Abstract

The yeast Candida utilis does not possess an endogenous biochemical pathway for the synthesis of carotenoids. The central isoprenoid pathway concerned with the synthesis of prenyl lipids is present in C. utilis and active in the biosynthesis of ergosterol. In our previous study, we showed that the introduction of exogenous carotenoid genes, crtE, crtB, and crtI, responsible for the formation of lycopene from the precursor farnesyl pyrophosphate, results in the C. utilis strain that yields lycopene at 1.1 mg per g (dry weight) of cells (Y. Miura, K. Kondo, T. Saito, H. Shimada, P. D. Fraser, and N. Misawa, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1226–1229, 1998). Through metabolic engineering of the isoprenoid pathway, a sevenfold increase in the yield of lycopene has been achieved. The influential steps in the pathway that were manipulated were 3-hydroxy methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, encoded by the HMG gene, and squalene synthase, encoded by the ERG9 gene. Strains overexpressing the C. utilis HMG-CoA reductase yielded lycopene at 2.1 mg/g (dry weight) of cells. Expression of the HMG-CoA catalytic domain alone gave 4.3 mg/g (dry weight) of cells; disruption of the ERG9 gene had no significant effect, but a combination of ERG9 gene disruption and the overexpression of the HMG catalytic domain yielded lycopene at 7.8 mg/g (dry weight) of cells. The findings of this study illustrate how modifications in related biochemical pathways can be utilized to enhance the production of commercially desirable compounds such as carotenoids.

The aim of metabolic engineering is defined as the purposeful modification of metabolic networks in living cells to produce desirable chemicals with superior yields and productivity by using recombinant DNA technologies (1, 18). Its main field should be investigations undertaken to produce chemicals of commercial interest efficiently and abundantly by using the appropriate microorganisms (8). It has traditionally been postulated that microbes naturally synthesizing desirable chemicals should be used as hosts. However, the use of suitable microorganisms which have the ability to produce the precursors for the desired chemicals with superior yields and at high levels of productivity is also feasible (14). This notion significantly extends the range of microbes utilizable as productive hosts. In order to achieve these objectives, three main research approaches are usually employed: (i) introducing exogenous genes, which convert the final precursor of a host organism to a desirable chemical, at a viable yield; (ii) enhancing the metabolic flux through a pathway to increase the synthesis of the final precursor (this may, for example, be achieved by amplifying rate-limiting reactions or eliminating mechanisms of feedback inhibition); and (iii) increasing precursors by minimizing metabolic flow to biosynthetically related products.

Lycopene is a red carotenoid pigment present in the tomato, watermelon, and red grapefruit. This pigment has recently attracted great attention, due to its beneficial effect on health. For example, lycopene has been shown to have preventive effects against certain cancers, e.g., prostate cancer (4). Lycopene is also said to be the most effective antioxidant (12).

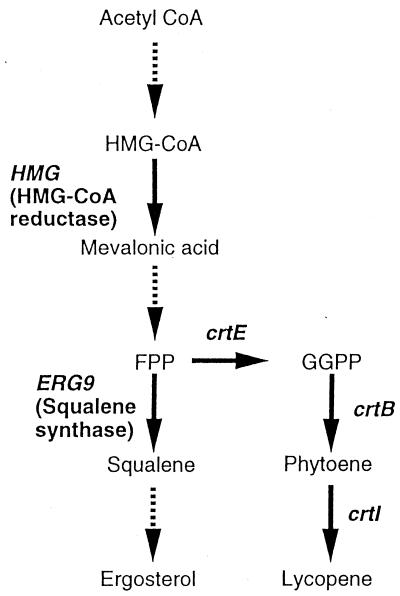

The objective of the present study was to produce, through a metabolic engineering approach, a microorganism giving a high yield of carotenoid. The yeast Candida utilis is an industrially important microorganism approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a safe substance. Through its large-scale production, C. utilis has become a promising source of single-cell protein as well as a host for the production of several chemicals, such as glutathione and RNA (3, 7). C. utilis does not synthesize carotenoid pigment but does accumulate large quantities of ergosterol (10 to 15 mg/g [dry weight] of cells). Like carotenoids, ergosterol is an isoprenoid, and it is biosynthetically related to them by a common prenyl lipid precursor, farnesyl diphosphate (FPP). Thus, although C. utilis does not form carotenoids, it does possess their potential precursors. By introducing the three carotenogenic genes (crtE, crtB, and crtI) required for lycopene synthesis from FPP under the control of C. utilis promoters, a C. utilis strain that produces 1.1 mg of lycopene per g (dry weight) of cells has been generated; the lycopene produced in C. utilis is a pure product (13) (Fig. 1). In the present study, we have applied concepts (ii) and (iii) of metabolic engineering described above to the yeast strain in order to redirect carbon flux away from ergosterol formation for potential utilization by the carotenoid pathway. The resultant strains producing high-yields of lycopene and possessing commercial potential are described and discussed.

FIG. 1.

Metabolic pathway of endogenous ergosterol biosynthesis and exogenous lycopene biosynthesis. The solid arrows show the one-step conversions of the biosynthesis, and the dashed arrows show the several steps. crtE, crtB, and crtI are the endogenous lycopene synthesis genes. GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

C. utilis ATCC 9950 was used in this study. Cells were cultured at 30°C in YPD medium (2% glucose, 1% Bacto Yeast Extract, 2% Bacto Peptone). Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a host for plasmid construction (17).

Molecular cloning techniques.

The construction of the C. utilis genomic DNA library has been previously described by Kondo et al. (10). Colony hybridization and Southern hybridization were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (17). In order to obtain fragments containing either the HMG or ERG9 gene, PCRs were performed with C. utilis genomic DNA as a template. The oligonucleotides HMG1-5′ (5′-GGTGAYGCHATGGGTATGAACAT-3′) and HMG1-3′ (5′-GTACCVACCTCGATNWSTGGCAT-3′) were used for amplifying the HMG gene. The nucleotide sequence of primer HMG1-5′ was deduced from the amino acid sequence between +807 and +814 of the HMG1 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the nucleotide sequence of primer HMG1-3′ was deduced from the amino acid sequence between +951 and +958 of the HMG1 protein of S. cerevisiae. PCR was carried out with a LA PCR kit, version 2 (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Kusatsu, Japan). The amplified DNA fragments were sequenced and analyzed by the protocol provided with the ABI PRISM cycle sequencing kits. The PCR products were used as probes for colony hybridization and Southern hybridization. The clone obtained did not encode the 3′ region of the HMG gene. To obtain the 3′ region of the HMG gene, PCR was performed with the following primers: HMG-3-1 (5′-GGGGAATTCAAGAAAGCCTTCAACTCTACTTCCAGATTT-3′) and pBR322-3′ (5′-TGATGCCGGCCACGATGCGTCCGGCGTAGA-3′). Primer HMG-3-1 contained the nucleotide sequence between +2023 and +2061 of the C. utilis HMG gene, and primer pBR322-3′ contained the nucleotide sequence of pBR322. The C. utilis genomic library which was constructed in pBR322 (10) was used as a template.

In order to obtain a probe for cloning the ERG9 gene, PCR was performed with C. utilis genomic DNA as a template. The oligonucleotides ERG9-5′ (5′-TTYSTNCARAAGACNAACATCAT-3′) and ERG9-3′ (5′-ATVACYTGTGGGATDGCACARAA-3′) were used as PCR primers. The nucleotide sequence of primer ERG9-5′ was deduced from the amino acid sequence between +217 and +224 of the ERG9 protein of S. cerevisiae, and the nucleotide sequence of primer ERG9-3′ was deduced from the amino acid sequence between +295 and +302 of the S. cerevisiae ERG9 protein. The amplified DNA fragments were analyzed, and the DNA fragments were used as a probe for cloning the ERG9 gene.

Construction of an HMG overexpression vector and an ERG9 disruption vector.

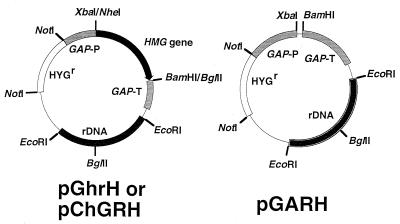

Plasmid pGhrH, used for overexpression of the HMG gene, was constructed as follows. The oligonucleotides F-HMG-5′ (5′-GGGGCTAGCATGTTCTACCACGGTGCAAGCGCAAACCAA-3′) and F-HMG-3′ (5′-GGGAGATCTTGCTTATTTCTTAGCAGCGGCTCTGTTGTG-3′) were used as PCR primers for amplifying the HMG gene in C. utilis. Primer F-HMG-5′ corresponded to the sequence between +1 and +30 of the HMG gene, and primer F-HMG-3′ corresponded to the sequence between +2779 and +2805 of the HMG gene. C. utilis genomic DNA was used as the template for PCR. The PCR products were digested by NheI and BglII and ligated between the XbaI and BamHI sites of pGAPPT10, which contains the GAP promoter and terminator (17). The plasmid was designated pGh. The 1.2-kb EcoRI fragment of plasmid pCLRE2 containing C. utilis ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (10) was ligated into the EcoRI site of pGh, and the resulting plasmid was designated pGhr. The 3.2-kb NotI fragment containing an expression cassette of the hygromycin B (HYG) phosphotransferase gene (HPT) was isolated from pGKHPT1 and inserted at the NotI site of pGhr to construct the plasmid pGhrH. pGKHPT1 was constructed as follows. The HPT gene was obtained by PCR with the 5′ primer 5′-GGTCTAGATATGAAAAAGCCTGAAC-3′ and the 3′ primer 5′-GGAGATCTATTCCTTTGCCCTCGGA-3′. Plasmid pBIB-HYG (2) was used as a template for PCR. The PCR products were digested with XbaI and BglII and then ligated between the XbaI and BamHI sites, which contain PGK promoter and terminator fragments.

Plasmid pChGRH, used for the expression of a truncated form of the HMG gene, was constructed as follows. The oligonucleotides T-HMG-5′ (5′-GGGGCTAGCATGATCCATACCACAAGATTGGAGGATGCAATC-3′) and T-HMG-3′ (5′-GGGAGATCTTGCTTATTTCTTAGCAGCGGCTCTGTTGTG-3′) were used as primers for PCR. Primer T-HMG-5′ corresponded to the sequence between +1339 and +1368 of the HMG gene, and primer T-HMG-3′ corresponded to the sequence between +2779 and +2805 of the HMG gene. Genomic DNA from C. utilis was used as the template for PCR. The PCR products were digested with NheI and BglII and ligated between the XbaI and BglII sites of the plasmid pGAPPT10 to construct plasmid pChG. The 1.2-kb EcoRI fragment of rDNA and the 3.2-kb NotI fragment of the HPT gene expression cassette were ligated into the EcoRI site of pChG to construct pChGRH. Plasmid pGARH, which we used as a control, was constructed by inserting the EcoRI fragment of rDNA and the NotI fragment of the HPT gene at the EcoRI and NotI sites of pGAPPT10.

Plasmid p8EBN8 · G4, used for disruption of the ERG9 gene, was constructed as follows. Plasmid p8EB9 was constructed by subcloning a 2.0-kb EcoT221-BamHI fragment containing the full-length ERG9 gene between the PstI and BamHI sites of pUC18. Plasmid p8EBN8 was constructed by inserting a NotI linker into the BglII site at +722 of the ERG9 gene of p8EB9 after treating the BglII site with T4 DNA polymerase. Plasmid p8EBN8 · G4 was constructed by ligation of the 2.5-kb NotI fragment containing a G418 (Geneticin) resistance gene expression cassette of pGKAPH3 into the NotI site of p8EBN8.

Transformation of C. utilis.

Yeast transformations were carried out by electroporation as described by Kondo et al. (10) with a slight modification: the incubation of the cells in YPD medium after the pulse was extended to 12 h instead of 6 h. Plasmids were used for transformation after they were linearized by restriction enzyme digestion. The plasmids phmrDH, pChGRH, and pGhrH were digested with BglII, and plasmid p8EBN8 · G4 was digested with BamHI and SphI. The transformed cells were grown in YPD medium containing appropriate antibiotics (200 μg of G418/ml, 40 μg of cycloheximide [CYH]/ml, and 800 μg of HYG/ml).

Measurements of lycopene and ergosterol contents.

Lycopene and ergosterol were extracted from yeast cells as described previously (19). The extracted lycopene and ergosterol were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography as follows: the column (3.9 by 300 nm; Nova-pak HR 6 μ C18; Waters) was developed with acetonitrile–methanol–2-propanol (90:6:4) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and on-line spectra were recorded with a Waters photodiode array detector 996. The precise amounts of ergosterol and lycopene in the samples were determined by comparison to known amounts of standard compounds chromatographed under identical conditions.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence accession numbers for the HMG-CoA reductase gene (HMG) and the squalene synthase gene (ERG9) are ABO12603 and ABO12604, respectively.

RESULTS

Cloning of the HMG and ERG9 genes.

Genes encoding HMG-CoA reductase (HMG) have been cloned and sequenced from various organisms (6). Comparison of the known amino acid sequences indicated that HMG proteins share highly conserved amino acid sequences at their carboxyl termini. From the conserved regions, the mixed oligonucleotide primers (HMG-1-5′ and HMG1-3′; see Materials and Methods) were synthesized and used as primers for PCR. Sequence analysis of the amplified fragments indicated strong similarities (72.4% identity in the deduced amino acid sequence) to the known HMG1 gene in S. cerevisiae. The DNA fragment was used as a probe for Southern hybridization and colony hybridization. The HMG gene in C. utilis consists of a 2,805-bp open reading frame (ORF) and encodes a polypeptide of 935 amino acids; the deduced amino acid sequence had 52.2% identity with that of HMG-CoA reductase encoded by the HMG1 gene of S. cerevisiae (data not shown). Hydrophobicity analysis of the amino acid sequence of C. utilis HMG protein indicated that it contained seven putative membrane-spanning regions in the amino-terminal region between residues 1 and 476 (data not shown). It has been shown that the HMG1 protein of S. cerevisiae contains seven membrane-spanning domains at the amino terminus, and the stability of the protein is controlled by protease attack upon these domains (6). The carboxyl-terminal region of the HMG1 protein is considered to be the catalytic domain. The region between residues 477 and 935 of the C. utilis HMG protein exhibited 75.5% identity with the HMG1 protein of S. cerevisiae.

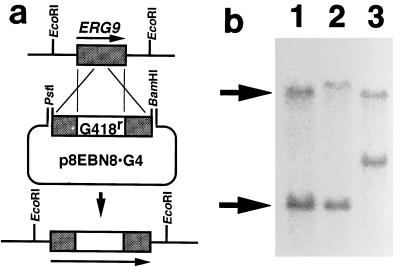

An approach similar to that used to clone the HMG gene was used to isolate the C. utilis squalene synthase gene (ERG9). From the conserved regions of the isolated ERG9 gene (9, 16), the mixed oligonucleotide primers were synthesized and used as primers for PCR (see Materials and Methods). Sequence analysis of the amplified fragments indicated that the sequence of the DNA fragment had high similarity to the ERG9 genes isolated in S. cerevisiae (72.9% identity in the deduced amino acid sequences). The DNA fragment was used as a probe for Southern hybridization or colony hybridization. An ERG9 gene of C. utilis was cloned, and its sequence was determined. The ERG9 gene consisted of a 1,320-bp ORF and a 63-bp intron. The ERG9 gene encoded a polypeptide of 440 amino acids that had 60.0% identity with that of the squalene synthase of S. cerevisiae (data not shown). Southern hybridization showed that the genomic DNA digested with BamHI and HindIII yielded a single band hybridized to the ERG9 gene probe DNA (data not shown). However, when the genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI, two bands were observed in the analysis. The sequence analysis of the ERG9 gene indicated that there is no EcoRI site in the ORF or intron. These results suggested that C. utilis has two copies of the ERG9 gene, as C. utilis is diploid. The ERG9 gene copies were encoded by 5.0- and 17.0-kb EcoRI fragments, respectively, in the C. utilis genome.

Increase of lycopene content by overexpression of the HMG gene.

Production of lycopene in C. utilis was achieved by expressing the lycopene biosynthesis genes, crtE, crtB, and crtI. The lycopene content of the resulting strain (strain 12-2) was 1.1 mg per g (dry weight) of cells (14). Previous studies have indicated that HMG-CoA reductase is a key enzyme involved in ergosterol biosynthesis in yeast (5, 6) (Fig. 1). Therefore, the plasmids phmrDH, containing the full-length HMG gene, and pChGRH, containing a portion of the gene (between +1339 and +2805) encoding the catalytic domain of the HMG protein, were constructed (Fig. 2). Plasmid pGAPRH, containing no HMG gene, was used as a control plasmid. These plasmids were used for transformation of the lycopene-producing strain 12-2 after the plasmids were cut with BglII. The transformants were cultured in YPD medium containing CYH and HYG for 2 days at 30°C (see Fig. 4). In the stationary phase, the lycopene content of C-1, a strain carrying the control plasmid pGAPRH, was almost the same as that of the control strain, 12-2 (Table 1). The lycopene content of FHL strains, carrying the full-length HMG gene, was 2.1 mg per g (dry weight) of cells, while in THL strains, carrying the truncated HMG gene, the lycopene content was 4.3 mg per g (dry weight) of cells. Thus, compared to the control strain (12-2), two- and fourfold increases in lycopene content were achieved. The ergosterol contents of C-1, FHL, and THL were almost the same as that of the control strain, 12-2 (Table 1). These results indicated that the overexpression of the HMG gene under the control of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate reductase gene (GAP) promoter was effective in increasing the accumulation of lycopene in C. utilis and that the expression of the catalytic domain of the HMG protein alone was more effective than that of the full-length protein.

FIG. 2.

Structures of plasmids used for HMG gene overexpression. Plasmids pGhrH and pChGRH have the full-length HMG gene and the truncated HMG gene, respectively. GAP-P, promoter of the gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GAP-T, terminator of the gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HYGr, HYG phosphotransferase gene.

FIG. 4.

Strains of C. utilis harboring various vectors. (A) Wild-type strain of C. utilis; (B) control strain carrying only lycopene synthesis genes (crtE, crtB, and crtI); (C) strain carrying lycopene synthesis genes and plasmid pChGRH (the truncated HMG expression vector); (D) strain carrying lycopene synthesis genes, plasmid pChGRH, and disrupted ERG9.

TABLE 1.

Lycopene and ergosterol contents of strains carrying various HMG and ERG9 constructs

| Strain | Descriptiona | Lycopene contentb (mg/g [dry weight] of cells) | Ergosterol contentc (mg/g [dry weight] of cells) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0988 | Wild type | NAd | 13.2 |

| 12-2 | 1.1 | 6.4 | |

| C-1 | Carrying no HMG | 1.5 | 6.8 |

| FHL | Carrying full-length HMG | 2.1 | 6.4 |

| THL | Carrying truncated HMG | 4.3 | 6.5 |

| LDL | Disrupted upper ERG9 | 1.0 | 8.5 |

| UDL | Disrupted lower ERG9 | 1.4 | 5.5 |

| ehL-1 | Carrying truncated HMG and disrupted lower ERG9 | 7.8e | 6.7 |

| ehL-2 | Same as ehL-1 | 6.5e | 6.5 |

All strains carry the lycopene synthesis genes, crtE, crtB, and crtI, except the wild-type strain, 0988.

Average of two independent clones (except strains ehL-1 and ehL-2). Standard deviations are all <0.2 mg per g (dry weight) of cells.

Average of three independent assays. Standard deviations are all <0.1 mg per g (dry weight) of cells.

NA, not assayed.

Average of three independent assays.

Effect of ERG9 disruption on lycopene content.

Farnesyl pyrophosphate is the precursor diverted from the endogenous C. utilis isoprenoid pathway into the engineered pathway for lycopene formation. It is also the substrate for squalene synthase, the formation of squalene being the first step committed in ergosterol biosynthesis (Fig. 1). In order to increase the carbon flux towards lycopene biosynthesis, disruption of the ERG9 gene encoding squalene synthase was conducted. Plasmid p8EBN8 · G4 was used to disrupt the ERG9 gene; the gene was divided by an insertion of the expression cassette of the G418r gene (Fig. 3a). Strain 12-2 was transformed with p8EBN8 · G4, and Southern analysis of the transformants indicated that each of the two copies of the ERG9 gene was disrupted by homologous recombination (Fig. 3b). The strains in which disruption of the ERG9 gene had occurred within the 5.0- and 17.0-kb EcoRI fragments were designated “Lower Disruption” and “Upper Disruption,” respectively. The transformants were cultured in YPD medium containing CYH and G418 for 2 days at 30°C (Fig. 4). The growth rates of strains with the disrupted ERG9 genes were virtually the same as that of the control strain, 12-2 (data not shown). In the stationary phase, the lycopene contents of UDL (Upper Disruption and lycopene synthesis) strains were slightly increased (1.4 mg per g [dry weight] of cells) compared to that of the control strain, 12-2 (1.1 mg per g [dry weight] of cells). However, the lycopene contents of LDL (Lower Disruption and lycopene synthesis) strains were almost the same (1.0 mg per g [dry weight] of cells) as that of the control strain. The ergosterol contents of UDL strains were almost identical (5.5 mg per g [dry weight] of cells) to that of the control strain (6.4 mg per g [dry weight] of cells), but the ergosterol contents of LDL strains were increased (8.5 mg per g [dry weight] of cells).

FIG. 3.

Genomic Southern hybridization of strains with disrupted ERG9. (a) Schematic representation of the disruption of ERG9 by the plasmid p8EBN8 · G4. (b) Genomic Southern hybridization. Lane 1, wild type; lane 2, Upper Disruption strain; lane 3, Lower Disruption strain. The upper and lower arrows indicate the 17.0- and 5.0-kb bands, respectively. All genomic DNAs were digested by EcoRI.

Effect of ERG9 gene disruption and HMG gene overexpression on lycopene content.

In order to assess the effect of the lower ERG9 gene disruption and the HMG gene overexpression in combination, plasmid pChGRH, containing the truncated form of the HMG gene, was introduced into the strain (Lower Disruption) in which the 5.0-kb EcoRI fragment of the ERG9 gene was disrupted. The transformants obtained were further transformed with plasmid pCLR1EBI, containing the lycopene synthesis genes, crtE, crtB, and crtI (14). Two clones, ehL-1 and ehL-2, were obtained, and the transformants were cultured in YPD medium containing CYH, HYG, and G418 for 3 days at 30°C (Fig. 4). In the stationary phase, the lycopene contents of ehL-1 and ehL-2 were 7.8 and 6.5 mg per g (dry weight) of cells, respectively (Table 1). The ergosterol contents of strains ehL-1 and ehL-2 were almost the same as those of strains FHL and THL. Thus, a fourfold increase in lycopene was achieved by the combination of ERG9 gene disruption and HMG gene overexpression compared to that achieved by HMG gene overexpression alone, and compared to the lycopene content of strain 12-2, a sevenfold increase was achieved.

DISCUSSION

C. utilis HMG-CoA reductase is similar to other HMG-CoA reductases, with the amino terminus containing seven diversified membrane-spanning domains and a highly conserved domain at the carboxyl terminus. It is this extremely conserved domain that has been shown to be responsible for catalytic activity in most organisms (6). Formation of HMG-CoA reductase is a highly regulated enzymatic step in animal and fungal isoprenoid biosynthesis, i.e., regulation occurs at transcriptional, posttranscriptional, and posttranslational levels (5, 6). It can be postulated that due to these regulatory mechanisms an additional copy of the HMG-CoA reductase in the cell would also be regulated and its action would be controlled in such a manner that the overall flux through the pathway would not be significantly altered. However, in C. utilis carrying the HMG gene overexpression vector, the exogenous HMG gene transcriptional regulation may not function because the exogenous HMG gene is transcribed by the GAP promoter. The posttranslational regulation of the truncated HMG gene may also not be functional because the membrane-spanning region which is concerned with stability in vivo was deleted. The increase in the lycopene contents of the strains carrying the full-length HMG gene and those strains carrying the truncated HMG gene reflect the possible absence of transcriptional, posttranscriptional, and posttranslational regulation.

In order to increase the carbon flux into lycopene biosynthesis, we attempted to decrease squalene synthase activity by disruption of the ERG9 gene encoding squalene synthase. Strains with disrupted ERG9 genes (Upper Disruption and Lower Disruption) were obtained by the introduction of the ERG9 disruption vector, p8EBN8 · G4, into the strains carrying the lycopene synthesis genes. Neither ERG9 gene disruption alone changed the lycopene contents. Presumably, the second endogenous C. utilis ERG9 gene, which was not disrupted, can compensate for the loss of the first gene product. To a certain extent this is understandable, as the total loss of squalene formation, and thus of ergosterol, would be lethal.

In the sterol biosynthesis pathway, there are regulation steps other than HMG-CoA reductase. For example, HMG-CoA synthase is regulated by the end product in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway (5). It is possible that HMG-CoA synthase might be regulated in the strains carrying the HMG gene overexpression vector. In the lycopene production strain with HMG gene overexpression, ergosterol as well as lycopene content may be increased. The elevation of the ergosterol content might reduce HMG-CoA synthase activity by feedback regulation. This could provide an explanation of why expression of the ERG9 gene and the HMG gene in combination was so effective compared to HMG gene expression alone.

This study reports the first successful application of metabolic engineering to the production of carotenoid pigments. Although lycopene synthesis genes have been used in this study, the formation of β-carotene and astaxanthin in C. utilis has also been achieved (14). The application of metabolic modification to these strains will hopefully increase their contents of these commercially desirable carotenoids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey J E. Toward a science of metabolic engineering. Science. 1991;252:1668–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.2047876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker D. Binary vectors which allow the exchange of plant selectable markers and reporter gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:203. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boze H, Moulin G, Galzy P. Production of food and fodder yeasts. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1992;12:65–86. doi: 10.3109/07388559209069188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm E B, Stampfer M J, Colditz G A, Willet W C. Intake of carotenoids and retinol in relation to risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein J L, Brown M S. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–430. doi: 10.1038/343425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hampton R, Dimster-Denk D, Rine J. The biology of HMG-CoA reductase: the pros of contra-regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:140–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ichi T, Takenaka S, Konno H, Ishida T, Sato H, Suzuki A, Yamazuki K. Development of a new commercial-scale airlift fermentor for rapid growth of yeast. J Ferment Bioeng. 1993;75:375–379. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda M, Katsumata R. Metabolic engineering to produce tyrosine or phenylalanine in a tryptophan-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:781–785. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.781-785.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings S M, Tsay Y H, Fisch T M, Robinson G W. Molecular cloning and characterization of the yeast gene for squalene synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6038–6042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo K, Saito T, Kajiwara S, Takagi M, Misawa N. A transformation system for the yeast Candida utilis: use of a modified endogenous ribosomal protein gene as a drug-resistant marker and ribosomal DNA as an integration target for vector DNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7171–7177. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7171-7177.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo K, Miura Y, Sone H, Kobayashi K, Iijima H. High-level expression of a sweet protein, monellin, in the food yeast Candida utilis. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nbt0597-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miki W. Biological functions and activities of animal carotenoids. Pure Appl Chem. 1991;63:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura, Y., K. Kondo, H. Shimada, T. Saito, K. Nakamura, and N. Misawa. Production of lycopene by the food yeast Candida utilis that naturally synthesize no carotenoids. Biotechnol. Bioeng., in press. [PubMed]

- 14.Miura Y, Kondo K, Saito T, Shimada H, Fraser P D, Misawa N. Production of the carotenoids lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin in the food yeast Candida utilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1226–1229. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1226-1229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murdock D, Ensley B D, Serdar C, Thalen M. Construction of metabolic operons catalyzing the de novo biosynthesis of indigo in Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology. 1993;11:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt0393-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson G W, Tsay Y H, Kienzle B K, Smith-Monroy C A, Bishop R W. Conservation between human and fungal squalene synthetases: similarities in structure, function, and regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2706–2717. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephanopoulos G. Metabolic engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1994;5:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(05)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamano S, Ishii T, Nakagawa M, Ikenaga H, Misawa N. Metabolic engineering for production of β-carotene and lycopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:1112–1114. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]