Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a disease characterized by localized and generalized proliferation of the histiocytes. It is a locally aggressive condition. The clinical presentation is highly variable and can range from isolated, self-healing skin or bone lesions to life-threatening multisystem disease. It can present as a unifocal or multifocal disease. The majority are present in the head and neck region, but the involvement of Paranasal sinuses is rare. Here we describe a 64-years-old female who presented with a slow-growing left nasal mass for 1 year. Evaluation of the patient was suggestive of malignancy, but the biopsy report turned out to be Langerhans cell histiocytosis; subsequently left, total maxillectomy was done. We hereby present a unique case of LCH with isolated nose and paranasal sinus involvement.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Paranasal sinuses, CD-1A, Nasal obstruction

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a disorder of the dendritic Langerhans cells that lack microscopic evidence of malignancy but progresses aggressively. The previous names of the diseases were eosinophilic granuloma, hand-Christian- Schuler disease, and Letterer-site.

disease. The newer terminology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is because the histiocytes involved in the disease have a structure similar to that of Langerhans cells found in normal mucosa and skin. The distinctive feature in our case is that the patient was an elderly female, and there is an isolated nose and paranasal sinus involvement. Our patient had no lung or skin involvement or any endocrinological disorder. Maxillary sinus involvement is sporadic; to date, only three cases have been reported.

Case Report

A 64-years-old female presented with complaints of left-sided nasal obstruction for 8 months which was insidious in onset and gradually progressive. She had gradually progressive swelling on the left side of the face along with protrusion of the left eyeball for 6 months. She also had a history of dental pain for which a dental procedure was done in the left upper 1st premolar 1 year back, details of which weren’t available. There were no complaints of nasal discharge, epistaxis, anosmia, or headache. There was no history of blurring of vision, diplopia, or history suggestive of intracranial involvement. Nasal endoscopy revealed a friable reddish mass occupying the entire left nasal cavity pushing the septum to the opposite side. Oral cavity examination revealed no loose tooth, ulcers, or palatal bulge. Ophthalmological examination was done, and visual acuity was 6/6 in both eyes with no restriction of extraocular movements. Pupillary reflexes were normal. There was proptosis in the left eye.

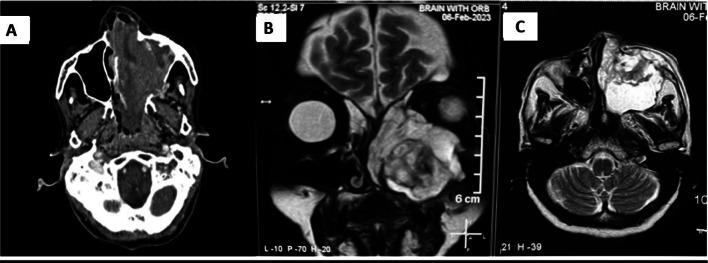

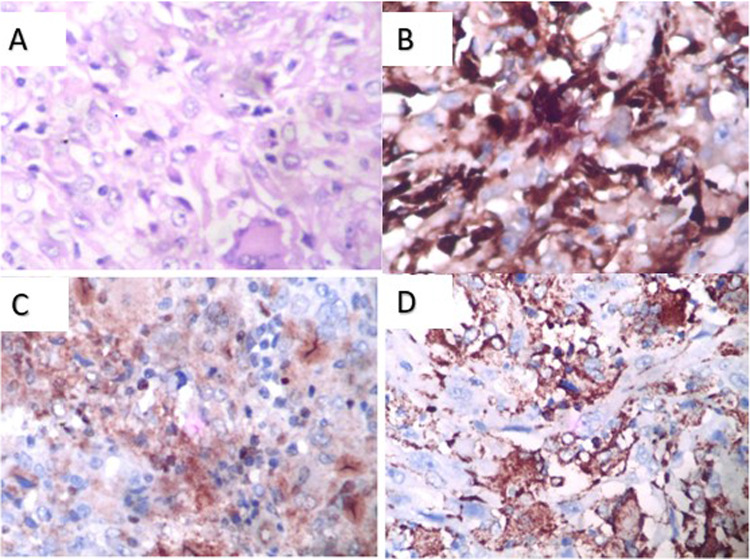

Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI of the nose, paranasal sinus, and orbit (Fig. 1) revealed a heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue density occupying the left maxillary sinus and nasal cavity extending up to the nasopharynx, with erosion of the medial, anterior, and posterior lateral walls of the maxilla (Fig. 2a) with extension into left infratemporal fossa and pterygopalatine fossa. There was involvement of Ethmoid and Sphenoid sinuses. The septum was eroded, and extension into the right nasal cavity was noted. We suspected malignancy and did all the metastatic workup. The patient underwent a biopsy with subsequent histopathological examination revealing a fibrous tissue with cellular infiltrated rich in eosinophils(Fig. 2A), the evaluation of markers revealed positivity for CD-68 (Fig. 2B), CD-1a (Fig. 2C) and S-100 (Fig. 2D) suggestive of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH). To further evaluate the generalized bony involvement, plain radiography of the chest, skull, and limbs was done, and no abnormality was detected. Endocrinological evaluation was normal.

Fig. 1.

Radiological images.

A Contrast CT showing heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue density in left maxillary sinus and left nasal cavity. B MRI T2 weighted image Coronal view showing hyperintense lesion in left maxillary sinus with erosion of roof and medial wall. C MRI T2 weighted image axial view showing lesion eroding anterior and posterolateral wall of maxillary sinus

Fig. 2.

Pathological Images

A H&E image showing fibrous tissue with cellular infiltration rich in eosinophils, B Immunohistological staining showing CD68 positive, C CD1A positive needed for confirmation of LCH, D S-100 positive

The patient underwent left Total Maxillectomy under general anaesthesia by external approach. Tumour from the nasal cavity and other paranasal sinuses was removed in piecemeal using an endoscope and microdebrider till no residual tumour was left. The defect was closed using an interim obturator at the end of the surgery, as the patient was unwilling to undergo surgical reconstruction. The amount of bleeding during the surgery was similar to the maxillectomy done for malignancies. It was controlled by packing and bipolar diathermy.

The patient was discharged on post-operative day 5 and instructions on nasal douching. The post-operative biopsy confirmed LCH. She had complete remission and was followed up for 1 year, and regular nasal endoscopy was done, showing no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

LCH is a rare disease characterized by its unique cell of origin. The median age of onset is from 28 to 39 years of age [1]. Almost 50% of the disease occurs before age 10, whereas 75% of the disease occurs before age 30. When involving adults, the most common organs involved are the lungs, skin, and skeleton; sometimes, they might present with Diabetes Insipidus [2]. The incidence of LCH in adults is 10–15 per million persons per year [3]. Women are more commonly affected than men. However, Linger et al. found that the osseous component of LCH is more in men [4]. Almost 90% of LCH occurs in the head and neck region, but the involvement of the paranasal sinus is very rare [5].

The aetiology of the disease is unknown, but various theories point out that it could be an environmental, infectious, immunologic, or genetic factor involved in disease pathogenesis [1]. The present understanding of LCH is that it is a disease spectrum ranging from unifocal to a more aggressive multifocal disease involving the skin, lung, bone, liver, and lymph nodes. There is no clear theory behind the aetiology and pathogenesis of LCH. However, there is a suggestion that immunological and genetic disturbances can be a cause. The various theories suggested that it might be a response to an unidentified antigen, or it could be an abnormality of the suppressor T-cells. Another line of thought is that it could be a defective interaction between the T-cells and Langerhans cells [6]. Langerhans cells are immature dendritic cells that initiate T cell-dependent aggressive immunological response. Two different types of Langerhans cells have been identified in LCH: Langerhans cells which are the proliferating cells, and macrophages, which are mainly reactive phagocytes. Langerhans cell has antigenic surface markers that react with a specific monoclonal antibody [7, 8].

A characteristic feature of the LCH is the presence of Birbeck granules, whose formation is induced by langerin (CD207), a lectin that is very specific to Langerhans cells [9]. Positive staining of the cells with CD1a or/and Langerin (CD207) is required for definitive diagnosis [10], as in our case where both CD1a and langerin (CD207) were positive. As the monoclonal proliferation of CD1a-positive histiocytes is present in all forms of LCH, it should be helpful as a routine diagnostic procedure for confirmation of LCH [10].

The disease can be unifocal or multifocal. The unifocal disease affects a one-way system at a one-way site and carries the best prognosis, as in our case. In both forms of the disease, the bone is the most commonly affected organ. The frequency of organ system involvement is as follows: bone,80%; skin, 60%; liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, 33%; lungs,25%; orbit, 25%; and maxillofacial, 20% [10]. The most common presenting complaint is localized bone pain. The unifocal disease most commonly presents in the maxillofacial region [9, 10].

LCH can involve any organ system, but the frequency and extent of the disease are age-dependent. The common clinical manifestations of LCH in the jaw are pain and swelling. Mandibular lesions are commonly associated with maxillary involvement but rarely is a maxillary disease seen without mandibular radiolucencies [11], another distinctive feature in our case. Imaging studies include contrast-enhanced computed tomogram, and if facilities permit, a whole-body bone scan is preferable. A biopsy can be done for confirmation of diagnosis [10]. Endocrinological investigations should be done to rule out pituitary involvement. Radiologically, LCH can present as a punched-out lesion with no calcification and no sign of sclerosis or reaction at the borders. Various treatment modalities like surgical excision and curettage have been reported for LCH. Low dose radiotherapy (7-10 Gy) has been reported to be effective in few cases, with its use limited to lesions causing organ dysfunction or are extremely painful and not amenable to other therapies [11]. Chemotherapy has been used described for multisystem LCH and lesions affecting temporal, orbital and vertebral bone which are considered CNS- risk lesions. The most commonly used chemotherapy regimen is vinblastine and prednisolone for 12 months [12]. A recurrence rate of 12% has been reported in the literature for patients managed by surgery [13]. Our case was managed by surgery alone, and the patient has been on follow-up for one year, and there was no evidence of any recurrence.

Conclusion

LCH is a rare disease with a wide range of manifestations like skin, lung, bone, liver, and lymph nodes, predominantly affecting young adults. It can be unifocal or multifocal.

Isolated maxillary lesions are a rare finding as maxillary lesions are commonly associated with the mandibular lesion. Paranasal sinuses involvement further adds to the case’s uniqueness. Thus to conclude a rapidly progressive mass in the nose and paranasal sinus, LCH should be kept as one of the differential diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

Dr Haritha S for helping with patient follow up visits.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

All procedures performed in studies involvinghuman participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of theinstitutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethicalstandards

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the Patient forpublication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yashoda-Devi B, Rakesh N, Agarwal M. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with oral manifestations: a rare and unusual case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;1(4):e252-5. doi: 10.4317/jced.50728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Néel A, Artifoni M, Donadieu J, Lorillon G, Hamidou M, Tazi A. Histiocytose langerhansienne de l’adulte [Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults] Rev Med Int. 2015;36:658–667. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islinger RB, Kuklo TR, Owens BD, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in patients older than 21 years. Clin Orthop. 2000;379:231–235. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200010000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartnick A, Friedrich RE, Roser K, et al. Involvement of the maxillary sinus in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2003;7:36–41. doi: 10.1007/s10006-002-0433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas JA, Janosy G, Cbilosi M, et al. Combined immunological and histochemical analysis of skin and lymph node lesions in histiocytosis X. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:327–337. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mierau GW, Favara BE, Brenman JM. Electron microscopy in histiocytosis X. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1982;3:137–142. doi: 10.3109/01913128209016637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, et al. A novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71–81. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chikwava K, Jaffe R. Langerin (CD207) staining in normal pediatric tissues, reactive lymph nodes, and childhood histiocytic disorders. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:607–614. doi: 10.1007/s10024-004-3027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madrigal-Martínez-Pereda C, Guerrero-Rodríguez V, Guisado-Moya B, Meniz-García C. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: literature review and descriptive analysis of oral manifestations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E222–E228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gramatovici R, D’Angio GJ. Radiation therapy in soft-tissue lesions in histiocytosis X (Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis) Med Pediatr Oncol. 1988;16(4):259–262. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950160407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gadner H, Minkov M, Grois N, et al. Histiocyte society. Therapy prolongation improves outcome in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2013;121(25):5006–5014. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks J, Flaitz CM. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: current insights in a molecular age with emphasis on clinical oral and maxillofacial pathology practice. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:S42–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]