Abstract

Introduction

Coproduction of mental health research and interventions involving researchers and young people is increasingly common. However, this model raises challenges, related, for instance, to communication, power and control. This paper narrates—from a collective first-person perspective—the lived experience of coproduction of a digital intervention by institutional researchers and young citizen researchers in Brazil.

Method

This study employed a collaborative autoethnographic methodology, utilising autobiographical data such as meeting recordings, individual notes and collective guided reflections on the coproduction process. Our analysis focused on challenges and solutions that arose during the process.

Results

Throughout the project, we created formal and informal mechanisms for accountability, transparency and fair inclusion of multiple voices. We engaged in mutual capacity-building, invested in building interpersonal knowledge, and implemented practices to reduce overload and promote equitable participation. Through ongoing reflection and readjustment in response to challenges, we progressively embraced more democratic and egalitarian values. The collective care invested in the process fostered synergy, trust, and intergroup friendship.

Conclusion

Our experience points to the value of creating a space for multiple research identities: the citizen young person and the institutional researcher, both of whom critically reflect on their roles in the research process. Our focus on coproduced care calls into question participation metaphors that represent the process via a single axis—young people—who linearly progress from minimal participation to full autonomy. Instead, our analysis highlights the importance of a social and caring bond that supports the radical co-production of innovative health solutions in contexts of vulnerability.

Keywords: mental health & psychiatry, qualitative study, child health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Coproducing research with young people is gaining recognition in health research and intervention development, with various models proposed. However, there is a lack of understanding of the micro-level aspects of this collaborative approach, particularly in the Global South.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Our autoethnographic analysis revealed an immersive coproduction process characterised by flexibility, trust in the model and a commitment to nurturing the partnership. Care practices, addressing not just technical but also social and personal needs, enhanced synergy, equity and transparency.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Our project offers a fresh perspective on coproduction, emphasising the role of social bonds in driving innovative outcomes. This paves the way for more immersive, radical collaboration possibilities between researchers and young people in the development of health research and interventions.

Introduction

Coproduction, participatory research, peer research and citizen science are some of the terms used within a large body of emerging concepts and models that advocate public participation in research and require new skills and ways of producing and communicating knowledge.1 2 The benefits of citizen participation in health research have been increasingly recognised for both the research and the public who participate. Citizen participation in research can give health interventions more relevant objectives, make their content more appropriate to local needs, generate more feasible implementation strategies and lead to more beneficial outcomes.3–5 For those ‘researched’, it can promote the human right to participate in processes concerning them.6 7 On the other hand, this way of doing research may require more skills and resources, including financial resources, relational skills and time.8 9

In this article, we will adopt the term coproduction, defined as a way of doing research in which ‘researchers, practitioners and members of the public work together, sharing power and responsibility from the start to the end of the project’.10(p.1) It is expected to drive more egalitarian, democratic or transparent research processes, which more effectively address the needs of patients, service users and/or marginalised citizens.11 In a co-production process, different stakeholders bring their skills, life experiences and social roles to the table. Together they develop the various stages of research, such as idea generation, funding acquisition, study design, management, data collection, analysis, evaluation and dissemination.

Coproduction is an increasingly popular approach in health research; yet, while there is a growing body of published work in the Global North or high-income countries, there is comparatively little documented in the Global South or low and middle-income countries (LMICs).12 When it comes to the coproduction of research with young people, a systematic literature review identified studies conducted exclusively in European countries, the USA and Australia.13 The available evidence is even more limited when considering research on mental health interventions coproduced with young people; only two studies were found during a systematic review of literature on the codesign of mental health services.14 Codesign of digital mental health tools with young people seem more frequent, with 25 original articles identified in a recent review, although none of these was from the Global South.15

In both the Global North and the Global South, the meeting of heterogeneous actors (eg, academic researchers and young people who have not completed higher education) is known to pose a number of challenges, especially those related to power dynamics.16–18 Researchers have emphasised the importance of building and maintaining reciprocal and trusting relationships, sharing power and valuing different skills, knowledge and perspectives, to overcome these challenges.10 19 Nevertheless, there is a need to better understand the microprocesses that unfold in the context of research coproduction and how teams overcome challenges in practice. This article aims to expand our knowledge about coproduction processes in research on youth mental health, by bringing together the voices of young people and academic researchers.

The setting for this study was Brazil, where coproduction methods have been used to drive innovation in public services20 and public policy design21 22 but not in the field of youth mental health. In recent years, the country has faced deepening social inequality, children’s rights’ violations and democratic fragility.23 Adolescents have been particularly badly affected, with a sevenfold loss of income between 2014 and 2019, surpassing the average loss for traditionally excluded groups—illiterate individuals, those of Black ethnicity and residents of the North and Northeast regions of the country.24 Their quality of life was further worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.25 During the pandemic and even after social distancing restrictions were lifted in Brazil, adolescents in high school were the group that struggled the most with mental health issues.26 A case that featured on national TV gave an emblematic example of this: twenty-six students in a state school had a simultaneous crying fit, along with shortness of breath and body tremors. The students were rescued by the Mobile Emergency Care Service, which reported a ‘collective anxiety crisis’,27 prompting a debate around the need for school-based interventions.

In this paper, we, a team of academic researchers and young people, offer an in-depth autoethnographic account of our experience of coproducing a digital capacity-building intervention to support Brazilian young people’s participation in promoting good mental health, optimised for use in schools. The intervention was based on digital storytelling and consisted of a ‘chat-story’: a virtual experience in which a narrative unfolds as users interact with fictional characters on a text-messaging platform through dialogue, audio recordings, videos and memes. The narrative was based on real-life stories of Brazilian adolescents collected during a mapping phase. Developing this tool required the symbiotic integration of multiple kinds of expertise, including academic/scientific experience, lived experience and technical and creative skills. Our team experienced several challenges during this process, and collectively and iteratively developed solutions to them. The purpose of this article is to reflect on these challenges, realignments and unplanned learnings, providing a rich description of how coproduction might unfold in practice. We hope that our analysis inspires new ways of promoting coproduction with young people, especially in LMICs.

Autoethnography

Researchers participating in a social process that is being studied find in autoethnography a methodological tradition for structuring immersive experiences into shareable knowledge. The main pillar of this approach is the personal biography, an author’s personal experience, which serves as the primary source of information.28 The term autoethnography first appeared in research belonging to the poststructuralist paradigm, where the researcher was part of the group being studied.29 However, autoethnography has evolved into diverse methodologies, all of which feature the open inclusion of the self, in effect the researcher’s own biography, in the investigation of social and cultural processes.30 31 The authors ‘scrutinize, publicize, and reflexively rework their own self-understandings as a way to shape understandings of and in the wider world’ (28, p1660). This paper is the result of ‘collaborative autoethnography’,32 whereby authors work collectively to observe and collect personal (group) experiences and interpret the data to understand a particular phenomenon. Participants’ identities are revealed, challenging their default position of anonymity traditionally held in social science research.

Methodology

Patient and public involvement

This autoethnography analyses the process of research coproduction, which is a type of patient and public involvement, from the first-person perspective of a team of academic researchers and young people. To better define our aims, we begin by describing our coproduction environment. As recommended by Das and colleagues,33 we outline three critical elements that characterise coproductive initiatives:

Who?—comprising the context in which the project was carried out and its actors.

…did what?—referring to the resulting product.

How?—referring to the nature of the collaboration and the way it unfolded.

Co-production context and actors (who?)

The coproduction took place as part of the Engajadamente Project.34 The project was the initiative of a Brazilian researcher at the University of Oxford, UK, GP, who invited a researcher at the University of Brasília (UnB), Brazil, SGM, and the technology company Talk2U (Brazil) to partner up on a project aimed at developing a chat-story enabling young people to participate in the promotion of good mental health. After securing funding from the British Academy Youth Futures Programme in collaboration with Oxford researcher IS, and establishing an international agreement, GP and SGM selected two postdoctoral researchers (FRS and JAdAM) to join the team as well as five young people (JAdAM, RRAdS, RdOdC, BTRS and VHdLS), who took the place of peers in the research. The selection criteria for the postdoctoral students included the following: academic expertise in young people’s mental health, intersectionality and/or social participation; international experience and the ability to work with non-academic partners. The young researchers were undergraduates from the UnB, selected on the basis of their age (under 21 years old); interest in or experiences related to mental health and community engagement; and experience of digital innovation and creative activities.

The selection procedures for all researchers were carried out online and included two phases. In the first phase, all applicants submitted resumés and letters of motivation, and the young applicants additionally submitted an original 1 min video aimed at teenagers about mental health and well-being. The shortlisted candidates were invited to an individual interview (postdoctoral researchers) or a group discussion on mental health and youth participation (young researchers), where the ability to work collaboratively as part of a team was also assessed.

Our core coproduction team, therefore, consisted of four academic researchers and five young people (see reflexivity statement in online supplemental appendix 1). The academic researchers—henceforth called ‘adult researchers’—had backgrounds in psychology, public health, communication and ethics. They were involved in projects promoting good mental health and young people’s rights and best interests, with academic careers ranging from 10 to 22 years in these fields. The young people—henceforth called ‘young researchers’ (a term they chose themselves)—were aged between 17 and 20 at the time of recruitment and were studying political science, social sciences or psychology as undergraduates. Both groups included a range of gender identities, sexual orientations and ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, including individuals with lived experience of poverty and mental health challenges. All the researchers were Brazilian and native Portuguese speakers.

bmjgh-2023-012443supp001.pdf (75KB, pdf)

The core coproduction team collaborated closely with Talk2U, a company that pioneered the concept of ‘chat-stories’ and has in its portfolio several such tools, covering issues related to migration, climate change, violence and mental health.35 Talk2U co-developed the chat-story script and led the technological and audio-visual development. Several other stakeholders, including young people, education professionals, policymakers and professionals in the creative industries, were also recruited, constituting an extended co-production network.

Co-produced results (what was done?)

The main product derived from the coproduction process was a chat-story, a gamified narrative intervention aimed at supporting young people to promote mental health in Brazilian high schools. In particular, the tool was designed to build young people’s skills when it came to supporting their peers (eg, by using empathetic listening or recognising signs of emotional distress) and to engage in collective action to promote mental health (eg, identifying collective problems, establishing partnerships).36 The codesigned tool, titled Cadê o Kauê? (Where is Kauê?), was produced and disseminated via a social media campaign during the project. Cadê o Kauê? lasts approximately 90 min, during which time users are led to make choices that support the development of skills for peer support or collective action.37 We also developed a guide for teachers, to enable them to facilitate use of the chat-story in schools and promote relevant discussions regarding mental health.38 Both the digital intervention and the teachers’ guide were based on an understanding of mental health as a result of social determinants39 and of youth participation as a protective factor for adolescent well-being.40

Pluralistic coproduction in an extended network (how was it done?)

We adopted a horizontal way of working, following principles of inclusion, reciprocity and mutual respect.10 We used a pluralistic model,33 where young people had a voice and played an active role, and they and the adults shared control. The young researchers and the adult researchers collaborated on the study design, literature review, data collection and interpretation, design of the digital tool (with Talk2U) and dissemination of research results. Contributions from the young researchers were largely based on lived experience expertise, and contributions from the adult researchers were mainly grounded on academic/scientific expertise. Both groups had equal ownership of the work, including coauthorship of all scientific articles and conference presentations arising from the project. Authorship order was discussed and jointly agreed on.

The audio-visual production for dissemination of findings was mainly the responsibility of the young researchers alongside one adult researcher. Participant onboarding, data analysis, paper writing, development of an educators’ guide, management of the advisory groups and organisation of events were mainly the responsibility of the adult researchers. The project management and governance, including contracts, ethics approvals, reports to funders, management of external partnerships, financial management and legal aspects, were largely the responsibility of two adult researchers (GP and SGM), representing the University of Oxford and UnB. All team members had access to the full documentation about the project (including budget) and jointly monitored its progress and timeline. All team members contributed to planning, designing and executing activities; the main outputs and budget expenditures followed the plan outlined in the original proposal, as approved by the British Academy.

The work was conducted predominantly online, owing to the pandemic and the physical distance between our respective places of residence (across Brasília, Rio de Janeiro and Oxford). The adult and young researchers held approximately 40 joint online meetings via Zoom. Most of the meetings were held weekly, for reflection and decision-making and lasted 3 hours 40 min excluding breaks. In addition to these meetings, different groups met to carry out the tasks assigned in the weekly meetings or for further discussion; sometimes there was a mix of adult and young members and sometimes the adults and young researchers met separately. Of the total number of meetings recorded, around 60% had both young and adult researchers present. In addition to the remote meetings, approximately once every 3 months, we had in-person meetings in Brasília. Throughout the project, the team also kept an active WhatsApp group for communication between meetings. Meetings with collaborators and partners were held almost exclusively via Zoom, except for the dissemination workshops that closed the project in Brasília. Formal commitment to the project varied from 10 hours a week to full time. However, all team members managed their time flexibly according to project needs and other competing responsibilities. Both the young researchers and the adult researchers were remunerated monthly, according to the guidelines of their respective universities.

Observational method and recordings

Autoethnographic observation and analysis by the core coproduction team took place during the full project cycle (14 months). All the team members consented to taking part in the autoethnography and coauthored this piece (all were over 18 years of age at project entry, so parental consent was not required). The collective autoethnographic process included project and personal records (eg, notes, meeting minutes, WhatsApp group chat history) as well as dedicated meetings to reflect on the coproduction process, often held in relaxed environments and using arts-based methods. Challenges and solutions that arose during the coproduction process were recorded and systematised throughout the project, through analysis of emerging material and group discussions led by an adult researcher (FRS) in collaboration with two young researchers (JAdAM and VHdLS). The team discussed and agreed on the main challenges and solutions during joint meetings, with refinement of key themes conducted by SGM and GP. RRAdS oversaw the final readings and refinement as a young researcher member. Given the personal nature of the research and the impossibility of full anonymity, careful discussions were held about the authors’ thoughts and feelings about the inclusion of different practical examples and quotations; all authors reviewed and approved the final content selected for inclusion.

Results

The core coproduction team was formed in September 2021. From there onwards, we participated as peers in an extended network of professionals and partner institutions. Even though the project was originally designed to last 21 months, contextual barriers inherent to the establishment of the international partnership shortened this timeline to 14 months, resulting in substantial time pressure for the team. There was a constant need to coordinate work and adjust expectations in the face of time constraints.

The project was carried out in six stages, through which the coproduction team functioned in different ways and combinations. Table 1 summarises the challenges experienced and the corresponding solutions collaboratively agreed on by the team, across each of the project phases. Two videos led by the young researchers, sharing reflections on the co-production process, are provided in online supplemental videos 1 and 2 to illustrate some of our results. The conception of the project and the proposal submission, which preceded Stage 1, took place prior to full team recruitment, and were, therefore, not coproduced. However, youth voices were represented there via informal consultations with members of youth advisory groups worldwide. Below we detail each stage and illustrate it with anonymised quotes extracted from meeting notes and recordings across the project. Quotations are labelled according to respective identity groups (‘young researcher’ or ‘adult researcher’).

Table 1.

Coproduction challenges and solutions developed at each stage of the project

| Project stage | Coproduction challenge | Care/solution |

| 1—A level playing field | Managing and capitalising on the variability of knowledge, experiences and abilities of the team to conduct a qualitative mapping that is theoretically and methodologically sound, and culturally appropriate. Adult researchers don’t know the specific language and codes that are common to young people and their creative process. |

Education and training strategy for youth leadership in focus groups Investment in interpersonal knowledge of team members. The focus group/interview guide is coproduced by youth and adult researchers; youth researchers lead creation of a vignette in video format, with a character that would captivate the attention of the interviewees. Focus groups/interviews are co-delivered by pairs composed of youth and adult researchers. |

| 2—Our differences, our learning community | The entry of a new group of media professionals, influencing the coproduction dynamics, brought new learning challenges and more relational differences to assimilate. | Innovation Lab promotes knowledge exchange: media professionals involved in the project present the chat-story programming model; researchers present results of the mapping and concept definitions; young researchers translate concepts into artistic and cultural references relevant to Brazilian young people. |

| 3—A secure base from which to connect | ‘Not everything is young people’s responsibility’ appears in the results of our mapping study, but the project does not include the voice of adult stakeholders who might support adolescent participation in the setting where the chat-story will be implemented (ie, schools). The incorporation of multiple advisory groups adds complexity to the practice of coproduction. |

Policy advisors on education and adolescent health suggest creating an advisory committee with teachers and education professionals to anticipate challenges and facilitate the implementation of the intervention in the school context. The School Community Committee and Chat-Story Advisory Committee are formed, managed by adult researchers. Periodic meetings are jointly facilitated by young researchers and adult researchers for specific inputs. Cohesion within the core team provides a secure base to expand and manage increasing complexity, as difficulties are talked through and managed together. |

| 4—Care, transparency and accountability | Balancing expectations of all agents involved in the chat-story writing process, including the creative collaborators and needs identified during the mapping stage. The creative professionals express overload from numerous revisions of the chat-story script. Young researchers note limits to the listening sensitivity of peers and partners, work overload, as well as the need to develop greater ‘internal transparency’ of our shared work processes. Adult researchers invite young researchers to express problems and difficulties they perceive in coproduction and decision-making, as well as pointing to the lack of punctuality, presence, responsiveness in WhatsApp communication, and the fact that cameras are often turned off during meetings. |

This problem did not have a satisfactory solution for everyone. More than 10 versions of the chat-story were created, with collective revisions and recurrent negotiations regarding characters and structure of the story. The story needed to be revised in the test phase. Meetings to renegotiate deadlines and division of work, and to resolve differences in creative perspectives and schedules. Strengthened coproduction structure We tested a routine of sharing the achievements and non-achievements via WhatsApp, with emojis of clinking glasses and pineapples. We also tested group activities—remote or face-to-face—to build common understandings of co-production and our process, using online padlets and cardboard papers, and including leisure activities at waterfalls and in parks in Brasilía. Caring for each other Relaxed meetings enabled frank expression on the part of adult and young researchers, not always focusing on problems arising from the project. Young researchers mention undergrad and mental health pressures, beyond privately reporting more delicate cases that became barriers to active participation. |

| 5—The team as a living organism | Tiredness in the collective construction of the chat-story generates the perception that it is better to invest less in everyone’s synergy in all tasks due to the lack of time. Adult researchers had more time available for the project (eg, one of the adult researchers was full-time employed) than young researchers, as well as more skills for production and dissemination of the generated knowledge via research papers. Young researchers had overall higher video-making skills. The groups had little time to train each other in those skills. |

Work partitioning: young and adult researchers took turns in leading scientific dissemination and academic conferences. Some decisions were made by representatives of each group rather than full team. The audio-visual production for conferences became a mixed task: some of the recording, scriptwriting and video editing was executed by young researchers; some was executed by an adult researcher and an external company. Instagram content creation, however, was almost exclusive to young researchers. Young and adult researchers were distributed across different research papers, with adult researchers leading the process and sharing tasks. There was also a reorganisation of schedules with extension of deadlines, to make better use of the co-production format. |

| 6—Friendship for knowledge and care | The radical participation in each other’s lives was clear, with team members disclosing personal vulnerabilities at a level that is not commonly seen in research environments, at least from our previous experience. | The openness to surprises, to the unforeseen, and the attention to suffering not necessarily derived from the research, contributed to the emergence of friendship in the group, who took ten hours to say goodbye at the end of the project. |

bmjgh-2023-012443supp002.mp4 (134.1MB, mp4)

bmjgh-2023-012443supp003.mp4 (24.9MB, mp4)

Stage 1: a level playing field

The first stage launched the co-production process between adult and young researchers. Our first goal was to conduct a qualitative mapping of Brazilian young people’s perceptions of barriers to and enablers of good mental health as well as strategies they used to enact peer support and promote mental well-being.41 The results were used to guide the design of the digital tool Cadê o Kauê?.

Taking collective form

The process of working together made differences in levels of knowledge and experience more salient (table 1), such as the technical knowledge to conduct focus group discussions or interviews, more present among adult researchers, and the lack of knowledge on the part of the adults of the specific language and communication codes of young people in their creative processes. Added to that was a lack of familiarity with one another, and with the coproduction model, on the part of most group members. This meant that our initial meetings often resembled traditional adult-led environments, with adult researchers more likely to speak, set direction and have cameras turned on. Both adult and young researchers expressed feelings of ‘otherness’, emphasising ways in which the two groups differed, as illustrated by the following quotations from initial meetings:

I feel distant from the reality of what it’s like to be an adolescent today (adult researcher).

I am a bit scared of talking to the researchers (young researcher).

I don’t have a graduate degree, and I have barely started my undergrad studies (young researcher).

In order to deal with these challenges, we adopted two lines of action: one technical and one interpersonal. To address inequalities of knowledge, one of our adult researchers, a specialist in qualitative research, led a training session with the young researchers to help them develop skills for conducting focus groups and thematic data analysis. Although the young researchers did not offer reciprocal formal training to the adult researchers, they supported the latter in tasks they had less experience with, such as the dissemination of recruitment information via Instagram.

As for the interpersonal element, we invested time in discussing coproduction, teamwork and the values we wished to enshrine within the project. This was achieved, for instance, through workshops to discuss shared values and teamwork skills. We also focused on sharing knowledge about ourselves as people, so that generational differences were not perceived as barriers but as resources. This process made our similarities as human beings more salient, supporting the creation of a single team identity. This type of interpersonal knowledge is not to be confused with technical skills or what it is necessary to know for efficient production. Rather, these efforts were aimed at creating a resilient team, which bounces back from setbacks and permits its members to express their emotional needs.

At the beginning we did not work together. What do the [adult] researchers do? Then I understood. …This sensitivity of noticing what is happening to the other was expanding. We had many disagreements; the project affects everyone: Researcher 1, Youth 1, Researcher 2 … and then we met [in person]. Boy, we are human! They are the same height as me. And the goal is to make it work (young researcher).

One of the first creative exercises we did to get to know each other was to tell the story of our hair. Each adult or young person told their story from the point of view of their hair. Vulnerabilities were felt and challenges were faced by long, short, straight, curly, braided or black power hair. We heard stories of ancestry, power and madness, of love and hatred; we learnt that some of our team’s hair had been the victim of prejudice, while that of others not so much. The diversity of our hair and its life trajectories symbolised the diversity present within our coproduction collective.

Through this interpersonal process, we noticed the two groups getting closer and more committed, sharing and recognising the value in our different voices; and young researchers building their own ‘visibility’ in meetings, metaphorically and literally, and in creative ways that were not expected or planned by the adult researchers. For instance, young researchers took the initiative of producing a recruitment video as well as a visual vignette that was incorporated as a discussion starter for the interviews and focus group discussions.

Together we cocreated a topic guide and implemented youth-led interviews and focus group discussions, with adult researchers taking a supportive role. Cocreation during the mapping phase ensured that the concepts covered were relevant from a theoretical viewpoint and also spoke to the lived experience of adolescents, and that interviews and focus group discussions were comfortable, engaging and accessible to young participants.

Challenging assumptions

As we worked together, young researchers and adult researchers gradually built a new identity for themselves in the coproduction team, but not without back-and-forth movements of self-discovery in the team as a whole (eg, from student to collaborator, from PhD expert to lived experience expert, from the ‘work group’ to the coproduction team). We became more aware of ‘presumed responsibilities’ within the group, such as ‘leading an online meeting’ (adult) or ‘managing social media’ (young person), which helped us to address this. Efforts were made to redistribute responsibilities across team members, sometimes following direct requests from team members (eg, young researchers asking to attend administrative meetings previously attended exclusively by adult researchers or to receive support with particular tasks). In some cases, tasks were managed exclusively by the young researchers, who then called for more involvement by the adults.

The problem is the assumption that [adult] researchers make that we know how to easily produce a video. I really like to work on the project’s Instagram, but it is not easy (young researcher at remote team meeting)

A new working routine emerged, with young researchers and adult researchers taking it in turns to lead the weekly meetings. Moments of reflection were incorporated at the end of each meeting (even if briefly, via comments/emojis shared in the Zoom chat), to allow team members to express their feelings about the meeting or the coproduction process. Both groups felt increasingly comfortable making requests of each other, such as asking others to take on responsibility for timekeeping or maintain transparency with regard to tasks and budgets. Being able to make and respond to such requests made the group a more open and authentic space, where difficulties were aired in a frank yet respectful manner.

Stage 2: our differences, our learning community

In the second stage, we instituted the Digital Innovation Lab, which aimed to outline, in an intensive week of work, the core elements of our chat-story intervention and the structure of the narrative, on the basis of the findings from the mapping. In this phase, the core coproduction team was joined by the technology company Talk2U, which included professionals in the fields of cinema, communications and technology. We worked more directly with three creative professionals specialising in storytelling and scriptwriting. Our main aim was to create a compelling chat-story that incorporated the most relevant lessons from the mapping and supported young people’s participation in the promotion of good mental health.

As described in table 1, the solution we found to the challenge of combining multiple sources of expertise was openness to mutual learning. The creative professionals were willing to explore the research data and theoretical framing that we presented as foundational bases for the intervention; the adult and young researchers were willing to learn more about cinematic narrative resources, such as the ‘hero’s journey’. Both the creative professionals and the adult researchers were open to learning youth culture and were introduced to a range of memes, slang expressions and common situations or phrases relevant to young people’s mental health.

Stage 3: a secure base from which to connect

We integrated into our network several advisory stakeholder groups to support the chat-story in a consultative capacity. Two policy consultants provided recommendations on how to align the chat-story with public policies in education and adolescent health. Our policy consultants recommended bringing the voices of education professionals into the project, a suggestion which was accepted by the research team and subsequently resulted in the creation of a School Community Committee (SCC) to support the introduction of the chat-story into school settings. The SCC comprised teachers, school psychologists, educationalists and educational advisers, totalling 10 education professionals in Distrito Federal (the federative unit containing Brasília). These professionals helped to anticipate the challenges of using the chat-story in the school environment and to increase its chances of success. Finally, in order to maximise the cultural relevance of the chat-story at a national level, a Youth Chat-story Advisory Committee was formed. This group was composed of 24 high-school adolescents from all over the country, who provided input into the content and language of the chat-story. Adult researchers and young researchers jointly hosted remote meetings with each of these groups by videoconference, in addition to conversations via WhatsApp for specific input, such as the name of the chat-story.29

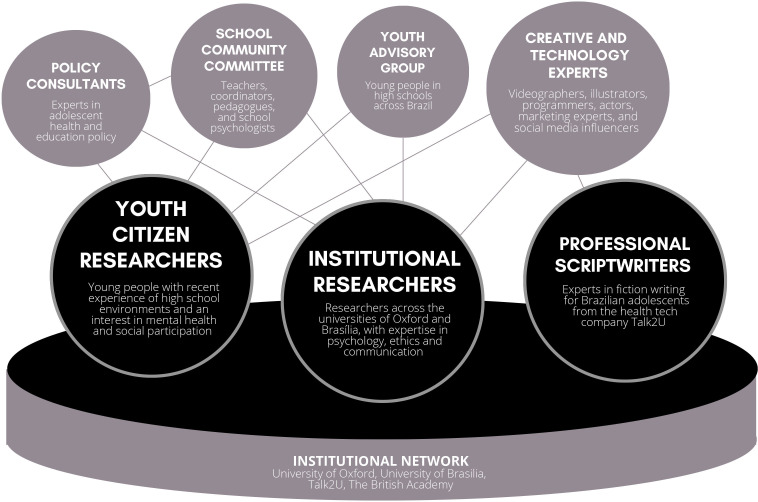

Figure 1 depicts the pluralistic model employed in the Engajadamente project, which brings together individuals and institutions on both a national and an international level. The coproduction process was evidently made more complex by involving a variety of external partners, with different technical specialisms and life experiences, and occupying different spaces, both geographically and in terms of their role in the public sphere: education professionals, public policy experts, artists, technology experts and students. To tackle overload and increase efficiency, we decided that responsibility for managing external groups would be divided among the adult researchers, with at least one young researcher attending meetings. Contributions were documented and actions agreed on at core team meetings.

Figure 1.

Expanded network of co-production.

The input received from different advisory groups was substantial and sometimes conflicting, and it occasionally necessitated unexpected work. ‘Errância’ (‘wandering’) was a word used repeatedly by the team throughout the project to describe the process, reinforcing its positive aspect: the ability to keep on moving, even when the path taken was not completely in the plans or not planned at all.

Sometimes I feel that we are achieving something, and I am quite satisfied, especially after this has been built on the basis of conversation. … A continuous effort. It is no use getting frustrated and saying “I won't do it.” How to deal with frustration: work to deal with frustration (young researcher).

The cohesion and trust that existed within the core coproduction team were experienced as an asset, a secure base that supported engagement with a complex and multilayered system of partners and advisors. The core team’s aspiration to ‘stick together’ and engage in active and empathetic listening to solve problems was perceived as a protective factor.

I feel that I am always trying to take the perspective of everyone involved. It is a continuous exercise … you learn over time. The coordination process has been more complex than I imagined; it is difficult to align sometimes. And it is OK to have this complexity because this circle [adult and young researchers] is protected. We accept that there are difficulties along the way, and that we will work through them (adult researcher).

Collectivity [in the larger network] does not always have positive moments … The toughest and most tiring moments become lighter when we are together (young researcher)

Stage 4: care, transparency and accountability

In the fourth stage, coproduction of the chat-story took place. This consisted of the development of the chat-story’s narrative script and resources such as videos and cards. This was the longest stage in our research timeline and brought us the most frequent and complex challenges. Cowriting a 72-page script, aimed at fulfilling the dual role of an engaging story and an intervention, in a team of 12 (the core team, in constant collaboration with three creative experts from Talk2U) was no mean feat. Challenges related to ensuring the inclusion of all involved were added to other issues typical of complex work done with collaborators and advisors, with several expectations needing to be balanced. Emerging challenges included overload; the need to listen sensitively and incorporate everyone’s voices; the ambiguities of work segmentation and the inequality of resources, such as the time available to each member for the project. Two sets of solutions were sought.

Strengthened coproduction structure

The work process with new collaborators revealed the difficulty of integrating the groups, sometimes generating dissatisfaction (eg, when feedback failed to be incorporated). Among the solutions created were having many conversations about the importance of working together and valuing the expertise each stakeholder brings (eg, expertise in media, education or youth culture). Critically, we created accountability processes, whereby we would, for instance, systematically collate all feedback received, internally and externally, on a particular topic/scene. The document would later be updated with justifications regarding the incorporation or rejection of each piece of feedback into the script.

New roles emerged, somewhat spontaneously. One of the adult researchers took on the task of invigorating relationships between young and adult researchers, while two others invigorated relationships with collaborators, supporting mutual understanding as well as timely and fair resolution of eventual conflicts. We also encouraged core group members to reach out to anyone they trusted in the team to express any difficulties (eg, not feeling well enough to complete a task) to increase mutual support. Great effort was invested in developing assertive relationships.

At each difficulty, we did something to change. Whether it was sending a detailed email, talking things through at a meeting, or exchanging messages. We have been open and attentive all the time, and this has taken a great toll on our energy, for fear of the train derailing, or of us exceeding someone’s limits … (adult researcher)

Within the core team of adult and young researchers, solutions were developed to increase transparency and support collective organisation and efficiency. We began to list weekly work goals that were jointly achieved and those not achieved by the team, via WhatsApp, with emojis of clinking glasses (for the goals achieved) and pineapples (for the goals not achieved). We also started voting on decisions related to changes in the chat-story script where no clear consensus was reached, to ensure that everyone’s voices counted equally. We also decided that some of the meetings and small-scale decisions did not require all of us to attend, as long as both groups were represented (at least one young person and one adult researcher).

Some of the disagreements that emerged through the process were resolved through extensive discussion and negotiation. An example of such an instance was the joint decision-making around the profile and tone of the speech of one the most controversial characters in the story. The young researchers and adult researchers disagreed with the professional scriptwriters as to whether the character should be portrayed as an aggressive ‘bully’ or a likeable classmate. After several consecutive meetings and script revisions, the group reached the decision to portray the character as a funny troublemaker who lacks mental health literacy. A video/image portfolio of social media posts containing examples of similar behaviour was compiled to consolidate a common understanding of the character’s personality.

Caring for each other

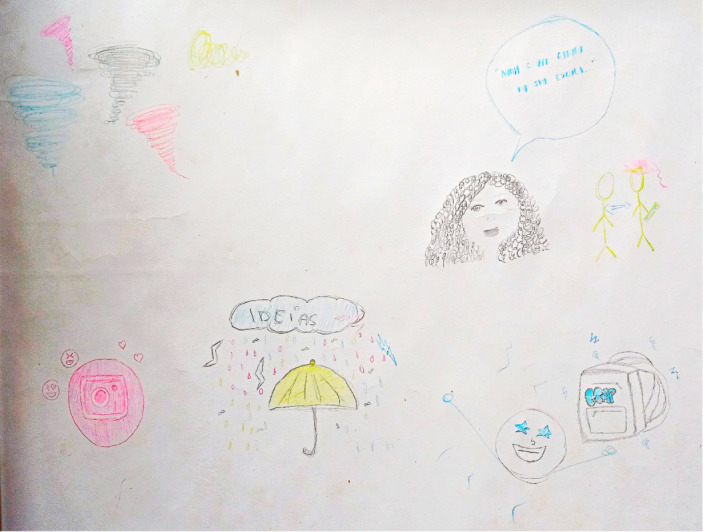

As a care strategy for the core team in the face of overload or disagreements, we mixed work evaluation with leisure activities together, near waterfalls and in parks in Brasília. We used remote and in-person activities to share our feelings about coproduction and our different understandings of the coproduction process, jointly designed and facilitated by two young researchers and an adult researcher. One such activity involved coconstructing an online board where members shared images or songs illustrating how they currently felt about the coproduction process. Another activity, facilitated in person in a green space suitable for relaxation, consisted of a collective drawing made by adult and young researchers that depicted barriers to or enablers of the chat-story coproduction. As shown in figure 2, coproduction was expressed through the drawing of swirls, showing that the process perceived as messy, and affective memories. The backpack in the drawing refers to a moment in which the creative collaborators and education professionals consulted disagreed about the inclusion of a scene in the chat-story script, in which the user is led to open a character’s backpack in search for clues. The coproduction was also portrayed as a two-way arrow pointing to a university graduate and someone without a degree, symbolising the partnership of young and adult researchers; an open umbrella represented the model’s rich potential for innovation and creativity.

Figure 2.

Collective coproduction drawing made by adult and young researchers.

The co-production process is a storm of ideas; we are always accepting and rejecting ideas and building something together. Our potential is endless. … We are always reaching new heights, like going up to infinity (young researcher)

The huge creative potential and everyone’s commitment to the project meant that the chat-story narrative was continually improved, with over 10 drafts generated. To remind ourselves to overcome collective perfectionism and keep our efforts at a manageable level, we often used a quotation from Isabel Allende, who said of her own writing process: ‘You never finish a novel—you just give up’.

The exercise of intertwining knowledge and care fostered emotional security. Group members became more likely to share details about their personal life (eg, by introducing the team to their romantic partners) and to introduce humour (eg, when the young researchers made generational jokes at the expense of the adult researchers). Enhanced emotional security increased the space for free and authentic sharing of difficulties, not always related to the project, and sometimes of a personal or delicate nature. For instance, a young researcher shared feelings of burnout and reduced accomplishment as a result of returning to campus after COVID restrictions were lifted, which involved a 4-hour daily commute (most young researchers lived in the outskirts of Brasília).

When someone does not turn on their camera, does not show up on time, says the whole weight is on them, this can be a cry for help and demands another level of attention and understanding. Yes, it is important to invest in discussing transparency and the role of each person, but also to care for our emotional needs and ascertain the support network (adult researcher)

The core team became more sensitive to changes in each other’s behaviour or eventual disengagements of team members from the coproduction process and potential associated emotional and contextual challenges. Our coproduction process took on new dimensions when peers started recognising each other as a support network. Greater proximity generated new responsibilities or a duty to care for each other’s health and well-being. This feeling was particularly salient among the young researchers in relation to each other, and among the adult researchers in relation to the youth group. Meetings between team members were held to discuss issues of a personal nature and signpost resources.

I keep thinking about the responsibility that, in the project, we researchers have towards you, the younger ones. … What is the limit to work the two dimensions: the feelings that need to be experienced and expressed and the care that should be offered to those who do that (adult researcher)

Stage 5: the team as a living organism

In the fifth stage, the main project goal was the dissemination of the chat-story and project findings. Dissemination of the digital intervention was led by Talk2U via a social media campaign, which integrated input from the core coproduction team, reaching over 6400 users; a digital influencer with a mental health difference also supported dissemination via Instagram,42 with a video totalling over 20k views.

Adult and young researchers aimed to disseminate the chat-story and research findings via academic conferences, scientific articles and YouTube videos, as well as workshops for teachers, researchers and policymakers. At this stage, our biggest challenge was handling the overload caused by the overlapping tasks, combined with national and international travelling. The solution found was to divide the work:

It is important to be aware of one’s own feelings and to think of rearrangements, to cover tasks, impossibilities, emotional and physical problems that will arise, not always as a result of the project, sometimes yes. One needs to take another person’s task and the team needs to function as a living organism (adult researcher, remote group meeting)

The coproduction model meant that all members felt a sense of responsibility and ownership over all outputs. Roles became relatively interchangeable at this point, as everyone felt confident to speak to any aspect of the project. Delivery of presentations was distributed across team members (young and adult), ensuring broad dissemination across the fields of psychology, health tech, youth mental health and public health as well as the education sector. Inequalities in certain areas emerged as a challenge, with technical knowledge and time for writing articles being greater among the adult researchers and filmmaking skills better among the young researchers. As for writing research articles, problems were alleviated by the allocation of pairs composed of an adult lead and a young researcher to lead on each article being prepared. For videos, a group of young researchers and an adult researcher took the lead on different outputs, with support from the team. Overload was handled by collective renegotiation of the schedule and responsibilities, according to personal and contextual limitations.

Our closing event, jointly chaired by an adult and a young researcher, included researchers, members of parliament, health ministry representatives and local policymakers, most of whom were being introduced to coproduction for the first time. Praise for the working model was effusive.

There was no way the chat-story could go wrong, because of the co-production model (Education Secretary of Distrito Federal, in-person closing event).

Stage 6: friendship for knowledge and care

At the end of the project, the perceived impacts of the coproduction process were shared over an evaluation lunch, which evolved into afternoon coffee then dinner, totalling almost 10 hours of relaxed and open conversation. Members of the core team expressed the symbolic and material value of inclusion in the academic field, both for young people and adults.

I am grateful for this international cooperation as it has always been very difficult to do research in Brazil with so few resources (adult researcher).

The project gave me the conditions to go ahead with my course: I left a complicated environment, I was able to rent my own place and have an income … This project saved me, and made my graduation possible (young researcher).

The radical participation in each other’s lives was clear, with team members disclosing personal vulnerabilities at a level that is not commonly seen in research environments, not at least from our previous experience.

At one point in my life, I thought I would not have been able to continue as a researcher, after suffering a very stigmatising mental health intervention. My doctor recommended that I apply to work with you … she thought I would be the right person for it and that this collaboration would be powerful (adult researcher).

I have always felt I did not belong at university, mainly because of my skin colour and all the sacrifices I had to make to experience university. Whenever we worked together this feeling disappeared (young researcher).

Because of my life trajectory, I needed to work effectively on my own, to get out of very precarious living conditions and expand my networks. It was very special to work among peers, not to be alone. This is my best paper yet (adult researcher).

I am going through a unique moment of grappling with our finitude, as I a care for someone nearing the end of life in my family environment. And that mixes cycles of my life (adult researcher).

Group members’ verbal contributions were interspersed with exchanges of glances between different people, sometimes tearfully, at a round table in a café in Brasília, where young and older researchers spontaneously held hands. The circle at the café closed the project, whose continuation now depends on forming a new network of institutional and financial support. But perhaps being moved by each other’s stories is part of the process of pluralistic coproduction, in times of vulnerability, as the research progresses along its trajectory. This cultural clue left us pondering about what defines and structures radical forms of coproduction, where friendship between heterogeneous groups may be an unplanned discovery, but a bond that is possible and perhaps necessary.

Discussion

We have presented an autoethnographic account of the challenges and solutions adopted in the process of coproduction of a chat-story intervention in Brazil, where adults and young people shared power and control, within a network of creative collaborators and allies across education, policy and communication. Differences or heterogeneity in our group, especially in terms of age and professional experience, created blind spots and made it challenging to build a common perception of the whole and the parts involved. The autoethnographic work allowed us to observe the following: (1) continuous investments to improve our collaboration that considered technical, social and personal needs, resulting in greater transparency and power sharing; (2) the emergence of internal trust and cohesiveness, which supported engagement with a complex network of partners; (3) the creation of formal and informal mechanisms for accountability and fair inclusion of multiple voices; (4) reorganisation of responsibilities and care practices to handle fatigue and overload and promote equitable participation and (5) joint care invested in reorganising our work process in each challenging situation, giving rise to synergy and intergroup friendship.

Our experience of coproduction contrasts with decades of literature that uses the metaphor of a ladder to characterise participation, especially that of children and young people. The model proposed by Arnstein43 includes eight steps that go from superficial citizen representation to effective citizen power. This model, as adapted by Hart,44 maintains the ladder metaphor: going from resistance or impediment to youth participation, through manipulation, decoration and ‘tokenism’—which includes consultation with adolescents but ‘with minimal opportunities for feedback’—to higher stages of participation, with young subjects who are accountable or are autonomous protagonists themselves.

An obvious contrast lies in the idea of a linear, or rather ascending, trajectory, from a lower degree of participation to a higher degree over time. In our project, some challenges could not be promptly met and some of the solutions gave rise to new challenges, for instance, when efforts to amplify participation generated overload or when interpersonal closeness gave rise to duties of care. Consistent with our experience, Chung and Lounsbury17(p.2137) described participation in a research project as ‘neither linear nor unidirectional; rather it zigzagged up and down as actors negotiated issues of power, process and relationships’. Yet, the authors mention the possibility of a continuum from lower to greater coproduction quality, which we were also able to observe, with progressive ethical adjustments to facilitate synergy and equalise decision-making power.

‘Messiness’, or non-linearity, is further amplified in complex social, political and economic scenarios, settings where awareness of coproduction is usually low, or where young people’s right to life and health is not guaranteed. In our case, instability was compounded by: (1) challenges derived from the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) the negationist approach to science prevalent in Brazilian society; (3) rampant economic insecurity and (4) an epidemic of poor mental health, among other factors. Time was a key resource affected, with time constraints generating tight deadlines and necessitating agility to execute a project that had been designed in another global reality. More empirical research into the practice of coproduction in LMICs, or vulnerable settings, is necessary to understand how larger political and social factors influence the process. This will help inform recommendations on how to strengthen capacity for coproduction in LMICs12 45

The costs of coproduction have been discussed by researchers in the field, including costs for the process and products of coproduction as well as the personal and professional costs for researchers and stakeholders.46 However, others have argued that these costs result from structural and organisational failures to accommodate and promote emancipatory research and its outputs, rather than being flaws inherent in this research method.11 In our experience and that of others,47 48 the main costs involved in generating a favourable context were related to time, material resources, symbolic context (eg, management of power relations) and relational context (eg, investment in trust-building, conflict management and shared decision-making).

In order to anticipate and minimise the personal wear and tear, expected in coproduction projects, a prior assessment of the resources available in the context or project is necessary. This analysis might help determine whether and how coproduction is feasible and capable of creating synergy, that is, ‘the power to combine the perspectives, resources, and skills of a group of people and organisations’.49(p.183) This is especially relevant for coproduction that makes use of a broad network of partnerships, with varying needs and priorities.

If the context is favourable, coproduction from ‘phase 0’, when priorities in the research agenda are defined and the research project conceived, can foster successful implementation.47 However, this is not always possible. In our project, recruitment of the complete research team was only possible after grant funding was secured and an international agreement was signed. The absence of co-production from ‘phase 0’ was partially circumvented by ensuring that all members had a comprehensive understanding of the project as a whole, including access to full documentation, and the ability to influence key research decisions beyond the core commitments made in the original proposal. These efforts gradually increased team members’ sense of ownership over the project. Once a project is set up, sustaining relationships of trust and organisational structures that maintain partnerships is fundamental to allowing future coproduction that begins from agenda setting.50 51

Lessons learned

In our experience, three key factors were important for the success of our coproduction process. First, we continually sought solutions and adjusted our process to meet challenges encountered along the way, for instance, by reassigning responsibilities and revising timelines. Such flexibility, previously described as a critical ingredient to coproduction success,18 52 helped achieve inclusive and equitable participation within a team that was heterogeneous in availability, knowledge and resources. This practice required recognising the difference between ‘taking responsibility for’ and ‘taking away control from’ the other, the latter being a very common form of paternalism usually found in the relationship between adults and children.53 Christensen and Prout54 suggest working from the concept of ‘ethical symmetry’ in coproduction with young people, acknowledging that every right accorded to adults in research has a counterpart for young people. This recognition of symmetry does not mean ignoring individual needs and demands. It means, rather, remaining sensitive and flexibly adjusting to such needs.

Second, we sustained collective trust in the model—a shared understanding of coproduction as capable of surviving mistakes, unplanned successes and errors. Challenges were managed through a shared commitment not only to the stages of production but also to preserving bonds among the researchers and with external partners. All team members made efforts to cultivate a positive relational context, by regulating emotions, valuing different perspectives, validating each other’s negative feelings and seeking to reach solutions that would suit the group’s needs and priorities.

Third, such commitments were operationalised through active organisational adjustments and care movements, coconstructed and agreed between the heterogeneous poles. These movements were initially led by adult researchers, and later cocreated by the two groups. Strategies included: mutual capacity-building (eg, technical training); investment in building interpersonal knowledge and cohesion (eg, through joint leisure activities); dedicated time for reflection on the coproduction process (eg, via creative methods); transparency structures (eg, weekly sharing of achievements and non-achievements by both groups); accountability processes (eg, detailed documentation of stakeholders’ feedback and actions taken); adoption of multiple methods to ensure inclusion of all voices (eg, voting); mutual support (eg, signposting to support services) and strategies to reduce overload (eg, contribution by representation).

By coinventing care, we deconstruct participation metaphors that represent the process of coproduction as a single axis—young people—who linearly and progressively accumulate participative experience up to the point of full autonomy. Rather, we aim to favour an understanding of the social, caring and productive bond that allows innovative outcomes, only possible because of the intersection of differences.

Methodological considerations

The collaborative autoethnographic method used proved to be a powerful methodology, affording our group enhanced control over the research process, without an ‘intermediary’ researcher representing our voices.55 The method allowed for a shared narrative of our coproduction experience. Consensus through collective discussion validated our observations; however, as with other participatory research models, it did not ‘negate differences in perception and experience’”.56(p43). It is likely that the autoethnographic process itself influenced the results, given that the opportunity for collective reflection strengthened our mutual understanding and cohesion, as observed in previous case studies.57 The stories revealed were deeply personal and vivid, but they also went through collective maturation, balancing what the group considered relevant and safe to share. It is possible, therefore, that different conclusions would have been reached, or insights gained, by an ‘external’ researcher conducting participant observation or anonymous, individual interviews with group members. Rather than providing replicable, generalisable results, the goal of our analysis is to offer a practical case study that stimulates reflection and conceptual insight.

Conclusion

Our autoethnographic experiment was applied to a pluralistic coproduction project involving young people and adults working together closely to build a digital intervention for mental health in Brazil. That is a combination that is not naturally homogeneous: on one side were researchers linked to traditional research institutions; on the other, young citizens who experience youth environments first hand. The challenges we experienced collectively reveal a non-linear path of coproduction, with progressive ethical adjustments for inclusion, equity and transparency. The autoethnographic method, supported by creative methods that enabled conversations about feelings and difficulties, resulted in a story of coproduced care. The cross-generational friendship, built alongside the willingness to speak frankly and freely, opens new possibilities for radical approaches in coproduction research involving young people. Perhaps these would entail coproduction that does not conform to ‘ladder’ models, that is suitable for vulnerable contexts, and that intertwines knowledge and mutual care, drawing on the authenticity of each group member and that shows a deep respect and understanding of the culture of the society concerned.

Acknowledgments

We thank the health-tech company Talk2U for their partnership in this project. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the young people, education professionals, artists and policy experts who formed our extended co-production network. This project was funded by a British Academy Youth Futures Programme Grant, supported under the UK Government’s Global Challenges Research Fund, awarded to GP, SGM and IS (Grant number YF/190240) and an NDPH Intermediate Fellowship to GP. For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied for a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @gabi_pavarini

Contributors: The autoethnography was designed by FRS with input from the full team, especially JAdAM and VHdLS and the senior authors (SGM and GP). All authors contributed to data acquisition and interpretation. Data analysis and structured reflections were led by FRS in collaboration with JAdAM and VHdLS. The team discussed and agreed upon the main challenges and solutions during joint meetings, with refinement of key themes conducted by SGM and GP. FRS wrote the first draft, with contributions from JAdAM, VHdLL and SGM, and all authors contributed to editing. FRS, SGM, GP and RRAdS led revisions to the manuscript addressing reviewers’ comments. The study integrates a larger research project (www.engajadamente.org) led by GP and SGM. GP is the guarantor of this work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support this study are available from the corresponding author, GP, upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The project received ethics approval from the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 501-21, Ref. 550-21), the University of Brasilia Humanities and Social Sciences Ethics Committee (Ref. 4.688.652, Ref. 5.196.133) and the Brazilian National Ethics Commission (Ref. 4.932.068, Ref. 5.510.769). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Haklay M, Dörler D, Heigl F, et al. What is citizen science? the challenges of Fefinition. In: Vohland K, Land-zandstra A, Ceccaroni L, eds. The Science of Citizen Science. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2021: 13–33. 10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redman S, Greenhalgh T, Adedokun L, et al. Co-production of knowledge: the future. BMJ 2021;372:n434. 10.1136/bmj.n434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle D, Harris M. The Challenge of Co-production: How Equal Partnerships Between Professionals and the Public are Crucial to Improving Public Services. London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulter A, Ellins J. Patient-Focused Interventions: A Review of the Evidence. London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin S, Fleming J, Cullum S, et al. Exploring attitudes and preferences for dementia screening in Britain: contributions from Carers and the general public. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:110. 10.1186/s12877-015-0100-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friesen P, Lignou S, Sheehan M, et al. Measuring the impact of Participatory research in psychiatry: how the search for Epistemic justifications obscures ethical considerations. Health Expectations 2021;24:54–61. 10.1111/hex.12988 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13697625/24/S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose D. Patient and public involvement in health research: ethical imperative and/or radical challenge J Health Psychol 2014;19:149–58. 10.1177/1359105313500249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton P. Conceptual, theoretical and practical issues in measuring the benefits of public participation. Evaluation 2009;15:263–84. 10.1177/1356389009105881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pizzo E, Doyle C, Matthews R, et al. Patient and public involvement: how much do we spend and what are the benefits Health Expectations 2015;18:1918–26. 10.1111/hex.12204 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13697625/18/6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickey G, Brearley S, Coldham T, et al. Guidance on co-producing a research project. Southampton, United Kingdom: INVOLVE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams O, Sarre S, Papoulias SC, et al. Lost in the shadows: reflections on the dark side of Co-production. Health Res Policy Sys 2020;18:43. 10.1186/s12961-020-00558-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agyepong IA, Godt S, Sombie I, et al. Strengthening capacities and resource allocation for Co-production of health research in low and middle income countries. BMJ 2021;372:n166. 10.1136/bmj.n166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed H, Couturiaux D, Davis M, et al. Co-production as an emerging methodology for developing school-based health interventions with students aged 11–16: systematic review of intervention types, theories and processes and thematic synthesis of Stakeholders’ experiences. Prev Sci 2021;22:475–91. 10.1007/s11121-020-01182-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norton MJ. Co-production within child and adolescent mental health: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:11897. 10.3390/ijerph182211897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bevan Jones R, Stallard P, Agha SS, et al. Practitioner review: Co‐Design of Digital mental health Technologies with children and young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2020;61:928–40. 10.1111/jcpp.13258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turnhout E, Metze T, Wyborn C, et al. The politics of Co-production: participation, power, and transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2020;42:15–21. 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung K, Lounsbury DW. The role of power, process, and relationships in Participatory research for statewide HIV/AIDS programming. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:2129–40. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincent K, Steynor A, McClure A, et al. Co-production: learning from contexts. In: Climate Risk in Africa. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021: 37–56. 10.1007/978-3-030-61160-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewa LH, Lawrence‐Jones A, Crandell C, et al. Reflections, impact and recommendations of a Co‐Produced qualitative study with young people who have experience of mental health difficulties. Health Expectations 2021;24:134–46. 10.1111/hex.13088 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13697625/24/S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dos-Reis MCA, Isidro-Filho A. Inovação em Serviços E a Coprodução no Setor Público Federal Brasileiro. Adm Púb e Gest Social 2019;12:1–15. 10.21118/apgs.v12i1.5481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Age LM, Schommer PC. Coprodução de Serviço de Vigilância Sanitária: Certificação E Classificação de Restaurantes. Rev Adm Contemp 2017;21:413–34. 10.1590/1982-7849rac2017170026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein Jr VH, Salm JF, Heidemann FG, et al. Participação E Coprodução em Política Habitacional: Estudo de um Programa de Construção de Moradias em SC. Rev Adm Pública 2012;46:25–48. 10.1590/S0034-76122012000100003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Relatorio Luz da Agenda de Desenvolvimento Sustentavel . Grupo de Trabalho DA Sociedade civil para a agenda 2030. 2022. Available: https://gtagenda2030.org.br/relatorio-luz/relatorio-luz-2022/

- 24.Neri MC. Juventudes, Educaçao e Trabalho: Impactos da Pandemia nos Nem-Nem. Sao Paulo, 2021. Available: https://dssbr.ensp.fiocruz.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/TEXTO-Pandemia-Jovens-Nem-Nem_Sumario-Marcelo_Neri_FGV_Social.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Silva IM, Lordello SR, Schmidt B, et al. Brazilian families facing the COVID-19 outbreak. J Comparative Family Studies 2020;51:324–36. 10.3138/jcfs.51.3-4.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barros MB de A, Lima MG, Malta DC, et al. Mental health of Brazilian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res Commun 2022;2:100015. 10.1016/j.psycom.2021.100015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UOL . Pânico no Colégio. 2022. Available: https://tab.uol.com.br/noticias/redacao/2022/04/17/panico-no-colegio-crise-de-ansiedade-leva-26-alunos-do-recife-a-ps.htm

- 28.Butz D, Besio K. Autoethnography. Geography Compass 2009;3:1660–74. 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00279.x Available: https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/17498198/3/5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayano D. Auto-Ethnography: paradigms, problems, and prospects. Human Organization 1979;38:99–104. 10.17730/humo.38.1.u761n5601t4g318v [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liggins J, Kearns RA, Adams PJ. “Using Autoethnography to reclaim the 'place of healing' in mental health care”. Soc Sci Med 2013;91:105–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Byrne P. The advantages and disadvantages of mixing methods: an analysis of combining traditional and Autoethnographic approaches. Qual Health Res 2007;17:1381–91. 10.1177/1049732307308304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang H, Ngunjiri F, Hernandez KAC. Collaborative Autoethnography. In: Collaborative autoethnography. Routledge, 2016. 10.4324/9781315432137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das S, Daxenberger L, Dieudonne L, et al. An inquiry into involving young people in health research - Executive summary. London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Projeto Engajadamente. 2023. Available: www.engajadamente.org

- 35.Talk2U . Chat and ignite: change. 2022. Available: https://talk2u.co

- 36.Pavarini G, Murta SG, Mendes JAA, et al. Cadê O Kauê? Co-design of a chat-story to enhance youth participation in mental health promotion in Brazil. 2023.

- 37.Pavarini G, Murta SG, Mendes J, et al. Your best friend is missing and only you can find him. IDC ’23; Chicago IL USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM, June 19, 2023:732–5 10.1145/3585088.3594496 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engajadamente P. Cade o Kauê? Uma experiência para inpsirar ações transformadoras em saúde mental: Guia para aplicação na escola. Brasilia, DF, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012;379:1641–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ballard PJ, Syme SL. Engaging youth in communities: a framework for promoting adolescent and community health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:202–6. 10.1136/jech-2015-206110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendes JAA, Murta SG, Siston FR. Young people’s sense of agency and responsibility towards mental health in Brazil: A Reflexive thematic analysis. In Review [Preprint]. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2952376/v1 [DOI]

- 42.Miranda JPGA. Mande Uma MSG para @Cade_O_Kaue E Jogue no Próprio Instagram! 2023. Available: https://www.instagram.com/reel/CnpemdUhc_R/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

- 43.Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Institute Plan 1969;35:216–24. 10.1080/01944366908977225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hart RA. Children’s participation: from Tokenism to citizenship. 1992. doi:88-85401-05-8

- 45.Beran D, Pesantes MA, Berghusen MC, et al. Rethinking research processes to strengthen Co-production in low and middle income countries. BMJ 2021;372:m4785. 10.1136/bmj.m4785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliver K, Kothari A, Mays N. The dark side of Coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research Health Res Policy Sys 2019;17:33. 10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burgess RA, Choudary N. Time is on our side: Operationalising ‘phase zero’ in Coproduction of mental health services for Marginalised and Underserved populations in London. Int J Public Administ 2021;44:753–66. 10.1080/01900692.2021.1913748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]