Abstract

Background

Our ability to hear and speak enables us to communicate with others, forming an integral part of our emotional and social well-being. Vocal problems in hearing-impaired patients have yet to be assessed in terms of subjective level of disability they cause. Present study aims to assess the different Voice Handicap Index (VHI) scores among patients with moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss and compare them to those with normal hearing.

Materials and Methods

In this prospective case control study(n = 150), study group A (n = 100) consisted of subjects with bilateral moderate to profound hearing loss on Pure tone audiometry and control group B (n = 50) with normal hearing. Both groups were asked to fill out VHI form after a normal videostroboscopic assessment.

Results

Mean VHI score in group A was 57.5 ± 12.48 and 6.0 ± 3.24 in group B, difference being statistically significant. A strong positive correlation was found between severity of hearing loss and VHI total score. The difference between both groups was also statistically significant for each of the three subscales of VHI.

Conclusion

We infer that subjects with moderate and higher bilateral sensorineural hearing loss hearing have statistically significant higher VHI scores as compared to those with normal hearing. It was observed that perception of voice handicap increased with the severity of hearing loss. These findings emphasize the need for multilateral assessment and treatment of voice disorders in subjects with hearing loss.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Voice, Quality of life, VHI

Introduction

Our ability to hear and speak enables us to communicate with others, and thus,forms an integral part of our emotional and social well-being. Hearing or speech issues that prevent us from communicating can beget substantial problems, such as social isolation. Functional voice dysfunction develops in hearing-impaired subjects due to improper auditory feedback. It is closely related to disrupted contraction and relaxation of antagonistic muscles as well as discordant laryngeal intrinsic and extrinsic muscle coordination. It has been seen that a hearing-impaired child’s phonatory apparatus often exhibits no physical abnormalities throughout the first few years of life. The impairment of the phonatory apparatus is a subsequent consequence of incorrect auditory feedback as well as improper hearing, voice, and speech rehabilitation in infancy or even its termination. [1–3]

Hearing is an important sense that plays a vital role in controlling voice because it provides auditory feedback by receiving verbal output. The moment-to-moment auditory feedback is essential for controlling prosodic speech characteristics such as fundamental frequency, intensity, voice quality, breathing performance, and articulation. Deficits in receiving auditory feedback cause individuals with hearing impairment to have problems in motor control for speech and phonation mechanisms including inability to control voice production, subglottal pressure level, and vowel and consonant production which influence acoustic features of voice and its intelligibility. [4, 5] Thus, individuals with hearing impairment have voice difficulties in varying degrees as well, making it a necessity to conduct research on voice-related quality of life for people with varying degrees of hearing impairment.

As voice problems are more common in people with hearing loss, the important role voice quality plays in communication and the multilateral effects of voice disorders on quality of life, it appears necessary to conduct research on voice-related quality of life for people with hearing loss. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI) questionnaire was created by Jacobson et al. [6] with the purpose of patient self-assessment of the amount of disability caused by voice disorders. VHI is an appropriate tool to study voice disorder from the patient’s perspective and can be used to assess the patient’s judgment about the relative impact of his voice disorder on his quality of life. The term handicap means a social or economic disadvantage incurring from a disability of specific physical loss (voice). It consists of 30 questions divided into three groups according to the situation: functional, physical or emotional. Each group has ten specific situations or questions, identified by their frequency of occurrence through a progressive numeric scale: 0 (never), 1 (almost never), 2 (sometimes), 3 (almost always) and 4 (always). We then obtain individual scoring for each one of the three parameters and total it, the latter varying between 0 and 120. Such scores are directly associated with the level of disability or restriction due to voice.[6].

Numerous authors have validated use of VHI for vocal assessment. VHI was used as a means to measure the voice related handicap in different disease groups, such as organic dysphonia[7], presbyphonia[8], professional use of one’s voice[9, 10], gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD) and laryngopharyngeal reflux disorders[11–13], adduction and abduction spasmodic dysphonia[14–16], thyroplasties[17–19], microsurgery for benign and malignant disorders[20–24], radiography for laryngeal cancer[25], use of tracheoesophageal[26] and speech therapy[27, 28].

Despite substantial research work on voice and speech abnormalities associated with hearing loss, there is dearth of literature on the use of VHI to assess these concerns in individuals with hearing loss. Patients with higher VHI scores may require early improvement of their audiometric thresholds by the use of cochlear implants or individual sound amplification devices. Even in patients with moderate hearing loss, higher scores would suggest the necessity of speech therapy. Such judgements must be taken on a case-by-case basis, demonstrating that VHI would also assist in therapy customization and follow-upfor each individual, enabling a greater probability of treatment success and individual satisfaction. The present study aims to assess the different Voice Handicap Index (VHI) scores among patients with moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss and compare them to those with normal hearing.

Materials and Methods

This prospective case control study was conducted in the department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, SMGSH, Jammu on 150 patients from January 2022 to January 2023 after approval by institutional ethics committee.

Study group A consisted of 100 subjects diagnosed with bilateral moderate to profound hearing loss on Pure tone audiometry. Moderate (41–55 dB), Moderately severe (56–70 dB), Severe (71–90 dB), Profound (> 91 dB)] The exclusion criteria included:. age < 18 or > 60 years, congenital sensorineural hearing loss, speech disorders, professional use of voice, history of laryngeal surgery, hearing aid use at any moment prior to the assessment; smoking habit, pulmonary or neurological disorders.

The control group consisted of 50 subjects who had normal pure-tone and speech audiometry and did not show any history of voice disorder or speech therapy. The two groups were matched in terms of age and gender.

Informed written consent was taken from all the participants before carrying out audiometry, videostroboscopy and VHI. All the subjects were subjected to videostroboscopy to rule out any disease of the larynx. Patients in both groups were asked to fill out VHI form after a normal videostroboscopic assessment. The VHI consists of 30 questions about emotional, physical and functional aspects. Each question is rated from 0 to 4 on a 5-degree scale: never = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3, always = 4. The total score is between 0 and 120.

Data Analysis

The statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 28.0 Statistical Package for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Mann Whitney non-parametric test was utilized in order to compare the numeric variables between the groups (control versus patient). In order to study the correlation among the numeric variables, we used the Spearman correlation test. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean age of presentation was 39.9 ± 12.09 years (n = 100) in group A (study group) with extreme values of 19 and 60 years and the mean age of presentation was 36.6 ± 9.03 years (n = 50) in group B (control), the difference being statistically insignificant. (p = 0.34). Thus, confirming efficiency of the pairing by age range. There was female preponderance in both the groups with male to female ratio in group A being 1:1.3 and in group B 1:1.38 respectively, the difference being statistically insignificant. (p = 0.96, showing similarity in the two groups.)

In Group A, out of 100 subjects, 39 patients had moderately severe hearing loss, 33 patients had moderate hearing loss, 18 patients had severe hearing loss and 10 patients had profound hearing loss. The hearing loss duration at the time of data collection showed a mean of 13 ± 9 years. The hearing loss duration extremes were from 2 to 35 years. The comparison between the groups showed an obvious statistically significant difference (p < 0.0000). The correlation with the other issues analysed within the group of patients with hearing loss did not show statistical significance.

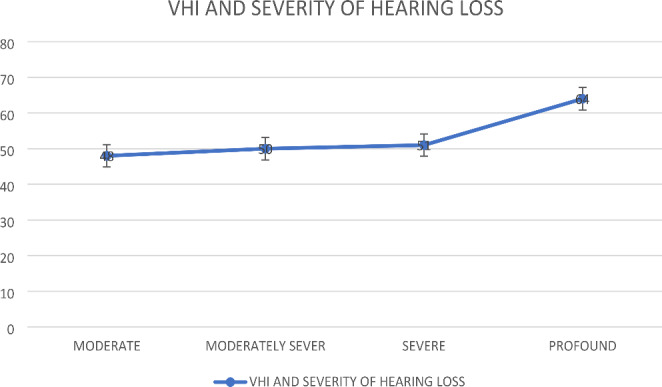

The mean VHI score in group A was 57.5 ± 12.48 and 6.0 ± 3.24 in group B, the difference being statistically significant (p value = 0.0004).The mean VHI score in patients with moderate hearing loss was 48 ± 7.23, 50 ± 5.13 in moderately severe hearing loss patients, 51 ± 8.11 in Severe hearing loss patients, 62.9 ± 6.44 in Profound hearing loss patients, with Spearman rank correlation coefficient = 0.69, indicating strong positive correlation between severity of hearing loss and VHI total score (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

VHI score and Severity Of Hearing Loss

Fig i : .

The mean VHI functional subscale in Group A was 19 ± 4.5 and 2.1 ± 0.67 in group B. The mean VHI physical subscale was 19.0 ± 3.54 in Group A and 2.45 ± 0.64 in group B. The mean VHI emotional subscale in Group A was 23.5 ± 8.24 and 1.6 ± 0.71 in group B. The difference between both groups was statistically significant for each of three subscales of VHI (p value = 0.0001)[Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean VHI Scores in both Groups

| Group | Mean VHI Score[m ± SD] | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL SCORE | Group A (n = 100) | 57.5 ± 12.48 | 0.0004 |

| Group B (n = 50) | 6.0 ± 3.24 | ||

| Functional score | Group A | 19 ± 4.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Group B | 2.1 ± 0.67 | ||

| Physical score | Group A | 19.0 ± 3.54 | < 0.0001 |

| Group B | 2.45 ± 0.64 | ||

| Emotional score | Group A | 23.5 ± 8.24 | < 0.0001 |

| Group B | 1.6 ± 0.71 |

Thus, the results of a comparison made by Mann-Whitney test between the control group and the 3 hearing loss groups showed significant differences between each of the subgroups in the hearing-impaired group and the control group, and between each pairwise comparison among the 3 subgroups in the hearing loss group. Moreover, the results of the Spearman rank correlation analysis demonstrated a significant positive correlation between VHI scores and the severity of hearing loss.

Discussion

The best way to communicate is through speech and speech conveys concepts through voice. Thus, any disorder affecting voice, eventually affects one’s daily life. Normal hearing and normal auditory feedback play an important role in monitoring and controlling aspects of speech such as voice, articulation, verbal fluency and rhythm. In addition, patients with hearing disabilities also experience depression/anxiety, social isolation, decreased wellbeing and subsequent reduced quality of life.

In the present study, the mean age in Group A was 39.9 ± 12.09 years and in Group B it was 36.6 ± 9.03 years (control). These findings were comparable to the studies conducted by Madeira FP et al. [29] and Jotz GP et al. [30] In this study, we included subjects between 20 and 60 years so as to exclude any age-related vocal disorders (physiological vocal change/ presbyphonia).

There was female preponderance in both the groups A and B, with male to female ratio being 1:1.13 and 1:1.14, respectively. A study published by Pribuisiene R et al. [31] showed VHI score data separately for the two genders, with no statistically significant difference in VHI scores between the genders, supporting the current analysis, because the VHI results would not have gender considered as a confounding factor on the questionnaire answers. The predominance of females in the samples tested is consistent with data reported in the literature, allowing for a comparison between this study and earlier revisions.

The data on the effect of hearing loss on voice is limited to the evaluation of people with profound hearing loss in previous studies. By enrolling patients with moderate hearing loss and analysing them as a group, we were able to demonstrate, in a statistically significant way, that voice abnormalities and related complaints can occur in this group of population as well.

The mean VHI score in group A was 57.5 ± 12.48 and 6.0 ± 3.24 in group B, the difference being statistically significant (p value = 0.0001). The difference between both groups was statistically significant for each of three subscales (functional, physical and emotional) of VHI as well. (p value ≤ 0.0001). These findings were in accordance with the studies conducted by Moradi N et al. [32] and Aghadoost O et al. [33]. From our findings, we could state that due to lack of auditory feedback in patients with hearing loss, there is problem in control of voice production, maintenance of subglottic pressure level, and vowel-consonant production which eventually influences the acoustic features of voice and its intelligibility .These findings suggest that patients with hearing loss have much higher levels of voice-related problems than the control group; this could be due to vocal alterations in these patients, as indicated in a prior study by Madeira and Tomita.

The mean VHI score in subjects with moderate hearing loss was 48 ± 7.23, 50 ± 5.13 in moderately severe hearing loss subjects, 51.0 ± 8.11 in Severe hearing loss subjects, 62.5 ± 6.44 in Profound hearing loss subjects, with Spearman rank correlation coefficient = 0.68, indicating strong positive correlation between severity of hearing loss and VHI total score. This finding was consistent with the study conducted by Aghadoost O et al. [33]. Such correlation indicates that voice handicap grows as the severity of hearing loss increases, probably due to deficit in auditory feedback.

The VHI subitems in the hearing loss subjects in this study showed a substantial association, demonstrating that the voice alteration affects these individuals at a variety of levels, including functional, physical, and emotional ones in addition to affective, economic, and other factors. Therefore, we must take into account that the signs of a dysphonic syndrome go beyond hoarseness or voice asthenia, for instance, and also encompass other conditions that have a significant impact on patients’ lives and that are experienced differently by each individual.

Moradi N et al.[ 32] in their study on the relationship between public life quality (SF 36) and voice-related life quality (VHI) in adults with different hearing losses found no significant correlation between the total score and three subtests of VHI (emotional, physical, and functional) and SF36 in individuals with mild hearing loss, but a significant correlation between the total score and two subtests of VHI (physical and functional) except emotional tests and SF36 in individuals with moderate to severe hearing loss. The study emphasized the need for psychosocial rehabilitation along with sound techniques. Therefore, in order to improve patients’ quality of life with regard to their voices, speech and language pathologists must also work to address cognitive-psychosocial aspects. Cohen and Turley [34] reported that elderly individuals with hearing loss were more likely to have voice disorders in different aspects of voice production than those without hearing loss.

Tomblin JB et al. [35] in their study (n = 180) on 5 years old children, found significant increase in speech development in those using hearing Aids (HA). Indicating the impact of hearing loss on voice. The study showed that early provision of hearing aids to children with mild to severe hearing loss was likely to result in better speech and language development, particularly when the child receives good audibility from hearing aids and has had a longer opportunity to wear the hearing aids.

The objective methods of voice analysis, such as the vocal spectrograph, provide valuable insight into severity of the vocal involvement when compared to normal voices, but they are unable to explain why and how patients with similar alterations experience different social and personal impairment. A major development in this area is the VHI questionnaire. Although there may not be significant relationships between these approaches and VHI, this analysis still stands because it takes into account the subjective parameter known as the level of voice disability perception. This fact is also demonstrated and supported by the study by Hsiung MW et al. [36], who failed to demonstrate a correlation between the subjective (VHI) and objective (voice spectrograph) methods.

Conclusion

Through the results obtained in this study, we infer that subjects with moderate and higher bilateral sensorineural hearing loss have statistically significant higher VHI scores when compared with subjects with their hearing within normal ranges. These subjects have greater social and economic disadvantages stemming from the disability or physical impairment specifically associated with the vocal alterations caused by such hearing loss. There was a significant increase in total and subscale VHI scores in subjects with moderate and higher degrees of hearing impairment, indicating that people’s perception of their voice handicap would increase as their hearing loss became more severe. Thus, the effects of voice disabilities on voice related quality of life are multilateral in subjects with hearing loss. The findings emphasize the need for multilateral assessment and treatment of voice disorders in subjects with hearing loss.

Funding

No funding sources.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chouard CH. Changes on the speaking fundamental frequencyafter cochlear implantation. Ann d’Otolaryngologie et de Chirurgie Cervicofac. 1988;105(4):249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirk KI, Hill-Brown C. Speech and language results in children with a cochlear implant. Ear Hear. 1985;6(3):36S–47S. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198505001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkell J, Lane H, Svirsky M, Webster J. Speech of cochlear implant patients: a longitudinal study of vowel production. J Acoust Soc Am. 1992;91(5):2961–2978. doi: 10.1121/1.402932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selleck MA, Sataloff RT. The impact of the auditory system on phonation: a review. J Voice. 2014;28(6):688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Sabeela RA, Azab SN. Can Cochlear Implantation improve Voice in speaking children? Int Arch Commun Disord. 2019;2:010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson BH, Johnson A, Grywalski C, Silbergleit A, Jacobson G, Benninger MS, et al. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6(3):66–70. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360.0603.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouwers F, Dikkers FG. A retrospective study concerning the psychosocial impact of voice disorders: Voice Handicap Index change in patients with benign voice disorders after treatment (measured with the dutch version of the VHI) J Voice. 2009;23(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa HO, Matias C. O impacto da voz na qualidade da vida da mulher idosa. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wingate JM, Brown WS, Shrivastav R, Davenport P, Sapienza CM. Treatment outcomes for professional voice users. J Voice. 2007;21(4):433–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bovo R, Galceran M, Petruccelli J, Hatzopoulos S. Vocal problems among teachers: evaluation of a preventive voice program. J Voice. 2007;21(6):705–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powitzky ES, Khaitan L, Garrett CG, Richards WO, Courey M. Symptoms, quality of life, videolaryngoscopy, and twenty-four-hour tripleprobe pH monitoring in patients with typical and extraesophageal reflux. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(10):859–865. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pribuisiene R, Uloza V, Kupcinskas L, Jonaitis L. Perceptual and acoustic characteristics of voice changes in reflux laryngitis patients. J Voice. 2006;20(1):128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siupsinskiene N, Adamonis K, Toohill RJ. Quality of life in laryngopharyngeal reflux patients. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(3):480–484. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802d83cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wingate JM, Ruddy BH, Lundy DS, Lehman J, Casiano R, Collins SP, et al. Voice Handicap Index results for older patients with adductor spasmodic dysphonia. J Voice. 2005;19(1):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anari S, Carding PN, Hawthorne MR, Deakin J, Drinnan MJ. Nonpharmacologic effects of botulinum toxin on the life quality of patients with spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(10):1888–1892. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180de4d63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuji DH, Chrispim FS, Imamura R, Sennes LU, Hachiya A. Impacto na qualidade vocal da miectomia parcial e neurectomia endoscópica do músculo tireoaritenoideo em paciente com disfonia espasmódica de adução. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72(2):261–266. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spector BC, Netterville JL, Billante C, Clary J, Reinisch L, Smith TL. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(3):176–182. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.117714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uloza V, Pribuisiene R, Saferis V. Multidimensional assessment of functional outcomes of medialization thyroplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(8):616–621. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0755-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearl AW, Woo P, Ostrowski R, Mojica J, Mandell DL, Costantino P. A preliminary report on micronized AlloDerm injection laryngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(6):990–996. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johns MM, Garrett CG, Hwang J, Ossoff RH, Courey MS. Quality-of-life outcomes following laryngeal endoscopic surgery for non-neoplastic vocal fold lesions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113(8):597–601. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behrman A, Sulica L, He T. Factors predicting patient perception of dysphonia caused by benign vocal fold lesions. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(10):1693–1700. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brøndbo K, Benninger MS. Laser resection of T1a glottic carcinomas: results and postoperative voice quality. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124(8):976–979. doi: 10.1080/00016480410017413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peeters AJ, van Gogh CD, Goor KM, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Langendijk JA, Mahieu HF. Health status and voice outcome after treatment for T1a glottic carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261(10):534–540. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0697-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loughran S, Calder N, MacGregor FB, Carding P, MacKenzie K. Quality of life and voice following endoscopic resection or radiotherapy for early glottic cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2005;30(1):42–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meleca RJ, Dworkin JP, Kewson DT, Stachler RJ, Hill SL. Functional outcomes following nonsurgical treatment for advanced-stage laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(4):720–728. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200304000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuster M, Lohscheller J, Hoppe U, Kummer P, Eysholdt U, Rosanowski F. Voice handicap of laryngectomees with tracheoesophageal speech. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2004;56(1):62–67. doi: 10.1159/000075329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schindler A, Bottero A, Capaccio P, Ginocchio D, Adorni F, Ottaviani F. Vocal improvement after voice therapy in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. J Voice. 2008;22(1):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Timmermans B, De Bodt MS, Wuyts FL, Van de Heyning PH. Analysis and evaluation of a voice-training program in future professional voice users. J Voice. 2005;19(2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madeira FB, Tomita S. Voice handicap index evaluation in patients with moderate to profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(1):59–70. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jotz GP, Machado CB, Chacur R, Dornelles S, Gigante LP. Acurácia do VHI na diferenciação do paciente disfônico do não disfônico. Arq Int Otorrinolaringol. 2004;8(3):188–192. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pribuisiene R, Uloza V, Saferis V. Multidimensional voice analysis of reflux laryngitis patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(1):35–40. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moradi N, Rahimifar P, Aghadoost S, Soltani M, Saki, Nader Far, Ehsan.The Relationship between Public Life Quality and the Voice Handicap Index (VHI) in adults with different hearing losses. Pajouhan Sci J. 2019;17:1–6. doi: 10.21859/psj.17.2.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aghadoost O, Moradi N, Dabirmoghaddam P, Aghadoost A, Naderifar E, Dehbokri SM. Voice Handicap Index in Persian speakers with various severities of hearing loss. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2016;68(5):211–215. doi: 10.1159/000455230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen SM, Turley R. Coprevalence and impact of dysphonia and hearing loss in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1870–1873. doi: 10.1002/lary.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomblin JB, Oleson JJ, Ambrose SE, Walker E, Moeller MP (2014 May) The influence of hearing aids on the speech and language development of children with hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 140(5):403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Hsiung MW, Pai L, Wang HW. Correlation between voice handicap index and voice laboratory measurements in dysphonic patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259(2):97–99. doi: 10.1007/s004050100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]