Abstract

Based on comparative sequence analysis, we have designed an oligonucleotide probe complementary to a region of 16S rRNA of Legionella pneumophila which allows the differentiation of L. pneumophila from other Legionella species without cultivation. The specificity of the new probe, LEGPNE1, was tested by in situ hybridization to a total of four serogroups of six strains of L. pneumophila, five different Legionella spp. and three nonlegionella species as reference strains. Furthermore, L. pneumophila cells could be easily distinguished from Legionella micdadei and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells by using in situ hybridization with probes LEGPNE1, LEG705, and EUB338 after infection of the protozoan Acanthamoeba castellanii.

The environmental pathogen Legionella pneumophila, which is the etiologic agent of Legionnaires’ disease, normally inhabits aquatic environments or wet soil, usually surviving as intracellular parasites of amoebae and ciliates (10). Intracellular growth of L. pneumophila in trophozoites of a variety of amoebae has been demonstrated under laboratory conditions (16). Consequently, legionellae contained in amoebae (and especially in amoebal cysts) can survive environmental temperature extremes, chlorination, and other adverse conditions. Overall, infected amoebae containing legionellae are possibly present in the drift from contaminated aquatic environments (6) and provide an excellent vehicle whereby concentrated infectious particles could be delivered to humans. Development of legionellosis has been attributed to the inhalation of viable organisms in fine aerosols into the lung, in which they invade the alveolar macrophages and other phagocytic cells (13, 15). Isolation and reliable culturing of Legionella on selective medium is fastidious, especially because the bacterium is able to form viable but not culturable cells which cannot be cultured without previous passage through hosts cells, e.g., amoebae (14, 22, 25). Due to slow growth and lack of suitable phenotypic tests, identification of Legionella spp. remains difficult. Antibody techniques and DNA hybridization assays still require cultivation of the bacteria and are hampered by nonspecific binding to other bacteria or by phenotypic variation. Even PCR could require cultivation of the bacteria to be tested, considering that environmental probes, e.g., usually contain small numbers of bacteria. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) of whole cells with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes has become a highly valuable tool for the specific detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation (4, 11). Nonculturable bacteria have been identified in their natural environment, e.g., in activated sludge or in the mammalian gut or as endosymbionts (3, 23, 28).

Here, we report the design of a probe that specifically detects extra- and intracellular L. pneumophila, which is the most important pathogenic species. The new probe, LEGPNE1, which is specific for L. pneumophila, was designed based on a comparative analysis (ARB software environment for sequence data [26]) of approximately 10,000 complete or almost complete sequences of 16S rRNA sequences including those of members of the family Legionellaceae and of other bacteria. Probe LEGPNE1 (5′-ATC TGA CCG TCC CAG GTT-3′) was synthesized with a C6-TFA [6-(trifluoroacetylamino)- hexyl-(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-di-isopropyl)-phosphoramidite] aminolinker at the 5′ end (MWG Biotech). This probe was complementary to a variable domain of the 16S rRNA of L. pneumophila. All of the other available sequences in the databases showed that at least one mismatch was sufficient for the oligonucleotide to distinguish between complementary and nearly complementary sequences (1, 17) when assay conditions were stringently controlled. The probes LEG705, EUB338, and EC1531 have been described previously (2, 18, 23) and were used as positive or negative controls. For whole-cell hybridization, bacteria were fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline solution at room temperature (RT) for 1 h on a microscope slide, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and dehydrated in an aqueous ethanol series (50, 80, and 96%). Fixed cells were hybridized by application of 20 μl of hybridization buffer (25% [vol/vol] formamide for probe LEGPNE1, 0% [vol/vol] formamide for probes LEG705, EUB338, and EC1531, 0.9 M NaCl, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) containing 100 ng of labeled probe on each well of the slide, and the slide was incubated for 2 h in an isotonically equilibrated humid chamber at 43°C. The labeled oligonucleotides were gently removed by incubating the slide with washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 mM EDTA-160 mM NaCl for probe LEGPNE1, no EDTA-900 mM NaCl for probes EUB338, LEG705, and EC1531) at 43°C for 20 min. The slide was finally rinsed with distilled water, air dried in the dark, and mounted in Citifluor (Citifluor, Ltd. London, United Kingdom). Fluorescing cells were visualized with a Zeiss Axiolab microscope equipped for epifluorescence microscopy with a 50-W high-pressure mercury bulb and with Zeiss filter set 10 and set 15. Color micrographs were taken with or without digital image processing (Lowlight charge-coupled device camera; INTAS, Germany). Digital image processing was performed with the standard software package (Adobe Photoshop; Adobe). Color micrographs were taken with Fuji Sensia 400 color slide film. The specificities of the probe LEGPNE1 against six strains of L. pneumophila (four serogroups), five different Legionella spp., and four nonlegionellae reference strains were evaluated by whole-cell hybridization (Table 1). Probe LEGPNE1 was then compared to probe LEG705, which recognizes most members of the family Legionellaceae (18), and to probe EUB338 (2), which detects all Bacteria. Probe EC1531 (23) is specific for the 23S rRNA of Escherichia coli and was used as a positive control for E. coli K-12 HB101 and as a negative control for L. pneumophila Corby (Table 1). The optimal hybridization stringency for probe LEGPNE1 was determined by gradually increasing (by 0 to 50%, in 10% intervals) the formamide concentration in the hybridization buffer while keeping the ionic strength (0.9 M NaCl) and hybridization temperature (43°C) constant. At 20 and 30% (vol/vol) formamide, probe LEGPNE1 hybridized to all L. pneumophila strains tested and did not hybridize to non-L. pneumophila species. Formamide concentrations higher than 30% led to a decrease in signal intensity (data not shown). No false-positive hybridization occurred with the reference strains; however, we obtained strong hybridization signals for the positive control EUB338 against all species tested and for probe LEG705 against all Legionella species used in this study (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Target organisms and reference strains used for FISH

| Organisma | Sourceb or reference | Hybridization signal with the following probesc:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | LEG705 | LEGPNE1 | ||

| Legionella pneumophila | ||||

| Philadelphia I (S1) | ATCC 33152 | + | + | + |

| Corbyd | 15 | + | + | + |

| U21 (S6) (environmental isolate) | 7 | + | + | + |

| 667 (S4) (patient isolate) | 7 | + | + | + |

| Bloomington (S3) | ATCC 33155 | + | + | + |

| Los Angeles (S4) | ATCC 33156 | + | + | + |

| Legionella bozemanii | ATCC 33217 | + | + | − |

| Legionella hackeliae (S1) | ATCC 33250 | + | + | − |

| Legionella longbeachae (S1) | ATCC 33462 | + | + | − |

| Legionella micdadei | ATCC 33218 | + | + | − |

| Legionella anisa | 12 | + | + | − |

| Burkholderia cepacia | ||||

| L16-3-11 | 8 | + | − | − |

| LC21-3b | 8 | + | − | − |

| Escherichia coli K-12 HB101e | 9 | + | − | − |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa SS712 | 7 | + | − | − |

S1 through S6, serogroups 1 through 6.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.

+, strong hybridization signal; −, no hybridization signal.

No hybridization signal with probe EC1531.

Strong hybridization signal with probe EC1531.

In order to determine the sensitivity of LEGPNE1, an artificial water microcosm was set up by inoculating approximately 2,000 cells of L. pneumophila Corby, 2,000 cells of Legionella micdadei, and 27,000 cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa into 100 ml of H2O (sterile). Following filtration, we could identify 3 cells of L. pneumophila with probe LEGPNE1 and 10 cells of L. micdadei with probe LEG705 in 1 ml of H2O (data not shown). These results demonstrate that probe LEGPNE1 is suitable for detection of the specific pathogenic target species L. pneumophila.

Detection of Legionella spp. in natural environments has mainly been done by using antibodies, PCR, and related techniques (19, 21, 24). Unfortunately, the use of antibodies is often hampered by unspecific binding to other bacteria and phenotypic antigen variation (29). Furthermore, biofilms can act as a penetration barrier, making it almost impossible to detect bacteria in deeper layers of the biofilm (27). FISH of Legionellaceae in water samples and model biofilms has been successfully applied and has been shown to be a reliable and quick detection method (18). Nevertheless, previously there was no specific probe available to distinguish the pathogenic species L. pneumophila from other Legionella spp., e.g., after infection of amoebae or in environmental samples. A quantitative model for intracellular growth of L. pneumophila in amoebae is the infection of Acanthamoeba castellanii (20). FISH of bacteria within fixed cells of A. castellanii (ATCC 30234) was performed as follows. Axenic cultures of A. castellanii were prepared in 20 ml of Acanthamoeba medium PYG 712 (5) at RT. Subculture of the amoebae was performed at intervals of 7 days. The axenic culture was adjusted to a titer of 2 × 107 cells per ml of buffer (i.e., PYG 712 medium without proteose peptone and yeast extract). One milliliter of culture was pipetted into a well of 24-well plates (Nunclon, Wiesbaden, Germany). Following overnight incubation, the Acanthamoeba buffer was replaced with fresh buffer; the amoebae cultures were then infected with 2 × 108 bacteria when only one strain was used and with 108 bacteria of each strain for double infections. Bacterial strains were cultivated at 37°C, harvested in H2O, and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Prior to infection, bacteria were adjusted in Acanthamoeba buffer to concentrations of 2 × 108 or 108 cells per ml. After inoculation with legionellae, the plates were incubated at the required temperature (37°C in 5% CO2) for 2 h, followed by 1 h of gentamicin treatment (50 μg/ml) to kill extracellular bacteria. After the cells were washed with gentamicin-free buffer, they were incubated in fresh buffer for the length of time desired. Following incubation, A. castellanii cells were transferred onto glass slides and air dried. Finally, slides containing A. castellanii were fixed and treated for FISH as described above. Probe LEGPNE1 was shown to be extremely useful for detection of L. pneumophila in infected amoebae. The strong fluorescent signals of the intracellular legionellae reflected a high intracellular ribosome content, indicating an elevated metabolic activity. Furthermore, we could monitor the intracellular growth of L. pneumophila in a time-dependent manner; at 16 h postinfection, Acanthamoeba cells contained either single bacteria or multiple bacteria packed in certain areas of the host cell, i.e., probably the phagosomes (Fig. 1). The number of intracellular bacteria increased over time, and at 24 h postinfection the entire lumen of each amoeba was filled with bacteria (data not shown). Given the natural life style of protozoa, it seems likely, e.g., that amoebae phagocytose bacteria of different species simultaneously. Therefore, we performed mixed infections of A. castellanii with equal numbers of L. pneumophila Corby and L. micdadei (Fig. 2) or P. aeruginosa (Fig. 3). Figure 2 shows FISH of amoebae infected with L. pneumophila Corby and L. micdadei 16 h postinfection with probes LEGPNE1 and LEG705. These experiments clearly demonstrate that FISH is also suitable for distinguishing among different Legionella species inside the host cell. In fact, there are particular areas within the amoebae (Fig. 2) in which we could detect either L. pneumophila or L. micdadei or both species. Comparable results could be obtained following FISH of amoebae infected with L. pneumophila Corby and P. aeruginosa by using probes LEGPNE1 and EUB338. Figure 3 shows that Acanthamoeba cells were filled with bacteria 16 h postinfection.

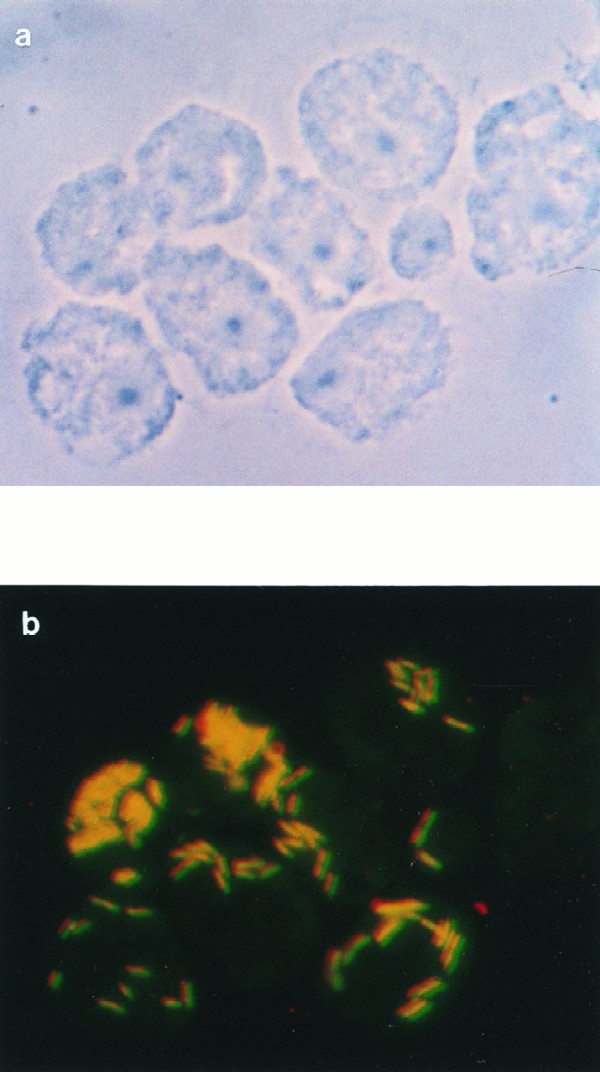

FIG. 1.

Phase-contrast (a) and epifluorescence (b) micrographs of L. pneumophila Corby-infected A. castellanii cells 16 h postinfection. The micrograph (b) represents double exposure of the sample after hybridization with the CY3-labeled probe LEGPNE1 (red) and the fluorescein-labeled probe LEG705 (green). Magnifications, ×955. Either amoebae are filled with bacteria localized in particular areas of the cells which may be the phagosomes, or bacteria are present as single cells.

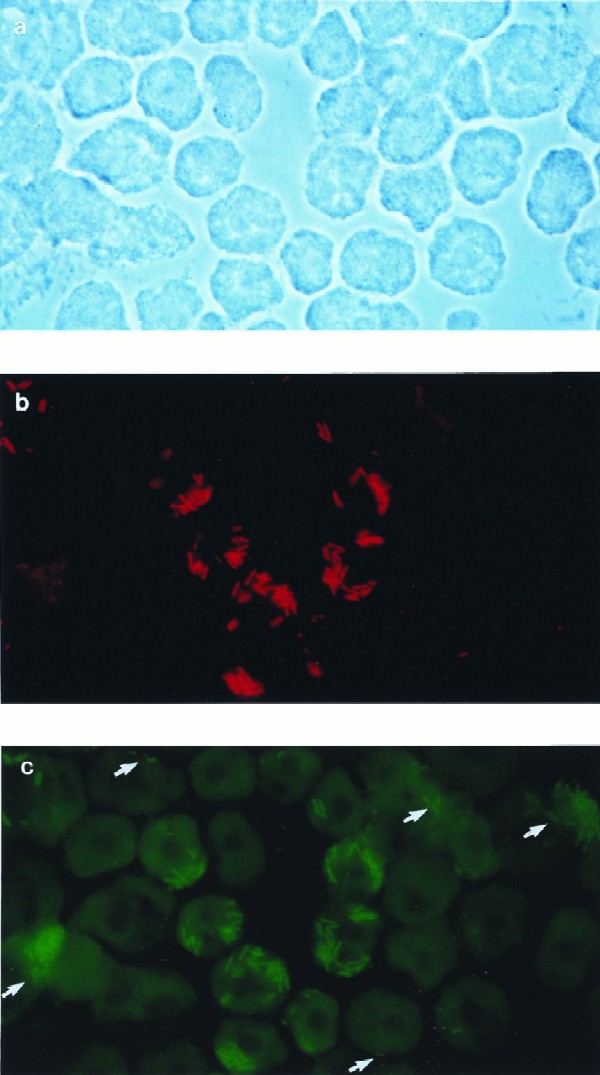

FIG. 2.

FISH of A. castellanii cells infected simultaneously with L. pneumophila Corby and L. micdadei (6 h postinfection) with a mixture of CY3-labeled probe LEGPNE1 (red) and fluorescein-labeled probe LEG705 (green). Phase-contrast (a) and epifluorescence (b and c) micrographs of identical microscopic fields are shown. All micrographs were done at the same magnification, i.e., ×744. Arrows indicate amoeba cells infected with L. micdadei.

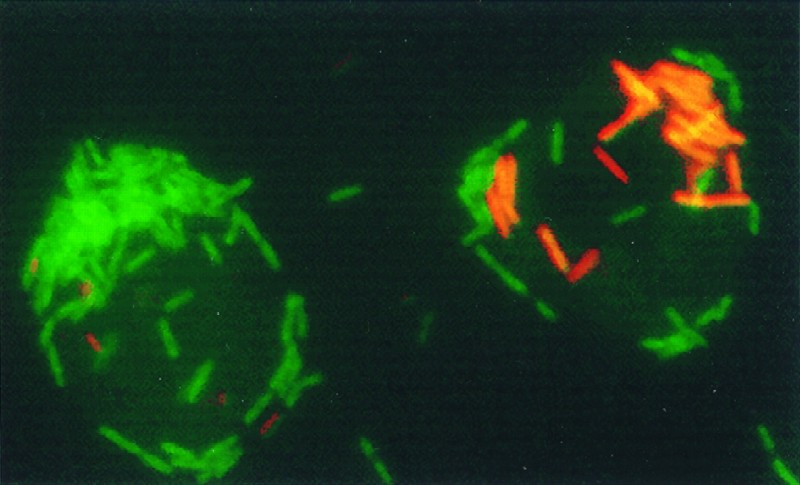

FIG. 3.

FISH of A. castellanii cells infected simultaneously with L. pneumophila Corby and P. aeruginosa (16 h postinfection) with a mixture of CY3-labeled probe LEGPNE1 (red) and fluorescein-labeled probe EUB338 (green). The epifluorescence micrograph was done by image processing. Magnification, ×1,206.

In conclusion, this study clearly demonstrated that probe LEGPNE1 is an excellent tool to specifically detect single cells of L. pneumophila in pure cultures and after infection of amoebae and may be of considerable importance to elucidate the ecology and the link to the pathogenicity of this organism. In addition, the FISH technique with oligonucleotides targeted against 16S rRNA has also been shown to have potential applications for the detection of bacteria from environmental samples (3), thereby providing a reliable technique to recognize natural reservoirs for disease and to monitor disinfection procedures. These applications are currently being evaluated in our lab.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Berg for providing the Burkholderia cepacia strains, M. Steinert for the gift of Legionella anisa, and R. Amann for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Bavarian Funding of Environmental Protection (grant 6496742-9180 from the Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Landesentwicklung und Umweltfragen) and from the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Springer N, Ludwig W, Görtz H D, Schleifer K-H. Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature. 1991;351:161–169. doi: 10.1038/351161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Type Culture Collection. Catalogue of protists—algae and protozoa. 16th ed. Supplement: media formulations. Rockville, Md: American Type Culture Collection; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbaree J M, Fields B S, Feeley J C, Gorman G W, Martin W T. Isolation of protozoa from water associated with a legionellosis outbreak and demonstration of intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:422–424. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.2.422-424.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender L, Ott M, Debes A, Rdest U, Heeseman J, Hacker J. Distribution, expression, and long-range mapping of legiolysin gene (lly)-specific DNA sequences in legionellae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3333–3336. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3333-3336.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg, G. Personal communication

- 9.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementary analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand B C, Hacker J. The biology of Legionella infection. In: Kaufmann S H E, editor. Host response to intracellular pathogens. Austin, Tex: R. G. Landes Company; 1996. pp. 291–312. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLong E F, Wickham G S, Pace N R. Phylogenetic stains: ribosomal RNA-based probes for the identification of single microbial cells. Science. 1989;243:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.2466341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields B S, Barbaree J M, Sanden G N, Morrill W E. Virulence of a Legionella anisa strain associated with Pontiac fever: an evaluation using protozoan, cell culture, and guinea pig models. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3139–3142. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3139-3142.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz M A, Silverstein S C. Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) multiplies intracellularly in human monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:441–450. doi: 10.1172/JCI109874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussong D, Colwell R R, O’Brien M, Weiss E, Pearson A D, Weiner R M, Burge W D. Viable Legionella pneumophila not detectable by culture on agar media. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:947–950. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jepras R I, Fitzgeorge R B, Baskerville A. A comparison of virulence of two strains of Legionella pneumophila based on experimental aerosol infection of guinea pigs. J Hyg. 1985;95:29–38. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400062252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtz J B, Bartlett C L R, Newton U A, White R A, Jones N L. Legionella pneumophila in cooling water systems—report of a survey of cooling towers in London and a pilot trial of selected biocides. J Hyg. 1982;88:369–381. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400070248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manz W, Amann R I, Ludwig W, Wagner M, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the major subclasses of proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manz W, Amann R I, Szewzyk R, Szewzyk U, Stenström T-A, Hutzler P, Schleifer K-H. In situ identification of Legionellaceae using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Microbiology. 1995;141:29–39. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markin T, Hart C A. Detection of Legionella pneumophila in environmental water samples using a fluorescein conjugated monoclonal antibody. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:105–112. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffat J F, Tompkins L S. A quantitative model of intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Infect Immun. 1992;60:296–301. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.296-301.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer C J, Tsai Y-L, Paszko-Kolva C, Mayer C, Sangermano L R. Detection of Legionella species in sewage and ocean water by polymerase chain reaction, direct fluorescent-antibody, and plate culture methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3618–3624. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3618-3624.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paszko-Kolva C, Shahamat M, Colwell R R. Longterm survival of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 under low-nutrient conditions and associated morphological changes. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1992;102:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poulsen L K, Lan F, Kristensen C S, Hobolth P, Molin S, Krogfelt K A. Spacial distribution of Escherichia coli in the mouse large intestine inferred from rRNA in situ hybridization. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5191–5194. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5191-5194.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers J, Keevil C W. Immunogold and fluorescein immunolabeling of Legionella pneumophila within an aquatic biofilm visualized by using episcopic differential interference contrast microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2326–2330. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2326-2330.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinert M, Emödy L, Amann R, Hacker J. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2047–2053. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.2047-2053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strunk, O., O. Gross, B. Reichel, M. May, S. Hermann, N. Stuckmann, B. Nonhoff, T. Ginhart, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode, K.-H. Schleifer, and W. Ludwig. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Submitted for publication.

- 27.Szwerinski H, Gaiser S, Bardtke D. Immunofluorescence for the quantitative determination of nitrifying bacteria: interference of the test in biofilm reactors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1985;21:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner M, Erhart R, Manz W, Amann R I, Lemmer H, Wedi D, Schleifer K-H. Development of an rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe specific for the genus Acinetobacter and its application for in situ monitoring in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:792–800. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.792-800.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson I J, Sangster N, Ratcliff R M, Mugg P A, Davos D E, Lanser J A. Problems associated with identification of Legionella species from the environment and isolation of six possible new species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:796–802. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.796-802.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]