Abstract

Pseudomonas putida MnB1 is an isolate from an Mn oxide-encrusted pipeline that can oxidize Mn(II) to Mn oxides. We used transposon mutagenesis to construct mutants of strain MnB1 that are unable to oxidize manganese, and we characterized some of these mutants. The mutants were divided into three groups: mutants defective in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes, mutants defective in genes that encode key enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and mutants defective in the biosynthesis of tryptophan. The mutants in the first two groups were cytochrome c oxidase negative and did not contain c-type cytochromes. Mn(II) oxidation capability could be recovered in a c-type cytochrome biogenesis-defective mutant by complementation of the mutation.

Bacterial Mn(II) oxidation has a major impact on the biogeochemical cycling of Mn and the many trace metals that adsorb to the surfaces of Mn oxides (46, 48). Bacterial Mn(II) oxidation is of practical concern in the fields of agriculture, bioremediation, and drinking water treatment. Mn deficiency in plants is often the result of bacterial and fungal Mn(II) oxidation in the soil (35); biological Mn(II) oxidation can be used for the removal of toxic contaminants from mine drainage (36) and is also an alternative to chemical oxidation in the clean-up of excess Mn from drinking water (37).

Despite the fact that bacterial Mn oxidation has attracted much attention from microbiologists for almost a century (28), little is known about the reason for this phenomenon or the mechanisms that are involved. It has frequently been proposed that the oxidation of soluble Mn(II) to insoluble Mn(IV) oxyhydroxides may result in energy gains for the bacteria for either autotrophic or mixotrophic growth, and the findings of several researchers suggest that such energy gains occur (2, 10, 15, 30). An article reviewing new insights that have been gained through molecular studies of enzymatic Mn(II) oxidation has recently been published (47).

Traditionally, much of the interest in bacterial Mn(II) oxidation focused on the so-called iron- and manganese-depositing bacteria, such as Leptothrix discophora, from which an Mn-oxidizing protein has been isolated (1, 7). With the isolation of more Mn-oxidizing bacteria over the years, it became clear that rather than being limited to a few specialized strains, Mn oxidation is widespread and is a common trait in ubiquitous seawater and freshwater pseudomonads (13, 23, 38). Pseudomonas manganoxidans MnB1 (= ATCC 23483) was isolated from an Mn crust that accumulated in drinking water pipes in Trier, Germany (44), and was recently reclassified as a Pseudomonas putida strain (12), a fact that was confirmed by us on the basis of the sequence of the 16S rRNA gene. Upon reaching the stationary phase, this organism oxidizes Mn(II) in liquid and solid media to Mn(IV) oxyhydroxides, which are precipitated on the cell surface. Within 2 days of growth on an Mn(II)-containing agar medium, the colonies, which are originally cream colored, become brown due to the accumulation of the precipitates. MnB1 produces a soluble protein late in the logarithmic growth phase, which catalytically oxidizes Mn(II) in cell extracts. This activity is destroyed by heat or by treatment with a protease (12, 29).

Since P. putida is a ubiquitous freshwater and soil bacterium, it provides an excellent model system for the study of Mn(II) oxidation. In this study we used transposon mutagenesis to obtain mutants of strain MnB1 that lost the ability to oxidize Mn(II). The mutated genes were partially sequenced and cloned, and the partial sequences were used to identify the genes based on similarities to genes in the GenBank database. A similar approach was used to study a related Pseudomonas strain, strain GB-1, and the results are reported in the accompanying paper (13).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. The mutants used are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida MnB1 (=ATCC 23483) | Manganese oxidizer | 44 |

| E. coli S17-1 (λpir) | thi pro hsdR recA::RP4:2-Tcr::Mu:Kmr::Tn7 (Tpr Smr), λpir lysogen | 11 |

| E. coli XL1-blue | recA1 lac endA1 gyrA46 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 F′ [proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10(Tcr)] | 8 |

| E. coli XL1-blue MR | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| E. coli HB101 | recA13 lacY1 hsdS20 supE44 ara-14 proA2 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript | Apr, α-lac/multiple cloning site | 3 |

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon, mob RK2, tra RK2, Kmr | 19 |

| pUTKm | Apr, Tn5-based delivery plasmid with Kmr, ori R6K, mob RP4 | 25 |

| pBBR1-MCS5 | Broad-host-range cloning vector, α-lac/multiple cloning site, Gmr | 32 |

| SuperCos 1 | cos Kmr Apr | Stratagene |

| p303Sst | 4-kb SstII region containing the I end of the transposon and flanking sequence from mutant 303 in pBluescript | This study |

| p303cos1 | 30-kb NotI fragment containing the ccm region inserted in SuperCos 1 | This study |

| pSC1 | 2.2-kb NotI fragment containing the ccmC-ccmE/F region inserted in pBluescript | This study |

| pCO1 | ccmC-ccmE/F region inserted as a 2.2-kb BamHI-SstI fragment (from pSC1) inserted into pBBR1-MCS5 | This study |

| p5802cos1 | 30-kb NotI fragment containing the insertion point in mutant 5802 inserted into SuperCos 1 | This study |

| p5802Pst | 3.5-kb PstI region containing the insertion point in mutant 5802, cut from p5802cos1, inserted into pBluescript | This study |

TABLE 2.

Mutants

| Strain | Colony sizea | Mn oxidationb | Reversion frequencyc | Accession no.d | Mutated genee | Organism in databasef | % Similarityg | Smallest sum probabilityg | Oxidase activityh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | +++ | +++ | NAi | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + |

| Group i mutants | |||||||||

| UT403 | +++ | − | − | U83209 | ccmE | P. fluorescens | 85 | 1.6 × 10−78 | − |

| UT302 | +++ | − | − | U83210 | ccmF | P. fluorescens | 76 | 1.2 × 10−59 | − |

| UT303 | +++ | − | − | U83211 | ccmF | P. fluorescens | 81 | 6.5 × 10−73 | − |

| UT402 | +++ | − | + | U83213 | ccmA | B. japonicum | 70 | 4.3 × 10−8 | |

| Group ii mutants | |||||||||

| UT405 | ++ | − | ++ | U83214 | sdhA | E. coli | 70 | 1.4 × 10−13 | − |

| UT501 | ++ | − | ++ | U83215 | sdhA | E. coli | 75 | 1.8 × 10−62 | − |

| UT4201 | ++ | − | + | U83216 | sdhB | E. coli | 62 | 7.1 × 10−29 | − |

| UT3501 | ++ | − | − | U83217 | sdhC | E. coli | 73 | 1.4 × 10−3j | − |

| UT3308 | ++ | − | + | U83219 | aceA | P. aeruginosa | 81 | 1.5 × 10−54 | − |

| UT1124 | + | − | ++ | U83219 | aceA | P. aeruginosa | 85 | 2.6 × 10−87 | − |

| UT1405 | + | − | ++ | U83219 | aceA | P. aeruginosa | 77 | 1.8 × 10−37 | − |

| UT5802 | +++ | − | − | U83220 | icd (2 genes) | A. vinelandii | 77 | 1.4 × 10−76 | − |

| U83221 | E. coli | 69 | 8.7 × 10−69 | ||||||

| Group iii mutants | |||||||||

| UT1112 | +++ | −/+ | − | U83222 | trpE | P. putida | 93 | 1.5 × 10−75 | + |

| UT3207 | +++ | −/+ | − | U83223 | trpE | P. putida | 90 | 5.6 × 10−65 | + |

+++, large (>4 mm); ++, medium; +, small (<1 mm).

+++, colony turns brown within a few days; −/+, colony turns light brown after more than a month; −, colony does not turn brown.

−, no revertants; +, up to 5% of colonies revert; ++, up tp 50% of colonies revert.

Accession number for sequences obtained from DNA flanking the insertion points of the transposon.

Mutated gene as determined by BLAST searches.

Organism from which the gene yielding the best match was sequenced.

Statistical parameter of BLAST search results.

+, oxidase activity present; −, oxidase activity absent.

NA, not applicable.

In mutant UT3501 the transposon insertion occurred only 67 bp from the end of the sdhC gene, resulting in a smallest sum probability value of only 0.0014 despite the fact that the 67 bases exhibited 73% identity with the bases in the E. coli sequence.

Strain MnB1 was routinely grown on LEP medium [0.5 g of yeast extract per liter, 0.5 g of Casamino Acids per liter, 5 mM d-(+)-glucose, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.5), 1 ml of trace element solution per liter, 100 μM MnCl2), which is a modification of a medium used for maintenance of L. discophora (7). The trace element solution contained (per liter of distilled water) 10 mg of CuSO4·5H2O, 44 mg of ZnSO4·7H2O, 20 mg of CoCl2·6H2O, and 13 mg of Na2MoO4·2H2O. Escherichia coli cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Selection after conjugation was performed on tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) or triple sugar iron medium (TSI) supplemented with kanamycin, nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, and triphenyltetrazolium chloride (22). The following concentrations of antibiotics were used: kanamycin, 100 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; methicillin, 100 μg/ml; nalidixic acid, 230 μg/ml; nitrofurantoin, 100 μg/ml; triphenyltetrazolium chloride, 140 mg/ml; and gentamicin, 10 μg/ml for E. coli and 100 μg/ml for strain MnB1.

Mutagenesis.

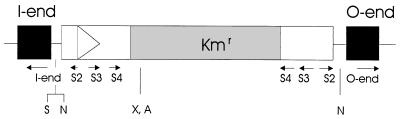

Transposon mutants were generated by conjugation of strain MnB1 with E. coli S17-1 λpir carrying the suicide plasmid pUTKm, which contains a mini-Tn5 synthetic transposon that confers kanamycin resistance (25) (Fig. 1). Conjugations were performed overnight at 30°C on cellulose filters (Micron Sep filters; Micron Separation Inc., Westboro, Mass.) placed on LB agar plates. After conjugation the cells were resuspended in LB medium, diluted, and plated onto TSA or TSI selective media. The resulting exconjugants were then replica plated onto LEP medium plates by using transfer membranes (Magna nylon membranes; Micron Separation Inc.), and colonies that did not turn brown after several days were isolated. These colonies were transferred back to selective medium to confirm their resistance and then were considered nonoxidizing mutants.

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the transposon, not drawn to scale. The solid boxes represent the synthetic ends, and the shaded box represents the kanamycin resistance gene. The arrows represent oligonucleotides used in this work. Because the transposon outer regions (not including the I-end and O-end regions) consist of inverted repeats, oligonucleotides S2, S3, and S4 match sequences in both regions. The letters indicate restriction sites relevant in this work (S, SstII; N, NotI; X, XhoI; A, AvaI).

DNA extraction.

DNA was purified with DNA purification columns (Qiagen-tip 100/G; Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.).

Southern blotting.

Mutants were analyzed by Southern blotting to confirm that a single transposon insertion was present and to identify a restriction fragment containing the end of the transposon of a suitable size for cloning. DNA from mutants were digested with restriction enzymes NotI or SstII, which cut close to the I end of the transposon (Fig. 1). When both enzymes failed to produce a fragment smaller than 10 kb, the DNA was cut with both NotI and SalI. The digested DNA was electrophoresed in a 0.8% TBE agarose gel, and the gel was dried for 3 h in a gel drier (model 483; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The dried gel was then probed with a labeled oligonucleotide complementary to the I end of the transposon (I-end) by standard procedures.

DNA library.

A strain MnB1 DNA library was cloned into cosmid SuperCos I (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by using the manufacturer’s instructions. The library contained 50,000 CFU, and the mean insert size was greater than 30 kb.

Cloning of disrupted genes.

Most of the mutated genes were cloned into a plasmid vector. Chromosomal DNAs from the mutants were digested with an enzyme combination that yielded a positive fragment in Southern analyses of suitable size for cloning. The digested DNA were electrophoresed in 0.8% TBE agarose, and areas corresponding to the positive bands were cut out, purified with Geneclean (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.), cloned into the vector pBluescript (Stratagene), and transformed into E. coli XL1-blue. The resulting colonies were screened by colony hybridization with the same oligonucleotide probe used for the Southern blots (I-end); positive colonies were isolated, their plasmids were extracted, and the identities of the plasmids were confirmed by restriction analysis followed by DNA hybridization with the I-end oligonucleotide.

Inverse PCR.

Some of the mutated genes were not cloned but were amplified by using inverse PCR (39). Chromosomal DNAs were digested with restriction enzyme XhoI or AvaI, which cut once within the body of the transposon. The digested DNA were diluted to a concentration of 2 μg/ml and were self-ligated for 16 h at 15°C to allow circularization of the DNA fragments. The circular molecules were then amplified by a step-down PCR (24) by using back-to-back primers (primers S2 and S3) located near the ends of the transposon. When amplification was weak or nonspecific, a second PCR was conducted by using nested primers (S4 and I-end or S4 and O-end).

Sequencing.

All sequencing was done with an ABI automated sequencer (model 373A) by using a PRISM Ready Reaction DyeDeoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer). Cloned genes were sequenced by using plasmid DNA and primers T3 and T7. PCR-amplified genes were sequenced directly by using the purified inverse PCR products and primers S2, I-end, and O-end. The 16S rRNA sequence was obtained by PCR amplification using standard methods and primers (33).

Sequence analysis.

DNA sequences were identified by using the BLAST (basic local alignment search tool) server of the National Center for Biotechnology Information accessed over the Internet (4). Sequence contigs were assembled with the program ASSEMBLY LIGN (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.). The 16S rRNA sequence was aligned with other sequences using the Ribosomal Database Project WWW server (34).

Complementation.

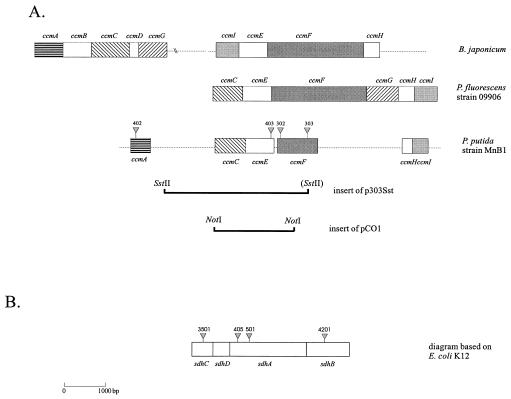

A 4-kb SstII fragment (adjacent to the I end of the transposon and containing part of ccmF and several genes upstream from it, including ccmC and ccmE [Fig. 2]) cloned from the ccmF mutant UT303 was used as a probe to isolate several library clones. A positive 2.2-kb NotI fragment was isolated from one of these clones (p303cos1) and was cloned into the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1-MCS5. Since this vector does not have a NotI site, the fragment was first cloned into pBluescript and then cleaved again as a BamHI-SstI fragment and cloned into the broad-host-range vector. The resulting plasmid (pCO1) was mobilized into ccmE mutant UT403 by triparental conjugation. Conjugation was performed as described above but at a higher temperature (33°C) by using E. coli XL1-blue containing derivatives of broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1-MCS5 (32) as the donor and E. coli HB101 containing plasmid pRK2013 as the helper (19). Recipient colonies were selected on TSA plates containing kanamycin, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, and triphenyltetrazolium chloride and were transferred to Mn(II)-containing LEP medium to screen for Mn(II) oxidation.

FIG. 2.

(A) Transposon insertions in mutants in the ccm operon and alignment of this operon with similar operons in B. japonicum (accession no. M60874 and Z22517) and P. fluorescens 09906 (accession no. U44827). The gene nomenclature is based on the gene nomenclature of Page et al. (42). Regions that have been sequenced are indicated by boxes. Also shown are the regions cloned into plasmids p303Sst and pCO1, which were used to probe the cosmid library and to complement mutant UT403, respectively. (B) Transposon insertions in mutants with mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase complex. The diagram is based on the sequence of E. coli K-12 (accession no. X00980).

Enzyme activity and cytochrome c assays.

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was determined qualitatively by a tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (TMPD)-based assay (45). Since Mn oxides react with TMPD, yielding false-positive results, cultures were grown on LB agar plates to avoid the presence of any Mn oxides. Isocitrate dehydrogenase activity was determined qualitatively by spectrophotometric assays (43).

Cytochrome c was assayed spectrophotometrically. Cells were grown in 350 ml of LB medium containing kanamycin (100 μg/ml) to the late log phase. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 5 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 7.5% glycerol, and lysed with a French pressure cell at 15,000 lb/in2. The lysates were centrifuged twice at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant fraction (cell extract) was analyzed with a split-beam scanning spectrophotometer (lambda 3; Hewlett-Packard) with phosphate buffer in the reference cuvette. Reduced spectra were obtained by adding sodium dithionite to a final concentration of 1 mM to the sample and reference cuvettes, and oxidized spectra were obtained by adding potassium ferricyanide to a final concentration of 250 μM to both cuvettes.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database. The accession number for the 16S rRNA gene is U70977. The accession numbers for other genes are shown in Table 2.

RESULTS

16S rRNA sequence.

To verify that strain MnB1 is indeed a strain of P. putida, we amplified by PCR and sequenced 1,487 bp of the 16S rRNA gene of this strain. The sequence obtained was manually aligned with similar sequences in the GenBank database and was 98.6% identical to the sequence of P. putida PB4 (accession no. D37925). This confirmed that strain MnB1 is indeed a P. putida strain.

Isolation of mutants.

The frequency of plasmid transfer during conjugation could not be measured with the delivery system used. The frequency of cells in which a transposition event occurred was calculated by determining the ratio of recipient cells that acquired kanamycin resistance during conjugation to the total number of recipient cells; this ratio was found to be about 2.5 × 10−6. Since the presence of antibiotics in a medium strongly inhibits Mn oxidation, we first selected for conjugants on a selective medium and then replica plated the cells onto Mn-containing, antibiotic-free medium to screen for a loss of Mn oxidation. The frequency of stable non-Mn-oxidizing mutants was about 1 in 5,000 kanamycin-resistant colonies.

From about 60 different matings, 30 transposon mutants that had lost the ability to oxidize Mn were isolated, and 14 of these mutants are described in this paper. The phenotypes of these mutants varied greatly. Some mutants had a morphological phenotype very similar to that of the wild type, while others grew slowly and failed to produce large colonies. The mutants also varied in their production of a fluorescent substance, most probably a siderophore, which is produced by the wild type under iron-limiting conditions (26). A similar phenomenon that occurs in a related Mn(II)-oxidizing bacterium is described in the accompanying paper (13). The slowly growing mutants, unlike the fast-growing mutants, reverted frequently to an Mn(II)-oxidizing, wild-type-like phenotype which was coupled to a loss of kanamycin resistance, which indicated that the transposon was lost.

Sequence analysis.

DNA sequences flanking the transposon insertion points in the mutants were determined and were submitted to GenBank (Table 2), and the detailed results of BLAST searches have been published elsewhere (9). Sequence analysis of mutated genes revealed that some of the mutants had insertions in the same operons or in genes whose products have similar functions in the organism, and thus the mutants could be divided into the following three groups: group i, cytochrome c biogenesis mutants (insertions in ccmF, ccmA and ccmE); group ii, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle mutants (insertions in sdhA, sdhB, sdhC, aceA, and icd); and group iii, tryptophan biosynthesis mutants (trpE).

Most of these mutants could be identified from the sequence directly flanking the transposon insertion point; the only exception was mutant UT5802, in which the sequence flanking the insertion point did not match any of the sequences in the GenBank database. We amplified the DNA flanking the insertion point of mutant UT5802 by inverse PCR and used the PCR product as a probe to isolate an intact version of the region from the genomic library. A positive 4-kb PstI fragment was isolated from a library cosmid (p5802cos1) and cloned into pBluescript (resulting in p5802Pst). Sequences obtained from both ends of this fragment revealed the presence of two putative isocitrate dehydrogenase-encoding genes (icd) located back to back and flanking the insertion spot. The insertion was located upstream of both genes, which are transcribed in opposite directions away from the insertion point. The two genes are different and are similar to icd genes from E. coli and from Azotobacter vinelandii. To see if the insertion had an effect on the expression of the proteins, we assayed the mutant for isocitrate dehydrogenase activity. While the wild type and all other mutants were isocitrate dehydrogenase positive, mutant UT5802 was clearly isocitrate dehydrogenase negative (results not shown), confirming that the insertion indeed inactivated both icd genes.

Table 2 shows the phenotypes and mutated genes of the different mutants, and Table 3 summarizes information about the putative roles of the mutated genes in the organism.

TABLE 3.

Genes identified by partial sequence analysis from mutants

| Gene | Description |

|---|---|

| ccmE | Possibly periplasmic protein, shares some similarity with chlorophyll binding protein, involved in c-type cytochrome biogenesis |

| ccmF | Membrane-bound protein, contains putative heme-binding motif, involved in c-type cytochrome biogenesis |

| ccmA | ATP binding subunit of an ABC-type translocator, involved in c-type cytochrome biogenesis |

| sdhABCD | Operon encoding the four units of the succinate dehydrogenase complex, a key enzyme in the TCA cycle, and the only enzyme of that cycle that is directly linked to the electron transport chain; the enzyme transfers electrons from succinate to a quinone |

| aceA | Lipoate acetyltransferase, a subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, responsible for oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate |

| icd | Isocitrate dehydrogenase, catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate to 2-oxoglutarate |

| trpE | α Subunit of anthranilate synthetase, the enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step in the sequence of reactions which lead to the biosynthesis of tryptophan from chorismate |

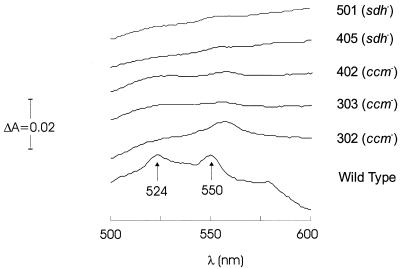

Cytochrome c oxidase activity and cytochrome c presence.

Since the group i mutants had transposon insertions in the cytochrome c biogenesis operon, we tested all of the mutants for cytochrome c oxidase activity. All of the group i and group ii mutants had lost this activity, while the group iii mutants retained it (Table 2). Spectrophotometric analysis of cytochrome c showed that a lack of c-type cytochromes correlated with a lack of oxidase activity (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Sodium-dithionite-reduced minus potassium-ferricyanide-oxidized difference spectra of supernatant fractions from several mutants. Only the wild type produced peaks at 524 and 550 nm, which is characteristic of cytochrome c550.

Complementation of a ccmE mutant.

To verify that the insertions in the ccm operon are indeed responsible for the Mn(II) oxidation deficiency in these mutants, we complemented one of the ccm mutants (mutant UT403) with a DNA fragment containing the same region isolated from the chromosome. A plasmid (pCO1) containing this region was mobilized into ccmE mutant UT403 by triparental conjugation, and recipient colonies that contained the plasmid were selected on TSA plates containing gentamicin. All of the resulting colonies were kanamycin resistant, and all were cytochrome c oxidase positive and oxidized Mn(II) when they were transferred to antibiotic-free LEP medium plates.

Chemical complementation of mutants.

Cross-streaking experiments, in which one strain was streaked close to a streak of another strain, revealed that wild-type cells secreted a substance into the medium that diffused into the agar and restored Mn(II) oxidation in most group ii mutants (namely, the sdh and aceA mutants). The wild type could not restore oxidation in the ccm mutants, but ccm mutants and even E. coli could induce oxidation in the sdh and aceA mutants. In an attempt to identify the diffusive compound, disks soaked with different intermediates of the TCA cycle were placed on a plate covered with a lawn of an sdh mutant (mutant UT501). The compounds that were tested were succinate, fumarate, 2-oxoglutarate, oxaloacetate, acetyl coenzyme A, and malate. Only one of these compounds, malate, induced Mn(II) oxidation in cells growing around the disk, but the induction was slow and weak.

DISCUSSION

Characterization of mutants.

The four group i mutants (mutants UT302, UT303, UT402, and UT403) had insertions in different genes (ccmF, ccmF, ccmA, and ccmE, respectively) of an operon that has been found to be crucial for the assembly of mature c-type cytochromes in several other bacterial species (Fig. 2), including Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Rhodobacter capsulatus, E. coli, and Pseudomonas fluorescens (for a recent review, see reference 49). The best matches (70 to 85% identity) are with sequences of similar genes of two strains of the related organism P. fluorescens (strains 17400 and 09906). All group i mutants grew very well on LEP medium and formed large colonies similar to those of the wild type. They were all cytochrome c oxidase negative (Table 2) and had no detectable c-type cytochromes (Fig. 3). The restoration of Mn oxidation in a ccmE mutant by complementation with a chromosomally derived copy of the ccmE gene confirmed the role of the ccm operon in Mn oxidation. The same conclusion is also reported for the Mn-oxidizing bacterium P. putida GB-1 in the accompanying paper (13).

One might wonder why we did not find mutations in genes encoding a specific cytochrome(s). A possible reason is that elimination of a single cytochrome does not result in a markedly different phenotype of the mutant, because other cytochromes in the cell assume the role of the missing cytochrome (17, 50). Thus, the only way to obtain a cytochrome c-deficient phenotype is to eliminate all of the cytochromes together by knocking out cytochrome biosynthesis. However, other explanations are possible, as discussed below.

The eight mutants in group ii had insertions in genes encoding different enzymes of the TCA cycle; four of them (mutants UT405, UT501, UT4201, and UT3501) had insertions in genes encoding different subunits of the succinate dehydrogenase (sdh) complex (Fig. 2). Despite the fact that no similar genes have been sequenced from a Pseudomonas species before, the match with the E. coli sequences provided reliable identification (Table 2). Three other mutants (mutants UT1124, UT1405, and UT3308) had insertions in the aceA gene, which encodes the lipoate acetyltransferase subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. The closest match in the database was to a similar sequence from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In the last mutant in this group (mutant UT5802) two different isocitrate dehydrogenase genes were inactivated by a single insertion of a transposon. While it is outside the scope of this investigation, it should be noted that icd genes have not been identified in a Pseudomonas species before, and the arrangement of two genes similar to the genes from E. coli and A. vinelandii, back to back, deserves closer attention in the future. All group ii mutants grew more slowly than the wild type, formed smaller colonies, and, unlike the wild type and group i mutants, could not grow on succinate. Their longevities were also decreased, and colonies left on plates for 1 month died, unlike the wild-type colonies, which remained viable for much longer periods of time. Interestingly, all of these mutants were cytochrome c oxidase negative and had no detectable c-type cytochromes (Fig. 3). This fact led to the hypothesis that the Mn oxidation deficiency in these mutants may be a secondary phenomenon caused by the lack of c-type cytochromes, which results from the unusual biosynthetic pathways which must exist in such mutants either because of a lack of precursor molecules or because of a negative effect on the regulation of cytochrome c synthesis. One possible explanation is a lack of heme. All cytochromes contain heme, and the first committed step in heme biosynthesis is the synthesis of α-levulinate (18). In Pseudomonas strains α-levulinate is synthesized from glutamate (6), which in turn is synthesized largely from 2-oxoglutarate, an intermediate of the TCA cycle. It is possible that the bypass of essential enzymes, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and succinate dehydrogenase, depletes the concentration of available 2-oxoglutarate to such a degree that heme biosynthesis stops or is greatly diminished. Under these conditions the bacteria are not able to synthesize active c-type cytochromes. To test this hypothesis, disks soaked with hemin (a source of heme), α-levulinate (a precursor of heme synthesis), and glutamate (a precursor of α-levulinate) were placed next to streaks of the group ii mutants. However, these compounds failed to restore oxidation in any of the mutants. This negative result might rule out this explanation, but it is also possible that the generally impaired energy metabolism in these mutants had a negative effect on the regulation of heme biosynthesis, or perhaps these compounds could not be transported into the cells.

An intriguing finding was the fact that when P. putida MnB1 cells (either wild type, group i mutants, group iii mutants) and even E. coli cells were streaked near group ii mutants, they secreted a substance into the medium that restored Mn(II) oxidation in group ii mutants. While we could not discover the nature of this substance, it is clear that there was not a direct chemical reaction between the secreted substance and Mn(II) in the medium, since E. coli, which does not oxidize Mn(II), still restored oxidation in the mutants. Rather, the substance must affect the mutants in a way that partially restores their ability to oxidize Mn(II).

The two group iii mutants had insertions in the trpE gene, which encodes the α subunit of anthranilate synthetase, an enzyme that is involved in the biosynthesis of tryptophan. A similar gene has been sequenced from P. putida before, and there was more than 90% identity with that sequence. These two mutants grew like the wild type on LEP and LB media and formed large colonies. Their Mn(II) oxidation capabilities were severely deficient, but after a long time on LEP medium plates (>1 month), they showed some oxidation. When grown on plates supplemented with tryptophan, they oxidized Mn(II) after 3 days. Unlike most of the other mutants, these mutants were oxidase positive. While it is difficult to interpret this unexpected result, it is possible to speculate. It has been shown that mutants of Methylobacterium extorquens and Paracoccus denitrificans deficient in c-type cytochrome biogenesis cannot assemble tryptophan-tryptophylquinone, a unique cofactor of the enzyme methylamine dehydrogenase (41). If a similar cofactor was essential for Mn(II) oxidation, one would expect that a defect in cytochrome c biosynthesis would stop Mn(II) oxidation completely, while a defect in tryptophan synthesis would greatly slow the process down.

The cytochrome c biogenesis operon has been shown to be involved directly or indirectly in many different functions of bacterial cells. To mention a few, mutants of P. fluorescens 17400 lost the ability to produce the siderophore pyoverdine (20), mutants of P. fluorescens 09906 lost copper resistance and general competitiveness (51), and mutants of Azorhizobium caulinodans lost the ability to hydroxylate nicotinate (31). There are several ways in which the products of the cytochrome c biogenesis operon can be involved in Mn(II) oxidation; one frequently cited way is that c-type cytochromes are essential components in an electron transfer chain that channels electrons from a Mn(II)-oxidizing factor to the electron acceptor, most likely oxygen (5, 14, 21, 27). However, a c-type cytochrome may be a part of the Mn(II)-oxidizing factor itself, as in the case of the hydroxylamine oxidoreductase complex in the genus Nitrosomonas, which catalyzes the oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite. This complex contains approximately 24 c-type cytochromes of many types (16). As discussed above for the trpE mutants, a third option is that either the products of the cytochrome c maturation genes or c-type cytochromes themselves are involved in the biosynthesis of other molecules, such as tryptophan-tryptophylquinone, which may be involved in Mn(II) oxidation. For more discussion of the potential role of the ccm operon in Mn oxidation, see the accompanying paper (13).

So far, while our research has identified several genes that play a role in Mn oxidation, it has not revealed a gene encoding an Mn(II)-oxidizing factor. We cannot rule out the possibility that such a component exists and could be found by isolating and characterizing more mutants. We tested 16 more non-Mn(II)-oxidizing mutants that have not been characterized yet (and are not described here) and found that 2 of them were TMPD positive and therefore may have a mutation in such a gene. Furthermore, the presence of two Mn(II)-oxidizing factors was recently demonstrated in a closely related strain, P. putida GB-1, by Mn staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels containing electrophoresed supernatant fractions of cell extracts (40). Mn(II)-oxidizing activity was detected by the formation of Mn oxide on the protein bands after incubation of the gel in an MnCl2 solution. A non-Mn(II)-oxidizing mutant of strain GB-1 (13) was found to have a mutation in a novel gene that includes two motifs encoding copper binding sites, indicating a relationship to the multicopper oxidase family. Considering that two Mn(II)-oxidizing bacteria (L. discophora and Bacillus sp. strain SG-1) were found to have Mn(II) oxidation-related proteins that belong to this group (47), it is quite possible that the novel gene encodes an Mn oxidase in P. putida GB-1 and that a very similar gene will be found in strain MnB1.

Clearly, the process of Mn(II) oxidation in P. putida is complex, and considerable effort will be required before we fully understand it. In future work in our lab we will continue to isolate and characterize transposon mutants while we pursue isolation and identification of the Mn(II)-oxidizing components of strain MnB1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. N. Timmis for providing plasmid pUTKm, M. E. Kovach for providing plasmid pBBR1-MCS5, L. Park for her great help, M. Silverman for advice, and D. Bartlett for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank J. P. M. de Vrind, G. J. Brouwers, P. L. A. M. Corstjens, J. den Dulk, and E. W. de Vrind-de Jong for sharing their findings with us prior to publication.

Portions of this research were supported by grants MCB94-07776 and OCE94-168944 from the National Science Foundation. R.C. was supported in part by a fellowship from the University of California Toxic Substances Research and Teaching Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams L F, Ghiorse W C. Characterization of an extracellular Mn2+-oxidizing activity and isolation of Mn2+-oxidizing protein from Leptothrix discophora SS-1. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1279–1285. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1279-1285.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali S H, Stokes J L. Stimulation of heterotrophic and autotrophic growth of Sphaerotilus discophorus by manganese ions. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1971;37:519–528. doi: 10.1007/BF02218522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alting-Mees M A, Short J M. pBluescript II: gene mapping vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9494. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arcuri E J, Ehrlich H L. Cytochrome involvement in Mn(II)-oxidation by two marine bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:916–923. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.5.916-923.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avissar Y J, Ormerod J G, Beale S I. Distribution of δ-aminolevulinic acid biosynthesis pathways among phototrophic bacterial groups. Arch Microbiol. 1989;151:513–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00454867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boogerd R C, de Vrind J P M. Manganese oxidation by Leptothrix discophora. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:489–494. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.489-494.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Short J M. XL1-Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376–379. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspi R. Molecular biological studies of manganese oxidizing bacteria. Ph.D. thesis. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caspi R, Haygood M G, Tebo B M. Unusual ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase genes from a marine manganese-oxidizing bacterium. Microbiology. 1996;142:2549–2559. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Lorenzo V, Eltis L, Kessler B, Timmis K N. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene (Amsterdam) 1993;123:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DePalma S R. Manganese oxidation by Pseudomonas putida. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vrind J P M, Brouwers G J, Corstjens P L A M, den Dulk J, de Vrind-de Jong E W. The cytochrome c maturation operon is involved in manganese oxidation in Pseudomonas putida GB-1. App Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3556–3562. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3556-3562.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrlich H L. Manganese oxidizing bacteria from a hydrothermally active area on the Galapagos Rift. Ecol Bull (Stockholm) 1983;35:357–366. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrlich H L, Salerno J C. Energy coupling in Mn2+ oxidation by a marine bacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ericson R H, Hooper A B. Preliminary characterization of a variant CO-binding heme protein from Nitrosomonas. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;275:231–244. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson S J. The functions and synthesis of bacterial c-type cytochromes with particular reference to Paracoccus denitrificans and Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1058:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira G C, Gong J. 5-Aminolevulinate synthase and the first step of heme biosynthesis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1995;27:151–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02110030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figurski D H, Helinski D R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaballa A, Koedam N, Cornelis P. A cytochrome c biogenesis gene involved in pyoverdine production in Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 17400. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:777–785. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.391399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham L A, Salerno J C, Ehrlich H L. Electron transfer components of manganese oxidizing bacteria. In: Kim C H, editor. Advances in membrane biochemistry and bioenergetics. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1987. pp. 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant M A, Holt J G. Medium for the selective isolation of members of the genus Pseudomonas from natural habitats. App Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1222–1224. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1222-1224.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory E, Staley J T. Widespread distribution of ability to oxidize manganese among freshwater bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:509–511. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.2.509-511.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hecker K H, Roux K H. High and low annealing temperatures increase both specificity and yield in touchdown and stepdown PCR. BioTechniques. 1996;20:478. doi: 10.2144/19962003478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Höfte M. Classes of microbial siderophores. In: Barton L L, Hemming B C, editors. Iron chelation in plants and soil microorganisms. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogan V C. Electron transport and manganese oxidation in Leptothrix discophorus. Ph.D. thesis. Columbus: Ohio State University; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson D D. The precipitation of iron, manganese, and aluminium by bacterial action. J Soc Chem Ind. 1901;21:681–684. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung W K, Schweisfurth R. Manganese oxidation by an intracellular protein of a Pseudomonas species. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1979;19:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kepkay P E, Nealson K H. Growth of a manganese oxidizing Pseudomonas sp. in continuous culture. Arch Microbiol. 1987;148:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitts C L, Lapointe J P, Lam V T, Ludwig R A. Elucidation of the complete Azorhizobium nicotinate catabolism pathway. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7791–7797. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7791-7797.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane D S. 16S and 23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley; 1990. pp. 115–148. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maidak B L, Larsen N, McCaughey M J, Overbeek R, Olsen G J, Fogel K, Blandy J, Woese C R. The Ribosomal Database Project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3485–3487. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mann P J G, Quastel J H. Manganese metabolism in soils. Nature. 1946;158:154–156. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathur A K, Dwivedy K K. Biogenic approach to the treatment of uranium mill effluents. Uranium. 1988;4:385–394. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mouchet P. From conventional to biological removal of iron and manganese in France. Am Water Works Assoc J. 1992;84:158–167. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nealson K H. The isolation and characterization of marine bacteria which catalyze manganese oxidation. In: Krumbein W E, editor. Environmental biogeochemistry and geomicrobiology. 3. Methods, metals and assessment. Ann Arbor, Mich: Ann Arbor Science Publishers Inc.; 1978. pp. 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ochman H, Medhora M M, Garza D, Hartl D L. Amplification of flanking sequences by inverse PCR. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninki J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols—a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okazaki M, Sugita T, Shimizu M, Ohode Y, Iwamoto K, de Vrind-de Jong E W, de Vrind J P M, Corstjens P L A M. Partial purification and characterization of manganese-oxidizing factors of Pseudomonas fluorescens GB-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4793–4799. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4793-4799.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Page M D, Ferguson S J. Mutants of Methylobacterium extorquens and Paracoccus denitrificans deficient in c-type cytochromes biogenesis synthesize the methylamine-dehydrogenase polypeptides but can not assemble the tryptophan-tryptophylquinone group. Eur J Biochem. 1993;218:711–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Page M D, Sambongi Y, Ferguson S J. Contrasting routes of c-type cytochrome assembly in mitochondria, chloroplasts and bacteria. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearce L G, Reeves H C, Birge E A. Isocitrate dehydrogenase assays on intact bacterial cells. Anal Biochem. 1985;147:194–196. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schweisfurth R. Manganoxydierende Bakterien. I. Isolierung und Bestimmung einiger stamme von Manganbakterien. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1973;13:341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarrand J J, Groschel D H M. Rapid, modified oxidase test for oxidase-variable bacterial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:772–774. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.4.772-774.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tebo, B. M. 1991. Manganese(II) oxidation in the suboxic zone of the Black Sea. Deep Sea Res. 38(Suppl. 2):S883–S905.

- 47.Tebo B M, Ghiorse W C, van Waasbergen L G, Siering P L, Caspi R. Bacterially mediated mineral formation: insights into manganese(II) oxidation from molecular genetic and biochemical studies. In: Banfield J F, Nealson K H, editors. Geomicrobiology: interactions between microbes and minerals. Vol. 35. Washington, D.C: The Mineralogical Society of America; 1997. pp. 225–266. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tebo B M, Nealson K H, Emerson S, Jacobs L. Microbial mediation of Mn(II) and Co(II) precipitation at the O2/H2S interfaces in two anoxic fjords. Limnol Oceanogr. 1984;29:1247–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thöny-Meyer L. Biogenesis of respiratory cytochromes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:337–376. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.337-376.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Spanning R J, Wansell C, Harms N, Oltmann L F, Stouthamer A H. Mutagenesis of the gene encoding cytochrome c550 of Paracoccus denitrificans and analysis of the resultant physiological effects. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:986–996. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.986-996.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang C, Azad H R, Cooksey D A. A chromosomal locus required for copper resistance, competetive fitness, and cytochrome c biogenesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]