment | Prevented loss of adipose tissue | Detrimental | [66] |

| INK-ATTAC aged (18 months) C57BL/6 mice | AP20187 treatment | Prevented age-related lipodystrophy | Detrimental | [84] | |

| Diet-induced obesity in p16‐3MR mice | GCV treatment | Alleviates metabolic and adipose tissue dysfunction | Detrimental | [87] | |

| Diet obesity-induced INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Alleviates metabolic and adipose tissue dysfunction | Detrimental | [87] | |

| Insulin resistance induced (pharmacologically or by high-fat diet) in INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Improved glucose metabolism and β-cell function | Detrimental | [104] | |

| High-fat diet in INK-ATTAC mice (12 months) | AP20187 treatment | Improved β-cell function and increased proliferative capacity in a subset of animals | Detrimental | [105] | |

| Naturally aged mice overexpressing p16 (Super-INK4a/ARF mice | p16 overexpression | Enhanced glucose tolerance and insulin responsiveness | Beneficial | [102] | |

| Beta cell-specific activation of p16INK4a in a transgenic mouse model of diabetes (Pdx1-tTA) | p16 overexpression | Enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and improved glucose homeostasis | Beneficial | [103] | |

| Respiratory health | Induced emphysema in ARF‐DTR mice | DT treatment | Prevents lung dysfunction and emphysema-associated pathologies | Detrimental | [114] |

| Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Improves pulmonary function without effect on the fibrosis | Detrimental | [109] | |

| Pulmonary hypertension model derived from INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Worsen Pulmonary hemodynamic | Beneficial | [115] | |

| Cigarette smoke-induced lung senescence in p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Restore cellular homeostasis and reversed airspace enlargement | Detrimental | [112] | |

| Cigarette smoke-exposed p16 KO mice | p16 KO | Improved lung function | Detrimental | [113] | |

| Brain function and mental health | Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Improved cognitive function | Detrimental | [71] |

| Mouse model (PS19;ATTAC) of tau-mediated neurodegeneration | AP20187 treatment | Prevents hyperphosphorylation of tau and cognitive decline | Detrimental | [117] | |

| Paclitaxel-induced cerebrovascular senescence as cognitive impairment model in p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Improved cognitive performance | Detrimental | [120] | |

| Brain-irradiated p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Improved cognitive performance | Detrimental | [118] | |

| Diet-induced obesity in INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Alleviates neuropsychiatric disorders in obese mice | Detrimental | [119] | |

| Aged (19 months) p16 KO mice | p16 KO | Induced decline in subventricular zone proliferation, neurogenesis, and self-renewal | Detrimental | [121] | |

| Urogenital, hepatic, and digestive health | Chronic renal ischemia induced in INK-ATTAC and C57BL/6 mice | AP20187 treatment | Improved renal function and structure | Detrimental | [127] |

| Accelerated aging (XpdTTD/TTD mice) and naturally aged (27 months) p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Restored renal function | Detrimental | [128] | |

| INK-ATTAC aged [18 months] C57BL/6 mice and mixed background | AP20187 treatment | Prevented age-dependent impairment of kidney function | Detrimental | [84] | |

| p16-CreERT2/R26-DTA mice | TAM treatment | Induces perivascular kidney and liver fibrosis | Beneficial | [99] | |

| Aged (24 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Reduces hepatic steatosis | Detrimental | [86] | |

| Partial hepatectomy in young p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Impairs liver regeneration | Beneficial | [126] | |

| Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) induced liver fibrosis in p16 KO mice | p16 KO | Promote fibrogenesis | Detrimental | [129] | |

| Musculoskeletal health | Aged (20 months) p16-3MR male mice | GCV treatment | Mitigates intervertebral disc degeneration | Detrimental | [137] |

| Adult (12 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment until natural death | Reduced age-related cartilage degeneration | Detrimental | [138] | |

| Osteoarthritis model by anterior cruciate ligament transection in p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis | Detrimental | [138] | |

| INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse | AP20187 treatment | Correction of kyphosis | Detrimental | [66] | |

| Aged (21 months) INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | Improved bone mass and strength as well as bone microarchitecture | Detrimental | [139] | |

| Aged (20 months) DMP1-Cre ± p16-LOX-ATTAC mice (model for specific elimination of senescent osteocytes) | AP20187 treatment | Prevented age-related bone loss at the spine, but not the femur, without affecting osteoclasts or marrow adipocytes | Detrimental | [65] | |

| Aged (20 months) β-actin–Cre ± p16-LOX-ATTAC | AP20187 treatment | Prevented bone loss at the spine and femur, bone formation, and reduced osteoclast and marrow adipocyte numbers | Detrimental | [65] | |

| C57BL/6 young mice | Murine senescent fibroblast transplantation | Caused bone loss | Detrimental | (65) | |

| Radiation-induced osteoporosis in p21-ATTAC and INK-ATTAC | AP20187 treatment | Prevented radiation-induced osteoporosis and increased marrow adiposity only in p21-ATTAC | Detrimental | [140] | |

| Aged (23 months) p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | No effect on the age-related loss of bone mass | No evidence | [193] | |

| Estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis in p16 KO mice | p16 KO | Promote bone formation and prevent osteoporosis | Detrimental | [141] | |

| Model of fracture healing in p16 KO mice | p16 KO | Accelerate fracture healing | Detrimental | [142] | |

| Mouse tail suspension (TS)-induced intervertebral disc degeneration in p16 KO mice | p16 KO | Attenuates intervertebral disc degeneration | Detrimental | [143] | |

| Various murine models (see “Weakness,” “Exhaustion,” and “Slowness” criteria in Table 2) | Various treatments | Senescent cells negatively affect strength, endurance, and walking speed | Mostly (8 studies) detrimental | See Table 2 for ref | |

| Sensory health | INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse (3 weeks of age) | Preventive AP20187 treatment | Delayed onset of cataracts | Detrimental | (66) |

| INK-ATTAC BubR1 progeroid mouse (aged 5 months) | AP20187 treatment | No effect on cataracts | No evidence | [66] | |

| INK-ATTAC aged (18 months) C57BL/6 mice | AP20187 treatment | Eye alterations occurred slowly | Detrimental | [84] | |

| INK-ATTAC aged (18 months) mixed background mice | AP20187 treatment | No effect on cataracts | No evidence | [84] | |

| Elevated intraocular pressure (glaucoma model) in adult p16-3MR or C57BL/6 mice | GCV treatment | Showed vision rescue and neuroprotective effect on retinal ganglion cells | Detrimental | [146] | |

| Skin health | Accelerated aging (XpdTTD/TTD mice) and naturally aged (27 months) p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Improved fur density | Detrimental | [128] |

| Wound healing model in p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Delayed wound healing | Beneficial | [51] | |

| Malignant diseases | C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) | Senescent inducible lymphoma cell transplantation | Promote tumor growth | Detrimental | [154] |

| Nude (nu/nu) mice (5 weeks old) | Human senescent fibroblast transplantation | Stimulate premalignant and malignant proliferation and promote tumors | Detrimental | [153] | |

| Athymic nude mice | Subcutaneous transplant of melanoma cells (previously exposed to senescent secretome) | Promotes metastatic properties in vivo | Detrimental | [155] | |

| p16-3MR mice transplanted with breast cancer cells and treated with doxorubicin | GCV treatment | Reduced cancer relapse after chemotherapy | Detrimental | [85] | |

| T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia injected in INK-ATTAC mice pre-treated with doxorubicin | Pre-treatment with AP20187 | Accelerates the development of leukemia | Beneficial | [163] | |

| Squamous cell skin carcinoma induced in p16-3MR mice treated with doxorubicin | Pre-treatment with GCV | Prevented malignant tumor development | Detrimental | [156] | |

| Naturally aged mice overexpressing p16 (Super-INK4a/ARF mice | p16 overexpression | Manifest higher resistance to and have normal aging and lifespan | Beneficial | [151] | |

| Mouse model of p16 chronic overexpression in basal keratinocytes of the epidermis | p16 overexpression | Induces hyperplasia and dysplasia | Detrimental | [152] | |

| ADL and IADL | - | - | - | - | - |

| Healthcare access and utilization | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social engagement and activities | Various murine models (see “Inactivity” criteria in Table 2) | Various treatments | Senescent cells negatively affect daily activity | Detrimental (2 studies out of 4) | See Table 2 for ref |

| Nutrition | Various murine models (See “Shrinkness” criteria in Table 2) | Various treatments | Senescent cells negatively affect age-related shrinkness | Detrimental (2 studies out of 3) | See Table 2 for ref |

| Diet obesity-induced INK-ATTAC mice | AP20187 treatment | No effect on body weight and composition | No evidence | [119] | |

| Diet obesity-induced p16‐3MR mice | GCV treatment | Did not affect weight or food intake | No evidence | [87] | |

| Pain | Cisplatin-induced neuropathy in p16-3MR mice | GCV treatment | Improved mechanical and thermal sensitivity | Detrimental | [167] |

| Other broader category of medical or health conditions | - | - | - | - | - |

*Includes only experimental studies addressed to a causal relationship with senescent cells “in vivo”

Table 4.

Evidence of a causal-relationship between cellular senescence and individual criteria established for PP from intervention studies with senolytics

| Frailty criteria | Model | Senolytic | Results | Role of cellular senescence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrinkness | Aged (17 months) and young/adult C57BL/6 J mice | D + Q | No effect on body mass | No evidence | [73] |

| SAMP10 mice (9 month) | D + Q | No effect on body weight | No evidence | [74] | |

| Irradiated C57BL/6 mice | D + Q or navitoclax (starting early or late after irradiation) | Improved body condition and body weight loss over 1 year of follow-up | Detrimental | [72] | |

| Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | No effect on body weight | No evidence | [71] | |

| Old (20 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | No effect on body weight | Detrimental | [63] | |

| Weakness | Aged (20 months) C57BL/6 J mice | D + Q | Improve grip strength in mice | Detrimental | [77] |

| C57BL/6 mice beginning at 6 months | D + Q | Improve strength in mice after 5/6 months of treatment | Detrimental | [78] | |

| Young (3–6 months) and old (> 28 months) p16-3MR mice | D + Q | Enhanced muscle force generation | Detrimental | [76] | |

| Aged (20 months) and young/adult C57BL/6 J mice | D + Q | Grip strength was not improved | No evidence | [73] | |

| Human patients with Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | D + Q | Grip strength was not improved | No evidence | [80] | |

| Aged (20-month-old) C57BL/6 mice | SA-β-gal activable gemcitabine (SSK1) | Enhanced grip strength | Detrimental | [79] | |

| SAMP10 mice (9 month) | D + Q | Improved grip strength | Detrimental | [74] | |

| Old (20 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved grip strength | Detrimental | [63] | |

| Exhaustion | Aged (17-month) and young/adult C57BL/6 J mice | D + Q | Average time spent in rotarod increased in old mice (but not in young mice) | Detrimental | [73] |

| Aged (21 months) and irradiated C57BL/6 J mice | Photosensitive senolysis activated by SA-β-gal | Improved hanging endurance | Detrimental | [82] | |

| Leg-irradiated C57BL/6 male mice | D + Q | Alleviates impairment in treadmill exercise endurance | Detrimental | [83] | |

| Aged (20-month-old) C57BL/6 mice | SA-β-gal activable gemcitabine (SSK1) | Enhanced treadmill distance and rotarod time | Detrimental | [79] | |

| Old (20 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved hanging endurance | Detrimental | [63] | |

| Inactivity | Irradiated C57BL/6 young mice | Cycloastragenol | Alleviates impairment in locomotor activity and behavioral responses | Detrimental | [88] |

| Old (20 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved daily activity | Detrimental | [63] | |

| Aged (20-month-old) C57BL/6 mice | SA-β-gal activable gemcitabine (SSK1) | Enhanced rearing frequency | Detrimental | [79] | |

| SAMP10 mice (9 month) | D + Q | Improved total distance on locomotor activity | Detrimental | [74] | |

| Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | No effect on locomotor activity | No evidence | [71] | |

| Slowness | Old (20 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved walking speed | Detrimental | [63] |

| Human patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | D + Q | Improved 6-min walk distance and 4-m gait speed | Detrimental | [80] | |

| Aged (24-month-old) C57BL/6 mice | Navitoclax | No effect on swimming speed | No evidence | [89] | |

| SAMP10 mice (9 months) | D + Q | No significant effect on average speed | No evidence | [74] | |

| Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | No effect on max speed at rotarod after normalization for baseline | No evidence | [71] |

Table 5.

Evidence of a causal relationship between cellular senescence and different frailty deficit domains from intervention studies with senolytics

| Frailty deficit domains | Model | Senolytic | Results | Role of cellular senescence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular health | Aged (28 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Reduces fibrosis, activates resident cardiac progenitors, and increases proliferating cardiomyocytes | Detrimental | [92] |

| Aged (24-month-old) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved ventricular ejection fraction, shortening, and end‐systolic cardiac dimensions without effect on contractile response and cardiac mass | Detrimental | [83] | |

| Aged (23 months) C57BL/6 mice | Navitoclax | Reduced telomere‐associated foci-positive cardiomyocytes and alleviated myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis | Detrimental | [93] | |

| Myocardial infarction in young C57BL/6 mouse | Navitoclax pre-infarction | Attenuates profibrotic protein expression and improves myocardial remodeling, diastolic function, and survival | Detrimental | [98] | |

| Aged (24 months) C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Reduced aortic calcification and improved vasomotor function | Detrimental | [100] | |

| Aged (20 months) C57BL/6N mice | D + Q | Reduces detrimental effects of extracellular vesicles from old mice on endothelial cells | Detrimental | [101] | |

| p16-3MR ApoE − / − mice | Navitoclax | Reduced atherosclerosis lesion by senolysis-independent activity | No evidence | [97] | |

| Endocrine and metabolic health | Diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity | Detrimental | [87] |

| Aged (22 months) C57BL/6 mice | FOXO4-DRI | Alleviated age-related testosterone secretion insufficiency | Detrimental | [108] | |

| Insulin resistance induced (pharmacologically or by high-fat diet) in INK-ATTAC mice | Navitoclax | Improved glucose metabolism and β-cell function | Detrimental | [104] | |

| Aged (21 months) male C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved fasting blood glucose and glucose tolerance | Detrimental | [106] | |

| Retrospective study on dasatinib prescription in type 2 diabetes | D | Lowers serum glucose comparable to first-line diabetic medications | Detrimental | [107] | |

| Respiratory health | Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | Improves pulmonary function without affecting lung fibrosis | Detrimental | [109] |

| Irradiated C57BL/6 mice | D + Q or navitoclax | Improved breathing rate | Detrimental | [72] | |

| Human patients with Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | D + Q | No effect on pulmonary function | No evidence | [80] | |

| Pulmonary hypertension model derived from INK-ATTAC mice | Navitoclax or FOXO4-DRI | Worsen pulmonary hemodynamic | Beneficial | [115] | |

| Bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis in C57BL/6 male mice | Galacto-encapsulated doxorubicin | Improve pulmonary function | Detrimental | [110] | |

| Lung fibrosis induced by intratracheal administration of senescent human cells (IMR90) in mice | Digoxin | Reduced fibrosis | Detrimental | [111] | |

| Aged (21 months) C57BL/6:FVB | Fisetin | No effect on composite lesion score in the lung | No evidence | [116] | |

| Brain function and mental health | Aged (27 months) INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | Improved cognitive function | Detrimental | [71] |

| Mouse model (PS19;ATTAC) of tau-mediated neurodegeneration with inducible clearance of p16 + cells | Early with navitoclax | Prevents hyperphosphorylation of tau and cognitive decline | Detrimental | [117] | |

| Mouse model of Alzheimer (20 months old, tauNFT‐Mapt0/0) | D + Q | Reduction in total neurofibrillary tangles density, neuron loss, and ventricular enlargement | Detrimental | [124] | |

| SAMP10 mouse model of brain aging | D + Q | Improved working memory and exploratory behavior | Detrimental | [74] | |

| The motor neuron disease mouse model hSOD1-G93A | Navitoclax | Did not alter the disease progression | No evidence | [123] | |

| Young (3 months old) and aged (22 months old) rats | D + Q | Improvements in cognitive abilities observed in aged rats | Detrimental | [122] | |

| Brain-irradiated p16-3MR mice | Navitoclax | Improved cognitive performance | Detrimental | [118] | |

| Diet obesity-induced INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | Alleviates neuropsychiatric dysfunction in obese mice | Detrimental | [119] | |

| Aged (21 months) C57BL/6:FVB | Fisetin | Reduced composite lesion score in the brain | Detrimental | [116] | |

| Pilot study in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease patients | D + Q | No changes in cognitive and neuroimaging endpoints as well as in depression and neuropsychiatric outcomes | No evidence | [125] | |

| Urogenital, hepatic, and digestive health | Chronic renal ischemia induced in INK-ATTAC and C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Improved renal function and structure | Detrimental | [127] |

| Diet obesity-induced C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Reduces proteinuria | Detrimental | [87] | |

| Accelerated aging (XpdTTD/TTD mice) and naturally aged (27 months) p16-3MR mice | FOXO4-DRI | Restored renal function | Detrimental | [128] | |

| Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury and multiple-cisplatin-treatment in male C57BL/6 mice | D + Q | Ameliorate renal fibrosis | Detrimental | [130] | |

| Patients with diabetic kidney disease | D + Q | Preliminary evidence of decreased senescent cells in adipose tissue, tissue macrophage infiltration, crown-like structures, and circulating SASP factors | Detrimental | [131] | |

| Aged (21 months) and irradiated C57BL/6 J mice | Photosensitive senolysis activated by SA-β-gal | Attenuated age-related loss of renal function | Detrimental | [82] | |

| Aged (18 months) Prf1 − / − mice (model of accelerated aging) | ABT-737 | Reduce liver and kidney fibrosis | Detrimental | [54] | |

| Partial hepatectomy model in adult C57BL/6 J | ABT-737 | Improves liver regeneration | Detrimental | [134] | |

| Aged (24 months) INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | Reduces hepatic steatosis | Detrimental | [86] | |

| CCL4- or diet-induced liver fibrosis | Senolytic CAR T cells | Restore tissue homeostasis | Detrimental | [135] | |

| Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase null mice (Sod1KO) aged 6 months | D + Q | No effect on various markers of liver fibrosis | No evidence | [132] | |

| Partial hepatectomy in young p16-3MR mice | Navitoclax | Impairs liver regeneration | Beneficial | [126] | |

| Mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (chemical and high-fat diet-induced) | D + Q | Worsened liver disease progression | Beneficial | [133] | |

| Aged (21 months) and irradiated C57BL/6 J mice | Photosensitive senolysis activated by SA-β-gal | Attenuated age-related loss of liver function | Detrimental | [82] | |

| Aged (21 months) C57BL/6:FVB | Fisetin | Reduced composite lesion score in the kidney but not in the liver | Detrimental | [116] | |

| Aged (18 months) female BALB/c mice | D + Q | Reduces intestinal inflammation related to changes in specific microbiota signatures | Detrimental | [136] | |

| Musculoskeletal health | Osteoarthritis model by anterior cruciate ligament transection in p16-3MR mice | intra-articular with UBX0101 | Attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis | Detrimental | [138] |

| Aged (20 months) C57BL/6N mice | D + Q | Improved bone mass and microarchitecture | Detrimental | [139] | |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, study (Phase 2) in knee osteoarthritis patients | intra-articular with UBX0101 | No effect on knee pain and function | No evidence | [145] | |

| Zmpste24 − / − progeria mouse model | Fisetin | Reduced bone density loss | Detrimental | [144] | |

| Zmpste24 − / − progeria mouse model | D + Q | Did not mitigate trabecular bone loss | No evidence | [144] | |

| Human patients with Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | D + Q | Improved SPPB score | Detrimental | [80] | |

| Human patients with Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | D + Q | Grip strength was not improved | No evidence | [80] | |

| Various murine models (see “Weakness,” “Exhaustion,” and “Slowness” criteria in Table 4) | Various senolytics | Senescent cells negatively affect strength, endurance, and walking speed | Detrimental (13 studies out of 18) | See Table 4 for ref | |

| Sensory health | SAMP10 mice (9 months) | D + Q | Significant reduction of frailty index with particular improvements in eye discharge, vision loss, and microphthalmia | Detrimental | [74] |

| Retrospective cohort study examining medical record data for adult patients with glaucoma | History of senolytic drug exposure | No significant changes on progression of glaucomatous visual field | No effect | [147] | |

| Elevated intraocular pressure (glaucoma model) in adult p16-3MR or C57BL/6 mice | Dasatinib early | Showed vision rescue and neuroprotective effect on retinal ganglion cells | Detrimental | [146] | |

| Skin health | Accelerated aging (XpdTTD/TTD mice) and naturally aged (27 months) p16-3MR mice | FOXO4-DRI | Improved fur density | Detrimental | [128] |

| Female aged (18 months) albino hairless mice (Skh-1) | Navitoclax or ABT-737 intradermal | Ameliorate the aging skin phenotype (collagen deposition and epidermal proliferation) | Detrimental | [148] | |

| Aged (18 months) Prf1 − / − mice (model of accelerated aging) | ABT-737 | Reduce skin fibrosis | Detrimental | [54] | |

| Nude mice transplanted with skin grafts from aged humans | Glutaminase inhibitor (BPTES) | Increased collagen density and cell proliferation in the dermis | Detrimental | [149] | |

| Aged (20 months) male Bl6 mice | Anti-apolipoprotein D PDB-conjugate antibody | Improved the senescent skin phenotype | Detrimental | [150] | |

| Malignant diseases | C57BL/6 mice transplanted with senescence inducible lymphoma cells | Bafilomycin A1 | Extended the survival of mice bearing therapy-induced senescent tumors | Detrimental | [157] |

| Breast cancer cells xenograft induced to senescence by irradiation in ovariectomized female NCR NUNU mice | ABT-737 | Inhibited tumor growth | Detrimental | [158] | |

| Adenocarcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer cell xenograft induced to senescence by etoposide or doxorubicin in immunodeficient NSG mice | Navitoclax | Decreased tumor volume and prolonged tumor maintenance | Detrimental | [159] | |

| Ovarian and breast cancer cell xenograft induced to senescence by olaparib in immunodeficient NSG mice | Navitoclax | Decreased tumor size | Detrimental | [160] | |

| Adenocarcinoma cell xenograft induced to senescence by cisplatin in immunodeficient SCID mice | Navitoclax or galacto-conjugated navitoclax (Nav-Gal) | Inhibited tumor growth | Detrimental | [161] | |

| Xenografts of SK‐MEL‐103 melanoma cells induced to senescence by palbociclib in athymic female nude mice | Galacto-encapsulated doxorubicin | Inhibited tumor growth | Detrimental | [110] | |

| Obesity-induced hepatocellular carcinoma mouse model and | BET family protein degrader (ARV825) | Reduced liver cancer development | Detrimental | [162] | |

| Xenograft of colon cancer cells induced to senescence by doxorubicin in nude mice | BET family protein degrader (ARV825) | Reduced tumor size | Detrimental | [162] | |

| Lung cancer or breast cancer xenografts induced to senescence by gemcitabine or doxorubicin in immunodeficient nude NMRI nu/nu mice | Digoxin | Reduced tumor volume | Detrimental | [111] | |

| Mice harboring orthotopic lung adenocarcinomas induced to senescence by MEK and CDK4/6 inhibitors | Senolytic CAR T cells | Prolonged survival | Detrimental | [135] | |

| Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase null mice (Sod1KO) aged 6 months | D + Q | Reduced the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma | Detrimental | [132] | |

| Xenograft studies conducted with hepatic carcinoma cells induced or not to senescence with doxorubicin in athymic nude mice | D + Q | Ineffective in cleaning senescent cells and induced acute pro-tumorigenic effects in control mice | Beneficial | [164] | |

| T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia injected in doxorubicin pre-treated C57BL/6 mice | Navitoclax | Accelerates the development of leukemia | Beneficial | [163] | |

| Mouse model of p16 chronic overexpression in basal keratinocytes of the epidermis | ABT-737 | Partial reversal of hyperplasia induced by p16 overexpression | Detrimental | [152] | |

| ADL and IADL | Pilot study in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease patients | D + Q | No changes in informant-reported Lawton IADL | No evidence | [125] |

| Healthcare access and utilization | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social engagement and activities | Various murine models (see “Inactivity” criteria in Table 4) | Various senolytics | Senescent cells negatively affect daily activity | Detrimental (4 studies) | See Table 4 for ref |

| Nutrition | Various murine models (See “Shrinkness” criteria in Table 4) | Various senolytics | Senescent cells negatively affect age-related shrinking | Detrimental (2 study out of 4) | See Table 4 for ref |

| Dietary induced obesity in INK-ATTAC mice | D + Q | No effect on body weight and composition | No evidence | [119] | |

| Obese mouse model (ob/ob female mice) | D + Q | No effect on body weight and composition | No evidence | [166] | |

| Pain | Irradiated C57BL/6 mice | D + Q or navitoclax (starting early or late after irradiation) | Improved mouse grimace scale | Detrimental | [72] |

| SAMP10 mice (9 month) | D + Q | Improved mouse grimace scale | Detrimental | [74] | |

| Other broader category of medical or health conditions | Aged (19 months) mice infected with a sublethal dose of H1N1 and H3N2 influenza virus | D + Q | Did not improve overall influenza responses | No evidence | [194] |

| SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters and mice | D + Q or navitoclax | Mitigated lung disease | Detrimental | [168] | |

| COVID-19 murine model K18-hACE2 | D + Q | Reduced mortality and other clinical symptoms | Detrimental | [169] | |

| Young and old (20 months) SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters | Navitoclax | Ameliorated lung disease in aged animals | Detrimental | [170] |

Causal links between cellular senescence and physical frailty criteria

Available studies that investigated the causal relationship between cellular senescence and specific PP criteria using suitable murine models or senolytic interventions are reported in Tables 2 and 4, respectively.

Shrinkness

The first evidence that the clearance of p16INK4a-positive senescent cells antagonizes several processes associated with physical frailty was provided in a mouse model of accelerated aging (BubR1H/H) carrying the INK-ATTAC transgene [66]. Treatment with AP20187 in these mice improved body weight, corrected kyphosis, and reduced fat loss, thus demonstrating a detrimental effect of senescent cells on age-related shrinkage. These results are confirmed by the phenotype of the mouse model of p21 overexpression (p21OE mice), which displays an accelerated weight loss phenotype [70].

However, another study in normally aged INK-ATTAC mice [71] as well as the transplantation of senescent cells in young and old mice [63] did not report similar effects after a relatively short-term (1–2 months) follow-up.

Similarly, senolytic (D + Q or navitoclax) interventions showed a positive effect on body weight loss after one year of follow-up in irradiated C57BL/6 mice [72] but did not affect the body weight of normally [63, 71, 73] or accelerated aging mice [74] after a relatively shorter time of follow-up (approximately 4 months).

Hence, age-related shrinkage appears to be a long-lasting effect of accumulating senescent cells, which may be rarely observed in model or intervention studies with a relatively short follow-up.

Weakness

Removal of senescent cells in aged p16-3MR mice [75, 76], as well as senescent cell transplantation [63] and p21 overexpression [70] models, support a causal relationship between accumulating senescent cells and weakness. Interventions performed with D + Q in normally or accelerated aging mice, quite uniformly, reinforce this hypothesis [63, 74, 76–78]. A detrimental role of senescent cells on muscle weakness was also demonstrated using a completely different senolytic (SA-β-gal activable gemcitabine) [79]. A lack of significant effect of D + Q on grip strength was reported in one study in aged mice [73], as well as in a human pilot clinical trial [80]. Notably, both of these studies reported positive effects on other areas related to physical function performance. Remarkably, muscle weakness appears to be only partially related to the senescence of muscle satellite cells as these are extremely rare in mice aged below 27 months [81]. The presence of senescent cells in other tissues, such as adipose tissue, and circulating SASP factors are likely to be directly involved in this relationship.

Exhaustion

Only a few studies have investigated endurance performances in animals with manipulated levels of cellular senescence. Overexpression of p21, but not senescent cell transplantation [63], significantly reduces the endurance performance measured by the treadmill test [70]. However, the transplantation model affected hanging performances, another parameter related to exhaustion. As expected, the genetic removal of senescent cells from a model of accelerated aging improved treadmill distance and work [66].

In agreement, all senolytic treatments tested so far in aged and irradiated mice have been effective in ameliorating endurance performance [63, 73, 79, 82, 83].

It is likely that the burden of accumulating senescent cells may affect endurance performance through systemic inflammatory mediators secreted in the SASP.

Inactivity

Not only physical but also cognitive and psychological conditions contribute to physical inactivity. Senescent cells have the potential to affect all these components, and certain experimental models have indeed confirmed this relationship in aged [84] and chemotherapy-treated mice [85]. Consistent with the findings observed for the shrinkness criteria, experiments with a relatively lower follow-up (period 1–2 months) after modulating the senescent cell burden did not report significant improvement in the daily or locomotor activity of different mouse models [63, 86, 87]. Excluding one study with D + Q [86], an improvement in the activity has also been reported with at least three different senolytic interventions in normally [63, 79] and accelerated aging, as well as in irradiated mice [88]. Overall, it seems that senolytic interventions display greater efficacy in improving the activity of aged mice rather than transgenic or transplantation models. Whether the efficacy of these interventions is related only to the removal of senescent cells or to additional off-targets that can benefit the physical, cognitive, and psychological conditions of the mice is still unknown.

Slowness

At this moment, the major evidence that senescent cells casually contribute to physical frailty has been obtained after the transplantation of senescent cells in young and old mice [63]. Transplanting a few senescent cells (adipose-derived mesenchymal cells induced by ionizing radiation) by i.p. injection caused persistent physical dysfunction, including impaired walking speed, and a frailty-like phenotype with reduced survival in young and older recipients. However, senescent cell removal in aged INK-ATTAC mice did not affect the max speed of running recorded by a rotarod test [71]. Paradoxically, only one intervention [63] with senolytics (out of 4 retrieved from literature) reported an improvement of parameters related to the slowness criteria in normally and accelerated aging mice [71, 74, 89], whereas a pilot clinical trial with D + Q in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis reported an improvement in 6-min walk distance and 4-m gait speed [80]. This could be related to the challenge of getting a reliable recording of speed in mice considering the confounding impact of gender, walking style, gait, and neurodegenerative patterns [90].

Overall, these findings confirm that senescent cells can negatively affect the criteria of the PP related to muscle strength, endurance, and activity, while less involvement is recorded for the criteria related to speed and body condition.

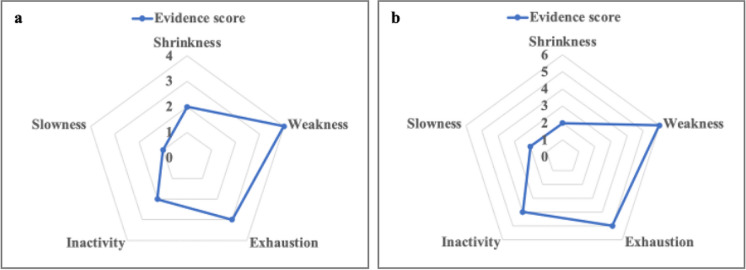

A schematic representation of the overall evidence of a causal impact of cellular senescence on each PP criteria can be visualized (Fig. 2) by calculating a simple score: Evidence score = no. of studies supporting a detrimental role of senescence – no. of studies supporting a beneficial role of senescence. Interestingly, the evidence score build based on the results of studies in animal models (suitable for modulation of cellular senescence) (Fig. 2a and Table 2) overlaps quite completely with the one build based on the results of senolytic interventions (Fig. 2b and Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Current evidence of a causal relationship between cellular senescence and physical frailty phenotype criteria. The evidence scores are computed as no. of studies supporting a detrimental role of senescence − no. of studies supporting a beneficial role of senescence. a Evidence score computed on the basis of the results of the studies on animal models reported in Table 2. b Evidence score computed on the basis of the results of the studies with senolytic interventions reported in Table 4

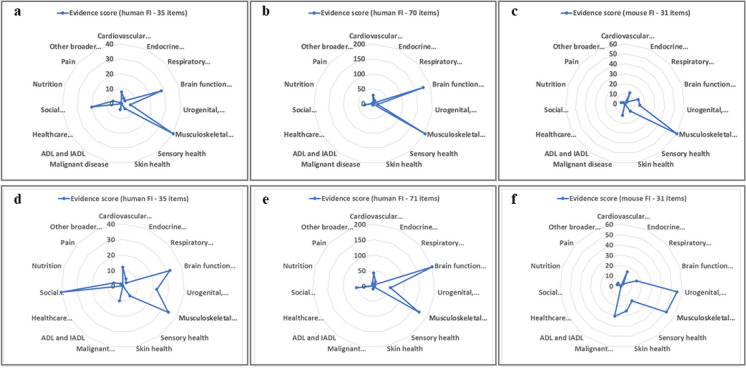

Causal links between cellular senescence and clinical frailty index domains

In both humans and mice, the clinical FI usually comprises more than 30 items involving domains related to comorbidities, symptoms, diseases, disabilities, and other health deficits. Therefore, it is not surprising that a huge number of studies have used outcomes related to these domains after modulating senescent cells in suitable animal models (Table 3) or after interventions with senolytics (Table 5).

Cardiovascular health

A wide range of cardiovascular factors contribute to the clinical frailty index in humans, but they have not been included in the mouse FI. However, cardiovascular aspects are one of the major focus of preclinical research around cellular senescence.

While an increased expression of p16 seems to play an important role in cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction [91], the removal of senescent cells in normally aging INK-ATTAC mice [84, 92, 93], and to a lesser extent in a model of accelerated aging [66], leads to improvements in cardiac function. This may be consistent with the negative role of excessively accumulating senescent cells.

However, results related to vascular health in animal models are highly controversial. Overexpression of p16 is detrimental in multiple vascular injury models [94], and some studies in models of atherosclerosis derived from p16-3MR mice found that the removal of senescent cells favors the regression of atherosclerotic lesions [95, 96]. However, these results were not recently replicated in a very similar model, where GCV treatment was ineffective in reducing plaque size and induced inflammation [97]. In the same study, macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells were shown to express p16, p21, and β-galactosidase activity without being senescent. Most importantly, navitoclax was shown to reduce atherosclerosis lesions by removing leukocytes and platelets rather than through senolysis, providing an alternative explanation to the previous beneficial effects observed in a myocardial infarction model [98]. Similar findings were obtained in the p16-CreERT2/R26-DTA mouse model, where senescent cells can be removed by administration of tamoxifen (TAM) [99]. TAM treatment in aged mice worsened blood-vessel permeability and induced perivascular fibrosis in the heart, liver, and kidney. These results suggest that some p16-positive cells (senescent or non-senescent) are structurally and functionally important and may have a specific beneficial effect related to the cardiovascular domain of the FI.

Hence, it might not be excluded that the beneficial effects of D + Q treatment on the cardiovascular function of aged mice [83, 92, 100, 101] could be related to off-target effects independent of senolysis.

Endocrine and metabolic health

An enhanced glucose tolerance and insulin responsiveness have been observed in systemic and pancreatic-specific models of p16 overexpression [102, 103], suggesting a beneficial role of senescent cells in metabolic function related to type 2 diabetes. Conversely, an improvement in metabolic (glucose homeostasis), endocrine (β-cell function), and adipose tissue function has been reported after the removal of senescent cells in all INK-ATTAC or p16-3MR models currently tested, including normal and accelerated aging as well as diet-induced obesity or insulin resistance [66, 84, 87, 104, 105]. This apparent discrepancy could be eventually explained by the beneficial role of p16-positive cells and the detrimental role of an excess of senescent cells.

Treatments with D + Q or navitoclax also support the detrimental effect of accumulating senescent cells on endocrine and metabolic deficits related to glucose homeostasis [87, 104, 106]. These results are further supported by a retrospective investigation on dasatinib prescription in patients with type 2 diabetes, which revealed a reduction in blood glucose levels comparable to first-line diabetic medications [107].

Further evidence of the detrimental impact of senescent cells on various endocrine functions comes from a study where treatment with FOXO4-DRI corrected the age-related decline in testosterone secretion in aged mice [108].

Respiratory health

The role of senescent cells on respiratory health seems to follow the same trend observed for cardiovascular health, with initial findings of a detrimental role and a more recent study suggesting a more complex picture.

The genetic [109] and senolytic (galacto-encapsulated doxorubicin) [110] removal of senescent cells in mouse models of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis led to various improvements in pulmonary function. Accordingly, D + Q or navitoclax treatments attenuated the deficits in the breathing rate of irradiated mice [72], whereas positive anti-fibrotic effects of a senolytic treatment with digoxin were reported in a particular model of lung fibrosis induced by intratracheal administration of senescent human cells [111]. A detrimental effect of senescent cells on lung function was additionally demonstrated in cigarette smoke-treated p16-3MR [112] and p16 KO mice [113], as well as in porcine pancreatic elastase‐induced emphysema ARF-DTR mice, which enabled the elimination of p19ARF-positive senescent cells through diphtheria toxin (DT) administration [114]. Conversely, a recent study in a different model of chronic lung disease reported that the elimination of pulmonary endothelial cells aggravates hypertension and worsens the general hemodynamic [115]. Moreover, a treatment in aged mice with fisetin (a natural compound with senolytic properties) did not report significant effects on a lung lesion score [116], neither there were positive results in a pilot clinical trial with D + Q in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [80]. Based on these last results, it remains challenging to gain a comprehensive understanding of the precise impact of senescent cells on respiratory health. Further research and a larger body of evidence are needed to draw more definitive conclusions in this regard.

Brain function and mental health

Removal of senescent cells by AP or GCV, using models derived from INK-ATTAC or p16-3MR mice, ameliorated cognitive deficits in several experimental models, including tau-mediated neurodegeneration [117], brain irradiation [118], diet-induced obesity [119], and in paclitaxel-induced cognitive impairment [120]. Aged p16 KO mice display preserved cognitive function and reduced decline in subventricular zone proliferation, olfactory bulb neurogenesis, and self-renewal potential of multipotent progenitors compared to the wild-type [121]. These results suggest that p16 expression contributes to aging by reducing progenitor function and neurogenesis in at least certain regions of the nervous system, but it remains unclear whether these effects are dependent on the induction of cellular senescence. In agreement with this hypothesis, treatment with D + Q improved the cognitive function of old mice and rats [71, 122], whereas fisetin ameliorated a lesion score in the brain of aged mice [116]. Excluding the report of a lack of efficacy of navitoclax in a motor neuron disease mouse model [123], all other interventions in experimental models are in agreement with the deleterious role of senescent cells in brain health. Attenuation of the pathology and cognitive improvement was reported by senolytic treatment (navitoclax or D + Q) in two models of neurodegenerative diseases [117, 124], in a mouse model of accelerated brain aging [74] as well as in brain-irradiated mice [118].

Furthermore, genetic and senolytic removal of senescent cells ameliorated the behavioral deficits related to psychiatric disorders in diet-induced obese mice [119].

Hence, regarding this frailty domain, experimental results are quite in agreement with the detrimental role of cellular senescence. Nevertheless, a pilot study in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease patients, with 12-week intermittent orally-delivered D + Q, showed only decreased levels of circulating inflammatory factors without significant effects on cognitive and neuroimaging endpoints [125]. These preliminary data suggest that future randomized placebo-controlled trials with longer follow-up are required for a careful evaluation of the impact of D + Q on cognitive function.

Urogenital, hepatic, and digestive health

This frailty domain encloses the functional status of two important organs, the kidney and the liver, that are the objective of several studies focused on the role of cellular senescence.

The beneficial role of vascular senescent cells in kidney and liver dysfunctions was demonstrated in p16-CreERT2/R26-DTA mice [99], and a similar beneficial role of senescent cells in liver regeneration was observed in p16-3MR mice after partial hepatectomy [126].

Excluding these studies, all other models of chronic kidney or liver dysfunction derived from normally or accelerated aging models as well as induced fibrosis provided evidence of the detrimental role of senescent cells [127] [128] [86] [129]. This is also observed in INK-ATTAC models, where p16-expressing cells are not efficiently removed in the liver and colon [84], further supporting the notion that the removal of senescent cells in some tissues may affect the function of other distant tissues.

Almost all interventions with senolytics have consistently demonstrated a favorable impact on kidney function. In aged mice and other models of kidney dysfunction, D + Q, FOXO4-DRI, and photosensitive senolytics exhibited a notable amelioration of kidney function [82, 87, 127, 128, 130]. Notably, a clinical trial in humans has shown preliminary evidence that D + Q may be beneficial in reducing the inflammatory status of patients with diabetic kidney disease [131]. Additionally, treatment with fisetin was also found to reduce a lesion score in the kidney, but not in the liver, of aged mice [116].

Indeed, the results of senolytics on liver function are still controversial. D + Q reduced hepatic steatosis in aged mice [86], but had no impact on fibrosis markers in Sod1KO mice [132], and worsened the disease progression in a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease model [133]. These results could be partly explained by the inability of D + Q to remove senescent hepatocytes [133]. However, controversial results were also found with another class of senolytic compounds, those targeting Bcl-2-related pathways (ABT-737 and navitoclax). For instance, ABT-737 improved liver regeneration in a partial hepatectomy model [134] and reduced both hepatic and renal fibrosis in a mouse model of accelerated aging [54], whereas navitoclax impaired liver regeneration in a model of partial hepatectomy [126].

The use of advanced senolytic strategies, such as CAR T cells and photosensitive senolytics, has shown promising results in reducing off-target effects. Studies have demonstrated that these approaches hold the potential for restoring tissue homeostasis in liver fibrosis models [135] and improving liver function in aged and irradiated mice [82].

Despite these positive outcomes, the diverse findings also highlight that the impact of senescent cells on liver health is strongly influenced by the specific treatment and experimental models used. This raises the possibility of confounding off-target effects, meaning that the results may be influenced by factors other than the targeted senescent cells.

Interestingly, an intervention with D + Q in aged mice reduced intestinal inflammation and induced changes in specific microbiota signatures [136]. These data confirm that a major off-target effect of some senolytics could be just the intestinal microbiota.

Musculoskeletal health

Not surprisingly, most frailty studies, including those on physical performance outcomes (Tables 2 and 4), are focused on this domain. All these studies are characterized by consistent results on the beneficial effect of systemic [65, 66, 137–140] and specific senescent cell removal [65] on musculoskeletal function. These findings have further support from various p16 KO models related to osteoporosis [141], fracture healing [142], and intervertebral disc degeneration [143].

Overwhelming preclinical evidence from senolytic treatments also confirms the detrimental impact of senescent cells on musculoskeletal health. This is reported for various senolytics in different models [138, 139, 144] (see also Table 4 for outcomes related to physical performances).

Nevertheless, clinical trials in humans have only partly confirmed these results. A significant improvement in the short physical performance battery (SPPB), but not in pulmonary function, was reported in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with D + Q [80], while the local injection of the senolytic UBX0101 failed to improve knee function in osteoarthritis patients [145].

Sensory health

Age-related eye dysfunctions can also be corrected by the elimination of senescent cells in INK-ATTAC models [66, 84]. Similar results were also observed in a model of glaucoma induced in p16-3MR mice [146]. Relatively few preclinical studies with senolytics in mice have focused on eye function and other aspects related to sensory health. D + Q or dasatinib alone have shown positive effects on the age-related vision loss of SAMP10 mice and in a glaucoma model, respectively [74, 146]. Interestingly, a retrospective study in humans examining medical records and exposure to senolytic drugs also suggested a potential positive effect of senolytics on glaucoma [147]. Albeit the results on glaucoma progression were not significant, the small sample size (n = 9 patients with available post-exposure data) and the confirmation of the safety profile of some senolytic drugs (such as tocilizumab, imatinib, or quercetin) warrant further investigation.

Skin health

While the role of transient senescent cells in wound healing was shown to be beneficial [51], a single study focused on the skin health of normally and accelerated aging p16-3MR mice provided evidence of the overall benefits of senescent cell removal on fur density [128].

Skin health is also ameliorated with different senolytic treatments both in normally and accelerated aging mouse models [54, 128, 148, 149], as well as in a mouse model of skin graft from aged humans [150].

Malignant diseases

Malignant diseases can significantly contribute to the clinical FI, both as a consequence of the disease itself or of the therapy.

Although studies in mice overexpressing p16 have clearly provided evidence that cellular senescence is a strong suppressor of tumor cells [151], chronic expression of p16 in specific tissues [152] and accumulating senescent cells during aging have an opposite pro-tumorigenic role. Indeed, the SASP stimulates pre-malignant and malignant cells to form tumors and drive a much more aggressive growth phenotype [153–155]. The detrimental effect of senescent cells on cancer development and progression has been demonstrated in various models of senescent cell transplantation [153–155], as well as in models of chemotherapy-induced senescence in p16-3MR mice [85, 156].

In murine xenograft, transplant, and spontaneous tumor models, both D + Q and several other senolytics have shown that the removal of senescent cells can have preventive effects on tumor formation and relapse [110, 111, 132, 135, 152, 157–162].

However, contrary to conventional expectations, chemotherapy-induced senescent cells were shown to be beneficial in leukemia [163] and hepatic carcinoma models [164]. It has been hypothesized that the increase of senescent cells, due to chemo- and radio-therapeutic treatment, induces SASP-mediated activation of the immune system that results in an overall antitumoral effect. On the other hand, an incomplete elimination of senescent cancer cells by the immune system and the consequent long-term inflammatory state caused by the SASP may promote tumor growth and relapse [165].

ADL and IADL

Only one pilot study, performed with D + Q in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease patients, evaluated an outcome (informant-reported Lawton IADL form) related to IADL without observing any significant change [125].

Healthcare access and utilization

Senolytic trials or retrospective studies in humans focused on healthcare utilization, as well as studies with similar outcomes back translated in mice, are still not available.

Social engagement and activities