Abstract

Aim

Nursing competencies are crucial indicators for providing quality and safe care. The lack of international agreement in this field has caused problems in the generalization and application of findings. The purpose of this review is to identify the core competencies necessary for undergraduate nursing students to enter nursing work.

Data Sources

We conducted a structured search using Scopus, MEDLINE (PubMed), Science Direct, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Review Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the methodology recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute, supported by the PAGER framework, and guided by the PRISMA‐ScR Checklist. Inclusion criteria included full‐text articles in English, quantitative and qualitative research related to competencies for undergraduate students or newly graduated nurses, competency assessment, and tool development from 1970 to 2022. We excluded articles related to specific nursing roles, specific contexts, Master's and Ph.D. curricula, hospital work environment competencies, and editorial.

Results

Out of 15,875 articles, we selected 43 studies, and data analysis with summative content analysis identified five themes named individualized care, professional nursing process, nursing administration, readiness, and professional development.

Conclusion

Considering the dynamics of competencies and their change with time, experience, and setting, it is necessary to update, localize, and levelling of the proposed competencies based on the culture of each country.

Impact

These competencies provide a guide for undergraduate nursing curriculum development and offer a framework for both clinical instruction and the evaluation of nursing students.

Keywords: clinical competence, curriculum, education, graduate, nursing, professional competence

1. INTRODUCTION

Today, ensuring the quality and safety of nursing care is a fundamental aspect of the healthcare system worldwide (Ambrosio‐Mawhirter & Criscitelli, 2018). Meanwhile, Newly Graduated Registered Nurses (NGRNs) are recognized as a crucial professional group that influences the health of future populations (McCarthy et al., 2020). As a result, they are considered a primary target for nursing research due to the significant educational needs required to bridge the gap between nursing theories and practices (Wakefield, 2018).

At the beginning of the 21st century, nursing faced the challenge of dealing with the complexity of healthcare (Keshk & Mersal, 2017). The ever‐increasing demand for quality and safe nursing practice has caused many nursing curricula to fail to respond to changing needs. This demand has been further compounded by the emergence of new educational technologies and the gap between theory and clinical practice (Salem et al., 2018). Additionally, newly graduated nurses face difficulties during their transition into practice (Lee & Sim, 2020), which further exacerbates the situation (Salem et al., 2018). However, concerns persist about clinical preparedness and about encountering a transition shock among nursing graduates (Duchscher & Windey, 2018), which can reduce the quality of nursing care and endanger patient safety (Lyle‐Edrosolo & Waxman, 2016). While the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Institute of Medicine (IOM) emphasize the need for all nursing students to achieve clinical competencies as the golden standards of nursing and consider theoretical and clinical competence as the future of nursing (Davis et al., 2021; World Health Organization, 2020). Therefore, the issue of nursing competence has become more critical as the heart of the nursing curriculum in response to these increasing demands (Attallah & Hasan, 2022).

According to the definition of the World Health Organization (2015), competencies refer to a set of knowledge, skills, and behaviours that are necessary to successfully perform jobs, roles, or responsibilities. Nursing competencies, in the meantime, are vital indicators of performance and a standard measure of the ability to perform nursing tasks at a professional level (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2021; Lee et al., 2017). Identifying these competencies will improve patient experiences, reduce costs, ensure health outcomes and professional development, improve the quality of care needs, increase patient satisfaction (Attallah & Hasan, 2022), increase job security (Sonoda et al., 2017), and not paying attention to them, will cause a theory‐practice gap, burnout, a decrease in satisfaction and even leave the job abandonment (Mellor & Greenhill, 2014).

Because the roles, work environment, educational preparation, and legal and regulatory status of nurses are different, the national nursing boards of some countries have published and reviewed requirements for the development of national competency competencies for registered nurses (Black et al., 2008). In Australia and Canada, researchers published some other skills as competency requirements for newly graduated nurses (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Mallory et al., 2003). The provision of the competencies aims to clearly state exactly what registered nurses must achieve before being registered with the nursing board and that they need to maintain these competencies throughout their careers to protect the public and ensure the quality and safety of nursing practice (Kukkonen et al., 2020).

The studies conducted in this field showed that, although considerable time and effort have been spent on defining and developing nursing competencies in many countries, it is still in its early stages and little is known about its use in nursing practice (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Jokiniemi et al., 2018). In addition, despite the increasing number of publications related to competence, few studies have explored competency in a global context. However, the complexity, multi‐dimensionality, dynamics, and change with time, experience, and setting (Attallah & Hasan, 2022) and lack of agreement on competence domains have caused problems in the generalization and application of the finding (Harrison et al., 2020). Therefore, there is a need for more international cooperation to reach an agreement on a clear definition and determine its dimensions (Lee et al., 2021). Integrating the results of studies conducted in this field will help nursing managers use a higher level of evidence to select the necessary competencies for nursing students. Therefore, the purpose of this review is to identify the core competencies necessary for undergraduate nursing students to enter nursing work.

2. BACKGROUND

Since 1970, researchers have developed the concept of competence by linking it with recent psychology. McClelland, the prominent Harvard psychologist, rejected the traditional training programmes and proposed the competency‐based approach as an important tool in evaluating the performance of employees and human resources planning (Patterson et al., 2000). In 2009, the WHO published a report on nursing education to define competency requirements and global standards for the initial education of nurses (World Health Organization, 2009). Similarly, the ICN (2006) has globally highlighted the importance of continuing to develop nursing competence as a professional responsibility. According to this report, the standard of nursing work performance and the successful application of knowledge, skill, and judgement define competencies. With the emergence of this approach, most countries developed nursing curricula based on expected competencies in line with their culture and nursing needs (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Lee et al., 2017). Based on this, the National Association of School Nurses (NASN) (2016) defined four domains of leadership, care coordination, community health, and quality improvement as core competencies for the 21st century.

Both WHO (2009) and ICN (2006) independently set competencies as the gold standards of nursing while determining the core competencies for all nurses, introducing the validity of the nursing profession. However, there is no international agreement on the set of competencies required by nursing students, and there is a difference between the expected level, and the self‐perceived competency level (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Burns & Poster, 2008). Although the ICN has specified competencies, and some of these competencies are taught in nursing curricula, they have not been able to cover the changing needs of nursing (Brown & Crookes, 2016). The synthesis of existing literature related to the core competencies of nursing students may help identify and clarify known issues and guide future research and clinical practice.

3. AIM

This review aimed to identify the core competencies necessary for undergraduate nursing students to enter nursing work.

4. METHOD

4.1. Study design

The methodological steps suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (Peters et al., 2020), guided by the PAGER (Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence for Practice, and Research Recommendations) framework to improve the quality of reporting (Bradbury‐Jones & Aveyard, 2021), and reported according to the PRISMA‐ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist (Data S1). A scoping review is an appropriate way to identify research gaps, make recommendations for further research, determine the range of available evidence, and finally bundle and communicate research results (Peters et al., 2020). Another reason for this decision was that scoping reviews allow the inclusion of all levels and types of evidence.

4.2. Research question

A Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework, which will guide the database searches and eligibility criteria, informs the research questions (Table 1). The main research question is: What are the core competencies necessary for undergraduate nursing students to enter nursing work, and what can reasonably be expected from them?

TABLE 1.

Population, concept, and context framework informing research question and search strategy.

| PCC protocol | Review question components |

|---|---|

| Population | Graduating nursing students/Newly graduated nurses |

| Concept | The nursing core competencies |

| Context | Educational or clinical settings in any geographical location |

4.3. Search strategy

To aid in the identification of relevant articles and the exclusion of irrelevant articles, we first stipulated PCC criteria for inclusion (Peters et al., 2020). We searched Web of Science, MEDLINE via Pub Med, Scopus, Science Direct, CINAHL, and Google Scholar, supplemented by web searching via Google. We conducted the search strategy for 7 months to improve its effectiveness (from July 2021 to February 2022). We selected articles published from 1970 (the development of the concept of competence) to 2022/02/22. We identified the keywords based on previous research and with the consultation of the research team: nurs*, “students nursing” AND competenc*, “professional competenc*”, “clinical competenc*”, preparedness, readiness, efficacy, “expected competenc*”, AND novice, registration, entry‐level, preregistration, “newly graduated”, graduating, undergraduate curriculum, baccalaureate programme, and different combinations of the above words. We first conducted a limited search in the Web of Science to identify keywords and thesaurus search and brainstorming in the working group. Then we searched all relevant data sources using the identified keywords and index terms. Finally, one reviewer developed and another reviewed the screening of the available reference list of additional studies of the search strategy.

4.4. Study selection

We considered studies eligible if they met the criteria in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Inclusion criteria and Exclusion criteria.

| PCC element | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

Literature related to roles/competencies; Nurse managers, preceptors, advanced nursing practitioners, specialists, nursing educators |

| Concept | The core competencies/or general competencies that are necessary for newly graduated nurses/graduating nursing students of bachelor's degree and can reasonably be expected from them | Particular nursing competencies (e.g., medication, clinical skills, or cultural competency) |

| Context | Educational or clinical settings in any geographical location | Specific contexts such as; emergency department, paediatric, intensive care units. |

| Study design | Literature on the context was nursing competencies for the last year of nursing education or the first year of registration:

|

|

4.5. Data charting process

We used an adapted version of the data charting form as recommended by Peters et al. (2020). Since data charting is an iterative process, we developed the form further in the team, pretested it with three exemplary studies, and adopted it. A single researcher (MP) carried out data charting and extraction, and another researcher (VZ) double‐checked it. Two other researchers (AG, and LV) reviewed the data charting form to ensure accuracy (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Information of the selected studies (N = 43).

| Authors, year | Type of evidence Source | Context (federal state Of Germany; Discharging/Admitting setting) | Objective/aim | Design, population, and sample size | Data collection methods | Results/key findings | Limitations | Core competencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torres‐Alzate et al. (2020) | Journal publication | Nursing college, hospitals, USA | The consensus among experts on global health competencies for baccalaureate nursing students | Mixed method study, Global nurse expert, nurse educator (n = 41) | Literature review, websites, emails, LinkedIn, expert interviews, and standardized questionnaires | The competencies derived in this study can be used as a framework for clinical education and evaluation of nursing students' experiences | Low sample size | Understanding of the burden of disease, health implications of crises, social and environmental determinants of health, global nursing and health care, culturally competence, humanistic and holistic care, collaboration and partnerships, communication, leadership, management, and advocacy, ethical issues, equity, and social justice in global health |

| Andrew et al. (2008) | Journal publication | Three metropolitan public hospitals, Australian | Examine the psychometric properties of the ANCI 2000 national competency standards for new graduate nurses | Quantitative study, new graduates nurse (n = 116); Responserate: 77.3% | Standardized questionnaires | There were inconsistencies in the psychometric properties of the assessment tool | Low sample size and mere use of newly graduated nurses | Professional and ethical practice, critical thinking and analysis, management of care, enabling |

| Attallah and Hasan (2022) | Journal publication | Nursing colleges, hospitals, Saudi Arabia | Formulate and validate of competence framework for undergraduate nursing students | Qualitative study, Academic and clinical experienced nurses (n = 10) | Group discussion, and Delphi technique | The dimensions, characteristics, and presentation of the competency‐based model are essential for the nursing profession | Low sample size, and generalizability of findings | Person‐centred care, quality care and patient safety, evidence‐based practice, professionalism and leadership, communication and teamwork, informatics and technology, and system‐based practice |

| Berkow et al. (2008) | Journal publication | Hospitals, nursing schools, USA | Assessing new graduate nurse performance | Cross‐sectional study, new graduates' proficiency (n = 5700), Frontline clinical leaders (n = 53,000); Responserate: 11% | Standardized questionnaires | About 25% of nurse leaders were fully satisfied with the new graduate's performance, whereas more than a quarter were somewhat dissatisfied or worse | Lack of distinction between the concepts of (proficiency, performance, and preparedness) | Technical skills, communication, critical thinking, clinical knowledge, and management of responsibilities |

| Black et al. (2008) | Collaborative project (Journal publication) | N/A, Canada | Competencies in the Context of entry‐level registered nurse practice | Qualitative study, Professional nursing (n = 10) | Tele conferences, Electronic Data Collection(e‐mail), small group, and face‐to‐face meetings | 119 competency statements are identified for entry‐level registered nurse practice | N/A | Professional responsibility and accountability, knowledge‐based practice, ethical practice, service to the public, and self‐regulation |

| Blažun et al. (2015) | Journal publication | The faculty of health sciences, University of Maribor, Slovenia | Students' views on competencies | Quantitative study, Graduating nursing students (n = 69); Response rate: 51.9% | Standardized questionnaires | The nursing curriculum should be more future‐oriented and needs some core changes regarding the scope and level of competencies taught | Low sample size, the mere use of clinical nursing graduates | Professional values, nursing practice and clinical decision‐making, nursing skills, nursing interventions, knowledge and cognitive competencies, communication and interpersonal competencies, leadership, management, and team competencies |

| Brown and Crookes (2016) | Journal publication | Nursing schools, Australia | Identifying the skills needed by newly graduated nursing students | Qualitative study, Nursing population, academics, managers (n = 589); Responserate:90.54% | Standardized questionnaires, Electronic Data Collection (e‐mail), and Delphi technique | All the competencies of the study tool are necessary for the newly graduated nurse and differ only in priority | Low sample size and bias of participants' selection | Communication and documentation, privacy and dignity, professional nursing behaviours, clinical skills, teamwork and multidisciplinary team working, planning of nursing care, personal care, knowledge of key nursing implications, cultural competence, clinical intervention, preventing risk and promoting safety, clinical monitoring and management, therapeutic nursing behaviours/respectful of personal space, critical analysis, and reflective thinking, dealing with people, learning skills/evidence‐based practitioner, promotes self‐care, mental health nursing care, coordinating skills, understanding the roles of nursing, technology and informatics, teaching/educator skills, acts as a resource, case manager, supervisory and leadership skills |

| Candelaria (2010) | Journal publication | USA | Perceptions of recent nurse graduates on educational preparation for working | Descriptive study, Graduate nurses (n = 352); Responserate:12% | Standardized questionnaires | An accelerated nursing curriculum increases job readiness and nursing competencies boost self‐confidence | Low Sample size | Job preparation, management, and leadership, communication and information technology, documentation skills, critical thinking, problem‐ solving and decision‐making, organizational skills, practice knowledge, physical assessment, role modelling, evaluation strategies, helping |

| Lin et al. (2016) | Journal publication | A university in southern Taiwan | Perceptions of core values of nursing in Taiwanese nursing students at the baccalaureate level | Qualitative study, Graduate nurses (n = 109) | Electronic Data Collection (e‐mail), and group discussion | The core values of nursing enhance understanding and may be used as a guide to increasing clinical nursing competence in healthcare | Lack of transferability of study findings and the possibility of participants misunderstanding the core values of nursing | Critical thinking and reasoning, clinical skills and basic biomedical science, communication, and teamwork, caring, ethics, accountability, lifelong learning |

| Clark and Holmes (2007) | Journal publication | National hospitals, south of England | Competence of NGNs and the factors influencing their development once they enter the real world | Qualitative exploratory study, Nursing preceptors, and newly graduated nursing students (n = 105) | Focus groups and individual interviews | Compared to the new nurses, ward managers have little low expectations, so appropriate support for students to develop knowledge, skills, confidence, and independent practice is essential | Impact and interaction between participants and change of views, and generalizability of findings | Ready for practice, confidence, staff development, core and specialist skills, holistic care, and the role of preceptorship |

| Cowan et al. (2008) | Journal publication | Nursing schools, London | Develop and test a nurse competence self‐assessment questionnaire | Mixed‐method study, post‐registration nurses in five countries (n = 588); Response rate: 40% | Standardized questionnaires | The assessment tool has an acceptable degree of reliability, construct, and content validity | Clinical and nursing competencies complexity | Assessment, care delivery, health promotion, communication, personal and professional development, professional and ethical practice, research and development, and team working |

| Harrison et al. (2020) | Journal publication | Four acute healthcare organizations in one Australian state | How healthcare providers define and determine graduate nurse practice readiness | Qualitative study, Nurses (n = 67) | Semi‐structured interview, focus group, Electronic Data Collection (e‐mail, electronic flyer) | Practice readiness is a multidimensional concept encompassing overlapping personal, clinical, industry, and professional capabilities | Possibility of no transferability at the international level | Clinical readiness, professional readiness, industry readiness, personal readiness, positive attitude, and psychosocial skill |

| Hartigan et al. (2010) | Journal publication | Three University teaching hospitals, Ireland | Identify clinically challenging episodes for nursing students and describe the competencies required to manage them | Qualitative descriptive study, Nursing preceptors (n = 28) | Focus group discussion, and field notes | The findings of the study identified the expected competencies and challenges in newly graduated nursing students | Lack of international agreement on the professional competencies and expectations of newly graduated nurses | Patient assessment, clinical decision‐making, technical and clinical skills, interactions, and communications |

| Hsu and Hsieh (2013) | Journal publication | Colleges of Nursing (North and South Taiwan) | Develop and test psychometric competency to measure learning outcomes of baccalaureate nursing students | Mixed method study, Graduate students, and expert panel (n = 622); Response rate: 94.87%. | Standardized questionnaires | The assessment tool had satisfactory psychometric properties and can be a useful tool for assessing the learning outcomes of nursing students | Limitations on the generalizability of study findings | Ethics and accountability, general clinical skills, lifelong learning, clinical biomedical science, caring, critical thinking, and reasoning |

| Jacob et al. (2014) | Journal publication | Nursing colleges, hospitals, Australia | Exploring recipients' perceptions of NGNs' clinical judgement abilities | Qualitative study, Nurses, administrators & educators (n = 155) | Semi‐structured interview | The role of RNs and ENs graduates varies due to differences in education, responsibility, and skill levels | Differences between levels of registered nurses, and low generalizability of findings | Educational competency, responsibility, and skill competency |

| Kennedy et al. (2015) | Journal publication | Nursing schools, Canada | Development, psychometric assessment of the nursing competence self‐efficacy scale | Mixed method study, Nursing experts panels (n = 260); Responserate:84% | Standardized questionnaires | Assessment tools can increase students' self‐efficacy in evaluating clinical interventions | The presence of a faculty member with the students and the impact on social desirability, using self‐efficacy instead of nursing competencies | Proficiency, altruism, prevention, and leadership |

| Keshk and Mersal (2017) | Journal publication |

Five training hospitals of nursing Qassim University, Saudi Arabia: King Saud Hospital (KSH), King Fahd Hospital (KFSH), Maternal and Child Hospital (MCH), Prince Sultan Cardiac Care (PSCC), Burdiah Center Hospital (BCH) |

Expectations of nursing managers and faculty members for entry‐level graduate nurses | Comparative exploratory study, Faculty members, nurse managers (n = 94) | Standardized questionnaires | There was a statistically significant strong positive correlation between specific nursing skills, attributes and characteristics of nursing practice, and practical expectations of stakeholders and faculty members | N/A | Sound clinical decisions, knowledge and safe administration of medications, safety practices, patient advocating, identifying patient needs and interventions, documenting effectively and accurately, organizing and prioritizing, performing skills/confidently, communicating with physicians, and delegation skills |

| Kukkonen et al. (2020) | Journal publication | Hospitals, Finland | Nurse managers' perception of NGNs' competence and connected factors | Review article, Research publications (n = 12) | Literature search based on Arksey and O'Malley (2005) methodological framework | There is no consensus on the perception and evaluation of nursing managers about the competence of newly graduated nurses | Limited knowledge and understanding of nursing competencies |

Rafferty And Lindell (2011), USA * : Leadership, critical thinking, teaching/collaboration, planning/evaluation, interpersonal relations/ communication, and professional development Thomas et al. (2011), USA: Patient‐centred care, interdisciplinary teams, quality improvement, and information management, EBP King et al. (2003): Critical thinking, client relationships, teamwork, knowledge of cultural diversity, responsibility/accountability, cost‐effective care, coordinating care, computer information, delegating, initiating referrals, interdisciplinary teams, patient assessment, plan of care, patient care outcomes evaluation, assess patient learning needs, implement and evaluate teaching plans, health lifestyle, apply research, quality improvement, monitoring processes, involve patient's families and/or significant others in decisions, continue self‐development, implement care using critical pathways, and safely administer iv Lee et al. ( 2002 ): Assessment and measurement, treatment, and clinical skills Nickel et al. ( 1995 ): Individual competencies, group competencies, and community competencies Joyce‐Nagata et al. ( 1989 ): Ethical, knowledge base of the humanities and the biopsychosocial sciences, utilization of nursing process, maintenance and/or restoration, nursing practice, accountability, collaboration, ongoing appraisal, and definition of nursing |

| Ko and Yu (2019) | Journal publication | General hospitals in Seoul and Jeolla‐do, South Korea | Develop and evaluate a competency assessment tool for nurse graduates of KABONE | Systematic review study, Nurse, managers, professors (n = 161); Response rate: %96.5 | Literature review, and Standardized questionnaires | The study tool had good validity and reliability and could be used as a basic framework for evaluating the competencies of nursing students in Korea | Non‐random sampling and need to confirm the construct validity of the instrument | Critical thinking and application of the nursing process, self‐management, coordination, and collaboration, patient care, ensuring quality, communication |

| Lee et al. (2017) | Journal publication | Seoul or Gyeonggi‐based secondary hospitals and tertiary hospitals | Develop and evaluate a Korean nurses' core competency scale | Mixed method study, newly graduated nurses (n = 528); Responserate:85.8% | Literature review, expert panel, and Standardized questionnaires | The study scale showed good reliability and validity and can be used to develop and evaluate the core competencies of Korean nurses | Low internal consistency | Human understanding and communication skills, professional attitudes, critical thinking and evaluation, general clinical performance, and specific clinical performance |

| Lee et al. (2021) | Journal publication | Nursing schools, South Korea | Psychometric evaluation of the Korean version of the work readiness scale for graduating nursing students | Cross‐sectional study, Graduating nursing students (n = 251) | Standardized questionnaires | The study tool had good reliability and validity and can be used to evaluate the readiness to enter the profession of Korean nursing undergraduate students | Failure to employ a certified translator in the translation process, use of an acceptable minimum number of participants, and low generalizability of findings | Work competence, social intelligence, organizational acumen, and personal work characteristics |

| Lin et al. (2017) | Journal publication | Nursing College, Taiwan | Developing and validating nursing students' competence instrument | Exploratory study, Graduating nursing students, and expert panel (n = 214); Response rate:52% | Standardized questionnaires | The scale of the study demonstrates an acceptable level of validity and reliability and could be used to evaluate the competencies of Thai nursing graduates | Limitations on the generalizability of the findings, and consideration of the same level of nursing students' perception of the core values of nursing | Integrating care abilities, leading humanity concerns, advancing career talents, and dealing with tension |

| Liou and Cheng (2014) | Journal publication | School of Nursing, Chang Gung at Chiayi Campus, Taiwan | Develop and test the psychometric properties of the clinical competence questionnaire of upcoming baccalaureate nursing graduates | Mixed method study, Graduating nursing students (n = 340); Response rate: 96% | Standardized questionnaires, expert panel, and focus group | The study tool can be a useful tool for assessing the perceived clinical competency of nursing graduates due to its good reliability and validity, as well as its ease of use | Lack of generalization of study findings, no fit for evaluating competency‐based performance | Nursing professional behaviours, general performance, core nursing skills, and advanced nursing skills |

| Ličen and Plazar (2015) | Journal publication | Databases search, Slovenia | Identify and evaluate the best available research evidence related to the assessment of clinical competence in nursing education | Meta‐analyses study, Research publications (n = 7) | PRISMA checklist 2009 | There are various tools for assessing nursing competencies. at the national and global levels, it is necessary to develop a comprehensive tool for assessing nursing competencies | Lack of one definition for core nursing competencies |

Lee‐Hsieh et al. ( 2003 ): Caring, communication/coordination, management/teaching professional self‐growth competence O'Connor et al. ( 2009 ): Professional and ethical practice, holistic approaches to care, interpersonal relationships, care, personal and professional development Hsu and Hsieh ( 2009 ): Critical thinking and reasoning, general clinical skills, basic biomedical science, communication, and team‐work, caring, ethics, accountability, and lifelong learning attitude Klein and Fowles ( 2009 ): Leadership, critical care, teaching/collaboration, planning/evaluation, interpersonal relations/communication, and professional development Lauder et al. ( 2008 ): Leadership, professional, development, assessment, planning, intervention, cognitive ability, social participation, ego strength, research awareness, and policy awareness |

| Liu et al. (2021) | Journal publication | Nursing colleges, hospital, Dalian, China | Develop the evaluation indicators and achieve experts' consensus on bachelor nursing students' quality and safety competencies at their graduation | Qualitative study, Nursing educational experts (n = 22); Response rate: 92.43% | Literature review, semi‐structured interview, Delphi technique | Six themes and 88 indicators were identified as criteria for evaluating nursing competencies | Lack of transferability of study findings | Patient‐centred care, collaboration, and teamwork, evidence‐based practice, continuous quality improvement, safety, and informatics |

| Lofmark et al. (2006) | Journal publication | Hospitals, Sweden | Compare opinions of final‐year nursing students and rate their competence | Descriptive study, Nursing students' supervisors (n = 242); Response rate: 75.5% | Standardized questionnaire | Newly graduated nurses were more competent than nurses with less recent education | Use only final‐semester nursing students and experienced nurses | Communication, patient care, personal characteristics, and knowledge utilization |

| Mallory et al. (2003) | Journal publication | College of nursing faculty from a Midwestern public university, USA | Describe practicing nurses' perceptions of new graduate ideal qualities | Qualitative study, Nurses (n = 44) | Focus group and individual interviews | Nurses introduced 7 competencies as ideal attributes for newly graduate nursing students | Considering nurses' perceptions only to identify the ideals of a new nursing graduate | Ability to prioritize, decision‐making, problem‐solving, time management and physical assessment, continuous learning, connect with people, accountability, adaptability, positive attitudes, and nursing process |

| Meretoja et al. (2004) | Journal publication | Major Finnish University hospital | Develop and test the nurse competence scale (NCS) | Mixed method study, Nurses (n = 498); Response rate: 86.5% | Standardized questionnaires, expert groups, and literature review | The assessment tool was useful to indicate the different levels of competence of nurses | Limitations in sampling and the need for further studies | Helping role, teaching–coaching, diagnostic functions, managing situations, therapeutic interventions, ensuring quality, and work role |

| Mirza et al. (2019)) | Journal publication | Nursing college, hospitals, Canada | How new graduates can meet employer requirements, ‘practice readiness | Systematic review study, Research publications (n = 15) | Standardized checklist | The findings highlighted the technicalities of the nursing role of practice readiness but overlooked the human characteristics essential for providing quality care | Lack of attention to patient experience and humanistic characteristics | Provision of safe care, confidence, transitioning into a nursing role |

| Nilsson et al. (2014) | Journal publication | Higher educational institutions, Sweden | Develop and validate a new tool for measuring self‐reported professional competence | Mixed method study, newly graduated nurse students, educators (n = 1125); Response rate:77% | Standardized questionnaires | The scale can be used to evaluate the outcome of nursing education programmes and the nurses' competencies | Internal attrition rate | Nursing care, value‐based nursing care, medical technical care, teaching/learning and support, documentation and information technology, legislation in nursing and safety planning, leadership in and development of nursing, education, and supervision of staff/students |

| Ossenberg et al. (2016) | Journal publication | Tertiary health care facility, Australia | Advancing the assessment properties of the Australian nursing standards | Mixed method study, Undergraduate nursing student, clinical assessor nurse (n = 243); Response rate:88% | Standardized questionnaires | The study tool had good validity and reliability and high internal consistency. | Pilot nature of the study and low generalizability | Professional practice, critical thinking, and analysis, provision and coordination of care, collaborative and therapeutic practice |

| Perng and Watson (2013) | Journal publication | Christian hospital, Taiwan | Develop the nursing students' core competencies scale in Taiwan | Mixed method study, 545 Nursing instructors (n = 545); Response rate:72.7% | Standardized questionnaires | The assessment scale can be used in education, research, evaluation of nursing competencies, and curriculum design | N/A | Critical thinking and reasoning, general clinical skills, basic biomedical science, communication, and teamwork capability, caring, ethics, accountability, and lifelong learning |

| Poster et al. (2005) | Collaborative project (Journal publication) | Nursing schools, Texas | Identify different competencies from the licensed vocational nurses to the doctoral prepared in Texas | Qualitative study, Nursing programme (n = 82), Nursing documents (n = 1990) | Standardized checklist | The expected entry‐level competencies for the Bachelor of Nursing programme were identified and differentiated | N/A | Provider of care, coordinator of care, member of a profession |

| Prion et al. (2015) | Journal publication | Nursing schools, California | Development and validation of performance tools for new nursing graduates based on QSEN competencies | Mixed method study, Nursing educators (n = 92) | Standardized questionnaires | The assessment scale had good internal consistency and was able to successfully evaluate and discriminated the nursing students' competencies | Not mentioning the details of the participants' experiences | Patient‐centred care, safety, evidence‐based practice, teamwork, and collaboration |

| Ramritu and Barnard (2001) | Journal publication | Two paediatrics metropolitan hospitals in Australia | New nurse graduates' understanding of competence | Qualitative study, new graduates (n = 6) | Semi‐structured interview | The competence of a new graduate evolves with experience and the global or referential meaning of competence is a safe practice | Use of newly graduated nurses with three months of care setting experience | Safe practice, management of time and workload, accessing and utilizing resources, limited independence, knowledge, performance, and clinical skills, ethical practice, and competence as evolving |

| Satu et al. (2013) | Journal publication | Databases search, Finland | Exploring competence areas for nursing students in the EU | Qualitative study, Research publications (n = 7) | Standardized checklist | The identified common competencies can be a solution for nurses' mobility and harmonize nursing education | Limited target study population to European countries | Professional and ethical values and practice, nursing skills and interventions, communication and interpersonal skills, knowledge and cognitive ability, assessment and improving quality of nursing, professional development, leadership, management and teamwork |

| Sedgwick et al. (2014) | Journal publication | Nursing College, southern Alberta, Canada |

Exploring the acquisition of entry‐to‐practice competencies by second‐degree nursing students |

Mixed method study, Graduating students, preceptor, faculty advisor (n = 22); Response rate: 46% | Standardized questionnaires, and focus group | Students, educators, and nursing counsellors ‘perceptions of competency definition were different, and preceptors rated students higher than student ratings | Low respond rate | Professional responsibility and accountability, knowledge‐based practice, a specialized body of knowledge, competent application of knowledge, ongoing comprehensive assessment, health care planning, providing nursing care, evaluation, ethical practice service to the public, and self‐regulation |

| Serafin et al. (2020) | Journal publication | Nursing colleges, hospitals, Poland | Exploring Generation Z newly graduated nurses' competence | Qualitative exploratory study, newly graduated nurses, nurse managers, and clinical nurses (n = 29) | Semi‐structured interview, focus group, field note, and Electronic Data Collection(e‐mail) | Empathy was identified the important competency in the performance of Generation Z nurses | Lack of equivalent data to fully compare the identified features | Knowledge and ability to use it in practice, communication, teamwork, openness to development, decision‐making, coping with stress, assertiveness, and empathy |

| Shaw et al. (2018) | Journal publication | Mount Carmel College of Nursing, Columbus | Preparation for practice in newly licensed registered nurses | Mixed method study, Nursing preceptor, nurse educators panel (n = 107); Response rate: 43% | Standardized questionnaires, and Electronic Data Collection (e‐mail) | The perception of a registered nurse differed from the professional competencies of newly licensed registered nurses | Lack of transportability, and low response rate | Caring/compassionate, collaboration, communication, and being prepared to practice. manage complex situations, time management and prioritization, handling stressful situations, thinking on their feet |

| Takase and Teraoka (2011) | Journal publication | Teaching hospital Hiroshima university, Japan | Measurement of psychometric properties of Japanese registered nurses' competency | Mixed method study, Registered nurses (n = 354); Response rate:59% | Standardized questionnaire | The scale has the potential to assist nurses in correctly evaluating their competence level and identifying their educational needs | Not focusing on new graduates | Staff education and management, ethically‐oriented practice, general aptitude, nursing care in a team, professional development |

| Tommasini et al. (2017) | Journal publication |

Eight nursing programmes in seven countries (Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Norway, Poland, Portugal, and Italy) |

Advanced knowledge of competence assessment processes and instruments adopted for Nursing Students across countries | Quantitative study, Bachelor of nursing science programmes from seven countries (n = 8) | Standardized questionnaires | To evaluate the nursing competency process, the expected role of the student's role, cultural adaptation, and the applicability of the competency assessment tool is essential | Probability of selection bias | Technical skills, self‐learning, and critical thinking, nursing care process, ethical behaviour, patient/family communication, risk prevention, self‐adaptation, inter‐professional skills, managing nursing care, clinical documentation, patient/family education, theory & practice integration |

| Utley‐Smith (2004) | Journal publication | Medical‐surgical hospitals, Carolina | Manager's perceptions of the importance of competencies of recent graduates | Quantitative study, Nurse administrators (n = 363); Response rate: %36 | Standardized questionnaires | The Finding of the study revealed the competency structure of six simple factors and their significant difference in the work setting | Focused on clinical practice competency, not including professionalism and ethics | Health promotion, supervision, interpersonal communication, direct care, computer technology |

| Yang et al. (2013) | Journal publication | Teaching hospitals and medical universities, Beijing | Develop a psychometrically sound instrument for measuring the core competencies of Chinese nursing graduates | Descriptive study, Nursing faculty members, and nurses (n = 784); Responserate:79% | Standard checklist, Semi‐structured interviews, focus group, Delphi | The study tool had sound validity and reliability and could be used to develop competency‐based nursing curricula in China | Limitations of generalizability of Findings and the Possibility of selective bias | Professionalism, direct care, support and communication, application of professional knowledge, personal traits, critical thinking, and innovation |

4.6. Summarizing the evidence

We used the PAGER framework to provide a comprehensive description and critique of the literature included in this scoping review by employing the PAGER framework (Bradbury‐Jones & Aveyard, 2021). We collected, summarized, and reported the results in five aspects: (i) PATTERNS; (ii) Advances; (iii) Gaps; (iv) Evidence for practice; and (v) Research recommendations. We structured key themes as patterns according to the research question. We provided contextualized evidence for practice and research recommendations based on the information about patterns, advances, and gaps (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

PAGER Framework.

| Pattern | Advances | Gaps | Evidence for practice | Research recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential core competencies for undergraduate nursing students to enter the actual clinical setting | There is evidence of no international/global agreement on core competencies and their domains for undergraduate nursing students | The need for a comprehensive study to determine the competencies and their domains expected of undergraduate nursing students | These competencies provide a guide for undergraduate nursing curriculum development and offer a framework for both clinical education and evaluation of nursing students | Considering the dynamics of competencies and their change with time, experience, and setting, it is necessary to update, localize, and levelling of the proposed competencies depending on the culture of each country |

4.7. Data analysis

In this step, we used the summative content analysis described by Hsieh and Shannon (2005) to identify, analyse, and describe the content. This approach includes counting and comparing keywords and content, followed by the interpretation of the underlying meaning. We interpreted and sorted keywords based on affinity, forming subcategories and categories. Finally, we counted keywords to show the distribution in categories. We chose this method because the selected competencies mainly consisted of lists of words rather than narrative descriptions (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

The summative content analysis described by Hsieh and Shannon (2005): Identifying and quantifying keywords, interpreted and sorted based on affinity, forming subcategories and categories.

| Categories a N (%) | Subcategories (n) | Sorted based on affinity, and conceptual definition of themes and sub‐themes (references) b |

|---|---|---|

| Individualized care N = 83 (20.70%) | Cultural humility (n = 6) | Cultural competency (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Knowledge of cultural diversity (Kukkonen et al., 2020), Identifying patient needs (Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Kukkonen et al., 2020), Leading humanity concerns (Lin et al., 2017) |

| Value and ethical codes (n = 40) | Privacy and dignity (Brown & Crookes, 2016), Assertiveness and empathy (Serafin et al., 2020), Altruism (Kennedy et al., 2015), Humanistic (Mallory et al., 2003; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Human understanding (Lee et al., 2017), Compassionate (Shaw et al., 2018), Service to the public (Sedgwick et al., 2014; Shaw et al., 2018), Professional values (Blažun et al., 2015; Nilsson et al., 2014), Accountability (Black et al., 2008; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Mallory et al., 2003; Perng & Watson, 2013; Sedgwick et al., 2014), Ethics (Andrew et al., 2008; Black et al., 2008; Cowan et al., 2008; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Mallory et al., 2003; Perng & Watson, 2013; Ramritu & Barnard, 2001; Takase & Teraoka, 2011; Tommasini et al., 2017; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Ethical values (Satu et al., 2013), Equity and social justice (Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Professional nursing responsibility (Black et al., 2008; Jacob et al., 2014; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Sedgwick et al., 2014), Advocacy (Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020) | |

| Holism (n = 7) | Patient‐centred care (Kukkonen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Prion et al., 2015), Holistic approach (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Clark & Holmes, 2007; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020) | |

| Therapeutic communication participatory decision making (n = 30) | Communication (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Berkow et al., 2008; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Cowan et al., 2008; Hartigan et al., 2010; Ko & Yu, 2019; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2017; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Lofmark et al., 2006; Mallory et al., 2003; Perng & Watson, 2013; Serafin et al., 2020; Shaw et al., 2018; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2013), Interpersonal communication (Blažun et al., 2015; Hartigan et al., 2010; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Satu et al., 2013; Utley‐Smith, 2004), Communication with staff, Physicians (Keshk & Mersal, 2017), Communication with patient & family (Kukkonen et al., 2020; Tommasini et al., 2017), Involve patient's families and/or significant others in decisions (Kukkonen et al., 2020), Patient support (Nilsson et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2013) | |

| Evidence‐based nursing care (55) N = 56 (13.96%) | Knowledge Acquisition (n = 18) | Basic biomedical nursing science (Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Perng & Watson, 2013), Nursing/clinical knowledge (Berkow et al., 2008; Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ramritu & Barnard, 2001; Satu et al., 2013; Sedgwick et al., 2014; Serafin et al., 2020), Understanding the roles of nursing (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Mirza et al., 2019), Educational readiness (Jacob et al., 2014), Research awareness (Ličen & Plazar, 2015) |

| Critical appraisal of evidence and implementing of applicable evidence (n = 38) | Critical analysis (Andrew et al., 2008; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Ossenberg et al., 2016), Ability to use knowledge in practice (Lofmark et al., 2006; Serafin et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2013), Theory & practice (Tommasini et al., 2017), Knowledge‐based practice (Black et al., 2008; Sedgwick et al., 2014), Cost effective care (Kukkonen et al., 2020), Ensuring quality (Ko & Yu, 2019; Meretoja et al., 2004), Improving quality of nursing (Kukkonen et al., 2020; Satu et al., 2013), Continuous quality improvement (Liu et al., 2021), Caring (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Cowan et al., 2008; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Ko & Yu, 2019; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Lofmark et al., 2006; Mirza et al., 2019; Nilsson et al., 2014; Perng & Watson, 2013; Poster et al., 2005; Sedgwick et al., 2014; Utley‐Smith, 2004; Yang et al., 2013), Apply research to nursing practice (Kukkonen et al., 2020), Research and development (Cowan et al., 2008), Evidence‐based practice (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Liu et al., 2021; Prion et al., 2015; Sedgwick et al., 2014) | |

| Professional nursing process N = 62 (15.46%) | General critical thinking (n = 5) | Cognitive ability (Blažun et al., 2015; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Satu et al., 2013), Problem solving (Candelaria, 2010; Mallory et al., 2003) |

| Specific critical thinking (n = 27) | Reasoning (Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Perng & Watson, 2013), Innovation (Yang et al., 2013), Making sound clinical decisions (Blažun et al., 2015; Candelaria, 2010; Hartigan et al., 2010; Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Mallory et al., 2003; Serafin et al., 2020), Critical & reflective thinking (Andrew et al., 2008; Berkow et al., 2008; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Ko & Yu, 2019; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2009; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Mallory et al., 2003; Ossenberg et al., 2016; Perng & Watson, 2013; Shaw et al., 2018; Tommasini et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2013) | |

| Professional critical thinking (using the nursing process) (n = 30) |

Utilization of the nursing care process (Ko & Yu, 2019; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Mallory et al., 2003; Tommasini et al., 2017) Assessment (Candelaria, 2010; Cowan et al., 2008; Hartigan et al., 2010; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Mallory et al., 2003; Satu et al., 2013; Sedgwick et al., 2014) Diagnostic functions (Meretoja et al., 2004) Planning (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Sedgwick et al., 2014) Therapeutic interventions (Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Meretoja et al., 2004; Satu et al., 2013; Tommasini et al., 2017) Evaluation (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2009; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Sedgwick et al., 2014) |

|

| Nursing Administration N = 85 (21.20%) | Management & leadership (n = 70) |

Management (Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Satu et al., 2013; Takase & Teraoka, 2011; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020): Care management (Andrew et al., 2008; Tommasini et al., 2017), Management of responsibilities (Berkow et al., 2008), Management of complex situations (Meretoja et al., 2004; Shaw et al., 2018), Time management (Mallory et al., 2003; Ramritu & Barnard, 2001; Shaw et al., 2018), Case management (Brown & Crookes, 2016), Risk &workload management (Tommasini et al., 2017), Utilization of resources (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Ramritu & Barnard, 2001), Ability to prioritization (Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Mallory et al., 2003; Shaw et al., 2018), Clinical monitoring (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Kukkonen et al., 2020), Organization(Keshk & Mersal, 2017), Controlling & Supervision (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Utley‐Smith, 2004), Delegation skills (Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Kukkonen et al., 2020) Leadership (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2015; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Nilsson et al., 2014; Satu et al., 2013; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Teamwork (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Cowan et al., 2008; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2021; Perng & Watson, 2013; Prion et al., 2015; Satu et al., 2013; Serafin et al., 2020; Takase & Teraoka, 2011), Collaboration (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Ko & Yu, 2019; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Liu et al., 2021; Ossenberg et al., 2016; Prion et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2018; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Interdisciplinary/Multidisciplinary team working (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Kukkonen et al., 2020), Coordinator of care (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Ko & Yu, 2019; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Ossenberg et al., 2016; Poster et al., 2005), Partnership (Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020) |

| Informatics & documentation (n = 14) | Informatics and computer technology (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Nilsson et al., 2014; Utley‐Smith, 2004), Clinical document effectively and accurately (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Candelaria, 2010; Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Nilsson et al., 2014; Tommasini et al., 2017) | |

| Work readiness and professional development N = 115 (28.67%) | Personal Characteristics (n = 41) | Member of a profession (Brown & Crookes, 2016), Personal characteristics (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Harrison et al., 2020; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Lofmark et al., 2006; Takase & Teraoka, 2011; Yang et al., 2013), Self‐regulation (Black et al., 2008; Sedgwick et al., 2014), Continue self‐development (Kukkonen et al., 2020), Adaptability and stress management (Lin et al., 2017; Mallory et al., 2003; Serafin et al., 2020; Shaw et al., 2018; Tommasini et al., 2017), Self‐management (Ko & Yu, 2019), Openness to development (Serafin et al., 2020), Enabling (Andrew et al., 2008), Professional self‐growth (Ličen & Plazar, 2015), Professional attitudes (Harrison et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2017), Professional readiness (Harrison et al., 2020; Liou & Cheng, 2014; Mirza et al., 2019), Personal work readiness (Candelaria, 2010; Meretoja et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2015), Professionalism (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Ossenberg et al., 2016; Satu et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013), Personal and professional development (Cowan et al., 2008; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Satu et al., 2013; Takase & Teraoka, 2011), Social participation (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Ličen & Plazar, 2015), Social intelligence (Walker et al., 2015), Social competence(Harrison et al., 2020; Kukkonen et al., 2020) |

| Legality (n = 13) | Legal standards (Nilsson et al., 2014), Organizational readiness (Candelaria, 2010; Harrison et al., 2020; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Walker et al., 2015), Self‐direction learning (Tommasini et al., 2017), Lifelong learning (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Mallory et al., 2003; Nilsson et al., 2014; Perng & Watson, 2013) | |

| Clinical/Procedural skills (n = 24) | Practical skills (Andrew et al., 2008; Berkow et al., 2008; Blažun et al., 2015; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Clark & Holmes, 2007; Cowan et al., 2008; Harrison et al., 2020; Hartigan et al., 2010; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Jacob et al., 2014; Kennedy et al., 2015; Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Ličen & Plazar, 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Liou & Cheng, 2014; Nilsson et al., 2014; Ossenberg et al., 2016; Perng & Watson, 2013; Ramritu & Barnard, 2001; Satu et al., 2013; Shaw et al., 2018; Tommasini et al., 2017) | |

| Safety (n = 9) | Patient safety (Attallah & Hasan, 2022; Brown & Crookes, 2016; Kukkonen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Mirza et al., 2019; Prion et al., 2015), Safety practice (Keshk & Mersal, 2017; Ramritu & Barnard, 2001), Safety planning (Nilsson et al., 2014) | |

| Preventative health services (n = 9) | Prevention risk/Pandemics (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Kennedy et al., 2015; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020; Utley‐Smith, 2004), Health promotion (Cowan et al., 2008; Kukkonen et al., 2020), Self‐care (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Torres‐Alzate et al., 2020), Health maintenance/restoration (Kukkonen et al., 2020) | |

| Mentoring competency (n = 20) |

C. Role modelling: Role modelling (Candelaria, 2010) |

The total frequency of themes = 401.

The integrated competencies were broken, for example, Legal and ethical competency; legal + ethical.

4.7.1. Quantification

Counting keywords may identify patterns, frequencies, and distributions, and can provide the contextual use of the keywords. The number of keywords in each category and subcategory was counted once the categorization was completed (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

4.7.2. Interpretation

To interpret means to gain insight into the words as they appear in the text and make sense of the findings. The latent part of the summative content analysis involves sorting keywords into categories. Creating categories not only groups similar words but also creates knowledge and understanding of how the material is associated (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The description of the contents of subcategories and categories represents the manifest content. We held several reflective sessions between the authors to discuss the latent, underlying meaning of the content, the placement of specific subcategories, and their relevance to the outcome during the analysis, particularly in the process of sorting the keywords (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) (Table 5).

5. RESULTS

5.1. Characteristics of included studies

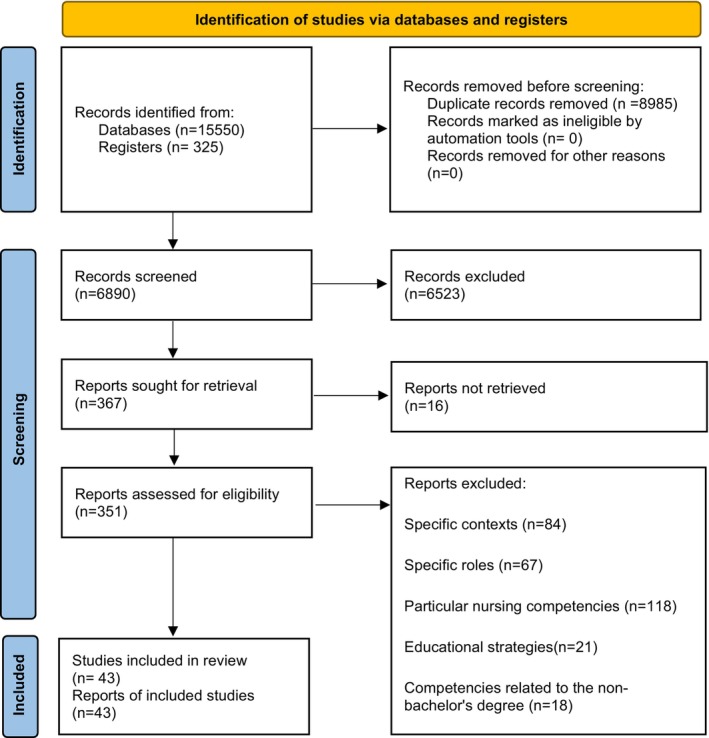

We screened a total of 15,875 record titles and abstracts and assessed the full‐text records of 351 studies for eligibility. Finally, we included 43 studies (Figure 1). The selected articles were from different countries and had various designs and methodologies. They included descriptive quantitative studies (n = 10, 23.25%), qualitative studies (n = 13, 30.23%), mixed methods (n = 16, 37.20%), and review studies (n = 4, 9.30%). Of the 43 articles, most were related to the development and psychometrics of the nursing competency scale (n = 18, 41.86%). Researchers in the United States (n = 8, 18.60%) conducted most of the studies. Most of the participants in the selected studies were frontline nursing managers, nurses, and newly graduated students (n = 30, 69.76%).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart.

5.2. Description of expected competencies

The scoping review identified five main themes (individualized care, professional nursing process, nursing administration, work readiness, and professional development), and 17 sub‐themes (Table 5).

5.3. Theme 1: Individualized care

The first expected competency is individualized care, which comprises four sub‐themes: value and ethical codes, therapeutic communication, participatory decision‐making, patient‐centred care, and cultural humility. According to selected articles (n = 40), NGRNs should possess the principles of health ethics and the professional nursing code of ethics, and ethical values. Additionally, they should be able to establish therapeutic communication and participatory decision‐making with the patient, the patient's family, staff, and other therapeutic teams (n = 30). Seven studies identified patient‐centred care as an essential competency. Furthermore, six articles emphasized that NGRNs need to possess knowledge, awareness, and cultural humility to show respect for the cultural context, values, and beliefs of the patient and to assess the care needs and concerns of patients from different cultures (Table 5).

5.4. Theme 2: Evidence‐Based Nursing care

The second competency that new nursing graduates are expected to have is evidence‐based nursing care, which comprises two subcategories: knowledge acquisition (18 studies), critical appraisal, and implementation of applicable evidence (38 studies). The knowledge base required for this competency includes basic biomedical nursing science, clinical knowledge, nursing theory, pathophysiology, pharmacology, natural, social, and behavioural science knowledge, as well as research awareness. New graduates must be capable of integrating up‐to‐date evidence into nursing care systematically and flexibly that meets the changing conditions of patients (Table 5).

5.5. Theme 3: Professional nursing process

The professional nursing process requires critical thinking skills. The current study identified three expected competencies for nursing students related to the nursing process: general critical thinking (n = 5), specific critical thinking (n = 27), and professional critical thinking (n = 30). General critical thinking includes cognitive ability and problem‐solving skills. In clinical nursing practice, problem‐solving skills are essential to provide good care, and nurses must use a variety of approaches such as trial and error, intuition, experimentation, and scientific methods to solve problems (Crisp et al., 2012). Specific critical thinking competencies include clinical reasoning and judgements, innovation, and making sound clinical decisions. We expect newly graduated nurses to have professional critical thinking skills (using the nursing process). Most of the reviewed studies (n = 30) emphasized that nursing graduates must apply the stages of the nursing process, including assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation to their practice (Table 5).

5.6. Theme 4: Nursing administration

The fifth theme comprised two subcategories: Management and leadership (n = 70) and informatics and documentation (n = 15). New nursing graduates must possess management skills, including time management, organizational skills, risk and workload management, resource management, and the ability to manage complex situations. Additionally, they may be required to provide teaching to assistant staff or students, delegate tasks effectively, and supervise assistants in the workforce. Leadership skills are also essential, including collaboration, partnership, inter‐professional competency, multidisciplinary team work, coordination of care, and a collaborative approach to care. Fifteen articles emphasized the importance of information technology and clinical documentation in nursing practice (Table 5).

5.7. Theme 5: Work readiness and professional development

This theme includes five subcategories: personal characteristics (n = 47), legality (n = 13), safety procedural skills (n = 32), preventative health services (n = 9), and mentoring competency (n = 9). Essential personal characteristics of nursing include self‐regulation, adaptability, stress management, self‐management, openness to development, professional self‐growth, professional attitudes, professionalism, personal and professional growth, social participation, and social intelligence. Newly graduated nurses are expected to be aware of legal standards and responsibilities, practice under professional standards, and be aware of legal boundaries in organizational and nursing practice. Additionally, they must provide nursing care that ensures patients' physical and psychological safety. Another expected competency is preventive health services, which involves the identification of health risk factors and the ability to work towards maintaining a healthy lifestyle or restoring/maintaining the patient's health. Finally, the mentoring sub‐theme comprises three parts: Career Development, Self‐Efficacy, and Role Modelling (Table 5).

6. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify the expected competencies of undergraduate nursing students. The selected articles revealed a complexity and variety of concepts in the definition of nursing competencies, and these competencies varied according to each country. The main domains of nursing competencies were defined in this study as knowledge, skills, and nursing values for work readiness, application of the professional nursing process, nursing management for individualized care, and professional development. These results are consistent with Lizzio and Wilson's (2004) finding that competencies are created by combining a range of attributes, including knowledge, values, and skills, to meet the needs of different clinical situations.

The first theme identified among the selected articles was the individualization of care, which had four sub‐themes. Today, governments and healthcare policies emphasize the importance of individuality in nursing education and nursing care (Delaney, 2018). The goal of nursing education, professional development programmes, nursing theories, models, and policies is to promote the individualization of care. Factors such as culture and religion form the foundation of the holistic philosophy, values, and ethical standards of nursing, which in turn are the basis for the individualization of care. This theme emphasizes that people hold different values, beliefs, and preferences, and therefore, healthcare providers should respect the unique needs of each patient (Ozdemir, 2019). So, Cho et al. (2022) considers the individualization of care as an indicator of the quality of care. Schools of nursing should emphasize individualized care throughout education (Ozdemir, 2019).

The second theme identified in this study was evidence‐based nursing care, with three sub‐themes of knowledge acquisition, critical appraisal of evidence, and implementing applicable evidence. In other words, evidence‐based care involves transforming relevant clinical challenges into answerable questions, searching sources and databases, integrating results with patient values and preferences, nurse knowledge and experience, and evaluating decision‐making consequences (Phillips & Neumeier, 2018). Studies have shown that evidence‐based care can serve as a framework for decision‐making in specific patient situations, leading to providing safe and cost‐effective care, and increasing patient satisfaction, and the self‐confidence of nurses (Liu et al., 2021; Sedgwick et al., 2014). It has also been described as one of the determining factors of nursing professionalism (Asi Karakaş et al., 2021).

The application of knowledge is one of the components that demonstrate competence in providing nursing care. This is the basis of clinical judgement and innovation in nursing and distinguishes professional nursing practice from other academic disciplines (Kennedy et al., 2015). However, some studies have shown that implementing evidence‐based nursing care can be a complicated and slow process (Horntvedt et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2022). One of the existing challenges in this field is the excessive focus of students on knowledge acquisition, which makes them often neglect the critical evaluation of evidence to answer clinical questions. Proper training can improve this competence (Colas & Vanguri, 2012). Therefore, undergraduate nursing students must learn to develop this skill under careful guidance. The IOM has emphasized that by 2020, 90% of nursing care should be evidence‐based, challenging nursing managers to formulate the theoretical and practical foundations of the curriculum correctly (Wallen et al., 2010).

The third theme of the study highlights the importance of integrating critical thinking with the nursing process and implementing professional nursing practices. Critical thinking competence has three main components: general, specific, and professional critical thinking. General critical thinking competencies include scientific process, hypothesizing, problem‐ solving, and decision‐making, which are not unique to nursing. Specific critical thinking competencies include diagnostic reasoning, clinical reasoning, and clinical decision‐making, which are used in nursing and other clinical disciplines. Professional critical thinking competency is the nursing process, which is unique to nursing (Kataoka‐Yahiro & Saylor, 1994). Sedlak and Ludwick (1996) also emphasized that critical thinking and the nursing process should not be seen separately from each other. Therefore, nursing educators have a crucial responsibility to integrate high‐level critical thinking skills with the nursing process and challenge students to reflect on their critical thinking abilities.

Management competencies are essential in identifying, guiding, and teaching nursing and include effective leadership, interdisciplinary teamwork, organization, control, and delegation of authority (Vituri & Évora, 2015). The fourth theme of the study is nursing administration, which includes management and leadership, informatics and documentation, and familiarity with nursing laws. Administration involves forecasting, planning, organizing, and decision‐making functions, which determine the basic framework of the organization. Clinical management is defined as nursing behaviours that provide direction and support to clients and the healthcare team in the delivery of patient care (Chappell & Richards, 2015). Therefore, management competencies are essential in identifying, guiding, and teaching nursing (Vituri & Évora, 2015) and include effective leadership, interdisciplinary teamwork, organization, control, and delegation of authority (Ferreira et al., 2022). However, some researchers claimed that management skill was the lowest priority skill for or nursing education systems; so NGRNs are not prepared to play these roles in the undergraduate course (Brown & Crookes, 2016). Therefore, nursing managers must guide and support NGRNs by clarifying role expectations (Brown & Crookes, 2016; Keshk & Mersal, 2017).

Familiarity with informatics technologies and nursing documents was one of the other sub‐themes of this category, which is needed to manage and improve the provision of safe, quality, and efficient care services by the best practice and professional standards (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2021). Managing and monitoring the effectiveness of nursing care services requires knowledge of information sources, recovery principles, and information management strategies (Lee et al., 2009). Currently, information technology knowledge is considered a key competency in the hospital environment that increases the ability of nurses not only to record nursing care but also to measure, report, and monitor quality, and effectiveness (Lee et al., 2009). It seems that in the current and future care system with the rapid development of information technology and its role in high‐quality nursing services, nursing students must master informational competencies (Thate & Brookshire, 2022).

Awareness of legal responsibilities is also necessary to manage and improve the provision of safe, quality, and efficient care (Ahmed, 2022). Especially, legal disputes regarding legal duties have increased with the expansion of nursing roles and responsibilities. However, facing the ethical dilemma of nursing within the framework of the law is one of the stressful factors for NGRNs. This is a useful finding that nursing managers can support them in dealing with moral complexities by creating a supportive and healthy work environment. According to Benner (2004), NGRNs have significant responsibility for the legal and professional issues of their patient, and their inexperience in this field can reduce the quality of care. Therefore, nursing programmes should increase legal education to instil professional values and integrate legal and ethical competencies in the nursing practice of students.

Work readiness competence was recognized as an important competence that involves identifying learning needs and fostering professional development. Individual characteristics play a significant role in shaping attitudes, behaviours, and professional growth (Aydın et al., 2022). The findings of Mallory et al. (2003) showed that some of these traits such as self‐regulation, personal and professional development, stress management, adaptability, self‐management, flexibility, openness, and professional attitudes contribute to professional development. Therefore, individuals must identify and strengthen their learning needs to achieve personal and professional development.

Independent and safe performance of clinical skills as the focus and core of nursing education is another important aspect of work readiness competence (Keshk & Mersal, 2017), which is considered one of the important challenges for NGRNs (Hartigan et al., 2010). It seems that safe clinical skills assessment is a professional necessity to ensure that nursing students can effectively deal with patients' clinical problems. Lastly, mentoring, as a sub‐theme of this competence, encompasses career development, self‐efficacy, and role modelling. It is considered a necessary competence for professional growth and a mechanism for exchanging information, acquiring new knowledge, and improving individual self‐esteem in nursing (Adeniran et al., 2013). In previous studies, the self‐efficacy component in mentoring has been given as one of the main factors determining career advancement. This component includes those beliefs and expectations from students to perform certain activities successfully (Kennedy et al., 2015).

7. STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

According to the review of extensive literature, it seems that the present study is one of the few studies that, with a large sample size, have conducted a comprehensive and structured search of available resources in the field of expected competencies of undergraduate nursing students. However, our study is not without limitations. A limitation of the present study is the exclusion of non‐English language articles, which may introduce potential publication bias. Additionally, while all competencies selected in this study are necessary for nursing students at the international level, it is important to update, localize, and tailor the proposed competencies to the cultural context of each country.

8. CONCLUSION

Developing competence is a crucial aspect of nursing education. It ensures that nursing graduates are equipped with the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to enter the workforce and perform effectively in entry‐level positions. These competencies serve as a valuable guide for developing undergraduate nursing curricula, and providing a framework for clinical education and evaluation of nursing students. These competencies serve as a shared language among higher education institutions, students, and the industry. They provide a clear understanding of what nursing students should achieve upon graduation. The competencies identified in this study can serve as a foundation for developing competencies at different levels of nursing education in various countries. Additionally, these competencies can serve as practical guidelines in healthcare settings and outline a foundation for further researches. The findings of this study have the potential to establish a framework that aligns the quality of learning with the realistic expectations of students' performance in clinical settings. Nursing managers can utilize these results to develop a competency‐based nursing curriculum, define clear objectives and job descriptions for students, and take steps towards the professionalization of students. This would involve designing educational content and evaluation tools to address these competencies at different levels throughout the academic semester.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Majid Purabdollah: concept design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafting of manuscript; Vahid Zamanzadeh: concept design, analysis and interpretation, drafting of manuscript; Leila Valizadeh: participated in the study design, data collection and analysis, manuscript revision; Akram Ghahramanian: participated in the study design, data collection, analysis, and drafting of manuscript; Saeid Mousavi: participated in the study design, analysis, and drafting of manuscript; Mostafa Ghasempour: data collection, analysis, and interpretation, drafting of manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This article is part of research approved with the financial support of the deputy of research and technology of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This article is part of the research approved with the financial support of the deputy of research and technology of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The approved code for this project is IR.TBZMED.AC.REC.1400.791.

Supporting information

Data S1:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Health Information Technology department at the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, who provided great help in accessing the databases. The authors appreciate the research deputy of Tabriz University of medical sciences for their financial support.

Purabdollah, M. , Zamanzadeh, V. , Ghahramanian, A. , Valizadeh, L. , Mousavi, S. , & Ghasempour, M. (2023). Competencies expected of undergraduate nursing students: A scoping review. Nursing Open, 10, 7487–7508. 10.1002/nop2.2020