Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy relies on T cells engineered to target specific tumor antigens such as CD-19 in B-cell malignancies. In this setting, the commercially available products have offered a potential long-term cure for both pediatric and adult patients. Yet manufacturing CAR T cells is a cumbersome, multistep process, the success of which strictly depends on the characteristics of the starting material, i.e., lymphocyte collection yield and composition. These, in turn, might be affected by patient factors such as age, performance status, comorbidities, and previous therapies. Ideally, CAR T-cell therapies are a one-off treatment; therefore, optimization and the possible standardization of the leukapheresis procedure is critical, also in view of the novel CAR T cells currently under investigation for hematological malignancies and solid tumors. The most recent Best Practice recommendations for the management of children and adults undergoing CAR T-cell therapy provide a comprehensive guide to their use. However, their application in local practice is not straightforward and some grey areas remain. An Italian Expert Panel of apheresis specialists and hematologists from the centers authorized to administer CAR T-cell therapy took part in a detailed discussion on the following: 1) pre-apheresis patient evaluation; 2) management of the leukapheresis procedure, also in special situations represented by low lymphocyte count, peripheral blastosis, pediatric population <25 kg, and the COVID-19 outbreak; and 3) release and cryopreservation of the apheresis unit. This article presents some of the important challenges that must be faced to optimize the leukapheresis procedure and offers suggestions as to how to improve it, some of which are specific to the Italian setting.

Keywords: CAR T-cell therapy, cryopreservation, leukapheresis, timing

INTRODUCTION

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy relies on T cells engineered to express a CAR targeting a specific tumor antigen1. This form of autologous immunotherapy is now an option for blood cancers, especially B-cell malignancies (non-Hodgkin lymphomas)2–6, adult and pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)7, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)8, with unprecedented response rates and durability, offering a potential long-term cure9–11. So far, CD19-specific autologous CAR T-cell therapies have been approved for aggressive B-cell lymphoma12–14, B-ALL13, multiple myeloma15, and mantle cell lymphoma16. However, efforts are underway to develop effective CAR T cells also for other hematological malignancies and solid tumors17,18.

There are several CAR T-based treatments already in use in Europe: axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta, Kite Pharma/Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA), indicated for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), after ≥2 lines of systemic therapy2; tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), indicated for the treatment of pediatric and young adult patients up to 25 years of age with B-ALL who are refractory, in relapse after transplant, or in second or later relapse7, and of adult patients with R/R DLBCL after ≥2 lines of systemic therapy4; brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus, Kite Pharma/Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA), used to treat adults with R/R mantle cell lymphoma16; idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma, Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharma, Dublin, Ireland), recommended for adult patients with R/R multiple myeloma15; and lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi, Juno Therapeutics Inc./Bristol-Myers Squibb, Seattle, WA, USA)14 approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency. The FDA has recently granted approval for the use of ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Cilta-cel; Janssen, Raritan, NJ, USA) in the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL)19.

Manufacturing CAR T cells is a labor-intensive, multistep procedure that involves collection of autologous cells by leukapheresis, T-cell selection and activation, ex vivo CAR loading and T-cell expansion, end-of-process formulation, cryopreservation, and intravenous infusion. It is further hampered by the fact that patients are often heavily pre-treated and have a low absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), and their clinical status may substantially deteriorate in the period required for the manufacturing cycle to be completed. Furthermore, complex administrative and logistic challenges must be faced to ensure effective delivery of CAR T-cell therapies in clinical practice20.

Leukapheresis is critical to ensure the success of CAR T-cell manufacturing21,22. Some patient factors, such as age, performance status, comorbidities, and previous therapies, affect the characteristics of the source material (e.g., T-cell fitness, ALC, and composition). These represent major determinants of the yield and composition of lymphocytes, and downstream manufacturing success, especially cell expansion22–30. To date, the reported rate of manufacturing failure with product-related issues ranges between 4 and 7.6%4,7,31.

Cells for CAR T-cell therapies are collected from heavily pre-treated, non-mobilized patients.

Although the procedure shares some elements with hematopoietic progenitor cell and donor lymphocyte harvesting, important differences remain, and these warrant further research. The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy and EBMT (JACIE) have recently released Best Practice recommendations for the management of children and adults undergoing CAR T-cell therapy32. Nevertheless, their application in local practice is not straightforward and some grey areas remain, for instance regarding the best timing and modalities for harvesting. To address some of the most urgent issues, an Italian Expert Panel of apheresis specialists and hematologists from the centers authorized to administer CAR T-cell therapy from pediatric and adult patients met to share their experiences and opinions on the topic. More recently, a review related to these issues revealed that the scientific literature on the subject is still lacking33.

This article summarizes the challenges and opportunities presented by this therapeutic approach in the form of expert suggestions to help optimize the collection of apheresis products intended for CAR T-cell treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

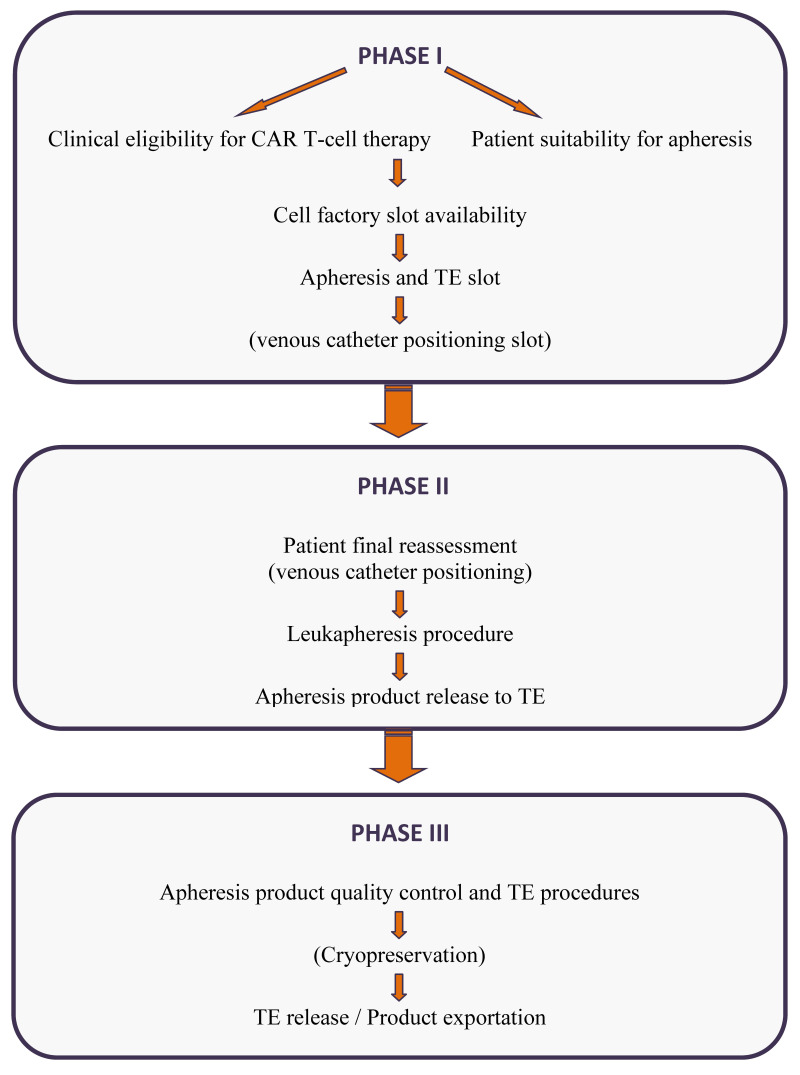

An Italian Expert Panel composed of 15 apheresis specialists and hematologists from the centers authorized to administer CAR T-cell therapy convened in two meetings: a face-to-face meeting in December 2019 in Rome, Italy, and an online meeting in September 2020. In the first meeting, two specialists reported their experience and the technical and practical problems encountered in collecting cellular products for CAR T-cell therapy from adult and pediatric patients. The EBMT and JACIE recommendations, and the main literature on the topic were reviewed. The representatives from each center discussed their opinions in the light of their personal and local experience. The summary of the discussion was shared in the second online meeting, and panel agreement was achieved on the issues reported in the following phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the leukapheresis management process for Car T-cell therapy

Subsequent actions that may be required are reported in brackets. TE: tissue establishment.

Phase I: pre-apheresis patient evaluation of eligibility for CAR T-cell therapy and suitability for the leukaphereses procedure;

Phase II: management of the leukapheresis procedure;

Phase III: release and cryopreservation of the apheresis unit.

The investigation into each issue reflected the clinical experience of the individual experts. All the individual opinions of the committee members were taken into consideration and thoroughly discussed to reach a consensus. However, when neither a unanimous nor shared agreement could be reached to make a formal opinion, the point of discussion is reported as an open question.

Phase I: pre-apheresis patient evaluation

CAR T-cell therapy is only allowed in accredited centers; so far, in Italy, there are almost 30 centers authorized to provide CAR T cells32,34. The implementation of CAR T-cell therapy requires an appropriately trained multidisciplinary team. The preliminary patient evaluation should include hematologists or oncologists, apheresis specialists, anesthesiologists and neurologists, as well as nursing staff (clinical and apheresis nurses), all with proven, documented experience in CAR T-cell therapy in each specialization. The actions that should be taken for the pre-leukapheresis work-up, the reference facilities, and the panel’s suggestions are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

The work-up to be completed before leukapheresis

| Work-up | Reference facility | Expert Panel’s suggestions |

|---|---|---|

Eligibility for CAR T-cell therapy

|

|

|

Patient suitability for leukapheresis

|

|

|

| Timely apheresis |

Only in selected cases

|

CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; EBMT: European Bone Marrow Transplantation; JACIE: Joint Accreditation Committee of the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy and EBMT; AIFA: Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco; CVC: central venous catheter; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; MNC: mononuclear cells; HTLV: human T lymphotropic virus; ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Eligibility for CAR T-cell therapy

Eligibility for CAR T-cell therapy is determined within the CAR T-cell unit by the hematologist (or oncologist), and strictly depends on the patients’ medical history and condition, with particular regard to the performance status, the underlying hematological disease, and previous treatments. The panel agreed on the criteria recently defined by the Best Practice recommendations of EBMT-JACIE and the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) for selecting patients eligible for CAR T-cell therapy32,35,36.

Suitability for the leukapheresis procedure

Patient suitability for the leukapheresis procedure should be determined by the staff in the apheresis facility after evaluation of a comprehensive set of information, as summarized in Table I. EBMT-JACIE has defined a minimum set of tests to be performed at screening to assess organ function and eligibility, together with indications on wash-out periods between previous chemotherapy regimens/corticosteroids and leukapheresis32. The panel agreed with the recommendations, but added specific indications based on the Italian experience, as mentioned earlier.

Timing for patient evaluation and organizational/logistic considerations

Experts highlighted the usefulness of preliminary patient evaluation by the apheresis specialists, medical doctor and nurses with proved experience in lymphocyte apheresis (similar to established procedures for hematopoietic stem cell collection) to identify possible clinical situations that may impede cell collection on the scheduled day and to carefully evaluate patients with comorbidities (e.g., cardiac diseases) or who are at medical risk for the collection procedure. Considering the organizational and logistic differences among centers, and according to the panel’s opinion, the establishment of protocols defining the timeline for sharing information between clinicians and apheresis specialists is crucial. The information should be available within no more than 30 days after the procedure, acknowledging that the communication of such information is particularly challenging when patients are referred to a designated center from another institution. In this regard, the creation of a hub-spoke network model would facilitate the information flow.

It could be useful to identify a co-ordinator, especially when the multidisciplinary team members belong to different departments. The co-ordinator should have proven experience in CAR T-cell therapy and could be chosen from among the medical or nursing staff who have a managerial role within the institution. The co-ordinator will be responsible for co-ordinating the activities of:

the onco-hematology unit that enrols the patient;

the manufacturer that identifies the time slot available for processing the material;

the apheresis unit that evaluates patient suitability for apheresis collection and venous access (when necessary, the latter should be in collaboration with the anesthesiologist) and then conduct the apheresis;

the Tissue Establishment (TE) for laboratory and export requirements.

The co-ordinator should also assess the correctness of the wash-out periods from previous therapies and help in updating the apheresis facility on the patient’s clinical condition in a timely manner, especially for critical patients.

Previous therapies and wash-out periods

The issue of wash-out from previous therapies is particularly important because certain cytotoxic therapies (e.g., fludarabine, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, polyethylene glycol-asparaginase, lenalidomide and bendamustine) preferentially deplete early lineage cells and more time is required for lymphocyte recovery28,37–39. In the panel’s opinion, performing timely apheresis could be a useful option in selected cases. (See the section on timely apheresis.)

The EBMT-JACIE recommendations have established the wash-out periods following different salvage treatments before starting leukapheresis: time for recovery from cytopenia is essential and, in the case of systemic corticosteroids, the target of ALC >0.2×109/L and of CD3+ >150/mm3 must be reached32. A wash-out period of at least one week is recommended after antibody-drug conjugates and bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE)40.

Blood and coagulation screening tests

Patients are considered eligible for CAR T-cell therapy based on clinical indication, toxicity evaluation, and reimbursement criteria. A possible barrier to the access of patients to therapy is represented by the stringent criteria for blood tests established by the AIFA for reimbursement purposes: for example, the AIFA has set the cut-off for platelet (PLT) count at values >75×109/L, whereas the EBMT-JACIE recommends a PLT count >30×109/L.

Regarding the procedure for patients with a low PLT count, it is advisable to postpone, if possible, leukapheresis by at least one week in order to optimize apheresis performance, reduce the risk associated with the procedure, and achieve the target collection. Sometimes patients are evaluated 10–15 days before collection, therefore, the only option might be transfusion before apheresis if necessary (e.g., hemoglobin [Hb] ≤8 g/dL in stable adult patients and PLT ≤30×109/L) to establish a good interface during the collection and to achieve the target collection, especially if large volume leukaphereses are needed in patients with very low lymphocyte/CD3+ counts.

Similar to the PLT count, low white blood cell (WBC) and CD3+ lymphocyte counts must be considered in view of apheresis collection41. The panel proposed adding alerts if the patient’s values are lower than expected (i.e., when WBC <1×109/L and ALC <0.2×109/L), suggesting a 7–10-day delay, when possible, to prolong the wash-out period from previous therapies and allow bone marrow recovery in order to improve the collection.

The experts also emphasised the importance of distinguishing the different trends in values according to age and underlying disease when determining patient suitability for cell collection42. For patients with hematocrit (Hct) values <24–25%, a red blood cell (RBC) transfusion is advisable to ensure the hemodynamic compliance and improve the formation of the cellular interface in the blood cell separator. In the pediatric setting, the suggested values for Hb and Hct are >9 g/dL and >30%, respectively, and in the case of very-low-weight pediatric patients (weight <25 kg), blood priming of the cell separator is recommended using compatible irradiated packed RBCs42.

Blood cell counts vary widely among patients with leukemia or lymphoma. In the case of ALL, blood test values may change rapidly within 30 days and, thus, even if the patient’s blood cell counts have been reviewed, it may be useful to indicate in the work-up that the peripheral blood immunophenotype and blood parameters, including blast and CD3+ lymphocyte count, should be reassessed 2–3 days before collection.

The panel acknowledged the importance of having the pre-apheresis values of mononuclear cells (MNC), lymphocytes, and possibly CD3+ cells available in order to estimate the blood volume to be processed; these may help decision making in emergency situations and to satisfy the collection requirements for the manufacturing stage (see below).

Infectious status and timing for reassessment before the procedure

EMBT-JACIE has detailed the minimum tests for infectious diseases required: hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV). According to recommendations, these tests, which are mandatory in some countries, must be performed “within 30 days of leukapheresis and the results must be available at the time of collection and shipment”41.

According to Italian legislation43, lymphocyte donors must meet the same requirements as for human blood and blood components. Every donation must undergo the biological qualification tests established by the current legislation for human blood and blood components, and, with regard to the infectiology tests, in the case of autologous cells or tissue collected for storage or culture, it is necessary to perform the minimum set of laboratory tests as for living allogeneic donors44. These tests must be completed within 30 days of collection and include serum tests for the presence of anti-HIV 1–2 antibodies (Abs), HBsAg, anti-HBc Abs, anti-HCV Abs, and syphilis.

The panel proposed recommending HTLV testing only on the basis of anamnestic criteria according to Italian legislation (i.e., based only on risk assessment for patients either born or living in areas of high incidence of HTLV infection, or if their parents and/or sexual partner originated from those areas), or if requested by the cell factory.

The Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) and the nucleic acid test (NAT) for HIV/HCV/HBV are mandatory44; the latter must be performed on the day of collection at the latest for biological qualification of the product to be released. In the panel’s opinion, the CAR T-cell procedure should be made simpler and more flexible, and minimal tests for infectious diseases should be clarified by the legislator for this emergent use of human cells.

Concomitant therapies

The experts agreed that concomitant therapies should be thoroughly reviewed at the time of patient evaluation. The opinion of the main panel was that particular attention should be paid to the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi). These are mainly contraindicated for therapeutic apheresis (i.e., plasma exchange) because they may enhance the hypotensive effect of bradykinin45, or of other concomitant anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs and therapies interfering with serum electrolytes, especially calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and magnesium (Mg) (the latter worsens during citrate anticoagulation). Although also the ACEi reactions are much more frequent when using devices that involve a lot of blood contact with artificial surfaces (such as filtration systems in general), in all the centers, when possible, ACEi are to be either avoided or switched with antihypertensive agents with different mechanisms of action at least 48 hours before the scheduled collection date.

Venous access assessment and blood flow

According to the panel, evaluation and planning of venous access placement should be the responsibility of medical or nursing staff with specific expertise, possibly even of the co-ordinator. Peripheral access should be preferred over central access, because it is less invasive, but the choice depends on the patient’s profile (adult vs pediatric)32.

A crucial parameter for leukapheresis success is blood flow, which depends on an adequate venous access and on the weight/age of the patient; <1–2 mL/kg/min in children and <70 mL/min in adults is recommended, as in stem cell apheresis46.

The panel emphasized that the decision as to whether to use a central venous catheter (CVC) could be much more important in candidates for CAR T-cell therapy than in those undergoing autologous stem cell collection. In the former case, the CVC option is more often considered because the collection is a one-off procedure and may take longer, as in the case of a low ALC or peripheral blastosis; in younger children, it may even require sedation.

Central catheter insertion should be performed by anesthesiologists or a CVC team expert in leukapheresis catheters. The panelists’ experience with peripheral catheters is limited, and they agreed on the need for more data. They also recommended that a group of health care professionals trained in how to set up a central venous access should be established, to be called upon when needed.

Timely apheresis

Timely apheresis may be useful in selected patients who have to undergo cytotoxic therapy. The best timing for collection remains a matter of debate. In patients with lymphoma, the harvest should be completed before starting salvage therapy, for example, in patients with high-risk relapse or refractory disease47. In these cases, timely apheresis might be particularly beneficial before salvage treatment, reducing the risk of compromising lymphocyte fitness that may occur in heavily treated patients. In patients diagnosed with high-risk disease, first-line therapy varies according to the treatment center. Thus, it is the panel’s opinion that in the context of a hub-and-spoke model the reference site should indicate the regimens that affect lymphocyte quantity and quality, so that the other centers may appropriately plan the timing of collection for each candidate for CAR T-cell therapy.

In the setting of ALL, timely apheresis may be useful in high-risk patients based on age (18–25 years) and on any unfavorable prognostic characteristics at baseline. It should be performed: 1) when the results from monitoring minimal residual disease are unsatisfactory; 2) at the end of induction therapy; or 3) at the end of the first consolidation therapy. For ethical and logistic reasons (linked to storage and non-use of a significant portion of stored products), more data are needed to clarify the actual value of timely apheresis before its use in clinical practice.

Subsequent to early well-timed lymphocyte apheresis, the collected material undergoes cryopreservation. This processing step can be critical due to a possible divergence between the manufacturer’s instructions for the collection of the apheresis material and the method of cryopreservation. It is, therefore, strongly recommended to make this two-step procedure rigorous and consistent in order to collect usable material.

Phase II: management of the leukapheresis procedure

The work-up that must be completed on the day scheduled for blood collection and the panel’s suggestions are summarized in Table II (Phase II).

Table II.

Phase II: the work-up to be completed on the day of blood collection, with the panel’s suggestions

| Work-up | Panel’s suggestions |

|---|---|

| • Informed consent for leukapheresis | • To be obtained before every collection |

| • Pre-collection blood test | • Peripheral blood hemocytometric parameters with differential MNC count, ANC and CD3+ counts; coagulation tests, electrolytes (Ca/K/Mg) |

| • Biological qualification of the product | • Check the validity of the infectious disease tests and additional tests required by local regulations |

| • Calculation of the volume to be processed | • Product sampling during collection |

| • Possibility of using different cell separators and validated software | • Protocol with low extracorporeal volume preferred in smaller children |

| • Management of anticoagulation and citrate toxicity | • ACD-A+ heparin (if there is no contraindication) in pediatric population; use of activated clotting time device (for real-time monitoring) |

| • Management of interruption/CVC in emergency situations | • CVC team immediately available in an emergency |

| • Possibility of a second collection | • Check cell factory slot availability |

MNC: continuous mononuclear cells; ANC: absolute neutrophil count; ACD-A: acid citrate dextrose solution A; CVC: central venous catheter.

Informed consent for leukapheresis

This consent form differs from that required for the CAR T-cell therapy protocol and must be obtained before leukapheresis; in the case of multiple collections, consent must be obtained each time. However, it would be appropriate to provide patients with some explanatory material and possibly the consent form itself, so that they have enough time to process and understand all the information. The consent form varies according to each institution’s procedures.

Pre-collection blood test

In addition to the suggestions set out in Table II, on the day scheduled for leukapheresis, it is important to check the MNC/ALC count and, possibly, the CD3+ cell count before apheresis. Moreover, it is crucial to complete this count during the pre-collection, or at least to have these results as soon as possible (the panel believes this should be within an hour of collection) to optimize the leukapheresis, particularly in special cases (Table III), and estimate the total blood volume that must be processed to achieve a specific target. The equation to calculate the volume to be processed based on the collection efficiency percentage (CE%) of the cell separator is as follows48–50:

Table III.

Panel’s suggestions for the management of special case

| Special case | Panel’s suggestions |

|---|---|

| Low lymphocyte count |

|

| Peripheral blastosis |

|

| Pediatric population <25 kg |

|

| COVID-19 outbreak |

|

RBCs: red blood cells; PLTs: platelets; ACD-A: acid citrate dextrose solution A; EBMT: European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Collection efficiency is specific to the institution, apheresis device and software. All authors were in agreement about the use of the following formula based on their experience with peripheral blood stem cells51:

TBV=volume processed (mL) – acid citrate dextrose volume (mL).

These calculations are particularly important in low-weight pediatric patients whose total blood volume is <1,000 mL. Based on the clinical evaluation of the patient, it is suggested that a maximum of 5–6 blood volumes should be processed49. Compared with patients eligible for autologous transplantation, those eligible for CAR T-cell therapy are usually heavily pre-treated and may have received highly lymphocytotoxic treatments such as bendamustine; thus, lymphocyte count and fitness may be low. Therefore, after considering the patient’s clinical status and previous therapies, it would be reasonable to process multiple volumes to allow cryopreservation and further manufacturing in case of failure. Although some sites are already implementing the collection of additional volumes, not all panelists agreed on this practice. Some experts argued against collecting multiple volumes from patients with acute, progressive disease who may not have the chance to undergo an additional apheresis, because it is likely they will not be eligible for CAR T-cell therapy regardless of the feasibility of collecting additional volumes. In the future, it will be important to verify the presence of specific immunophenotypes and peripheral blasts (which, in ALL patients, may be up to 60% of blood cells) with regard to collection efficiency and manufacturing failure22.

The protocol followed in some centers relies on sampling the harvest during the collection to refine the calculation of the volumes to be processed; these should be taken from the sample bulbs of the apheresis bag, if available, and if permitted by the manufacturing facility. This is an effective method to reduce the collection time and, thus, the risk of adverse events and citrate toxicity, especially in low-weight children. As the separators currently in use are usually highly efficient, it is common practice to process a lower volume than that calculated by the formula.

It is also important to perform coagulation tests and assess electrolytes (Ca, K, and Mg).

According to the EBMT, the ALC should be >0.200×109/L, with a higher count in small children.

However, real-world data demonstrate that manufacturing T cells is possible even if the CD3+ cell count is below the target45, but these patients must be considered at risk of inadequate yield; in some cases, processing a greater volume (with the possibility of cryopreserving the harvest) may increase the yield of CD3+ cells and provide an adequate collection21. However, there is a limit to the blood volume to be processed: if >12 L, the collection becomes too demanding for the patient in terms of the time required, the amount of acid citrate dextrose (ACD), and the peripheral blood parameters (e.g., thrombocytopenia).

All the experts agreed that, after the COVID-19 outbreak, the EBMT recommendations52 should be followed.

Table III summarizes the main suggestions provided by the panel with regard to the management of the following special cases:

low lymphocyte count;

peripheral blastosis;

pediatric population <25 kg; and

the COVID-19 outbreak.

Biological qualification of the product

The EBMT-JACIE recommendations pointed out that the manufacturers’ requirements for quality control are limited and local requirements may be more stringent31. Moreover, there may be differences between the US and EU regulatory agencies. Reasonable quality assurance must rely on accredited and validated testing methods, and should include:

infectiology tests (HIV, HCV, HBV, TPHA serology, NAT);

sterility testing (aerobic, anaerobic, fungi) and hemocytometric parameters such as WBC count with differential counts of MNC and of viable CD3+ and CD45+32; and

estimation of red blood cell contamination or Hct% and PLT contamination to verify the purity (MNC%) of the collection. Accredited centers must comply with the Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT)-JACIE requirements regarding the release of the starting material.

Possibility of using different cell separators and validated software

Several devices and systems are currently on the market. Companies may indicate preferences, but the selection of technology depends on the local experience, permits, and regulatory approval status of each device and system32.

According to the panel, separators and software for low extracorporeal volume should be preferred in very low-weight children. Sometimes, even if a low extracorporeal volume is present in a discontinuous semi-automated collection method, continuous collection software with higher collection efficiency is preferred to achieve the target in a shorter time and to reduce the risk of adverse events.

Management of anticoagulation and citrate toxicity

Adequate anticoagulation is particularly important at the beginning of cell collection. According to the EBMT-JACIE recommendations, anticoagulation is achieved with an initial acid citrate dextrose solution A (ACD-A) at a ratio ranging from 1: 10 to 1: 12, after which the ratio may be reduced for the remainder of the procedure. Most manufacturers discourage adding heparin because it may interfere with some of the downstream processing steps31. However, based on the experience of some centers with lymphocyte donors, in the absence of contraindications for heparin use, and if the technology specifications allow it, the best combination of anticoagulants seems to be heparin plus ACD-A, at least in pediatric populations (with the possibility of reducing the dose of ACD-A and related toxicity)53,54.

In clinical practice, some experts use an activated clotting time device that allows the coagulation status to be monitored in real time, adjusting the amount of heparin accordingly, and checking the electrolytes (urgent venous hemogasanalysis) for adequate replacements. In each collection center, adoption of a standard operating procedure (SOP) for citrate toxicity treatment and prophylaxis is advisable.

Phase III: release and cryopreservation of the apheresis unit

To release the product from the collection center to the TE, and from the TE to the cell factory, the information reported in Table IV should be provided. These criteria must be defined in the SOP at each site and must include manufacturing-related information according to the pharmaceutical company’s instructions. The main differences regard the release of fresh vs cryopreserved collection products.

Table IV.

Information required for the release of the product to the tissue establishment

| Information | Panel’s suggestions |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-- |

|

|

|

-- |

|

-- |

TNC: total nucleated cells; MNC: mononuclear cells; ACD-A: acid citrate dextrose solution A; Hct: hematocrit; RBC: red blood T cells; PLT: platelets.

In the panel’s opinion, there is no need for any more stringent criteria because all authorized collecting centers use validated separators that provide good-quality products, with high purity (MNC%) and minimal PLT contamination, and factories do not require specific cut-offs. However, the experts agreed that the pharmaceutical companies should specify more precisely the minimum CD3+ count required with respect to the total nucleated cell count because this can be misleading, (especially in the case of peripheral blastosis). A more specific indication of minimal harvest volume with or without autologous plasma could also be useful. It is common practice for the site TE to perform the microbiology tests even when not requested by the manufacturer.

The ISBT 128 and Eurocode coding and labeling operation should be respected. Any additional requirements for labeling accessories or accompanying information printed or recorded in a specific factory software should be standardized between the companies. The panel believes that any manual compilation or transcription could be a source of error.

Most separator companies have implemented apheresis traceability software, so that technical apheresis reports can be recorded directly in most software and hospital archives without the need for manual transcription. This procedure must also be validated at each collection center as part of good quality practice. Therefore, most authors believe that non-manual traceability procedures should be followed and that these should be considered the appropriate information source also by the factories.

Indications for possible cryopreservation

Co-ordinating the first available manufacturing slot is one of the factors limiting the availability of commercial CAR T-cell therapies, so leukapheresis must be scheduled with the manufacturer. The viability of fresh material decreases over time so the manufacturing process must begin without delay within a strictly limited time window (24–48 hours)55.

Cryopreservation has important advantages, such as maximum flexibility of patient management, especially regarding the optimal timing of collection based on the patient’s health and needs (without waiting for a manufacturing slot), and extended storage in cases of delays in shipping or manufacturing. However, in the long term, the actual possibility of occupying cryogenic spaces with unused lymphocyte apheresis must be considered; this inconvenience does not occur with the shipment of fresh material to the cell factory. In the case of tisagenlecleucel, the leukapheresis material has been cryopreserved since the start of clinical trials56. Preliminary data support the practice of cryopreserving starting material because no relevant difference has been found in terms of persistence and clinical response in vivo between cryopreserved and fresh collections57. With regard to the cryopreservation method and targets (cryoprotectant medium, type of bags, WBC concentration, etc.), it is advised to follow internal validated procedures and the indications of the companies to guarantee the quality and viability of the product. To release a unit that must be cryopreserved, the panel concluded that each manufacturer should use the same criteria for every single product. Even a high neutrophil count should not exclude the unit from cryopreservation, release, and possible manufacture.

CONCLUSIONS

Manufacturing CAR T cells is a cumbersome process that requires adequate starting material.

Ideally, CAR T-cell therapies are a one-off treatment and, therefore, optimization of the leukapheresis procedure is of the utmost importance, also in view of the expansion of the therapeutic indications to oncological settings beyond B-cell malignancies58. Variability in apheresis can occur not only among patients, but also from differences between devices, operators, institutions, and the healthcare systems of each country.

Therefore, the expert panel has thoroughly revised and discussed the work-up for leukapheresis (from pre-apheresis patient evaluation to management of the collection) as well as the management and cryopreservation of harvested units before their release. The panel’s efforts have allowed a common approach to leukaphereses methods for CAR T-cell manufacturing to be set up and shared.

This article illustrates the current challenges in optimizing the apheresis procedure for CAR T-cell treatment and provides suggestions for clinical practice. Consensus was reached on the need for standardized therapeutic products, released by authorized and good manufacturing practice qualified collection centers for CAR T-cell therapy, as for other blood components.

Standardization is important both to share data among different centers and to guarantee adherence to international regulations. To achieve this, factories must also all work together to establish and implement common procedures. It is the authors’ opinion that the small differences among companies with regard to targets, volumes, labeling and accompanying information can result in errors that could alter the outcome of the manufacturing process, and ultimately, the safety and efficacy of the therapy for the patient.

The authors shared a real practice approach. However, solid evidence is still lacking, as is the availability of good retrospective analyses for specific clinical settings; consequently, in these cases, the panel was unable to provide specific guidelines.

In the future, it will be important to use the knowledge gained to improve clinical practice. The following initiatives would be useful. Firstly, real-world data on the correlation between specific lymphocyte subpopulations and blasts, and between collection yield and the manufacturing failure rate should be collected. Secondly, more data on the use of different devices for venous access, and peripheral vs central access should be provided. Finally, it is the general opinion that manufacturing failure depends on pre-collection treatments. However, centers should, in collaboration with the pharmaceutical companies, collect information on failures and unmet specifications to explore possible ways to improve the characteristics of these products. Site procedures could then be adapted accordingly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Carlo Messina, Antonio Vendramin and Paola Di Matteo from Novartis Farma SpA, Italy, for their support. Writing and editing assistance was provided by EDRA SpA, Italy. This work was supported by Novartis Farma SpA, Italy.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

All Authors had full control of the content and helped define the final decisions regarding all aspects of this article.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

VB, RC, PC, SG and RM have served on the Advisory Board for Novartis. The other Authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:64–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, Miklos DB, Lekakis LJ, Oluwole OO, et al. Long term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:31–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson JS, Gordon LI, Palomba ML, Lunning MA, Arnason JE, Forero-Torres A, et al. Updated safety and long term clinical outcomes in TRANSCEND NHL 001, pivotal trial of lisocabtagene maraleucel (JCAR017) in R/R aggressive NHL. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15 Suppl):7505. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, Lunning MA, Wang M, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396:839–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:439–448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wierda WG, Dorritie KA, Munoz J, Stephens DM, Solomon SR, Gillenwater HH, et al. Transcend CLL 004: Phase 1 cohort of lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) in combination with ibrutinib for patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) Blood. 2020;136:39–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-140622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frigault MJ, Maus MV. State of the art in CAR T cell therapy for CD19+ B cell malignancies. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1586–1594. doi: 10.1172/JCI129208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anagnostou T, Riaz IB, Hashmi SK, Murad MH, Kenderian SS. Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e816–826. doi: 10.1016/S23523026(20)30277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitale C, Strati P. CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical trials and real-world experiences. Front Oncol. 2020;10:849. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yescarta-epar-product-information_en.pdf [Internet] [Accessed on 27/11/2020]. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/yescarta.

- 13.Kymriah-epar-product-information [Internet] [Accessed on 27/11/2020]. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/Kymriah.

- 14.Breyanzi-lisocabtagene-maraleucel, gene therapy products.[Internet] [Accessed on 27/11/2020]. Available from https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/breyanzi-lisocabtagene-maraleucel.

- 15.Abecma Product information. [Accessed on 27/11/2020]. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/abecma-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- 16.Tecartus product information. [Accessed on 27/11/2020]. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tecartus-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- 17.Haslauer T, Greil R, Zaborsky N, Geisberger R. CAR T-cell therapy in hematological malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8996. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang ZZ, Wang T, Wang XF, Zhang YQ, Song SX, Ma CQ. Improving the ability of CAR-T cells to hit solid tumors: challenges and strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2022;175:106036. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summary basis for regulatory action. [Internet] [Accessed on 27/11/2020]. Available at: www.fda.gov/media/156999/download.

- 20.Perica K, Curran KJ, Brentjens RJ, Giralt SA. Building a CAR garage: Preparing for the delivery of commercial CAR T cell products at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fesnak A, Lin C, Siegel DL, Maus MV. CAR-T cell therapies from the transfusion medicine perspective. Transfus Med Rev. 2016;30:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen ES, Stroncek DF, Ren J, Eder AF, West KA, Fry TJ, et al. Autologous lymphapheresis for the production of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Transfusion. 2017;57:1133–1141. doi: 10.1111/trf.14003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bersenev A. CAR-T cell manufacturing: time to put it in gear. Transfusion. 2017;57:1104–1106. doi: 10.1111/trf.14110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuazon SA, Li A, Gooley T, Eunson TW, Maloney DG, Turtle CJ, et al. Factors affecting lymphocyte collection efficiency for the manufacture of chimeric antigen receptor T cells in adults with B-cell malignancies. Transfusion. 2019;59:1773–1780. doi: 10.1111/trf.15178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stock S, Schmitt M, Sellner L. Optimizing manufacturing protocols of chimeric antigen receptor T cells for improved anticancer immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:6263. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elavia N, Panch SR, McManus A, Bikkani T, Szymanski J, Highfill SL, et al. Effects of starting cellular material composition on chimeric antigen receptor T-cell expansion and characteristics. Transfusion. 2019;59:1755–1764. doi: 10.1111/trf.15287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Künkele A, Brown C, Beebe A, Mgebroff S, Johnson AJ, Taraseviciute A, et al. Manufacture of chimeric antigen receptor T cells from mobilized cyropreserved peripheral blood stem cell units depends on monocyte depletion. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das RK, Vernau L, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Naïve T-cell deficits at diagnosis and after chemotherapy impair cell therapy potential in pediatric cancers. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:492–499. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finney OC, Brakke HM, Rawlings-Rhea S, Hicks R, Doolittle D, Lopez M, et al. CD19 CAR T cell product and disease attributes predict leukemia remission durability. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2123–2132. doi: 10.1172/JCI125423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paroder M, Le N, Pham HP, Thibodeaux SR. Important aspects of T-cell collection by apheresis for manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Adv Cell Gen Therapy. 2020;3:e75. doi: 10.1002/acg2.75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.YESCARTA® (axicabtagene ciloleucel) treatment process [Internet] [Accessed on 04/12/2020]. Available from https://www.yescartahcp.com/follicular-lymphoma/treatment-process.

- 32.Yakoub-Agha I, Chabannon C, Bader P, Basak GW, Bonig H, Ciceri F, et al. Management of adults and children undergoing chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) Haematologica. 2020;105:297–316. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.229781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thibodeaux SR, Aqui NA, Park YA, Scheiderman J, Su LL, Winters JL, et al. Lack of defined apheresis collection criteria in publicly available CAR-T cell clinical trial descriptions: Comprehensive review of over 600 studies. J Clin Apher. 2022;37:223–236. doi: 10.1002/jca.21964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.I centri autorizzati alla somministrazione delle terapie CAR-T. Centers authorized to administer CAR-T therapies; [Accessed on 09/06/2022]. [Internet]. Available at: https://www.ail.it/hematologycenters. [Google Scholar]

- 35.AIFA Scheda Registro Kymriah DLBCL [Internet] [Accessed on 16/12/2020]. Available at: www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1728832/Scheda_Registro_Kymriah_DLBCL_07.07.2022.zip/50297019-90eb-eba1-4e66-249b97e90eec.

- 36.Attivazione web e pubblicazione schede di monitoraggio - Registro YESCARTA. [Internet] [Accessed on 09/02/2021]. Available at: www.aifa.gov.it/-/attivazione-web-e-pubblicazioneschede-di-monitoraggio-registro-yescarta.

- 37.Hiddemann W, Barbui AM, Canales MA, Cannell PK, Collins GP, Dürig J, et al. Immunochemotherapy with obinutuzumab or rituximab for previously untreated follicular lymphoma in the GALLIUM study: influence of chemotherapy on efficacy and safety. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2395–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.8960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez-Calle N, Hartley S, Ahearne M, Kasenda B, Beech A, Knight H, et al. Kinetics of T-cell subset reconstitution following treatment with bendamustine and rituximab for low-grade lymphoproliferative disease: a population-based analysis. Br J Haematol. 2019;184:957–968. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh N, Perazzelli J, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Early memory phenotypes drive T cell proliferation in patients with pediatric malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:320ra3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korell F, Laier S, Sauer S, Veelken K, Hennemann H, Schubert M-L, et al. Current challenges in providing good leukapheresis products for manufacturing of CAR-T cells for patients with relapsed/refractory NHL or ALL. Cells. 2020;9(5):1225. doi: 10.3390/cells9051225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayden PJ, Roddie C, Bader P, Basak GW, Bonig H, Bonini C, et al. Management of adults and children receiving CAR T-cell therapy: 2021 best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) and the European Haematology Association (EHA) Ann Oncol. 2022;33(3):259–275. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pratx LB, Gru I, Spotti M, Sánchez DD, Ninomiya M, Marcarián G, et al. Development of apheresis techniques and equipment designed for patients weighing less than 10 kg. Transfus Apher Sci. 2018;57:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Decreto del Ministero della Salute. [[Provisions relating to the quality and safety requirements of blood and blood components.]]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana 300; novembre 2 28, 2015. Dec 2 28, 2015. [In Italian.] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decreto Legislativo 25 gennaio 2010, n. 16 [Implementation of Directives 2006/17/EC and 2006/86/EC, which implement Directive 2004/23/EC as regards the technical requirements for the donation, procurement and testing of human tissues and cells, as well as concerns traceability requirements, notification of serious adverse reactions and events and certain technical requirements for coding, processing, preservation, storage and distribution of human tissues and cells]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n. 40, 18 Februaty 2010 [In Italian.]

- 45.Maus MV, Levine BL. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for the community oncologist. Oncologist. 2016;21:608–617. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierelli L, Perseghin P, Marchetti M, Accorsi P, Fanin R, Messina C, et al. Best practice for peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization and collection in adults and children: results of a Società Italiana Di Emaferesie Manipolazione Cellulare (SIDEM) and Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo (GITMO) consensus process. Transfusion. 20212;52(4):893–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, Singh Gill D, Linch DC, Trneny M, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4184–4190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ravagnani F, Siena S, De Reys S, Di Nicola M, Notti P, Giardini R, et al. Improved collection of mobilized CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells by a novel automated leukapheresis system. Transfusion. 1999;39:48–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39199116894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ceppi F, Rivers J, Annesley C, Pinto N, Park JR, Lindgren C, et al. Lymphocyte apheresis for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell manufacturing in children and young adults with leukemia and neuroblastoma. Transfusion. 2018;58:1414–1420. doi: 10.1111/trf.14569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoon EJ, Zhang J, Weinberg RS, Brochstein JA, Nandi V, Sachais BS, et al. Validation of simple prediction algorithms to consistently achieve CD3+ and postselection CD34+ targets with leukapheresis. Transfusion. 2020;60:133–143. doi: 10.1111/trf.15576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trickett AE, Smith S, Kwan YL. Accurate calculation of blood volume to be processed by apheresis to achieve target CD34+ cell numbers for PBPC transplantation. Cytotherapy. 2001;3:5–10. doi: 10.1080/146532401753156359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ljungman P, Mikulska M, de la Camara R, Basak GW, Chabannon C, et al. The challenge of COVID-19 and hematopoietic cell transplantation; EBMT recommendations for management of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, their donors, and patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:2071–2076. doi: 10.1038/s41409-020-0919-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarisch A, Rettinger E, Sörensen J, Klingebiel T, Schäfer R, Seifried E, et al. Unstimulated apheresis for chimeric antigen receptor manufacturing in pediatric/adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. J Clin Apher. 2020;35:398–405. doi: 10.1002/jca.21812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeSimone RA, Myers GD, Guest EM, Shi PA. Combined heparin/acid citrate dextrose solution A anticoagulation in the Optia continuous mononuclear cell protocol for pediatric lymphocyte apheresis. J Clin Apher. 2019;34:487–489. doi: 10.1002/jca.21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyagarajan S, Schmitt D, Acker C, Rutjens E. Autologous cryopreserved leukapheresis cellular material for chimeric antigen receptor-T cell manufacture. Cytotherapy. 2019;21:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyagarajan S, Spencer T, Smith J. Optimizing CAR-T cell manufacturing processes during pivotal clinical trials. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;16:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Panch SR, Srivastava SK, Elavia N, McManus A, Liu S, Jin P, et al. Effect of cryopreservation on autologous chimeric antigen receptor T cell characteristics. Mol Ther. 2019;27:1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rafiq S, Hackett CS, Brentjens RJ. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:147–167. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]