Abstract

A novel hyperthermophilic bacterium was isolated from pink filamentous streamers (pink filaments) occurring in the upper outflow channel (temperature, 82 to 88°C) of Octopus Spring in Yellowstone National Park, Wyo. The gram-negative cells grew at low salinity at temperatures up to 89°C in the neutral to alkaline pH range. Depending on the culture conditions, the organisms occurred as single motile rods, as aggregates, or as long filaments that formed streamer-like cell masses. The novel isolate grew chemolithoautotrophically with hydrogen, thiosulfate, and elemental sulfur as electron donors and oxygen as the electron acceptor. Alternatively, under aerobic conditions, formate and formamide served as sole energy and carbon sources. The novel isolate had a 16S rRNA sequence closely related to the 16S rRNA sequence obtained from uncultivated pink filaments. It represents a new genus in the order Aquificales, the type species of which we name Thermocrinis ruber (type strain, OC 1/4 [= DSM 12173]).

Currently, the only chemolithoautotrophic, hyperthermophilic representatives in the bacterial domain are members of the genus Aquifex, which grow at optimal and maximal temperatures of 85 and 95°C, respectively (23, 43). The type strain of Aquifex pyrophilus was originally isolated from a submarine hydrothermal vent system at the Kolbeinsey Ridge north of Iceland at a depth of 106 m. In the energy-yielding reactions of this organism hydrogen, elemental sulfur, and thiosulfate serve as electron donors, while oxygen and nitrate are used as electron acceptors (23). Therefore, Aquifex pyrophilus is a facultative aerobe. Phylogenetic analyses based on 16S rRNA sequence comparisons showed that Aquifex pyrophilus represents the deepest divergence in the bacterial domain (17). Due to this outstanding phylogenetic position, the new order Aquificales was proposed. The closest known relatives of the genus Aquifex are members of the genus Hydrogenobacter, which belong to the same order (17, 36). Representatives of the genus Hydrogenobacter grow optimally at temperatures between 70 and 75°C, while no growth is observed at 81°C (3, 7). They are autotrophic aerobes, growing by oxidation of hydrogen, thiosulfate, and elemental sulfur (1, 3, 7, 8). Hydrogenobacter thermophilus, “Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum,” and some unnamed Hydrogenobacter-like isolates were obtained from terrestrial hot springs (8, 24–27), while “Hydrogenobacter halophilus” was isolated from a marine hot spring (34). Recently, additional Hydrogenobacter relatives were obtained from hot composts (7).

The occurrence of whitish, yellowish, and pinkish masses of bacteria at temperatures up to 88°C in the White Creek area of Yellowstone National Park, Wyo., was reported more than 30 years ago (9–12). Microscopy of gelatinous pinkish masses (pink filaments) from the outflow channel of Octopus Spring revealed dense tangles of long filaments (9, 10). Spectrophotometry of acetone extracts of this cell material produced no chlorophyll spectrum (9, 10), but a red carotenoid pigment was identified (5). Radioisotope incorporation experiments carried out with pink filament material were unsuccessful (10). The first attempts to extract appreciable amounts of nucleic acid from the pink biomass failed (41). In a recent phylogenetic study, a single 16S ribosomal DNA sequence clone, EM 17, was obtained, and this clone was classified with the pink filaments on the basis of in situ hybridization studies (37). A phylogenetic analysis grouped the sequence of EM 17 with the sequences of members of the order Aquificales (17, 23, 37). Until now, attempts to cultivate representatives of the pink filament group have been unsuccessful (10, 12, 37, 41).

In this study, we describe the cultivation, isolation, and unique physiological and biochemical properties of the pink-filament-forming organisms from Octopus Spring.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Ammonifex degensii DSM 10501 (22), Aquifex pyrophilus DSM 6858 (23), Thermotoga maritima DSM 3109 (21), and Methanococcus igneus DSM 5666 (14) were obtained from the Lehrstuhl für Mikrobiologie, Regensburg, culture collection. “Aquifex aeolicus” (18) and the new organism Thermus sp. strain HI 9 were undescribed isolates from our culture collection. H. thermophilus TK-H was kindly provided by M. Aragno, Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Université de Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland. H. thermophilus TK-6 (= IAM 12695) (25) was obtained from the culture collection of the Institute of Applied Microbiology, University of Tokyo.

Culture conditions.

For enrichment attempts LS medium was used; this medium contained (per liter) 680 mg of KH2PO4, 120 mg of NaNO3, 200 mg of NaHCO3, 9 mg of FeCl3 · 6H2O, 4 mg of quinic acid, 10 ml of a trace vitamin solution (4), 5 ml of a trace mineral solution (22), and a mixture containing l-(+)-lactate, formate, citrate, fumarate, acetate, propionate, pyruvate, succinate, glycolate, and dl-malate (each at a final concentration of 1 mM). For stock maintenance and experimental studies, new isolate OC 1/4 was cultivated in a low-salt medium whose composition was based on a chemical analysis of Octopus Spring in Yellowstone National Park (synthetic Octopus Spring medium [OS medium] [10]). This medium contained (per liter) 256 mg of NaCl, 1.7 mg of KH2PO4, 0.8 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 10.3 mg of H3BO3, 23 mg of Na2SO4, 0.3 mg of NaNO3, 15 mg of KCl, 0.1 mg of FeCl3 · 6H2O, 0.06 mg of MnSO4 · H2O, 1,000 mg of NaHCO3, and 10 ml of a trace mineral solution (22). In the metabolic studies, elemental sulfur (final concentration, 0.05% [wt/vol]) or Na2S2O3 · 5H2O (final concentration, 0.1% [wt/vol]) was added. Carbonate-free medium was obtained by omitting NaHCO3. OC 1/4 was routinely grown in 28-ml serum tubes containing 10 ml of OS medium and 0.05% (wt/vol) elemental sulfur. The pH was adjusted to 7 with H2SO4. Unless indicated otherwise, the gas phase consisted of 300 kPa of N2-H2-O2 (94:3:3, by volume). Growth was determined by direct cell counting with a Thoma chamber (depth, 0.02 mm).

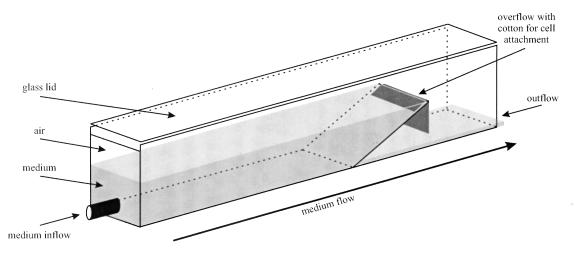

For studies of growth on solid surfaces, cotton, cover glasses (uncoated or coated with a silicone solution [Serva, Heidelberg, Germany]), and muscovite glimmer (catalog no. BU 006027-T; Balzers Union, Balzers, Switzerland) were tested. In order to create conditions resembling those of the natural environment in the hot outflow of Octopus Spring, cells were cultivated in a handmade glass chamber with a permanent flow of medium (9, 20, and 29 ml/min) (Fig. 1). The glass plates (alkali-limestone glass) were connected with thermostable liquid rubber (Praktikus, Grevenbroich, Germany). Pieces of cotton fixed at the overflow of the chamber were used for cell attachment (Fig. 1). The chamber was flushed with OS medium (supplemented with 0.1% [final concentration] Na2S2O3 · 5H2O), that had been prewarmed to 92°C in a 300-liter enamel-protected fermentor. The temperature was measured with a NiCr-Ni probe (testotherm, Lenzkirch, Germany) connected to a Schwille type 568 digital thermometer. For plating studies, OS medium was supplemented with 0.4% MgCl2 · 6H2O and 0.1% Na2S2O3 · 5H2O and was solidified with 1.5% Gelrite (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). All plating procedures were carried out under a protective argon atmosphere. The plates were incubated in a pressure cylinder (4) under 200 kPa of N2-O2 (97:3, vol/vol) at 80°C.

FIG. 1.

Glass chamber used for Thermocrinis ruber growth studies. The chamber (160 by 20 by 20 mm) consisted of single glass plates connected by silicone rubber and a detachable glass lid. Cotton at the culture medium overflow was used for cell attachment.

Cell masses were grown at 80°C with stirring (150 rpm) in a 300-liter enamel-protected fermentor (Bioengineering, Wald, Switzerland) pressurized with 150 kPa of N2 and 3% (vol/vol) O2. Light-dark experiments were carried out by using a 10-liter glass fermentor (Bioengineering) with stirring (150 rpm); the fermentor was pressurized with 107 kPa of H2-CO2-O2 (79:18:3, by volume) and was illuminated from a distance of about 0.60 m with a 150-WNDL metal halide lamp (Powerstar HQI-TS; Osram).

Light microscopy and electron microscopy.

Light microscopy and photography were carried out as described elsewhere (28). Samples for transmission electron microscopy were prepared as described previously (22, 39). Electron micrographs were obtained with a Philips model CM 12 electron microscope at 120 kV.

For scanning electron microscopy, the cells were first fixed with 2% (final concentration) glutaraldehyde in the original culture medium for 120 min at room temperature and then transferred into cacodylate buffer (75 mM sodium cacodylate, 1 mM MgCl2; pH 7.2) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The samples were rinsed in cacodylate buffer and postfixed for 90 min in the same buffer containing 1% (final concentration) osmium tetroxide. After washing in double-distilled water and dehydration with a graded series of acetone solutions, cells were critical point dried with liquid CO2, mounted with conductive tabs (Plano, Wetzlar, Germany), and sputter coated with platinum by using a magnetron sputter coater (model SCD 050; BAL-TEC, Walluf, Germany), which produced a layer about 5 to 7 nm thick. All pictures were obtained with a Hitachi model S-4100 field emission scanning electron microscope equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis.

Analysis of metabolic products.

Quantitative sulfate and qualitative ammonia analyses were carried out as described previously (23). H2S was determined qualitatively as described by Huber et al. (21).

Test for diaminopimelic acid and catalase.

Diaminopimelic acid was assayed by thin-layer chromatography (38). To determine the presence of catalase, about 100 μl of a 3% (vol/vol) H2O2 solution was dropped onto about 0.2 g of packed cells. The development of gas bubbles indicated that catalase was present.

DNA isolation and base composition.

DNA was isolated as described previously (29). The G+C content was determined by performing a melting point analysis (33) and by directly analyzing the nucleosides (44).

16S rRNA analysis.

Isolation of nucleic acids, amplification of the 16S rRNA gene, sequencing, and sequence data analysis were carried out as described by Burggraf et al. (15). The following forward and reverse sequencing primers were used: 27F (5′ GGGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG 3′), 533F (5′ TGBCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA 3′), 517R (5′ ACCGCGGCKGCTGGC 3′), 690R (5′ TCTACGCATTTCACC 3′), 1100R (5′ AGGGTTGCGCTCGTTG 3′), and 1492R (5′ ACGGHTACCTTGTTACGACTT 3′). The sequence obtained was aligned with a set of representative bacterial sequences (obtained from the Ribosomal Database Project [32]) by using the ARB program from the Department of Microbiology of the Technical University in Munich, Germany (31). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining program with the Jukes and Cantor correction included in the ARB package.

Cell fixation.

For whole-cell hybridization experiments, cells were fixed by adding 0.1 volume of a 30% (wt/vol) formaldehyde solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubating the preparation for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed in PBS, the cells were stored in a 1:1 mixture of PBS and 99.8% ethanol at −20°C (2). Fixed cells were spotted onto microscopic slides as described elsewhere (16).

Oligonucleotide probes.

An alignment of 16S rRNA sequences (ARB program [31]) was screened for a signature position to design a probe specific for the Aquificales. The probe AQUI 542 (5′ TCGCGCAACGCTCGGG 3′) was synthesized and labeled with Indocarbocyanin (CY 3) by MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany).

Whole-cell hybridization.

In situ hybridizations were carried out at 46°C as described by Burggraf et al. (16). The hybridized cells were viewed with a Nikon Microphot EPI-FL microscope equipped with a UV lamp and an HQ-CY3 filter set (AF-Analysentechnik, Tübingen, Germany).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the OC 1/4 16S rRNA gene has been deposited in the EMBL nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AJ005640.

RESULTS

Collection of samples.

Biomass consisting of pink filaments attached to rock surfaces and pieces of wood (samples OC 1 and OC 4) was collected in October 1994 with sterile forceps from the upper outflow channel near the source pool of Octopus Spring (formerly Pool A [11]); the original temperatures were 82 to 88°C, and the original pH was 8.0. The upper end of the filament growth was about 1.5 m from the actual lip of the pool. The samples were transferred into 100-ml storage bottles, which were then tightly sealed with rubber stoppers. An anoxic sample was obtained as described previously (42). The samples were transported to the laboratory by air and were stored during transport and afterward at ambient temperatures.

Enrichment and isolation.

In order to isolate the pink-filament-forming organisms from the Octopus Spring samples, 10 ml of LS medium was inoculated with approximately 1 ml of original samples OC 1 and OC 4. Enrichment was attempted immediately after the samples arrived. The preparation was incubated at 85°C in a closed 28-ml serum tube in the presence of 300 kPa of N2-O2 (99.95:0.05, vol/vol) with shaking (50 rpm). After 2 days of incubation, the LS medium contained about 106 motile, rod-shaped cells per ml. The enrichment culture could be successfully transferred to the same medium. A single cell, which was optically trapped by using a strongly focused infrared laser beam (optical tweezers), was separated from the mixed culture under visual control and was grown in pure culture (selected cell cultivation) (6, 20). In order to improve the growth yield of this culture (designated OC 1/4), a new medium (OS medium) was designed based on the results of a chemical analysis of Octopus Spring (10). OS medium was supplemented with different electron donors, electron acceptors, and carbon sources (e.g., elemental sulfur, oxygen, thiosulfate, CO2, and short-chain organic acids). Enhanced growth of OC 1/4 was observed in OS medium containing 0.1% thiosulfate with 300 kPa of N2-O2 (99.95:0.05, vol/vol) as the gas phase; the concentration of the organism was about 107 cells/ml under these conditions. Growth of the culture was stimulated about fivefold when the oxygen concentration was increased to 3% (vol/vol) and 3% (vol/vol) hydrogen was added. Unless indicated otherwise, all of the experiments described below were carried out with the optimized medium. Enrichment of relatives of OC 1/4 from the original samples after storage for nearly 4 years was unsuccessful, indicating that the organisms died.

Morphology.

Cells of isolate OC 1/4 were gram-negative, motile rods with rounded ends; the average cell length was 1 to 3 μm, and the average cell width was 0.4 to 0.5 μm. Spores were not formed. When grown in closed 28-ml serum tubes, strain OC 1/4 occurred predominantly as single cells or as pairs of cells during the logarithmic growth phase. In addition, cell aggregates composed of four to several hundred individuals were observed in the late-logarithmic and stationary growth phases. When OC 1/4 was cultivated in 1-liter bottles containing 300 ml of medium, very large aggregates were formed; these aggregates were macroscopically visible as small pinkish flocs.

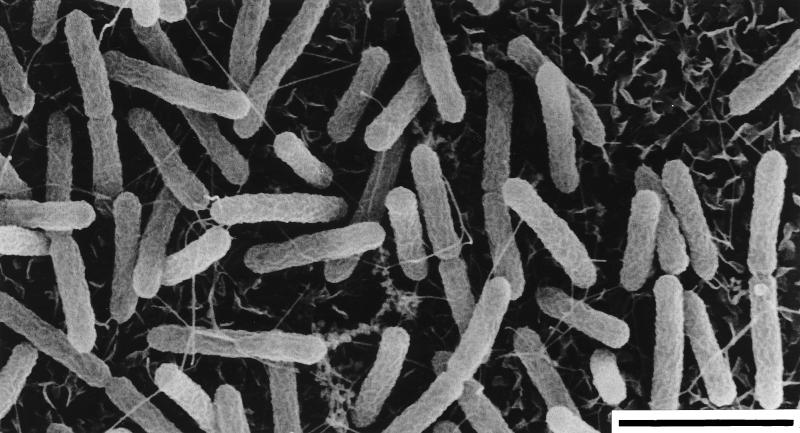

To investigate the ability of isolate OC 1/4 to grow on solid surfaces, small pieces of cover glasses (uncoated or coated with silicon) or of muscovite glimmer were placed in serum tubes. No growth was observed on uncoated cover glasses. In contrast, OC 1/4 showed a strong tendency to grow on coated cover glasses and on muscovite glimmer. The surfaces were densely covered with cells, which occurred singly or in pairs (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of Thermocrinis ruber rod-shaped cells grown on a silicon-coated cover glass. The flakes in the background are silicon. Bar, 2 μm.

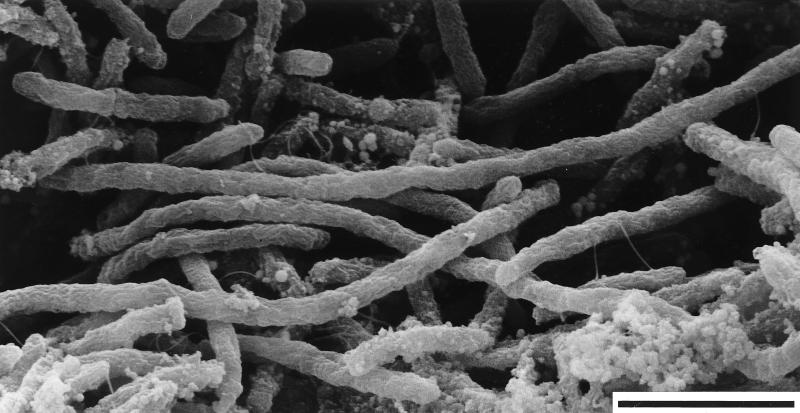

In order to simulate the natural environment, isolate OC 1/4 was cultivated at 80 to 85°C with a permanent flow of medium and exposure to air (Fig. 1). After 3 days, a beige color was observed on the surface of cotton attached at the overflow. After 7 days, a pink network of cells had formed; this network was predominantly composed of long filament bundles (Fig. 3). Single filaments had a diameter of approximately 0.4 μm (Fig. 3). In addition, single cells, pairs of cells, and cell aggregates were present; single cells, pairs of cells, and cell aggregates were also observed in the liquid phase in the glass chamber. Different rates of flow of the medium (9, 20, and 29 ml/min), pH values between 6.5 and 8.0, or a lower incubation temperature (60°C) did not influence the formation of these streamer-like cell masses or their color.

FIG. 3.

Scanning electron micrograph of long filaments of Thermocrinis ruber from the pink streamer network formed at the overflow of the glass chamber (Fig. 1). Bar, 2 μm. The granular material in the lower part of the image is precipitates containing sulfate, as determined by energy-dispersive X-ray analysis.

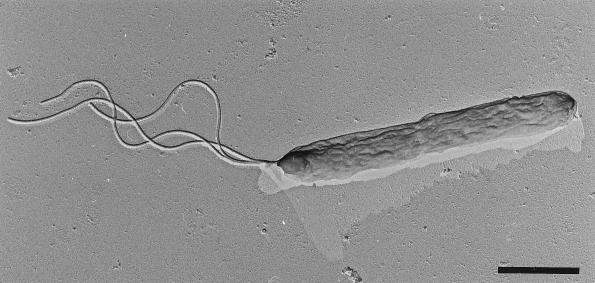

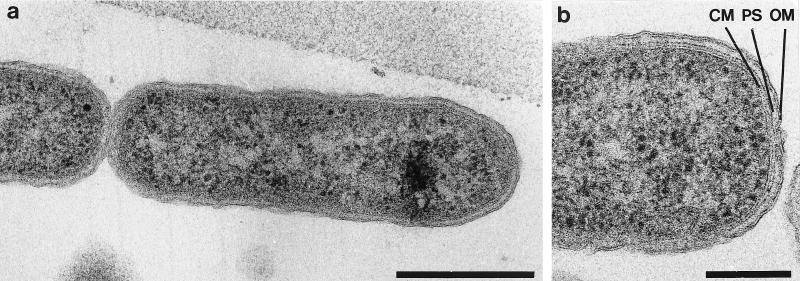

In transmission electron micrographs, isolate OC 1/4 exhibited monopolar polytrichous flagellation, with up to three flagella per cell (Fig. 4). An examination of ultrathin sections of freeze-substituted cells (Fig. 5a and b) revealed a cytoplasmic membrane (width, 8 nm) and a cell wall (total width, 25 to 30 nm) consisting of a periplasmic space (most likely containing peptidoglycan) and an outer membrane (width, 8 nm). In electron micrographs of freeze-etched cells (data not shown), the outer membrane appeared to contain small patches of regularly ordered proteins, most likely porins (40). There was no evidence of large, well-ordered crystalline arrays indicative of S-layer proteins.

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron micrograph of a single flagellated cell of Thermocrinis ruber that was air dried and platinum shadowed (from two directions). Bar, 1 μm.

FIG. 5.

(a) Ultrathin section of a freeze-substituted cell of Thermocrinis ruber. Bar, 0.5 μm. (b) Enlarged view of the cell envelope of Thermocrinis ruber, CM, cytoplasmic membrane; PS, periplasmic space; OM, outer membrane. Bar, 0.2 μm.

Metabolism.

Isolate OC 1/4 grew chemolithoautotrophically under microaerophilic culture conditions with oxygen as the electron acceptor. Oxidation of molecular hydrogen, thiosulfate, or S0 was an energy-yielding reaction. Up to 3.5 μmol of sulfuric acid per 108 cells was formed as a final product in the presence of S0. Optimal growth was observed in the presence of S0 and a gas mixture containing N2, H2, and O2 (94:3:3, by volume). With S0, the maximum oxygen concentration for growth was 6% (vol/vol). At oxygen concentrations below 3% (vol/vol), OC 1/4 reduced S0 to H2S in the presence of H2. Isolate OC 1/4 was not able to grow autotrophically under anaerobic culture conditions with hydrogen as the electron donor and potassium nitrate or sodium nitrate (final concentration, 0.01 to 0.1%) as the electron acceptor.

Alternatively, OC 1/4 grew with 0.1% formate or 0.1% formamide in the presence or absence of carbonate with a gas phase containing N2 and O2 (97:3, vol/vol). This result indicates that OC 1/4 is able to grow chemoorganoheterotrophically. The growth rates and final cell titers were comparable to those obtained under autotrophic growth conditions with sulfur, hydrogen, and oxygen with a gas phase containing N2, H2, and O2 (94:3:3, by volume). When OC 1/4 was grown on formamide, ammonia was formed. No growth was observed on formaldehyde (0.001 to 0.1%), methanol (0.05 to 0.5%), l-(+)-lactate (1 mM), citrate (1 mM), fumarate (1 mM), acetate (1 mM), propionate (1 mM), pyruvate (1 mM), succinate (1 mM), glycolate (1 mM), dl-malate (1 mM), peptone (0.01%), yeast extract (0.01%), meat extract (0.01%), or brain heart infusion (0.01%) with a gas phase containing N2 and O2 (97:3, vol/vol).

Physiological characterization.

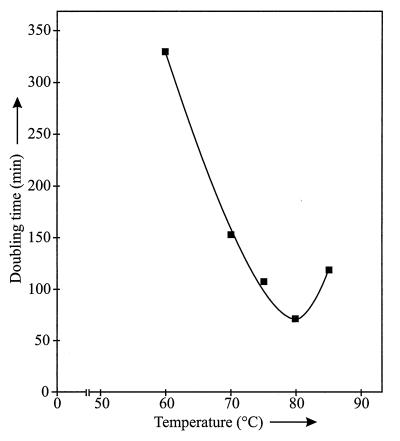

Isolate OC 1/4 grew at temperatures between 44 and 89°C, and the optimal doubling time at 80°C was 70 min (Fig. 6). No growth was observed at 90°C. Isolate OC 1/4 grew at pH 7 and 8.5. The maximum salt concentration for growth was 0.4% NaCl. No growth was observed in the presence of 0.5% NaCl.

FIG. 6.

Effect of temperature on the growth of Thermocrinis ruber. Doubling times were calculated from the slopes of the growth curves (data not shown).

Effect of light on cell color.

When OC 1/4 was cultivated in the presence of 3% (vol/vol) oxygen in the dark or in the light, the cell masses were pink in all cases.

Plating studies.

Isolate OC 1/4 was plated onto Gelrite plates under microaerophilic conditions (N2-O2, 97:3 [vol/vol]) by using thiosulfate as the electron donor. After 7 days of incubation at 80°C, round brownish red colonies with diameters of about 1 mm had developed.

Diaminopimelic acid.

meso-Diaminopimelic acid was detected in cell hydrolysates of isolate OC 1/4 (Rf, 0.21). Cell hydrolysates of Aquifex pyrophilus and “Aquifex aeolicus” (Rf, 0.20 to 0.21) were used as positive controls. Diaminopimelic acid was not present in hydrolysates of H. thermophilus TK-H and TK-6.

Catalase activity.

Packed cells exhibited gas production after a 3% (vol/vol) H2O2 solution was added, indicating that catalase activity was present.

Whole-cell hybridization.

Aquifex pyrophilus, H. thermophilus TK-6 and TK-H, and isolate OC 1/4 exhibited strong hybridization signals with probe AQUI 542. Thermotoga maritima, Ammonifex degensii, and Thermus sp. strain HI 9 exhibited no hybridization signals. “Aquifex aeolicus” did not hybridize with probe AQUI 542, most likely due to a mismatch in the 16S rRNA at position 545 (G→A) (Escherichia coli numbering [13]).

DNA base composition and 16S rRNA phylogeny.

Total DNA of isolate OC 1/4 had a G+C content of 47.8 mol% as calculated by direct analysis of the mononucleosides and 47.2 mol% as determined by melting point analysis.

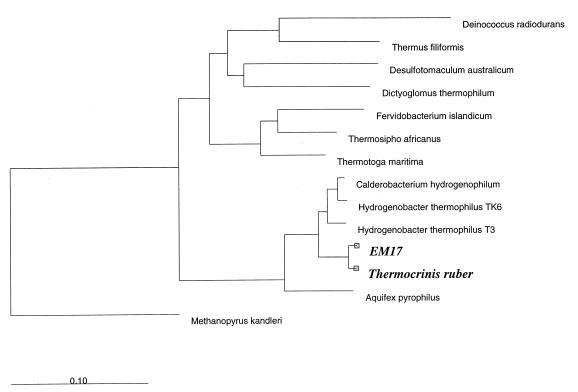

Using 16S rRNA sequence comparisons, we identified isolate OC 1/4 as a member of the Aquificales. Within this order, the evolutionary distances between OC 1/4 and Aquifex pyrophilus and between OC 1/4 and H. thermophilus TK-6 were 12.8 and 6.5%, respectively. The 16S rRNA sequence of OC 1/4 exhibited a level of similarity of 98.7% to the 16S rRNA sequence of clone EM 17 obtained from a phylogenetic analysis of ribosomal DNAs from the pink filaments of Octopus Spring (37). Figure 7 shows a phylogenetic tree that includes isolate OC 1/4.

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic tree determined by neighbor-joining analysis of 16S rRNA sequences. The scale bar represents 0.10 fixed mutations per nucleotide position.

DISCUSSION

Based on 16S rRNA sequence comparisons, novel isolate OC 1/4 from the pink filaments of Octopus Spring in Yellowstone National Park was identified as a member of the order Aquificales (23). Within this order, OC 1/4 shares the following features with the two previously described genera, the genera Aquifex and Hydrogenobacter (3, 23): gram-negative stain reaction, rod-shaped morphology, autotrophic growth, and the ability to oxidize hydrogen, sulfur, and thiosulfate in the presence of oxygen. Like members of the genus Hydrogenobacter, OC 1/4 grows at low salinity levels (up to 0.4% NaCl), reflecting its adaptation to its low-salt environment. However, OC 1/4 differs from members of the genus Hydrogenobacter by (i) the formation of H2S from S0, (ii) a positive catalase reaction, and (iii) the presence of meso-diaminopimelic acid. In contrast to members of the genus Aquifex, OC 1/4 is not able to grow at high salinity levels or anaerobically by nitrate reduction. OC 1/4 differs from members of both previously described genera by its ability to form streamers and by its lack of a regular surface lattice (23, 26, 30). Furthermore, the new isolate is able to grow chemoorganoheterotrophically on formate or formamide, which is a previously undescribed metabolic property for representatives of the Aquificales. Consistent with the unique combination of morphological, physiological, and biochemical properties of OC 1/4 is its phylogenetic position in the 16S rRNA tree, in which OC 1/4 represents a separate lineage within the Aquificales (Fig. 7). Therefore, we propose that OC 1/4 represents a new genus, which we describe here as the genus Thermocrinis. The type species is Thermocrinis ruber (hot, red hair), and the type strain is Thermocrinis ruber OC 1/4 (= DSM 12173).

Despite various investigations, information concerning the pink-filament-forming organisms of Octopus Spring has been poor, mainly because of a failure to cultivate and isolate representatives. On the basis of phylogenetic results, it has been suggested previously that hydrogen may be the clue to cultivate the organisms (37). However, in earlier attempts, we were unable to obtain enrichment cultures by using different media with hydrogen as the electron donor. In contrast, the use of a medium containing organic acids as energy sources led to a pure culture of the pink-filament-forming organism Thermocrinis ruber. This culture should allow direct examination by a polyphasic approach and studies of peculiar properties of the pink filaments, as proposed by Palleroni (35). Pure-culture studies showed that formate and formamide are used as energy and carbon sources for growth. This metabolic flexibility makes Thermocrinis ruber independent of inorganic growth substrates in nature and extends our knowledge concerning the basic physiological properties of members of the Aquificales significantly.

Like the pink filaments in the current of hot water in Octopus Spring, Thermocrinis ruber grew in filamentous streamers, when we created conditions resembling those found in the natural environment. In contrast, cultures of Thermocrinis ruber contained predominantly single, motile cells when they were grown in serum tubes under microaerophilic conditions. Therefore, filament formation appears to be directly related to a permanent water current and may be a response to exceedingly high oxygen concentrations. These results are consistent with the natural situation, in which filament formation is observed only in the rapidly flowing (flow rate, 37.85 liters/min) fully oxygenated upper outflow channel of Octopus Spring. Growth as motile rods or in an attached form allows Thermocrinis ruber to alternate in nature between different states, each of which is optimal for a different set of environmental conditions (19).

Filamentous streamers appear to be widely distributed in terrestrial hot springs. In the volcanic Hveragerthi area of Iceland, we observed greyish filaments at temperatures up to 88°C, which turned out to be composed of members of Aquificales, as determined by in situ hybridization. Cultivation attempts resulted in a pure culture, which grew at temperatures up to 89°C. An additional hyperthermophilic bacterial isolate was obtained by us recently (data not shown) from greyish cell masses (original temperature 75 to 80°C) obtained in the Uzon Valley, Kamchatka (Russia). Interestingly, both isolates exhibited close phylogenetic relationships to Thermocrinis ruber and most likely represent additional species in the new genus. In addition, hot ponds not containing visible streamers (e.g., Hveragerthi, Graendalur, Nesjavellir) gave rise to Thermocrinis cultures (data not shown), indicating that Thermocrinis strains, some of which are able to form streamers, may play an important role in general in high-temperature ecosystems at neutral to slightly alkaline pH values.

Description of the genus Thermocrinis.

Thermocrinis gen. nov. (Ther.mo.cri′nis. Gr. fem. n. therme, heat; L. masc. n. crinis, hair; M.L. n. Thermocrinis, hot hair). Cells are gram-negative rods that occur singly, in pairs, and in aggregates. Long filaments are formed in a permanent flow of medium. Cells grow on solid surfaces. No spores are formed. Pure cultures can be obtained by selected cell cultivation. Growth occurs at temperatures up to 89°C and at salinities up to 0.4% NaCl. Aerobic. Chemolithoautotrophic or chemoorganoheterotrophic growth. meso-Diaminopimelic acid is present. The DNA base composition is about 47.5 mol% G+C. As determined by 16S rRNA analysis, the genus Thermocrinis is a new genus belonging to the order Aquificales. Habitat: solfataric hot spring. The type species is Thermocrinis ruber.

Description of Thermocrinis ruber.

Thermocrinis ruber sp. nov. (ru′ber. M.L. masc. n. ruber, red, referring to the cell color). Rod-shaped cells are usually between 1 and 3 μm long and 0.4 μm wide. Spores are not formed. Motile by means of monopolar polytrichous flagella. Cells occur singly, in pairs, and in aggregates consisting of four to several hundred individuals. In a permanent flow of medium, cells grow predominantly as long filaments, forming visible pink cell masses. Growth occurs on solid surfaces such as silicon-coated cover glasses, cotton, or muscovite glimmer. Round, brownish red colonies about 1 mm in diameter are formed on Gelrite plates. The cell envelope consists of an 8-nm-wide cytoplasmic membrane and a 25- to 30-nm-wide cell wall, including an 8-nm-wide outer membrane. There is no evidence of a regularly arrayed surface layer protein. Growth occurs at temperatures between 44 and 89°C (optimum temperature, 80°C) and at salinities ranging from 0 to 0.4% NaCl. Growth occurs at pH 7 and 8.5. The optimal doubling time is 70 min. Aerobic. Molecular hydrogen, thiosulfate, elemental sulfur, formate, and formamide serve as electron donors, and oxygen serves as an electron acceptor. CO2, formate, and formamide are used as carbon sources. Ammonia is formed from formamide. meso-Diaminopimelic acid is present. Catalase positive. The G+C content is 47.2 mol% as determined by the thermal denaturation method and 47.8 mol% as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. The evolutionary distances to Aquifex pyrophilus and H. thermophilus are 12.5 and 6.8%, respectively. The type strain is Thermocrinis ruber OC 1/4 (= DSM 12173 [Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen, Braunschweig, Germany]), which was isolated from pink filaments obtained from Octopus Spring in the White Creek area of Yellowstone National Park, Wyo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Hummel, T. Hader, and S. Dobler for technical assistance and C. Horn for computer help. Furthermore, we are indebted to the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service for a sampling permit and to B. Lindstrom for field assistance.

This work was financially supported by grant Ste297/10 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, by the Diversa Corporation, and by the Fond der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfredsson G A, Ingason A, Kristjansson J K. Growth of thermophilic obligately autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria on thiosulfate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1986;2:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aragno M. Thermophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing (Knallgas) bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 3917–3933. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balch W E, Fox G E, Magrum L J, Woese C R, Wolfe R S. Methanogens: reevaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:260–296. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.2.260-296.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauman A J, Simmonds P G. Fatty acids and polar lipids of extremely thermophilic filamentous bacterial masses from two Yellowstone hot springs. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:528–531. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.2.528-531.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck P, Huber R. Detection of cell viability in cultures of hyperthermophiles. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;147:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beffa T, Blanc M, Aragno M. Obligately and facultatively autotrophic, sulfur- and hydrogen-oxidizing thermophilic bacteria isolated from hot composts. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonjour F, Aragno M. Growth of thermophilic, obligatorily chemolithoautotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria related to Hydrogenobacter with thiosulfate and elemental sulfur as electron and energy source. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;35:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock T D. Life at high temperatures. Science. 1967;158:1012–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3804.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brock T D. Thermophilic microorganisms and life at high temperatures. New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock T D. The road to Yellowstone and beyond. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock T D. Early days in Yellowstone microbiology. ASM News. 1998;64:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brosius J, Dull T J, Sleeter D D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burggraf S, Fricke H, Neuner A, Kristjansson J, Rouvier P, Mandelco L, Woese C R, Stetter K O. Methanococcus igneus sp. nov., a novel hyperthermophilic methanogen from a shallow submarine hydrothermal system. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burggraf S, Huber H, Stetter K O. Reclassification of the crenarchaeal orders and families in accordance with 16S rRNA sequence data. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:657–660. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burggraf S, Mayer T, Amann R I, Schadhauser S, Woese C R, Stetter K O. Identifying members of the domain Archaea with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3112–3119. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3112-3119.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burggraf S, Olsen G J, Stetter K O, Woese C R. A phylogenetic analysis of Aquifex pyrophilus. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:352–356. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deckert G, Warren P V, Gaasterland T, Young W G, Lenox A L, Graham D E, Overbeek R, Snead M A, Keller M, Aujay M, Huber R, Feldman R A, Short J M, Olsen G J, Swanson R V. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature. 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dworkin M. Prokaryotic life cycles. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber R, Burggraf S, Mayer T, Barns S M, Rossnagel P, Stetter K O. Isolation of a hyperthermophilic archaeum predicted by in situ RNA analysis. Nature. 1995;376:57–58. doi: 10.1038/376057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huber R, Langworthy T A, König H, Thomm M, Woese C R, Sleytr U B, Stetter K O. Thermotoga maritima sp. nov. represents a new genus of unique extremely thermophilic eubacteria growing up to 90°C. Arch Microbiol. 1986;144:324–333. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber R, Rossnagel P, Woese C R, Rachel R, Langworthy T A, Stetter K O. Formation of ammonium from nitrate during chemolithoautotrophic growth of the extremely thermophilic bacterium Ammonifex degensii gen. nov. sp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:40–49. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(96)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber R, Wilharm T, Huber D, Trincone A, Burggraf S, König H, Rachel R, Rockinger I, Fricke H, Stetter K O. Aquifex pyrophilus gen. nov. sp. nov., represents a novel group of marine hyperthermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:340–351. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawasumi T, Igarashi Y, Kodama T, Minoda T. Isolation of strictly thermophilic and obligately autotrophic hydrogen bacteria. Agric Biol Chem. 1980;44:1985–1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawasumi T, Igarashi Y, Kodama T, Minoda Y. Hydrogenobacter thermophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kristjansson K J, Ingason A, Alfredsson G A. Isolation of thermophilic obligately autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria, similar to Hydrogenobacter thermophilus, from Icelandic hot springs. Arch Microbiol. 1985;140:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kryukov V R, Savelyeva N D, Pusheva M A. Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum nov. gen., nov. sp., an extreme thermophilic bacterium, and its hydrogenase activity. Microbiologiya. 1983;52:781–788. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurr M, Huber R, König H, Jannasch H W, Fricke H, Trincone A, Kristjansson J K, Stetter K O. Methanopyrus kandleri, gen. and sp. nov. represents a novel group of hyperthermophilic methanogens, growing at 110°C. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauerer G, Kristjansson J K, Langworthy T A, König H, Stetter K O. Methanothermus sociabilis sp. nov., a second species within the Methanothermaceae growing at 97°C. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1986;8:100–105. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludvik J, Benada O, Mikulik K. Ultrastructure of an extreme thermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig W, Strunk O. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. 1996. http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB/documentation/arb.ps http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB/documentation/arb.ps. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J, Woese C R. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:82–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marmur J, Doty P. Determination of the base composition of desoxyribonucleic acid from its thermal denaturation temperature. J Mol Biol. 1962;5:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(62)80066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishihara H, Igarashi Y, Kodama T. A new isolate of Hydrogenobacter, an obligately chemolithoautotrophic, thermophilic, halophilic and aerobic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium from seaside saline hot spring. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:294–298. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palleroni N J. Prokaryotic diversity and the importance of culturing. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1997;72:3–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1000394109961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitulle C, Yang Y, Marchiani M, Moore E R B, Siefert J L, Aragno M, Jurtshuk P, Jr, Fox G E. Phylogenetic position of the genus Hydrogenobacter. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:620–626. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reysenbach A L, Whickham G S, Pace N R. Phylogenetic analysis of the hyperthermophilic pink filament community in Octopus Spring, Yellowstone National Park. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2113–2119. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.2113-2119.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhuland L E, Work E, Denman R F, Hoare D S. The behaviour of the isomers of α,ɛ-diaminopimelic acid on paper chromatograms. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:4844–4846. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rieger G, Müller K, Hermann R, Stetter K O, Rachel R. Cultivation of hyperthermophilic archaea in capillary tubes resulting in improved preservation of fine structures. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz G E. Porins: general to specific, native to engineered passive pores. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:485–490. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stahl D A, Lane D J, Olsen G J, Pace N R. Characterization of a Yellowstone hot spring microbial community by 5S rRNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1379–1384. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.6.1379-1384.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stetter K O. Ultrathin mycelia-forming organisms from submarine volcanic areas having an optimum growth temperature of 105°C. Nature. 1982;300:258–260. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stetter K O. Life at the upper temperature border. In: Tran Than Van J and K, Mounolou J C, Schneider J, McKay C., editors. Colloque Interdisciplinaire du Comité National de la Recherche Scientifique. Frontiers of Life, C55. Gif-sur-Yvette, France: Editions Frontières; 1992. pp. 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Völkl P, Huber R, Drobner E, Rachel R, Burggraf S, Trincone A, Stetter K O. Pyrobaculum aerophilum sp. nov., a novel nitrate-reducing hyperthermophilic archaeum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2918–2926. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2918-2926.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]