Abstract

Introduction: Effortful swallow with progressive resistance has a potential clinical implication in improving the oro-muscular strength, swallow safety, and efficiency in elderly individuals. But to date, no studies have explored its benefits in training individuals with post-stroke dysphagia. Aim: The present study investigated the long- term effect of effortful swallow with progressive resistance on swallow safety, efficiency and quality of life in persons with dysphagia following stroke. Method: The study consisted of 5 males (mean age: 41.80yrs ± 9.6yrs) diagnosed with dysphagia post-stroke. The participants underwent 20 sessions (5 days/week) of intensive effortful swallow with progressive training spread across four weeks. In the first two weeks, the participants performed 10 × 3 sets of effortful swallows with a 50% of resistance load, which was further increased to 15 × 3 sets with a 70% resistance load. Results: DIGEST-FEES safety and overall swallow quality of life significantly improved post-therapy, whereas DIGEST-FEES efficiency and overall swallow grades showed no significant changes. Inter-rater reliability of DIGEST-FEES revealed substantial agreement between judges. Conclusion: The results are promising as the technique improved swallow safety, and swallow quality of life in persons with dysphagia following stroke.

Keywords: Effortful swallow, Progressive resistance, Post-stroke dysphagia, DIGEST-FEES, Quality of life

Introduction

Safe and efficient swallow is characterized by a sequence of events in the oral, pharyngeal and esophageal structures, governed by the nervous system, that occur in a short span of time. Swallow safety refers to the ability of transferring the bolus from the mouth to the stomach without penetration and/or aspiration into the airway and swallow efficiency refers to the ability of transferring the bolus from the mouth to the stomach without post-swallow pharyngeal residue, either in the valleculae, pyriform sinus and/or laryngeal vestibule [1]. These two processes ensure that any bolus or saliva reaches the stomach without getting pooled anywhere within the specified time.

Any disruption in the sequence of complex neuromuscular events leads to swallowing difficulty, commonly known as ‘Dysphagia’, affecting the swallow safety and efficiency. There could be either a misdirection or a delay in the transit of the bolus or both, that compromises the swallowing function. The delay may be fleeting, lasting only a few seconds, or it may even appear as a fixed delay, such as in the case of food impaction [2]. In most of the disorders, aspiration/penetration and pharyngeal residue are common signs linked with dysphagia, leading to poor quality of life.

Dysphagia is caused by various factors including structural, systemic, psychogenic, and neurological, with the most commonly cited cause being neurogenic (stroke) in origin [3]. Dysphagia following an acute stroke appears quite diverse, impacting anywhere from 3.5 to 65% of patients [4]. The key signs and symptoms of stroke related dysphagia are delayed swallow initiation, anterior spillage, poor bolus formation, multiple swallows, oral residue, decreased laryngeal closure, increased pharyngeal transit time, pharyngeal residue, decreased upper esophageal sphincter opening, reduced hyolaryngeal movement, decreased peristaltic wave and increased esophageal pressure [5]. According to estimates, in the acute period of stroke, pneumonia is the primary cause of death, with aspiration being fatal in up to 20% of people with dysphagia. Hence, detection of silent and audible aspiration/penetration and subsequent adaptive or behavioural Speech Language Pathologist-based treatment measures are deemed essential [6].

Swallowing maneuvers are mainly used to train patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia to enhance the swallowing abilities and to maintain adequate nutrition and hydration. Effortful swallow is one such maneuver that can be used as a compensatory and a strength training exercise to improve swallowing safety and alleviate pharyngeal residue [7]. Effortful swallow maneuver is regarded as a ‘volitional manipulation of the oro-pharyngeal phase of swallowing’ by many authors [8]. In this maneuver, the tongue plays a vital role; it must be pushed firmly against the hard palate in an upward and backward fashion pressing the throat muscles and swallowing as hard as possible [9].

Effortful swallow has been widely incorporated in the clinical setting for the ease of its use and for the multiple benefits it unfolds. The initial studies were on the immediate effect of effortful swallow on different phases of swallowing. Despite its usefulness, some limitations exist while using the effortful swallow program. The studies that examine the effect of effortful swallow indicate that this maneuver by itself does not lead to improvement in swallowing. Rather an effortful swallow, along with progressive resistance, leads to improved swallow abilities, particularly in the elderly [10].

Moreover, according to the principles of motor learning, overloading muscles can lead to increased strength, and providing feedback enables more active participation, thereby improving the desired outcomes. Studies documenting the effectiveness of the effortful swallow with progressive resistance and the provision of biofeedback are limited in the clinical population with dysphagia, particularly in individuals with post-stroke dysphagia. Additionally, to the researchers’ knowledge, there are no clinical trials documenting the therapy efficacy in terms of swallow safety and efficiency using the Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity- Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (DIGEST-FEES) tool and quality of life incorporating the technique mentioned above in post-stroke dysphagia. Therefore, the present study investigated the long-term effect of effortful swallowing with progressive resistance on swallow safety, efficiency, and quality of life in persons with dysphagia following stroke. The objectives include:

To investigate the effect of effortful swallow with progressive resistance training on swallow safety and efficiency score by comparing the pre- and post-treatment changes.

To investigate the effect of effortful swallow with progressive resistance training on swallow quality of life by comparing the pre- and post-treatment changes.

Method

Research Design

The experimental research incorporated a single-group pretest-posttest design.

Participants

The study sample consisted of five male participants aged 33–55 years (mean age: 41.80yrs ± 9.6yrs) with swallowing difficulties post-stroke. A qualified neurologist confirmed the presence of stroke with either CT/MRI. Participants exhibiting mild to moderate swallowing problems, screened using Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS [11]) were included in the current study. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA [12]) was administered to evaluate the cognitive status, and the participants obtaining a score of ≥ 20 were included. The participants also exhibited fair comprehension skills, ascertained using the Western Aphasia Battery [13], with a score of ≥ 5/10 on the auditory verbal comprehension section. None of the participants exhibited any signs of apraxia of speech, based on the apraxic section of WAB. Table 1 highlights the demographic details of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Sl No. | Age in years | Gender | Site of lesion | Stroke onset duration in months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 30 | Male | Acute infarct -Left MCA territory | 2 |

| 2. | 53 | Male | Acute infarct in the upper medullary and para-sagittal portion of the left cerebral hemisphere | 7 |

| 3. | 43 | Male | Acute infarct -Left MCA territory | 2 |

| 4. | 49 | Male | An acute hemorrhagic stroke involving left basal ganglia | 12 |

| 5. | 33 | Male | Large acute hemorrhagic infarct- Left MCA territory, Small early chronic infarct in the left cerebellar and anterior hemipons | 36 |

Procedure

The treatment protocol, purpose, nature, and details were clearly explained to all the participants and caregivers. The study followed the “Ethical Guidelines of Bio-Behavioural Research Involving Human Subjects” [14] and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute. Before the commencement of the training, informed consent was obtained from all the participants, and detailed baseline evaluations were carried out. Baseline measurements included peak anterior lingual strength, swallow safety, efficiency, overall swallow grade, and swallow quality of life. The anterior lingual peak pressure was measured using Iowa Oral Performance Instrument (IOPI), version 2.2. The investigator determined the anterior tongue strength by placing the IOPI bulb longitudinally 10 mm along the hard palate, posterior to the alveolar ridge. Participants were instructed to press the bulb against the hard palate as hard as possible for 3 s. Three trials of isometric tongue strength were elicited, and the highest generated pressure was considered as the maximum isometric tongue pressure/strength (Pmax) measured in Kilopascal (kPa). The mean value of the three trials did not vary by more than 5% (which was used to provide resistance during the training period). The participants were provided 30-sec breaks between the trials.

Standard FEES evaluation protocol proposed by Langmore [15] with a modified diet was used. An expert ENT professional performed the procedure along with the investigator. The steps involved in the assessment included structural evaluation and observation of secretion followed by functional evaluation of swallowing with different bolus consistencies (thin and thick liquid, semi-solid and solid). The swallow safety score was obtained from the Penetration-Aspiration scale (PAS [16]) and the efficiency score was derived from the visuo-perceptual rating of the percentage of maximum pharyngeal residue for overall bolus trials. These ratings were then used to derive the overall swallow impairment score using a weighted matrix (Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity; DIGEST [17]). A higher score indicates severe dysphagia.

Quality of life was assessed using the swallow quality of life tool (SWAL-QOL [18]). It consists of 44 measures spanning ten different quality-of-life domains related to dysphagia. Each item is graded on a 5-point Likert scale, with the patient receiving instructions to rate their quality of life depending on the assessment areas. Each item was equally weighted and added together to obtain an overall score (0-100), with a lower score indicating poor quality of life.

The participants underwent 20 sessions (5days/week) of intensive effortful swallow with progressive training sessions spread across four weeks. They were made to sit upright on a sturdy chair with an armrest, and the following instruction was given “Swallow very hard while squeezing the IOPI bulb with tongue in an upward-backward motion toward the soft palate” [19]. The IOPI bulb was held by the participants in the anterior tongue pressure measurement position. The investigator set the resistance at 50% of the peak lingual pressure measured during the baseline evaluation, after which the participants were instructed to perform the effortful swallow. Participants performed 10 × 3 sets of effortful swallows in the first ten sessions with 50% of external resistance (using IOPI). In the subsequent ten sessions, participants performed 15 × 3 (45 effortful swallows) with 70% external resistance (incorporating the progressive resistance principle of motor learning). A 2 min rest period was provided between the sets. The investigator verified the performance accuracy by direct observation and contraction of the oro-facial structures [9]. In addition, IOPI was used to provide feedback (visual and verbal) and to ascertain the correctness of the effortful swallow regime. Post 20 sessions, all the outcome measurements obtained at baseline were repeated.

Inter-rater reliability in terms of swallow safety and efficiency was performed for 60% (6 samples) of the FEES recordings. The samples were randomly chosen and rated for swallow safety and efficiency and overall swallow grades using DIGEST-FEES by an experienced Speech-Language Pathologist with three years of clinical experience in the field of dysphagia.

Statistical Analysis

The dependent variables of the present study were swallow safety, efficiency, overall swallow impairment score (DIGEST-FEES), and SWAL-QOL. All the variables were analyzed across two timelines, i.e., baseline and 20th session (post-treatment). The obtained scores were tabulated and subjected to suitable statistical methods using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v26.0 for windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Since the study had a small sample size, non-parametric tests were used for further analysis.

Results

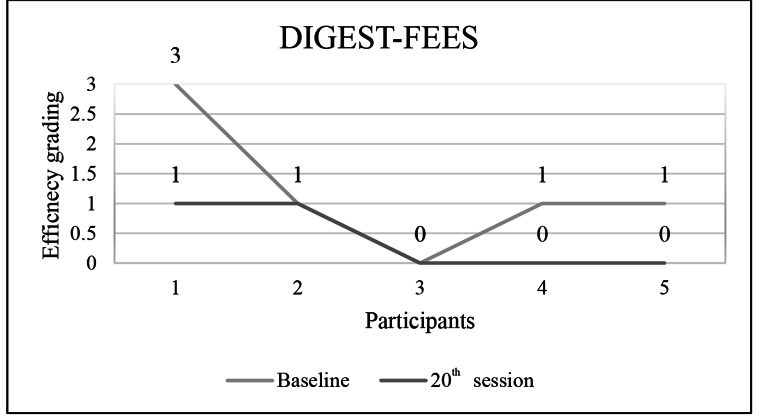

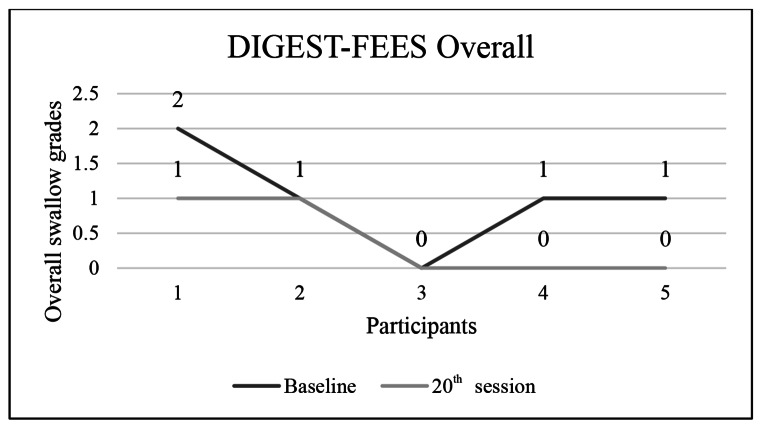

Table 2, presents the median score for outcome measures swallow safety, efficiency and overall grades. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the pre-post therapy difference in the scores of DIGEST-FEES and swallow quality of life (SWAL-QOL). The results of DIGEST-FEES safety revealed a significant improvement post-therapy (/Z/=1.89, p = 0.04), whereas DIGEST-FEES efficiency (/Z/=1.63, p = 0.10) and DIGEST- FEES overall grades (/Z/= 1.73, p = 0.08) did not show significant changes.

Table 2.

Comparison of baselines versus post- treatment scores across DIGEST-FEES scales

| Baseline Median |

20th session Median |

/Z/ | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIGEST-FEES safety | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.89 | 0.04* |

| DIGEST-FEES efficiency | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.63 | 0.10 |

| DIGEST- FEES overall grades | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.73 | 0.08 |

The swallow efficiency and overall scores of DIGEST-FEES for all study participants are shown in the Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

DIGEST-FEES efficiency score across five participants

Fig. 2.

DIGEST-FEES overall swallow grades across five participants

Post-treatment, the average scores across all SWAL-QOL domains increased, with significant improvement in symptom frequency, communication, mental health, and social functioning (Table 3). The study had a positive outcome in terms of the overall score of SWAL-QOL, indicating improved quality of life post-treatment (/Z/=2.02, p = 0.04).

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline versus post-treatment scores across SWAL-QOL domains

| SWAL-QOL Domains | Baseline SWAL-QOL Mean ± SD |

20th Session SWAL-QOL Mean ± SD |

P value baseline vs. 20th session |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating burden | 70 ± 23.45 | 84 ± 16.73 | 0.066 |

| Eating desire and duration | 63.20 ± 31.41 | 87.20 ± 11.09 | 0.068 |

| Symptom frequency | 76.04 ± 4.29 | 92.05 ± 4.03 | 0.043* |

| Food selection | 64 ± 33.61 | 90 ± 14.14 | 0.066 |

| Communication | 26 ± 8.94 | 60 ± 23.45 | 0.038* |

| Fear | 77.80 ± 20.41 | 99 ± 2.23 | 0.080 |

| Mental health | 74 ± 24.08 | 90.40 ± 21.46 | 0.043* |

| Social functioning | 52.80 ± 31.41 | 79 ± 25.20 | 0.039* |

| Fatigue and sleep | 77.60 ± 16.63 | 92 ± 11.31 | 0.068 |

| Overall score | 59.74 ± 14.02 | 77.10 ± 9.95 | 0.043* |

Values are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (SD)

* p < 0.05

Inter-rater reliability was performed for 60% of the FEES recordings. The obtained data were analyzed using Cohen’s Kappa, which revealed substantial agreement (κ = 0.71) between judges.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to investigate the long-term effect of effortful swallow with progressive resistance on swallow safety, efficiency, overall swallow grades and quality of life in individuals with dysphagia following stroke. The results showed significant improvement post-therapy in terms of swallow safety and overall swallow quality of life. The obtained results could be attributed to the positive effect of effortful maneuver in augmenting safe bolus propulsion by lengthened airway closure and, in turn, reduction in the aspiration risk.

An increase in tongue strength is said to generate sufficient high pressure in the oral cavity, which would aid in reducing the oral and pharyngeal transit times. Since swallowing is a series of actions, improved tongue strength is said to positively effect on bolus mastication, pushing bolus toward the pharynx and further facilitating the pharyngeal phase of swallowing [20]. The current training approach that is effortful swallow with progressive resistance has the potential to strengthen the tongue, directly related in enhancing the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing.

The technique facilitates the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, particularly by clearing the vallecular residue, reducing the risk of aspiration and thereby promoting swallow safety and efficiency [19, 21, 22]. Kim [23] found similar results in using the tongue to palate resistance training. The study incorporated 4-week training, which facilitated the participants’ tongue pressure and augmented safe bolus propulsion. Surprisingly, the results of the current study did not reveal significant changes in swallow efficiency and overall swallow grade. The reasons for the same are hereby discussed. Based on Figs. 1 and 2, it can be noted that participant 2 failed to demonstrate improvement in swallow efficiency, resulting in same overall swallow grades obtained during baseline evaluation. As per the baseline assessment, participant 3 reported no explicit impairment in swallow safety and efficiency. Due to the participants’ characteristics (2nd and 3rd participant), and statistically smaller sample sizes, there was no discernible improvement in swallow efficiency and overall swallow grades. It can be inferred that strengthening of pharyngeal muscles requires a longer time frame which could reflect on increase swallow efficiency.

The training protocol also showed positive outcomes regarding overall swallow quality of life in the participants, which is a novel finding of our study. Studies have documented improvement in swallow quality of life by using various techniques in individuals with different conditions [24, 25]. This is the first study of its kind to document the efficacy of effortful swallow with progressive resistance training on quality of life in individuals with dysphagia following stroke. The current study emphasizes the significance of dysphagia therapy using effortful swallow with progressive resistance in individuals with stroke as a means to lessen the severity of the condition and improve the quality of life. It also highlights the importance of documenting the improvement from the patients’ perspectives.

Summary and Conclusions

Considering the paucity of evidence regarding the effectiveness of effortful swallow using progressive resistance in the management of individuals with post-stroke dysphagia, the study was taken up. This is the first study of its kind, which varies the resistance offered along with effortful swallow in post-stroke dysphagia, in line with the principles of motor learning. The study is noteworthy for being the first to employ the DIGEST-FEES tool to track the effectiveness of swallowing therapy and is a step towards providing evidence-based insights into swallowing management in individuals with post-stroke dysphagia. The results were promising in terms of improving the swallow safety and quality of life in individuals with dysphagia following stroke, though no significant changes were noted in swallow efficiency and overall swallow grades. The study had only five individuals with post-stroke dysphagia, which could have led to mixed results. Future research should focus on implementing this technique on a large homogenous sample and explore the outcome variable such as exercise intensity and duration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. M. Pushpavathi, Director, AIISH for granting permission to carry out the study and providing the necessary resources and infrastructure. We would also like to thank the University of Mysuru (UOM) for the constant support. The authors also thank the participants of the current study.

Author Contribution

BC and SN: conceptualizing and designing of the research study, seeking ethical approval, drafting the manuscript in whole or in part. BC and PTK: data collection; BC: analyzing the data: All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There are no funding sources to declare.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Statement of Ethics

Participant/guardians had given their written informed consent. The ethical clearance according to the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, AIISH Ethics committee (AEC), Approval number: No.DOR.9.1/Ph. D/BC/920/2021–2022 dt 10th February, 2023.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rofes L, Arreola V, Almirall J, Cabré M, Campins L, García-Peris P et al (2011) Diagnosis and management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia and its nutritional and respiratory complications in the Elderly. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Abdel Jalil AA, Katzka DA, Castell DO (2015) Approach to the Patient with Dysphagia. Am J Med. Oct 1;128(10) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Broniatowski M, Sonies BC, Rubin JS, Bradshaw CR, Spiegel JR, Bastian RW et al (1999 Apr) Current evaluation and treatment of patients with swallowing Disorders. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 17(4):464–473 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.González-Fernández M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, Christian AB (2013 Sep) Dysphagia after stroke: an overview. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 3(3):187–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Crary M, Dysphagia GM (2016) : Clinical Management in Adults and Children. In: Dysphagia. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- 6.Altman KW (2012) Stepping Stones to Living Well with Dysphagia. Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, vol 72. Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG

- 7.Molfenter SM, Hsu CY, Lu Y, Lazarus CL Alterations to swallowing physiology as the result of Effortful swallowing in healthy seniors. Dysphagia. 2018 Jun 17;33(3):380–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Nekl CG, Lintzenich CR, Leng X, Lever T, Butler SG (2012 Mar) Effects of effortful swallow on esophageal function in healthy adults. Neurogastroentereology & Motility 24(3):252–e108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Park H, Oh D, Yoon T, Park J Effect of effortful swallowing training on tongue strength and oropharyngeal swallowing function in stroke patients with dysphagia: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial.Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2019 May 28;54(3):479–84 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Oh JC Effects of Effortful Swallowing Exercise with Progressive Anterior Tongue Press using Iowa oral performance instrument (IOPI) on the strength of swallowing-related muscles in the Elderly: a preliminary study.Dysphagia. 2021 Feb 10; 37(1):158–67 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Trapl M, Enderle P, Nowotny M, Teuschl Y, Matz K, Dachenhausen A et al (2007 Nov) Dysphagia Bedside Screening for Acute-Stroke Patients. Stroke 38(11):2948–2952 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I et al (1995) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Chengappa & Kumar (2008) Normative & Clinical Data on the Kannada Version of Western Aphasia Battery (WAB-K). Language in India. 2008;8(6)

- 14.Basavaraj V, Venkatesan S. Ethical guidelines for Bio-Behavioural Research Involving human subjects. Mysuru: All India Institute of Speech and Hearing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langmore SE (1998 Dec) State of the Science. Perspectives on swallowing and swallowing Disorders. Dysphagia 7(4):8–10

- 16.Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00417897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starmer HM, Arrese L, Langmore S, Ma Y, Murray J, Patterson J et al (2021) Adaptation and validation of the dynamic imaging Grade of swallowing toxicity for flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing: DIGEST-FEES. Journal of Speech, Language, and hearing Research. 4(6):1802–1810 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.McHorney CA, Martin-Harris B, Robbins J, Rosenbek J Clinical validity of the SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcome tools with respect to Bolus Flow Measures.Dysphagia. 2006 Jul 17;21(3):141–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bülow M, Olsson R, Ekberg O (1999 Spring) Videomanometric analysis of Supraglottic Swallow, Effortful Swallow, and Chin Tuck in healthy volunteers. Dysphagia 14(2):67–72 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Oh JC Effects of Tongue Strength Training and Detraining on Tongue Pressures in healthy adults. Dysphagia. 2015 Jun 17;30(3):315–20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Robbins J, Kays SA, Gangnon RE, Hind JA, Hewitt AL, Gentry LR et al The Effects of Lingual Exercise in Stroke patients with Dysphagia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007 Feb 1; 88(2):150–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Steele CM, Bailey GL, Polacco REC, Hori SF, Molfenter SM, Oshalla M et al (2013) Outcomes of tongue-pressure strength and accuracy training for dysphagia following acquired brain injury. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. Oct 22;15(5):492–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kim HD, Choi JB, Yoo SJ, Chang MY, Lee SW, Park JS Tongue-to-palate resistance training improves tongue strength and oropharyngeal swallowing function in subacute stroke survivors with dysphagia.J Oral Rehabil. 2017 Jan 1; 44(1):59–64 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ayres A, Jotz G, Rieder C, Schuh A, Olchik M (2016 Apr) The impact of Dysphagia Therapy on Quality of Life in patients with Parkinson’s Disease as measured by the swallowing quality of Life Questionnaire (SWALQOL). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 19(03):202–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Zhang M, Tao T, Zhang ZB, Zhu X, Fan WG, Pu LJ et al (2016) Effectiveness of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Patients with Dysphagia with Medullary Infarction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Mar 1;97(3):355–62 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.