Abstract

Interaction potentials between soil microarthropods and microorganisms were investigated with Folsomia candida (Insecta, Collembola) in microcosm laboratory experiments. Microscopic analysis revealed that the volumes of the simple, rod-shaped guts of adult specimens varied with their feeding activity, from 0.7 to 11.2 nl. A dense layer of bacterial cells, associated with the peritrophic membrane, was detected in the midgut by scanning electron microscopy. Depending on the molting stage, which occurred at intervals of approximately 4 days, numbers of heterotrophic, aerobic gut bacteria changed from 4.9 × 102 to 2.3 × 106 CFU per specimen. A total of 11 different taxonomic bacterial groups and the filamentous fungus Acremonium charticola were isolated from the guts of five F. candida specimens. The most abundant isolate was related to Erwinia amylovora (96.2% DNA sequence similarity to its 16S rRNA gene). F. candida preferred to feed on Pseudomonas putida and three indigenous gut isolates rather than eight different type culture strains. When luciferase reporter gene-tagged bacterial strains were pulse fed to F. candida, gut isolates were continuously shed for 8 days to several weeks but Escherichia coli HB101 was shed for only 1 day. Ratios of ingested to released bacterial cells demonstrated that populations of nonindigenous gut bacteria like Sinorhizobium meliloti L33 and E. coli HB101 were reduced by more than 4 orders of magnitude but that the population of gut isolate Alcaligenes faecalis HR4 was reduced only 500-fold. This work demonstrates that F. candida represents a frequently changeable but selective habitat for bacteria in terrestrial environments and that microarthropods have to be considered factors that modify soil microbial communities.

Microorganisms provide the metabolic basis for nutrient cycling in soil. In undisturbed soils, many of these microorganisms are associated with habitats provided by eukaryotic organisms, e.g., plant rhizospheres or guts of soil animals. Compared to bulk soil, such ecological niches are often characterized by higher concentrations of nutrients and increased microbial biomass (22). It can be expected that in these habitats, rates of nutrient cycling are much higher and potential disturbances are more dramatic than in bulk soil, because in bulk soil most bacterial cells are more or less in the status of starvation (51, 57).

The importance of soil animals, especially in the initiation of decomposition of organic substances which normally enter the soil as plant material, is well established (5). Food webs, in which different groups of soil animals interact, accelerate the reentry of plant material into the nutrient cycle (40, 50, 74). Among the soil animals, microarthropods, a group which consists in most soils mainly of mites and collembolans (springtails), enhance the flow of organic carbon by fragmentation and communition (physical restructuring) of organic matter (62). Microarthropods, which can occur in soil at densities in the range of 104 to 105 specimens per m2 (44), have well-developed mouth parts with which they disrupt and cut up organic substances. This process increases the surface areas of the substrates and makes them more accessible for microbial colonization (27). The gut passage may also enhance rates of decomposition by inoculating the organic material with bacteria, which might continue to grow outside the gut in the feces (33, 41, 58).

Each component of the faunal food web can provide specific mechanical and enzymatic functions and potentially also a large variety of different habitats for microorganisms. Thus, to understand the ecological significance of a faunal group, it is also important to investigate whether specific microorganisms or microbial communities exist and what functions would be provided by them. A high diversity of microorganisms has already been isolated from a large variety of macroarthropods, especially insects (11, 16, 23, 48, 61, 71), but only a few reports which try to identify bacteria from microarthropods exist. Compared with those of other soil invertebrates, gut sizes of microarthropods are several orders of magnitude smaller and thus, presumably, more exposed to conditions provided by the surrounding environment. For mites, microbial communities consisting mainly of bacteria have been described (65, 70, 84). These bacterial communities varied depending on the species, the age of the specimens, the habitats from which they were isolated, and the substrates which they were fed (65, 84).

Even less is known about microorganisms associated with collembolans. Fungi were isolated from four soil- or dung-inhabiting collembolans, among which were two species of the genus Onychiurus, but it could not be concluded in that study whether some of these isolates contributed to a gut-specific microflora (19). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) detected the presence of fungal mycelia and some bacterial cells in the gut of the soil collembolan Folsomia candida, but it was concluded that the presence of fungi was primarily a result of the ingestion of fungal hyphae as a food substrate (77). High numbers of bacterial cells, 3.8 × 1011 CFU per g of gut contents, were isolated from the same species; among them were chitin-degrading bacteria which were probably involved in the use of exuviae by the insects (10).

In contrast to more highly evolved insects, Apterygota, a taxonomic subclass which includes collembolans, molt throughout their entire life cycle. At each molting cycle the midgut epithelium regenerates together with the cuticle (39). Additionally, it was shown for the collembolan Tomocerus minor that specific gut cells continuously excrete substances which generate the peritrophic membrane (39), a mucoid substance which is supposed to facilitate the transport of the food bolus through the alimentary canal (59). Since molting occurs at intervals of only several days (68), microbial colonization of the gut, as it has been described by Borkott and Insam (10), should frequently be affected by these processes.

Feeding activities of soil animals should affect the microbial communities colonizing organic or inorganic substances. Depending on the selectivity of the gut, ingested microbial cells may be lysed and digested, but they may also be able to grow and colonize the gut. Such processes, which can decrease or amplify specific members of a microbial community, have been shown to be of importance in aquatic habitats (34) and have also been considered to figure in microorganism-earthworm interactions (13, 53) and the effects of invertebrates on soil microorganisms (30).

We conducted this study in order to reveal if the gut of a collembolan can be a selective habitat and vector for microorganisms and if feeding activities of collembolans can potentially affect microbial community structures in terrestrial ecosystems. As a model organism, we selected the nonpigmented, soil-dwelling collembolan F. candida, which we kept in laboratory breeding stocks. F. candida is a cosmopolitan insect which can be found in soil preferentially among the litter or humus fraction (47). It feeds on organic material, fungal hyphae, nematodes, or bacterial cells (4, 6, 45). Microbial colonization of the gut was characterized by different microscopical techniques and cultivation-dependent methods. The diversity of microorganisms isolated from the gut of F. candida was assessed and marker-gene-tagged bacterial cells, which were fed to F. candida in laboratory experiments, allowed us to specifically monitor the fates of ingested cells as affected by the passage through the alimentary system of F. candida.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms, maintenance, and media.

An initial breeding stock of F. candida was obtained from O. Larink (Technical University, Braunschweig, Germany). The animals were bred in plastic vessels floored with a 10:1 gypsum and charcoal mixture (31). The breeding stocks were kept at 18°C in the dark, and the insects were routinely fed with autoclaved brewer’s yeast.

The following bacterial type culture strains obtained from the German type culture collection for microorganisms (DSM, Braunschweig, Germany) were included in this study: Agrobacterium radiobacter CCM1040, Bacillus subtilis BD466, Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032, Escherichia coli K-12 HB101, Pseudomonas putida PaW340, and Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 17533. Sphingomonas paucimobilis HG1 without and with plasmid pSUP202-luc (Cmr luc [which encodes the firefly luciferase marker gene]) were provided by J. Schiemann (Biologische Bundesanstalt, Braunschweig, Germany). Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 (Smr) and L33, a derivative of 2011 with a chromosomal insertion of the luc gene (64), were gifts from A. Pühler (University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany). E. coli XL1Blue pAG108 (Apr Kmr gfp [green fluorescent protein] [72]), was donated by Andrea Güttler and K. N. Timmis (Gesellschaft für Biotechnologische Forschung, Braunschweig, Germany). Pseudomonas stutzeri JM300 (15), genetically engineered with a miniTn5-delivered (25), chromosomally inserted bph operon (bphDXCBA, 12 kb) as a marker gene (29) and the nptII gene (Kmr), was constructed and kindly provided by V. Farelly (University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom). E. coli S17-1 pRP4-luc (Tcr luc) is described in the accompanying paper (38). Saccharomyces cerevisiae WHL202 with plasmid p707, which was originally obtained from H. Wehlmann, Bayer AG, Wuppertal, Germany (80), with an additional luciferase gene cassette inserted as an HindIII fragment into the multicloning site, resulting in p707-luc, was constructed for this study in our laboratory (unpublished). Additionally, the following pure-culture gut isolates of F. candida were included in this study: Arthrobacter citreus BI90, Alcaligenes faecalis HR4 pRP4-luc (Tcr luc), Pseudomonas pseuodoalcaligenes HR1 pRP4-luc (Tcr luc), and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia HR2 pRP4-luc (Tcr luc) (38).

All bacterial strains, which were stored as cryocultures (Mast Diagnostica, Reinfeld, Germany) at −70°C, were cultivated in YT broth (60). Antibiotics were added when necessary as sterile filtered solutions after the broth was autoclaved at the following final concentrations (per liter): 100 mg for ampicillin, 50 mg for chloramphenicol, 50 mg for kanamycin, 500 mg for streptomycin, and 20 mg for tetracycline.

The following media, modified when possible with the appropriate antibiotics, were used to isolate marker gene-tagged monitoring strains from the feces of F. candida. E. coli S17-1 pRP4-luc, A. faecalis HR pRP4-luc, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia HR2 pRP4-luc were isolated on YT agar. Additionally, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia HR2 pRP4-luc and also P. putida HR1 pRP4-luc were cultivated on 10-fold-diluted M9 medium (60) with 5 mM benzoic acid as the sole carbon source. Sphingomonas paucimobilis HG1 pSUP202-luc was isolated on 10-fold-diluted YT. Sinorhizobium meliloti L33 was selectively cultivated on nutrient-poor medium (12). Pseudomonas stutzeri JM300 (bph) was cultured in closed containers on M9 medium without a carbon source, but some crystals of biphenyl attached to the lids of the petri dishes.

Fungi were cultivated onto yeast malt (YM) agar with 50 μg of chloramphenicol liter−1 or YM broth cultures, both at pH 6.0 (81). For cultivation of S. cerevisiae, YM agar was adjusted after being autoclaved to pH 3.8 (81).

Incubation conditions.

Bacterial broth cultures (if not otherwise stated, 100 ml in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with indentations) were incubated at 28°C, except with E. coli, which was cultured at 37°C, on a rotary shaker (TM-3; Infors AG, Basel, Switzerland) at 200 rpm. Cells grown to late log phase were harvested by centrifugation at 4,100 × g for 10 min (centrifuge type 5403; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Cells were resuspended in approximately 2 ml of sterile water containing 0.85% NaCl or, to check feeding activities of F. candida, in 0.03 M food color (New Coccine, color index 16255; Aldrich-Chemie, Steinheim, Germany) (76).

All experiments with F. candida were conducted with petri dish microcosms. The petri dishes contained a layer of water-agar (25 ml, 1.5% [wt/vol] covered completely with a sterile nylon membrane (Hybond N; Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Depending on the type of experiment, one or two YTP agar cubes (composition per liter, 2.0 g each of yeast extract [Serva, Heidelberg, Germany], tryptone [Merck, Darmstadt, Germany], and soy peptone [Oxoid, Unipath, Wesel, Germany] [pH 7.2] in 1.5% agar; surface size of cube, 1.3 by 1.3 cm; height, 0.5 cm) were placed in the center (one cube) or in opposite positions (two cubes) on the membranes. Each cube was then carefully inoculated with a total of 200 μl of a bacterial cell suspension. This corresponded to approximately 1010 bacterial cells per agar cube. The petri dish microcosms were incubated during the experiments at 18°C in the dark.

Microscopy.

A binocular stereo microscope (VM-ILA-2; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe F. candida specimens in the microcosms (petri dishes) and to distinguish molting and nonmolting specimens by their colored gut contents. Living F. candida specimens, fed with green fluorescent protein (Gfp)-tagged bacterial cells, were also observed with an epifluorescence microscope (excitation wavelength, 450 to 490 nm; emission filter, 520 nm; Axioplan; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Photographs were taken with a model MC100 camera (Zeiss) with Kodak Gold 400 ASA film.

Samples for both light microscopy and SEM were prepared from F. candida specimens fed for 3 days with YTP medium, which was colored with 0.03 M New Coccine in order to distinguish specimens according to their feeding activities. Specimens with colored gut contents were transferred into test tubes containing a formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde-fixation solution according to the method of Karnovsky (43) and additionally 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) as a detergent. For fixation, the tubes were incubated at 60 kPa at room temperature overnight. The F. candida specimens were then washed in 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h at 4°C. After being washed as described above, the insects were dehydrated by acetone treatments.

For SEM, the samples were dried at the critical point of CO2 and embedded in glue mixed with charcoal on an aluminum microscopic slide mount. The samples were cut sagittally with a razor blade and cold sputter coated with gold. Feces were prepared by moistening the membrane filter of the feeding chamber with 500 μl of fixation solution for 1 h. Then, the filter was completely immersed in the solution and left overnight. The feces were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide and dehydrated. Filter pieces (0.5 by 0.5 cm) were dried at the critical point of CO2, subsequently mounted on the microscopic slide mounts with conductive silver, and cold sputter coated with gold. SEM was conducted with a model 60 microscope (International Scientific Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) at 10 kV. Photographs were taken with Ilford PAN-F50 film.

For light microscopy, dehydrated samples were embedded in epoxy resin (69) and 0.5-μm sections were prepared with an ultra microtome (MT-7; RMC, Tucson, Ariz.). The sections were mounted onto glass slides, air dried, and stained with basic fuchsin and crystal violet. The sections were embedded in Entellan (Merck) and sealed with coverslips.

In order to increase the transparency of nonpigmented F. candida specimens, which was necessary to determine the gut size, whole specimens were incubated in a 90% lactic acid solution at 70°C for approximately 10 min. The insects were then carefully transferred with a pipette onto glass slides with cavities and closed with coverslips for microscopical observation.

Volume determinations of gut and fecal pellets.

The gut volumes of F. candida insects with and without food boluses were determined by taking length and width measurements by three different microscopical methods: (i) transparent specimens were treated with lactic acid and examined microscopically, (ii) sagittal sections were examined with a light microscope, and (iii) sagittal sections were examined with an SEM. For calculation of the volumes it was assumed that the rod-shaped gut was a cylinder. The volumes of the spherical fecal pellets released by F. candida were determined by diameter measurements of pictures taken by SEM.

Quantitative and qualitative characterization of gut microorganisms of F. candida.

Numbers of gut bacteria were determined by collecting specimens which had been fed with color-labeled autoclaved yeast cells. After 2 days of feeding, the specimens were anaesthetized with CO2 gas and incubated in 70% ethanol for 10 s for surface sterilization. A total of 25 specimens were selected, the gut contents (colored or not colored) were recorded, and each of these specimens was transferred into a separate 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube (Safe Lock). The insects were homogenized with a micro-mortar (Eppendorf). Then, 400 μl of 0.85% NaCl solution was added to each tube and the suspensions with appropriate dilutions were inoculated onto YT agar containing 100 μg of cycloheximide ml−1 to determine bacterial numbers and onto YM agar with chloramphenicol (50 μg ml−1) to determine the abundance of yeast cells. Both media were incubated at 18°C, and CFU were determined after 7 days (YT agar) and 19 days (YM agar) of incubation. Direct counts of gut bacteria could not be assessed with F. candida homogenates due to the presence of bacterial cells originating from intracellular structures (mycetocytes).

Colonies with different morphologies were subcultured three or more times onto the different growth agars to obtain pure-culture isolates. Each strain was then characterized by their carbon source utilization profile on microtiter plates (Biolog Inc., Hayward, Calif.) and growth on other selected carbon sources. To check use of and growth on benzoic acid and on 2-hydroxybenzoic acid, strains were inoculated onto 10-fold-diluted M9 agar (60) without glucose but with either 5 mM benzoic acid or 10 mM 2-hydroxybenzoic acid. Cellulose utilization was determined according to the method of Suyama et al. (73), and chitin utilization was determined according to the method of Lingappa and Lockwood (46). Furthermore, fatty acid methyl ester analysis (FAME) was used to differentiate the isolates based upon their lipid compositions (66). Fatty acid patterns were quantified by use of gas chromatography (49). The Gram stain reaction was tested according to the method of Powers (56) with 3% aqueous KOH solution. Finally, the amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (ARDRA) technique (82) and, with representative isolates, DNA sequencing of the PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes, as described in the accompanying paper (38), were used to differentiate and characterize the isolates.

The fungus isolated in this study was identified by the German Type Culture Collection (Braunschweig, Germany).

Quantitative characterization of fecal microorganisms.

To investigate the ratio of live to dead microorganisms, as well as the ratio of culturable to nonculturable microorganisms, in the feces a total of 200 specimens of F. candida were fed with colored, sterile YTP agar. After 2 days, 40 specimens with colored gut contents were removed from the microcosms and transferred into petri dishes filled with water-agar. After 4 h, fecal pellets on the water-agar were counted and suspended in 2 ml of 0.85% NaCl solution. An aliquot (50 μl) of each suspension was then stained with 0.2 μl of the live/dead stain (Live/Dead BacLite; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) according to the method of Haugland (35). The viable and nonviable cells were counted in a counting chamber with a fluorescence microscope (excitation, 450 to 490 nm; emission filter, 520 nm; Axioplan; Zeiss). Another aliquot of each suspension was inoculated with appropriate dilutions onto YT agar with cycloheximide and plate count agar (Oxoid, Unipath) and incubated for 7 days at 28°C to determine the CFU.

Feeding preferences of F. candida.

To examine the selective grazing on bacterial food, all possible pairwise combinations of the selected bacteria were tested. The tests were carried out in petri dishes with two food samples on opposite sides of the dishes as described above. A total of 50 adult animals which had been starved for 1 day were introduced into the centers of the chambers and incubated at room temperature in the dark. After 24 h the number of animals feeding on each sample was recorded. All tests were replicated four times. A palatability ranking of all tests was set up according to the method of Shaw (67).

Persistence and gut colonization capacities of selected microbial strains.

To study the gut persistence of fed microbial cells, a total of 100 F. candida specimens which had been starved for 1 day were incubated with selected marker-gene-labeled strains. At the end of the feeding incubation, the animals were transferred into water-agar petri dish microcosms with central sterile YTP agar cubes as a food source. At 24-h intervals, F. candida specimens were transferred into new microcosms to allow daily analysis of the feces. The fecal pellets were extracted from the water-agar surface with 0.85% NaCl solution and inoculated onto monitoring strain-specific media and onto YT agar as a control. The expression of the respective marker genes in grown colonies was determined by checking for luciferase according to the method of Selbitschka et al. (63) and for 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase according to the method of Furukawa and Miyazaki (28).

Impact of passage through the gut on ingested microbial populations.

To determine the period between the ingestion and the release of microbial cells, a total of 40 starved F. candida specimens were released into a test chamber without a filter. A streak (1 by 0.1 cm) of living brewer’s yeast cells mixed with 10% (wt/vol) charcoal and 60% (wt/vol) water was placed in the center of each chamber. A total of 60 chambers were prepared, and every 8 min the populations of 4 chambers (replicates) were removed. Their feces were examined for black particles.

The amount of ingested cells of selected bacterial strains by F. candida was determined in order to allow a quantitative description of the digestion process. A total of 100 F. candida specimens which had been starved for 1 day were fed with the selected bacterial strains. The control (no feeding) consisted of chambers with colored food samples but without F. candida. All tests were performed in triplicate. The chambers were incubated for 48 h at 18°C in the dark. The cells of the food samples were resuspended in 10 ml of sterile 0.85% NaCl solution, serially diluted, and incubated on the media selective for the appropriate monitoring strain.

The same test design described above was used to determine the number (per hour) of fecal bacterial cells released by F. candida. After feeding, 10 specimens with colored gut contents were collected and transferred into 1.5-ml tubes (Safe Lock; Eppendorf). The other animals with colored gut contents were transferred to petri dishes with water-agar. After 4 h, sufficient feces were obtained for analysis. The insects were removed, and the fecal pellets on the water-agar were counted (approximately 1,000). The fecal pellets were extracted from the media as described above. The animals in the Eppendorf tubes were homogenized and then suspended in 200 μl of NaCl. The feces and homogenate suspension were serially diluted and inoculated onto the appropriate selective medium or on nonselective medium as a control.

Statistical methods.

The differences of the individual feeding choices were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U-test. The uptake and release rates were analyzed by using one-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Structure and microbial colonization of gut and feces.

In order to be able to characterize bacterial densities inside the gut of F. candida, microscopical determinations of the gut dimensions of adult specimens were measured by a combination of three different techniques (see Materials and Methods). The small foregut (average volume, 0.21 nl) and hindgut (0.06 nl) could be distinguished from the relatively large, rod-shaped midgut. The midgut volumes of three specimens with gut contents (food bolus) ranged from 5.9 to 11.2 nl. The midgut volumes of two animals with empty guts were only 0.66 and 1.08 nl. Bacterial cells could be detected in the midgut and in the folds of the hindgut but not in the foregut.

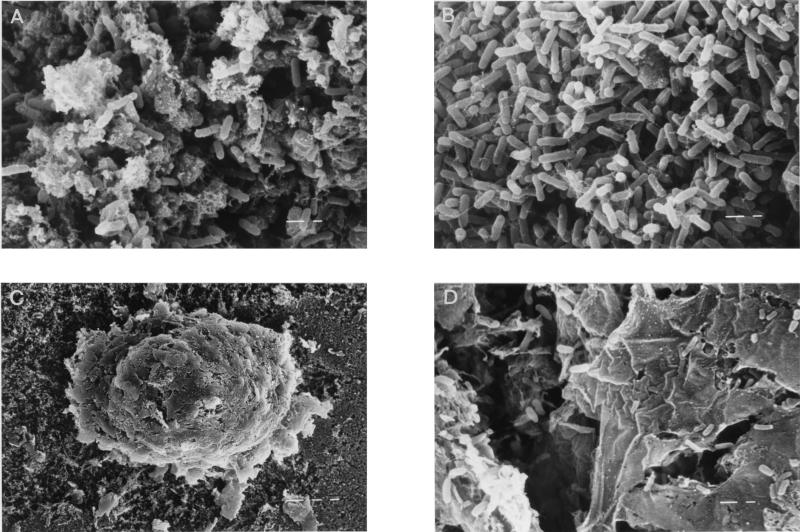

Microbial colonization of the midgut was analyzed in more detail by SEM. High numbers of bacterial cells and a few fungal hyphae (not shown) were detected in the food bolus (Fig. 1A). A matrix consisting of mucoid and fibrillic structures, the peritrophic membrane, was identified between the gut epithelium and the food bolus. Several regions of the peritrophic membrane were densely colonized with predominantly rod-shaped, bacterial cells (Fig. 1B). Fecal pellets, which were also analyzed by SEM, were enveloped by excreted fragments of the peritrophic membrane (Fig. 1C). Bacterial cells of different cell morphologies could be detected in this region, as shown in Fig. 1D.

FIG. 1.

SEM micrographs of the midgut region and feces of F. candida, fed with sterile substrate. Microbial colonization of the food bolus (A) and peritrophic membrane (B), as detected in the midgut, is shown. The fecal pellet (C) with excreted fragments of the peritrophic membrane and colonized with bacterial cells (D) is also shown. Left bars in panels A, B, and D, 1 μm; left bar in panel C, 10 μm.

Fecal pellets collected from animals fed with sterile substrate (autoclaved yeast cells) had an average volume of 1 nl. The total number of bacterial cells per pellet, as detected by light microscopy, was 1.55 × 104 (1.55 × 1010 cells ml−1; four replicates). Live/dead staining of cells (see Materials and Methods) revealed that only a small fraction of these cells were dead (0.0042%). However, only 5.49% (8.51 × 102 CFU per pellet) of the detected cells were able to grow on YT agar under aerobic conditions. Similar results (4.35%) were obtained with plate count agar as a growth substrate (data not shown).

Diversity and distribution of gut-associated microorganisms.

F. candida specimens were fed with autoclaved color-labeled yeast cells for several days before microbial cells were extracted from the gut. Actively feeding specimens could be distinguished from other specimens, which were occupied with molting and not feeding, by their colored gut contents. The numbers of cultivated heterotrophic and aerobic YT agar-cultured microorganisms isolated from specimens of the feeding group (15 specimens analyzed) varied by 1 order of magnitude (1.6 × 104 to 2.7 × 105 CFU specimen−1), whereas the numbers for specimens from the molting group (10 specimens analyzed) varied by almost 4 orders of magnitude (4.9 × 102 to 2.3 × 106 CFU specimen−1). Molting, a process which occurred under our selected laboratory conditions at intervals of approximately 4 days (data not shown), apparently influenced the density of microbial cells in the gut drastically.

The diversity of YT agar-cultured gut bacteria was determined with five specimens taken from the feeding group. A total of 45 pure cultures contained organisms that clustered into 11 different types by a combination of Gram staining, physiological testing, fatty acid pattern analysis, and ARDRA (Table 1). Seven types were capable of using aromatic compounds as growth substrates, but only one type could use cellulose and chitin. All 11 types were distinguishable by their colony morphologies, and thus, an attempt was made to estimate the abundance of each type (Table 1). The quantitative relationship of the different types (evenness) was also reflected in the number of isolates obtained for each type and the number of F. candida specimens from which they could be recovered. The most abundant isolates, types 1 and 2, of the representative strains T101 and T105 were isolated from all five specimens analyzed and accounted for more than 80% of all isolates. The gram-negative strain T101, which was characterized by nearly complete sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene as amplified by PCR, was related to Erwinia amylovora (96.2% similarity to a data bank isolate). The gram-positive isolate T105 was tentatively identified as Staphylococcus capitis on the basis of its carbon source utilization pattern (BiologGP; 98.2% similarity to a Biolog data bank type strain). Isolate T104 was related to Pantoea agglomerans (16S rRNA gene). Surprisingly, the bacterial isolates of type 4 and type 9 could not be amplified with eubacterial 16S rRNA gene universal primers in PCRs. A filamentous fungus isolated from one F. candida specimen was identified as Arcremonium charticola (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Diversity of the most abundant bacteria isolated from the gut of F. candida on YT growth agara

| Type | Representative isolate | No. of isolates | Pattern type by:

|

Carbon utilization from source:

|

Gram stain reaction |

F. candida specimen no.

|

Estimated abundance (CFU specimen−1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARDRA | FAME | BA | 2-HB | CMC | Chitin | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| 1 | T101 | 9 | A1 | F6 | − | + | − | − | − | x | x | x | x | x | 1.2 × 105 |

| 2 | T105 | 5 | A2 | F9 | − | − | − | − | + | x | x | x | x | x | 4.2 × 104 |

| 3 | T104 | 5 | A6 | F6 | + | + | − | − | − | x | x | x | 1.3 × 104 | ||

| 4 | T901 | 9 | NA | F2 | + | + | − | − | + | x | x | x | 6.6 × 103 | ||

| 5 | T107 | 3 | A8 | F1 | + | − | + | + | + | x | 5.2 × 103 | ||||

| 6 | T1403 | 4 | A5 | F4 | − | − | − | − | − | x | x | x | x | 4.3 × 103 | |

| 7 | T404 | 3 | A3 | F7 | + | + | − | − | + | x | x | 3.8 × 103 | |||

| 8 | T406 | 3 | A4 | F8 | − | − | − | − | + | x | x | x | 2.1 × 103 | ||

| 9 | T902 | 1 | NA | F3 | − | − | − | − | + | x | 1.2 × 103 | ||||

| 10 | T109 | 1 | A7 | F5 | + | + | − | − | − | x | 4.0 × 102 | ||||

| 11 | T407 | 2 | A9 | ND | − | + | − | − | − | x | ND | ||||

NA, not amplifiable by PCR with the selected eubacterial primers; ND, not determined; BA, benzoic acid; 2-HB, 2-hydroxybenzoic acid (salicylate); CMC, carboxymethyl cellulose; −, no growth; +, growth; x, positive detection.

Feeding preferences of F. candida and gut persistence of genetically tagged bacterial strains.

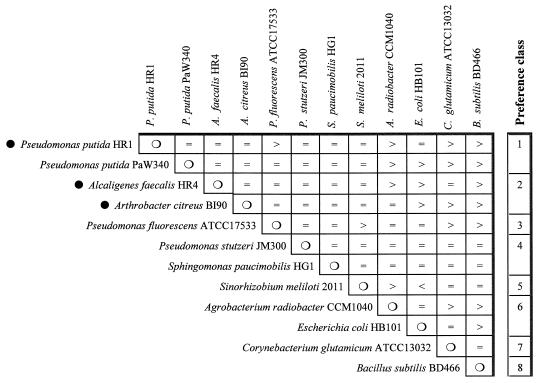

Twelve different bacterial species, including gram-positive and -negative type culture strains and three strains isolated from the gut of F. candida (see the accompanying paper by Hoffmann et al. [38]) were fed to F. candida specimens in pairwise choice tests (see Materials and Methods). From a total of 66 tests, 22 tests showed significant preferences (P < 0.05). F. candida fed on all species tested, but eight preference classes could be established. P. putida from a culture collection and all three gut isolates, including, with highest preference, strain HR1, with 99.1% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to P. putida (Hoffmann et al. [38]), were preferred to the other species tested (Fig. 2). E. coli and both gram-positive bacterial isolates included in this test showed the lowest preference values.

FIG. 2.

Feeding preferences of F. candida for selected bacterial species as determined in pairwise choice tests. Preference classes (highest palatability, class 1) were significantly different (P ≤ 0.05). •, gut isolates of F. candida.

The persistence and gut colonization capacity of ingested bacterial cells were specifically monitored by feeding different bacterial species tagged with a reporter gene (luc or, in the case of P. stutzeri, bphC). After each strain was fed during a preincubation of several days separately to subgroups of F. candida, a sterile substrate (YTP agar) was fed to the specimens and the occurrence of the monitoring strain in feces was analyzed daily. The gut isolates A. faecalis HR4 and P. putida HR1, both tagged with plasmid pRP4-luc, could be recovered from feces over the total monitoring periods of 56 and 20 days, respectively (Table 2). Luciferase-positive colonies with morphologies different from that of A. faecalis or P. putida occurred frequently on the detection medium. These cells, which must have been transconjugants of pRP4-luc (data not shown; for more information, see the accompanying paper [38]), were not further analyzed in this study. Transconjugant numbers were excluded when the persistence of A. faecalis or P. putida was assessed. The persistence of the other F. candida gut isolate, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, was assessed on two different selective media which were available for this strain: M9 with benzoic acid as the sole carbon source and YT with tetracycline. The detection periods of 8 and 11 days were similar and indicated that the detection medium did not dramatically influence the persistence data obtained for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. All other strains tested were less persistent than the above-mentioned isolates. E. coli cells could be detected only 1 day after feeding, which indicated that the cells were not able to colonize and survive in the gut of F. candida.

TABLE 2.

Excretion periods and fecal concentrations of selected bacterial marker gene-tagged strains after pulse feeding of F. candida

| Monitoring strain | Last day of:

|

Fecal concn (CFU specimen−1 day−1)

|

Total no. of fecal cells (CFU specimen−1 day−1)

|

Preincubation (feeding) period (no. of days)c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection | Observation | After 1 day of observation | At the last day of detection | After 1 day of observation | At the last day of detection | ||

| Alcaligenes faecalis HR4 pRP4-luc | 56 | 56 | 1.71 × 103 | 5.27 × 101 | 2.41 × 105 | 1.07 × 107 | 4 |

| Pseudomonas putida HR1 pRP4-luc | 20 | 20 | 3.48 × 105 | 4.63 × 101 | 6.07 × 106 | 1.98 × 106 | 8 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia HR2 pRP4-luc | 8a, 11b | 20a, 52b | 2.11 × 105 | 7.51 × 101 | 5.69 × 106 | 2.65 × 106 | 8 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti L33 | 7 | 15 | 1.11 × 103 | 9.03 × 101 | 1.40 × 107 | 4.67 × 107 | 5 |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis HG1 pSUP202-luc | 3 | 7 | 3.31 × 103 | 1.40 × 100 | 9.85 × 106 | 3.51 × 106 | 8 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae WHL202 p707-luc | 3 | 10 | 9.62 × 100 | 1.36 × 10−1 | 7.60 × 106 | 1.83 × 106 | 3 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri JM300 FV1(bph) | 2 | 7 | 1.53 × 104 | 1.07 × 100 | 3.55 × 106 | 4.26 × 106 | 6 |

| Escherichia coli S17-1 pRP4-luc | 1 | 4 | 1.04 × 101 | 1.04 × 101 | 2.40 × 105 | 2.40 × 105 | 5 |

Determined on M9 agar with benzoic acid as the sole carbon source.

Determined with YT agar with tetracycline.

Feeding periods of the strains before the beginning of analysis are indicated in the preincubation time. During the detection period, F. candida was fed with sterile substrate.

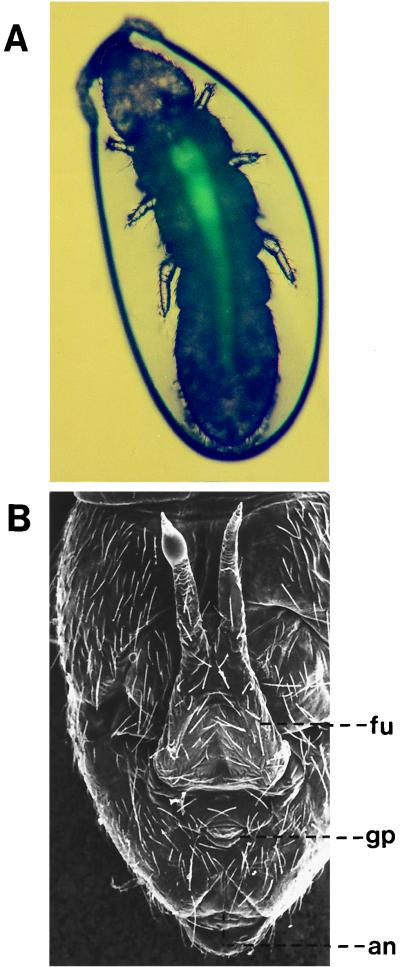

By using the gfp marker gene, the fate of E. coli cells in F. candida specimens, which had been fed for several days with such cells, could be visualized in living specimens directly by epifluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3). Green fluorescent cells occurred at high concentrations in the cranial part of the midgut but in decreasing amounts towards the hindgut region. The hindgut itself did not contain detectable amounts of the green fluorescent protein (Gfp). Thus, E. coli cells were lysed during the gut passage and the Gfp itself was unstable in the gut.

FIG. 3.

(A) Epifluorescent microscopic photograph of a living F. candida specimen (length, 2 mm), which had been fed for several days with a recombinant, green fluorescent protein-expressing E. coli strain. The insect was trapped in a Saran Wrap bulb, which explains the circular boarder line around the specimen. (B) SEM micrograph of the abdominal, ventral region of F. candida to demonstrate the position of the anus (an). Also visible are the forked springing organ (furca [fu]) and the genital opening (gonopore [gp]).

Impact of the gut passage on microbial population sizes.

The period between ingestion and excretion of substrate, as determined with colored autoclaved brewer’s yeast as a food source, lasted only 35 min under the conditions in our microcosms (data not shown). In order to determine whether this period was sufficient to account for the persistence values shown in Table 2, we further quantified the selective force that was imposed onto ingested bacterial cells during the gut passage with three bacterial strains, which were presumably different in their rates of survival. In separate microcosms the strains which were all genetically marked with the luc gene were fed to F. candida. Uptake and release rates of the monitoring strains as well as their quantitative occurrence in the gut and feces were analyzed. In accordance with the persistence data (Table 2), the titer of E. coli cells in the gut was much lower than that of A. faecalis (Table 3). Surprisingly, Sinorhizobium meliloti occurred at numbers comparable to those of A. faecalis. In feces, however, the number of detectable Sinorhizobium meliloti cells was an order of magnitude below that of A. faecalis. The titer of E. coli cells in feces was more than 2 orders of magnitude below that of A. faecalis. The ratio of cells released from the gut to ingested cells demonstrates the impact of the gut passage on the different bacterial species. The number of E. coli organisms was reduced over 60,000-fold, whereas the number of A. faecalis organisms was reduced approximately 500-fold. The ratio of digested to ingested cells for Sinorhizobium meliloti was of the same order of magnitude as that assessed for E. coli, which suggested that these cells were efficiently excreted from the gut of F. candida.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative determination of the impact of the gut passage of F. candida on population sizes of selected bacterial, marker gene-labeled strainsa

| Monitoring strain | Uptake rate (CFU h−1 specimen−1)b | No. of bacteria in the gut (CFU specimen−1)c | No. of bacteria in feces (CFU fecal pellet−1)d | Release rate (no. of fecal pellets specimen−1 h−1) | Reduction factore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli S17-1 pRP4-luc | 5.13 × 105 | 4.29 × 100 | 1.72 × 100 | 485 | 61,588 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti L33 | 7.49 × 106 | 2.34 × 104 | 8.79 × 101 | 224 | 38,077 |

| Alcaligenes faecalis HR4 pRP4-luc | 6.90 × 105 | 3.00 × 104 | 5.71 × 102 | 248 | 487 |

All data shown for each parameter were significantly different from each other (P ≤ 0.05).

Determined with three parallel incubations.

Determined with 10 specimens per species.

Determined with four parallel incubations.

The reduction factor is the uptake rate per number of cells of the monitoring strain in the feces per release rate.

DISCUSSION

Despite their potential ecological importance for nutrient cycling in soil, only a few reports which have tried to identify microorganisms associated with microarthropod guts exist. Compared to gut volumes found for a selection of macroarthropods, which ranged from 10 μl to 1 ml (16), the gut volume of the representative microarthropod in this study, F. candida, was 3 to 6 orders of magnitude lower. Earlier investigations considered that, due to the small gut volume, microbial populations in the guts of microarthropods might be affected only by the habitat of the insect (70) or by their feeding preferences (19, 77). SEM analysis of F. candida specimens, which had previously been fed with organic, fungus-colonized substrates, detected fungal mycelia and few bacterial cells in the midgut. However, in our study, dense layers of bacterial cells and only a few fungal hyphae which were associated with the food bolus were found in the midgut. Bacterial cells were either attached to the peritrophic membrane or visible as single cells or microcolonies in the food bolus. The detected microorganisms could not originate from the food source, as suspected by Tochot et al. (77) in the previously mentioned study, because for this experiment in our investigation the analyzed specimens had been fed only with sterile agar.

Our microscopical analysis confirms the finding of a previous report that in the midgut a peritrophic membrane layer exists between the gut epithelium and the food bolus (39). Such peritrophic membranes, which commonly occur in more highly evolved insects, are considered to protect the midgut epithelium from abrasion and act as a barrier to prevent microbial infections (8, 59). In our investigation, several regions of the peritrophic membrane were densely, as in a biofilm, colonized by bacterial cells. Similar colonizations have been found for the peritrophic membranes of the house cricket, Acheta domestica (79), and termites (9). Because the peritrophic membrane is not permeable for particles of the sizes of bacterial cells (59), the origin of bacterial colonization is still unclear to us. SEM analysis of F. candida feces showed that the peritrophic membrane was excreted and thus that associated bacteria are also transported to the outside of the insect. Differential staining techniques of fecal bacteria in our study indicated that a large proportion of fecal bacteria was viable but not culturable by the selected cultivation technique. Possibly, these cells originated from the peritrophic membrane. Nonculturable bacterial cells have been found on the epithelia of the hepatopancreases of the isopods Oniscus asellus and Porcellio scaber (85).

To understand the specific conditions which exist for microbial communities in the guts of collembolans, it is important to consider that molting occurs frequently throughout the entire life cycles of these insects. For F. candida the period from one instar to the next lasted approximately 4 days, as was detected in our own investigation, and in a more detailed fashion, in another study (68). During the molting process, the whole cuticle, including the fore- and hindgut as well as the midgut epithelium, is completely regenerated. While occupied with molting, the insects stop feeding, possibly because gut conditions are not suitable for digestion processes (42, 75). This phenomenon resulted in approximately 20% nonfeeding specimens in our microcosms and in the gene transfer studies described in the accompanying paper (38). The number of cultured gut bacteria was relatively constant (approximately 105 CFU per specimen) when the insects were feeding but ranged over 4 orders of magnitude, with titers from 102 to 106 CFU per specimen, when molting specimens were analyzed. Thus, the gut represented a highly changeable habitat for microorganisms and, since there was considerable growth of bacterial populations every 4 days, the bacteria that inhabit the gut should be in a metabolically active state.

The diversity of bacteria isolated from the gut of F. candida onto a nonselective growth agar is remarkable, especially if one considers that the analyzed specimens originated from breeding stocks which were not kept under sterile conditions but which were fed for 2 years with sterile substrates (autoclaved brewer’s yeast). A total of 11 different types of bacteria were isolated. In the accompanying paper, another 15 strains, all of which were gram-negative members of the class Proteobacteria, were isolated under more stringent conditions from the same environment (38). In this study, two types of bacteria accounted for more than 80% of the isolates, but it has to be recognized that cultivation-dependent methods do not necessarily reflect actual quantitative relationships in natural microbial communities (83). However, it is noteworthy that the most dominant isolate was closely related to the fire blight-causing plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora (7). In contrast to the diversity of bacteria isolated, only one fungus, Acremonium charticola, was isolated. According to the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, this species has been isolated from a large variety of different environmental samples, most of which had cellulose as a substrate (17). Since F. candida naturally feeds on cellulose-containing substrates, we suppose it would be advantageous for the insects if cellulose-degrading microorganisms lived in their guts. The symbiotic effect of chitin-degrading bacteria in the gut of F. candida has been shown in another study (10).

The diversity of bacteria, as well as the feeding preference of F. candida for its own gut bacteria, which we detected in pairwise choice tests with a selection of bacterial species, indicated that F. candida harbored a specific gut microbial community. The most convincing support for this hypothesis, however, was obtained by feeding marker-gene-selected bacterial strains to F. candida and monitoring the selective activity of the gut environment imposed onto these ingested cells. By this means we were able to determine that indigenous gut isolates were able to colonize this environment but that other species, like E. coli, were eliminated very efficiently. The gut passage in F. candida lasted only 35 min. Gorbenko et al. (30) found that the gut passage of ingested material in wood lice and millipeds lasted for 15 to 18 h and in earthworms lasted for approximately 5 h. The selective force imposed upon ingested cells by the gut passage in F. candida must have been very strong. E. coli cell populations decreased by over 60,000-fold within this short period, but the ingested, gut-isolated strain A. faecalis HR4 decreased only 500-fold. Considering the differential persistence of these two strains in the gut, the differences in their levels of selection by F. candida become even more drastic. Other studies with invertebrates confirm that some ingested bacteria can persist in the gut and that others are digested efficiently, depending on the species (3, 18, 52, 54, 55). This activity modifying the composition of mixed microbial populations must also be considered when the potential environmental spread of genetically engineered or pathogenic microorganisms is assessed (1, 2, 14, 20, 24, 26, 36, 37, 78). The physiological capacities which decide whether a bacterial species is capable of colonizing a gut habitat or whether it is eliminated might correlate with the ability to attach to the gut epithelium, preferentially in the hindgut region (3, 21, 32), but there may also be other, not yet characterized mechanisms of gut colonization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Claudia Wahrenburg for her excellent technical assistance, Rona Miethling for helping with FAME analyses, and E. R. B. Moore for 16S rRNA database information. We are also grateful to Ute Menge-Hartmann, who introduced us to techniques in SEM. We thank Andrea Güttler, V. Farelly, A. Pühler, and J. Schiemann for providing bacterial strains.

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF; grant 0310664).

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong J L, Knudsen G R, Seidler R J. Microcosm method to assess survival of recombinant bacteria associated with plants and herbivorous insects. Curr Microbiol. 1987;15:229–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong J L, Porteous L A, Wood N D. The cutworm Peridroma saucia (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) supports growth and transport of pBR322-bearing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2200–2205. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.9.2200-2205.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin D A, Baker J H. Fate of bacteria ingested by larvae of the freshwater mayfly, Ephemera danica. Microb Ecol. 1988;15:323–332. doi: 10.1007/BF02012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakonyi G. Effect of Folsomia candida (Collembola) on the microbial biomass in a grassland soil. Biol Fertil Soils. 1989;7:138–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardgett R D, Griffiths B S. Ecology and biology of soil protozoa, nematodes and microarthropods. In: van Elsas J D, Trevors J T, Wellington E M H, editors. Modern soil microbiology. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1997. pp. 129–163. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bengtsson G, Erlandsson A, Rundgren S. Fungal odour attracts soil collembola. Soil Biol Biochem. 1988;20:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bereswill S, Bugert P, Bruchmüller I, Geider K. Identification of the fire blight pathogen, Erwinia amylovora, by PCR assays with chromosomal DNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2636–2642. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2636-2642.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bignell D E. The arthropod gut as an environment for microorganisms. In: Anderson J M, Rayner A D M, Walton D W H, editors. Invertebrate-microbial interactions. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bignell D E, Oskarsson H, Anderson J M. Colonization of the epithelial face of the peritrophic membrane and the ectoperitrophic space by actinomycetes in a soil-feeding termite. J Invertebr Pathol. 1980;36:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borkott H, Insam H. Symbiosis with bacteria enhances the use of chitin by the springtail, Folsomia candida (Collembola) Biol Fertil Soils. 1990;9:126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breznak A. Intestinal microbiota of termites and other xylophagous insects. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1982;36:323–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.36.100182.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bromfield E S P, Wheatcroft R, Barran L R. Medium for direct isolation of Rhizobium meliloti from soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 1994;26:423–428. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown G G. How do earthworms affect microfloral and faunal community diversity? Plant Soil. 1995;170:209–231. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byzov B A, Claus H, Tretyakova E B, Zvyagintsev D G, Filip Z. Effects of soil invertebrates on the survival of some genetically engineered bacteria in leaf litter and soil. Biol Fertil Soils. 1996;23:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson C A, Pierson L S, Rosen J J, Ingraham J L. Pseudomonas stutzeri and related species undergo natural transformation. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:93–99. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.93-99.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cazemier A E, Hackstein J H P, Op den Camp H J M, Rosenberg J, van der Drift C. Bacteria in the intestinal tract of different species of arthropods. Microb Ecol. 1997;33:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s002489900021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. 1997. http://www.cbs.knaw.nl.

- 18.Chapco W, Kelln R A. Persistence of ingested bacteria in the grasshopper gut. J Invertebr Pathol. 1994;64:149–150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christen A A. Some fungi associated with Collembola. Rev Ecol Biol Sol. 1975;12:723–728. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clegg C D, van Elsas J D, Anderson J M, Lappin-Scott H M. Assessment of the role of a terrestrial isopod in the survival of a genetically modified pseudomonad and its detection using the polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;15:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clegg C D, Anderson J M, Lappin-Scott H M. Biophysical processes affecting the transit of a genetically-modified Pseudomonas fluorescens through the gut of the woodlouse Porcellio scaber. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:997–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman D C, Ingham R E, McClellan J F, Trofymow J A. Soil nutrient transformations in the rhizosphere via animal-microbial interactions. In: Anderson J M, Rayner A D M, Walton D W H, editors. Invertebrate-microbial interactions. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruden D L, Markovetz A J. Microbial ecology of the cockroach gut. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:617–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daane L L, Molina J A E, Sadowsky M J. Plasmid transfer between spatially separated donor and recipient bacteria in earthworm-containing soil microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:679–686. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.679-686.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jacubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dighton J, Jones H E, Robinson C H, Beckett J. The role of abiotic factors, cultivation practices and soil fauna in the dispersal of genetically modified microorganisms in soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 1997;5:109–131. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elkins M Z, Whitford W G. The role of microarthropods and nematodes in decomposition in semi-arid ecosystems. Oecologia. 1982;55:303–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00376916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furukawa K, Miyazaki T. Cloning of a gene cluster encoding biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:392–398. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.392-398.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furukawa K, Hayashida S, Taira K. Biochemical and genetic basis for the degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls in soil bacteria. In: Galli E, Silver S, Witholt B, editors. Pseudomonas: molecular biology and biotechnology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorbenko A Y, Panikov N S, Zvyagintsev D G. Effect of invertebrates on growth of soil bacteria. Mikrobiologya. 1986;55:515–521. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goto H E. Simple techniques for the rearing of collembola and a note on the use of a fungistatic substance in the cultures. Entomol Mon Mag. 1960;46:138–140. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffiths B S, Wood S. Microorganisms associated with the hindgut of Oniscus asellus (Crustacea, Isopoda) Pedobiologia. 1985;28:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanlon R D G. Some factors influencing microbial growth on soil animal faeces. II. Bacterial and fungal growth on soil animal faeces. Pedobiologia. 1981;21:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris J M. The presence, nature, and role of gut microflora in aquatic invertebrates: a synthesis. Microb Ecol. 1993;25:195–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00171889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haugland R P. Handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals. In: Spence M T Z, editor. Molecular probes. 6th ed. Leiden, The Netherlands: Molecular Probes, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendriksen N B. Effects of detritivore earthworms on dispersal and survival of the bacterium Aeromonas hydrophila. Acta Zool Fenn. 1995;196:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henschke R B, Nücken E, Schmidt F R J. Fate and dispersal of recombinant bacteria in a soil microcosm containing the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris. Biol Fertil Soils. 1989;7:374–376. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffmann A, Thimm T, Dröge M, Moore E R B, Munch J C, Tebbe C C. Intergeneric transfer of conjugative and mobilizable plasmids harbored by Escherichia coli in the gut of the soil microarthropod Folsomia candida (Collembola) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2652–2659. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2652-2659.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humbert W. The midgut of Tomocerus minor Lubbock (Insecta, Collembola): ultrastructure, cytochemistry, ageing and renewal during a moulting cycle. Cell Tissue Res. 1979;196:39–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00236347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunt H W, Coleman D C, Ingham R E, Elliott E T, Moore J C, Rose S I, Reid C P P, Morely C K. The detrital food web in a shortgrass prairie. Biol Fertil Soils. 1987;3:17–68. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ineson P, Anderson J M. Aerobically isolated bacteria associated with the gut and faeces of the litter feeding macroarthropods Oniscus asellus and Glomeris marginata. Soil Biol Biochem. 1985;17:843–849. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joosse E N G, Testerink G J. The role of food in the population dynamics of Orchesella cincta (Linné) (Collembola) Oecologia. 1977;29:189–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00345694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karnovsky M J. A formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolarity for use in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1965;27:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lagerlöf J, Andrén O. Abundance and activity of collembola, protura and diplura (Insecta, Apterygota) in four cropping systems. Pedobiologia. 1991;35:337–350. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Q, Widden P. Folsomia candida, a “fungivorous” collembolan, feeds preferentially on nematodes rather than soil fungi. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:689–690. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lingappa Y, Lockwood J L. Chitin media for selective isolation and culture of actinomycetes. Phytopathology. 1962;52:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall V G, Kevan D K M. Preliminary observations on the biology of Folsomia candida Willem, 1902 (Collembola: Isotomidae) Can Entomol. 1962;94:575–586. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mead L J, Khachatourians G G, Jones G A. Microbial ecology of the gut in laboratory stocks of the migratory grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes (Fab.) (Orthoptera: Acrididae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1174–1181. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.5.1174-1181.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller L, Berger T. Hewlett-Packard Applied Note 43-5953-1838. Palo Alto, Calif: Hewlett-Packard; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore J C. The influence of microarthropods on symbiotic and non-symbiotic mutualism in detrital-based below ground food webs. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1988;24:147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morita R Y. The starvation-survival of microorganisms in nature and its relationship to the bioavailable energy. Experientia. 1990;46:813–817. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parker M D, Akey D H, Lauerman L H. Persistence of enterobacteriaceae in female adults of the biting gnat Culicoides variipennis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) J Med Entomol. 1978;14:597–598. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/14.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pedersen J C, Hendriksen N B. Effect of passage through the intestinal tract of detrivore earthworms (Lumbricus spp.) on number of selected Gram-negative and total bacteria. Biol Fertil Soils. 1993;16:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plante C J, Jumars P A, Baross J A. Rapid bacterial growth in the hindgut of a marine deposit feeder. Microb Ecol. 1989;18:29–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02011694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plante C J, Mayer L M, King G M. The kinetics of bacteriolysis in the gut of the deposit feeder Arenicola marina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1051–1057. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1051-1057.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powers E M. Efficacy of the Ryu nonstaining KOH technique for rapidly determining Gram reactions of food-borne and waterborne bacteria and yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3756–3758. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3756-3758.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prosser J I. Microbial processes within the soil. In: van Elsas J D, Trevors J T, Wellington E M H, editors. Modern soil microbiology. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reyes V G, Tiedje J M. Ecology of the gut microbiota of Tracheoniscus rathkei (Crustacea, Isopoda) Pedobiologia. 1976;16:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richards A G, Richards P A. The peritrophic membranes of insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1977;22:219–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.22.010177.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schaaf O, Dettner K. Microbial diversity of aerobic heterotrophic bacteria inside the foregut of two tyrphophilous water beetle species (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) Microbiol Res. 1997;152:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seastedt T R. The role of microarthropods in decomposition and mineralization processes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1984;29:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Selbitschka W, Pühler A, Simon R. The construction of recA deficient Rhizobium meliloti and R. leguminosarum strains marked with gusA or luc cassettes for use in risk assessment studies. Mol Ecol. 1992;1:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Selbitschka W, Dresing U, Hagen M, Niemann S, Pühler A. A biological containment system for Rhizobium meliloti based on the use of recombination-deficient (recA−) strains. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;16:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seniczak S, Stefaniak O. The microflora of the alimentary canal of Oppia nitens (Acarina, Orbatei) Pedobiologia. 1978;18:110–119. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shaw N. Lipid compositions as a guide to the classification of bacteria. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1974;17:63–108. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shaw P J A. A consistent hierachy in the fungal feeding preferences of the collembola Onychiurus armatus. Pedobiologia. 1988;31:179–187. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snider R. Laboratory observations on the biology of Folsomia candida (Willem) (Collembola: Isotomidae) Rev Ecol Biol Sol. 1973;10:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spurr A R. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969;26:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stefaniak O, Seniczak S. The effect of fungal diet on the development of Oppia nitens (Acari, Orbatei) and on the microflora of its alimentary tract. Pedobiologia. 1981;21:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steinhaus E A. A study of the bacteria associated with thirty species of insects. J Bacteriol. 1941;42:757–790. doi: 10.1128/jb.42.6.757-790.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suarez A, Güttler A, Strätz M, Staendner L H, Timmis K N, Guzmán C A. Green fluorescent protein-based reporter systems for genetic analysis of bacteria including monocopy applications. Gene. 1997;196:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suyama K, Yamamoto H, Naganava T, Iwata T, Komada H. A plate count method for aerobic cellulose decomposers in soil by congo red staining. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1993;39:361–365. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teuben A, Roelofsma T A P J. Dynamic interactions between functional groups of soil arthropods and microorganisms during decomposition of coniferous litter in microcosm experiments. Biol Fertil Soils. 1990;9:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thibaud J-M. Relations chronologiques entre les cycles du tube digestif et de l’appareil génital lors de l’intermue des insectes collemboles. Rev Ecol Biol Sol. 1976;13:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thiele A, Larink O. Colour-marking in experiments on food selection with Collembola. Biol Fertil Soils. 1990;9:203–204. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tochot F, Kilbertus G, Vannier G. Rôle d’un collembole (Folsomia candida) au cours de la dégradation des litières de charme et de chêne, en présence ou en absence d’argile. In: Lebrun P, André H M, De Medts A, Grégoire-Wibo C, Wauthy G, editors. New trends in soil biology. Proceedings of the VIII. International Colloquium of Soil Zoology. Ottignies-Lovain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Imprimeur Dieu-Brichart; 1982. pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toyota K, Kimura M. Earthworms disseminate a soil-borne plant pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. raphani. Biol Fertil Soils. 1994;18:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ulrich R G, Buthala B A, Klug M J. Microbiota associated with the gastrointestinal tract of the common house cricket, Acheta domestica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:246–254. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.1.246-254.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vahjen W, Munch J C, Tebbe C C. Fate of three genetically engineered, biotechnologically important microorganism species in soil: impact of soil properties and intraspecies competition with nonengineered strains. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:827–834. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Van der Walt J P, Yarrow D. Methods for the isolation, maintenance, classification and identification of yeasts. In: Kreger-vanRij N J W, editor. The yeast—a taxonomic study. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1984. pp. 45–104. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vaneechoutte M, Roussau R, De Vos P, Gillis M, Janssens D, Paepe N, De Rouck A, Fiers T, Claeys G, Kersters K. Rapid identification of bacteria of the Comamonadaceae with amplified ribosomal DNA-restriction analysis (ARDRA) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;93:227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wagner M, Amann R, Lemmer H, Schleifer K-H. Probing activated sludge with oligonucleotides specific for proteobacteria: inadequacy of culture-dependent methods for describing microbial community structure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1520–1525. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1520-1525.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wolf M M, Rockett C L. Habit changes affecting bacterial composition in the alimentary canal of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) Int J Acarol. 1984;10:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wood S, Griffiths B S. Bacteria associated with the hepatopancreas of the woodlice Oniscus asellus and Porcellio scaber (Crustacea, Isopoda) Pedobiologia. 1988;31:89–94. [Google Scholar]