Abstract

This survey study assesses trends in nicotine use among young adults in the US between 2013 and 2021.

The prevalence of vaping nicotine has increased, especially among young adults, coinciding with newer salt-based nicotine devices, whereas smoking prevalence is decreasing.1 Historically, young adults have been important to the tobacco industry, forecasting future tobacco use.2 This study analyzes trends in young adult tobacco use over time.

Methods

We analyzed data from the US Food and Drug Administration Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study,3 a nationally representative, longitudinal survey (conducted from September 12, 2013, to November 30, 2021, and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board), in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and SUDAAN, version 11.0.3 (RTI International). Demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, educational level, and income), outcomes (established use of vaping and smoking), and cross-sectional weights, including corresponding replication weights (100 replication weights per person per wave), were calculated for all adult participants present in at least 1 wave. This survey study followed the AAPOR reporting guideline.

Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics (weighted frequencies by wave) and longitudinal models per outcome for young adults (aged 18-24 years). Longitudinal models used weighted generalized estimating equations with exchangeable working correlations, survey weights, balanced repeated replication with a Fay adjustment of 0.3 (adjfay = 2.040816) (per PATH), and variance estimates calculated with data from all adult participants.

Models included main effects for sex, race, ethnicity, educational level, and income. All models were adjusted for time (median month of data collection from wave 1 [0, 12, 24, 38, 60, and 87 months, respectively, for waves 1-6]). Interactions were included in initial models, determining whether use varied by race or sex over time. Final models were chosen by backward selection (2-sided P < .05). Interactions were considered for removal first, then main effects were considered for removal one at a time, and the model was refit until all remaining P values were below the nominal level.

Results

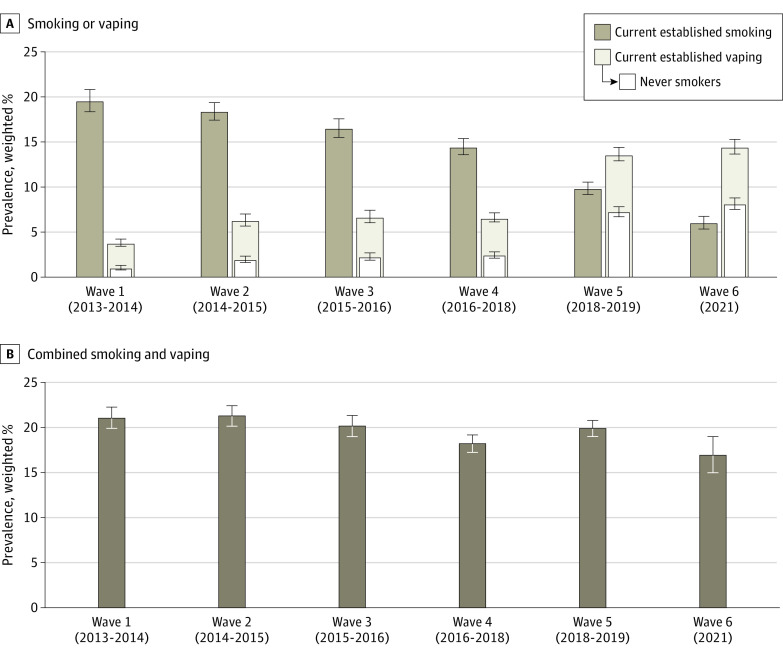

Ever-smoking prevalence decreased from 53.2% (wave 1) to 35.2% (wave 6), while ever e-cigarette use increased from 32.0% (wave 1) to 52.7% (wave 6). The prevalence of current established smoking decreased from 19.6% (wave 1) to 6.1% (wave 6), while current established vaping increased from 3.8% (wave 1) to 14.5% (wave 6) (Figure). The prevalence of those with current established vaping and who were never established smokers increased from 1.1% (wave 1; 27.9% of established vaping) to 8.1% (wave 6; 56.2% of established vaping). The rate of everyday e-cigarette use increased from 1.2% (wave 1) to 8.3% (wave 6). Both models retained all demographic variables as main effects. The sex × time interaction was significant for vaping (β = −0.07, F = 26.82, P < .001). Adjusted established vaping rates increased over time for both sexes, but rates started higher and increased less rapidly for men. Adjusted established smoking rates decreased over time (β = −0.08, F = 31.47, P < .001). No interactions were retained in the model for smoking.

Figure. Prevalence of Current Established Smoking and Vaping Among US Young Adults Aged 18 to 24 Years.

Sample sizes are as follows: wave 1: total sample = 32 320 and 18- to 24-year-old sample = 9109; wave 2: total sample = 28 362 and 18- to 24-year-old sample = 8173; wave 3: total sample = 28 148 and 18- to 24-year-old sample = 8452; wave 4: total sample = 33 644 and 18- to 24-year-old sample = 11 213; wave 5: total sample = 32 687 and 18- to 24-year-old sample = 11 355; and wave 6, total sample = 29 516 and 18- to 24-year-old sample = 10 633. Current established smoking data are for those who report smoking 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoke every day or some days. Current established vaping data are for those who report ever use of any electronic nicotine product, have ever used them fairly regularly, and currently use them every day or some days. The white bars indicate the prevalence of people who both never reported established smoking and currently reported established vaping. Combined use refers to anyone who endorsed current established cigarette and/or current established e-cigarette use. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

These data reveal a shift in tobacco use among young adults, showing historically low cigarette use, which has positive public health significance. However, e-cigarette use is higher (14.5%) than reported previously (11%),4 coinciding with the introduction of salt-based devices in 2015 to 2018. Over half of established vaping young adults never regularly smoked. Research suggests that exclusive e-cigarette users are unlikely to transition to combustible tobacco.5 This age range has historically been important to the tobacco industry as a time when tobacco users often transition to established use and brand loyalty,2 and these data may forecast a future in which e-cigarettes are the dominant tobacco product in the US. Limitations of this study include repeated cross-sectional samples of 18- to 24-year-olds, PATH survey response rate, and use of PATH definitions of established smoking and vaping.

E-cigarettes emit lower levels of toxicants and may result in population-level harm reduction, but they are not without risks. Treatments are lacking for e-cigarette users wishing to quit.6 Research should aim to further reduce the prevalence of smoking and create treatments for e-cigarette users wanting to quit nicotine altogether.6

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):397-405. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908-916. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services , National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products.Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. National Addiction and HIV Data Archive Program. May 19, 2023. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NAHDAP/studies/36231/versions/V36

- 4.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(18):475-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creamer MR, Dutra LM, Sharapova SR, et al. Effects of e-cigarette use on cigarette smoking among U.S. youth, 2004-2018. Prev Med. 2021;142:106316. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer AM, Price SN, Foster MG, Sanford BT, Fucito LM, Toll BA. Urgent need for novel investigations of treatments to quit e-cigarettes: findings from a systematic review. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2022;15(9):569-580. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-22-0172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement