Abstract

Introduction

To evaluate awareness and knowledge of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a common and potentially life-threatening complication in people living with type 1 diabetes (T1D).

Research design and methods

A survey was developed to assess individuals’ current knowledge, management, and unmet needs regarding DKA. The study was conducted in six Swiss and three German endocrine outpatient clinics specialized in the treatment of diabetes.

Results

A total of 333 participants completed the questionnaire (45.7% female, mean age of 47 years, average duration of T1D at 22 years). Surprisingly, 32% of individuals were not familiar with the term ‘diabetic ketoacidosis’. Participants rated their own knowledge of DKA significantly lower than their physicians (p<0.0001). 46% of participants were unable to name a symptom of DKA, and 45% were unaware of its potential causes. 64% of participants did not test for ketones at all. A significant majority (67%) of individuals expressed the need for more information about DKA.

Conclusions

In patients treated in specialized centers, knowledge of DKA was found to be inadequate, with a lack of understanding regarding symptoms and causes. Healthcare professionals tended to overestimate individuals’ knowledge. Future efforts should focus on addressing these knowledge gaps and incorporating protective factors into the treatment of T1D.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, type 1; diabetic ketoacidosis; patient-centered care; knowledge

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a potentially life-threatening complication in people living with type 1 diabetes, but little is known about patients’ awareness and knowledge of DKA.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Many individuals were unfamiliar with the term ‘diabetic ketoacidosis’ and almost half of participants could not name a single symptom or potential cause of DKA.

Healthcare professionals overestimate patients’ knowledge of DKA.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Critical evaluation by healthcare professionals of patients’ knowledge is needed and effective ways to help individuals better understand the causes, symptoms and treatment of DKA are required

Introduction

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a potentially life-threatening, acute complication in people living with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D)1 and the leading cause of death among people under 58 years with T1D.2 Known risk factors for DKA include poor adherence to diabetes management,3 technical failures in insulin pump users, socioeconomic disadvantage based on education level, income and insurance status, younger age (13–25 years), female gender, high HbA1c, and psychiatric comorbidities (eg, eating disorders and depression).4–7 Because sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors also increase the risk of DKA, their use in people living with T1D is not authorized by the European Medicines Agency anymore.8 Recent data indicate that event rates for DKA have been increasing significantly over the past years, especially during COVID-19 pandemic.9–11 Early diagnosis is essential to prevent further deterioration, particularly in elderly individuals and those with severe underlying diseases.12 In addition to early diagnosis, adequate patient education is required to notice signs of DKA in order to initiate diagnostic and/or therapeutic measures in time. Especially individuals who already had a previous episode of DKA are at increased risk of having another episode.2 Recent data during the COVID-19 pandemic have also shown that the risk of hospital readmission with DKA, within 1 year of a DKA episode requiring intensive care, is approximately 29% and is associated with high risk of long-term mortality and high hospital costs,13 highlighting the need for further research on the distinct causes and suggesting a knowledge gap regarding DKA. However, data on patient knowledge of DKA are scarce14 15 and may not accurately reflect the full picture, as they do not fully capture both the individual’s actual knowledge and the perceived knowledge of the treating healthcare professionals. The aim of our study was to investigate individuals’ attitudes, awareness and knowledge of DKA in a multicenter, international approach involving the treating physicians.

Materials and methods

Study design

Data were collected between 1 January 2021 and 30 June 2021 at six sites in Switzerland (Metabolic Center Cantonal Hospital Olten, Metabolic Center St Gallen, University Hospital Basel, Gesundheitszentrum Fricktal Rheinfelden, MedCenter Volta Basel and Cantonal Hospital Basel-Land Site Bruderholz) and three sites in Germany (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Diabetes Centre DZHW Hamburg, Diabetespraxis Buxtehude), in clinics that exclusively treat adolescents from the age of 16 and adult patients. All participating centers are well-known centers for treatment of T1D in their region and are dealing regularly with the disease. Further, all centers have diabetes nurses available and provide classes for knowledge transfer of T1D. Participation was limited to people with an established diagnosis of T1D according to current standards, was completely voluntary and anonymous and took about 10–15 min.

Survey questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was developed at the Metabolic Center Olten, Switzerland, and covered basic questions about DKA, the patient’s demographic and medical history. The questionnaire was discussed and further developed together with a registered diabetes nurse with more than 10 years of experience and two people living with T1D. The final questionnaire was given to the study participants in paper form following their outpatient consultation by their healthcare professionals and after informing them about the scope of the survey and its entirely independent and voluntary nature of participation. Participants were allowed to return the questionnaires by mail or in a separate box in the respective study centers allowing their anonymity. Baseline parameters (age, sex, education, duration of diabetes, HbA1c), content on personal experience and theoretical knowledge of DKA were collected. To assess individuals’ knowledge of DKA, they were first given free-text answers about possible causes and typical symptoms of DKA. They could then select from a range of symptoms, some of which were not typical of DKA. In addition, the attending physician gave a subjective assessment of the individual’s general knowledge of diabetes ranging from ‘1 - no knowledge’ to ‘10 - excellent knowledge’ with a numerical value without further comment. An English translation of the final questionnaire is available in online supplemental file 1. A brief summary video is available in online supplemental file 2.

bmjdrc-2023-003662supp001.pdf (72.3KB, pdf)

bmjdrc-2023-003662supp002.mp4 (2.8MB, mp4)

Furthermore, representatives of each study site were asked about the type of institution, the number of physicians employed in the respective department, the average number of patients in general, specifically people living with T1D seen per quarter on average, estimation of general knowledge about DKA, treatment of individuals with T1D with SGLT2 inhibitors and the existence of a specific DKA program.

Statistical analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland,16 17 and analyzed using GraphPad Prism V.9 for MacOS V.9.4.1. Continuous data are presented as arithmetic mean with 95% CI or median and IQR and were analyzed for normal distribution by comparing arithmetic mean, median, skewness and kurtosis as well as using D’Agostino and Pearson tests. For the level of significance, an alpha error of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used for two-group comparisons of non-parametric paired data, the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric unpaired data and Student’s t-test for parametric data. Spearman r was calculated for correlation analyses.

Missing data were not imputed and classified as missing at random.

Ethics and transparency

The study does not fall under the Swiss Human Research Act as only anonymized data were collected and the questionnaire was entirely voluntary. Participants were individually briefed by their physicians regarding the questionnaire’s purpose. Their participation in any portion of this survey was considered implicit consent for the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. A total of 333 individuals participated in the study. There were slightly more men (54%) than women (46%) among the 324 who declared their sex. A total of 69% (n=216) reported that they were married or in a partnership and 33% (n=105) were either single, divorced or widowed. The majority of individuals (n=264, 84%) reported living with a partner, family, friends or in a shared apartment, while only 17% (n=52) reported living alone. A total of 171 patients (69%) reported working part-time or full time and 21 patients (7%) were students or in training. Approximately 80% of individuals had received diabetes counseling within the past 6 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all 333 respondents

| Characteristic | Mean (SD; range) | n (%) | Missing values (%) |

| Age | 47.6 (16.6; 18–86) | 10 (3.0) | |

| Sex | 9 (2.7) | ||

| Female | 148 (45.7) | ||

| Male | 176 (54.3) | ||

| Body weight (kg) | 78 (17.6; 44–190) | 20 (6.0) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2 (4.7; 16.4–48.4) | 23 (6.9) | |

| Duration of type 1 diabetes (years) | 22 (15.9; 0.1–85) | 5 (1.5) | |

| Type of treatment | 8 (2.4) | ||

| Multiple daily insulin injections | 216 (66.5) | ||

| Insulin pump therapy | 109 (33.5) | ||

| Latest level of glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in % | 7.6 (1.3; 4.8–14.7) | 16 (4.8) | |

| Last diabetes counseling | 14 (4.2) | ||

| <6 months ago | 260 (81.5) | ||

| 7–12 months ago | 18 (5.6) | ||

| 13–24 months ago | 15 (4.7) | ||

| >2 years ago | 26 (8.2) | ||

| Relationship status | 18 (4.5) | ||

| Single | 76 (24.1) | ||

| Relationship | 52 (16.6) | ||

| Married | 158 (50.2) | ||

| Divorced | 23 (7.3) | ||

| Widowed | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Household | 17 (5.1) | ||

| Single | 52 (16.5) | ||

| Partner | 122 (38.5) | ||

| Family | 134 (42.4) | ||

| Friends | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Shared apartment | 7 (2.2) | ||

| Highest education | 21 (6.3) | ||

| Primary school | 9 (2.9) | ||

| Secondary school/high school | 52 (16.6) | ||

| Apprenticeship | 164 (52.6) | ||

| University | 87 (27.9) | ||

| Employment | 26 (7.8) | ||

| Apprenticeship/study | 21 (6.8) | ||

| Full time | 155 (50.5) | ||

| Part-time | 57 (18.6) | ||

| Unemployed | 12 (3.9) | ||

| Retired | 62 (20.2) | ||

| Have you ever had diabetic ketoacidosis yourself? | 22 (6.6) | ||

| Yes, once | 54 (17.4) | ||

| Yes, several times | 56 (18.0) | ||

| No | 98 (31.5) | ||

| I don’t know | 103 (33.1) | ||

| Do you feel that diabetic ketoacidosis is a dangerous complication of type 1 diabetes mellitus? | 18 (5.4) | ||

| Yes | 214 (67.9) | ||

| No | 28 (8.9) | ||

| I don’t know | 73 (23.2) | ||

| Can diabetic ketoacidosis be prevented? | 20 (6.0) | ||

| Yes | 237 (75.7) | ||

| No | 7 (2.2) | ||

| I don’t know | 69 (22) | ||

| Do you feel confident in treating a possible ketoacidosis? | 34 (10.2) | ||

| Yes | 120 (40.1) | ||

| No | 64 (21.4) | ||

| I don’t know | 115 (38.5) |

Means with SD, range, absolute number with percentage and number of missing values are given.

A total of 232 participants were from Switzerland (Cantonal Hospital Olten (n=104, 31.2%), University Hospital Basel (n=11, 3.3%), MedCenter Volta Basel (n=6, 1.8%), GZF Rheinfelden (n=37, 11.1%), Stoffwechselzentrum St Gallen (n=49, 14.7%), Cantonal Hospital Basel Land, Site Bruderholz (n=25, 7.5%)) and 101 participants (30.3%) from three German centers. Approximate mean response rate based on the average number of people living with T1D seen at each center was 48% and varied from 11% to 98%.

Patients’ awareness and self-evaluation of prevalence of DKA

A total of 220 (68%) of the respondents stated that they have heard about DKA and 103 (32%) did not hear or were not familiar with the term.

A total of 54 participants (17%) reported at least one and 56 patients (18%) several DKA episodes, whereas 98 individuals (32%) stated that they never had an episode. One hundred and three participants (33%) were unsure about DKA episodes. Approximately 40% of participants felt confident in managing DKA (see table 1). The majority of participants (n=214, 68%) reported that DKA is a dangerous complication, 28 participants (9%) did not agree and 73 participants (23%) were unsure about it. Asked about whether DKA can be prevented, 237 (76%) participants agreed, 7 (2%) individuals disagreed, and 69 (22%) were unsure about it.

Patients’ knowledge about DKA

When participants had to rate their knowledge about DKA on a scale from 0 (no idea at all) to 10 (excellent), median knowledge was 5 (IQR 1–7, mean 4.33, SD 3.1).

In the questionnaire, all individuals were asked to provide free-text answers concerning possible causes and symptoms of DKA. Of the participants, 185 individuals (55%) answered the causes question, while 181 participants (54%) answered the symptoms question. All individuals who answered the causes of DKA also completed the symptoms field.

Of the free-text answers given, 33 (18%) were not rated as correct or rated as inadequate causes of DKA (eg, ‘hypoglycaemia’, ‘no idea’, ‘too much insulin’, ‘acetonic’ or ‘fruity urine/odour’) and 15 (8%) answers were not rated as correct for possible symptoms of DKA.

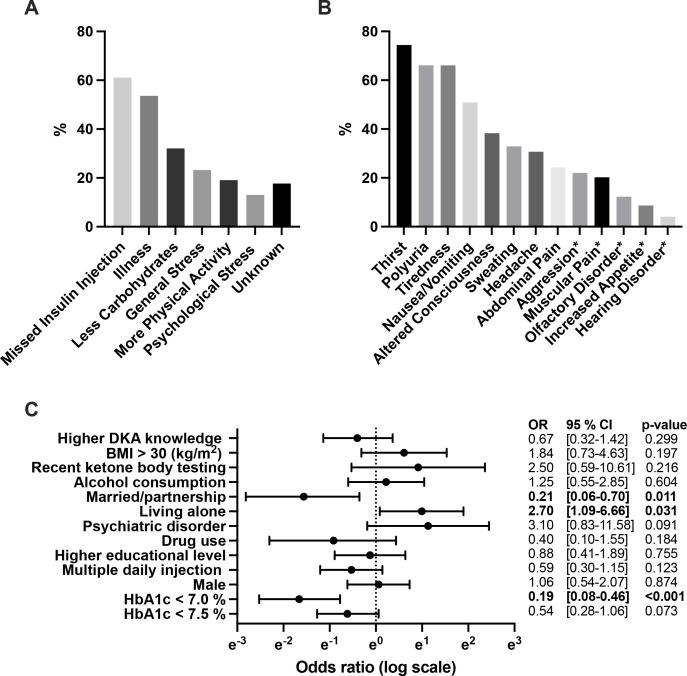

The most common multiple-choice causes of DKA were missed insulin injection (61%) and illness (54%) (see figure 1A). A total of 85 (25%) participants stated ‘too low’ or ‘forgotten insulin administration’ as causes of DKA, whereas 62 (19%) participants attributed ‘high glucose values’ and 5 (2%) participants specifically stated ‘pregnancy’, ‘stress’ and ‘diseases’ as causes of DKA.

Figure 1.

(A) Picked answer options for potential causes of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) by participants. (B) Most frequently picked DKA symptoms out of multiple answers to choose from. (C) ORs for individuals reporting no DKA compared with those with several experienced DKA episodes. ORs with 95% CI are depicted. *Indicates atypical symptoms. BMI, body mass index.

With regard to free-text symptoms of DKA most frequently ‘nausea’, ‘vomiting’ or ‘abdominal pain’ were mentioned by 59 (18%) participants; ‘Thirst’, ‘need to urinate’ or ‘dry mouth’ by 44 (13%) participants; and symptoms such as ‘fruity’ or ‘acetonic odour/urine’ by 33 (10%) participants. A total of 30 (9%) participants mentioned further symptoms of DKA such as ‘tiredness’, ‘sweating’, ‘visual disturbances’ or ‘coma’. Participants were then offered multiple-choice answers including atypical symptoms of DKA. Answers can be found in figure 1B. Symptoms not typical for DKA that were offered included aggression, muscular pain, olfactorial disorder, increased appetite and hearing disorder.

There was a significant but low positive correlation between diabetes duration and knowledge of DKA (Spearman r=0.187; 95% CI 0.0714 to 0.298; p=0.001).

Ketone body testing

A total of 185 (64%) individuals did not test for ketones at all, 124 (56%) participants tested less than every 6 months and 78 participants (38%) only if glucose was high or testing was needed. The last testing was longer than 1 year ago or never happened in a total of 165 participants (63%). A total of 148 individuals (60%) reported that their ketone test strips were either expired or they did not know (see table 2).

Table 2.

Ketone body testing

| Question | n (%) | Missing values (%) |

| Do you test for ketone bodies? | 23 (6.9) | |

| Yes | 74 (23.9) | |

| No | 197 (63.5) | |

| I don’t know | 39 (12.6) | |

| Frequency of testing for ketone bodies | 111 (33.3) | |

| Several times a week | 1 (0.5) | |

| 1×/week | 1 (0.5) | |

| 1×/month | 6 (2.7) | |

| 1×/every 6 months | 16 (7.2) | |

| Less frequent | 124 (55.9) | |

| Only if glucose is high/if needed | 78 (38.1) | |

| Last testing for ketone bodies | 72 (21.6) | |

| <1 month | 21 (8.0) | |

| <3 months | 23 (8.8) | |

| <6 months | 21 (8.0) | |

| <12 months | 31 (11.9) | |

| Longer than a year ago/never | 165 (63.2) | |

| Type of ketone body test | 84 (25.2) | |

| Urine | 99 (39.8) | |

| Blood | 62 (24.9) | |

| Both (urine and blood) | 17 (6.8) | |

| I don’t know | 71 (28.5) | |

| Glucose threshold for ketone body testing | 47 (14.1) | |

| <10 mmol/L (180 mg/dL) | 7 (2.4) | |

| 10–15 mmol/L (180–270 mg/dL) | 9 (3.1) | |

| 15–20 mmol/L (270–360 mg/dL) | 48 (16.8) | |

| >20 mmol/L (360 mg/dL) | 38 (13.3) | |

| I do not test | 185 (64.7) | |

| Are your ketone test strips good (ie, unexpired)? | 87 (26.1) | |

| Yes | 98 (39.8) | |

| No | 59 (24.0) | |

| I don’t know | 89 (36.2) |

Absolute numbers, percentages and missing values are given for common test for ketone bodies, including frequency of testing, last time point, type of ketone body test, glucose threshold and whether ketone body test strips are not expired.

HbA1c levels and incidence of DKA

Participants who reported having had one or more episodes of DKA (n=104) had significantly higher HbA1c levels compared with those who reported not having DKA (n=96) (mean HbA1c: 7.8% (SD 1.3) vs 7.3% (SD 1.0), p=0.009). Individuals who were unsure about previous DKA episodes (n=98) had significantly higher HbA1c levels compared with those who reported not having DKA episodes (n=96) (mean HbA1c: 7.7% (SD 1.4) vs 7.3% (SD 1.0), p=0.029).

Use of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with T1D

A total of 14 individuals (4.2%) reported the use of SGLT2 inhibitors (ertugliflozin (n=1, 0.3%), empagliflozin (n=3, 0.9%), dapagliflozin (n=8, 2.5%), canagliflozin (n=2, 0.6%)).

Substance use

When questioned about alcohol consumption, the survey findings indicated that 31 participants (14.5%) reported complete abstinence from alcohol, 77 participants (36%) claimed infrequent drinking, and 10 participants (4.7%) mentioned consuming alcohol daily.

Regarding substance use in general, 186 participants (87.7%) reported no substance use, while 16 participants (7.5%) disclosed past substance use. Additionally, 10 participants (4.7%) admitted to current substance use. Among the substances reported, the most frequently used was cannabis (n=24), followed by cocaine (n=2) and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD, n=2).

Associated factors for DKA

Improved glycemic control (HbA1c <7.0% compared with 8% and higher) showed a protective effect against DKA (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.46, p<0.001). Additionally, being in a partnership or being married, as opposed to being divorced or widowed, was also found to be a protective factor (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.70, p=0.011). Conversely, living alone, as opposed to other forms of cohabitation, increased the likelihood of experiencing multiple episodes of DKA (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.09 to 6.66, p=0.031) (see figure 1C).

Healthcare professionals’ assumption of patients’ knowledge

Estimates of the individual’s personal knowledge on DKA were reported by healthcare professionals only from the Swiss centers on a scale from 0 (no knowledge at all) to 10 (perfect knowledge and management of DKA). Median knowledge on DKA was rated as 6 (IQR 4–7). The patients’ personal knowledge on DKA was rated significantly lower by themselves (mean 4.33, SD 3.11 vs 5.60, SD 2.34; p<0.0001) compared with their healthcare professionals’ assumption. However, the two ratings correlated significantly (r=0.268, 95% CI (0.1253; 0.3992), p=0.0002).

Individual needs regarding DKA

In response to inquiries about their needs related to DKA, 201 participants (66.6%) expressed a desire for additional information regarding the condition. Conversely, 42 individuals (13.9%) were uncertain about their informational requirements, while 59 participants (19.5%) reported feeling adequately informed (see table 3).

Table 3.

Patient-perceived needs for further information regarding DKA, as well as the type of information material preferred by participants, and automated prescription of ketone measuring strips once a year

| Question | n (%) | Missing values (%) |

| Would you like more information about diabetic ketoacidosis? | 31 (9.3) | |

| Yes | 201 (66.6) | |

| No | 59 (19.5) | |

| I don’t know | 42 (13.9) | |

| What would help you learn more about diabetic ketoacidosis? | 39 (11.7) | |

| Information leaflets (eg, brochures) | 166 (56.5) | |

| Diabetes counseling | 51 (17.3) | |

| Physician counseling | 112 (38.1) | |

| Online training (eg, webinar) | 63 (21.4) | |

| Other | 11 (3.7) | |

| Should the test strips be prescribed by the attending physician as standard with the annual prescription? | 41 (12.3) | |

| Yes | 165 (56.5) | |

| No | 46 (15.8) | |

| I don’t know | 81 (27.7) |

Given are absolute numbers, missing values and percentage.

DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis.

The majority of individuals preferred information leaflets (n=166, 56.5%) and counseling by a diabetes nurse (n=51, 17.3%), followed by personal counseling through their treating physician, online training/webinars or other means (see table 3).

Of all participating study sites, two reported having a dedicated DKA program for counseling of people living with T1D.

Discussion

Despite significant advances in monitoring technologies as well as insulin therapeutics, rates of both outpatient and hospital-acquired DKA have increased significantly over the past years.9

Key factors in the prevention of DKA are early detection and adequate patient education.18 Our results show that people living with T1D do not seem to be adequately informed about DKA despite being treated in specialized centers. A total of 32% had never heard of or were unfamiliar with it. Although the majority of participants (68%) stated that DKA is a dangerous condition, 46% of individuals could not name a single symptom of DKA, and 45% could not spontaneously recall possible causes of DKA.

In our cohort, the majority of participants (69%) reported either part-time or full-time employment, and a significant portion (83.5%) did not live alone. Our analysis revealed that being in a partnership or being married, in comparison to being divorced or widowed, acted as a protective factor against DKA (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.70). Conversely, living alone, rather than other forms of cohabitation, substantially increased the likelihood of experiencing multiple episodes of DKA (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.09 to 6.66). It has been reported that being married is associated with lower HbA1c levels,19 which may explain in part also a lowered risk of DKA, but data on marital status or cohabitation on DKA risk are lacking and our findings need further investigation.

The average HbA1c in our cohort was 7.6%, which is slightly above the recommended target of <7% set by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.20 However, it is still lower than what would be expected for non-adherence and consistent with HbA1c levels of other specialized diabetes centers.21 22 Interestingly, our findings indicate that patients who reported experiencing one or more episodes of DKA, as well as those who were uncertain about their DKA history, had significantly higher HbA1c levels compared with patients who reported no DKA episodes. Additionally, our results show that achieving improved glycemic control (HbA1c <7.0% compared with 8% and higher) appears to have a protective effect against DKA (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.46). These associations are consistent with the findings of Weinstock et al, who observed a correlation between DKA occurrences and HbA1c levels, particularly noting that DKA is more prevalent at HbA1c levels of ≥10.0% (≥86 mmol/mol).6

A minority of 4.2% of individuals reported the use of SGLT2 inhibitors, with dapagliflozin being the most common (n=8, 2.5%). The use of SGLT2 inhibitors in T1D was still authorized at the time of patient enrollment and remains an ongoing topic of discussion due to their impressive cardiorenal benefits.23 In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Huang et al showed that the use of dapagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin therapy in people living with T1D provided significant benefits in terms of HbA1c, weight loss, average daily blood glucose and average daily blood glucose variability, and did not increase the risk of infection, DKA or discontinuation due to adverse events compared with placebo.24 On the other hand, the risk of developing euglycemic DKA remains a significant limiting factor. Time will tell whether SGLT2 inhibitors will find their way into T1D treatment guidelines. However, if so, a strong improvement of patients’ knowledge about DKA has to be demanded to make the use as safe as possible.

Regarding the management of DKA, increased home ketone monitoring may lead to self-management of ketoacidosis prior to hospital admission and thus improve individual outcomes.25 However, in our cohort, 60% of participants reported that their ketone test strips were either expired or they did not know.

A total of 67% of individuals wanted more information about the condition of DKA, particularly through general information and discussion with their doctor. Healthcare professionals play an important role in the prevention of DKA. In our study, patient-reported knowledge of DKA did not match the perceived knowledge of their healthcare professionals, who rated patients’ knowledge significantly higher than the patients themselves. These findings suggest a communication gap in the physician–patient relationship. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care as well as other societies strongly recommend education about DKA in people living with diabetes and several programs and practical recommendations do exist25 26 even for individuals treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.27 In particular, they recommend counseling about precipitating factors and early warning symptoms, including the rules about sick days.25 28 They also emphasize the involvement of healthcare professionals by including an assessment of the individual’s understanding of DKA. Participation in a structured diabetes (self-)education program leads to a substantial risk reduction of DKA and is cost-effective, as shown by numerous studies.7 29–32 However, our results suggest that DKA seems to play a minor role or used means in adults are less effective in the management of T1D among physicians and diabetes nurses, or that the tools used in adults are less effective. There is a need for appropriate patient education.

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to assess knowledge of DKA with more than 300 participants in two countries and different institutions. The fact that the questionnaire was developed in collaboration with a professional diabetes instructor and two individuals with T1D and that the response rate was high are further strengths of the study.

The study also has some notable limitations. First, the study was conducted only in Germany and Switzerland, which limits the generalizability of the results, especially with regard to other healthcare systems. Second, the simple survey design, using a non-validated instrument, as well as the observational nature of the study, inherently limits the study. The anonymous survey design was chosen to prevent participants from feeling judged since assessing knowledge may be a sensitive matter, and thereby bearing the risk for a lower participation rate. Answers reflect individuals’ knowledge and perceptions rather than documenting their actual medical history, rate of DKA episodes and HbA1c history. Although current HbA1c value assessed in the questionnaire may not represent the general quality of diabetes therapy adherence and the questions regarding DKA episodes do not specify the exact duration since the last occurrence, participants’ reports indicate significant knowledge gaps and unmet needs that are important for future DKA prevention strategies. Since participation in the study was entirely voluntary, it is possible that a selection bias may exist, with a higher likelihood of motivated, skilled and compliant individuals participating. Given our study findings, this could potentially reflect even greater knowledge gaps within the broader population of individuals with T1D.

In addition, participation varied widely between centers in Switzerland, with few participants from the University Hospital Basel. As patients treated at the University Hospital tend to be more complex cases and are treated more often by physicians in training, this may not reflect the average situation of people living with T1D anyway.

Conclusion

This study represents the first multicenter survey examining individuals’ perceived knowledge gaps and unmet needs concerning DKA, including insights from treating physicians. The findings highlight a lack of participants’ knowledge about DKA and its management as well as a communication gap regarding DKA within the physician–patient relationship with a widespread desire for education. To optimize future prevention strategies for DKA, it appears crucial to prioritize two key areas. First, addressing the existing knowledge gaps surrounding DKA by incorporating the topic in the individual consultation is essential. Second, it is important to consider and include protective factors in the treatment of T1D to reduce the prevalence of DKA and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank all individuals for participating in this study and especially Mrs Claudia Weiss, registered diabetes counselor, for her critical revision of the questionnaire and her feedback.

Footnotes

Presented at: Parts of this work were presented at the 24th Annual Meeting of the European Society of Endocrinology in May 2022 in Milan, Italy.

Contributors: GR and MH planned the study. All authors were involved in the acquisition of data. MH and Sebastian Stiebitz entered the data in the databank. Sebastian Stiebitz and MH performed the statistical analysis. MH and PR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in the interpretation of data and critical review of the manuscript and approved the manuscript to be submitted for publication. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. GR is the guarantor of the clinical content of this submission. GR is the guarantor of the clinical content of this submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in compliance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki, the ICH-GCP and national legal and regulatory requirements. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of ‘Nordwest-und Zentralschweiz’ and did not require authorization (EKNZ Req 2021-00116). Since only anonymous data were collected, no particular consent needed to be obtained.

References

- 1.Dhatariya KK, Glaser NS, Codner E, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:40. 10.1038/s41572-020-0165-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibb FW, Teoh WL, Graham J, et al. Risk of death following admission to a UK hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetologia 2016;59:2082–7. 10.1007/s00125-016-4034-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umpierrez G, Korytkowski M. Diabetic emergencies - ketoacidosis, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state and hypoglycaemia. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016;12:222–32. 10.1038/nrendo.2016.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrmann D, Kulzer B, Roos T, et al. Risk factors and prevention strategies for diabetic ketoacidosis in people with established type 1 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020;8:436–46. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30042-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalscheuer H, Seufert J, Lanzinger S, et al. Event rates and risk factors for the development of diabetic ketoacidosis in adult patients with type 1 diabetes: analysis from the DPV Registry based on 46,966 patients. Diabetes Care 2019;42:e34–6. 10.2337/dc18-1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstock RS, Xing D, Maahs DM, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:3411–9. 10.1210/jc.2013-1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindner LME, Rathmann W, Rosenbauer J. Inequalities in glycaemic control, hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis according to socio-economic status and area-level deprivation in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabet Med 2018;35:12–32. 10.1111/dme.13519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency EEM. Forxiga (Dapagliflozin) 5mg should no longer be used for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus. 2021. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/dhpc/forxiga-dapagliflozin-5mg-should-no-longer-be-used-treatment-type-1-diabetes-mellitus#documents-section

- 9.Benoit SR, Hora I, Pasquel FJ, et al. Trends in emergency department visits and inpatient admissions for hyperglycemic crises in adults with diabetes in the U.S., 2006-2015. Diabetes Care 2020;43:1057–64. 10.2337/dc19-2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebrahimi F, Kutz A, Christ ER, et al. Lifetime risk and health-care burden of diabetic ketoacidosis: a population-based study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:940990. 10.3389/fendo.2022.940990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan F, Paladino L, Sinert R. The impact of COVID-19 on diabetic ketoacidosis patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2022;16:102389. 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azevedo LCP, Choi H, Simmonds K, et al. Incidence and long-term outcomes of critically ill adult patients with moderate-to-severe diabetic ketoacidosis: retrospective matched cohort study. J Crit Care 2014;29:971–7. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramaesh A. Incidence and long-term outcomes of adult patients with diabetic ketoacidosis admitted to intensive care: a retrospective cohort study. J Intensive Care Soc 2016;17:222–33. 10.1177/1751143716644458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elhassan ABE, Saad MME, Salman MST, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis: knowledge and practice among patients with diabetes attending three specialized diabetes clinics in Khartoum, Sudan. Pan Afr Med J 2022;41:299. 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.299.31129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alreshidi NF, Altamimi SS, Alharbi AN, et al. Assessment of awareness and practice toward diabetic ketoacidosis among diabetic patients and their Caregivers in hail region. Biomed Res Int 2022;2022:2904910. 10.1155/2022/2904910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The Redcap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (Redcap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustafa OG, Haq M, Dashora U, et al. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS) in adults: an updated guideline from the joint British diabetes societies (JBDS) for inpatient care group. Diabet Med 2023;40:e15005. 10.1111/dme.15005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford KJ, Robitaille A. How sweet is your love? Disentangling the role of marital status and quality on average glycemic levels among adults 50 years and older in the English longitudinal study of ageing. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2023;11:e003080. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2022-003080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A, et al. The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the study of diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2021;44:2589–625. 10.2337/dci21-0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roser P, Kalscheuer H, Groener JB, et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening ratio is improved when using a digital, nonmydriatic fundus camera onsite in a diabetes outpatient clinic. J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:4101890. 10.1155/2016/4101890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermann JM, Miller KM, Hofer SE, et al. The transatlantic Hba1C gap: differences in glycaemic control across the LifeSpan between people included in the US T1D exchange registry and those included in the German/Austrian DPV registry. Diabet Med 2020;37:848–55. 10.1111/dme.14148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor SI, Blau JE, Rother KI, et al. Sglt2 inhibitors as adjunctive therapy for type 1 diabetes: balancing benefits and risks. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:949–58. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30154-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Jiang Z, Wei Y. Efficacy and safety of the Sglt2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp Ther Med 2021;21. 10.3892/etm.2021.9813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhatariya KK, JBDSfI C. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults-an updated guideline from the joint British diabetes society for inpatient care. Diabet Med 2022;39:e14788. 10.1111/dme.14788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans NR, Richardson LS, Dhatariya KK, et al. Diabetes specialist nurse telemedicine: admissions avoidance, costs and Casemix. European Diabetes Nursing 2012;9:17–21. 10.1002/edn.198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldenberg RM, Gilbert JD, Hramiak IM, et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors, their role in type 1 diabetes treatment and a risk mitigation strategy for preventing diabetic ketoacidosis: the STOP DKA protocol. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019;21:2192–202. 10.1111/dom.13811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldenberg RM, Berard LD, Cheng AYY, et al. Sglt2 inhibitor-associated diabetic Ketoacidosis: clinical review and recommendations for prevention and diagnosis. Clin Ther 2016;38:2654–64. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elliott J, Jacques RM, Kruger J, et al. Substantial reductions in the number of diabetic ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycaemia episodes requiring emergency treatment lead to reduced costs after structured education in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2014;31:847–53. 10.1111/dme.12441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deeb A, Yousef H, Abdelrahman L, et al. Implementation of a diabetes educator care model to reduce paediatric admission for diabetic ketoacidosis. J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:3917806. 10.1155/2016/3917806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King BR, Howard NJ, Verge CF, et al. A diabetes awareness campaign prevents diabetic Ketoacidosis in children at their initial presentation with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2012;13:647–51. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanelli M, Chiari G, Ghizzoni L, et al. Effectiveness of a prevention program for diabetic Ketoacidosis in children. an 8-year study in schools and private practices. Diabetes Care 1999;22:7–9. 10.2337/diacare.22.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjdrc-2023-003662supp001.pdf (72.3KB, pdf)

bmjdrc-2023-003662supp002.mp4 (2.8MB, mp4)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.