Abstract

With the exponential growth in the older population in the coming years, many studies have aimed to further investigate potential biomarkers associated with the aging process and its incumbent morbidities. Age is the largest risk factor for chronic disease, likely due to younger individuals possessing more competent adaptive metabolic networks that result in overall health and homeostasis. With aging, physiological alterations occur throughout the metabolic system that contribute to functional decline. In this cross-sectional analysis, a targeted metabolomic approach was applied to investigate the plasma metabolome of young (21–40y; n = 75) and older adults (65y + ; n = 76). A corrected general linear model (GLM) was generated, with covariates of gender, BMI, and chronic condition score (CCS), to compare the metabolome of the two populations. Among the 109 targeted metabolites, those associated with impaired fatty acid metabolism in the older population were found to be most significant: palmitic acid (p < 0.001), 3-hexenedioic acid (p < 0.001), stearic acid (p = 0.005), and decanoylcarnitine (p = 0.036). Derivatives of amino acid metabolism, 1-methlyhistidine (p = 0.035) and methylhistamine (p = 0.027), were found to be increased in the younger population and several novel metabolites were identified, such as cadaverine (p = 0.034) and 4-ethylbenzoic acid (p = 0.029). Principal component analysis was conducted and highlighted a shift in the metabolome for both groups. Receiver operating characteristic analyses of partial least squares-discriminant analysis models showed the candidate markers to be more powerful indicators of age than chronic disease. Pathway and enrichment analyses uncovered several pathways and enzymes predicted to underlie the aging process, and an integrated hypothesis describing functional characteristics of the aging process was synthesized. Compared to older participants, the young group displayed greater abundance of metabolites related to lipid and nucleotide synthesis; older participants displayed decreased fatty acid oxidation and reduced tryptophan metabolism, relative to the young group. As a result, we offer a better understanding of the aging metabolome and potentially reveal new biomarkers and predicted mechanisms for future study.

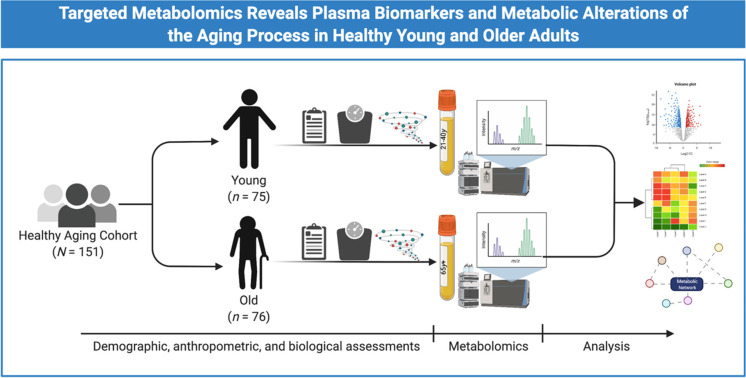

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-023-00823-4.

Keywords: Ageing, Biomarkers, Mass Spectrometry, Metabolites, Metabolomics

Introduction

In the next 50 years, it is estimated that the older adult population (i.e., individuals age 65 and older) will increase by over 200% and will continue to rise worldwide [1]. With the growth of the older population and chronic conditions associated with aging, research aimed at better understanding the aging process has been of paramount interest [2–4]. Prior investigations have demonstrated that competent and adaptive metabolic networks are more prevalent in younger individuals, which facilitates overall health and homeostasis [5]. With aging, many adaptive metabolic systems experience physiological alterations that typically result in functional decline. Studies have recently begun to examine the underlying mechanisms and factors that contribute to these physiologic changes.

The greatest risk for chronic disease development is age [6, 7]. Chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), and cancer are all directly associated with age and influenced through environmental and genetic factors [8]. Many mechanisms have been postulated to explain the association between age and chronic disease. For example, mitochondrial dysfunction has been commonly observed among older adults and is linked to the normal aging process [9]. Current studies have also suggested that the disruption of cellular metabolism may be important in the aging process [10, 11]. Some have hypothesized that fatty acid metabolism may be among the most significantly affected. Diminished levels of beneficial unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) have been previously correlated with age and may be a result of scavenging free radicals [12]. In addition to reduced UFA concentration, harmful saturated fatty acids have been shown to be elevated and are also positively associated with aging [13, 14]. A reduction in heart health promoting fatty acids coupled with an increase in inflammatory lipids may contribute to the prevalence of chronic conditions like CVD, obesity, and T2DM with aging.

To further investigate the metabolic alterations of aging, a comprehensive approach is required. The composition of all metabolic products within a biological system is collectively referred to as the metabolome [15]. Analyzing the end products of metabolism, known as metabolomics, enables the quantification of small molecules (termed metabolites) which serve as markers of active metabolic pathways [16, 17]. Large-scale metabolomics has been used to investigate the effects of aging, such as the identification of potential plasma biomarkers reflecting impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation [18, 19]. Other studies have linked metabolites to cellular function and disease in older subjects [20–27]. Similarly, several metabolomics studies have shown the ability to uncover significant differences associated with chronic conditions and complications of metabolic dysfunction, such as CVD, obesity, and T2DM [20–25]. As a result, metabolomics is a robust method to ascertain metabolic profiles in young and older populations in order to better examine the dysregulated pathways of the aging process.

In this study, we aim to assess how the aging process affects metabolic phenotype independently from gender and existing comorbidities. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate plasma aging biomarkers in young and older adults using a targeted approach and corrected model for sex, BMI, and CCS to isolate biomarkers and trends of the normal aging process.

Materials and methods

Participants

Subjects in this analysis were part of the Healthy Aging Cohort (PI—Nikolich-Žugich) at the University of Arizona. This cohort consists of over 900 research subjects recruited in southern Arizona who vary in age from 21 to over 90. The current study is based on 75 subjects between the age of 21 and 40 and 76 subjects ≥ 65. All subjects had banked PBMCs and plasma available for analysis. All subjects filled out a medical questionnaire which includes standard demographics, assessment for the presence of chronic disease (cancer, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, coronary artery disease, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, arthritis) and frailty (Fried Frailty Index), which includes daily physical activity assessment, weight loss or gain, grip strength, walking speed, and exhaustion. Subjects with chronic conditions were not excluded from the study; to control for the influence of chronic disease on the plasma metabolome, CCS was calculated and included as a covariate in statistical analysis (see Sect. "Statistical Analysis"). All subjects had their weight and height measured for assessment of body mass index (BMI).

Biological markers assessment

Plasma cytokine and chemokine concentrations were performed using cytokine bead array kits from Becton Dickinson. An ultrasensitive cytokine kit detecting IL-1, IL -6, and TNF was used with a sensitivity of 10 fg/mL. The chemokines measured were RANTES, MIG, IP-10, MCP-1 and IL-8 using a kit with a sensitivity of 10 pg/mL.

Sample preparation for metabolomic analyses

Plasma samples comprised of 50 μL were initially mixed homogenously in a solution of 500 μL MeOH and 50 μL internal standard solution (1 × PBS containing 1.81 mM L-lactate-13C3 and 142 μM L-glutamic acid-13C5). Prior to centrifuging at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, the mixtures were vortexed for 5 s and stored for 20 min at -20˚C. The supernatant (450 μL) was collected from each sample container and administered into a new 2 mL Eppendorf vial. The samples were then dried in a CentriVap Concentrator (Fort Scott, KS) at 37˚C for 120 min. Afterward, 150 μL of 40% PBS/60% acetonitrile (ACN) was used to reconstitute the samples, which were then vortexed for 5 s. After centrifuging at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant (100 μL) was collected and transferred to a LC vial for LC–MS/MS analysis. The residual 50 μL of each supernatant was combined to generate quality control (QC) samples. Throughout the LC–MS/MS analysis, the QC sample was run for every 10 study samples.

LC–MS/MS analysis

A LC–MS/MS targeted analysis of plasma samples was accomplished using an Agilent Technologies 1290 UPLC-6490 QQQ MS system (Santa Clara, CA). An Xbridge® BEH Amide column (2.5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm; Waters, MA) at a temperature of 40˚C for liquid chromatography separation. A positive ionization mode of 4 μL and negative ionization mode of 10 μL was utilized for each sample injection volume with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. A 10 mM NH4OH and 10 mM NH4OAc in ACN stock solution was employed. The LC system mobile phase contained solvents A (ACN: stock = 5:95) and B (ACN: stock = 95:5) for both positive and negative ionization modes. For both ionization modes, the same LC gradient was used. At the start of each run, the samples underwent a 1.0 min isocratic elution of 10% A, the gradient percentage was then linearly increased to 60% at t = 11 min. The percentage of A at t = 15.5 min was then reduced to 10% in preparation for the next injection. The net experimental time for each individual sample was 30 min.

Specific conditions were utilized for the QQQ mass spectrometer. For positive and negative ionization modes, the capillary voltage was 3.5 kV, gas temperature was set at 175˚C, nitrogen flow rate was continuously 15 L/min. The sheath gas was set to 225˚C, the flow rate of the sheath gas was fixed at 11 L/min, and the nebulizer was set to 30 psi.

Statistical analysis

Participants were stratified into two age groups: the young group was comprised of participants aged 21–40 years, while the older group identified as 65 years and older. BMI was split into three categories: normal weight (< 25 BMI), overweight (25 < BMI < 30), and obese (BMI > 30). CCS, as previously described in the literature and a common approach in epidemiological studies [26–28], was calculated by the presence or pre-existence of the following: hypertension, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), cancer, stroke, heart attack, lung disease, and arthritis. A corrected general linear model (GLM) to analyze age with sex, BMI, and CCS covariates with Bonferroni correction was employed using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) was used to measure the participant descriptive statistics. Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to assess gross separation between study groups; supervised partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was used to construct a multivariate model predictive of young and old groups. Pathway and enzyme topology and enrichment models were log-transformed and analyzed between groups using MetaboAnalyst software [29]. For pathway analysis, impact was calculated using a hypergeometric test, while significance was determined using a test of relative betweenness centrality. Bonferroni correction was not applied to pathway and enzyme enrichment analyses since these analyses involve testing the significance of multiple related hypotheses, rather than independent hypotheses, which is too conservative, resulting in false negative results. All metabolomics data were log-transformed and Pareto scaled to approximate normality prior to analysis.

Results

Participant characteristics

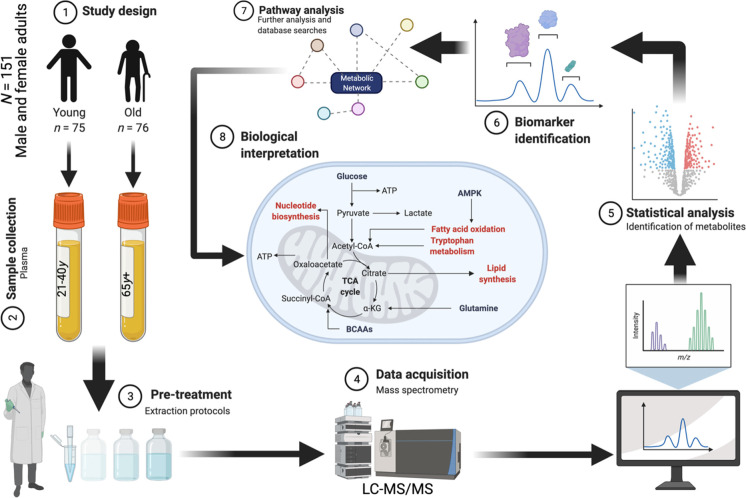

Figure 1 shows a graphical schema of the analytical workflow. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 151 subjects that make up the study population. Individuals aged 21–40 years (n = 75) were placed in the young group and had an average age of 30.08 years, while the older group (n = 76), ages 65 years and above, had a mean age of 73.97 years. The ratio of women to men was equal in both groups. Anthropometric calculations revealed a similar mean BMI measurement and standard deviation in both the young and old groups (28.75 ± 7.07 kg/m2 and 29.03 ± 6.81 kg/m2, respectively). Based upon BMI measurement, the participants in both groups were stratified into normal weight, overweight, and obese. All three groups demonstrated comparable means and standard deviations for two age groups. No significant differences in plasma chemokines or cytokines were observed between study groups, nor was there a significant difference in CCS (two-tailed heteroscedastic t-test p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the analytical workflow of the current study. Created with BioRender.com

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical statistics of study participants

| Descriptive statistics* | Young (21-40y) | Old (65y +) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.08 ± 5.31 | 73.97 ± 6.73 |

| Participants (n) | 75 | 76 |

| Men | 34 | 34 |

| Women | 41 | 42 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.75 ± 7.07 | 29.03 ± 6.81 |

| Normal Weight | 21.71 ± 2.29 | 22.28 ± 2.13 |

| Overweight | 27.26 ± 1.47 | 27.64 ± 1.28 |

| Obese | 35.59 ± 5.60 | 36.02 ± 4.58 |

| Plasma chemokines | ||

| IP-10 | 156.48 ± 134.14 | 208.66 ± 176.20 |

| MCP-1 | 91.45 ± 85.67 | 116.98 ± 201.13 |

| MIG | 72.49 ± 106.17 | 172.98 ± 222.44 |

| RANTES | 2658.92 ± 1789.29 | 3086.67 ± 1774.94 |

| IL-8 | 55.45 ± 242.60 | 47.45 ± 291.21 |

| Plasma cytokines | ||

| IL17A | 6.60 ± 14.95 | 10.52 ± 19.20 |

| IFN-g | 0.36 ± 2.86 | 0.01 ± 0.08 |

| TNF | 0.19 ± 0.64 | 0.08 ± 0.48 |

| Sensitive TNF | 3.49 ± 32.69 | 5.61 ± 54.07 |

| IL-10 | 0.25 ± 0.93 | 0.19 ± 0.47 |

| IL-6 | 2.56 ± 9.06 | 2.71 ± 5.84 |

| Sensitive IL-6 | 3.53 ± 23.87 | 7.22 ± 45.49 |

| IL-4 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.09 |

| IL-2 | 0.23 ± 1.90 | 0.02 ± 0.14 |

| IL-1β | 0.52 ± 1.83 | 0.15 ± 0.65 |

| Sensitive IL-1β | 0.54 ± 4.23 | 0.73 ± 6.82 |

| TNFR 1 | 56.73 ± 49.58 | 112.56 ± 72.16 |

| TNFR 2 | 1217.44 ± 721.81 | 1134.85 ± 534.25 |

| Chronic condition score (CCS) | 0.037 ± 0.163 | 0.907 ± 0.881 |

*Data are represented by mean ± SD

General linear modelling

In total, 335 metabolites of both phase I (CYP450 reactions) and phase II (conjugation reactions) metabolism were targeted for detection in the current study. Targeted metabolites were representative of nearly 60 canonical human pathways; the full list of targeted metabolites and their associated pathways is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Of these, 109 metabolites were reliably detected from human plasma samples using LC–MS/MS (quality control (QC) CV < 20%, relative abundance > 1,000 in 80% of samples). Relative levels of these 109 metabolites had a median coefficient of variation (CV) of 12.6% (CV range: 0.8%-17.5%), and ~ 62% of captured metabolites had QC CV < 15% (Supplementary Fig. S1). These metabolites spanned 20 different chemical classes and were representative of more than 35 metabolic pathways of potential biological relevance.

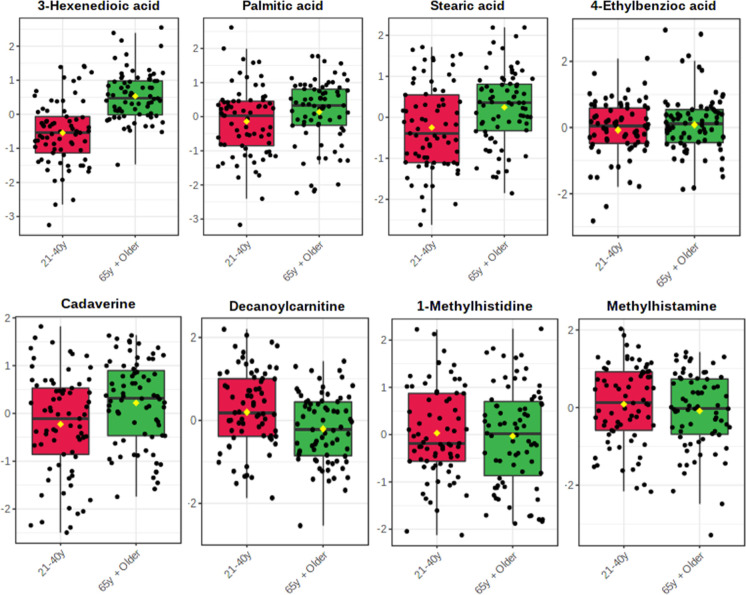

A metabolomic analysis was conducted to examine the effects of aging on the metabolome. A corrected GLM (adjusted for sex, BMI, and CCS) with Bonferroni post-hoc adjustment was assembled, and fold change (FC) analysis was performed as old/young; GLM results along with FC information are given in Supplementary Table S2 and results are shown as a volcano plot in Supplementary Fig. S2. It was found that 3-hexenedioic acid (p < 0.001), palmitic acid (p < 0.001), and stearic acid (p = 0.005) were among the most significant, all being elevated in the older population. Amino acid derivatives such as 1-methylhistidine (p = 0.035) and methylhistamine (p = 0.027) were also identified as significantly decreased in the older population. Additionally, the benzoic acid intermediate 4-ethylbenzoic acid (p = 0.029), and cadaverine (p = 0.034) were significantly increased in the older group while decanoylcarnitine (p = 0.036) was significantly decreased in the older group. It should be noted that, although significant main effects of age were observed, the magnitude of FC was low for these eight significant features (FC = 0.695 – 1.306). An alternative generalized linear model (GLM) was employed, which incorporated adjustments for sex, BMI, and the presence or absence of individual chronic conditions, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cancer, stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary disease, and arthritis. Upon examination of this model, which considered the distinct components of the CCS independently, only two metabolites demonstrated significant associations: decanoylcarnitine (p < 0.001) and 4-ethylbenzoic acid (p = 0.044). Notably, the level of significance for decanoylcarnitine markedly increased, whereas a slight attenuation in the between-group significance was observed for 4-ethylbenzoic acid. In our study, we opted to use the CCS instead of considering the absence or presence of individual diseases in the covariate control of the model. The primary rationale behind this decision was to simplify the analysis and reduce the number of covariates, which can help avoid overfitting and multicollinearity issues, particularly when dealing with a limited sample size. Additionally, the CCS allows for a more parsimonious representation of the overall chronic disease burden, providing a single, composite measure that captures the cumulative impact of multiple comorbidities on study outcomes.

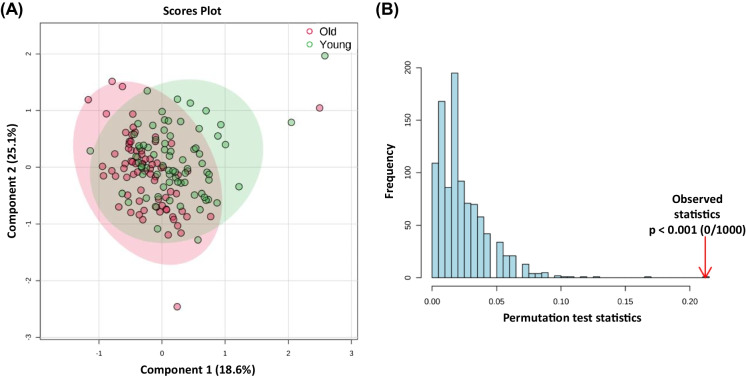

In Fig. 2, significant metabolites are graphically represented as box plots. The significance of cadaverine and the three fatty acids, 3-hexenedioic acid, palmitic acid, and stearic acid illustrated elevated levels in the older group, whereas decanoylcarnitine and methylhistamine are notably increased in the young group. A heatmap of significant metabolites showing normalized relative abundance between old and young study groups is given in Supplementary Fig. S3. PCAs were constructed using levels of all reliably detected metabolites and separation was compared across PCs 1–3 (Supplementary Fig. S4A–C), as well as the significant between-group metabolites (Supplementary Fig. S4D) to further examine gross metabolic differences in young and older adults. Although no gross separation was observed, the first two principal components accounted for 52.1% of observable variance, suggesting the GLM-derived metabolites as critically important features of the aging process. In Supplementary Fig. S5, we present a comprehensive visual analysis of the metabolic differences between patients with and without specific health conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, lung disease, and arthritis, by employing two-dimensional PCA plots based on all reliably detected metabolites. Notably, we observed very similar separation patterns between cancer, stroke, and lung disease, indicating a possible shared metabolic signature among these conditions. A PLS-DA model was constructed using levels of significant between-group metabolites and accounted for 43.7% of between-group variance (Fig. 3A). Although the PLS-DA model also displayed appreciable accuracy (R2X = 0.728), it exhibited low explanatory capacity (R2Y = 0.190) and poor predictive capacity (R2Q = 0.067). Importantly, the PLS-DA model was permutated 1000 × and was not shown to be overfit (Fig. 3B; observed p < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Significant between-group metabolites as determined by GLM adjusted for sex, BMI, and CCS (see Supplementary Table S2 for Bonferroni adjusted p values). Yellow diamonds signify groups means

Fig. 3.

PLS-DA between younger and older adults using levels of significant metabolites as determined by covariate-controlled general linear modeling. (A) PLS-DA scores plot shows 43.7% of accounted variance between study groups (R2X = 0.728, R2Y = 0.190, R.2Q = 0.067). (B) Permutation testing by 1000 iterations shows acceptable model fit (observed p < 0.001)

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis

Levels of significant between-group metabolites (see Supplementary Table S2, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3) were used to construct separate PLS-DA models for the classification of age, cancer, type II diabetes (T2D), hypertension, stroke, and arthritis. ROC analysis was performed on PLS-DA y-values to assess the classification accuracy of the candidate aging markers in discriminating known chronic conditions (Supplementary Fig. S6). Expectedly, the candidate markers showed acceptable classification of older adults as evidence by area under curve (AUC = 0.740). However, PLS-DA models constructed with aging-related markers performed poorly for the classification of cancer (AUC = 0.505), T2D (AUC = 0.547), hypertension (AUC = 0.514), stroke (AUC = 0.593), and arthritis (AUC = 0.508). These results suggest that candidate markers discovered in the current study are specific to aging, and that the metabolic effects of aging are distinct from the chronic conditions profiled.

Correlation analysis

Correlation analysis was performed to test possible associations between the set of significant between-group metabolites and measured plasma chemokines and cytokines. One correlation was found with Pearson’s r > 0.5 and p < 0.05: palmitic acid showed a strong, significant association with stearic acid (r = 0.539, p < 0.001). One candidate metabolite marker showed a significant association with one plasma marker of inflammation: palmitic acid and MIG were significantly, though modestly, correlated (r = 0.203, p < 0.05). Interestingly, the inflammatory cytokines were all correlated with each other. Specifically, IL-6 was moderately but significantly correlated with IL-1β (r = 0.302, p < 0.001) and TNF (r = 0.470, p < 0.001). TNF and IL-1β showed significant associations as well (r = 0.414, p < 0.001). Finally, IL-10 showed weak, significant associations with IL-2 (r = 0.192, p < 0.05) and IFN-g (r = 0.247, p < 0.01). Similarly, the chemokines also showed correlations between themselves. Specifically, MCP-1 was positively associated with IL-8 (r = 0.177, p < 0.05), and IP-10 (r = 0.375, p < 0.001). A correlation heatmap is visualized in Supplementary Fig. S7. Full details of flagged correlations (p < 0.05) between significant metabolites and biological markers are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Magnitude of flagged correlations (p < 0.5) between significant metabolites and biological markers

| Sensitive IL-6 | Sensitive TNF | IL-10 | IFN-g | MCP-1 | IP-10 | TNF | IL-8 | Palmitic acid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive TNF | 0.470 | 0.351 | 0.212 | ||||||

| Sensitive IL-1β | 0.302 | 0.414 | 0.165 | 0.154 | |||||

| IFN-g | 0.247 | 0.184 | 0.310 | ||||||

| IL-2 | 0.192 | 0.349 | 0.182 | ||||||

| IP-10 | 0.278 | 0.351 | 0.268 | 0.310 | 0.375 | 0.253 | |||

| MIG | 0.170 | 0.416 | 0.223 | 0.203 | |||||

| IL-4 | 0.174 | 0.237 | 0.792 | ||||||

| IL-8 | 0.234 | 0.212 | 0.177 | 0.253 | |||||

| IL-6 | 0.373 | 0.227 | 0.210 | 0.207 | 0.185 | 0.166 | |||

| Stearic acid | 0.539 |

Interestingly, measured cytokines/chemokines were grouped by specific immune phenotypes. Significant correlations between sensitive IL-1β, TNF, and IL-6 are characteristic of the classic immunosenescence phenotype [30], while clustering between MCP-1, IP-10, and MIG are indicative of chronic lymphocytic inflammation [31]. Furthermore, observed correlations between IL-10, IFN-g, and IL-2 were consistent with the typical Th1 profile [30]. To assess whether these cytokines/chemokines differed by young and old, PCA was performed between groups using these specific immune markers. However, PCA analysis of young and old groups showed no appreciable separation between either comparison (Supplementary Fig. S8). Notably, however, the three markers in each respective comparison accounted for between 78 to 90% of total between-group variance.

Pathway/enzyme enrichment analysis

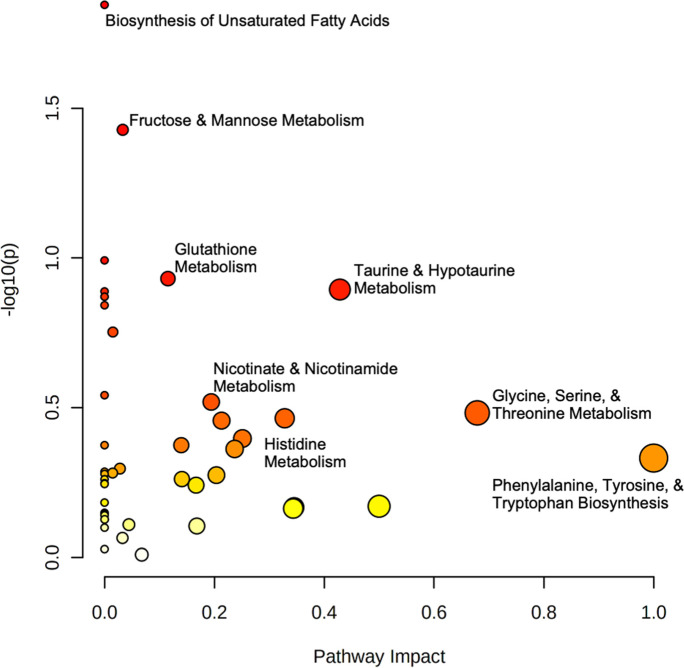

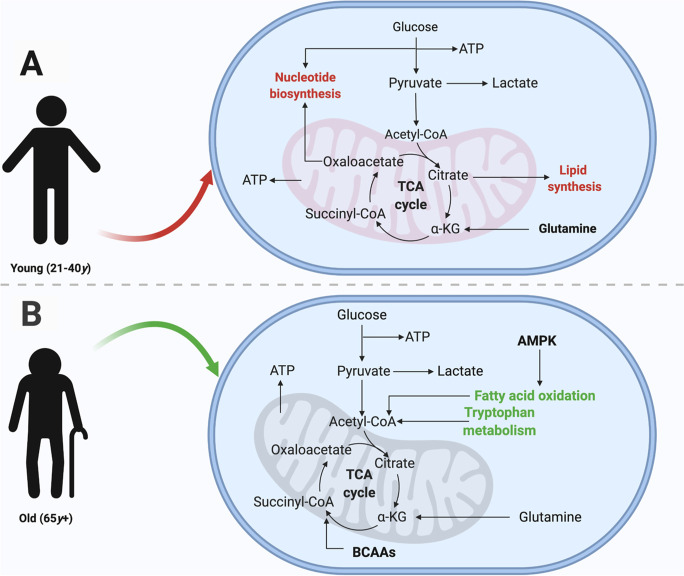

Pathway and enrichment analyses were conducted to investigate the effects of the aging process beyond univariate comparison. Given the variable importance of metabolites in canonical human pathways (i.e., relative weights of the same feature in different pathways), the entire set of reliably detected metabolites was used for enrichment and topology analyses. In these analyses, multiple related hypotheses share underlying biological mechanisms or functional relationships and are therefore not completely independent, and hence Bonferroni correction was not applied to p-values since correction for multiple testing is too conservative and is prone to false negative results. Pathway analysis (Fig. 4) identified the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (p = 0.014) and fructose and mannose metabolism (p = 0.037) as having the greatest significance, while the greatest impact (I) was observed in phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis (I = 1.0) as well as glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism (I = 0.679). Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism (I = 0.428), histidine metabolism (I = 0.213), nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism (I = 0.194), and glutathione metabolism (I = 0.115) also displayed marked pathway impacts. Meanwhile, enzyme enrichment analysis (Fig. 5) was performed using the entire set of reliably detected metabolite and queried against more than 900 sets of metabolites associated with dysfunctional enzymes and revealed oxygen transport in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondrial carnitine O-acetyltransferase, peroxisomal ATP transport, very long-chain fatty acid ligase, and intracellular bile acid transport were among the most enriched in the older age group (p < 0.05). In the younger cohort, pathway and enzyme enrichment results indicated primary impacts on nucleotide biosynthesis and lipid synthesis; cumulatively, results showed greater relative abundance of metabolites and greater functional changes in enzymes embedded in these pathways. In the older cohort, collated pathway and enrichment analysis results showed diminished fatty acid oxidation and tryptophan metabolism as compared to the younger group. Results of our pathway and enzyme enrichment analysis were synthesized to form an integrated hypothesis and are summarized in Fig. 6.

Fig. 4.

Log-transformed pathway analysis of aging affects in young and older adults. Data is plotted as -log10(p) versus pathway impact. Node size corresponds to proportion of metabolites captured in each pathway set, while node color signifies significance

Fig. 5.

Network view of enzyme enrichment analysis of aging effects in young and older adults. Data analyzed as 65y + /21-40y

Fig. 6.

Predicted functional profile of normal aging integrated from pathway and enzyme enrichment analyses. Red and green lettering denote increases and decreases in levels of metabolites within specified pathways, respectively. (A) Compared to older participants, the young group displayed greater abundance of metabolites related to lipid and nucleotide synthesis. (B) Older participants displayed decreased fatty acid oxidation and reduced tryptophan metabolism, relative to the young group. Created with BioRender.com

Discussion

In this work, we have used a targeted metabolomics approach to identify reliable plasma biomarkers of the aging process and differences in metabolic pathways related to aging. Results of our sex-, BMI-, and CCS-adjusted GLM showed significant differences (p < 0.05) in eight plasma metabolites between young and old study groups (Supplementary Table S2, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3). While considering individual chronic conditions in the model might offer a more detailed view of the specific effects of each disease on the metabolome, the CCS approach balances this level of detail with the need to maintain a manageable model that yields interpretable and reliable results. Furthermore, using the CCS in the analysis still allowed us to identify significant metabolic signatures associated with aging, suggesting that our chosen method effectively controlled for potential confounding effects of chronic diseases on the metabolome. A PLS-DA model constructed using levels of the eight candidate markers (Fig. 3A) showed modest classification of aging (Supplementary Fig. S6A) and acceptable model fit (Fig. 3B). Although no significant correlations were observed between metabolites and inflammatory markers, significant associations were observed within fatty acids and markers linked to classical immunosenescence phenotype, chronic lymphocytic inflammation, and the typical Th1 profile (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S7). Importantly, enzyme- and pathway-level analyses revealed that younger subjects displayed greater abundance of metabolites related to lipid and nucleotide synthesis while older participants displayed decreased fatty acid oxidation and reduced tryptophan metabolism (Figs. 4, 5, and 6).

Prior studies have demonstrated that age is the largest risk factor for chronic disease, probably due to younger individuals possessing more abundant adaptive networks that result in overall homeostasis [5, 6]. As individuals age, perturbations occur throughout the metabolic system that contribute to a decline in function. Recent studies suggest a collective, underlying feature among older adults is the disturbance in cellular metabolism [10, 11]. It has been shown that reduced cellular function is frequently linked with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) dysregulation, resulting in oxidative stress [32]. As an oxidizing agent in cellular respiration, the depletion of NAD+ initiates an imbalance of redox homeostasis and escalates aging [33, 34]. The increased oxidative stress not only damages protein and DNA structure, but has also been shown to significantly impact lipid metabolism.

Fatty acid compounds, such as unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) in particular, are mostly known to improve cardiometabolic function through the reduction of inflammation and cholesterol levels while their antagonist, saturated fatty acids (SFAs), largely increase circulating cholesterol resulting in increased risk of atherosclerotic events [35]. As aging occurs, the ration between UFAs and SFAs decline as a result of oxidative damage. In our corrected GLM, controlled for such covariates as gender, BMI, and CCS, we found that fatty acid compounds were among the most significantly elevated in the older population group (Fig. 2). As a saturated long-chain fatty acid (LCFA), the metabolism of palmitic acid (p < 0.001) has been shown to significantly increase throughout the lifecycle [14, 36]. In addition, high concentrations have been commonly linked with inflammation and associated with obesity. After entering the cell, it inhibits the metabolism of UFAs to less harmful triacylglycerols by promoting oxidative stress and its own conversion to diacylglycerols (DAGs), which saturates the conversion enzymes with substrates [37, 38]. When it is metabolized to DAGs and phospholipids, palmitic acid results in further stress to the endoplasmic reticulum, which leads to the damage of its structure [39, 40]. Studies have also shown the destructive influence of palmitic acid on mitochondrial function and the substantial increase in reactive oxygen species, which allow for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to accumulate within in the mitochondria and further promote oxidative damage [41, 42]. With the use of the same parent study populations, a separate analysis controlled for gender, BMI, physical activity, and systolic blood pressure and discovered significant metabolites associated with cell apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction [43]. The dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism throughout the aging process is only exacerbated in the presence of palmitic acid.

Our results also demonstrated an additional saturated LCFA, stearic acid, increased with age, but its metabolic effects align more similarly with UFAs [14]. Rather than increasing inflammation and atherosclerotic risk, it has demonstrated ability to reduce hypertension, cardiometabolic dysfunction, and incidence of cancer [44, 45]. It has been proposed that the body utilizes stearic acid to control the mitochondria through mitochondrial fusion via mitofusin-2, a membrane protein facilitating cell metabolism, within hours of intake. Stearic and palmitic acid have also been shown to reduce circulating long-chain acylcarnitine and improve fatty acid metabolism [46]. Decanoylcarnitine (p = 0.036), a fatty ester lipid and acylcarnitine derivative, was significantly increased in the younger group. The acylcarnitine class of compounds are transport molecules for LCFAs to undergo fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in the mitochondria for cellular energy [47]. Acylcarnitine is involved in many other components of cell metabolism, such as stimulating pyruvate dehydrogenase to increase oxidation of pyruvate and glucose [48]. Previous studies suggest that as aging occurs, acylcarnitine levels should increase [18, 49]. A longitudinal study was employed to examine aging and the effects of gender in older adults; it was found that sphingolipids were elevated in women and decreased in men, while acylcarnitine was increased in both genders [50]. The current findings demonstrated reduced levels in the older group, which may be a function of the significantly elevated stearic acid.

In addition, 3-hexenedioic acid was also elevated in our older population. While an unsaturated dicarboxylic acid, 3-hexenedioic acid has shown to increase with the inhibition of FAO and altered mobilization. The medium-chain product from FAO of long chain 3-hydroxy dicarboxylic acids, it is tasked with cellular signaling and stabilizing membranes [51]. As a significant UFA in the older group, 3-hexenedioic acid is susceptible to lipid peroxidation, but does not appear to be nearly as affected by oxidative stress as other similar fatty acids. The compound has yet to be identified in previous aging studies and warrants future research for its potential function throughout the aging process.

An intriguing metabolite, cadaverine, was found to be elevated in the older population. An uncommon diamine, cadaverine concentrations are very low in humans [52]. A bacterial decarboxylation product of lysine, it is typically formed by protein hydrolysis of deteriorating tissue [53]. As a result, cadaverine has been implicated as a potential biomarker for human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and periodonitis [54, 55]. Also due to its polycation structure, it has the ability to exert cytoprotective effects against acidic and oxidative stresses [56]. Previous research has shown that cadaverine is capable of scavenging alkyl, hydroxyl, and peroxyl radicals [57]. Interestingly, its concentration is thought to decrease with age and replacement of cadaverine has proven effective [58, 59]. Yet to be highlighted among most human aging studies and the occurrence in older individuals being indicative of disease, an emphasis should be placed on cadaverine in prospective studies.

A critical component of aging is the potential decline in cognition and later onset of neurodegenerative disease. Current studies have begun to look at amino acid metabolism for its role in cognitive impairment. A conditionally essential amino acid and free radical scavenger, L-histidine has demonstrated its neuroprotective effects with conditions, such as cerebral ischemia, brain infarction, and brain edema [60–62]. L-Histidine and its byproducts also have been shown to decline with age due to oxidative stress [14]. In this regard, we found 1-methylhistidine and methylhistamine to be lower in the older population. 1-methylhistidine is a well-known biomarker of meat intake due to anserine metabolism [63]. Additionally, methylhistamine is a product of the decarboxylation of L-histidine to histamine and a biomarker for mast cell proliferation and anaphylaxis [64]. The elevated presence of both metabolites in the younger population may be mostly attributable to their diet and the oxidative stress of the older age group.

The final metabolite found to differ between young and old subjects was 4-ethylbenzoic acid, being higher in the older population. 4-ethylbenzoic acid is a potential environmental toxin that has been linked with cellular membrane damage in lung tissue from tobacco smoke. Incidence was more pronounced with prolonged interaction and with alkyl substitution of the aromatic ring, which may lead to a secondary effect of exposing the cell to additional toxins [65]. An additional study found that exposure to 4-ethylbenzoic acid induced metabolites linked to the biosynthesis of steroid hormones like 11β-hydroxyprogesterone, a potent mineralocorticoid [66]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first aging study to identify 4-ethylbenzoic acid and prolonged exposure in the older population may explicate its significance.

To examine the difference in the metabolome of young and older individuals, log-transformed, Pareto-scaled PCAs were performed (Supplementary Fig. S4). The PCA model exhibited a trend of two distinct groupings. While there is some overlap between the groups, it demonstrates the separation among the metabolomes during the aging process.

Pathway and enrichment analyses were performed to better understand how age may affect the metabolome (Figs. 4 and 5). The findings identified several pathways associated with alterations of lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and oxidative stress (Fig. 6). The biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (p = 0.014) and fructose and mannose metabolism (p = 0.037) were determined to be among the most significant. Due to the depletion of UFAs, possibly as a result of free radical damage, and the importance of UFAs in cell and organelle membranes, elevated biosynthesis would be an expected outcome in older populations [67]. Meanwhile the metabolism of fructose and mannose has been typically associated with the production of nucleotide sugar substrates for the synthesis of N-glycan anchor proteins within the ER [68]. The biosynthesis and metabolism of several amino acids were also very prominent between the two groups. Recent studies have discovered that glycine accumulates throughout the lifecycle due to the reduced expression of catabolic enzymes. The excess glycine subsequently fuels the methionine cycle, which has been largely associated with enhanced aging [69, 70]. Histidine metabolism also exhibited an impact on the metabolome with the two major derivatives of 1-methylhistidine and methylhistamine, displaying significance. Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis had the largest impact between the two groups with a maximal impact of 1.0. Phenylalanine and tryptophan concentrations have shown to be decreased in older individuals, which would explain the maximal impact on their biosynthesis between the young and older populations [71]. Additionally, a substrate for de novo production of NAD+ is the degradation of tryptophan via the kynurenine pathway [72]. Given the reduction of tryptophan in the older group (p = 0.11), the NAD+ biosynthetic pathway may be similarly affected.

As expected, the pathway analysis identified the impact of nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, which would further demonstrate the potential role of NAD+ and oxidative stress in the aging process. Also referred to as vitamin B3 or niacin, nicotinate and nicotinamide are the precursors for NAD+ and NADP+ production and have shown to be metabolites associated with anti-inflammatory effects [73]. The metabolism of taurine and hypotaurine demonstrated a profound impact between the groups. Utilizing the cysteine sulfonic acid pathway, taurine and its derivative regulate fat metabolism through the absorption and recycling of bile acids and have also been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties [74]. The enrichment analysis identified precited differences in intracellular bile acid transport and a probable link to dysregulated lipid metabolism. In addition, the analysis discovered alterations in mitochondrial carnitine O-acetyltransferase (CRAT), the enzyme tasked with transferring acyl groups from acetyl-CoA to carnitine to support fatty acid β-oxidation [75]. Similarly related to the negative effects of ATP accumulation in the mitochondria due to elevated palmitic acid concentrations, peroxisomal transport of ATP was found to be impacted between study groups. The GLM, pathway, and enrichment analyses expanded upon many of the components that have been referred to as the hallmarks of aging as well as provided novel metabolites for further investigation in the aging process.

Despite our results, the study was not without limitations. We were not able to link alterations in the metabolome with markers of systemic inflammation or clinical phenotypes. This may be due to the fact that these samples were from the baseline evaluation of a relatively healthy aging population enrolled in a longitudinal study (The Healthy Aging Cohort). As such, this was a cross-sectional analysis, which does not allow for longitudinal analysis of repeated measures. Reassessment of these subjects after several years may reveal that perturbations in the metabolome predict which subjects will ultimately develop diseases typically associated with aging. Furthermore, the current study did not achieve conventional power (1 – β < 0.80). Given the high probability of unobserved latent effects, prospective studies should enroll more participants to ensure adequate sensitivity. Nevertheless, relevant covariates such as sex, BMI, and CCS were controlled for in the current study and, indeed, interaction effects (i.e., age X covariates) were neither tested nor powered. Future studies are warranted to expand the current significant effects, which are likely to grow with larger samples.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we compared the metabolome of young and older adults and demonstrated significant impairment in lipid metabolism and transport in the older population. Additionally, novel age-associated metabolites were identified and require further investigation for their potential role. Principal component analysis demonstrated a shift in the metabolome with aging. Pathway and enrichment analyses uncovered several impacted metabolic pathways and associated enzymes that may underpin the metabolic alterations in the older population and further aid in understanding the aging process. As a result, we offer a better understanding of the aging metabolome and potentially reveal new biomarkers for future study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging U01 AG060900.

Abbreviations

- ACN

Acetonitrile

- AUC

Area under curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CCS

Chronic condition score

- FAO

Fatty acid oxidation

- GLM

General linear model

- HTN

Hypertension

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- PLS-DA

Partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- QC

Quality control

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD

Standard deviation

- MS/MS

Tandem mass spectrometry

- QQQ

Triple quadrupole

- T2DM

Type-2 diabetes mellitus

- UFA

Unsaturated fatty acid

Author contributions

Conceptualization: H.L.T. and H.G.; Data curation: P.J. and J.P.; Formal analysis: P.J. and J.P.; Funding acquisition: H.L.T. and H.G.; Investigation: P.J., Y.J. and P.S.; Methodology: P.J., Y.J. and P.S.; Project administration: H.L.T. and H.G.; Resources: J.N., K.S.K., G.M.W., H.L.T. and H.G.; Software: P.J. and J.P.; Supervision: H.L.T. and H.G.; Validation: P.J.; Visualization: P.J. and J.P.; Writing – original draft: P.J., J.P., H.L.T. and H.G.; Writing—review & editing: P.J., J.N., J.P., K.S.K., G.M.W., H.L.T. and H.G.;

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Homer L. Twigg, III, Email: htwig@iu.edu.

Haiwei Gu, Email: hgu@fiu.edu.

References

- 1.Kalache A, Gatti A. Active ageing: a policy framework. Adv Gerontol. 2003;11:7–18. [PubMed]

- 2.Gu H, et al. 1H NMR metabolomics study of age profiling in children. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:826–833. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houtkooper RH, et al. The metabolic footprint of aging in mice. Sci Rep. 2011;1:134. doi: 10.1038/srep00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spinelli R, et al. Molecular basis of ageing in chronic metabolic diseases. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43:1373–1389. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soltow QA, Jones DP, Promislow DEL. A network perspective on metabolism and aging. Integr Comp Biol. 2010;50:844–854. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niccoli T, Partridge L. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R741–R752. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman JM, Lyu Y, Pletcher SD, Promislow DEL. Proteomics and metabolomics in ageing research: From biomarkers to systems biology. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:379–388. doi: 10.1042/EBC20160083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen K, Vaupel JW. Determinants of longevity: Genetic, environmental and medical factors. J Intern Med. 1996;240:333–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.d01-2853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Otín C, Galluzzi L, Freije JMP, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Metabolic control of longevity. Cell. 2016;166:802–821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkel T. The metabolic regulation of aging. Nat Med. 2015;21:1416–1423. doi: 10.1038/nm.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adav SS, Wang Y. Metabolomics signatures of aging: recent advances. Aging Dis. 2021;12:646–661. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills KF, et al. Long-term administration of nicotinamide mononucleotide mitigates age-associated physiological decline in mice. Cell Metab. 2016;24:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan S, et al. Metabonomic characterization of aging and investigation on the anti-aging effects of total flavones of Epimedium. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:1204–1213. doi: 10.1039/b816407j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson LC, et al. The plasma metabolome as a predictor of biological aging in humans. Geroscience. 2019;41:895–906. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00123-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu H, Zhang P, Zhu J, Raftery D. Globally optimized targeted mass spectrometry: reliable metabolomics analysis with broad coverage. Anal Chem. 2015;87:12355–12362. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi X, et al. Database-assisted globally optimized targeted mass spectrometry (dGOT-MS): broad and reliable metabolomics analysis with enhanced identification. Anal Chem. 2019;91:13737–13745. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Z, et al. Human serum metabolic profiles are age dependent. Aging Cell. 2012;11:960–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menni C, et al. Metabolomic markers reveal novel pathways of ageing and early development in human populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1111–1119. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barton S, et al. Targeted plasma metabolome response to variations in dietary glycemic load in a randomized, controlled, crossover feeding trial in healthy adults. Food Funct. 2015;6:2949–2956. doi: 10.1039/C5FO00287G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abu Bakar MH, et al. Metabolomics – the complementary field in systems biology: a review on obesity and type 2 diabetes. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:1742–1774. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00158G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasbi P, et al. Breast cancer detection using targeted plasma metabolomics. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2019;1105:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parent BA, et al. Parenteral and enteral nutrition in surgical critical care: Plasma metabolomics demonstrates divergent effects on nitrogen, fatty-acid, ribonucleotide, and oxidative metabolism. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:704–713. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newgard CB. Metabolomics and metabolic diseases: Where do we stand? Cell Metab. 2017;25:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jasbi P, et al. Coccidioidomycosis detection using targeted plasma and urine metabolic profiling. J Proteome Res. 2019;18:2791–2802. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quan H, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halfon P, et al. Measuring potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:573–587. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chong J, Wishart DS, Xia J. Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for comprehensive and integrative metabolomics data analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinforma. 2019;68:e86. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bektas A, Schurman SH, Sen R, Ferrucci L. Human T cell immunosenescence and inflammation in aging. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102:988. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RI0716-335R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niwa A, et al. Interleukin-6, MCP-1, IP-10, and MIG are sequentially expressed in cerebrospinal fluid after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:217. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0675-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clement J, Wong M, Poljak A, Sachdev P, Braidy N. The Plasma NAD + Metabolome Is Dysregulated in “normal” Aging. Rejuvenation Res. 2019;22:121–130. doi: 10.1089/rej.2018.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ursini F, Maiorino M, Forman HJ. Redox homeostasis: The Golden Mean of healthy living. Redox Biol. 2016;8:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao W, Wang RS, Handy DE, Loscalzo J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox couples and cellular energy metabolism. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;28:251–272. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrard J, et al. Metabolic view on human healthspan: A lipidome-wide association study. Metabolites. 2021;11:287. doi: 10.3390/metabo11050287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones AE, Murphy JL, Stolinski M, Wootton SA. The effect of age and gender on the metabolic disposal of [1-13C]palmitic acid. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:22–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korbecki J, Bajdak-Rusinek K. The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: an overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm Res. 2019;68:915–932. doi: 10.1007/s00011-019-01273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JY, Cho HK, Kwon YH. Palmitate induces insulin resistance without significant intracellular triglyceride accumulation in HepG2 cells. Metabolism. 2010;59:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng G, et al. Oleate blocks palmitate-induced abnormal lipid distribution, endoplasmic reticulum expansion and stress, and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2206–2218. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leamy AK, et al. Enhanced synthesis of saturated phospholipids is associated with ER stress and lipotoxicity in palmitatetreated hepatic cells. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1478–1488. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M050237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciapaite J, et al. Metabolic control of mitochondrial properties by adenine nucleotide translocator determines palmitoyl-CoA effects: Implications for a mechanism linking obesity and type 2 diabetes. FEBS J. 2006;273:5288–5302. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ventura FV, Ruiter J, Ijlst L, Tavares De Almeida I, Wanders RJA. Differential inhibitory effect of long-chain acyl-CoA esters on succinate and glutamate transport into rat liver mitochondria and its possible implications for long-chain fatty acid oxidation defects. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chak CM, et al. Ageing investigation using two-time-point metabolomics data from KORA and CARLA studies. Metabolites. 2019;9:44. doi: 10.3390/metabo9030044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kris-Etherton PM, et al. Dietary stearic acid and risk of cardiovascular disease: Intake, sources, digestion, and absorption. Lipids. 2005;40:1193–1200. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1485-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kühn T, et al. Higher plasma levels of lysophosphatidylcholine 18:0 are related to a lower risk of common cancers in a prospective metabolomics study. BMC Med. 2016;14:13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0552-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senyilmaz-Tiebe D, et al. Dietary stearic acid regulates mitochondria in vivo in humans. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05614-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tarasenko TN, Cusmano-Ozog K, McGuire PJ. Tissue acylcarnitine status in a mouse model of mitochondrial β-oxidation deficiency during metabolic decompensation due to influenza virus infection. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;125:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seiler SE, et al. Carnitine acetyltransferase mitigates metabolic inertia and muscle fatigue during exercise. Cell Metab. 2015;22:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jung S, et al. Age-related increase in alanine aminotransferase correlates with elevated levels of plasma amino acids, decanoylcarnitine, lp-pla2 activity, oxidative stress, and arterial stiffness. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:3467–3475. doi: 10.1021/pr500422z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darst BF, Koscik RL, Hogan KJ, Johnson SC, Engelman CD. Longitudinal plasma metabolomics of aging and sex. Aging (Albany. NY) 2019;11:1262–1282. doi: 10.18632/aging.101837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tserng KY, Jin SJ. Metabolic origin of urinary 3-Hydroxy dicarboxylic acids. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2508–2514. doi: 10.1021/bi00223a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller-Fleming L, Olin-Sandoval V, Campbell K, Ralser M. Remaining mysteries of molecular biology: the role of polyamines in the cell. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:3389–3406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wendisch VF. Microbial production of amino acid-related compounds. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2016;159:255–269. doi: 10.1007/10_2016_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amin M, et al. Polyamine biomarkers as indicators of human disease. Biomarkers. 2021;26:77–94. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2021.1875506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomes-Trolin C, Nygren I, Aquilonius S-M, Askmark H. Increased red blood cell polyamines in ALS and Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2002;177:515–520. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rhee HJ, Kim E-J, Lee JK. Physiological polyamines: simple primordial stress molecules. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:685–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Das KC, Misra HP. Hydroxyl radical scavenging and singlet oxygen quenching properties of polyamines. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;262:127–133. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000038227.91813.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta VK, et al. Restoring polyamines protects from age-induced memory impairment in an autophagy-dependent manner. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1453–1460. doi: 10.1038/nn.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eisenberg T, et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1305–1214. doi: 10.1038/ncb1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liao R, et al. Histidine provides long-term neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia through promoting astrocyte migration. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15356. doi: 10.1038/srep15356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adachi N, Liu K, Arai T. Prevention of brain infarction by postischemic administration of histidine in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1039:220–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rama Rao KV, Reddy PVB, Tong X, Norenberg MD. Brain edema in acute liver failure. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1400–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Myint T. Urinary 1-Methylhistidine is a marker of meat consumption in black and in white California Seventh-day Adventists. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:752–755. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raithel M, et al. Excretion of urinary histamine and N-tele methylhistamine in patients with gastrointestinal food allergy compared to non-allergic controls during an unrestricted diet and a hypoallergenic diet. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:41. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thelestam M, Curvall M, Enzell CR. Effect of tobacco smoke compounds on the plasma membrane of cultured human lung fibroblasts. Toxicology. 1980;15:203–217. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(80)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bessonneau V, et al. Gaussian graphical modeling of the serum exposome and metabolome reveals interactions between environmental chemicals and endogenous metabolites. Sci Rep. 2021;11:7607. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87070-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pelley JW. Fatty acid and triglyceride metabolism. In: Elsevier’s Integrated Review Biochemistry. Elsevier; 2012. 10.1016/B978-0-323-07446-9.00010-6.

- 68.Sharma V, Ichikawa M, Freeze HH. Mannose metabolism: More than meets the eye. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;453:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu YJ, et al. Glycine promotes longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans in a methionine cycle-dependent fashion. PLOS Genet. 2019;15:e1007633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Plummer JD, Johnson JE. Extension of cellular lifespan by methionine restriction involves alterations in central carbon metabolism and is Mitophagy-Dependent. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:301. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canfield C-A, Bradshaw PC. Amino acids in the regulation of aging and aging-related diseases. Transl Med Aging. 2019;3:70–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tma.2019.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wishart DS, et al. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D608–D617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma Y, et al. Anti-inflammation effects and potential mechanism of Saikosaponins by regulating nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism and arachidonic acid metabolism. Inflammation. 2016;39:1453–1461. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosa FT, Freitas EC, Deminice R, Jordão AA, Marchini JS. Oxidative stress and inflammation in obesity after taurine supplementation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kerner J, Hoppel CL. Carnitine and β-Oxidation. In: Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry. Elsevier; 2013. 10.1016/B978-0-12-378630-2.00099-2.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.