Abstract

Liver cancer is a common malignant tumor, and its incidence is increasing yearly. Millions of people suffer from liver cancer annually, which has a serious impact on global public health security. Licochalcone A (Lico A), an important component of the traditional Chinese herb licorice, is a natural small molecule drug with multiple pharmacological activities. In this study, we evaluated the inhibitory effects of Lico A on hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (HepG2 and Huh-7), and explored the inhibitory mechanism of Lico A on hepatocellular carcinoma. First, we evaluated the inhibitory effects of Lico A on hepatocellular carcinoma, and showed that Lico A significantly inhibited and killed HepG2 and Huh-7 cells in vivo and in vitro. Transcriptomic analysis showed that Lico A inhibited the expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), which induced ferroptosis. We confirmed through in vivo and in vitro experiments that Lico A promoted ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by downregulating SLC7A11 expression, thereby inhibiting the glutathione (GSH)-glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) pathway and inducing activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In this study, we suggest that Lico A is a potential SLC7A11 inhibitor that induces ferroptotic death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, thereby providing a theoretical basis for the development of natural small molecule drugs against hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: Licochalcone A, hepatocellular carcinoma, ferroptosis, ROS

Introduction

Liver cancer is a common malignant tumor. According to the global cancer statistics report released by the WHO in 2020, new liver cancer patients ranked sixth in the incidence of new cancers and third with an 8.3% mortality rate. 1 Liver cancer can be divided into primary liver cancer (PLC) and secondary hepatocytoma according to different primary sites. The incidence of PLC is high and it is difficult to treat, while secondary liver cell carcinoma is relatively rare, with most formed by metastasis of colorectal cancer. PLC can be classified as hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma, with hepatocellular carcinoma accounting for about 80% of all PLC. 2 The cause of liver cancer is closely related to liver disease which results in persistent damage to the liver, and 80% of liver disease is caused by external factors such as hepatitis B, long-term alcohol use, long-term contact with aflatoxin, among other factors, which are the most important causes of liver cancer. 3 Due to the lack of obvious early symptoms and fast development, by the time most patients feel uncomfortable, they have already reached the middle or late stage of liver cancer, when the cancer can no longer be resected and cured. Therefore, it is necessary to explore measures to prevent liver cancer.

At present, common treatment measures for liver cancer aim to reduce liver cancer cells through drug suppression or remove them by resection. 4 Drugs commonly used in clinical treatment include sorafenib, lenvatinib, regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab. However, liver cancer is not sensitive to chemotherapeutic drugs, and it is easy to produce resistance, while drug costs are high. Therefore, the development of efficient liver cancer drugs with low cost is essential. 5 Natural drugs were widely used to treat various diseases in the 19th century. From 1981 to 2014, 51% of 1211 new small molecule drugs approved worldwide were compounds from natural products. 6 Among them, natural compounds obtained from fruits and vegetables, such as polyphenols, flavonoids and carotene, can kill tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. 7 Existing studies have shown that natural antitumor drugs have the advantage of low toxic side effects, do not produce resistance, and are efficient and accurate.

A large number of studies have pointed out that natural drugs can kill cancer cells through different mechanisms, such as apoptosis, cell necrosis, autophagy and ferroptosis, to achieve the effect of inhibiting cancer cell proliferation. 8 Ferroptosis was defined as a new mechanism of cell death in 2012. Different from apoptosis and autophagy, ferroptosis is cell death that relies on iron and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Under the action of binary iron and ester oxygenase, a strong membrane lipid peroxidation and oxidation stress reaction occurs, producing selective permeability loss and cell death. 9 Ferroptosis can be considered a new type of cell death which has great research value in tumor treatment. Many cancer cells have been confirmed to be affected by ferroptosis, including colorectal cancer, 10 lung cancer, 11 and liver cell carcinoma. 12 The literature suggests that ferroptosis is closely related to the metabolic activity of glutathione, and that glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) is able to reduce lipid peroxides to non-toxic lipids, regulating cellular redox homeostasis and maintaining cellular activity. SLC7A11 is an important component of SystemXc-, and when SLC7A11 is inhibited, the uptake of cystine decreases, which in turn decreases the amount of glutathione (GSH).13,14 The synthesis of GPX4 requires GSH as a substrate. When cystine levels are reduced, it also leads to lower levels of GPX4, which induces cellular ferroptosis. 15

Lico A, a flavonoid with multiple pharmacological activities, is an important natural small molecule from the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Glycyrrhiza glabra. 16 Numerous studies have shown that Lico A has biological properties such as therapeutic immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activity, and antiviral and antiparasitic effects. 17 The present study examined Lico A for its inhibitory effect on liver cancer cells, and found that it can effectively suppress and kill liver cancer cells through ferroptosis. This study preliminarily clarifies the mechanism by which Lico A inhibits liver cancer cells, and provides the theoretical basis for using natural drugs to treat liver cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cells, Drugs and Animals

Liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Huh-7 were obtained from Wuhan Punosei Life Technology Co., Ltd., and were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Lico A (Cat# HY-N0372) and Ferrostatin-1 (ferroptosis inhibitor, Cat# HY-100579) were purchased from MedChemExpress. BALB/c nude mice (5 weeks old) were purchased from Beijing Viton Lihua Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.

Cellular Activity Analysis

After diluted HepG2 and Huh-7 cells (5 × 103 cells per well) were plated in 96-well plates, increasing concentrations of Lico A were added for 24 or 48 hours of incubation, while the control group received diluent only. Cell activity was analyzed using a CCK-8 detection kit (Cat#C0038, Beyotime Biotechnology).

Crystalline Violet Staining

HepG2 and Huh-7 were plated in 6-well plates for 12 hours and then treated with increasing concentrations of Lico A. After 48 hours incubation, the cells were stained with crystalline violet at room temperature for 30 minutes, then washed 3 times in PBS before photography and analysis.

Wound-Healing Assay

After the HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were plated in 6-well plates for 12 hours, wound-healing assays were performed after Lico A at different concentrations was added for 48 hours. The assays were performed with detection and analysis methods reported in previous studies. 18

Flow Cytometry

HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were passaged in 12-well plates, incubated at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 cell incubator for 12 hours, and then treated with increasing concentrations of Lico A. Meanwhile, a control group was treated with diluent only. After 24 hours of culture, the cells from each group were collected and stained using an Annexin V-FITC/PI detection kit (Cat#556547, BD Biosciences). The cells were washed 3 times with PBS and assayed by flow cytometry (BD AccuriC6 Plus, BD).

Western Blot (WB)

HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Lico A for 24 hours. The cells were then collected and total protein was extracted using a protein extraction kit (Cat#DE101-01, TransGen Biotech). A total of 25 μg protein per lane was resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by transfer onto PVDF membranes. After incubation for 40 minutes with blocking solution (Cat#P0252, Beyotime Biotechnology), the cells were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4℃. Secondary antibody incubation was then performed for 40 minutes at room temperature. Finally, proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. The gray analysis was performed at the end of WB using Image J software and the process analysis was repeated 3 times. In the SLC7A11 overexpression experiment, 2 μg of overexpression plasmid (pcDNA3.1-SLC7A11) was transfected into cells. The pcDNA3.1-SLC7A11 plasmids were purchased from Public Protein/Plasmid Library (Cat# BC012087). The antibodies to SLC7A11 (Cat# 12691S), GPX4 (Cat# 59735S), and β-Tubulin (Cat# 2146S) used for WB were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Iron Assay

HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were plated in 6-well plates and then co-cultured with different concentrations of Lico A for 24 hours before cell collection. According to the instructions of the iron content assay kit, iron assay buffer was added at 4× the cell volume, and the cells were quickly homogenized and then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes. The supernatant was collected, and the Fe2+ content was determined according to the kit instructions. The iron assay kit was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat# MAK025)

Transcriptomic Analysis

HepG2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates 12 hours before experiments, then treated with Lico A (30 μM) for 48 hours. The cells were collected for transcriptomic analysis. Total RNA extraction was performed on cells treated with Lico A. The extracted total RNA was then subjected to a sample quality check, and samples passing the check were subjected to PCR to obtain cDNA libraries. RNA concentration and purity was measured using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The concentration is ≥25 (ng/µL), while the OD260/280 is 1.7-2.5 and the OD260/230 is 0.5-2.5. Quality-checked libraries were sequenced in PE150 mode with the Illumina NovaSeq6000 sequencing platform. Transcriptomic analysis was performed using the assay analysis service provided by Biomarker Technologies, Inc.

Electron Microscopic Observations

HepG2 cells were plated in 6-well plates for 12 hours, then treated with Lico A (30 μM) for 48 hours. Cells were collected by centrifugation, and mung bean-sized cell clumps could be seen at the bottom of the tubes, and the culture medium was discarded and added to electron microscope fixative for overnight fixation at 4℃. After fixation, the cells were rinsed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer PBS (PH7.4) for 3 times, each time for 15 minutes, and the fixed cell clusters were subjected to alcoholic dehydration-permeabilization-embedded sequentially. At the end of embedding, the sections were cut into 60 to 80 nm ultrathin sections and double-stained using 2% uranyl acetate-lead citrate. At the end of staining, the cells were observed under a transmission electron microscope and images were collected for analysis.

GSH Assay

HepG2 and Huh-7 were plated in 6-well plates for 12 hours and then treated with increasing concentrations of Lico A. After 24 hours of culture, the cells were collected for glutathione (GSH) analysis, using a GSH assay kit (Cat#S0053, Beyotime Biotechnology).

ROS and Lipid Peroxidation Assay

HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were treated with different concentrations of Lico A. After 24 hours of culture, the cells were collected for ROS and lipid peroxidation assays, using an ROS assay kit (Cat#S0033S, Beyotime Biotechnology) and lipid peroxidation probe Liperfluo (Cat# L248, Dojindo Laboratories).

Mouse Tumor Model

After 5 days of adaptation, SPF-grade BALB/c nude mice (5 weeks old) were injected subcutaneously with 100 μL of cell suspension (3 × 106 cells) containing HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. After 7 days, the experimental groups were given Lico A (10 and 20 mg/kg) every 3 days by intratumoral administration, while the control group was given the same volume of PBS. On day 21 after cell inoculation, the mice were euthanatized and the tumors were dissected for subsequent analysis. The collected tumor tissues were subjected to immunohistochemistry as described in previous studies. 18

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v9.0. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and groups were compared with t-tests. Univariate and multivariate ANOVAs were used to evaluate between-group differences. Significance levels were defined as *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001.

Results

Lico A Reduces the Viability of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells

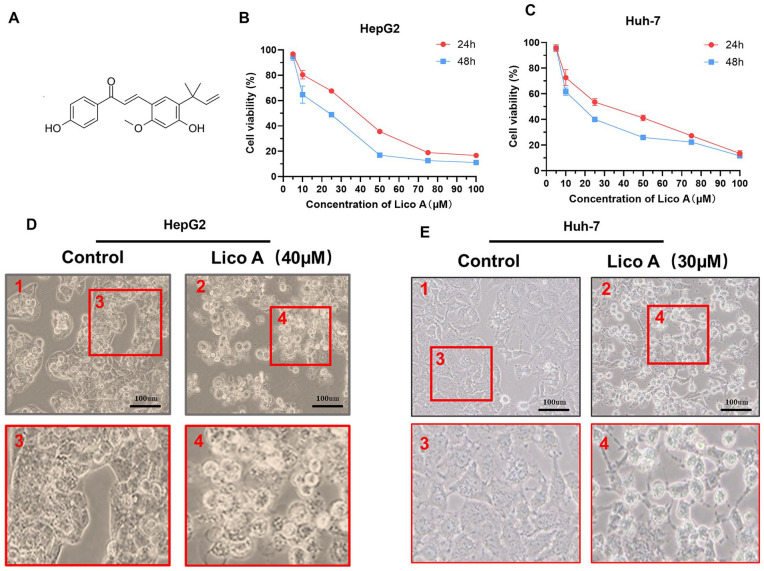

The viability of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells was analyzed using a CCK-8 kit after treatment with increasing concentrations of Lico A (Figure 1A). After HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were treated with Lico A for 24 and 48 hours, cellular activity was determined, as shown in Figure 1B and C. After HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were treated with Lico A for 24 hours, light microscopic observations showed that Lico A could effectively inhibit HepG2 and Huh-7 cell proliferation (Figure 1D and E). Therefore, the above results showed that Lico A can effectively reduce the viability of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells.

Figure 1.

Lico A reduces the viability of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. (A) Chemical structure of Lico A. Analysis of cellular activity of HepG2 (B) and Huh-7 (C) cells treated with different concentrations of Lico A for 24 and 48 hours. Micrographs of HepG2 (D) and Huh-7 (E) cells treated with Lico A. The results are presented as means ± standard deviation.

Lico A Inhibits Liver Cancer Cell Proliferation and Promotes Cell Death

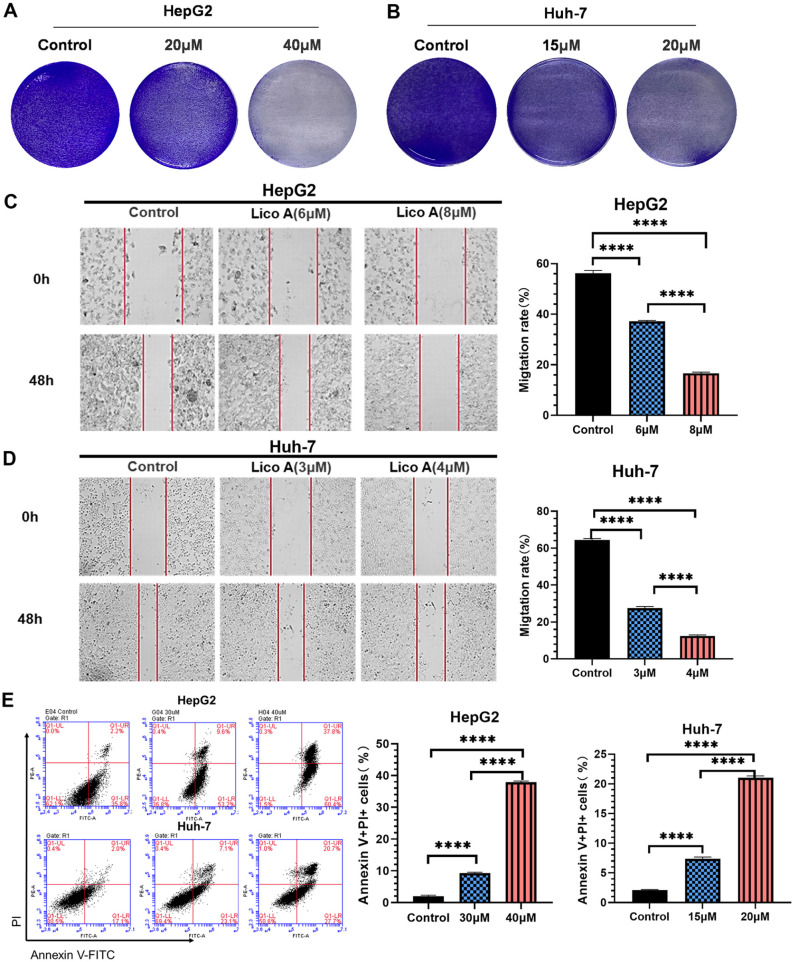

Crystalline violet staining, wound-healing assays and Annexin V assay analysis were performed after HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Lico A. The results of crystalline violet staining showed that with the increase in Lico A concentration, the ability to kill HepG2 (Figure 2A) and Huh-7cells (Figure 2B) was enhanced. The wound-healing assay showed that Lico A could effectively inhibit the proliferation of HepG2 and Huh-7cells. The average rate of HepG2 coverage of clear areas in the Lico A untreated group was 56.3%. In contrast, the average coverage of HepG2 cells treated with 6 or 8 µM Lico A was 37.2% or 16.7%, respectively (Figure 2C). The average rate of HepG2 coverage of clear areas in the Lico A untreated group was 64.5%. In contrast, the average coverage of HepG2 cells treated with 3or 4 µM Lico A was 27.5% or 12.4%, respectively (Figure 2D). The above results indicated that the proliferative capacity of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells decreased significantly with increasing Lico A concentration. After LicoA treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma cells, Anexin V/PI assay was analyzed by flow cytometry, and the experimental results Anexin V-FITC-/PI- indicated live cells, while Anexin V-FITC+/PI+ indicated dead cells. The results of Annexin V assays showed that as the concentration of Lico A increased, the mortality of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells also increased significantly (Figure 2E). The above results thus demonstrated that Lico A can induce HepG2 and Huh-7 cell death and inhibit their proliferation.

Figure 2.

Lico (A) inhibits liver cancer cell proliferation and promotes cell death. Crystal violet staining of HepG2 (A) and Huh-7 (B) cells treated with Lico A. Wound-healing assays of HepG2 (C) and Huh-7 (D) cells treated with Lico A. (E) Percentage of dead HepG2 and Huh-7 cells (stained with Annexin V+/PI+). Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (****P < .0001).

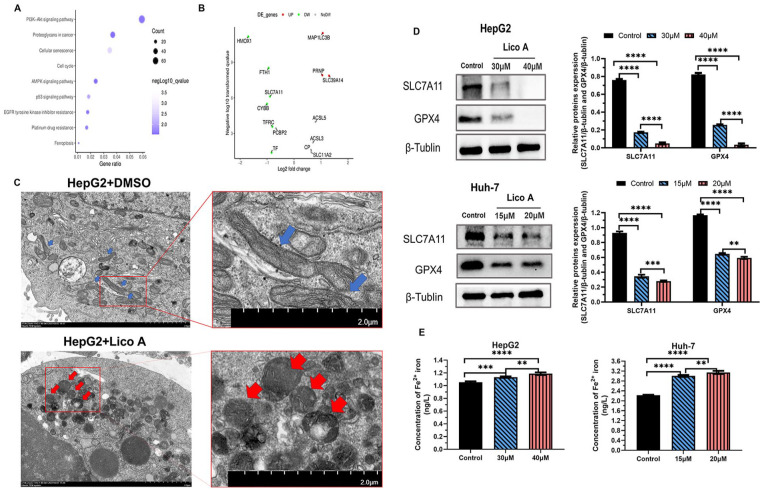

Lico A Can Induce Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells

After HepG2 cell treatment with Lico A, transcriptomics analysis was performed. The transcriptomics data showed that Lico A activated a variety of tumor-related pathways (Figure 3A). Among them, we found that the ferroptosis pathway was activated, so we analyzed the expression of genes related to ferroptosis. The results showed that the expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) decreased significantly (Figure 3B). Therefore, we speculated that Lico A promoted ferroptosis of liver cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of SLC7A11. Electron microscopic observations (Figure 3C) revealed that HepG2 produced significant features of ferroptosis in the mitochondria after Lico A treatment, including smaller mitochondrial volume, contraction of the outer bilayer, thickening of ridges and increased membrane density. In order to further verify our hypothesis, we carried out WB to analyze the impact of Lico A on SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression. The results showed that after the Lico A treatment of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells, the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 was significantly reduced (Figure 3D). We simultaneously analyzed the Fe2+ iron content in each experimental group. The Fe2+ iron content significantly increased in Lico A-treated hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Figure 3E). The above results thus showed that Lico A can effectively inhibit the expression of SLC7A11.

Figure 3.

Lico A can induce ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. (A) Transcriptomics analysis of HepG2 cells after treatment with Lico A. (B) Expression of ferroptosis-related genes in HepG2 cells after treatment with Lico A. (C) Transmission electron microscopy (blue and red arrows designate cellular mitochondria). (D) Expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 protein after Lico A treatment. (E) Analysis of Fe2+ iron content after Lico A treatment. Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (**P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001).

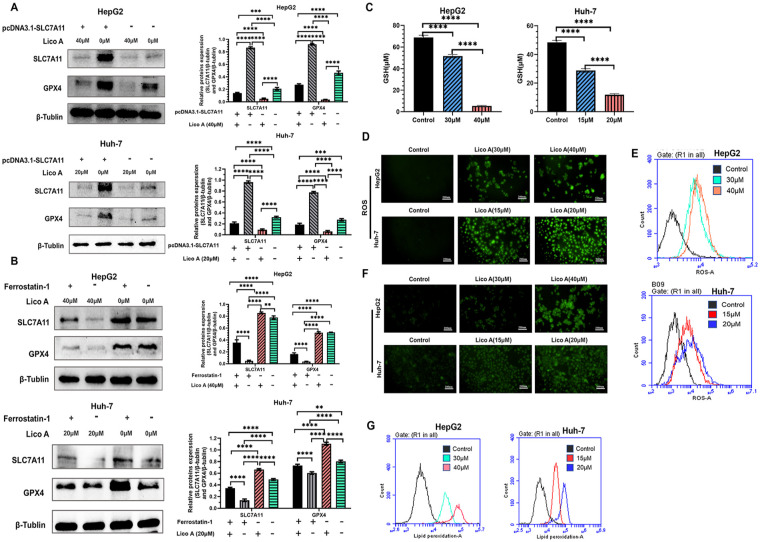

Lico A-Induced Ferroptosis Depends on the SLC7A11/GPX4 Pathway and Activation of ROS

Numerous studies have shown that the SLC7A11/glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) pathway is one of the pathways that induces ferroptosis in cells. 19 Therefore, we analyzed the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins after Lico A treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by performing WB. Overexpression plasmid (pcDNA3.1-SLC7A11) was transfected into HepG2 and Huh-7 cells and then treated with Lico A. The WB assay results showed that the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins decreased significantly after Lico A treatment (Figure 4A). We then treated hepatocellular carcinoma cells with a ferroptosis inhibitor (Ferrostatin-1) together with LicoA, and observed that the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins also significantly decreased after Lico A treatment (Figure 4B). Previous studies have indicated that GSH is an important component of the GPX4 inhibitory cellular ferroptosis pathway, 19 so we performed GSH content measurements. The results showed that expression of GSH was inhibited in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells under the effect of Lico A (Figure 4C). Inactivation of GPX4 is often accompanied by an imbalance in intracellular redox homeostasis, 19 so we further analyzed the levels of lipid peroxidation and ROS. The results showed that Lico A significantly increased ROS levels in the cells (Figure 4D and E). The results of lipid peroxidation analysis showed that Lico A-treated cells had a large accumulation of lipid peroxides and the level increased with increasing Lico A concentration (Figure 4F and G). Therefore, we hypothesized that Lico A could promote ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting the SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway and activating ROS.

Figure 4.

Lico A-induced ferroptosis depends on the SLC7A11/GPX4/ROS pathway. (A) Expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins after HepG2 and Huh-7 cells overexpressing SLC7A11 were treated with Lico A. (B) Expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins after treatment of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells with Lico A and Ferrostatin-1. (C) Detection of GSH levels in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells treated with Lico A. (D) Fluorescence microscopy to observe the level of ROS in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. (E) Flow cytometry was used to detect ROS levels in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. (F) Fluorescence microscopy to observe the level of lipid peroxidation in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. (G) Flow cytometry was used to detect lipid peroxidation levels in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (**P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001).

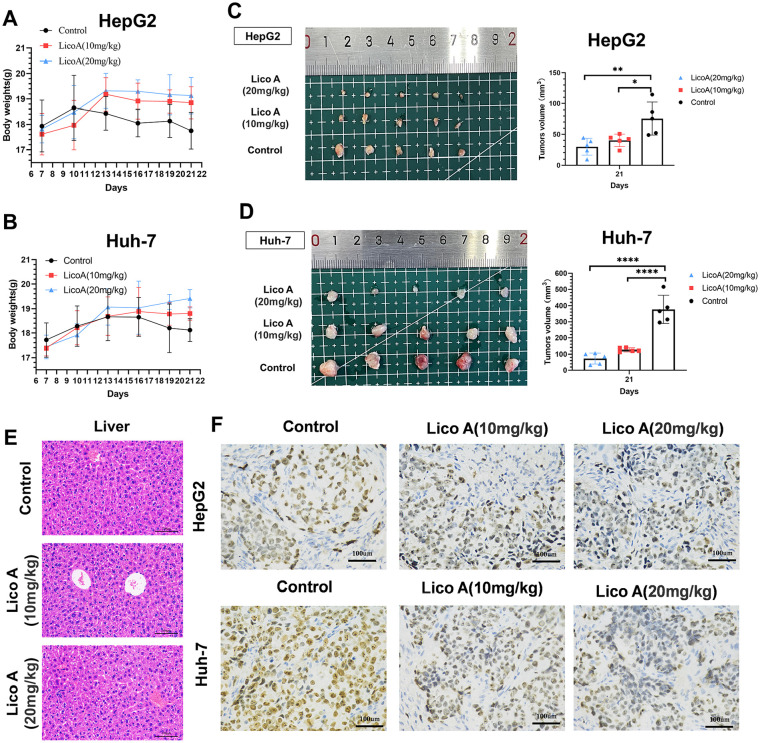

Inhibitory Effect of Lico A and Induced Ferroptosis In Vivo

To explore the inhibitory effect of Lico A on hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vivo, we analyzed the effect of Lico A in a mouse tumor model. After the in vivo treatment of mice with Lico A, the mice in the Lico A treatment group had higher body weights than the control group (Figure 5A and B). After euthanizing the mice and removing the tumors for analysis, we found that the tumor size in the Lico A treatment group was significantly smaller than in the control group (Figure 5C and D), which demonstrated that Lico A could effectively inhibit the proliferation of liver cancer cells. We took liver tissues for hematoxylin/eosin staining, and the results showed no evident pathological damage in the livers of mice treated with Lico A (Figure 5E). The tumor tissues were then pathologically analyzed, and the results of Ki67 assays showed that Lico A treatment could effectively inhibit the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Figure 5F). These results thus indicated that Lico A can effectively inhibit the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vivo.

Figure 5.

The antitumor effect of Lico A in vivo. Body weights (A and B), images of xenografted tumors (C and D) and tumor volumes (C and D) were recorded. (E) Hematoxylin/eosin staining was applied to detect pathological alterations in the liver produced by Lico A. (F) Analysis of Ki67 results from tumor samples. The results are presented as means ± standard deviation (*P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001).

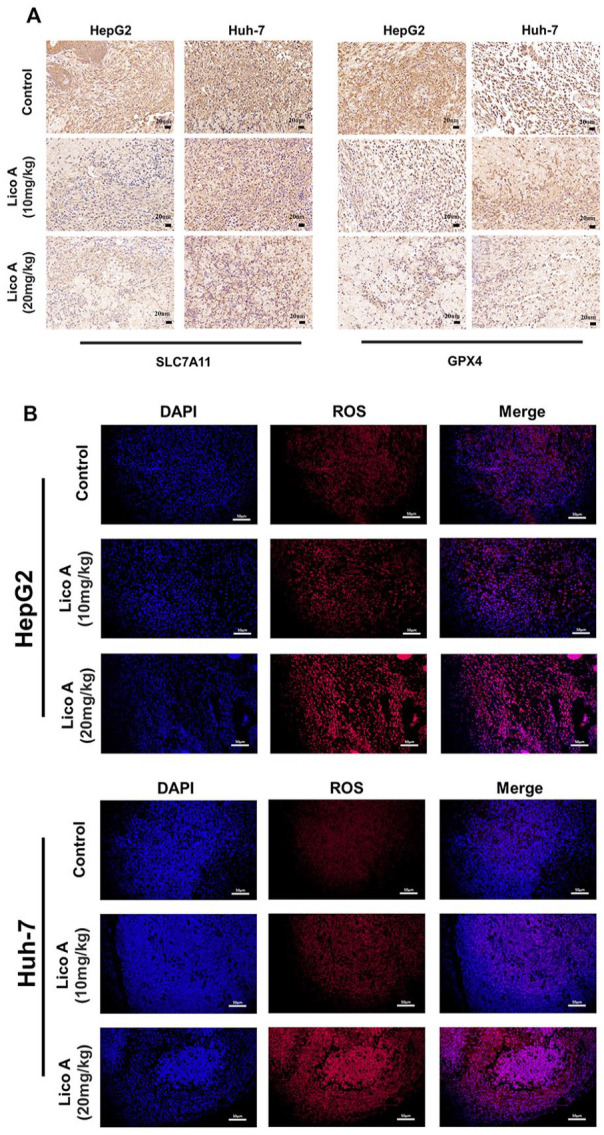

To further verify the function of Lico A in inducing ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vivo, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissues. We analyzed the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins in tumor tissues (Figure 6A), and the results showed that the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins in tumor tissues from the Lico A treatment group was significantly lower than in the control group. We also analyzed the level of ROS in tumor tissues, and the results were similar to the in vitro results, showing that ROS in tumor tissues was significantly increased in the Lico A treatment group (Figure 6B). Taken together, these results suggest that Lico A induces ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma via the SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway and activated ROS.

Figure 6.

Effects of Lico A on protein expression and ROS levels in hepatocellular carcinoma in vivo. (A) Immunohistochemistry was used to detect the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins from tumor samples. (B) Levels of ROS from tumor samples, red fluorescence represents ROS levels, and blue fluorescence represents DAPI.

Discussion

Liver cancer is a life-threatening tumor disease, and with its incidence increasing yearly, it is expected to occur in more than 1 million people in 2025. 20 Because liver cancer is not easily detected in the early stage and develops rapidly, patients have frequently passed the optimal treatment period when they are diagnosed. At that point, the proliferation of liver cancer cells can only be suppressed by drugs unless surgery can be performed. 4 Natural small molecule drugs are mainly derived from natural plants, and a large number of natural small molecule drugs are already being widely used in the clinic, such as paclitaxel and vincristine. Existing studies have shown that natural antitumor drugs offer the advantages of low toxic side effects, less drug resistance, as well as high efficiency and precision. Therefore, research on natural small molecule drugs targeting effective prevention and treatment of liver cancer is necessary.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of cell death characterized by elevated intracellular ROS. Studies are increasingly indicating that some components of traditional Chinese medicine regulate ferroptosis in cancer cells by targeting different genes. Artemisinin has been demonstrated to modulate more than 20 ferroptosis-related genes, thereby inducing iron death in tumor cells. 21 Piperlongumine induces intracellular ROS accumulation in human pancreatic cancer through ferroptosis, thus leading to tumor death. 22 Erianin induces ferroptosis in lung cancer cells through upregulation of ROS as well as GSH depletion. 11 Caryophyllene oxide induces ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through regulation of the NCOA4/FTH1/LC3 pathway. 18 In addition, β-elemene, 23 Actinidia chinensis Planch (ACP), 24 and Piperlongumine 22 have been found to promote ferroptosis by inhibiting the activity of SLC7A11. In conclusion, traditional Chinese medicine components may potentially serve as therapies for tumors by inducing ferroptosis in cancer cells.

Previous studies have shown that Lico A is also a natural small-molecule drug that can inhibit a variety of cancers, and it has been effective in inhibiting myeloma, cholangiocarcinoma, lung cancer, colon cancer, and other tumor diseases. 25 Therefore, Lico A may be an ideal natural small molecule drug against liver cancer. In this study, we explored the effects of Lico A on 2 hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines, HepG2 and Huh-7. The results of in vitro experiments showed that Lico A could effectively inhibit and kill the proliferation of both cell lines (Figures 1 and 2). We also conducted an in vivo study on the inhibitory effect of Lico A on hepatocellular carcinoma, and the results in a mouse tumor model were consistent with the in vitro study results (Figure 5). Combining the results of in vivo and in vitro experiments, further demonstrating that Lico A could effectively inhibit the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma subserosa cells.

In this study, we treated HepG2 cells with Lico A and performed transcriptomic analysis as well as electron microscopic observations, The results of transcriptomic analysis revealed that Lico A treatment of HepG2 cells could activate various cancer-related pathways (Figure 3A), including the ferroptosis pathway. We analyzed the changes of genes in the ferroptosis pathway and found that Lico A could downregulate the expression of SLC7A11 (Figure 3B), a key protein in the ferroptosis regulatory pathway, so we hypothesized that Lico A might induce ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting expression of the SLC7A11 protein. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of SLC7A11 protein by WB (Figure 3D), and the detection results were consistent with the transcriptomic analysis. Electron microscopic observations showed that mitochondria displayed typical features of ferroptosis after Lico A treatment of HepG2 cells (Figure 3C), and these morphological changes indicated that the cells were undergoing ferroptosis, which further confirmed our hypothesis. In addition, we analyzed the concentrations of Fe2+ after Lico A treatment of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. The Fe2+ concentration increased with increasing LicoA concentration (Figure 3E). Therefore, Lico A may induce ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the inhibition of SLC7A11. In addition, we also detected the proteins related to cellular pyroptosis and apoptosis by WB, and the results showed that there was no significant change in the expression of GSDMD, GSDME, and PARP, etc (Supplemental Figure S1). The above results suggest that Lico A-induced cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells may not be related to cellular pyroptosis and apoptosis.

SystemXc- is an amino acid transport complex consisting of 2 protein subunits, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2, whose main function is to transport cystine for synthesis of the antioxidant GSH.13,14 The main activity of SystemXc- depends on the expression of SLC7A11.13,14 Inhibitors of SLC7A11 are the most commonly used inducers of ferroptosis. Several drugs, such as Erastin and sorafenib, have been identified to inhibit SLC7A11 activity and consequently induce cell ferroptosis.26,27 Numerous studies have shown that SLC7A11 is associated with poor prognosis in various cancers.28 -30 Therefore, SLC7A11 may be a potential target for the development of therapeutic agents for oncology. GPX4 is an important negative regulator of lipid peroxidation protein. GPX4, as a key factor in ferroptosis, plays an important role in balancing the redox levels inside cells, and ferroptosis cannot occur without a decrease in GPX4 activity. The reduction of GPX4 activity can disrupt the redox balance in cells, which leads to a series of reactions such as increased ROS and lipid peroxides, and ultimately leads to ferroptosis. 31 When GPX4 protein is inhibited, accumulated lipid peroxidation leads to an iron-dependent, non-apoptotic cell death called ferroptosis. 32 Several studies have indicated that cancer cells are effectively killed during cancer treatment when GPX4 function is absent or ferroptosis inducers are present. 33 Therefore, the SLC7A11/GPX4 pathways may be a promising research direction for the development of antitumor drugs.

To provide further verification, we determined that Lico A induced ferroptosis by inhibiting the SLC7A11//GPX4 pathway. We performed validation experiments by overexpressing SLC7A11 protein (Figure 4A) or adding a ferroptosis inhibitor (Ferrostatin-1) (Figure 4B), respectively, and found that Lico A inhibited the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4. SLC7A11 in the SystemXc- amino acid antiporter is highly specific for cystine and glutamate as the functional subunit of SystemXc-, which is involved in the synthesis of GSH to maintain the intracellular redox balance. 34 SLC7A11 down-regulation leads to the inhibition of SystemXc-transport function; the cellular uptake of cystine is diminished, and GSH synthesis is blocked or even depleted. 19 Therefore, we examined the GSH content of cells after Lico A treatment with a GSH assay kit, and the results showed a significant decrease in GSH content (Figure 4C). GSH also acts as a reducing cofactor for GPX4, so we analyzed the expression of GPX4 by WB in vitro (Figure 3D) and in vivo (Figure 6A), and the results showed that GPX4 expression after Lico A treatment was significantly lower. Ferroptosis, as a programed death mode different from apoptosis and cell necrosis, is closely related to oxidative stress. GPX4 is a member of the cellular peroxidase family, and when GPX4 activity is reduced or inactivated, peroxides inside the cell cannot be reduced, ROS will be rapidly increased and a large amount of lipid peroxides will be formed, which eventually leads to cell death. 35 Therefore, we analyzed the changes in ROS and lipid peroxide levels after the action of Lico A on hepatocellular carcinoma cells. The results showed that the levels of ROS (Figure 4D and E) and lipid peroxides (Figure 4F and G) were significantly increased after the action of Lico A. Existing studies have shown that large amounts of lipid peroxides cannot be reduced in a timely manner, resulting in the production of large quantities of toxic substances during catabolism of the cell membrane, accompanied by continuous oxidation reactions on the membrane, so that eventually the structure of the cell membrane is damaged, eventually leading to ferroptosis. 36 In summary, Lico A can induce ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by activating ROS through the SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway.

This study has several limitations. Transcriptomic analysis of HepG2 cells treated with LicoA has indicated that Lico A activates several tumor-related pathways, such as the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, AMPK signaling pathway, and P53 signaling pathway; however, only ferroptosis-related pathways were investigated in this study. Some studies have suggested that the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway 37 and P53 signaling pathway 38 might also be involved in the regulation of ferroptosis in cancer cells. A shortcoming of the present study is that it did not address those related studies. We will further explore the relationships among other signaling pathways activated by LicoA and ferroptosis in future studies.

In this study, we found that Lico A could effectively inhibit the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vivo and in vitro. In addition, we identified a novel mechanism of Lico A which mediates hepatocellular carcinoma death. This mechanism induces ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting down-regulation of SLC7A11 protein expression, which in turn inhibits the SystemXc-GSH-GPX4 pathway. Therefore, this study has provided a new theoretical basis for the development of anti-hepatocellular carcinoma drugs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-ict-10.1177_15347354231210867 for Licochalcone A Induces Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Reactive Oxygen Species Activated by the SLC7A11/GPX4 Pathway by Jin-Xin Zhang, Yan Xiao, Yi-Quan Li, Yi-Long Zhu, Ya-Ru Li, Ren-Shuang Zhao, Ning-Yi Jin, Jin-Bo Fang, Xiao Li and Ji-Cheng Han in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Acknowledgments

We thank International Science Editing (https://www.internationalscienceediting.com) for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Data Availability: All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province [Grant No. YDZJ202201ZYTS254], and the Scientific Research Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Education [Grant No. JJKH20220889KJ], and the Young Scientist Program Training Program of Changchun University of Chinese Medicine [Grant No. QNKXJ2-2021ZR31].

ORCID iD: Ji-Cheng Han  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1869-3605

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1869-3605

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Malik IA, Rajput M, Werner R, et al. Differential in vitro effects of targeted therapeutics in primary human liver cancer: importance for combined liver cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qian JY, Gao J, Sun X, et al. KIAA1429 acts as an oncogenic factor in breast cancer by regulating CDK1 in an N6-methyladenosine-independent manner. Oncogene. 2019;38(33):6123-6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73(Suppl 1):4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haber PK, Puigvehí M, Castet F, et al. Evidence-based management of hepatocellular carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (2002-2020). Gastroenterology. 2021;161(3):879-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod. 2020;83(3):770-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kubczak M, Szustka A, Rogalińska M. Molecular targets of natural compounds with anti-cancer properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:13659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akhtar MF, Saleem A, Rasul A, et al. Anticancer natural medicines: an overview of cell signaling and other targets of anticancer phytochemicals. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;888: 173488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cong T, Luo Y, Fu Y, et al. New perspectives on ferroptosis and its role in hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Med J. 2022;135(18):2157-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang L, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Fan Z. Mechanism and application of ferroptosis in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;158:114102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen P, Wu Q, Feng J, et al. Erianin, a novel dibenzyl compound in Dendrobium extract, inhibits lung cancer cell growth and migration via calcium/calmodulin-dependent ferroptosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen J, Li X, Ge C, Min J, Wang F. The multifaceted role of ferroptosis in liver disease. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(3):467-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bannai S. Exchange of cystine and glutamate across plasma membrane of human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(5):2256-2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakamura E, Sato M, Yang H, et al. 4F2 (CD98) heavy chain is associated covalently with an amino acid transporter and controls intracellular trafficking and membrane topology of 4F2 heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(5):3009-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D. Ferroptosis: machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 2021;17(9):2054-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Freitas KS, Squarisi IS, Acésio NO, et al. Licochalcone A, a licorice flavonoid: antioxidant, cytotoxic, genotoxic, and chemopreventive potential. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2020;83(21-22):673-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu X, Xiong Y, Shi Y, et al. In vitro activities of licochalcone A against planktonic cells and biofilm of Enterococcus faecalis. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:970901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiu Z, Zhu Y, Han J, et al. Caryophyllene oxide induces ferritinophagy by regulating the NCOA4/FTH1/LC3 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:930958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou Y, Shen Y, Chen C, et al. The crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis: what can we learn to target drug resistance in cancer? Cancer Biol Med. 2019;16(4):630-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ooko E, Saeed ME, Kadioglu O, et al. Artemisinin derivatives induce iron-dependent cell death (ferroptosis) in tumor cells. Phytomedicine. 2015;22(11):1045-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamaguchi Y, Kasukabe T, Kumakura S. Piperlongumine rapidly induces the death of human pancreatic cancer cells mainly through the induction of ferroptosis. Int J Oncol. 2018;52(3):1011-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen P, Li X, Zhang R, et al. Combinative treatment of β-elemene and cetuximab is sensitive to KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Theranostics. 2020;10(11):5107-5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gao Z, Deng G, Li Y, et al. Actinidia chinensis planch prevents proliferation and migration of gastric cancer associated with apoptosis, ferroptosis activation and mesenchymal phenotype suppression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;126:110092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shu J, Cui X, Liu X, et al. Licochalcone A inhibits IgE-mediated allergic reaction through PLC/ERK/STAT3 pathway. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2022;36:3946320221135462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, et al. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(-) in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(5):522-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine–glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife. 2014;3:e02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ji X, Qian J, Rahman SMJ, et al. XCT (SLC7A11)-mediated metabolic reprogramming promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression. Oncogene. 2018;37(36):5007-5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang L, Huang Y, Ling J, et al. Overexpression of SLC7A11: a novel oncogene and an indicator of unfavorable prognosis for liver carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2018;14(10):927-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Timmerman LA, Holton T, Yuneva M, et al. Glutamine sensitivity analysis identifies the xCT antiporter as a common triple-negative breast tumor therapeutic target. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(4):450-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Forcina GC, Dixon SJ. GPX4 at the crossroads of lipid homeostasis and ferroptosis. Proteomics. 2019;19(18):e1800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, et al. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death Nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hangauer MJ, Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, et al. Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature. 2017;551(7679):247-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sun S, Guo C, Gao T, et al. Hypoxia enhances glioma resistance to sulfasalazine-induced ferroptosis by upregulating SLC7A11 via PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α axis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:7862430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Y, Wang Y, Liu J, Kang R, Tang D. Interplay between MTOR and GPX4 signaling modulates autophagy-dependent ferroptotic cancer cell death. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021;28(1-2):55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pan L, Gong C, Sun Y, et al. Induction mechanism of ferroptosis: A novel therapeutic target in lung disease. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1093244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yi J, Zhu J, Wu J, Thompson CB, Jiang X. Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(49):31189-31197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520(7545):57-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-ict-10.1177_15347354231210867 for Licochalcone A Induces Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Reactive Oxygen Species Activated by the SLC7A11/GPX4 Pathway by Jin-Xin Zhang, Yan Xiao, Yi-Quan Li, Yi-Long Zhu, Ya-Ru Li, Ren-Shuang Zhao, Ning-Yi Jin, Jin-Bo Fang, Xiao Li and Ji-Cheng Han in Integrative Cancer Therapies