Abstract

We present a case of successful resection of a large right upper quadrant retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma involving multiple adjacent organs, initially considered inoperable in a patient in his 40s. This case highlights the importance of extensive preoperative planning and a multidisciplinary approach in achieving a greater chance of curative resection. Preoperative optimisation included neoadjuvant chemotherapy, concurrent portal vein embolisation and hepatic vein embolisation. The patient then underwent en-bloc resection, including total pancreatectomy, hemihepatectomy and vena caval resection in conjunction with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and percutaneous venovenous bypass.

Keywords: Cancer intervention, Pancreas and biliary tract, Oncology, Interventional radiology, Surgical oncology

Background

Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare malignancies, comprising less than 1% of all cancers.1 Liposarcomas are the most common tumour of the retroperitoneum and originate from mesenchymal tissues.2 Liposarcomas are classified into well-differentiated (WD) or dedifferentiated (DD), myxoid/round and pleomorphic types.2 DD liposarcomas are more aggressive and metastatic than their counterparts and are characterised by the coexistence of WD and poorly differentiated non-lipogenic areas in the same specimen.3

As retroperitoneal tumours commonly remain asymptomatic until the resultant compression of surrounding structures, they are unfortunately often diagnosed only once they reach a considerable size. The large size at diagnosis and the frequently associated invasion of critical organs and major blood vessels make surgical resection challenging and high risk.

Based on current guidelines, complete resection of localised retroperitoneal liposarcomas with microscopically negative surgical margins remains the recommended practice in achieving potentially curative treatment.4 Despite aggressive treatment, 80% of DD liposarcomas will recur locally within 3 years and ultimately cause death in 75% of patients.5 The potential for en-bloc resection with adjacent organs/structures must be weighed against the operative risk and mortality.5

Resections involving the kidneys and colon are more widely accepted due to the low risk of morbidity. In contrast, liver, pancreatic and vena caval resections are more controversial, being associated with increased operative risk, morbidity and mortality.6

Portal vein embolisation (PVE) enables increased liver remnant volume over several weeks to avoid post resection liver failure.7 Concurrent PVE and hepatic vein embolisation (PVE/HVE) lead to a higher percentage of liver hypertrophy when compared with PVE alone, resulting in a larger future liver remnant.8 Both PVE and PVE/HVE have been demonstrated to expand the limitation of technical resectability for liver tumours and metastases.9

Oncological resections of retroperitoneal sarcomas may require the replacement of the inferior vena cava (IVC).10 Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and percutaneous venovenous bypass (pVVB) have been instituted to reduce blood loss and maintain intraoperative patient stability in retroperitoneal sarcoma resections requiring IVC replacement.11

Case presentation

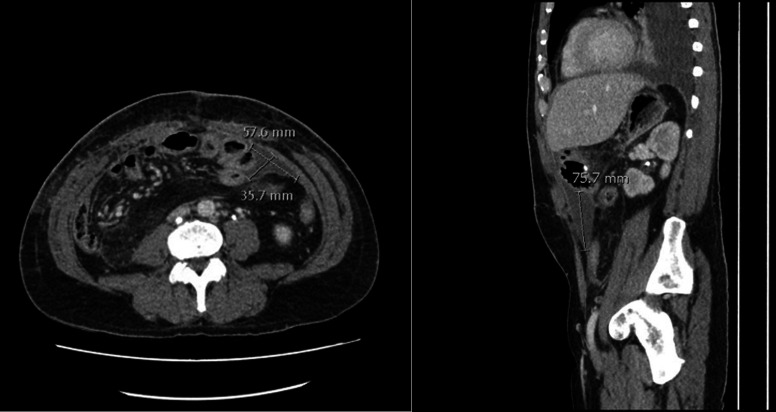

A previously well man in his 40s presented with a 12-month history of arthralgia, generalised fatigue, night sweats, reduced exercise tolerance, loss of muscle bulk and headaches. He was initially investigated by Infectious Disease and Immunology Physicians, given his persistently raised inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate >100). During his investigation, a CT scan of his chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a sizeable heterogenous mass centred in the right kidney, which extended into the right lobe of the liver and encased the right renal vein (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial CT scan demonstrating large right retroperitoneal tumour involving the right lobe of the liver and right kidney.

Investigations

CT-guided core biopsy of the mass revealed an atypical spindle cell neoplasm with high-level murine double minute clone 2 amplification favoured to represent a DD liposarcoma.

The patient was referred to the WA State Sarcoma service for further preoperative investigation. Staging fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed high-grade activity of the right retroperitoneal lesion, low-grade activity in the left axillary lymph nodes (thought to be reactive secondary to recent vaccinations), and no metastases (figure 2). CT chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated extension into liver segments 6, 7 and 8, right hemidiaphragm and pleural space, a lack of separation from the duodenum and colon and severe compression of the retrohepatic portion of the IVC. MRI of the liver confirmed hepatic and IVC involvement.

Figure 2.

Staging positron emission tomography (PET) scan demonstrating high-grade activity of right retroperitoneal lesion and low-grade activity in left axillary lymph nodes.

Dynamic planar and single-photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) liver quantification imaging with technetium (99mTc) mebrofenin predicted normalised liver remnant function to be 3.1%/min/m2 and remnant volume to be 33%, suggesting borderline residual hepatic function and volume following proposed extensive multivisceral resection.

Treatment

To increase the liver capacity, a right PVE/HVE was performed by selective embolisation of the right portal vein branches with a glue/lipidol mix (1:5), followed by deployment of an 18 mm Amplatzer vascular plug II (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA) in the distal right hepatic vein (RHV; figure 3). By maintaining the catheter position distal to the plug, the reduced flow enabled aliquots of glue/lipidol mix (1:3) to be injected to fill the RHV territory upstream. The patient underwent a 6-week regeneration period to allow for liver hypertrophy.

Figure 3.

Fluoroscopic image demonstrating embolisation and vascular plug of the right portal vein and right hepatic vein.

Gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed a high-grade duodenal stricture highly suspicious for tumour infiltration into the lateral wall of the duodenum and IVC involvement, respectively. The patient was given a neoadjuvant course of doxorubicin/ifosfamide to downstage the tumour and facilitate surgical resection. Chemotherapy resulted in nausea and dehydration, requiring admission for intravenous fluid and antiemetics and a consequent 2-day break in chemotherapy. Three cycles were completed before restaging.

Restaging CT, FDG-PET and MRI demonstrated stable tumour size with no distant metastasis and hypertrophy of the left lobe of the liver post embolisation (figure 4). Repeat SPECT liver quantification imaging 6 weeks post embolisation demonstrated a predicted liver remnant function of 5.2%/min/m2 and remnant liver volume of 45%, correlating with adequate function following right hemihepatectomy (figure 5). Restaging gastroscopy and EUS showed an ulcerated lesion at the D1/2 junction, representing ongoing duodenal and IVC involvement with loss of the fat plane.

Figure 4.

Restaging PET scan demonstrating stable metabolic appearances of large intensely avid right upper quadrant lesion involving right hepatic lobe, right kidney and right adrenal gland.

Figure 5.

(A) Pre-embolisation Liver quantification single-photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) scan. (B) Post-embolisation Liver quantification SPECT scan demonstrating increased liver remnant function.

As with all cases of sarcoma in WA, the patient details, pathology and restaging imaging were reviewed at the WA State Sarcoma multidisciplinary team meeting, with the recommendation to proceed with mass resection, including total pancreatectomy to eliminate the possibility of a pancreatic leak or anastomotic failure. The patient received preoperative vaccines for planned splenectomy as per the standard of care.

Bilateral ureteric JJ stents were placed at the beginning of the procedure to facilitate identification during resection. En-bloc resection comprised right hemi-hepatectomy, right hemicolectomy, Whipple’s procedure, right nephroureterectomy, resection of a portion of the right diaphragm and partial IVC resection. The patient was commenced on ECMO bypass with pVVB before the commencement of the IVC resection and remained stable on this for a total of 4 hours before cessation following completion of liver and IVC resection. The retrohepatic IVC involvement was measured at approximately 13 mm below the middle hepatic vein (MHV) and left hepatic vein (LHV) common trunk. This allowed top IVC control following short hepatic veins and RHV division without blocking the remnant liver outflow through MHV and LHV. An anterior approach liver resection was essential to split the liver parenchyma to access the retro hepatic IVC without liver mobilisation. The IVC was replaced with a 20 mm polytetrafluoroethylene graft.

The tail of the pancreas and spleen were resected separately, resulting in a total pancreatectomy to reduce the risk of a pancreatic leak postoperatively. A right-sided chest drain was inserted intraoperatively, and the diaphragmatic defect was closed with continuous sutures. The resected en-bloc specimen weighed 2315 g (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Large retroperitoneal tumour (arrow) resected en-bloc with right hemihepatectomy (a), a segment of inferior vena cava (b), right kidney (c) and ureter, duodenum (d), pancreas (e), and right hemicolectomy (f).

Histopathological examination of the 150×120×80 mm tumour demonstrated evidence of full-thickness invasion of the duodenum with mucosal ulceration, full-thickness invasion of the IVC without intraluminal extension and full-thickness invasion of the diaphragm without breaching of the overlying parietal pleural lining. There was also invasion of the right kidney and the outer wall of the colon at the hepatic flexure but without mucosal ulceration (figure 7). No evidence of involvement of the pancreas or right ureter was identified. The tumour was clear of the liver margin, less than 1 mm from the soft-tissue margin overlying the bare area of the liver adjacent to the diaphragm and involved the soft-tissue margin just adjacent to the IVC at the level of the pancreas in the en-bloc specimen (figure 7). An additional specimen of tissue that overlayed the area of the positive margin adjacent to the IVC was free of tumour. Three reactive lymph nodes were identified in the en-bloc resection specimen and one reactive lymph node identified in the distal pancreatectomy/splenectomy specimen, all showing reactive changes with no metastases.

Figure 7.

Histopathological specimen—right retroperitoneal tumour. (A) Spindle cell mesenchymal neoplasm invading right kidney. (B) Spindle cell mesenchymal neoplasm invading right lobe of the liver.

His early postoperative course was uneventful, with a 3-day ICU admission postoperatively for monitoring. The patient was extubated on day one post-op with no complications, required no inotropes and received intravenous albumin for an acute kidney injury which resolved in ICU. Two weeks post resection, recovery was complicated by bleeding from ulceration at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, which was treated with endoscopic clipping of a crossing vessel, epinephrine injection and high-dose proton-pump inhibitors.

CT was performed given ongoing tachycardia and rising inflammatory markers at 3 weeks post resection, which demonstrated a left sided intra-abdominal collection (figure 8). An ultrasound-guided aspiration and insertion of a percutaneous drain into a left-sided seroma was performed 3 weeks post resection and was removed after 48 hours. There were no other intra-abdominal collections that required drainage throughout the recovery period.

Figure 8.

CT demonstrating postoperative seroma requiring percutaneous drainage.

In addition, the patient developed a right-sided chylothorax 4 weeks post-op, initially managed with drainage via an intercostal catheter with a total of 1.25 L drained (figure 9). The patient was given midodrine and a fat-free diet which was gradually upgraded to a diet of 50 g per day of fat on discharge.

Figure 9.

(A) Chest X-ray demonstrating right-sided chylothorax. (B) Chest X-ray demonstrating drainage of chylothorax post insertion of the intercostal catheter. (C) Chest X-ray at 6-week follow-up demonstrating resolution of right-sided chylothorax.

The patient was discharged home just over 1 month post resection. The patient received subcutaneous heparin injections at a prophylactic dose from day 2 post-op. Then, he was established on therapeutic anticoagulation for his IVC graft with subcutaneous enoxaparin post treatment of gastrointestinal bleed. The patient was transitioned to rivaroxaban 3 days before discharge with no complications. A basal-bolus insulin regime for diabetes post total pancreatectomy was initiated, and pancreatic enzyme supplementation with meals. His case was discussed at the state sarcoma MDT, where the recommendation against further chemotherapy was made due to a known poor response to neoadjuvant treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

At 6 weeks post resection, the patient’s chylothorax had resolved, and he was tolerating a regular diet with 10 kg of weight gain (figure 9). His blood sugar level was stable on insulin regime, his wounds were well healed and ureteric stents had been removed at 5 weeks post-op. Postoperative vaccinations were given at 8 weeks post resection to prevent overwhelming post-splenectomy infection as well as prophylactic antibiotics. The patient had returned to work, and the most recent surveillance CT scan imaging at 12 months postresection interval demonstrated no evidence of recurrence or metastasis.

Discussion

Liposarcomas are the most common malignancy of the retroperitoneum and makeup 0.07–0.2% of all neoplasms.12 Patients with retroperitoneal tumours often present when the tumours have grown significantly, making surgical resection challenging. DD liposarcomas are more likely to invade surrounding structures than their WD counterparts, highlighted in this case by the infiltration of the liver, kidney, adrenal, duodenum, IVC and diaphragm. Given the aggressive nature of DD liposarcomas, current guidelines state that the best chance of curative resection is at primary presentation.4 13 Surgical resections should aim for a single en-bloc specimen and macroscopically complete resection with systematic resection of adherent viscera, given the uncertainty regarding margin definition. This is best done by resecting the tumour en-bloc with adherent structures, preserving specific organs where possible.

A series from a UK referral centre from 2009 to 2013 found that 80% of patients who underwent extended resections had negative microscopic tumour margins in up to 90% of patients. The most frequently resected organs in this series were the colon and kidney.5

Resection of the pancreas is controversial due to the higher incidence of intra and postoperative complications. This patient underwent a total pancreatectomy to eliminate the risk of pancreatic fistula, which is well-recognised in partial pancreatectomy and can result in sepsis and death. The literature is variable on this issue as all studies are retrospective and have heterogeneous comparative groups.

A recent retrospective review comparing patients who underwent distal pancreatectomy (including splenectomy) against those without distal pancreatectomy, as part of en-bloc resections of left upper quadrant retroperitoneal sarcomas, found that complication rates were similar between the two groups (including post-operative bleeding, lymphatic leak, sepsis, pancreatic fistula and ICU admission).6 Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) occurred in 18% of patients who underwent distal pancreatectomy; however, all cases were classified as grade B according to the International Study Group for Pancreatic Fistula score with no cases of organ failure, return to theatre or death.14 These results demonstrated a slight improvement in morbidity outcomes from previous studies, which had rates of 19% grade B POPF and 5% grade C POPF, suggesting there is no significant increased risk in performing distal pancreatectomy as part of en-bloc resection.

The Whipple procedure or pancreaticoduodenectomy is a complex operation most frequently performed for cancers affecting the head of the pancreas or duodenum. A Trans-Atlantic Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Working Group study has previously demonstrated that including a PD was a significant independent risk factor for complications.15 The most extensive study of PD in the management of retroperitoneal sarcomas found that the rates of major complications were moderate, with 34% of patients experiencing grade 3 or higher complications.16 Clinically significant pancreatic leaks (grade B or C) developed in 28% of patients following PD, and the mortality rate of the entire study population was 3.4% in the postoperative period.16

Preservation of the spleen during distal pancreatectomy is often used to resect benign or low-grade pancreatic lesions to preserve immunologic function and reduce the risk of postoperative infective complications.17 A meta-analysis suggested that splenic preservation resulted in better short-term outcomes when compared with distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy with less infectious complications, operative blood loss and overall morbidity rate in patients with pancreatic lesions.17 There is a lack of evidence regarding splenic preservation in retroperitoneal sarcoma resections; however, retroperitoneal sarcomas often require concomitant multiorgan resection, and the risks of complications can be additive with each component of the resection. In this case, the total pancreatectomy as part of the en-bloc resection included resection of the splenic artery and thus, splenic preservation was not technically possible.

Using liver quantification scans is essential in predicting liver function in the remnant and, therefore, the risk of liver failure and requirement for transplantation. The DRAGON 1 study is an ongoing prospective one-arm study looking at the safety and feasibility of PVE/HVE for patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases. A recent analysis of results from centres participating in the study confirmed that PVE/HVE results in more significant hypertrophy than PVE alone, with larger resectability levels without a significant difference in major complications or mortality.18 The overall complication rate of PVE/HVE was similar to that of PVE at 15% and 15.6%, respectively.18 Complications associated with PVE/HVE were post embolisation syndrome, which was characterised by postprocedural pain and fever.18 One patient died due to septic shock from infected tumour necrosis.18 Preoperative PVE/HVE was performed successfully, increasing the future liver volume such that adequate function was maintained post-right hemihepatectomy. Our patient’s embolisation had no complications, and clear liver margins were obtained with resection. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports documenting a retroperitoneal sarcoma resection involving preoperative PVE/HVE to facilitate extended resection and implementing PVE/HVE before extended resection shows promise in extending the population eligible for potentially curative resection. This would redefine the prognosis of these patients who would otherwise have limited treatment options.

Resection of the IVC as part of en-bloc oncologic resections of retroperitoneal sarcomas is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.19 IVC clamping leads to reduced cardiac output and hypotension, which can be challenging to manage intraoperatively. In addition, prolonged clamping may result in metabolic acidosis, leading to impaired myocardial function and subsequent cardiac arrest.11 A recent series of 16 patients requiring IVC resection as part of en-bloc retroperitoneal sarcoma resections demonstrated that using pVVB and ECMO improved haemodynamic stability intraoperatively with only one patient having haemodynamic intraoperative instability with an average bypass time of 148 min.11 Maintaining haemodynamic stability intraoperatively reduces bleeding, maintains stable organ perfusion, allows more time for a considered complex resection, such as in this case, where decisions are required during resection, and reduces time pressure on the surgical team during long, complex surgery over many hours.

Iatrogenic chylothorax accounts for approximately 80% of traumatic chylothorax, developing from intraoperative thoracic duct injuries and resulting in an exudative pleural effusion.20 Conservative management of chylothorax involves pleural cavity drainage, reduction of chyle flow and nutritional support.21 Drainage of chylothorax via gravity-assisted chest tube reduces risks of respiratory complications by encouraging lung re-expansion.22 Nutritional approaches to reducing chyle flow include eliminating dietary fat, as observed in this case, which may allow the thoracic duct injury to heal spontaneously.21 Sympathomimetic medications such as etilefrine and midodrine cause smooth muscle contraction in lymphatic vessels, reduced chyle flow and increased chance of spontaneous resolution, as in this case.23

Given the complexity and challenges associated with surgical resection of retroperitoneal sarcomas, often requiring multimodal treatments, an MDT approach is needed to achieve optimal outcomes. In cases like this, the combined involvement of sarcoma specialist surgeons, hepatobiliary surgeons, vascular surgeons, urologists, cardiac anaesthetists, medical oncologists, pathologists, interventional radiologists, perfusionists, ICU and specialist nursing staff allows for successful treatment. With a multidisciplinary approach, complex resections such as this become techinically possible

Learning points.

Patients with retroperitoneal sarcomas often present with large tumours invading surrounding structures. Extensive preoperative planning and a multidisciplinary approach are essential in achieving a greater chance of curative resection.

Total pancreatectomy may reduce the postoperative risk profile where oncological resection requires distal or pancreaticoduodenectomy, given the elimination of the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistulae.

Implementing portal vein embolisation/hepatic vein embolisation before extended sarcoma resection may improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with otherwise inoperable tumours.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank PathWest for the provision of images and the diagnostic work-up of the case.

Footnotes

Contributors: The following authors were responsible for drafting of the text, sourcing and editing of clinical images, investigation results, drawing original diagrams and algorithms, and critical revision for important intellectual content: all authors. The following authors gave final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Ki EY, Park ST, Park JS, et al. A huge Retroperitoneal Liposarcoma: case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2012;33:318–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Board WCoTE . Soft tissue and bone tumours. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conyers R, Young S, Thomas DM. Liposarcoma: molecular Genetics and Therapeutics. Sarcoma 2011;2011:483154. 10.1155/2011/483154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gronchi A, Miah AB, Dei Tos AP, et al. Soft tissue and visceral Sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann Oncol 2021;32:1348–65. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquali S, Vohra R, Tsimopoulou I, et al. Outcomes following extended surgery for Retroperitoneal Sarcomas: results from a UK referral centre. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3550–6. 10.1245/s10434-015-4380-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KD, Lee KW, Lee JE, et al. Postoperative outcomes of distal Pancreatectomy for Retroperitoneal sarcoma Abutting the Pancreas in the left upper quadrant. Front Oncol 2021;11:792943. 10.3389/fonc.2021.792943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orcutt ST, Kobayashi K, Sultenfuss M, et al. Portal vein Embolization as an Oncosurgical strategy prior to major hepatic resection: anatomic, surgical, and technical considerations. Front Surg 2016;3:14. 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heil J, Schadde E. Simultaneous portal and hepatic vein Embolization before major liver resection. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2021;406:1295–305. 10.1007/s00423-020-01960-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang SY, Aloia TA. Portal vein Embolization: state-of-the-art technique and options to improve liver hypertrophy. Visc Med 2017;33:419–25. 10.1159/000480034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez DA, Sampath S, Agulnik M, et al. Surgical management of Retroperitoneal sarcoma. Curr Oncol 2023;30:4618–31. 10.3390/curroncol30050349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong D, Hockley J, Parys S, et al. Current technology venous-venous bypass improves the safety of resection of sarcoma and benign Retroperitoneal tumours involving the inferior vena cava. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2022;64:575–6. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2022.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanthala L, Ray S, Aurobindo Prasad Das S, et al. Recurrent giant Retroperitoneal Liposarcoma: review of literature and a rare case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2021;65:102329. 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimer R, Athanasou N, Gerrand C, et al. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue Sarcomas. Sarcoma 2010;2010:.:317462. 10.1155/2010/317462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the International study group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative Pancreatic Fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017;161:584–91. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacNeill AJ, Gronchi A, Miceli R, et al. Postoperative morbidity after radical resection of primary Retroperitoneal sarcoma: A report from the transatlantic RPS working group. Ann Surg 2018;267:959–64. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tseng WW, Tsao-Wei DD, Callegaro D, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the surgical management of primary Retroperitoneal sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:810–5. 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.01.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi N, Liu S-L, Li Y-T, et al. Splenic preservation versus Splenectomy during distal Pancreatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:365–74. 10.1245/s10434-015-4870-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heil J, Korenblik R, Heid F, et al. Preoperative portal vein or portal and hepatic vein Embolization: DRAGON collaborative group analysis. Br J Surg 2021;108:834–42. 10.1093/bjs/znaa149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blair AB, Reames BN, Singh J, et al. Resection of Retroperitoneal sarcoma en-bloc with inferior vena cava: 20 year outcomes of a single institution. J Surg Oncol 2018;118:127–37. 10.1002/jso.25096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGrath EE, Blades Z, Anderson PB. Chylothorax: Aetiology, diagnosis and therapeutic options. Respiratory Medicine 2010;104:1–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillay TG, Singh B. A review of traumatic Chylothorax. Injury 2016;47:545–50. 10.1016/j.injury.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalret du Rieu M, Mabrut J-Y. Management of postoperative Chylothorax. Journal of Visceral Surgery 2011;148:e346–52. 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liou DZ, Warren H, Maher DP, et al. Midodrine: a novel therapeutic for refractory Chylothorax. Chest 2013;144:1055–7. 10.1378/chest.12-3081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]