Abstract

With continuous advances in medicine, patients are faced with several medical or surgical treatment options for their health conditions. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients navigate these options and choose based on their goals and values. We reviewed the literature to identify decision aids and better understand the effect on patient decision-making. We identified 107 decision aids designed to help patients make decisions between medical treatment or screening options; 39 decision aids were used to help patients choose between a medical and surgical treatment, and five were identified that aided patients in deciding between a major open surgical procedure and a less invasive option. Many of the decision aids were used to help patients decide between prostate, colorectal, and breast cancer screening or treatment options. Although most decision aids were not associated with a significant effect on the actual decision made, they were largely associated with increased patient knowledge, decreased decisional conflict, more accurate perception of risks, increased satisfaction with their decision, and no increase in anxiety surrounding their decision. These data identify a gap in use of decision aids in surgical decision-making and highlight the potential to help surgical patients make value-based, knowledgeable decisions regarding their treatment.

Keywords: Decision aid, Decision tool, Surgical decision, Surgical decision-making, Shared decision-making

Introduction

Making decisions between competing medical treatment options is difficult for both patients and providers.1 Historically, a paternalistic approach has been applied, whereby patients deferred the decision to the treating provider. However, this approach fails to consider patient preferences, values, and belief systems.2 Efforts to engage patients in making their own medical decisions rely on empowering patients with education and the necessary tools,3 as patients desire more information about treatment options and want to participate in the decision-making process.4–6 As the number of possible treatment options has increased exponentially, patient involvement in decision-making has simultaneously become more important and more challenging. For patients choosing between two treatments, especially surgical options, providers must ensure that patients correctly estimate both benefits and harms of any particular treatment.7

Decision aids have emerged as an effective means of providing information to patients, improving their knowledge, decreasing their decisional conflict, and standardizing the transmission of information from provider to patient.8,9 Despite these documented benefits, there has been relatively few applications of decision aids to surgical practice.10 Current decision aids that do incorporate surgical options primarily focus on the choice between surgery and watchful waiting.9 However, there are situations in which the decision to be made is one surgical option versus another. For instance, a patient with large abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) must consider the benefits and harms of undergoing an endovascular repair versus an open surgical repair.11 The patient must weight these two options within the context of other comorbid conditions that may be present, and they must understand how their comorbidities may impact the postoperative course.12 Decision aids directed at patients facing these challenging situations may allow for better alignment of patient preferences and expectations with the surgical treatment delivered.

The objective of this article was to review published medical and surgical decision aids to highlight the disparity in decision aids used in surgical versus medical decision-making and to identify the utility in using decision aids to improve patient outcomes with the goal of using this information to inform future practice in surgical decision-making. This was done by analyzing three mutually exclusive groups of decision aids, those considering medical (nonsurgical) decisions, those considering medical versus surgical interventions, and those considering two or more surgical interventions.

Methods

Study identification

We reviewed all randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) that studied the use of decision aids in medical decision-making as identified by the Cochrane collaboration in their systematic reviews published in 2014 and 2017 (n = 133).13,14 We then performed a MEDLINE search using the terms “decision aid” and “surg” to ensure that we included any additional decision aids evaluated that were not included in the Cochrane review. The search was limited to RCTs from 2015 to 2017 that included use of a decision aid or decision tool. This search resulted in 18 additional studies not included in either Cochrane review.

We categorized the decision aids into three distinct groups based on the type of decision they were designed for: (1) choosing between medical (nonsurgical) options, (2) choosing between a medical and a surgical option, (3) choosing between a minimally invasive and major surgical option, and (4) choosing between a minimally invasive and major surgical option for patients with complex comorbidities, defined as choosing between nonelective surgical treatment options for patients with severe comorbidities that factor into decision-making.

Study outcomes assessed

We evaluated all outcomes measured in each of the studies. We paid specific attention to studies that measured the effect of the decision aid on the ultimate decision that was made by the patient, as well as the effect on patient-centered factors surrounding the decision. We categorized these patient factors into five domains: (1) patient knowledge of the condition or decision, (2) patient perception of risks related to the decision, (3) patient decisional conflict, (4) patient satisfaction with the decision aid and/or decision made, (5) and patient anxiety related to the decision. These five domains were defined by two of the study authors (KL, JC) in concordance with the study outcomes assessed in the majority of the research papers included in this review. These were adjudicated by review of the remaining authors.

Results

Summary of studies of decision aids

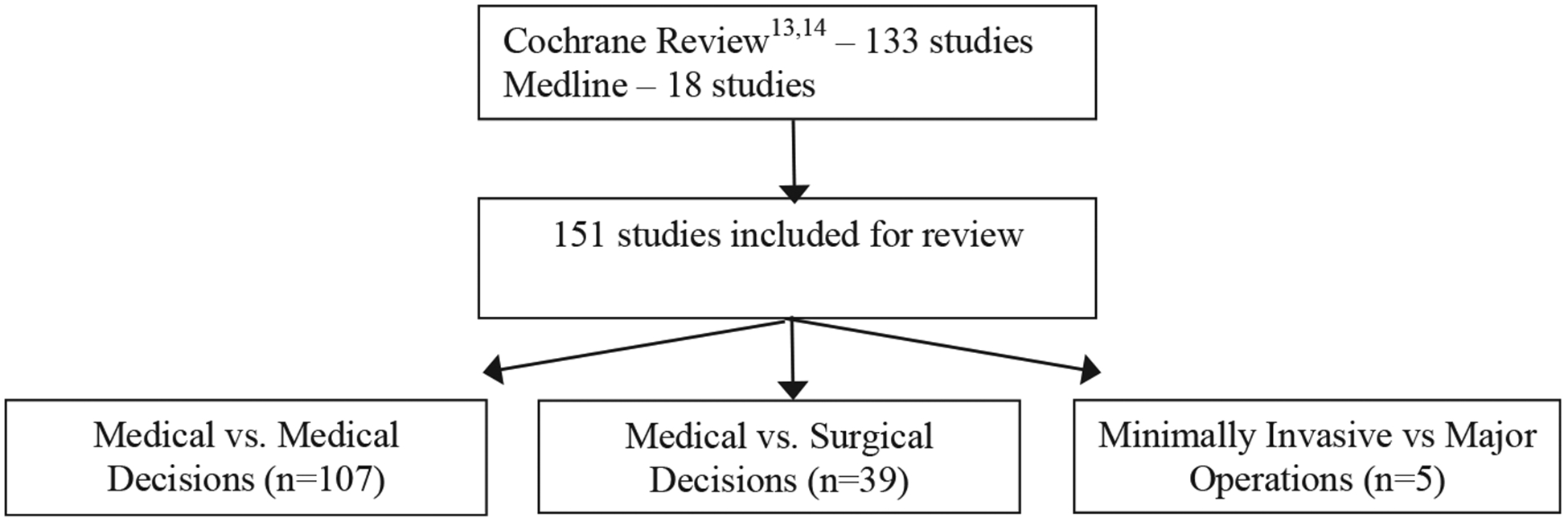

We identified 151 studies that evaluated the use of a decision aid for patients facing a treatment choice. We categorized these into three groups: the first group consisted of 107 studies that evaluated decision aids for patients choosing between two medical treatments or screening options, the second group consisted of 39 studies that evaluated decision aids for patients choosing between a medical and surgical treatment option, and the third group had five studies that examined the utility of decision aids to assist patients in choosing between two surgical options (Fig. 1). We did not identify any decision aids that were designed to help patients with complex comorbid conditions choose between two types of surgical interventions.

Fig. 1 -. Study flow diagram.

We further categorized each type of decision aid by medical condition (Table 1). Among decision aids designed for choosing between medical decisions, most were designed for patients with either screening for or genetic testing for the following conditions: prostate conditions (n = 18),15–32 cardiovascular disease (n = 11),33–43 colorectal cancer (n = 14),44–57 breast cancer (n = 13),58–70 endocrine disorders (n = 11),1,71–80 and women’s health conditions (n = 10).81–90 Few studies assessed decision aids for medical decisions in other categories such as screening for congenital disorders,91–97 infectious diseases,98–102 orthopedic conditions,103–106 diabetes,107–112 psychiatric conditions,113–115 neurologic conditions,116,117 dental health conditions,118,119 and health behaviors.120 Among those designed for choosing between a medical and surgical interventions, most were targeted toward patients with breast cancer (n = 9),121–129 orthopedic conditions (n = 9),130–138 prostate conditions (n = 8),139–146 and women’s health conditions (n = 6),147–152 whereas few assessed decisions regarding cardiovascular conditions,153–155 vasectomy,156 obesity,157 pulmonary conditions,158 and end-of-life care.159 Among the five decision aids that were designed to help patients choose between two surgical options, three were targeted toward patients with breast cancer,3,160,161 one was designed for patients with prostate cancer,162 and one was for patients with appendicitis.163

Table 1 -.

Number of decision aids addressing each condition.

| Condition type | Medical versus medical (n = 107) | Medical versus surgical (n = 39) | Minimally invasive versus major operations (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate conditions | 18 | 8 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 11 | 3 | - |

| Colorectal cancer | 14 | - | - |

| Breast cancer | 13 | 9 | 3 |

| Women’s health | 10 | 6 | - |

| Endocrine disorders | 11 | - | - |

| Congenital disorders | 7 | - | - |

| Infectious diseases | 5 | - | - |

| Orthopedic conditions | 4 | 9 | - |

| Diabetes | 6 | - | - |

| Psychiatric conditions | 3 | - | - |

| Neurologic conditions | 2 | - | - |

| Dental conditions | 2 | - | - |

| Health behaviors | 1 | - | - |

| Vasectomy | - | 1 | - |

| Acute appendicitis | - | - | 1 |

| Obesity | - | 1 | - |

| Pulmonary disorders | - | 1 | - |

| End-of-life care | - | 1 | - |

Domains assessed in the decision aids by decision aid type

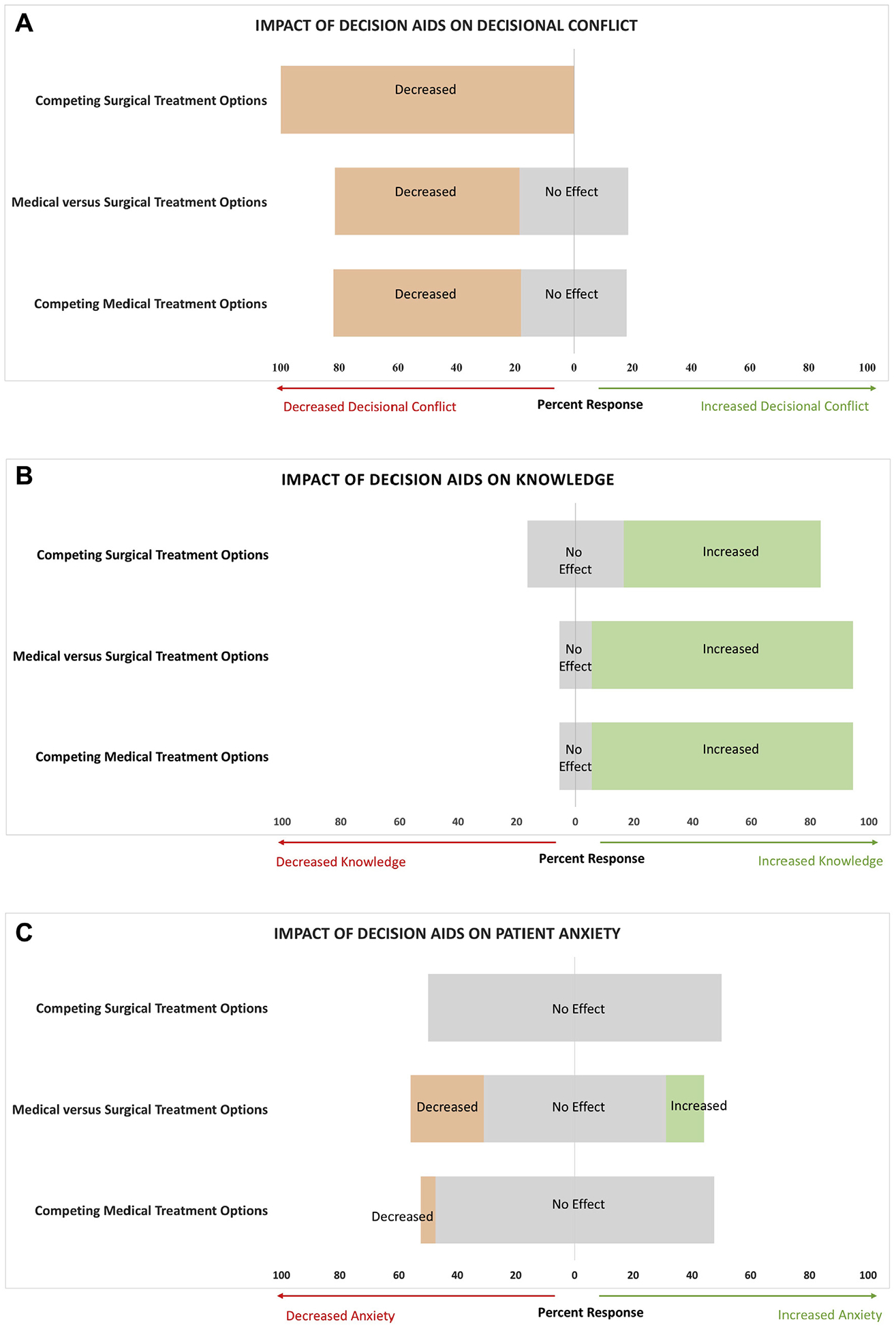

We categorized studies that assessed the efficacy of the decision aids in the five aforementioned patient-centered domains (knowledge, perception of risks, decisional conflict, satisfaction, and anxiety related to the decision, Tables 2–4, Fig. 2).

Table 2 -.

All studies that evaluated decision aids designed for deciding between two or more medical (nonsurgery) treatments/screening options, by year and outcomes measured.

| Medical versus medical decisions (n = 107) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Decision | Authors | Outcomes measured | |||||

| Knowledge | Perceived risk | Decisionalconflict | Satisfaction | Anxiety | Other | |||

| Breast cancer | Genetic testing | Lerman, 1997 | √ | √ | ||||

| Green, 2001 | √ | |||||||

| Green, 2004 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Miller, 2005 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Schwartz, 2001 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Wakefield, 2008a | √ | |||||||

| Wakefield, 2008b | √ | |||||||

| Mammogram | Mathieu, 2007 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Mathieu, 2010 | √ | |||||||

| Baena-Canada, 2015 | √ | |||||||

| Tamoxifen treatment | Fagerlin, 2011 | √ | √ | |||||

| Ozanne, 2007 | √ | |||||||

| Chemotherapy | Whelan, 2003 | √ | √ | |||||

| Colorectal cancer | Screening | Dolan, 2002 | √ | √ | ||||

| Lewis, 2010 | √ | |||||||

| Miller, 2011 | √ | |||||||

| Pignone, 2000 | √ | |||||||

| Ruffin, 2007 | √ | |||||||

| Schroy, 2011 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Smith, 2010 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Steckelberg, 2011 | √ | |||||||

| Trevena, 2008 | √ | |||||||

| Wakefield, 2008 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Wolf, 2000 | √ | |||||||

| Ferron, 2015 | √ | |||||||

| Schroy, 2016 | √ | |||||||

| Chemotherapy | Leighl, 2011 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Congenital disorders | Prenatal testing | Bekker, 2004 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Bjorklund, 2012 | √ | |||||||

| Kuppermann, 2009 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Kuppermann, 2014 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Nagle, 2008 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Hunter, 2005 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Leung, 2004 | √ | |||||||

| Dental conditions | Dental treatment | Johnson, 2006 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Kupke, 2003 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Diabetes | Medication | Mann D, 2010 | √ | √ | ||||

| Weymiller, 2007 | √ | |||||||

| Mullan, 2009 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Mathers, 2012 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Screening | Mann E, 2010 | √ | ||||||

| Lifestyle modifications | Marteau, 2010 | √ | ||||||

| Health behaviors | Smoking cessation | Warner, 2015 | √ | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | Stress testing | Hess, 2012 | √ | |||||

| Prevention of cardiovascular disease | Lalonde, 2006 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Sheridan, 2006 | √ | |||||||

| Sheridan, 2011 | √ | |||||||

| Preoperative autologous blood donation | Laupacis, 2006 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation | Man-Song-Hing, 1999 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| McAlister, 2005 | √ | |||||||

| Thomson, 2007 | √ | |||||||

| Fraenkel, 2012 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Hypertension treatment | Montgomery, 2003 | √ | ||||||

| Angiography access | Schwalm, 2012 | √ | √ | |||||

| Endocrine disorders | Hormone replacement therapy | Deschamps, 2004 | √ | √ | ||||

| Dodin, 2001 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Legare, 2003 | √ | |||||||

| McBride, 2002 | √ | |||||||

| Murray, 2001 | √ | √ | ||||||

| O’Connor, 1998 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| O’Connor, 1999 | √ | |||||||

| Rostom, 2002 | √ | |||||||

| Rothert, 1997 | √ | |||||||

| Schapira, 2007 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Thyroid cancer | Sawka, 2012 | √ | √ | |||||

| Infectious diseases | Vaccinations | Chambers, 2012 | √ | |||||

| Clancy, 1988 | √ | |||||||

| Shourie, 2013 | √ | |||||||

| Antibiotics for respiratory infections | Legare, 2011 | √ | ||||||

| Legare, 2012 | √ | |||||||

| Neurologic conditions | Feeding in dementia | Hanson, 2011 | √ | √ | ||||

| Immunotherapy for multiple sclerosis | Kasper, 2008 | √ | ||||||

| Orthopedic conditions | Osteoarthritis | Fraenkel, 2007 | √ | |||||

| Osteoporosis | Montori, 2011 | √ | ||||||

| LeBlanc, 2015 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Bisphosphonates use | Oakley, 2006 | √ | ||||||

| Prostate conditions | Prostate cancer screening | Allen, 2010 | √ | √ | ||||

| Evans, 2010 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Frosch, 2008 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Gattellari, 2003 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Gattellari, 2005 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Krist, 2007 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Lepore, 2012 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Myers, 2005 | √ | |||||||

| Myers, 2011 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Partin, 2004 | √ | |||||||

| Rubel, 2010 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Schapira, 2000 | √ | |||||||

| Taylor, 2006 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Volk, 1999 | √ | |||||||

| Volk, 2008 | √ | |||||||

| Watson, 2006 | √ | |||||||

| Williams, 2013 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Wolf, 1996 | √ | |||||||

| Psychiatric conditions | Treatment of schizophrenia | Hamann, 2006 | √ | |||||

| Treatment of depression | Loh, 2007 | √ | ||||||

| Treatment of PTSD | Mott, 2014 | √ | ||||||

| Women’s health | Contraceptives after abortion | Langston, 2010 | √ | |||||

| Natural health products in menopause | Legare, 2008 | √ | √ | |||||

| Management of abnormal cervical smear | McCaffery, 2010 | √ | ||||||

| Delivery post caesarian section | Montgomery, 2007 | √ | ||||||

| Eden, 2014 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Management of breech presentation | Nassar, 2007 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Management of menorrhagia | Protheroe, 2007 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Labor analgesia | Raynes-Greenow, 2010 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Ovarian cancer risk management | Tiller, 2006 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Number of embryos implanted in IVF | Van Peperstraten, 2010 | √ | √ | |||||

Table 4 -.

All studies that evaluated decision aids designed for deciding between two surgical treatment options, by year and outcomes measured.

| Minimally invasive uersus major operations (n = 5) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Decision | Authors | Outcomes measured | |||||

| Knowledge | Perceived risk | Decisional conflict | Satisfaction | Anxiety | Other | |||

| Breast cancer | Breast-conserving surgery uersus total mastectomy | Goel, 2001 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Jibaja-Weiss, 2011 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Whelan, 2004 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Acute appendicitis | Open uersus laparoscopic appendectomy | Russell, 2015 | √ | |||||

| Prostate conditions | Radical prostatectomy uersus orchiectomy uersus medical management | Auvinen, 2004 | √ | |||||

Fig. 2 -. Impact of decision aids on five patient-centered domains: (A) decisional conflict, (B) knowledge, (C) anxiety, (D) satisfaction, and (E) perception of risk. (Color version of figure is available online.).

Domain 1-knowledge

The effect of the decision aid on patient knowledge was assessed in 58% (87/151) of all studied decision aids. The majority reported a significant increase in patient knowledge related to choosing between medical decisions (89%, 58/65). This finding of enhanced patient knowledge was also noted in studies that examined decision aids for medical versus surgical decision (89%, 17/19) and for those designed to assist in deciding between two surgical options (67%, 2/3).

Domain 2-perception of risk

The perception of risk was assessed by 14% (21/151) of all studied decision aids. Studies that assessed this domain found that patients had a more accurate perception of the risks associated with their medical treatment after decision aid use (83%, 15/18). This finding was consistent among studies that assessed risk perception in medical versus surgical decision-making (67%, 2/3). No studies that evaluated decision aids for deciding between two surgical interventions examined patient risk perception.

Domain 3-ecisional conflict

Decisional conflict was assessed by 43% (65/151) of studies. Most decision aids designed for medical decisions reported significantly decreased patient decisional conflict (64%, 30/47), whereas the remaining studies reported no significant effect (36%, 17/47). Decreased decisional conflict was also found among studies that evaluated decision aids designed for choosing between a medical versus surgical option (63%, 10/16) and those designed for choosing between two surgical options (100%, 2/2).

Domain 4-patient satisfaction

Few studies assessed patient satisfaction with the decision-making process (22%, 33/151). However, most studies assessing this outcome found that patients using the medical decision aid had a higher level of satisfaction with the decision-making process after using the aid (67%, 12/18). Patients who were choosing between a medical versus surgical intervention (46%, 6/13) or choosing between two types of surgical interventions (50%, 1/2) also reported significantly increased patient satisfaction.

Domain 5-patient anxiety

Patient anxiety was assessed by only 19% (28/151) of studies. All studies showed either a significant decrease or no significant increase in patient anxiety surrounding the decision-making process or the decision itself. All decision aids that were designed for choosing between two types of medical decisions demonstrated decreased (5%, 1/19) or no significant increase (95%, 18/19) in patient anxiety. For decision aids that were designed for choosing between a medical and surgical intervention, many studies were associated with a significant decrease (25%, 2/8) or no significant increase (63%, 5/8), whereas one study showed a significant increase in patient anxiety after using the decision aid. Only one study assessed patient anxiety related to a decision aid designed for choosing between two surgical interventions, and that study found no significant increase in patient anxiety.

Impact of the decision aid on study outcomes by decision aid type

We next identified studies that assessed the impact of the decision aid on the actual decision made by the patient (Table 5). Of the 78% (83/107) of studies that assessed impact of the decision aid on the medical decisions made by the patient, 20% (17/83) demonstrated that the decision aid was associated with greater utilization or preference of one of the medical options; 22% (18/83) were associated with decreased utilization or preference; and 58% (48/83) of the decision aids were not associated with a significant impact on the decision made by the patient.

Table 5 -.

Number studies that assessed the impact of the decision aid on the decision.

| Study characteristic | Medical versus medical (n = 107) | Medical versus surgical (n = 39) | Minimally invasive versus major operations (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluated the decision, n (%) | 83 (78) | 26 (67) | 5 (100.0) |

| Greater utilization/preference for medical option (or minimally invasive option), n (%) | 17 (20) | 3 (12) | 1 (20) |

| Lower utilization of medical option (or preference for major operation), n (%) | 18 (22) | 4(15) | 3(60) |

| No impact on decision | 48 (58) | 19 (73) | 1 (20) |

Findings were similar among decision aids designed for choosing between a medical versus surgical intervention. Of the 67% (26/39) of studies that assessed the impact of the decision aid on the decision made, 73% (19/26) documented that the decision aid had no impact on the ultimate choice made by the patient, and 12% (3/26) and 15% (4/26) of studies were associated with increased preference for medical versus increased preference for surgical option, respectively.

All five studies that used decision aids to assist patients in choosing between two surgical interventions assessed the impact of the aid on the decision made by the patient. Almost all of these studies reported that the decision aid had a significant impact on which surgical intervention was chosen by the patient, with one favoring minimally invasive surgery, and three favoring major open surgery, and the remaining study reported no significant impact.

Discussion

After reviewing 151 randomized-controlled trials on the use of decision aids to assist patients in choosing between medical and surgical treatments, we identified a gap in the use of decision aids for surgical decision-making. The majority of decision aids were designed to assist patients choose between two or more types medical interventions (n = 107), with a smaller group aimed at assisting patients choose between a medical and surgical intervention (n = 39). Only five decision aids were identified that were specifically designed for patients choosing between two surgical options, namely deciding between a major operation and a minimally invasive procedure. However, no decision aids were available to assist patients with complex comorbid conditions attempting to navigate the choice between competing surgical treatment options. We believe that this gap represents an opportunity to develop decision aids for this particular group of patients, as they may benefit substantially from additional help in making challenging treatment decisions.

Many of the decision aids that we identified focused on decisions surrounding cancer screening and care. Specifically, genetic testing for breast cancer and screening for prostate cancer or colorectal cancer were among the most commonly studied medical decision aids.15–32,44–70 In addition, many of the decision aids designed for patients choosing between medical and surgical treatments also focused on oncologic decisions such as radiation versus radical prostatectomy for men with prostate cancer or mastectomy versus watchful waiting for women with genetic risk factors for breast cancer.121–129,139–146 This focus on cancer care was also present among decision aids designed for deciding between two surgical options.3,160–162 Multiple studies sought to help with the decision between breast-conserving surgery versus total mastectomy for women with breast cancer.3,160–162 Decision aids in cancer care help patients make difficult decisions where a “right” answer often does not exist, and therefore choices must be governed by individualized patient values. Similarly, there are difficult surgical treatment decisions to make with patients who have complex comorbidities. The added challenge of comorbid conditions and the resultant balance between risk and benefit for two surgical interventions must incorporate patient-specific values for the most appropriate treatment choice to be made.

Recent evidence has shown that many difficult medical decisions are deemed “preference-sensitive,” and the ultimate choice depends on each patient’s feelings, values, and their perceptions of the risks and benefits of each treatment option.2 Many of the decision aids identified in this review were associated with significantly increased patient knowledge, increased satisfaction with the decision and decision-making process, a more accurate perception of the risks, no difference in patient anxiety, and decreased decisional conflict. Interestingly, most of the decision aids were not associated with a significant effect on the actual treatment decision made by the patient. While it seems evident that decision aids may provide knowledge to patients, it still remains unclear exactly what influences decisions for patients facing surgery. Moreover, challenges remain as to how surgeons can best help patients align their decisions with their personal values. We advocate for the utility of decision aids in helping patients with complex comorbidities choose between surgical treatment options that more closely align with their personal values to ultimately improve patient satisfaction and outcomes.

It is worth noting, however, that of the five surgical decision aids, three demonstrated that patients were more likely to choose a major operation over a minimally invasive procedure. Specifically, one study showed that women were more likely to choose mastectomy over breast-conserving surgery,3 another demonstrated that parents were more likely to choose open appendectomy than laparoscopic surgery for their children,163 and men were more likely to choose radical prostatectomy over orchiectomy and medical management for prostate cancer after decision aid use.162 Conversely, the two remaining studies found that women were more likely to choose breast-conserving surgery over mastectomy161 or demonstrated no difference in breast cancer treatment choice.160 With these data, we conjecture that decision aids may be useful in elucidating factors that drive patients to choose certain treatments, such as financial concerns, surgical outcomes, recurrence risk, or aesthetic or functional concerns.

Our study has limitations. Although we included a broad array of studies, it is possible that some decision aids may have been missed by our search strategy. In addition, differences in the outcomes evaluated precluded the ability to perform formal meta-analyses and express measures of heterogeneity. The small sample size of surgical decision aids (n = 5) in our review limits our ability to draw significant generalizations. However, we believe that this small number highlights the opportunity to increase the utilization of decision aids in surgical practice. Furthermore, we believe that the data gained from this review can provide insight into the utility of decision aids in future surgical practice and may improve patient outcomes by promoting decision-making in congruence with patient values.

Conclusions

Decision aids are a commonly utilized tool in helping patients make the best decisions about their health care, and these tools have been used most widely in studies examining two or more medical treatments and those examining medical versus surgical treatments. However, decision aids designed to assist patients in choosing between competing surgical interventions remain less common and represents an important pathway forward in helping patients make the best quality decisions related to their surgical care.

Table 3 -.

All studies that evaluated decision aids designed for deciding between a medical versus surgical treatment options, by year and outcomes measured.

| Medical versus surgical decisions (n = 39) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Decision | Authors | Outcomes measured | |||||

| Knowledge | Perceived risk | Decisional conflict | Satisfaction | Anxiety | Other | |||

| Breast cancer | Breast reconstruction | Heller, 2008 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Lam, 2013 | √ | |||||||

| Causarano, 2015 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Luan, 2016 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Prophylactic mastectomy | Schwartz, 2009 | √ | ||||||

| Van Roosmalen, 2004 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Treatment options | Street, 1995 | √ | ||||||

| Vodermaier, 2009 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Lam, 2014 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | Repair of AAA | Knops, 2014 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Coronary | Bernstein, 1998 | √ | √ | |||||

| revascularization | ||||||||

| Morgan, 2000 | √ | √ | ||||||

| End-of-life care | Curative intent surgery versus noncurative intent treatment | Schubart, 2015 | √ | |||||

| Obesity | Bariatric surgery | Arterburn, 2011 | √ | √ | ||||

| Orthopedic conditions | Management of osteoarthritis | De Achaval, 2012 | √ | |||||

| Veroff, 2013 | √ | |||||||

| Bozic, 2013 | √ | |||||||

| Stacey, 2014 | √ | |||||||

| Stacey, 2015 | √ | |||||||

| Vina, 2016 | √ | |||||||

| Elective spinal | Deyo, 2000 | √ | ||||||

| surgery | ||||||||

| Treatment for spinal | Kearing, 2016 | √ | √ | |||||

| stenosis | ||||||||

| Repair of humerus fractures | Hageman, 2015 | √ | ||||||

| Prostate conditions | Management of BPH | Barry, 1997 | √ | √ | ||||

| Murray, 2001 | √ | √ | ||||||

| Management of prostate cancer | Berry, 2013 | √ | ||||||

| Chabrera, 2015 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Davison, 1997 | √ | |||||||

| Huber, 2013 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Van Tol-Geerdink, 2013 | √ | |||||||

| Van Tol-Geerdink, 2016 | √ | |||||||

| Pulmonary disorders | Lung transplant in cystic fibrosis | Vandemheen, 2009 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Women’s health and vasectomy | Hysterectomy or medical management of menorrhagia | Kennedy, 2002 | √ | |||||

| Vuorma, 2003 | √ | |||||||

| C-section uersus vaginal delivery | Shorten, 2005 | √ | √ | |||||

| Uterine fibroid treatment | Solberg, 2010 | √ | √ | |||||

| Pregnancy termination methods | Wong, 2006 | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Treatment of pelvic organ prolapse | Brazell, 2015 | √ | ||||||

| Vasectomy | Labrecque, 2010 | √ | √ | |||||

Acknowledgment

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed equally to the concept, development, writing and editing of this article. In addition, authors KL and JC contributed significantly to the data collection. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This work was supported by VA HSR&D 015–05 Merit Award (Goodney).

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. BMJ. 1999;319:731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wennberg JE. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. BMJ. 2002;325:961–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulter A Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1997;2:112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton DF, Lane JV, Gaston P, et al. What determines patient satisfaction with surgery? A prospective cohort study of 4709 patients following total joint replacement. BMJ Open. 2013;3:3–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sowden AJ, Forbes C, Entwistle V, Watt I. Informing, communicating and sharing decisions with people who have cancer. Qual Health Care. 2001;10:193–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:274–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelan TJ, Levine MN, Gafni A, et al. Breast irradiation postlumpectomy: development and evaluation of a decision instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3). Cd001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brace C, Schmocker S, Huang H, Victor JC, McLeod RS, Kennedy ED. Physicians’ awareness and attitudes toward decision aids for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2286–2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenhalgh RM, Brown LC, Powell JT, Thompson SG, Epstein D, Sculpher MJ. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1863–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal S, Qamar A, Sharma V, Sharma A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: a comprehensive review. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2011;16:11–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:Cd001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepore SJ, Wolf RL, Basch CE, et al. Informed decision making about prostate cancer testing in predominantly immigrant black men: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor KL, Davis JL, Turner RO, et al. Educating African American men about the prostate cancer screening dilemma: a randomized intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2179–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams RM, Davis KM, Luta G, et al. Fostering informed decisions: a randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of a decision aid among men registered to undergo mass screening for prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen JD, Othus MKD, Hart A, et al. A randomized trial of a computer-tailored decision aid to improve prostate cancer screening decisions: results from the Take the Wheel trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2172–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans R, Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, et al. Supporting informed decision making for prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing on the web: an online randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frosch DL, Bhatnagar V, Tally S, Hamori CJ, Kaplan RM. Internet patient decision support: a randomized controlled trial comparing alternative approaches for men considering prostate cancer screening. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gattellari M, Ward JE. Does evidence-based information about screening for prostate cancer enhance consumer decision-making? A randomised controlled trial. J Med Screen. 2003;10:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattellari M, Ward JE. A community-based randomised controlled trial of three different educational resources for men about prostate cancer screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:168–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krist AH, Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Kerns JW. Patient education on prostate cancer screening and involvement in decision making. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers RE, Daskalakis C, Cocroft J, et al. Preparing African-American men in community primary care practices to decide whether or not to have prostate cancer screening. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:1143–1154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers RE, Daskalakis C, Kunkel EJS, et al. Mediated decision support in prostate cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial of decision counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partin MR, Nelson D, Radosevich D, et al. Randomized trial examining the effect of two prostate cancer screening educational interventions on patient knowledge, preferences, and behaviors. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:835–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubel SK, Miller JW, Stephens RL, et al. Testing the effects of a decision aid for prostate cancer screening. J Health Commun. 2010;15:307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schapira MM, VanRuiswyk J. The effect of an illustrated pamphlet decision-aid on the use of prostate cancer screening tests. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volk RJ, Cass AR, Spann SJ. A randomized controlled trial of shared decision making for prostate cancer screening. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volk RJ, Jibaja-Weiss ML, Hawley ST, et al. Entertainment education for prostate cancer screening: a randomized trial among primary care patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:482–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson E, Hewitson P, Brett J, et al. Informed decision making and prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing for prostate cancer: a randomised controlled trial exploring the impact of a brief patient decision aid on men’s knowledge, attitudes and intention to be tested. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:367–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf AM, Nasser JF, Wolf AM, Schorling JB. The impact of informed consent on patient interest in prostate-specific antigen screening. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1333–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraenkel L, Street RL, Towle V, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a decision support tool to improve the quality of communication and decision-making in individuals with atrial fibrillation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1434–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hess EP, Knoedler MA, Shah ND, et al. The chest pain choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalonde L, O’Connor AM, Duguay P, Brassard J, Drake E, Grover SA. Evaluation of a decision aid and a personal risk profile in community pharmacy for patients considering options to improve cardiovascular health: the OPTIONS pilot study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laupacis A, O’Connor AM, Drake ER, et al. A decision aid for autologous pre-donation in cardiac surgery-a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Connor AM, et al. A patient decision aid regarding antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAlister FA, Man-Son-Hing M, Straus SE, et al. Impact of a patient decision aid on care among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ. 2005;173:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montgomery AA, Fahey T, Peters TJ. A factorial randomised controlled trial of decision analysis and an information video plus leaflet for newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:446–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwalm J-D, Stacey D, Pericak D, Natarajan MK. Radial artery versus femoral artery access options in coronary angiogram procedures: randomized controlled trial of a patient-decision aid. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheridan SL, Shadle J, Simpson RJ, Pignone MP. The impact of a decision aid about heart disease prevention on patients’ discussions with their doctor and their plans for prevention: a pilot randomized trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheridan SL, Draeger LB, Pignone MP, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve use and adherence to effective coronary heart disease prevention strategies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomson RG, Eccles MP, Steen IN, et al. A patient decision aid to support shared decision-making on anti-thrombotic treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation: randomised controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dolan JG, Frisina S. Randomized controlled trial of a patient decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. Med Decis Making. 2002;22:125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leighl NB, Shepherd HL, Butow PN, et al. Supporting treatment decision making in advanced cancer: a randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with advanced colorectal cancer considering chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2077–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis C, Pignone M, Schild LA, et al. Effectiveness of a patient- and practice-level colorectal cancer screening intervention in health plan members: design and baseline findings of the CHOICE trial. Cancer. 2010;116:1664–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller DP, Spangler JG, Case LD, Goff DC, Singh S, Pignone MP. Effectiveness of a web-based colorectal cancer screening patient decision aid: a randomized controlled trial in a mixed-literacy population. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruffin MT, Fetters MD, Jimbo M. Preference-based electronic decision aid to promote colorectal cancer screening: results of a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2007;45:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schroy PC, Emmons K, Peters E, et al. The impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steckelberg A, Hülfenhaus C, Haastert B, Mühlhauser I. Effect of evidence based risk information on “informed choice” in colorectal cancer screening: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trevena LJ, Irwig L, Barratt A. Randomized trial of a self-administered decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen. 2008;15:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wakefield CE, Meiser B, Homewood J, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for individuals considering genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer risk. Cancer. 2008;113:956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolf AM, Schorling JB. Does informed consent alter elderly patients’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening? Results of a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferron P, Asfour SS, Metsch LR, et al. Impact of a multifaceted intervention on promoting adherence to screening colonoscopy among persons in HIV primary care: a pilot study. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8:290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schroy PC, Duhovic E, Chen CA, et al. Risk stratification and shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:526–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL, et al. Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green MJ, McInerney AM, Biesecker BB, Fost N. Education about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: patient preferences for a computer program or genetic counselor. Am J Med Genet. 2001;103:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, et al. Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fagerlin A, Dillard AJ, Smith DM, et al. Women’s interest in taking tamoxifen and raloxifene for breast cancer prevention: response to a tailored decision aid. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:681–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathieu E, Barratt A, Davey HM, McGeechan K, Howard K, Houssami N. Informed choice in mammography screening: a randomized trial of a decision aid for 70-year-old women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2039–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mathieu E, Barratt AL, McGeechan K, Davey HM, Howard K, Houssami N. Helping women make choices about mammography screening: an online randomized trial of a decision aid for 40-year-old women. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller SM, Fleisher L, Roussi P, et al. Facilitating informed decision making about breast cancer risk and genetic counseling among women calling the NCI’s Cancer Information Service. J Health Commun. 2005;10(Suppl 1):119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ozanne EM, Annis C, Adduci K, Showstack J, Esserman L. Pilot trial of a computerized decision aid for breast cancer prevention. Breast J. 2007;13:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwartz MD, Benkendorf J, Lerman C, Isaacs C, Ryan-Robertson A, Johnson L. Impact of educational print materials on knowledge, attitudes, and interest in BRCA1/BRCA2: testing among Ashkenazi Jewish women. Cancer. 2001;92:932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wakefield CE, Meiser B, Homewood J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a decision aid for women considering genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wakefield CE, Meiser B, Homewood J, et al. A randomized trial of a breast/ovarian cancer genetic testing decision aid used as a communication aid during genetic counseling. Psychooncology. 2008;17:844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whelan T, Sawka C, Levine M, et al. Helping patients make informed choices: a randomized trial of a decision aid for adjuvant chemotherapy in lymph node-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baena-Cañada JM, Rosado-Varela P, Expósito-Álvarez I, González-Guerrero M, Nieto-Vera J, Benítez-Rodríguez E. Using an informed consent in mammography screening: a randomized trial. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1923–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sawka AM, Straus S, Rotstein L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a computerized decision aid on adjuvant radioactive iodine treatment for patients with early-stage papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2906–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deschamps MA, Taylor JG, Neubauer SL, Whiting S, Green K. Impact of pharmacist consultation versus a decision aid on decision making regarding hormone replacement therapy. Int J Pharm Pract. 2004:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dodin S, Légaré F, Daudelin G, Tetroe J, O’Connor A. [Making a decision about hormone replacement therapy. A randomized controlled trial]. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:1586–1593. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Légaré F, O’Connor AM, Graham ID, et al. The effect of decision aids on the agreement between women’s and physicians’ decisional conflict about hormone replacement therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McBride CM, Bastian LA, Halabi S, et al. A tailored intervention to aid decision-making about hormone replacement therapy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1112–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, Coulter A, Gray A, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on hormone replacement therapy in primary care. BMJ. 2001;323:490–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, et al. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rostom A, O’Connor A, Tugwell P, Wells G. A randomized trial of a computerized versus an audio-booklet decision aid for women considering post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rothert ML, Holmes-Rovner M, Rovner D, et al. An educational intervention as decision support for menopausal women. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schapira MM, Gilligan MA, McAuliffe T, Garmon G, Carnes M, Nattinger AB. Decision-making at menopause: a randomized controlled trial of a computer-based hormone therapy decision-aid. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Langston AM, Rosario L, Westhoff CL. Structured contraceptive counseling-a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Légaré F, Dodin S, Stacey D, Leblanc A, Tapp S. Patient decision aid on natural health products for menopausal symptoms: randomized controlled trial. Menopause Int. 2008;14:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCaffery KJ, Irwig L, Turner R, et al. Psychosocial outcomes of three triage methods for the management of borderline abnormal cervical smears: an open randomised trial. BMJ. 2010;340:b4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Montgomery AA, Emmett CL, Fahey T, et al. Two decision aids for mode of delivery among women with previous caesarean section: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nassar N, Roberts CL, Raynes-Greenow CH, Barratt A, Peat B, Decision Aid for Breech Presentation Trial C. Evaluation of a decision aid for women with breech presentation at term: a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN14570598]. BJOG. 2007;114:325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Protheroe J, Bower P, Chew-Graham C, Peters TJ, Fahey T. Effectiveness of a computerized decision aid in primary care on decision making and quality of life in menorrhagia: results of the MENTIP randomized controlled trial. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Raynes-Greenow CH, Nassar N, Torvaldsen S, Trevena L, Roberts CL. Assisting informed decision making for labour analgesia: a randomised controlled trial of a decision aid for labour analgesia versus a pamphlet. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tiller K, Meiser B, Gaff C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a decision aid for women at increased risk of ovarian cancer. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van Peperstraten A, Nelen W, Grol R, et al. The effect of a multifaceted empowerment strategy on decision making about the number of embryos transferred in in vitro fertilisation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eden KB, Perrin NA, Vesco KK, Guise J-M. A randomized comparative trial of two decision tools for pregnant women with prior cesareans. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43:568–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuppermann M, Pena S, Bishop JT, et al. Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1210–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bekker HL, Hewison J, Thornton JG. Applying decision analysis to facilitate informed decision making about prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Björklund U, Marsk A, Levin C,Öhman SG. Audiovisual information affects informed choice and experience of information in antenatal Down syndrome screening-a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hunter AGW, Cappelli M, Humphreys L, et al. A randomized trial comparing alternative approaches to prenatal diagnosis counseling in advanced maternal age patients. Clin Genet. 2005;67:303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kuppermann M, Norton ME, Gates E, et al. Computerized prenatal genetic testing decision-assisting tool: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leung KY, Lee CP, Chan HY, Tang MHY, Lam YH, Lee A. Randomised trial comparing an interactive multimedia decision aid with a leaflet and a video to give information about prenatal screening for Down syndrome. Prenatal Diagn. 2004;24:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nagle C, Gunn J, Bell R, et al. Use of a decision aid for prenatal testing of fetal abnormalities to improve women’s informed decision making: a cluster randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN22532458]. BJOG. 2008;115:339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Legare F, Labrecque M, Cauchon M, Castel J, Turcotte S, Grimshaw J. Training family physicians in shared decision-making to reduce the overuse of antibiotics in acute respiratory infections: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ. 2012;184:E726–E734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shourie S, Jackson C, Cheater FM, et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial of a web based decision aid to support parents’ decisions about their child’s Measles Mumps and Rubella (MMR) vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31:6003–6010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chambers LW, Wilson K, Hawken S, et al. Impact of the Ottawa Influenza Decision Aid on healthcare personnel’s influenza immunization decision: a randomized trial. J Hosp Infect. 2012;82:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Clancy CM, Cebul RD, Williams SV. Guiding individual decisions: a randomized, controlled trial of decision analysis. Am J Med. 1988;84:283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Légaré F, Labrecque M, LeBlanc A, et al. Training family physicians in shared decision making for the use of antibiotics for acute respiratory infections: a pilot clustered randomized controlled trial. Health Expect. 2011;14(Suppl 1):96–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.LeBlanc A, Wang AT, Wyatt K, et al. Encounter decision aid vs. clinical decision support or usual care to support patient-centered treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial II. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fraenkel L, Rabidou N, Wittink D, Fried T. Improving informed decision-making for patients with knee pain. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1894–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Montori VM, Shah ND, Pencille LJ, et al. Use of a decision aid to improve treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial. Am J Med. 2011;124:549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Oakley SWT. A pilot study assessing the effectiveness of a decision aid on patient adherence with oral bisphosphonate medication. Pharm J. 2006;276:536–538. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mathers N, Ng CJ, Campbell MJ, Colwell B, Brown I, Bradley A. Clinical effectiveness of a patient decision aid to improve decision quality and glycaemic control in people with diabetes making treatment choices: a cluster randomised controlled trial (PANDAs) in general practice. BMJ Open. 2012;2:2–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mann DM, Ponieman D, Montori VM, Arciniega J, McGinn T. The Statin Choice decision aid in primary care: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mann E, Kellar I, Sutton S, et al. Impact of informed-choice invitations on diabetes screening knowledge, attitude and intentions: an analogue study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Marteau TM, Mann E, Prevost AT, et al. Impact of an informed choice invitation on uptake of screening for diabetes in primary care (DICISION): randomised trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mullan RJ, Montori VM, Shah ND, et al. The diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1560–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Weymiller AJ, Montori VM, Jones LA, et al. Helping patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus make treatment decisions: statin choice randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1076–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mott JM, Stanley MA, Street RL Jr, Grady RH, Teng EJ. Increasing engagement in evidence-based PTSD treatment through shared decision-making: a pilot study. Mil Med. 2014;179:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, Busch R, Kissling W. Shared decision making and long-term outcome in schizophrenia treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, Kriston L, Niebling W, Härter M. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hanson LC, Carey TS, Caprio AJ, et al. Improving decision-making for feeding options in advanced dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2009–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kasper J, Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Nübling M, Heesen C. Informed shared decision making about immunotherapy for patients with multiple sclerosis (ISDIMS): a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1345–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kupke J, Wicht MJ, Stutzer H, Derman SH, Lichtenstein NV, Noack MJ. Does the use of a visualised decision board by undergraduate students during shared decision-making enhance patients’ knowledge and satisfaction? - A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Dent Educ. 2013;17:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Johnson BR, Schwartz A, Goldberg J, Koerber A. A chairside aid for shared decision making in dentistry: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Warner DO, LeBlanc A, Kadimpati S, Vickers KS, Shi Y, Montori VM. Decision aid for cigarette smokers scheduled for elective surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heller L, Parker PA, Youssef A, Miller MJ. Interactive digital education aid in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, DeMarco TA, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction. Health Psychol. 2009;28:11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Street RL, Voigt B, Geyer C, Manning T, Swanson GP. Increasing patient involvement in choosing treatment for early breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;76:2275–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.van Roosmalen MS, Stalmeier PFM, Verhoef LCG, et al. Randomized trial of a shared decision-making intervention consisting of trade-offs and individualized treatment information for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3293–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vodermaier A, Caspari C, Koehm J, Kahlert S, Ditsch N, Untch M. Contextual factors in shared decision making: a randomised controlled trial in women with a strong suspicion of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lam WWT, Chan M, Or A, Kwong A, Suen D, Fielding R. Reducing treatment decision conflict difficulties in breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2879–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Causarano N, Platt J, Baxter NN, et al. Pre-consultation educational group intervention to improve shared decision-making for postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(5):1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lam WWT, Fielding R, Butow P, et al. Decision aids for breast cancer surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(Suppl 7):24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Luan A, Hui KJ, Remington AC, Liu X, Lee GK. Effects of A Novel decision aid for breast reconstruction: a randomized prospective trial. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76(Suppl 3):249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.de Achaval S, Fraenkel L, Volk RJ, Cox V, Suarez-Almazor ME. Impact of educational and patient decision aids on decisional conflict associated with total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Weinstein J, Howe J, Ciol M, Mulley AG. Involving patients in clinical decisions: impact of an interactive video program on use of back surgery. Med Care. 2000;38:959–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Veroff DR, Ochoa-Arvelo T, Venator B. A randomized study of telephonic care support in populations at risk for musculoskeletal preference-sensitive surgeries. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bozic KJ, Belkora J, Chan V, et al. Shared decision making in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Stacey D, Hawker G, Dervin G, et al. Decision aid for patients considering total knee arthroplasty with preference report for surgeons: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hageman MGJS, Jayakumar P, King JD, et al. The factors influencing the decision making of operative treatment for proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Stacey D, Taljaard M, Dervin G, et al. Impact of patient decision aids on appropriate and timely access to hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kearing S, Berg SZ, Lurie JD. Can decision support help patients with spinal Stenosis make a treatment choice?: a prospective study assessing the impact of a patient decision aid and health coaching. Spine. 2016;41:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vina ER, Richardson D, Medvedeva E, Kent Kwoh C, Collier A, Ibrahim SA. Does a patient-centered educational intervention affect African-American access to knee replacement? A randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1755–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chabrera C, Zabalegui A, Bonet M, et al. A decision aid to support informed choices for patients Recently diagnosed with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Barry MJCD, Chang Y, Fowler FJ, Skates S. A randomized trial of a multimedia shared decision-making program for men facing a treatment decision for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Dis Manag Clin Outcomes. 1997;1:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Berry DL, Halpenny B, Hong F, et al. The Personal Patient Profile-Prostate decision support for men with localized prostate cancer: a multi-center randomized trial. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Davison BJ, Degner LF. Empowerment of men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Murray E, Davis H, Tai SS, Coulter A, Gray A, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of an interactive multimedia decision aid on benign prostatic hypertrophy in primary care. BMJ. 2001;323:493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Huber J, Ihrig A, Yass M, et al. Multimedia support for improving preoperative patient education: a randomized controlled trial using the example of radical prostatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.van Tol-Geerdink JJ, Willem Leer J, Weijerman PC, et al. Choice between prostatectomy and radiotherapy when men are eligible for both: a randomized controlled trial of usual care vs decision aid. BJU Int. 2013;111:564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.van Tol-Geerdink JJ, Leer JWH, Wijburg CJ, et al. Does a decision aid for prostate cancer affect different aspects of decisional regret, assessed with new regret scales? A randomized, controlled trial. Health Expect. 2016;19(2):459–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Brazell HD, O’Sullivan DM, Forrest A, Greene JF. Effect of a decision aid on decision making for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Kennedy ADM, Sculpher MJ, Coulter A, et al. Effects of decision aids for menorrhagia on treatment choices, health outcomes, and costs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2701–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shorten A, Shorten B, Keogh J, West S, Morris J. Making choices for childbirth: a randomized controlled trial of a decision-aid for informed birth after cesarean. Birth. 2005;32:252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Sepucha K, et al. Informed choice assistance for women making uterine fibroid treatment decisions: a practical clinical trial. Med Decis Making. 2010;30:444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Vuorma S, Rissanen P, Aalto A-M, Hurskainen R, Kujansuu E, Teperi J. Impact of patient information booklet on treatment decision-a randomized trial among women with heavy menstruation. Health Expect. 2003;6(4):290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wong SSM, Thornton JG, Gbolade B, Bekker HL. A randomised controlled trial of a decision-aid leaflet to facilitate women’s choice between pregnancy termination methods. BJOG. 2006;113:688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Bernstein SJ, Skarupski KA, Grayson CE, Starling MR, Bates ER, Eagle KA. A randomized controlled trial of information-giving to patients referred for coronary angiography: effects on outcomes of care. Health Expect. 1998;1(1):50–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Morgan MW, Deber RB, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an interactive videodisc decision aid for patients with ischemic heart disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:685–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Knops AM, Goossens A, Ubbink DT, et al. A decision aid regarding treatment options for patients with an asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Labrecque M, Paunescu C, Plesu I, Stacey D, Légaré F. Evaluation of the effect of a patient decision aid about vasectomy on the decision-making process: a randomized trial. Contraception. 2010;82(6):556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Arterburn DE, Westbrook EO, Bogart TA, Sepucha KR, Bock SN, Weppner WG. Randomized trial of a video-based patient decision aid for bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:1669–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Vandemheen KL, O’Connor A, Bell SC, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with cystic fibrosis considering lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Schubart JR, Green MJ, Van Scoy LJ, et al. Advanced cancer and end-of-life pcurative intent surgery versus noncurative intent treatment. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:1015–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Goel V, Sawka CA, Thiel EC, Gort EH, O’Connor AM. Randomized trial of a patient decision aid for choice of surgical treatment for breast cancer. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Granchi TS, et al. Entertainment education for breast cancer surgery decisions: a randomized trial among patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Auvinen A, Hakama M, Ala-Opas M, et al. A randomized trial of choice of treatment in prostate cancer: the effect of intervention on the treatment chosen. BJU Int. 2004;93:56. discussion 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Russell KW, Rollins MD, Barnhart DC, et al. Charge awareness affects treatment choice: prospective randomized trial in pediatric appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2015;262:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]