Abstract

Background

Health literacy (HL) is a determinant of health and important for autonomous decision‐making. Migrants are at high risk for limited HL. Improving HL is important for equitable promotion of migrants' health.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions for improving HL in migrants. To assess whether female or male migrants respond differently to the identified interventions.

Search methods

We ran electronic searches to 2 February 2022 in CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo and CINAHL. We also searched trial registries. We used a study filter for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (RCT classifier).

Selection criteria

We included RCTs and cluster‐RCTs addressing HL either as a concept or its components (access, understand, appraise, apply health information).

Data collection and analysis

We used the methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane and followed the PRISMA‐E guidelines. Outcome categories were: a) HL, b) quality of life (QoL), c) knowledge, d) health outcomes, e) health behaviour, f) self‐efficacy, g) health service use and h) adverse events. We conducted meta‐analysis where possible, and reported the remaining results as a narrative synthesis.

Main results

We included 28 RCTs and six cluster‐RCTs (8249 participants), all conducted in high‐income countries. Participants were migrants with a wide range of conditions. All interventions were adapted to culture, language and literacy.

We did not find evidence that HL interventions cause harm, but only two studies assessed adverse events (e.g. anxiety). Many studies reported results for short‐term assessments (less than six weeks after total programme completion), reported here. For several comparisons, there were also findings at later time points, which are presented in the review text.

Compared with no HL intervention (standard care/no intervention) or an unrelated HL intervention (similar intervention but different information topic)

Self‐management programmes (SMP) probably improve self‐efficacy slightly (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 0.50; 2 studies, 333 participants; moderate certainty). SMP may improve HIV‐related HL (understanding (mean difference (MD) 4.25, 95% CI 1.32 to 7.18); recognition of HIV terms (MD 3.32, 95% CI 1.28 to 5.36)) (1 study, 69 participants). SMP may slightly improve health behaviours (3 studies, 514 participants), but may have little or no effect on knowledge (2 studies, 321 participants) or subjective health status (MD 0.38, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.89; 1 study, 69 participants) (low certainty). We are uncertain of the effects of SMP on QoL, health service use or adverse events due to a lack of evidence. HL skills building courses (HLSBC) may improve knowledge (MD 10.87, 95% CI 5.69 to 16.06; 2 studies, 111 participants) and any generic HL (SMD 0.48, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.75; 2 studies, 229 participants), but may have little or no effect on depression literacy (MD 0.17, 95% CI ‐1.28 to 1.62) or any health behaviour (2 studies, 229 participants) (low certainty). We are uncertain if HLSBC improve QoL, health outcomes, health service use, self‐efficacy or adverse events, due to very low‐certainty or a lack of evidence. Audio‐/visual education without personal feedback (AVE) probably improves depression literacy (MD 8.62, 95% CI 7.51 to 9.73; 1 study, 202 participants) and health service use (MD ‐0.59, 95% CI ‐1.11 to ‐0.07; 1 study, 157 participants), but probably has little or no effect on health behaviour (risk ratio (RR) 1.07, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.25; 1 study, 135 participants) (moderate certainty). AVE may improve self‐efficacy (MD 3.51, 95% CI 2.53 to 4.49; 1 study, 133 participants) and may slightly improve knowledge (MD 8.44, 95% CI ‐2.56 to 19.44; 2 studies, 293 participants) and intention to seek depression treatment (MD 1.8, 95% CI 0.43 to 3.17), with little or no effect on depression (SMD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.10) (low certainty). No evidence was found for QoL and adverse events. Adapted medical instruction may improve understanding of health information (3 studies, 478 participants), with little or no effect on medication adherence (MD 0.5, 95% CI ‐0.1 to 1.1; 1 study, 200 participants) (low certainty). No evidence was found for QoL, health outcomes, knowledge, health service use, self‐efficacy or adverse events.

Compared with written information on the same topic

SMP probably improves health numeracy slightly (MD 0.7, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.25) and probably improves print literacy (MD 9, 95% CI 2.9 to 15.1; 1 study, 209 participants) and self‐efficacy (SMD 0.47, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.64; 4 studies, 552 participants) (moderate certainty). SMP may improve any disease‐specific HL (SMD 0.67, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.07; 4 studies, 955 participants), knowledge (MD 11.45, 95% CI 4.75 to 18.15; 6 studies, 1101 participants) and some health behaviours (4 studies, 797 participants), with little or no effect on health information appraisal (MD 1.15, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 2.53; 1 study, 329 participants) (low certainty). We are uncertain whether SMP improves QoL, health outcomes, health service use or adverse events, due to a lack of evidence or low/very low‐certainty evidence. AVE probably has little or no effect on diabetes HL (MD 2, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 4.15; 1 study, 240 participants), but probably improves information appraisal (MD ‐9.88, 95% CI ‐12.87 to ‐6.89) and application (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.77) (1 study, 608 participants; moderate certainty). AVE may slightly improve knowledge (MD 8.35, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 17.02; low certainty). No short‐term evidence was found for QoL, depression, health behaviour, self‐efficacy, health service use or adverse events.

AVE compared with another AVE

We are uncertain whether narrative videos are superior to factual knowledge videos as the evidence is of very low certainty.

Gender differences

Female migrants' diabetes HL may improve slightly more than that of males, when receiving AVE (MD 5.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 9.38; 1 study, 118 participants), but we do not know whether female or male migrants benefit differently from other interventions due to very low‐certainty or a lack of evidence.

Authors' conclusions

Adequately powered studies measuring long‐term effects (more than six months) of HL interventions in female and male migrants are needed, using well‐validated tools and representing various healthcare systems.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Male, Anxiety, Anxiety/therapy, Diabetes Mellitus, Health Literacy, HIV Infections, Quality of Life, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Transients and Migrants

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of health literacy interventions for migrants?

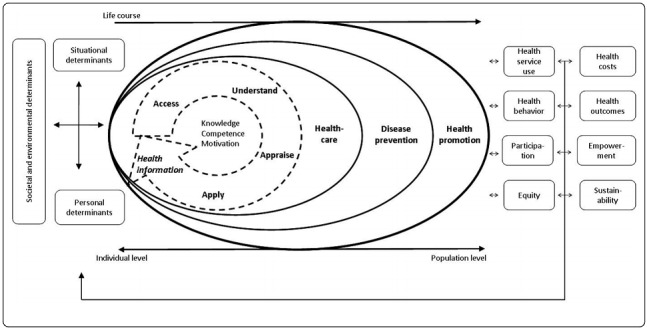

Health literacy (HL) means the knowledge, motivation and competencies (e.g. reading and writing abilities) that people need to find, understand, evaluate and use health information. Migrants are at risk for difficulties in HL (e.g. when they don't know the country's health system well).

'Generic' HL means that people can find, understand and use general health information to make health decisions. 'Disease‐specific' HL means that people can find, understand and use information about a certain disease or that they know about the symptoms of a disease or understand treatment options.

Key messages

We have moderate to low confidence in these findings that some HL interventions have small to moderate positive effects on migrants' HL. This means that these interventions can help people improve their knowledge, recognition and understanding of medical terms, or use of health information.

There is a need for larger, well‐designed studies that measure long‐term effects of HL interventions in migrant women and men.

What did we want to find out?

Our main goal was to find out whether HL interventions can help migrants to improve their HL. We also wanted to find out if migrant women or migrant men benefit more from these interventions.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at interventions for improving HL in migrants. These interventions were compared with 1) no HL intervention (e.g. standard care), 2) written information on the same health topic (e.g. brief brochure), 3) an unrelated HL intervention (participants received a similar intervention, but the information was on a different health topic), or 4) another HL intervention (participants received a different intervention, but the information was on the same health topic).

The included studies measured HL either as an overall concept or only components of it (e.g. understanding health information). We compared and summarised the results of studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors like study methods.

What did we find?

We found 34 studies that involved 8249 migrants with a wide range of health conditions. All studies were conducted in high‐income countries. All interventions were adapted to the participants' culture, language and literacy level. None of the studies reported that HL interventions cause harm, but only two studies reported possible harms (anxiety). Many studies reported short‐term results (up to six weeks after the intervention ended, the focus in this summary). There were also several findings at later time points (presented in the main review).

Compared with no or unrelated HL intervention:

Self‐management programmes (SMP)(long‐term programmes including group education and personal support) probably improve self‐efficacy in managing one's disease slightly (which means that the participants had higher beliefs in their abilities to act on health information). SMP may also improve disease‐specific HL and may slightly improve health behaviour, but may have little effect on knowledge or self‐rated health. We do not know if SMP improves quality of life (QoL) or health service use.

HL skills building courses(group education in which participants, for example, learn what to do to prevent a disease) may improve knowledge and generic HL, but they may have little effect on depression literacy or health behaviour. We do not know if they improve QoL, health outcomes, health service use or self‐efficacy.

Audio‐/visual education without personal feedback (AVE)(including video education, interactive computer education or printed educational photo stories)probably improves depression literacy and health service use. AVE may improve self‐efficacy and slightly improve knowledge and intention to seek depression treatment, but may have little effect on health behaviour or depression. No study reported on QoL.

Adapted medical instructions(medical instructions that use simple language, illustrations or pictures) may improve understanding health information, but may have little effect on medication adherence. No study reported on QoL, health outcomes, knowledge, health service use or self‐efficacy.

Compared with written information:

SMP probably improves print literacy and self‐efficacy, and health numeracy slightly. SMP may improve any disease‐specific HL, knowledge and some health behaviours, but may have little effect on health information appraisal. We do not know whether SMP improves QoL, health outcomes or health service use.

AVEprobably has little effect on diabetes HL but probably improves information appraisal and application. AVE may slightly improve knowledge. No study reported on QoL, depression, health behaviour, self‐efficacy or health service use.

AVE compared with another AVE:

We are uncertain if narrative videos are better than factual knowledge videos as the evidence was very uncertain.

Do migrant women or men benefit differently from HL interventions?

Migrant women's diabetes HL may improve slightly more than that of migrant men after receiving AVE. For other comparisons and outcomes we either did not find evidence, or we are uncertain about the results.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

It is possible that people in some studies knew which treatment they were getting. In addition, studies were done in different migrant groups, coming from different regions and with different health conditions, and some studies included few people.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

This review is up‐to‐date to 2 February 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus no health literacy intervention.

| Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus no health literacy intervention | ||||||

| Patient or population: migrants Setting: all settings Intervention: culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme (programme length: 6 to 12 months) Comparison: no health literacy intervention (usual care, placebo intervention or wait‐list control) | ||||||

| Outcome category – outcome(s)* | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no health literacy intervention | Risk with self‐management programme | |||||

|

Health literacy – Disease‐specific health literacy Assessed with:

Higher scores are better Time point: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention)** |

One RCT reported that the change from baseline score for understanding of HIV terms was 4.25 points higher (1.32 higher to 7.18 higher) and recognition of HIV terms was 3.32 points higher (1.28 higher to 5.36 higher) in the intervention group. | — | 69 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Self‐management programmes compared to no health literacy intervention may improve disease‐specific health literacy (HIV health literacy) immediately post‐intervention. | |

| Quality of life | — | — | — | — | The effect of self‐management programmes is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. | |

|

Health‐related knowledge – Multiple measures used: (1)Diabetes knowledge

(2) HIV knowledge

Time point: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) |

(1) Diabetes knowledge One RCT (N = 252) reported that the mean diabetes knowledge score was 5.6 points higher (range = 2.2 higher to 9.0 higher) in the intervention group. The mean knowledge score in the control group was 68; P = 0.001. (2) HIV knowledge One RCT (N = 69) reported that the mean HIV global disease/treatment knowledge was 1.18% lower (9.23 lower to 6.87 higher) in the intervention group, but the CI encompassed values indicating both an improvement and a reduction in knowledge. The same study reported that the mean knowledge of the risk of getting sicker when stopping taking one's HIV medication was higher in the intervention group: 0.33 higher (‐0.01 lower to 0.67 higher) but the CI also encompassed values indicating a null effect. |

— | 321 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | Self‐management programmes compared to no health literacy intervention may have little or no effect on health‐related knowledge immediately post‐intervention. One cluster RCT (n = 230) was missing information about participant numbers but reported that the intervention increased breast cancer‐related knowledge (MD 0.5, P < 0.0001) at 6 months post test (very low certainty)d,e One other RCT (N = 194) was missing data about the control group but reported that knowledge about heart health increased in the intervention group 3 months post‐intervention.4 |

|

|

Health outcome – Self‐reported health status Assessed with:

Higher score is better Time point: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) |

One RCT reported that the mean subjective health status in the past week was 0.38 points higher (0.13 lower to 0.89 higher) in the intervention group immediately post‐intervention, but the CI encompassed both an improvement and a reduction in subjective health status. | — | 69 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowf | Self‐management programmes compared to no health literacy intervention may have little or no effect on subjective health status immediately post‐intervention. | |

|

Health behaviour5– Time point a: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) Multiple outcomes assessed and multiple measures used: (1) Blood glucose self‐monitoring

(2) Adherence to HIV medication

(3) Physical activity Assessed with:

Higher scores are better |

Time point a: short‐term (1) Blood glucose self‐monitoring: One RCT (n = 252) reported higher odds of self‐reported blood glucose self‐monitoring in the intervention group immediately post‐intervention (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.52) (2) Adherence to HIV medication: One RCT (n = 69) reported that the proportion of participants who reported > 95% adherence to HIV medication within the last 4 days was higher in the intervention group immediately post‐intervention (IG change score: 1.71%, CG change score: ‐4.85%) (3) Physical activity: One RCT (n = 193) reported that the mean average daily steps was higher in the intervention group, but the CI encompassed both an improvement and a reduction in physical activity immediately post‐intervention (MD 289 daily steps higher, 95% CI 601.41 lower to 1179.41 higher) |

— | 514 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,h | Self‐management programmes compared to no health literacy interventions may slightly improve any health behaviour immediately post‐intervention, but outcome measures and effects appear variable. One cluster‐RCT was missing information about the number of participants randomised to each study group, as well as the intensity and length of the programme. In addition, data were not reported in a way in which they could be extracted for meta‐analysis. |

|

|

Self‐efficacy – Self‐efficacy to manage one's disease Multiple measures used:

Higher score is better Time point: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) |

— | The mean score in the intervention group was 0.28 standard deviations higher (0.06 higher to 0.50 higher) | — | 333 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateg | Self‐management programmes compared to no health literacy interventions probably improve self‐efficacy to manage one's disease slightly. |

| Health service use – not measured | — | — | — | — | — | The effect of self‐management programmes on health service use is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. |

| Adverse events – not reported | — | — | — | — | — | The effect of self‐management programmes on adverse events is unknown as there was no direct evidence identified. |

| *More detail on scoring and direction for each outcome measure is provided in Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; **Short‐term: immediately up to 6 weeks after the total intervention programme was completed; medium‐term: from 6 weeks up to and including 6 months after the total intervention programme was completed; long‐term: longer than 6 months after the total intervention programme was completed. ACTG: Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group; ADKnowl: Audit of Diabetes Knowledge; CG: control group; CI: confidence interval; IG: intervention group; LSESLD: Lifestyle Self‐Efficacy Scale for Latinos with Diabetes; MD: mean difference; n.r.: not reported; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; REALM: Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Results for understanding HIV terms and recognition of HIV terms were reported separately in the study, and only change scores were reported.

2The score range was taken from publications cited by the study authors (Rosal 2003; Speight 2001), as it was not reported in the published trial report (Rosal 2011).

3To improve the interpretation of results, we transformed the original scale, which had negative values indicating better performance, into a positive scale with higher values indicating better performance.

4GRADE was not used due to missing control group data.

5All outcomes except physical activity were assessed via self‐report.

aDowngraded by ‐2 for imprecision: result was based on a single study with a small sample size (less than 100) and wide CI.

bDowngraded by ‐1 for imprecision: narrative synthesis conducted and the CI of one study encompassed values indicating both an improvement and a worsening in the outcome. In addition, the sample size was small.

cDowngraded by ‐1 for inconsistency: CI of one study indicated a small improvement in the outcome. The other study reported two measures of knowledge; results of the first measure indicated a reduction in knowledge with a CI encompassing values suggesting both an improvement and a worsening. The second measure indicated an improvement in knowledge with a CI encompassing an improvement and a null effect (lower CI ‐0.01).

dDowngraded by ‐2 for risk of bias: unclear risk of bias in several domains including random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

eDowngraded by ‐1 for imprecision: missing information about the number of participants in the intervention and control groups; the length and intensity of the programme and effect measures were not reported per study group.

fDowngraded by ‐2 for imprecision: result was based on a single study with a small sample size (less than 100) and the CI encompassed values indicating both an improvement and a worsening.

gDowngraded by ‐1 for risk of bias: high risk of bias for blinding in 2 out of 3 studies, unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment in one study.

hDowngraded by ‐1 for inconsistency: Two studies indicated an improvement in health behaviour, but the CI of one study indicated a worsening or an improvement in physical activity.

1. Outcome category: (disease‐specific) health literacy.

| Study ID | Health topic | Measure | No. of participants | Time point(s) |

Intervention arm(s) Mean (SD)* |

Control arm(s) Mean (SD) |

Notes |

| 1 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| van Servellen 2005 | HIV | HIV health literacy Print literacy (recognition of HIV terms): modified REALM, 0 to 24, higher score is better Functional health literacy (understanding HIV terms): participants had to explain HIV‐relevant terms, 0 to 24, higher score is better |

IG: 34 CG: 35 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 4.66 (4.80) (recognition) |

1.34 (3.76) (recognition) |

Change scores are reported Intervention group: P < 0.001 (both time points) |

| 6.16 (7.97) (understanding) |

1.91 (3.60) (understanding) |

||||||

| 2 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Han 2017 | Breast/cervical cancer | Cancer screening health literacy AHL‐C, 52 items, 0 to 52, higher score is better |

IG: 278 CG: 282 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 32.1 (12.7) | 27.2 (13.0) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analysis using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017 (see Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4; Analysis 2.6) |

| Kaur 2019 | Oral health | Oral health literacy TS‐REALD, 27 to 73, higher score is better |

IG: 70 CG: 70 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 6.51 (3.85) | 1.41 (3.69) | Change scores, calculated from reported linear mixed model analysis. MD 5.10 (95% CI 3.85 to 6.34) Group x time P < 0.0001 |

| Kim 2014 | High blood pressure | HBP health literacy HBP health literacy scale, 0 to 43, higher score is better |

IG: 184 CG: 185 |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 28.2 (12.1) | 24.9 (13.7) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analysis using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017 (see Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4; Analysis 2.6) |

| 18 months after randomisation (6‐month follow‐up) | 29.4 (11.4) | 25.3 (13.4) | |||||

| Kim 2020 | Type 2 diabetes | Print literacy REALM, 0 to 66, higher score is better |

IG: 105 CG: 104 |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 40.5 (SE 2.2) | 31.5 (SE 2.2) | P < 0.01 (all time points) |

| Diabetes‐specific print literacy DM‐REALM, 0 to 82, higher score is better |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 62.9 (SE 2.1) | 50.8 (SE 2.7) | P < 0.001 (all time points) | |||

| Functional health literacy TOFHLA, 0 to 7, higher score is better |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 4.9 (SE 0.2) | 4.4 (SE 0.3) | No difference | |||

| Health numeracy NVS, 0 to 6, higher score is better |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 3.1 (SE 0.2) | 2.4 (SE 0.2) | P < 0.05 | |||

| 3 Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course vs no/unrelated health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Otilingam 2015 | Nutrition/heart and brain health | Health numeracy NVS, 0 to 6, higher score is better |

IG 1: 29 IG 2: 29 CG 1: 16 CG 2: 18 |

Immediately post‐intervention | IG 1: 2.59 (1.92) IG 2: 2.34 (1.99) |

CG: 1.00 (1.63) CG 2: 1.61 (1.79) |

Both IG and both CG were combined for meta‐analysis (see Analysis 3.1). CG 2 was assessed immediately post‐intervention only. Group x time P = 0.0103 |

| At 1‐month follow‐up | IG 1: 2.59 (1.76) IG 2: 2.55 (1.70) Combined: 2.57 (1.72) |

CG 1: 1.38 (1.54) | |||||

| Soto Mas 2018 | Cardiovascular health | Functional health literacy TOFHLA, 0 to 100, higher score is better |

IG: 77 CG: 78 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 72.8 Mean change post‐pre (95% CI): 12.9 (10.4 to 15.3) |

73.7 Mean change post‐pre (95% CI): 8.2 (5.5 to 10.9) |

P = 0.012 |

| 6 weeks after first session | — | — | |||||

| Wong 2020 | Mental health (depression) | Depression literacy D‐Lit, 0 to 22, higher score is better |

IG: 18 CG: 19 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 13.06 (2.10) | 12.89 (2.40) | P = 0.36 |

| At 2‐month follow‐up | 13.38 (2.12) (combined sample) |

— | |||||

| 5 Culturally and literacy adapted media education without personal feedback vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Kiropoulos 2011 | Mental health (depression) | Depression literacy D‐Lit, 0 to 22, higher score is better |

IG: 110 CG: 92 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 17.43 (3.99) | 8.03 (4.33) | P < 0.001 |

| At 1‐week follow‐up | 16.84 (3.58) | 8.22 (4.33) | Pre‐intervention measure of the variable as a covariate P < 0.001 Post‐intervention measure of the variable as a covariate P < 0.01 |

||||

| 6 Culturally and literacy adapted media intervention without personal feedback vs literacy adapted written information | |||||||

| Calderón 2014 | Type 2 diabetes | Diabetes literacy DHLS, 37 items on type 2 diabetes knowledge (21 items) and knowledge application and cultural perceptions about diabetes management (16 items) |

IG: 118 CG: 122 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 0.55 (0.08) | 0.53 (0.09) | Unadjusted values were obtained from study authors |

* Unadjusted mean (SD) if not otherwise reported.

AHL‐C: Assessment of Health Literacy in Cancer Screening; CG: control group; CI: confidence interval; DHLS: Diabetes Health Literacy Survey; D‐Lit: Depression Literacy Questionnaire; DM‐REALM: Diabetes Mellitus‐Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; HBP: high blood pressure; IG: intervention group; MD: mean difference; NVS: newest vital sign; RCT: randomised controlled trial; REALM: Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error; TOFHLA: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults; TS‐REALD: Two Stage Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Dentistry

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 3: Any disease‐specific health literacy (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention) ‐ all studies

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 4: Any disease‐specific health literacy (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention ‐ by subgroup length of programme)

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 6: Any disease‐specific health literacy (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention) ‐ without Kaur 2019

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course versus no/unrelated health literacy intervention, Outcome 1: Any generic health literacy (short‐term: up to 1 month post‐intervention)

2. Outcome category: health‐related knowledge.

| Study ID | Health topic | Measure | No. of participants | Time point(s) |

Intervention arm(s) Mean (SD)* |

Control arm(s) Mean (SD)* |

Notes |

| 1 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Bloom 2014 | Breast health/breast cancer | Not reported | N: 230 | 6 months post‐intervention | — | — | MD 0.5 (P < 0.0001) Cluster‐RCT; "GEE were used to account for clustering (sample and analysis)" (Bloom 2014) Increased knowledge did not increase mammography |

| Koniak‐Griffin 2015 | Cardiovascular disease | Heart knowledge questionnaire, adapted from a previous survey by Mosca et al (2004) (10 items, true/false format, 0 to 10, higher score is better) |

IG: 98 CG: 95 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) |

7.9 (2.6) | Not reported | — |

| IG: 100 CG: 94 |

9 months after randomisation (at 3‐month follow‐up) |

9.4 (1.9) | |||||

| Rosal 2011 | Type 2 diabetes | ADKnowl, adapted version (23 item‐sets (104 items), 0 to 104, higher score is better) |

IG: 124 CG: 128 |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 0.089 (range ‐0.065 to 0.113) | 0.033 (range 0.009 to 0.057) | Intervention effect 0.056 (0.022 to 0.090) P = 0.001 |

| van Servellen 2005 | HIV | (1) HIV Illness and Treatment Knowledge and Misconceptions Scale (17 items, 0 to 17, higher score is better) (2) Knowledge of risk of getting sicker 1 item, 1 = very high risk to 4 = nonexistent risk, lower score is better |

IG: 34 CG: 35 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | (1) 1.20 (3.19) (2) ‐0.24 (0.78) |

(1) 1.40 (2.59) (2) 0.09 (0.67) |

Change scores are reported To improve the interpretation of results, the original scale has been transformed into a positive scale with higher values indicating better performance (see Analysis 1.4) |

| 2 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Han 2017 | Cervical/breast cancer | Breast Cancer Knowledge Test (0 to 18, higher score is better) |

IG: 278 CG: 282 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 11.0 (3.9) | 10.4 (3.8) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analyses using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017. In addition, combined scores for breast cancer knowledge and cervical cancer knowledge were calculated (see Analysis 2.10; Analysis 2.11). Estimated MD 0.7 (95% CI ‐0.1 to 1.6) MD estimated from linear mixed‐effects models adjusted for baseline knowledge, age, insurance, English proficiency, years of US residence, years of education, employment and family history of breast cancer. |

| Cervical Cancer Knowledge Test (0 to 20, higher score is better) |

5.6 (2.4) | 5.3 (2.6) | Estimated MD –0.1 (95% CI –0.3 to 0.1) | ||||

| Kaur 2019 | Oral health | Questionnaire on oral self‐care knowledge and oral self‐care behaviour (0 to 15, higher score is better) |

IG: 70 CG: 70 |

3 months after randomisation | 4.389 (2.15) | 0.82 (2.013) (95% CI 0.34 to 1.31) | MD 3.57 (2.88 to 4.26) Group x time P < 0.0001 Mean (SD) was calculated from reported linear mixed model analysis |

| Kim 2009 | Type 2 diabetes | DKT (14 items, 0 to 14 (general test, knowledge I), 9 items insulin subscale (knowledge II)1, higher score is better) |

IG: 40 CG: 39 |

30 weeks after randomisation | Knowledge (I) 2.4 (2.3) Knowledge (II) 0.3 (3.7)1 |

Knowledge (I) 0.7 (2.4) Knowledge (II) 0.4 (0.8)1 |

Change scores are reported Knowledge (I) P = 0.00 Knowledge (II) P = 0.27 |

| Kim 2014 | High blood pressure | HBP knowledge questionnaire (0 to 26, higher score is better) |

IG: 184 CG: 185 |

12 months after randomisation | 20.8 (2.7) | 19.3 (3.7) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analysis using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017. Group x time P = 0.001 (see Analysis 2.10; Analysis 2.11; Analysis 2.14; Analysis 2.13) |

| 18 months after randomisation (6‐month follow‐up) | 20.8 (2.8) | 20.1 (3.2) | |||||

| Kim 2020 | Type 2 diabetes | DKT (14 items, 0 to 14 (general test), 9 items insulin subscale (results not reported), higher score is better) |

IG: 105 CG: 104 |

12 months after randomisation | 10.3 (SE 0.2) | 8.3 (SE 0.3) | Group P < 0.001 |

| Rosal 2005 | Type 2 diabetes | ADKnowl, adapted version (23 item‐sets (104 items), 0 to 104), higher score is better |

IG: 15 CG: 10 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 0.05 (0.15) | ‐0.02 (0.11) | Change scores are reported Group x time P = 0.27 |

| 6 months after randomisation (4.5 months post‐intervention) | 0.05 (0.13) | ‐0.03 (0.08) | |||||

| 3 Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course vs no/unrelated health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Elder 1998 | Nutrition/cardiovascular health | Nutrition knowledge test (0 to 12, higher score is better) |

IG: 134 CG: 157 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 6.76 | 6.04 | Cluster‐RCT; unadjusted values are reported Group x time P ≤ 0.001 |

| At 6‐month follow‐up | 6.90 | 6.11 | |||||

| Otilingam 2015 | Nutrition/heart and brain health | US Department of Agriculture's Diet and Health Knowledge Survey (0 to 9, higher score is better) |

IG 1: 32 IG 2: 33 CG 1: 16 CG 2: 18 |

Immediately post‐intervention | IG 1: 6.86 (1.27) IG 2: 7.03 (0.91) Combined: 6.95 (1.10) |

CG 1: 5.94 (1.12) CG 2: 6.22 (0.94) Combined: 6.09 (1.02) |

Group x time P = 0.0293 (combined IGs vs CG 1) Both IGs and CGs were combined for meta‐analyses (see Analysis 3.3) CG 2 was assessed post‐test only |

| IG 1: 29 IG 2: 29 CG 1: 16 CG 2: 18 |

At 1‐month follow‐up | IG 1: 6.72 (1.33) IG 2: 6.66 (1.11) IG 1, 2*: 6.69 (1.21) |

CG 1: 5.56 (1.71) | ||||

| Taylor 2011 | Hepatitis B prevention, no specific health problem of participants reported | Questionnaire (0 to 5, higher score is better) |

IG: 80 CG: 100 |

At 6‐month follow‐up | 3.68 (1.12) | 2.87 (1.38) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analysis using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017. |

| Immigrants are more likely

to be infected with HBV

AOR 2.12 (1.12 to 4.03) HBV can be spread during childbirth AOR 2.10 (0.96 to 4.62) HBV can be spread during sexual intercourse AOR 2.58 (1.29 to 5.15) HBV can be spread by sharing razors AOR 5.42 (1.91 to 15.39) HBV infection can cause liver cancer AOR 2.08 (1.08 to 4.02 |

AOR estimated through GEE models were used to account for clustering; adjusted for ESL organisation, class time, country of origin, years since immigration, gender, age group, years of education and marital status | ||||||

| Tong 2017 | Colorectal cancer | Questionnaire (0 to 5, higher score is better) |

IG: 161 CG: 168 |

6 months after first session (at 3‐month follow‐up) | Knowledge of colon polyps: 23.6% to 78.3%, MD 54.7% Screening start age at 50 years: 14.3% to 36.0%, MD 21.7% FOBT yearly: 10.6% to 38.5%, MD 27.9% Sigmoidoscopy every 5 years: 3.7% to 24.2%, MD 20.5% Colonoscopy every 10 years: 2.5% to 20.5%, MD 18% |

Knowledge of colon polyps: 19.6% to 37.5%, MD 17.9% Screening start age at 50 years: 11.9% to 14.3%, MD 2.4% FOBT yearly: 11.9% to 17.3%, 5.4% Sigmoidoscopy every 5 years: 1.2% to 4.2%, MD 3% Colonoscopy every 10 years: 3.6% to 6.5%, MD 2.9% |

MD 36.8%, P < 0.0001 MD 19.3%, P = 0.0056 MD 22.5%, P = 0.0001 MD 17.5%, P < 0.0001 MD 15.1%, P = 0.012 Cluster‐RCT. No composite score reported. Authors state that GEE models were used to account for clustering. "For every point increase on the knowledge score (0‐5), the odds of ever‐screening and being up to date with screening were significantly increased, supporting knowledge as a mediator of the intervention effect." (Tong 2017 |

| Wong 2020 | Mental health (depression) | CBT‐Q (0 to 9, higher score is better) |

IG: 18 CG: 19 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 5.06 (0.10) | 4.33 (1.24) | P = 0.07 |

| At 2‐month follow‐up | — | ||||||

| 4 Culturally and literacy adapted telephone education vs unrelated culturally and literacy adapted telephone education | |||||||

| Lepore 2012 | Prostate cancer screening | Questionnaire (0 to 14, higher score is better) |

IG: 215 CG: 216 |

Approx. 7 months post‐intervention | 61.6 (SE 0.009) | 54.7 (SE 0.009) | P < 0.001 Adjusted for education, any PSA claim prior to pretest, and percent correct on knowledge index at pretest |

| 5 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| DeCamp 2020 | Child health | Questionnaire (0 to 5, higher score is better) |

IG: 72 CG: 63 |

10 to 13 months after randomisation (immediately to 3 months post‐intervention) | 0.67 (0.15) | 0.52 (0.15) | Change scores are reported P = 0.52 |

| Hernandez 2013 | Depression | Depression Knowledge Scale (0 to 17, higher score is better) | IG: 72 CG: 64 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 2.44 (2.24) | 0.02 (1.79) | Change scores are reported |

| Thompson 2012 | Child nutrition and feeding | Questionnaire (0 to 19, higher score is better) |

IG: 80 CG: 78 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 17.25 (1.7) | 13.7 (2.1) | P < 0.001 |

| 90.8 (9) | 72.3 (11.2) | ||||||

| 6 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Gwede 2019 | Colorectal cancer | Awareness of colorectal cancer and screening tests (Questionnaire based on NCI’s Health Information National Trends Survey and on literature, 0 to 11, higher score is better) |

IG: 32 CG: 27 |

At 3‐month follow‐up | 7.9 (2.0) | 6.4 (2.2) | — |

| Payán 2020 | Breast cancer | Questionnaire (0 to 16, higher score is better) |

IG 1: 79 (Cuidarse brochure) IG 2: 79 (Cuidarse brochure, CHW delivered) CG: 82 (standard brochure) |

Immediately post‐intervention | IG 1: 11.7 (2.7) IG 2: 11.5 (2.6) IG 1, 2: 11.6 (2.64) |

CG: 11.5 (3.0) | 10 to 13 months after randomisation; and IGs were combined for meta‐analysis (see, Analysis 6.6; Analysis 6.7; Analysis 6.8; Analysis 6.9) |

| IG 1: 67 IG 2: 61 CG: 65 |

At 3‐month follow‐up | IG 1: 10.3 (3.1) IG 2: 10.2 (2.8) IG 1, 2: 10.25 (2.95) |

CG: 10.7 (2.7) | ||||

| Poureslami 2016a | Asthma | Functional knowledge of asthma symptoms, triggers and factors that could make asthma worse (5‐point Likert scale, range not reported, higher score is better) |

Group 1: 22 Group 2: 21 Group 3: 20 Group 4: 22 |

At 3‐month follow‐up | Knowledge of asthma symptoms Group 1: ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.78 to 0.40 Group 2: 0.33, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.97 Group 3: 0.88, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 1.79 Knowledge of asthma triggers Group 1: 0.50, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 1.62 Group 2: 1.29, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 2.54) Group 3: 0.29, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 1.58 Knowledge of triggers that could make asthma worse Group 1: ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐2.37 to 2.01 Group 2: 0.86, 95% CI ‐0.51 to 2.22 Group 3: 0.35, 95% CI ‐1.12 to 1.94 |

Knowledge of asthma symptoms Group 4: 0.17, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 0.95 Knowledge of asthma triggers Group 4: 1.22, 95% CI 0.38 to 2.07 Knowledge of triggers that could make asthma worse Group 4: 0.45, 95% CI ‐1.41 to 2.31 |

6‐month assessment not reported No composite score reported, data were not combined as no score range was reported; the scale could not be standardised on a scale ranging from 0 to 100 Results reported are adjusted for age, gender, educational level and ethnicity Data have been extracted from the secondary reference (see Poureslami 2016a for all trial reports related to this study) |

| Poureslami 2016b | COPD | "Some" questions of BCKQ | — | ||||

| Unger 2013 | Depression | Depression Knowledge Scale (0 to 17, higher score is better) | IG: 69 CG: 70 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 2.37 (SE 0.32) | 0.86 (SE=0.27) | |

| 1‐month follow‐up | t = 5.09, P < 0.05 | t = 2.64, P < 0.05 | "[T]he data collectors reported that several students shared their photonovel with students in the text pamphlet group after the posttest." (Unger 2013, p. 405) | ||||

| Valdez 2015 | Cervical cancer | Questionnaire (0 to 12, higher score is better) |

IG: 290 CG: 318 |

At 1‐month follow‐up | 8.9 (1.6) | 7.1 (2.0) | P < 0.0001 |

| Valdez 2018 | Cervical Cancer | Questionnaire (0 to 5, higher score is better) |

IG: 383 CG: 344 |

At 6‐month follow‐up | 3.7 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.4) | P < 0.0001 |

| 7 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs another culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback | |||||||

| Ochoa 2020 | Cervical cancer | Questionnaire (0 to 8, higher score is better) |

IG: 61 CG: 48 |

At 2‐week follow‐up | 5.10 (1.45) | 4.44 (1.15) | P = 0.011 |

| At 6‐month follow‐up | 5.38 (1.27) | 5.29 (1.17) | P = 0.718 | ||||

| Poureslami 2016a | Asthma | Functional knowledge of asthma symptoms, triggers, and factors that could make asthma worse (5‐point Likert scale, range not reported, higher score is better) |

Group 1 (physician‐led knowledge video): 22 Group 2 (narrative, peer‐led video): 21 |

At 3‐month follow‐up | Knowledge of asthma symptoms Group 1: ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.78 to 0.40 Knowledge of asthma triggers Group 1: 0.50, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 1.62 Knowledge of triggers that could make asthma worse Group 1: ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐2.37 to 2.01 |

Knowledge of asthma symptoms Group 2: 0.33, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.97 Knowledge of asthma triggers Group 2: 1.29, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 2.54) Knowledge of triggers that could make asthma worse Group 2: 0.86, 95% CI ‐0.51 to 2.22 |

6‐month assessment not reported No composite score reported Results are adjusted for age, gender, educational level and ethnicity |

| Poureslami 2016b | COPD | "Some" questions from BCKQ | A 3‐month follow‐up | — | |||

*Unadjusted mean (SD) if not otherwise reported.

1 Assessed only for those injecting insulin (intervention, n = 5; control, n = 7). Data were not included in the meta‐analyses.

ADKnowl: Audit of Diabetes Knowledge; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; BCKQ: Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CBT‐Q: Knowledge of CBT questionnaire; CG: control group; CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DKT: Diabetes Knowledge Test; ESL: English as a second language; GEE: generalised estimating equations; HBP: high blood pressure; HBV: hepatitis B virus; IG: intervention group; NCI: National Cancer Institute; OR: odds ratio; PSA: prostate‐specific antigen; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus no HL intervention, Outcome 4: Health‐related knowledge: HIV knowledge, risk of getting sicker (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention)

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 10: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention) ‐ all studies

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 11: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention) ‐ by subgroup length of programme

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 14: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (medium‐term: up to 6 months post‐intervention)

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 13: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention) ‐ without Kaur 2019

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course versus no/unrelated health literacy intervention, Outcome 3: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (short‐term: up to 1 month post‐intervention) ‐ all studies

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback versus written information on the same topic, Outcome 6: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (short‐term: up to 1 month post‐intervention) ‐ all studies

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback versus written information on the same topic, Outcome 7: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (short‐term: up to 1 month post‐intervention) ‐ by subgroup audiovisual (multimedia)/visual (print only)

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback versus written information on the same topic, Outcome 8: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (medium‐term: 3 to 6 months post‐intervention) ‐ all studies

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback versus written information on the same topic, Outcome 9: Any health‐related knowledge, 0 to 100 (medium‐term: 3 to 6 months post‐intervention) ‐ by subgroup audiovisual (multimedia)/visual (print only)

3. Outcome category: health outcomes.

| Study ID | Health topic | Measure | No. of participants | Time point(s) |

Intervention arm Mean (SD)* |

Control arm Mean (SD)* |

Notes |

| 1 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| van Servellen 2005 | HIV | Self‐reported health status (1 item assessing general health status in the past week) |

IG: 34 CG: 35 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 0.47 (1.21) | 0.09 (0.95) | Change scores are reported No differences between study groups |

| 2 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Kim 2009 | Depression | KDSKA (21 items with 4 subscales, 0 to 75, lower score is better) |

IG: 40 CG: 39 |

30 weeks after randomisation | ‐0.5 (4.5) | ‐1.0 (4.3) | P = 0.70 |

| Kim 2014 | Depression | PHQ‐9 (9 items, 0 to 27, lower score is better) |

IG: 184 CG: 185 |

12 months after randomisation | 2.1 (2.9) | 3.0 (3.0) | Group x time P = 0.04 |

| 18 months after randomisation (at 6‐month follow‐up) | 2.5 (3.3) | 2.9 (3.3) | |||||

| Kim 2020 | Depression | PHQ‐9K (9 items, 0 to 27, lower score is better) |

IG: 105 CG: 104 |

12 months after randomisation | 4.8 (SE 0.5) | 4.1 (SE 0.4) | — |

| Rosal 2005 | Depression | CES‐D (20 items, 0 to 60, lower score is better) |

IG: 15 CG: 10 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | ‐3.7 (7.6) | 7.6 (8.9) | Change scores are reported Group x time P = 0.03 |

| 6 months after randomisation (4.5 months post‐intervention) | 1.4 (9.8) | 9.57 (11.0) | |||||

| 5 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| DeCamp 2020 | (Parent) depression | PHQ‐8 (8 items, 0 to 24, lower score is better) |

IG: 72 CG: 63 |

Immediately to 3 months post‐intervention (10 to 13 months after randomisation) | 0.68 (3.82) | 0.70 (4.18) | P = 0.97 |

| Kiropoulos 2011 | Depression | BDI‐II (0 to 63, lower score is better) |

IG: 110 CG: 92 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 7.26 (7.64) | 8.13 (7.53) | P = 0.87 |

| 1 week post‐intervention | 6.36 (6.60) | 8.26 (7.88) | P = 0.181 P = 0.192 |

||||

| 6 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Sudore 2018 | Depression | PHQ‐8 (0 to 24) referred to as adverse events, lower score is better |

IG: 219 CG: 226 |

At 12‐month follow‐up | 3.9 (95% CI 3.3 to 4.4) | 4.5 (95% CI 4.0 to 5.1) | P = 0.10 Adjusted for baseline depression and anxiety scores |

*Unadjusted mean (SD) if not otherwise reported.

1ANCOVA employed the pre‐intervention measure of the variable as a covariate.

2ANCOVA employed the postintervention measure of the variable as a covariate.

BDI‐II: Beck Depression Inventory‐II; CES‐D: Center for Epidemiological Studies‐Depression Scale; CG: control group; IG: intervention group; KDSKA: Kim Depression Scale for Korean Americans; PHQ‐8: Patient Health Questionnaire‐8; PHQ‐9: Patient Health Questionnaire‐9; PHQ‐9K: Korean version of PHQ‐9; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error

4. Outcome category: health behaviour.

| Study ID | Health topic | Measure | No. of participants | Time point(s) |

Intervention arm Mean (SD)* |

Control arm Mean (SD) |

Notes |

| 1 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Bloom 2014 | Breast health/breast cancer | Self‐report, mammography | N: 230 | 6 months after randomisation (no further details) | 56% | 10% | P < 0.0001 Cluster‐RCT; authors state that general linear models with GEE used to account for clustering (sample and analysis) |

| Koniak‐Griffin 2015 | Cardiovascular health | Physical activity; Lenz Lifecorder Plus Accelerometer, assesses vertical acceleration and counts movements that are correlated with steady‐state oxygen consumption | IG: 98 CG: 95 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 8769 (2747) | 8480 (3506) | Number of average daily steps is reported "[T]here was a statistically significant decrease in the control group, approaching a 1000‐step decline, whereas intervention participants maintained their activity level." (Koniak‐Griffin 2015, p.82 f) |

| IG: 100 CG: 94 |

9 months after randomisation (at 3‐month follow‐up) | 8577 (2872) | 7241 (2764) | ||||

| Rosal 2011 | Diabetes type 2 | Self‐monitoring of blood glucose 3 recalls per time point (oral assessment), 3 questions on physical activity and 3 questions on self‐monitoring of blood glucose, higher score is better |

IG: 124 CG: 128 |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 102/124; 81.5% | 81/128; 63.6% | P = 0.023 Values reflect blood glucose self‐monitoring 2 or more times per day; absolute numbers were calculated from reported percentages |

| van Servellen 2005 | HIV | HIV medication adherence, adherence behaviours baseline questionnaire (Proportion of > 95% adherence within last 4 days) |

IG: 34 CG: 35 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 1.71% | ‐4.85% | Change scores are reported |

| 2 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Han 2017 | Breast cancer | Adherence to mammogram, pap test, or both tests (Medical record review) |

Mammograma IG: 198 CG: 201 |

6 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | n: 111 (56.1%)b | n: 20 (10.0%)b | Cluster‐RCT AOR (95% CI)b (1) 18.5 (9.2 to 37.4) (2) 13.3 (7.9 to 22.3) (3) 17.4 (7.5 to 40.3) aWomen who were missing screening status were assumed to have not undergone screening bEstimated from GEE model accounting for clustering, adjusted for age, insurance, English proficiency, years in US, years of education, employment and family history of breast cancer |

| Pap testa IG: 246 CG: 251 |

Immediately post‐intervention | n: 134 (54.5%)b | n: 23 (9.2%)b | ||||

| Both testsa IG: 166 CG: 170 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 77/166 (46.4%)b | 11/170 (6.5%)b | ||||

| Kaur 2019 | Oral hygiene | Questionnaire on oral self‐care behaviour (higher score is better) |

IG: 70 CG: 70 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 3.10 (95% CI 2.50 to 3.69) | Group x time P < 0.0001 |

|

| Kim 2009 | Diabetes type 2 | Diabetes self‐care activities, SDSCA (higher score is better) |

IG: 40 CG:39 |

30 weeks after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 17.5 (16.9) | 2.5 (15.4) | Change scores are reported P = 0.00 |

| Kim 2014 | High blood pressure | Non‐adherence to blood pressure medication, HB‐MAS (8 items, 4‐point Likert‐scale, 1 = none of the time to 4 = all of the time, 8 to 32, lower score is better) |

IG: 184 CG: 185 |

12 months after randomisation | 9.1 (1.7) | 9.5 (2.0) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analyses using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017 |

| 18 months after randomisation (at 6‐month follow‐up) | 8.8 (1.4) | 9.2 (1.6) | |||||

| Rosal 2005 | Diabetes type 2 | Blood glucose self‐monitoring; 24‐hour recall of self‐monitoring of blood glucose by asking individuals whether they had checked their blood sugar level in the previous 24 hours, at what time, and the value, higher score is better | IG: 15 CG: 8 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | No./day capped at 2; 2/day both calls 0.63 (0.26); 12/15 (80%) |

No./day capped at 2; 2/day both calls 0.19 (0.35); 4/8 (50%) |

No difference |

| 6 months after randomisation (4.5 months post‐intervention) | No./day capped at 2; 2/day both calls 0.63 (0.24); 11/15 (74%) |

No./day capped at 2; 2/day both calls 0.06 (0.27); 3/8 (38%) |

|||||

| 3 Culturally adapted health literacy skill building course vs no/unrelated health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Otilingam 2015 | Behaviours to reduce dietary fat | Fat‐Related Diet Habits Questionnaire (12 items, 4‐point Likert scale, rarely/never, sometimes, often, usually, 1 to 4, higher score is better) |

IG 1: 32 IG 2: 33 CG 1: 16 CG 2: 18 |

Immediately post‐intervention | IG 1: 3.18 (0.46) IG 2: 3.25 (0.27) |

CG 1: 3.16 (0.39) CG 2: 3.12 (0.50) |

IGs were combined to create a single score (see Analysis 3.5). CG 2 was assessed immediately post‐intervention only. Group x time P = 0.0140 |

| At 1‐month follow‐up | IG 1: 3.43 (0.40) IG 2: 3.38 (0.30) Combined: 3.41 (0.35) |

CG 1: 3.16 (0.47) | |||||

| Taylor 2011 | Hepatitis B | Medical record of HBV testing | IG: 80 CG: 100 |

At 6‐month follow‐up | 5/80 (6.25%) | 0/100 (0%) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analyses using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017 (see Analysis 3.6) |

| Tong 2017 | Colorectal cancer | Up‐to‐date colorectal cancer screening* FOBT, S/C; self‐report of test receipt and when the test was obtained | IG: 161 CG: 168 |

6 months after first intervention session | 92/161 (57.1%) | 73/168 (43.5%) | Cluster‐RCT. Unadjusted values are reported. |

| Soto Mas 2018 | Cardiovascular health |

Cardiovascular health behaviour; CSC (34 items, 4‐point Likert scale, 1 = never to 4 = always, 34 to 136, higher score is better) |

IG: 77 CG: 78 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 59.1 | 57.9 | P = 0.067 |

| 4 Culturally and literacy adapted telephone education vs unrelated culturally and literacy adapted telephone education | |||||||

| Lepore 2012 | Prostate cancer | Prostate cancer screening behaviour; verified PSA test (Medical claims scanned for PSA procedure codes using an expert system, 0 = no, 1 = yes) |

IG: 244 CG: 246 |

1‐year follow‐up 2‐year follow‐up |

110/244 (45.1%) 153/244 (62.7%) |

113/246 (45.9%) 165/246 (66.7%) |

Absolute numbers were calculated from reported percentages |

| 5 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| DeCamp 2020 | Child's health | Prostate cancer screening behaviour; electronic medical record | IG: 72 CG: 63 |

3 months post‐intervention (15 months after child's birth) | n: 61 (85%) | n: 50 (79%) | No difference Percentages‐only are reported |

| 6 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Gwede 2019 | Colorectal cancer | Colorectal cancer screening uptake; Return of completed FIT kit within 90 days of intervention delivery, yes/no | IG: 40 CG: 36 |

3 months post‐intervention | n: 36 (90%) | n: 30 (83%) | P = 0.379 Percentages‐only are reported |

| Sudore 2018 | Advance care planning, no specific | Documentation of new advance care planning (Legal forms and documented discussions with clinicians and/or surrogates) |

IG: 219 CG: 226 |

At 12‐month follow‐up | 84/219 | 58/226 | — |

| Valdez 2018 | Cervical cancer | Pap test screening behaviour (Self‐report, having had a Pap test or made an appointment in the interval between pre‐test and post‐test, yes/no) |

IG: 383 CG: 344 |

At 6‐month follow‐up | n: 195 (51%) | n: 165 (48%) | Absolute numbers were calculated from reported percentages |

| 7 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs another culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback | |||||||

| Ochoa 2020 | Cervical cancer | Pap testing behaviour (1 item, "Since you saw the film, have you had a Pap test?", yes/no/do not know) |

IG: 61 CG: 48 |

At 6‐month follow‐up | n: 23 (37.9%) | n: 14 (29.2%) | Absolute numbers were calculated from reported percentages Results of the 2‐week post‐intervention assessment are not reported |

| 8 Culturally and literacy adapted medical instruction vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Mohan 2014 | No specific | Medication adherence; ARMS, patients' self‐reported adherence under various circumstances (sub‐scale to medication refills) (8 items, 8 to 32, lower, score is better) |

IG: 99 CG: 101 |

At 1‐week follow‐up | 10.3 | 9.9 | No variance per study group reported, but MD of change scores: MD 0.5 (95% CI ‐0.1 to 1.1) "Each 1‐point increase in BHLS score was associated with a decrease of 0.1 (95% CI, –0.2 to 0.0) in the ARMS score." (Mohan 2014) |

*Results are unadjusted mean (SD) if not otherwise reported.

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; ARMS: Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale; CI: confidence interval; CSC: Cardiovascular Health Questionnaire; EMR: Electronic Medical Record; FOBT: faecal occult blood test; GEE: generalised estimating equations; HB‐MAS: Hill‐Bone Medication Adherence Scale; HBV: hepatitis B virus; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; Pap test: Papanicolaou test; PSA: prostate‐specific antigen; S/C: sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy; SD: standard deviation; SDSCA: Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course versus no/unrelated health literacy intervention, Outcome 5: Health behaviour: fat‐related dietary habits, self‐report (short‐term: 1‐month post‐intervention)

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course versus no/unrelated health literacy intervention, Outcome 6: Health behaviour: any screening adherence, odds ratio short‐/medium‐term: up to 6 months post‐intervention)

5. Outcome category: self‐efficacy.

| Study ID | Health topic | Measure | No. of participants | Time point(s) |

Intervention arm Mean (SD)* |

Control arm Mean (SD)* |

Notes |

| 1 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Rosal 2011 | Diabetes type 2 | Self‐efficacy in diabetes management; LSESLD (17 items, 17 to 68, higher score is better) |

IG: 124 CG: 128 |

4 months after randomisation | 0.448 (0.362 to 0.534) | 0.132 (0.040 to 0.219) | Mean (range) is reported P < 0.001 For meta‐analysis, the final SD was substituted with the reported baseline SD (Analysis 1.9) |

| 12 months after randomisation | 0.448 (0.0348 to 0.548) | 0.213 (0.113 to 0.313) | P = 0.001 | ||||

| van Servellen 2005 | HIV | Self‐efficacy for HIV medication adherence; adherence behaviours baseline questionnaire (item from the ACTG) (1 question on certainty to take medications correctly, 0 = not at all sure to 3 = extremely sure, higher scores are better) |

IG: 41 CG: 40 |

At 6 weeks after randomisation | 0.27 (0.92) | ‐0.08 (0.92) | Intervention group: P ≥ 0.10 Change scores are reported |

| IG: 34 CG: 35 |

At 6 months after randomisation | 0.12 (0.95) | ‐0.06 (0.59) | Change scores are reported | |||

| 2 Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Kim 2009 | Diabetes type 2 | Adapted Stanford Chronic Disease Self‐Efficacy Scale (8 x 10‐point Likert items, 0 to 80, 1 = not confident at all, 4 = very confident, higher scores are better) |

IG: 40 CG: 39 |

18 weeks after randomisation | 8.7 (11.4) | 2.6 (15.0) | Change scores are reported P = 0.02 |

| 30 weeks after randomisation | 6.6 (14.4) | ‐0.9 (15.1) | Change scores are reported P = 0.01 |

||||

| Kim 2014 | HBP | Self‐efficacy in managing high blood pressure; questionnaire adapted from the HBP belief scale (8 items, 4‐point Likert scale, 1 = not confident at all, 4 = very confident, 8 to 32, higher scores are better) |

IG: 184 CG: 185 |

12 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | 26.6 (3.2) | 25.4 (3.7) | Cluster‐RCT; data have been re‐analysed for meta‐analysis using the appropriate unit of analysis with the use of the ICC reported by Han 2017 (see Analysis 2.23; Analysis 2.25) Group x time P = 0.001 (at 12 months) |

| 18 months after randomisation (6‐month follow‐up) | 25.9 (3.7) | 26.1 (3.9) | |||||

| Kim 2020 | Diabetes type 2 | Adapted Stanford Chronic Disease Self‐Efficacy Scale (8 items, 10‐point Likert scale, 0 to 80, 1 = not confident at all, 4 = very confident, higher scores are better) |

IG: 105 CG: 104 |

12 months after randomisation | 58.6 (SE 1.2) | 46.5 (SE 1.6) | P < 0.001 |

| Rosal 2005 | Diabetes type 2 | IMDSES (26 items, 4‐point Likert‐scale, 1 = "low confidence" to 4 = "high confidence", 26 to 104, higher scores are better) |

IG: 15 CG: 10 |

3 months after randomisation (immediately post‐intervention) | Self‐efficacy for

(1) Diet 0.03 (0.4) (2) Exercise 0.11 (0.9) (3) Self‐monitoring 0.3 (1.0) (4) Oral glycaemic agents ‐0.1 (0.3) (5) Insulin ‐0.14 (1.3) |

Self‐efficacy for

(1) Diet 0.44 (0.3)* (2) Exercise 0.24 (0.6) (3) Self‐monitoring –0.3 (0.7) (4) Oral glycaemic agents 0 (0) (5) Insulin –0.2 (0.5) |

Change scores are reported No composite score reported. For meta‐analysis, a single score was calculated (see Analysis 2.23) |

| 6 months after randomisation (4.5 months post‐intervention) | (1) Diet 0.10 (0.6) (2) Exercise 0.04 (0.6) (3) Self‐monitoring 0.30 (1.0) (4) Oral glycaemic agents 0.04 (0.1) (5) Insulin 0.01 (0.6) |

(1) Diet 0.13 (0.4) (2)Exercise –0.14 (1.0) (3) Self‐monitoring –0.07 (0.7) (4) Oral glycaemic agents –0.25 (0.5) (5) Insulin –0.27 (0.4) |

|||||

| 3 Culturally adapted health literacy skills building course vs unrelated health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Elder 1998 | Nutrition/cardiovascular health | Self‐efficacy to change one's diet (5 items, 1 to 3, higher score is better) |

IG: 133 CG: 157 |

3 months post‐intervention | 2.29 | 2.25 | No difference Cluster‐RCT; unadjusted values are reported |

| At 6‐month follow‐up | 2.30 | 2.27 | |||||

| 5 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs no health literacy intervention | |||||||

| Hernandez 2013 | Depression | Self‐efficacy to identify the need for treatment scale (3 items, 5‐point Likert scale, 1 = not sure, 5 = very sure, 0 to 15, higher scores are better) |

IG: 70 CG: 63 |

Immediately post‐intervention | 3.64 (3.36) | 0.13 (2.35) | Change scores are reported P < 0.001 |

| 6 Culturally and literacy adapted audio‐/visual education without personal feedback vs written information on the same topic | |||||||

| Gwede 2019 | Colorectal cancer | Self‐efficacy for screening using FIT (6 items, 6 to 30, higher scores indicating higher levels of self‐efficacy) |

IG: 27 CG: 36 |

At 3‐month follow‐up | 29.7 (1.0) | 29.5 (1.3) | P = 0.039 |

| Poureslami 2016b (4‐arms, COPD) | COPD | COPD Self‐Efficacy Scale (short version) (5 items, 5‐point Likert‐scale, 1 = not at all confident to 5 = totally confident, higher scores are better) |

Group 3: 29 Group 4: 14 |

3 months post‐intervention | (1) Prepared to manage COPD Group 3 vs Group 4 0.87 (0.04 to 1.71), P < 0.05 (2) Perception of being informed about COPD Group 3 vs Group 4 0.12 (‐0.65 to 0.90), P < 0.05 (3) Remain calm when facing a worsening of COPD Group 3 vs Group 4 0.28 (‐0.54 to 1.11), N/S (4) Ability to achieve goals in managing COPD Group 3 vs Group 4 1.05 (0.08 to 2.02), P < 0.05 (5) Ability to self‐manage COPD symptoms Group 3 vs Group 4 0.38 (‐1.18 to 0.41), P < 0.05 |

No composite score reported MD (95% CI), P values are reported No difference between female and male participants |

|

| Payán 2020 | Breast cancer | Self‐efficacy in accessing breast cancer‐related advice or information (1 item, "Overall, how confident are you that you could get advice or information about breast cancer if you needed it?”, 5‐point Likert scale 1 = "completely confident" to 3 = "not confident at all" (3), higher scores are better) |

IG 1: 79 IG 2: 79 CG: 82 |

Immediately post‐intervention | IG 1: 0.87 (0.34) IG 2: 0.89 (0.32) IG 1, 2: 0.88 (0.33) |

0.80 (0.40) | Final values were obtained from study authors IG 1 and IG 2 were combined to create a single pairwise comparison |

| IG 1: 67 IG 2: 61 CG: 65 |

At 3‐month follow‐up | IG 1: 0.67 (0.47) IG 2: 0.88 (0.33) IG 1, 2: 0.77 (0.42) |

0.75 (0.44) | ||||

| Unger 2013 | Depression | Self‐efficacy to identify depression (2 items, 10‐point Likert scale, 1 = "not at all confident" to 10 = "very confident", higher scores are better) |

IG: 69 CG: 70 |

Immediately post‐intervention | t = 4.54, P < 0.05 | t = 3.16, P < 0.05 | — |

| At 1‐month follow‐up | t = 3.31, P < 0.05 | t = 3.00, P < 0.05 | "[T]he data collectors reported that several students shared their photonovel with students in the text pamphlet group after the posttest." (Unger 2013, p. 405). | ||||

| Valdez 2018 | Cervical cancer/Pap testing | Self‐efficacy regarding Pap smear (1 item, "Can get a pap smear if needed", yes/no) |

IG: 383 CG: 344 |

6‐month follow‐up | n: 356, 93 % | n: 314, 91 % | P = 0.40 |

* Unadjusted mean (SD) if not otherwise reported.

ACTG: Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group; CG: control group; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FIT: faecal immunochemical test; HBP: high blood pressure; IG: intervention group; IMDSES: Insulin Management Self‐Efficacy Scale; LSESLD: Lifestyle Self‐Efficacy Scale for Latinos with Diabetes; MD (95% CI): mean difference (95% confidence interval); N/S: not significant; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error ; Pap: Papanicolaou

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus no HL intervention, Outcome 9: Self‐efficacy to manage one's disease (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention)

2.23. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 23: Self‐efficacy to manage one's disease (short‐term: immediately post‐intervention) ‐ all studies

2.25. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information, Outcome 25: Self‐efficacy to manage one's disease (medium‐term: 6 months post‐intervention)

Summary of findings 2. Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information on the same topic.

| Culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme versus written information on the same topic | ||||||

| Patient or population: migrants Setting: all settings Intervention: culturally and literacy adapted self‐management programme Comparison: written information on the same topic (standard brochure, or written pamphlet) | ||||||

| Outcome category – outcome(s)* | Anticipated absolute effects** (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with written information on the same topic | Risk with self‐management programme | |||||

|

Health literacy – Time point a: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention)*** (1) Any generic health literacy Multiple outcomes assessed and multiple measures used:

Higher score is better (2) Any disease‐specific health literacy Multiple measures used:

Higher score is better (3) Appraising health information Assessed with:

Higher score is better Time point b: medium‐term (6 months post‐intervention) (1) Disease‐specific health literacy

Higher score is better |

Time point a: short‐term | — | 209 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic probably improve health numeracy slightly and probably improve print literacy immediately post‐intervention. | |

|

(1) Any generic health literacy One RCT reported that the intervention slightly increased health numeracy (NVS) immediately post‐intervention (MD 0.7 points higher (0.15 higher to 1.25 higher)). The same RCT reported that the intervention increased generic print literacy (REALM) immediately post‐intervention (MD 9.00 points higher (2.90 higher to 15.10 higher)). | ||||||

|

(2) Any disease‐specific health literacy The mean disease‐specific health literacy score across intervention groups was 0.67 standard deviations higher (0.27 higher to 1.07 higher) immediately post‐intervention. |

— | 955 (2 RCTs, 2 cluster‐RCTs1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may improve any disease‐specific health literacy immediately post‐intervention.2 | ||

|

(3) Appraising health information (decisional balance for using mammography or Pap testing) The mean decisional balance score in the intervention group was MD 1.15 points higher (0.23 lower to 2.53 higher) than in the control group immediately post‐intervention.3 |

— | 329 (1 cluster‐RCT1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd,e | Self‐management programmes compared to written information may have little or no effect on the appraisal of health information (decisional balance) immediately post‐intervention. | ||

| Time point b: medium‐term | — | (242) (1 cluster‐RCT1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may slightly improve high blood pressure health literacy 6 months after the programme was completed. | ||

| The mean high blood pressure health literacy in the control group was 25.3 | The mean high blood pressure health literacy in the self‐management group was MD 4.10 higher (0.97 higher to 7.23 higher) than in the control group | |||||

|

Quality of life – Diabetes‐related quality of life standardised on score 0 (no quality of life) to 100 (perfect quality of life) Time point: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) |

The mean score for diabetes‐related quality of life ranged from 66.5% to 96.2% | The mean diabetes‐related quality of life score in the intervention groups was MD 9.06 points higher (2.85 higher to 15.27 higher) | — | 288 (2 RCTs)3 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,f,g | We are uncertain whether self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic improve diabetes‐specific quality of life immediately post‐intervention. |

|

Health‐related knowledge – Time point a: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) Any health‐related knowledge standardised on score 0 (no knowledge) to 100 (perfect knowledge) Time point b: medium‐term (up to 6 months post‐intervention) Any health‐related knowledge standardised on score 0 (no knowledge) to 100 (perfect knowledge) |

Time point a: short‐term | — | 1101 (4 RCTs, 2 cluster‐RCTs1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowh,i | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may improve health‐related knowledge immediately post‐intervention. | |

| The mean health‐related knowledge score across control groups ranged from 24.4% to 74.2% | The mean score in the intervention groups was MD 11.45 points higher (4.75 higher to 18.15 higher) | |||||

| Time point b: medium‐term | — | 298 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd,e | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may have little or no effect on health‐related knowledge up to 6 months post‐intervention. | ||

| The mean health‐related knowledge score across control groups was 73.7% | The mean knowledge score in the intervention groups was MD 3.87 points higher (0.46 lower to 8.19 higher) | |||||

|

Health outcome – Any depression Time point a: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) Multiple measures used:

Lower score is better Time point b: medium‐term (up to 6 months post‐intervention) Multiple measures used:

Lower score is better |

Time point a: short‐term | — | 555 (3 RCTs, 1 cluster‐RCT1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowj,k,l | We are uncertain whether self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic improve depression immediately post‐intervention. | |

| — | The mean depression score in the intervention group was 0.19 standard deviations lower (0.62 lower to 0.23 higher) | |||||

| Time point b: medium‐term | — | 267 (1 RCT, 1 cluster‐RCT1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe,m | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may have little or no effect on depression 6 months post‐intervention.2 | ||

| — | The mean depression score in the intervention group was 0.32 standard deviations lower (0.90 lower to 0.27 higher) | |||||

|

Health behaviour – Multiple outcomes assessed and multiple measures used Time point a: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) (1) Diabetes self‐care activities

(2) Oral self‐care behaviour

(3) Cervical/breast cancer screening adherence

(4) Non‐adherence to blood pressure medication:

Time point b: medium‐term (up to 6 months post intervention) (1) Non‐adherence to blood pressure medication

(2) Blood glucose self‐monitoring:

|

Time point a: short‐term (1) Diabetes self‐care activities One RCT (n = 79) reported that the self‐management programme improved diabetes self‐care activities (MD 15 points higher (7.87 higher to 22.13 higher) (2) Oral self‐care behaviour One RCT (n = 140) found that the intervention improved self‐reported oral self‐care behaviour (MD 3.1 points higher (2.5 higher to 3.7 higher) (3) Cervical/breast cancer screening adherence One cluster RCT (n = 336) that properly accounted for the cluster design, found that the intervention improved cervical/breast cancer screening adherence (RR 7.17, 95% CI 3.96 to 12.99)8 (4) Non‐adherence to blood pressure medication One cluster‐RCT (N = 242) reported that the mean non‐adherence to blood pressure medication was 0.4 points lower (0.87 lower to 0.07 higher) in the intervention group. The mean non‐adherence score in the control group was 9.2. |

— | 797 (2 RCTs, 2 cluster‐RCTs)6,7 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowm,n | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may improve health behaviour immediately post‐intervention, but measures and sizes of effects appear variable. | |

|

Time point b: medium‐term (1) Non‐adherence to blood pressure medication One cluster‐RCT (n = 242) reported that the intervention had slightly lower scores on non‐adherence to blood pressure medication (MD 0.40 points lower (0.78 lower to 0.02 lower)). The mean non‐adherence score in the control group was 8.8. (2) Blood glucose self‐monitoring One RCT (n = 23) reported greater self‐reported blood glucose‐self‐monitoring in the intervention groups 4.5 months post‐intervention (RR 1.96, 95% CI 0.76 to 5.03). |

— | 265 (1 RCT, 1 cluster‐RCT1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowl,o | Self‐management programmes compared to written information on the same topic may slightly improve health behaviour 6 months post‐intervention, but outcome measures and size of effects appear variable. | ||

|

Self‐efficacy– Self‐efficacy to manage one's disease Time point a: short‐term (immediately post‐intervention) Multiple measures used:

Higher score is better Time point b: medium‐term (up to 6 months post‐intervention) Self‐efficacy to manage high blood pressure

Higher score is better |

Time point a: short‐term | — | 552 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatej | Self‐management programmes probably improve self‐efficacy immediately post‐intervention, when compared to written information on the same topic.9 | |

| — | The mean self‐efficacy score in the intervention group was 0.47 standard deviations higher (0.30 higher to 0.64 higher) | |||||

| Time point b: medium‐term | — | 242 (1 cluster‐RCT1) |