Abstract

Background

Although nurses are expected to address the social determinants of health (SDH) in clinical settings, the perspectives of front‐line nurses on the integration of SDH into their clinical practice remain unclear. Understanding the dynamism of this integration and its outcomes can yield crucial insights into effective nursing care. This study aims to elucidate the integration and adoption of tool‐based SDH assessment nursing programs and their impacts on daily nursing care.

Methods

We conducted qualitative research at a small community‐based hospital in Japan, where a tool‐based program characterized by social background interviews and documentation was implemented. Nurses at the hospital were recruited via purposive and snowball sampling. After hypothesis generation, semi‐constructed in‐depth online interviews were conducted. Each interview lasted between 30 and 50 min. The data were analyzed via thematic analysis using the framework approach.

Results

A total of 16 nurses participated. Participants' incorporation of the novel SDH assessment program was bolstered by prior learning and their recognition of its practical value. Institutional support and collaborative teamwork further facilitated the adoption of this innovation. Enhanced knowledge about the social contexts of their patients contributed to increased respect, empathy, and self‐affirmation among participants, consequently enhancing the quality of nursing care.

Conclusion

Through team‐based learning, reflection, and support, nurses can integrate a tool‐based SDH assessment program into their daily nursing practice. This program has the potential to empower nurses to deliver more holistic care and redefine their professional identity. Further research is warranted to assess patient‐reported outcomes.

Keywords: hospital general medicine, medical communication, medical education, nursing care, qualitative research, social determinants of health

The nurses at a small community hospital successfully incorporated a tool‐based assessment program for SDH into their daily nursing practice. The SDH assessment tool facilitated a more comprehensive understanding of patients' social contexts, resulting in improved patient care.

1. INTRODUCTION

With a mounting comprehension among healthcare professionals regarding the substantial influence of social determinants on the health and well‐being of their patients, 1 healthcare institutions are urged to take into consideration and tackle the social backgrounds of their patients. Many have implemented a screening procedure for assessing patients' social needs within their care environment. 1 A growing number of healthcare organizations have gathered data on patients' social backgrounds through a standardized approach. 2 A variety of tools for inquiring about patients' social needs have been published, 1 , 2 and have been shown to effectively identify patients' social challenges 3 , 4 and to foster a greater sense of urgency among healthcare professionals to take proactive measures. 5

Nurses have an indispensable role in addressing patients' social needs and can mitigate the impact of social and health inequities through effective coordination and implementation of care. 6 They also have the potential to promote social justice through advocacy and research. 7 As such, nurses are expected to tackle the social determinants of health (SDH) in clinical settings. 8 , 9 Despite the importance of nursing education initiatives focused on SDH, 10 , 11 undergraduate curricula that explicitly teach about SDH are currently lacking. 12

Although elevating nurses' capability to address SDH in clinical settings is an immediate priority, research outlining the perspectives of front‐line nurses on integrating SDH into their clinical practice is limited. 13 Intervening in a patient's social background is a complex process that extends beyond mere screening. 14 Understanding the experiences of nurses in addressing SDH in clinical settings is beneficial for both medical professionals and patients.

This study aims to shed light on the integration and adoption of a tool‐based program, utilizing systematic interviewing and assessment of patients' social backgrounds, by nurses and its resulting impacts on patient care.

2. METHODS

2.1. Setting

This study was conducted at a small community‐based hospital in an urban city in Japan. Japan has a relatively large number of hospitals, with outpatient clinics in smaller hospitals serving as primary care centers. 15 Furthermore, hospital stays in Japan tend to be prolonged, 15 with the wards partially functioning as spaces for addressing patients' social challenges. As such, nurses working in small hospitals in Japan are confronted with the imperative to manage patients' social contexts, making this setting an ideal location for the study.

The subject hospital comprises eight ambulatory departments (internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, surgery, orthopedics, and occupational health) and three inpatient wards (with a total of 105 beds). The wards are designated for acute care, community‐based care, and convalescent/rehabilitation care and facilitate patients' return to their community life according to the community‐based integrated care system.

Historically, the hospital serves a population of socially marginalized individuals and encounters many patients with complex psychosocial issues. To secure access to healthcare, the hospital has implemented various initiatives, including the Free/Low‐Cost Medical Care Program 16 and the Hospitalization Assistance Policy for Delivery. 17 Inpatient and outpatient nursing staff have been practicing care that is informed by patients' social backgrounds, including education on the right to health 18 and home visits for at‐risk patients.

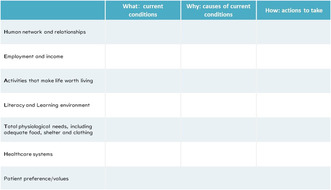

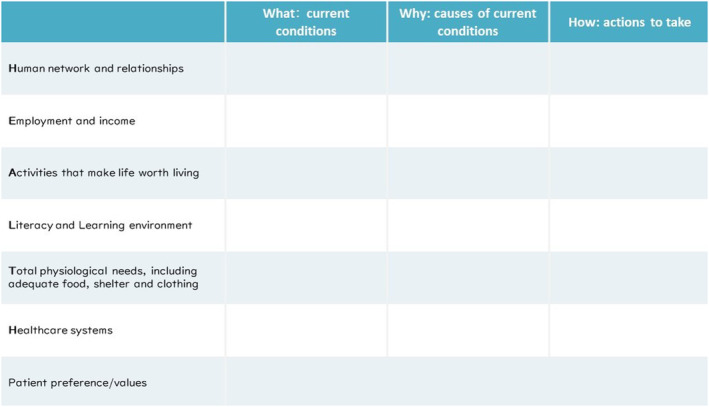

In 2019, two nurses who had been utilizing a tool‐based methodology for patients' social backgrounds were appointed as head nurses in a ward and an outpatient office, and the tool‐based program was initiated. This tool‐based approach, referred to as “Social Vital Signs (SVS),” is defined by in‐depth social background interviews and visual presentation of patient information that promotes a team‐based and multidisciplinary approach. 19 , 20 This methodology has the potential to improve the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and comprehension of patients, especially in challenging patient encounters. 21 In the outpatient settings, an inpatient survey form (see Table 1) was utilized to gather information and document it in the electronic medical record for staff accessibility, with survey‐based conferences held as necessary. In the wards, an inpatient assessment sheet (see Figure 1) was employed to elicit and evaluate patients' social backgrounds, with sheet‐based multidisciplinary conferences held. These forms were developed and modified by the nursing staff to collect necessary patient information and discuss nursing care. In 2020, 172 outpatients were surveyed, and 205 in 2021, including 13 visits by outpatient staff to patients' homes in 2020 and 14 in 2021. The number of sheet‐based conferences in the wards was 5 in both 2020 and 2021. The discretion to include specific patients in the survey rested with the frontline nursing staff.

TABLE 1.

Outpatient survey form.

| Basic information | |

| Name | |

| Age | |

| Address | |

| Insurance and Service Availability | |

| Health insurance | |

| Disability certificate | |

| Care level certificate |

Requiring help level: 1, 2 Long‐term care level: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Home‐care service provider | |

| Care manager | |

| Service |

Home‐visit nursing: Nursing station ( ) Frequency ( )[/week] |

|

Home help: Care station ( ) Frequency ( )[/week] | |

|

Home‐visit rehabilitation: Rehab station ( ) Frequency ( )[/week] | |

| Short‐term stay at care facilities | |

| Other | |

| Contact | |

| Emergent contact (First) |

Name: Relationship: Phone number: Address: |

| Emergent contact (Second) |

Name: Relationship: Phone number: Address: |

| Activity of Daily Living (ADL) | |

| Mobility (Ambulation) | Independent, Under observation, With cane, With rollator, On wheelchair, Totally dependent |

| Bathing | Independent, Partially dependent, Totally dependent |

| Place: Home, Day‐time care, Day‐time rehabilitation, Home‐visit bathing care, Other | |

| Toileting | Independent, With help, Bedside commode, Diaper |

| Falling within 6 months | Yes, No |

| Instrumental ADL | |

| Meal preparation | |

| Finance management | |

| Housekeeping | |

| Telephone use | |

| Laundry | |

| Medication management | Self, Family member ( ), Other ( ) |

| Shopping | |

| Access to clinic | On foot, Bus, taxi, Transportation by family, Other |

| Cognitive function | |

| Communication | Anything (e.g., hearing loss, articulation disorder) |

| Family member | |

| Pedigree | |

| Primary caregiver | |

| Reliable person other than family member (e.g., friends, neighbors) | |

| Backgrounds | |

| Housing | Own, Rent, Public, Nursing facility |

| Elevator: Yes, No | |

| Front stoop: Yes, No | |

| Steps: Yes, No | |

| Handrail: Yes, No | |

| Finance | Working, Pension, Welfare, Other |

| Life history | |

| Community participation | |

| Community for health promotion | |

| Patient hope and planning | |

| Assessment | |

| Next step (e.g., service introduction, conference, and information sharing) | |

FIGURE 1.

Inpatient social determinants of health (SDH) assessment sheet.

2.2. Reflexivity

This qualitative study conformed to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR). 22 The first author (M.D.) a primary care physician and Ph.D. student majoring in medical education, is a member of the team that devised the concept of SVS and has published several papers on the topic. 19 , 20 , 21 The second author (M.D., Ph.D.) a primary care physician and researcher in medical education, is well‐versed in the concept of SVS. The third, fourth, and fifth authors (M.D., Ph.D.) are experts in medical education.

From a researcher standpoint, the authors adopted a social constructivist perspective, recognizing that learning is a process of constructing individual understandings based on prior experiences and knowledge. 23 Social constructivists acknowledge that learning is shaped by the dynamic interaction between learners and the environment, in which they engage in actual practice. 23 , 24 The authors believe that participants construct their own comprehension of the SDH assessment tool through their experiences in nursing care and facility management.

2.3. Participants

Nurses who were actively engaged in tool‐based nursing care concerning patients' social backgrounds within the hospital were invited to participate in the study. To obtain a multidimensional perspective on the tool‐based nursing care initiative, a combination of snowball and purposive sampling was employed. In the initial phase, we enlisted the head nurses from each department and the leaders who spearheaded the implementation of the tool‐based approach. Subsequently, we requested them to identify nursing staff members who had hands‐on experience with the tool in frontline practice as well as those who held diverse viewpoints about the tool, including unfavorable perspectives. Furthermore, we intentionally sought to involve relatively less experienced staff and staff in the wards, as their representation was limited. Recruitment was conducted concomitantly with data analysis and was completed when data was saturated. 25 , 26

2.4. Preparation for interview

The hospital had organized a series of workshops for the nurses since 2020 to facilitate the implementation of the tool. To develop a comprehensive understanding of the programs, researchers obtained documentation of these workshops. They also read presentation materials provided by some of the nurses at a formal congress (see Data S1 for further information). The first author perused these data and communicated their practices to the other researchers. A thematic analysis was performed inductively to formulate hypotheses prior to the interviews (see Data S2 for a detailed codebook).

2.5. In‐depth interview

A semi‐structured interview guide was developed based on the hypotheses generated (see Data S3). The first author conducted each of the in‐depth interviews from October to November 2022. Due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, each interview was held online via the application of Zoom. Each interview lasted between 30 and 50 min. To ensure the utmost confidentiality, every participant was asked to partake in an interview in an empty room. Some participants responded at home and others at their workplaces. Each Zoom meeting room was secured with individual passwords. Recorded video data were promptly deleted postinterview, and recorded audio data were only preserved for transcription.

2.6. Data analysis

Thematic analysis was employed for the analysis of the interviews, utilizing a framework approach. 27 This approach consists of seven steps: verbatim transcription; familiarization with the entire interview; initial coding; development of a working analytical framework; re‐application of the framework to the entire data; summarization of the data into the framework; and interpretation of the data. The first and second authors iteratively coded and discussed the data, collapsing their analyses through all steps. The third, fourth, and fifth authors reviewed and revised the analysis. The results were discussed iteratively among all authors, and a consensus was reached. Finally, all participants were sent to the researchers' coding, reviewed it, and made revisions as necessary via e‐mail. This process was necessary for member checking.

2.7. Criteria for ensuring quality

To ensure the reliability, applicability to real‐world scenarios, and coherence of our findings, we evaluated our research methods against the quality criteria commonly utilized in qualitative research, as outlined below. 28

2.7.1. Credibility

To enhance credibility, we employed a dual data source approach, utilizing both pre‐investigation workshop documentation and interview data for coding purposes (data triangulation). Multiple researchers were engaged in the coding process, facilitating ongoing discussions and validation of codes (investigator triangulation). Additionally, we sought input from participants to validate our data interpretations (member checking).

2.7.2. Transferability

For bolstering transferability, we aimed to provide comprehensive insights into participants' contexts and extensively referenced their statements (thick description). We meticulously delineated the objectives guiding our sampling strategy, offering a detailed explanation thereof.

2.7.3. Dependability

To ensure dependability, we pursued data saturation, collecting data until no new themes emerged. Our data collection process was informed by continuous analysis (iterative data collection). Employing the framework approach, we consistently revisited the data, utilizing insights that surfaced during analysis (iterative data analysis).

2.7.4. Confirmability

Confirmability was ensured through a well‐documented record of each analytical step, subjected to iterative review (audit trail). Drawing from a social constructivist perspective, we individually reflected on our roles and viewpoints, as mentioned before (reflexivity).

2.8. Ethical consideration

For any materials to analyze, written permission for research use was obtained. The first author contacted potential interview participants by e‐mail, explained that their participation was voluntary and that they would not incur any disadvantages if they declined, and obtained written consent. Interviews were transcribed with anonymization. An incentive in the form of a gift certificate valued at JPY 2000 (approximately USD 15) was offered.

3. RESULTS

A total of 16 nurses participated in the study. All participants were self‐reported women. The median age was 44.5 years (range: 23–72 years) and the median duration of clinical experiences was 22 years (range: 2–50 years). Two participants were mainly engaged in staff management and the other 14 participants were responsible for providing daily patient care. Table 2 shows the demographical data.

TABLE 2.

Participants' demographics.

| Age [median (range)] | 44.5 (23–72) |

| Duration of clinical experience [median years (range)] | 22 (2–50) |

| Current setting | |

| Outpatient Office | 8 |

| Inpatient Ward | 4 |

| Regional Medical Liaison Office | 2 |

| Manager | 2 |

3.1. Integration and adoption of a tool‐based program

Participants reported that they had learned and experienced nursing care related to SDH before the implementation of the tool. Their adoption of the tool was facilitated by their recognition of its practical value in their professional practices, bolstered by institutional support and team collaboration. Four themes were identified as follows.

3.1.1. Accumulated learning and experience

Before the implementation, the participants frequently encountered patients with complex social needs, and they understood the importance of considering patients' social backgrounds.

Daily, I see numerous patients requiring various forms of support. As nurses, we strive to comprehend and provide care for them. (Interview 5)

However, some participants reported a challenge in addressing patients' social backgrounds.

A disconcerting scenario arose when a patient was brought to the emergency room. I was unable to properly address the social needs as I was unfamiliar with the patient. (Interview 15)

3.1.2. Awareness‐based facilitation of initiatives

Initially, some nurses expressed reluctance toward the program, harboring concerns about an increased workload and potential patient aversion.

I was apprehensive about losing focus on my other responsibilities. (Interview 16)

I wondered if I could pose inquisitive questions to patients with financial difficulties. (Interview 14)

However, once the program was underway, participants came to realize its utility. They comprehended that the program represented a continuation of their previous nursing care practices.

This tool serves as a synopsis of what we have previously garnered. (Interview 1)

When I employed the tool during an interview with a patient, the conversation flowed smoothly, and it did not take long. (Interview 16)

Participants were encouraged to take further steps after being both surprised and convinced by their newfound understanding of patients' social backgrounds.

Previously, we only experienced discomfort in seeing difficult patients, but now, we grasp that our patients are putting forth tremendous effort to make ends meet. (Interview 2)

Many nursing staff experienced that the tool‐guided interviews fostered a deeper understanding and allowed for individualized support. Subsequently, they began to incorporate the tool into their practice. (Interview 6)

Nurses who appreciated the significance and usefulness of the program recommended it to their colleagues.

It became increasingly widespread among the staff that the program was not challenging to implement. (Interview 1)

The acquisition of related concepts and reflective analysis of their experiences further encouraged the implementation of the program.

The concept of health rights and SDH has altered my perspective towards patients, […], imbuing me with the confidence that I am providing appropriate care. (Interview 3)

3.1.3. Institutional supports and leadership

The hospital made a concerted effort to establish the program and provided the necessary resources and personnel to facilitate implementation and learning. Articulated objectives served to inspire and motivate staff in their endeavors.

Each department established a quantifiable target for the number of tool‐based interviews to be conducted. (Interview 1)

Leadership within each department fostered a culture of encouragement, inspiration, and empathy among staff.

My supervisor challenged me to present a case study on an annual basis, which provided me with a source of motivation. (Interview 6)

When I encountered a patient with complex social needs, my supervisor advised me to utilize the tool as a means of gaining a better understanding of the patient. This guidance helped me to identify the most appropriate course of action. (Interview 9)

3.1.4. Being realistic

The workload was often considered excessive when participants struggled to literally complete the tool‐based interview.

Most of the time, when I thought I had to complete the task anyway, I was too busy to do it. (Interview 14)

Participants overcame various obstacles to utilizing the tool by continuously refining their on‐site approach. They mitigated time constraints by collaborating and sharing responsibilities, often transcending departmental boundaries. They also adapted the tool to meet the needs of individual patients by customizing its content and approach.

I came to understand that I could gather information incrementally, rather than attempting to complete the interview in one sitting. This realization made the task more manageable. (Interview 8)

I found that the process was made easier when I shared the tool with patients and filled it in together. (Interview 7)

The importance of the tool‐based survey was widely acknowledged among staff, and a collaborative system was established to ensure its successful implementation. (Interview 4)

3.2. The consequences of nursing care

Two principal themes emerged: the transformation of nurses themselves and the enhancement of nursing care quality.

3.2.1. Transformation of nurses themselves

Participants became more knowledgeable about the social backgrounds of their patients, which led to an increased sense of respect and empathy. As a result, they were able to provide collaborative care. Their experiences also helped to develop self‐affirmation. Three subthemes were identified as follows.

Collaboration with patients based on positive emotions

Participants initially had negative attitudes toward patients with complex social needs. However, after gaining an understanding of their social backgrounds, they developed empathy and respect. This led to a team‐based approach, such as addressing their challenges, redefining realistic goals, and collaborating with patients.

An older patient, living alone, was hospitalized. He required home oxygen and we initially tried to convince him to admit a nursing care home. But he insisted that he would definitely go home. We initially had nothing but a feeling of "Damn grandpa." But I encouraged the staff to consider why he was so committed to home and to use the tool to gather information. […] His house was built by the patient himself. It was why he was willing to die at home. We really know that he accepted dying alone. […] It turned out that, for the patient, the house was more important than his life. Then we adjusted nursing care and finally, he was able to go home. (Interview 4)

The completion of a tool‐based assessment also improved the relationship and communication between patients and nurses.

With just one session of completing the tool‐based assessment, the patient recognized me. We developed a rapport, a face‐to‐face relationship, the patient saying, "I see you're here today, and thanks for the other day." […] I think that the fact that the patient disclosed something in‐depth to me was special. (Interview 16)

Participants indicated that the utilization of the tool‐based assessment led to a heightened collaboration with patients, facilitated by a deeper understanding of their circumstances, rather than relying on analytical solutions.

We encountered a recurrently readmitted patient with diabetes, who had struggled with managing high glycemic levels and had difficulty attending regular hospital visits. On conducting an assessment using the tool, we discovered that this patient faced barriers in accessing healthcare due to familial relationships and daily hardships. […] Initially, we harbored negative sentiments towards the patient, presuming them to be a nuisance and non‐compliant. However, we soon realized that this was not the case. (Interview 12)

Aggressive approach based on accumulated experience

The experience of learning about patients' social backgrounds allowed participants to expect patients' social challenges when they had negative feelings, and they became active users of the tool.

I feel happy when I have a successful case where my intervention made the patient's life at ease by, for example, the application of long‐term care insurance. I want to do more about such nursing care. (Interview 8)

Reflecting on patients' social backgrounds and preferences in their care allowed for an expanded range of nursing care options This experience helped them recognize the multifaceted roles of nurses as care coordinators.

Only after commencing the use of the tool was I able to communicate with the community comprehensive support center or municipal office to exchange patient information and engage in collaborative discussions on necessary actions. (Interview 16)

Often, we tend to generalize positive care experiences with some patients to others. […] Now, we have access to more diverse care options and resources. We recognize our role as coordinators who connect patients with care managers and community resources. (Interview 2)

Affirmation of nursing care

Participants had an insight that negative sentiments toward patients with complex social needs stem from a paradoxical desire to address the issue while simultaneously feeling helpless in doing so.

When we perceive a lack of control over a patient, we often experience a sense of helplessness and attempt to alleviate our distress by thinking "Let the patient have their way," or "There is nothing we can do if the patient is unable to comply." However, the reality is that we do not truly hold these beliefs and strive to take action if possible. (Interview 9)

Participants gained self‐affirmation, acknowledging that their efforts improved patient outcomes and that they successfully navigated difficult patient encounters.

We experience a great sense of fulfillment when we successfully collaborate with our patients to attain shared objectives. I take great pride in my ability to accomplish such feats. Numerous such instances make this work so enjoyable. (Interview 11)

Participants expressed their feeling that experiencing the gratification of engaging with and providing care to patients as a nurse would mitigate the risk of exhaustion and burnout.

We can express our satisfaction by saying things like, "We made every effort to provide exceptional care for this individual." When we feel content with our performance, it engenders a feeling of fulfillment, as if we take pride in being a nurse. (Interview 6)

3.2.2. Enhancement of nursing care quality

The implementation of the tool aided in the provision of care for social needs among nurses, particularly novice nurses, and facilitated the continuity of nursing care. Further employment of the electronic health record system could broaden the applicability of the tool.

Entrance to social nursing care

Participants reported that adhering to the tool would ensure the acquisition of patient information to a certain degree, especially regarding their social support needs.

Using a tool to listen can be more comfortable than listening while intermittently considering what should be asked. […] Regardless of whether a nurse is a novice or a veteran, patient information can be collected in the same way by using the tool. (Interview 7)

The implementation of the tool reduced the obstacle for nurses to launch an approach for patients' social contexts.

This kind of tool would make it easier to encourage staff to review the social background of their patients. (Interview 8)

Less experienced staff perceived this tool as an instrument that facilitated the delivery of care at a level comparable to that of a more experienced and expert nurse.

The task of coordinating patient discharge was considered a daunting challenge for inexperienced nurses and was only achievable by those considered experts. The use of the tool can provide support in this task for a novice. (Interview 4)

Some participants reported that only utilizing the tool did not guarantee a favorable outcome. They asserted that the tool functioned only as a preliminary step, and that an additional comprehensive and compassionate approach was necessary.

Just imitating how to use a tool does not make for good care. (Interview3)

Ultimately, confronting patients as an individual is very important (Interview 11)

Enhanced continuity of nursing care

Participants conveyed that outpatient nursing was characterized by limited resources in terms of time and personnel, making it difficult to access patients' social backgrounds. However, the tool enabled nurse staff to gather patient information and approach each patient as a cohesive team. Some participants noted that, although immediate action might not be feasible, being cognizant of their patients' backgrounds enabled them to remain vigilant for a chance to intervene.

In an outpatient setting, patient information can easily become lost and critical details may be buried within medical records. Therefore, summarizing this information can expedite the review process and allow for immediate reflection on patient care within a limited timeframe. […] Occasionally, a patient may decline intervention, […] leading to the adoption of a policy that "we should carefully monitor this patient as he or she may not be ready to take the next step at this time, to ensure that we do not miss any future opportunities for positive intervention." Such an approach is deemed to be a critical attitude in patient care. (Interview 15)

The demonstration of continuity of care was evidenced by the collaboration between the outpatient and inpatient wards, as well as the practices within the ward.

Outpatient staff used the tool to compile information about this deprived patient. When the patient was admitted and we supported her discharge, the information from the outpatient department was quite helpful. (Interview 10)

Some participants expressed that the benefits of electronic health records should be more fully utilized.

A methodology to streamline the process of documenting collected data in the electronic health record must be developed. (Interview 10)

4. DISCUSSION

This study unveiled the implementation course of a comprehensive tool‐based SDH assessment program in nursing care and examined the experiences of nurses with the program. Participants effectively embraced the program by considering clinical practice, iterative learning, and support from leaders and peers. The assessment tool facilitated the clinical management of patients' social backgrounds and needs, and participants developed positive emotions towards their patients, which in turn enhanced their self‐esteem.

Participants underscored the interpersonal and coordinative role of nurses in patient care, thereby deepening their professional identity. Prior scholarly discourse implies that nurses can recognize their potential in reducing health inequities due to the emphasis on interpersonal relationship‐based care in their training programs. 29 Nurses can view SDH as integrated into nursing care and see addressing it as an opportunity to improve individualized care and patient education. 30 A growing body of literature describes nurses' role in assisting people experiencing structural disadvantage and integrating fragmented support systems. 31 To fulfill these responsibilities, the traditional clinical roles of nurses may need to be revised. 32 The findings of the study suggest that participants' profound insights into the role of nursing before tool implementation may facilitate its adoption. A thorough exploration of nurses' roles may be necessary for the implementation of SDH in nursing care.

Participants conveyed that team‐based iterative learning and support from peers and leaders wielded the potential to mitigate impediments in utilizing the tool and tackling patients' social. Previous research indicates that obstacles that hinder nurses from addressing patients' social needs comprise competing professional obligations, limited knowledge of community resources, time limitations, and inadequate organizational support. 13 , 32 The uncertainty about how to approach the recognized difficulties is also a significant hindrance for nurses, 13 and leads to a lack of confidence among them. 33 Inadequate knowledge and support to work with SDH can cause nurses' discomfort and the anticipation of discomfort from patients. 7 , 13 In this study, endorsement and guidance from both leaders and peers were discerned as mechanisms to bridge these knowledge and experience gaps, thereby fostering a collaborative and continuous patient care within a team‐based milieu. This achievement might not be exclusively realized through the mere introduction of the tool. The assessment of SDH can have adverse effects, such as weakening the therapeutic relationship and isolating patients, particularly when healthcare providers are not culturally competent, sensitive, or prepared, 34 so the abovementioned factors should be considered for the implementation of assessment tools.

The study detailed the process through which nursing staff developed their novel nursing care approach, involving iterative trials, comprehensive discussion, and reflective analysis. Critical service learning (CSL), a pedagogy that combines community service, reflective practice, and examination of social context, 35 , 36 has been identified as an effective approach for promoting the learning of SDH by reflecting on clinical experiences, fostering insightful discussions, and facilitating ongoing learning. 37 Such characteristics of CSL can be seen in the program of tool‐based nursing care. Furthermore, this study postulated that participants' antecedent exposure to SDH learning provided a foundational basis for tool‐guided nursing care. Previous research accentuates that learning the concepts related to SDH surely serves as an effective introduction in nursing education. 38 Such multifaceted approaches to learning may be crucial for the effective utilization of SDH assessment tools.

Participants utilized the electronic health record (EHR) system to ensure the continuity of their nursing care, and some insisted that the EHR could be used more effectively. A comprehensive care approach can be facilitated by the systematic documentation of patient data on SDH in the EHR. 39 Prior research suggests that effective implementation of EHR‐based SDH assessment necessitates accommodating leadership and flexibility in adapting to clinical settings 40 and these themes may align with the findings of this study. However, ethical concerns may arise regarding the recording of sensitive information in an EHR that is universally accessible. A clear policy on the handling of patient information should thus be established.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a single‐center study conducted in a small hospital in Japan, and nurses working in different settings may have different experiences. Second, the years of experience of the participants were bimodal, partly because most nurses with roughly ten years of experience were occupied with childrearing and faced difficulty participating in the research. Third, the study did not evaluate patient‐reported outcomes. Finally, the research team comprised exclusively of physicians and may not have comprehensively analyzed the distinct viewpoints of the nurses.

5. CONCLUSION

Nurses working in a small community hospital integrated a tool‐based SDH assessment program into their daily nursing practice by reflecting on their experiences, participating in iterative team‐based learning, and receiving support from their leaders and peers. The assessment tool helped nurses to consider the social contexts of patients and enabled them to provide more comprehensive care. The nurses experienced a change in their attitudes, leading to increased honesty with their patients and self‐esteem, as well as stronger relationships with patients. Understanding the engagement of nurses with the SDH assessment program could serve as a catalyst for healthcare institutions and nursing care facilities intending to offer personalized and contextually relevant care. This insight can drive the implementation of strategies aimed at achieving proficient nursing care, benefiting both the nursing staff and the patients. Further research is needed to validate whether this type of program reduces nurses' psychological stress and burnout, and to evaluate patient‐reported outcomes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author has stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the research ethics committee of the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine (No. 2021419NI).

Supporting information

Data S1.

Data S2.

Data S3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Mizumoto J, Son D, Izumiya M, Horita S, Eto M. The impact of patients' social backgrounds assessment on nursing care: Qualitative research. J Gen Fam Med. 2023;24:332–342. 10.1002/jgf2.650

REFERENCES

- 1. Johnson CB, Luther B, Wallace AS, Kulesa MG. Social determinants of health: what are they and how do we screen. Orthop Nurs. 2022;41:88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce AE, Proser M, Hollombe C, et al. How 6 organizations developed tools and processes for social determinants of health screening in primary care: an overview. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41:2–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bechtel N, Jones A, Kue J, Ford JL. Evaluation of the core 5 social determinants of health screening tool. Public Health Nurs. 2022;39:438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neadley KE, McMichael G, Freeman T, Browne‐Yung K, Baum F, Pretorius E, et al. Capturing the social determinants of health at the individual level: a pilot study. Public Health Res Pract. 2021;31:30232008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Naz A, Rosenberg E, Andersson N, Labonté R, Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration . Health workers who ask about social determinants of health are more likely to report helping patients: mixed‐methods study. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:e684–e693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abbott LS, Elliott LT. Eliminating health disparities through action on the social determinants of health: a systematic review of home visiting in the United States, 2005‐2015. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34:2–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Persaud S. Addressing social determinants of health through advocacy. Nurs Adm Q. 2018;42:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine . The future of nursing: leading change, advancing health. Washington DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011. 5, Transforming Leadership. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209867/. Accessed 21 Feb 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reutter L, Kushner KE. 'Health equity through action on the social determinants of health': taking up the challenge in nursing. Nurs Inq. 2010;17:269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Daly K, Pauly B. Nurse navigation to address health equity: teaching nursing students to take action on social determinants of health. Nurse Educ. 2022;47:E5–E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olshansky EF. Social determinants of health: the role of nursing. Am J Nurs. 2017;117:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colburn DA. Nursing education and social determinants of health: a content analysis. J Nurs Educ. 2022;61:516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Phillips J, Richard A, Mayer KM, Shilkaitis M, Fogg LF, Vondracek H. Integrating the social determinants of health into nursing practice: Nurses' perspectives. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(5):497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garg A, Boynton‐Jarrett R, Dworkin PH. Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA. 2016;316:813–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kato D, Ryu H, Matsumoto T, Abe K, Kaneko M, Ko M, et al. Building primary care in Japan: literature review. J Gen Fam Med. 2019;20:170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nishioka D, Tamaki C, Furuita N, Nakagawa H, Sasaki E, Uematsu R, et al. Changes in health‐related quality of life among impoverished persons in the free/low‐cost medical care program in Japan: evidence from a prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol. 2022;32:519–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suzuki S. Subsidies for pregnant women with "genuinely unavoidable special reasons". JMA J. 2022;5:240–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Human rights. World health organization. 2022. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/human‐rights‐and‐health. Accessed 21 Feb 2023.

- 19. Mizumoto J, Terui T, Komatsu M, Ohya A, Suzuki S, Horo S, et al. Social vital signs for improving awareness about social determinants of health. J Gen Fam Med. 2019;20:164–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Terui T, Mizumoto J, Harada Y, Ohya A, Takeda Y. A report of the social vital signs workshop at WONCA Asia Pacific regional conference 2019. J Gen Fam Med. 2020;21:92–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mizumoto J, Son D, Izumiya M, Horita S, Eto M. Experience of residents learning about social determinants of health and an assessment tool: mixed‐methods research. J Gen Fam Med. 2022;23:319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cleland J, Durning SJ, Mann K, MacLeod A. Constructivism: learning theories and approaches to research. Researching medical education. New York: Wiley Blackwell; 2015. p. 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guest G, Namey E, Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PloS One. 2020;15:e0232076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frambach JM, van der Vleuten CP, Durning SJ. AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Acad Med. 2013;88:552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith GR. Health disparities: what can nursing do? Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2007;8:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schneiderman JU, Olshansky EF. Nurses' perceptions: addressing social determinants of health to improve patient outcomes. Nurs Forum (Auckl). 2021;56:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Equipping for Equity Online Modules . EQUIP Health Care. Available from: https://equiphealthcare.ca/resources/equipping‐for‐equity‐online‐modules/. Accessed 21 Feb 2023.

- 32. Brooks Carthon JM, Hedgeland T, Brom H, Hounshell D, Cacchione PZ. "you only have time for so much in 12 hours" unmet social needs of hospitalised patients: a qualitative study of acute care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:3529–3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration . Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188:E474–E483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wallace AS, Luther B, Guo JW, Wang CY, Sisler S, Wong B. Implementing a social determinants screening and referral infrastructure during routine emergency department visits, Utah, 2017‐2018. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mitchell TD. Traditional vs. critical service‐learning: engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan J Commun Service Learn. 2008;14:50–65. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seifer SD. Service‐learning: community‐campus partnerships for health professions education. Acad Med. 1998;73:273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bower KM, Alexander KA, Levin MB, Jaques KA, Kub J. Using critical service‐learning pedagogy to prepare graduate nurses to promote health equity. J Nurs Educ. 2021;60:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Porter K, Jackson G, Clark R, Waller M, Stanfill AG. Applying social determinants of health to nursing education using a concept‐based approach. J Nurs Educ. 2020;59:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce A, Middendorf M, Hollombe C, Cowburn S, et al. Developing electronic health record (EHR) strategies related to health center patients' social determinants of health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:428–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gruß I, Bunce A, Davis J, Dambrun K, Cottrell E, Gold R. Initiating and implementing social determinants of health data collection in community health centers. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24:52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data S2.

Data S3.