Abstract

Background:

The treatment efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) for huge single hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has not been fully documented. The aim of this study was to compare TACE and HAIC for patients with solitary nodular HCCs greater than or equal to 10 cm without vascular invasion and metastasis.

Methods:

From July 2015 to June 2020, a total of 147 patients with single nodular HCC greater than or equal to 10 cm without vascular invasion and metastasis receiving TACE (n=77) or HAIC (n=70) were retrospectively enrolled. The tumor response, overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS) were investigated and compared. The treatment outcome of two transarterial interventional therapies was explored.

Results:

The objective response rate and PFS were higher in patients who received HAIC than in those who received TACE (44.3 vs. 10.4% and 8.9 vs. 4.2 months, respectively; P=0.001 and P=0.030), whereas the disease control rate and OS were not significantly different (92.9 vs. 84.4% and 21.3 vs. 26.6 months, respectively; P=0.798 and P=0.749). The decreased levels of alpha‐fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) in patients treated with HAIC were significantly higher than those treated with TACE (P=0.038 and P<0.001). Multivariable analysis showed that the aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index was associated with OS, whereas albumin-bilirubin grade and PIVKA-II were associated with PFS.

Conclusions:

HAIC has better potential than TACE to control local tumors for huge single HCC without vascular invasion and metastasis and thus may be the preferred conversion therapy for these tumors.

Keywords: conversion therapy, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, huge hepatocellular carcinoma, transarterial chemoembolization

Introduction

Highlights

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) has the potential to control local tumors, which is superior to transarterial chemoembolization for huge single hepatocellular carcinoma without vascular invasion and metastasis.

Decreased levels of tumor markers in patients treated with HAIC were significantly higher than in those treated with transarterial chemoembolization.

Patients treated with HAIC have more obvious immune activation reflected by inflammatory response indexes.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer and has high morbidity and a poor prognosis1,2. Tumors with a huge volume are a well-known significant factor that affects patients’ outcomes, which may prevent patients from being able to undergo radical surgical resection or liver transplantation3–6. Transarterial interventional therapy is an effective strategy, such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), that prolongs the survival of HCC patients, especially for patients with large (≥5 cm) or huge (≥10 cm) tumors7–10. Furthermore, interventional therapy can be used as a transitional treatment for patients before conversion liver resection or transplantation, especially for those with inadequate future liver remnant (FLR) or waiting for a donor. With interventional therapy, some patients even achieve a tumor complete response (CR) and experience long-term progression-free survival (PFS)11,12.

TACE is the preferred treatment for intermediate-stage HCC patients13. For some special patients, TACE can also be considered as an alternative treatment option for a single huge HCC, especially in patients in whom resection was not feasible6. Embolization can cause tumor ischemia and inhibit tumor progression with an effectiveness rate of ~50%14,15. However, for the treatment of huge HCC, TACE may be unable to block the blood supply of the entire neoplasm so that the tumor continues to progress in the short term16,17. Hence, more effective therapies are urgently needed to control huge HCCs.

In recent years, HAIC has been proven to be an effective treatment for significantly prolonging the survival of HCC patients8,18. HAIC is satisfactory for patients with larger tumors and advanced HCC patients with vascular invasion7. The treatment principle of HAIC is different from that of TACE9,13. HAIC is performed through indwelling catheters in the main blood vessels supplying the tumor, continuously injecting chemotherapeutic drugs, and extubating the catheters after the drugs are infused7,19. However, few studies have compared HAIC and TACE in treating patients with huge HCC who have potential hepatectomy opportunities. This study aims to retrospectively compare the efficacy of TACE and HAIC in treating HCC patients with tumors greater than or equal to 10 cm and without vascular invasion and metastasis.

Methods

Patients

This study retrospectively included consecutive HCC patients whose first treatment was transarterial interventional therapy in our cancer center from January 2015 to June 2020. A total of 147 patients were eligible for inclusion. The diagnosis of HCC is based on histology or the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines4. The research was retrospectively registered. HAIC began to be put to use for advanced HCC in our institute in 2016. TACE was the standard treatment for unresectable HCC before 2017. Since 2017, HAIC has been almost used for treating unresectable large HCC.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients with histologically or radiologically confirmed HCC; a single tumor with a diameter of greater than or equal to 10 cm; the initial treatment was transarterial interventional therapy; no metastasis or vascular invasion; Child-Pugh grade A/B and performance status less than or equal to 2 before treatment.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: previously or currently suffering from other malignant tumors; previous history of liver resection; vascular invasion or metastasis; Child-Pugh grade C before treatment; and histologically or radiologically confirmed not HCC but other liver malignancies. The criteria are displayed in Figure 1. The retrospective analysis was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our cancer center. This work has been reported in line with the strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery (STROCSS) criteria20 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A868).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarising the patient enrollment process of this study. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

Transarterial interventional therapy procedure

Each patient treated with TACE or HAIC was confirmed by the multidisciplinary tumor team. Patients were treated with transarterial interventional therapy following a standard local protocol described in our previous reports18,19,21. The protocol of TACE was 50 mg of epirubicin, 50 mg of lobaplatin, and lipiodol. The treatment of TACE for the next cycle depends on the tumor response. TACE was performed at no less than 1-month intervals. HAIC was based on the mFOLFOX regimen (leucovorin 400 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, fluorouracil bolus 400 mg/m2 on Day 1, and fluorouracil infusion 2400 mg/m2 for 46 h). HAIC was repeated once every three weeks for up to six cycles. The catheter/microcatheter was placed into the tumor’s main feeding hepatic artery, and the regimen was performed through the hepatic artery. A five French vascular puncture device and a five French catheter were routinely used in HAIC. The microcatheter was not routinely used by all patients. A 2.6 French microcatheter will be used for patients with difficult catheter placement and apparent vascular variation. Repeated catheterization is the most significant difference between HAIC performed by our center and previous studies. Compared with an intra-arterial pump or implanted port catheter system, repetitive digital subtraction angiography and catheterization before each HAIC cycle is more reliable for concentrating the chemotherapy dose in the targeted area and avoiding anticancer drug exposure in other organs. The catheter and microcatheter were removed together when HAIC was completed. Repetitive catheterization was performed in the next HAIC cycle. Any implanted port system was not applied.

Efficacy assessment and follow-up

The first follow-up time of TACE was 4 weeks after treatment, and the first follow-up time of HAIC was 4 weeks after two cycles after treatment. One month after treatment, each patient performed a medical history taking, physical examination, contrast-enhanced computed tomography or/and MRI examination, and laboratory tests. Tumor response was evaluated with the best overall response using the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST)22, which includes CR, partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). The tumor response was recorded as the best response during therapy and was again reassessed at the end of therapy. The primary endpoints in this study were overall survival (OS) and PFS. OS was defined as the date of the initial transarterial interventional therapy to the date of death or loss to follow-up. PFS was calculated from the time of receiving treatment to disease progression or death, whichever came first. The second endpoints in this research were the objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR). ORR was defined as the percentage of patients achieving either CR or PR, which needs to last more than 4 weeks from the initial radiological confirmation. DCR was defined as the ORR plus the percentage of patients with SD. Severity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events (version 4.0).

Statistical analysis

The TACE and HAIC groups were compared using the χ 2-test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test or the independent t-test for continuous data. Variable distributions were described using the mean±standard error (SE) for normally distributed values and the median and range for non-normally distributed values. Survival outcomes, including OS and PFS, were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier curve, and the comparison of survival rates was examined by the log-rank test. Cox regressions were used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI for each variable in the univariate and multivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were undertaken using IBM SPSS (version 26.0, IBM Corporation). A two-tailed P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

A total of 147 HCC patients, including 77 receiving TACE treatment and 70 receiving HAIC treatment, were finally enrolled. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Some patients in this study received targeted therapy or immunotherapy. Patients’ treatment regimens are reflected in Table S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A869).

Table 1.

Comparison of patients’ characteristics between the TACE and HAIC groups.

| Patients’ characteristics | TACE (N=77) | HAIC (N=70) | Total (N=147) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 66/11 | 63/7 | 129/18 | 0.589 |

| Age (years) | 53.5±13.7 | 50.9±10.8 | 52.0±12.4 | 0.193 |

| ECOG PS (0/1–2) | 48/29 | 52/18 | 100/47 | 0.121 |

| etiology (HBV/Nonhepatitis) | 64/13 | 61/9 | 125/22 | 0.651 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 13.1±1.9 | 13.3±3.0 | 12.8±2.5 | 0.56 |

| Tumor gross classification | 0.829 | |||

| Nodular type | 68 | 61 | 129 | |

| Infiltrative type | 9 | 9 | 18 | |

| Child‐Pugh stage (A/B) | 76/1 | 66/4 | 142/5 | 0.308 |

| ALBI grade (1/2-3) | 45/32 | 42/28 | 87/60 | 0.848 |

| CNLC stage | ||||

| I | 77 | 70 | 147 | NA |

| Conversion to surgery | 12 | 24 | 36 | 0.008 |

| Preintervention serum tests | ||||

| ALB (g/l) | 40.5±3.8 | 40.6±4.3 | 40.8±4.0 | 0.796 |

| TBIL (μmol/l) | 15.6±6.2 | 17.9±21.3 | 14.1±15.4 | 0.364 |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 30 947.1±47 653.9 | 25 699.7±44 007.1 | 28 448.4±45 872.4 | 0.490 |

| <400 | 35 | 36 | 71 | |

| ≥400 | 42 | 34 | 76 | |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/ml) | 37 394.1±28 709.7 | 31 548.7±27 717.2 | 34 610.5±28 296.9 | 0.212 |

| ≤40 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| >40 | 75 | 65 | 140 | |

| APRI (>2 vs <=2) | 3/74 | 5/65 | 8/139 | 0.479 |

| NLR (>=5 vs <5) | 13/64 | 10/60 | 23/124 | 0.665 |

| LMR (>=3 vs <3) | 31/46 | 28/42 | 59/88 | 0.974 |

| PLR (>=150 vs <150) | 49/28 | 49/21 | 98/49 | 0.414 |

| SII (>=760 vs <760) | 34/43 | 40/30 | 74/73 | 0.116 |

| SIRI (>=1.26 vs <1.26) | 49/28 | 46/24 | 95/52 | 0.792 |

| PNI (>=45 vs <45) | 59/18 | 50/20 | 109/38 | 0.472 |

| Postintervention serum tests | ||||

| ALB (g/l) | 37.3±4.9 | 38.3±5.3 | 37.8±5.1 | 0.217 |

| TBIL (μmol/l) | 17.5±11.4 | 14.3±12.3 | 16.0±11.9 | 0.102 |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 31 098.3±61 654.0 | 13 910.3±35 371.8 | 22 913.5±51 421.9 | 0.038 |

| <400 | 33 | 47 | ||

| ≥400 | 44 | 23 | ||

| PIVKA-II (mAU/ml) | 28 344.4±30 406.0 | 13 476.3±23 383.0 | 21 264.3±28 198.9 | 0.001 |

| ≤40 | 5 | 10 | ||

| >40 | 72 | 60 | ||

| APRI (>2 vs <=2) | 11/66 | 6/64 | 17/130 | 0.279 |

| NLR (>=5 vs <5) | 25/52 | 14/56 | 39/108 | 0.087 |

| LMR (>=3 vs <3) | 33/44 | 42/28 | 75/72 | 0.038 |

| PLR (>=150 vs <150) | 52/25 | 31/39 | 83/64 | 0.005 |

| SII (>=760 vs <760) | 43/34 | 21/49 | 64/83 | 0.002 |

| SIRI (>=1.26 vs <1.26) | 53/24 | 30/40 | 83/64 | 0.002 |

| PNI (>=45 vs <45) | 38/39 | 42/28 | 80/67 | 0.195 |

AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index; CNLC, The China liver cancer; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; LMR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation; TBIL, total bilirubin.

In the whole cohort, 129 patients (87.8%) were male with a median age of 52. Hepatitis B virus infection was present in 125 patients (85.0%) with Child-Pugh A in 142 (96.6%) and with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) 0 in 100 (70.4%) subjects. Eighty-seven (59.2%) patients were classified as albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade 1, and 60 (40.8%) were classified as grade 2–3. Generally, the two groups’ demographic baseline, tumor characteristics, and liver profiles before treatment were not statistically significant.

The decreased levels of alpha‐fetoprotein (30947.1±47653.9 to 31098.3±61654.0 vs. 25699.7±44007.1 to 13910.3±35371.8, P=0.038) and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) (37394.1±28709.7to 28344.4±30406.0 vs. 31548.7±27717.2 to 13476.3±23383.0, P=0.001) in patients receiving HAIC were significantly higher than those receiving TACE. In addition, the liver fibrosis indices aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index (APRI), prognostic nutritional index (PNI), and several systemic inflammatory markers, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), were analyzed. Patients following HAIC had a higher proportion of high levels of LMR and a lower proportion of low levels of PLR, SII, and SIRI than those following TACE (Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A870). In addition, there are 36 patients finally converting to undergo radical hepatectomy, including 12 cases treated with TACE and 24 cases treated with HAIC, respectively (P=0.008) (Figure S2, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A871).

Tumor response

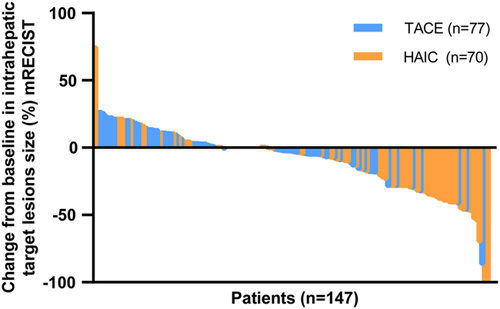

The mRECIST criteria were used to assess the radiological response of HCC receiving transarterial interventional therapy22. The average cycles for TACE and HAIC were 2.2 and 3.4, respectively. The ORR and DCR after treatment were 26.6 and 88.5% in the entire cohort, respectively (including 1.4% CR, 25.2% PR, and 61.9% SD). The HAIC cohort had a higher proportion of CR (2.9 vs. 0%), PR (41.4 vs. 10.4%), and ORR (44.3 vs. 10.4%) than the TACE cohort (P<0.001 and P=0.001). The results are shown in Table 2. The antitumor effect of TACE and HAIC is schematized and displayed as a waterfall plot in Figure 2. In addition, patients who follow HAIC are more likely to have an alpha‐fetoprotein and PIVKA-II response than TACE (P=0.038 and P=0.001, Figure S3, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A872).

Table 2.

Tumour response and survival according to the treatments in the entire population.

| Tumor response (mRECIST) | Whole group (n=147) | TACE group (n=77) | HAIC group (n=70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response (CR) | 2 (1.4%) | 0 | 2 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Partial response (PR) | 37 (25.2%) | 8 (10.4%) | 29 (41.4%) | |

| Stable disease (SD) | 91 (61.9%) | 57 (74.0%) | 34 (48.6%) | |

| Progressive disease (PD) | 17 (11.5%) | 12 (15.6%) | 5 (7.1%) | |

| Objective response rate (CR+PR) | 39 (26.6%) | 8 (10.4%) | 31 (44.3%) | 0.001 |

| Disease control rate (CR+PR+SD) | 130 (88.5%) | 65 (84.4%) | 65 (92.9%) | 0.798 |

| PFS, median (95% CI) | 5.5 (3.737–7.263) | 4.2 (3.066–5.334) | 8.9 (5.257–12.543) | 0.029 |

| OS, median (95% CI) | 24.6 (17.435–31.765) | 26.6 (19.051–34.149) | 21.3 (2.887–39.713) | 0.748 |

CR, complete response; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression‐free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Figure 2.

Tumor response evaluation based on the mRECIST in patients receiving TACE and HAIC. mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Survival and risk factors for recurrence and death

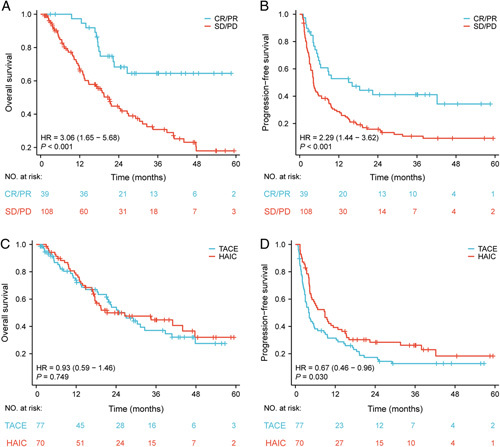

The median OS and PFS of the whole cohort were 24.6 (95% CI: 17.435–31.765) months with 75.7, 51.6, and 40.3% survival and 5.5 (95% CI: 3.737–7.263) months with 35.1, 22.6, and 18.8% survival at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively. A significant increase in OS was observed in patients presenting a tumor response (CR and PR) with a median survival time of more than 40.0 months versus 21.1 months in nonresponders (SD and PD) (95% CI not reached vs. 17.0–25.2, P<0.001). Additionally, higher PFS was discovered in responders (CR and PR) versus nonresponders (SD and PD) (median PFS: 16.1 vs. 4.2 months, 95% CI: 2.514–29.7 vs. 3.577–4.823, P<0.001). The results are displayed in Figure 3A-B.

Figure 3.

Patient survival was shown by the Kaplan–Meier curves. The OS (A) and PFS (B) in patients with tumor response (CR/PR vs SD/PD) according to mRECIST criteria. The OS (C) and PFS (D) in patients treated with HAIC versus TACE. OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

According to the Kaplan–Meier curve, the 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year OS rates were 73.8, 54.0, and 37.1% for the TACE group and 77.6, 49.9, and 44.8% for the HAIC group, respectively. No statistically significant difference in terms of OS was identified between the TACE cohort and the HAIC cohort (median OS: 26.6 months, 95% CI: 19.051–34.149 vs. 21.3 months, 95% CI: 2.887–39.713; P=0.749). The 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year PFS rates of the TACE and HAIC groups were 31.4, 17.3, 12.8% and 39.2, 28.4, 26.2%, respectively. Conversely, the patients who received HAIC with a median survival of 8.9 months (95% CI: 5.257–12.543) had higher PFS than those receiving TACE with a median survival of 4.2 months (95% CI: 3.066–5.334) (P=0.030). Results are shown in Figure 3C-D.

In addition, the multivariable analysis demonstrated that preinterventional APRI was an independent prognostic factor for OS (P<0.001), and ALBI grade and the level of postinterventional PIVKA-II were independent predictive factors for PFS (P=0.049 and P=0.017). The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards regression model shows the association of variables with overall and progression-free survival.

| OS | PFS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | Variables | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| ALBI grade, grade 2–3 vs grade 1 | 2.02 (1.286–3.173) | 0.002 | 1.501 (0.787–2.864) | 0.218 | Treatment, HAIC vs TACE | 0.667 (0.463–0.962) | 0.03 | 0.835 (0.559–1.246) | 0.377 |

| Preinterventional SIRI, >=1.26 vs <1.26 | 1.788 (1.088–2.937) | 0.022 | 1.668 (0.989–2.813) | 0.055 | ALBI grade, grade 2–3 vs grade 1 | 1.827 (1.262–2.645) | 0.001 | 1.527 (1.0–2.332) | 0.049 |

| Preinterventional PNI, >=45 vs <45 | 0.563 (0.348–0.911) | 0.019 | 0.858 (0.454–1.623) | 0.638 | Postinterventional AFP, >=400 vs <400 | 1.665 (1.156–2.398) | 0.006 | 1.185 (0.785–1.79) | 0.419 |

| Preinterventional APRI, >2 vs <=2 | 4.809 (2.035–11.366) | <0.001 | 5.943 (2.373–14.886) | <0.001 | Postinterventional PIVKA-II, >90 vs <=90 | 2.989 (1.698–5.263) | <0.001 | 2.157 (1.146–4.058) | 0.017 |

| Postinterventional NLR, >=5 vs <5 | 2.012 (1.254–3.226) | 0.004 | 1.386 (0.63–3.048) | 0.417 | Postinterventional AST, >40 vs <=40 | 1.871 (1.244–2.815) | 0.003 | 1.233 (0.777–1.955) | 0.374 |

| Postinterventional PLR, >=150 vs <150 | 1.857 (1.158–2.979) | 0.01 | 1.309 (0.697–2.457) | 0.403 | Postinterventional ALB, >=35 vs <35 | 0.596 (0.404–0.879) | 0.009 | 0.944 (0.534–1.671) | 0.844 |

| Postinterventional SII, >=760 vs <760 | 1.613 (1.026–2.536) | 0.038 | 1.051 (0.516–2.142) | 0.89 | Postinterventional TBIL, >20.5 vs <=20.5 | 2.25 (1.462–3.461) | <0.001 | 1.585 (0.915–2.745) | 0.1 |

| Postinterventional PNI, >=45 vs <45 | 0.398 (0.252–0.630) | <0.001 | 0.653 (0.335–1.275) | 0.212 | Postinterventional PT, >13.5 vs <=13.5 | 2.427 (1.37–4.297) | 0.002 | 1.303 (0.691–2.456) | 0.413 |

| Postinterventional APRI, >2 vs <=2 | 2.638 (1.472–4.729) | 0.001 | 1.353 (0.674–2.716) | 0.395 | Postinterventional ALBI grade, grade 2–3 vs grade 1 | 1.77 (1.217–2.574) | 0.003 | 0.892 (0.52–1.529) | 0.677 |

| Postinterventional PLR, >=150 vs <150 | 1.478 (1.019–2.143) | 0.04 | 0.993 (0.63–1.563) | 0.974 | |||||

| Postinterventional PNI, >=45 vs <45 | 0.505 (0.35–0.729) | <0.001 | 0.674 (0.382–1.191) | 0.174 |

AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index; AST, aspartate-aminotransferase; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; PT, prothrombin time; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation; TBIL, total bilirubin.

TACE-related and HAIC-related adverse events (AEs)

TACE-related and HAIC-related AEs are listed in Supplementary Table S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 6, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A873). Mild to moderate AEs (grades 1 or 2) accounted for most of the reports. None of the patients in these two cohorts developed treatment-related death after the initial TACE or HAIC.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we aimed to explore the efficacy of transarterial interventional therapy, including TACE and HAIC, in patients with huge single HCC without vascular invasion and metastasis. We found that HAIC has better PFS than TACE in treating huge HCC. Moreover, the ORR of patients receiving HAIC was significantly higher than that of patients receiving TACE. In addition, both TACE and HAIC have relatively good safety. The AEs did not differ significantly between the two groups. Our study also found that patients treated with HAIC had a higher proportion of high-level LMR and low-level PLR, SII, and SIRI. These results suggest that patients treated with HAIC have more obvious immune activation, and HCC patients receiving HAIC combined with immunotherapy may achieve better efficacy, which is consistent with the previous report by Mei et al.23. The above findings indicate that HAIC has potential advantages over TACE in treating huge HCC.

Patients with large HCC volumes are often candidates for surgical resection in the absence of metastasis and tumor vascular invasion24. Unfortunately, due to the large tumor size in many patients, the residual liver volume after hepatectomy is insufficient to allow one-stage surgical resection25. For solitary HCC with adequate remnant liver volume, liver resection is recommended as the primary therapeutic approach by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging and treatment strategy3. However, transarterial therapy may be an alternative therapeutic option when resection is not feasible. Moreover, according to the China Liver Cancer staging system, when surgical resection is not feasible, TACE, ablation, or in combination with TACE may be recommended as alternative treatment options6. The vast majority of patients in this study were evaluated as having inadequate FLR. A small number of patients chose TACE or HAIC based on their own wishes and refused surgery at first visit. Primary factors which preclude patients from accepting surgery include perioperative complications, advanced age, hospital costs, length of stay, religious beliefs, and cultural background. Some patients in this study received TACE or HAIC due to insufficient FLR at first visit. During the treatment period, the tumor was controlled, and FLR increased. Although some patients were assessed as SD, and FLR was sufficient, they desired to undergo surgery. Therefore, not all patients with CR/PR underwent surgical resection, and some patients who underwent surgery had a tumor response of SD. In addition to being widely recommended in treating advanced HCC, transarterial interventional therapy is also commonly used in patients awaiting liver transplantation and with large liver malignancies26,27. Transarterial interventional therapy has been reported to control tumor progression while augmenting FLR. Single huge HCC patients treated with transarterial interventional treatment may have the opportunity to receive future radical surgery28. In this study, the analysis of potentially resectable patients with large HCCs receiving transarterial interventional therapy indicates that HAIC may have a better tumor response and longer PFS than TACE, which provides a specific basis for the therapy choice of patients waiting for liver transplantation and patients undergoing conversion hepatectomy.

HAIC has satisfactory curative efficacy in treating various stages of HCC7,8,29. For resectable HCC beyond the Milan criteria, HAIC can significantly reduce the risk of postoperative recurrence29. For intermediate and advanced HCC, HAIC monotherapy or combined medication therapy has a survival advantage over the targeted drug sorafenib18. HCC is one of the most common malignant tumors. Liver resection is considered an essential treatment that can provide patients with long-term survival opportunities2. However, ~80% of HCC patients in China cannot undergo radical surgery due to tumor burden, advanced tumor stage, or limited hepatic functional reserves when they are first diagnosed30. Given the above situations that may preclude patients from taking surgery, studies have been carried out to explore how to downstage the tumor stage to enable patients to obtain surgery opportunities31–33. Systemic therapies, such as targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors, are not recommended for inoperable patients due to the tumor size3,6. Portal vein embolization and associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy have the potential for faster FLR augmentation. However, there is also a risk of accelerating tumor progression due to changes in intrahepatic blood flow34–36. As major means of transarterial interventional therapy, HAIC and TACE can potentially increase the residual liver volume while shrinking the tumor size by different antitumor treatment37,38. TACE achieves an antitumor effect by blocking tumor-feeding vessels and injecting chemotherapeutic agents39. Studies have revealed that although TACE blocks the artery, the tumor still attempts to generate new blood vessels through angiogenesis to receive a blood supply from the portal vein16,17. In contrast, catheterization placed into the tumor’s main feeding hepatic artery was routinely performed for HAIC.

Actually, HAIC appeared in the 1980s, but its use has been limited due to insufficient efficacy. Encouragingly, HAIC for HCC patients has progressed in our cancer center recently. Anatomically, unlike intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal liver metastases, HCCs derive nearly all of their blood supply from the hepatic artery. We observed that as the tumor size reduction, the primary tumor-feeding arteries change. One recent study suggests that the arterial infusion technique used in our study appears to capture the survival benefits of additional HAIC7. It is necessary to adjust the microcatheter tip position in the subsequent cycle of HAIC and remobilize the newly developed hepatic-gastroduodenal collateral artery. Noticeably, another study revealed that repetitive catheterization for HAIC yielded a better result than an implanted port catheter system40. Consequently, HAIC provides better local control than TACE for huge tumors. Li et al.8 reported that HCC patients treated with FOLFOX-HAIC showed a higher response rate than the TACE group and a longer median PFS. Similarly, in the present study, the HAIC cohort showed a longer PFS and better ORR rates than the TACE cohort. However, there was no significant difference in OS between the two cohorts. Generally, a large tumor volume indicates a high tumor burden. Patients received a single TACE or single HAIC as multiple treatments may experience more adverse effects. HAIC generally has more treatment cycles than TACE. Therefore, combination therapy is a key strategy to improve efficacy and long-term survival for these patients. Our study reveals that transarterial interventional therapy can provide adequate therapeutic efficacy for HCC patients with single huge tumors, especially HAIC, which can achieve a longer PFS than TACE. Moreover, previous studies by our team have confirmed that compared with TACE, HAIC can bring a significant survival advantage to patients with advanced HCC21. Consequently, HAIC has promising assistance when patients wait for liver transplantation or as an upfront approach to conversion surgery.

There are several limitations to our research that should be mentioned. This study was a retrospective analysis based on a single institute. We acknowledged that there are some shortcomings in the retrospective design. Therefore, selection bias may exist within the treatment allocation (HAIC or TACE), even though the general characteristics (e.g. age, ECOG, Child-Pugh stage) of the two treatment groups were not significantly different. This retrospective data cannot yet be used to make decisions on patients with huge HCCs treated with TACE or HAIC to achieve long-term survival. Nonetheless, our study provides useful baseline data for assessing single huge HCCs without vascular invasion and metastasis. Hence, the results of our research needed to be validated by multicenter, prospective randomized studies. In addition, our results may not be generalizable to all HCC patients because almost all participants in this study had HBV backgrounds. Nevertheless, the predominant etiology of HCC patients in Western countries and Japan is associated with HCV or alcoholic liver disease.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed that HAIC exhibited superior PFS and ORR than TACE for HCC patients with a single, huge tumor (≥10 cm). HAIC may be the preferred therapy for these patients.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of SYSUCC (No. B202031801).

Sources of funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172579, No. 81871985); Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2018A0303130098 and No. 2017A030310203); Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2017A020215112); Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. A2017477); Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No. 201903010017 and No. 201904010479); Clinical Trials Project (5010 Project) of Sun Yat-sen University (No. 5010-2017009); and Clinical Trials Project (308 Project) of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (No. 308-2015-014).

Author contribution

M.D.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software and visualization, writing – original draft; H.C.: data curation, methodology, writing – original draft; B.H.: data curation, methodology, writing – original draft; C.L.: methodology, software and visualization; R.G.: formal analysis, software and visualization; R.G.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: Research Registry; Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus transarterial chemoembolization, potential conversion therapies for single huge hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective comparison study.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry9133.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-theregistry#home/registrationdetails/64842b1b3e704f00295b8eca/.

Guarantor

Rongping Guo.

Data availability statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and express their deepest gratitude to the participants of this research.

Footnotes

M.D., H.C., and B.H. contributed equally to this work.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 11 August 2023

Contributor Information

Min Deng, Email: 103561732@qq.com.

Hao Cai, Email: 263385180@qq.com.

Benyi He, Email: 47723543@qq.com.

Renguo Guan, Email: dengmin0207@126.com.

Carol Lee, Email: dengminmei@sina.com.

Rongping Guo, Email: guorongpingsysucc@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma, eng. New Eng J Med 2019;380:1450–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma, eng. Lancet (London, England) 2018;391:1301–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol 2022;76:681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yau T, Tang VY, Yao TJ, et al. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1691–700 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2019 Edition). Liver Cancer 2020;9:682–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He M, Li Q, Zou R, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin vs sorafenib alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li QJ, He MK, Chen HW, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus transarterial chemoembolization for large hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raoul JL, Forner A, Bolondi L, et al. Updated use of TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: How and when to use it based on clinical evidence. Cancer Treat Rev 2019;72:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng M, Lei Q, Wang J, et al. Nomograms for predicting the recurrence probability and recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after conversion hepatectomy based on hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy: a multicenter, retrospective study. Int J Surg 2023;109:1299–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lencioni R. Loco-regional treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010;52:762–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin S, Hoffmann K, Schemmer P. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Liver Cancer 2012;1:144–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sieghart W, Hucke F, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Transarterial chemoembolization: modalities, indication, and patient selection. J Hepatol 2015;62:1187–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burrel M, Reig M, Forner A, et al. Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) using Drug Eluting Beads. Implications for clinical practice and trial design. J Hepatol 2012;56:1330–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lencioni R, de Baere T, Soulen MC, et al. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Hepatology 2016;64:106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung TT, Poon RT, Jenkins CR, et al. Survival analysis of high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy vs. transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinomas. Liver Int 2014;34:e136–e143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyayama S, Matsui O, Zen Y, et al. Portal blood supply to locally progressed hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: observation on CT during arterial portography. Hepatol Res 2011;41:853–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S, Mei J, Wang Q, et al. Transarterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-center propensity score matched analysis of real-world practice. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2021;10:631–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S, Deng M, Wang Q, et al. Transarterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX could be an effective and safe treatment for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Oncol 2022;2022:2724476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agha R, Abdall-Razak A, Crossley E, et al. STROCSS 2019 guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2019;72:156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He MK, Le Y, Li QJ, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy using mFOLFOX versus transarterial chemoembolization for massive unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective non-randomized study. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mei J, Li SH, Li QJ, et al. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy improves the efficacy of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021;8:167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaydfudim VM, Vachharajani N, Klintmalm GB, et al. Liver resection and transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond milan criteria. Ann Surg 2016;264:650–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Mierlo KM, Schaap FG, Dejong CH, et al. Liver resection for cancer: New developments in prediction, prevention and management of postresectional liver failure. J Hepatol 2016;65:1217–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belghiti J, Carr BI, Greig PD, et al. Treatment before liver transplantation for HCC. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Y, Jeong SW, Young Jang J, et al. Recent updates of transarterial chemoembolilzation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glantzounis GK, Tokidis E, Basourakos SP, et al. The role of portal vein embolization in the surgical management of primary hepatobiliary cancers: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017;43:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Zhong C, Li Q, et al. Neoadjuvant transarterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX could improve outcomes of resectable BCLC stage A/B hepatocellular carcinoma patients beyond Milan criteria: An interim analysis of a multi-center, phase 3, randomized, controlled clinical trial[J]. J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39(suppl 15): abstr 4008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu D, Song T. Changes in and challenges regarding the surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in China. Biosci Trends 2021;15:142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzaferro V, Citterio D, Bhoori S, et al. Liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): a randomised, controlled, phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L, Chen L, Zhang W. Neoadjuvant treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021;13:1550–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang X, Xu H, Zuo B, et al. Downstaging and resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with extrahepatic metastases after stereotactic therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2021;10:434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, Peng Y, Hu J, et al. Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy for unresectable hepatitis B Virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center study of 45 patients. Ann Surg 2020;271:534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke L, Shen R, Fan W, et al. The role of associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy in unresectable hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo DD, Lee HC, Jang MK, et al. Preoperative portal vein embolization and surgical resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and small future liver remnant volume: comparison with transarterial chemoembolization. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:3501–3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee HS, Choi GH, Choi JS, et al. Surgical resection after down-staging of locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by localized concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3646–3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang CW, Dou CW, Zhang XL, et al. Simultaneous transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and portal vein embolization for patients with large hepatocellular carcinoma before major hepatectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2020;26:4489–4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyayama S, Mitsui T, Zen Y, et al. Histopathological findings after ultraselective transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2009;39:374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda M, Shimizu S, Sato T, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with cisplatin versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: randomized phase II trial. Ann Oncol 2016;27:2090–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.