Abstract

Background:

The use of intestinal ultrasound (IUS) in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is emerging. We aim to determine the performance of IUS in the assessment of disease activity in IBD.

Methods:

This is a prospective cross-sectional study of IUS performed on IBD patients in a tertiary centre. IUS parameters including intestinal wall thickness, loss of wall stratification, mesenteric fibrofatty proliferation, and increased vascularity were compared with endoscopic and clinical activity indices.

Results:

Among the 51 patients, 58.8% were male, with a mean age of 41 years. Fifty-seven percent had underlying ulcerative colitis with mean disease duration of 8.4 years. Against ileocolonoscopy, IUS had a sensitivity of 67% (95% confidence interval (CI): 41-86) for detecting endoscopically active disease. It had high specificity of 97% (95% CI: 82-99) with positive and negative predictive values of 92% and 84%, respectively. Against clinical activity index, IUS had a sensitivity of 70% (95% CI: 35-92) and specificity of 85% (95% CI: 70-94) for detecting moderate to severe disease. Among individual IUS parameters, presence of bowel wall thickening (>3 mm) had the highest sensitivity (72%) for detecting endoscopically active disease. For per-bowel segment analysis, IUS (bowel wall thickening) was able to achieve 100% sensitivity and 95% specificity when examining the transverse colon.

Conclusions:

IUS has moderate sensitivity with excellent specificity in detecting active disease in IBD. IUS is most sensitive in detecting a disease at transverse colon. IUS can be employed as an adjunct in the assessment of IBD.

Keywords: Clinical activity index, endoscopic activity index, ileocolonoscopy, inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing-remitting disease, comprising mainly of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). To date, IBD management revolves around reducing the disease activity and maintaining its remission state. Thus, long-term periodic monitoring of disease activity is essential to ensure a stable course of disease. IBD can be assessed either by clinical symptoms, biomarkers, radiology, or endoscopy.

Ileocolonoscopy is considered as the gold standard in establishing the diagnosis of IBD and determining its disease activity. However, it is an invasive procedure with the risk of bleeding and perforation,[1] and a possible unpleasant experience due to the need of bowel preparation. Clinical symptoms and biomarkers on the other hand, are less reliable tools if used alone. It is well-documented that clinical symptoms and biomarkers correlate poorly with the endoscopic findings.[2] Other radiological investigations which also play a role in the diagnosis as well as disease monitoring of IBD include contrast luminal radiographic studies, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, contrasted radiological tests have a risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury, and cumulative radiation from repeated exposures of radiological tests may increase cancer risk in patients with IBD.[3,4]

The role of abdominal ultrasound in assessing bowel is less established due to technical difficulties in obtaining high quality images.[5] However, in the last two decades, there is a growing interest in using intestinal ultrasound (IUS) in the management of IBD. IUS has the advantage of being non-invasive, inexpensive, widely available, and does not involve ionizing radiation.[6] Furthermore, the management of IBD has evolved from sole clinical symptoms-driven intensification of therapy to ‘treat-to-target’ strategy, as the use of biologic immunosuppressive agents in asymptomatic patients with active disease based on endoscopy and disease biomarkers can prevent disease progression.[7] With the presence of contradictory clinical symptoms and endoscopic findings demonstrated in some patients,[8] an adjunctive use of IUS to determine the activity of disease in IBD might be helpful in guiding a proper optimal management.

Some ultrasonographic parameters have been recognized as indicators of intestinal inflammation in IBD. The main parameter is intestinal wall thickness whereby more than 2 mm in small intestine and more than 3 mm in colon is considered pathological thickening. Another parameter is intestinal wall stratification. Intestinal wall consists of five distinct layers that can be evaluated using ultrasound, and loss of this layer stratification indicates inflamed intestinal segment which can be assessed especially using high resolution ultrasound probe. Further evidence of intestinal inflammation can be supported by the presence of mesenteric fibrofatty proliferation (hyperechoic zone surrounding the inflamed intestine) and increased vascularity in intestinal wall/associated mesentery (detected by colour Doppler). In addition, intestinal complications of IBD such as stricture, fistula, and abscess can also be detected by using IUS.[9]

The prevalence rate of IBD in Malaysia is low when compared to Western countries (9.24 vs 23.67 per 100,000 population).[10,11] Nevertheless, there is a steady increase in mean incidence of IBD in Malaysia over the past two decades (from 0.07 to 0.69 per 100,000 population-years).[10] In Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC) notably, there is an increasing number of IBD patients since the last decade: IBD mean crude incidence of 0.36 (1980-1989) and, 0.48 (1990-1999), 0.63 (2000-2009) doubled up to 1.46 per 100,000 population-years in 2010-2018 period.[12] This resulted in the rise of social and economic burden on government and healthcare systems. Therefore, incorporation of IUS in the monitoring of IBD patients need to be considered. The accuracy of IUS in the monitoring of disease activity requires further evaluation and study to identify its value as a primary investigation in IBD.

METHODS

Study design

This is a single-centre, prospective, and cross-sectional study conducted between December 2019 and February 2022 at the UKMMC and approved by its research ethics committee (research code: FF-2019-421). All patients having IBD and planned for ileocolonoscopy under gastroenterology service in UKMMC were included. Patients with previous intestinal surgery, isolated small bowel disease, pregnancy, and bowel malignancy were excluded.

All recruited patients were subjected to IUS and faecal calprotectin as the additional tests to the usual care of IBD patients in our centre. The IUS and faecal calprotectin were arranged within three weeks after the ileocolonoscopy. Other radiological examinations such as CT and MRI done within one month duration from ileocolonoscopy were included in the study. The patients were assessed on the clinical activity index using Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) for CD and partial Mayo Score for UC; and endoscopic activity index using Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) for CD and Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) for UC. Remission and mild diseases were grouped into inactive disease while moderate and severe diseases were grouped as active disease. IUS findings were compared with clinical activity index as a standard reference to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values. IUS findings were also compared with clinical activity index, as well as disease biomarkers (faecal calprotectin and C-reactive protein [CRP]) and radiological examinations (CT and MRI) to assess for correlation.

Tests and variables

Intestinal ultrasound parameters

The IUS was performed by using an ultrasound unit in the Department of Radiology UKMMC. Ultrasound machine Toshiba Aplio 500® or Xario 200® (Japan) as well as Supersonic Aixplorer® (France) were used. Two ultrasound probes were utilized during scanning, a 3-6 MHz convex-array transducer and a 6-12 MHz probe, the latter for a detailed high-resolution examination using bowel preset. Examination of the gastrointestinal tract was divided into five segments namely the rectum, left colon (sigmoid colon and descending colon), transverse colon, right colon (ascending colon and caecum), and terminal ileum. Two radiologists (F.M.Z and J.F.M) with more than five years’ experiences with ultrasound were involved in the study, and were blinded from the ileocolonoscopy findings, clinical scores as well as biomarkers. IBD involvement was determined in each intestinal segment by assessing the following parameters [Figures 1 and 2]:

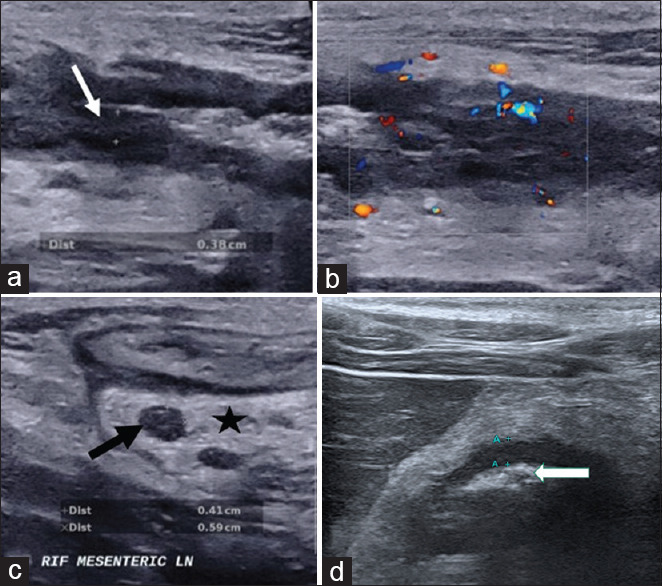

Figure 1.

Intestinal ultrasound images show (a) thickened bowel wall with loss of bowel wall stratification (white arrow) with (b) increased bowel wall vascularity, (c) enlarged lymph node (black arrow) and increased mesenteric echogenicity indicating mesenteric fibrofatty proliferation (star) as well as (d) narrowing or stenosis of the bowel lumen (white arrow) with mild thickened bowel

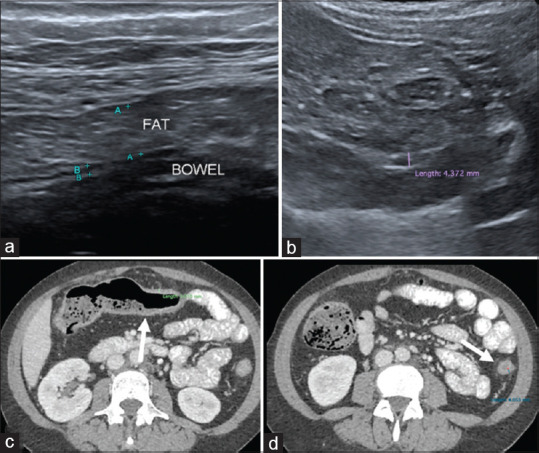

Figure 2.

False negative case example of a 43-year-old with history of Ulcerative Colitis (UC) shows (a) increased fat thickness but no mesenteric echogenicity with normal bowel wall thickness that measures 3 mm at transverse colon. (b) IUS images at descending colon shows mild thickened bowel (at upper limit of normal thickness) with no loss of stratification; thus, concluded as no active disease on ultrasound (c) Axial CT abdomen taken a day after shows mild thickened bowel wall of the transverse colon as well as collapsed and mildly thickened descending colon (white arrows in d). There is mild mesenteric fat streakiness. This patient had clinically active disease of UC at the time of imaging

Intestinal wall thickness (thickened wall 3 mm and above).

Loss of wall stratification (LWS).

Presence of mesenteric fibrofatty proliferation.

Increased vascularity in intestinal wall or associated mesentery.

Intestinal complications of IBD such as stricture, fistula, and abscess.

Harvey-Bradshaw Index

HBI [Supplementary Table 1] was developed in 1980 and is considered as a shorter version of Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI). The index consists of five purely clinical parameters. Patient’s clinical state can be categorized into four groups based on the scores: <5 remission, 5-7 mild activity, 8-16 moderate activity, and >16 severe activity.[13]

Supplementary Table 1.

Harvey-Bradshaw index

| Parameter | Input and Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Patient well-being (previous day) | 0=very well |

| 1=slightly below par | |

| 2=poor | |

| 3=very poor | |

| 4=terrible | |

| 2. Abdominal pain (previous day) | 0=none |

| 1=mild | |

| 2=moderate | |

| 3=severe | |

| 3. Number of liquid or soft stools (previous day) | 1 – 25 |

| 4. Abdominal mass | 0=none |

| 1=dubious | |

| 2=definite | |

| 3=definite and tender | |

| 5. Complications | No (0 points) |

| Yes (each complication is counted as 1 point) | |

| Arthralgia | |

| Uveitis | |

| Erythema nodosum | |

| Aphthous ulcer | |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | |

| Anal fissures | |

| Appearance of a new fistula | |

| Abscess |

Partial Mayo score

Partial Mayo Score [Supplementary Table 2] uses three non-endoscopic components from the full Mayo Score (stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and physician’s global assessment). Patient’s clinical state can be categorized into four groups based on the sum of the scores: <2 remission, 2-4 mild activity, 5-7 moderate activity, and >7 severe activity.[14]

Supplementary Table 2.

Partial Mayo score

| Parameter | Clinical evaluation | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Stool frequency (per day) | Normal number of stools | 0 |

| 1-2 more than normal | 1 | |

| 3-4 more than normal | 2 | |

| ≥5 more than normal | 3 | |

| 2. Rectal bleeding (indicate the most severe bleeding of the day) | None | 0 |

| Streaks of blood with stool in less than half of the cases | 1 | |

| Obvious blood with stools in most cases | 2 | |

| Blood alone passes | 3 | |

| 3. Physician’s global assessment | Normal | 0 |

| Mild disease | 1 | |

| Moderate disease | 2 | |

| Severe disease | 3 |

Simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease

SES-CD [Supplementary Table 3] was developed in 2004 and it simplified the Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS). It is used to evaluate evidence of inflammation at each ileo-colonic segment (rectum, left colon, transverse colon, right colon, and terminal ileum). Each individual segment’s score can be added and the higher the total SES-CD score, the more severe overall inflammation is 0-2 remission, 3-6 mild activity, 7-15 moderate activity, and ≥16 severe activity. It has strong correlation with the CDEIS and excellent interobserver agreement.[15]

Supplementary Table 3.

Simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease

| Variable | SES-CD values (evaluated for each of the 5 ileo-colonic segments) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Size of ulcers | None | Aphthous ulcers (0.1 to 0.5 cm) | Large ulcers (0.5 to 2 cm) | Very large (>2 cm) |

| Ulcerated surface | None | <10% | 10-30% | >30% |

| Affected surface | Unaffected segment | <50% | 50-75% | >75% |

| Presence of narrowing | None | Single, can be passed | Multiple, can be passed | Cannot be passed |

Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity

UCEIS [Supplementary Table 4] is used to score the most affected colonic area. It has high correlation with the overall assessment of severity and good intra/interobserver reliability.[16] The higher the score, the more severe the inflammation: 0-1 remission, 2-4 mild activity, 5-6 moderate activity, and 7-8 severe activity. UCEIS outperform Mayo Endoscopic Score (another endoscopic index of severity in UC) and a value of 7 and above predicts the need for salvage therapy such as biologic therapy or colectomy.[17]

Supplementary Table 4.

Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity

| Descriptor (score most severe lesions) | Likert scale anchor points | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular pattern | Normal (0) | Normal vascular pattern with arborization of capillaries clearly defined, or with blurring or patchy loss of capillary margins |

| Patchy loss (1) | Patchy obliteration of vascular pattern | |

| Obliterated (2) | Complete obliteration of vascular pattern | |

| Bleeding | None (0) | No visible blood |

| Mucosal (1) | Some spots or streaks of coagulated blood on the surface of the mucosa ahead of the scope, which can be washed away | |

| Luminal mild (2) | Some free liquid blood in the lumen | |

| Luminal severe (3) | Frank blood in the lumen ahead of endoscope or visible oozing from mucosa after washing intra-luminal blood, or visible oozing from a hemorrhagic mucosa | |

| Erosions and ulcers | None (0) | Normal mucosa, no visible erosions or ulcers |

| Erosions (1) | Tiny (≤5 mm) defects in the mucosa, of a white or yellow color with a flat edge | |

| Superficial ulcer (2) | Larger (>5 mm) defects in the mucosa, which are discrete fibrin-covered ulcers when compared to erosions, but remain superficial | |

| Deep ulcer (3) | Deeper excavated defects in the mucosa, with a slightly raised edge |

Sample size

IBD prevalence in Malaysia is still low (9.24 per 100,000 population). However, UKMMC is a tertiary referral centre for IBD, accepting IBD cases in the whole country. The prevalence of IBD from gastroenterology clinic in UKMMC is approximated to be 7-10%. We referred to a table prepared by Bujang MA and Adnan TH (2016),[18] which was developed after calculation by using PASS software. This table was intended to be used to find a minimum sample size required for sensitivity and specific analysis. Based on the table, the minimum sample size that is required for the study is 31 patients. We took 50 patients as the adequate sample size.

Statistical analysis

In this study, ‘Statistical Product and Service Solution’ (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) software version 26 was used for data analysis. IUS findings were compared with endoscopic findings, by using ileocolonoscopy as the reference standard. Overall and per segment basis of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated, as well as the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess correlation between IUS findings and clinical activity index, inflammatory markers, and radiological examinations. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

A total of 51 patients were enrolled in this study. There was a slight male predominance (58.8%) in the cohort, and majority of patients were Malays (72.5%). The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age of the patients was 40.92 ± 15.62 years. In total, 56.9% (n = 29) of patients had underlying UC, while the mean duration of disease was 8.4 ± 7.2 years. Clinically, 19.6% (n = 9) of patients were in active disease, with overall 2% (n = 1) having severe disease activity. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical data of our patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients

| Characteristics | Total n=51 | Ulcerative Colitis n=29 | Crohn’s Disease n=22 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender no. (%) | |||

| Male | 30 (58.8) | 19 (65.5) | 11 (50.0) |

| Female | 21 (41.2) | 10 (34.5) | 11 (50.0) |

| Ethnicity no. (%) | |||

| Malay | 37 (72.5) | 24 (82.8) | 13 (59.1) |

| Chinese | 5 (9.8) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (9.1) |

| Indian | 9 (17.6) | 2 (6.9) | 7 (31.8) |

| Age (years) | 40.92±15.62 | 43.00±14.09 | 38.18±17.39 |

| IBD type no. (%) | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 29 (56.9) | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 22 (43.1) | ||

| Montreal Classification no. (%) | |||

| E1=ulcerative proctitis | 10 (34.5) | ||

| E2=left-sided colitis | 10 (34.5) | ||

| E3=pancolitis | 9 (31.0) | ||

| L1=ileal | 1 (4.5) | ||

| L2=colonic* | 10 (45.5) | ||

| L3=ileocolonic | 11 (50.0) | ||

| Disease duration (years) | 8.40±7.22 | 9.41±7.63 | 7.07±6.57 |

| Clinical activity index no. (%) | |||

| Remission | 32 (62.7) | 21 (72.4) | 11 (50.0) |

| Mild | 9 (17.6) | 5 (17.2) | 4 (18.2) |

| Moderate | 9 (17.6) | 2 (6.9) | 7 (31.8) |

| Severe | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Clinical disease activity no. (%) | |||

| Inactive | 41 (80.4) | 26 (89.7) | 15 (68.2) |

| Active | 10 (19.6) | 3 (10.3) | 7 (31.8) |

Continuous values are mean±standard deviation; discrete values are n (%); *1 patient had concomitant perianal disease

Performance of intestinal ultrasound in the assessment of disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease

In comparison with endoscopic activity index

Among the 51 patients, 25.5% (n = 13) had active disease based on IUS findings. Against ileocolonoscopy, IUS had a sensitivity of 67% (95% CI: 41-86) for detecting endoscopically active disease. It had high specificity of 97% (95% CI: 82-99) with positive and negative predictive values of 92% and 84%, respectively. However, the performance of IUS was better in CD as compared to UC with a sensitivity of 80% and 50%, respectively.

Among individual IUS parameters, presence of bowel wall thickening (BWT) (>3 mm) had the highest sensitivity for detecting endoscopically active disease-72% (95% CI: 46-89), followed by LWS-61% (95% CI: 36-82), fibrofatty proliferation and increased vascularity-50% (95% CI: 27-73) for both. According to the type of disease, all IUS parameters have low sensitivity of 33% in UC and perform better in CD, with a sensitivity of 60-80%.

For per-bowel segment analysis, IUS (BWT) was able to achieve 100% sensitivity and 95% specificity when examining the transverse colon in total, 100% sensitivity and specificity in UC, and 100% sensitivity and 88% specificity in CD. For right and left colons, IUS showed a sensitivity of 70% and 61%, respectively. Contrary to this, IUS showed a poor performance at the rectum and terminal ileum, with a sensitivity of 42% and 40%, respectively. In UC, IUS had poor performance in other bowel segments beside transverse colon.

In general, IUS parameters correlated well with endoscopic activity index with statistically significant association (r = 0.698, P < 0.01). Similarly, there was a statistically significant association between IUS parameters and endoscopic activity index according to type of disease, UC (r = 0.648, P < 0.01) and CD (r = 0.726, P < 0.01), respectively.

In comparison with clinical activity index

Against clinical activity index, IUS had a sensitivity of 70% (95% CI: 35-92) and specificity of 85% (95% CI: 70-94) for detecting moderate to severe disease. There was a statistically significant association between IUS parameters and clinical activity index (r = 0.504, P < 0.01). However, IUS in UC had a poor correlation with clinical activity index (r = 0.192, P = 0.317), with a low sensitivity of 33% (95% CI: 2-88).

In comparison with disease biomarkers

In general, IUS parameters had statistically significant association with disease biomarkers such as faecal calprotectin (r = 0.489, P < 0.01) and CRP (r = 0.604, P < 0.01). Similar correlation was observed in both UC and CD.

In comparison with other radiological modalities

By correlating the IUS parameters with other radiological modalities such as CT/MRI, we found that IUS had significant association (r = 0.661, P < 0.01). In our study, there was only one CT/MRI done in UC, thus, correlation cannot be assessed. In CD, similar correlation was observed (r = 0.745, P = 0.002).

Table 2 summarizes the performance of IUS in the assessment of disease activity in IBD.

Table 2.

Performance of intestinal ultrasound in the assessment of disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease

| Performance of IUS | Sensitivity %[95%CI] | Specificity %[95%CI] | PPV %[95%CI] | NPV %[95%CI] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | UC | CD | Total | UC | CD | Total | UC | CD | Total | UC | CD | |

| vs EAI | ||||||||||||

| Overall | 66.7 [41,86] | 50.0 [17,83] | 80.0 [44,97] | 97.0[83,100] | 100 [81,100] | 91.7[60,100] | 92.3[62,100] | 100[40,100] | 88.9 [51,99] | 84.2 [68,93] | 84 [63,95] | 84.6 [54,97] |

| Per parameters | ||||||||||||

| BWT | 72.2 [46,89] | 33.3 [2,88] | 80.0 [44,97] | 75.8 [57,88] | 65.4 [44,82] | 75.0 [43,93] | 61.9 [39,81] | 10.0 [1,46] | 72.7 [39,93] | 83.3 [65,94] | 89.5 [66,98] | 81.8 [48,97] |

| LWS | 61.1 [36,82] | 33.3 [2,88] | 70.0 [35,92] | 93.9 [78,99] | 84.6 [64,95] | 91.7[60,100] | 84.6 [54,97] | 20.0 [1,70] | 87.5 [47,99] | 81.6 [65,92] | 91.7 [72,99] | 78.6 [49,94] |

| MFP | 50.0 [27,73] | 33.3 [2,88] | 60.0 [27,86] | 100 [87,100] | 92.3 [73,99] | 100 [70,100] | 100 [63,100] | 33.3 [2,88] | 100[52,100] | 78.6 [63,89] | 92.3 [73,99] | 75.0 [47,92] |

| IV | 50.0 [27,73] | 33.3 [2,88] | 60.0 [27,86] | 97.0[83,100] | 92.3 [73,99] | 91.7[60,100] | 90.0[54,100] | 33.3 [2,88] | 85.7 [42,99] | 78.0 [62,89] | 92.3 [73,99] | 73.3 [45,91] |

| Per-bowel segment | ||||||||||||

| Terminal ileum | 40.0 [14,73] | 0.0 [0,95] | 44.4 [15,77] | 97.6[86,100] | 96.4[80,100] | 100 [72,100] | 80.0 [30,99] | 0.0 [0,95] | 100[40,100] | 87.0 [73,95] | 96.4[80,100] | 72.2 [46,89] |

| Right colon | 70.0 [35,92] | 0.0 [0,95] | 77.8 [40,96] | 100 [89,100] | 100 [85,100] | 100 [72,100] | 100 [56,100] | - | 100[56,100] | 93.2 [80,98] | 96.6[80,100] | 86.7 [58,98] |

| Transverse colon | 100 [60,100] | 100[31,100] | 100[46,100] | 95.3 [83,99] | 100 [84,100] | 88.2 [62,98] | 80.0 [44,97] | 100[31,100] | 71.4 [30,95] | 100 [89,100] | 100 [84,100] | 100[75,100] |

| Left colon | 61.1 [36,82] | 45.5 [18,75] | 85.7 [42,99] | 100 [87,100] | 100 [78,100] | 100 [75,100] | 100 [68,100] | 100[46,100] | 100[52,100] | 82.5 [67,92] | 75.0 [53,89] | 93.8[68,100] |

| Rectum | 42.1 [21,66] | 36.4 [12,68] | 50.0 [17,83] | 93.8 [78,99] | 94.4[71,100] | 92.9[64,100] | 80.0 [44,97] | 80.0 [30,99] | 80.0 [30,99] | 73.2 [57,85] | 70.8 [49,87] | 76.5 [50,92] |

| Correlation | r=0.698 (P<0.01) | r=0.648 (P<0.01) | r=0.726 (P<0.01) | |||||||||

| vs CAI | ||||||||||||

| Overall | 70.0 [35,92] | 33.3 [2,88] | 85.7 [42,99] | 85.4 [70,94] | 88.5 [69,97] | 80.0 [51,95] | 53.8 [26,80] | 25.0 [1,78] | 66.7 [31,91] | 92.1 [78,98] | 92.0 [73,99] | 92.3[62,100] |

| Correlation | r=0.504 (P<0.01) | r=0.192 (P=0.317) | r=0.623 (P=0.002) | |||||||||

| vs biomarkers | ||||||||||||

| Faecal calprotectin | r=0.489 (P=0.001) | r=0.461 (P=0.018) | r=0.511 (P=0.025) | |||||||||

| C-reactive protein | r=0.604 (P<0.01) | r=0.475 (P=0.009) | r=0.647 (P=0.001) | |||||||||

| vs CT/MRI | ||||||||||||

| Correlation | r=0.661 (P=0.007) | - | r=0.745 (P=0.002) | |||||||||

IUS=intestinal ultrasound, PPV=positive predictive value, NPV=negative predictive value, CI=confidence interval, UC=ulcerative colitis, CD=Crohn’s disease, vs=versus, EAI=endoscopic activity index, BWT=bowel wall thickening, LWS=loss of wall stratification, MFP=mesenteric fatty proliferation, IV=increased vascularity, r=Pearson’s correlation coefficient, CAI=clinical activity index, CT=computed tomography, MRI=magnetic resonance imaging

DISCUSSION

In our cohort of patients, IUS parameters were shown to have a sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 97% using ileocolonoscopy as a reference standard. This implies the possibility of using IUS as an adjunctive assessment tool in IBD as it is easily available.

Despite its limitation in assessing the proximal jejunum and rectum, a systemic review by Panés et al.[19] found a good sensitivity and specificity of IUS for diagnosis and evaluation of CD, when used at terminal ileum and colon. Similarly, our study revealed a better sensitivity and specificity of IUS parameters especially BWT in CD. This can be explained by the superficial inflammation in UC which does not affect much on the bowel wall thickness and stratification,[20] thus requiring other parameters such as increased vascularity to determine the inflamed colon.[21] However, when examining the correlation between IUS findings and clinical activity index or biomarkers, some conflicting results were apparent. Majority of previous studies revealed no significant correlation between IUS and clinical activity index.[22-26] However, other studies by showed a significant correlation between IUS findings and clinical activity index.[27-29] In relation to correlation between IUS and biomarkers (mainly CRP), all the studies showed no correlation, except for the study done by Martinez et al.[29]

Among individual IUS parameters, BWT has the highest sensitivity in detecting endoscopically active disease. This finding echoes the findings in the studies by Maconi et al.[22] and Bremner et al..[30] The higher sensitivity of BWT as compared to other parameters of IUS can be possibly due to its relatively objective and quantitative measurement. Furthermore, BWT was found to be a temporal measurement which can be a potential sole parameter to monitor therapeutic response in IBD.[31] With the emerging evidence of more favorable outcomes of IBD using the ‘treat-to-target’ strategy over the classical clinical symptoms-driven approach, different treatment targets including endoscopic and histological findings have been explored.[32] However, histological treatment target remains questionable as it requires an invasive procedure to obtain the sample routinely and does not have a proper scoring system.[33] Thus, the potential feature of BWT in IUS to monitor therapeutic response can assist the realization of ‘treat-to-target’ strategy in the management of IBD.

BWT in IUS was able to achieve high sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 95%, respectively, in examining the transverse colon from this study. This may be due to its relatively direct and easy anatomical location to be scanned by a transabdominal ultrasound. This also explicates the low sensitivity of IUS in examining the terminal ileum. A cadaveric study on human colon suggested that the rectosigmoid colon has the highest variation in length and the ascending and descending colons have mobility resulting in locoregional variation,[34] which can give rise to difficulty in assessing the colonic segments with IUS, leading to a reduced sensitivity of IUS in examining the right and left colons and rectum.

This is the first study done in Southeast Asia to assess the performance of IUS in IBD. UKMMC is a referral centre for all IBD cases in Malaysia. The age and ethnic distribution in this study represent the population of IBD in Malaysia.[12] While most of the previous studies on performance of IUS in IBD were done in the Western countries, this study may represent the Asian population besides another study done by Kinoshita et al.[35] Despite the difference in population, the findings were similar. Table 3 summarizes the previous studies on performance of IUS in IBD.

Table 3.

Previous studies on performance of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease

| Author | Country | Year | Population | Age, mean (SD) (year) | Sex (M: F) | Type of Disease, Number of Patients | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reference Standard | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Age Group | Number of Patients | ||||||||||

| Maconi et al.[22] | Italy | 1996 | Adult | 110 | 34.6 (13.5) | 57:53 | CD 110 | 89% | 94% | CAI | BWT is the most sensitive IUS parameter, which might suggest fibrosis in quiescent patients |

| Faure et al.[36] | France | 1997 | Pediatric | 30 | 11.1 | N/A | CD 21, UC 9 | 88% | 93% | EAI | |

| Pradel et al.[37] | France | 1997 | Adult | 35 | N/A | N/A | CD 19, UC 5, others 11 | 70% | 93% | EAI | Sensitivity is significantly lower for mild lesions (52%) than for frank lesions (87%, P<0.001) |

| Reimund et al.[38] | France | 1999 | Adult | 118 | N/A | N/A | CD 48, UC 23, others 47 | 94.4% | 66.7% | EAI | Overall accuracy is higher in CD than UC, 5 out of 6 complications of CD were detected with ultrasound |

| Miao et al.[39] | England | 2002 | Adult | 30 | 36 | 11:19 | CD 30 | 87% | 100% | CAI | |

| Pascu et al.[26] | Germany | 2004 | Adult | 61 | 38 | 26:35 | CD 37, UC 24 | 82% | 97% | EAI | Ultrasound shows better correlation with endoscopic activity than MRI |

| Bremner et al.[30] | England | 2006 | Paediatric | 44 | 12 | 24:20 | CD 25, UC 12, others 7 | 48% | 93% | EAI | BWT has good positive predictive value for moderate or severe disease |

| Migaleddu et al.[28] | Italy | 2009 | Adult | 47 | 38 (14) | 20:27 | CD 47 | 90.3% | 93.7% | CAI | |

| Martínez et al.[29] | Spain | 2009 | Adult | 30 | 34.1 (11.6) | 17:13 | CD 30 | 91% | 98% | CAI | |

| Ziech et al.[40] | Netherlands | 2014 | Paediatric | 28 | 14 | 15:13 | CD 12, UC 10, others 6 | 55% | 100% | EAI | |

| Kinoshita et al.[35] | Japan | 2019 | Adult | 156 | 43.9 (17.0) | 98:58 | UC 156 | 78.9% | 63.8% | EAI | Moderate concordance between IUS and ileocolonoscopy for assessing disease activity in UC |

| Dilillo et al.[41] | Italy | 2019 | Pediatric | 77 | 11.3 | 44:33 | N/A | 70% | 96% | EAI | Faecal calprotectin has a high sensitivity (96%) but lower specificity (72%) than ultrasound |

| Gonen et al.[42] | Turkey | 2020 | Adult | 117 | 37.7 (14.1) | 66:51 | CD 117 | 94% | 71% | MDTM | IUS examination significantly improves clinical-management decisions |

| Bots et al.[43] | Netherlands | 2021 | Adult | 60 | 44 | 28:32 | UC 60 | 89.1% | 92.3% | EAI | |

| Lim et al. | Malaysia | 2022 | Adult | 51 | 40.9 (15.6) | 30:21 | CD 22, UC 29 | 66.7% | 97% | EAI | IUS is most sensitive in detecting a disease at transverse colon |

SD=standard deviation, M=male, F=female, CD=Crohn’s disease, UC=ulcerative colitis, CAI=clinical activity index, EAI=endoscopic activity index, BWT=bowel wall thickening, IUS=intestinal ultrasound, N/A=not available, MRI=magnetic resonance imaging, MDTM=multidisciplinary team meeting

The challenges of IBD management in developing countries such as Malaysia include the lack of healthcare facilities and resources for regular disease activity monitoring. As disease biomarkers (faecal calprotectin and CRP) and other radiological examinations such as CT and MRI are not easily available in all healthcare centres, IUS can be considered as an alternative adjunct in the assessment of IBD. However, experienced and well-trained radiologists and gastroenterologists for IUS are not widely available in the Asia-Pacific region due to the lack of training centres.[44] In fact, a recent study on clinical utilization of IUS in IBD among pediatric radiologist and gastroenterologist in North America, where incidence of IBD is higher than in Asia, concluded that the IUS has been underutilized. The authors advocated a paradigm shift in utilizing IUS over magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) as a method of disease surveillance in IBD and that MRE is only reserved for cases with abnormal IUS as ultrasound is more readily available.[45] Therefore, the resources can be optimized by radiologists with additional training, since they are familiar in assessing the abdomen in general for other pathologies. There is also a need for modern gastroenterology to include abdominal ultrasound as a basic clinical skill to be able to provide bedside assessment of IBD.[46]

The limitation of this study is the lack of patients in severe and active disease. Most of the patients recruited were planned for ileocolonoscopy for colorectal cancer surveillance. They fit the recommended duration of IBD for colorectal cancer endoscopic surveillance.[47] Another limitation of this study is we grouped patients into active and inactive diseases. The development of a validated IUS activity index will provide a better comparison with endoscopic activity index.[43]

In summary, IUS has moderate sensitivity with excellent specificity in detecting active disease in IBD. IUS is most sensitive in detecting a disease at transverse colon. IUS can be employed as an adjunct in the assessment of IBD. Further studies with more active disease are needed to further assess and determine the performance of IUS in disease activity monitoring of patients with IBD.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Fundamental Grant, Faculty of Medicine UKM (FF-2019-421) and Research Grant, Malaysia Society of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to extend a special thank you to the staffs of the Radiology Department & Endoscopic Service Centre, Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz, UKM Medical Centre for their assistance during this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Navaneethan U, Parasa S, Venkatesh PG, Trikudanathan G, Shen B. Prevalence and risk factors for colonic perforation during colonoscopy in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panes J, Jairath V, Levesque BG. Advances in use of endoscopy, radiology, and biomarkers to monitor inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:362–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris MS, Chu DI. Imaging for inflammatory bowel disease. Surg Clin. 2015;95:1143–58. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naidu J, Wong Zh, Palaniappan Sh, Ngiu ChS, Yaacob NY, Abdul Hamid H, et al. Radiation exposure in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A fourteen-year review at a tertiary care centre in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:933–9. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.4.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allgayer H, Braden B, Dietrich CF. Transabdominal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease. Conventional and recently developed techniques-update. Med Ultrason. 2011;13:302–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kucharzik T, Wittig BM, Helwig U, Börner N, Rössler A, Rath S, et al. Use of intestinal ultrasound to monitor Crohn's disease activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:535–42.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombel JF, D’haens G, Lee WJ, Petersson J, Panaccione R. Outcomes and strategies to support a treat-to-target approach in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:254–66. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuñez P, Mahadevan U, Quera R, Bay C, Ibañez P. Treat-to-target approach in the management of inflammatory Bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:312–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frias-Gomes C, Torres J, Palmela C. Intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease: A valuable and increasingly important tool. GE Port J Gastroenterol? 2021;29:223–39. doi: 10.1159/000520212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilmi I, Jaya F, Chua A, Heng WC, Singh H, Goh KL. A first study on the incidence and prevalence of IBD in Malaysia—results from the Kinta Valley IBD Epidemiology Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:404–9. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn's and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokhtar NM, Nawawi KN, Verasingam J, Zhiqin W, Sagap I, Azman ZAM, et al. A four-decade analysis of the incidence trends, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease patients at single tertiary centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19((Suppl 4)):550. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6858-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;315:514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daperno M, D’Haens G, Van Assche G, Baert F, Bulois P, Maunoury V, et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn's disease: The SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–12. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, et al. Reliability and initial validation of the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:987–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corte C, Fernandopulle N, Catuneanu AM, Burger D, Cesarini M, White L, et al. Association between the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) and outcomes in acute severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:376–81. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bujang MA, Adnan TH. Requirements for minimum sample size for sensitivity and specificity analysis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:YE01–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18129.8744. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/18129.8744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panés J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, García-Sánchez V, Gisbert JP, Martínez de Guereñu B, et al. Systematic review: The use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:125–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strobel D, Goertz RS, Bernatik T. Diagnostics in inflammatory bowel disease: Ultrasound. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3192–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bavil AS, Somi MH, Nemati M, Nadergoli BS, Ghabili K, Mirnour R, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of bowel wall thickness and intramural blood flow in ulcerative colitis. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2012;2012:370495. doi: 10.5402/2012/370495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maconi G, Parente F, Bollani S, Cesana B, Porro GB. Abdominal ultrasound in the assessment of extent and activity of Crohn's disease: Clinical significance and implication of bowel wall thickening. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1604–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Futagami Y, Haruma K, Hata J, Fujimura J, Tani H, Okamoto E, et al. Development and validation of an ultrasonographic activity index of Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1007–12. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parente F, Maconi G, Bollani S, Anderloni A, Sampietro G, Cristaldi M, et al. Bowel ultrasound in assessment of Crohn's disease and detection of related small bowel strictures: A prospective comparative study versusxray and intraoperative findings. Gut. 2002;50:490–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parente F, Greco S, Molteni M, Cucino C, Maconi G, Sampietro GM, et al. Role of early ultrasound in detecting inflammatory intestinal disorders and identifying their anatomical location within the bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1009–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pascu M, Roznowski AB, Müller HP, Adler A, Wiedenmann B, Dignass AU. Clinical relevance of transabdominal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with inflammatory bowel disease of the terminal ileum and large bowel. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:373–82. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bru C, Sans M, Defelitto MM, Gilabert R, Fuster D, Llach J, et al. Hydrocolonic sonography for evaluating inflammatory bowel disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:99–105. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.1.1770099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migaleddu V, Scanu AM, Quaia E, Rocca PC, Dore MP, Scanu D, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonographic evaluation of inflammatory activity in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:43–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez MJ, Ripollés T, Paredes JM, Blanc E, Martí-Bonmatí L. Assessment of the extension and the inflammatory activity in Crohn's disease: Comparison of ultrasound and MRI. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:141–8. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bremner AR, Griffiths M, Argent JD, Fairhurst JJ, Beattie RM. Sonographic evaluation of inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective, blinded, comparative study. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:947–53. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maaser C, Petersen F, Helwig U, Fischer I, Roessler A, Rath S, et al. Intestinal ultrasound for monitoring therapeutic response in patients with ulcerative colitis: Results from the TRUST and UC study. Gut. 2020;69:1629–36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ungaro R, Colombel JF, Lissoos T, Peyrin-Biroulet L. A treat-to-target update in ulcerative colitis: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:874–83. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wetwittayakhlang P, Lontai L, Gonczi L, Golovics PA, Hahn GD, Bessissow T, et al. Treatment targets in ulcerative colitis: Is it time for all in, including histology? J Clin Med. 2021;10:5551. doi: 10.3390/jcm10235551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips M, Patel A, Meredith P, Will O, Brassett C. Segmental colonic length and mobility. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97:439–44. doi: 10.1308/003588415X14181254790527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinoshita K, Katsurada T, Nishida M, Omotehara S, Onishi R, Mabe K, et al. Usefulness of transabdominal ultrasonography for assessing ulcerative colitis: A prospective, multicenter study. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:521–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-01534-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faure C, Belarbi N, Mougenot JF, Besnard M, Hugot JP, Cézard JP, et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of inflammatory bowel disease in children: Comparison with ileocolonoscopy. J Pediatr. 1997;130:147–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pradel JA, David XR, Taourel P, Djafari M, Veyrac M, Bruel JM. Sonographic assessment of the normal and abnormal bowel wall in nondiverticular ileitis and colitis. Abdom Imaging. 1997;22:167–72. doi: 10.1007/s002619900164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reimund JM, Jung-Chaigneau E, Chamouard P, Wittersheim C, Duclos B, Baumann R. Diagnostic value of high resolution sonography in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miao YM, Koh DM, Amin Z, Healy JC, Chinn RJ, Zeegen R, et al. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging assessmentof active bowel segments in Crohn's disease. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:913–8. doi: 10.1053/crad.2002.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziech ML, Hummel TZ, Smets AM, Nievelstein RA, Lavini C, Caan MW, et al. Accuracy of abdominal ultrasound and MRI for detection of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1370–8. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dilillo D, Zuccotti GV, Galli E, Meneghin F, Dell’Era A, Penagini F, et al. Noninvasive testing in the management of children with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:586–91. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1604799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonen C, Surmelioglu A, Kochan K, Ozer S, Aslan E, Tilki M. Impact of intestinal ultrasound with a portable system in the management of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Rep. 2021;9:418–26. doi: 10.1093/gastro/goaa088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bots S, Nylund K, Löwenberg M, Gecse K, D'Haens G. Intestinal ultrasound to assess disease activity in ulcerative colitis: Development of a novel UC-ultrasound index. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1264–71. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asthana AK, Friedman AB, Maconi G, Maaser C, Kucharzik T, Watanabe M, et al. The failure of gastroenterologists to apply intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease in the Asia-Pacific: A need for action. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:446–52. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajagopalan A, Sathananthan D, An YK, Van De Ven L, Martin S, Fon J, et al. Gastrointestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease care: Patient perceptions and impact on disease-related knowledge. JGH Open. 2019;4:267–72. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinto J, Azevedo R, Pereira E, Caldeira A. Ultrasonography in gastroenterology: The need for training. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2018;25:308–16. doi: 10.1159/000487156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bae SI, Kim YS. Colon cancer screening and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:509–15. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.6.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]