Abstract

This study aimed to compare the results of injection triamcinolone and hyaluronidase combination with injection Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) in management of Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSMF). Present study was carried out in randomly divided two groups of 30 patients each of OSMF who all are presented with chief complain of reduced mouth opening. Group A patients were given 1 ml of injection triamcinolone and hyaluronidase combination. Group B patients received 1 ml of injection Platelet Rich Plasma. Both injections were given intralesionally once a week for 6 weeks. Results of ANOVA shows significant better results in improving mouth opening in group B patients receiving injection Platelet Rich Plasma as a treatment. In Group A, patients shows improvement in Maximum interincisal distance (MIID) of mean 6.51 ± 1.02 mm as compared to the patients in group B shows improvement in MIID of mean 9.53 ± 1.06 mm (p value < 0.05). Treatment of OSMF with injection Platelet Rich Plasma is a novel method and found to be more efficient than treatment with injection triamcinolone and hyaluronidase combination.

Keywords: Oral submucous fibrosis, PRP, Triamcinolone, Hyaluronidase, Mouth opening, Areca nut

Introduction

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic, insidious, debilitating, potentially malignant condition mainly involving the oral cavity presenting with progressive inability to open mouth, burning sensation while eating, vesicles formation and fibrotic bands. It is a pathological fibrosis with excessive deposition of collagen in the submucosa, juxta-epithelial inflammation, and epithelial atrophy with hyaline degeneration of muscles [1–4]. There is also a potential risk of malignant transformation [2]. All this is a result of deranged collagen metabolism [5]. Recent studies have implicated the role of hypoxia and angiogenesis in the progression of fibrosis in OSMF [6].

OSMF is common in Indian subcontinents due to widespread use of areca nut, a group I carcinogen. Numerous studies have proven that the constituents of areca nut especially alkaloids (arecoline, arecaidine), polyphenols (mainly flavonoids) and minerals (most abundant—copper) are in the centre of pathogenesis of OSMF. Tobacco, chillies, nutritional deficiency, genetics, auto-immunity, plasma fibrinogen degradation products are other contributory factors [7–12]. The habit and the trend of consuming areca nut is also significant in development of OSMF [13]. The prevalence has increased up to 6.4% in India in last four decades [14]. Commonly seen in young to middle age groups, but can occur at any age [15]. The rate of malignant transformation is around 9%. [16–18]

Due to its stubborn nature the management of OSMF is very challenging [19]. In the lack of absolute and complete response to treatment, the focus is to reduce the associated morbidity and risk of malignant transformation. Management includes preventive as well as corrective measures. Most patients are treated medically in combination with oral physiotherapy [12, 20, 22]. Surgical treatment is preferred only in extensive cases [23]. Corticosteroids are among the most effective treatment options available for OSMF. It inhibits the inflammatory process and thereby reducing the fibrosis. Hydrocortisone, Dexamethasone and triamcinolone diacetate are used for intra-lesion injections [24, 25]. When combined with hyaluronidase they give better results as hyaluronidase helps in better penetration of steroids. Hyaluronidase degrades the hyaluronic acid matrix thus reducing the viscosity of intercellular cementing layer and reduces the amount of deposited collagen [26]. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) is recently gaining popularity as treatment in various oral conditions because of its repair and regenerative properties [27, 28]. Platelet rich plasma is the processed liquid fraction of autologous peripheral blood with a higher platelet concentration above the baseline along with various other growth factors and cytokines like TGF(α-β), PDGF, VEGF, EGF, PF4, SDF-1α, CTGF etc [29]. PRP when injected in oral submucosa initiates the healing process in the chronic injury site and causes tissue remodelling [30].

Materials and Methods

A prospective randomized case control trial study has been carried out in the department of ENT, NSCB medical college Jabalpur. Prior informed written consent has been taken from all individual patient. Total of 60 cases have been selected from in and out patients of the department, with the history of reduced mouth opening and burning sensation in mouth and divided in two groups of 30 cases each. Appropriate univariate and bivariate analysis and ANOVA for comparing more than two means will be carried out and use of Student’s t-test and χ2 test for categorical data will be applied to check the hypothesis according to the type of data i.e. continuous and categorical. All means are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and the proportion as in percentage (%). The critical value for the significance of the results will be considered at 0.05 level.

Reduced mouth opening of the patients is measured in terms of Maximum Interincisal Distance (MIID) and accordingly patient’s OSMF functional grading is done as per Moore et al. (2012) [31] and Passi et al. (2017) [32]. Improvement in fibrous band and vesicles formation is noted post treatment in the patients. Burning sensation in the patients were measured and quantified using visual analogue scale both pre-treatment and post treatment.

Group A received 1 ml of combined injection triamcinolone and hyaluronidase and Group B received 1 ml injection PRP as a treatment. Both injections are intralesionally injected in the sub mucosal plane, into the retro-molar trigone and in the fibrous band along the soft palate on multiple sites, weekly for 6 weeks. PRP was made with patients own blood in the same sitting using double spin technique.

Inclusion Criteria

The patients included in the study were of either gender, of any age, with a clinical diagnosis of OSMF, having restricted mouth opening along with associated symptoms like burning sensation while eating spicy food, presence of palpable fibrous bands in any sites of oral cavity and/or recurrent vesicle formation in the oral cavity.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who have undergone any other treatment for OSMF.

Patients with TM joint disorder or trauma to it.

Patient having allergy to local drugs.

Patients with clinical signs and symptoms or proven report of malignancy of oral cavity.

A network meta-analysis including this study was also performed, and the interventions were ranked according to their efficacy based on the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA ranking) with respect to the mouth opening in the OSMF patients post treatment.

Results

The study was done in two groups of 30 patients each divided randomly. Preponderance of males in seen in both the groups with 83.3% (25) in group A & 80% (24) in group B. In our study patients in each group are categorised age wise in 4 groups with 15(50%) patients on 20—30 year age group, 13(43.3%) patients in 30–40 age group, 2(6.7%) patients in 40–50 age group in group A patients. Group B has 13(43.3%) patients in 20–30 years age group, 13(43.3%) patients in 30–40 years age group, 3(10%) patients in 40–50 years and 1(3.3%) patient in 50–60 years of age group. This shows that majority of the patients are in 3rd and 4th decade of life. Most of the patients are coming from the rural background with 80% (24 patients) and 20% (6 patients) from urban area in each group in my study.

Every patient had history of consuming areca nut either in pure form or with tobacco. In group A 24(80%) patients consumed areca nut in pure form and 6(20%) patients in combination with tobacco. In group B 21(70%) patients consumed areca nut in pure form and 9(30%) patients in combination of tobacco. In my study most of the patients have frequency chewing of 5–10 packets of areca nut per day (46% in group A and 53% in group B). 90% of the patients with this frequency presented with grade III OSMF. In our study most of the patients in both groups have chewing frequency of 5–10 min with 90.5% in patients with grade III OSMF.

All the patients (100%) presented with the chief symptom of reduced mouth opening. In group A mean presenting mouth opening was 17.98 mm and in group B mean presenting mouth opening was 19.03 mm. Patients were categorised into various grades on the basis of mouth opening in both groups. In our study burning sensation in the oral cavity is present in all the patients of both groups A and B (100%). Palpable fibrous bands are present in 23 patients (76.7%) in group A and 21 patients (70%) in group B. Vesicle formations are seen in 20 (66.7%) patients in group A and 27 (90%) patients in group B. Pain while opening mouth is present in 13 patients (43.3%) in group A and 25 patients in group B (83%). All the four associated symptoms are more common in grade III OSMF with palpable fibrous bands being the most common symptoms (75%) in grade III patients. Group A and group B in our study has soft palate as the most common subsite involved in the OSMF with frequency of 100%. Buccal mucosa is involved in 6(20%) group A and 18(60%) group B patients. Faucial pillars are involved in 25(83.3%) each in Group A and Group B patients. Retromolar trigone are involved in 29(96.7%) each in Group A and Group B patients. Gingiva-buccal sulcus are involved in 13.3%) patients in Group A and 2(6.7%) patients in Group B patients. Lip mucosa are involved in 4(14.3%) group A patients and 3(10%) Group B patients.

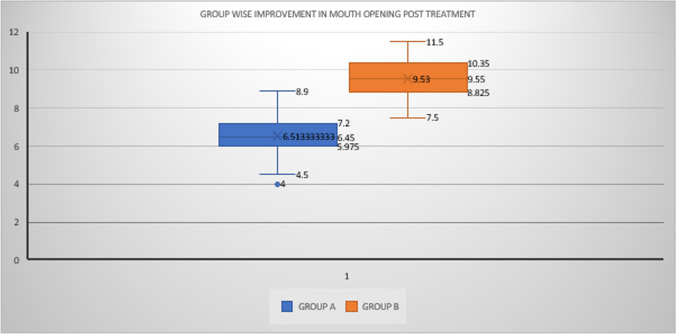

In our study all the patients show improvement in mouth opening post treatment. Most patients have shown improvement in associated symptoms also. In Group A patients shows improvement in Maximum interincisal distance (MIID) of mean 6.51 ± 1.02 mm as compared to the patients in group B shows improvement in MIID of mean 9.53 ± 1.06 mm which is significant as p < 0.05. This shows injection PRP is much better in management of OSMF as far as mouth opening is considered (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of post treatment mouth opening in group A and group B

The main associated symptoms of burning sensation in terms of visual analogue scale markings also shows improvement in both groups post treatment. Post treatment both group A and B shows almost similar improvement in burning sensation with a mean of 4.86 ± 0.16 and 4.53 ± 0.15 respectively (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2a,b). There is also visible improvement in fibrous bands resolution and decreased vesicles formation in both groups though it is very difficult to quantify the improvement and compare it.

Fig. 2.

a—comparative chart of pre and post treatment burning sensation along with improvement in group A per patient. b—comparative chart of pre and post treatment burning sensation along with improvement in group B per patient

In the present study, group A patients did not complain of any local site reaction at the time of injection. However, in group B every patient had burning sensation for few seconds at the local site while injecting PRP. Prior application of local anaesthesia will reduce the burning sensation at the local site where injection PRP is given making it completely free of any adverse reaction or complication.

In post treatment period, there were no significant local or systemic complain reported by patients of either group except one patient in group A shows slight facial puffiness 1 week post 6th injection of triamcinolone and hyaluronidase combination.

Also, Surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) ranking list Table 1 was made for Comparative Efficacy of Interventions in the Reduction of Mouth Opening as Primary Outcome based on the results of meta-analysis of various treatments for OSMF (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

SUCRA ranking table of interventions used in the management of OSMF (in improving mouth opening)

| Interventions | MD | 95% CI | P value | SUCRA rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRP | 9.53 | [9.13–9.93] | < 0.0001 | 1 |

| HYU + CORT | 4.87 | [4.53–5.20] | < 0.0001 | 2 |

| LYC | 4.82 | [2.70–6.94] | < 0.0001 | 3 |

| CUR | 4.9 | [2.22–7.58] | < 0.0001 | 4 |

| CORT | 2.44 | [− 0.43–5.31] | 0.095 | 5 |

| CUR + PER | 2.81 | [− 0.42–6.04] | 0.088 | 6 |

| LYC + CORT | 6.07 | [2.75–9.38] | < 0.0001 | 7 |

| ANT | 2.16 | [− 1.21–5.53] | 0.21 | 8 |

| HYU + CORT + ANT | 4.54 | [0.65–8.43] | 0.022 | 9 |

| LYC + VIT | 5.45 | [1.30–9.60] | 0.01 | 10 |

| CORT + ANT | 6.54 | [2.30–10.78] | 0.002 | 11 |

| HYU | 5.4 | [0.37–10.43] | 0.035 | 12 |

| LYC + CORT + HYU | 7.07 | [1.82–12.31] | 0.008 | 13 |

| PENT | 6.97 | [1.68–12.26] | 0.01 | 14 |

| ISO | 3.57 | [− 2.89–10.03] | 0.279 | 15 |

PRP Platelet rich plasma; HYU Hyaluronidase; CORT Corticosteroid; LYC Lycopene; ALL Allicin; ANT Antioxidant; CUR Curcumin; ALV Aloe vera; PEP Piperine; PLC Placebo; ISO Isoxsuprine; PENT Pentoxifyl; VIT Vitamin E

Fig. 3.

Forest plot comparing the comparative efficacy of interventions used in the management of OSMF (in improving mouth opening). Abbreviations: PRP—platelet rich plasma; HYU—hyaluronidase; CORT—corticosteroid; LYC—lycopene; ALL—allicin; ANT—antioxidant; CUR—curcumin; ALV—aloe vera; PEP—piperine; PLC—placebo; ISO—isoxsuprine; PENT—pentoxifyl

Discussion

With the widespread use of areca nut there has been increase in prevalence of OSMF to 6.4% in the last four decades [14]. Most of the studies show male preponderance except study conducted by Rajendran R in 1994 shows female predilection [33]. Our study also has 81.6% male. In my study 46.67 and 43.3% patients belongs to 3rd and 4th decade of their life respectively, though it can occur at any age. This is similar to the various previous studies [15]. Study by Khan et al. shows that School-going children are also getting affected by this disease due to their addiction to areca nut [34]. Jain, Saumya in 2019 shows it can also affect the paediatric age group. My study shows that most patients belong to rural area [35].

Proving the direct relation with habit of chewing areca nut in the development of OSMF, all the 60 patients in my study had the habit of chewing areca nut in one form or other. Earlier Chaturvedi (2009) and More (2018) [21] has already established this relation of development of OSMF in the areca nut chewers in their studies. Alkaloids present in the areca nuts are responsible for the development of the OSMF by DNA alkylation and increase of proliferation of fibroblast as shown in study conducted by Shreedevi et al. in 2017. [36]

Parameters like form of areca nut (pure or mixed with tobacco), duration or frequency of chewing areca nut had a significant correlation with the outcome of the severity of the disease in the form of clinical grading. In my study most of the patients have frequency chewing of 5–10 packets of areca nut per day (46% in group A and 53% in group B). 90% of the patients with this frequency presented with grade III OSMF. This result is similar to the study results shown by Kumar S in 2016. With high frequency of chewing areca nut, severity of the OSMF also increases. Chatuvedi VN et al. and Gondivkar SM (2020) et al. in their studies shows the subjects who had the habit of chewing for longer time (i.e., for more than 5 min) develops more severe grade of OSMF [22]. In our study most of the patients in both groups have chewing of 5–10 min with 90.5% in patients in grade III OSMF.

In group A mean presenting mouth opening was 17.98 mm and in group B mean presenting mouth opening was 19.03 mm. Patients were categorised into various grades on the basis of mouth opening. Gupta S, Jawanda MK in their overview article in 2021 shows that apart from the reduced mouth opening, OSMF patients are presented with many associated symptoms like burning sensation in mouth especially while eating, recurrent vesicles formation, pain while opening mouth and palpable fibrous bands [19]. Passi et al. (2017) and More (2018) has categorised patients of OSMF into various clinical and functional grades based on the reduced mouth opening, associated symptoms and subsites involved [21, 32].

All the patients stopped consuming areca nut at the start of treatment and continued treatment without consuming it. Though stopping of consumption will not reverse the disease but it will halt further assault to the oral mucosa. For the management of OSMF, multitude of non-surgical options are available like corticosteroids, lycopene, proteolytic enzymes, colchicine etc. Many studies shave shown the efficacy of steroids alone or in combination of hyaluronidase. It is one of the commonly used treatments nowadays. Steroids are well-known immunosuppressive agents for suppression of fibro-productive inflammation found in OSMF. Steroids, in addition to inhibition of production of phospholipase A2; resulting in reducing the production of prostaglandins and leukotriene, stabilizes lysosomal membranes and prevent the release of proteolytic enzymes as well. Triamcinolone is preferred due to its high potency, duration of action, and decreased systemic absorption [24, 25].

Hyaluronidase degrades the fibrous matrix promoting the lysis of fibrinous coagulum and activating specific plasmatic mechanism. Relief of symptoms like stiffness in oral cavity occurs through softening and diminishing fibrous tissue. Hyaluronidase basically produced by breaking down of hyaluronic acid (the ground substance in connective tissue) which slow down the viscosity of intercellular cement substance [26]. They show better results with respect to trismus and fibrosis (Coman et al. 1947) [37]. Hyaluronidase breaks down hyaluronic acid and lowers the viscosity of intercellular cement substances. It also decreases collagen formation (Laxmipathi 1980) [38]. Steroids work better in combination with hyaluronidase because of better absorption.

Whereas, PRP is most commonly observed to be used beneficially in soft and hard tissue healing (Marx et al. 1998; Anitua, 1999) [39, 40]. PRP is an ample supply of growth factors which play important role in wound healing via clot formation (Marx et al. 1998) [39]. According to research, platelets once activated, it will release the alpha secretory granules at the site of injury (Anitua 1999; Marx 2001; Whitman et al. 1997; Marx 1999) [40, 42]. Addition of thrombin and calcium chloride to PRP observed to be trigger the alpha granules to liberate the active growth factors i.e. platelet-derived growth factor, TGF-b, VEGF, insulin- like growth factor I, epidermal growth factor (EGF), epithelial cell growth factor, and TGF-b1 and TGFb2 (Marx et al. 1998; Marx 2001) [39, 41]. These growth factors will stimulate undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells at the site of wound and excite mitosis in these cells.

Amer Sabih Hydri et al. in 2016 conducted a study on comparison of injection triamcinolone and injection PRP in two groups of 40 patients each receiving one set of treatment. After completion of 6 weeks treatment, his team found that the mean MIID improved in group ‘A’ (who received injection triamcinolone) to 3.08 ± 0.8cms, and in group ‘B’ (who received injection PRP) to 3.22 ± 0.5cms. The mean improvement in MIID in group ‘A’ was 0.783 ± 0.25cms compared to 1.01 ± 0.05 cm in group ‘B’ (p < 0.05), which was significant [43]. In 2019 study conducted by Manjunath K shows that there was significant increase in mouth opening in patients after administration of intra-dermal triamcinolone injection and oral lycopene. The results were statistically significant (p value < 0.001) [44]. Similar results were shown by study of Chloe et al. also in 2004 [45]. Kakar et al. in 1985 reported that patients treated with hyaluronidase showed quicker improvement in symptoms but a combination of corticosteroids gave better results [46]. Leena James et al. in 2015 uses steroids with hyaluronidase injection in her study and found that improvement in the patient’s mouth opening with a net gain of 6 ± 2 mm (92%), the range being 4–8 mm with definite reduction in burning sensation, painful ulceration and blanching of oral mucosa and patient followed up for an average of 9 months. [47] In 2019–20 Dr Naiem Ahmed et al. conducted study with injection hyaluronidase and injection PRP as the management of the OSMF and found that both treatments work significantly (p value < 0.05) to relief the symptoms individually. Though there was no comparison done between them. [48]

With the advancement in knowledge of pathogenesis of OSMF, many treatment options were tried based on their action in various steps of pathogenesis. Previous studies have shown that treatment with colchicine, lycopene, curcumin, hyaluronidase, triamcinolone gave significant results. However, a promising therapy is yet to come so that burden of this disease can be reduced. Studies by Amer Sabih Hydri et al. and Dr Naiem Ahmed et al. along with this study which is conducted in population from central India have shown Injection PRP’s effectiveness at par with other treatment modalities in management of OSMF [43, 48].

In the year 2022, Divya Gopinath et al. performed a network meta-analysis on 32 Randomised Control Trials that compared the efficacy of various interventions for OSMF and according to their efficacy in mouth opening they are ranked based on surface under cumulative ranking. A new SUCRA ranking list made along with results on my study and results of meta-analysis by Divya Gopinath et al. while excluding the trial results of herbal products. Injection PRP made top of this new SUCRA ranking list in my study based on its efficacy in improving mouth opening in OSMF patients [49].

Conclusion

My study conducted for 1 year time period in two groups of 30 patients each shows that novel treatment with injection PRP shows significantly better results in mouth opening in OSMF along with comparable results in associated symptoms of OSMF when compared to the traditional combination of injection triamcinolone and hyaluronidase.

Limitations

Larger sample size is required for more generalisation of the results of this study. Also, long term follow-up is required to see for the sustainability of the treatment results or the side effects.

Future Aspect

Long term follow-up of these treated patients for the incidence of malignancy of oral cavity and thus effectiveness of these treatment in prevention of oral cancer.

Funding

No funding sources.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Babu S, Bhat RV, Kumar PU. A comparative clinicopathological study of oral submucous fibrosis in habitual chewers of pan masala and betel quid. Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:317–322. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.More CB, Rao NR. Proposed clinical definition for oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2019;9:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes MW, Chuong CM. A mouthful of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:7–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta SC, Singh M, Khanna S, Jain S. Oral submucous fibrosis with its possible effect on eustachian tube functions: a tympanometric study. Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56:183–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02974346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajalalitha P, Vali S. Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis-a collagen metabolic disorder. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhari SS, Kulkarni DG, Patankar S, Kheur SM, Sarode SC, Sarode GS, Patil S. Angiogenesis and fibrogenesis in oral submucous fibrosis: a viewpoint. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19(2):242–245. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan S, Chatra L, Prashanth SK, Veena KM, Rao PK. Pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:199–203. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.98970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lord GA, Lim CK, Warnakulasuriya S, Peters TJ. Chemical and analytical aspects of areca nut. Addict Biol. 2002;7:99–102. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez BY, Zhu X, Goodman MT, Gatewood R, Mendiola P, Quinata K, et al. Betel nut chewing, oral premalignant lesions, and the oral microbiome. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathew P, Austin RD, Varghese SS. Estimation and comparison of copper content in raw areca nuts and commercial areca nut products: Implications in increasing prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:247–249. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8042.3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu CJ, Chang ML, Chiang CP, Hahn LJ, Hsieh LL, Chen CJ. Interaction of collagen-related genes and susceptibility to betel quidinduced oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:646–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.More C, Shah P, Rao N, Pawar R. Oral submucous fibrosis: an overview with evidence-based management. Int J Oral Health Sci Adv. 2015;3:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha VK, Kandula S, NingappaChinnannavar S, Rout P, Mishra S, Bajoria AA. Oral submucous fibrosis: correlation of clinical grading to various habit factors. J Int Soc Prevent Communit Dent. 2019;9:363–371. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_92_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das M, Manjunath C, Srivastava A, Malavika J, Ameena MV. Epidemiology of oral submucous fibrosis: a review. Int J Oral Health Med Res. 2017;3:126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eipe N. The chewing of betel quid and oral submucous fibrosis and anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1210–1213. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000146434.36989.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paymaster JC. Cancer of the buccal mucosa; a clinical study of 650 cases in Indian patients. Cancer. 1956;9(3):431–435. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195605/06)9:3<431::aid-cncr2820090302>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsue SS, Wang WC, Chen CH, Lin CC, Chen YK, Lin LM. Malignant transformation in 1458 patients with potentially malignant oral mucosal disorders: a follow-up study based in a Taiwanese hospital. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(1):25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arakeri G, Patil SG, Aljabab AS, Lin KC, Merkx MA, Gao S, et al. Oral submucous fibrosis: an update on pathophysiology of malignant transformation. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(6):413–417. doi: 10.1111/jop.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S, Jawanda MK. Oral submucous fibrosis: An overview of a challenging entity. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:768–777. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_371_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao NR, Villa A, More CB, Jayasinghe RD, Kerr AS, Johnson NW. Oral submucous fibrosis: a contemporary narrative review with a proposed interprofessional approach for an early diagnosis and clinical management. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-0399-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.More C, Peter R, Nishma G, Chen Y, Rao N. Association of Candida species with oral submucous fibrosis and oral leukoplakia: A case control study. Ann Clin Lab Res. 2018;06:248. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Sarode SC, Gondivkar RS, Patil S, Gaikwad RN, Yuwanati M. Clinical efficacy of mouth exercising devices in oral submucous fibrosis: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020;10:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan AD, Tatu RJ, Shenoy NA, Sharma VS. Surgical management of oral submucous fibrosis in an edentulous patient: a procedural challenge. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2010;1(2):161–163. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.79221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta M, Pachauri A, Singh SK, Ahuja R, Singh P, Mishra SSS. Recent advancements in oral submucous fibrosis management: an overview. Bangladesh J Dent Res Educ. 2014;4(2):88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar K, Saraswathi TR, Ranganathan K. Oral submucous fibrosis: a clinico-histopathologic study in Chennai. Ind J Dent Res. 2007;18:90–95. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.33785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laxmipathi G (1980) Hyalase in submucous fibrosis in oral cavity. Jaipur, India, In: 32nd annual conference of the association of otolaryngologists of India

- 27.Amable PR, Carias RB, Teixeira MV, et al. Platelet-rich plasma preparation for regenerative medicine: optimization and quantification of cytokines and growth factors. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:67. doi: 10.1186/scrt218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Gou L, Zhang P, Li H, Qiu S. Platelet-rich plasma and regenerative dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2020;65(2):131–142. doi: 10.1111/adj.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Everts P, Onishi K, Jayaram P, Lana JF, Mautner K. Platelet-rich plasma: new performance understandings and therapeutic considerations in 2020. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(20):7794. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozman P, Bolta Z. Use of platelet growth factors in treating wounds and soft-tissue injuries. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2007;16:156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.More CB, Das S, Patel H, Adalja C, Kamatchi V, Venkatesh R. Proposed clinical classification for oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(3):200–202. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passi D, Bhanot P, Kacker D, Chahal D, Atri M, Panwar Y. Oral submucous fibrosis: newer proposed classification with critical updates in pathogenesis and management strategies. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2017;8:89–94. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_32_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajendran R. Familial occurrence of oral submucous fibrosis: Report of eight families from northern Kerala, south India. Ind J Dent Res. 2004;15:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan AM, Sheth MS, Purohit RR. Effect of areca nut chewing and maximal mouth opening in school going children in Ahmedabad. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2016;37:239–341. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.195734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jain A, Saumya T. Oral submucous fibrosis in paediatric patients: A systematic review and protocol for management. Int J Surg Oncol. 2019;2019:3497136. doi: 10.1155/2019/3497136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shreedevi B, Shaila M, Sreejyothi HK, Gururaj MP. Genotoxic effect of local & commercial areca nut & tobacco products—A review. Int J Health Sci Res. 2017;7:326–331. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coman DR, Mccutcheon MA, Zeidman I. Failure of hyaluronidase to increase in invasiveness of neoplasms. Cancer Res. 1947;7(6):383–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laxmipathi G. (1980) Hyalase in Submucous Fibrosis in Oral Cavity. Jaipur, India, In: 32nd annual conference of the association of otolaryngologists of India

- 39.Marx RE, Carlson ER, Eichstaedt RM, Schimmele SR, Strauss JE, Georgeff KR. Platelet rich plasma: growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85(6):638–646. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anitua E. The use of Plasma Rich Growth Factors(PRGF) in oral surgery. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13:487–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marx RE. Platelet rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10:225–228. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitman DH, Berry RL, Green DM. Platelet gel: an autologous alternative to fibrin glue with applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1294–1299. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hydri AS, et al. Comparison of triamcinolone versus platelet rich plasma injection for improving trismus in oral submucous fibrosis. J Bahria Univ Med Dental College. 2020;10(1):58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manjunath K, Rajaram PC, Saraswathi TR, Sivapathasundharam B, Sabarinath B, Koteeswaran D, Krithika C. Evaluation of oral submucous fibrosis using ultrasonographic technique: a new diagnostic tool. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:530–536. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.90287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ranganathan K, Devi M, Joshua E, Kirankumar K, Saraswathi T. Oral submucous fibrosis: a case-control study in Chennai, South India. J Oral pathol Med: Official Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol. 2004;33:274–277. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kakar PK, Puri RK, Venkatachalam VP. Oral submucous fibrosis—treatment with hyalase. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99(1):57–60. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100096286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James L, Shetty A, Rishi D, Abraham M. Management of oral submucous fibrosis with injection of hyaluronidase and dexamethasone in Grade III Oral Submucous fibrosis: a retrospective study. J Int Oral Health : JIOH. 2015;7:82–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed N, et al. Comparative study between PRP and hyluronidase injection on fibrous site for OSMF. Int J Appl Res. 2020;6:256–259. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gopinath D, Hui LM, Veettil SK, Balakrishnan Nair A, Maharajan MK. Comparative efficacy of interventions for the management of oral submucous fibrosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Pers Med. 2022;12(8):1272. doi: 10.3390/jpm12081272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]