Abstract

It has long been known that relatively high-dose ionising radiation exposure (>1 Gy) can induce cataract, but there has been no evidence that this occurs at low doses (<100 mGy). To assess low-dose risk, participants from the US Radiologic Technologists Study, a large, prospective cohort, were followed from date of mailed questionnaire survey completed during 1994-1998 to the earliest of self-reported diagnosis of cataract/cataract surgery, cancer other than non-melanoma skin, or date of last survey (up to end 2014). Cox proportional hazards models with age as timescale were used, adjusted for a priori selected cataract risk factors (diabetes, body mass index, smoking history, race, sex, birth year, cumulative UVB radiant exposure). 12,336 out of 67,246 eligible technologists reported a history of diagnosis of cataract during 832,479 person years of follow-up, and 5509 from 67,709 eligible technologists reported undergoing cataract surgery with 888,420 person years of follow-up. The mean cumulative estimated 5-year lagged eye-lens absorbed dose from occupational radiation exposures was 55.7 mGy (interquartile range 23.6-69.0 mGy). Five-year lagged occupational radiation exposure was strongly associated with self-reported cataract, with an excess hazard ratio/mGy of 0.69 x 10−3 (95% CI 0.27 x 10−3 to 1.16 x 10−3, p<0.001). Cataract risk remained statistically significant (p=0.030) when analysis was restricted to <100 mGy cumulative occupational radiation exposure to the eye lens. A non-significantly increased excess hazard ratio/mGy of 0.34 x 10−3 (95% CI −0.19 x 10−3 to 0.97 x 10−3, p=0.221) was observed for cataract surgery. Our results suggest that there is excess risk for cataract associated with radiation exposure from low-dose and low dose-rate occupational exposures.

Keywords: ionising radiation, cataract, cataract surgery, threshold, tissue reaction effects, diabetes, low dose rate, questionnaire-based assessment

Introduction

By age 75 years over half of the US population will have a cataract (https://www.nei.nih.gov/eyedata/cataract). Well over a million cataract surgeries are performed per year in the US, at the cost of several billion dollars per year (1). Well-established risk factors for cataracts include solar radiation, and specifically solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure (2), diabetes, high body mass index (BMI), cigarette smoking, use of corticosteroid medicine and ocular trauma (3-6).

It has long been known that relatively high radiation doses of 1 Gy or more can induce cataract (7). It has conventionally been assumed that cataract is a tissue-reaction (formerly deterministic) effect, so that no excess risk would be expected below a threshold dose of about 500 mGy (7, 8). Accumulating evidence from follow-up studies of the Japanese atomic bomb survivors (9-11), Chernobyl clean-up workers (12), US astronauts (13, 14) and other populations (15-17) suggests that cataracts may be induced by somewhat lower doses, of the order of 100-250 mGy (12), of ionising radiation, but none of these studies have suggested risks below 100 mGy, the level conventionally used to define low dose (18). Only in the study of atomic bomb survivors was there any test for modification of radiation risk by lifestyle and medical covariates, specifically diabetes, sex, age at exposure and time since exposure (10). Our previous study of the US radiologic technologists (USRT) cohort, based on follow-up through 2005 and using an earlier dosimetry system to approximate eye-lens radiation absorbed doses, found 2382 incident cataracts and 647 cataract extractions, and suggested, albeit weakly, that relatively low levels of cumulative radiation exposure, on the order of 60 mGy, were associated with risk of cataract and cataract surgery (19). More recently we found an excess risk of cataract among the subgroup of the USRT cohort working with nuclear medicine procedures based on work history information (20).

In this report, we evaluate risks associated with self-reported questionnaire-derived history of cataracts and cataract surgery in the USRT cohort in relation to estimated cumulative absorbed dose from occupational radiation exposures. Our assessment used an updated and improved eye-lens dosimetry (21) and an additional nine years of follow-up from the previous analysis (19), yielding at least a five-fold increase in the number of self-reported cataracts and cataract surgeries. Our study included data collected on a broad range of known and suspected risk factors for cataract. The statistical power to assess low-dose effects and possible lifestyle and medical modifying factors is therefore substantially increased.

Data and Methods

Study population and follow-up

Overview of USRT study

The USRT study population, cohort follow-up, and dosimetry methods have been described elsewhere (21-23) (see also www.radtechstudy.nci.nih.gov). Briefly, the US National Cancer Institute, in collaboration with the University of Minnesota and the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists (ARRT), is studying cancer and other serious health effects in relation to low-to-moderate dose protracted ionising radiation among 146,021 (106,952 women) US radiologic technologists who were certified for at least two years during 1926-1982 (24, 25). Active follow-up was conducted through yearly re-certification with the ARRT. Inactive registrants were linked with national and other databases, including the Social Security Administration and National Death Index, to determine vital status and obtain causes of death. Four questionnaires were administered during 1983–1989, 1994–1998, 2003–2005, and 2012-2014 to collect information on health outcomes (including self-reports of cataract and cataract surgery in all but the first questionnaire), work history, demographic and lifestyle characteristics, and medical histories. The first and second questionnaires were sent to all eligible participants, while the third and fourth questionnaires were sent only to cohort members who had responded to the first and/or the second questionnaire. The response rate for each of the questionnaires among living and located cohort members was 68-72% for the first three surveys and 63% for the fourth survey, with 110,373 individuals completing one or more questionnaires.

Eligible study population and follow-up

Since data on cataract and cataract surgery were only elicited in the second through fourth questionnaires, we only included responders to the second or third questionnaire and at least one subsequent questionnaire for follow-up of these ocular endpoints. We censored follow-up after a diagnosis of cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer [NMSC]) because of the potential for radiotherapy that the subject might receive. After excluding 8252 technologists who reported a history of radiotherapy on the first or second surveys, and (a) a further 1217 with inconsistent questionnaire responses for cataract and 33,658 who were not informative for cataract (because they had cataract at first questionnaire responded to, or gave incomplete information in subsequent questionnaires), or (b) 343 with inconsistent responses for cataract surgery and a further 32,532 not informative for this endpoint (for analogous reasons as those for cataract morbidity), and excluding also 1536 persons reporting cataract at the first questionnaire responded to, there were a total of 67,246 technologists eligible for study of cataract and 67,709 eligible for study of cataract surgery (see Appendix A Figure A1 for a flow diagram showing the exclusions). Further details on eligibility criteria are given in Appendix A. As implied by Appendix A, cataract surgeries are not a subset of cataract cases, nor vice versa.

Individuals were deemed at risk for developing cataract or undergoing cataract surgery during any of the time periods between completion of the (a) second to third questionnaire, (b) second to fourth questionnaire, and (c) third to fourth questionnaire. For each endpoint, namely (1) self-reported history of diagnosis of cataract (henceforth termed “cataract history”), and (2) self-reported cataract surgery (henceforth termed “cataract surgery”), individuals were included in each inter-questionnaire period during which they were free of these outcomes (i.e., did not report either (1) a history of diagnosis of cataract, or (2) undergoing cataract surgery, respectively at the first of the pair of questionnaires), and had unambiguous indication of cataract history and year of diagnosis, or of cataract surgery and year of surgery, respectively, at the second of the pair of questionnaires. Follow-up terminated at the earliest of (a) date of first cataract history, or date of first cataract surgery, respectively, (b) date the final questionnaire was completed, or (c) the date of diagnosis of any cancer other than NMSC. Further details on the precise definitions of dates of start and end of follow-up per individual are given in Appendix A.

Dosimetry

Occupational doses

A historical dose reconstruction was undertaken to estimate annual radiation absorbed doses to specific organs from occupational exposure for each radiologic technologist, described in more detail in Appendix B and in Simon et al. (21). Annual reported badge doses were used for each technologist when available; otherwise, doses were estimated from probability density functions based on population exposure data for each year worked, modified by a work history questionnaire-derived exposure score. All annual reported badge doses, in terms of personal dose equivalent () (mSv), were estimated up to December 31st 1997. The individual annual dose estimates used in analyses were regression-calibration estimates, adjusted for dose uncertainties (26). Questionnaire response was used to modify badge doses for the estimation of eye-lens absorbed doses. The doses reflect exposures from performing or assisting in diagnostic and therapeutic radiological procedures, and were mostly from x-rays (21). Most radiologic technologists performed or assisted with multiple procedures, including standard fluoroscopy and multi-film and routine diagnostic radiography. A substantial fraction also worked with fluoroscopically-guided interventional procedures, and a smaller percentage with radio-pharmaceutical procedures (21, 27). Eye-lens absorbed doses were estimated from measured or estimated personnel monitoring badge doses using badge-dose-to-organ-absorbed-dose conversion factors based on beam energy (kV) and x-ray beam filtration specific to each kV and time period (28).

Covariates

The following questionnaire-derived variables were selected a priori as adjusting covariates in most regression models because of their known effect on cataract prevalence (3-5), and because they were considered potential confounders in the relationship with radiation dose. These variables included sex, racial/ethnic group, birth year, diabetes, BMI, smoking status (current smoker/ex-smoker/never smoker, numbers of cigarettes/day, age stopped smoking), and cumulative ambient UVB radiant exposure (Appendix C). Cataract is thought to result from cumulative oxidative stress in the eye lens (29), one component of which is associated with cumulative UVA exposure, as UVA is thought more directly capable of penetrating to the eye lens than UVB (30). However, as UVA and UVB are highly correlated (also correlated with total solar exposure)(see Appendix C) it suffices to use UVB for adjustment purposes. Corticosteroid use, a well known risk factor for cataract (4), was not elicited on any of the USRT questionnaires. Data for the a priori-specified potential confounding variables were obtained from the first questionnaire responded to. Because UVB radiation can only be estimated for the subset of persons who answered the third questionnaire, an indicator for UVB missing data was also included in the baseline risk model.

Statistical methods

Risks for cataract and cataract surgery were assessed using Cox proportional hazards models (31), with age as the timescale, in which the hazard ratio (HR) (which is the same thing as the relative risk computed at a particular instant) for individual at age was given by:

| (1) |

where is the time-varying cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose in mGy, lagged by 5 years to allow for disease latency (8, 17), are the lifestyle (e.g., cigarette smoking history), environmental (e.g., UVB), and medical risk factors (e.g., diabetes, obesity), is the excess HR coefficient (EHR) (which is same thing as the excess relative risk computed for a particular instant) per unit eye-lens dose (mGy), and () are coefficients adjusting for other risk factors. So it is in some sense the case that . A detailed description of the method used to estimate age at entry and exit are described in Appendix A. We also conducted analysis taking into account variation in cataract risk in relation to dose accumulated in various temporal windows, of time from the indicated radiation exposure to the time at risk and from age at exposure to the time at risk. Further details are given in Appendix D. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted using lag periods of 0 to 10 years (Appendix D Table D1). Models were also fitted using linear-exponential forms of dose response (Appendix D Table D2).

As indicated above, persons with previous radiotherapy were selected a priori as a category that should be excluded, and for similar reasons persons developing cancer other than NMSC were censored at occurrence of cancer, because of the potential of such cancer to be treated with radiotherapy. Indeed, preliminary analysis performed suggested that both radiotherapy and cancer other than NMSC were correlated with the cataract or cataract surgery and with occupational radiation exposure, and as such were potential confounders (analysis not shown). Nevertheless, we also show analysis in which persons with radiotherapy were added back in or cancer censoring was removed (Appendix D Table D3).

For reasons outlined more precisely in Appendix D all model fits to cataract surgery were restricted to those without cataract incidence at baseline questionnaire, and employed adjustment to the baseline hazard for time since baseline questionnaire (an indicator variable for this quantity being <5 years) and restricted radiogenic excess risk to the period ≥5 years from baseline questionnaire.

The HRs given in Tables 1 and 2 were derived using model (1) without any additional adjustment. In Table 2, the dose used is the cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose from occupational exposures up to December 31, 1997, the final date for which absorbed dose could be estimated based on badge dose data availability. In Tables 3, 4 and 5, eye-lens absorbed dose was treated as a time varying measure, and lagged by 5 years. Likewise, cumulative UVB radiant exposure was treated as time varying, and lagged by 5 years.

Table 1. Numbers of cases and person-years of follow-up for technologists self-reporting history of diagnosis of cataract and self-reporting cataract surgery in US radiologic technologists in relation to non-radiation risk factors.

The hazard ratios were derived using univariate Cox proportional hazards models with age as the timescale. In all cases the heterogeneity in hazard ratio was significant with p<0.001.

| Cataract history | Cataract surgery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Cases | Person years |

Hazard ratioa | Cases | Person years |

Hazard ratioa |

| Total | 12,366 | 832,479 | 5509 | 888,420 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2686 | 175,730 | 1 (reference) | 1249 | 186,602 | 1 (reference) |

| Female | 9650 | 656,749 | 1.26 (1.21, 1.31) | 4260 | 701,818 | 1.22 (1.14, 1.30) |

| Racial/ethnic group | ||||||

| White | 11,735 | 792,185 | 1 (reference) | 5249 | 845,160 | 1 (reference) |

| Black | 346 | 20,666 | 0.82 (0.74, 0.91) | 141 | 22,522 | 0.68 (0.57, 0.80) |

| Other | 255 | 19,628 | 0.74 (0.66, 0.84) | 119 | 20,737 | 0.78 (0.65, 0.93) |

| Diabetes at baseline | ||||||

| None | 11,256 | 794,319 | 1 (reference) | 4982 | 846,085 | 1 (reference) |

| Missing | 454 | 24,066 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.03) | 205 | 25,565 | 0.93 (0.81, 1.07) |

| Diabetes | 626 | 14,094 | 2.18 (2.01, 2.36) | 322 | 16,771 | 2.05 (1.83, 2.30) |

| BMI (kg/m2) at baseline | ||||||

| 18.5-24.9 (normal) | 5399 | 425,495 | 1 (reference) | 2333 | 450,427 | 1 (reference) |

| Missing | 265 | 17,612 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 131 | 18,922 | 1.09 (0.92, 1.30) |

| 0-18.4 | 138 | 11,197 | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) | 56 | 11,774 | 1.07 (0.82, 1.40) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 4211 | 248,530 | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1962 | 267,464 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.18) |

| ≥30.0 | 2323 | 129,645 | 1.26 (1.20, 1.32) | 1027 | 139,833 | 1.29 (1.20, 1.39) |

| Baseline smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoked | 6269 | 478,669 | 1 (reference) | 2702 | 507,248 | 1 (reference) |

| Missing smoking status | 102 | 6,155 | 0.83 (0.69, 1.01) | 55 | 6726 | 0.88 (0.68, 1.16) |

| Former smoker | 4356 | 247,719 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 2027 | 267,868 | 1.04 (0.99, 1.11) |

| Current smoker | 1609 | 99,937 | 1.18 (1.12, 1.25) | 725 | 106,578 | 1.30 (1.20, 1.41) |

| Baseline smoking quantity (cigarettes/day) | ||||||

| Missing/never smoker | 6612 | 499,425 | 1 (reference) | 2868 | 529,847 | 1 (reference) |

| 0-9 | 970 | 64,105 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | 434 | 68,511 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.05) |

| 10-19 | 1810 | 117,129 | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 841 | 125,119 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) |

| 20-29 | 2038 | 111,527 | 1.13 (1.08, 1.19) | 928 | 120,690 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.23) |

| 30-39 | 515 | 25,013 | 1.19 (1.08, 1.30) | 243 | 27,271 | 1.28 (1.12, 1.45) |

| 40-49 | 294 | 12,237 | 1.24 (1.11, 1.40) | 147 | 13,524 | 1.35 (1.14, 1.59) |

| 50-59 | 51 | 1550 | 1.56 (1.18, 2.05) | 25 | 1752 | 1.60 (1.08, 2.37) |

| ≥60 | 46 | 1493 | 1.27 (0.95, 1.69) | 23 | 1706 | 1.35 (0.90, 2.04) |

| Baseline age at stopping smoking (years) | ||||||

| Never stopped/never smoked | 6602 | 501,662 | 1 (reference) | 2875 | 532,153 | 1 (reference) |

| 0-19 | 54 | 5398 | 0.98 (0.75, 1.27) | 13 | 5610 | 0.57 (0.33, 0.98) |

| 20-29 | 1073 | 90,257 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | 416 | 95,444 | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) |

| 30-39 | 1359 | 98,172 | 1.08 (1.02, 1.15) | 580 | 104,309 | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) |

| 40-49 | 1644 | 97,094 | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) | 732 | 104,333 | 1.23 (1.14, 1.34) |

| 50-59 | 1216 | 34,374 | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) | 675 | 39,815 | 1.24 (1.14, 1.35) |

| ≥60 | 388 | 5522 | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | 218 | 6755 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.10) |

| Birth year | ||||||

| <1920 | 121 | 750 | 2.11 (1.67, 2.66) | 26 | 892 | 0.13 (0.08, 0.20) |

| 1920-1929 | 912 | 10,227 | 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) | 439 | 13,230 | 0.32 (0.28, 0.37) |

| 1930-1939 | 3203 | 72,202 | 0.86 (0.81, 0.90) | 2007 | 88,490 | 0.64 (0.59, 0.69) |

| 1940-1949 | 5385 | 282,846 | 1 (reference) | 2225 | 307,795 | 1 (reference) |

| ≥1950 | 2,715 | 466,455 | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) | 812 | 478,014 | 1.33 (1.20, 1.48) |

p-values of heterogeneity (assessed via likelihood ratio test) are all p<0.001.

Table 2. Numbers of cases and person-years of follow-up for technologists self-reporting history of diagnosis of cataract and self-reporting cataract surgery in US radiologic technologists in relation to cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose from occupational exposures (non time-varying).

The hazard ratios were derived using a Cox proportional hazards model with age as timescale, unadjusted for any other covariate.

| Eye-lens absorbed dose (mGy) |

Cataract history | Cataract surgery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Person years |

Hazard ratioa | Cases | Person years | Hazard ratioa | |

| <10.0 | 415 | 43,386 | 1 (reference) | 174 | 45,096 | 1 (reference) |

| 10.0-19.9 | 948 | 125,145 | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) | 345 | 129,319 | 1.00 (0.83, 1.20) |

| 20.0-49.9 | 3874 | 363,712 | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | 1566 | 381,068 | 1.11 (0.95, 1.30) |

| 50.0-99.9 | 4027 | 217,756 | 1.15 (1.04, 1.27) | 1853 | 237,159 | 1.22 (1.05, 1.43) |

| 100.0-199.9 | 2302 | 71,356 | 1.15 (1.03, 1.27) | 1212 | 82,074 | 1.27 (1.08, 1.49) |

| 200.0-499.9 | 722 | 10,774 | 1.32 (1.17, 1.50) | 347 | 13,231 | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) |

| ≥500.0 | 48 | 350 | 1.76 (1.29, 2.40) | 12 | 473 | 0.61 (0.33, 1.10) |

p-values of heterogeneity (assessed via likelihood ratio test) are all p<0.001.

Table 3. Occupational radiation risks of self-reported history of diagnosis of cataract and self-reported cataract surgery, in relation to maximum cumulative eye lens absorbed dose.a.

| Dose range | Endpoint | Cases | EHR / mGy x 103 (+95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-100 mGy | Cataract history | 9264 | 1.16 (0.11, 2.31) | 0.030 |

| Cataract surgery | 3938 | 0.39 (−1.15, 2.22) | 0.638 | |

| 0-200 mGy | Cataract history | 11,566 | 1.07 (0.47, 1.72) | <0.001 |

| Cataract surgery | 5150 | 0.17 (−0.59, 1.05) | 0.675 | |

| Unrestricted | Cataract history | 12,336 | 0.69 (0.27, 1.16) | <0.001 |

| Cataract surgery | 5509 | 0.34 (−0.19, 0.97) | 0.221 |

Risks are evaluated using a Cox model with age as timescale, with stratification by sex and race and birth year (by decade <1900, 1900-1909, …, 1950-1959, ≥1960), and with adjustment to the baseline hazard for diabetes, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (current smoker/ex-smoker/never smoker, numbers of cigarettes/day, age stopped smoking), each ascertained at the baseline survey, and cumulative UVB radiant exposure, ascertained in the course of follow-up. For each endpoint (cataract, surgical cataract extraction) follow-up is restricted to those persons eligible for study (no record of radiotherapy or disease at baseline, unambiguous status at end of follow-up (with both fact and year of self-reported diagnosis known) etc)(see Methods). For cataract surgery the baseline hazard was adjusted by 1years since baseline questionnaire < 5 years, and excess risk was limited to ≥5 years after baseline questionnaire.

Table 4. Excess hazard ratio (EHR) of self-reported history of diagnosis of cataract and self-reported cataract surgery in US radiologic technologists in relation to cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose from occupational exposures (+95% CI), and modifications by various lifestyle and environmental risk factors.

Other notes are as for Table 3.

| Cataract history | Cataract surgery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | EHR/mGy x 103 (+95% CI) |

Heterogeneity p- value |

Cases | EHR/mGy x 103 (+95% CI) |

Heterogeneity p-value |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 2686 | 0.25 (−0.35, 1.02) | 0.151 | 1249 | 0.19 (−0.60, 1.26) | 0.688 |

| Female | 9650 | 0.91 (0.39, 1.50) | 4260 | 0.42 (−0.22, 1.19) | ||

| Racial group | ||||||

| White | 11,735 | 0.72 (0.31, 1.23) | 0.425 | 5,249 | 0.35 (−0.17, 0.94) | 0.358 |

| Black | 346 | −1.11 (−2.43, 1.14) | 141 | −1.44 (−3.09, 1.75) | ||

| Other | 255 | 0.31 (−1.95, 4.69) | 119 | −0.75 (−2.08, 2.92) | ||

| Age attained | ||||||

| age < 50 | 655 | 6.29 (0.59, 15.40) | 0.083 | 166 | -4.09 (−8.18a, 3.08) | 0.542 |

| age 50-59 | 3570 | 1.11 (−0.11, 2.54) | 1013 | 0.73 (−1.36, 3.46) | ||

| age 60-69 | 5741 | 1.01 (0.32, 1.79) | 2404 | 0.53 (−0.43, 1.67) | ||

| age ≥ 70 | 2370 | 0.29 (−0.19, 0.89) | 1926 | 0.25 (−0.35, 1.00) | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||||

| BMI < 18.5 (underweight) | 138 | 0.87 (0.35, 1.45) | 0.288 | 56 | 0.36 (−0.30, 1.13) | 0.893 |

| BMI 18.5-24.9 or unknown (normal) | 5664 | −0.64 (−2.08, 1.51) | 2464 | 1.03 (−2.23, 5.70) | ||

| BMI 25.0–29.9 (overweight) | 4211 | 0.69 (0.19, 1.25) | 1962 | 0.22 (−0.41, 0.98) | ||

| BMI ≥ 30 (obese) | 2323 | 0.36 (−0.27, 1.09) | 1027 | 0.54 (−0.35, 1.64) | ||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No diabetes/missing | 11,710 | 0.85 (0.40, 1.34) | 0.002 | 5187 | 0.46 (−0.10, 1.12) | 0.063 |

| Diabetes | 626 | −0.95 (−1.57, 0.03) | 322 | −0.96 (−1.93, 0.53) | ||

| Baseline smoking status | ||||||

| Unknown smoking status | 102 | 3.63 (0.28, 11.14) | 0.180 | 55 | 2.56 (−1.71, 12.82) | 0.722 |

| Never smoked | 6269 | 0.74 (0.19, 1.36) | 2702 | 0.53 (−0.19, 1.41) | ||

| Former smoker | 4356 | 0.76 (0.17, 1.44) | 2027 | 0.20 (−0.46, 1.04) | ||

| Current smoker | 1609 | −0.04 (−0.86, 0.99) | 725 | 0.05 (−1.07, 1.54) | ||

| Baseline smoking quantity (cigarettes/day) | ||||||

| Missing/never smoker | 6612 | 0.81 (0.28, 1.42) | 0.605 | 2868 | 0.60 (−0.11, 1.45) | 0.260 |

| 0-9 | 970 | 0.47 (−0.40, 1.53) | 434 | 0.13 (−1.09, 1.69) | ||

| 10-19 | 1810 | 0.96 (0.21, 1.83) | 841 | 0.82 (−0.34a, 2.01) | ||

| 20-29 | 2038 | 0.61 (−0.05, 1.37) | 928 | −0.07 (−0.83, 0.85) | ||

| 30-39 | 515 | −0.05 (−1.02, 1.14) | 243 | −0.78 (−1.55, 0.69) | ||

| 40-49 | 294 | −0.18 (−1.31, 1.32) | 147 | −0.77 (−2.52, 1.40) | ||

| 50-59 | 51 | 0.91 (−1.83, 5.10) | 25 | −0.70 (−3.72, 4.60) | ||

| ≥60 | 46 | −0.76 (−2.03, 1.83) | 23 | −2.49 (−3.48, 0.25) | ||

| Baseline age at stopping smoking (years) | ||||||

| Never stopped/never smoked | 6602 | 0.84 (0.30, 1.46) | 0.282 | 2875 | 0.58 (−0.12, 1.35a) | 0.347 |

| 0-19 | 54 | 0.67 (−2.53, 5.84) | 13 | −3.79 (−6.97a, 1.98) | ||

| 20-29 | 1073 | 0.27 (−0.78, 1.55) | 416 | 0.52 (−0.81, 2.43) | ||

| 30-39 | 1359 | 1.01 (0.14, 2.02) | 580 | 0.64 (−0.55, 2.11) | ||

| 40-49 | 1644 | 1.03 (0.21, 1.96) | 732 | 0.31 (−0.64, 1.43a) | ||

| 50-59 | 1216 | 0.35 (−0.33, 1.18) | 675 | 0.13 (−0.78, 1.25) | ||

| ≥60 | 388 | 0.02 (−0.71, 0.96) | 218 | −0.64 (−1.54a, 0.51) | ||

| Birth year | ||||||

| <1920 | 121 | 0.10 (−0.68, 2.33) | 0.507 | 26 | >1000b (<−1000a, >1000a) | 0.084b |

| 1920-1929 | 912 | 0.37 (−0.28, 1.25) | 439 | −0.17b (−0.79, 0.85) | ||

| 1930-1939 | 3203 | 0.60 (−0.06, 1.36) | 2007 | 0.65b (−0.16, 1.64) | ||

| 1940-1949 | 5385 | 1.10 (0.27, 2.04) | 2225 | 0.46b (−0.61, 1.75) | ||

| ≥1950 | 2715 | 1.69 (−0.06, 3.78) | 812 | −1.17b (−3.23, 1.71) | ||

| Cumulative UVB radiant exposure | ||||||

| UVB unknown | 1713 | 0.98 (0.08, 2.09) | 0.790 | 867 | 1.47 (0.33, 2.91) | 0.067 |

| UVB < 0.075 MJ cm−2 | 10,016 | 0.66 (0.21, 1.16) | 4190 | −0.01 (−0.51, 0.59) | ||

| UVB 0.075-0.10 MJ cm−2 | 682 | 0.50 (−0.19, 1.35) | 444 | 0.53 (−0.35, 1.64) | ||

| UVB ≥0.10 MJ cm−2 | 5 | 2.59 (−1.54, 13.85) | 8 | 2.03 (−1.84, 10.77) | ||

| Total | 12,336 | 0.69 (0.27, 1.16) | <0.001c | 5509 | 0.34 (−0.19, 0.97) | 0.221c |

Wald-based confidence intervals.

indications of non-convergence.

p-value of improvement in fit over null model (with no trend in dose), assessed via likelihood ratio test.

Table 5. Excess hazard ratio (EHR) of self-reported history of diagnosis of cataract by time since exposurea and age at exposureb in US radiologic technologists in relation to cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose from occupational radiation exposures (+95% CI).

Other notes are as for Table 3.

| EHR/mGy x 103 (+95% CI) | Heterogeneity p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk by time since exposurea | ||

| 5-9 years since exposure | 8.71 (−1.77, 20.34) | 0.323 |

| 10-14 years since exposure | −0.91 (−6.81, 5.74) | |

| ≥15 years since exposure | 0.66 (0.23, 1.14) | |

| Risk by age at exposureb | ||

| age at exposure <30 years | 0.91 (0.35, 1.53) | 0.362 |

| age at exposure 30-49 years | 0.42 (−0.40, 1.30) | |

| age at exposure ≥50 years | −0.47 (−3.20, 2.86) | |

time since exposure is the length of the interval (in years) between when radiation exposure occurs for the individual and the time at risk.

age at exposure is the age (in years) at which the individual is exposed to radiation.

Except where indicated, analyses of all endpoints in Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Figure 1 were adjusted by stratification for year of birth (categorized by: <1900, 1900-1909, …, 1950-1959, ≥1960), sex and race, and via adjustment to the baseline hazard for the a priori-determined risk factors for cataract, for the reasons given above. Nevertheless we provide (in Appendix D Table D4) analysis in which selected variables are removed as stratifying/adjusting variables. Wherever possible, these variables were derived from the first questionnaire responded to (of the second or third questionnaires). All analyses were carried out using R (32) and Epicure (33). More details are given in Appendix D.

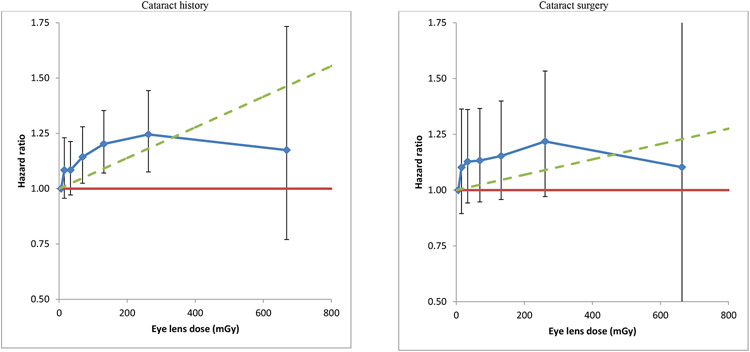

Figure 1. Adjusted hazard ratios for self-reported history of diagnosis of cataract and self-reported cataract surgery in US radiologic technologists in relation to cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose from occupational exposures (+95% CI).

aRisks are evaluated using a Cox model with age as timescale with stratification by sex and race, and with adjustment to the baseline hazard for diabetes, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (current smoker/ex-smoker/never smoker, numbers of cigarettes/day, age stopped smoking), each ascertained at the baseline survey, and cumulative UVB radiant exposure, ascertained in the course of follow-up. For each endpoint (cataract, cataract extraction) follow-up is restricted to those persons eligible for study (no record of radiotherapy or disease at baseline, unambiguous status at end of follow-up etc) and for cataract surgery the subject had to be free of cataract at the baseline questionnaire (see Methods). The cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose groups used were 0-9, 10-19, 20-49, 50-99, 100-199, 200-499, ≥500 mGy, the first of these used as the reference group (relative risk=1). For cataract surgery the baseline hazard was adjusted by 1years since baseline questionnaire < 5 years, and excess risk was limited to ≥5 years after baseline questionnaire.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved annually by the National Cancer Institute Special Studies Institution Review Board and by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Data sharing

The data and all code used for the analysis are available from the lead author on application.

Contributors

MPL, CMK and MSL conceived and designed the study, and produced an analytical plan. MSL, MMD, BHA, MPL and JSM were responsible for acquisition and processing of data (including questionnaire, mortality, and cancer validation data). SLS, DLP, MMD, JSM, MSL, BHA, MPL and DB were responsible for dose estimation and validation. MPL was responsible for data analysis. MPL, CMK, MSL, DB, NH and CM interpreted the results. MPL produced a first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided intellectual input. MPL, CMK and MSL are guarantors.

Competing interests

All authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Results

There were 12,336 cases of cataract history among 67,246 eligible subjects and 5509 cataract surgeries among 67,709 eligible subjects (Table 1). There were 832,479 and 888,420 person years of follow-up for the groups eligible for the cataract history and cataract surgery analyses, respectively, representing an average of 12.4 and 13.1 years of follow-up per person for cataract history and cataract surgery, respectively. Higher risks of cataract history and cataract surgery were observed among women compared to men, whites compared to blacks or other racial/ethnic groups, among those reporting in the baseline interview a diagnosis of diabetes compared to no diabetes, among those who were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) at baseline compared to those with normal weight, and among those who were current cigarette smokers compared to those who never smoked (heterogeneity p<0.001 in all cases), with progressive increases in risks with increasing smoking quantity (cigarettes/day) and increasing age at stopping smoking (Table 1). There were significantly increased risks with increasing cumulative UVB radiant exposure (treated as a time-varying variable) for cataract history and for cataract surgery, with similar magnitude of increases in risk for both endpoints, with EHR / MJ cm−2 =3.52 (95% CI 0.57, 7.64) (p=0.016) for cataract, =4.86 (95% CI 0.41, 12.45) (p=0.028) for cataract surgery (data not shown). The mean cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose among those eligible for study of cataract history was 55.7 mGy, with interquartile range 23.6–69.0 mGy; for those eligible for study of cataract surgery, the mean cumulative dose was 55.0 mGy, with interquartile range 23.8–68.9 mGy (data not shown).

Table 2 shows the unadjusted risk by cumulative eye-lens absorbed dose group for cataract history and cataract surgery. As can be seen, there was a progressive increase in HR with dose for cataract history, and (to a lesser extent) also for cataract surgery. Table 2 shows that there were 3072 cases of cataract history and 1571 of cataract surgery with cumulative occupational dose ≥100 mGy at baseline.

Table 3 indicates that there was a significant increase in risk of cataract history over the full dose range, with EHR/mGy =0.69 x 10−3 (95% CI 0.27 x 10−3, 1.16 x 10−3, p<0.001), which increases in magnitude with increasingly lower restriction of dose, so that when analysis was restricted to <100 mGy the EHR/mGy =1.16 x 10−3 (95% CI 0.11 x 10−3, 2.31 x 10−3, p=0.030). The exposure-response trend for occupational radiation and increase in cataract surgery was positive, but non-significant over the full (EHR/mGy = 0.34 x 10−3, 95% CI −0.19 x 10−3, 0.97 x 10−3, p=0.221) and restricted dose ranges, although in contrast with cataract history, the trend did not change appreciably with increasingly lower restriction of dose (Table 3). Related to this, both cataract history and cataract surgery exhibited declining excess risks per unit dose with increasing dose, as shown in Figure 1, which was conventionally statistically significant (p=0.015) for cataract history but not for cataract surgery (p>0.5). The degree of reduction in EHR/mGy with increasing dose was generally comparable for the two outcomes. The evidence for change in the magnitude of EHR/mGy with increasing dose became much weaker in models that included modification of radiation risk by attained age (p=0.080), and remained non-significant for cataract surgery (p>0.5) (Appendix D Table D2).

Table 4 demonstrates that risk of cataract history among diabetics was appreciably lower, with an EHR/mGy of −0.95 x 10−3 (95% CI −1.57 x 10−3, 0.03 x 10−3), compared with non-diabetics, with an EHR/mGy of 0.85 x 10−3 (95% CI 0.40 x 10−3, 1.34 x 10−3), a difference which was highly statistically significant (p=0.002). Similar differences were seen in radiation risk of cataract surgery among diabetics and non-diabetics. There were indications at borderline levels of statistical significance (p=0.083) that radiation-related risk of cataract history decreased with increasing attained age. There was little evidence for modification of the cataract or cataract surgery radiation risk by sex, racial group, smoking (overall smoking status, number of cigarettes smoked, age stopped smoking), birth year, BMI or by cumulative UVB radiant exposure (Table 4).

Table 5 does not suggest that there was significant variation of radiation-related risk of cataract history by time since exposure (p=0.323) or age at exposure (p=0.362). Nevertheless, there was progressive reduction in the radiation risk of cataract history with increasing age at exposure; comparing those exposed <30 years old to those exposed at ages 30-49 and to those exposed at ages ≥50, the EHR/mGy declined from 0.91 x 10−3 (95% CI 0.35 x 10−3, 1.53 x 10−3), 0.42 x 10−3 (95% CI −0.40 x 10−3, 1.30 x 10−3) and −0.47 x 10−3 (95% CI −3.20 x 10−3, 2.86 x 10−3), respectively. Likewise, there was some reduction in cataract risk with increasing time since exposure, so that for <10 years after exposure, 10-14 years after exposure and ≥15 years after exposure, the EHR/mGy were 8.71 x 10−3 (95% CI −1.77 x 10−3, 20.34 x 10−3), −0.91 x 10−3 (95% CI −6.81 x 10−3, 5.74 x 10−3) and 0.66 x 10−3 (95% CI 0.23 x 10−3, 1.14 x 10−3), respectively.

Little difference was made to the dose response risk estimate, or to the overall goodness of fit by varying the lagging period between 0 and 10 years (Appendix D Table D1). Nevertheless, there were weak indications, suggested by the minimising point of the −log-likelihood, that a dose lag of 4-5 years was optimal.

Adding back persons with prior radiotherapy recorded on the first two questionnaires, or not censoring individuals at occurrence of cancer other than NMSC, or both, had little effect on the risk of cataract history and cataract surgery risk estimates (Appendix D Table D3). Apart from sex and birth year, selective removal of variables used for stratifying or adjusting the baseline risk also made little difference on the cataract risk (Appendix D Table D4). Sensitivity analysis in which the restriction on absence of cataract at baseline questionnaire, or removing the restriction on the radiogenic excess starting ≥5 years after the baseline questionnaire made little difference to cataract surgery risk (Appendix D Table D5).

Discussion

The cohort of US radiologic technologists prospectively followed for an average of 12-13 years is the first study to identify a significant exposure response of cumulative occupational radiation exposures to the eye lens under 100 mGy and risk of cataracts based on self-reported history. The very large number of technologists with self-reported cataract (12,336) exceeds that in all other radiation-exposed cohorts by more than 3-fold. Based on another novel feature of the study, the availability of information on a broad-based list of known and probable cataract risk factors at baseline, we found that a history of diabetes significantly modified the radiation-cataract relationship, revealing a markedly lower risk of occupational radiation-associated cataracts among technologists with diabetes. We observed modest, albeit non-significant reductions in risk of cataract history with increasing time after exposure and age at occupational radiation exposure. We observed a non-significant exposure response association of cumulative occupational radiation dose with self-reported cataract surgery. The novelty of this occupational study is that, in contrast to many previous studies of cataract (see Table 6), the dose rates are typically low (<5 mGy/hour).

Table 6. Risks for cataract in radiation-exposed cohorts.

| Cohort | Dose (mGy), mean (range) |

Ascertainment | Endpoint | Cases | Excess hazard ratio mGy−1 x 103 or excess odds ratio mGy−1 x 103 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | 56 (0-1514) | Questionnaire | Cataract history | 12,366 | 0.69 (0.27, 1.16) |

| Cataract surgery | 5509 | 0.34 (−0.19, 0.97) | |||

| Swedish skin haemangioma (34) | 400 (0-8400) | LOCS I | Cortical | 111a | 0.50 (0.15, 0.95) |

| Posterior subcapsular | 17a | 0.49 (0.07, 1.08) | |||

| Japanese atomic bomb survivor AHS (39) | 522 (0-4940)b | LOCS II | Cortical | 618c | 0.30 (0.10, 0.53)d |

| Posterior subcapsular | 214c | 0.44 (0.19, 0.73)d | |||

| Nuclear opacity | 415c | 0.07 (−0.11, 0.30)d | |||

| Nuclear colour | 358c | 0.01 (−0.17, 0.24)d | |||

| Japanese atomic bomb survivor AHS cataract surgery (10) | 500 (0-5140)b | Surgical removal | All cataract removal | 1028 | 0.32 (0.17, 0.52)d, e |

| Icelandic airline pilots (36) | NA (0-48) | WHO | Nuclear | 71 | 20 (0, 30) |

| Cortical | 102 | <0 (<0, >0) | |||

| Posterior subcapsular | 32 | <0 (<0, >0) | |||

| Chernobyl recovery worker (12) | NA (0->1095) | Merriam-Focht | Non-nuclear stage 1-5 | 3369a,f / 274g | 0.65 (0.18, 1.30) |

| Posterior subcapsular stage 1 | 2781a,f / 252g | 0.42 (0.01, 1.00) | |||

| Nuclear | 382a,f / 113g | 0.07 (−0.44, 1.04) | |||

| All cataract stage 1-5 | 3751a,f / 384g | 0.70 (0.22, 1.38) | |||

| US Radiologic technologist (19) | 28.1h (0->60.1) | Self-reported incident and removal | All cataract removal | 2382g / 384i | 2.0 (−0.7, 4.7) |

| Finnish interventional radiologists (40) | 60 (10-304) | LOCS II | Cortical or posterior excluding nuclear | 7c | 4 (−20, 28) |

| All opacity (excluding nuclear color) | 15c | 13 (−2, 28) |

Acronyms: AHS = Adult Health Study; LOCS = Lens Opacities Classification System; WHO=World Health Organization

summed over cataracts in left and right eyes.

dose in mSv.

all cases with LOCS II grade I and above.

EOR mSv−1 x 103.

adjusted to persons in Hiroshima, aged 70, exposed at age 20 years.

prevalent cataract.

incident cataract.

median dose.

surgically removed cataract.

In general, the EHR estimates for cataract history given in Table 3 0.69 x 10−3 mGy−1 (95% CI 0.27 x 10−3, 1.16 x 10−3), and for cataract surgery, 0.34 x 10−3 mGy−1 (95% CI −0.19 x 10−3, 0.97 x 10−3), are statistically consistent with those observed in other radiation-exposed groups (see Table 6), in particular, the Japanese atomic bomb survivors (9-11) and the Chernobyl clean-up workers (12). The excess odds ratio (EOR) (which approximates our incidence-based EHR of 0.69 x 10−3 mGy−1 (95% CI 0.27 x 10−3, 1.16 x 10−3)) in those two groups generally lie in the range 0.30-0.70 x 10−3 mGy−1. There is reasonably consistent evidence for excess risk of both posterior subcapsular cataract and cortical cataract incidence associated with radiation exposure. In general, nuclear cataract, which is the dominant type of cataract in adulthood, appears not to be radiation related (17).

In the previous cataract analysis of the USRT cohort, follow-up was considerably shorter (through 2005 vs through 2014 in the current study) and an earlier, less sophisticated version of the dosimetry system was used. In the earlier investigation, age at baseline questionnaire was restricted to 25-44 years, cataract occurrence was restricted to those under 50 years of age, and some high-dose technologists and those who never worked, were excluded, in contrast to the lack of such exclusions in the current study. An elevated risk of cataract that did not attain statistical significance (EHR = 2.0 x 10−3 mGy−1, 95% CI −0.7 x 10−3, 4.7 x 10−3) was observed in the earlier study (19) (Table 6). The dosimetry used in the earlier analysis was not validated in the same way as has been done for the dosimetry employed here (as discussed at greater length below), nor was there any attempt made to assess modifications of radiation risk by major lifestyle, medical and environmental risk factors. This together with the substantially smaller number of cataracts, by at least a factor of 5 compared with the present analysis (n=2,382 in the earlier investigation vs 12,366 in the current study) and by at least a factor of 14 for cataract surgery (n=384 in the earlier investigation vs 5509 in the current study), suggests that the current analysis and findings should supersede the earlier results.

The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) has classified cataract as a tissue reaction (or deterministic) effect (8), with a threshold dose of 500 mGy below which no excess risk would be expected. A linear-threshold model such as implicitly used for tissue-reaction effects by ICRP implies an upwardly curving dose response. The Japanese atomic bomb survivor data showed evidence of a significant (i.e., non-zero) threshold dose of about 500 mGy below which there would be no excess risk, implying some degree of upward curvature in the dose response; however, at distinct variance with this finding, there was no evidence of linear-quadratic curvature in the dose response in the atomic bomb survivors (10). There was also evidence of a significant threshold, at about 300-400 mGy, for various cataract endpoints in a cohort of Chernobyl clean-up workers (12). Again at variance with their findings, using a conventional linear-quadratic model, the authors found little evidence of upward curvature in the cataract dose response as would be expected if a linear-threshold model were valid (12). There are well known methodological problems with fitting of threshold models, discussed elsewhere (17), so that likelihood-based p-values and confidence intervals of the threshold value may be incorrect. The discrepancy between the results of fitting threshold and linear-quadratic models to the Japanese atomic bomb survivor and Chernobyl datasets (10, 12) strongly suggests that this is the case. Although we have not formally tested for a dose threshold given these methodological concerns, we did assess curvature in the dose response, and found some indication of reduction of excess risk with increasing dose (Figure 1). This became much weaker (and no longer statistically significant) when radiation risk was also modified by attained age. Based on our results, a threshold of 500 mGy is inconsistent with the pattern of excess risk (Figure 1, Table 3) in the present cohort.

Our findings that EHR/Gy decreased with increasing time since exposure and age at exposure (albeit not statistically significant) in the current study (Table 5), are in agreement with what has been seen in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors (10) and in the Swedish haemangioma patients (34). The non-significantly larger risks for women than for men contrasts with the reverse direction of effect (at borderline levels of significance, p=0.03)) seen in the atomic bomb survivors,(10) but the marginal significance suggests that not too much should be made of this difference. Diabetes, high BMI, and cigarette smoking are well established risk factors for cataract (4, 10, 12, 19), as also shown here (Table 1), although there was no suggestion that they confounded the radiation dose response in our study (Appendix D Table D4) or other studies in which these were evaluated(10, 12). However, diabetes does strongly modify radiation risk in the USRT, so that those with this condition have much reduced risk of cataract and cataract surgery in contrast with the Japanese atomic bomb survivors (10).

Strengths of the present study include the large population with low (mostly <100 mGy) cumulative protracted radiation doses, large size and prospective cohort design. We utilised a comprehensive occupational dosimetry with estimated absorbed doses specific to the eye lens (discussed at greater length in Appendix B). Although a substantial proportion of the estimated cumulative occupational dose is derived from questionnaires (21), the dosimetry has been subjected to extensive validation, in particular via chromosome aberrations detected using fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) (35). The large number of covariates evaluated and a priori decisions about the data analysis is another strength, with adjustment for several factors that have been associated with cataract, including diabetes, smoking, obesity (via BMI), and solar UVR. The comprehensive work history, demographic, lifestyle and medical factors evaluated facilitated analysis of modifying effects of these variables on the radiation dose response. Another novelty and strength of the present study is the analysis of time-dependent doses accumulated in windows of time since exposure and age at exposure, something that has only rarely been attempted for any health endpoint in relation to radiation or other important exposures.

Despite the large size of the population of medical workers and broad-based assessment of covariates our study had several limitations. All clinical disease outcomes and at least some of the exposure data were ascertained solely by questionnaire and not validated. It might be expected that there would be inter-subject variation (e.g., varying with age and employment status) in the propensity to remember a medical diagnosis of cataract. However, the population of radiologic technologists reported here is medically literate, so that self-reporting of diagnoses for the various ocular endpoints, and medical risk factors such as diabetes should be reasonably reliable. All analyses adjust for age, which is the timescale of the Cox proportional hazards models used here, and which should largely eliminate the major risk factor for propensity to mis-remember diagnostic information. Another weakness is the lack of information on cataract subtype. Of some concern is the discrepancy between the findings for cataract history and cataract surgery, where risks for latter were somewhat lower and generally not significant (Table 3); however, the risks for cataract surgery were statistically consistent with risks for cataract history. We did not have information on other important factors, such as ocular trauma, which is a well-known risk factor for cataract induction (4) and that frequently requires diagnostic radiographs, raising the possibility of confounding by indication, although ocular trauma is relatively rare (36) and thus would not be expected to be frequent enough to materially confound the trend observed here. Another weakness is that, as with many occupational studies, cohort members had to survive to answer the second questionnaire and be free of cataract at that point. However, this degree of selection will not necessarily bias our analysis, since everyone had to survive to answer a questionnaire, and all risk was assessed conditional on that. Follow-up for each endpoint was censored at the date of the last informative questionnaire answered. The plausible assumption was made that censoring was non-informative with respect to the endpoint (cataract history, cataract surgery) being considered.

In summary, the present large occupational study of low dose and low dose-rate radiation exposure found evidence of excess risks of self-reported history of cataract at eye-lens absorbed dose < 100 mGy. The risks for self-reported history of cataract, and their variation with time since exposure and age at exposure, are consistent with those seen in studies of groups exposed to higher doses and dose rates. Elevated risks were observed at doses substantially lower than the threshold of 500 mGy suggested by the ICRP (8), with implications for radiological protection. In particular, our findings, if confirmed, need to be considered as interventional radiologists may receive eye-lens doses well over the 100 mGy value (37, 38). Future studies should assess cataract risk in other radiation-exposed occupational groups with clinically-ascertained diagnosis of cataract by cataract type, medical record validation of cataract surgery, well-validated dosimetry and high-quality data on relevant lifestyle, environmental, and medical risk factors, to determine if our findings that cataract is inducible by very low doses of radiation would be confirmed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the two referees for their detailed and helpful comments. The authors thank the radiologic technologists who participated in the study, Dr Jerry Reid of the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists for continued support, and Diane Kampa and Allison Iwan of the University of Minnesota for study management and data collection.

Funding:

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. CM was supported by a training grant from Midwest Center for Occupational Safety and Health CDC/NIOSH 2T42 OH008434. The views expressed herein by the authors are independent of all funding agencies.

References

- 1.Steinberg EP, Javitt JC, Sharkey PD, et al. The content and cost of cataract surgery. Archives of ophthalmology. 1993;111(8):1041–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Söderberg PG, Talebizadeh N, Yu Z, Galichanin K. Does infrared or ultraviolet light damage the lens? Eye (Lond). 2016;30(2):241–6. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christen WG, Manson JE, Seddon JM, et al. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of cataract in men. JAMA. 1992;268(8):989–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodge WG, Whitcher JP, Satariano W. Risk factors for age-related cataracts. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(2):336–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Floud S, Kuper H, Reeves GK, Beral V, Green J. Risk Factors for Cataracts Treated Surgically in Postmenopausal Women. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(8):1704–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R. Ultraviolet light exposure and lens opacities: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(12):1658–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards AA, Lloyd DC. Risks from ionising radiation: deterministic effects. J.Radiol.Prot 1998;18(3):175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs - threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. ICRP publication 118. Ann. ICRP 2012;41(1-2):1–322. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2012.02.001 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minamoto A, Taniguchi H, Yoshitani N, et al. Cataract in atomic bomb survivors. Int.J.Radiat.Biol 2004;80(5):339–45. doi: 10.1080/09553000410001680332 [doi];3VPTTN6THYAB74EA [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neriishi K, Nakashima E, Akahoshi M, et al. Radiation dose and cataract surgery incidence in atomic bomb survivors, 1986-2005. Radiology. 2012;265(1):167–74. doi:radiol.12111947 [pii]; 10.1148/radiol.12111947 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neriishi K, Nakashima E, Minamoto A, et al. Postoperative cataract cases among atomic bomb survivors: radiation dose response and threshold. Radiat.Res 2007;168(4):404–8. doi:RR0928 [pii]; 10.1667/RR0928.1 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worgul BV, Kundiyev YI, Sergiyenko NM, et al. Cataracts among Chernobyl clean-up workers: implications regarding permissible eye exposures. Radiat.Res 2007;167(2):233–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chylack LT Jr., Peterson LE, Feiveson AH, et al. NASA study of cataract in astronauts (NASCA). Report 1: Cross-sectional study of the relationship of exposure to space radiation and risk of lens opacity. Radiat.Res 2009;172(1):10–20. doi: 10.1667/RR1580.1 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chylack LT Jr., Feiveson AH, Peterson LE, et al. NASCA report 2: Longitudinal study of relationship of exposure to space radiation and risk of lens opacity. Radiat.Res 2012;178(1):25–32. doi: 10.1667/RR2876.1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ainsbury EA, Bouffler SD, Dörr W, et al. Radiation cataractogenesis: a review of recent studies. Radiat.Res 2009;172(1):1–9. doi: 10.1667/RR1688.1 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammer GP, Scheidemann-Wesp U, Samkange-Zeeb F, Wicke H, Neriishi K, Blettner M. Occupational exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation and cataract development: a systematic literature review and perspectives on future studies. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2013;52(3):303–19. doi: 10.1007/s00411-013-0477-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little MP. A review of non-cancer effects, especially circulatory and ocular diseases. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2013;52(4):435–49. doi: 10.1007/s00411-013-0484-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Commission on Radiological Protection. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 103. Ann. ICRP 2007;37(2-4):1–332. doi:S0146-6453(07)00031-0 [pii]; 10.1016/j.icrp.2007.10.003 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chodick G, Bekiroglu N, Hauptmann M, et al. Risk of cataract after exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation: a 20-year prospective cohort study among US radiologic technologists. Am.J.Epidemiol 2008;168(6):620–31. doi:kwn171 [pii]; 10.1093/aje/kwn171 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernier MO, Journy N, Villoing D, et al. Cataract Risk in a Cohort of U.S. Radiologic Technologists Performing Nuclear Medicine Procedures. Radiology. 2018;286(2):592–601. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon SL, Preston DL, Linet MS, et al. Radiation organ doses received in a nationwide cohort of U.S. radiologic technologists: methods and findings. Radiat. Res 2014;182(5):507–28. doi: 10.1667/RR13542.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doody MM, Mandel JS, Lubin JH, Boice JD. Mortality among United States radiologic technologists, 1926-90. Cancer Causes & Control. 1998;9(1):67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigurdson AJ, Doody MM, Rao RS, et al. Cancer incidence in the US radiologic technologists health study, 1983-1998. Cancer. 2003;97(12):3080–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11444 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohan AK, Hauptmann M, Freedman DM, et al. Cancer and other causes of mortality among radiologic technologists in the United States. Int. J. Cancer 2003;103(2):259–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10811 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston DL, Kitahara CM, Freedman DM, et al. Breast cancer risk and protracted low-to-moderate dose occupational radiation exposure in the US Radiologic Technologists Cohort, 1983-2008. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(9):1105–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll RJ, Ruppert D, Stefanski LA, Crainiceanu CM. Measurement error in nonlinear models. A modern perspective. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2006. p. 1–488. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doody MM, Freedman DM, Alexander BH, et al. Breast cancer incidence in U.S. radiologic technologists. Cancer. 2006;106(12):2707–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21876 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon SL. Organ-specific external dose coefficients and protective apron transmission factors for historical dose reconstruction for medical personnel. Health Phys. 2011;101(1):13–27. doi: 10.1097/HP.0b013e318204a60a [doi];00004032-201107000-00002 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linetsky M, Raghavan CT, Johar K, et al. UVA light-excited kynurenines oxidize ascorbate and modify lens proteins through the formation of advanced glycation end products: implications for human lens aging and cataract formation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(24):17111–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sliney DH. Estimating the solar ultraviolet radiation exposure to an intraocular lens implant. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1987;13(3):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J. Royal Statist. Soc. Series B 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Project version 3.4.4. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. version 3.4.4 https://www.r-project.org. 3.4.4 ed. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Risk Sciences International. Epicure version 2.0.1.0. 2.0.1.0 ed. 55 Metcalfe, K1P 6L5, Canada: Risk Sciences International; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall P, Granath F, Lundell M, Olsson K, Holm LE. Lenticular opacities in individuals exposed to ionizing radiation in infancy. Radiat.Res 1999;152(2):190–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little MP, Kwon D, Doi K, et al. Association of chromosome translocation rate with low dose occupational radiation exposures in U.S. radiologic technologists. Radiat. Res 2014;182(1):1–17. doi: 10.1667/RR13413.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rafnsson V, Olafsdottir E, Hrafnkelsson J, Sasaki H, Arnarsson A, Jonasson F. Cosmic radiation increases the risk of nuclear cataract in airline pilots: a population-based case-control study. Arch.Ophthalmol 2005;123(8):1102–5. doi:123/8/1102 [pii]; 10.1001/archopht.123.8.1102 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacob S, Donadille L, Maccia C, et al. Eye lens radiation exposure to interventional cardiologists: a retrospective assessment of cumulative doses. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2013;153(3):282–93. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncs116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Connor U, Walsh C, Gallagher A, et al. Occupational radiation dose to eyes from interventional radiology procedures in light of the new eye lens dose limit from the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1049):20140627. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakashima E, Neriishi K, Minamoto A. A reanalysis of atomic-bomb cataract data, 2000-2002: a threshold analysis. Health Phys. 2006;90(2):154–60. doi:00004032-200602000-00006 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mrena S, Kivela T, Kurttio P, Auvinen A. Lens opacities among physicians occupationally exposed to ionizing radiation--a pilot study in Finland. Scand.J.Work Environ.Health 2011;37(3):237–43. doi:3152 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.