Abstract

Aims: The objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of the combined middle and inferior meatal antrostomy (MIMA) in management of patients with maxillary fungal sinusitis. Material and Methods: Design: retrospective cross sectional study. Setting and subjects: From September 2018 to March 2021, fifty-five patients with non-invasive maxillary fungal sinusitis, who underwent transnasal endoscopic combined MIMA. Methods: The study compared patients’ pre- and post-operative subjective symptoms, including nasal obstruction, discharge, facial pain or pressure, halitosis, anosmia, and other non-specific symptoms. Endoscopic characteristics of recurrent fungal maxillary sinusitis and postoperative complications were also observed. Closure of the IMA site was evaluated at three and six months post-surgery and patients were categorized into three groups based on closure degree. Results: All clinical symptoms, including nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, nasal pruritus, anosmia, halitosis, sneezing, facial pain, ophthalmic and otologic symptoms, were resolved over six months after combined MIMA in majority of cases (94 − 100%). After three and six months, the postoperative endoscopic evaluation revealed recurrent fungal maxillary sinusitis in 1.8% and 5.4% of cases, respectively. Partial stenosis of the inferior antrostomy was observed in 7.2% and 16% of cases, while complete stenosis was noted in 3.6% and 7.2% of cases after three months and six months. Conclusions: The combined MIMA is effective and has better outcomes than the medial meatal antrostomy approach alone without additional operative time.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12070-023-03863-6.

Keywords: Maxillary sinusitis, Fungal infection, Inferior meatal antrostomy, Endoscopic sinus surgery, Nasolacrimal duct

Introduction

Fungal sinusitis pertains to the inflammatory response of the paranasal sinus mucosa, consequent to infection by a fungal pathogen. This condition is categorically distinguished as either invasive or non-invasive, determined by the presence or absence of microscopic evidence indicating fungal tissue invasion. [1, 2]. The non-invasive form is classically further divided into allergic fungal sinusitis and fungus ball [1]. The formation of a fungal concretion, commonly referred to as a fungus ball, stands as the leading etiological factor in non-invasive fungal sinusitis, and such cases most commonly affect the maxillary sinus[3–6]. Fungal maxillary sinusitis (FMS) has already been described for over 20 years. Since then, many cases/ series have been published, contributing to a better understanding of its clinical spectrum, diagnosis, and therapy. Notably, its incidence has increased significantly over the last decade for unclear reasons [7, 8]. Patients can be completely asymptomatic, but most present with non-specific complaints of rhinosinusitis-like symptoms [7]. The emergence and recognition of its characteristic signs and symptoms may be protracted over a span of multiple years, ultimately resulting in a delayed diagnosis.

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) has established itself as the preeminent therapeutic intervention for FMS, yielding outstanding outcomes[9]. The goal of FMS treatment is for all of the fungal debris to be removed entirely and to provide drainage and ventilation of the paranasal sinuses, taking into consideration a key to avoiding a recurrence. To ensure the complete removal of the fungus ball, it is essential to achieve adequate visualization of the sinus. However, the standard endoscopic endonasal middle meatal antrostomy (MMA) frequently offers only a limited field of view, notably the anterior inferior or medial inferior wall of the maxillary sinus. Consequently, the utilization of this therapeutic approach may engender a heightened vulnerability to the persistence of residual fungal debris, thereby augmenting the associated risks[10, 11].

Given this limitation, some previous studies have suggested the need for a combined approach of MMA and inferior meatal antrostomy (IMA) that would yield a superior visualization of the entire maxillary sinus [10, 12–14]. Nonetheless, there is a paucity of literature documenting the outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) employing the integrated approach specifically for the management of fungal ball maxillary sinusitis. The authors aimed, with this study, to analyze the surgical results after ESS using the bi-meatal approach performed in patients with FMS.

Methods

Study Design

A total of fifty-five FMS patients who underwent surgical treatment from September 2018 until March 2021 in the Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery department at Cho Ray hospital were enrolled. All patients were operated on using the combined middle and inferior meatus antrostomy approach. The inclusion criteria were as follows: adult 18 years old or above, treatment adherence, and postoperative follow-up for at least six months. All eligible patients provided informed consent. Preoperative nasal endoscopy and CT scan investigations were collected.

Surgical Techniques

A preoperative CT scan is essential to meticulously analyze anatomy and pathology of paranasal sinus for surgical planning. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia with patients in supine, anti-Trendelenburg position, on a 15°–30° tilted table position.

Xylometazoline-soaked pledgets were put in the nasal cavity, under middle turbinate (MT) and inferior turbinate (IT) turbinate. The axilla of the MT and the lateral nasal wall under IT was infused with lidocaine 2% and 1:100,000 adrenaline. After total uncinectomy, maxillary sinus ostium was identified and opened with angled, cutting, backbiting forceps or a microdebrider. The fungal lesions in maxillary sinus were resected and irrigated using 0 and 30° endoscopes.

Subsequently, an IMA was performed. Initially, the IT was fractured and displaced medially to make room for the endoscope and surgical tool. Care should be taken not to damage inferior opening of the nasolacrimal duct (Hasner’s valve). The lateral nasal wall under IT was cut approximately 0.5 cm in length, perpendicular to the nasal floor, and posterior to the nasolacrimal duct. A mucosal flap was elevated till the end of the IT. A minimal bony window (0.5 × 1 cm) was made laterally to the IT. The IMA was widened anteriorly using backbiting forceps or cutting forceps. A 30-degree endoscope may observe the maxillary sinus space.

After removing residual fungal lesions, the elevated mucosal flap was repositioned towards the maxillary sinus to help the remaining IMA opening.

Outcome Measurements

This study compared subjective symptoms preoperatively and during the third and sixth months postoperatively. The participants were queried regarding symptoms encompassing nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, facial pain or pressure, halitosis, anosmia, and other non-specific symptoms.

Postoperative endoscopic characteristics of recurrent fungal maxillary sinusitis were observed. In addition, complications were monitored and recorded. We conducted a comprehensive assessment of the closure status at the IMA site at both three and six months post-surgery, categorizing patients into three distinct groups based on closure outcomes: complete closure, partial closure, and no closure.

Results

Fifty-five patients who underwent ESS using the combined technique were enrolled from September 2018 until March 2021. There were no instances of participant attrition throughout the 6-month follow-up period. Table Supplemental 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the demographic characteristics of the enrolled patients at the time of study enrollment. The male/female distributions were 22/33, predominantly from 41 to 60 years.

Their preoperative clinical manifestations were summarized in Table Supplemental 2 as follows: more than 80% of patients complained about rhinorrhea, facial pain, and nasal obstruction. All patients (55/55) presented with halitosis, and 12 of 55 had anosmia. In addition, other non-specific symptoms were also recorded, including sneezing, nasal pruritus, and ophthalmologic symptoms. At three months and six months postoperatively, all these symptoms were re-evaluated regarding their presence/absence, severity degree, and frequency. Patients were also asked if they had any additional symptoms. As shown in Table Supplemental 2, the postoperative results indicated that halitosis and anosmia were entirely resolved, and other symptoms showed significant improvement. Nasal pruritus, runny nose, and sneezing remained in the minority of patients.

The recurrence rate was 1.8% (1/55) and 5.4% (3/55) at three and six months postoperatively, respectively. Furthermore, at the 6-month follow-up, the sites had completely closed in 4 (7.2%) and partially closed in 9 (16%), as shown in Table Supplemental 3. Postoperatively, no significant complications were observed, such as synechia, atrophic rhinitis, bleeding, or epiphora.

Discussion

The crucial aspect in the management of fungus ball of the maxillary sinus lies in the complete eradication of fungal debris from the affected sinus, coupled with the restoration of optimal ventilation and drainage. To achieve this goal, it is essential to use an approach that enables adequate visualization of the whole maxillary sinus cavity and provides sufficient working space for instruments. Importantly, no complications should have occurred. However, it is sometimes difficult to manage with endoscopic MMA alone, even when a 70˚ endoscope is used, particularly when the anterior and/or inferior recesses are involved [15]. Inadequate surgical access may contribute to a heightened incidence of residual fungal debris and the potential recurrence of fungal maxillary sinusitis (FMS). Therefore, some authors have advocated a combination of endoscopic MMA and IMA techniques (the so-called “combined approach” or “bi-meatal approach”) to arrive at the complete resection of the fungus ball [10, 12, 13]. Based on the available literature, the integration of middle and inferior antrostomies has been found to be a crucial aspect in a significant majority (over 60%) of endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) procedures for the management of fungal maxillary sinusitis.

The utilization of a combined approach involving the IMA along with the MMA has demonstrated superior efficacy in achieving complete eradication of infectious materials in cases of fungal maxillary sinusitis (FMS) when compared to the use of MMA alone. An earlier study revealed that the frequency of the postoperative residual fungal debris found in the bi-meatal and MMA groups was 9.5% and 29.2%, respectively (p = 0.042) [11]. In terms of the recurrence rates observed in cases of FMS, a retrospective study comparing the long-term outcomes of patients treated with the ‘MMA alone’ versus a combination of ‘MMA and IMA’ demonstrated a notable finding. Specifically, within the group receiving the combined approach, there were no instances of recurrence observed among any of the patients. In contrast, nine (64%) exhibited maxillary mucosal thickening on the postoperative CT scan at three to four months after experiencing endoscopic MMA [10]. Another study also exhibited a similar result with a recurrence rate of 0% (0/38) in the combined approach group [16]. Our study’s recurrence rate was 1.8% (1/55) and 5.4% (3/55) at three and six months postoperatively, respectively. In addition, the bi-meatal approach also provides postoperative benefits. We believe that good postoperative visualization of the maxillary sinus cavity helped better follow-up and early recurrence detection without a CT scan. Recurrence cases could also be efficiently treated through the inferior meatal opening, reducing the necessity for revision surgery for patients (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Fig. 1.

Transnasal endoscopic inferior meatal antrostomy. A bony window was made laterally to the inferior turbinate. The elevated inferior meatal mucosal flap was then repositioned towards the maxillary sinus

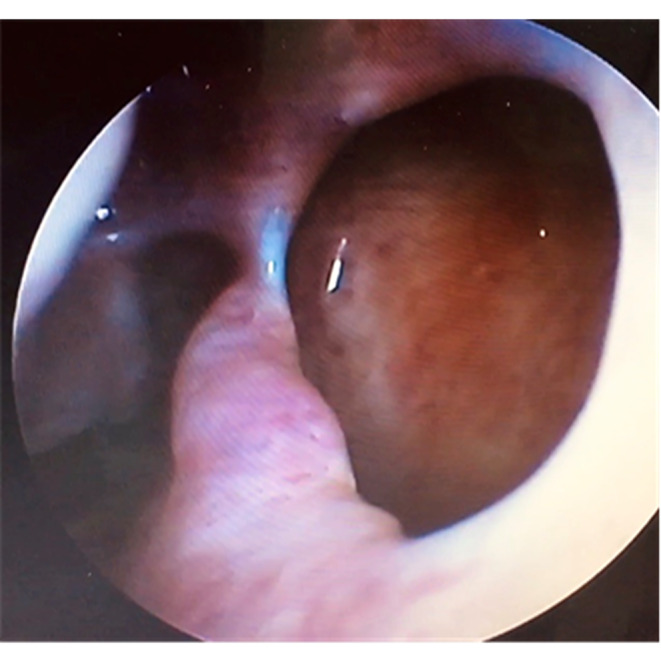

Fig. 2.

Image at 6-month postoperative period. A rigid endoscopic view of inferior meatal antrostomy demonstrates patent access through the left maxillary cavity

In respect of postoperative subjective symptoms, prior to the surgical intervention and following it, the patients were individually queried and subjected to assessments pertaining to a range of symptoms, both prior to and after the operation. Choi et al. [11] demonstrated that the group undergoing the combined approach exhibited a significantly superior subjective symptom score (VAS) one month following the operation. However, the scores did not display a significant difference between the combined approach group and the MMA group at two and three months after the surgery. Notably, this study also demonstrated that the bi-meatal approach dramatically improved VAS scores for facial pain and nasal discharge/postnasal drip. In our study, halitosis and anosmia were wholly resolved after the operation with a combined approach. Other symptoms also showed a significant improvement, only remaining in one to three cases (1.8–5.5%) three to six months during the postoperative follow-up period. Such symptoms, including nasal pruritus, runny nose, and sneezing, might explain allergic rhinitis symptoms in fungal sinusitis patients.

Nonetheless, these manifestations were much more tolerable than preoperative regarding the severity and frequency. Besides, during the postoperative follow-up, patients who complained of excessive nasal discharge and intermittent mild headaches were detected early via inferior meatal endoscopy, which found around 1.8-5.5% of the presence of fungus. We irrigated and thoroughly removed all the infected tissue in the sinus cavity without requiring revision surgery. Such patients were monitored and stabilized after that. Following the surgical procedure, the excised lesions underwent pathological evaluation, and the definitive histopathological findings are visually depicted in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

The image depicts histopathological findings of maxillary sinus aspergillosis in a 55-year-old male patient. The histopathological examination reveals tissue necrosis, excessive inflammation, and microtic tissue containing fungal growth with septate hyphae that are consistent with Aspergillus

As for complications, no major study complications were observed in our and other studies. However, our result showed that the IMA site had utterly closed in 7.2% and partially closed in 16% at six months postoperatively. The rate was relatively similar to another report for which the closure of the IMA window was 10.5% and 23.6% at respective 12 and 36 months postoperatively [16]. Surprisingly, this rate was even higher in another study for which the complete and partial IMA closure was seen in 76% and in 19.0%, respectively, at three months following the operation [11]. These distinct data might be due to antrostomy sizes being different. According to Lund [17], in cases where a sufficiently sized hole (2 × 1 cm) was created, it generally exhibited a tendency to remain open. However, it should be noted that this outcome did not necessarily offer protection to the patient against potential issues. Although the risk of closure of an IMA after the ESS was thought to be greater than that for MMA, this was not a major problem. In our typical approach, we aimed to employ the inferior meatal mucosal flap procedure as a preventive measure against the closure or stenosis of the IMA during antrostomy. Similarly, some studies report this procedure facilitated the high ratio of IMA opening [10, 18, 19]. During the 6-month follow-up, there were no postoperative bleedings or epiphora recorded. Furthermore, Sawatsubashi et al.[10] indicated no significant difference in operating time between the combined approach group and the single MMA approach group.

Conclusion

The combined MIMA is effective and safe in treating fungus maxillary sinusitis. This technique represents a minimally invasive surgical procedure that offers enhanced outcomes while not imposing any additional time requirements. This approach seems superior to the MMA approach alone in both the intraoperative and postoperative settings. Nevertheless, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive long-term follow-up study, encompassing a sizable sample, to substantiate the efficacy of this treatment modality for maxillary sinus fungus ball. Specifically, further investigation is warranted to establish the correlation between the persistence of residual fungal debris and the recurrence of fungal sinusitis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was used in this study.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical committee approved the study proposal.

Informed Consent

Informed Consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chakrabarti A, Denning DW, Ferguson BJ, Ponikau J, Buzina W, Kita H, Marple B, Panda N, Vlaminck S, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1809–1818. doi: 10.1002/lary.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshazo RD. Fungal sinusitis. Am J Med Sci. 1998;316:39–45. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dufour X, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, Ferrie JC, Goujon JM, Rodier MH, Klossek JM. Paranasal sinus fungus ball: epidemiology, clinical features and diagnosis. A retrospective analysis of 173 cases from a single medical center in France, 1989–2002. Med Mycol. 2006;44:61–67. doi: 10.1080/13693780500235728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosjean P, Weber R. Fungus balls of the paranasal sinuses: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:461–470. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pagella F, Matti E, De Bernardi F, Semino L, Cavanna C, Marone P, Farina C, Castelnuovo P. Paranasal sinus fungus ball: diagnosis and management. Mycoses. 2007;50:451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nomura K, Asaka D, Nakayama T, Okushi T, Matsuwaki Y, Yoshimura T, Yoshikawa M, Otori N, Kobayashi T, Moriyama H. Sinus fungus ball in the japanese population: clinical and imaging characteristics of 104 cases. Int J Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:731640. doi: 10.1155/2013/731640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Liu C, Wei H, He S, Dong S, Zhou B, Zhang L, Li Y. A retrospective analysis of 1,717 paranasal sinus fungus ball cases from 2008 to 2017. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:75–79. doi: 10.1002/lary.27869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JS, So SS, Kwon SH. The increasing incidence of paranasal sinus fungus ball: a retrospective cohort study in two hundred forty-five patients for fifteen years. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;42:175–179. doi: 10.1111/coa.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonbay Yılmaz ND, Afyoncu C, Ensari N, Yıldız M, Gür ÖE. The effect of the mother’s participation in therapy on children with vocal fold nodules. Annals of Otology Rhinology & Laryngology. 2021;130:1263–1267. doi: 10.1177/00034894211002430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawatsubashi M, Murakami D, Umezaki T, Komune S. Endonasal endoscopic surgery with combined middle and inferior meatal antrostomies for fungal maxillary sinusitis. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129(Suppl 2):S52–55. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi Y, Kim B-H, Kang S-H, Yu MS. Feasibility of minimal Inferior Meatal Antrostomy and Fiber-Optic Sinus exam for fungal sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33:634–639. doi: 10.1177/1945892419857018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klossek J-M, Serrano E, Péloquin L, Percodani J, Fontanel J-P, Pessey J-J. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery and 109 mycetomas of Paranasal Sinuses. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:112–117. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199701000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dufour X, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, Ferrie JC, Goujon JM, Rodier MH, Karkas A, Klossek JM. Paranasal sinus fungus ball and surgery: a review of 175 cases. Rhinology. 2005;43:34–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albu S, Gocea A, Necula S. Simultaneous inferior and middle meatus antrostomies in the treatment of the severely diseased maxillary sinus. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:e80–e85. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawatsubashi M. Endoscopic Surgical Procedures for Fungal Maxillary Sinusitis: how to do it, a review. Int J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;07:287–297. doi: 10.4236/ijohns.2018.75029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding L, Na g, Lou Z. Extended middle meatal antrostomy via antidromic extended medial wall for the treatment of fungal maxillary sinusitis. BMC Surg. 2022;22:287. doi: 10.1186/s12893-022-01739-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund VJ. Inferior meatal antrostomy. Fundamental considerations of design and function. J Laryngol Otol Suppl. 1988;15:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100600348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tani A, Tada Y, Miura T, Suzuki T, Nomoto M, Saijo H, Ono M, Ogawa H, Omori K. Surgical Approach for Maxillary Fungal Sinusitis. Nihon Bika Gakkai Kaishi (Japanese Journal of Rhinology) 2011;50:26–30. doi: 10.7248/jjrhi.50.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki M, Matsumoto T, Yokota M, Toyoda K, Nakamura Y. Transnasal inferior meatal antrostomy with a mucosal flap for post-caldwell-luc mucoceles in the maxillary sinus. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133:674–677. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.