Abstract

Background

The cancer stem cell theory proposes that tumor formation in vivo is driven only by specific tumor-initiating cells having stemness; however, clinical trials conducted to test drugs that target the tumor stemness provided unsatisfactory results thus far. Recent studies showed clear involvement of immunity in tumors; however, the requirements of tumor-initiation followed by stable growth in immunocompetent individuals remain largely unknown.

Methods

To clarify this, we used two similarly induced glioblastoma lines, 8B and 9G. They were both established by overexpression of an oncogenic H-RasL61 in p53-deficient neural stem cells. In immunocompromised animals in an orthotopic transplantation model using 1000 cells, both show tumor-forming potential. On the other hand, although in immunocompetent animals, 8B shows similar tumor-forming potential but that of 9G’s are very poor. This suggests that 8B cells are tumor-initiating cells in immunocompetent animals. Therefore, we hypothesized that the differences in the interaction properties of 8B and 9G with immune cells could be used to identify the factors responsible for its tumor forming potential in immunocompetent animals and performed analysis.

Results

Different from 9G, 8B cells induced senescence-like state of macrophages around tumors. We investigated the senescence-inducing factor of macrophages by 8B cells and found that it was interleukin 6. Such senescence-like macrophages produced Arginase-1, an immunosuppressive molecule known to contribute to T-cell hyporesponsiveness. The senescence-like macrophages highly expressed CD38, a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) glycohydrolase associated with NAD shortage in senescent cells. The addition of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), an NAD precursor, in vitro inhibited to the induction of macrophage senescence-like phenotype and inhibited Arginase-1 expression resulting in retaining T-cell function. Moreover, exogenous in vivo administration of NMN after tumor inoculation inhibited tumor-initiation followed by stable growth in the immunocompetent mouse tumor model.

Conclusions

We identified one of the requirements for tumor-initiating cells in immunocompetent animals. In addition, we have shown that tumor growth can be inhibited by externally administered NMN against macrophage senescence-like state that occurs in the very early stages of tumor-initiating cell development. This therapy targeting the immunosuppressive environment formed by macrophage senescence-like state is expected to be a novel promising cancer therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: immunity, immunocompetence, macrophages, tumor microenvironment

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Tumor-initiating cells, so-called cancer stem cells, defined by marker molecules, may not always form tumor when introduced into immunocompetent animals, highlighting the need to consider the immune system’s role in tumor initiation, however, the requirements to establish “tumor” in immunocompetent animals are still unclear.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study showed that tumor-initiating cells induce the surrounding macrophages into a senescence-like state and that senescence-like macrophages produced immunosuppressive molecules. Moreover, using the metabolic modifier nicotinamide mononucleotide was shown to reduce the generation of senescence-like macrophages, and its administration to mice with transplanted tumors led to a decrease in tumor development.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This finding provides a clue as to why even animals with an immune system might allow the establishment of a “tumor”. A metabolic modifier could offer a novel strategy to curb tumor development by counteracting the generation of these senescence-like macrophages.

Background

Tumor cells in cancerous tissue are heterogeneous. The theory of tumor-initiating cells (or cancer stem cells) may explain an important aspect of the phenotypic and functional heterogeneity among cancer cells in some tumors.1 According to this theory, only specific tumor cells can initiate stable tumor formation in vivo. These cells are less sensitive or more resistant to anticancer drugs2 and have repopulating potential.3 4 Therefore, they are thought to be responsible for relapse in many patients.2 Thus, targeting these tumor-initiating cells is an important therapeutic strategy against cancer.5 6 Many types of tumor-initiating cells, defined by their surface markers or selective gene expression, have been identified.7 8 Several reports suggested that Stat3 contributes to self-renewal of the cells as well as tumorigenicity, indicating that Stat3 expression is correlated with the tumor-initiating capacity in some tumor types.9–11 Therefore, targeting Stat3 was assumed to be a promising therapeutic strategy. However, no improved overall survival was achieved when targeting Stat3 in phase III clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01830621 (or results still have to be reported: NCT02178956, NCT02753127, and NCT02993731)).

Although tumor-initiating cell identification has most often been performed in immunodeficient animals, the current general concept is that immune cells are one of the most important components in tumor tissue and suggests that they affect the outcome of tumor treatment.12 13 The assumption can thus also be made that the host immune system would influence tumor-initiation. Quintana et al 14 have reported that a detectable frequency of tumor cells manifests efficiently depending on the host’s increased level of immunocompromise. Therefore, a tumor formation can be initiated only from tumor cells that are resistant to the attack of host immune systems, and such tumor cells are perceived as tumor-initiating cells. According to these notions, the character of tumor-initiating cells is substantially influenced by the host immune system. In contrast to immunocompromised mice frequently used as models in tumor-initiation research, normal individuals have a good functioning immune system. This may be the reason for failure of clinical studies targeting tumor-initiating cells. In other words, the tumor-initiating cells identified in immunodeficient mice and their mechanisms are often not applicable to immunocompetent individuals. Therefore, to understand tumor biology and develop a novel therapy, it is very important to identify the features of tumor cells which can initiate and form a tumor in healthy individuals and to clarify the mechanism(s) that support such tumor cells’ survival.

Although there are various definitions of tumor-forming cell classes and types, in this study, we investigated the requirements for “tumor-initiating cells” that can stably form tumor mass in immunocompetent conditions.

Methods

Cells and cell culture

Induced glioblastoma cell lines were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in glioma media as previously described.15 Knockout of the interleukin (IL)-6 gene in 8B cells was performed using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, Maryland, USA) (CAT#: KN308293). The extent of reduction of IL-6 in the supernatant was analyzed using Legendplex with an FC500 instrument (Beckman Coulter, Brea, California, USA).

Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice, female BALB/c, and male BALB/cnu/nu mice (nude mice) were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). NOD/ShiJic-scid mice (NOD/SCID mice) were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan). All animal procedures were approved by the Hokkaido University Animal Care Committee.

In vivo tumor-initiating capacity analysis

Tumor cells (1,000 cells) in 3 µL saline were transplanted into the anesthetized mouse brain using a Hamilton syringe through a skull hole formed by drilling. The cells were injected into the mouse brain over a period of 30 s; the syringe was left in place for another 30 s. Mouse overall survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. The humane endpoint for this experiment is as follows; stipulating that if animals displayed difficulty in feeding or drinking, signs of distress (such as abnormal posture), prolonged visible abnormalities without signs of recovery (such as diarrhea), a rapid weight loss of more than 20% within a few days, they are humanely euthanized by cervical dislocation. For the purpose of our experimental data, these instances are considered as death. Multiple testing corrections were carried out using the Bonferroni method. The p values<0.05/6=0.0083 (Bonferroni correction) was considered as statistically significant. NS represents non-significant.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Brain samples were embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, California, USA). Thick sections of 5 µm were used. For combined staining of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) and H&E, SA-β-Gal staining16 performed at first, then the sections were stained with H&E. For combined staining of SPiDR-βGal and F4/80, staining of SPiDR-βGal was performed at the same time as staining of the secondary antibody. For immunohistochemical analysis, the sections were stained with primary antibody and then treated with an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa488/Alexa555/Alexa647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The antibodies used were as follows: anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-F4/80 (BM8), and anti-CD38 (90). These primary antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, California, USA). The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD3ζ (H146-968) monoclonal antibody was purchased from Abcam (San Francisco, California, USA). Nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylidole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). For multiple immunofluorescent staining, the Opal 4-color fluorescent IHC kit (PerkinElmer) was used.

Conditioned medium culture experiment

Glioblastoma cells (8×106 cells) were cultured in 10 mL glioblastoma medium. After 4 days of culture, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. The culture supernatant containing 20% (v/v) fresh glioma medium was used as a conditioned medium. F4/80+ cells were magnetically sorted using the MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR), M0, M1, or M2 macrophages (Mφs) were prepared from splenic F4/80+ cells as previously described.17

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed using an FC500 or BD FACSCelesta (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA); data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, Oregon, USA). Anti-mouse CD3 (17A2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53–6.7), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), F4/80 (BM8), and Ly6g (1A8) were used; corresponding isotype controls were purchased from BioLegend. For analysis, live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter as well as lack of DAPI or propidium iodide uptake. All antibodies were used at 1:100 dilutions.

Cell proliferation assay

Whole splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were stained with 5-(and −6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) and then co-cultured with 8B or 9G for 4 days. To identify the proliferation of various immune cell lineages, we stained the resulting cells with various immune cells markers; CFSE reduction in each immune cell was flow cytometrically measured. For the Ki-67 assay, total splenic cells were co-cultured with 8B or 9G for 4 days. All cells were harvested and subsequently stained with antibodies specific for CD11b, F4/80, CD3, and B220 on the cell surface. Following the surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the FoxP3 Staining kit. Intracellular staining was then performed for Ki-67, which was subsequently quantified using flow cytometry.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay

Cells or tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min; then, 0.5 mg/mL of X-Gal in 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 2 mM MgCl2 solution was added. The cells were incubated at 37℃ for 16 hours. After incubation, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and evaluated under a microscope. In the combination of immunofluorescence staining and SA-β-Gal assay, a SPiDER-βGal kit (Dojindo) was used. SPiDER-βGal positive or F4/80 positive areas as well as their merged areas were calculated using Image J software. Ten independent regions were analyzed, and the means were compared using the unpaired Student’s t-test.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated using Tripure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Reverse transcription was carried out using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (Toyobo, Shizuoka, Japan). qPCR analysis was performed using a KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, Massachusetts, USA) and Step One Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). Primer sequences information will be provided on request.

Morphological analysis of Mφs

For smear preparations, Cytospin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was used; Diff-Quik (Sysmex Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) was used for staining. Specimens were observed via optical microscopy.

Cytokine array

For cytokine array analysis, 8×106 glioblastoma cells were cultured in 10 mL glioblastoma medium. After 4 days of culture, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. The supernatants were analyzed by Legendplex (BioLegend) using an FC500 instrument.

Identification of cytokine(s) secreted by 8B that induce Mφs into a senescence-like state

Splenocytes were cultured in media containing 8B-secreting cytokines. We used a glioma medium, which is the same as 8B or 9G culture medium. To ensure Mφs survival, macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) (5 ng/mL) and IL-34 (5 ng/mL) were added to the glioma medium (base-medium). To identify the factor(s) responsible for Mφs’ senescence, we prepared base-medium containing major factors secreted by 8B, including Ccl2 (20 ng/mL), Cxcl1 (5 ng/mL), Cxcl10 (5 ng/mL), Ccl5 (5 ng/mL), and IL-6 (1 ng/mL) (all factors) All cytokines were purchased from BioLegend. We then analyzed the effect of removing individual factors on the induction of senescent Mφs. The concentration of cytokines/chemokines was determined by cytokine array. The generated Mφs were analyzed by the SA-β-Gal assay.

Effect of nicotinamide mononucleotide on inhibiting senescent Mφ induction by 8B supernatant

Magnetic-sorted splenic F4/80+ cells were cultured with the 8B supernatant for 14 days. During culture, 1 mM nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) or saline was added three times per week; then, an SA-β-Gal assay was performed.

Effect of NMN on inhibition of Arginase-1 expression

Whole splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were cultured with the 8B supernatant for 7 days. During culture, 1 mM ΝΜΝ or saline were added on days 0, 1, 3, and 6. On day 7, resulting cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD11b antibody. After washing twice, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilizing the cells using Intracellular Staining Permeabilization Wash Buffer (BioLegend), they were stained with anti-Arginase 1 monoclonal antibody (clone A1exF5, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were analyzed with BD FACSCelesta (BD Biosciences); data were analyzed with FlowJo software.

Analysis of Mφ’s immune activating capacity

Whole splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were cultured in M-CSF (20 ng/mL) or in 8B conditioned medium as described above with 1 mM of NMN or saline for 7 days. NMN or saline was added to the culture at days 1, 3, and 6. Resulting adherent macrophages were used. T cells were collected from the spleens of BALB/c mice by magnetic cell sorting using anti-Thy1.2 MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Collected BALB/c T cells were labeled with CFSE and then co-cultured with collected macrophages (responder/stimulator ratio=2) for 4 days. T-cell proliferation was evaluated by measuring the reduction in CFSE fluorescence by flow cytometry.

Effect of NMN on 8B-transplanted mice survival

C57BL/6 mice were transplanted with 1,000 8B cells in the brain. The mice received 10 mg NMN or saline by intraperitoneal injection three times per week. The survival time of the mice was determined.

Effect of NMN on tumor-initiation and mice survival in CT26-transplanted animals

Syngeneic immunocompetent BALB/c mice were subcutaneously injected with 5×104 CT26 cells. The mice received 10 mg NMN or saline by intraperitoneal injection three times per week. Tumor initiation was evaluated using ocular inspection and palpation. Tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: ((short diameter)2 × (long diameter))/2

Statistics

JMP software (JMP V.16.0.0, SAS Institute) was used for statistical analysis. Data represents mean±SEM. The Student’s t-test (unpaired, two-tailed) or Tukey’s honest significant difference test was used to test for statistically significant differences. Mouse survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival curves with the log-rank test. When more than three experimental groups were performed, the results of the analysis were adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Results

Host immunodeficiency level does not affect 8B tumor formation, whereas 9G tumor formation is affected

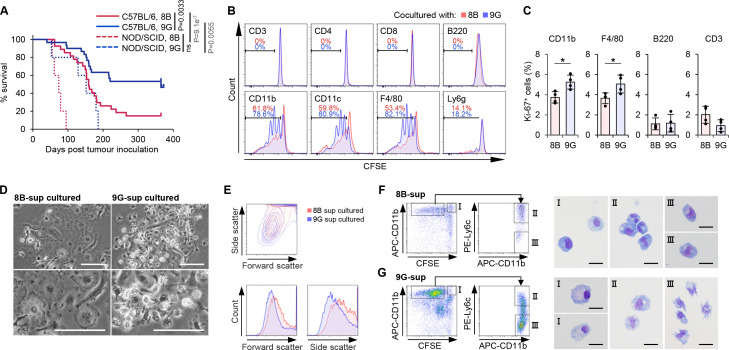

To analyze the requirement for tumor initiation followed by stable growth in immunocompetent individuals, we used the mouse inducible glioblastoma cell lines 8B and 9G,15 which were previously established by overexpression of an oncogenic H-RasL61 in p53-deficient neural stem cells on the C57BL/6 background. As Hide et al 15 previously described, 8B and 9G lines showed similar growth profiles in vitro (Hide et al 15 and online supplemental figure 1A). However, these two lines showed a different phenotype when the cells were inoculated into nude mouse brains; 8B cells stably grew in the inoculated mouse brain and eventually killed the mice, but 9G cells did not stably grow in the brain and all mice survived during the observation period.15 Hide et al had concluded the difference in tumorigenicity between 8B and 9G was tumor-cell-intrinsic. However, we wondered whether this difference in tumorigenicity of both cell lines was not only due to cell-intrinsic properties but also to active immunity. To address this, we further performed experiments using C57BL/6 mice which are immunocompetent and syngeneic to the 8B and 9G. In the C57BL/6 mice, 85% of the animals did not survive inoculation with 8B cells while after injection with 9G cells only ~40% of the mice died (p=0.0033, log-rank test) (figure 1A), which are similar data as previously observed using nude mice.15 Next, we tested tumor-formation of 8B and 9G cells in severe immunodeficient NOD/SCID mice that have a deficiency in T and B cells and reduced macrophage (Mφ) and natural killer (NK) cell activity. Interestingly, all the NOD/SCID mice died not only after 8B tumor cell inoculation but also due to 9G cell tumor formation, although at a slower pace as it took nearly double the time for all mice to be dead (NS; p≥0.0083 (ie, 0.05/6), Bonferroni correction, log-rank test) (figure 1A). These results suggested that the tumor-initiation and following stable growth were regulated at least partly by host immunity. Similar to the observation by Quintana et al,14 the tumor forming capacity of 8B and 9G cells was significantly influenced by immune deficiency at the host level.

Figure 1.

8B and 9G glioblastoma cells differently affected macrophages (Mφs). (A) One thousand 8B or 9G cells were transplanted into C57BL/6 mouse brain (8B (red solid line) n=30, 9G (blue solid line) n=27) or NOD/SCID mouse brain (8B (red dotted line) n=5, 9G (blue dotted line) n=5); then, mouse survival was observed. Statistical analyses were performed using the log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. The p values<0.05/6=0.0083 (Bonferroni correction) were considered as statistically significant. NS, not significant. (B) Proliferation of immune cells in co-culture with 8B or 9G cells. Whole splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were stained with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and then co-cultured with 8B or 9G for 5 days. The resulting cells were stained with the individual immune cell marker indicated in the plots; CFSE reduction in each immune cell was flow cytometrically measured. The proliferation immune cell in 8B-co-cultured cells is shown in red histograms; 9G-co-cultured cells are shown in blue histograms. The percentage of proliferated immune cell in 8B-co-cultured cells is shown in red numbers; corresponding result of 9G-co-cultured cells are shown in blue numbers. (C) 8B and 9G cells were co-cultured with whole splenic cells for 4 days. The percentage of Ki67-positive cells among CD11b, F4/80, B220, and CD3 positive cells was determined by flow cytometry analysis. The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the Ki-67 positive percentage in each sample. *p<0.05, Student’s t-test. (D) Phase contrast images of generated Mφs by co-culture of splenic F4/80+ cells and 8B or 9G supernatant. Bars; 50 µm. (E) Whole splenocytes were cultured in 8B supernatant or 9G supernatant for 11 days. Generated cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Forward scatter and side scatter of generated CD11b+ cells are shown. Red lines show 8B-cultured cells; blue lines show 9G-cultured cells. (F and G) Morphological analysis of generated Mφs that proliferated in response to 8B (F) or 9G (G) supernatants. CFSE-labeled splenocytes were co-cultured with 8B or 9G for 4 days. Quiescent or proliferated CD11b+ cells were sorted based on CFSE fluorescence reduction. Proliferated CD11b+ cells were further subdivided into Ly6c-positive or Ly6c-negative fractions. Each fractionalized cell type was stained using a Diff-quick stain. Bars; 10 µm.

jitc-2023-006677supp001.pdf (6.4MB, pdf)

Although CD133 is a well-known marker of glioblastoma-initiating cells,7 18 its expression was detected neither on 8B nor 9G (online supplemental figure 2).

Mφs have overwhelmingly infiltrated the 8B-tumor and 9G-tumor microenvironment

Tumor cells arise from normal cells whose genome has been genetically/epigenetically altered by various factors, such as mutagens or radiation, and are characterized by their ability to multiply indefinitely. Whether such de novo tumor cells eventually lead to stable tumor formation in an individual may be influenced by immunological factors in that individual. We therefore analyzed why potential tumor-initiating cells such as 8B cells stably form tumors in immunocompetent individuals, but not 9G cells, focusing on differences in the interaction of 8B and 9G with immune cells.

To analyze what interaction between potential tumor initiating/forming cells and immune cells in the early period of tumor stable formation, we injected only 1,000 8B or 9G glioblastoma cells orthotopically as a potentially tumor-initiating population into syngeneic immunocompetent animals. We analyzed what kind of immune cells infiltrated the tumor area. Immunohistochemical analysis showed a remarkable infiltration of CD11b+, F4/80+ cells, a small population of CD11c+ cells; as well as a small number of CD3+ T cells and several CD19+ cells or Ly6g+ cells were observed in both 8B and 9G tumor tissues (online supplemental figure 3). This result in the glioblastoma model suggests that immune cell infiltration into the tumor occurs and interaction is likely.

In these glioma tissues, CD11b+ cells were overwhelmingly infiltrated. In the brain, not only macrophages but also microglia are known as CD11b expressing cells,19 so we questioned whether microglia had infiltrated into the glioblastoma tissues. To elucidate this, we stained the tumor tissue with the microglia-specific P2RY12 antibody20 21 to distinguish microglia from peripherally infiltrating Mφs. Co-staining using P2RY12 and F4/80 antibodies indicated that F4/80+ Mφs, rather than P2RY12+ microglia, selectively infiltrated into the glioblastoma tissue (online supplemental figure 4A,B). Therefore, we hereafter focused on peripherally infiltrating Mφs rather than microglia for further in vitro experiments.

Mφ depletion prolong survival of 8B inoculated mouse

To define the importance of Mφs in tumor initiation followed by stable growth in immunocompetent mice, we depleted Mφs in vivo. In mouse glioblastomas, the timing of tumor initiation and stable growth itself is difficult to monitor and was therefore assessed by mouse death.

We observed survival/death of 8B-transplanted mice for a long enough period to be able to evaluate the Mφ contribution in tumor-initiation followed by stable growth: in mice orthotopically implanted with 8B, the time to final death was 266 days (N=30) (figure 1A). Therefore, day 365 was set as a sufficient period to observe the final survival/death of mice transplanted with 8B, and the contribution of Mφ in tumor development was assessed with the mice alive or dead at 365 days.

Since the F4/80 antibody do not deplete F4/80+ cells in vivo, we instead administered an anti-CD11b antibody (M1/70 proven for CD11b+ cells depletion,22 as the majority of F4/80+ cells are CD11b positive (data not shown). Following the administration of the CD11b antibody, the CD11b/F480 positive macrophages (Mφ) in the tumor area were almost entirely depleted (online supplemental figure 5). We further used the RB6-8C5 (anti-Gr-1) antibody23 which depletes other types of myeloid lineage cells, mainly granulocytes, and rat IgG as experimental controls. In the Mφ-depleted group (anti-CD11b group), the ratio of live mice tended to be higher, although not significantly so, than in the control IgG group (χ2 test (Pearson), χ2 (1) =4.286, p=0.0384) (The p values<0.05/3=0.0167 (Bonferroni correction) was considered as statistically significant) (online supplemental figure 6A,B), suggesting that the role of Mφs was important during the tumor-initiation and following growth.

8B cells made resistant to macrophage proliferation

To analyze whether tumor cells regulate the activity of immune cells, we performed a co-culture experiment of tumor cells and spleen cells. Splenocytes include various kinds of immune cells, including macrophages. In the analysis, Mφs depicted by F4/80+ or CD11b+ efficiently proliferated in the 9G co-culture, although their proliferation was less in the 8B co-culture compared with the 9G co-culture (figure 1B,C). Additionally, in brain tumor tissues, proliferation of CD11b was less in 8B tumors compared with 9G (online supplemental figure 7).

The reduced proliferation was also observed when tumor supernatant was used instead of tumor cells (data not shown). These results suggest that one or more soluble factor(s) secreted by these tumor cells affect Mφ proliferation. After 14 days culturing F4/80+ cells with 8B or 9G tumor cell supernatant (8B-Mφ or 9G-Mφ, respectively), the morphology of the resulting Mφs showed clear differences. A large proportion of 8B-Mφs showed a flattened and enlarged appearance compared with the 9G-Mφs (figure 1D). This difference in cell size was also observed by flow cytometry (figure 1E).

We also performed morphological analysis of the Mφs after splenocytes were cultured with the respective tumor supernatants. The Mφs that did not proliferate (figure 1F,G, gate I) and those that did proliferate and expressed Ly6c (figure 1F,G, gate II) appeared round-shape, just like the senescent cells in both the 8B-sup and 9G-sup cultures. Interestingly, the CFSE-reduced, that is, proliferated, Ly6c-negative Mφ populations of 9G-sup cultures (figure 1G, gate III) clearly had pseudopodia, suggesting that these Mφ were not in the senescent state. On the other hand, the corresponding Mφ population in 8B-sup cultures showed a round shape (figure 1F, gate III), suggesting that they may have entered the senescence-like state after proliferation. These morphological observations indicate that some fractions of 9G-Mφs were in a non-senescence-like state, but most fractions of 8B-Mφs were in a senescence-like state.

8B induced Mφs into a senescence-like state

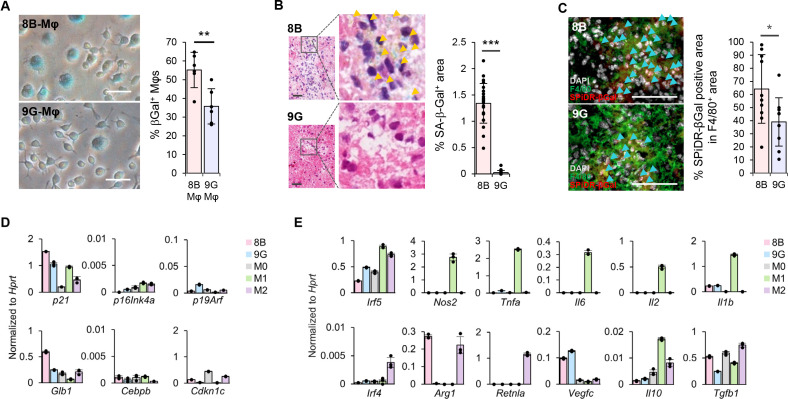

These observations suggested that the appearance of Mφs induced by 8B tumors was similar to that of cells in a senescence-like state. Therefore, we explored whether the Mφs were in such a state using an SA-β-Gal assay. Flattened and enlarged Mφs showed β-galactosidase activity. The proportion of β-galactosidase-positive Mφs was about 1.6-times larger in 8B-Mφs than in 9G-Mφs (figure 2A). Additionally, we performed SA-β-Gal staining in brain tumors that were established after injection of 8B and 9G cells. Positive β-gal activity was observed around the tumor region in the 8B-transplanted brain, whereas no significant positive staining was detected in the 9G-transplanted brain (figure 2B). Most of the cells showing SA-β-gal activity (senescent cells) in the 8B tumor were, although not all, F4/80 positive (online supplemental figure 8). The proportion of the SA-β-Gal positive area within the F4/80+ population was approximately 1.8-fold higher in 8B than in 9G tumors (figure 2C). Subsequently, we analyzed the expression of p16, p21, and γH2AX, which are marker molecules of senescent cells. In the 8B tumor tissues, although not in all, some SPiDR-βGal positive macrophages were positive for these senescence cell markers. Interestingly, in the 9G tumor tissues, almost no SPiDR-βGal positive macrophages co-expressed these senescence marker molecules (online supplemental figure 9). Furthermore, we analyzed the series of cellular senescence-related gene expression in Mφs. The analysis revealed that 8B-Mφs highly expressed p21 and Glb1 (figure 2D) compared with 9G-Mφs among six tested genes which are known to correlate with cellular senescence.24

Figure 2.

8B tumor cells induced senescence-like macrophages (Mφ). (A) Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) assay was performed with generated Mφs in figure 1C. Mφs with flattened and hypertrophic round morphology, that is, senescent cells, are stained blue. SA-β-Gal positive cells (at least 550) in six different views were counted; the proportion of positive cells was calculated. The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the SA-β-Gal % in each sample. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. (B) SA-β-Gal staining of the 8B or the 9G tumor-transplanted brain. Orange arrow heads indicate SA-β-Gal positive cells. From the photographs of each tumor, tumor regions were identified for 8B (23 sites) and 9G (21 sites), and the area of the SA-β-Gal positive region was measured. The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the percentage of SA-β-Gal area in each sample. ***p<0.001, Student’s t-test. Bars: 20 µm. (C) SPiDR-βGal staining combined with F4/80 was applied on brain tissue 7 days after mice were inoculated with 1,000 cells of 8B or 9G. Sky-blue arrowheads indicate SPiDR-βGal staining positive cells. Percentages of SPiDR-βGal positive area in the F4/80+ area in 10 different views were calculated. The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the SPiDR-βGal positive area in the F4/80+ area in each sample. *p<0.05, Student’s t-test. Bars: 100 µm. (D) Splenic F4/80+ cells were cultured with 8B supernatant (pink) or 9G supernatant (sky blue). M0- (light gray), M1- (green), and M2- (purple) Mφs were also induced from splenic F4/80+ Mφs as described by Riquelme et al.17 Gene expression related to cellular senescence in Mφs was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR). The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the relative value normalized to Hprt of each sample. (E) Splenic F4/80+ cells were cultured with 8B- (pink) or 9G- (sky blue) supernatant for 7 days. M0- (right gray), M1- (green), and M2- (purple) Mφs were also induced from splenic F4/80+ Mφs as described by Riquelme et al.17 Gene expression related to the Mφ M1/M2 classification was analyzed by RT-qPCR. The bars indicate the mean (± SD). Each dot represents the relative value normalized to Hprt of each sample.

Historically, many classifications of Mφs have been proposed,25 the major being M1/M2.26 Tumor-associated Mφs are commonly classified as M2 Mφs.25 27 Although 8B cells with tumor-initiating capacity are expected to induce Mφs with an M2 phenotype, 8B-Mφs did neither express most of the M2-Mφs-related genes such as Irf4 or Retnlα, except for Arg1, nor did 8B-Mφs M1-related genes. Furthermore, 9G-Mφs also do not express the typical gene profile to fit the M1/M2 classification (figure 2E). Thus, these data indicated that 8B-Mφs and 9G-Mφs cannot be classified as M1 or M2 based on their gene expression pattern.

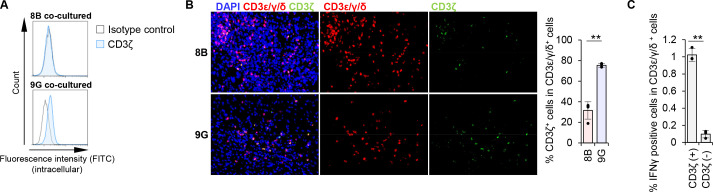

8B tumor infiltrating CD3+ T cells downregulate CD3ζ

Despite the infiltration of CD3+ T cells in the 8B-tumor environment in immunocompetent mice (online supplemental figure 3), tumor growth was persistent (figure 1A), suggesting suppression of T-cell activity in the tumor tissue. Arginase-1 is known to be a strong immunosuppressive molecule that downregulates the expression of CD3ζ, a key intracellular molecule in T-cell signaling, and inducing hyporesponsiveness of these cells.28 We observed an expression of Arg1 in 8B-Mφs but not in 9G-Mφs (figure 2E). When we analyzed CD3ζ expression in T cells from 8B and whole splenocyte co-cultures, including T cells and macrophages, 17A2 antibody staining positive CD3ε/γ/δ+ T cells, that is, surface CD3 positive T cells lost their CD3ζ expression. In contrast, surface CD3+ T cells retained CD3ζ expression in the 9G co-culture (figure 3A). In vivo analysis revealed that CD3ζ expression was observed in ~75% of surface CD3+ T cells in 9G tumors, but only in ~30% of surface CD3+ cells in 8B-tumor tissue (figure 3B). To further understand the activity of tumor-specific T cells, we analyzed T cells harvested from 8B tumor-immunized C57BL/6 mice. As expected, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production was approximately 10-fold lower in CD3ζ-negative T cells compared with CD3ζ-positive T cells (figure 3C). Thus, although T cells infiltrated heavily into the 8B tumor, most of these T cells lost their CD3ζ expression and became dysfunctional. It is therefore suggested that 8B tumors induce dysfunction of infiltrating T cells by downregulating their CD3ζ expression and that resulted in the development of tumors in immunocompetent mice.

Figure 3.

8B macrophage (Mφ) downregulated CD3ζ expression in T cells. (A) Whole splenocytes were co-cultured with 8B or 9G cells for 7 days. Intracellular CD3ζ expression in CD3+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Blue lines indicate CD3ζ staining; black lines indicate isotype control staining. (B) 8B or 9G cells were transplanted into the brain of C57BL/6 mice. after 28 days, the mouse brains were harvested. CD3ζ expression in CD3ε/γ/δ positive cells (it means whole CD3 positive T cells, here) in the tumor region was analyzed by fluorescence immunohistochemistry. The proportion of CD3ζ+ cells in CD3ε/γ/δ+ cells was calculated based on cell number, and the averages and the SD were calculated based on the results of four independent views. The bars indicate mean (±SD) of % CD3ζ+ cells in CD3ε/γ/δ+ cells. Each dot represents the % of CD3ζ+ cells in CD3ε/γ/δ+ cells in each sample. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. (C) C57BL/6 mice were immunized with irradiated 8B cells once per week for 2 weeks. One week after the last immunization, spleens were harvested. Whole splenocytes were co-cultured with intact tumor cells for 4 days; then, T cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 5 hours in the presence of Golgistop reagent; intracellular interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) expression was measured by flow cytometry. The proportion of IFN-γ+ cells among CD3ζ+ or CD3ζ− cells in the CD3ε/γ/δ+ population is shown in a bar graph. Error bars indicate SD. Each dot represents the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells among CD3ζ+ or CD3ζ− cells in the CD3ε/γ/δ+ population in each sample. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test.

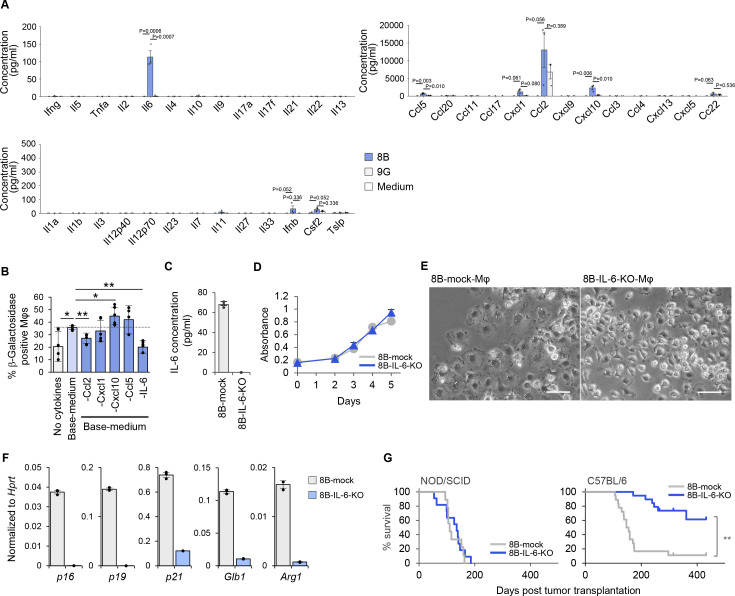

8B-derived IL-6 induce Mφs into a senescence-like state

Next, we focused on the unknown factor(s) that induced the senescence-like phenotype of Mφs. We analyzed the tumor culture supernatant by cytokine/chemokine array and found IL-6, Ccl5, Cxcl1, and Cxcl10 were selectively secreted by 8B cells, where Ccl2 was secreted at a 2× higher amounts (figure 4A). Notably, some of these factors, such as IL-6 and Cxcl1, are known to be senescence-related cytokines/chemokines.29 30 To identify which of these cytokine(s) is/are important for inducing the senescence-like state in Mφs, we cultured splenocytes in the presence of the cytokines secreted by 8B or after withdrawal of each individual cytokine/chemokine from the five candidates (figure 4B). Accelerated senescence induction in Mφs was observed in the presence of the five cytokines compared with in their absence. After withdrawal of either Ccl2 or IL-6, the numbers of β-galactosidase-positive Mφs were reduced. Notably, SA-β-Gal-positive Mφs were reduced to the same level as in the negative control by withdrawing IL-6. This result, together with the observation that 9G-sup also contained Ccl2, suggests that IL-6 is the responsible factor for inducing Mφs into the senescence-like state.

Figure 4.

Interleukin (IL)-6 secretion by glioblastoma cells defined the tumor-initiating capacity in immunocompetent animals. (A) Cytokine secretion in 8B and 9G cells and medium was analyzed by cytokine array. Each dot represents the cytokine concentration by three independent experiments. (B) Identification of the responsible cytokine(s) secreted by 8B that induce macrophages (Mφs) into a senescence-like state. Splenocytes were cultured in medium containing recombinant cytokines corresponding to the types of cytokines secreted by 8B identified in A. Glioma medium as used for 8B or 9G cultures was used to culture splenocytes. To support Mφs survival, macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and IL-34 were added to the glioma medium (base-medium). To determine the factors responsible for Mφ senescence, Base-medium containing the major factors secreted by 8B, including Ccl2, Cxcl1, Cxcl10, Ccl5, and IL-6 (all factors) was used. Each factor from a pool of five cytokines were removed from the base-medium and splenocytes were cultured to analyze the requirement of each cytokine in the induction of senescence-like Mφs. The generated Mφs were analyzed by SA-β-Gal assay. SA-β-Gal-positive cells in six different views were counted; the proportion of positive cells was calculated. The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the percentage of β-Galactosidase positive Mφs in each sample. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Tukey-Kramer honest significant difference test. (C) The IL-6 gene was targeted in 8B cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Gray bar indicates 8B-mock; blue bar indicates 8B-IL-6-knockout (8B-IL-6-KO). (D) Cell proliferation activity was measured daily by the MTT assay. 8B-mock and 8B-IL-6-KO proliferated comparably in vitro. The symbols indicate the mean (±SD). Gray circles indicate 8B-mock; navy triangles indicate 8B-IL-6-KO. (E) Impact of 8B derived IL-6 on Mφs induction into a senescence-like state. Four-day culture supernatant of 8B-mock or 8B-IL-6-KO cells was used during splenic-F4/80+ cell culture. After 14 days, generated Mφs were observed by phase-contrast microscopy. Bars; 50 µm. (F) Gene expression of generated Mφs prepared in C was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR). The bars indicate the mean (±SD). Each dot represents the relative value normalized to Hprt of each sample. (G) One thousand 8B-mock or 8B-IL-6-KO cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID (8B-mock (gray) n=9, 8B-IL-6-KO (navy) n=11), or C57BL/6 mouse brain (8B-mock (gray) n=18, 8B-IL-6-KO (blue) n=19), and mouse survival was examined. **p<0.01, log-rank test.

The p38 MAPK signaling pathway is responsible for IL-6 secretion in 8B

Next, we attempted to identify the signaling pathway that induces selective expression of IL-6 in 8B cells. We used the following inhibitors: U0126 (MEK1/2 inhibitor), LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor), BAY117082 (NFκB inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), and PD0325901 (MEK1/2 inhibitor). Because BAY117082 was strongly cytotoxic for 8B at low concentrations (even at 1 µM), it was difficult to use it in this assay (online supplemental figure 10A). Although all inhibitors were relatively more toxic for the cells than vehicle alone, IL-6 secretion was maintained by MEK1/2 inhibition by U0126 and PI3K inhibition by LY294002. In contrast, JNK inhibition by SP600125 and MEK1/2 inhibition by PD0325901 strikingly up-regulated IL-6 secretion, whereas p38 inhibition by SB203580 led to decrease of IL-6 secretion (online supplemental figure 10B); thus, p38 MAPK signaling is important for IL-6 secretion in 8B cells.

As described above, both the IL-6 producer 8B and the non-producer 9G originate from the same cell line.15 The cause of their different IL-6 secretion is unclear. Ohsawa et al 31 reported that constitutive activation of Ras and mitochondrial dysfunction in drosophila cells resulted in upd (an ortholog of human/mouse IL-6) secretion and tumor formation in vivo. As 8B and 9G cells both bear constitutive active Ras, we speculated that a difference in their respective mitochondrial dysfunction results in the different IL-6 production. As mitochondrial dysfunction results in the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cells, we compared ROS accumulation in 8B and 9G cells. In the presence of excess amounts of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (5000 µM), ROS levels were detected almost equally in 8B and 9G. In contrast, higher ROS levels were recorded in 8B in the presence of 500 µM NAC or in the absence of NAC (online supplemental figure 10C). Considering that elevated ROS levels induce p38 activation,32 activation of the ROS-p38 axis was suggested to be the possible mechanism of selective IL-6 secretion in 8B in relation to 9G.

8B derived IL-6, a senescence inducible factor of Mφs, is one of the factors responsible for tumorigenesis in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice

Next, we focused on the impact of IL-6 secreted by 8B on senescence induction in Mφs and tumor-forming capacity in vivo. We created 8B-IL-6-knockout cells (8B-IL-6-KO) by CRISPR/Cas9 technology as well as mock transfectants with scrambled guide-RNA transfected 8B cells (8B-mock) (figure 4C). Both cell lines proliferated comparably in vitro (figure 4D). The flattened and enlarged appearance of Mφs was observed when cells were cultured in 8B-mock supernatant culture, whereas Mφs with pseudopodia were observed in the 8B-IL-6-KO supernatant culture (figure 4E). In 8B-IL-6-KO-Mφs, expression of Glb1, p16, p19, p21, and Arg1 was lower than in 8B-mock-Mφs (figure 4F). Thus, Mφs induced by the 8B-IL-6-KO supernatant lost their senescent features, suggesting that IL-6 secreted by 8B cells is indeed the factor responsible for senescence induction in Mφs.

We further analyzed the impact of IL-6 on tumorigenicity (figure 4G). 8B-IL-6-KO cells, as well as 8B-mock cells, exerted tumorigenicity in NOD/SCID mice, and all mice died by 200 days after tumor inoculation. Interestingly, only 8B-mock cells still exerted tumorigenicity in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice, and almost all the mice died in a similar time course as the NOD/SCID mice. In contrast, 8B-IL-6-KO cells showed remarkably reduced tumorigenicity in C57BL/6 mice as about 60% of the mice survived more than 400 days after the inoculation of 8B-IL-6-KO cells. This indicates that tumor cells that were not secreting IL-6 were not capable to forming a tumor in immunocompetent mice, although they could do so in immunodeficient mice. In contrast, IL-6 secretion by tumor cells allowed tumor formation not only in immunodeficient mice but even in immunocompetent mice. Thus, IL-6 secretion by tumor cells defines their capacity of tumor-initiation and following growth in immunocompetent mice in this orthotopic glioblastoma transplantation model.

Senescence-like Mφs induced by 8B express high levels of CD38, and supplementation with its substrate, nicotinamide mononucleotide, suppresses the Mφs go into a senescence-like state

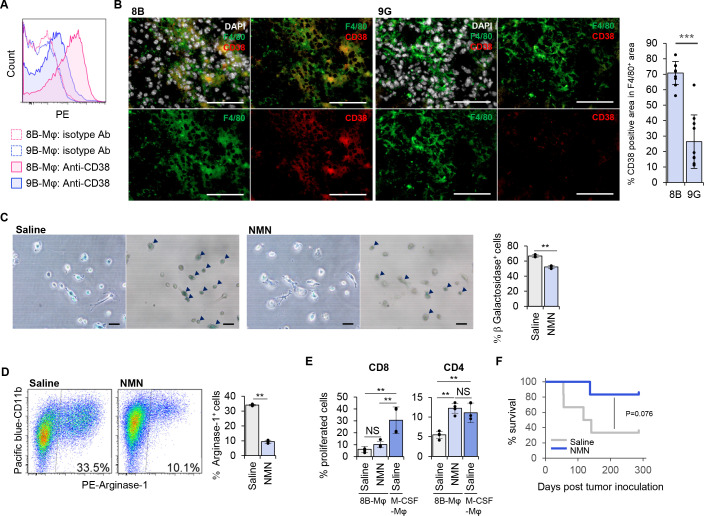

To identify a surface protein that was selectively expressed in senescence-like Mφs, we examined a series of cell surface molecules by flowcytometry. From the experiments, we found that 8B-sup induced senescence-like Mφs expressed CD38 at a higher level compared with 9G-sup induced Mφs (figure 5A and online supplemental figure 11). In addition, more than 70% of F4/80+ cells expressed CD38 in 8B-tumors. In contrast, CD38 expression was detected only on ~25% of the F4/80+ cells in 9G-tumors (figure 5B). CD38 is a membrane-bound multifunctional protein with NADase activity that hydrolyzes NAD+ to nicotinamide and cyclo-ADP-ribose, and its expression is known to increase with age and aging.33 A recent analysis revealed that CD38 is the main enzyme involved in NAD precursor NMN degradation in vivo.34 As the NAD level is reduced with age and is involved in age-related metabolic decline,34 exogenously supplying NAD may prevent senescence. Therefore, we predicted that adding NMN would cancel the senescence phenotype of Mφs and change the tumor microenvironment into an antitumorigenic state. We found that the addition of NMN to the 8B-Mφ culture resulted in Mφs with pseudopodia (figure 5C). Furthermore, the number of SA-β-Gal-positive senescence-like Mφs was reduced after addition of NMN (figure 5C), and Arginase-1 expression in 8B-Mφs cultured in the presence of NMN showed a threefold reduction of Arginase-1 expression compared with the control culture (figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Supplementation of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) inhibited macrophages (Mφs) to go into a senescence-like state, induced expression of an immunosuppressive phenotype and improved survival of immunocompetent mice after lethal inoculation of tumor cells. We screened expressed surface proteins on 8B-sup cultured senescence-like Mφs. (A) 8B-supernatant-cultured or 9G-supernatant-cultured Mφs were stained with anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody (mAb). (B) Mouse brains that were given 8B or 9G tumor cells 7 days earlier were stained with F4/80, CD38, and DAPI. The bar graph shows the proportion of CD38 positive area in the F4/80 positive area. Ten independent regions were analyzed, and the means were compared using unpaired Student’s t-test. ***p<0.001. Each dot represents the percentage of CD38 positive area in F4/80+ area in each sample. Bars; 100 µm. (C) Splenic F4/80+ cells were cultured in 8B-supernatant with/without NMN for 14 days followed by a senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) assay. The left image is a phase-contrast microscopy view, while the right is a bright-field view. Black arrowheads indicate SA-β-Gal+ cells. SA-β-Gal positive and negative cells in 10 different views were counted; the proportion of positive cells was calculated from the total number. The bars indicate the mean (±SD) of percentage SA-β-Gal positive cells from three independent cultures. Each dot represents the percentage β-Galactosidase+ cells in each independent culture. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. (D) Arginase-1 expression of the generated cells in B. The bars indicate the mean (±SD) from three independent flow cytometry analyses. Each dot represents the percentage of Arginase-1+ cells in each independent culture. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. (E) Assessment of NMN treatment on the immune activating capacity of 8B-Mφs. The allogeneic T cell activating capacity of Mφs were evaluated by carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assay. 8B-Mφs were induced with/without NMN. Macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) induced Mφ was used as a positive control. The Mφs and CFSE-labeled Thy1+ T cells from BALB/c were co-cultured for 4 days; then stained with CD4 and CD8, their proliferation was analyzed by CFSE reduction. The bars indicate the mean (±SD) from four independent flow cytometry analyses. Each dot represents the percentage of proliferated cells in each culture. **p<0.01, NS: not significant, Tukey-Kramer honest significant difference test. (F) 8B cells (1×104) were transplanted into the C57BL/6 mouse brain. NMN or saline was inoculated twice per week. Mouse survival was observed. The dark blue line shows NMN-treated mice (n=6); the gray line shows saline-treated mice (n=6). *p<0.05, log-rank test.

Possible existence of senescent Mφ in human glioblastoma tissue

Several gene expression data in human glioblastoma tissues were analyzed using GEPIA, a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses based on the Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression Project (GTEx) data (online supplemental figure 12A,B).35 High expression of CD11B and CD14, those mainly observed in monocytes and macrophage, was identified in human glioblastoma tissues than in normal brain tissues, suggesting a macrophage infiltration in glioblastoma tissue. IL-6, defined as Mφ senescence inducible cytokine in the mouse glioblastoma model (figure 4A–G), and CD38, detected in senescent Mφs (figure 5A), were also detected with higher levels in glioblastoma tissues than in normal tissues. These results suggested a possibility that senescent Mφ were infiltrated in human glioblastoma tissues. Further, pairwise Pearson correlation between CD38 and ARG1 expression in human glioblastoma tissues were analyzed using GEPIA. There was a significant correlation between them, suggesting a possibility of senescent Mφ expressing ARG1.

Exogenous supplementation of NMN converts Mφs from an immunosuppressive to an immunogenic state

We analyzed whether the addition of NMN contributes to the improvement of immune activating capacity of senescence-like macrophages. The addition of NMN to the 8B-Mφ culture resulted in Mφs with pseudopodia, resembling dendrites of dendritic cells (figure 5C). From this result, we speculated NMN treatment might improve the immune activating capacity of 8B-Mφ. Therefore, we further measured the effect of NMN treatment on the immune activating capacity of 8B-Mφs by using an allogeneic T-cell response assay as one of immune activating capacity evaluation (figure 5E). Although CD8+ T cells proliferated efficiently in an M-CSF induced Mφ co-culture, their proliferation ratio was ~3-fold reduced in saline-treated 8B-Mφ co-cultures, to the same extent as the NMN-treated culture. CD4+ T cells showed a ~2-fold reduced proliferation in the saline-treated 8B-Mφ co-culture compared with the M-CSF induced Mφ co-culture. Notably, CD4+ T-cell proliferation in the NMN-treated 8B-Mφ co-culture was restored to the level as was obtained in the M-CSF induced Mφ co-culture. Given that the effector immune cells responsible for tumor immunity are primarily T cells and NK cells, we added an analysis on the impact of senescent Mφ and NMN-treated Mφ on NK cells (online supplemental figure 13). In co-culture with saline-treated 8B-Mφ, the proportion of IFN-γ positive activated NK cells among the total NK cells experienced an approximately 70% reduction compared with co-culture with M-CSF-induced Mφ. Conversely, in co-culture with NMN-treated 8B-Mφ resulted in a twofold increase in the proportion of IFN-γ+ NK cells compared with the co-culture with saline-treated 8B-Mφ. Thus, NMN treatment improves the immune activating capacity of 8B-Mφs.

NMN supplementation therapy prevents tumor initiation in 8B-inoculated immunocompetent mice

Finally, we analyzed the effectiveness of NMN treatment in preventing 8B-tumor initiation using the orthotopic tumor transplantation model in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice (figure 5F). In the saline treated group, ~70% of mice showed tumor initiation and died as a result. In contrast, in the NMN treated group, tumor initiation was observed in only ~20% of mice, and survival was improved compared with that in the saline group (p=0.076, log-rank test).

In the glioblastoma orthotopic transplantation model, it is difficult to precisely determine the date of tumor initiation and formation. To examine the precise timing, we attempted to analyze subcutaneous tumor formation. However, 8B and 9G cells did not form any tumor when subcutaneously inoculated (data not shown). Therefore, we chose CT26 subcutaneous engraftable syngeneic tumor model to analyze the effect of NMN on tumor formation. As the CT26 mouse colorectal cancer cells secrete IL-6,36 Mφ senescence induction via IL-6 in the tumor microenvironment is expected. We therefore injected CT26 cells subcutaneously into syngeneic BALB/c immunocompetent mice and evaluated the effect of NMN treatment on tumor formation. The NMN treatment significantly delayed the tumor initiation (p<0.05, log-rank test) (online supplemental figure 14A) and efficiently inhibited the tumor growth (online supplemental figure 14B). Collectively, these results suggested that NMN treatment suppressed the senescence of Mφs that induces T-cell dysfunction by expressing Arginase-1, and eventually but temporarily, prevented tumor initiation in immunocompetent mice.

Discussion

Our understanding of the requirements and mechanisms allowing tumor-initiating cells to form tumors in immunocompetent individuals remains insufficient. In this study, a series of experiments showed that senescence in Mφs played a pivotal role in tumor-initiation in immunocompetent mice. One of the mechanisms is that tumor cell-derived IL-6 induces senescence of Mφ, which in turn induces T-cell dysfunction through the expression of Arginase-1 by their macrophages, enabling tumor development even in immunocompetent animals. These results suggest that tumor cells that have the capacity to induce macrophage senescence could be authentic tumor-initiating cells in immunocompetent animals.

It is known that cellular senescence affects immune responses, including both stimulation and suppression.37–39 In the radiation-inducing osteosarcoma mouse model, tumor cells go into senescence and express senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, including IL-6. In this model, IL-6 plays an immune-activation role by recruiting NK cells.38 In another model, senescent stromal cells express Ccl2, which plays an immunosuppressive role by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells that inhibit tumor clearance by NK cells.39 In the current study, we propose a new mechanism whereby Mφ-senescence-like phenotypes driven by tumor cell-derived IL-6 induce immunosuppression that eventually leads to tumor initiation in immunocompetent individuals. Moreover, preventing senescence by the exogenous administration of a metabolic substrate suppressed tumor initiation in vivo. This finding clearly indicates that Mφ senescence can contribute to tumor initiation.

8B tumor cells have infinite cell division activity with continuous IL-6 production, leading to immunosuppression. Such cells achieved tumor-initiation cell-autonomously even in immunocompetent individuals. Therefore, we considered that having both features in one cell is one of the requirements for autonomous tumor-initiation by cells in immunocompetent individuals. From another perspective, our results give consideration to the simultaneous existence of infinitely proliferating tumor cells and an immunosuppressive environment that also is a condition that can lead to tumor-initiation in immunocompetent individuals. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are susceptible to colorectal cancer,40 and this may be an example of the concept. Abundant ROS exist in inflammatory environments41 and can cause genetic damage,41 generating cells that divide infinitely. IL-6 is also present in the same environment.42 Thus, the bowel environment of patients with IBD seems to correspond to the tumor-initiation requirement, even if the patient has a healthy (although overactive) immune system. This may explain why patients with IBD are more susceptible to colorectal cancer.

We cannot exclude the possibility of other tumor-initiation mechanisms that may exist depending on the individual organ in immunocompetent individuals; in fact, subcutaneous inoculation of 8B cells (1,000 cells; this number is sufficient for tumor formation in the brain) did not form a tumor mass (data not shown) in the skin.

In this study, we identified the presence of CD38-positive macrophages (8B-Mφ) within the 8B tumor tissue. CD38 is expressed in M1-Mφ.43 Mφs that form a favorable environment for tumor cells are generally known as M2-Mφs, and M1-Mφs are rather known as Mφs that induce antitumor responses. Therefore, if 8B-Mφ were classified as M1-macrophages, it would seem counterintuitive. Based on the gene expression analysis of 8B-Mφ, it is difficult to classify these cells as either M1 or M2 (figure 2E). Rather, as various cellular senescence markers were detected, 8B-Mφ should be referred to as senescence-like Mφs.

As we mentioned above, the contribution of cellular senescence to cancer remains controversial. However, Haston et al 44 recently showed that human premalignant lung tumors contained macrophages expressing senescent markers. Furthermore, they showed that the depletion of senescent macrophages promoted immune surveillance in a KRAS-driven lung cancer model, resulting in a significant reduction in tumor burden and prolonged survival. These results support our findings. Further, we indicated that the addition of a metabolic substrate, NMN, which is reduced during senescence, inhibited the production of the immunosuppressive molecule Arginase-1 in Mφs, improving their T-cell stimulating capacity towards CD4+ T cells and NK cells (figure 5E and online supplemental figure 13). These observations suggested that senescence, at least in Mφ, contributes to tumor development. Consequently, modulating Mφ senescence using NMN, a metabolic modulator, to reactivate the immune system could potentially emerge as a promising avenue for cancer therapy.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that the tumor cells that are secreting IL-6 did allow tumor formation in immunocompetent animals by inducing senescence of macrophages. That means, the tumor cells which have such phenotypes are authentic tumor-initiating cells in immunocompetent animals. Further, in vivo administration of NMN prolonged the tumor-free duration and survival in IL-6 expressing tumor inoculated immunocompetent mice. We speculate that NMN administration would have inhibited Mφ senescence and would have induced immunogenicity of the tumor microenvironment at the moment that a tumor was “just initiated”. This is a time point where only a small number of tumor cells and surrounding Mφs are present at the same location. Thus, for clinical application, NMN administration should be expected to suppress de novo tumor-initiation including metastasis suppression and could be applied after primary tumor resection. Therefore, this newly defined tumor-initiation mechanism in immunocompetent individuals will help to construct a novel strategy for cancer therapy.

jitc-2023-006677supp002.rtf (71.9KB, rtf)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Muhammad Baghdadi and Dr Jim-Min Nam for useful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Ms Nanami Eguchi, Ms Misuho Ito, Mr Rei Kawashima, Ms Chie Kusama, Ms Ayano Yamauchi, and Ms Rei Okabe.

Footnotes

Contributors: HW and K-iS designed the study. HW wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. HW, RO and TM contributed to acquisition of data. HW, RO, TM, TK and K-iS analyzed and interpreted the data and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. WTVG assisted in the preparation and writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. HW is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported in part by research grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan under grant number 26640066, 16K18408 (HW) and 26640099 (K-iS). This work was also supported in part by AMED under grant number 19bm0404028h0002 (K-iS), 19ck0106262h0003 (K-iS), the Kato Memorial Bioscience Foundation (HW), Suhara memorial foundation (HW), The Akiyama life science foundation (HW), Friends of Leukemia Research Fund (HW), The Mitsubishi Foundation (K-iS), Joint Research Program of the Institute for Genetic Medicine (K-iS), the project of junior scientist promotion (K-iS), and the Photo-excitonix Project in Hokkaido University (K-iS).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature 2013;501:328–37. 10.1038/nature12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steinbichler TB, Dudás J, Skvortsov S, et al. Therapy resistance mediated by cancer stem cells. Semin Cancer Biol 2018;53:156–67. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell 2015;16:225–38. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peitzsch C, Tyutyunnykova A, Pantel K, et al. Cancer stem cells: the root of tumor recurrence and metastases. Semin Cancer Biol 2017;44:10–24. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frank NY, Schatton T, Frank MH. The therapeutic promise of the cancer stem cell concept. J Clin Invest 2010;120:41–50. 10.1172/JCI41004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qiu H, Fang X, Luo Q, et al. Cancer stem cells: a potential target for cancer therapy. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015;72:3411–24. 10.1007/s00018-015-1920-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen K, Huang Y, Chen J. Understanding and targeting cancer stem cells: therapeutic implications and challenges. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013;34:732–40. 10.1038/aps.2013.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tirino V, Desiderio V, Paino F, et al. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors: an overview and new approaches for their isolation and characterization. FASEB J 2013;27:13–24. 10.1096/fj.12-218222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sherry MM, Reeves A, Wu JLK, et al. Stat3 is required for proliferation and maintenance of Multipotency in glioblastoma stem cells. Stem Cells 2009;27:2383–92. 10.1002/stem.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee TKW, Castilho A, Cheung VCH, et al. CD24(+) liver tumor-initiating cells drive self-renewal and tumor initiation through Stat3-mediated Nanog regulation. Cell Stem Cell 2011;9:50–63. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin L, Fuchs J, Li CL, et al. Stat3 signaling pathway is necessary for cell survival and tumorsphere forming capacity in Aldh(+)/Cd133(+) stem cell-like human colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011;416:246–51. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol 2002;3:991–8. 10.1038/ni1102-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (time) for effective therapy. Nat Med 2018;24:541–50. 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, et al. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature 2008;456:593–8. 10.1038/nature07567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hide T, Takezaki T, Nakatani Y, et al. Sox11 prevents tumorigenesis of glioma-initiating cells by inducing neuronal differentiation. Cancer Res 2009;69:7953–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Debacq-Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J, et al. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-beta Gal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1798–806. 10.1038/nprot.2009.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Riquelme P, Tomiuk S, Kammler A, et al. Ifn-gamma-induced iNOS expression in Mouse regulatory macrophages prolongs allograft survival in fully immunocompetent recipients. Mol Ther 2013;21:409–22. 10.1038/mt.2012.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neuzil J, Stantic M, Zobalova R, et al. Tumour-initiating cells vs. cancer ’stem' cells and Cd133: what’s in the name Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;355:855–9. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galatro TF, Holtman IR, Lerario AM, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of purified human cortical microglia reveals age-associated changes. Nat Neurosci 2017;20:1162–71. 10.1038/nn.4597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lund H, Pieber M, Parsa R, et al. Competitive repopulation of an empty microglial niche yields functionally distinct Subsets of Microglia-like cells. Nat Commun 2018;9:4845. 10.1038/s41467-018-07295-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in Microglia. Nat Neurosci 2014;17:131–43. 10.1038/nn.3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ault KA, Springer TA. Cross-reaction of a rat-anti-Mouse phagocyte-specific Monoclonal antibody (anti-Mac-1) with human monocytes and natural killer cells. J Immunol 1981;126:359–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stoppacciaro A, Melani C, Parenza M, et al. Regression of an established tumor genetically-modified to release granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor requires granulocyte t-cell cooperation and t-cell produced interferon-gamma. J Exp Med 1993;178:151–61. 10.1084/jem.178.1.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burton DGA, Krizhanovsky V. Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014;71:4373–86. 10.1007/s00018-014-1691-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, et al. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol 2002;23:549–55. 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mills CD. Anatomy of a discovery: M1 and M2 macrophages. Front Immunol 2015;6:212. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1670–90. 10.3390/cancers6031670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J, et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits t-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific t-cell responses. Cancer Res 2004;64:5839–49. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kojima H, Inoue T, Kunimoto H, et al. Il-6-Stat3 signaling and premature Senescence. JAKSTAT 2013;2:e25763. 10.4161/jkst.25763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim EK, Moon S, Kim DK, et al. Cxcl1 induces senescence of cancer-associated fibroblasts via autocrine loops in oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 2018;13:e0188847. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ohsawa S, Sato Y, Enomoto M, et al. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through hippo signalling in drosophila. Nature 2012;490:547–51. 10.1038/nature11452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, et al. Reactive oxygen species act through P38 Mapk to limit the LifeSpan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med 2006;12:446–51. 10.1038/nm1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chini EN, Chini CCS, Espindola Netto JM, et al. The pharmacology of Cd38/Nadase: an emerging target in cancer and diseases of aging. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018;39:424–36. 10.1016/j.tips.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Camacho-Pereira J, Tarragó MG, Chini CCS, et al. Cd38 dictates age-related NAD decline and mitochondrial dysfunction through an Sirt3-dependent mechanism. Cell Metab 2016;23:1127–39. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, et al. Gepia: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:W98–102. 10.1093/nar/gkx247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li J, Xu J, Yan X, et al. Targeting Interleukin-6 (Il-6) sensitizes anti-PD-L1 treatment in a colorectal cancer preclinical model. Med Sci Monit 2018;24:5501–8. 10.12659/MSM.907439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Faget DV, Ren Q, Stewart SA. Unmasking senescence: context-dependent effects of Sasp in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2019;19:439–53. 10.1038/s41568-019-0156-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kansara M, Leong HS, Lin DM, et al. Immune response to Rb1-regulated Senescence limits radiation-induced osteosarcoma formation. J Clin Invest 2013;123:5351–60. 10.1172/JCI70559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eggert T, Wolter K, Ji J, et al. Distinct functions of senescence-associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell 2016;30:533–47. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, et al. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer 2001;91:854–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prasad S, Gupta SC, Tyagi AK. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cancer: role of antioxidative nutraceuticals. Cancer Lett 2017;387:95–105. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stevens C, Walz G, Singaram C, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and Interleukin-6 expression in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 1992;37:818–26. 10.1007/BF01300378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jablonski KA, Amici SA, Webb LM, et al. Novel markers to delineate murine M1 and M2 macrophages. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145342. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haston S, Gonzalez-Gualda E, Morsli S, et al. Clearance of senescent macrophages ameliorates tumorigenesis in KRAS-driven lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2023;41:1242–60. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-006677supp001.pdf (6.4MB, pdf)

jitc-2023-006677supp002.rtf (71.9KB, rtf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.