Abstract

Objective:

Previous systematic reviews demonstrated a potentially beneficial effect of probiotics on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). However, these studies are either affected by the inclusion of insufficient trials or by the problem of dependent data across multiple outcomes, and an overall effect size has not been provided. We aimed to determine the effect of probiotics on IBS through a three-level meta-analysis and clarify potential effect moderators.

Methods:

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science, screening for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examine the effect of probiotics on IBS. The primary outcome was the improvement in the severity of global IBS symptoms at the end of treatment. The secondary outcomes were the improvement in abdominal pain and the quality of life. The effect sizes of the probiotics were measured by using the standardized mean difference (SMD) and pooled by a three-level meta-analysis model.

Results:

We included 72 RCTs in the analysis. The meta-analysis showed significantly better overall effect of probiotics than placebo on the global IBS symptoms (SMD −0.55, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.34, P<0.001), abdominal pain (SMD −0.89, 95% CI −1.29 to −0.5, P<0.001) and quality of life (SMD 0.99, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.54, P<0.001), respectively. Moderator analysis found that a treatment duration shorter than 4 weeks was associated with a larger effect size in all the outcomes, and Bacillus probiotics had better improvement on the abdominal pain.

Conclusions:

Probiotics had a short-term effect and a medium effect size on the global IBS symptoms. Treatment duration and types of probiotics affected the effect size of probiotics, and shorter durations and Bacillus probiotics were associated with better treatment effects.

Registration:

Open Science Framework.

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, multi-level meta-analysis, probiotics, systematic review

Introduction

Highlights

Despite the previous reports of several systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining the effect of probiotics for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the general effect size of probiotics on IBS symptoms and the essential effect moderators are unknown.

In this meta-analysis incorporating 72 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), probiotics showed a medium effect size on the improvement of global IBS symptoms (standardized mean difference, −0.55, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.34) compared with placebo.

A treatment duration shorter than 4 weeks and Bacillus probiotics were associated with larger effect sizes.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a disorder of the brain–gut axis characterized by frequent abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and change of bowel habits – constipation or diarrhea. The global prevalence of IBS was 9.2% but varied across different regions; the prevalence was similar in Western countries, which is between 8.6 and 9.5% when the Rome III criteria were adopted and is between 4.5 and 4.7% with Rome IV1, and the prevalence was as high as 21.2% in Japan when the Rome III criteria were adopted2. IBS affects the quality of life substantially to the same degree as inflammatory bowel diseases3. The high prevalence and heavy disease burden urge the development of treatments for patients with IBS.

Owing to the complexity of IBS pathophysiology and the long disease duration, dietary supplements and alternative treatments are supposed to be more appropriate than pharmacological treatments since they are acknowledged to be harmless or with few adverse events. However, dietary supplements, like probiotics, are in the conundrum of ‘no harm, might help’4. Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses were published to examine the effect of probiotics on IBS, and most of them suggested a beneficial effect5–8, but convincing evidence cannot be reached owing to the small sample size, single-center design, and high risk of bias of the included trials. Additionally, the diverse outcome assessments and differential assessment time points hinder a general evaluation of the effect size of the probiotics. The previously published meta-analyses normally selected a specific time point and one of the outcomes to pool, which caused a loss of information – many of the outcomes are correlated and should be included for analysis9. In addition, numerous factors might affect the effect size of probiotics, and previous reviews concluded that specific strains of the probiotics had larger effects than the others7. Other effect moderators like treatment duration and the patient’s characteristics are rarely evaluated. Based on these grounds, we raised two clinically relevant questions – what is the overall effect size of probiotics in the management of IBS, and what are the major effect moderators that significantly affect the size of the probiotic effect?

One problem, not being fully settled in previously published meta-analyses on the topic, is that the effect sizes reported by the included trials might not be independent. For example, the studies conducted in the same region (i.e. European countries) might report similar results, which introduces dependence. A three-level meta-analysis is developed to solve this problem, which treats effect sizes nested within a study as dependent variables and examines the source of heterogeneity within a study and between studies – avoiding the inflation of type I error10. In addition, a three-level meta-analysis can include effect moderators in the model and assess the impact of the moderators on the effect sizes, which gives a better explanation for the effect of an intervention than the conventional meta-analysis. We aimed to assess the overall effect of probiotics on the improvement of IBS symptoms and find out the important effect moderators through the three-level meta-analysis.

Methods

Study overview

We performed a systematic review and multi-level meta-analysis, and this work had been reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)11 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A874, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A875) and AMSTAR (Assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews) Guidelines12 (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A876). The review was registered in Open Science Framework prior to conduction. The meta-analysis used aggregate-level data from published randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Ethical approvals and patient informed consent were acquired in each participating center of the RCTs. The work has been reported.

Literature search and study selection

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science from inception to 12 November 2022, aiming to screen for RCTs that examined the efficacy of probiotics on IBS. Comprehensive search strategies with the combination of MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and keywords were developed for the search in the databases. The search strategies were shown in eTables 1–3 (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A877) We also searched previously published systematic reviews and read the reference lists of the reviews, trying to find out missing RCTs from our literature search. One author (C.-R.X.) performed the literature search, and two authors (L.Y. and X.-Y.X.) independently screened the retrieved articles. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed below.

RCTs were included if they (1) recruited participants who aged over 18 years and were diagnosed with IBS or any of its subtypes; (2) tested the effect of probiotics by comparing them with a placebo; (3) measured any of the following outcome: improvement of IBS symptoms, improvement of abdominal pain, or quality of life.

RCTs were excluded if they (1) also recruited other gastrointestinal diseases (e.g. functional dyspepsia, inflammatory bowel diseases); (2) published as letters that had insufficient information to judge the exact type of probiotics and their controls, or insufficient information on the types of outcomes.

Outcome assessments

The primary outcome of this study was the severity of global IBS symptoms, which normally include abdominal pain, discomfort in the abdominal region (i.e. bloating, urgency, indigestion), and changed bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, or diarrhea alternating with constipation). These symptoms could be assessed by asking questions with yes-or-no answers like ‘Are your global IBS symptoms relieved?’ or by adopting scales such as the IBS-SSS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System) scale.

Secondary outcomes included the severity of abdominal pain and the improvement in quality of life. Abdominal pain is one of the most essential symptoms of IBS, and it is usually separately reported. The severity of abdominal pain could be assessed by using binary outcomes indicating whether relief of pain was achieved or by rating scales such VAS (Visual Analog Scale) score. The quality of life in IBS patients is assessed by scales like IBS-QoL (Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life). Our study included all these scales.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (X.-Y.W. and S.-J.F.) independently extracted study data from the included studies. Characteristics of the study design, participants, intervention, controls, and outcomes were separately extracted, and the characteristics were also coded and prepared for moderator analysis, which was described in detail in the statistical analysis section.

Risk of bias assessment

We assessed the risk of bias (RoB) using the revised Cochrane RoB tool (RoB 2.0), in which five domains – bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviation from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in the measurement of an outcome, and bias in the selection of the reported result – were assessed and an overall RoB (low/high RoB or some concerns) was provided for each study. The certainty of the evidence was assessed by using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) approach.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the effect size of probiotics versus placebo by using the standardized mean difference (SMD, also known as Cohen’s d). Based on the assumption that the underlying continuous measurements in each intervention group follow a logistic distribution and that the variability of the outcomes is the same in both the intervention and control groups, the odds ratios (ORs) can be re-expressed as an SMD according to the following simple formula13,14: . The effect size was interpreted as small, medium, and large with the cut-off points of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively15. To ensure the consistency of the direction of outcome measurements, the category outcomes were measured with the ORs of participants with failures of improvement, while continuous outcomes were measured with the change in the severity of the global IBS symptoms or abdominal pain.

We used a three-level random-effects meta-analysis model to pool the effect sizes, estimated the heterogeneity within-study (level 2) and between-study (level 3), and used Cochran’s Q test to evaluate whether the heterogeneity was statistically significant (defined as P<0.05). We compared the traditional two-level meta-analysis with the three-level model by evaluating the AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) of the models and estimated the significance of the difference by the likelihood ratio test – which also used a cut-off point of 0.05. To assess potential publication bias, we generated funnel plots for the three outcomes to perform a visual assessment for asymmetry16.

We further performed moderator analyses to find out which factors substantially affected the effect size by using the meta-regression model. Four groups of factors were analyzed. The first group was study-design-related: countries hosting the studies, types of RCT (single vs. multicenter design), number of study sites, and the total study duration (measured by weeks). The second group was participant-related: age, proportion of females, the proportion of participants who dropped out from the study, duration of disease, and diagnostic criteria. The third group was intervention-related: duration of the intervention (measured by weeks) and the types of probiotics (classified as Bacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, and a combination of differential probiotic strains). The fourth group was outcome-related: the type of data (continuous vs. categorical data) and types of outcome definition (i.e. global IBS symptoms could be further classified as adequate relief of symptoms, any relief of global symptoms, bloating, bowel habit, abdominal discomfort, and defecation urgency). The analysis was performed in the R environment (version 4.2.2) and the metafor package (version 4.2-0).

Results

Trial characteristics

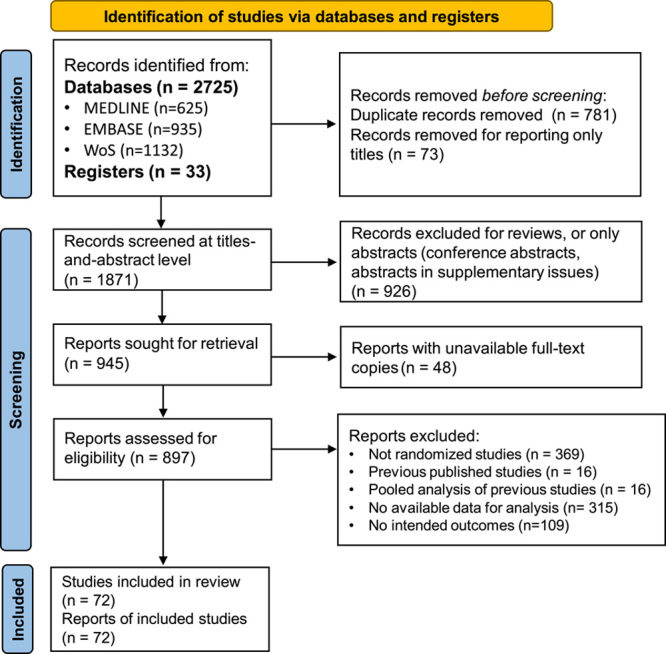

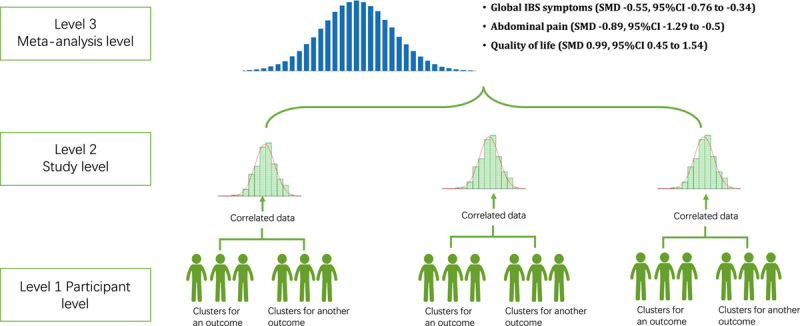

We identified 72 RCTs17–88 after screening for 2725 pieces of articles and included a total of 8581 participants. The process of screening is shown in Figure 1. The included population had a mean age of 41.7 years and a mean proportion of 65.8% of females. Sixty-seven (93.1%) of the included studies adopted the Rome criteria as the diagnostic standard, and 53 (73.6%) of the studies recruited at least two subtypes of IBS. Of the 18 studies that focused on a single subtype, 13 studied diarrhea-predominated IBS. Seventy studies compared probiotics with placebo controls. More detailed information is shown in Table 1. Of the 72 included RCTs, nine were classified with a low risk of bias, two were with a high risk of bias, and 61 with some concerns; the assessment of each domain was presented in eFigure 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A877) The GRADE assessment for all three outcomes showed low certainty of the evidence. The summary of the GRADE table is shown in eTable 4 (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A877). Figure 2 shows the concept of the three-level meta-analysis and the results of the meta-analyses on the three outcomes – the severity of global IBS symptoms, the severity of abdominal pain, and the quality of life assessment.

Figure 1.

The study flowchart. WoS, Web of Science.

Table 1.

Trial characteristics

| Author* | Country, study design | Sample size (%female, mean age) | BMI | Group allocation (I, P)† | Diagnosis; Subtypes | The probiotics and their components‡ | Dose and duration | Control, dosage and duration | The main efficacy outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gade et al.17 | Denmark, RCT, Thirteen centers | 54 (77.8, 34) | NA | 32, 22 | Others; IBS‑D, IBS‑C | Enterococcus; Streptococcus faecium | 4 tablets b.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; 4 tablets b.i.d.; 4 weeks | Improvement in IBS Symptoms |

| Nobaek et al.18 | Sweden, RCT, Single center | 60 (69.2, 48.5) | NA | 25, 27 | Rome criteria; IBS‑D, IBS‑C | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 9843 | 400ml (5 × 107 CFU/ml/drink) q.d.for 4 weeks. | Placebo; 400ml q.d.; 4 weeks. | Significant improvements in the IBS Symptoms |

| Niedzielin et al.19 | Poland, RCT, Single center | 40 (80,43.5) | 23.7 | 20, 20 | Clinical diagnosis; 2.5% IBS-D, 52.5% IBS-C, 45% IBS‑M | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus plantarum 299V | 200ml (5 × 107CFU/ml) | ||

| bid for 4 weeks | Placebo; 200ml bid; 4 weeks | Improvement in Global IBS symptoms | |||||||

| Kim et al.20 | USA, RCT, Single center | 25 (72,42.8) | NA | 12, 13 | Rome II; 100% IBS‑D | Combination; VSL#3 | One packet (containing 225 billion bacteria/packet) b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One packet b.i.d.; 8 weeks | Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms for 50% of weeks |

| Kim et al.22 | USA, RCT, Single center | 48 (93.8,43) | NA | 24, 24 | Rome II; 42 % IBS‑D, 33% IBS‑C, 25% IBS‑M | Combination; VSL#3 | One product b.i.d. (31 patients for 4 weeks and 17 patients for 8 weeks) | Placebo; One product b.i.d. (31patients for 4 weeks and 17 patients for 8 weeks). | Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms for 50% of weeks |

| Kajander et al.21 | Finland, RCT, Single center | 103 (76.5,45.5) | 25.1 | 52, 51 | Rome I and II; 47 .6% IBS‑D, 23.3% IBS-C, 29.1% IBS-M | CombinationLactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Lactobacillus Rhamnosus LC705, Bifidobacterium breve Bb99 and Propionibacterium freudenreichii ssp. | One capsule (8-9 × 109 CFU/capsule) o.d. for 24 weeks | Placebo; one capsule o.d.; 24 weeks | Relief of global symptom score |

| Niv et al.23 | Israel, RCT, Two centers | 54 (66.7,45.7) | NA | 27, 27 | Rome II; 37% IBS‑D, 18.5% IBS-C 44.4% IBS‑M | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 | One product (1 × 108colony-forming units/tablet), q.i,d. for 1week, then tid. | Placebo; One tablet b.i.d; 22 weeks. | Global symptoms score; Adverse events |

| Kim et al.24 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 40 (26.5,39.4) | 23.7 | 20, 20 | Rome II; 70 % IBS‑D, 30% IBS‑M | Combination; Bacillus Subtilis and Streptococcus faecium | One capsule t.i.d.; 4 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule t.i.d.; 4 weeks | Abdominal pain |

| Whorwell et al.25 | UK, RCT, Twenty centers | 362 (100,41.9) | 26.7 | 270, 92 | Rome II; 55.5% IBS-D, 20.7% IBS-C, 23.8% IBS-M, | Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 | (1 × 106 live bacteria/capsule, 1 × 108 live bacteria/capsule, or 1 × 1010 live bacteria/capsule) o.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; One capsule o.d.; 4 weeks | Relief of overall IBS symptoms |

| Guyonnet et al.26 | France, RCT, Thirty-five centers | 274 (74.5,49.3) | NA | 135, 132 | Rome II; 100% IBS‑C | Combination; Fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN1 73010 Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus | One pot containing 125g. (1.25 × 1010 CFU/125g) or (1.2 × 109 CFU/125g) b.i.d. for 6 weeks | Placebo; One pot b.i.d.; 6 weeks | Improvement at least 10% discomfort dimension score |

| Drouault-Holowacz et al.27 | France, RCT, Single center | 106 (76,45.4) | NA | 48, 52 | Rome II; 29% IBS-D, 29% IBS-C, 41% IBS-M, 1% IBS-U | Combination; Bifidobacterium longum LA 101 (29%), Lb.acidophilus LA 102 (29%), Lactobacillus lactis LA 103 (29%), and Streptococcus thermophilus LA 104 (13%) | One sachet q.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo (of identical com-position except for the bacteria); One sachet q.d.; 4 weeks | Satisfactory relief of overall IBS symptoms |

| Enck et al.28 | Germany, RCT, ten centers | 297 (73.5,49.6) | 24.2 | 149, 148 | Clinical criteria; IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M | Combination; Enterococcus faecalis DSM16440 and Escherichia coli DSM17252 | 0.75 ml (3.0-9.0 × 107 CFU/1.5ml) t.i.d. for 1 week, then 1.5 ml t.i.d. for weeks 2 and 3, then 2.25 ml t.i.d. for weeks 3–8 | Placebo (identical in taste and Texture); The same dose; 8 weeks. | Have at least a 50% decrease in global symptom score |

| Kajander et al.29 | Finland, RCT, Single center | 86 (93,48) | 26.2 | 43, 43 | Rome II; 45% IBS-D, 25% IBS-C, 30% IBS-M | Combination; probiotic milk containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103, LGG), Lactobacillus rhamnosus Lc705 (DSM 7061), Propionibacterium freudenreichii ssp. Shermanii JS (DSM 7067) and Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis Bb12 (DSM 15954) | One drink for 1.2 dL (1 × 107 CFU/ml) q.d. for 14 weeks. | Placebo; One drink of 1.2 dL q.d. for 14 weeks. | Global IBS symptoms score |

| Sinn et al.30 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 40 (65,44.7) | 22.2 | 20, 20 | Rome III; 10% IBS‑D, 27 .5% IBS‑C, 62.5% IBS‑M | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus acidophilus-SDC 2012 and 2013 | One capsule (2 × 109 CFU/ml) b.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d; 4 weeks. | Reduction in abdominal pain score |

| Zeng et al.31 | China, RCT, Single center | 30 (34.5,45.2) | NA | 14, 15 | Rome II; 100% IBS‑D | Combination; Fermented milk containing Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium longum | 200ml (1 × 108 CFU/ml or 1 × 107 CFU/ml) b.i.d.for 4 weeks | Placebo (containing no bacteria); 200mL b.i.d.; 4 weeks | Global IBS scores in GSRS |

| Agrawal et al.32 | UK RCT, Single center | 38 (100,39.5) | 24.8 | 17, 17 | Rome III; 100% IBS‑C | Combination; A fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173010, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactobacillus bulgaricus | One pot (1.25 × 1010 CFU/ pot or 1.2 × 109CFU/pot) q.d. for 4 weeks. | Placebo; One pot q.d.; 4 weeks. | Global symptoms score |

| Enck et al.33 | Germany, RCT, Twelve centers | 298 (49.3,49.6) | 24,2 | 148, 150 | Others; IBS‑D, IBS‑C, IBS‑M | Escherichia coli; Escherichia coli (DSM17252) | 0.75ml (1.5‑4.5 × 107 CFU/ml) drops t.i.d. for one week, then 1.5ml t.i.d. for weeks 2‑8 | Placebo; 0.75ml drops t.i.d. for one week, then 1.5ml t.i.d. for weeks 2‑8 | Adequate relief of IBS core symptoms |

| Hong et al.34 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 70 (32.9,37) | NA | 36, 34 | Rome III; 45.7% IBS-D, 20% IBS‑C, 8.5% IBS‑M,25.8% IBS‑U | Combination; Bifidobacterium Bifidum BGN4, Bifidobacterium lactis AD011, Lactobacillus acidophilus AD031, and Lactobacillus casei IBS041 | One sachet (20 Billi bacteria/sachet) b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One sachet b.i.d.;8 weeks | Reduction of symptom score by at least 50% |

| Hun et al.35 | USA, RCT, Single center | 50 (82,48) | NA | 22, 22 | Rome II;100% IBS-D | Bacillus; Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 | One preparation q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One preparation q.d.; 8 weeks | IBS symptoms (abdominal pain and bloating scores) |

| Williams et al.36 | UK, RCT, Single center | 56 (86.5,39) | NA | 28, 28 | Rome II; 11.5% IBS-D, 27% IBS-C, 61.5% IBS-M | Combination; Lactobacillus acidophilus CUL-60 (NCIMB 30157) and CUL‑21 (NCIMB 30156), Bifidobacterium bifidum CUL‑20 (NCIMB 30153), and Bifidobacterium lactis CUL‑34 (NCIMB 30172) | One capsule (2.5 × 1010 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 8 weeks | IBS Symptom Severity Score |

| Simren et al.37 | Sweden, RCT, Single center | 74 (70.3,43) | NA | 37, 37 | Rome II; 35.1% IBS-D, 14.9% IBS‑C, 50% IBS‑M | Combination; Fermented milk containing Lactobacillus paracasei, ssp. paracasei F19, Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 | 200 ml (5 × 107 CFU/ml) b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; 200 ml nonfermented milk b.i.d.; 8 weeks | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms at least 50% |

| Choi et al.38 | Korea, RCT, Three centers | 90 (46,40.4) | 23.1 | 45, 45 | Rome II; 71.6 % IBS‑D, 28.4% IBS‑M | Saccharomyces; Saccharomyces boulardii | One capsule (2 × 1011 live cells/capsule) b.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d.; 4 weeks | Overall improvement in IBS-QOL |

| Guglielmetti et al.39 | Germany, RCT,Multicenter | 122 (67.2,38.9) | 24.3 | 60, 62 | Rome III; 21.3% IBS‑D, 19.7% IBS-C, 59% IBS‑M | Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium Bifidum MIMBb75 | One capsule (1 × 109CFU/capsule) q.d. for 4 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 4 weeks | Relief of overall IBS symptoms |

| Michail et al.40 | USA, RCT, Single center | 24 (66.7,21.8) | NA | 15, 9 | Rome III; 100% IBS-D | Combination; VSL#3 | One packet (900 billion bacteria/packet) q.d for 8 weeks | Placebo; One packet q.d; 8 weeks | Global symptoms score (a clinical rating scale GSRS) |

| Ringel-Kulka et al.41 | USA, RCT, Single center | 33 (72,45.4) | NA | 16, 17 | Rome III; 100% IBS-D | Combination; Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM (L-NCFM) and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bi-07 (B-LBi07) | (2 × 1011CFU/day) for 8 weeks | Placebo; 8 weeks | Global relief of GI symptoms, Satisfaction with treatment, HR-QOL |

| Sondergaard et al.42 | Sweden, RCT, Two centers | 64 (75,51.2) | 24.8 | 27, 25 | Rome II; Subtype not reported | Combination; Fermented milk containing Lactobacillus paracasei ssp paracasei F19, Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 | 250ml (5 × 107 CFU/ml) b.i.d. for 8 weeks. | Placebo; Acidified milk 250 ml b.i.d; 8 weeks | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms |

| Cha et al.43 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 50 (48,39.7) | 23 | 25, 25 | Rome III; 100% IBS-D | Combination; Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum, and Streptococcus thermophilus | One capsule (0.5 × 1010 CFU/capsule) b.i.d. for 8 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d.; 8 weeks. | Adequate relief of their IBS symptoms at least 50% of the weeks |

| Cui et al.44 | China, RCT, Single center | 60 (70,44.7) | 21.2 | 37, 23 | Rome III; 48.3% IBS-D, 30% IBS‑C, 11.7% IBS-M, 10% IBS-U | Combination; Bifidobacterium longum DSM 20219 and Lactobacillus acidophilus DSM 20079. | 200mg t.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; Two capsules t.i.d.; 4 weeks | Improvement in IBS symptoms |

| Dapoigny et al.45 | France, RCT, Four centers | 52 (70,47.1) | 24 | 25, 25 | Rome III; 30% IBS-D, 22% IBS-C, 34% IBS-M, 14% IBS-U | Lactobacillus; lactobacillus casei rhamnosus LCR35 | One capsule 250 mg (2 × 108 CFU/capsule) t.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; 250 mg t.i.d.; 4 weeks | IBS severity Score |

| Ducrotte et al.46 | France, RCT, Four centers | 214 (29.4,37.3) | NA | 108, 106 | Rome III; 62% IBS-D, 38% non-classified | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus plantarum 299V DSM 9843 | One capsule (10 billion CFU/capsule) q.d. for 4 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 4 weeks | Relief of IBS Symptoms |

| Farup et al.47 | Norway, RCT, Single center | 16 (69,50) | 24 | / | Rome II; 37.5% IBS‑D 6.25% IBS‑C 56.25% IBS‑M | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus plantarum MF 1298 | One capsule (1 × 1010CFU/capsule) q.d. for 6 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 6 weeks. | Global symptoms score |

| Kruis et al.48 | Germany, RCT, Single center | 120 (76.7,45.7) | NA | 60, 60 | Rome II; 45% IBS-D, 29.2% IBS-C, 25.8%IBS-M/U | Escherichia coli; Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | One capsule (2.5-25 × 109 CFU/capsule) o.d. for 4 days then b.i.d. for 12 weeks | Placebo; The same protocol; 12 weeks | Clinical response (Patients Reported satisfied in treatment) |

| Murakami et al.49 | Japan, Single center | 35 (56.5,16.2) | NA | / | Rome III; subtype not reported | Lactobacillus; One capsule containing KB290 (freeze-dried KB290 bodies | (≥1.0 × 1010 CFU/capsule) q.d for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule q.d; for 8 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms, Quality of life (QOL) |

| Begtrup et al.50 | Denmark, RCT, Single center | 131 (30,30.5) | 24.5 | 67, 64 | Rome III; 40.5% IBS‑D, 19.1% IBS‑C, 38.2% IBS‑M, 2.2% IBS‑U | Combination; Lactobacillus paracasei ssp paracasei F19, Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, and Bifidobacterium Lactis Bb 12 | Two capsules (1.3 × 1010 CFU/capsule) b.i.d. for 6 months | Placebo; Two capsules b.i.d.; 24 weeks | Adequate relief of global IBS symptoms |

| Charbonneau et al.51 | USA, RCT, Single center | 76 (81.7,45.1) | 30.2 | 39, 37 | Rome II; subtype not reported | Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium. infantis 35624 | One capsule (1 × 109 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 8 weeks. | Relief of IBS symptoms |

| Ko et al.52 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 26 (63.3,37.3) | 22.8 | 13, 40 | Rome III; 100% IBS‑D | Combination; Bifidobacterium brevis, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Streptococcus thermophilus | One capsule (5 billion bacteria/capsule) t.i.d. for 8 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule t.i.d.; 8 weeks. | Adequate relief of overall IBS symptoms |

| Roberts et al.53 | UK, RCT, Thirteen centers | 179 (85,44.2) | 26.3 | 88, 91 | Rome III; 100% IBS‑C or IBS‑M | Combination; Bifidobacterium lactis I-2494 (previously known as DN173010) Streptococcus thermophilus I-1630, and Lactobacillus bulgaricus I‑1632 and I‑1519 | One pot (1.25 × 1010 CFU/pot or 1.2 × 109 CFU/pot) b.i.d. for 12 weeks | Placebo;One pot b.i.d.; for 12 weeks | Subjective global assessment of symptom relief |

| Abbas et al.54 | Pakistan, RCT, Single center | 72 (26.4,35.4) | 35.4 | 37, 35 | Rome II; 100 % IBS‑D | Saccharomyces; Saccharomyces boulardii | 750 mg q.d for 6 weeks (week 3-8) | Placebo; 6 weeks (week 3-8). | Abdominal pain |

| Jafari et al.55 | Iran, RCT,Single center | 108 (60.2,36.7) | NA | 51, 46 | Rome III; subtype not reported | Combination; Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactisBB‑12®, Lactobacillus acidophilus LA‑5®, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LBY‑27, and Streptococcus thermophilus STY‑31 | One capsule (4 × 108 CFU/capsule) b.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; b.i.d.; 4 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms |

| Lorenzo-Zuniga et al.56 | Spain, RCT, Two centers | 84 (63.1,46.8) | 25.6 | 55, 29 | Rome III; 100% IBS-D | Combination; Lactobacillus plantarum CECT7484, Lactobacillus plantarum CECT7485, and Pediococcus acidilactici CECT7483 | High dose (1-3 × 1010 CFU/capsule) q.d. or Low dose (3-6 × 109CFU/capsule) t.i.d. for 6 weeks | Placebo; One capsule q.d. for 6 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms |

| Ludidi et al.57 | Netherlands, RCT, Single center | 40 (67.5,40.5) | 25.5 | 21, 19 | Rome III; 42.5% IBS‑D, 10% IBS‑C, 30% IBS‑M, 17 .5% IBS‑U | Combination; Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus casei W56, Lactobacillus salivarius W57, Lactococcus lactis W58, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus W71 | One sachet (5 × 109 CFU/sachet) o.d. for 6 weeks | Placebo; One sachet (5 g) o.d. for 6 weeks | Mean symptom composite score |

| Pedersen et al.58 | Denmark, RCT, Single center | 123 (73.2,37.3) | 22.7 | 41, 40 | Rome III; 40.7% IBS-D, 15.4% IBS-C 38.2% IBS-M | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | One capsule b.i.d. for 6 weeks | Low FODMAP diet for 6 weeks; Normal Danish/Western diet for 6 weeks | Reduction of IBS-SSS |

| Rogha et al.59 | Iran, RCT, Single center | 85 (78.6,39.8) | NA | 33, 39 | Rome III; 12.5% IBS-C 32% IBS-D 50% IBS-M | Bacillus; Bacillus Coagulans and Fructo-oligosaccharides (100 mg). | One tablet (15 × 107 Spores) t,i,d, for 12weeks | Placebo; One tablet t,i,d,; 12 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms |

| Sisson et al.60 | UK, RCT, Single center | 186 (69.4,38.3) | NA | 124, 62 | Rome III; 37 .6% IBS‑D, 21.5% IBS-C, 35.5% IBS‑M, 5.4% IBS‑U | Combination; Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCIMB 30174, Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 30173, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCIMB 30175, and Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 30176 | 1 ml (1 × 1010 CFU/50 ml) q.d. for 12weeks | Placebo (containing inert flavorings and water); 1 ml q.d.; 12 weeks | IBS-SSS |

| Stevenson et al.61 | South Africa, RCT, Single center | 81 (97.5,47.9) | 28.9 | 54, 27 | Rome III; 37.6% IBS-D, 21.5% IBS-C | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus plantarum 299v | Two capsules (5 × 109 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; Two capsules q.d.; 8 weeks | IBS symptom severity Scores |

| Yoon et al.62 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 49 (65.3,44.5) | NA | 25, 24 | Rome III; 53.1% IBS-D, 40.8% IBS-C, 6.1% IBS-M | Combination; Bifidobacterium bifidum KCTC 12199BP, Bifidobacterium Lactis KCTC 11904BP, Bifidobacteriu Longum KCTC 12200BP, Lactobacillus acidophilus KCTC 11906BP, Lactobacillus rhamnosus KCTC 12202BP, and Streptococcus thermophilus KCTC 11870BP | One capsule (5 × 109viable cells/capsule) b.i.d. for 4 weeks | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d.; 4 weeks | Global relief of IBS Symptoms |

| Pineton de Chambrun et al.63 | France, RCT, Single center | 200 (86,44) | NA | 93, 86 | Rome III; 28.5% IBS-D, 46.9% IBS‑C, 24.6% IBS‑M | Saccharomyces; Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCMI‑3856 | One capsule (8 × 109 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 8 weeks | Improvement of abdominal pain adverse event |

| Wong et al.64 | Singapore, RCT, Single center | 42 (45.2,47) | NA | 20, 22 | Rome III; IBS‑M | Combination; VSL#3 | Four capsules (225 billion bacteria/capsule) b.i.d. for 6 weeks | Placebo;four capsules b.i.d.; 6 weeks | Overall IBS symptom scores |

| Yoon et al.65 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 81 (46.3,59.3) | NA | 39, 42 | Rome III; 48.1% IBS-D, 18.5% IBS-C, 21%IBS-M, 12.4%IBS-U | Combination; Bifidobacterium bifidum (KCTC 12199BP,) Bifidobacterium lactis (KCTC11904BP), Bifidobacterium Longum (KCTC 12200BP), Lactobacillus acidophilus (KCTC 11906BP), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (KCTC 12202BP), and Streptococcus thermophilus (KCTC 11870BP) | One capsule (5 × 109 viable cells/capsule) b.i.d. for 4 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d.; 4 weeks | Adequate relief of overall IBS symptoms |

| Lyra et al.66 | Finland, RCT, Two centers | 391 (74.7,47.9) | 24.7 | 260, 131 | Rome III; 38.9% IBS‑D, 16.6% IBS‑C, 44% IBS‑M, 0.5% IBS‑U | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM (ATCC 700396) | One capsule (low dose: 1 × 109 CFU/capsule; high dose: 1 × 1010 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 1 2 weeks | Placebo;One capsule q.d.; 12 weeks | IBS symptom severity Scores |

| Spiller et al.67 | UK, RCT, Single center | 379 (83.6,45.4) | NA | 192, 187 | Rome III; 20.8 % IBS-D, 47.5 % IBS‑C, 31.7% IBS‑M | Saccharomyces; Saccharomyces. cerevisiae I-3856 | 1000 mg (8 × 109 CFU/g) q.d. for 12 weeks | Placebo (calcium phosphate and maltodextrin) q.d.; 12 weeks | Improvement of 50% of the weekly average "intestinal pain/discomfort score" |

| Thijssen et al.68 | Holland, RCT, Four centers | 80 (68.8,41.8) | 25.1 | 39, 41 | Rome II, 30% IBS-D, 25% IBS-C, 28.75% IBS-M, 16.25% IBS-U | A fermented milk drink (65ml per bottle); Lactobacillus | One bottle (6.5 × 109 CFU/bottle) b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One bottle (65ml) b.i.d.; 8 weeks | Mean symptom score decrease of at least 30% |

| Hod et al.69 | Israel, RCT, Single center | 107 (100,29.5) | 22.3 | 54, 53 | Rome III; 100% IBS-D | Combination; Lactobacillus rhamnosus LR5, Lactobacillus casei LC5, Lactobacillus Paracasei.LPC5, Lactobacillus plantarum LP3, Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1, Bifidobacterium Bifidum BF3, Bifidobacterium Longum BG7, Bifidobacterium breve BR3, Bifidobacterium infantis BT1, Streptococcus, thermophilus ST3, Lactococcus bulgaricus LG1, and Lactococcus Lactis SL6 | b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; b.i.d.; 8 weeks | Abdominal pain, overall responder rates |

| Pinto-Sanchez et al.70 | Canada, RCT, Single center | 44 (54,43.3) | 24.9 | 22, 22 | Rome III; 61.4% IBS‑D, 38.6% IBS‑M | Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium longum, NCC3001 | (1.0 × 1010 CFU/gram powder with maltodextrin) for 6 weeks. | Placebo; 6 weeks | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms |

| Staudacher et al.71 | UK, RCT, two centers | 104 (67.5,35.5) | 24.5 | / | Rome III; 66.3% IBS-D, 23.1% IBS-M, 10.6% IBS-U | Combination; VSL#3 | 4 weeks | Placebo, sham diet; 4 weeks | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms |

| Shin et al.72 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 60 (56.9,36.5) | 23.4 | 27, 24 | Rome III; 100% IBS‑D, | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus. gasseri BNR17 | Two capsules b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; Two capsules b.i.d.; 8 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms |

| Catinean et al.73 | Romania, RCT, Single center | 90 (60,39.4) | 25.2 | 30, 60 | Rome III; 100 % IBS-D | Bacillus; MegaSporeBiotic a mixture of spores of five Bacillus spp | q.d. for 1 week, then b.i.d. for 24 days. | Ten-days rifaximin treatment followed by either a nutraceutical agent or a Low FODMAPs for 24 days | IBS-SSS Score |

| Madempudi et al.74 | India, RCT, Single center | 136 (27.8,43.4) | 24.8 | 53, 55 | Rome III; IBS-D, IBS‑C, IBS‑M, IBS‑U | Bacillus; Bacillus coagulants Unique IS2 | One capsule (2 billion CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo;One capsule q.d.; 8 weeks | Relief of abdominal pain, Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms |

| Oh et al.75 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 55 (72,32.8) | 21.5 | 26, 24 | Rome III; 42% IBS‑D,20% IBS‑M, 38% IBS‑U | Combination; Lactobacillus species, Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum. | q.d. for 4 weeks. | Placebo; q.d.; 4 weeks. | Relief of IBS Symptoms |

| Andresen et al.76 | Germany, RCT, twenty-center | 443 (69.5,41.4) | 24.6 | 221, 222 | Rome III; 40% IBS‑D, 24.1% IBS‑C, 7.7% IBS‑M, 28.2% IBS‑U | Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 | Two capsules (1 × 109 cells/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; q.d.; 8 weeks | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms |

| Gayathri et al.77 | India, RCT, Single center | 100 (34,41) | NA | 52, 48 | Rome III;65 % IBS-D, 24 % IBS‑C, 11% IBS‑M | Saccharomyces; Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856 | One capsule (2 × 109 CFU/capsule) b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d.; 8 weeks. | Abdominal pain score |

| Kim et al.78 | Korea, RCT, Single center | 63 (74.6,36) | NA | 32, 31 | Rome II; 100% IBS-D | Combination; Bifidobacterium longum BORI, Bifidobacterium bifidum BGN4, Bifidobacterium lactis AD011, Bifidobacterium infantis IBS007, and Lactobacillus acidophilus AD031 | One capsule (5 × 109viable cells/capsule) t.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule t.i.d.; 8 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms |

| Lewis et al.79 | Canada, RCT, Single center | 285 (77.7,42) | NA | 167, 81 | Rome III; 15.1% IBS-D, 11.2% IBS-C, 73.7%IBS-M | Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium; Lactobacillus paracasei HA-196 or Bifidobacterium longum R0175 | One capsule (10 × 109 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks. | Placebo; One capsule q.d.; 8 weeks. | IBS Symptom Severity Score |

| Martoni et al.80 | USA, RCT, Twelve-center | 336 (49.5,39.5) | 24 | 224, 112 | Rome III; Subtype not reported | Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium; Lactobacillus acidophilus DDS-1 or Bifidobacterium lactis UABla‐12 | One capsule (1 × 1010 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 6 weeks. | Placebo; q.d.; 6 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms score |

| Sadrin et al.81 | France, RCT, Multicenter | 80 (71,48.9) | NA | 40, 40 | Rome III; Subtype not reported | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Lactobacillus acidophilus subsp. Helveticus LAFTI L10 | Two capsules (5 × 109CFU/capsule) b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo;Two capsules b.i.d.; 8 weeks | Relief of IBS symptoms score |

| Wilson et al.82 | UK, RCT, Single center | 69 (55.1,34.1) | 24.7 | 24, 45 | Rome III; 65% IBS-D | Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB 41171 | q.d. for 4 weeks. | Placebo; q.d.; 4 weeks. | Relief of IBS Symptoms |

| Barraza-Ortiz et al.83 | México, RCT, Single center | 55 (67.2,45.5) | 25.2 | 37, 18 | Rome IV; 52.7% IBS-D 47.3% IBS-M | Combination; Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7484, Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7485, and Pediococcus acidilactici CECT 7483 | t.i.d for 6 week | Placebo; t,i,d, 6 weeks | Response rate in QoL, Abdominal pain |

| Gupta et al.84 | India, RCT, Single center | 40 (30,35.5) | 23.8 | 20, 20 | Rome IV; Subtype not reported | Bacillus; Bacillus coagulants LBSC | t.i.d for 80 days | Placebo; t,i,d,; 80 days | IBS-SSS, Change in stool consistency |

| Skrzydło-Radomańska et al.85 | Poland, RCT, Single center | 51 (64.5,43.1) | 25.9 | 25, 23 | Rome III; 100% IBS-D | Combination; Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus thermophilus | One capsule b.i.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; One capsule b.i.d.; 8 weeks | IBS-SSS, Global Improvement Scale (IBS-GIS) |

| Mack et al.86 | Germany, RCT, Multicenter | 389 (69,46.4) | 26 | 191, 198 | Rome III; 16.1% IBS-C 39.8% IBS-D 36,2% IBS-M | Combination; Escherichia coli (DSM 17252) and Enterococcus faecalis (DSM 16440) | 10 drops (0.71 mL) 3 × /day during week 1, 20 drops (1.42 mL) 3 × /day during week 2, 30 drops (2.14 mL) 3 × /day during week 3, and 30 drops 3 × /day until week 26 | Placebo; The same dose and duration | IBS Global Assessment of Improvement Scale (IBS-GAI), Abdominal pain |

| Moeen-Ul-Haq et al.87 | Pakistan, RCT, Single center | 120 (41.7,35.9) | NA | 55, 53 | Rome III; 25.9% IBS-C 30.6% IBS-D 43,5% IBS-M | Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus plantarum 299v | (5x1010 CFU) for 4 weeks | Placebo (comprised micro-crystalline cellulose powder); 4 weeks | Daily frequency of abdominal pain, Improvement in the severity of abdominal pain, The severity of bloating |

| Mourey et al.88 | France, RCT, Four centers | 456 (86,40.5) | NA | 230, 226 | Rome IV; 100% IBS-C | Saccharomyces; Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856 | Two capsules (8 × 109 CFU/capsule) q.d. for 8 weeks | Placebo; q.d.; 8 weeks | Global IBS symptoms |

BMI, body mass index; B.i.d, twice a day. CFU, colony forming units; FODMAP, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols; GSRS, gastrointestinal symptom rating scale; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-C, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, un-subtyped irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-SSS, irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity score; IBS-QOL, evaluation of the irritable bowel syndrome quality of life; O.d, once every two days. Q.d, four times a day; RCT, randomized controlled trial; T.i.d, three times a day. VSL#3, a combination of three types of Bifidobacterium (Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, and Bifidobacterium breve).

This column is arranged according to years.

(I, P) refers to the sample sizes for probiotics and control groups, respectively, whereas the I refers to the probiotic group and the P refers to the control group.

This column lists numerous abbreviations for the probiotic components which were named as the article reported or according to the nomenclature or naming system for bacteria suggested by the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes.

Figure 2.

The three-level meta-analysis concept and results. IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SMD, standardized mean difference. Note: The figure shows the concept of the three-level meta-analysis model and the results of the three outcomes. The three-level meta-analysis was conceived and developed to solve the problems of correlated data and missing information, which were unsatisfactorily settled in the traditional meta-analysis model9. For example, the severity of global IBS symptoms was assessed by differential scales at differential time points, and in most circumstances in traditional meta-analyses, data from one specific scale measured at one time point would be selected, which induced loss of information. We adopted the three-level model to synthesize all data from the relevant scales measured at defined time intervals, and we provided a general effect size using the SMD. According to previous literature, an absolute value of SMD larger than 0.5 would indicate a medium size of effect15, meeting the standard of recommendation for clinical practice. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that all SMDs for the three outcomes exceeded that cut-off point of 0.5.

The severity of global IBS symptoms

The three-level meta-analysis – included 63 studies17–22,25–34,36–48,50,52,53,55–58,60–69,71–76,78–81,83–87 and generated 217 effect sizes – showed an overall effect of probiotics was significantly superior over placebo (SMD −0.55, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.34, P<0.001; Fig. 2), but with significant heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q =2906.24, P<0.001). We further analyzed within-study and between-study variance and found a total I 2 of 96.3%, a within-study I 2 of 79.5%, and a between-study I 2 of 16.8%. We then compared the traditional two-level meta-analysis model with the three-level model and found the three-level model reduced AIC from 913.7 to 906 and the BIC from 920.4 to 916.2, and the likelihood ratio test (LRT) demonstrated a significant difference between the two models (chi-squared (χ 2) =9.652, P=0.002) – showing the three-level model provided a better fit. The funnel plot showed no signs of publication bias (eFigure 2, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A877).

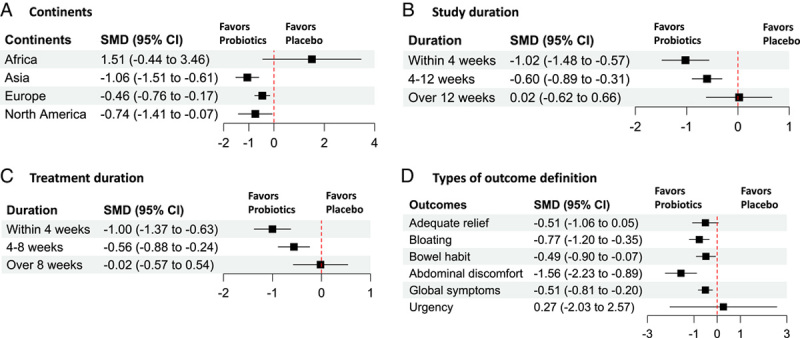

The moderator analyses showed that participants from different continents reported differential effects, while participants from the Asia region reported the largest effect size (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we found that study duration affected the effect size, and a longer study duration was associated with a smaller effect size (Fig. 3B). We also found that longer treatment duration was associated with a smaller effect size (Fig. 3C). The type of outcome impact also had an impact, and probiotics had a larger effect size on abdominal discomfort (SMD −1.55, 95% CI −2.97 to −0.15, P=0.017; Fig. 3D). Other factors had no significant impact on the effect sizes of the probiotics (Table 2).

Figure 3.

The moderators of the probiotic effects on global IBS symptoms. IBS, irritable bowel syndrome. SMD, standard mean difference. Note: The figure shows that (A) continents, (B) study duration, (C) treatment duration, and (D) types of outcome definition are the most important moderators of the probiotic effects. (A) The study population in Asia, Europe, and North America had larger effect sizes than in Africa. (B) and (C), shorter study duration (<4 weeks) and treatment duration (<4 weeks) were associated with larger effect sizes. (D) The outcome of abdominal discomfort was associated with larger effect sizes than other outcomes.

Table 2.

Moderator analysis of the outcome measurements.

| Global IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain | QoL assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderators | Estimate | P * | Estimate | P * | Estimate | P * |

| Continents | ||||||

| Africa | 1.51 (−0.44 to 3.46) | Reference | NA | NA | −0.23 (−3.38 to 2.92) | Reference |

| Asia | −1.06 (−1.51 to −0.61) | 0.012 | −1.44 (−2.24 to −0.64) | Reference | 2.71 (0.72 to 4.7) | 0.118 |

| Europe | −0.46 (−0.76 to −0.23) | 0.05 | −0.91 (−1.58 to −0.23) | 0.314 | 0.98 (−0.07 to 2.02) | 0.466 |

| North American | −0.74 (−1.41 to −0.07) | 0.033 | −0.2 (−1.78 to 1.38) | 0.167 | 0.76 (−0.99 to 2.52) | 0.58 |

| Assessment time points | ||||||

| Within 8 weeks | −0.7 (−0.93 to −0.48) | Reference | −0.97 (−1.36 to −0.59) | Reference | 1.18 (0.56 to 1.79) | Reference |

| 9–16 weeks | 0.06 (−0.46 to 0.57) | 0.05 | −0.85 (−1.79 to 0.08) | 0.807 | 0.53 (−0.28 to 1.34) | 0.128 |

| 17–24 weeks | −0.26 (−1.1 to 0.59) | 0.316 | −0.54 (−2.62 to 1.53) | 0.686 | 0.65 (−1.9 to 3.19) | 0.68 |

| >24 weeks | 1.48 (−0.89 to 3.86) | 0.07 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| RCT types | ||||||

| Single center | −0.66 (−0.96 to −0.37) | 0.672 | −1.15 (−1.74 to −0.55) | Reference | 1.3 (0.1 to 2.49) | Reference |

| Multicenter | −0.55 (−0.97 to −0.14) | 0.614 | −0.82 (−1.68 to 0.04) | 0.534 | 0.99 (−0.16 to 2.15) | 0.715 |

| Multi-nation | 0.18 (−2.67 to 3.04) | Reference | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Number of study sites | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.375 | 0.04 (−0.034 to 0.107) | 0.305 | −0.03 (−0.28 to 0.22) | 0.824 |

| Study duration | ||||||

| <4 weeks | −1.02 (−1.48 to −0.57) | Reference | −1.71 (−2.62 to −0.8) | Reference | 6.58 (4.09 to 9.07) | Reference |

| 4–12 weeks | −0.6 (−0.89 to −0.31) | 0.126 | −0.75 (−1.37 to −0.13) | 0.086 | 0.95 (0.31 to 1.58) | <0.001 |

| >12 weeks | 0.02 (−0.62 to 0.66) | 0.009 | −0.94 (−2.45 to 0.57) | 0.387 | 0.54 (−0.27 to 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) | 0.44 | −0.006 (−0.1 to 0.09) | 0.895 | −0.25 (−0.51 to 0.006) | 0.055 |

| Proportion of female | 0.005 (−0.008 to 0.02) | 0.463 | 0.02 (0.001 to 0.046) | 0.04 | −0.05 (−0.1 to 0.008) | 0.088 |

| Proportion of drop-outs | 0.008 (−0.004 to 0.02) | 0.205 | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.05) | 0.347 | −0.007 (−0.05 to 0.03) | 0.748 |

| Disease duration | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.122) | 0.523 | 0.11 (−0.78 to 1) | 0.791 | −0.11 (−0.62 to 0.39) | 0.635 |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||||||

| Others | −0.78 (−1.78 to 0.25) | Reference | −1.07 (−2.82 to 0.67) | Reference | 1.18 (−3.03 to 5.4) | Reference |

| Rome | −0.25 (−2.4 to 1.91) | 0.667 | −0.39 (−3.42 to 2.65) | 0.697 | NA | NA |

| Rome II | −0.61 (−1.1 to −0.16) | 0.784 | −1.37 (−2.41 to −0.32) | 0.774 | 1.55 (0.23 to 2.87) | 0.866 |

| Rome III | −0.62 (−0.94 to −0.3) | 0.781 | −1 (−1.65 to −0.35) | 0.936 | 0.85 (−0.46 to 2.16) | 0.88 |

| Rome IV | −0.56 (−1.91 to −0.79) | 0.807 | −0.38 (−2.58 to 1.83) | 0.623 | 0.33 (−3.13 to 3.79) | 0.753 |

| Treatment duration | ||||||

| <4 weeks | −1 (−1.37 to −0.63) | Reference | −1.45 (−2.24 to −0.65) | Reference | 6.58 (4.13 to 9.02) | Reference |

| 4–8 weeks | −0.56 (−0.88 to −0.24) | 0.08 | −0.89 (−1.56 to −0.22) | 0.286 | 0.99 (0.44 to 1.54) | <0.001 |

| >8 weeks | −0.02 (−0.57 to 0.54) | 0.004 | −0.26 (−1.87 to 1.35) | 0.19 | 0.1 (−0.94 to 1.14) | <0.001 |

| Types of probiotics | ||||||

| Bacillus | −0.58 (−1.62 to 0.46) | Reference | −2.23 (−4.31 to −0.14) | Reference | NA | NA |

| Bifidobacterium | −0.77 (−1.42 to −0.12) | 0.757 | −0.44 (−1.54 to 0.65) | 0.136 | 0.77 (−0.27 to 1.81) | Reference |

| Combination | −0.65 (−0.96 to −0.34) | 0.901 | −1.24 (−1.85 to −0.63) | 0.37 | 1.18 (0.65 to 1.71) | 0.487 |

| Enterococcus | −0.51 (−2.07 to 1.06) | 0.939 | −1.38 (−4.44 to 1.69) | 0.651 | NA | NA |

| Escherichia coli | −0.59 (−2.06 to 0.87) | 0.987 | −0.65 (−3.97 to 2.67) | 0.427 | 0.61 (−0.92 to 2.15) | 0.866 |

| Lactobacillus | −0.6 (−1.07 to −0.13) | 0.969 | −1.04 (−1.78 to −0.31) | 0.29 | 0.12 (−0.49 to 0.73) | 0.285 |

| Saccharomyces | −0.09 (−1.21 to 1.03) | 0.529 | 0.41 (−0.93 to 1.75) | 0.037 | 6.45 (4.36 to 8.55) | <0.001 |

| Types of outcomes | ||||||

| Continuous | −0.5 (−0.82 to −0.18) | Reference | −1.08 (−1.55 to −0.6) | Reference | 1.4 (0.56 to 2.24) | Reference |

| Categorical | −0.71 (−0.97 to −0.44) | 0.301 | −0.59 (−1.37 to 0.18) | 0.279 | 1.23 (0.06 to 2.4) | 0.895 |

| Types of outcome definition | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Adequate relief | −0.51 (−1.06 to 0.05) | Reference | ||||

| Bloating | −0.77 (−1.2 to −0.35) | 0.445 | ||||

| Bowel habits | −0.49 (−0.9 to −0.07) | 0.953 | ||||

| Abdominal discomfort | −1.56 (−2.23 to −0.89) | 0.017 | ||||

| Global symptoms | −0.51 (−0.81 to −0.2) | 0.999 | ||||

| Urgency | 0.27 (−2.03 to 2.57) | 0.518 | ||||

NA, not available; QoL, quality of life.

The P values were estimated as the reference categories being compared with the reference category.

The severity of abdominal pain

The model – included 48 studies17–22,24–34,36,37,39,40,43–46,49,52,54,55,57,62–67,69,72,74,75,77–81,84,87,88 and generated 92 effect sizes – showed probiotics reduces the severity of abdominal pain (SMD −0.89, 95% CI −1.29 to −0.5, P<0.001; Fig. 2), but with significant heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q =1923.12, P<0.001). We found a total I 2 of 98.4%, a within-study I 2 of 74.7%, and a between-study I 2 of 23.7%. A slightly reduced AIC (from 363 to 360.5) was found in the three-level model when compared with the traditional one, the LRT test was still significant (χ 2=4.1825 P=0.034). The funnel plot showed no signs of publication bias (eFigure 3, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A877).

In the moderator analysis, we found that the study duration affected the effect sizes. RCTs with a study duration shorter than 4 weeks (SMD, −1.71, 95% CI −2.62 to −0.8) had significantly larger effect sizes than other RCTs with a study duration longer than 4 weeks (P<0.001; Table 2). The proportion of females also affected the effect sizes, RCTs with a higher proportion of females were associated with smaller effect sizes (coefficient estimate 0.02, 95% CI 0.001–0.046, P=0.04). For other factors, no significant impact was found (Table 2).

Quality of life assessment

The model – included 23 studies20,22,23,28,33,36–38,40,43,48,56,60,61,63,66,68,71,78,80,83,85,88 and generated 71 effect sizes – showed that probiotics significantly improved the quality of life in patients with IBS (SMD 0.99, 95% CI 0.45–1.54, P<0.001; Fig. 2), but with significant heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q =788.7, P<0.001). The total I 2, within-study I 2, and between-study I 2 were 98%, 41.8%, and 56.2%, respectively. Compared with the traditional meta-analysis model, the three-level model had significantly reduced AIC (268.2–257.5) and BIC (272.7–264.2) (LRT=12.7, P<0.001). The funnel plot showed signs of publication bias (eFigure 4, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A877); one study37 demonstrated a larger size than other studies.

The moderator analysis showed that the treatment duration and the types of probiotics affected the effect size. A treatment duration within 4 weeks showed a significantly larger effect than a treatment duration between 4 and 8 weeks and a treatment duration longer than 8 weeks (Table 2). The probiotic strains containing Bacillus and Bifidobacterium showed significantly larger effect sizes than those containing Saccharomyces (Table 2).

Discussion

By pooling all the effect sizes from the included RCTs, we found a general medium effect size (with an SMD larger than 0.5) of probiotics on the improvement of IBS symptoms compared with placebo, and a large effect size (with an SMD larger than 0.8) of probiotics on the abdominal pain and the scores of quality-of-life assessments. We found that the treatment duration and study duration were the most important moderators of effect, and a longer study duration or treatment duration was associated with a smaller effect size. When the treatment duration was longer than 8 weeks and the study duration was longer than 12 weeks, the effect sizes dropped to −0.02 and 0.02 (extremely small effect size), respectively.

Our meta-analysis included a larger number of studies than the previous and recent systematic reviews that assessed the efficacy of probiotics for IBS6,7 because we used the transformation between odds ratios and SMDs, which has been suggested and reported in the Cochrane handbook16 and methodological reports9,14 to increase the statistical strength of the meta-analysis. The ability to include more studies might also be attributed to the application of the three-level meta-analysis model, which prompts the estimation of the general effect of the probiotics on IBS and confirms a medium effect size of probiotics on the improvement of global IBS symptoms (SMD 0.56) – suggesting a possible generalization to routine practice.

Shorter treatment duration or study duration being associated with larger treatment effects of probiotics was one of the major findings of our meta-analysis. A network meta-analysis published in 2022 reported that treatment duration could affect the efficacy of probiotics in the relief of abdominal pain and strain, and it showed that using Bacillus coagulans for 8 weeks was the most efficacious89. Dale and colleagues found that longer treatment duration might be associated with better efficacy in the treatment of IBS with probiotics90, while the other two studies showed that a shorter treatment duration of probiotics would be more efficacious91,92. Our meta-analysis, with a larger number of included trials and the inclusion of more efficacy data (through a third-level model), confirmed that shorter treatment duration was associated with a larger treatment effect. Several hypotheses were proposed for this phenomenon. First, trials with small sample sizes and single-center design were more likely to have short treatment duration and study duration, which could be the consequence of a shortage of study funding, so the larger treatment effects could be explained by small-study effects93. Second, the larger effect of probiotics on IBS might also be attributed to a powerful placebo – similar to the effect of sham device or sham acupuncture reported in previous studies94–96. In a meta-analysis investigating the magnitude of placebo response in IBS trials, short treatment duration was found to be associated with a large placebo effect97. Third, the moderator effect of short treatment duration might reflect the association between the severity of the IBS symptoms and the effect of the assessed intervention. Patients with severer IBS symptoms might report a smaller treatment effect of probiotics, and the physicians might be inclined to suggest a longer treatment duration, especially for those with refractory IBS98. Regarding that, the diagnostic criteria of refractory IBS are difficult to define and the severity of IBS disease is determined by several factors – health-related quality of life, psychosocial factors, healthcare utilization behaviors, and burden of illness99, so it is impossible to test this hypothesis based on the included trials in this meta-analysis since most of the included studies did not classify the disease severity owing to the lack of standard criteria. This informs that there is an urgent need for a standard scale to estimate the overall severity of IBS to minimize the heterogeneity caused by the study population in future meta-analyses on probiotics for IBS. Additionally, future RCTs are encouraged to report symptom severity of IBS using scales like IBS-SSS in baseline evaluation to facilitate subgroup or meta-regression analysis for clarifying the relationship between severity of IBS and probiotic treatment duration.

Although we did not find an impact of different types of probiotics on the improvement of IBS symptoms, we found that Bacillus strains led to better improvement in abdominal pain than other strains and were significantly better than the Saccharomyces strain. This finding was consistent with a recent network meta-analysis comparing differential probiotics for the treatment of IBS7, which implies that the Bacillus strains might be developed for the treatment of functional abdominal pain and warrants further clarification.

Our study had several limitations. First, the certainty of the evidence was low because most of the included trials were classified as with some concerns or a high risk of bias. Many trials had some concerns in the randomization process (mainly the problem of the transparency of allocation concealment) and the measurement of the outcomes. Second, the large heterogeneity in the meta-analysis was also a concern. The heterogeneity might be caused by the difference in the study population and the intervention protocols. We ran the moderator analysis and confirmed that the duration of treatment and study, the study regions, and the types of outcomes might be the source of heterogeneity. Third, although the method of transforming between OR and SMD enlarged the sample size of the meta-analysis, it made the explanation of the results difficult for clinical practitioners, who might transform it back to the original scale by multiplying the SMD generated from the meta-analysis by the standard deviation of the specific scale14. Fourth, forty-eight reports were excluded for the unavailability of full-text copies, which were mainly abstracts of conference presentations and supplementary issues. These reports, known as grey literature, might be valuable for our meta-analysis and might change the conclusion of our study. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis might therefore be warranted while many of them were available with sufficient data for analysis.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis suggested a medium short-term effect of probiotics on the improvement of global IBS symptoms and abdominal pain. We found that the treatment duration, study regions, the types of outcomes, and the types of probiotics might be major effect moderators, which warrants further investigation.

Ethical approval

This article is a systematic review and meta-analysis; ethical approvals were acquired in the original studies, and additional approval was not required for this meta-analysis.

Consent

This article is a systematic review and meta-analysis; consents were acquired in the original studies, and additional consents were not required for this meta-analysis.

Sources of funding

M.C. received a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82274529) and a grant (no. 2022NSFSC1503) from the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province. H.Z. received a grant from the Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Innovation Research Team (no. 2021JDTD0007).

Author contribution

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M.C. and H.Z.: conceived and designed the study; M.C., L.Y., C.-R.X., X.-Y.W., S.-J.F., and X.-Y.X.: acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the study data. M.C.: drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/rq87j).

Guarantor

Hui Zheng.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data used for analysis will be available upon reasonable request, which will be released in the Open Science Framework platform (https://osf.io/rq87j).

Role of the funder/sponsor

The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study, and they had no role in the decision process to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 10 August 2023

Contributor Information

Min Chen, Email: cm@cdutcm.edu.cn.

Lu Yuan, Email: 314454939@qq.com.

Chao-Rong Xie, Email: Xiechaorong@stu.cdutcm.edu.cn.

Xiao-Ying Wang, Email: wangxiaoying@stu.cdutcm.edu.cn.

Si-Jia Feng, Email: fengsijia@stu.cdutcm.edu.cn.

Xin-Yu Xiao, Email: xiaoxinyu@stu.cdutcm.edu.cn.

Hui Zheng, Email: zhenghui@cdutcm.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Oka P, Parr H, Barberio B, et al. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto S, Hashizume K, Wada N, et al. Relationship between overactive bladder and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale internet survey in Japan using the overactive bladder symptom score and Rome III criteria. BJU Int 2013;111:647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pace F, Molteni P, Bollani S, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease versus irritable bowel syndrome: a hospital-based, case–control study of disease impact on quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003;38:1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman SB, Schnadower D, Tarr PI. The probiotic conundrum: regulatory confusion, conflicting studies, and safety concerns. JAMA 2020;323:823–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford AC, Harris LA, Lacy BE, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:1044–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shang X, E F-F, Guo K-L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of probiotics for patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2022;14:2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFarland LV, Karakan T, Karatas A. Strain-specific and outcome-specific efficacy of probiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021;41:101154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leis R, de Castro M-J, de Lamas C, et al. Effects of prebiotic and probiotic supplementation on lactase deficiency and lactose intolerance: a systematic review of controlled trials. Nutrients 2020;12:1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riley RD, Jackson D, Salanti G, et al. Multivariate and network meta-analysis of multiple outcomes and multiple treatments: rationale, concepts, and examples. BMJ 2017;358:j3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houben M, Van Den Noortgate W, Kuppens P. The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2015;141:901–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2000;19:3127–3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murad MH, Wang Z, Chu H, et al. When continuous outcomes are measured using different scales: guide for meta-analysis and interpretation. BMJ 2019;364:k4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, et al. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2021;31:010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 51 0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gade J, Thorn P. Paraghurt for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. A controlled clinical investigation from general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 1989;7:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobaek S, Johansson ML, Molin G, et al. Alteration of intestinal microflora is associated with reduction in abdominal bloating and pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1231–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niedzielin K, Kordecki H, Birkenfeld B. A controlled, double-blind, randomized study on the efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum 299V in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;13:1143–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HJ, Camilleri M, McKinzie S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic, VSL#3, on gut transit and symptoms in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kajander K, Hatakka K, Poussa T, et al. A probiotic mixture alleviates symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a controlled 6-month intervention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Vazquez Roque MI, Camilleri M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination VSL# 3 and placebo in irritable bowel syndrome with bloating. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005;17:687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niv E, Naftali T, Hallak R, et al. The efficacy of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome – a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Clin Nutr 2005;24:925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YG, Moon JT, Lee KM, et al. The effects of probiotics on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Korean J Gastroenterol 2006;47:413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1581–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyonnet D, Chassany O, Ducrotte P, et al. Effect of a fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 on the health-related quality of life and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drouault-Holowacz S, Bieuvelet S, Burckel A, et al. A double blind randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination in 100 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2008;32:147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enck P, Zimmermann K, Menke G, et al. A mixture of Escherichia coli (DSM 17252) and Enterococcus faecalis (DSM 16440) for treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome – a randomized controlled trial with primary care physicians. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008;20:1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajander K, Myllyluoma E, Rajilić-Stojanović M, et al. Clinical trial: multispecies probiotic supplementation alleviates the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and stabilizes intestinal microbiota. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinn DH, Song JH, Kim HJ, et al. Therapeutic effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus-SDC 2012, 2013 in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 2008;53:2714–2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng J, Li Y-Q, Zuo X-L, et al. Clinical trial: effect of active lactic acid bacteria on mucosal barrier function in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:994–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agrawal A, Houghton LA, Morris J, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk product containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 on abdominal distension and gastrointestinal transit in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enck P, Zimmermann K, Menke G, et al. Randomized controlled treatment trial of irritable bowel syndrome with a probiotic E.-coli preparation (DSM17252) compared to placebo. Z Gastroenterol 2009;47:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong KS, Kang HW, Im JP, et al. Effect of probiotics on symptoms in Korean adults with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver 2009;3:101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hun L. Bacillus coagulans significantly improved abdominal pain and bloating in patients with IBS. Postgrad Med 2009;121:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams EA, Stimpson J, Wang D, et al. Clinical trial: a multistrain probiotic preparation significantly reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simrén M, Öhman L, Olsson J, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk containing three probiotic bacteria in patients with irritable bowel syndrome – a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi CH, Jo SY, Park HJ, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in irritable bowel syndrome: effect on quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guglielmetti S, Mora D, Gschwender M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life – a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michail S, Kenche H. Gut microbiota is not modified by randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of VSL#3 in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2011;3:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ringel-Kulka T, Palsson OS, Maier D, et al. Probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders: a double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sondergaard B, Olsson J, Ohlson K, et al. Effects of probiotic fermented milk on symptoms and intestinal flora in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011;46:663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cha BK, Jung SM, Choi CH, et al. The effect of a multispecies probiotic mixture on the symptoms and fecal microbiota in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui S, Hu Y. Multistrain probiotic preparation significantly reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5:238–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dapoigny M, Piche T, Ducrotte P, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of LCR35 complete freeze-dried culture in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind study. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:2067–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ducrotté P, Sawant P, Jayanthi V. Clinical trial: Lactobacillus plantarum 299v (DSM 9843) improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:4012–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farup PG, Jacobsen M, Ligaarden SC, et al. Probiotics, symptoms, and gut microbiota: What are the relations? A randomized controlled trial in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:214102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kruis W, Chrubasik S, Boehm S, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial to study therapeutic effects of probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in subgroups of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murakami K, Habukawa C, Nobuta Y, et al. The effect of Lactobacillus brevis KB290 against irritable bowel syndrome: a placebo-controlled double-blind crossover trial. Biopsychosoc Med 2012;6:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Begtrup LM, De Muckadell OBS, Kjeldsen J, et al. Long-term treatment with probiotics in primary care patients with irritable bowel syndrome – a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013;48:1127–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charbonneau D, Gibb RD, Quigley EMM. Fecal excretion of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and changes in fecal microbiota after eight weeks of oral supplementation with encapsulated probiotic. Gut Microbes 2013;4:201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko S-J, Han G, Kim S-K, et al. Effect of Korean herbal medicine combined with a probiotic mixture on diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:824605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberts LM, McCahon D, Holder R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a probiotic “functional food” in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol 2013;13:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbas Z, Yakoob J, Jafri W, et al. Cytokine and clinical response to Saccharomyces boulardii therapy in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jafari E, Vahedi H, Merat S, et al. Therapeutic effects, tolerability and safety of a multi-strain probiotic in Iranian adults with irritable bowel syndrome and bloating. Arch Iran Med 2014;17:466–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Llop E, Suárez C, et al. I.31, a new combination of probiotics, improves irritable bowel syndrome-related quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 2014:8709–8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ludidi S, Jonkers DM, Koning CJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial on the effect of a multispecies probiotic on visceroperception in hypersensitive IBS patients. Neurogastroenterology and Motility 2014;26:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Végh Z, et al. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:16215–16226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rogha M, Esfahani MZ, Zargarzadeh AH. The efficacy of a synbiotic containing Bacillus coagulans in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2014;7:156–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sisson G, Ayis S, Sherwood RA, et al. Randomised clinical trial: a liquid multi-strain probiotic vs. placebo in the irritable bowel syndrome – a 12 week double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stevenson C, Blaauw R, Fredericks E, et al. Randomized clinical trial: effect of Lactobacillus plantarum 299 v on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Nutrition 2014;30:1151–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoon JS, Sohn W, Lee OY, et al. Effect of multispecies probiotics on irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pineton de Chambrun G, Neut C, Chau A, et al. A randomized clinical trial of Saccharomyces cerevisiae versus placebo in the irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong RK, Yang C, Song G-H, et al. Melatonin regulation as a possible mechanism for probiotic (VSL#3) in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized double-blinded placebo study. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoon H, Park YS, Lee DH, et al. Effect of administering a multi-species probiotic mixture on the change in facial microbiota and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2015;57:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lyra A, Hillilä M, Huttunen T, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity improves equally with probiotic and placebo. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:10631–10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spiller R, Pélerin F, Cayzeele Decherf A, et al. Randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856 in irritable bowel syndrome: improvement in abdominal pain and bloating in those with predominant constipation. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2016;4:353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thijssen AY, Clemens CHM, Vankerckhoven V, et al. Efficacy of Lactobacillus casei Shirota for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;28:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]