Abstract

We report the synthesis and characterization of two diastereomeric phosphoramidite calix[4]pyrrole cavitands and their corresponding gold(I) complexes, 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl, featuring the metal center directed inward and outward with respect to their aromatic cavity. We studied the catalytic activity of the complexes in the hydration of a series of propargyl esters as the benchmarking reaction. All substrates were equipped with a six-membered ring substituent either lacking or including a polar group featuring different hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) capabilities. We designed the substrates with the polar group to form 1:1 inclusion complexes of different stabilities with the catalysts. In the case of 2in•Au(I)•OTf, the 1:1 complex placed the alkynyl group of the bound substrate close to the metal center. We compared the obtained results with those of a model phosphoramidite gold(I) complex lacking a calix[4]pyrrole cavity. We found that for all catalysts, the presence of an increasingly polar HBA group in the substrate provoked a decrease in the hydration rate constants. We attributed this result to the competing coordination of the HBA group of the substrate for the Au(I) metal center of the catalysts.

Short abstract

We prepare two diastereomeric phosphoramidite calix[4]pyrrole cavitands and their gold(I) complexes featuring the metal center inwardly and outwardly directed with respect to its aromatic cavity. We aim at evaluating the effect of the calix[4]pyrrole cavity in their catalytic performance using as the benchmarking reaction the hydration of alkynes. We equip the substrates with a hydrogen bond acceptor group to form 1:1 complexes featuring the reacting group of the bound substrate (alkyne) close to the metal center.

1. Introduction

The use of supramolecular strategies to increase the rate of chemical transformations and control its selectivity was originally inspired by the mode of action of enzymes.1−4 Enzymes are the most efficient biological catalysts.5 They bind their substrates in active sites by burying most of their surface. The bound substrates are isolated from bulk solvent molecules, confronted with multiple amino acid residues and metal ions, and form the enzyme–substrate complex. The reaction then occurs through a reduction of the transition state free energy in comparison to that in solution. From the different strategies of supramolecular catalysis,6,7 the covalent or supramolecular confinement of gold(I) and other metal catalytic centers in molecular cavities, clefts, and containers by means of the ligand’s residues defining the metal’s second coordination sphere produced relevant results.8−15 A closely related methodology relies on the covalent placement of a catalytic metal center in close proximity to a binding site (Figure 1).16,17

Figure 1.

Cartoon representation of the supramolecular catalysis strategy involving the covalent placement of a catalytic metal center in the proximity of a binding site. The substrate’s binding unit interacts with the supramolecular catalyst’s binding site, placing the reactive group of the former in close proximity to the catalytic metal center of the latter.

Highly relevant to this work are the reports of Iwasava and Schramm describing the use of gold(I) complexes of phosphoramidite ligands derived from resorcin[4]arene deep cavitands 1 (Figure 2, left).18−23 More recently, Echavarren introduced chiral versions of structurally related phosphoramidite ligands and their gold(I) complexes.24 Encouraged by these results, we became interested in preparing structurally related phosphoramidite aryl-extended calix[4]pyrrole (AE-C[4]P) cavitands and studying their catalytic performance as Au(I) ligands (Figure 2, right). In contrast to the nonpolar cavity of resorcin[4]arenes, the cone conformation of AE-C[4]P cavitands possess a polar cavity that is ideal for the binding/inclusion of suitable compounds with electron-rich functional groups (e.g., ketone, amide, and N-oxide). The formed inclusion complexes are stabilized by establishing up to four convergent hydrogen bonds between the pyrrole NHs of the AE-C[4]P and the electron-rich functional group of the guest, as well as other additional CH-π or even π–π interactions with the meso-aryl substituents of the receptor (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Line drawing structures of the triflate salts of “in” mononuclear Au(I) phosphoramidites derived from a resorcin[4]arene cavitand (left) and an aryl-extended calix[4]pyrrole cavitand (right).

In this article, we report the synthesis, isolation, and characterization of two diastereomerically pure monophosphoramidite bridged C[4]P cavitands 2in and 2out. We also describe their conversion into the corresponding gold(I) complexes, 2in•Au(I) and 2out•Au(I), respectively (Scheme 1), and the results of the evaluation of their catalytic performance using the hydration of a series of propargyl esters as a benchmarking reaction. The corresponding reference reactions involve the use of phosphoramidite gold(I) complex 5•Au(I)•Cl (Scheme 2). Au(I) phosphoramidites are well-known catalysts having a well characterized performance in asymmetric reactions.25 The selected substrates were propargyl esters possessing a six-membered ring substituent featuring different hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and Lewis base (basicity) capabilities: cyclohexyl 3a, δ-lactone 3b, δ-lactam 3c, and pyridine N-oxide 3d (see Scheme 2 for structures). We aimed at using 3a, equipped with a nonpolar cyclohexyl group, as the reference and the electron-rich functionalized cyclic substituents of 3b–d as knobs to drive their inclusion in the polar cavity of the 2in•Au(I) C[4]P phosphoramidite cavitand.26 In this manner, bound polar substrates 3b–d should locate their propargyl groups in close proximity to the catalytic Au(I) metal center of the cavitand (Figure 1). We expected that for the 2in•Au(I) catalyst, the hydration reaction rates of the different polar substrates would correlate with the thermodynamic stabilities of the formed catalyst–substrate complexes. On the contrary, for 2out•Au(I) and 5•Au(I), the hydration reaction rates of the different substrates should not correlate with the HBA capabilities of their cyclic substituents. This work does not aim to contribute to a further understanding of the mechanistic aspects of the hydration reaction of alkynyl groups catalyzed by Au(I) complexes. The reaction was simply selected as a model system to evaluate the rate acceleration effects provoked by incorporating an AE-C[4]P unit in the scaffold of the ligands of Au(I) complexes when propargyl esters equipped with suitable binding groups were used as substrates.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Scheme for the Preparation of the Diastereomeric Au(I)•Cl Complexes of the Phosphoramidite C[4]P Cavitands.

Scheme 2. Hydration Reactions of the Propargyl Esters 3 Yielding the Corresponding Methyl Ketones 4.

The line-drawing structure of the phosphoramidite gold(I) complex 5•Au(I)•Cl used as the model catalyst is also shown.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

We undertook the synthesis of the phosphoramidite C[4]P 2in by reacting diethylphosphoramidous dichloride with the monomethylene bridged C[4]P cavitand 4(27) in THF solution at room temperature (rt) using triethylamine as the base. The reaction crude afforded a mixture close to 1:1 of the two diastereomeric monophosphoramidites: 2in and 2out (Scheme 1). This result is in contrast with those obtained in the syntheses of monophosphoramidites derived from resorcin[4]arene cavitands, for which the in-isomer is exclusively or selectively obtained.18,24 All our attempts to separate the 2in and 2out diastereoisomers using column chromatography failed. We obtained pure analytical samples of the two diastereomers by means of fractional crystallization of the enriched fractions. Unfortunately, we could not scale up the procedure. On the other hand, we were aware from Echavarren’s report that diastereomeric Au(I) chloride complexes of mono- and bis-phosphoramidite resorcin[4]arene cavitands were successfully separated and purified using column chromatography.24 For this reason, we reacted the diastereomeric mixture of phosphoramidite C[4]Ps, 2, with AuCl•S(CH3)2 obtaining a mixture of the corresponding Au(I) complexes, 2•Au(I) (Scheme S2). Column chromatography purification of the crude reaction mixture allowed the isolation of the two pure diastereomeric Au(I) complexes, 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl, in 20% yield, respectively.

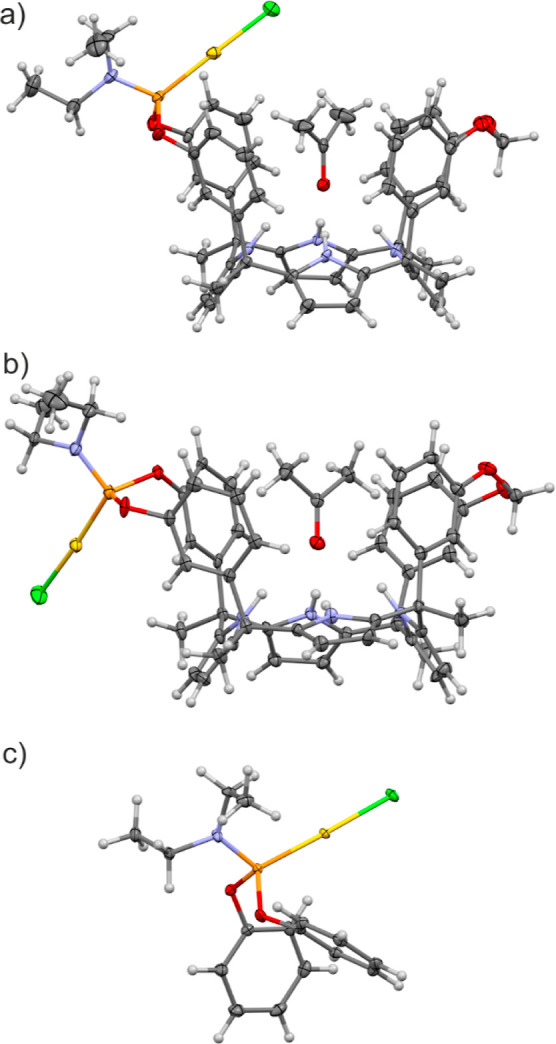

The molecular structures of 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl were determined by using NMR spectroscopy (Figures S5–S8) and single-crystal X-ray diffraction. In both cases and in the solid state, the C[4]P core adopted the cone conformation and included one molecule of acetone. The oxygen atom of the acetone molecule formed four convergent hydrogen bonds with the pyrrole NHs, and the methyl groups were involved in CH-π interactions with the meso-aryl groups. The crystal structure of the 2in•Au(I)•Cl complex evidenced the designed introverted arrangement of the Au(I) atom with respect to the polar aromatic cavity of the ligand. The included Figure 3a acetone molecule was sandwiched between the Au(I)•Cl atoms and the aromatic walls of the cavitand. On the other hand, the structure of the 2out•Au(I)•Cl complex showed the “out” orientation of the Au(I) atom with respect to the polar aromatic cavity also including one molecule of acetone (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of CH3COCH3 ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•Cl (a) and CH3COCH3 ⊂ 2out•Au(I)•Cl (b) inclusion complexes and the 5•Au(I)•Cl (c) complex. Thermal ellipsoids for C, N, O, P, Cl, and Au atoms were set at 50% probability; H atoms are shown as spheres of 0.15 Å radius.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the 2in•Au(I)•Cl complex in acetone-d6 solution showed a single set of sharp signals, suggesting its existence as a single conformer (Figure S5). Analogously, the 1H NMR spectrum of the 2out•Au(I)•Cl complex also displayed sharp and well-defined proton signals (Figure S7). The proton chemical shifts were almost identical for the two diastereoisomers. There was no indication of upfield shifts for the hydrogen atoms of the inwardly directed ethyl substituents of the bridging phosphoramidite in the 2out•Au(I)•Cl complex. Notably, the 31P NMR spectra of the two Au(I) diastereomeric complexes revealed that the singlet of the phosphorus atom in 2out•Au(I)•Cl (Figure S8) appeared slightly upfield shifted (Δδ ≈ 5.0 ppm) in comparison to that of the “in” counterpart (Figure S6). We hypothesized that in acetone-d6 solution, 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl adopt the cone conformation by including one solvent molecule in their polar cavities. This assumption was also supported by the X-ray structures of single crystals of the two complexes that grew in the NMR tubes from the above acetone-d6 solutions (Figure 3). The two C[4]P complexes, 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl, are configurational isomers and cannot be interconverted by a conformational exchange.

As a model catalyst for the reference reactions, we prepared the phosphoramidite gold(I) complex 5•Au(I)•Cl (Scheme 2). The synthesis of 5 was reported in the literature,28 and we obtained the corresponding Au(I) complex following the standard methodology.29 Ligand 5 is electronically similar to the phosphoramidite unit of the C[4]Ps but lacks a polar cavity. We characterized complex 5•Au(I)•Cl in solution by NMR spectroscopy (Figures S14–S15) and in the solid state using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 3c).

The propargyl esters 3a, 3b, 3c, and 3d, used as substrates in the Au(I)-catalyzed hydration reactions of their propargyl residue (Scheme 2), were uneventfully synthesized by coupling the corresponding carboxylic acids with propargyl alcohol using 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide as the activating agent and dimethylamino pyridine as the base (see the Supporting Information).30

2.2. Catalytic Activity Studies

Inspired by the pioneering work of Schramm, Iwasawa, and co-workers, we attempted the hydration reaction of n-hexyne (0.1 M) in toluene-d8 at 85 °C using 5 mol % of 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 1 equiv of added water (Scheme S12).18 After 24 h, in agreement with the report using the Au(I) resorcin[4]arene phosphoramidite 1in•Au(I)•Cl (R = Me) (Figure 2), the 1H NMR spectrum of the mixture showed the exclusive presence of the starting material.

It is well-known that the nature of the counteranion plays a pivotal role in multiple steps of the alkyne hydration catalytic pathway (i.e., dissociation pre-equilibrium, nucleophilic attack, and protodeauration).31 Owing to its favorable characteristics, triflate (−OTf) is one of the most common counterions used in cationic Au(I)-catalyzed transformations. In order to generate catalytically active cationic Au(I) species, usually, the corresponding chloride complexes are reacted with a silver salt, i.e., silver triflate.32,33 This induces anion metathesis by precipitation of AgCl and the formation of the related –OTf Au(I) complex. Soft and noncoordinating anions, such as –OTf, make the Au(I) catalytic center more “alkynephilic”.31 This procedure worked well to induce catalytic activity for resorcin[4]arene phosphoramidite 1in•Au(I)•Cl (R = Me). Consequently, we added 1 equiv of AgOTf to a toluene-d8 solution containing calix[4]pyrrole phosphoramidite 2in•Au(I)•Cl and observed the immediate appearance of a precipitate. After several minutes, we added n-hexyne (0.1 M) and analyzed the resulting mixture using 1H NMR spectroscopy at regular time intervals. After 1 h of the reaction, the proton signals of n-hexyne (starting material) and 2-hexanone (reaction product) showed similar integral values. However, after 24 h, the reaction had not progressed to completion (Figure S35). During this time, we observed the appearance of black metal residues, suggesting the decomposition of the catalyst under the reaction conditions. These preliminary tests using a well-known reference substrate evidenced the catalytic properties of the combination of 2in•Au(I)•Cl with AgOTf. They also suggested that the hydration reaction conditions were suboptimal for the use of 2in•Au(I)•OTf.

Being aware that alkyne hydration34 and other reactions24 catalyzed by Au(I) cationic species perform well in dichloromethane solution, we decided to test the use of this solvent in the catalyzed hydration reactions of the propargyl esters 3.35 It is worth mentioning that the functional groups installed in the six-membered ring substituent of the ester derivatives 3 featured different HBA, Au(I) coordinating, and Lewis base capabilities32 (cyclohexyl 3a, δ-lactone 3b, δ-lactam 3c, and pyridine N-oxide 3d). The reaction conditions were adjusted to achieve reproducible kinetic data and, in the best cases, accurate reaction rates (see the Supporting Information for details). First and to minimize complications due to handling heterogeneous solutions, we prepared homogeneous stock solutions of the Au(I) triflate catalysts by filtrating the precipitated AgCl. We used the obtained homogeneous solutions to setup parallel hydration reactions of the four esters.36 Second, we used a water saturated dichloromethane solution as the reaction solvent. The concentration of water in saturated dichloromethane is approximately 50 mM. For this reason and to slow down the fastest reaction kinetics, facilitating their monitoring using 1H NMR spectroscopy, we reduced the concentration of the reacting ester 3 to 10 mM. Finally, we ran all hydration reactions at rt. We mathematically analyzed the measured kinetic data (changes in concentrations) using the theoretical model for a bimolecular irreversible reaction. The fit of the experimental kinetic data was good (Figures S23–48) for fast reactions (100% conversion t > 24 h), and the returned rate constant values are summarized in Table 1. For slow reactions (t > 24 h, conversion <100%), the experimental data did not show a good fit to the theoretical model. Most likely, in these cases, a theoretical model including additional processes is necessary (e.g., catalyst decomposition and different activation/deactivation mechanisms).37 For the cases in which the fit of the kinetic data is not good with respect to that of a bimolecular irreversible reaction, we included in Table 1 an estimate of the reaction rate. In all cases, for additional comparison of the reaction kinetic properties, we tabulated the % of reaction conversion at 30 min.

Table 1. Calculated and Estimated Rate Constants, k, (M–1·min–1, 298 K) for the Catalyzed Hydration Reactions of the Propargyl Esters 3ab.

| catalyst | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2in•Au(I)•OTf | 1.7 ± 0.3 (>80 ± 2) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (48 ± 3) | <1 × 10–3 (<1) | n.dc |

| 2 | 2out•Au(I)•OTf | 1.0 ± 0.1 (80 ± 2) | 0.4 ± 0.1 (42 ± 2) | <10 × 10–3 (<1) | n.dc |

| 3 | 5•Au(I)•OTf | 0.89 ± 0.04 (74 ± 2) | 0.71 ± 0.03 (62 ± 2) | (28.0 ± 0.2) × 10–3 (12 ± 2) | n.dc |

The values in parentheses represent the % of reaction conversion after 30 min.

Reaction conditions: [3] = 10 mM, [catalyst] = 0.5 mM, rt, water saturated CD2Cl2. All reactions were performed at least in duplicate, and reported errors are standard deviations.

n.d.: not determined; the hydration product was not detected by 1H NMR after 30 min (Figures S37–S48 for the fit of the kinetic data).

We tried to derive some conclusions and general trends from the tabulated data. First, we compared the results of the C[4]P phosphoramidite ligands with those of the model phosphoramidite 5 for the same substrate (columns in Table 1).29 We observed small differences between the three phosphoramidite gold(I) catalysts in the hydration reactions of 3a (cyclohexyl) and 3b (ketone) (same order of magnitude). These results can be attributed to the similar nature of the three ligands (i.e., phosphoramidite ligands) and the known modulation of Au(I) Lewis acidity played by the ligand. Likewise, the noncovalent interactions that can be established between the ligands of the three catalysts and nonpolar substrates 3a and 3b are considered to be similar.31 Nevertheless, the conclusions described above did not hold for the results obtained in the hydration reaction of 3c (lactam). In this case, the best catalyst was the 5•Au(I)•OTf complex. Even more puzzling to us was the fact that the hydration reactions of 3d (pyridine N-oxide) did not proceed to a measurable extent after 30 min with any of the tested catalysts.

Second, focusing on the results with the 2in•Au(I)•OTf catalyst (Table 1, entry 1), the determined rate constant values (k) showed a very different picture from what we expected. The hydration of the substrates capable of forming the most thermodynamically stable inclusion complexes, 3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•OTf and 3d ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•OTf, featured smaller rate constants or even did not progress after 30 min, respectively. We identified the existence of a negative correlation between the increase in the HBA and Lewis base properties of the oxygen atom of the functional group in the six-membered cyclic substituent of the propargyl esters 3b (β(C=O) = 5.8), 3c (β(–HNC=O) = 8.3), and 3d (β(–N+–O–) = 9.4)38 and the catalytic efficiency of the 2in•Au(I)•OTf complex. This effect is somewhat related to the known correlation existing between the HBA properties of oxyanions (basicity) and their gold affinity index.39 Unfortunately, despite the slow reaction rates observed for the three catalysts with N-oxide 3d, we were not able to isolate any of the formed complexes to perform a detailed structure determination. In this vein, we describe in the next section the 1H NMR characterization of the complexes of the catalysts with derivatives 6a and 6c having a terminal ethylene group instead of the reacting ethynyl.

Returning to the results obtained with the 2in•Au(I)•OTf catalyst, the keto group in 3b induced a 3-fold diminution in the rate constant compared to the unfunctionalized cyclohexyl 3a [k(3a)/k(3b) ≈ 3]. Remarkably, the presence of the amide group in 3c caused a drop in the rate constant of more than 3 orders of magnitude [k(3a)/k(3c) > 1000]. Finally, the pyridine-N-oxide in compound 3d practically inhibited the reaction.

The two other complexes 2out•Au(I)•OTf (entry 2) and 5•Au(I)•OTf (entry 3) showed a similar trend in their catalytic activities for the hydrolysis reactions of the three polar substrates 3b–3d. In particular, for 2out•Au(I)•OTf, the hydration reaction constant of the ketone derivative 3b decreased 3-fold compared to that of the cyclohexyl counterpart 3a [k(3a)/k(3b) ≈ 3], while for the lactam 3b, the rate constant dropped about 2 orders of magnitude [k(3a)/k(3c) ≈ 100]. The activity of the model catalyst 5•Au(I)•OTf was the least affected by the changes in the substrate’s polarity. For 5•Au(I)•OTf, the values of the rate constants ratios were k(3a)/k(3b) = 1.25 and k(3a)/k(3c) ≈ 30. Notably, N-oxide 3d also practically inhibited the hydrolysis reaction with these two catalysts.

2.3. Binding Studies of Model Compounds and Explanation of the Catalysis Results

To rationalize the obtained results, we considered that the polar substrates 3b–d and their corresponding products 4b–d might be interacting (coordinating) with the Au(I) metal center of the catalysts. To dissect this effect, we focused on the study of the catalytic behavior of 5•Au(I)•OTf lacking the C[4]P binding site in the metal’s second coordination sphere. As mentioned above, the decrease in catalytic efficiency of all catalysts (k(3a) > k(3b) > k(3c) > k(3d)) correlated well with the increase in the HBA properties (Lewis basicity) of the functional group in the substrate’s six-membered ring (3d N-oxide > 3c amide > 3b ketone > 3a methylene). We are aware that Au(I) is a soft metal center and binds weakly to hard Lewis bases, i.e., N and O. However, owing to the large substrate’s concentration (10 mM) used in the kinetic experiments, the formation of putative complexes by coordination of the Au(I) metal center with the electron-rich oxygen atom of the substrates/products [3b/4b (β(C=O) = 5.8), 3c/4c (β(–HNC=O) = 8.3), and 3d (β(–N+–O–) = 9.4)] might take place to a considerable extent (Figure 4).40 The formation of these complexes was expected to reduce the catalytic efficiency of the Au(I) complex by blocking the cationic metal center.

Figure 4.

Possible equilibria involved in the formation of putative coordination complexes of polar substrates with Au(I) catalysts.

To verify this hypothesis, we performed 1H NMR titrations of 5•Au(I)•OTf with model compounds 6a (cyclohexyl) and 6c (lactam) (Figure 4) bearing a terminal ethylene (β = 1.1) instead of the ethynyl group (β = 2.7) of 3a and 3c. In doing so, we avoided any background hydration reaction.

The incremental addition of 6a to a 10 mM dichloromethane-d2 solution of 5•Au(I)•OTf did not produce noticeable chemical shift changes to the proton signals of the triflate salt (Figure S70). We estimated a reduced binding constant, i.e., <10 M–1 for the putative 6a•5•Au(I)•OTf complex. Conversely, an analogous titration using 6c induced clear chemical shift changes in the proton signals of 5•Au(I)•OTf (Figure S71). The fit of the titration data to a 1:1 theoretical binding model was good and returned a binding constant of Ka(6c•5•Au(I)•OTf) = 2 × 103 M–1 (Figure S72).41 Considering the concentration of substrate 3c and catalyst 5•Au(I)•OTf used in the hydration reaction, the 3c•5•Au(I)•OTf complex would be present to an extent of 90% in solution (see the speciation profile in Figure S73). In short, close to 90% of the electrophilic Au(I) metal center of 5•Au(I)•OTf would not be available to coordinate with the terminal alkynyl group of 3c. The competitive coordination of the lactam groups of 3c/4c to the Au(I) catalytic metal center might explain the significant loss of catalytic efficiency observed for 5•Au(I)•OTf in the hydration of 3c compared to that of 3a. For the same token, the reduced drop in catalytic efficiency measured for 5•Au(I)•OTf in the hydration of 3b (ketone) compared to that of 3a might derive from the competitive but weaker coordination of the ketone oxygen atom of 3b. The ketone group displays reduced HBA and Lewis base properties [3b, β(C=O) = 5.8], binding much more weakly to the Au(I) metal center than the amide group of 3c [β(–HNC=O) = 8.3].

The N-oxide derivative 3d featured the largest HBA properties [β(–N+–O–) = 9.4] and showed the strongest coordination to the electrophilic gold atom (Ka > 104 M–1, Figures S74–S75). That is, under the conditions used for the kinetic experiments, more than 99% of the Au(I) is coordinated to the pyridine N-oxide of 3d and is not available for catalyzing the reaction. The competitive coordination hypothesis can also be applied to explain the catalysis results of the C[4]P phosphoramidite complexes, 2in•Au(I)•OTf and 2out•Au(I)•OTf, with the four substrates.

Nevertheless, the explanation of the trend in the efficiency of the three catalysts measured for the hydration reaction of lactam 3c (Table 1, column 5) demanded the consideration of noncovalent interactions between the C[4]P binding site present in phosphoramidite ligands 2in and 2out and the substrate.32 To this end, we also performed separate 1H NMR spectroscopic titrations of 2in•Au(I)•OTf and 2out•Au(I)•OTf complexes with reference compounds 6a and 6c (Figures S76–S78).

Not surprisingly, the incremental addition of 6a to separate dichloromethane-d2 solutions of the C[4]P phosphoramidite Au(I) complexes did not induce chemical shift changes to their proton signals (Figure S76). In striking contrast, the incremental addition of 6c evidenced the formation of 1:1 inclusion complexes, for which we estimated binding constants larger than 104 M–1 (Figures S77 and S78).42 Remarkably, the pyrrole NH protons of the C[4]P experienced a downfield shift upon binding the substrate, indicating the formation of hydrogen bonds with the oxygen atom of the lactam residue. These results indicated that for lactam 6c, the polar C[4]P aromatic cavity of the C[4]P phosphoramidite ligands represented a competitive and superior binding site than the Au(I) metal center. The chemical shift changes experienced by the β-pyrrole protons suggested that the C[4]P unit was involved in a conformational change. Most likely, it moved from mainly an alternate conformation in the free state to a cone conformation upon substrate binding.

Taken together, the findings described above suggested that under the conditions for catalytic hydration of lactam 3c with C[4]P phosphoramidite Au(I) complexes, the C[4]P binding site in the second coordination sphere of the metal included one molecule of the substrate/product.

On one hand, the binding of 3c in the C[4]P cavity of 2out•Au(I)•OTf is expected to play a minor role in modulating its catalytic activity. However, under the described reaction conditions, 95% of the substrate’s total concentration remains available to compete for coordination with the “out” Au(I) metal center. As described above, this competitive coordination process blocks the catalytic performance of the Au(I) center (i.e., –HNC=O···Au(I)+), explaining the decrease measured in the rate constant of this catalyst for the hydration of 3c (lactam) in comparison to that of 3b (ketone), k(3b)/k(3c) > 40. A similar rate constant ratio, k(3b)/k(3c) = 25, was displayed by the 5•Au(I)•OTf complex, for which only the blocking mechanism of the metal center by coordination to 3c is operative. We explain the slight increase in the k(3b)/k(3c) ratio observed for 2out•Au(I)•OTf by claiming unfavorable electronic and/or conformational changes experienced by the ligand upon binding the compounds 3c/4c in its C[4]P cavity.

On the other hand, the inclusion of 3c in the C[4]P cavity of 2in•Au(I)•OTf hinders the coordination of another substrate molecule to the Au(I) atom in the resulting 3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•OTf complex (Figure 5c). Moreover, as supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Figure S80), the included 3c may also coordinate to the Au(I) metal center through the oxygen atom of its carbonyl ester group. This interaction surely impacts the electrophilic nature of the cationic metal (Figure 5a). To make matters worse, the intramolecular interaction with the bound substrate’s alkynyl group and the Au(I) metal center (Figure 5b) and/or the transition state of the intramolecular catalyzed hydration reaction seemed to be energetically more demanding than that of their intermolecular counterparts. The above justifications are used to explain the marked difference in the ratios of hydration rate constants for 3b and 3c displayed by 2in•Au(I)•OTf, k(3b)/k(3c) > 500 in comparison to that of its diastereomeric counterpart 2out•Au(I)•OTf, k(3b)/k(3c) = 40.

Figure 5.

Possible binding geometries of 1:1 inclusion complexes of substrate 3c with the 2in•Au(I)+ catalyst (a–d). The O-monotopic binding geometry (d) can also be obtained with the 2out•Au(I)+ catalyst. Assuming Ka = 1 × 104 M–1 (see the text) for the 3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•OTf complex, >99% of the catalyst is involved in a 1:1 complex in the initial stages of the reaction. DFT calculations at the BP86 D3-def2-SVP level of theory using Turbomole v7.0 suggested that conformation (a) was the most thermodynamically stable (Supporting Information for details).

In the case of substrate 3d, pyridine N-oxide binds the C4P cavity of 2in•Au(I)•OTf and 2out•Au(I)•OTf with a Ka > 104 M–1. In this case, the oxygen atom of the pyridine N-oxide moiety is an even better HBA and Lewis base than the lactam one, and 95% of the free substrate remains available for favorable interaction with Au(I) center. We propose that the strong coordination to the Au(I) is responsible for the large reduction of the hydration rate constant of 3d, resulting in the concentration of the hydration product being not detectable using 1H NMR spectroscopy after 30 min of the reaction.43

In order to validate the above hypothesis, we studied the kinetic performance of the three catalysts using the cyclohexyl propargyl ester 3a as the substrate in the presence of equimolar amounts of polar molecules [cyclohexanone (7), 2-piperidinone (8), or pyridine N-oxide (9)] that are structurally closely related to the polar residues of substrates 3c–3d. The obtained kinetic results followed a trend similar to that observed for substrates 3a–3d incorporating the polar residue covalently connected to the hydration reacting unit (vide supra) (see the Supporting Information for details, Table S1 and Figures S49–S55). For the three catalysts, the presence of a strong Lewis base and an HBA molecule (2-piperidinone or pyridine N-oxide) in the reaction medium significantly decreased the rate constant of the hydration reaction of cyclohexyl propargyl ester 3a. In line with the results described for substrates 3a–3d, the most affected catalyst was 2in•Au(I)•OTf, and the competing molecule provoking the larger influence on the reaction rate was pyridine N-oxide 9.

2.4. Hydration Reactions of 3a in the Presence of Substoichiometric Amounts of Pyridine-N-oxide Derivatives and Additional Experimental Support to the Above Provided Explanations

In order to evaluate the effect on the rate acceleration provoked by the incorporation of an AE-C[4]P unit in the ligands’ scaffolds of Au(I) complexes when using propargyl esters with polar binding groups as substrates and to provide further experimental support to the hypotheses delineated above, we undertook additional catalytic experiments. First, we repeated the hydration reactions of the cyclohexyl propargyl ester 3a using the three Au(I) catalysts but adding 5 mol % of 4-phenylpyridine-N-oxide 10 as an effector (Figures S56–S63).44 This represents adding 1 equiv of 10 with respect to the Au(I) catalyst.

The use of additives containing HBA groups in homogeneous Au(I) catalysis was described to have different effects depending on the rate-determining step (RDS) of the reaction.45 For instance, in gold-catalyzed reactions where the protodeauration was the RDS, the addition of pyridine N-oxide considerably increased the rate of the reaction [e.g., Au(I)-catalyzed cyclization of propargyl amide].46 Conversely, when the nucleophilic attack was the RDS, the addition of compounds with HBA groups also displaying high affinity for Au(I) coordination, such as pyridine N-oxide, inhibited or slowed the reaction owing to their competition with the alkyne in coordinating the Au(I) metal center. This inhibition mechanism is also suggested in previous sections of this work.

The oxygen atom of the pyridine N-oxide is a better HBA and Lewis base [β(–N+–O–) = 9.4]38 than that of cyclohexanone [β(C=O) = 5.8] or δ-lactam [β(–HNC=O) = 8.3]. Likewise, pyridine N-oxides feature a larger binding affinity, in dichloromethane solution, for aryl extended C[4]Ps (Ka > 106 M–1) than cyclohexanone (Ka = 18 M–1) and δ-lactam (Ka = 6 × 104 M–1).26 We observed that the addition of 4-phenylpyridine-N-oxide 10 produced a detrimental effect in the efficiency of the three catalysts in the hydration reaction of 3a (Table 2, third column). However, the magnitudes of the effect were significantly different for each of them.

Table 2. Calculated Rate Constants k (M–1 min–1, 298 K) for the Catalyzed Hydration Reactions of Propargyl Ester 3a with and without N-Oxideab.

| N-oxide |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| catalyst | no N-oxide | 10 | 9 |

| 2in•Au(I)•OTf | 1.7 ± 0.3 (>80 ± 2) | 0.035 ± 0.007 (10 ± 2) | 0.30 ± 0.06 (36 ± 1) |

| 2out•Au(I)•OTf | 1.0 ± 0.1 (80 ± 2) | 0.34 ± 0.08 (38 ± 2) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (40 ± 4) |

| 5•Au(I)•OTf | 0.89 ± 0.04 (74 ± 2) | <1 × 10–2c (<5) | <1 × 10–2c (<5) |

The values in parentheses represent the % of reaction conversion after 30 min.

Reaction conditions: [3a] = 10 mM, [catalyst] = 0.5 mM, [N-oxide] = 0.5 mM, rt, and water saturated CD2Cl2.

The selected theoretical kinetic model considering a bimolecular irreversible reaction did not provide a good fit to the experimental results and we could only estimate a value of the reaction rate.

For example, the addition of 4-phenylpyridine N-oxide 10 caused a large reduction in the reaction rate of the hydration reaction of 3a catalyzed by the reference catalyst, 5•Au(I)•OTf, lacking the C[4]P unit. The percentage of the hydration product, 4a, after 30 min was less than 5%. This result indicated an efficient coordination of the N-oxide with the Au(I) metal center (Table 2).47 In contrast, the presence of 5% of 10 in the hydration reaction of 3a catalyzed by 2in•Au(I)•OTf produced a 50-fold decrease in the rate constant (10% of 4a, after 30 min) (Table 2 and Figures S37–38). This finding showed that the N-oxide was mainly included in the C[4]P cavity of the phosphoramidite ligand 2in instead of being directly coordinated to the Au(I) metal center. In short, the formed 10 ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•OTf complex was still operative for catalyzing the hydration of 3a. We hypothesized that the partial deactivation of the 2in•Au(I)•OTf catalyst by the inclusion of 10 in the C[4]P cavity of the metal’s second coordination sphere was mainly due to steric effects hindering the access/coordination of the terminal alkynyl group of 3a to the Au(I) center. To substantiate this hypothesis, we substituted 10 by the shorter pyridine-N-oxide 9, which should have a reduced steric impact on the access/coordination of 3a to the Au(I) metal center (Figure 6). In the presence of 5% of 9, the rate constant of the hydrolysis of 3a catalyzed by 2in•Au(I)•OTf decreased only 5-fold (36% of 4a, after 30 min) (Table 2 and Figures S65–66).

Figure 6.

Energy minimized structures (MM3) of the complexes: (a) 9 ⊂ 2in•Au(I)+ and (b) 10 ⊂ 2in•Au(I)+.

Notably, the addition of 5% of the 4-phenylpyridine N-oxide 10 or pyridine N-oxide 9 to the catalyzed hydration reaction of 3a using 2out•Au(I)•OTf produced a decrease in the rate constant of less than 3-fold (Table 2 and Figures S39–40) in both cases (40% of 4a, after 30 min). This outcome supported the preferred inclusion of 9 and 10 in the C[4]P cavity of the 2out ligand instead of coordinating to the Au(I) metal. Taken together, the results obtained in the hydration reactions of 3a in the presence of substoichiometric amounts of pyridine N-oxide derivatives as catalysts’ effectors supported that the catalysts’ deactivation was mainly caused by the N-oxide direct coordination to the Au(I) metal. The inclusion of the pyridine N-oxide in the C[4]P binding site, delimiting the second coordination sphere of the metal, was also detrimental for the catalysts’ efficiency. It is worth noting that the latter process was especially relevant for the 2in•Au(I)•OTf due to the inward orientation of the Au(I) center toward the C[4]P cavity.

To verify the harmless effect produced by the N-oxides with respect to the oxidation state of the Au(I) metal center, we performed the hydration of 3a using a solution of 2in•Au(I)•OTf containing 1 equiv of 10 as the catalyst effector (5 mol %). In agreement with a rate constant of 0.035 M–1 min–1, the conversion to the methyl ketone 4a was only ca. 10% after 30 min. Having observed the reaction’s rate suppression, we added the C[4]P cavitand 11 (Figure 7) to the reacting mixture (10 equiv. with respect to the N-oxide 10). We observed the partial restoration of the catalytic activity of 2in•Au(I)•OTf corresponding to a 10-fold increase in the hydration reaction rate constant (Figure S67). This value did not exactly match the one measured for pristine 2in•Au(I)•OTf. Nevertheless, the increase in rate acceleration was significant and supported the partial displacement of 10 from the 10 ⊂ 2in•Au(I) complex owing to a competitive inclusion in the C[4]P cavity of 11. The concomitant recovery of the “free” 2in•Au(I)•OTf complex explained the regeneration of the catalytic activity (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Equilibrium between the inclusion complexes of 4-phenyl pyridine-N-oxide 10 with the C[4]P cavitands 2in•Au(I)•OTf and 11. The addition of 10 equiv of 11 is expected to drive the equilibrium toward the formation of the 10 ⊂ 11 complex and free 2in•Au(I)•OTf catalyst.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we described the synthesis and separation of two Au(I) complexes, 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl, having diastereomeric phosphoramidite calix[4]pyrrole cavitands as ligands. The two complexes are configurational isomers and cannot interconvert through a conformational process. The crystal structure of the 2in•Au(I)•Cl and 2out•Au(I)•Cl complexes confirmed the inwardly and outwardly directed arrangement of the Au(I) metal center with respect to the calix[4]pyrrole cavity, respectively.

We used the catalysts in hydration reactions of a series of propargyl esters 3a–d equipped with a six-membered-ring substituent featuring different HBA properties. We also prepared the phosphoramidite 5•Au(I)•Cl as a benchmarking reference catalyst. We extracted the following conclusions from the analyses of the results obtained in our kinetic studies:

-

1

C[4]P cavitands 2in and 2out performed similar to the model phosphoramidite ligand 5 in the Au(I)-catalyzed hydration of propargyl esters lacking an HBA unit (3a, cyclohexyl) or equipped with a weak HBA counterpart (3b, ketone).

-

2

The presence of a strong HBA unit in the propargyl substrate (3c, δ-lactam and 3d, pyridine N-oxide) produced a significant decrease of the hydration reaction rate constant for the three catalysts. On one hand, the hydration of the propargyl ester 3d featuring a pyridine N-oxide moiety did not progress to a detectable extent after 30 min using any of the three catalysts. On the other hand, the magnitudes of the k(3a)/k(3c) ratios span from one to three orders depending on the catalyst’s ligand framework. For the Au(I) complexes of ligands 2out and 5, the decrease in the rate constant for the hydration of lactam 3c was mainly attributed to the competitive coordination of the oxygen atom of the amide group to the Au(I) metal center. In contrast, for 2in, the deactivation of the catalyst was exacerbated by binding and including 3c in its C[4]P cavity. This produced steric clashes with the inwardly directed catalytic Au(I) metal center, hindered the approach/coordination of the alkynyl residue of another substrate molecule, and produced ditopic coordination complexes of Au(I) to the ester group functions. We also hypothesized that the transition state of the intramolecularly catalyzed hydration reaction that may occur in the 3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)•OTf complex is energetically more demanding than the intermolecular counterpart.

-

3

The use of pyridine N-oxides as catalyst effectors (equimolar amount with respect to the 5% of catalyst) induced a drop of the catalytic activity of the complex 5•Au(I)•OTf based on the model phosphoramidite ligand. This was attributed to an efficient coordination of the N-oxides to the Au(I) metal center. Conversely, for the Au(I) catalysts based on the C[4]P phosphoramidites ligands, 2in and 2out, the N-oxide effectors were preferentially included in their C[4]P cavities rather than coordinated to the catalytic Au(I) metal center. Consequently, for the 2out•Au(I)•OTf catalyst, the presence of the effector produced small changes on the rate constant of the hydration of 3a. However, for the 2in•Au(I)•OTf catalyst, the rate constant for the hydration of 3a diminished by 2 orders of magnitude. This different behavior was caused by the dissimilar steric effects produced by the included N-oxide. In the 10 ⊂ 2out•Au(I) complex, the catalytic Au(I) center is distal from the included N-oxide. However, for the 10 ⊂ 2in•Au(I) complex, the Au(I) is directed toward the included effector.

The reported results highlight some limitations of incorporating an AE-C[4]P unit in phosphoramidite ligands for catalytic metal centers, aiming at the selective acceleration of the reactions with substrates containing polar functional groups. On the other hand, the described findings using the Au(I) catalyzed hydration reaction of propargyl ester as the benchmark reaction augur well for the potential application of 2in•Au(I)•OTf, as well as other metal catalysts based on 2in, in enantioselective processes using chiral N-oxides as effectors. We are currently investigating this issue and expect to report our findings in due time.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/Agencia Estatal de Investigación (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) (PID2020-114020GB-I00 and CEX2019-000925-S), the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya, and AGAUR (2017SGR1123 and 2021SGR00851). E.B. thanks the European Union (Horizon 2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie COFUND grant agreement no 801474).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- C[4]P

calix[4]pyrrole

- HBA

hydrogen bond acceptor

- NHC

N-heterocyclic carbene

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c03089.

General methods and instrumentation, synthesis and characterization data, 1H NMR kinetic experiments, NMR titrations, X-ray structures Deposition numbers CCDC 2254479, 2254480, 2286244, and 2290754 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper (PDF)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.; experimental methodology and initial data analyses, A.F.S.; formal analyses, P.B. and G.A.; writing—original draft, A.F.S.; writing—reviewing and editing, P.B., E.B., A.F.S., and G.A.; and supervision, P.B. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Raynal M.; Ballester P.; Vidal-Ferran A.; van Leeuwen P. W. N. M. Supramolecular catalysis. Part 1: non-covalent interactions as a tool for building and modifying homogeneous catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (5), 1660–1733. 10.1039/C3CS60027K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynal M.; Ballester P.; Vidal-Ferran A.; van Leeuwen P. W. N. M. Supramolecular catalysis. Part 2: artificial enzyme mimics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (5), 1734–1787. 10.1039/C3CS60037H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.; Zhu J.; Luo Q.; Liu J. Understanding enzyme catalysis by means of supramolecular artificial enzymes. Sci. China Chem. 2013, 56 (8), 1067–1074. 10.1007/s11426-013-4871-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olivo G.; Capocasa G.; Del Giudice D.; Lanzalunga O.; Di Stefano S. New horizons for catalysis disclosed by supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50 (13), 7681–7724. 10.1039/D1CS00175B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houk K. N.; Leach A. G.; Kim S. P.; Zhang X. Binding Affinities of Host–Guest, Protein–Ligand, and Protein–Transition-State Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42 (40), 4872–4897. 10.1002/anie.200200565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballester P.; Vidal-Ferran A.. Introduction to Supramolecular Catalysis. In Supramolecular Catalysis; van Leeuwen P. W. N. M., Ed.; Wiley, 2008; pp 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Meeuwissen J.; Reek J. N. H. Supramolecular catalysis beyond enzyme mimics. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2 (8), 615–621. 10.1038/nchem.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans A. C. H.; Caumes X.; Reek J. N. H. Gold Catalysis in (Supra)Molecular Cages to Control Reactivity and Selectivity. ChemCatChem 2019, 11 (1), 287–297. 10.1002/cctc.201801399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratov K.; Gagosz F. Confinement-Induced Selectivities in Gold(I) Catalysis-The Benefit of Using Bulky Tri-(ortho-biaryl)phosphine Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61 (28), e202203452 10.1002/anie.202203452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavarzan A.; Reek J. N. H.; Trentin F.; Scarso A.; Strukul G. Substrate selectivity in the alkyne hydration mediated by NHC-Au(I) controlled by encapsulation of the catalyst within a hydrogen bonded hexameric host. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3 (11), 2898–2901. 10.1039/c3cy00300k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hkiri S.; Steinmetz M.; Schurhammer R.; Semeril D. Encapsulated Neutral Ruthenium Catalyst for Substrate-Selective Oxidation of Alcohols. Chem.—Eur. J. 2022, 28 (58), e202201887 10.1002/chem.202201887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavarzan A.; Scarso A.; Sgarbossa P.; Strukul G.; Reek J. N. H. Supramolecular Control on Chemo- and Regioselectivity via Encapsulation of (NHC)-Au Catalyst within a Hexameric Self-Assembled Host. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (9), 2848–2851. 10.1021/ja111106x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta C.; La Manna P.; De Rosa M.; Soriente A.; Talotta C.; Neri P. Supramolecular Catalysis with Self-Assembled Capsules and Cages: What Happens in Confined Spaces. ChemCatChem 2021, 13 (7), 1638–1658. 10.1002/cctc.202001570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. J.; Brown C. J.; Bergman R. G.; Raymond K. N.; Toste F. D. Hydroalkoxylation Catalyzed by a Gold(I) Complex Encapsulated in a Supramolecular Host. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (19), 7358–7360. 10.1021/ja202055v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai T.; Goto Y.; You Z. S.; Sawamura M. A Hollow-shaped Caged Triarylphosphine: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications to Gold(I)-catalyzed 1,8-Enyne Cycloisomerization. Chem. Lett. 2021, 50 (6), 1236–1239. 10.1246/cl.210176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rebilly J. N.; Colasson B.; Bistri O.; Over D.; Reinaud O. Biomimetic cavity-based metal complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44 (2), 467–489. 10.1039/C4CS00211C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouvé J.; Zardi P.; Al-Shehimy S.; Roisnel T.; Gramage-Doria R. Enzyme-like Supramolecular Iridium Catalysis Enabling C–H Bond Borylation of Pyridines with meta-Selectivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (33), 18006–18013. 10.1002/anie.202101997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm M. P.; Kanaura M.; Ito K.; Ide M.; Iwasawa T. Introverted Phosphorus-Au Cavitands for Catalytic Use. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2016, 813–820. 10.1002/ejoc.201501426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endo N.; Inoue M.; Iwasawa T. Rational Design of a Metallocatalytic Cavitand for Regioselective Hydration of Specific Alkynes. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2018, (9), 1136–1140. 10.1002/ejoc.201701613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M.; Ugawa K.; Maruyama T.; Iwasawa T. Selective Catalytic Hydration of Alkynes in the Presence of Au-Cavitands: A Study in Structure-Activity Relationships. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2018, 2018 (38), 5304–5311. 10.1002/ejoc.201800948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endo N.; Kanaura M.; Schramm M. P.; Iwasawa T. Evaluation of tuned phosphorus cavitands on catalytic cross-dimerization of terminal alkynes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57 (42), 4754–4757. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.09.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rusali L. E.; Schramm M. P. Au-Cavitands: Size governed arene-alkyne cycloisomerization. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61 (40), 152333. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.152333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T. D.; Schramm M. P. Au-Cavitand Catalyzed Alkyne-Acid Cyclizations. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2019, (33), 5678–5684. 10.1002/ejoc.201900829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Torres I.; Ogalla G.; Yang J. M.; Rinaldi A.; Echavarren A. M. Enantioselective Alkoxycyclization of 1,6-Enynes with Gold(I)-Cavitands: Total Synthesis of Mafaicheenamine C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (17), 9339–9344. 10.1002/anie.202017035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichert J. F.; Feringa B. L. Phosphoramidites: Privileged Ligands in Asymmetric Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49 (14), 2486–2528. 10.1002/anie.200904948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñuelas-Haro G.; Ballester P. Efficient hydrogen bonding recognition in water using aryl-extended calix[4]pyrrole receptors. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (8), 2413–2423. 10.1039/C8SC05034A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A. F.; Hernández-Alonso D.; Romero M. A.; González-Delgado J. A.; Pischel U.; Ballester P. Optical Supramolecular Sensing of Creatinine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (9), 4276–4284. 10.1021/jacs.9b12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perich J.; Alewood P.; Johns R. Synthesis of Casein-Related Peptides and Phosphopeptides. VII. The Efficient Synthesis of Ser(P)-Containing Peptides by the Use of Boc-Ser(PO3R2)OH Derivatives. Aust. J. Chem. 1991, 44 (2), 233–252. 10.1071/CH9910233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Commercially available N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) gold(I) complex was also tested as model catalyst. Results showed a similar trend to those obtained with model catalyst 5•Au(I)•OTf and are included in the Supporting Information document.

- Neises B.; Steglich W. Simple Method for the Esterification of Carboxylic Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1978, 17 (7), 522–524. 10.1002/anie.197805221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccaccia D.; Del Zotto A.; Baratta W. The pivotal role of the counterion in gold catalyzed hydration and alkoxylation of alkynes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 396, 103–116. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia M.; Bandini M. Counterion Effects in Homogeneous Gold Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2015, 5 (3), 1638–1652. 10.1021/cs501902v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Smith J. J.; Staben S. T.; Toste F. D. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Conia-Ene Reaction of β-Ketoesters with Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (14), 4526–4527. 10.1021/ja049487s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva A.; Corma A. Isolable Gold(I) Complexes Having One Low-Coordinating Ligand as Catalysts for the Selective Hydration of Substituted Alkynes at Room Temperature without Acidic Promoters. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74 (5), 2067–2074. 10.1021/jo802558e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We performed preliminary hydration reactions at 40 °C without removing the precipitated AgCl, using [3] = 100 mM and adding 1 μL of water. See Supporting Information for more details.

- We attempted the hydration reaction of the cyclohexyl propargyl ester 3a using exclusively AgOTf as catalyst. The reaction did not proceed. This result supported that Ag(I) alone was not responsible for the observed catalysis of the hydration reaction.

- Burés J.; Larrosa I. Organic reaction mechanism classification using machine learning. Nature 2023, 613 (7945), 689–695. 10.1038/s41586-022-05639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C. A. Quantifying Intermolecular Interactions: Guidelines for the Molecular Recognition Toolbox. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43 (40), 5310–5324. 10.1002/anie.200301739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Han J.; Okoromoba O. E.; Shimizu N.; Amii H.; Tormena C. F.; Hammond G. B.; Xu B. Predicting Counterion Effects Using a Gold Affinity Index and a Hydrogen Bonding Basicity Index. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (21), 5848–5851. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a Ka = 100 M–1, considering the initial concentrations used in the kinetic experiments 50% of the catalyst would be involved in a 1:1 coordination complex with the oxygen atom of the lactam substrate 3c (β = 8.3). An increase of Ka to 1000 M–1 would produce the almost quantitative coordination of the catalyst.

- Notice the significant difference in HBA and Lewis base properties (β values) of alkene, alkyne, ketone, amide and N-oxide groups. This difference might explain that the complexes resulting from the coordination of the alkene and alkyne units to the Au(I) atom will be formed to a reduced extent in comparison to these involving the ketone, amide or N-oxide counterparts.

- DFT calculations at the BP86 d3-def2-SVP level of theory performed for the inclusion complexes [3a ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+, [3b ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ and [3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ showed a good agreement between calculated and experimental stability values: [3a ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ < [3b ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ < [3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ (see Supporting Information for details). However, computationally the relative order of stabilities for the [3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ and [3d ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ complexes was reversed compared to that determined experimentally. Most likely, the stability of [3c ⊂ 2in•Au(I)]+ was computationally overestimated owing to the simplification of the model used to determine the electronic energies of the complexes. In any case, experimentally and theoretically the more stable complexes produced the less reactive catalysts.

- The use of acetone as solvent inhibited the catalytic properties of 5·Au·OTf and 2in·Au·OTf in the hydration reaction of 3a. Most likely, an acetone molecule coordinates the Au(I) catalytic metal center through the carbonyl oxygen.

- Bai S.-T.; Sinha V.; Kluwer A. M.; Linnebank P. R.; Abiri Z.; Dydio P.; Lutz M.; de Bruin B.; Reek J. N. H. Effector responsive hydroformylation catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (31), 7389–7398. 10.1039/C9SC02558H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Li T.; Mudshinge S. R.; Xu B.; Hammond G. B. Optimization of Catalysts and Conditions in Gold(I) Catalysis—Counterion and Additive Effects. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121 (14), 8452–8477. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Kumar M.; Hammond G. B.; Xu B. Enhanced Reactivity in Homogeneous Gold Catalysis through Hydrogen Bonding. Org. Lett. 2014, 16 (2), 636–639. 10.1021/ol403584e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schießl J.; Stein P. M.; Stirn J.; Emler K.; Rudolph M.; Rominger F.; Hashmi A. S. K. Strategic Approach on N-Oxides in Gold Catalysis – A Case Study. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361 (4), 725–738. 10.1002/adsc.201801007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.